Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 342

June 6, 2015

The African Champions League Final in Berlin

If the New York Times can try to make today’s UEFA Champions League Final all about America on the spurious basis that Gigi Buffon might end up coaching the US team some day, then we should have no trouble making it all about Africa.

Barcelona, the heavy favourites, don’t have the African superstars they used to — Yaya Toure, Seydou Keita, Samuel Eto’o — but the Juventus squad includes Ghana’s Kwadwo Asamoah, Italy’s Angelo Ogbonna and the French pair Patrice Evra and Paul Pogba.

Evra will have to try to stop Messi, Neymar and Suarez. Suarez and Evra have history, as many people know, and Evra, 34, would surely love to celebrate a Juve win by rubbing Suarez’s nose in, as he famously did at Old Trafford a few years ago.

Suarez is a remarkable character (the biting) and an extraordinary footballer (the scoring). Davy Lane’s piece, The Suarez Conundrum, is perfect pre-game reading.

Fewer people know how interesting Patrice Evra is.

Today is Evra’s fifth Champions League final, though he’s only won it once. He was captain of France, but the French dislike him intensely. (As we know, the French have serious issues about what their national team looks like all these years after the end of empire).

His decision to represent France rather than Senegal angered a lot of people: “I was called a monkey who grovels for the white man and labelled a money-obsessed traitor to the nation.”

Born in Dakar to a Cape Verdean mother and a Senegalese diplomat father, he grew up mainly in the Paris suburbs.

Evra speaks seven languages, including Wolof and Korean (which he learned in order to chat with his former teammate Ji-Sung Park).

In 2010 the legendary Lilian Thuram called for Evra to be permanently banned from the French team for his role during the World Cup fiasco, though we maintain that nobody with any sense could have put up with the buffoonish French coach, Raymond Domenech.

Evra’s team-mate for Juventus and France is Paul Pogba, 22, widely regarded as the best player of his generation. Pogba used to play for Manchester United, but turned his back on the club and Alex Ferguson when he didn’t give him enough playing time. Back then, many in the UK criticized Pogba as arrogant and said he’d regret leaving Manchester and the English league. A few years down the line and Manchester United would have to pay upwards of £70 million to bring him back.

Pogba’s parents are Guinean, and his brother Mathias plays for Crawley Town and the Guinean national team.

Weekend Music Break No.76

We took a break last week, but we’re back experimenting with a new format. This Weekend’s Music Break is in the form of a Youtube playlist so you can just hit play, sit back, and enjoy. Let us know if you have any thoughts about the new format in the comments!

Our selection this weekend is:

1) A dedication to today’s Champion’s League Final with the Eto’o Coupe Decale dance.

2) P-Square and Awilo Longomba’s new “Enemy Solo”.

3) Angola’s Mery with “Fogo cruzado” feat. Ksuno Beat.

4) South African rapper Boolz with “Aphe Kapa”.

5) Nigerian-American rapper hits the studio with friends in “Roslin’s Basement”.

6) Italian-Moroccan rapper Maruego brings a controversial subject to the small screen with “Sulla stessa barca,” which translates to something like, “we are all in the same boat.”

7) A group of DJs from around the world collaborate on an impressive live “Scratch Jam”.

8) Lisbon’s Batida releases a video for beautiful “Ta Doce” feat. AF Diaphra.

9) Haiti’s Beken sings “Tounen Lakay” in a live session.

10) Finally, Y’en a Marre gets a half-hour documentary on MTV’s rebel music series.

Are corrupt Africans really ruining FIFA?

We all know, thanks to the English FA chairman Greg Dyke and many other bigoted media commentators, that corruption at FIFA is caused by small African nations where greed is “cultural.”

Just yesterday the man who runs English football (and used to run the BBC) had this to say:

[The investigation into FIFA] is not colonialism at all. But there is no doubt that there are a set of values which you find in western Europe, and in America, and in Australia, that don’t apply everywhere. My experience in Africa is that when people go into politics in Africa, it’s incumbent upon you as part of that to look after your family. That’s just cultural, it’s a cultural difference.

Of course politicians in predominantly white countries that aren’t Africa have no interest at all in “looking after” their families. Everybody knows this, right?

Just look at the Clintons, for example. Virtually destitute at this point, are the Clintons. They got so poor due to their devotion to selfless and low-paid public service that they had to start relying on meagre multi-million dollar donations to the Bill, Hillary & Chelsea Clinton Foundation to scrape a living.

Or the Bushes. One of the Bushes became president and the rest have been left to languish in obscurity. The Bush boys had to make do with a string of menial jobs — running oil companies, owning baseball teams, governing the states of Florida and Texas, being the President of America etc — because their father was a man of such unstinting probity that he simply wouldn’t countenance his kids getting any advantages over common folk.

Nope, it’s definitely just the Africans who “look after their family.”

And so it’s the Africans who’re to blame for FIFA’s troubles, particularly “small African nations” for whom giving and receiving bribes is just part of the culture. Just look at all the revelations in the past week or so. The pattern is clear enough. Let’s run through some of them.

The small African nation of Germany reportedly did a massive arms deal to secure Saudi Arabia’s vote for World Cup 2006. Gerhard Shröder, then Chancellor of Germany and a classic African despot, is said to have been behind the deal. The Guardian reports serious allegations: “that the German government lifted arms restrictions days before the vote in order to make the shipment and help swing Saudi Arabia’s vote to Germany.” What else can you expect from a tinpot African country like Germany, eh? I guess they were just looking after the family. It’s a cultural thing.

Another corrupt African official is Chuck Blazer, who for many years ran soccer in the little-known African nation of the United States of America and took all kinds of bribes and kickbacks.Like the classic African despot that he is, Blazer spent his ill-gotten gains on fripperies like a luxurious Manhattan apartment for his herd of cats. You see, it’s corruption in tiny, impoverished countries like this that needs to be stamped out. They’re ruining it for everyone and until the big, powerful countries have all the power in FIFA, nothing will change. As pollster Nate Silver recently suggested, it would be much better if only rich people had influence over FIFA.

Then of course, there’s the Irish African Republic, which in the manner of corrupt African nations everywhere, was paid off by a 5 million Euros bribe from FIFA to go away and shut up when they were upset about Thierry Henry’s handball.

And don’t forget the eastern-most of all African islands, Australia, which used taxpayers’ money to pay bribes in support of its bid to host the World Cup in 2022.

They said it was only African nations that were supporting Blatter. But of course we knew long ago that France, who voted to re-elect Sepp Blatter last week, had joined the African continent.

We at Africa is A Country would like to extend a warm welcome to Africa’s newest member states, including Germany, Australia, Ireland, France, and the United States. They do say Africa is growing!

This FIFA business has really redrawn the map of Africa. At this rate, FIFA will have to expand the number of places Africa is allocated at the World Cup quite substantially.

(None of this, by the way, is in any way a defense for the many corrupt and unaccountable officials right around the world who are doing football a disservice. Journalists everywhere need to be much more forceful in subjecting them to proper scrutiny, and the teeth of FIFA’s reform must be focused at the local level.)

I’ve been doing lots of media interviews this week on FIFA, and the question that keeps coming up is whether they should dump the inclusive and democratic “one-nation-one-vote” system, which they say gives too much power to African and Asian countries.

Next time an interviewer asks me, I’ll just say yes they should scrap it, because it gives too much power to corrupt nations like Germany and the United States.

Of course, that voting system needs to stay as the bedrock of an inclusive, accountable FIFA for the future. The connection between specific cultures/regions and the corruption revelations is totally spurious.

I tried to explain this in an article for The Guardian:

A staple of European and American reporting on Fifa in recent years has been the idea that its voting system (which grants equal representation to nations regardless of size, wealth and footballing pedigree) lies at the root of corrupt practices of the kind outlined by the US lawyer Michael Garcia in his report and most recently by the US Department of Justice.

The wonderful investigative reporter Andrew Jennings offered a classic example of this unhelpful conflation of separate issues when he told the BBC last week: “Frankly, if the next World Cup is Guinea-Bissau v Tanzania, that will say it all.” Neither country was remotely associated with the particulars of the recent indictments – these were chiefly concerned with dodgy dealings involving sports marketing firms in North and South America – but for Jennings the notion of small non-western nations having decent standing in the game is evidence enough of Fifa’s corruption […]

Arguing that Fifa’s one-member, one-vote system is what causes corrupt practices in football is like arguing that corruption scandals in British politics (for example, the “cash for access” sting that suckered [parliamentarians] Malcolm Rifkind and Jack Straw) are the result of each constituency in the country electing a single MP regardless of population or historical importance. There is no basis for it: it’s hogwash. Those who repeat this twaddle do so only to gloss with a thin veneer of respectability their view that football should be run in the interests of a small group of big-hitting nations and to hell with everybody else.

It’s also been noticeable how little the longer history of FIFA has been discussed. Again, this isn’t to defend local officials anywhere who might use this to cover their ass, but to point out that fears that football could be run by and for the West at everybody else’s expense are hardly without a basis in history. As Sean Jacobs and I wrote here (prior to Blatter’s re-election and resignation):

In 1974, the Brazilian Joao Havelange defeated [England’s pro-apartheid] Stanley Rous by marshaling an alliance of non-Western nations, many of them emerging from colonial rule, whose interests had hitherto received scant representation within FIFA. It is that same bloc that first elected Blatter in 1998, and which he will rely on if indeed FIFA presses ahead with this week’s scheduled election.

Blatter’s last serious challenger for the FIFA presidency was the Swede Lennart Johansson, then president of Europe’s governing body UEFA, who ran against him 17 years ago. Johansson was lionized in ESPN’s recent film (one gets the impression there’d be none of this corruption if he had become FIFA President), which failed to mention that one reason he lost that election was that he was perceived as a racist.

A Swedish newspaper published an interview with Johansson in 1996 in which he was quoted as saying: “When I got to South Africa the whole room was full of blackies and it’s dark when they sit down all together. What’s more it’s no fun when they’re angry. I thought if this lot get in a bad mood it won’t be so funny.”

It turns out that the good old days were actually pretty bad old days. Those who want Blatter out and FIFA reformed have to deal with that history and that reality, and accept that a global organization where Europe and America has disproportionate influence would also be corrupt.

For more, check my piece for Al Jazeera on what the future of FIFA should look like. There’s also an episode of The Stream where I talked about some of this stuff with Shaka Hislop and Jerome Champagne.

Finally, two excellent posts by the economist Branko Milanovic on his blog: The real stakes behind the FIFA scandal, and The age of open financial imperialism. Both highly recommended.

Protect the game, it belongs to everyone.

June 5, 2015

Are Beethoven’s African Origins Revealed By His Music?

Historical debate on German composer’s Ludwig Van Beethoven was reignited on June 1st 2015, when a collective of Historians and musicians published a website named Beethoven Was African.

The collective ambitions to provide a different lens with which to appreciate the legacy of Beethoven, by re-focusing the debate surrounding Beethoven’s origins on the core question: his music. In the following interview, ANY, a member of the collective and the pianist who plays the sonatas in Beethoven Was African: Polyrhythmic Piano Sonatas, gives us some more insights on the results of the research.

…

When you say “Beethoven Was African” what do you bring that the many other theories that already exist on the possible African ancestry of the composer don’t?

Our research provides a new interpretation and new keys to understanding the music of this composer, as well as to the many mysteries that exist in his biography that have not been resolved to date. For instance, why did such an important man for his time not have a valid baptismal certificate, or a birth certificate? Why was his identity subject to so many rumors and conjectures during his lifetime? This project aims to bring a new biographical light on the composer’s life, and offers a new way to understand and play his musical work.

Ludwig Van Beethoven had a precise and almost absolute knowledge of polyrhythmic systems and patterns from the Gulf of Guinea Region, on the West African coast. Although they are unwritten, I would even say that these West African traditional polyrhythmic patterns, which still exist, were fundamental to his work as a composer. Ludwig Van Beethoven has achieved the perfect synthesis between polyphonic modes and tonal system, developed in Europe in the centuries that preceded his era, with polyrhythmic system and patterns from West Africa.

When playing this music, with this awareness of the polyrhythms present in the work of Beethoven, the music magically becomes clearer, more harmonious, more beautiful.

The album Beethoven Was African is the demonstration of this discovery. By what magic effect do these polyrhythms allow us to discover the multitude of melodies present in each part of the piano sonatas? How come these polyrhythms allow us, for the first time in the history of the recording of these music pieces, to cleanly hear the part played with the left hand, to hear the rhythm of the latter, to reveal its hidden polyphony, and not consider it anymore as a simple accompaniment of the melody played with the right hand?

If you compare the pieces of the Beethoven Was African album with their equivalents in previous recordings of 20th century pianists, for example, you will realize with astonishment that the left hand appears almost with no rhythm, no soul. By listening carefully to the musical pieces contained in the Beethoven Was African album, you will hear that some parts induce something like a swing motion to the listener. These sonatas therefore induce something that was absent in Beethoven’s music so far: dance. It occurred to me that it was impossible at some point to bring out the real nature of Beethoven’s pieces of music, I would even say to recreate the music as the composer played it, if I dismissed the polyrhythmic patterns that guide almost all the piano masterpieces of Ludwig Van Beethoven.

This discovery of polyrhythmic patterns identified in the score left by the composer fed the biographical research. It was necessary to understand why the composer had this polyrhythmic ability, and who had transmitted it to him in this Europe of the late 18th century.

In regards to the biographical research, the project is new because of the method used. Previous research on the African origin of the composer relied mostly on passages from 19th century biographies on the composer, which never explicitly mention an African identity for Beethoven. Historians involved in Beethoven Was African project questioned documents and artifacts produced while the composer was alive: correspondence, cultural journals, portraits, the writings and sayings of his contemporaries. It is this method of historical investigation that allowed us to move forward and discover unpublished documents, and finally to unravel what is probably one of the greatest mysteries in the history of art.

Why do these 19th century biographers, those who are authoritative today, not mention this African origin?

Because this African identity has been concealed throughout his life by the composer himself. The political and social condition of African or African descendants residing in Europe between 1770 and 1827 explain the adoption of this public image strategy. During Beethoven’s lifetime few people knew his face. He was obsessed with a strange paranoia and kept changing domicile. He moved into at least 67 homes in Vienna alone. Sometimes he lived in 2 or 3 residences simultaneously, so that no one could never really know where he was. An anecdote: one night in 1821 he was arrested on a street in Vienna and brought to the police station. The head of the Vienna Police ignored his true face and was unable to authenticate him, despite the fact that Beethoven had been living in Vienna for at least 20 years. The police chief had to call the director of the Vienna Opera, who was one of the few people who had already met the composer. A strange thing when you consider that Beethoven was at that time the most famous Austrian composer.

Beethoven had a decisive influence on the narrative that was to prevail on him after his death. If he did not write his own memoirs, he dictated them before his death to Anton Schindler who was his secretary during the last 4 or 5 years of his life. The composer himself had chosen his biographer. The biographies published after Schindler’s Beethoven as I Knew Him are variants of this fascinating story that we all know, of this “romantic hero”, created by the composer himself and dictated to his secretary. In addition to being among the most brilliant composers of all time, he certainly possessed an unmistakable narrative genius.

Indeed this original biography would serve to remove the family background controversies that persisted in music and aristocracy circles in Europe in the early 19th Century. It is this illusion created by the composer, hiding his face behind false portraits, that allowed his first biographer to compose a plausible story that completely eluded persistent questions related to his identity.

What questions about his identity existed in his lifetime?

Who were his parents, for example? It should be noted that this issue was never resolved in his lifetime. Seven successive editions, between 1810 and 1817, of the Paris dictionary of musicians assume that Ludwig Van Beethoven could be the natural son of Frederick II of Prussia. This statement is echoed by other newspapers of the time. For instance, Harmonicon, the most serious London-based music magazine in the 1820s, repeats that assertion in its biography of the composer published in 1823. There is an explanation to this rumor. Frederic II of Prussia was known to own numerous court Kamermohrs, or African room servants.

Frederick the Great as a child with his sister Wilhelmine – Antoine Pesne 1714 via Wikiart

These African slaves were children who had been deported to the European continent, and had the function of being companions for children of the European high society. In writing this, the dictionary of musicians of Paris made it clear to insiders of European courts that Beethoven was the fruit of adulterous sex of the Prussian king and one of his kamermohr. A year before his death, Beethoven was asked once again by one of his relatives about this rumor. He refutes, leaving some doubt, as usual, about the identity of his biological father saying, “Make the true details of my parents, in particular those of my mother, known to the world.”

Afrodescendants in 19th Century Europe had no birth certificate. This was the case of Beethoven. This lack of a birth certificate caused him a lot of trouble in his life. Today, a debate persists on the authenticity of the birth certificate attributed to him. What is certain is that Beethoven himself has on at least three occasions explained, via correspondence to his entourage, that the birth certificate considered authentic today was not his. One of the reasons that prevented one of Beethoven’s weddings from happening was precisely that lack of birth certificate. Similarly, he lost the first part of the trial for the custody of the son of his deceased half-brother. This was because he was unable to provide a credible birth certificate on his filiation.

Why does the portrait of the composer that we all have in mind represent an individual with absolute European phenotype?

You certainly talk about the portrait painted in 1820 by Karl Stieler. It was on the order of Beethoven, even though he paid the artist through a third party. In a letter in which he sent a lithographic reproduction of this portrait to Karl G. Wegeler, a close friend who knew his face, he wrote that it was an “artistic masterpiece”; because unlike the previous ones, this portrait goes very far in the distortion of his features. It was not until the late 19th century, when the myth that he had himself helped to create became the official story, that this portrait began to be disseminated. After the composer’s death, 19th Century art critics regularly published notes on the evaluation of the existing different portraits of Beethoven. Stieler’s portrait was systematically put aside when these critics took the trouble to interview the composer’s living contemporaries.

During his lifetime, Ludwig Van Beethoven concealed his face through false portraits for which others posed in his place. We have at least 13 portraits and engravings that he personally authenticated as depicting his features, but which show at least 7 individuals with different faces and features. Ludwig Van Beethoven definitely had an advanced understanding of the power of image. Without forcing the line, we can say that Beethoven shaped and transformed his public image, in the manner of a Michael Jackson, but two centuries before him. He had no plastic surgery at the time, however he had portraitists who lent themselves to this game of illusion, mainly because they were paid to do so. Beethoven also took advantage of a significant innovation born in Germany in the late 18th century: lithography. By reproducing false portraits and spreading them in European capitals on the cover of his scores, he was certain to sell much more than if he had shown his true features. Among these portraits produced during his lifetime, and for which Beethoven is deemed to have posed, can we find his true face, or is it lost forever?

Fortunately for us, the composer has left some clues about his real face, a puzzle that has allowed us to identify with certainty his real features. We believe we have found them in a sketch by French painter Louis Letronne, drawn in 1814, and whose original is probably lost today. A copy of this sketch, lithographed in 1837 by another French, Frederic Hillemacher, was preserved [it is featured image on this post].

How can we be certain that this is the only authentic portrait with the true features of the composer that has passed to posterity? Well, we do know that Beethoven had contracted smallpox as a child, and that this disease partially disfigured his face, leaving characteristic marks. In particular, he had a deformation on the left side of the upper lip, and many scars on the left side of his face above the nose and between the eyes. These marks show up in a mask molded over his face by Franz Klein in 1812, and if you look at Hillemacher’s lithograph, the same scars appear at exactly at the same place.

The reasons that lead the composer to conceal his features and his origins during his life are understandable. Why has did he also have the desire to deceive history after his death, since you’re saying he is the author of the biography that we know of him?

There are two reasons he was careful to organize his image for posterity. First, he must have thought that the rumours and social pressures existing during his lifetime would continue immediately after his death. What would have happened if in the 19th Century, historiography had discovered this deception? The risk was that his music would no longer be played. He had spent his life convincing the public to believe that he had only European origins. After composing one of the most important monuments of the history of art and the human spirit, he wished above all that his work would be passed to posterity.

A second, more important reason exists: to play his music as he played it, to understand it, to hear it, so that it produced the same enchantment as when he played or led it when alive, one had to understand that an important part of the music education that he received in his childhood and early adolescence was an intimate knowledge of polyrhythmic science and art. And, he was a bit of a joker. He must have been amused to see that with the scores he had produced, interpreters were unable, and still are, to produce the same music that came out these texts when he played it. He often said, “It will take at least 50 years before my music is understood.” In actuality, his calculation was off by 150 years. Today, we realize that to play it properly, one has to understand that he had a dual identity. That he was also an African.

Can superstar Asisat Oshoala help Nigeria win the Women’s World Cup?

The Women’s World Cup starts on Saturday, and Canada is feverish with excitement. In the past week we’ve also been inundated with America’s insistence that they have now saved global soccer (insert self-praising #FIFAgate articles), and that their women’s team must avenge the loss suffered by their male-counterparts in Brazil last year.

The USA are joint pre-tournament favorites with Germany. Brazil are also likely to be strong. Africa is represented by Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria.

The top women’s team in Africa, Nigeria, are coming to this tournament ready to win. The Falconets have qualified for every World Cup. Their talented squad also boasts BBC’s inaugural Female Footballer of the Year award winner, Asisat Oshoala. Oshoala is a 20-year-old forward who plays her club football for Liverpool (check this brilliant recent goal).

The video of Asisat winning, had me in tears. This is an incredible honour and was voted by fans of the beautiful game to a wondrously gifted and deserving player. It’s not often my heart softens towards winners of football awards. Her humility is breathtaking. She is exactly the type of genuine player that the world needs to look to.

Not only is Oshoala one of the youngest players to be names to the squad, but she beat out FIFA’s 2013 Female Player of the Year Nadine Angerer to win the award and is the first African player to play in the FA women’s Super League. She was also the leading scorer at last year’s U20 World Cup. Here’s a video of her pulverizing New Zealand at that tournament (notice she wears the number 4 shirt, like another great Nigerian striker, Nwankwo Kanu, used to back in the day):

Her passion and sense of responsibility are immense and will be all-present as she will help drive the Falconets to World Cup glory in Canada.

“People find it difficult to believe that there are good teams in Africa,” says Oshoala. “We’re not just going there to complete the numbers, we’re going there to make sure people know African teams are not just pushover teams at the World Cup, we’re going there to fight.”

Today the UK Guardian listed Oshoala as the number one player to watch at the World Cup. Here’s their write up:

The first African import to play in England’s Women’s Super League – with Liverpool Ladies – Oshoala has recently been voted the BBC women’s footballer of the year. Last year in Canada she won the player of the tournament and top goalscorer accolades after shining for Nigeria in the world under-20 finals. Oshoala proved a big reason why the Africans reached the final, eventually losing narrowly to Germany. Now a forward, she began her international career in midfield with her Nigeria team-mates dubbing her “the female Seedorf”. Brought up in a Muslim household in Lagos, Oshoala – known as Superzee these days – shocked her parents by dropping out of school in order to pursue a career in professional football. Yet much as her family had hoped she would follow their example in carving successful careers in the gold and fashion industries, Superzee had caught the football bug while watching Liverpool men’s team on television in Lagos as a child.

Nigeria is in Group D and shall face Australia, Sweden and the United States. And they are champions of Africa. I can’t wait to see Oshoala and her teammates in action. I also hope that the NFF continues to support her and help develop the beautiful game for girls. Not only is Asisat the one to watch, she is the one to emulate.

What would a Hillary Clinton win mean for Africa?

When it comes to matters of international justice, Hillary Clinton, Obama’s Secretary of State during his first term and 2016 presidential candidate, has gathered inspiration and insights from a diverse bunch of sources the past few decades. One of them, apparently, is former US security advisor (’69-’75) and secretary of state (‘73-‘77) Henry Kissinger. Guided by similar ideas on the role of US global leadership, Henry offered counsel to Hillary during her term as Secretary of State. We know this because she put it in her book. This is the same Henry who, back in 1976, admitted that “it is quite true that we have not given the same priority to Africa” (compared to, roughly, everything else that qualified as foreign during his term) but who, according to the journalist and author Abayomi Azikiwe, nevertheless managed to suppress national liberation struggles in ways that had a huge “impact on the continued underdevelopment and instability in existence on the African continent.” On top of that, wrote Christopher Hitchens (who saw Kissinger as a “stupendous liar with a remarkable memory”), “Kissinger’s orchestration of political and military and diplomatic cover for apartheid in South Africa presents us with a morally repulsive record and includes the appalling consequences of the destabilization of Angola.”

Of course we don’t know if Africa was, in any shape or form, on Hillary’s mind when she expressed her affection and admiration for Kissinger’s leader and mentor-ship. It doesn’t really matter either. His well-documented track record as an imperial war criminal makes her admiration for him perturbing enough. We do know (well, the journalist Daniel Bates does) that it was in Africa, more specifically South Africa, where she found personal guidance after she, and the rest of the world, found out that her husband and then-President Bill Clinton had cheated on her. She has compared her process of forgiving him with the South African post-apartheid truth and reconciliation process saying “she was inspired by the country’s former leader Nelson Mandela,” writes Bates, “and that she had to act otherwise she would remain in a mental ‘prison’ for the rest of her life.”

The parallel is interesting (if we’re generous), but instructive in her intentions on North-South relations it is not. What bonds Henry, a Republican who held office 40 years ago, and Hillary, a Democrat, is their unwavering belief (well, rhetorically at least) in US imperialism as the healthiest and most virtuous force for global development and progress, an ideal so fierce and proud that it’s immune to the most compelling doses of evidence that have challenged this stance the past decades.

With regards to Africa, one of Hillary’s successes during her role as Secretary of State, took place when she persuaded South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir to sign a peace deal with Sudan. In her eyes, it signaled a victorious achievement. In those of Alex de Waal, a dodgy lie. The affair led him to conclude that “There’s also a lesson for Africa: if Africans do not write their own histories, others will do it on their behalf. Generations of African schoolchildren will grow up believing that America was responsible for South Sudanese independence and other such myths.”

In spite of these ambiguities, Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign has thus far failed to ignite a substantial national conversation on how her presidency may affect the rest of the world, especially the African continent. There may be many reasons for this: American political culture’s insularity or her spin doctors’ fear that the right-wing smearing over Benghazi may flare up again.

In the main, we can expect Clinton, if elected, to reaffirm American exceptionalism. On more than one occasional, she has expressed a firm belief in the “indispensability of continued American leadership in service of a just and liberal order.”

As is well known, since the 1980s the US, UK, the World Bank and the IMF have played decisive roles in the destruction of local African farming and ecosystems, health care systems and other social services through structural adjustment programs, which required governments to liberalize trade, transform agriculture and cut down social spending as conditions for loans. Across the continent, poverty deepened as a result of this neoliberal transformation, taking its greatest toll on women and children, whilst the US and its corporations were cashing in. According to geographer David Harvey, it was Hillary’s husband Bill who consolidated the neoliberal trade order (which Harvey calls the “Wall Street, Treasury, IMF complex”) during his time in the White House.

Interestingly, in her public statements as Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton appeared to break with that consensus. In August 2012, she showcased a stand against neo-colonial relations when she exclaimed that “[t]he days of having outsiders come and extract the wealth of Africa for themselves, leaving nothing or very little behind, should be over in the 21st century.” She also advocated for an exit of “autocratic rulers who care more about preserving their grip on power than promoting the welfare of their citizens.” A year earlier, in 2011, as reported by Pambazuka’s Isaac Odoom, she declared that “When people come to Africa to make investments, we want them to do well but also want them to do good… We don’t want them to undermine good governance in Africa.”

Let’s be clear: it is likely that all this talk was really side eyeing China, who the US see as its rival for African resources and markets. It had little to nothing to do with Africans. At least, that’s what her three tours as former Secretary of State, and her last trip in 2012, suggest.

The main goal of the latter visit, as observed by the Guardian’s David Smith, and by economist Jayati Ghosh, was to persuade African leaders that America’s “commitment to democracy and human rights” made them a far better partner than “rivals” (i.e. China), who only care about resource extraction. The irony however, as Ghosh pointed out is that “US and European companies continue to try to exploit these countries’ resources as much, if not more, not least through land and other resource grabs. “If anything”, Ghosh argues, “their concern now is that competition from Chinese and Indian (and even Brazilian and Malaysian) firms is forcing them to offer better terms for their resource extraction.” Ghosh is worth quoting at length:

In “free trade agreements” signed with developing country partners, the US and the EU regularly demand the opening up of markets, as well as extensive intellectual property rights and investment protection that favour the interests of their own large companies over poor citizens of those countries. Most “technical assistance” aid really funds the northern consultants of the global development industry rather than contributing to economic diversification and knowledge expansion in the south”.

The hypocrisy of her condemnation of Chinese trade ethics and her dogmatic dedication to neoliberal policies is anything but new. Her lashing out at China during her 2011 visit to Lusaka, for example, left Pambazuka’s Isaac Odoom perplexed about her reluctance to apply the same standards to her own country’s investment strategies and foreign assistance priorities. “One is tempted to ask”, Odoom writes, “Is China the only ‘bad guy’ in town? Aren’t some Western actors complicit of the same activities in Africa?”

As early as 2009, when Hillary made her first visit as Secretary of State, (and spoke about “the joy and energy Africans have, evidenced not just by the boogieing, but by the hard work and perseverance,”) skeptics were side-eying her affection for Africa. The tour largely centered around The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), security issues and natural resources. “In all three dimensions”, argues Firoze Manji for Pambazuka,“the focus is on providing guarantees for US corporate interests” at the cost of those of African labor. In addition to that, Some Kenyan politicians were allegedly unhappy about Clinton’s lecturing style and the emptiness of her trade promises, challenging her to improve, rather than just boost, trade with steps such as the reduction of U.S farm subsidies.

So as much as Hillary may talk about “relationship of partnership not patronage”, and of “sustainability, [rather than] quick fixes” and rhetorically commit herself to “a strong foundation to attract new investment”, the creation of “new businesses” and “more paychecks” “within the context of a positive ethic of corporate responsibility”, as she allegedly did in 2011, at the end of the day it’s about feeding the ‘Wall Street, Treasury, IMF complex’.

What Africa can expect from Hillary as President, then, is ever more extraction and exploitation, nicely packaged in the optimistic promise of sustainability, ‘good business climates’, partnership, democracy and ‘change’.

June 4, 2015

Cape Town is Three Countries: Curatorship in times of load shedding

“Load shedding” is a nice South African term for daily deliberate shutdown of electricity supply in parts of the country due to shortage in supply. The following are three short stories from art exhibitions that took place on one week of May in the suburb of Woodstock, Cape Town. Torches and candles provided.

…

1. FRIDAY / GREATMORE STUDIOS

The lights went off almost exactly at 6pm, the hour Khanyisile Mbongwa was about to open her new group exhibition Revisiting The Latent Archive in Sites. No one at Cape Town’s Greatmore Studios looked too worried, not the organizers and not the guests, who were greeting and small-chatting to each other. The previous event they hosted, Monadology music performance, was postponed by two hours while waiting for electricity to come back. The event before that, a screening of a documentary about James Matthews, turned into an open talk with the poet. Three hours after the due time, with the return of the power, the screening started. Curatorship in times of load shedding brings it down to the basics of the reason why we bother to gather. The idea behind a cultural event takes the lead over the form, and improvisation becomes the best strategy. You can’t dwell on technicalities here.

…

The reason we gathered that evening was to have conversations about the affairs of current time and space. In the words of Khanyisile, the exhibition explores the concept of space as a hidden archive that can be awakened and re-imagined through art. To provide a taste of what is to come, guests were welcomed as they entered with an exhibit of a bread box, a powerful sculpture made of rusty bars. Breadwinner by Bronwyn Katz tells the story of the artist’s father, whose life represents the local duo of money and security. “My father, the financial provider of my family, spent a portion of his life working as a welder and specialised in the making of burglar bars and fencing. Breadwinner speaks of the toil that accompanies the provision of basic needs. The concept of access and in-access of basic needs is referenced by the burglar barred lid of the bread bin. The lid of the bread bin is made heavy making it difficult to open the bread bin. This refers to “the difficulty with making a living” writes Katz. This is the new generation of South African artists, many of them freshly graduated from the local art school, and this is what they are talking about.

…

Standard long white candles were installed in line at the feet of the exhibition walls, erecting from empty bottles of Castle beer – a popular solution with unique local aesthetics. The opening performance started on time, and the candle light was perfect for it. The intimate atmosphere contributed to the dramatic dialogue between the two performing poets who approached the dozens of guests with open and direct conversations in English (Nique Floe Sithole) and isiZulu (Palesa Sibiya) about the state of their site-specific affairs.

“I always wanted to exhibit with candle lights, but you know UCT – they are so strict”, said with a smile Richard Mabula, who will be leaving the country soon for the first time. In August he will fly to The Dominican Republic to study further and practice hyper-realist painting. His large scale piece of almost real-size naked young lady lying in a black void seemed to be comfortable with the candle lights. Her eyes were constantly looking back at the exhibition room and at those who look at her, her background dissolving into the wall.

…

Mingling and socializing in semi-dark romantic lighting was a strange experience. The effect on the social behaviour resulted in more attention to the artworks, rather than the faces of the audience members (which steal the show in many opening events). It did provide more opportunities to stand alone and observe the exhibiting room.

‘It makes me feel a bit lost to stand in front of an artwork without a text explanation’ mentioned Khoi, a doctor in training from Nairobi. She stood in front of Rory Emmett’s Lest We Forget work, and started sharing her thoughts about the use of colours on only one of the figures. ‘Maybe it’s better. It makes me think and take whatever I want to take from it”. A lady, who was standing near, started telling us about the news story which inspired those images – a mobile phone footage of a man who got harassed by security in public. She said that it was a big story and that he was stripped to naked, the policemen were punished, the video is online and we must watch it. That gave Khoi an answer to the question of the colours. I preferred the retelling of the story by the artwork, which takes the voyeurism out. A conversation as a great substitute for a label.

…

The exhibition served as an alternative sheet of newspaper, mixing history with future. When the violent event happened doesn’t matter. According to the curatorial thread, now is the right time to talk about witnessing violence; or about money and race, as Bronwyn and Richard do. Or about tradition and culture, as other participating artists show. Those moments or places that the mainstream news do not tell us about until something extraordinary happens, those which we ourselves see through, were the subject of Robyn Pretorius’ wall. Her hyper realistic paintings capture and document the overlooked spots of town and ‘the energies they harbour’ as she says. They carry a familiar feeling of collectively abandoned corners. A couple of visitors were debating if it is Mowbray or Rondebosch subways passage in one of the paintings. To me it looked like Observatory. In the texts provided it said Bellville station. Does the exact geography really matter?

The eye gets used to the weak candle light. People get used to the load shedding reality. It is part of the everyday here. Some keep on bitching about the inconvenience and ill governance, others romanticize it with tweets about book reading in candle lights. Some print out the timetables and put them on the fridge, others don’t bother to check. Khanyisile has no time to bitch or complain, and she is much too critical to romanticize public defects. She works with them, and it seems to work for her.

…

At 9.30pm the lights in Woodstock were turned on, accompanied with vocals of joy. It was almost perfect timing to end the exhibition opening ceremony. I’m not sure if I want to see Richard’s laying girl’s look in the bright white lights.

2. THURSDAY / ARTMODE

Not every cultural event could turn a three hour power shutdown into a positive twist. It is hard to imagine what would do in the same situation the curators of ArtMode, an exhibition event that happened the same time a day before on the other side of Woodstock, the emerging art district of downtown Cape Town.

Forget about intimacy and politically charged spaces, about tightly conceptualized curatorship of a group exhibition, forget about candle lights. ArtMode looked and felt more like an expo, a mega Indaba of artistic stalls or corners. Like in a retail space – though an exclusive and cool one – the message was variety, without a thematic thread or conversations between the participating exhibits.

The concept was to have the artists present and working as a part of the exhibition – the increasingly popular ‘Live Art’ genre. Some took it literally and installed a stand with canvas and set down painting while answering questions. Alice Angela Toich was the most classic of them. She looked like a painting herself: wearing a black gown with paint stains, dark shiny hair with her back to the crowd and her face towards a classic composition of still life – dramatic fabrics, deep and dark colours and a vase of Protea flowers. Brighter and lighter version of a live artist was Samantha Appolles’ vision of wishful joy. She exhibited colourful portraits of beautiful confident individuals, young people who own their identity: “my efforts are to break racial stigmas and long-standing oppressive dogmas by using a positive vision of a more expressive human race”. They are imagined, she tells. Imagined poster boys and girls for the born free generation? As opposed to the portrait of omnipresent Nelson Mandela on an opposite wall, the faces on Samantha’s canvas and their spirit felt refreshing and very much real.

The talk of the exhibition was Maurice Mbikayi – who took the notion of live art to another level, while sending the most clearly political content. He creates sculptures of bags and dresses from reused electronic waste, such as computer keyboards and cables, and wears his artworks. Creating spectacle from the unwanted. He provides his audience more opportunities to take photographs with the works, to use their phone cameras before they end up in the same piles as the old PC parts. Like the Fight-Club film heroes, he re-sells the waste to those who over consume. And he makes a Disney World experience out of it.

…

Jan Ludik’s corner of the exhibition space looked like a deserted living room in Sea Point. With no artist present and a few pieces of domestic furniture that might have been left there from the previous life of this space as an expansive interior design franchise. From a distance the works on the walls looked like vintage oil paintings of landscapes from the antique shop next door, heavy framed with stripes of gold. A closer look would reveal details too contemporary and ordinary for the genre – views of Sea Point, the well-off suburb on the other side of Signal Hill. It is those ‘classic’ houses one would typically find the original old-school landscape paintings that Jan references. In the renovated gentrified hangar they looked dislocated — a feeling that was highlighted by hanging them side by side with abstract conceptual works. Both the technique and the themes were contrasting. Ready-made work of screws referencing the Marikana killing of protesting miners wouldn’t naturally fit into the conversations of that conservative regulated and depoliticized space. Nor the cubist drawing of a washing line, which is a prohibited exhibit on the streets of Sea Point. A hint to a living contradiction?

…

An act that would benefit from intimate candle lights was The Morning Pages performance. The day before their gig in another local venue was cancelled due to an expected load shedding. The Southern suburbs based band has been around for two years, experimenting with creating audio-visual settings that carry the audience into a spiritual journey. The shop that hired out the projector for them to use on that day for the visual part, has refused to refund the money. Their name is borrowed from a term referencing an in-between state of being in the first moments of one’s awakening from sleep into awareness. Their feeling of séance, familiar from house jams and small spaces like Tagore’s Observatory, struggled to work with the bright lights in the corners around and the spaciousness of the hangar. It was hard to concentrate and tune into their frequency, like trying to have a deep philosophic conversation in a mall.

…

The ‘creative live collaboration of art and music’ was actually held in a mall – The Palms complex in Woodstock. Behind a car parking entrance hides an indoor world that looks like an outside world, but cleaner and safer. In a huge, industrial and beautiful hangar floats a private-public space. The Palms is a home to exclusive services, such as ‘dial-a-surprise’ online gift shop, fabric and vintage decor and destination-management tourist bureau. The designers of the space try to make it look like an outside street with paved floors, inner balconies, a bridge and elements that copy the old English style of street signs and lamps. They even have features that the city outside doesn’t have, such as benches. In the land of The Palms there is no poverty, no street people sleeping in corners, no one asking for coins, no litter like nik-nak empty bags flying in the notorious Woodstock wind. There is no wind at all actually, which makes it funny to see one of the shops putting a sign on the door ‘closed on account of weather’. And there are no palms. It is a wishful, clean, rich and sterile world guarded from the outside by contract security men. Shops leave stuff outside of the closed doors, no one will take them. One shop has a sign offering ‘load shedding sale’, promising discounts in times of power failure. Khanyisile is not the only one rolling with the electrical punches.

…

3. SATURDAY / GOODMAN GALLERY

The safest way to go about load shedding is to do a morning event. On the same weekend Woodstock hosted another exhibition opening, a curated show by a returning Capetonian Natasha Becker. After more than a decade in the academic and art worlds of United States, Natasha comes back to live and work in Cape Town for a while, celebrating the move with an exhibition. Under the title Speaking Back she curated a collection of stories, told by female artists as her homecoming entourage. Most of the African participants’ biographies reveal an opposite direction of movement – from various places of birth in Africa to new places of life and work in the US and Europe. “Born in Cairo, lives and works in New York…born in Johannesburg, lives and works in Berlin… born in Kenya, lives in London..”. Becker’s return to Cape Town is an exceptional step among her colleagues’ stories of life. A new trendsetter?

…

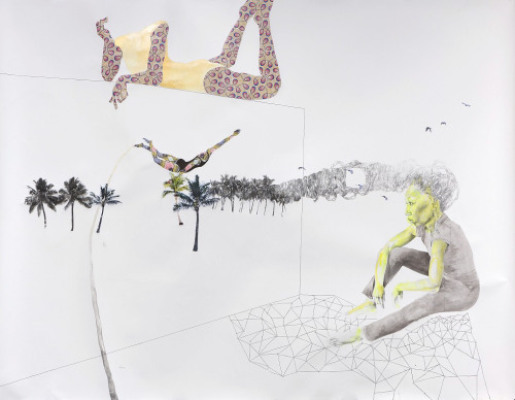

via The Goodman Gallery

Many of the stories in the exhibition were of the fantasy genre, combining wild childish imagination with deep political awareness. One of Natasha’s critical fairies was ruby onyinyechi amanze (”born in Nigeria and is based in New York”). She exhibited two big sheets of paper, so big that you can imagine the artist sitting on one, drawing and trying not to leave a mark of her knees. Her techniques are mixed and carry playfulness – grey pencil, yellow marker, glitter and pasted cut-outs combined. The sheets look like drafts, unfinished, not serious. Isn’t criticism supposed to be serious and bitter? ruby’s psychedelic fantasy – with headless, disproportional dream-like creatures – seems to have too much fun for a critical text.

…

The playful, futuristic, sharp, critical and imaginary discourse was projected also from the works of Otobang Nkanga (”born in Nigeria and living in Belgium”). Nkanga’s artist book featured childish and unfinished cropped out figures of sexual harassment and small houses wrapped in wire; body-less hands in mines and factories. Otobang creates pages that make social critique look like fun. If I would dare to speak back that Saturday morning, I would grab the plastic dildo that hang Adejoke Tugbiyele in the entrance, and use it as a microphone to ask if I may leaf through the book’s colourful pages, which lay casually on the table, suggesting a touch is allowed. Adejoke (”American artist and activist of Nigerian descent”), might have supported my mini protest. Along with the dildo she exhibited a dozen of imaginary demonstrations, mixing real slogans with tale-like figures and situations in drawings of pink lines. They presented a cool futuristic-journalistic essay, that can even look cute.

via The Goodman Gallery

The spirit of playfulness was not contagious – I haven’t seen anyone touch the artworks, and I did not dare myself. Goodman Gallery, which hosted the exhibition, is one of the biggest names in commercial contemporary art scene of South Africa. With this status comes a feeling of almost a museum, ‘respectful’ institution with less freedom for a guest, as implied in the custom restrictions such as ‘don’t touch’ or ‘don’t photograph’. Otobang did have a hint of suggestion to touch, and yet the behaviour in such spaces is completely self-policed, and is mainly based on the fear of social shame.

via The Goodman Gallery

Most of the exhibition stories could have been from out of space, or at least out of the ordinary. There was a universal feel about the exhibition. The space could have easily been sent by a magic technology to New York. As far as its’ locality concerns it could fit into any black consciousness town in the world. The most Capetonian work would be Arlene Wandera’s I’ve Always Wanted a Doll’s House – a small model of a Victorian architecture house that could have been in Woodstock. Amorphic black figures of un-personalized humans climbing-in through the windows, as if invading. The house is looking cute and hunted, repainted white with its paint dripping down. Funny enough it was placed in a dark corner of the gallery, by a beautiful video art projection (of Ellen Gallagher). At the corners of the dark doll house were placed two torches, suggesting for the audience to light inside into the inner rooms. Another test of audience playfulness or a site-specific joke on load shedding?

*This post appeared originally on the author’s Yalla Shoola tumblr page. All photos are by the author unless otherwise noted.

The NBA comes to Africa: Interview with the NBA’s man in Africa, Amadou Gallo Fall

Today is game 1 of the NBA Finals between the Golden State Warriors, and the Cleveland Cavaliers. On August 1, the NBA will play its first game in Africa. The venue will be the Ellis Park Arena in Johannesburg, South Africa. This is significant given, as NBA.com reminded us last, at least “35 players from Africa have played in the NBA since hall of famer and two-time NBA Champion Hakeem Olajuwon was drafted in 1984.” Though the NBA has hosted events on the continent since 1993—coaching camps, outreach programs (NBA Cares has built 38 places to live, learn or play on the continent) — this is the first time they host an event of this magnitude on the continent.

The game on August 1 is an exhibition and will feature a Team Africa vs. Team World. “Team Africa will be comprised of players from Africa and second generation African players, and Team World will be comprised of players from the rest of the world.” Chris Paul of the Los Angeles Clippers will captain Team World and Luol Deng is designated captain of Team Africa. The proceeds will go to the Boys & Girls Clubs of South Africa, SOS Children’s Villages Association of South Africa and the Nelson Mandela Foundation. Amadou Fall, the NBA vice-president and managing director for Africa has been based in Johannesburg, South Africa since May 2010. Prior to that, he spent 12 years with the Dallas Mavericks working as director of player personnel and vice-president of international affairs. Some of you may also have recognized Fall from the film “Elevate.” I caught up with Fall at his office in Johannesburg to discuss basketball on the continent and a bunch of other things: his favorite films and Reggae music.

What’s the most unexpected thing you have ever done?

I managed a Reggae band called Midnite.

How did that come about?

They asked me (laughs). I was probably their number one fan. This was in Washington D.C just after I graduated. I realized very quickly that the music industry wasn’t for me. I lasted one gig (laughs). But you should check them out. They became legends.

I was reading an article about Luol Deng and his journey to the NBA. You are also mentioned in that story. When you look at the NBA now, what is different in terms of African presence in the NBA, either on the court or behind the scenes?

I think there has been a steady growth. The history between the NBA and Africa dates way back from Hakeem, No. 1 overall pick in 1984

To Manute Bol

To Dikembe

All these guys playing their role really in paving the way for a generation of young very talented super committed players who already are following in their footprints. Obviously Luol, who has made two All-Star appearances as you mentioned is one of them.

When I was in Dallas, I remember the year he was in the draft, we were considering him. It came down to him and another player, we ended up taking the other player and I remember Luol calling me (smiling) and saying, “hey man you guys are going to regret it.” And till this day he always has unbelievable games against the Mavs. In fact, after the trade his best game with Miami was in Dallas, and he put up big numbers (smiles).

Seeing Serge Ibaka

Seeing Luc Mbah a Moute

There is a lot of pride.

One of the things that touched me at the All-Star Game was the homage Victor Oladipo paid to Hakeem Olajuwon. How did that make you feel?

It meant a great deal. Hakeem is a great ambassador for our game around the world. He has influenced a whole generation of players and has had a big impact on the game.

In January, when the NBA hosted a game in London at O2 Arena, Milwaukee Bucks vs. The New York Knicks, Hakeem was there. I remember, at the Reception at the US Ambassador’s in London, seeing Giannis Antetokounmpo talking to Hakeem, getting advice from him. Giannis is unbelievably talented, Victor obviously also has a very bright future. Both those guys have very deep roots in Nigeria. The conversation is always about how they can go back and continue to inspire the next generation.

What was the greatest part of working in Dallas?

Working with great people. I got to Dallas in ’98 and I was very fortunate to be part of the journey that brought the team to elite status. I was given an opportunity and being recognized for having an eye for talent and really being given a platform to participate in building a team. So gradually we brought in some great players to join Dirk.

And then seeing a team develop, with a great coach in Donnie Nelson, the leadership of Mark Cuban after he bought the team, and of course Avery Johnson.

What was your favorite Mavs team?

The 2003 team. Those guys really had swag. Our toughest guys were 6’2. Talented, confident, (we) lost in the playoffs because Dirk got hurt.

What was your best collegiate game?

In college I hit a buzzer beater. (Laughs) When I see the guys hitting buzzer beaters and running around, it’s good to know I have had that feeling. That was probably my first time attempting a three pointer.

What are some of your favorite basketball films?

He Got Game. Because of Ray Allen. I was impressed. You don’t realize that these guys are multi-talented. He is known as a three-point specialist and here he is in a leading role. I have a lot of respect for people who act.

I loved Coach Carter and Hoosiers. I liked Hoop Dreams

Let’s talk about Basketball Without Borders. What makes you proud about that program?

Our league has a long standing commitment to leadership in social responsibility. Basketball Without Borders is our flagship basketball development program and community outreach. There have been eight players from BWB Africa who made it into the League. I think the program is something we look forward to every year and this year it is even more special. This is going to be the 13th year in Africa and we are going to close it out with a historic game in Johannesburg. The first NBA Game on the continent. It will be a show for the ages.

June 3, 2015

The War Story We Need Right Now

American media (and Western media in general) like their “bridge” characters; basically placing a mostly white Westerner at the center of any narrative, especially of conflict, that happen somewhere else. It’s best illustrated in the journalism of Nicholas Kristof (read him apply it or watch him explain it; or check here a good critique of this method). It’s also Hollywood’s favorite method to tell us stories to make sense of America’s place in the world, especially about the “War on Terror. In the latter case, the most recent exhibit is American Sniper, directed by Clint Eastwood.

The prevailing narrative of films like American Sniper that of chest-thumping in jingoism and silence when it comes to the victims of American expansionism. And there are always other sources. For example, Laura Poitras’ My Country, My Country is a film about the American occupation as it affected ordinary Iraqis. Further, Kaizer Matsumunyane’s The Smiling Pirate is a necessary counter to the Tom Hanks-led Captain Phillips. Unsurprisingly, these films did not receive the same PR campaign as Eastwood’s film did, but it is on us as viewers to choose what we watch and what we praise in hopes that Hollwood will listen.

Which brings me to Guantanamo Diary by the Mauritanian Mohamedou Ould Slahi; the kind of war story we need right now. Weaving personal anecdotes with brief and cutting analyses of the ways in which war and crisis change human behavior, Slahi’s story is a chronicle of human struggle and will to survive in the face of terror and torture. More importantly, it is a story of those most affected by the so-called Global War on Terror. Stolen from his home of Mauritania, Slahi is representative of so many Muslims from the Middle East and North Africa who have been harassed, tortured, or killed just because of their religion and place of birth. Have we forgotten that GITMO still exists just because Obama tried and failed to close the prison?

Written in the summer of 2005, Slahi’s diary is a 372-page account of his first three years of detainment (most of it in isolation) in the American prison on the tip of Cuba. Slahi’s memoir begins with his initial return from Canada to Mauritania in early 2000. After short stints in Senegalese and Mauritanian prisons, he returns to his life in Nouakchott. In November 2001, however, after driving his own car to the police station for questioning, he is rendered to Jordan, Afghanistan, and, finally, Guantanamo Bay in August 2002. The diary also provides details (as much as possible, given the heavy redactions made) of his torture in prison. He was questioned repetitively about the 1999 Millennium Plot and his flimsy associations with certain Al Quaeda members. Starting in 2003 he was subjected to a Donald Rumsfeld-approved “special interrogation plan” that included a wide array of torture methods, including sleep and sensory deprivation along with physical and sexual abuse.

With time, torture broke Slahi, but not in the way that his interrogators had hoped: he tells them exactly what they want to hear, even though he writes in his diary that it is false, in hopes that a confession will stop the inhumane treatment. However, a 2009 habeas corpus petition from the ACLU and Slahi’s own legal team resulted in a judge ruling in 2010 that Slahi should be released, due to lack of evidence. An appeal by the Obama administration has delayed his release, however. While his legal battle continues, we are left with his words. Since the diary’s release in January 2015, it has become a New York Times bestseller, received numerous mostly positive and passionate reviews, and been the source of events like this one in London. It is no surprise Hollywood hasn’t turned Slahi’s story into a film.

It is encouraging that a book as honest as Guantanamo Diary has achieved so much recognition and acclaim. Now, it is time for mainstream America to reject the Kristof-style bridge stories and focus its sights on stories that tell real, full truths.

June 2, 2015

The Afro-Anarchist’s Guide to Kendrick Lamar’s ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’

You’ve recently resigned yourself to the fact that at a certain point in a rapper’s career, usually when he/she is already steering the yacht of mainstream success after having surmounted the crab-infested grime of the underground, they must decide whether or not to submit to the allure of pop-cultural relevance, or stick to their creative instincts, and create on their own terms. So, you start asking yourself if Kendrick is being ironic when he wonders ‘How Much a Dollar Cost?’

If you are a Compton native with Dr. Dre’s blessings like Kendrick, wouldn’t you want to decipher Wesley’s Theory with one to whom West Coast Hip-Hop owes much of its earlier sound? Wouldn’t you want George Clinton, the funk master himself right there as you channel James Brown? Wouldn’t you ride alongside Snoop in a ’64 drop top, and laugh at how ‘every nigga is a star’ on the nightly news?

In fact, you are feeling ‘alright’ because last night, you bombed an Exxon gas station with a red “Fuck Pigs!” tag, yet you still find yourself ‘screaming in a hotel room’ as you are bombarded with news of Oscar Grant, the Bay Area, Trayvon Martin, Florida, Michael Brown, Fergusson, Jordan Davis, Staten Isalnd and Eric Garner. News of acquittals, “I can’t breathes,” and banners of #BlackLivesMatter.

Between tears, you might even start wondering what would happen if ‘these walls could talk,’ and you heard you were the ‘realest Negus alive.’

In this era of trigger-happy cops and Super PACS, crown yourself ‘King Kunta’, and banish Toby from memory because the fact is ‘from Compton to Congress’ there’s already ‘a new gang in town’, and everyone’s talking about ‘who dis?’ and ‘who dat?’

Let Bilal sing you away to tomorrow’s wet dreams, but remember ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’ is just another declassified chapter from the post-millennial ‘Hood Politics’ files. But shit, ‘ain’t nothin’ new but a flu of new DemoCrips and ReBloodlicans.’ Baptize yourself like Kendrick, after all the Grammys is a heist.

Resurrect Du Bois. Resurrect Garvey. Resurrect Mandela. Then declare; ‘I’m African American, I’m African/I’m black as the moon, heritage of a small village/Pardon my residence. Screaming across ‘These Walls’ that separate us, swim across the Black Atlantic to the Cape Coast with a water proof iPod. Kendrick says he came to his senses at 16 years old. When did you?

Finally, tell the world that Pac said, ‘the ground is gonna open up and swallow the evil,’ and that ‘ground is the symbol for the poor people.’ But never forget what ‘momma said’ about not lying ‘to kick it, my nigga.’

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers