Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 333

July 26, 2015

Meditation on Sandra Bland’s self-possession, The Beatles and neo-Black codes of conduct

The image of Sandra Bland I cannot get out of my head is her selfie wearing a blue Beatles t-shirt.

Besides being professional black women with spirited senses of self, I am eons older, we seem to have loving the Beatles in common.

As her story was developing across the pond, I was in Liverpool reuniting with graduate school sistahgirls who were also there to present work at conferences that focused on “TransAtlantic Dialogues on Cultural Heritage,” while I just finished performing in one on “After the Revolution: Visions and Revisions of Haiti.” We did a Beatles taxi tour during which, we ran through lyrics of most of the major hits by the fab four with a guide who took pictures of our spirited emotional responses at every major site from Ringo and John’s childhood homes to, finally the orphanage, Strawberry Fields.

The Beatles were a much needed respite after a collective experience of days filled with intellectual engagement in environments with a paucity of black presence, meals at amazing eateries in streets with architecture and museums that were overwhelming reminders of Liverpool’s role as a major port in the slave trade. I had no idea that Penny Lane, the street, which John and Paul wrote about, was named after James Penny, a most successful slave trader.

It took me days to bring myself to watch any of the SandySpeaks videos. It wasn’t the jet-lag. I simply could not get beyond pictures of her so full of life knowing her life had ended. I could not bring myself to watch them because for many of us, we see Sandra in ourselves. She could have very well been me. She could have been my sister, cousin or friend. I could not bring myself to watch because she smiled a lot. She glowed. There is a radiance that emanated from her, which came from a fierce black woman on a quest of self-discovery with all of its ups and downs, a black woman determined to be of significance in this unjust world, a black woman who, as her mother described was “an activist, sassy, smart, and she knew her rights.” She was using her knowledge and skills to creatively create her life. Sandra Bland was not uppity. That may have been a perception of her by a white officer of the law clearly insecure in his position of authority who had no idea who he is when faced with someone like her.

Sandra Bland embodied a rare charismatic self-possession that disrupts social orders. It is one that black women like filmmaker Ava DuVernay who don’t ask for permission to be who they are and do as they do, reside. Feminist Wire co-founder, Tamura Lomax wrote that . Black women freedom fighters who believed in their causes. They talked the talk and walked the walk to use an old cliche. This way of being in the world is one for which black women who do not submit continually pay a very high price. Within the social limits of white imagination, complexity is never ours, black women like Sandra Bland, black women like us, are be reducible to four, maybe five, stereotypes at the most.

We all have our share of DWB stories. This pursuit to extinguish and contain our blackness is not just with law enforcement, but in everyday “civil” interactions. Indeed, if I had a dime for every time I was told to keep my mouth shut, stay in my place, not question my seniors, or watch my comportment too often by white men and women in power… well that is another story. Fact is, I grew up under a dictatorship in Haiti, I have always had a very complicated relationship with silence. Every time I consider Sandra’s reaction, I identify with it. Her response whatever else you may think of it, was an act of self-possession. Her constitutional rights were being violated and she simply would not stand for it.

As black people, we live with the continuities of slavery and the Jim-Crow era when state sanctioned slave codes determined how we expressed fundamental parts of our “partial” personhood. We are being ruled by neo black codes of conduct enforced by social and legal machinery that demand we submit in the presence of white power or else become part of a landfill of hashtags. Sandra Bland refused because she knew her rights.

Respect! Rest in Power.

July 24, 2015

What is “Champeta Urbana”? An Interview with Kevin Flórez

Kevin Flórez is one of the main stars of an up-and-coming Colombian genre dubbed as “champeta urbana.” Champeta, without the “urbana,” is on of the most traditional rhythm of his native Cartagena. And it was also there were he added the last name to this new genre.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s boats coming from West Africa would dock in Cartagena, or in Puerto Colombia, the port of nearby but much larger Barranquilla, and would bring with them LPs of rhythms such as South African mbaqanga, Congolese soukous and Nigerian highlife.

In almost every working-class neighborhood of Cartagena, people would design colorful sound systems, known as “picós” for the local pronunciation of “pickups,” and would play these albums, which eventually led to a truly local industry of city’s musicians playing and recording songs influenced by these genres.

Flórez grew up in one of these neighborhoods, but, he says, his life was somewhere else: it was in hip-hop. After trying that career path during his teenage years, he grew closer to champeta and helped create a mixture of those two genres, which he called “champeta urbana.” Now, after working in this new genre for about four years, his music has become a staple of Colombian parties far and wide, and it has given Flórez national acclaim and international recognition.

But as his music becomes more international and moves him closer to other countries and other genres (such as Puerto Rican reguetón, or Dominican bachata) many hard-line champeteros still seem reluctant to accept him and others playing similar music as part of their tradition.

Charles King, author of the popular champeta song “El chocho bacano”, for example, says that “people doing ‘champeta urbana’ are not true champetúos. They tried doing reguetón and dancehall, and it didn’t work out, so they invented this.”

I met with Flórez outside of a barber shop in Jamaica, Queens, to talk about all of this and to discuss his debut in New York City, which will happen this Saturday, July 24th, in Astoria.

Is it the first time you come here? What does it mean to you?

Yes, it’s the first time. For me, this first time is like a dream. I feel like I’m still living a dream. When I was very young, I wanted to know the United States, because of many musicians I liked, such as Snoop Dogg. It was a musical environment where we listened to a lot of hip-hop and its setting was New York, or Los Angeles. It was a different world, the United States. So being here, it feels like coming through the big door, because we didn’t just come to do some promotions, there are already a lot of people who know us, especially in the Latino world. There is still a long way to go, but I think this is a first step: to knock on the door of La Unai. So I’m very happy, I still can’t believe it!

What are you expecting from your concerts here?

We already played in Miami and there was a good crowd—a full house, thankfully. In New York we’ve only done a one-week expectation campaign. We couldn’t promote it for two months, or one month, but rather just for one week. And if we can fill the place with only this, it means that there is a good vibe, and that the audience really likes me.

How did you get into hip-hop in Cartagena, a city mad for champeta?

My parents were break dancers. Before I was born, they were breaking. You know the influence of hip-hop in the ’80s was great on many artists like Michael Jackson and other big celebrities. They in turn had an impact on my aunts and uncles, who started breaking. So when I was born, what I listened to was a lot of hip-hop, Afrika Bambaataa, Tupac, Notorious B.I.G., Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre. Also hip-hop from Puerto Rico, the Mexican rapper Mexicano, who just passed away this week. Daddy Yankee has been an influence, too. So, growing up, I was called “El niño del rap” and I made hip-hop. I was invited to many hip-hop festivals in Bogotá, I even recorded a few hip-hop songs when I was 15.

Of course, the champeta I am making right now has a big influence from hip-hop. I combined champeta with the format of hip-hop, with hip-hop’s bass drums. It is a champeta sound, but including very urban sounds, such as reggae, dancehall, and hip-hop. But in the neighborhood where I grew up, hip-hop and champeta were two extremes, and putting them together felt odd at first. But I think there was a magic touch somewhere between both genres and now we have champeta urbana.

How did that combination came to be?

Well, I created it in a working-class neighborhood, listening to champeta. It was La Campiña, a poor neighborhood of Cartagena, where I was raised listening to champeta. But what I liked was hip-hop. But I thought “my thing is not the United States, I can’t make hip-hop.” Also, hip-hop is not well supported in La Costa [the Colombian Caribbean], the listeners of the genre there are few.

So I said I would take this flavor and combine it with champeta, to see what happened. I started trying to measure the balance. Then the new wave of champeta happened. It had a renewed air which helped it grow, in part thanks to me—I won the first Congo de Oro and the first Luna Award for champeta, and also a few Premios Shock, and Premios Nuestra Tierra.

Then [American reguetonero] Nicky Jam decided to do a song with me. We did it and people really liked it. And there are a lot of artists who have really liked my style, such as [Puerto Rican reguetón duo] Jowell y Randy, who say that champeta reminds them of the beginnings of reguetón.

I started this in 2011, but champeta is much older, it comes from the time of El Sayayín, but now there is a new style, a new era of champeta. And, thankfully, it has brought us to Europe, Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Chile and other Latin American countries, where champeta is being supported.

How did the old-school champetúos receive your music?

At the beginning it was very hard. They didn’t agree with this. Even today there are plenty who won’t accept it. I feel we are still in an evolutionary phase, a process of introducing this genre to other countries, and adapting it for other audiences. But old-school champetúos didn’t like this. They think that what I do is not champeta. But I think that this will be good for them as well, because people are talking about champeta. Some have considered this evolution as something bad for them. But if you look at hip-hop, you realize that the current genre is not like the hip-hop from a few years ago. It is not as underground, the world of hip-hop has changed, and that is just a result of evolution. If you stay monotonous, nothing will happen with you, your market will stay at a standstill.

Why “champeta urbana”?

“Champeta urbana para el mundo!”, that is my slogan. But the genre is “champeta urbana.” Champeta urbana is different from champeta because, well, let me tell you the story:

In the ‘80s, ships and people going to Africa brought back African music, and in the Colombian Caribbean they called that music “champeta africana.” Why champeta? Because at that time, when people went to the picós—the kind of parties which were also called “casetas”—people from the south of the city didn’t feel comfortable going to a club with people from the elite-class of the city. So the people from the south made their own parties, and they played that African music there.

People who went to a caseta to dance, usually had a machete with them, and when a fight broke out, machetes would be drawn. But the knives were too big and many started making them shorter, into a blade known as a “champeta.” People then would ask each other “are you going to that champetúos party?”. And that’s how the term “champeta” came to be. It’s kinda like the name “rock and roll,” just a stone being thrown. It’s a jocular name given to this rhythm.

That first style of champeta is called “champeta africana,” then it came the time of “champeta criolla,” made by local musicians like El Sayayín, or El Afinaíto [Flórez sings part of “Busco alguien que me quiera”]. And now we are in the third wave, which is “champeta urbana,” as I have baptized it. And it’s growing, we’re seeing many new artists in this genre.

Do you think there is an established industry for the genre? Who else do you consider part of champeta urbana?

It’s being built. I feel each of us is working on our own thing, but also that we are together in this, working to grow the genre. There are plenty of other people working on this. There is Mr. Black who is, so to speak, a legend of this rhythm. But there are many others, such as Young F, who is following the steps of the new wave of champeta. But there are many who are there, not just me.

What do you think is the state of champeta outside of Colombia?

I think people see it as a new genre, just like many of us saw bachata not long ago. We heard this rhythm and thought “what is this? Oh, bachata?”. But [famous Dominican merenguero] Juan Luis Guerra had been doing it for long. He had to explain to the world what was bachata and how to dance it.

That is what we’re doing with our champeta, just showing it to people, showing them how it’s danced and telling them its story, so people can be familiar with the genre. So I think that, from outside, it’s seen as a new genre that is only beginning. Well, at least in Puerto Rico it is a genre that is entering hard. We have fans in Peru who listen to champeta. In the U.S., many Latinos are listening to our music thanks to the support of Nicky Jam, who is an artist with a longer career, and thanks to the support of De La Ghetto, who is someone very well respected in the world of reguetón.

…

Check out Flórez’s hit “La invité a bailar” below:

Does Israel “Blackwash” to deflect international scrutiny?

It would be an understatement to say that Israel’s international standing is not so spectacular at the moment. Between the continued occupation of Palestine, last year’s war in Gaza, and a belligerent government, there is little doubt that fewer and fewer of the world’s citizens hold a positive view of the country. The Israeli government, determined to fix what it considers an image problem rather than its underlying causes, has embarked on a mission of hasbara: to “explain” Israel’s policy positions to the international community, and engender sympathy for Israel.

One axis of this response – colossally ineffective as it is – concentrates on Israel’s role in development and aid projects across Sub-Saharan Africa. The press promotes Israeli medical efforts in the “Ebola zone” in West Africa. They celebrate the supposedly vital role of Israeli firms in irrigation projects in Malawi. Informational media is replete with stories like Israel’s “heroic” rescuers in Madagascar. All this despite the fact that Israel gives a lesser proportion of its national income to aid than similarly wealthy countries – even less than debt-laden Greece.

Is this “blackwashing?” i.e, using black bodies to justify Israel’s military aggressions and human rights violations.

We are now familiar with “pinkwashing” – efforts by states to distract attention from human rights abuses by concentrating on a supposedly-progressive LGBT rights record. Though most known in the case of Israel, whose record of using gay rights to justify or distract from the Occupation is well established, it has also been well-noted in the Netherlands, Britain, and Scandinavia. Yet blackwashing is a term that has also surfaced. In the Israeli context, it describes state efforts to market a country known to have forcefully given birth control to its citizens of Ethiopian descent as friendly to blacks. Here, however, I think there is another angle of blackwashing: Israel vis-à-vis African countries.

Israel blackwashes by marketing itself as a development savior to African countries. It seeks to portray itself as a “good country” through the tired trope of “helping Africa.” This is a contentious if not specious depiction of Israel’s relations with African countries. Let us leave aside Israel’s horrific domestic racism; blackwashing is aimed at a foreign audience – not least, a young Jewish American public, increasingly skeptical of Israel’s actions.

What does “blackwashing” entail? The discourse pivots on two figures: technology donation and the white savior.

Firstly, blackwashing is closely tied to Israel’s marketing as a “start-up nation.” The work of technology firms such as Netafim in providing irrigation drips to countries like Senegal is frequently celebrated in Israeli media. Israel advocacy groups produce clickbait-laden paeans to technological aid with titles like “The Top 12 Ways Israel Feeds The World” or detailing how Israel “restored carp to Lake Victoria.” In short, Israel is portrayed as the “big tech brother” helping Africans have a normal life. I imagine many of the writers of this article think, “in this framework, how could Israel be colonial?” (Little do they know…)

Israel’s defenders also deploy the figure of the “white savior.” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs details how Israeli assistance was apparently more than that of other Western states, and emphasizes a narrative of continued assistance from Israel to newly independent African states. They are silent on Israel’s continued financial, military, and political support for South Africa’s apartheid regime, or that African governments balked at Israel’s policies after the Yom Kippur War. Rather, the focus is on Israel as the helper, the essential assister, and the carrier of the new white man’s burden of “assistance” and “investment.” This robs agency from the Africans who have by and large managed these projects. In addition, the Israelis profiled in this effort are overwhelmingly Ashkenazi and white –the work of Ethiopian Israelis is well…whitewashed.

I do not want to dismiss the potential positive benefits of these projects – although, as amply noted on these pages, such initiatives often hurt more than help. Rather, I want to return to a central point: that the Israeli state is using these projects to raise its international profile and image. Yet a central truth remains: no number of aid initiatives or stylish projects can undo the scar of the Occupation. To use the tired trope of the technologically-advanced white savior on a civilizing or aid mission to the poor black body as a marketing ploy appropriates African experiences to serve a colonial project. Call it blackwashing, call it inappropriate, but this emphasis in Israel’s rhetoric on “the aid-giver” distracts from the wider implication of this state’s policy.

Mandela Day: Where is our imagination?

We’ve just passed that time of year when the Charitable Industrial Complex puts on its Sunday best for Mandela Day. This is the time every year when well-meaning South Africans clad in carefully chosen ripped jeans paint murals while wearing crisp protective clothing (in case they actually have to touch the disenfranchised). No rest for those thumbs as hashtags of #charity #67minutes #doinggood and #selfie flood social media networks.

Mandela Day has been derided as a disingenuous spectacle at best or, at worst, a dangerous ploy to distract us from the inequalities which create the necessity for such lopsided charity in the first place. Who has the privilege to give, to decide who receives, and how much? There are few who dare think beyond seeing Mandela Day as a once-off spree of guilt purging. Few who venture beyond the typical displays of charitable good-will we often see enacted by celebrities and businesses on Mandela Day.

Very few care to use this opportunity to channel the overwhelming sentiments of goodwill into a project that might be different. Where is our imagination? Our creativity? Our connectivity?

It is not only the stereotypical “white saviour” who enacts the usual scripts of downward benevolence during Mandela Day. Anyone who consumes mainstream media is well versed in the appropriate responses to the seemingly overwhelming crises of inequality: smile, serve soup at an NGO, and walk away. The charitable industrial complex asks nothing more than that, so much so, that we are often told that “any little thing will do”. It is upsetting that it is often sanitised and deliberately depoliticised versions of collective action which are recognised as positive contributions to remaking and reshaping South Africa, but being sincerely upset by this situation doesn’t mean we are changing anything.

If the end goal we seek is social justice, equality, and a greater sense of shared responsibility, our means of getting there needs to be a bit more serious. No-one is asking you to give up your day job, but that doesn’t mean settling for being a tourist in “making a difference”. Thousands of South Africans, across the “colour”, economic and gender spectrums are willing to do something, and evidently anything, to feel like we are part of a positive movement for change, yet we seem to fail dismally each year. Maybe it’s being too committed to Mandela the icon, maybe it’s our fixation with just doing “our bit” for 67minutes, but it doesn’t have to be our defining destiny.

The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory has called for us to “Make Everyday a Mandela Day” in an attempt to shift the perception of Mandela Day as a yearly once-off. But it is proving far harder to shift the firmly fixed idea that we can change society by doing “service at” someone instead of actively “working with” those we regard as distant others to formulate new terms of engagement.

Mandela Day has largely been reduced to being “nice” and it seems that as South Africans, we have given up our collective imaginations to corporatised branding of “Ubuntu,” blindly following neatly packaged scripts, where some are cast as givers and others as receivers, lest we really get into the messy business of living in a shared community. And it is messy. There is an underlying assumption that the communities who are often touted as beneficiaries of charity are unaware of the various ways in which top-down charity works. Yet, community organisations and student volunteers who work in community development are not ignorant of the sporadic good will that comes during Mandela Day. Rather than bemoaning those who take 67minutes once a year to engage in community development, some organisations find strategic ways of using this day to get much needed attention or help for the work they do.

Whether it’s getting individuals to help fix a school’s jungle gym, scoring a fieldtrip to a prohibitively expensive learning site, or getting someone to help with website maintenance, community based organisations often find ways to maximise on the good will shown during Mandela Day. The ethical complexities of economically and socially stratified groups working together to change the conditions which create these roles in the first place, however, are really tough, and often we fail because of reifying poverty or being unwilling to divest ourselves from privilege.

Many Mandela Day participants are often shocked about how little they know about neighbourhoods which are a mere stone’s throw away from them, how complicated the act of building or painting can be, and some participants are surprised by the amount they unexpectedly learn from those who they have been taught to pity or envy.

Twenty years of democracy is a good point for us to really reflect on each of our roles in creating this country. Transformation is not just for the well meaning old white men who call me “girlie,” or for those who struggle to make ends meet, it’s for all of us. Recognising this in earnest means we all have a great deal of personal and collective work to do. We can’t transform by ourselves while remaining in our comfort zones, nor can we force others to teach us humanity. In real life, negotiating meaningful relationships is not a magic pill, it has its ups and downs, but we pursue social change not because we are being nice, but because it’s our only hope.

For me the overwhelming excitement about Mandela Day is an indication that South Africans don’t need a special invitation to peel away the blinkers, we just need to have the sincerity to open ourselves up to learning to do things in a different way. There are over 300 days to co-create a new vision of Mandela Day, don’t we owe it to ourselves to swim against the currents and co-create a new blue-print?

July 23, 2015

At the crossroads of BET, Afrobeats, and #BlackLivesMatter

If you have been closely following developments in the Afropop music industry recently, you may have noticed an interesting twist to the saga of BET’s award for Best International Act: Africa. In the wake of the latest BET awards show, several African artists have accused the network of treating them as second class citizens, and have demanded more respect from the show’s coordinators. Well the creator of the award, BET’s Lilian N. Blankson, has responded with an interesting series of tweets, a statement that seems to be telling the artists that they just need to accept the award, and be grateful for what they have. Statements such as:

BET will always signify Black Star Power… Africa, if we want to be featured prominently, we need to know the facts and be very practical.

BET domestic does not and has never aired African music so to have a category is a major deal. Let’s prove and show them our worth not anger.

Finally, let’s be a little humble. No one owes us anything. Like everything else, we have to work our way to the top so we can stay there.

Without weighing in on the specifics of the award (for that revisit my post article on the award), I would like to share a few observations about what the implications are of this latest episode, in an ongoing saga of Black identity politics.

First of all, it’s interesting that African artists now feel powerful and influential enough to challenge American cultural hegemony publicly. I chalk this up to a general international success African pop artists have enjoyed on the continent and in Europe in recent years. Nigerian artists can sell out stadiums across the continent, reaching into monied international hubs with diaspora populations like Dubai and London. In the UK Afrobeats artists fill the O2 Arena, and have a dedicated radio show on BBC1xtra. In Caribbean communities, West African pop songs dominate the road at Carnival celebrations from Trinidad to Toronto. For artists who are the top stars in their home markets, and increasingly taking a central role in global ones, it would make sense that they would expect at least comparable respect they receive in London, Lagos, Port of Spain, and Johannesburg from the BET awards in Los Angeles.

I applaud the African artists for standing up to a continued marginalization of Africanness from international dialogues around Blackness – especially in global pop culture, a realm where a Black Americanness in service of corporate U.S. interests is employed worldwide. Fuse ODG, one of the artists who led initial calls for a boycott, himself is a sort of cultural activist out of London. He has experience working in marginalized communities in the UK, so it makes sense that his artistic work would reflect that personal history.

Yet, African artists must not forget that the Blackness employed by “Black Entertainment Television” is an American identity-based phenomenon. Complaining about second rate treatment is not really knowing the rules of the game on a foreign (and globally dominant) playing field. And the truth is, although there have been several high profile artist collaborations – Fuse ODG with Wyclef, Ice Prince with French Montana, Davido with Meek Mill, Sarkodie with Ace Hood, P Square with Rick Ross – these often end up looking like superficial attempts to hang with the cool kids, especially since many of these are collaborations are paid business encounters. If anything they reinforce American hegemony, not question it (Wale’s seemingly sincere flirtations with his Nigerian identity are a welcome reprieve from all this, but he’s already made it in America — also, I would be remiss to not mention Skepta and Drake voluntarily hopping on Wizkid’s Ojuelegba).

That’s not to excuse American Black music audiences. As a friend of mine in San Francisco told me recently, after I showed him a few of the above videos, “American Rap is too NFL, not enough NBA these days.” I couldn’t agree more.

Continuing on, if we take it out of the pop culture field into the political one, the BET awards issue reflects an interesting reality of the relationship between Blackness as defined by the USA, and the African diaspora at large. Anyone who lives in a major (or even not so major) American city knows about an inherent tension, both between communities, and within individuals when it comes to US notions of blackness, versus the cultures brought by black immigrant communities. The way individuals deal with these tensions often comes down to a question of assimilation or escape, or any combination of those two methods of social navigation. However politically, the tension between the experiences of Black Americans and immigrants are rarely resolved. Sometimes the two positions are even purposely placed in opposition to each other.

Extending that to the field of foreign policy, as an observer from far of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, mostly via social media but also from mainstream media, I can’t help but notice a lack of solidarity between Black Americans and their fellow African diasporans in places like Dominican Republic and Brazil, let alone the African continent. This is often justified via the need to account for the peculiarities of the Black American situation. The danger of this for Black American leaders, intellectuals, activists, and entertainers, is that they are allowing their politics (alongside their art) to be used to uphold one of the key tenets of American imperialism, the myth of American exceptionalism.

There is good news from on the ground, however. After spending about a month in the U.S., traveling from city to city, and talking to folks doing work in those places, I have noticed an awareness amongst American activists of a need for solidarity between places like Ferguson, Santo Domingo, Rio de Janeiro, and Luanda. This (like Wale) gives me hope. Still, it pains me when that these connections are absent from conversations in the mainstream. And that’s why I think that BET and this awards debate are also a good barometer for where mainstream Black America is at politically.

As African artists gain more and more success globally, using cultural platforms like House music and Hip Hop – innovations from of American Black communities – to assert their claim to an international stage of belonging, one can only hope that a sense of solidarity and affinity will start to form on both sides of the Atlantic. Africa has very little to lose in this game, and all the world to gain. The worst thing that could happen for American Blackness, in the global ascendancy of African Blackness, would be for American Blackness to be cast aside as a remnant of American cultural imperialism. Caught up in the rush to defend their position, the possibility of such a thing happening isn’t something that the executives at BET, or mainstream Black American politicians would ever even consider. So, maybe it’s time for all of us as black people to reconsider who our real representatives are.

July 22, 2015

The ‘Brazil of Africa': How development institutions are financing land grabs in the DRC

Below is an audio interview I conducted with Devlin Kuyek, Senior Researcher at GRAIN. GRAIN is a small international non-profit organisation that works to support small farmers and social movements in their struggles for community-controlled and biodiversity-based food systems. In the interview, Devlin talks about a recent report they put out that reveals how a Canadian agribusiness company, Feronia — financed by American and European Development Institutions, is involved in land grabbing, corrupt practices and human rights violations in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Kuyek traces the colonial origins of palm oil plantations in the DRC along the Congo River, dating back from the time of King Leopold and the Lever Brothers (which became Unilever), to present-day land grabs funded by Development Finance Institutions and sanctioned by the World Bank; a process which has occurred as part of a re-orientation of aid from poverty alleviation to straightforward investment in private companies.

Community members interviewed as part of the report claim that their land was never ceded to the company and that conditions on the plantations are abysmal. According to Kuyek, this type of large-scale intensive agricultural model that is expanding in different parts of Africa is deeply problematic, taking away valuable land and water resources from small farmers and pastoralists, and creating greater food insecurity in places that are suffering most from the global food crisis.

Here is an excerpt of my interview with Devlin:

Your recent report looks at what you call ‘agro-colonialism’ in the DRC, and specifically at a Canadian company, Feronia, that’s investing in palm oil plantations in the Congo. We think of agribusiness and land grabs more in a contemporary sense on the continent, but in the DRC there’s a whole history to palm oil. Can you go back a bit and give some historical context to palm oil plantations in the DRC?

Yes, many of the current land grabs are actually new companies taking over old plantation concessions. This is the case in the DRC with Feronia. These plantations go back over 100 years and were set up by the Lever brothers at the time, which became Unilever, now one of the largest food multinationals in the world. They were given an enormous concession by King Leopold along the Congo River, which is a beautiful area of forest. Palm oil is a traditional crop of the people and has hundreds of different uses. They started forcing people to collect and harvest palm oil for them. So initially it wasn’t plantation agriculture, but it quickly moved to a plantation model. Their concessions were for around 100 000 hectares. It was the most severe and grave forms of colonial plantation exploitation you can imagine. Most of the local people would describe it as slavery and this is how it was for about 80, 90 years. Then into the 90s, with war in that part of the Congo, Unilever’s activities started to decrease and they put their plantations up for sale. And you now have this new investor, Feronia, set up by financial players that have no experience in the agricultural sector, but were interested in taking advantage of the new push into agribusiness in Africa. They set up Feronia and were going to turn the DRC into the new Brazil of Africa, introducing a Brazilian model of GMO, intensive monoculture, large-scale farming in the Congo, which is a mainly a country of small-scale production.

In your report, you gave examples of people who have been intimidated by the company for harvesting palm oil in specific areas where there are plantations. There was also a case of a young man who disappeared. Can you talk about some of those incidents?

Whoever we spoke to, one of the first complaints they had was about the local company security. These concessions are like states within a state. The company controls everything – the roads, the social services and their own police force. All of the people that we spoke to had stories of intimidation or abuse from these company security agents. What often happens is, given the poverty and lack of access to land and forest, people will occasionally collect nuts that have fallen in the plantations and apparently, if they are caught by the company security forces with nuts in their hand, they are severely treated. We’ve heard cases of people being whipped, arrested, brought to local prison and in this one case, we were told of a boy who was caught with oil palm nuts and was detained, put on a company vehicle and was supposed to be brought to the local police station, but never made it. He has not been heard of since. The family was afraid that they would be targeted and harassed so they fled as well and have been in hiding ever since.

Listen to the entire interview below:

July 21, 2015

#RespecTheProducer – Tweezus, Da Gawd!

When the skhothane scribe-in-chief Rofhiwa Maneta called producer Tumelo Mathebula one evening around 7 o’clock, the last thing he was expecting was the hit-making, versatile tweaker of knobs to be on the way back from an all-day studio session. “I’m actually on the road right now,” he said. “But it’s all good. Let’s talk.” What follows are Tumelo’s thoughts, filtered through telephone static and channeled through Rofhiwa’s writhing pen. #RespecTheProducer

*

Mathebula, more commonly known by his production alias, Tweezy, saw his ascent into South Africa’s mainstream hip-hop scene come full circle last year. He’s responsible for crafting three singles off AKA’s award-winning album Levels. If you’ve ever found yourself snapping your neck to Run Jozi and Sim Dope or doing the nae-nae to All Eyes on Me [which received the Best Collaboration accolade at the MAMAs], he’s the guy you should be thanking. And while it would be tempting to call him an overnight success, the truth is 2014 was the end result of years of knocking at the mainstream’s door.

“I started producing in 2008,” he recalls. “Back then I was just fooling around with FL Studio. It was really just a hobby. I only started taking it seriously a couple of years later.” In 2010, under the production moniker N20, he and seven of his high school friends formed a crew called Ghetto Prophecy. The crew announced their arrival with an EP called The Book of R.A.P – an announcement that was largely ignored by the rap scene. By the time they released their second offering – The Book of F.A.D (Faith and Dreams) – two years later, the group had whittled down to four members. “It was a bit disappointing. We were about to drop the project but people had to leave the crew due to other commitments.” The leaner crew consisted of him, Butho Ntini, Shakes “Sheezy” and (now) Cape-Town based rapper E-Jay.

While their first EP amounted to little more than a whisper, The Book of F.A.D was a reverberating shout at the mainstream. The album spawned three singles: Oh My (which was playlisted on Metro FM and YFM), “Great” and “Get the Party Started” (both playlisted on YFM). Even though he won’t admit it, he was the nucleus that held the group together. His versatility as a producer meant that the crew could never be accused of sounding monotonous. “Great“ for example, with its neck-snapping drums and gospel sample is a [Kanye West’s] “Jesus Walks”-type cut that saw the crew praying against the vices that mainstream success would offer. “Oh My“ – the crew’s biggest single – is a rap ballad that sees the crew crooning about finding “the one” while “Skothane se Rap”, is an archetypal “turn up” joint with a military drumline, staccato string section and rattling 808s that would easily fit into any nightclub’s Saturday night playlist.

“The response to The Book of F.A.D was amazing. It made me realise that I could actually make this rap shit happen. That’s when I stopped making music for myself and started making music that everyone could enjoy.” And while he appreciated the reception The Book of F.A.D generated, he felt it was time to start getting his name out as a solo act. He would continue producing for E-Jay (lacing him with the hard-as-cement “Baleka Mrapper” and lending a verse on the joint) while also handling the production duties on Bloemfontein-based crew The Fraternity’s “Bheka Mina Ngedwa“. It’s at this point that a mutual friend introduced him to AKA. “I rang Kiernan up and we met two days later. I played him about ten beats and I thought he’d take at least half of them. He didn’t take a single beat,” he laughs. “He was like ‘man, your beats are dope, but they’re missing something. But I wasn’t going to take no for an answer. I had to get onto his album no matter what”

The next few months saw him hopping between different studios (he didn’t have a PC to produce on at the time), perfecting his craft. “There’s this one beat in particular that took me three weeks to make. Laying the drumline was simple enough but the melodies didn’t sound right. I spent three weeks reworking the melodies exactly how I wanted them to” he recalls. That beat would later turn out to be AKA’s chart topping “Run Jozi”. With a chorus that channels TKZee’s “Sikelela”, a classic skhanda verse from KO and verses from AKA that employ Migos’ now-ubiquitous machine gun flow, the beat served as the centre of gravity that held all these divergent styles together. Similarly, All Eyes on Me (featuring continental superstar Burna Boy) samples the late Brenda Fassie’s “Ngiyakusaba” and reworks it into a bass-heavy party anthem reminiscent of the Bay Area sound popularized by DJ Mustard.

“It’s quite funny how that joint came about,” says Tweezy. “I was at home watching Mzansi Magic one Saturday and they were airing a Lebo Mathosa vs Brenda Fassie playlist. So “Ngiyakusaba” comes on and I immediately thought it would make a great sample. It’s weird because Kiernan called me a few minutes later and told me he was watching the same playlist and wanted me to sample the joint. That was all the confirmation I needed. I was done with the beat in half an hour.” The rest, as they say, is chart-topping history.

His work on Levels hasn’t gone unnoticed. Last November, he earned a nomination for Best Producer at last year’s South African Hip Hop Awards. But while he was flattered by the nomination, he felt he didn’t have an extensive enough catalogue to bag the award. “I knew I wasn’t going to win. I mean, last year Ganja Beatz [the eventual winners] produced half of Cassper’s album and so many other joints. They deserved it.”

Tweezy is still riding the crest of Levels’ success. A little over a month back, the album was certified gold and recently a video was released for “Sim Dope“, which is still enjoying regular airplay. He’s also responsible for the production on L Tido’s “Dlala Ka Yona” and recently roped in Reason for a solo release called “The Realest“. “Last year was cool, but I still have so many artists I plan on working with this year. I want to achieve way more this year; 2015 is going to be Tweezy year.”

On Music, Tradition and Race: Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto take Brooklyn

When I was a kid, my dad, my stepdad and one of my dad’s friends sometimes helped organize concerts in Bogotá for this band called Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto.

San Jacinto is a small town in the Bolívar region, in the Colombian Caribbean, not too far from Cartagena, and a gaitero is someone who plays a gaita (a word which also means “bagpipe” in Spanish), which is a long, wooden flute-like instrument, topped by some bee wax holding a small straw made from a duck’s feather (or plastic, sometimes).

The concerts were always held at small venues in dark, empty streets, that I shouldn’t have been allowed into, and they tended to start at a time when I probably shouldn’t have been awake. But, despite my young intolerance to late nights, I did my best to stay up, because I was constantly mesmerized by the sound of these men, the intricate banging of their drums, the dexterity with which they played maracas, the high-pitched, yet subtle gaitas commanding the orchestra, and the honesty with which every song was sang: how true their voice sounded, how it made me feel like I was in the depths of La Costa, tending to my animals and dedicating love poems to girls, even though I had never been in that position.

Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto have been playing since 1940, and have bestowed their name and musical traditions upon generations of sons, grandsons and apprentices. For the past seven decades, they have toured Colombia and the world, bringing to audiences the original sound of cumbia, a genre that has traveled far and has evolved in different countries (like Mexico, Peru, Argentina and others) into true national folklore, but whose roots remain popular.

After one of their concerts in Bogotá, my stepdad was gifted two gaitas which we kept in our living room. One of them had three holes at the bottom, the other one had five. I remember being frustrated because my arms weren’t long enough to cover all of the holes. On the one with more holes I could manage some sounds, but the other one was impossible for me. One time, one of the gaiteros explained to me the differences between both types of gaitas: “there are female and male gaitas,” he said, “and the female gaita is of course the one with more holes!” It took me a few years to catch that joke.

Gaitas are indigenous instruments, played for centuries by the Koguis and Arhuacos of what is now northern Colombia. But the drums used by Los Gaiteros – alegre, llamador and tambora – are distinctly African. This makes sense: Cartagena was once the biggest slave port of the American continent. Many aboriginal tribes thrived not far from it, and survived despite’s the Spaniards best efforts. And it is perhaps in the music of such places (and not only cumbia) where lies the truest instance of the “mix of cultures” tale we Colombians tell ourselves (sometimes to hide our racism towards Afro-Colombians and indigenous people).

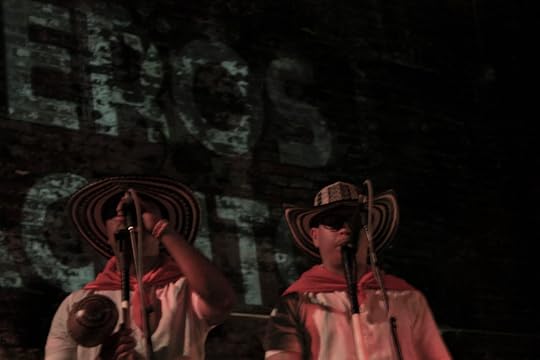

So I was excited when I found out that Los Gaiteros would be part of the amazing Afrolatino Festival of New York, and that they would be playing in Brooklyn, where I now live. Daniela Valero (a wonderful Latin America is a Country contributor) and I were lucky enough to get an interview with the current line-up (which you’ll be able to see soon!) just before their set at a venue in Bushwick. It was the largest place at which I had seen them play, and it seemed like an ocean of people was present, ready to dance to every intonation these men had to offer.

One time, back in Bogotá, one gaitero came near my dad’s friend during the after-party of a concert and told him “you know what? Don’t pay us money today. Just don’t leave and give us more rum!”. Maybe he was being facetious – my sense of humor hadn’t developed yet, if it has developed at all – but that set the tone for me for every time I heard Los Gaiteros’s music: it was, more than a performance, a communal celebration, more than a service, a party with close friends.

In Brooklyn, led by the wonderful voice of maestro Rafael Castro, Los Gaiteros performed most of their classics, some songs composed by the newest generation, and even debuted a song penned by Castro himself. At some point they also brought out a clarinet, a definitive instrument for cumbias from the 60s and 70s that have become staples of any Colombian party, and that were also performed in this show.

In Brooklyn, led by the wonderful voice of maestro Rafael Castro, Los Gaiteros performed most of their classics, some songs composed by the newest generation, and even debuted a song penned by Castro himself. At some point they also brought out a clarinet, a definitive instrument for cumbias from the 60s and 70s that have become staples of any Colombian party, and that were also performed in this show.

It seemed to me that all of Latin America was there listening to them, and everyone I saw or spoke to seemingly agreed that we were seeing something remarkable. It was definitely the best show I’ve seen Los Gaiteros perform. This one started as late as those in Bogotá. But by the end of this, I was pretty much awake, and just as happy.

(All of these pictures were taken by me at the day of Los Gaiteros concert in The Wick, Bushwick, including those below):

July 18, 2015

Weekend Music Break No.81

Your weekend music break for July 18th, 2015

This week, master of the new school J. Martins, and master of the old school Koffi Olomide team up in Dance 4 Me, the remix; A busy week for Jidenna who angers Nigerian Twitter, apologizes, and then links up with Kendrick Lamar for the classic man remix; Holy Forest offers an impressive collaboration connecting different nodes in the Black Atlantic with “Africa Calling”; Kollins and Toofan link up for an Ivorian-Togolese party jam called “Crazy People”; Sierra Leonean crooner Famous sings on a London rooftop in “Throway”; Emicida, Inna Modja, and Killah Ace offer up political rap stylings; Tumi provides some more party rap offerings with “Visa”; and finally, top Jamaican artist Popcaan releases a new video this week called “Way Up”.

July 17, 2015

A complete run-down of all the craziness going down in Kenya ahead of Obama’s visit

Kenyans are not known for their reserve. Not at all, but for some reason, as my cousin said, “Obama’s visit is bringing out all the crays in this country.” The unbridled crazy that has been paraded for our senses since POTUS declared he was coming to Kenya from July 24th to 26th is, indeed, truly bizarre.

Today the Siaya county governor has taken out a full page advert in a national daily to advertise an expo in honor of their “returning son.” This expo is also set to feature a half marathon and rugby matches with a team definitively called the “Obama Sevens.”

Not to be outdone 18 University of Nairobi students have said they are going to kill themselves and 31 female students said they would urinate on the tree that Obama planted last time he was there in 2008 if he does not visit the university. Secondary school students at Senator Obama Secondary School are imploring for Obama to visit them and fittingly change the school name to President Obama Secondary School.

I was recently sent a picture of a fresh sign by a mganga (which in anthropologist lore is witchdoctor) who advertised his ability to ensure you win the sports lottery, get back your lover and to help you greet Obama.

In addition, every day there is reactionary talk in the newspaper about homosexuality because, apparently, this is all Obamas fault. This happens on two fronts. Either some really fundamentalist view by the Deputy President, or declarations from the, seemingly, recently formed Republican Liberty Party which has declared that just for POTUS, and due to his “open and aggressive support for homosexuality”, 5000 naked men and women are going to hold a two day rally in the city on both the 22nd and 23rd of July. This is done so that Obama, in case he is not already aware, can know the “difference between a man and woman.” Related, the council of Kikuyu elders have even said that they will pelt Obama with rotten eggs if he “tries to push for homosexuality in Kenya.”

Luckily, though sadly not with the same proliferation, there are more progressive views about how every leader should just mind their own business, focus on their own bedroom and let every Kenyan have their human rights.

There are also comical and subversive interventions about who the “real homosexuals” are in the country, one of which has succeeded in establishing a new word; “homo-sexed.”

What is certain is that post ICC and election violence provoked western media fanfare and subsequent NGO industry and social entrepreneurship fetishization (they seemed to replicate everywhere at that time) I don’t think Kenya has seen this many white people in a while. Especially since Westgate.

They will all be welcomed by the gubernatorial sanctioned “beautification” project for the city of Nairobi which costs 50 Million shillings (about $500,000) and that is launched just in time for Obama’s visit. A key part of this project seems to be the planting of flowers that, if they actually grow in time, will likely wilt and gather dust soon after POTUS is gone.

Caught in the heat of this melee, are the street families who are being “pushed” out of the city because Obama is coming, and swept under the carpet for the next two weeks are the real issues we should be attending to; food, land, justice, security, employment, teacher’s wages and dignity.

Likely there will also be more illegal detentions, arrests and police everywhere — if more police in Kenya is even imaginable. We will barely, if at all, be able to use many major roads or, according to word on the street, make a phone call for three full days.

Whether he is coming to “have the opportunity to meet some of the brilliant young entrepreneurs from across Africa and around the world” or to announce “new investments and commitments.”, with slightly more than a week before POTUS jets in it is likely that it is only likely to get more crazy in here, that the next few days will bring out more “crays,” if that is even imaginable.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers