Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 343

June 2, 2015

Confessions of three humanitarians

There are days we’d sacrifice our colleagues/morals/integrity to avoid trawling through BS on the Internet. But we couldn’t avoid comment on an article called “Confessions of a humanitarian” that The UK Guardian ran last week.

As three people who have been involved in different forms of development and social justice work, it’s so refreshing to see the plight of aid workers who travel too much finally get Guardian-endorsed publication! It’s been a long time — many air-miles, dare we say? — coming.

After all, this is why the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funds the Guardian’s Development site – to cover the burning development issues of our time. We know first hand, as the pseudonym Dara Passano articulates, that the stress of travel can really get you down. Just ask all those migrants who’ve been traveling on boats, in truck beds and on foot with nary a hot shower in sight.

Even more impressive is the article’s brilliant recitation of classic development tropes. There’s the gritty volunteer work — living by starlight, on a first-name basis with parasites and on a steady diet of iodine tablets — the gold star of ‘first-hand knowledge’ to solve hunger, forge world peace and knock a couple of goals off that ever growing list of SDGs. (We’ve all put that ‘volunteer experience’ on our CVs and ended up at NGOs, landing jobs with much longer and fancier-sounding titles. There’s no shame in that, Dara – we’ve got to give our colonies of parasites something to feed on and we need some poignant photos for our Tinder profiles.)

Transitioning from volunteering — all the good intentions and zeal to change the world — to NGO bureaucracy can be very difficult indeed. Dearest Dara, between the queuing in Economy, and the crumpled clothes and disheveled hair resulting from gallivanting around the world to make things better for ‘The People’, it’s understandable you’re feeling a bit down. Tossing around all that privilege can make anyone question their commitment to and understanding of social justice (or whatever got you into this dirty business in the first place).

It’s no wonder you went from side-eyeing the UN for abusing its privilege and wasting financial resources on business class flights, and then secretly coveting becoming part of the UN. This must be what one calls getting corrupted by the system. If only our budget lines allowed ‘Nespresso machines’, as you recommend, we’d never end up with an ineffective tangle of aid actors and such burn out among humanitarian workers.

But back to your original problem – needing UN employment — allow us to offer a little advice. The next time you’re about to throw yourself at the feet of another buff and perfectly manicured UN employee with your CV, remember, those applications are all online now. We can guarantee that there’s no free Wi-Fi in the economy boarding area, and some first-class traveller is about to press submit whilst sipping on a lungo macchiato and having a foot massage. Yes, Dear Dara — the vicious cycle keeping you from your dreams is more perpetuating than the poverty of even the poorest village.

June 1, 2015

Africa is a Country teams up with Coffebeans Routes to present a Cape Town concert series.

This month we will be kicking off a special partnership with Coffeebeans Routes to bring you a concert live from Cape Town on the last Thursday of every month.

This concert series is a celebration of Coffeebeans Routes 10th year of existence. The organization is a cultural tourism company that just received an award for their dedication to “engaging people and culture” in the Cape Town region. Says founder and creative director Iain Harris: “We would like to share with the city and the world some of the best examples of music performance and composition that Cape Town has to offer.” Read more about the organization’s history, and their intimate connection to the Cape Town music landscape on their blog.

The first concert will be Thursday June, 25th 2015, and it will feature Loit Sols in collaboration Churchil Naude. It’s a fascinating partnership between Loit, a goema rymklets folk singer, and Churchil an Afrikaans hip hop artist. The show comes on the tails of Churchil’s debut album release on 24 May, Kroeskop vol Geraas, and their studio collaboration on the Wasgoedlyn project.

If you’re Cape Town you can join the festivities live. But if not, you can also just tune in here at Africa is a Country where we will be live streaming each concert.

And look out for deeper profiles on all the participating artists here on Africa is a Country.

May 29, 2015

Germany’s Rhodes Must Fall

In 1967, West Germany had its own #RhodesMustFall moment. In September of that year, socialist students tore down the monuments to colonial leaders Hans Dominik and Hermann von Wißmann that stood in front of their university. One statue was carried across the street, propped up in the cafeteria, painted red, and hung with a collection box for protesters’ legal fees. A leftist magazine had predicted the moment five years earlier. A photomontage in konkret magazine showed a black hand with a saw digging its teeth into the statue’s plinth. The text of the article read: “Word is getting around. Old Europe is no longer the center of the world.”

Black and white hands collaborated to dismantle the legacies of colonialism in 1960s West Germany. One of the first political issues the previously apathetic white German students turned to was South Africa, rallying around their fellow student Neville Alexander, who had completed a Ph.D in German literature when he returned to political struggle in South Africa after the 1961 Sharpeville Massacre. His opposition to apartheid earned him a decade in Robben Island prison. German students raised over 40,000 deutsche marks for his legal fees and carried signs through West Berlin reading “He Who Supports Apartheid Sanctions Auschwitz.”

Neville Alexander

It was not hard to find supporters of apartheid in post-fascist Germany. Among their most vocal was an economist who is hailed as one of the intellectual fathers of the West German social market economy, Wilhelm Röpke. In 1964, foreign students gathered in protest when Röpke came to the University of Zurich to give a talk titled “South Africa: An Attempt at a Positive Appraisal.”

Röpke’s talk was openly racist. He said that full equality was impossible because “the South African Negro is not only a man of an utterly different race but, at the same time, stems from a completely different type and level of civilization.” Equality for the black population, he said, would mean “national suicide.” He felt that South Africa must remain a white stronghold, calling for “a Zambezi line” to “divide the black-controlled northern part of the continent from the white-controlled south.” For reasons of racial superiority, economics and Realpolitik, Röpke felt that white supremacy had to persist in South Africa. The South African government loved his analysis. They ordered twenty thousand off-prints of the pamphlet for distribution in the U.S., three further translations and sixteen thousand copies of the book in which it was to appear.

In histories of the 1960s, the Congolese, Sudanese, South African, Ethiopian and Angolan protesters who were part of the West German and Swiss student movement are largely absent. Yet Röpke is routinely praised in history books and newspapers, with barely a mention of his racism. He even has a statue of his own. Not to give anyone any ideas.

Osekre on the trials and tribulations of being an African musician in New York City

I wish I received a heads up by friends in the real world about the reality of being a musician in New York City. It is no joke! I had decided to pursue music full time, some time in 2010. I had just graduated from Columbia University, and I saw this as my time to break away from certain kinds of responsibilities, expectations and deadlines set by college, my family, my friends, and the burden of “being a migrant in Rome.” I just wanted to pause, to live, and breathe easier. The only thing on my agenda was to get my band, Osekre and The Lucky Bastards going once again.

At the time, I was inspired by an increased interest in African music in New York in general. Columbia alumni, Vampire Weekend, were heroes on campus, and had sparked debates in the world and indie music communities with their song “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa” as they fused what they felt were soukous licks with indie sounds. The spirit of Fela Kuti’s work was being reinvigorated in the underground music spaces, where DJs and hip hop artists were finally spinning and sampling Afrobeat. K’naan was making waves with incredibly poignant stories through rap, wit and lyricism; introducing the world to the struggles of Somalis on his album Dusty foot Philosopher. Nneka had released her song “Kangpe”, which was all over EA Sports’ FIFA soccer games, and was about to debut on Letterman in New York. I had enough sources and stories to keep me motivated about the opportunities and possibilities for young African cats doing their music thing in NYC. What no one explained was exactly how much work that was going to involve and what it meant to start from the scratch, or scratch the start.

It was after an exciting consultation with a lady friend, who was well entrenched in the NYC music scene, that I decided to move to Brooklyn. Exactly where in Brooklyn, she didn’t specify. Her recommendations after listening to my tracks were pretty clear: “Move to Brooklyn, Brooklyn will appreciate your sound more. Reach out to Todd P, Brice,” and a couple of other big promoters. It took years for me to finally connect with these promoters or even get emails returned.

I moved to Crown Heights, where I lived in an amazing co-op with some of the most ultra-liberal friends I was going to make in NYC! One of my housemates had a beehive on the roof where he collected honey, we also had a backyard where we reared chickens and supplied eggs to the rest of the house. Well, the non-vegetarians in the house. Amidst the exciting monthly house parties, and my new found passion for biking and roaming Brooklyn.

During the next three years I would find myself bouncing from couch to couch in friends’ houses and music studios in Brooklyn. I felt like my Ivy league degree meant little in this context. I observed, listened, practiced, worked, and gradually shifted back and forth between various music scenes, trying to find a home for my sound. However, I barely got the opportunity to play outside of the McKibbin loft open mic series.

As iron sharpened iron, I started writing songs that were a reflection of my Ghanaian roots and music experiences in Bushwick. My basic guitar playing improved in an intense, musically competitive atmosphere. During my movements in and around these scenes, I noticed a few things, I was often the only African, and sometimes the only black kid at some of these gigs, and was often asked about why my band was mostly American or white. (This is why the rise of the “Afropunk” community is important. Although, I fear Afropunk as a platform is losing that core Afropunk artist, then again, there is only so much Afropunk can do to appease an incredibly wide, diverse and complex demographic and audience.) Most often I had to explain how no African parent will allow their kid to graduate from college with the clear objective of being in a band as the next focus of their lives. There is a “continent to be helped, friends school fees to be paid, businesses to return home to build etc. It seemed the life of an artist is a privilege that only wealthy or more privileged kids were allowed. Was I privileged? Not at all.

Frustrated from not being able to prove to promoters that booking my band would always guarantee a glorious dance party, I gave up on finding a home for my sound outside of the McKibbin Loft scene. However, my budget was catching up to the demands of the scene where we mostly played for free pizza and some beer, or just for a good time. My live shows were getting a bit more intense. Music was certainly my only outlet and somehow, with the passing of a year, and the relative lack of progression of my band into bigger venues, I turned my sound up a bit.

Out of all these experiences, several events shaped my outlook on the various music scenes in New York, and that significantly influenced the direction of my future projects. First off, I started booking shows and paired myself with bands that I felt made sense for my band to play with. I used factors outside of genre to determine which pairings made sense: energy, influences and message. Out of my success in booking shows I created the Aputumpu platform, which attracted some seed-funding last year to improve the quality of my programming.

Second, I realized the there were very few opportunities for artists of color to showcase their work, to be discovered, heard or given an opportunity to succeed in most of the existing scenes. The world music community isn’t really into young African acts either. The older, more established, and even sometimes forgotten legends seem to make more sense to their tastes.

So when Meridian 23 offered my band a summer residency this year, I decided to set-up a platform that would allow more artists, especially people of color a space to show off their talents, connect, and amplify the reach of our work, cultures, ideas, and experiences. There will be talks, live bands, and DJs holding down a dance party. I call it Afropolitans, a word that I am aware is problematic, however it remains useful in its ability to carve out space in a cultural scene where we still lack representation.

So, if you’re in New York at all this summer, check out Afropolitan Presents. It kicks off today (Friday May 29th) at 8pm at Meridian23, with a sliding-scale entrance fee based on the time you show up. (It’s free before 9:30 for all the struggling artists out there!) See you out there!

May 28, 2015

HIFA in the time of Xenophobia

The sky is just catching its first glimpses of daylight when I hand the cab driver most of the US dollar notes I have left. The notes are a stained, worn and flimsy mess that I am glad to be rid of. I take stock of my shabbiness before entering the Harare International Airport building, and realize that I look no better than the notes I just palmed off to the cab driver.

My sneakers have gathered considerable mileage and dust in the last few days that I’ve been at the Harare International Festival of the Arts (HIFA), my face is still caked with a sleep I hadn’t had the night before, and my breathe smells like the whiskey that kept me up.

While the uniformed man at the Air Zimbabwe check-in desk captures my details, I mumble something about the shame I feel at handing over a South African passport. I spare him the direct brunt of my breathe for this banter, but I make it clear that I do feel the almost necessary shame.

My shame at being South African in Zimbabwe is something that I had grappled with at first and then become comfortable with towards the end of my journey. Two weeks prior to my departure for Zimbabwe, South Africans had attacked foreigners living in South Africa and looted the shops that some of them owned. Like its predecessor in 2008, this second outbreak of violence had caused a number of fatalities and injuries. On fatality had even been bandied on the front page of a widely read newspaper. Some of the victims had inevitably been Zimbabwean.

At first I had not been sure how to take the banter from young Zimbabweans at the festival when they referred to what my country folk had done to theirs. It had been an uncomfortable topic for me to speak openly about, in a country where I as the South African was the minority instead of the other way around. Perhaps because of the exclusive nature of arts festivals, I had come across Zimbabweans who understood the problem at a sophisticated level and did not blame every South African for the attacks. But most did agree with my sentiment that it was the responsibility of every South African to make sure that this kind of thing never happened again on South African soil.

What was most saddening is the fact that even with the situation as it was, many of the Zimbabwean people I spoke to accepted the situation as it was: many Zimbabweans had no choice but to live and work in South Africa and they would have to continue this existence with or without the welcome and hospitality of all South Africans.

Once the man at check-in has captured my details and tagged my bag, he points me to counter where I needed to pay an additional $50 for my trip. He points with a smile on his face. I panic at not having that kind of money at hand after a festival that had already stripped my bank account to its skimpy under garments. I forget my breathe and try to explain my situation. “There is nothing I can do” he says.

I rehash the same explanation at the counter he has directed me to. The bored-looking clerk behind a glass panel says “If you don’t have the money, you are not getting on that flight.” I curse Air Zimbabwe out loud and continue to curse them for the next few days for not telling me and other passengers about the additional fees put in place after their disagreement with the Civil Aviation Authority of Zimbabwe (CAAZ).

Realising the futility of my vitriol, I search the lobby for someone I might recognize. Two poets from Botswana say that they too are cash strapped and hope that their South African Airways flight doesn’t carry this levy. I approach a Black woman in a striped black and white dress and sandals. I explain my situation, by now forgetting that my breathe smells like hades on garbage collection day. “Ask my husband, he is sitting there” she points to a stock man in a striped green white and khaki shirt sitting opposite a young man in track pants and a hoodie.

I don’t get a chance to finish my explanation before Mr. Maramwidze instructs his son to give me the $100 that he has, and tells me to bring back the change. I pay the departure fee with tears in my eyes and struggle to compose myself when I return to thank the him, his family and his country. Later his Mrs. Maramwidze, who had been standing in a queue for him, brushes away my offer to send the money back to him. “Be kind to somebody else” she says, and walks out of the airport building.

Images from the Harare International Festival of the Arts courtesy of the author:

Angolan Cinemas: Past and Present Tense

The photo that graces the cover of Angola Cinemas by Walter Fernandes and Miguel Hurst (a new coffee table book on Angola’s cinema spaces published by Goethe-Institut and edited by Christiane Schulte, Gabriele Stiller-Kern, and Miguel Hurst), says it all: futurist, modernist, unfinished, and abandoned. This is the state of so much in Angola… or had been until the war ended in 2002 and the oil boom hit. Angola’s redevelopment and reconstruction has been the subject of both gooey Africa-rising praise and stinging jeremiads. Angola has witnessed lots of construction. But cultural spaces, and historical patrimony in general, have not fared so well.

Angola Cinemas brings a fresh focus to the historic spaces of film viewing. Angola is not known for being a center of film production currently nor in the past but by 1975 there were 50 theatres. Now largely moribund, a handful are being revived. Brief entries by Maria Alice Correia & F. João Guimarães and by Paula Nascimento (all architects), center on the distinct architectural elements of Angolan cinemas: the cine-esplanda (open-air cinemas) and the late colonial tropical modernist architecture that shaped cinemas and urban space more generally in Angola (and other Portuguese colonies). They look at the key social role of the cinema in people’s lives and as a space for a diverse set of arts: theatre, film, and music. Nascimento argues for preservation based not just on the physical space but on that cultural dynamism: “Restoring them means not only recovering their architectural forms, but equally their functional forms: it is important to establish a dialectic between the future and the past among their new users.” (21)

With nearly 160 color plates, this is a beautiful book. You get a sense of the spaces: their faded glory, the unfulfilled potential, of the event waiting to happen. But this book isn’t just pretty. It’s a cry to act. It’s unfinished business. Not just because some of the cinemas were never finished and never opened (like the stunning Cine Estúdio on the book’s cover or the Cinema Infante Sagres, said to be the largest cinema on the continent in 1975), but because the book marks the beginning of a collective research project on these theatres that asks for public participation via their website. Here too we see the ambitions of a larger, continent wide project.

What’s missing from the book is the social buzz and energy of filled space. Given what the architects and editors’ entries tell us, as well as what the annexed information in the back of the book relates, how best to represent the rich world of cinema going? Some of these cinemas are operational so it must have been possible to take some photos of Cine Atlântico packed to the gills during the Luanda International Film Festival or the Cine Cazenga, renovated for the film Assaltos em Luanda II in 2008, to give us a sense of cinema in the musseques. The contrast of a lively showing would have been equally as sobering as the garbage and dust thick interiors.

Of course, sometimes absences are presences. Like the missing photo of the Cinema Restauração, the largest functioning cinema in the late colonial period and now the Parliament since independence. I suppose ‘security’ concerns meant it couldn’t be photographed but the absence of the photo and the silence around it are telling. They speak to the narrow confines in which the project operates: both political power and economic muscle reside largely with members of the MPLA (whose images, symbols, and colors appear in some of the photos to make clear that cinema spaces are more frequently used for convening political commissions than cultural publics). But the absence of cinematic space will never be a present. What José Mena Abrantes said of Angolan film is true of cinemas as well, their “past deserves a better present.” (“Cinema Angolano: Um Passado a Merecer Melhore Presente,” Lisboa: Cinemateca Portuguesa, 1987)

Why am I insulted when people mistake me for a samba dancer?

Let me give you some snippets of what it is like to be black in Brazil: A few months ago Ana*, a well-to-do, Afro-Brazilian friend of mine, dressed in head-to-toe perfection, was asked to go into the service entrance of her (white) friend’s apartment building (yes, residential buildings in Brazil have separate service entrances for the exclusive use of housekeepers, gardeners, plumbers etc.). She was livid and spewed her wrath at the doorman, insisting that she be shown the regular entrance.

“We are seen as the maids, or the maids’ children”, Gisela declared, during happy hour at a boteco (our local term for ‘bar’ in Brazil) in Itaim Bibi, a pretty yuppy neighborhood in São Paulo. This was her explanation of what we were experiencing, the fact that not a single guy in the bar (they were mostly white), was looking at us. In their minds, she explained, we are pretty invisible as we are black and therefore poor and undesirable. “They don’t even see us,” she declared.

Diana, a White Paulistana of Lebanese and German heritage, is married to Hank, an Afro-Brazilian. Often, Diane tells me the cops pull them over (they own an SUV). One goes around to Hank in the driver seat, demanding in the usual cop-like menacing tone, for his papers. The other goes around to Diane’s side, the passenger seat, and asks her, unbeknownst to Hank, if she is ok. They assume that she is being car jacked.

A pretty well-to-do black friend in Rio, went to open a bank account, and the guards basically stopped him and would not let him even take the four steps from the revolving doors to the reception area. They kept asking him, menacingly, what he was doing there — thank God one of the bank managers lives in his apartment building, and had seen him there, so she had to yell to the guards to leave him alone.

Vanessa Barbara, a White Brazilian journalist, has stated that there is denial over racism in Brazil. Clearly perturbed by this, she wrote in the New York Times last month that when she applied the ‘neck test’ in an ice cream store (the neck test works like this: go to any establishment, stick your neck up and see how many black people you can see), she counted one black person. She wasn’t convinced he was Brazilian either (presumably he spoke English and therefore probably wasn’t).

—–

The above will surprise many, but they are but a fraction of the true life stories that have been recounted to me, poignantly illustrating that racial prejudice in Brazil is alive and well. What is surprising to me, three years after living in Brazil, is that Brazil is seemingly oblivious to this reality. Friends from the world over, France, South Africa, Kenya, India, Singapore, are often very shocked when I explain to them this reality.

Doesn’t it go without saying that any country in the world that experienced slavery still suffers from the bitter after taste of this forced subjugation of African people? Shouldn’t we expect this from Brazil? After all, Latin America received the largest number of slaves in the 1800s, with Brazil benefiting from the lion’s share. In addition, Brazil was last of the countries in the Americas to abolish slavery in 1888.

Why should we be surprised that racism exists in Brazil?

I have a few explanations, which, partly triggered by the vignettes above (and I have a whole load more), have been marinating in my mind over the past 3 years living in Brazil. I may modify some of my musings over time as I continue to ponder over stories I hear, read more, understand the country I live in and talk to more Brazilians.

From the outside, Brazil seems to be a rainbow nation with glorious tones of caramel, cappuccino, café au lait, mocha – the blond person with afro-like hair; the chocolatey toned person with blue yes. These are the images we see. Brazilians are warm, fun-loving people who love life and seem so carefree. Samba, carnival, beer, those beautiful women, frequent kisses of affection. Fun, relaxed, all getting along. Somehow, we believe that this is all that there is to being Brazilian. To acknowledge that something as negative as racism exists seems so, well, un-Brazilian. Not at all like the images that we have seen.

White Brazilians whom I have asked about racism say ‘it is not like in America’ as a part answer to my ‘do you think Brazil is racist’ question… Unfortunately they are in denial, as was the case in the recent scandalous shooting in Rio of a 15-year old and a 19-year old by cops. It was a clear case of white cop shoots black teenage boy for no good reason. The explanation the cop gave, something to the tune of ‘I thought they were doing something wrong’ is intrinsically racist of course. In a nutshell, North America dominates the story of race in these parts – easy for Brazil to get away with just not saying anything about this issue. The truth is that the highly flagrant race-motivated attacks in North America are happening here.

We acknowledge the shock of poverty in Brazil, clashing desperately against the wealth. Some of us has seen the abysmal poverty that a significant portion of the country lives in, in the favelas portrayed in the famous film, “City of God”. The fact is that more than 70% of the most poor of Brazilians are black; and most black people are poor, so the two issues are inextricably linked. Could it be the race problem is hiding (thriving?) in the layers of the poverty problem? Most White Brazilians that I have spoken to accept that their country is classist and prejudiced against the poor; in doing so, they are implicitly addressing race, in my view.

Poor and rich do not mix here, and there are layers of class norms, unspoken rules and behaviours, that over time, have become set in stone in the society. I say this because in my neighbourhood, the black people are the maids, watchmen and dog walkers. This is jarringly uncomfortable to me as I have never lived in a city where black people were so visibly downtrodden. Even having black waiters in restaurants in the nice neighbourhoods is a recent phenomenon– they used to be kept hidden behind in the kitchen. Since this has always been the case, then this is what people, particularly white people, accept as normal.

For me, this cannot be normal. If I see brown hued people buying groceries or going to the gym in Georgetown in Washington, D.C, or Maida Vale in London, or Sandton in South Africa, I should be able to see them in Jardins, Sao Paulo or Ipanema, Rio. If White Brazilians do not see Afro-Brazilians enjoying the offerings of a nice neighbourhood in a metropolitan city, or if they don’t think they belong there, surely they, or their cities, are prejudiced?

When we reflect on who is writing about Brazil, and who is producing TV shows and movies, we realize that the key movers and shakers are not of the brown skinned hues. So if you have not experienced disparaging remarks while shopping in a high-end store, you probably cannot write about this in a way that is authentic. President Dilma’s cabinet of approximately 40 Ministers has only one black one, can you imagine, just one! On TV, black people are mostly maids and drivers, or the like and in my first two years in Brazil none of the mainstream magazines featured an Afro-Brazilian woman on the cover. (For the record, two men are featured frequently, Pele, as well as Barbosa, a brilliant and prolific judge who served as Supreme Court Judge from 2012-2014). Another reason why the black reality in Brazil is an invisible one, therefore, is that they don’t have spokespeople representing their realities.

My close White Brazilian friends in Brazil do not deny that racism exists — highly educated and well-travelled, their exposure has open their minds to the reality that persists. One of my dearest White Brazilian friends, Gigi, warned me years ago when we both lived in Johannesburg. ‘My country is prejudiced,’ she told me. And when she returned to Brazil, she said that she found herself wondering ‘where are all the black people?’ I see these friends take steps to educate their families and their children, live in more inclusive ways, learn more about the manifestations of prejudice, and openly have conversations about it. This needs to happen on a much bigger scale.

Yes, Brazil is the warm and contagious people, the beautiful metissage that happens when Africans, Europeans, Indigenous people mix, the beat of Samba, the potent caipirinha, the architecture of Niemeyer, the magic of Neymar, the addictive sweetness of acai. But, it is also prejudiced, and the more we talk about it, the more we can understand it and the more something can be done about it. In three years, I have seen some changes, albeit small ones– a non maid black character in a major telenovela, an Afro-Brazilian on the cover of a major magazine, more waiters serving at fancy restaurants. But I need to read more about Afro-Brazilians, hear more of their stories, see them portraying diverse characters in TV programmes, see more of them in the corporate offices I work in and hear, from the lips of Brazilians of all hues, that yes, racisms exists in this beautiful country.

PS: Despite my frustrations that there is little acknowledgement of, or discussion about, racism in Brazil, I continue to love living there. I am often asked if I am a samba dancer instead of a business executive while in flight (despite my corporate attire). In many white people’s biased minds and experience, the highest level of success a Black Brazilian woman can reach, is to be dancer, model, actress. I sometimes receive gawking stares while I enjoy a meal at one of my favourite restaurants, and pay for it myself. For the most part, people know I am not Brazilian-they think I am American, and treat me exceedingly better than they need to. Perhaps because in their minds, Americans are rich. And, as class rules here, rich people are treated nicely.

*Names have been changed throughout this article.

Political Violence: The cloud looming over Lesotho

Last week in Lesotho, opposition leaders Tom Thabane and Thesele ‘Maseribane fled to Botswana and South Africa, again seeking protection from SADC against what they said were assassination attempts by the Lesotho Defense Force. As Lesotho under Prime Minister Mosisili continues its pattern of political crisis, it begs the question just where political violence is rooted in a country often described as “homogenous.”

First, it should be noted, that despite all the high-political machinations and high-profile assassinations over the past 9 months, everyday life in Lesotho has not been greatly affected. These are the squabbles of the political elite. Where everyday Basotho are affected is in the absence: The absence of strong government policy on HIV/AIDS; The absence of fresh proposals to bolster popular programs like the old-age pension scheme; The absence of a plan to get security forces to stop shooting at each other.

Why are politicians and top security leaders seemingly always at each other’s throats? Surely it has to do with the poverty of the country and the outsized influence that comes with controlling appointments to the civil service — one of the largest employers in the country.

On another level, however, perhaps it is better to look to South Africa and the machinations of the ANC as a model for what is happening in Lesotho. Periodically over the last decade or more, the ANC has gone through a round of internal purges, often somewhat opaque to outsiders, but certainly a distraction from governing. The ever-present splintering of political parties in Lesotho and the internal machinations in the Lesotho Defense Force resemble nothing so much as the inner circle of the ANC: A small ruling elite maneuvering for control of the levers of power seemingly not answerable to the populace.

The 1980s and 1990s were the period during which most of Lesotho’s current leaders cut their chops. The military commanders were coming up through the ranks in an institution that had close ties both to the ANC-in-exile in Maseru and the South African security forces. Similarly, the current politicians came of age in a fractured and factional BCP that had to operate partially underground, partially in exile, and partially in collaboration with the non-elected BNP and military-run governments.

Lesotho in the 1980s was not a place where respect for the rule of law came first. The lessons learned by today’s leaders in that generative moment seem to be still fueling an environment where soldiers threaten judges on the bench, and where no charges are ever filed in conjunction with public violence on the eve of national elections.

In recent days, civil society in Lesotho has been more outspoken about the climate of violence and impunity, but threats remain, especially to journalists. Will aid cuts or diplomatic pressure bring a solution?

While these sorts of gestures are better than nothing, what Lesotho needs is fundamental political reform, a respect for the rule of law, and, perhaps, a fundamental rethink of the forms of democracy in the Mountain Kingdom so that not only can Basotho “Kena ka Khotso” (Come in Peace), as the border gates say, but “Lula ka khotso” (Stay in Peace).

May 27, 2015

Kassav, and Jozi’s love for zouk

Kassav are a band formed in Paris in ’79. They were in Johannesburg recently, where they played to a capacity audience at the Bassline in Newtown. I attended the show without having heard their music prior. Neither was I familiar with how they looked, save for the posters which started going up on lamp posts some two weeks before their show. It was exactly how I preferred it!

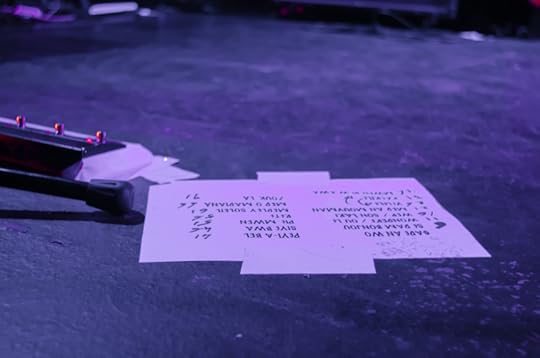

The set list

The band had just finished their first set when I arrived, and had taken a break. This presented an opportunity to ask a few people their impressions on first set. The people I spoke to stuck to short and punchy, ecstatically-delivered phrases, possibly because they were still trying to digest what they’d just experienced. The feedback was affirmative overall.

The minister of Home Affairs, Malusi Gigaba

It was the weekend following the week of attacks against black people from other African countries. Mainstream media outlets had had a productive week, ceasing every passing moment and using it to broadcast their pornography of violence. The protagonist in this saga: A black man, portrayed this time around as an angry, panga-wielding, war-ready overlord, capable of bringing terror to big cities, mid-size ghettoes and small towns. The minister of Home Affairs, Malusi Gigaba, opened the second half of Kassav’s set with a message assuring Africans from elsewhere on the continent and those based in the diaspora that “South Africa is your home.”

The audience listened intently to the minister, cheering him on with every punchline in his speech. “[The government says] so because [it] knows the role that African played toward the liberation of this country,” continued the minister to more cheers. “And so we say away with xenophobia! Away with Afrophobia! South Africa is your home, enjoy it!”

Kassav Live @ Bassline

The first few beats into the second set threw me back to my radio-obsessed childhood in Maseru where our national broadcaster had a show dedicated to the finest Zouk tunes around. It was capably-hosted by Treaty Makoae-Mosese, the late, larger-than-life empress of Lesotho’s entertainment scene. She was cool as a bird’s wings when they flap. She made listening to Radio Lesotho on a Saturday at 12pm while waiting for lunch to get served fun as hell! She was rocking print fabric and schooling an entire nation about different African music scenes before it was stylish to do so.

As flag-bearers of Compas/Kompa and grand innovators of Zouk, Kassav provided a live and direct passageway for me to connect to that time. It wasn’t only visceral, it transcended. The music, it was powerful!

The band have roots in Lesser Antilles regions of Guadeloupe and Martinique, and its members have lived in Senegal, France and elsewhere. Their music is just as unbounded; founding members experimented with genres ranging from rock to disco before settling for Kassav’s Zouk sound and releasing their first album, Love and Kadance. Pictured above is Jacob Desvarieux. He was working as a studio musician when Pierre-Edouard Décimus approached him with the vision for Kassav.

Jocelyne Béroard

Though founded in Paris, Kassav are very much a Carribean group. Jocelyne Béroard and Jean-Philippe Marthély shared main vocal duties during the night, each playing off of each other’s strengths like friends who’ve spent enough time bouncing ideas around and getting to appreciate each others’ qualities; and are gracious enough to let the other shine at any given moment. Jean-Philippe joined Kassav in 1981 on Kassav n°3; he is known, through his solo work, and the “inventor of Zouk love (links to French website).” Other members in the band have solo projects on the side. Jocelyne, for instance, is regarded as the first Carribean woman to release a gold-certified album. Kassav seems to be the mothership of sorts; a launchpad for alternative worlds and imaginations.

It was open groove season from the moment the band got on stage. No one really stopped dancing, save for a brief moment to take a selfie or three with friends. The message was love, overall; it was enacted through gyrating hips, endless sing-along’s, and clapping of hands, and shouts and screams for more. More. More!

The Venice Biennale and the problem of nationalism

At the heart of the 56th Venice Biennale, curated under the banner “All the World’s Futures” by Okwui Enwenzor, is a critique of the nationalism inherent to the Venice Biennale, and the role of nationalism in art history. While this critique of the nation state is not explicitly stated, it is clear that the curator aims to challenge the Biennale’s art history through highlighting what he calls a ‘contemporary global reality’. Yet Enwezor says nothing of the political affiliations of the biennale, or the ways in which artists have reflected their national governments and institutions over the years. In the curator’s vernacular, the exhibition’s goal is to show the ‘state of things’. It is important to note that this exhibition fails to achieve this ambition.

Viewers of the exhibition, who are informed of the ‘state of things’ via world media, see no reflection of the current dramas of the globe such as the migration crisis in Europe and South-East Asia, for example. Italy, the home of the biennale, turns away Libyan asylum seekers; we know of the thousands who have drowned in the Mediterranean trying to get to safety. And it is not only the countries of Europe who have been callous towards human lives; Thailand, also, turns away Burmese asylum-seekers who are stranded at sea.

To be in the luxury of Venice, looking at the finest art in the world, is to realize the aloofness of an art world patronized by national governments, instead of challenging the very idea of the nation through art. The selection of ‘political art’ with no clear anti-national agenda, reveals the uncertainty in the curator’s position on nationalism or their place within this year’s biennale structure, and the deeply flawed nature of state-owned exhibitions. It is pretentious to claim this exhibition as a critique of the biennale tradition when nothing outrightly speaks against the involvement of government institutions, or the making of Venice a site of nationalist pride.

In his statement, the curator says, “In 2015, la Biennale di Venezia will employ the historical trajectory of the Biennale itself (…) the core of the project is the notion of the exhibition as stage where historical and counter-historical projects will be explored.” Again, the attention to history here is only in writing: the exhibition doesn’t engage the biennale’s problematic history as the home of Fascist propaganda from 1928 to 1942; nor that between art and politics in the 1930s collaboration of performance artist F. T. Marinetti, the founder of Italian Futurism, and Benito Mussolini, the head of the National Fascist Party. A defense of this history, or its rebuttal is absent in the exhibition. What is most successful about this exhibition is it’s masterful attention to form, and how objects are united by their spatial relationship. This is the use of the stage as a platform to produce theatrical effects through dramatic changes in artistic form and in other parts of the exhibition, its synthesis. By playing around with presenting forms that blend into one another, the curator succeeds at holding the attention of the viewer. However, this dramatic technique which relies on spatial relationships between art objects, requires a large body of artworks, hence the massive selection of 140 artworks in total. It produces the effect of a long unbreaking experience inside space, like that of listening to a Gustav Mahler symphony.

It is by no coincidence that the first artwork encountered in the exhibition uses sculptural form to draw comments on the state of empire. As you enter the Giardini in Venice, the historical site of the Biennale, you meet a park of all-white sculptures five times human size, and towering above the ground. Coronation Park (2015), by the Indian Raqs Media Collective refers to the 19th century period in British India, specifically. The white sculptures stood out prominently in the garden, posing in strange configurations: some were absent of a torso, standing beside the pedestal and reading the plaque, defaced, without arms and other limbs, or missing heads, reminding me of a particular kind of anarchist vandalism. This visual drama in the garden threshold, provided reflection on the national or imperial politics attached to the monuments in the garden, such as the bust of Richard Wagner, also standing in the garden. In light of today’s war in Syria, and Iraq, these anarchistic sculptures brought to mind the Youtube picture of ISIS destroying ancient sculptures in the Mosul Mosque in Iraq, or the student protest in University of Cape Town in South Africa called #RhodesMustFall that took down the statue of British colonial officer Cecil Rhodes. Though the act of taking down sculptures appears on a global scale, the politics within this act differs from event to event. Again, the lack of a definite position on nationalist politics, even in this case leaves a viewer confused about the generalized politics under the globalism umbrella.

RAQS MEDIA COLLECTIVE (Monica Narula, Jeebesh Bagchi, Shuddhabrata Sengupta) “Coronation Park”, Biennale Venedig 2015

Another form of anarchist vandalism took the form of an installation covering the title of the main international pavilion. Artist Glenn Ligon used neon lights to draw the words: blues blood bruise. Immersed in this theatre, I was rudely interrupted by a blue and white e-flux billboard. On this display the writer and editor Boris Groys wrote: “There is no progress in art. Art does not wait for a better society in the future to come–it immortalizes here and now.” This version of the future was a peripatetic turn. Recalling the goal of the exhibition to describe the state of things; to analyse the self in the global age, this peripatetic turn made it next to impossible to see how such a goal could be achieved through this selection of artworks. If art were to immortalize here and now, where was the migrant crisis reflected here in the exhibition space, and the thousands stranded at sea, denied entry into Italy or Thailand? Which ‘state of things’ ignores this obvious fact? In this sense, time was elusive in the exhibition. I kept pondering the title All the World’s Futures. Did it refer to any specific time in the future? And which specific world was being referred to here? This lack of specificity made any sign of time in the exhibition only a small and insignificant event in this massive symphony.

While the curator aimed for challenging the nationalist structure of the Biennale, it was harder to digest the artists’ perspective on our past. The juxtaposition of the artists’ voices within this utopian space seemed inconsistent, especially because the critique of nation seemed out of place in a location that was so luxuriously and unabashedly centred around celebrating the fruits of nation and nationalism – within the protective envelope of late capitalism. As Ernesto Laclau reminds us, “Politics and space are antinomic terms. Politics only exists insofar as the spatial eludes us.” The space of art as a theatre of the mind is not innocent of its responsibility towards artwork. I felt the catch-all nature of the exhibition, as well as its lack of a concise political theme, took away from any important signification of time, particularly the present, within itself.

This peripatetic turn of events brought to mind tensions between artist and curator. What was the show really about? Who was it really representing? These questions led me to the inquiry on the biennale as a space by the artist-curator Ahmet Ogut who asks: “Are Biennales about providing a space, or becoming a space?” By using the terms “providing” and “becoming”, Ogut fractures space into two: one for artistic use, and another for institutional registration. This tension exists where time is generated through anti-imperialist or anti-nationalist discourse within the artwork which drowns in an unblemished exhibition space. When walking from one end of the Arsenale to the other, I felt so at ease that when I finally saw Italian sculptor Monica Bonvinci’s “Latent Combustion #1, #2, #3”, a composition of chain-saws hanging from above covered in black poly-urethane, I thought only for a moment of the violence implied, then imagined the work on a high fashion runway in Milan, where the fashion models and market would glamorize its violence.

As a tourist city, Venice wreaks of glamor and superficial gloss. Honeymooning couples often role play in the la gondolas floating about the canals of the Venice districts. Piazza San Marco on a Summer’s day such as during the opening of the biennale floods with thousands of tourists, some just coming off the Titanic-sized cruise ships that dock in the lagoon. These tourists are fodder for biennale ticket sales. In 2009, the 54th Venice biennale received over 2000 visitors each day, and more than 300,000 in the entire period of its running.

However, Venice is clearly not immune to less romantic realities of global environmental damage and the long term effects of changing weather patterns. The flooding in Venice has increased considerably, which happens during winter. The city has recently flooded up to 130 cm, according to The Telegraph UK. The newspaper shows Venetians wearing fishing gear and wading through the floods on normal work days. An ambulance team wheels a man on a bench above floods. A group of tourists in raincoats and fishing gear roam around Piazza San Marco taking photographs. The site specificity of Venice coupled with a concern for the future of human life – given shifting water tables and threat by water, making precarious the existence of many now-habitable spaces – inspired several artists.

John Akomfrah produced a 3 channel film titled Vertigo Sea (2015) that dealt with the relationship of humanity to the sea. In gripping archival footage, the shipwrecks of the past: images of wailing mothers, and survivors, and the violent images of whaling, became a clear reflection of the here and the now. This echoed the migration issues facing global politics, and the images of man’s relationship to nature brought the future into sharp focus, resonating deeply with the current state of things, as well as our inability to grasp these real forms of temporality in the past and present.

Vincent J. F. Huang, the solo artist of the Tuwala Pavilion produced the installation “Crossing the Tide”, a surreal work set in a future in which land disappears underwater. Baths are filled with water and illuminated from below. One has to walk across a wooden plank inserted above the baths, making an undeniable link between environmental threats to cities that depend on bodies of water for commerce and trade, and are yet beholden to the ocean’s instability. It was the suggestion of a complete disappearance of land under water that created a visceral encounter with the post-national future. I imagined the post-human of this time: perhaps akin to the gilled post-humans of the 1995 scifi film Waterworld, starring Kevin Costner.

Similarly, the Mexican pavilion, Possessing Nature, featured the duo Tania Candiani and Luis Felope Ortega, both of whom drew comparisons between Mexico city and Venice – both of which are aquatic cities. The installation was a projection of the interchanging images of Venice and Mexico over a rippling pool of water. Likewise, Charles Lim focused on the future of sea and land in Singapore–in the exhibition Sea State–whose interest in the proximity of his country to the Pacific Ocean triggered a performative process of submerging a massive metallic object into the sea, removing it after six months, and installing it in the gallery space. This reproduction of aquatic life of barnacles and shellfish onto land and inside the biennale was an innovation of form. The surreal nature of this manufacturing of a future in which objects below the sea are installed on land, became a poetic meditation on the activities of a Sea State that functions on, in, and under water. It replicated this poetic interplay between sea and land, a metaphor for matters of labor, capital, and nation.

This interplay between labor, capital, and state also activated the 100 m. long coal sacs installation by Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama titled Out of Bounds. Its sheer length span the entire side of the Arsenale exhibition, a strange and dominating form: a temporality of a particular kind of present which is also the future. Perhaps it spoke about labor rising to the heights of power: a reflection on the growing middle class in Africa, and their increasing dominance of the state. As I walked through this colossus, I heard jazz improvisation coming from inside the Arsenale building. As an art form that thrives in the present tense, jazz is not restricted by geographical borders, languages, or cultures. The music being played was a pre-recorded work automatically playing-back on a programmed piano roll of an upright piano by a Black South African jazz pianist, Nduduzo Makhathini. Even though this was not happening in the here and now, I was consoled by the potential of jazz to liberate the self. Makhathini, who believes in music’s power to change people, reminded me of the words by South African critic Bloke Modisane. In speaking about the resilience of the human spirit he said of life in Sophiatown: “We made the desert bloom; made alterations, converted half-verandas into kitchens, decorated the houses and filled them with music.”

The spirit of anarchy was evident in the live political actions that took place in Venice such as the occupation of the Peggy Guggenheim museum along the Grand Canal winding through the central districts of Venice and into the lagoon. The live reading of Das Kapital by Karl Marx, organized by Enwenzor, were central to how the audience experienced the exhibition space – even if they came in on luxury yachts, and even if they were there protected by the kind of wealth that allowed them to buy artworks here, surely, a part of them found it disconcerting to hear Marx’s seminal words describing the suffering that made their acquisitions and aloofness from suffering possible. In this sense, the live actions formed a lot of intrigue as they contained a direct theatricality and liveness within the moment.

What this exhibition does – and partly why many reviewers and critics are peddling around the issue of its “dark tone” – is create a new way of looking at the self in the global age when the mythology buttressing the nation state is being undermined. It is important to distinguish between the artists and curator for the simple reason that space dictates politics, and not vice versa. Following Ernesto Laclau’s statement, “Society is unrepresentable … any space is an attempt at constituting a society, not to state what it is,” Okwui Enwezor’s “All the World’s Futures” is a radical attempt at shifting the paradigms of biennale models to create a more democratic society of artists and exhibition spaces.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers