Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 346

May 16, 2015

Talking China in Africa at the PEN World Voices Festival in New York

Literary festivals are usually a disappointment. Even when a cherished writer is speaking, the chances are you’d be better off spending an hour simply reading their work rather than going along to watch in person as they try to navigate another stilted panel discussion. But sometimes a debate breaks out that is worth tuning in to.

Last week was the in New York, and this year the “country focus” was on this blog’s number one favourite country of all: Africa. This was very much in keeping with the widely accepted notion that Africa is “having a moment” on the Western literary and cultural scene.

These days, the American audiences at such events tend to be reasonably civil and well-behaved. We have learned “How To Write About Africa” and we understand “The Dangers of a Single Story” and we realize we must avoid participating in “The White-Savior-Industrial Complex” and we’re determined to be better than all that.

And yet, in one of the Q&As, some guy in the audience asked Yvonne Owuor, Alain Mabanckou and Adéwálé Àjàdí to account for ways in which the “voice of the village” came through in their work, while congratulating the three on the long-awaited emergence of “African voices.”

Yvonne Owuor: “The voices have always been there. The West is only taking interest in it now because China is interested in Africa. That’s the reality. We were never interesting until we improved China’s economy. And our books are selling. That’s why we’re here. Nobody’s doing anybody a favour.”

There was strictly no China on the PEN World Voices menu for Africa, yet here it was once again intruding upon proceedings, just as it had earlier in the week when Achille Mbembe engaged in a broad-ranging debate with Aminatta Forna, Boubacar Boris Diop,Lola Shoneyin and Billy Kahora.

In Mbembe’s opening provocation, he responded to the recent xenophobic attacks in South Africa by saying: “I do not believe that any African is a foreigner in Africa, notwithstanding our national boundaries. Nor should any person of African descent [be considered a foreigner], or anybody else — African or not — who is willing to tie his or her fate to ours. That is why, for instance, I fully support the current wave of Chinese immigration in our cities. One big thing that has happened in the continent of late is that each and every single major African city has its Chinese quarters. We are told that in 20 years time we will have somewhere between 2 million and 2.5 million Chinese immigrants to the continent, and I think that is a very good thing.”

Both Lola Shoneyin and Boubacar Boris Diop quarreled with Mbembe on this point, arguing that they had yet to see evidence of much in the way of integration or cultural exchange. Diop also turned the question around and pointed out that there is, in fact, “a scramble for China,” and there was no reason why Africa should be any different in seeking Chinese investment.

But the provincialism of the New Yorkers soon showed through. In the Q&A, it became clear that Mbembe had said the wrong thing. If China was to be discussed at all, the Americans wanted to hear confirmation from the African writers of what they already felt with complete conviction: that China is the bad empire.

Achille Mbembe wasn’t going to tell them anything of the kind.

“The only way we’ll make sure that we don’t have 700 of our young people being buried in the Mediterranean is by opening the continent to itself. The only people right now who are willing to lend money to African nations to build the required infrastructure — airports, harbours, highways — are the Chinese. The World Bank will not give money. The USA will not lend the money. Europe will not lend the money. The Chinese will lend the money. So we’ll take that money. We’ll take it and we’ll build the infrastructure that’s needed. If the price to pay for that is that China sends it workers and ask them to live in compounds where they don’t interact with us, then so be it.”

“But let me tell you one thing. Not all of them live in compounds. You go to Douala, the capital city of Cameroon. They are in the informal sector! Some of them are speaking pidgin. So something is going on, we have to see it in the long term. We have to re-introduce a historical perspective to begin to judge with some clarity a lot of processes that seem confusing. We need to educate our people, for instance. China provides 10,000 fellowships every single year to African countries. You know what it takes to go and study in China? They give you a visa application on one page. One single page! Try to do that with France, Italy, or the USA, and come back, and then we’ll discuss. They want to train 100,000 Africans in the next ten years. Among the student population in China, Africans constituted 3% ten years ago. Today, it’s 8.7%. This is not colonialism. Or if it is, it must be colonialism of a special kind.”

The whole discussion is here, watch from 1.18 to see Aminatta Forna, Diop, and Mbembe responding to the question of China.

May 15, 2015

Goodbye B.B. King. Here he is playing live in Kinshasa, then Zaire, 1974

Hamba kahle, B.B. King (1925-2015)

Vice News and the war against Boko Haram

If you love violence and video games, watch the recent Vice News report, “The War against Boko Haram” posted on Youtube right before Nigeria’s recent elections. It features reporter Kaj Larsen (“the only journalist on the frontline”), embedded with the 103rd battalion of the Nigerian army as it tries to end a six-month stalemate with Boko Haram.

Initially posted in 3 parts, Vice News later posted the whole 29 minute report online:

I hesitate to call it a documentary because the main lesson you’ll learn is that the Nigerian army likes to kill Boko Haram followers. But you’d have learned that in one image, which passes fleetingly over the screen: the body of Boko Haram founder Muhammad Yusuf, riddled from torture and abuse, pink flesh exposed.

Boko Haram has committed terrible atrocities. As both Muslim and Christian Nigerians say to Larsen, “They are devils.” But the Nigerian army has also committed its fair share. Larsen points out shot-out villages, depopulated by the Boko Haram insurgency and the campaign against them, he says explicitly. Against the backdrop of heavy criticisms of the Nigerian army’s slow and ineffectual response to Boko Haram, this show basically bludgeons viewers into choosing a side.

On the one hand, we have Abubakar Shekau’s maniacal laughter and disgusting rhetoric about Boko Haram’s right to steal girls and women. On the other, Vice News features a Nigerian soldier brandishing his commando knife and gleefully saying, “I slaughter them.” Another talks about fucking Boko Haram in the ass. When a soldier tells Larsen that the military had killed over 1000 Boko Haram fighters in the place where they stood, Larsen answers: “That’s incredible.”

Private Jeremiah Friday, who trains hard to fight easy, says relations between Nigerian Muslims and Christians are good. They watch each other pray. “We are all good, brothers, all friends, buddy buddy,” he says. The problem in the North, as Vice lays out, is the lack of “natural resources” (oil); it thus became a playground for radical preachers and violent insurgents. So all the Nigerian army needs to do is bring in some new toys—or are these old? We see a Cold War-era Russian-made Mi-24 HIND attack helicopter that can fire 4,000 rounds a minute. Larsen also notes the “time-honored African conflict tradition—use of private military contractors” (ahem, did the Americans really take this out of the African playbook?) but doesn’t elaborate, even though we know many of these hired hands are South African mercenaries. There is only a gesture to Nigerien and Chadian troops. As a tribute to the Nigerian army, it would be embarrassing to mention its failures until now and the timing of its apparent successes (the Nigerian army upped its offensive against Boko Haram after outgoing President Goodluck Jonathan, facing electoral defeat, ramped up its assault on Boko Haram).

Larsen admits that the solution is not so simple. But the show isn’t about that. It’s not really about Nigeria, and it’s not for Nigerians. Nigerians’ proper names, place names, and Hausa translations are butchered (no, Elijah and Alhaji are not the same). Rather it’s a story, popular in America, about brave soldiers fighting terrorists. And viewers should feel sympathy with the Nigerian soldiers drinking what could be their last beer and feel lonely when Larsen does. But must we either be with them or against them?

The old is dying and the young ones have just been born

Your role in the revolution will not save you. Your history of speech-making and sleeping in a cold detention cell will not save you. Not even back-breaking labour on Robben Island will spare you the scepticism of today’s champions of freedom.

Gramsci tells us “the old is dying and the new cannot be born.” But in my country the young ones have been born. They have been born and they are just now beginning to walk. So this is an interregnum, one in which the new is emerging and there is bitter-sweet hope.

These young ones who have just been born do not respect authority simply because the rules say they should. The young ones simply have no fucks left to give. They do not care about preserving the credibility of those who assert themselves on the basis of what they have done in the past or who they once were. Only today matters because what has gone before has been so bitterly disappointing.

This is the price that must be paid for revolutions betrayed and for forgiveness squandered.

The young ones will laugh you out of town if you think that authority comes from speaking in an authoritative voice. They will call you out on your hypocrisy when you pull out your credentials. They will not be afraid to laugh at you simply because you once did things for which they should be grateful.

In my country, the sun is setting on today and yesterday’s kindness is dissipating.

In other countries too there are changes. In Burundi Nkurunziza attempted to seek a third term and the women said no. In Burkina the impossible happened: Sankara’s killer has fled and something new might be made. In Nigeria, Goodluck and Patience were sent packing. In Kenya Uhuru’s time will soon come. In South Africa a young man wags his finger in Zuma’s face in parliament and tells him that he has lost control of his country.

It is not a mistake that the young ones refuse to use the honorific of ‘President’ when these men have none of the authority that matters. Elections – even free and democratic ones – are no longer a reason for the young ones to respect the old. This is heresy I know but it must be said because the young ones are prowling the streets in search of demons to slay and cows to slaughter. They find them everywhere they look.

Not all protest is righteous of course. In North Africa change was superficial because the old forces were too strong and the new ones did not see that everything – not just the faces and the fists – had to become new. In Bujumbura today there is gunfire and so we shall see.

These aborted revolutions come as no surprise: Changing a ruler without challenging the very basis of his authority is not good enough. The world itself is old enough now to have learned this and the young ones are born knowing it.

Some leaders are clad in frustration and anger. They speak a language that roars like a lion and they have gifts of eloquence and passion. In my country there is just such a young man. His name is Julius. They are dangerous because they seem as though they represent something new and just-born but in fact they will simply replace the old with their own version of the same. The young ones know that challenging those in power while still being impressed by that power will only take them back to the past.

The young ones who are impatient with the ways of yesterday and today have no time for equivocation. They are not interested in those who parse their words and calibrate and operate within the logics of inherited and inherent authority. Apartheid was sustained because ‘good’ men sought to reason with what was patently unreasonable and unequivocally wrong. Dictators stay in power because intellectuals find ways to justify their existence. Heavy words like ‘power vacuum,’ justify the authority of those in power. The young ones know that this must stop.

The young ones have grown up under so-called democracies and so they know that the rules of this dispensation are subject to manipulation. Too few people vote, especially those who are angry. The better devil is the one you know and so your vote is already a compromise. Because, because, because of all of this, the young ones have no fucks left to give and democracy does not legitimise the old ones who have squandered the good will of the young.

The keepers of authority are not just politicians; they are also media mavens and captains of industry, academics and the heads of well-fed NGOs. Those with authority are almost always people with ‘long-standing records.’ They are introduced to rapt audiences as ‘having been around forever.’ They derive their authority from ‘experience.’ Not all of these people are bad and experience itself is not bad but experience is also not the only thing. It used to count for a lot and now we must ask what kind of experience is necessary as we navigate a moment that we will look back on perhaps as having been important. The days of automatic authority are ending.

In my country there is an interregnum and if we connect the dots perhaps we can see that there is one in yours as well. Perhaps for you too it is one in which the young are finding their feet and will soon hit their stride.

In South Africa, in the shadow of national debates about the place and status of John Cecil Rhodes, the old defenders of the status quo are fearful. If Rhodes – who has stood for a century – can be torn down, then what of their own mortal legacies? This fear is both in the hearts of black politicians whose pigs die starving on their farms and white scions of industry who exercise ‘social corporate responsibility’ while dodging their taxes. There are no free rides anymore.

Across class lines and across geographies, there is a fresh and bruising defiance brewing. In my country the young ones think the ruling party representatives who quell protests with promises are a joke. They think the main opposition which stands for ‘free enterprise,’ is a joke. They think that white liberals who question their intellect while pretending not to are a joke. The rich are a joke. Poverty is a joke. Everything is a joke and yet nothing is funny. It is all very serious. LOL.

Maybe in your country this is also happening. Maybe in your country too, old men stand comfortably in front of audiences wearing looks that say, ‘I belong here,’ when in truth they don’t anymore. Where I am from a new identity is coming into being and the old ones are being told to their faces that it is time they stepped aside.

Radical departures from the status quo are never easy. They are always simultaneously symbolic and visceral. But they open up new possibilities for questioning what was once unquestioned and unquestionable. Something new and clean and wondrous is taking flight. It doesn’t need permission: it is its own authority.

May 14, 2015

We are angels, victims of everybody

I am a Gujarathi Kenyan. I never ever ever criticize Kenyan Gujrathis. I am a Yoruba African. Yoruba Africans have never ever done a bad thing ever. Not One. I am an Igbo African. I cannot share in public my real anger about Igbo political leaders. I am an African intellectual who is silent when my King talks genocidal shit. I am a Gikuyu. We are angels, angels! Victims of everybody. In fact everybody else is fucked up. I am a white South African – I have nothing to reconsider – if u ask me if I do I will emigrate. And somehow we all collectively believe that our intellectuals and writers will be at the forefront of looking inside ourselves and working on the dark hearts of our colonial crap. I am a White American author with power. If you brown American writers do not queue up behind our singular opinion of Charlie Hebdo – you are not loyal citizens and the powers are watching you. I am a Black South African – all the rest of you are why I am fucked. It was not apartheid. It was you. I am a Tanzanian African. Kenyans are beasts working too hard to undermine us. We prefer working for Afrikaner farmers – who by the way we give large tracts of land. All this is what animates much of our Facebook.

May 13, 2015

Annual NGO ranking shows that the “white savior” status quo remains intact

Teju Cole wrote that a white saviour is someone who, “supports brutal policies in the morning, founds charities in the afternoon, and receives awards in the evening”.

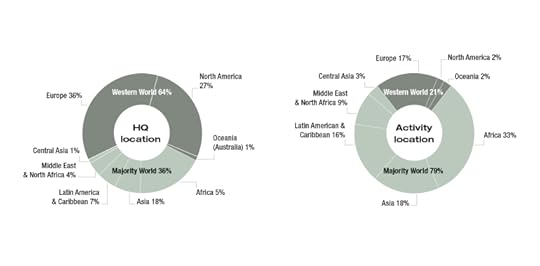

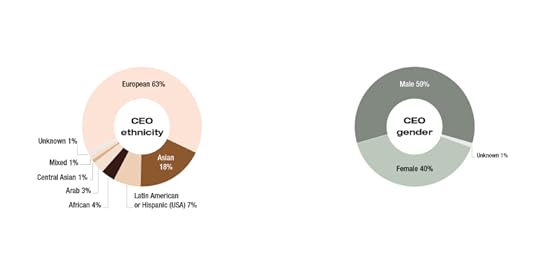

Global_Geneva recently released the third annual Top NGO ranking, and unfortunately, it’s more of the same. In 2013, I reviewed the Board profiles of the previous ranking, focusing on their gender balance and diversity, and links to the tobacco, weapons and finance industries. The findings were troubling. Many of the listed NGOs were not adequately diverse or representative, and over half had links to the above industries.

This year’s ranking reveals similarly disturbing trends. Though 78% of the activities of the NGOs listed take place in the majority world, the ranking remains skewed towards NGOs headquartered in the West (64%). This once again sends signals about who has value and expertise, and reinforces the fallacy that citizens of Western countries are best equipped to change the world.

Diversity continues to lag. Women and men of European origin are still over-represented in leadership positions (over 60% overall and by gender). The representation of women is still relatively low (40%, of whom 63% are of European origin). More disturbing, however, is the lack of ethnic diversity.

The statistics on Africa and Africans (including the diaspora) are once again particularly disconcerting.

Only 5% (26) of the 500 NGOs listed have their headquarters in Africa, yet 33% of activity takes place in that region. Of those 26, only 7 are in the top 100 and most (9) are found in the last tier (401-500).

Only 4% of CEOs are of African descent.

People of African descent are the only group in which there are fewer male than female CEOs. This implies an institutional bias against black men.

In the regional rankings, only 25 NGOs have been selected for the top African ranking compared to 100 each in Europe, North America and Asia/Australasia. Moreover, of the 25, 8 are outside the African continent (2 in Bahrain, 3 in Israel, 3 in Jordan).

Many NGOs continue to display stereotypical and patronising images and videos that portray Africans in particular as poor and needy victims devoid of agency.

In addition, a large proportion of the ‘top’ NGOs continue to appoint leaders who are not representative of the communities and groups they claim to serve, and retain links to corporate interests that appear to be inconsistent with their mandate or public identity.

As with the previous ranking, a number have Board members as well as funders with links to the tobacco, finance and weapons industries. Some, such as Room to Read for instance, pride themselves in such links: ‘Our leadership team is comprised of veterans of such venerable corporations as Goldman Sachs…’. Others are partnered with corporations that have been accused of human rights and environmental violations: for example, Akshaya Patra with Monsanto to provide food for children, Care with Cargill to combat poverty, Vital Voices with Walmart to increase economic opportunities for women, Injaz-al-Arab with ExxonMobil to mentor Arab youth. The International Crisis Group receives support from corporate members of its International Advisory Council, including Shell and Chevron.

Some also have affiliations with individuals whose political or professional record is arguably inconsistent with the mandates of the NGOs they serve: examples include the International Rescue Committee (Henry A. Kissinger, Condoleeza Rice and Madeleine Albright, Overseers), the International Crisis Group and ONE Campaign (Lawrence Summers, Board member), and Operation Blessing (M. G. ‘Pat’ Robertson, Board member).

The rather broad failure of many of the listed NGOs to have representative leaderships is reflected in some of their publicity statements and attitudes. Some exhibit slogans that offer absurdly simplistic solutions (‘You can cure starvation’ – Concern Worldwide; ‘Change the World in 4 clicks’ – Ufeed). Others display hubristic attitudes (S.O.U.L. Foundation says that its President represents ‘a new generation of young American activists who are quickly growing into a group of enthusiastic non-profit entrepreneurs and leaders who are choosing a piece of the world and changing it’; GreenHouse’s ambition is ‘trying to save the world by developing new models of social change to better people’s lives’). FAME World even adopts a disturbingly traditional missionary approach: it takes ‘Christ to the unreached and underserved’ but provides no assistance to non-Christian organisations.

We are all incoherent. Recognising this, where is the line between incoherence and deceit?

As individuals, we can easily deceive ourselves into believing that we do not perpetuate global inequities and discriminatory attitudes we claim to oppose. Organisations are no different. When NGOs are challenged to meet standards of integrity and fail to do so, they start to fit Teju Cole’s definition of white saviours.

International aid and advocacy is a multi-billion dollar industry and the corporate structures of the largest NGOs increasingly resemble those of large businesses. At the same time, NGO appeals for public support and public money rely heavily and distinctively on their claim to moral authority. Given this, it is entirely reasonable to expect NGOs to demonstrate their institutional integrity, including accountability to those they claim to serve. Unfortunately, Global_Geneva takes neither of these criteria into account. Consequently, by choosing to rank so many NGOs with such criteria, Global_Geneva and those who support it reinforce paternalist models of decision-making and governance that should be challenged rather than lauded.

Praise poem for the photographer Omar Badsha

Emmanuel Kant would have been distraught if he were to see Omar Badsha’s work.

Neither great beauties nor scenic vistas meant to evoke sublime pleasure were the focus of Badsha’s camera. His eye—sharp and contentious as his tongue is known to be—cuts through the cultural baggage that trains us to look at the beautiful and the acceptably pretty.

Garment worker, Durban. 1986

When we look at Badsha’s image of a garment worker standing in a hollow of darkness, her elbows resting on piled up cardboard boxes, her fingers intertwined and resting against her face in a gesture that we associate with prayer, we see this woman’s exhaustion, her despair, her supplication to a God who may be one of the few assurances in her life. Her body is tented by a shapeless uniform meant to fit the masses, and a long apron is fitted around the lower half of her body. Her hair is covered with a cotton doek, and it is the only thing on her uniformed, be-apronned body that is decorative – we can see a pattern of flowers peeking through the folds. But mostly, her face is obscured: by the hands that sit just under her fine, small nose, and the right thumb, stretched out to cradle her lower lip and cheek. Her lower face, and the shape of her jaw are lost to the black shadow around her. But she, and the boxes from the garment factory – those objects on which her livelihood depends – are bathed in an otherworldly light. Perhaps, she is working the night shift, and the source of that light is from a fluorescent light. But here, in this moment, she is god’s child, in communion with the Divine.

Laborers, Tadkeswar 1986.

I first encountered Badsha’s work at the International Center for Photography in New York, in December 2012 (Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, Sep 14, 2012 – Jan 06, 2013). There, in a display case, was a treasure: A Letter to Farzanah – (published in 1979 in commemoration of the United Nations’ International Year of the Child) – sixty-seven images and twenty-seven newspaper articles describing the lives of both Black and White South African children. Badsha collected this to serve as a record of the country into which his first daughter, Farzanah, was born; the cover consists of a photograph of his Tadkeswar-born grandmother with her newborn great-granddaughter in her arms: her face and body are curved in a sickle moon in their expression of doting love, the brightness from a window behind her setting alight the hopes she has for this fourth generation South African of Gujarati ancestry. She, a Nakhuda descendent of sea captains and navigators who travelled Surat, Africa and Aden, must have had hopes that her great granddaughter—this last generation on which she will lay eyes—will find a restful home here in this southern outpost. Together, the images and articles within Letter are both a love letter and an admonition to Badsha’s new daughter; it is a lamentation for the country and the historical moment into which she was born, yet also a finger-wagging exhortation: to not collapse under hopelessness, but to raise up her fist and do something.

Street performance, Durban. 1981.

Since that first experience with Badsha’s photographs, I learned that he is known for having fashioned a new visual vocabulary for translating the lives of those that apartheid excluded out of South Africa’s consciousness; often, the public whom he photographed may not have even realised that they were excised into the periphery of the nation’s vision of itself, nor have had the luxury of imagining themselves as part of the national narrative. The South African National Gallery’s invitation to his retrospective exhibition of drawings, woodcuts, and photographic essays from the mid-1960s to 2000s, titled “Seedtime” (Iziko South African National Gallery, 24 April until 2 August 2015) includes a characteristic Badsha photograph: that of a thin-limbed man, lying on a pallet, comatose after a day’s work. Above him, a line of drying clothes.

Migrant worker, Dalton House, Durban. 1986

This is the first time that Badsha’s drawings are juxtaposed next to his documentary photographic essays. His work, though mostly devoted to South Africa, includes life in far-flung places as well. Included in this exhibition are images from the Walking on Water: Migrants and travelling stories project: photographs of twin communities across the Indian Ocean – one, the city of Harar, Ethiopia and the other, Tadkeshwar, a small town in Gujarat, India (and the birthplace both sets of Badsha’s grandparents who emigrated to South Africa). The ancient communities of Harar and Tadkeshwar reflect a small portion of the subaltern world: tied by the voyages that the monsoon and the dhow allowed between the two shores of the Ratnakara – the “forger of gems”, as the Indian Ocean is known to maritime people along the Indian Ocean rim – and subsequently, connected by a history of shared colonial and post-colonial displacements that continue to this day; both draw their small wealth and continuation from the remittances that family members sent back from their new homes in far away places. Their inhabitants’ energetic ire, too, over marriage partners, land disputes, and squabbles over inheritance also continue to maintain centuries-long ties between two sets of people bound by the memory of voyage and loyalty to one’s kin – no matter the distance created by time and ocean.

Tadkeshwar

Though Badsha’s work has been an instrumental part of two books of photography meant to document apartheid conditions and build support abroad (notably, the Second Carnegie Commission on Poverty and Development–sponsored South Africa: The Cordoned Heart, and Beyond The Barricades: Popular Resistance in South Africa — books of photography that fashioned a new visual vocabulary for communicating the story of South Africa), and though he can also claim books of photography bearing solely his name (A Letter to Farzanah, published in 1979, and immediately banned; and his groundbreaking book Imijondolo: a Photographic Essay on forced Removals in South Africa, published in 1984, documenting life in the massive informal settlements in the Inanda area of Durban where he worked as a political activist), and though he is the go-to person that international scholars and curators seek out when looking for information about the history of political documentary photography, he is not one of the big names with which South African photography is associated internationally. The reasons are obvious: few commercial galleries were open to exhibiting the works of black photographers, and no agents came forward to promote black photographers’ work unless it had commercial appeal or spoke to the stereotypes that apartheid – and white supremacy in general – supported. Badsha refused to exhibit in segregated studios, or state-sponsored shows, marginalisng him already as a “difficult” character who didn’t play the game of supplication properly. And during the late ‘60s and ‘70s, unless black photographers took a specific kind of photograph documenting spectacular violence, press agencies didn’t come calling, either. In response to these disparities, in 1982, Badsha and a collective of photographers founded Afrapix, an independent photographic agency that not only helped promote black photographers on the international circuit, but played a significant role in documenting South Africa’s political climate during the 1980s, and shaped the tropes of social documentary photography in the country.

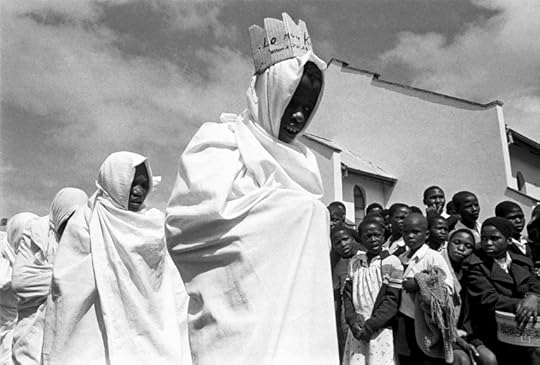

Easter pageant play, Pondoland, Transkei, 1986.

Badsha’s work—along with that of his Afrapix contemporaries—refashioned South Africa in the global eye; and together with his passion for organizing and union work, photography became a strategy of intervention in how the South African struggle against apartheid was seen. He and his contemporaries left the traditional mandates of documentary photographers—to stand apart, and record impersonally. Instead, they began their journeys by positioning themselves first as political subjects who were part of the resistance. Because of that, they were able to gain access into the everyday workings of the anti-apartheid movement, to community meetings, funerals of those who were killed by the South African security forces, and to be witness to ordinary acts of resistance, endurance and survival. Yet, perhaps because Badsha’s interest was in collective organizing, and not personal fame, his own work was not as well recognized.

Helen Joseph, Christmas Day, 1981.

So we can blame politics for why Omar Badsha’s photographs, or why his life’s work is not known in the same realm as the careers of others. But there’s something else, too, I think. It is Kantian aesthetics that still influences us when we say that certain works have “political” value, and others are “beautiful”; Kant argued that our aesthetic judgments must be based on our disinterest in the object we are viewing: our pleasure in something should not be connected to its ability to be useful, or informative or persuasive in any way. According to the Kantian moral universe, artists who produce with aesthetics as their guiding principle provide us, in these godless times, with the ability to discern and experience beauty as part of an ordered, natural world, and enjoy a moment of transcendence.

Women at celebration, Harar, 2001.

However, though Badsha sought to reveal the extraordinary lengths to which the apartheid state went to in order to dispossess black South Africans of land and ability to make a viable living, recording life in the margins of racialised ghettoes where the brutality of apartheid was most evident, his images are not simply those typical in the repertoire of the photojournalist. Rather than following violent flares between black South Africans and the apartheid regime’s police forces, he recorded the dynamics of daily life under apartheid. His images in Imijondolo is a calendar of everyday existence on the frontlines of powerlessness and poverty: here, we see a girl in an ancient hand-me-down dress – the flowery pattern adding little pleasure to her impossible task – carrying small lumps of mud to plaster the walls of her house. Her face and arms are smeared in mud. She balances the ball of mud on her head, with her small arms and hands reaching up, steading herself and the mud on her head. Her expression is that of the Sisiphean warrior: resigned, methodical, carrying on with her balancing act with as much dignity as possible. Among the images of children learning their English lesson in spare classrooms, and diligent, head-bent-in prayer Bible readings in Amouti Primary School, are mirror images of a sari-clad Indian grandmother and a young boy in her charge, and that of a milky-eyed, large-bosomed Zulu pensioner and her tiny grandchild who is busily engaged with exploring the world circumscribed by the woven mat lining the floor of their small mud house. Another is that of a shy, young Indian woman – with a low hairline and as round a face as any Tamil village beauty an ocean over – leaning on the brash confidence of her black husband; their young child scowls at Badsha’s camera. The doorway in front of which they stand is lined with a decorative flounce – the kind I’ve seen often in South Asian homes: a narrow band of cloth, gathered together by a runner of rope, and hung over to top rung of a door: it is not long enough to be a curtain of privacy, but a decorative element indicating an entryway.

Young woman repairing home, Inanda, 1982

Badsha’s images show us that forced removals recognised no difference between Indian, Zulu, Muslim, Hindu, and Christian, and that the alliances forged in the poorest and most marginalised of ghettos of apartheid South Africa may be as powerful and as transgressive as those at the higher echelons of the resistance movement. But his photographs do not create fantasy-pastorals of poor South Africans, either. Here also is the fat landlord, seated on his best chair; above him, framed photographs of his bejewelled Gujarati grandmothers and suit-wearing grandfather. Here, also, is the gun displayed by the local powerbroker and induna, doling out pension payments and favors in the neighborhood.

Family, Tadkeshwar, 1986

At the core of the conversations I’ve had with Badsha is his tenacious grip on political integrity, and on directing the aesthetic, intellectual, and educative focus of his photographic projects. Controlling that intellectual authorship, and managing intentionality, despite pressures that international news organisations, local gallery owners, art dealers, and even one’s own ambition to compete with one’s friendly rivals in the world of South African photography is a daunting life project for a photographer. Certainly, challenging established apartheid tropes for art and photography, and documenting the fraying fabric of the national project had obvious risks. And Badsha’s positions and steadfastness to the mission to which he committed himself as a photographer cost him in certain ways, but this wilful desire – to record and be witness to subsumed histories, to walk in with his unapologetically political lens – also maintained his integrity as a narrator of South African history.

* A retrospective of Omar Badsha’s work is currently on show at the South African National Gallery in Cape Town until August 2nd.

Let’s talk about Charlayne Hunter-Gault’s e-book on “Corrective Rape” in South Africa

Charlayne Hunter-Gault’s ‘Corrective Rape: Discrimination, Assault, Sexual Violence, and Murder Against South Africa’s LGBT Community’ is a rather wordy title for a mere 51 page e-book. Attempting to expand upon her original article ‘Violated Hopes’ from The New Yorker, the e-book claims to shed ‘light on the practice of corrective rape’ and examine ‘the wider social context of anti-LGBTI sentiment in South Africa’, and the ‘search for equality in a post-apartheid nation’. Lofty goals by any standard, the e-book does not quite manage to accomplish it. The 2012 New Yorker piece was accompanied by Zanele Muhoni’s photographs of black lesbian women, which added depth and nuance to the article; something that feels as though it’s missing in the longer e-book.

Charlayne Hunter-Gault, a Pulitzer Prize winner, is undoubtedly a gifted writer. She tackles a complex and tricky subject with obvious compassion, handling interviews-whether with survivors, activists, or police officers- with care and stays well away from the tired ‘saviour’ trope. Weaving these voices, experiences, and examining these incidents within a larger narrative of South Africa’s much-heralded constitution, country interventions at the United Nations, and public comments from politicians and leaders including Jacob Zuma and Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini; she attempts to move beyond just murder and rape statistics and understand the contexts, histories, and power struggles that surround them.

Hunter-Gault contrasts South Africa’s equality law that recognises and protects the rights of LGBT persons with the rest of the continent, positioning South Africa as a ‘unique’ model. While narrowly avoiding the ‘South African exceptionalism’ trap, she juxtaposes the progressive laws and commitment to human rights enshrined in the South African constitution with the increasingly restrictive laws being enacted across the continent. There is some reference to the impact of apartheid on South Africa and its evolving identity, but she overlooks the colonial legacies that contributed to many of the anti-homosexuality clauses in penal codes across the world; also affecting LGBT and queer struggles in very particular ways.

LGBT and queer struggles intersect and grapple with multiple oppressions and power dynamics and can be an intimidatingly contentious space — this is true not just globally but within national struggles as well. The book, while bravely attempting to decode and unpack the complexities of South Africa, suffers from a lack of nuancing of LGBT movements themselves. In post-apartheid South Africa, race and class are just two of the intersections that queer organisers must work at, as evidenced by certain groups boycotting Cape Town’s 2014 Pride March as ‘apolitical’, and the ‘die-in’ organised by the One-in-Nine campaign during the 2012 Joburg Pride. Although the majority of interviewees and incidents that Charlayne Hunter-Gault refers to are black, she never directly addresses or engages with the issue of race within ‘corrective rape’. By treating it as peripheral — however unintentionally — it overlooks the continued silencing of (and inaction around violence against) black voices and bodies, and the fault lines of race within LGBT organising itself.

The e-book does little to dispel some of the questions and concerns raised around the original article, including the use of the questionable terminology, ‘corrective rape’. A deeply contested term within LGBT and feminist groups, the term refers to the assault and rape of persons because of their (perceived or real) sexual orientation or gender identity to ‘cure’ them. A loaded term, it does not just advantage and lend credence to the perspective of the perpetrator; it adds another layer of silencing of victims and survivors. The term is also criticised for making sexual orientation/gender identity the point of discussion, rather than the structures of violence- heteropatriarchy, classism, and racism- that manifest in sexual violence and assault. Other critiques of the term also find a burgeoning mythology along race lines, with repeated assertions of ‘Black South African (men) believe that raping a woman can make her heterosexual’. Instead, it has been suggested that these forms and acts of sexual violence be understood within the rubric of ‘hate crime’, with an analysis of the misogynistic and heteropatriarchal frameworks embedded within it. It is curious that despite numerous conversations with LGBT and gender justice organisations, Hunter-Gault continues to use the term without explaining the reasoning or positioning behind it.

While the e-book was a quick read, it does not offer new perspectives or critiques to the ongoing discussions around ‘corrective rape’ in South Africa or globally. The original article was a succinct read as a standalone piece and showcases Charlayne Hunter-Gault’s impressive writing skills, which raises the question of why an e-book was needed given that the additional material does not really elaborate on the points already made within the article. The article and the e-book do not venture into the murkier and deeper waters that surround the issue of ‘corrective rape’ but are a good starting point for those unfamiliar with the South African LGBT context and are interested in learning more about it and exploring some of the contested spaces and issues.

May 12, 2015

Black Film, White Masks

As most young ambitious filmmakers, I of course decided that my first feature length film would be an epic sci-fi post-apocalyptic piece that was somehow going to have these incredibly deep Terrence Malick roaming camera type moments in the Namibian desert. Complete with African narration mouthing something deeply profound about black existentialism in the face of certain death. But at the same time we were gonna have these swashbuckling warriors complete with afrocentric costume vibes and future neon space shit battling our sadistic baddie who just happens to have a German accent. Not that there are any colonial metaphors here. Anyway, suffice to say we’re still trying to raise the gazillion dollar budget and in the mean time I’ve sort of acknowledged that I might do a slightly smaller film first. You know, something that takes place entirely in an elevator, or something similar, before taking on the impossible.

Whilst trying to raise funds for my sci-fi extravaganza I quickly realized how small we were. Not just the fact that I simply don’t get the right hits when googled or IMDB’d, but that our story about a bunch of blacks in Africa going on an adventure, the apocalypse, colonialism, no white leads, etc — it just wasn’t big enough. Or rather it just wasn’t white enough. I was told by a sales agent in Cannes that she’d rather we’d replace our black lead with a dragon. A dragon, yes a dragon! In another meeting an excited Canadian producer was ready to sign on the dotted line provided I insert a terrorist plot in the film and a plane full of Europeans stranded in the desert. This went on for some time. I knew we had a fresh original take on the old mass produced apocalypse thing but the gatekeepers just weren’t buying this story so long as it took place in an African context. I realised that these sort of films simply don’t get made. Ever. The black voice in cinema occurs on the margins and is filtered, distorted, watered-down, negotiated, corrupted. It’s as if Hollywood operates as brothel-keeper to the omnipresent empire. You only have to watch Exodus: Gods & Kings to witness how stories set outside the West are skewered so as to preserve the myths that justify Eurocentricity.

What I found was that the most damaging of these myths is the idea that Africa is the bogeyman — Full of both exciting and depressing examples of thugs, rapists, druggies and flashy hustlers. This myth allows the west to ascribe all its fears, whether real or unfounded, on Africa to justify white supremacy. The most notable films to have been made by or staged in Southern Africa have all been directed by white men. They include The Gods Must be Crazy (1980) dir. Jamie Uys; Mr. Bones (2001) dir. Leon Schuster; Tsotsi (2005) dir. Gavin Hood; District 9 (2009) dir. Neil Bloomkamp; Jerusalema (2009) dir. Ralph Ziman; Zulu (2014) dir. Jérôme Salle.

When Frantz Fanon wrote his seminal work Black Skin, White Masks, he presented a sociological study of the psychology of racism and the dehumanization experienced by the African diaspora. He suggests that black people experience a trauma related to an unconscious indoctrination from a young age that teaches them to associate “blackness” with “wrongness.” This is experienced in a variety of ways: Through the workplace, society, media, and elsewhere. My primary concern is that as a Namibian filmmaker, I still find cinema’s depiction of black masculinity as hyper violent, one-dimensional, poor, diseased, unduly sexual and antithetically opposed to white mainstream examples of “goodness.” By deconolizing the screens Africans might experience the world without the limitations imposed by centuries of dehumanizing constructs of “blackness.” In what remains a Eurocentric patriarchal world whose foundations are built upon the subjugation and disenfranchising of mostly black and brown populations, such a “new” reality remains out of reach.

Jérôme Salle’s Zulu gave us yet another exoticised African despot with a mostly colonial narrative: Angry natives, diseased black children; shanty towns; a heroic white male; a broken black man; a lustful black woman; a beautiful untainted white woman; machete wielding thugs; and a few white supremacists. Ali (Forest Whitaker) has renounced his ethnicity. Or as writer J E Kelly puts it “he has discarded his ethnicity, to overcome not only his experience of violence but an inherent tendency of his people to beat on the drums, perform war dances, and of course, act violently.” For in this Zulu there are no lion skin donning warriors, instead we find a neutered man unable to sleep with his girlfriend and incapable of voicing his frustrations with both past and contemporary South Africa. In a word, emasculated. For the patriarchy to succeed it thrives on a kind of infinite virility, therefore on a genital level the castrated Whitaker represents a kind of sexual revenge. An insurance against black superiority. There remains very little room for an honest engagement with what being black truly is in contemporary South Africa.

Current socio-cultural attitudes towards identity seem more strongly influenced by economic factors rather than simply racial implications. It is only the idea of Benedict Anderson’s “imagined community” masked today in South Africa as the “rainbow nation” or in Namibia as the policy of reconciliation that thinly holds together this faux republic. By taking a closer look at the portrayal of black masculinity in African films, and the fact that these films are made by white male filmmakers one might consider how they contribute to Fanon’s assertion that the black man sees himself not through the eyes of a black man but through the mask of a Eurocentric construct. How then could I have been so naive as to expect a sales agent in Cannes to wholeheartedly embrace my vision. She too, was seeing through that old mask. The one that encourages a watered down synthetic kind of culture. The culture of empire. The problem with empire is that it creates a one dimensional world rather than a polycentric one. Therefore it does not concern itself with what a different voice might look like. The fact that our films are still formulated by this one dimensional view means that the majority of our populace remain, not just economically disenfranchised but, culturally under represented.

The trials of black filmmakers like myself are simply a reminder of the importance of nurturing our systems here at home. We must find ways to develop and nurture a more imaginative African cinema. While we all wish to have our films screen at festivals around the world and in cinemas abroad we must also be allowed to make films on our terms. By doing so we have the opportunity of rewriting the script that has so often cast black men in damaging degrading roles on screen. It is a call to decolonize not just the continent but the screens as well. Let us commit to deconstructing every film in order that we might learn more about ourselves. We must pay close attention to how we portray each other on screen, so that the films we make might breathe new life into old tropes and on screen representations of “blackness.” With this we might help to restore and re-imagine Africa.

Check out Perivi’s film reel on his Vimeo page, and his short film “My Beautiful Nightmare” on SnagFilms.com.

May 11, 2015

To be young, privileged and black (in a world of white hegemony)

Today is March 19. Tension fills the Rhodes University campus in the small South African university town of Grahamstown. The university’s student representative council had announced a day earlier that a meeting would take place today to allow the student populace, the various student representative societies, and university management to discuss the ructions taking place at the campus and at other universities across the country.

Students run rhythmically through the university’s passages and alleyways, spilling out onto the main road leading to the Great Hall, where the meeting is to be held. They sing protest songs and struggle hymns with passion and an intuitive harmony. One group of students chant “Yinde Le Ndlela Esiy’hambayo” (the road we are traveling is long) as they pass by. The group immediately behind them, sing the elegiac Senzeni Na. I step aside to bear witness to the cacophony, as though trying to recall the days of a revolution I was born too late to witness.

The Great Hall is filled to capacity with students brandishing cardboard signs bearing different phrases. Life is hard without a laptop, goes one. #WeCantBreath, goes another. #RhodesSoWhite and #RhodesMustFall, also feature. As the crowd settles, the hall turns from a place of protest to one of testimony. Students line up on stage to express their concerns, with the vice-chancellor looking on. Booing, clapping and singing accompany each grievance voiced.

The meeting is approaching its third hour. A young lady is given the microphone. She steps forward and introduces herself but seemingly can’t find the words to articulate her concerns. She stutters, tucks her lips into her mouth and closes her eyes. The room falls silent. She draws her face into one hand while the other falls from the microphone and comes to rest at her side. Resignation. She is in tears.

“Be strong, gal!” someone shouts from the back of the hall.

“We got you, sweedaat!” another voice shouts.

The hall breaks into a chorus of encouragement as the young lady gathers herself. Finally, she speaks.

“I am black. I am a woman. I was raised by my grandmother. I come from a working-class background,” she begins.

She strikes me as someone who has lost something important, yet cannot afford to mourn. Her strength and resolve menace me. It is as though she is calling on a part of myself I refuse to think about. I sense in her testimony a confrontation of this refusal. The hall is too full and too still to exit unnoticed. I am trapped for my own good and I know it. So I sit and listen.

“I come to Rhodes and the culture tells me that we are not enough,” she says.

Her voice begins to shake again, but she maintains her posture.

“The culture here tells us that we need to qualify ourselves each and every day to maintain the fact that we deserve to be here,” she says.

In that single sentence she captures one of the most elusive and violent experiences endured by souls in black skin. I feel something in me relax. A cryptic muscle that has been working faithfully to maintain the burden of perpetual conviction comes to rest. Her words unlock a cache of emotion now available for my claim. An unusual reassurance. I smile.

“It is through our lecturers, who are condescendingly patronizing towards us; the white students on this campus just don’t understand,” she continues.

She is now governed by the story she’s telling. Her narrative surpasses her tears. I place my hand on my chest to feel the resonance of her words, for these are truths I have been living to negate and disregard for as long as I can recall.

“They hurl insults at us. They call us stupid. They call us angry for no reason. They call us illogical. Yet, they don’t understand the lived experience of what it means to have the color of this skin on this very campus. There is no cushion that [softens] the blow of being black in this institution!”

This final affirmation destroys the illusory freedom to which I had begun to become accustomed. I am overcome by betrayal, by being the betrayer, and the feeling startles me. My solidarity with her seems to be a farce now. We are not the same. The truth about our differences makes me feel as though I am being tricked by everything about me, once again. I pick up my camera and continue to take pictures to distract myself from contemplating this particular truth which her testimony has revealed.

ii.

It is May 1. The young lady’s words still mark my conscience, forcing me to pick apart my emotional response to her. Her testimony leads me consider the generation betrayed, and the generation made complicit. It leads me realize that the Rainbow Nation project, so proclaimed by Nelson Mandela in the year before my birth, has failed the young lady, myself and many others of my generation. It also makes me realize that the idea that some of us were ‘born free’ into this Rainbow Nation works only for some, among whom I am included.

As I begin the task of freeing my mind from these ideologies of the South African democracy, I have no choice but to reflect explicitly on my intimate relationship with white hegemony.

The story of who I am should make me the idea sop for the propaganda that has sold an optimistic yet inaccurate story about the quality of South Africa’s reconstruction and reconciliation project. I am a black child born after 1994 and whose parents’ affluence has allowed me to transcend the absolute and relative poverty that is the norm for other black children so born. I was born and raised within the meters of Africa’s richest square mile. I am not the first in my family to go to university and I am unlikely to inherit the financial obligation of supporting extended family members. While I am proficient at three indigenous South African languages, I am more proud of being able to speak the kind of English that astonishes even white people. The extent of my fluency in white culture has afforded me experience in the corporate sector, even at my young age. I have even defied stereotypes by being one of the few blacks to compete in aquatic competitions at a national level for two consecutive years. I am socially, economically, politically and even epistemologically of value to whiteness. White hegemony has recognized my capability to understand its culture; it has praised me for participating in it. And, more so, it has rewarded me generously for assimilating into it.

How I relate to white hegemony is undoubtedly rare, though not exceptional. And it is becoming less rare by the year. It is similar to the stories of others of my generation who have consciously or unconsciously assimilated into whiteness. However, to avoid generalizing and grossly simplifying this topic, I will speak only of my own experience. In that experience my relation to white hegemony contains three main elements: exclusion, comfort, and fear.

iii.

The exclusion

The exclusionary nature of my assimilation into whiteness encourages me to think of myself as a survivor who is set apart from inheriting grievous disadvantages passed on to the average young black person in this country. It forces me to consider myself (and to be considered by others) different in many material and unquestionable respects. It forces me to think of myself as the exceptional black, taking from me the right to speak from my own perspective on issues such as #RhodesMustFall. I am beloved by the gate keepers of this hegemony, yet resented by those who have yet to be accepted into it. Therefore, I am in a difficult predicament whenever I attempt to articulate the ways I relate to the symbolic, cultural, economic and institutional remnants of a colonial past.

The comfort

The comfort in my assimilation to whiteness is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it releases me from certain psychologically and emotionally taxing ‘fixtures of blackness’, such as having acute concerns about topical social issues such as poverty, and participation in political and social organizing on campus. I don’t, in other words, have to define myself as black and to unite with other blacks to overthrow the hegemony as I have been accepted into the hegemony. The price I pay for this, the price white hegemony demands, is that I remain silent, preferably ignorant, about certain aspects of civil life. My assimilation into white culture requires that ‘being black’ become an occasional fixture of my identity instead of an integral part of it.

When the March 19 meeting took place, I was faced with a conscience-threatening dilemma: Do I attend the meeting and commit to the cause, risking ideologically betraying the hegemonic project I have unapologetically, but uncritically, endorsed my whole life? Or do I not attend the meeting, comforted by the assurance that I will not be chastised and labeled morally irresponsible for abstaining from the conversation in its entirety? Ultimately I attended, and the young woman’s testimony uprooted my comfort. Her state of insecurity on campus, owing purely to the fact of her blackness, is evidence that the presence of black bodies in an institution such as this is not enough to transform it into a place not only tolerant but welcoming of and changed by difference.

Her words devastated me. Had I not passively and successfully learned to mimic whiteness, I, too, would share her concerns and insecurities about being black on such a campus. My sense of security is nonetheless hollow because I have been preoccupied with trying transcending the psychology of inferiority by assimilating into the culture that imposes it: I internalize, then set myself apart from those condescending words of the patronizing lecturers against which she protested. I endorse my privileged silence when white students dehumanize their black peers for not conforming to the norms of white etiquette. I am welcomed into spaces of social, corporate and political engagement without challenge, as I am symbolic proof that the white hegemony’s project of ‘civilizing’ the native is not a myth.

The punitive

The fear-oriented element of assimilation dictates that punitive consequences be taken should there be defiance of any kind that threatens the unity between this hegemony and I. While I have not experienced significant losses from renouncing my participation in whiteness, the element’s aim is to instill the kind of fear that impairs rational thinking. Therefore, the thought or act of questioning, challenging or offending any part of this hegemonic project is inhibited by my phobia of doing so. The comfortable and exclusionary natures of this hegemony create, for me, a prison whose bars I have been indoctrinated to not break.

I realized this when my journalism and media studies tutor asked the group recently:

“Who feels at home here at Rhodes?”

The majority of the room raised their hands. Only three hands were missing from the gaggle eager to say why they considered Rhodes University a home away from the homes they came from. The three hands were all black. I took a look at my own hand raised unconsciously in the air and felt guilty. I guess, in truth, I did consider Rhodes as my second home.

My lecturer picked me to start the conversation. I can’t remember what I said but I know I was sarcastic and amusing, because fear barred me from being forthright and raw in challenging the comfortable lives of the majority of the room. What was supposed to be a fierce debate about the contemporary legacies of figures such as Cecil John Rhodes became, with my assistance, an unreflective and safe discussion. My complicity in this resigned me to silence for the rest of the discussion.

Had I been the kind of person in whom the redemptive power of honest and inconvenient conversations trumped the fear of rebelling against the hegemony, the appropriate answer I would have given to that question should have been: Yes! I feel most comfortable at Rhodes University, because it is more than an escape from the pretenses of northern Johannesburg where I am from. There is neither defeat nor victory nor struggle for me here. The institution does not dare challenge my identity in ways which matter. As a black member of the elite, Rhodes University is a secluded and affluent space that affords me the ability to unconsciously refine my mimicry of white hegemony, in peace.

iv.

My relationship with white hegemony does not solely refer to my interaction with white or black people. It does not directly refer to my attitude towards race and class issues. Nor does it speak about an experience which can be regarded as a norm. It is merely one of many examples that reflect the state of South Africa’s transformation project. My relationship with white hegemony speaks about the inequalities between advances in the structural transformation and regressions in the quality of lived human experience. It speaks about the disparities between material equality and psychological poverty. It speaks about how hegemonic systems of oppression mutate and subsequently continue thrive within eras of democracy.

South Africa is not a phenomenal country. It is a country famous for its phenomenal events and supposedly miraculous transition from white-minority rule. However, we are misguided in thinking that the story this country ought to continue telling is one wherein we are survived by our ability to reproduce these events globally regarded as admirable and miraculous. The Rainbow Nation and Born-Free ideologies are contemporary examples of these induced miracles. These two ideological projects have distracted us from doing the hard work of healing our society from the core. The endorsement of these ideologies has inhibited us from having necessary, honest and inconvenient conversations about our experiences and collective identity. The unfortunate reality is that these democratic ideologies belong irreducibly to a time where freedom still has the power to choose its proprietors.

We think we are free, yet all we have ever done is cover gunshot wounds with plasters.

*This essay is an edited version of a post that originally appeared on the author’s blog, SuburbanZulu. The title of this essay is mildly influenced by notions of engagement relating to an academic paper which is still in the process of development. That particular paper is researched, developed and written by Siseko H. Khumalo.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers