Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 337

July 3, 2015

A meditation on that space I need for my rage, or, an independence manifesto

The space I need for my rage was taken from me long ago. I have spent the better part of my adult life recognizing both its social and personal absence with fierce determination to carve it out as I attempt to re-learn my entitlement to it and experiment with ways to express and relish in it especially on the stage.

Years of talk therapy have taught me the extent to which my conditioning influenced how I behave and negotiate this world in which I live. In this white world, as a black (Haitian) woman, I have had to negotiate my blackness within African-American communities where my additional otherness is invisible. We do not always see each other or align collectively around shared struggles. I am past the age and or the phase where this tore me up as a young immigrant in this country. I made peace with the reality that in the expanded scope of racial hierarchies, my race/color precedes my national identity. I became a U.S citizen a decade ago. I am simply black in the face of the white power that I sometimes dread for the ways that it categorizes and seeks to destroy blackness as some misappropriate it as CG writes, while others keep that blackness in an unhealthy state of awareness that denies us a social luxury of being, precisely because, as June Jordan puts it, “I am the wrong skin.”

The first thing I did the morning after the massacre in Charleston — I went for a run. An observer, from not so far away in CT, these times have been trying. I watched events surrounding the capture of Dylann Roof developing in the news while upholding an all too predictable narrative and quickly became conscious that my heart was beating too fast, faster than usual. The urge to run while standing still is a feeling I have come to associate with another anxiety that I have had in those moments when fear is setting in and there is no place to run for cover. I had an appointment but simply did not want to go outside. (Indeed, it dawned on me that I first fully absorbed this feeling in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.) I did not want to leave the comfort of my home space and risk an encounter with anyone in denial about the targeting of black bodies and the state of racism in this hemisphere, and in the world.

As the families of the AME9 victims forgave the killer of their loved ones, I retreated in a combination of awe, respect and self-protection. I had neither the religious conviction nor faith to take this high road anymore than I could so clearly express its opposition as Roxanne Gay so poignantly did. I was preoccupied with the fact that this was taking an all to familiar physical and emotional toll, which has become conversation on my FB and Twitter feeds of late. Advice and notes about ways to be vigilant about self-care in these times. Ways to circumnavigate the psychic violence from a terror so close and so random that it will re-trigger and re-traumatize us as we live, knowing as Hari Ziyad asserted: blackness cannot be saved. But we can try to take care of ourselves to assure its collective survival. Anti-blackness knows no geographical boundaries. For Harriet wrote “If #BlackLivesMatter, we need to talk about the Dominican Republic” as she urged us to “Breathe. Heal. Organize. Because Ferguson is New York, is Baltimore, is Santo Domingo, is Port-au-Prince.” Stateless citizens are self-deporting. Living in limbo. The current situation in the DR is a time bomb that’s getting ready to blow as Jonathan Katz recently wrote in the NYT. And churches are being burned again and again keeping all of us on alert. There is a target on our back. Thisismyback.org (please don’t shoot) calls on us to: “make some noise around a situation that has gone from unacceptable to unbearable. More overwhelmed every day by the unrelenting and unapologetic brutality against people of color, we have had enough.”

If there is one thing that I have learned from my years of therapy, healing is a process that takes its time. It cannot be rushed and it certainly cannot begin when wounds are still open. Still bleeding. Indeed, unprocessed trauma will become archived in bodies unless it is recognized, faced, confronted and worked through. Not everyone has the luxury of time and resources to commit to our certain types of self-care and protection, which is paramount to weather living with this ongoing terror. Audre Lorde said it best “caring for myself is not self- indulgence, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare.”

Full expression of our humanity, rage included, remains a site (too often) of (deadly) contention. We should be held not responsible for the social limits and ideologies that undergird legal structures, which reduce us to mere caricatures and stereotypes. It took me a long time to learn that I have as much a right to individuation as anyone. For me to live, the space I need for my rage has become non-negotiable. I no longer have any desire whatsoever to debate anyone about it. My aliveness and spirit depend on it so I can keep trying to do to this life thing, despite the fuckery, with some meaning, and a lil swag, albeit on my terms.

“Permanent readiness for the marvelous”

–Suzanne Césaire

July 2, 2015

Echoes of Zaire: Popular Painting from Lubumbashi, DRC

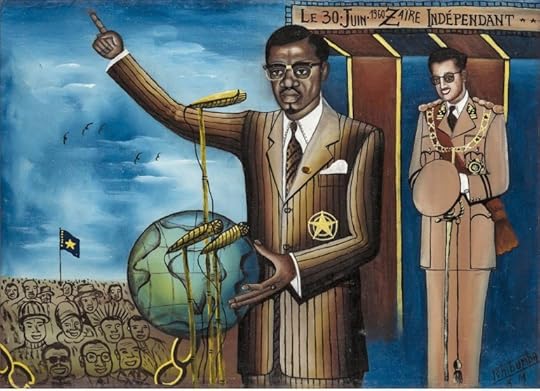

In the 1970s, a Congolese painter named Tshibumba Kanda Matulu began to paint a history of what was then Zaire. This history, as the anthropologist Johannes Fabian pointed out when he collaborated with Kanda Matulu on a book some years later, was “not just a story, but an argument and a plea.”

History is of course never “just a story,” and the extraordinary exhibition 53 Echoes of Zaire that just opened in London, showing some of these paintings by Kanda Matulu and four other painters from the Congo, makes very clear that these painters’ version of history is indeed an emotive, impassioned plea to tell their side of the story, to insert narratives into the vacuum left by official versions of history that circulated at the time.

The exhibition was curated by Salimata Diop from the Africa Centre in London in cooperation with the Sulger-Buel Lovell gallery. It comprises 53 paintings by artists Louis Kalema, C. Mutombo, B. Ilunga, Ndaie, and Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, belonging to the Belgian collector Etienne Bol whose late father Victor Bol collected these works while spending time in Zaire in the 1970s.

The artists are all self-taught and the exhibition shows a series of works all executed in a style similar to what is sometimes called the Zaire School of Popular Painting. The most famous of this so-called school is probably Chéri Samba, who shot to fame after he was included in the Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of Earth) show at the Pompidou in 1989. These works are painted on flour sack rather than canvas, often with a limited palette of poster paints and with thick brushes. But whereas Samba and his colleagues from Kinshasa tend to record everyday events, the works on the current show are all from painters around Lubumbashi, in the south, with a focus on historical topics. This is probably as much the result of the collector’s keen eye as anything else – the catalogue tells us that these works were made for a local audience and were mostly sold to local people, so one may surmise that these artists probably also painted genre paintings for a local clientele.

The artists are all self-taught and the exhibition shows a series of works all executed in a style similar to what is sometimes called the Zaire School of Popular Painting. The most famous of this so-called school is probably Chéri Samba, who shot to fame after he was included in the Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of Earth) show at the Pompidou in 1989. These works are painted on flour sack rather than canvas, often with a limited palette of poster paints and with thick brushes. But whereas Samba and his colleagues from Kinshasa tend to record everyday events, the works on the current show are all from painters around Lubumbashi, in the south, with a focus on historical topics. This is probably as much the result of the collector’s keen eye as anything else – the catalogue tells us that these works were made for a local audience and were mostly sold to local people, so one may surmise that these artists probably also painted genre paintings for a local clientele.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue that has reproductions of all the paintings, but unfortunately does not tell us much about individual works. Granted, very little biographical information about these artists is known and none of them could be found in the lead-up to this exhibition – we don’t even know if they are still alive. Efforts to reach Kanda Matulu – by far the most proficient of the group – have been unsuccessful; his last works date to 1982–83. But the catalogue does not explain or contextualize individual images or events, and viewers are left piecing together the history for themselves. This is a shame, as these works were clearly meant to inform and educate their viewers. It would be nice, therefore, to be able to partake in this project knowing more about the incidents being memorialized and their significance in this indigenous history of the Congo.

It is quite interesting, for instance, to know that the aforementioned academic and anthropologist Johannes Fabian published a book in 1996 containing a series of a hundred history works by Tandu Matulu, entitled Remembering the Present. The two became friends in 1973 when Tandu Matulu was around 27 years old and needed a sponsor to execute his aspiration to tell the history of Zaire in a series of paintings, rather than stick to the genre paintings so popular with the local public. Fabian mentions that while he and Tandu Matulu were working on this project from 1973–74, he “found amongst my expatriate colleagues a few buyers for several shorter versions of this series.” This is probably how Bol acquired his collection.

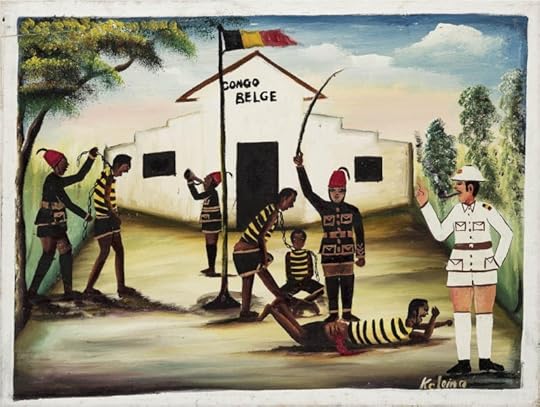

Several works from Fabian’s book are repeated in Bol’s collection, making it clear that the artists repeated the same images, focusing on key episodes. The exhibition is organized around five themes representing Belgian colonization, the mines around Shaba (now Katanga), the independence of Zaire, post-independent moments of conflict, and the pre-colonial past. Clearly these painters are imaging a shared system of memory. The same image crops up over and over again under the heading “Congo Belge” (Belgian Congo): a white official in a white safari-style uniform overseeing a black uniformed man, whip in hand, flogging a black subject lying on the ground in front of him. Often women in traditional dress are onlookers, and in quite a few works black subjects have chains around their necks. These are images of such horrific dimensions that they are ingrained in the popular imagination; memory becomes a people’s history.

Several works from Fabian’s book are repeated in Bol’s collection, making it clear that the artists repeated the same images, focusing on key episodes. The exhibition is organized around five themes representing Belgian colonization, the mines around Shaba (now Katanga), the independence of Zaire, post-independent moments of conflict, and the pre-colonial past. Clearly these painters are imaging a shared system of memory. The same image crops up over and over again under the heading “Congo Belge” (Belgian Congo): a white official in a white safari-style uniform overseeing a black uniformed man, whip in hand, flogging a black subject lying on the ground in front of him. Often women in traditional dress are onlookers, and in quite a few works black subjects have chains around their necks. These are images of such horrific dimensions that they are ingrained in the popular imagination; memory becomes a people’s history.

Another popular topic repeated by a few of the artists is the beheading of Msiri, the king of Katanga, by King Leopold’s army in 1891. Some official European histories published in France related that after Msiri was killed by gunfire, his head was put on a pole as a lesson for his people. Indigenous oral history relates that Msiri’s body was returned to them without a head and no one knows what happened to the head. The exact details are imprecise, but it is clear that this episode plays an important part in the popular narrative about colonial occupation and resistance.

The works of Kanda Matulu clearly stand out, so often showing a wonderful eye for detail and a gift of observation here: the uniforms of colonial officials is painted in precise painstaking detail in his “Colonie Belge 1885–1959” (also repeated in Fabian’s book), buildings reveal an architectural sense of structure, and his many portraits of Lumumba are unmistakable likenesses. The black-and-white portraits of Lumumba in particular – probably taken from newspaper photographs – are some of the most interesting in the exhibition and reveal Matulu’s keen interest in aesthetics and representation. His works are richly annotated, similar to Cheri Samba’s, so as to inform his audience unambiguously about whatever he is referring to and how these images should be interpreted. This sentiment – so foreign to the Western art world, which is probably why Chéri Samba remains so popular in the West – reveals how much these works are intended to document and memorialize, to stand testimony to a history all too willingly forgotten.

The works of Kanda Matulu clearly stand out, so often showing a wonderful eye for detail and a gift of observation here: the uniforms of colonial officials is painted in precise painstaking detail in his “Colonie Belge 1885–1959” (also repeated in Fabian’s book), buildings reveal an architectural sense of structure, and his many portraits of Lumumba are unmistakable likenesses. The black-and-white portraits of Lumumba in particular – probably taken from newspaper photographs – are some of the most interesting in the exhibition and reveal Matulu’s keen interest in aesthetics and representation. His works are richly annotated, similar to Cheri Samba’s, so as to inform his audience unambiguously about whatever he is referring to and how these images should be interpreted. This sentiment – so foreign to the Western art world, which is probably why Chéri Samba remains so popular in the West – reveals how much these works are intended to document and memorialize, to stand testimony to a history all too willingly forgotten.

For this reason alone – and many others to do with the works’ cohesion– one hopes that the collection is sold to an institution open to the public. This is a powerful document that needs to be seen in its entirety.

For this reason alone – and many others to do with the works’ cohesion– one hopes that the collection is sold to an institution open to the public. This is a powerful document that needs to be seen in its entirety.

The exhibition 53 ECHOES OF ZAIRE: POPULAR PAINTING FROM LUBUMBASHI, DRC is on view from 27 May – 30 June 2015 at Sulger-Buel Lovell gallery, London, UK.

Colombia and the search for truth in Latin America’s longest running conflict: lessons from the South African experience

Negotiators from both sides of Colombia’s longest running war met last month in Havana, Cuba, for the 37th round of peace talks. The primary outcome of these talks was an agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebel group to establish a truth commission, an agenda point which has been in discussion for approximately a year.

The agreed upon mandate of the commission is for it to facilitate the “construction and preservation of historical memory and achieve a broad understanding of the multiple dimensions of the truth of the conflict” and “lay the foundations of coexistence, reconciliation, and non-repetition.” Uncovering truths buried by 50 years of war, which has claimed an estimated 220,000 lives, will be a formidable task. Moreover, the commission’s establishment is contingent on both parts signing a final peace agreement; which, after two and half-years of negotiations, is still some way off.

For the past few weeks, negotiations have been ongoing without an official cease-fire. FARC revoked their unilateral truce on May 22nd, after aerial bombings and raids by government forces killed 40 of their members. These actions where in reciprocity for an attack by FARC on a government military column the month before, which killed 11 soldiers.

Despite these setbacks, ongoing negotiations have made some considerable achievements: both sides have signed preliminary accords on political participation for the opposition, reforms on drug policy, and rural development. However, perhaps the most difficult issues for negotiations still lay ahead: the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of combatants; and a reparations framework for victims.

The recent agreement to establish a truth commission is another positive step towards the chance of a lasting final peace in Colombia, and other elements the negotiated settlement will be contingent on its success. Whether this peace comes in a year from now, or five, it is better to begin a conversation now on what a Colombian truth commission should seek to achieve. In doing so, lessons can be learnt from both the successes and failures of the South African experience.

The current social climate in South Africa—with its heated contestations around cultural symbols, outbursts of xenophobic violence and malignant political stage—may encourage one to overlook the successes of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Without some ordering of the past, former belligerents cannot begin to look to developing a peaceful and shared future. In this regard, the TRC was successful in beginning the important project of creating an authoritative historical record. It brought long-standing enemies together around the same table, provided an important platform for victims to tell their stories, and was responsible for providing a measure of accountability to victims. The TRC also provided us insights from which to build more nuanced corrective structures and legislation. Two clear markers of its success are that firstly, no civil conflict has broken out. And secondly, the TRC has become a model for a number of African states trying to transition to and consolidate their own democracies.

Perhaps a lesson from the TRC most applicable to Colombia revolves around the issue of amnesty. A crucial decision the country will have to make is whether those found responsible for crimes revealed through a truth commission, should be granted amnesty. The joint report outlining the recent truth commission agreement makes no mention of this issue, but states that the commission will be an extrajudicial mechanism; meaning its activities will have no legal basis, will not involve any criminal charges against those who appear before it, and information received during hearings cannot be transferred to judicial authorities.

In Colombia, this has been a heated political debate. The right-wing opposition to the peace talks, lead by former president Álvaro Uribe (now a senator), has constantly put pressure on media and Congress to claim for long prison sentences. This has forced current president Juan Manuel Santos to repeat often that there will not be “impunity in the peace agreement.” But the divided rhetoric, and the renewal of FARC attacks, has lead many sectors of Colombia, supportive of the peace talks, to ask for a time limit to it.

There is a natural trade-off between the need to encourage national unity on the one hand and fighting impunity on the other. Despite its number of troops being stale, FARC still holds many military advantages in the country, and it seems unlikely that it will keep the peace if the government seeks prosecutions. However, failing to address impunity can rob victims of a sense of justice, it does not help to encourage a just and equitable society, and it creates stumbling blocks for reconciliation. South Africa pioneered a third way where instead of a blanket approach, amnesty was only granted on the condition that perpetrators fully disclosed their crimes. Tying amnesty to the truth commission in this way could effectively be utilized by Colombia.

South Africa had little time for consideration before establishing the TRC. With hindsight, the commission’s failures become clearer, and lessons can be learned. Like a Colombian commission would, the South African TRC had to uncover and document stories pertaining to decades of violence; established in 1995, and delivering its final report in 1998, it had only three years to achieve this. Logistically, this was simply impossible. The decision to not keep the commission operative in an ongoing capacity has meant that thousands of important South African stories will never be heard. Furthermore, it has closed a still very much needed avenue for social dialogue around contentious issues. The Colombian report has specified that the commission will, including production of its final report, run for three years. Uncovering the truth is not an end in itself but should be seen as a part of an ongoing dialog towards reconciliation. Giving a truth commission a time frame of just three years risks rushing a process that should be seen as open-ended.

By focusing on the relationship between political perpetrators and individual victims, the TRC also failed to give enough attention to the underlying socio-economic conditions created by centuries of inequality. South Africa is slowly realizing that political reconciliation has not translated to economic reconciliation.

While the focus on overt forms of violence and civil conflict is understandable, creating lasting peace through inclusivity cannot truly be achieved without giving proper attention to the structures which generate social antagonism, and which are often themselves implicitly violent. Colombia’s truth commission will therefore have to find a way of addressing FARC’s key grievances around land ownership and economic opportunity in the territories. To this end, in addition to political actors, the role of institutions and business in both recent and historical causes of Colombia’s conflict needs to be central to hearings.

The released joint report outlining the mandate of the proposed Colombian truth commission has “committed to ensuring the mainstreaming of gender in all the scope of its work, with the creation of a working group to contribute to gender specific technical tasks, research, preparing gender hearings, among other.” The fact that gender is already being considered is a positive sign.

The South African TRC failed terribly in this regard. Questionnaires which victims claiming for reparations had to answer in front of official TRC statement takers (and which statement takers were ordered to closely stick to) contained no questions relating to gender based violence. This meant that, for example, a woman raped by apartheid security officers could not even get this on an official record. Furthermore, these statement takers, quickly trained by the TRC to take victim reports, were often woefully ignorant on conducting gender sensitive interviews.

Violence resulting from conflict often falls especially heavily on women and LGBTI individuals. South Africa missed an opportunity to begin to address deeply entrenched and gendered social structures which contribute to the country having some of the highest levels of gender based violence in the world.

Most crucial to the success of any truth commission is whether the government is willing to act on its recommendations. The South African TRC recommendations were largely ignored by the Mbeki government. Commission findings may call for the establishment of programmes and commitment to changes which outlasts the term of a single president or political party. If a truth commission and its subsequent recommendations becomes politicised, rather than a social commitment this transcends political patronage, it is bound to fail. Colombia will have to find a way to maintain the social and political will needed to support their truth commission and fulfil its recommendations.

Uncovering the truths behind more than 50 years of war will be a pain-staking process, but it is a crucial endeavour in order to ensure the future coexistence between rivals, non-recurrence of conflict, and ultimately, reconciliation. Former adversaries need to view a truth commission not as mechanism for the vindication of cause and attribution of blame but as an opportunity to see in the “other” the mutual loss and suffering such a war has wrought on all.

Follow Latin America is a Country on Twitter and .

July 1, 2015

Africa is a Radio: Season 2, Episode 5

Discussion on this episode of Africa is a Radio features a report back from Sean Jacobs on his recent trip home to Cape Town, a discussion on Kagame’s Rwanda and its relationship to the international courts, and finally a visit to the Americas centering in on Charleston, South Carolina and the Dominican Republic. The music selection from Chief Boima touches on all these corners of the world and more.

June 30, 2015

Japanese Designer Goes Full Rachel Dolezal at Paris’ Museum of Immigration

While we were busy celebrating a Supreme Court decision this week (we can’t make this up – CNN reported that a black and white flag held aloft by revellers in London was an ISIS flag. It turned out they mistook a graphic of dildos and buttplugs imprinted on the flag for Arabic; the original video of reportage has now been taken down), and Bree Newsome’s ascent up South Carolina’s statehouse flagpole to remove the state’s Confederate flag, a fashion show took place. Like most fashion shows, no black models were in evidence at Japanese designer Junya Watanabe’s show at the Museum of Immigration. In light of landmark decisions recognising equality, as well as the ongoing struggle to remove dehumanising symbols, why does something as inane as a runway full of white models matter?

Véronique Hyland was the first to describe the problem in NY Mag and reach out to the designer’s people for comment:

Japanese designer Junya Watanabe showed his men’s collection in Paris today, at the Museum of Immigration. The collection drew on African influences — including colorful Dutch wax fabrics and Masai-style layered necklaces — while managing to feature exactly zero black models. Much noted on social media was the hair — several white models appeared to wear dreadlock wigs. (Watanabe has done this before, as seen in his spring 2014 women’s collection.)

The space of the Museum of Immigration has its own problematic colonial history, contributing to this modern narrative of oogling otherness as the primary means of constructing one’s own subjectivity whilst deriding and erasing the other. Architect Albert Laprade famously collaborated with Léon Jaussely and Léon Bazin in building Palace of the Colonies, the Palais de la Porte Dorée for the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition in which zebras, snakes and other ethnological wonders were exhibited. The Cité nationale de l’histoire de l’immigration is now housed within the Palace.

But no one really talked about the location, because the gigantic braids-and-dreads wigs worn by Watanabe’s models sort of blinded commenters on Twitter:

who wore it best: junya watanabe s/s 16 or rachel dolezal? pic.twitter.com/Z7ISApz6d6

— Four Pins (@Four_Pins) June 26, 2015

Shoutout to Junya Watanabe on his Rachel Dolezal collection http://t.co/AzsA0OvKqt pic.twitter.com/RwzGzo6sot

— Marcus Jones (@MarcusJonesNY) June 26, 2015

We’ve said the obvious before. But every fashion season (and every wedding season), it seems we need a reminder: appropriation of blackness in order to ooze cool is exploitative, plain and simple. Attempting to reproduce, imitate, or otherwise artificially signal black physical traits, or pile on prominent “tribal” jewellery that instantly associates white tourists with a trip to Maasai Mara or some mythical “Zululand” is a problem. Why? Because actual black people don’t get to mix and match their physical traits in order to show that they are culturally powerful on one day and abandon blackness the next; even more importantly, they have to grow up with the day to day and systematic oppression that those traits bring in worlds that are largely run on white supremacist principles. These are worlds that view anything to do with blackness (including braids and jewelry) as inferior.

But yes, we know, European and American people sometimes want to show that they like these nice, African things. What’s wrong with homage? As Chimene Suleyman noted so succinctly in Media Diversified year last, “What happens with appropriation is a suggestive scalping, a vogue bounty hanging from trendsetting bridle reins”. When there’s not even one black model on that runway, the exploitation and exoticism of “native” Africanness is made even more plain: we love your colourful garb, but we wouldn’t want you to be employed and present here. If you were, that would mean that this stuff isn’t really meant for us to take as we want. Also, if you were here, we wouldn’t really look good with braids and dreads.

Vogue.com tried to explain the lack of black models with this possibility:

…the decision to use only white models may have been in order to communicate a message about colonialism, some suggested, especially since the collection was created in collaboration with Vlisco. The Dutch company, which has supplied fabric to West and Central Africa since the mid-19th century, is considered instrumental in having shaped the region’s cultural identity, Style.com reports, with British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare using the company’s fabrics in his work to challenge Western colonial history.

Amazing how Shonibare’s brilliant questioning of “authenticity” and “native purity” could be derailed by a fashion writer, who explains here that his is a simple “commentary” on colonialism. But what exactly is the comment? Is it just that “colonialism exists”? And that when colonialism happens, black people disappear, and their cute stuff gets appropriated by those who colonised them?

And that wasn’t the end of the absurdity. NowFashion noted that the “patchworking” was vintage-true of Watanabe’s style, where the “[t]ypically Western fabrics competed for attention with wax prints, wools, with linens.” Ok, that’s so nice. But then we get the horrible emptiness we come to expect of fashion writing, which almost moves towards critiquing racism and sexism, but quickly giggles and then dismisses it away in cringe-worthy pseudo-theorising:

At first, it seemed as if the Ivy Leaguers had gone native in the Museum of Immigration, built in 1931 by Albert Laprade. Much like Vampire Weekend’s “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa,” Watanabe’s collection reflected on colonialism, and exploited the in-roads between preppy and native African culture. From last winter’s Sapeurs re-appropriating Western masculine codes to this season, the parallel felt natural…Much like the African man in his traditional outfit looking down onto an apparently preserved landscape, Watanabe usually reflects on oft-overlooked dignity. Here, it was delivered in the form of kikoy wraps and throws wrapped around the shoulders. “Look” said a blue crocodile on one. The designer pointed at the mutual fetishizing of foreign dress, and some would only look at the proffered necklaces.

Using this inane word, “reflection”, allows this writer to remove responsibility and accountability from Vampire Weekend vocalist Ezra Koenig and Japanese designer Watanabe. They get to travel physically and metaphorically through former colonial landscapes – and cherry-pick the pretty bits that others made. As Koenig said of his own efforts, he got to “think” about “aesthetic connections between preppy culture and the native cultures of places like Africa and India” (never mind that these are vast continental masses with innumberable “native cultures” which were neither as static nor as “native” as appropriation specialists want such people or their cultural products to be). This sort of “thinking” allows one to be a tourist of the colonial imaginary – and not present (historical or contemporary) reality; they don’t have to engage critically with what such symbolic appropriations have done to objectify the “native” as something to be subjugated, marginalised, and erased through genocide.

Watanabe, like many before him, has plunked some “native” goods on some white people. Those goods, once removed of power and history, are now safe being used as an homage, as long as the black people have been disappeared from the stage.

Also: anyone wanting to add that some Japanese, called B-Stylers, admiringly wear blackface, should read Nina Cornyetz’s “Fetishized Blackness: Hip Hop and Racial Desire in Contemporary Japan” in Social Text (1994).

No country for widows

Massacres happen fast and slow. Ask the survivors and their survivors. Last week, Jacob Zuma finally shared his version of the Marikana Commission of Inquiry, aka the Farlam Commission after its chairperson, which has, after a fashion, investigated the August 16, 20102 massacre of striking mineworkers at the Lonmin platinum mine in the North West. There were little to no surprises in Zuma’s presentation, which emphasized those points that were meant to absolve the President and his friends.

The only surprise, if it was a surprise at all, was the lengths to which the State went to demean and diminish the miners, dead and living, and their loved ones. The nation was given five hours’ notice, and then the President went on. The widows weren’t given prior notice nor were the surviving mineworkers nor their attorneys or supporters. They found out the about the event as they returned from work, ran about looking for a tv, and finally found a laptop, in a Longmin board room, only to have the feed not function. Some say it was load shedding.

But why were the widows treated in this way? Surely it couldn’t have been too difficult to have given them prior notice? More to the point, surely they should have been sitting in the gallery, right there. Surely South Africa has the wherewithal to bring a few grieving women from the North West to hear the President deliver his understanding of the meaning of their husbands’ deaths?

Betty Gadlela, widow of Sitelega Meric Gadlela, now works as a miner to support her family, commented, “Our husbands died like dogs for R12 500 which is nothing considering the amount of work that is done in the mines. Our eyes are still filled with tears and we still mourn the deaths of our husbands. Now that I also work in the mine, I see why our husbands went on strike.”

Noluvuyo Noki, widow of strike leader Mgcineni Noki, `the man in the green blanket’, added, “The police who killed my husband are given the opportunity to work and take care of their children. What about my daughter? What about the children of the other miners who were orphaned because of that shooting?”

From the day of the killing, and actually before, the women of Marikana, incandescent with rage, pushed, organized, protested, organized, refused to stay in the dark. Some sat for two years at the Farlam Commission hearings. As one widow explained, she left her children for two years, hoping for a definitive answer of what happened to their father. They sat through almost three years now of empty commemorations without any discussion of compensation. The President also “forgot” to mention compensation in his rendering of events.

And now?

Ntombizolile Mosebetsane, widow of Thabiso Mosebetsane, sighs, “What do you want me to say? I have no words. There are no words… The report says nothing about who killed my husband or why the police believed that any of them should have died. Would it be too much to ask Zuma to come to us personally, as the president of this country, to address us? Because this cannot be the final chapter of our people’s lives.”

And now the widows go back to court, and for them, the struggle, and the massacre, continue. This cannot be the final chapter of our people’s lives.

Durban Pride 2015: What Does Democracy Feel Like?

Taking the microphone at Durban Pride, Foundation for Human Rights LGBTI Coordinator Virginia Magwaza shouted a question to the two hundred or so participants who had initially gathered at the Snell Parade Amphitheatre on the city’s North Beach:

“What does democracy feel like?”

“This is what democracy feels like!” The crowd shouted back in excitement.

So what was the feeling of being at Durban Pride?

Durban’s 2015 Pride march took place on a grey, drizzly afternoon on Saturday, June 27th. The area immediately surrounding the Sunken Gardens and Amphitheatre in Durban’s North Beach area was fenced off, primarily due to the sale of alcohol at the event. The event, only in its fifth year despite Durban’s presence as South Africa’s third largest city, was initially sparsely attended, although attendance later swelled to about 2,500 by the end of the afternoon. Durban’s event offered a marked contrast to many other pride events—the attendance was relatively small, and the event was markedly free of commercial branding and sponsorship. Entrance to the area was free and sale of kitschy gay paraphilia was at a minimum — indeed, the Amphitheatre offered far less rainbow imagery than any American’s Facebook feed 24 hours after the SCOTUS decision to allow gay marriages. Most of the affiliated stalls skirting the Amphitheatre were service-oriented, indicating the event’s primary relationship with the Durban Lesbian and Gay Community and Health Centre. Participants could receive free HIV testing, learn about LGBT organizations, or pick up copies of the constitution and lists of their rights.

Durban Pride 2015 didn’t fit neatly into many of the pre-existing narratives about pride celebrations. The event was not a large commercial and apolitical presence offering simply a large party space, nor could it be easily classified as solely a local grassroots queer movement, like those seen in the alternate responses in Cape Town and Joburg. Durban stubbornly resisted either category. The attendees were a wide mix of racial, gender, and age groups. Yet the event was also deeply structured by local histories and sensibilities. Participants frequently broke out into struggle-era songs; marchers frequently shouted “Amandla! Awethu!”

Durban Pride 2015 felt simultaneously local and diffuse, not an unfamiliar feeling in a city of over 3 million host to both incredible diversity and recent outbreaks of xenophobic violence.

The pre-march speeches returned repeatedly to the continued reality of hate crimes and social violence as the most salient reason to continue Pride parades. Organizer Nonhlanhla Mkhize took the microphone to bluntly ask local ward councilors and government representatives, “Tell me, what are you all doing to make eThekwini [the isiZulu name for Durban] safe for moffies?” Government officials offered speeches aimed at protecting queer members of the community. Perhaps most indicative of the multiple directions of the event, the final speaker was Craig Maggs, Mr. Gay South Africa, a hunky, muscular white man who flashed his abs and offered a moment of simultaneous consciousness raising and pinkwashing. The KZN-born Maggs called on the crowd to take on the responsibility for making South Africa a better place for LGBTI people while simultaneously admonishing them to appreciate their freedom, something unavailable in nearby places like Zimbabwe. Good-natured hectoring aside, the invocation of Zimbabwe as a negative comparative space invoked some of the tensions of the year’s earlier violence. After a final call to celebrate, we began the six kilometer march along the Durban beach and back to the Amphitheatre space without incident.

As the post-march event shifted into high gear with drag performances, dance-offs, and community appeals, Virginia Magwaza’s words rang in our ears. What did democracy feel like? Was Durban Pride a space where democracy was being lived, debated, and understood? How did it all fit together? The clearest place to begin seemed to be with Durban Pride’s organizing theme, “On Common Ground.” Asking participants how they understood the theme offered both a way to gauge people’s feelings about the event and the larger purpose of Prides in general.

Amongst the organizers, Director and Advocacy officer at the Durban Lesbian and Gay Community and Health Centre Nonhlanhla Mkhize explained that the theme signified not only a sense a unit, but a continued commitment to work together beyond the day’s events. She stressed that “on common ground” provided a way to think about continued interlinked struggles for justice throughout the year, implicitly linking struggles against xenophobia to those against homophobia in Durban.

Jason Fiddler, an organizer and Director of the Durban Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, argued that ‘On Common Ground’ worked as a theme because it allowed people to fill in “whatever they wanted afterwards,” creating a place where people take the theme and craft their own significant and individual meaning for the event. This is almost exactly what happened. The expansiveness of the theme allowed people to simultaneously individualize their concerns while thinking about a collective movement in Durban here and now.

While many Pride participants we talked to were not aware of the theme or did not have any particular interpretation, several participants did share specific thoughts on the theme.

“I’m going to look at it from myself and my profession,” offered one participant. “Black, African, lesbian, born and bred in one of the roughest townships in Durban where hate crime is a common occurrence. [But I work for the police so] I feel like, I’m safe. From the ground a policeman, I feel safe. I wish that everybody there — I wish I would share that common ground with them. I wish that they would feel as safe as I do. I am very lucky. I do have a decent enough job. I do live in a safe neighborhood. I wish I shared that common ground with a lot of the queer people who are at this event today.”

This response offered a particularly keen observation of the contradictions within South Africa’s two decades of neoliberal democracy. Recognizing the uneven transformation of the post-1994 world under an ANC-led government, this participant saw a ‘common ground’ as a space that mediated between those who had access to resources and protection, and those that didn’t. She saw herself as embodying these very contradictions, having moved from her place of origin (while marked by histories of race, class, gender, and sexuality) to her “good job” in a “good neighborhood.” The ‘common ground’ she saw offered a potential to link people across material divides within a ‘New South Africa’ that has inconsistently raised people’s standards of living.

These views were not universal. As one white female participant explained, “I think what has been missing from Gay Pride Durban is the fact that — everything is so theme oriented with political issues that we’ve missed the whole thing, which is that we are all on common ground. [But] what I’ve found this year, everybody is just mingling and having fun and being happy and being out, loud, and proud because there are no issues, there is nothing that defines us except our sexuality. That’s it.”

This view saw Pride as an apolitical gathering, a “happy” gathering with “no issues… except our sexuality,” a strong claim in a city that so recently experienced xenophobic violence and has continued histories of unemployment and gender-based violence. Such a claim reveals the tensions in organizing Pride in Durban — should this be simply about celebrating LGBTI sexuality, or should this connect to other, inter-related social and political issues?

By contrast, another white female participant couched her interpretation of the theme in recent political events in South Africa. She shared, “It means a lot things actually, considering the recent xenophobic violence that we experienced. So I think for me the theme speaks about that or about kind of tolerance versus hatred, generally. Maybe it was because one of the ‘say no to xenophobia’ slogans was similar, like African unity — we are all here together. To me it relates LGBT struggles of rights to other foreign nationals in South Africa, gender rights, those kinds of things.”

For this particular observer, ‘on common ground’ did several things at once. It not only linked to politics of shared sexuality and organizing, but it also revolved around larger questions of inclusion. The ‘ground’ itself can refer to the highly contested ground of a (post)colonial state, where apartheid histories linger on in de facto segregated spaces, and where xenophobic violence polices who gets to claim to belong on the common grounds of eThekwini, of South Africa, of the larger continent.

As we walked around the wind-swept beach, watching all manner of people dancing to the pulsating rhythms emanating from the Pride stage, we asked once again, what does democracy feel like?

Democracy feels… strange. It feels like a constant tension between individualism and social consciousness. It feels like increased LGBTI visibility and increased backlash. It feels like one of the many facets of a daily life impacted by gender, race, class, and the many challenges of history. It feels complex and incomplete, where the common ground shifts and tilts beneath you on a windy winter afternoon.

June 26, 2015

Cameras and the Indian Ocean

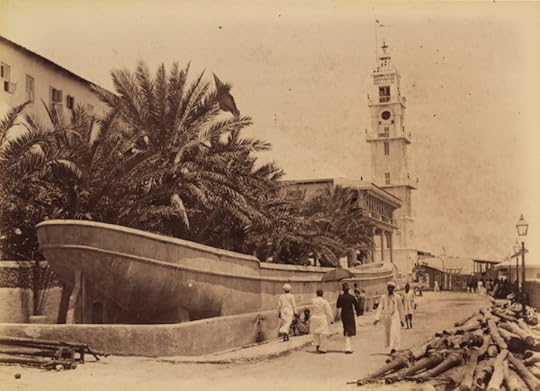

In 1883, the Sultan of Zanzibar, Barghash bin Said, commissioned a camera obscura room in the tower of his new palace, the House of Wonders. Royal family members were early enthusiasts and collectors of photographs, part of a fervor that swept the Indian Ocean’s urban enclaves.

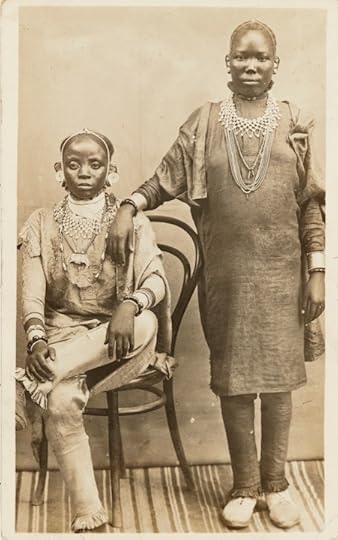

It may be surprising to realize how quickly photography became an indispensible form of expression in East Africa. Today we have new access to these earliest images ranging from Zanzibar’s royal wives and concubines to poor, newly-freed people from Indian Ocean islands at the dawn of abolition. Sailors and Daughters: Early Photography and the Indian Ocean, an online exhibition sponsored by the Smithsonian, highlights these photographs from east Africa and beyond. Most are on view for the first time ever. With these, we have access to a wider array of the “citizenry of photography” (Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography).

Sevruguin, Antoin,; b&w ; 18 cm. x 17.9 cm.; Myron Bement Smith Collection: Antoin Sevruguin Photographs. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. Gift of Katherine Dennis Smith, 1973-1985

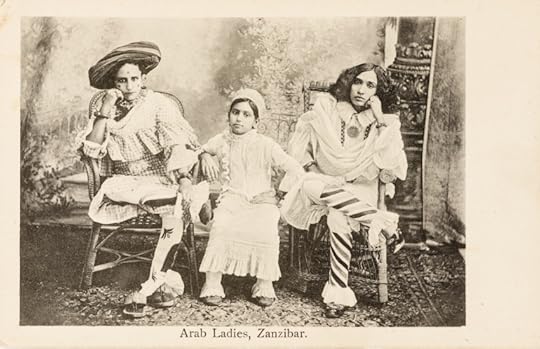

Today, many of us are unaccustomed to seeing photographic portraits that are starkly gorgeous. A portrait of three royal women, their names unknown, offers a glimpse of the vast dimensions of style brought together and melded in Zanzibar’s royal harems. Here, we can see sartorial influences brought by the women who would become the Sultan’s wives and concubines; they layered elegant styles – from India, Oman and the Gulf, Circassia (present-day Georgia), Ethiopia, and as far as Zambia – into Zanzibari courtly attire.

Photographers like A.C. Gomes, Coutinho Brothers, and Pereira de Lord, themselves the sons of myriad diasporas, created portraits befitting their subjects. One commenter tied the extravagance evident in these portraits to a long-standing pride in fashion and beauty: “Swahili women have always been so fashion forward, and we take pride in looking good,” noted ‘bantujustmeanshuman’ (qtd. by streetetiquette and psaltftheblog).

Fashion is all about creation, and accelerating the new; if looking good is an aesthetic assertion, fashion cannot be disentangled from the political ambient. For instance, in 1890s Zanzibar, portraits of women in kangas and heads covered in showy kilemba heralded abolition. Recently slaves, women could now dress as those who were free-born. Moreover, the act of walking through city streets, and into photo studios, marked a revolutionary freedom. It also marked a huge shift from the private to the public: Muslim women were forging a new visual economy of cosmopolitan style.

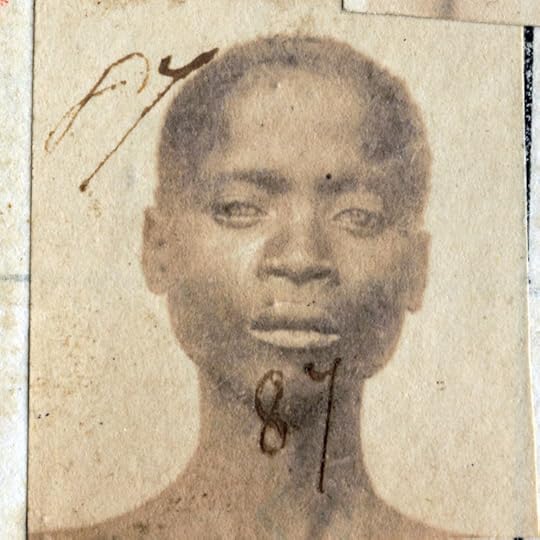

The exhibition also shares new visions of slavery and diaspora, subjects that are especially complex. These include portraits of people who were captured, then ‘freed’, only to be transported to again to become indentured servants. These are valuable records of individuals, revealing, through their portraits, something of what it meant to exist under harsh conditions; though they were taken for bureaucratic purposes—as a way of maintaining records of the indentured—and though they were not a means of “self-fashioning”, as were the photographs of wealthy Zanzibari women, these photographs nevertheless defy and alter our expectations of what precisely constitutes a photographic portrait. It makes us question the ways in which photography has offered a means of creating versions of, and fictions of, selfhood and portrayal.

Gandor, 18 years old, son of Aoliath. Liberated at Port Victoria on the 7 October 1871 (H.M. Ship Columbine). Registered under no. 87 on the 13 October 1871. Assigned to V. Morin Photographer unknown Albumen print Port Victoria, Seychelles 1871

Other aspects of the exhibition explore the conditions of travel and migration. These include among the earliest daguerreotypes ever taken in east Africa (Guillain’s Atlas), Sevruguin’s lush portraits of African advisors at the Persian court of Nasir Al-Din Shah, and diaspora communities in the port city of Muscat, Oman.

Underlying this exhibition is an idea familiar to most readers here: globalism is nothing new. For centuries, the Indian Ocean tied together a web of distant cities–Zanzibar, Mombasa, Mogadishu, Mauritius, and Muscat among the many metropoles navigated upon monsoon’s seasonal winds. In the long durée of exchange, photography’s global histories fundamentally undermine our outmoded understandings of what ‘modern’ means: these photographers took up new technologies, making use of those practices deemed relevant and useful, and aesthetically domesticated the camera and its contents.

Postcard Zanzibar, c. 1890 TZ 20-25. Photographer unknown . Courtesy the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Since the exhibition is an exclusively online affair, you don’t have to make the trek to the Smithsonian to see these extraordinary photographs. Physically bringing together early photograph collections and albums from across the globe wasn’t possible, but the fragility of these materials posed one advantage. If you’ve ever had the pleasure of admiring an albumen print with a magnifying loup, you’ll see how well these photographs are served by a digital platform. The vivid beauty of these prints demands we zoom in with a leisurely eye, take a rare and considered look.

How do we best share and learn about these kinds of images and histories? These are the stakes in moving these photos out of the hyper-secure archives and rarely-seen collections in Chicago, Berlin, Johannesburg, Washington, D.C., the Seychelles, and Réunion. At a time when there is ever more digitization of image archives, we very rarely see these efforts increasing access to global publics.

Boat-Cistern, built alongside of the Beit al-Sahel, in Zanzibar Stone Town Water Trough in Shape of Boat / Lighthouse in Background Photographer unknown Albumen print Zanzibar, c. 1880-1900 73-23 Courtesy the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies Winterton Collection, Northwestern University

Another great advantage of this on-line platform has been the real-time response by those who may never set foot in the U.S. The intensity of online activity—commentary, writing, sharing—around this exhibition leaves the experience of looking at photographs in a museum gallery seem comparatively remote, rushed, fragmentary.

Instead of remaining in faraway museum archives and galleries, these photographs were shared and posted widely. Online audiences from Addis Ababa, Muscat, Secunderabad and Austin were quick to bandit these photos. The images multiplied online, shared and forwarded towards countless unanticipated aesthetic and intellectual projects. The chic women from Zanzibar scroll now next to streams of street photography, creative and political discussions, family pages, theoretical and feminist and fashion sites. Etched in silver and light, these photographs are going places.

Sailors and Daughters: Early Photography and the Indian Ocean is an online exhibition curated by Erin Haney, assisted by Xavier Courouble. It is part of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art’s Connecting the Gems of the Indian Ocean: From Oman to East Africa project, supported by the Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center in Washington, DC.

With thanks to Carolyn Hamilton, Verne Harris, Dabney Hailey, Wendy Grossman, and Wilcox Design/Green Interactive.

South-to-South perceptions: African films in Colombian cinemas

In Colombia, African heritage is celebrated in May. And, to commemorate the celebration this year, a group of Colombian journalists, filmmakers and cultural activists who form a collective known as SUR organized MUICA (Muestra Itinerante de Cine Africano), an African Film Showcase.

For their first time in South America (they organized a festival in South Africa last year showing Colombian films), MUICA went to three major cities of Colombia: the capital, Bogotá, and also Cali and Cartagena, two cities with a larger percentage of Afro-Colombian population.

MUICA brought a selection of thirteen award-winning films, varying from documentary and animation to social drama and science fiction. Those were films that highlighted the stories, landscapes and portraits of several African countries that left the Colombian audience feeling quite mesmerized by the socially conscious films and their distinct beauty.

The opening film, Tango Negro, the African Roots of Tango, touched the sensitive subject of African diaspora in Argentina to unwind history and reveal a surprising twist. Directed by Angolan filmmaker Dom Pedro, the documentary discusses the historical backdrop that shaped the evolution of tango, and it highlights the controversy in the origins of the musical genre in Argentina and Uruguay.

The movie calls the attention to think that in the Kikongo language, the name “tango” means sun, but it may also refer to time and space. Like a vibrating sun that has long misplaced its origins and traded its credibility for ignorance and racism, tango is but one of many features taken over by a socio political eclipse that shaded our view of the past and kept us from hearing the story of our very own roots.

Opening the showcase with this documentary was very reassuring, and it gave the audience an idea of the kind of films they could expect from MUICA.

Some other highlights were Mama Goema: The Cape Town Beat in Five Movements, a documentary that follows the trajectory of music in Cape Town, from those traditional sounds that make you dance, to other musicians that provide new and bold interpretations, like Mac McKenzie, musical founder of the Genuines and the Goema Captains of Cape Town.

The documentary had a Q&A with Colombian filmmaker and SUR member Ángela Ramírez, who engaged a young audience in the city of Cali in a dialogue that touched subjects such as social and political transformations and other parallels that could be drawn between South Africa and Colombia. In particular, music, cultural heritage and the reconciliation processes, which seem to be so necessary for the population and the spirit of both nations.

Films like the beautifully styled animation Aya de Yopougon, and the film that gave closure to the showcase, Soul Boy, were more lighthearted and uplifting films, also favored by the audience.

Soul Boy was directed by Hawa Essuman under the mentorship of German director Tom Tykwer who conducted a workshop for young-emerging talents in Nairobi, Kenya.

The film was set in the slum of Kibera in Nairobi with a coming of age story enhanced by amazing synergy between characters and impeccable cinematography. Soul Boy was a very fitting film for the objectives of SUR Collective, interested in undertaking other similar initiatives with future editions of MUICA by partnering with universities, not only to screen the films, but also to offer panels that make this kind of projects visible and accessible to students and faculties in Colombia.

This year, a few films were screened in more disadvantaged sectors of the three cities, an important goal that seeks to differentiate MUICA from other festivals where projects like the one Tykwer and Essuman worked on can be highly valued.

Undoubtedly, there is still a lot more to look forward to, but the first MUICA showcase was an excellent opportunity to strengthen our knowledge and review our cultural and historical relationships. Perhaps in the future, we will begin to see a product of this exchange, and foster new filmmaking tendencies that go hand in hand with our south-to-south visions of each other.

June 25, 2015

Loit Sols & Churchil Naude, live from Coffebeans Routes in Cape Town!

Here it is, your live stream of “If you can’t see me, are you really there?” concert series from Coffeebeans Routes headquarters in Cape Town. Select the audio or video stream below to join the festivities:

LIVE VIDEO STREAMING by Ustream

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers