Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 338

June 25, 2015

Hipsters Don’t Dance Top World Carnival Tunes for June 2015

Hipsters Don’t Dance is back with their June chart of tunes from around the Carnival diaspora. Enjoy this edition and remember, as always, to visit the HDD blog for all their great up-to-the-time-ness out of London!

Davido x Fans Mi (Feat. Meek Mill)

Have you ever seen Meek Mill this happy? Him and Davido serve up an Afropop road rap jam that doesn’t stray too far from either of their talents. Congrats to Davido on graduating from University, as well.

Silvastone x Skatta (Remix Feat. Chaka Demus)

Remix kid Seani B, explains in this video how the remix came about. This means that almost everyone in dancehall, apart from Shaggy and Shabba, has collaborated with an Afropop artist. It’s pretty impressive, probably the reason why VP (legendary record label) now has a base in Nigeria.

Sarkodie x New Guy (Feat. Ace Hood)

We still aren’t the biggest fans of Ace Hood round these parts but Sarkodie is one of the best rappers on the planet, so here we go. Interesting how we got two African artist collabs with street rappers in the same month.

Mista Silva x Goes Down

We can’t help but hear early Burna Boy when we hear this, but that’s not a bad thing. Interestingly, the video for the dance instructions has over half a million views, which in our opinion shows that dance culture is as strong as ever.

Magic System x Enjaillés

Possibly the most visible and durable Afropop artists of all time, Magic System are back with a disco infused jam about never wanting to stop dancing. It’s pure pop and sounds like something they would have cooked up with Bob Sinclair.

Issa Hayatou: Most Valuable Player?

Every so often efforts are made to justify the world’s obsession with football by casting it as an engine for social development. Football is touted as having the potential to break down barriers between Palestinians and Israelis (Sepp Blatter boasted along these lines last month), football will improve health, reign in street children, pacify gangs and so on. To that list one can now add: football may have been the venue for a revival of sorts for the Afro-Asian political alliance.

Many who usually watch only the highlights of African and World Cup finals became dedicated spectators of the off-pitch competition for the leadership of FIFA this May. There is nothing like a good political drama.. American Attorney General Loretta Lynch explained the basis for US intervention: the crimes were plotted and the proceeds laundered in the USA. In other words, universal jurisdiction. The very principle on which observers hoped for the apprehension of the war criminals responsible for using American tax-dollars to level Gaza in 2008/9 and again in the summer of 2014.. The chief perpetrator, Benjamin Netanyahu has since been allowed to address Congress and no attempts were made to arrest him. The USA does not tolerate bribery and racketeering, but it will cut you a lot of slack for the killing of thousands of people under occupation. It’s also clear that the US DoJ is much more serious when tackling criminality by football administrators (who have no powerful lobby in the US) than they are in bringing corrupt banks and their employees to book. No dawn raids on Wall St, still.

British prime minister David Cameron, his Foreign Secretary, and the chairman of the English Football Association, as well as Michel Platini, president of Europe’s regional confederation, UEFA, all urged Blatter to step down (though Platini’s home nation, France, voted to re-elect Blatter).

The response from the African, Asian, Caribbean and Central American Federations was to give their full support to Blatter. At the Confederation of African Football congress in April, wearing a theatrically indignant expression, President Issa Hayatou delivered a statement calculated to lower the morale of the European bloc: “[Blatter’s] action in favour of Africa speaks for him. To us, he is still the man of the moment.”

Those actions included promoting competitive football in Africa by funding the building of infrastructure including training centres, accommodation, pitches and offices, and widening the field of World Cup competitors to include more Asian and African representatives. Staging the World Cup on those Continents, particularly at the junior levels, established his credentials as ‘the man of the moment.’ Sepp Blatter’s profile is almost irredeemable in the eyes of many at this point, yet he can claim credit for being a colour-blind visionary.

The sheer weight of the deployment against Blatter’s regime is most intriguing and reminds me, in some ways, of the struggle in 1960–61 between the Afro-Asian Bloc and the European and American allies over the future of newly independent Congo. The Afro-Asian Bloc then, as now, looked to its own interests which had been arbitrarily subordinated to Western interests. Then as now the United States sought to occupy the moral high ground and took on the role of guardian of the Free World. Like Congo’s mineral wealth before it, international football is just another lucrative commercial interest. (Belgium exported minerals and other products worth US$450 million per year from Congo in the late 1950s.) The single-mindedness of the West in pursuing its interests is always fascinating. Once Congo was deemed to be vulnerable to Communist infiltration in 1960, the Department of State together with the CIA set about closing the loopholes by all means necessary, not balking at conspiring to depose the first elected Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba. Their methods included bribing parliamentarians as has now been revealed by newly declassified memoranda between the CIA’s Congolese Station and Washington headquarters:

Launch extensive [less than 1 line not declassified] campaign ([less than 1 line not declassified] meetings) by assisting local political groups with the funds and guidance to take anti Commie line and oppose Lumumba.

C. Expand political action operations seeking out and recruiting additional political leaders with view to influencing opposition activities…organize efforts to mount a no confidence vote in one or both houses of parliament. ….Immediate goal would be replace present govt with more moderate coalition headed by [Identity 1]. He appears be only opposition leader with hope of rallying opposition groups.” Document 8. Telegram From the Station in the Congo to the Central Intelligence Agency, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968 Volume XXIII, Congo, 1960–1968.

New to Western parliamentary/voting methods, Congolese parliamentarians were at first dormant. The CIA then identified specific individuals to be ‘developed’:

As [Government of Congo] leaders have done little to convince fence sitters to support the GOC despite our continuing efforts to influence these leaders[…] our Chief of Station has been attempting to stimulate action by preparing a listing of probable voting positions as well as a listing of parliamentarians who should be developed. This listing has been passed to GOC leaders who are now stirred into action. To support their efforts a total of [number not declassified] francs has been passed to influence key deputies.” Document 87. Paper Prepared in the Central Intelligence Agency, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968 Volume XXIII, Congo, 1960–1968.

Despite their best efforts, the vote of no confidence fell through. So Lumumba was bundled on to the back of a pick-up truck, trussed and shot dead instead. Then plans were put in place to tackle the troublesome alliance:

The key problem now is that we are losing the support of Afro-Asians….Since we can no longer build on the Congolese, we must have the support of the Afro-Asians. If we can not rely on the Afro-Asians we must either try to split the Afro-Asians or resort to the Belgians. Document 11, Memorandum of Conversation, January 26, 1961 FRUS, 1961–1963 Volume XX, Congo.

But what does all this have to do with FIFA? Surely in the context of the present crisis, neither Hayatou nor Blatter bear comparison with Lumumba.

FIFA too faces the threat of dismantling if it cannot be made compliant. UEFA has warned its members are prepared to consider re-segregating international football by pulling out of FIFA and the World Cup. This would have the effect of isolating non-UEFA members in much the same way as Guinea was held at arm’s length by France and America when that country declined to join the French West African Community after independence, an option that would have maintained the French President as Guinea’s Head of State.

After Blatter’s eventual capitulation it is becoming apparent the playing field is still tilted, just as it was in the 1960s, with talk of African countries having their voting-power reduced. This in the face of a tranche of scandals involving predominantly non-African football administrators giving and receiving bribes.

Judging by his age (68) Hayatou must have gone to school in the days when you did precisely what any European (teacher or fellow pupil) instructed you to do, resulting in more than one generation of Africans with what Houphouët-Boigny and later Stephen Biko called the African inferiority complex. Hayatou, from his vulnerable position as a suspect in FIFA’s racketeering was able to rise above this, stare them down and together with the Asian Federation, vote in the interests of African and Asian football – and his own interests. The same defiance that fuelled Nationalism in its heydey also powers the current crop of leaders of puppet states and institutions such as CAF and plays well to a gallery nostalgic for the idealism of the 50s and 60s.

To be fair, he has delivered, more than doubling the African slots in the World Cup (from 2 to 5) and raising the number of African countries participating in the Cup of Nations from 8 to 16. It’s impossible to say that a cleaner FIFA would have delivered more.

Hayatou read the game accurately, as an administrator since 1973, (CAF president since 1988) including stints at a college and as a director in the Ministry of Sports of Cameroun, he knows what bad governance looks like and that FIFA has been badly governed. If allegations against him are true, he will have become to FIFA what Mobutu was to the USA, a fixer. Their dogged support of the sinking Blatter can only mean that he and other Afro-Asian bloc football administrators are unembarrassed by FIFA’s venal sins, nor blind to Western ulterior motives. It is the game and, like Mobutu, Hayatou is very good at it. However, despite a spirited campaign, the Bloc lost the match for one reason: they failed to discern that operating skills on their own are insufficient; your jersey needs to at least appear to be clean as well.

Morally, the opposing sides are balanced. Following rolling revelations such as the sub-prime mortgages saga, LIBOR and forex rate fixing in the USA and Europe, it has become clear that bribery and racketeering are still as widespread and endemic in the staid, elite institutions there as elsewhere. Iraq was invaded on false pretexts; WMDs, Communism, corruption, any cover will do where elite Western interests are at stake. Compared to the capture and underdevelopment of entire countries such as 1960s Congo and today’s Palestine, football administration and Blatter’s inadequate management of it is hardly an issue. The bigger question is whether 60 years after the Bandung Conference national Afro-Asian leaders will learn from it and act in unison on matters affecting their interests and those of oppressed countries everywhere, beginning with the Occupation of Palestine. Or are consensus and action only possible when the issues revolve around football?

June 24, 2015

Osekre’s ‘Afropolitan presents’ spoken word poet Taylor Steele

In the lead up to his summer event series in New York, Osekre ran down his experience as a struggling musician in the city that never sleeps. ‘Afropolitan presents’ will take place again at Meridian23 this Friday, June 26th in New York. For it, we are featuring a post from another one of the participating artists, this time by spoken word artist Taylor Steele.

It was an unconditional, at-first-sight, head-first-dive kind of love I found myself in at 17. I had never met anything that made me feel so vulnerable and invincible at the same time, not until spoken word poetry. Perhaps this is an anti-climactic reveal, but for me that discovery was explosive.

I’ve always been a writer. The earliest memory I have of a poem I wrote dates back to 1995 or so, and the piece mentioned flowers and chocolate. I must have been precociously romantic at 4 years old. But I had never spoken my words aloud. Had never even really considered the possibility.

When my friend showed me videos of poets she knew performing at such infamous places as the Nuyorican Poets Cafe and the Bowery Poetry Club, I felt something awaken or open inside of me. Like, oh, hello door to a room I didn’t know existed! I remember going home after school that day and watching video after video after video, hands covered in ink trying to nail the perfect string of words into the perfect “slam” cadence. Nothing good was borne that night. I was trying too hard to sound like someone I wasn’t. And it hit me later, that the whole point of spoken word, of poetry, of any art medium at all, is being yourself. So, I turned the computer off, stopped listening to other people’s voices and started hearing my own. And out came this poem. My first real spoken word piece. I read it over and over to myself. But never to anyone else. This was my baby. And I couldn’t handle anyone telling me it was ugly. I held onto that poem for about a year.

The first time I had courage enough to perform it, I was in a room of 100 strangers, an experience that might terrify most. It was the last night of a week-long orientation for freshmen students of color. Though I had resolved to cure myself of my shyness by the time I started college, I had spoken to maybe 6 people that entire time. But, when I hit the makeshift stage that night, I felt so at home in my nerves, and in being seen and heard — a thing I had not known in my, then, 18 years.

Writing had always been such a quiet experience for me. I wasn’t just a shy person; I was introverted and living with several undiagnosed mental disorders. Survival at that time meant keeping everything to myself. This was the first time I was ever letting people into my lived experience. Granted that poem was about unrequited love, but it was a stepping stone.

So many people approached me after, telling me how talented I was and how what I wrote spoke to them and helped them to heal. That was another thing I had never considered. My art, up until that point, had really only ever been for me. I wrote to cope with my depression, anxiety and loneliness, to better understand what I was thinking and feeling. I had never considered that something I created could help someone else. After that, I joined my college’s first ever slam team, competed on a national stage, and gained more than confidence. I was truly learning who I was. Through writing and sharing.

And now, that’s all I want to do. I believe in the power of art to change, shape, and heal. I am so lucky to have found such a diverse, political, powerfully vulnerable community. I found a “safe space.” I get to be Black out-loud. I get to be hurting out-loud. I get to heal out-loud. It’s the one space I’ve found I don’t have to be afraid of everything that I am. Basically, finding my spoken word community was like getting my letters to Hogwarts, and we all get to make magic together.

Check out Taylor and a host of other exciting artists at Afropolitan presents, including fellow poet Jumoke Bolanle Adeyanju (read a great interview with her here) and our own Chief Boima, this Friday at Meridian23!

Takun J stirs the Liberian streets with calls for justice and accountability

Takun J, currently the most popular musician in Liberia, bounds on to the stage at his downtown Monrovia nightspot, 146, on a recent Friday night. Brimming with energy and sporting camouflage pants and a matching green hoodie and bandana, he announces, “Since I dropped ‘They Lie to Us’, I’m not secure… It’s very deep, it’s getting personal. But to my fans and friends who are here tonight, I want to tell you I am not deterred.”

Emerging on the Liberian music scene a decade ago, Takun (Jonathan Koffa) has become known as the ‘Hip Co King’ (Hip co is Liberia’s leading urban music which blends hip hop with Liberian English). After being targeted early in his career by the authorities following the release of ‘Police Man’, a track that explored corrupt law enforcement officials, the government began to recognize the power of Takun’s music. In 2013, following substantial local buzz created by work with New York based edutainment non-profit PCI Media Impact, he was named the Government of Liberia’s and in the months prior to the escalation of the Ebola crisis, he was touring the country as a UNICEF spokesperson for a children’s protection campaign.

However, the concurrent release of two new songs, ‘They Lie to Us’ and ‘Justice’, has set Liberia’s proverbial political pot onto a full boil. The songs are two of Liberia’s hottest tracks of the moment and can be heard on motorcycles buzzing along Monrovia’s busy streets or pumping up the audience and athletes at kickball and soccer tournaments.

‘They Lie to Us’ [a song we featured on this site while the Ebola crisis was in full swing in Monrovia] unabashedly assails the government, noting that ‘you screw us, you use us, and later on abuse us’ while ‘Justice’ speaks to Liberia’s legacy of impunity for prominent officials. It contains an oblique reference to an incident in which Takun was assaulted by Representative Edwin Snowe, a son-in-law of former Liberian President and warlord Charles Taylor, and a lawmaker who briefly served as Speaker of the House in the early years of President Sirleaf’s government.

The songs have spurned Monrovia’s rumor mill: citizens, distrustful of their government after a century of one party rule followed by more than a decade of civil war (enabling and contributing factors for which the new tracks touch upon), are under the impression that Takun has been arrested and imprisoned for daring to speak bluntly (at the time of writing he remains free). Takun notes that strangers, with possible links to the authorities, have begun to stop into 146, uttering threats and closely watching his movements. He, and those close to him, have received threatening phone calls noting that the government will frame and arrest him.

While the government of Liberia’s Nobel Peace Prize winning President, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, has made some notable missteps, there remains a strong commitment, at least on paper, to transparency and freedom of expression. Liberia is one of the few African nations to join the Open Government Partnership and recently passed West Africa’s first freedom of information legislation. However, the domestic political situation is fast-changing. The United Nations Mission in Liberia may depart in June 2016 and a host of political actors have begun to jockey for the spoils of the 2017 elections, at which time President Sirleaf will reach the end of her constitutional mandate.

In recent years, West Africa has seen change driven by music as part of important social movements such as Y’en A Marre in Senegal and Balai Citoyen in Burkina Faso. With music channeling popular sentiments, these efforts have pushed for democratic reforms. In other African countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, these and other musicians who have questioned the status quo have been arrested. Liberia may be at a turning point at which the efforts of musicians like Takun J can have a real impact on the future trajectory of the country through mobilizing citizens behind core grievances. Will the Liberian government listen to their voices, or use its power to turn down the volume?

Stream Takun J’s music on his Soundcloud page, and download “Justice” below:

June 23, 2015

Stream Africa is a Country’s live concert partnership with Coffebeans Routes, this Thursday

As we announced earlier this month, Africa is a Country is teaming up with Coffeebeans Routes in Cape Town to bring you a live concert series called “If you can’t see me, are you really there?”

The first edition will happen this Thursday at 19:30 Cape Town time. Visit the site at that time (use the previous link to calculate your own time) to participate live, and read up on the first act below!

FIRST CONCERT – LOIT SOLS & CHURCHIL NAUDE

The Coffeebeans Routes concert series “If you Can’t See Me, Are You Really There?” opens on Thursday the 25th of June with a goema rymklets folk hip hop collaboration between acclaimed published poet and performer Loit Sols, and Afrikaans hip hop artist Churchil Naude aka Kroeskop, Koos Kombuis’s favourite rapper. This is their first live collaboration. The show comes on the tails of Churchil’s debut album release, Kroeskop vol Geraas, and their studio collaboration on the Wasgoedlyn project.

Goema is what connects Loit and Churchil. Goema, the geographically distinct, historically unique, rhythmically inflected, culturally outerclass, irreverent, scatological and deeply spiritual indigenous masala.

Brandishing a Khoekhoegowab language dictionary, Loit points to the Khoesan etymology of Goema: “Goma”, meaning the hide of an ox. The drum, says Loit, is not a drum without the stretched hide. Goema is also derived from the Indonesian “Gumum” meaning murmur, indicative of the drumbeat of dissent among the Cape’s West Indies slave ancestors. Drum. Bush Telegraph. Language. Goema – sameness and difference. Visible and invisible.

Loit is a poet, musician, graphic designer, performance artist, Goema lexicologist, and now also radio presenter – he has just started a weekly slot on Radio Sonder Grense, RSG, on Friday mornings 0745 – 0800. Born in Retreat in 1957, he started writing at age 8, and taught himself music starting at age 21 with a guitar. He has performed variously, locally and internationally, including the Winternachten Festival in the Netherlands, Stellenbos Woordfees, Infecting The City Cape Town, and the Riddu Riddu Festival in Norway. He has two published anthologies: his debut being My Straat En Anne Praat-Poems (1998), and Die Faraway Klanke vanne Hadedah (2006). His recorded music & poetry include: A Moment In Cape Town, Sierjis Kak-Praat and the Goemarati Compilation.

Churchil is a hip hop artist and carpenter. Fine woodwork is his day to day. As he says about hip hop as an income, “daasie geldie, there’s no money. You do it because you have a passion. That’s it”. Loit says the same about being a poet. Churchil has been an MC since the mid 1990s, starting out in English. “I’ve got albums full of English material, but it was the discovery of Koos Kombuis’ album Elke Boomelaar’s se Droom that woke me up to my mother tongue as ‘great’, as the tongue that I had to use”. Churchil has collaborated widely in South Africa, recording with a number of his own musical mentors, including Anton Goosen, who he grew up hearing on the radio and TV (check out their video below, Boy from the Suburbs).

The Loit Sols Churchil Naude session will be intimate, just the two of them with guitar, voice and harmonica. If you’re in Cape Town, book your tickets here. If you can’t be there, catch the live stream with us!

Ngugi wa Thiong’o says “let our planes fly”

At a public lecture on June 11 at the University of Nairobi, Kenyan literary giant, Ngugi wa Thiong’o told the story of Gachamaba and Charles Njonjo. Gachamba was a bicycle repairman from Nyeri, in Central Kenya, who, in the late 1970s, built an airplane. He had no secondary education and spent his days tinkering with spare parts. His airplane flew for 9 miles. Charles Njonjo, on the other hand, was an exceptionally well-educated lawyer and the Attorney General of Kenya from 1978-1982. He heard about Gachamba’s short flight and, banned the flying of planes without a proper license. In Ngugi’s hands this story became an insightful metaphor for the Kenyan government’s habit of inhibiting the country’s talents.

Ngugi’s lecture was in many ways evidence of this. It was part of a series of public engagements to commemorate the first edition of his Weep Not, Child, first published in 1964 by East African Educational Publishers. Weep Not, Child was an anti-colonial novel, which marked Ngugi as independent Kenya’s most important and talented writer of fiction. Yet in subsequent years, as Ngugi’s criticism shifted toward President Jomo Kenyatta, the government began to get in the way. Ngugi was arrested in 1977 and in 1982, under Kenyatta’s successor, Daniel Arap Moi, he was allowed to go into exile with the veiled threat that upon his return he would be met by a ‘red carpet.’ He was away for 22 years.

Given this troubled history with the Kenyan state, his very public return to Kenya, which included a meeting with Kenya’s current President, Jomo’s son, Uhuru Kenyatta, was nothing short of historic. During the lecture, he joked about his imprisonment and exile and the irony that now, many years later the son of his incarcerator was receiving him at State House, on a real red carpet, and asking him to return home. Ngugi lauded this as a sign of how far Kenya has come, although he did not shy away from noting how far the country still has to go.

Kenya is less dictatorial than it was during the first Kenyatta and Moi eras, to be sure. But recent years have seen new laws controlling the media, the wanton detention of Somalis in Nairobi, the terrible decision to build a wall on the Somali border as well as the mystery disappearance of key witnesses in the trials at the ICC of both the President and the Vice President. The country is more democratic than it was, but many Kenyans are understandably leery of going back in time.

Before Ngugi’s speech, performances and speeches were given in his honor. One performance – a reimagining of Weep Not, Child – left many in tears. Actors reenacted the scenes in which the young protagonist is tortured on suspicion of being a Mau Mau, as well as parts of the book in which he is being taught English:

Teacher I am Standing. What am I doing?

Class You are standing up.

Teacher Again.

Class You are standing up.

Teacher You- no- you- yes. What’s your name?

Pupil Njoroge.

Teacher Njoroge, stand up. What are you doing?

Njoroge You are standing up.

Teacher What are you doing?

Njoroge You are standing up.

The scene continues with Njoroge getting more and more confused about pronouns, and we in the audience laughed and laughed at his mistakes. Later, Ngugi rebuked us all for joining in with the colonialist’s humiliation of Njoroge and making his proficiency in Kiswahili and Kikuyu seem inferior. He went on to note the story of Githunguri Teacher Training College, a school set up by Kenyans during the colonial occupation. As the colonizers began to ban African schools, Githunguri was turned into a prison in which they would hang people suspected of being Mau Mau. The significance of desecrating an institution celebrating Kenyan educators, and subsequently turning it into a site of murder, speaks volumes of the violence that was done to the Kenyan mind during the colonial regime.

The connection between education and colonial dominance has long been one of Ngugi’s primary concerns; he deployed many of his harshest words for independent Kenya’s failure to redress this legacy. In publications like Decolonising the Mind he chastises those who fail to understand why it is so harmful for us to laugh and humiliate those who do not, as he wrote in Devil on the Cross, “speak English through the nose”. Ngugi was instrumental in developing the Literature department at the University of Nairobi, where, for a time, they were able to develop a syllabus for Kenyan secondary schools featuring books from Africa, Asia and Latin America, not just Europe. However, much in the same way as Njonjo would not allow Kenyan engineering to flourish, the Kenyan government responded by abolishing literature in secondary schools.

And so, after lamenting this intellectual loss, the Professor warned that even 52 years after independence, as Kenyans (and Africans in general) continue trying to perfect their English or French, foreigners continue perfecting their instruments of access to Africa’s resources. He renewed his old, still unheeded call for the government to do whatever it can to allow Kenyans to make their own futures in the way of Gachamba, not the way of Njonjo, and to let their own planes fly.

Gazing at a distance?

Two exhibits at the same museum: one seeking to deconstruct the white Western gaze, the other perpetuating it.

I, a Lacanian subject of desire, return to C/O Berlin, the center of photography that recently reopened at Amerika Haus at the very nerve center of tourism and culture in the German capital. As someone engaged in a critical dialogue on sociopolitical issues of representation in globalized visual culture, I could hardly miss seeing this traveling exhibition. Its eloquent title, Distance and Desire: Encounter with the African Archive, announces its preconceived purpose upfront: asking questions as to the role of archives and the impact of the photographic image in the writing of history. The project was organized into three sections, beginning with photographs from the Walther Collection and juxtaposing images from historical archives of photos taken in southern and eastern Africa around the turn of the twentieth century with works by contemporary artists from African perspectives whose approaches seek to reinterpret the ethnographic and colonial archive. From the outset, the visitor is clued in: it is impossible to view these photographs without realizing the violent relations inherent in European colonialism in Africa, and equally impossible to detach them from the historical contexts in which they were produced. The displacement of these archives invites us to examine our own gaze with a certain critical distance in order to reflect upon the processes of identifying and constructing difference, especially racial and gendered difference. The project re-envisions the archive as the bearer of collective memory, restoring the agency and individuality of the subjects portrayed and thereby creating alternative narratives of history.

Women of Zo’e tribe, in Amazonas, Brazil. Credit: Sebastiao Salgado (Amazonas Images)

In parallel to Distance and Desire, the Genesis project by photographer Sebastião Salgado intones an ecological message to humanity. These purportedly “socially conscious” photographs, which amount to a romantic invitation on an “eco-tourist” journey, perpetuate the representation of ethnicized bodies beside immaculate landscapes in black and white. The portraits’ subjects are made anonymous, their identities reduced to objectifying and vulgarizing captions that describe their practices and customs. Considering that both cultural visions are embedded in the same globalized, post-migratory space, it seemed to me that despite the Distance and Desire project’s noble intentions to deconstruct the white supremacist gaze, an ambivalent complicity might lodge in visitors’ minds. Thus I was compelled to interrogate both exhibition spaces jointly in light of the problems of images’ circulation and the act of “making visible.” How is the viewer positioned in relation to the discursive powers of representation? What relationships are formed between the photographer as an auteur, the individual photographed, and the viewer? At what point does the act of observation begin to dictate the subject’s development?

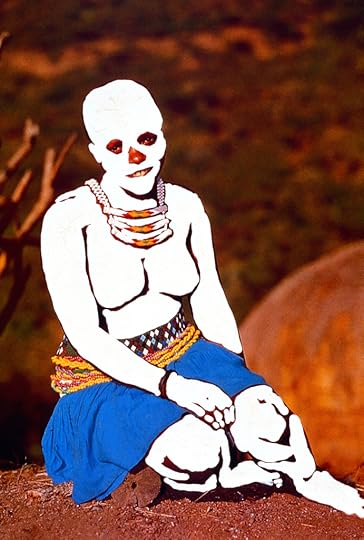

Candice Breitz Ghost Series #4, 1994-6.

The exhibition statement at the entrance to the Distance and Desire exhibit explains that colonial photographic representations are productions manufactured by an immense diversity of forms. They constituted a major commercial enterprise intrinsically linked to the cultural emergence of modernity. Glorifying the ability to capture reality, photography was employed to construct the identity of the modern subject, resting on Eurocentric racial ideology. As such, for a long time photography was a technological object of fascination enlisted on the perpetual quest for progress within a historiography of Western civilization as the sole model of emancipation. The statement clarifies that the captions beneath the ethnographic photographs are direct copies of their original racist, archetypal labels. Equipped with this knowledge, the visitor must liberate her gaze from the potency of the archival images.

In the first room of the gallery, I find a series by the contemporary South African artist Santu Mofokeng. His project The Black Photo Return/Look at Me: 1890–1950 displaces the archive from its original context of production. Through exhaustive research, the artist has re-appropriated photographs of middle class South Africans of African descent in order to restore the individual memories transported in the images. The identities of the photographic subjects had been made anonymous in the course of archival work. The accompanying statement tells visitors that these self-representational images were often intended for consumption as souvenirs to be taken home by foreign travelers. The work underscores the photography industry’s ambivalent establishment and application in the early twentieth century, which extended, by way of representation, the socio-normative construction of the modern identity. In the colonial context, the photograph was harnessed as a tool for supporting racialist discourse and human subservience while serving as a cultural object destined for consumption, since it could be reproduced and circulated beyond national borders. The South African curator Tamar Garb opted for the comparative method as a way to demonstrate this deconstructive dialectic of archives’ representational power. Accordingly, Mofokeng’s work is displayed in tandem with The Bantu Tribes of South Africa(1924–1954) by the Irish-born South African photographer Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin whose ethnographic study aimed to preserve traces of tribes on the path to extinction. There, in contrast to the metropolitan subjects whose agency Mofokeng restores, the photographic subject is encased in a vision that is frozen in time, portrayed as primitive and fixed within an “authentic elsewhere” at the heart of the natural environment. The captions assign individuals fixed categories within a male/female gender binary or classifies them based on the sociocultural activities they practice. This staging fosters the subject’s objectification rather than subjectification. The nude bodies subjugated by the photographer’s gaze are conspicuously posed, laid bare and sexualized in imaginatively orchestrated arrangements following aesthetic principles tied to the representation of Western phallocentric art – evoking disconcerting similarities with Salgado’s outlook.

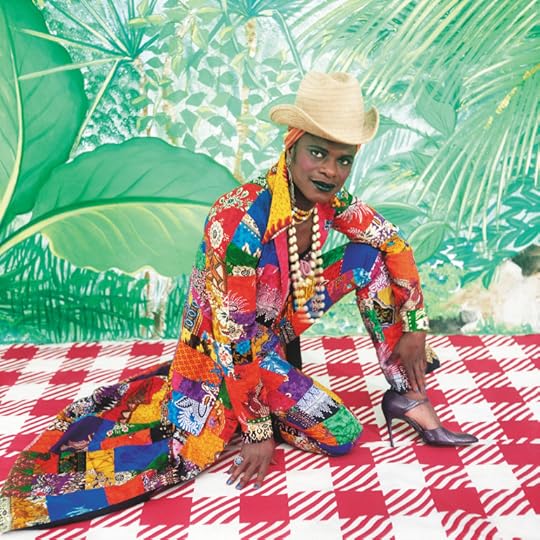

Samuel Fosso, La femme américaine libérée des années 70, 1997. © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Jean-Marc Patras, Paris.

Tamar Garb speaks to the importance of keeping in mind that images possess multiple lives over the course of their spatial/temporal circulation, resulting in an evolving gaze and a tangible re-reading of their original narrative. As Mofokeng sees it, this makes it possible to negotiate the colonial archive and consequently to construct a counter-archive [1]. This analysis is clarified by the second section, Contemporary Reconfigurations, in which the archive’s displacement gradually affirms that these fateful images indeed contain this paradigm of representing the modern identity of the African subject, albeit racialized and Westernized at times. Bit by bit, the codifications of Western identity have been re-appropriated in order to create an African modernity in the very heart of that segregated universe. Finally, this repositioning of memory is supplemented by a third time re-reading the colonial archives. This time it comes from a gaze interspersed with contemporary artistic perspectives, which, for their part, highlight the self-definition of the ego, engaged in a process of relativizing history in terms of the construction of cultures and identities in our modern-ized society. Nevertheless, trapped within a device of museumification, the archive appears to have been fetishized as a work of art commensurate with contemporary art photography. Are the two disciplines being compared? Will archival images then be circulated in the world economy like a commodity, arousing our desire to possess and satisfying our need for mass-cultural entertainment?

Visitor at Sebastião Salgado’s Genesis-show in Berlin. Credit: Borkeberlin

In this light, the close proximity to the Genesis exhibition is troubling. The highly successful exhibition re-envisions the myth of the noble savage through its white, ethnocentric photographic lens. Otherness is endangered and the visitor’s modern individualist subjectivity is consoled, as the artist beneficently defends nature and champions human rights. If we wish to deconstruct that binary gaze, interfere with the construction of identity, and engage more actively in representation as difference [2], we need to stop pretending that we all enter an exhibition space looking through the same prism. Standing in front of images can cause us to neglect comparing them with their antithesis or envisioning alternative modes of presentation. If we want to critically expose the violence of their representation, we need to make sure to arm our audience with analytical tools adequate to thwart the perpetuation of racist stereotypes by way of cultural representations. In my view, it is more than fundamental to ask questions today in an age when the culture is increasingly constrained by the principles of the neoliberal free market.

Distance and Desire: Encounter with the African Archive – African Photography from the Walther Collection, shows from April 18 – June 14, 2015, at C/O Berlin.

[1] Remarks gathered at the lecture Curatorial Conundrums: Encounters with the African Archive, given by Tamar Gelb about the exhibition at C/O Berlin (18 May 2015).

[2] Refer to Stuart Hall’s concept of politics of difference, which consists of engaging modes of producing a difference articulated at the very heart of the subject and contextualized in an environment of sociocultural differentiations, in which the subject pursues his quest for identity with the aim of breaking off from a politics of essentialist identity.

This post originally appeared on the C& website.

Wasila Tasi’u is fifteen years old and out of prison

In the state of Kano, in Nigeria, last year, a 14-year-old girl, Wasila Tasi’u, was charged with the murder of 35-year-old Umaru Sani. Wasila had been forced into marriage, and a week later, Umaru Sani died of rat poison ingestion. Despite calls from national and international women’s groups, the girl was tried in adult rather than juvenile court. As her lawyer Hussaina Aliyu, of the International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) said, “All we are saying is do justice to her. Treat the case as it is. Treat her as a child.” Wasila was questioned without parents, guardians or attorney present, and she confessed to the murder. No one had to confess to the forced marriage, despite the Child’s Rights Act of 2003, Section 21, invalidating any marriage contracted by anyone less than 18 years old. Her parents explained that in their region, girls marry at 14 years. According to Zubeida Nagee, a Kano-based women’s rights activist, Wasila “protested but her parents forced her to marry him.”

On June 9, the State notified the judge of willingness to drop the case, and the judge complied, saying, “I have no alternative than to pronounce according to the law that the application for nolle proseque is hereby granted.” Wasila Tasi’u is no longer behind bars, but she can’t go home again. Under the care of the Isa Wali Empowerment Foundation, Wasila will live with a foster family … perhaps for the rest of her childhood.

According to a recent editorial in the Vanguard, “Rape? No; Infant Marriage? Yes”, the State response to all of this has been regressive. The editorial explains, “Section 29 (4) (a) of the 1999 Constitution, states, `full age’ means the age of eighteen years and above; (b) any woman who is married shall be deemed to be of full age.” With a deft hand, the legislators wrote a bill, which now sits on President Buhari’s desk, which retains the second clause while eliminating the first. If the bill becomes law, a girl entering marriage, forced or otherwise, would thereby attain “full age”. Problem solved.

Wasila Tasi’u was released from prison, and from a possible death sentence, because of the work of countless dedicated Nigerian women, individuals and groups. Wasila Tasi’u found a new home, hopefully one where she will grow healthy, learn to read and write, and enter into full womanhood, thanks to the work of countless dedicated Nigerian women. Hopefully, she will join the countless women’s groups that are organizing across Nigeria, in the courts, legislatures, streets, workplaces, clinics, schools and households.

Wasila Tasi’u is now fifteen years old, the same age Malalai Yousafzai was when she was almost killed. We stand on the shoulders of giants, who turn out to be adolescent girls.

June 22, 2015

Vamba Sherif’s ‘Bound to Secrecy’ is masterful storytelling

In 2012, The Economist Magazine’s style blog, Prospero, featured an essay titled “War and Peace in Monrovia: Where is Liberia’s Tolstoy?”. The essay was written by a journalist who visited Liberia for research on a magazine feature about an ex-warlord running for president. While in Freetown, during what he explains was an unexpected amount of free time, he began to read Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. The essay then becomes an exposition of writer’s annoyance with his stay in Liberia, with the usual jabs at the weather, lack of book stores, devastated infrastructure and other issues typical to traveller’s Facebook updates. The author’s main complaint, however, was that Liberia lacked a writer who had made a successful attempt at publishing an epic-length civil-war era narrative, and to a lesser extent, competent writers in general; these failures, he argued, was indicative of the trajectory of the country and the psychology of its people.

He’d clearly never heard of Vamba Sherif. By the time this essay was published, Sherif had authored 4 books: The Land of the Fathers (1999), The Kingdom of Sebah (2003), Bound to Secrecy (2007), and The Witness (2011). Sherif’s third novel, Bound to Secrecy, is a detective novel based in a remote Liberian border town, Wologizi. The story’s protagonist, William Mawolo, visits Wologizi to investigate the disappearance of the paramount chief, but hostility from locals frustrate his efforts at arriving at the truth. He asserts his authority over the town, and in doing so exposes himself to danger. Bound to Secrecy was first published in Dutch and recently published in English by London-based Hope Road Publishing. The action takes place in the fictional forest town of Wologizi in Liberia; there, a detective named William Mawolo is sent by Old Man to investigate the disappearance of a town Chief named Tetese. A storyteller by trade, Tetese suddenly disappears, and Mawolo finds himself navigating a maze of unbelievable testimonies, dubious allies and eventually, fear for his own safety. His puzzling time in Wologizi is only coaxed by his love of a surprising ingénue, Tetese’s daughter, Makema. Sherif’s thorough knowledge of Liberia’s complex political system also contributes to this world of rich and diverse characters—a Corporal Gamla widely known as “The Torturer,” Old Kapu, a host with many wives, the Lebanese shop owner the residents of Wologizi refer to as “Baldhead”.

With every page, the reader shares Sherif’s main character’s confusion, and as the book progresses, becomes unsure of which testimony to believe, which character is trustworthy, and which encounter is a main event. Each character’s rendition of the events around Tetese’s disappearance contradicts the last, exploring themes of community, loyalty, superstition and narrative traditions made famous by African storytellers. Conventional Western narrative traditions are incorporated, but Sherif is not trying to be Tolstoy in order to prove himself worthy.

Sherif is a master storyteller whose multi-linguality is definitely evident in the lyricism of his writing; the translation to English doesn’t lose that quality. He tells stories of Liberia for the Liberian reader, without pandering to or losing his Western readers’ ability to get the culturally specific references in his writing. Sherif’s honesty in framing this contemporary Liberian town, still deeply rooted in the superstitions and sexism of traditional, insular inland communities, is refreshing, its impression lasting, haunting. As with all detective stories – and with life – the answer to the riddle is under William Mawolo’s nose the entire time.

Taking White Privilege Abroad: On “Ex-South Africans” and the White Diaspora

They didn’t nickname Ra’anana, a posh Israeli suburb north of Tel Aviv, “Ra’ananafontein” for nothing. There, and in the neighboring town of Herzliya, thousands of White South African immigrants – all Jewish, overwhelmingly Ashkenazi – settled in a tight bubble. One can live an entire life in Israel with a social circle wholly composed of White South Africans. Curiously, many of these transplants identify as “Ex-South African.”

At first, I considered this to be a peculiar quirk of the diaspora community in Israel. Yet it turns out many other white expatriate communities also use this term. When white migrants claim to be “ex-South African,” their statement is that South Africa is no longer their country – the political implications of which, only two decades since the end of apartheid and in the era where Rhodes is still falling, are retrograde. This is famous in South Africa as the stereotype of the packer for Perth, but exists in a very real way from Auckland to London to Israel.

In the Western countries where they settle, White South African migrants benefit from systems of power that reward them for being white in skin color and Western in culture. Thus, when some lament the attenuation of such privileges in South Africa, they gain greater access to hegemonic white identities in their host states.

This performance in their host states has two consequences worth elaborating: it plays into being “good whites” and it plays into the military politics of their destination states.

Many of the émigrés take great pride in being “the right kind of migrant.” Right-wing white migrant forums and newspapers proclaim their success in things that host societies tie to a very specific sort of Western whiteness: witness celebrations of emigrants’ business success in wealthy suburbs, or proclamations of how “South Africans blend in,” or “South Africans know how the rules work.” The fact that many migrants were wealthy is celebrated as “contributing to the country” and “unusual and unique” – even though, when examining statistics, South Africans are neither unusual nor unique.

I have often heard a certain sort of South African émigré state this opinion: “we made Ra’anana Western and habitable,” or “we were the kind of immigrant San Diego needed.” The implication in regards to South Africa then becomes clearer: you can almost hear them claiming the same of Johannesburg or Pietermaritzburg. Indeed, similar comments abound on some far-right expatriate blogs like this one.

This performance of the “good migrant” feeds into a widespread support of relevant countries’ militarist nationalisms. Many migrants support the nationalist or populist parties of their adopted countries: it was not a few times in internet-based research that I found mentions of UKIP in the UK, or praise for the most reactionary of Tony Abbott’s immigration policies in Australia. Urban blight in Johannesburg was compared to nightmarish and racialized scenarios of “the Muslims taking over in Bristol,” and was followed by nostalgia for “pre-1994” South Africa or the “good old days” of safety and white police control.

It is an open secret that many white diaspora members are nostalgic for apartheid – and this position is always informed and colored by the local context. Nowadays, we see this in chain emails castigating the Black Lives Matter protests in the United States. These logics extend to military action itself: the communal publications of Israel’s South African community are filled with praise for “security operations” in the West Bank and adopt a congratulatory tone for Israel’s military that is considered right wing even in Israel.

Of course this white privilege and nationalism can be read as anything but “Ex-South African.” The memories of a militaristic, apartheid-era whiteness narrated as a Western fort on the “dark continent” are never far from the surface. The pride in being the “right sort of migrant” to support “the needs of our nation” draws on the narratives of a South African whiteness that presents itself as normal, hegemonic, and good. The continued existence of “ex-South African” communities themselves demonstrate the continued identification with South Africa as a place of origin. That said, the South Africa these migrants – and the right-wing white strains of South Africa’s diaspora – identify with is the South Africa of apartheid.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers