Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 350

April 25, 2015

“A malignant ‘nativism’ threatens post-apartheid democracy (in South Africa)”

Africa is a Country editorial committee member Dan Magaziner and I published an oped on The New York Times about the current (briefly subsided) violence by South Africans against other black Africans from north of their borders. We wanted to move away from broad characteristics of the violence as xenophobic by focusing on recent history and the present meanings of documents like the Freedom Charter which shapes political identity there. Here’s an extract:

… The recent outbreak of xenophobic violence (in South Africa)is a direct consequence of (the political) compromises (of the early 1990s). Usually labeled a “miracle transition,” the early 1990s were actually a period of tremendous violence in KwaZulu-Natal and around Johannesburg. The unrest was fueled in part by the apartheid government’s efforts to sustain itself by promoting rivalries between the country’s “traditional” or tribal authorities and the nationalists affiliated with Nelson Mandela’s A.N.C.

The country was beset by ethnic and regional conflicts, emanating from the white minority and the various ethnically defined homelands that the apartheid government had created. King Zwelithini was the symbolic leader of the strongest of these, representing nearly 10 million Zulus, the largest ethnic group in South Africa. The king’s brand of ethnic chauvinism appealed especially to young, poor men. Along with KwaZulu’s chief minister, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, and the Inkatha Freedom Party, he repeatedly threatened to sabotage the landmark 1994 election. One of the A.N.C.’s triumphs was to co-opt these nationalist leaders into the new South Africa, without requiring them to give up their Zulu chauvinism.

Traditional leaders like King Zwelithini were put on the state’s payroll as part of a group called the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa. This gave them new legitimacy and brought a measure of peace to KwaZulu-Natal — and eventually brought the province into the A.N.C. fold, but at a cost. It gave legitimacy to a form of ethno-nationalist politics that the A.N.C. had officially opposed during the anti-apartheid struggle.

In the interest of governing, the A.N.C. opened its ranks and offered support to a range of ethnic and regional interest groups, including elements of the former apartheid regime and traditional leaders. Mr. Zuma himself exploited Zulu nationalism in his own battle for the presidency.

The ethno-nationalism that marked apartheid’s dying days has now morphed into a malignant “nativism” that threatens post-apartheid democracy.

Mr. Zuma has not done much to address the crisis. He issued a soft condemnation a week after the first attacks started and offered migrants safe passage back to their native countries. He has since sent the military into the most restive areas, while criticizing the media for over-hyping the story. At no time has he criticized the Zulu king.

If Mr. Zuma wanted to offer concrete solutions, he would do well to look back to one of the most celebrated chapters in his own party’s history. In 1955, a variety of groups, led by the A.N.C., adopted the so-called Freedom Charter, which declared, “South Africa belongs to all who live in it.” The charter’s signatories included black Africans, descendants of slaves imported to the Cape Colony, laborers from South Asia and immigrants from Europe. The first post-apartheid Constitution, in 1996, enshrined the promise that the country belonged to all. Recent days have shown that there are limits to this promise.

For many poor blacks, the label “South African” and the accompanying right to be represented by a democratic government are the only reward they earned from long decades of struggle. During the negotiations to end apartheid rule, the idea that South Africa belonged only to “those who already lived in it” was one issue on which the white minority and the liberation movements already agreed. In their view, the struggle over apartheid was contested by South African nationals, and the nation belonged to those who had declared it for themselves during that struggle.

King Zwelithini and his supporters took a while to see the benefits of being counted as South African, rather than Zulu, but now some of them have seized on that identity with fervor and directed their anger against outsiders who have arrived since 1994. Despite the Constitution’s claims, the Freedom Charter apparently applies only to some, not all, who live in South Africa.

April 24, 2015

The first genocide of the 20th century happened in Namibia

Today marks the 100 year anniversary of the Armenian genocide. Media coverage has focused on the refusal of Turkey to acknowledge the genocide. It is indisputable Ottoman Turks carried out genocide against the Armenians in 1915. But the oft-repeated assertion that it was the first genocide of the 20th century is wrong: it was the attempted annihilation of the Herero by the Germans in South-West Africa (present-day Namibia) from 1904 to 1907.

The language, methods, and scale of the Herero genocide remain shocking even in the aftermath of the horrors of the Holocaust. In their quest to occupy and exploit the territory of the pastoralist Herero, the German colonizers recruited a mercenary army led by Lt. Gen. Lothar von Trotha. The Vernichtungsbefehl (“Destruction Order”) he issued was terrifyingly clear: “Within the German borders, every Herero, whether armed or unarmed, with or without cattle, shall be shot.”

The genocide culminated in the infamous “march into death” of Herero who were forced into the Omaheke Desert. The Germans sealed the perimeter with guard towers, poisoned water sources, and then bayoneted to death Herero who attempted to escape dehydration. An official history of the German General Staff compiled after the genocide rightly concluded: “The arid Omaheke was to complete what the German army had begun: the annihilation of the Herero people.” Those who survived the desert were sent to concentration camps where captured Herero soldiers, along with women and children, were forced to work. Women boiled and scraped the skin off the heads of Herero who had been killed. Those skulls were then shipped off to Germany for museum displays and eugenics research.

Recent articles highlight that Hitler, while planning the Final Solution, dismissively remarked “Who remembers the Armenian genocide?” Indeed, even less known was (and remains) the Herero genocide which has many parallels with the Holocaust: the destruction order, the concentration camps, the forced labor. The so-called scientific research by German geneticist Eugen Fischer, who argued that mixed-race children in South-West Africa were inferior to the offspring of German parents, was cited in Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

Up to 80% of the Herero died during the genocide. While a former official of the German government apologized for the genocide on its 100th anniversary in 2004, the Herero have never received reparations. Let us set the historical record straight: the first genocide of the 20th century was carried out by Europeans in Africa.

Why the wall Kenya is building on its border with Somalia is a terrible idea

For the last year, Andrew Franklin, a former US marine and now security consultant in Kenya, has been advocating for the construction of a separation barrier between Kenya and Somalia. He dubs it the Somalia Border Control Project, and it will include militarized instruments such as “physical and electronic barriers along the entire border” and the “laying of properly marked and mapped minefields,” among other interventions.

A few days before the most recent Garissa attack, numerous National Youth Service trucks equipped with building material were seen headed to Mandera to begin work on a separation barrier. Though not to Franklin’s specifications, as he would assert in a television interview, the wall in its present iteration is still a nod to his Somalia Border Control Project, and is viewed by the Uhuru government as necessary to enhance security.

Notwithstanding the fact that construction of the wall has begun, and will likely gain more support after the attack in Garissa, there have been no consultations with local communities, nor has this wall even been debated in parliament. Like most actions in our Kenyan version of the war on terror, executive decrees become taken up as law under the veneer of national security.

The M.P. for Wajir West Hon. Abdikadir Ore Ahmed is fearful that this project has not considered the pastoralists who have homes and livelihoods in both Kenya and Somalia, nor the peoples whose lineage and relationships defy geographic boundaries. In addition, he asserts that the free movement of people on humanitarian grounds in light of forthcoming Somali elections in 2016, which may prove particularly heated, will be curtailed. In such a scenario where they did need to come to Kenya, what they would likely encounter are a border wall, mapped minefields and electronic barriers.

Furthermore, little thought has been spared for the refugees, most of them female and young, who would be affected by the calls to shut down Dadaab camp and that are coupled with support for the building of the separation barrier.

If construction of the wall continues and the camp is indeed shut they will face increasing uncertainty about whether they can ever come back if they need to, despite the fact that many of them were born in Kenya and it is the only country they have ever known.

It is likely that this wall takes inspiration from Kenya’s close political and military partners—the U.S and Israel, who have constructed their own apartheid walls to keep out “illegal migrants” and “suicide attacks” without historically examining just who the real illegals and attackers may be.

It is also important to question who will receive the economic bounties from this wall, and whether this process is characterised by the same irregularities as the safaricom integrated communication and surveillance system tender. Perhaps highlighting the possible benefactors of this barrier, Franklin asserted that “Kenya’s foreign allies in its war against terror are willing to support security related infrastructure development – as has been done elsewhere (e.g. Afghanistan, Kurdistan, Djibouti) – and the government needs to put forward its case for no strings attached financial assistance without delay.” Lessons from Afghanistan, Kurdistan and Djibouti unequivocally illustrate that there is never any “no strings attached” financial assistance from foreign “allies.”

While a seemingly large segment of the population has expressed support for the wall, ostensibly, to curb the entry of “illegal” Somali immigrants who are blanketly assumed to be al-shabaab, it is interesting that we Africans forget that the border itself is an illegal colonial construct. Frontiers, not people, are the real “kwerekweres.”

What is also forgotten in these calls is that we have much more to fear from within our borders than from without. If we are to build it we are enclosing our own terror, in its multiple and violent manifestations, that is a consequence of our ongoing complicity in the historical marginalization of North Eastern Kenya, and our uncritical support for KDF and Amisom in Somalia; actions that make many North Eastern residents wonder if they were ever really Kenyan.

Therefore, military actions that seek to dismember Somalia are not solutions. Nor are similar actions within Kenya, such as the rounding up of Kenyan Somalis in Kasarani concentration camp in 2014, as well the frequent raids in Eastleigh which were part of Usalama Watch. Rather, what is required, and as Mamhood Mamdani and others argue, is a political solution and not a military one which may only become part of an ongoing cycle of violence.

Additionally, it will work towards further dividing the continent and will highlight that Uhuru’s declarations of Pan-Afrikanism (which seem to apply conveniently only with regards to the ICC) are not grounded in any real sense of oneness.

If we were really serious about African unity, about national healing and about being Kenyan, we would organize vigils for both Kenyans killed by al-shabaab, as well as Somalis killed by KDF while questioning their real motives in Somalia. We would not have defended Kasarani Concentration camp nor condoned the Eastleigh raids.

Instead we cry reactively over spilt milk, and refuse to ask ourselves proactive questions that could protect all of our children. As a consequence, it is inevitable that this barrier will reveal the real depth of our inaction that should have been rectified from within, and not from outside the imminent border wall.

Digital Archive No. 17 – Digital Matatus

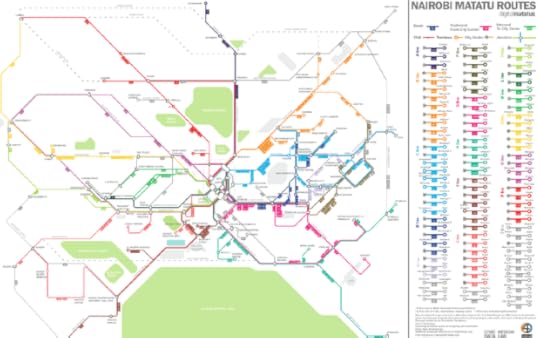

For the past couple of months, I’ve only been able to get out posts on a biweekly basis because my graduate school load was fairly heavy. But things have eased up a bit for now and I’m hoping that I can get back on a weekly schedule since there are so many awesome projects that deserve their own feature on this platform. But, for now, this week’s featured project is Digital Matatus, a collaborative mapping project between University of Nairobi‘s C4D Lab, Columbia University’s Center for Sustainable Urban Development, MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab, and Groupshot.

Anyone who has spent a significant amount of time in a major African city knows how key the informal transit network is. Whether it’s khombis in Durban or molues in Lagos, informal modes of transportation are easily the cheapest and most effective ways of getting around the city of your choice. The problem with these networks is that it requires a lot of insider knowledge. Routes, rates, hand signals, and etiquette are all things that have to be passed on to you from someone else in order to get to and from where you need to go. In a lot of ways, this system can come across as chaotic, unruly, and impossible to tame. Matatus are the minibus taxis that crisscross through Nairobi daily. Arguably, the city is dependent on this mode of transportation, as most people get to and from work on these minibuses. The problem with this system is its informality, with changing routes, delays, and fee shifts wrecking havoc on not only the passengers, but also the Nairobi government.

Digital Matatus was launched in an effort to address some of these shortcomings, according to Sarah Williams, a project director from MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab, “exposing that the city really does have a system and that the government should recognize that system and hope to regulate it.” Jacqueline Klopp, a scholar at the Center for Sustainable Development, echoed Williams’ statement, recognizing “that if there was going to be any kind of improvement of this system in Nairobi, then people would need to be able to see it and visualize it and speak about it as a system.” Local people were central to this project from its inception, with the project directors sending out volunteers on the matatus armed with cell phones and GPS devices to map out the city’s informal routes. Since Nairobi residents were the ones who would benefit from this system the most, it only made sense that this project was a true representation of development-from-below.

On The Atlantic’s City Lab blog, Sarah Williams, director of the Civic Data Design Lab, spoke to the importance of this project in utilizing technology for real social benefit.

When the government does not step in, these informal economies are developed to meet a certain need that the government should be taking care of. That’s exactly what’s happened here. And it’s fascinating to see, because it’s totally driven by need.

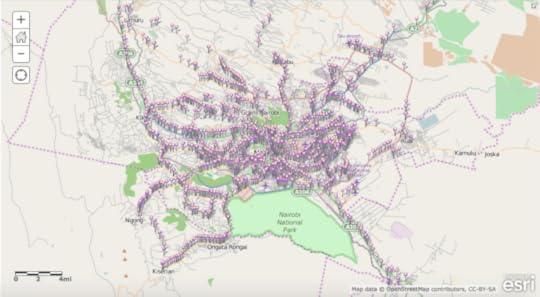

Early last year, these routes were used in efforts to fundamentally restructure the informal transit system in Nairobi, utilizing this knowledge and the digital technologies that created it to design more effective routes and provide better information on routes to citizens. You can see the fruits of their labor above and on their site. The GIS data for this project is available on this site, meaning that researchers can access and utilize this data for their own purposes. Someone has already begun trying to utilize GoogleMaps to map out the matatu routes. Using the files available on the site,I created an interactive version of this map using ArcGIS. You can access this map by clicking on the image below.

The data generated in this project has already been used by some to improve the experience of matatu riders, with some developers using this project as a launchpad for crowdsourcing data on accidents and crime, while others have developed a mobile payment system that calculates the correct payment for a rider’s trip to combat price fluctuations. And, really, this project is about more than just a single map. In a piece written for The Guardian, Klopp insisted that

To us the data and map are not ends in themselves; they should be powerful ways to spur advocacy and support better-informed public dialogue and planning. This is a necessary step towards better public transit, which is critical to building better cities.

In this perspective, this project is just a stepping stone to utilizing digital technologies to improve the daily lives of citizens around the world, not just in Nairobi. And it shows the potential for using African participants to devise solutions to real problems that require innovative solutions.

Follow Digital Matatus on Facebook and Twitter. Also keep track of the latest from the C4D Lab at the University of Nairobi on Twitter. As always, feel free to send me suggestions in the comments or via Twitter of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

April 22, 2015

Goodbye John Shoes Moshoeu

Though Shoes Moshoeu and I never met in real life, when I was young he handed me his name and shared his memories with me. If he played well, the admiration rubbed on me. This is not true, the part about him handing his name down to me, it was given to me by an older soccer player in my village. Growing up people supposed we shared a similar playing style. I was never however disillusioned about the inaccuracies of that supposition. Shoes was always the player that I aspired to be but also knew that this was impossible because to achieve this I would have to on the field dribble, think and make the runs he made. In that department I was more like Doctor Khumalo, skilful and a good passer but lacked the speed at which Shoes moved on the field, gliding across like a dancer on stage with movements that because of their cohesion appear to have been rehearsed far too many times and yet are still confusing to the opponent.

There was also the jittery right foot of Shoes, the swinging waist, appearing detached from his entire body. Watching it, one felt as if they were being deceived in some magic trick, one could never tell what he was about to do. The only similarities that Shoes and I might have shared is the absence of mind, the ability zone out of the match and be somewhere else entirely and then arise, causing mayhem to the defence, when they least expect it. Shoes succeeded in doing this more effectively than I did. For him, it was recharging, even predetermining the movements of the opponent and knowing where to penetrate them. On my part, it was the sheer competence of a player who got tired far too quickly and was lazy to run.

Soccer nicknames are however tricky in that there is sometimes no logical reason in earning them. There is a difference between one loud person calling you Shoes and you actually playing like him.

I had played proudly with the nickname of Shoes attached to me for a long time before I saw Shoes Moshoeu play. Before this, I had mimicked him, crafted his skills, passing, scoring and running from radio commentary. Unlike TV, where one has their own perspective of the match and how players are moving on the pitch, radio offers one the imaginative perspective which is somewhat better I think. One can imagine a player running the entire field for the 90 minutes. Even after a soccer match concludes, radio commentary stays with you, not to be argued against, not to be disputed but to be relished and cherished. The first time I saw Shoes play is still clear as if it had happened yesterday.

My home had no TV and watching TV elsewhere in the three homes that had them in the villages was 50c and this I could not afford. The day I saw Shoes began as all weekend begin in villages, a cock wakes up everyone, mornings are for milking goats and cattle and then playing soccer the whole day whilst keeping an eye on the animals as they graze below the river and ascending the mountain as the day passes.

On the day, we were walking to the mountain in the afternoon to collect cattle and we walked on the main path in front of houses. One of the houses that had a TV, running on battery as there was no electricity then, Chiefs was playing Swallows and they had the door open. I remember two things about this, a door slamming in my face and the unfamiliar sight of Shoes Moshoeu running in the same place, almost backwards. I had not seen much TV and had never seen soccer on TV at all, watching this match, the five minutes before we screamed and the door slammed in our faces, was the first time that I had seen a soccer match. Shoes Moshoeu was not the first player I saw but he is the first player that I watched running. Then I did not know how TV works or the mechanism of TV transmitting, so the sight of Shoes Moshoue, a player that I had imagined from the radio commentary to run like wind, appearing to be running in the same place, almost backwards was disappointing.

The rest of our journey was us screaming about the soccer match, imagining what was happening then, and if someone had scored. Though I never said anything, I thought about the image of Shoes I had made from radio commentary and the image of him on TV, bewildered by the contradiction. I later watched more TV and Shoes had not slowed down, in fact he was running faster, playing as skilfully and cleverly as radio had made me imagine, except now every run and skill was captured on video.

Back in the villages, playing soccer was the only sport at our disposal, you either played soccer or did not play any sport. I played soccer all day, never got hungry, tired. I played as Shoes, never was as good, but nevertheless, the majority of us then watched TV infrequently and inadvertently I became the less better Shoes Moshoeu that people heard about on radio even when though I played my own game.

April 20, 2015

Violent Legacies: How Gang Violence in El Salvador Grew (Helped by the U.S.)

This past March, the murder rate in El Salvador soared to levels not seen in a decade. In just one month, some 481 people were murdered across the country at an average rate of roughly sixteen a day. It isn’t an aberration. Levels of violence have been increasing steadily in the country over the past year, jumping an alarming 56 percent since 2013. All indications suggest the trend will continue beyond the first quarter of 2015.

The immediate cause of this spike in violence appears to be El Salvador’s failed gang truce. Between the spring of 2012 and early 2014, the country enjoyed relative peace following a negotiated agreement between El Salvador’s two main gangs to scale back their bloody war for domestic supremacy. Though not without its critics, the pact between MS-13 and MS-18 did have the virtue of bringing El Salvador a measure of security the state could not otherwise provide.

The truce began to unravel last spring, however, during the country’s presidential elections. Candidates, including Salvador Sánchez Cerén of the incumbent FMLN party, distanced themselves from the truce—likely due to popular unease with revelations that the government had brokered the pact—in favor of other approaches to dealing with the gangs. Since then, battles between MS-13 and MS-18, and between the gangs and state security forces, have increased in both frequency and cost to human life.

Far from a home-grown phenomenon, El Salvador’s gangs—and their counterparts across the region—represent one of the most devastating long-term consequences of American foreign policy in Central America. The story of US involvement in Central America during the Reagan era and beyond is well known. American support of the Contras in Nicaragua and conservative regimes across the region contributed to over a decade of conflict and genocide throughout Central America, the reverberations of which are still powerfully felt today.

Not as frequently recounted in this history is Washington’s wholesale deportation of Latino youth from American prisons to Central America. During the 1980s and early 1990s, young refugees from Central America’s wars fled to the United States. Some, primarily in Southern California, organized into street gangs that offered protection, comradery, and a sense of identity to those migrants whose lives had been turned upside down by conflict at home.

The winding down of civil war in El Salvador coincided with surging anti-immigrant politics in the United States in the early 1990s. In 1996, Congress responded by passing an immigration reform law that, among other things, loosened regulations governing deportations of any immigrant who ran afoul of the law. Suddenly, being busted for something as small as a dime bag was enough to get you shipped back home.

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act opened the floodgates to massive deportations of immigrant Latino youth, especially those who had connections to LA street cliques like MS-13. Tens of thousands of young men would be sent to Central America by the end of the decade, many without any family, friends, or even workable Spanish to rely on. Formal employment was out of the question. Unsurprisingly, many returned to gang life as a matter of survival.

Far from curbing the gang’s growing influence and power, El Salvador’s conservative governments have consistently pursued aggressive policies that strengthened them considerably. Until recently, El Salvador had adopted a militarized mano dura approach to the gangs designed to ensure that members either ended up in prison, or dead. The unintended consequences were profound. Foot soldiers under siege on the outside developed a strong sense of solidarity and common identity, not to mention experience contending with the state. Those that were incarcerated used the opportunity to organize, recruit, and explore other avenues of criminal activity.

Governments in neighboring Honduras and Guatemala have hardly taken a more enlightened approach to the gangs. Honduras originated the “iron fist” policies later adopted by El Salvador while Guatemala has assumed a particularly cavalier attitude towards the gangs. Its posture is best embodied by Plan Escoba (Broom Plan), a short-lived initiative that had no basis in law but which resulted in the indiscriminate arrest of thousands of young men on suspicion of gang affiliation.

Interestingly, nearby Nicaragua has largely escaped the growing influence of gangs, and the violence they bring in tow. A number of factors may explain why. One of the most important, though, is surely the fact that successive Nicaraguan regimes have taken a decidedly more nuanced approach to combating the influence of locally-based and transnational gangs—one of the more remarkable legacies of the Sandinista Revolution.

As José Luis Rocha observes, “The guerilla origin of the National Police was a determining element in the treatment of the gangs…Higher officials of the Nicaraguan police saw young gangsters as new rebels who were experimenting with social and generational conflict.” This view resulted in policies that combined “police work with the activities of churches, NGOs, and schools.”

The current government in San Salvador initially signaled that it planned to adopt a similarly progressive approach even as it rejected negotiating with the gangs directly. President Sánchez Cerén, who barely prevailed in last year’s national election, promised to support grassroots efforts at dealing with the gangs upon taking office. Those hopes met a swift end, however, as soon as the peace pact came undone.

Responding to the growing number of cops murdered by gang violence, the government announced in January that the country’s police were free to shoot suspected mareros (members of the gangs, also known as maras) without consequence while on duty. Using language that evoked the iron-fist policies of previous regimes, Vice President Óscar Ortiz promised that his government would “win this battle, and we’re going to win it by democratic means, but also by applying force that is needed to punish those who need to be punished.”

Meanwhile, El Salvador’s business elites have rapidly mobilized to make sure that the spirit of mano dura continues to animate any government response to the gangs. In early January, the right-wing National Association of Private Enterprise announced that former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani would be consulting them on matters of crime control and security. If Giuliani’s other exploits in the region are anything to go by, a standard menu of “zero tolerance” recommendations that serve market interests to the exclusion of everything else will be presented to El Salvador later this spring.

The Obama administration has also taken a recent interest in El Salvador. In January, an op-ed by Vice President Biden in the New York Times outlined a $1 billion US-led “plan for Central America” that promises to tackle the challenges preventing the El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala from being “middle class, democratic and secure.” The spirit of the White House plan may be laudable, but the details are alarming. The way Biden tells it, Washington is looking to resurrect old programs of action—policies which have had disastrous effects in other Latin American countries—and tailor them to the Central American context.

With its weak government and proactive private interests, not to mention the promise of coming American intervention, El Salvador seems condemned to more violence and social instability in the foreseeable future. Salving the scars of conflict, imperialism and bad policy will demand fresh perspectives and creative thinking. At the moment, though, the only thing on offer is old wine in new bottles. El Salvador deserves better.

Caravana 43: the Non-Official Voice Resisting in Latin America

The refusal to accept, the commitment to resist.

We have heard this story many times. Or at least, one side of it. It began between September 26th and 27th, 2014, in Iguala, Mexico: the story of Ayotzinapa and its 43 missing students. That night, members of the police attacked the buses in which students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa were traveling. They killed six students and bystanders, and handed 43 students to members of the drug cartel Guerreros Unidos, who then disappeared all of them.

Little has changed six months after the attacks. The official investigation is now closed, ruling the disappeared dead. But neither the students, nor their corpses, have been found. The government has ceased the efforts to find them with the lapidary sentence of the Attorney General, Jesús Murillo Karam: “Ya me cansé” [“I am tired”].

But there is a side of the story that is non-official, that you might not have heard about yet. And to tell this story, Caravana 43 was organized. This is a project attempting to “provide an international forum for the parents who have lost their children in a government of systemic violence and impunity.”

In other words, a series of events were organized in the U.S., such as rallies, demonstrations, community forums, protests, and press conferences, to bring the voices of the family members of the students to communities who have heard little, or even nothing, about the events of that night.

The Caravana has visited so far over 34 cities in the United States, traveling with parents and family members of the disappeared, students who survived the attack, advocates, and allies, and will cover in total 40 different cities of the North American country. Divided in three columns (Pacific, Central, and Atlantic regions), the Caravana is looking for aid from local governments, university students and faculty members, and social organizations.

This act of telling their story again has, for the Caravana, a special meaning. It is a meaning that is political because it is an act of resisting against the official version of what happened to the 43 Ayotzinapa students.

The official version of the events, presented by the Attorney General on January 27th of this year, put forward (with “legal certainty”) the thesis according to which the attack had taken place as an ambush ordered by the mayor of Iguala (José Luis Abarca) who feared that the students were traveling from Ayotzinapa to Iguala to disrupt a political event that the mayor’s wife (María de los Ángeles Pineda) was going to hold there.

After the police attack, the 43 students were reportedly killed and burned by the drug cartel Guerreros Unidos in a dump in Cocula, a near town. They allegedly killed them, according to the Attorney General, because rival gangs and cartels had infiltrated the school. Guerreros Unidos wanted revenge.

This last official suggestion, according to which the students were narcos themselves, and thus somehow “had it coming,” sparked the rage of the parents and students of Ayotzinapa, and it still brings tears to the members of the Caravana when they talk about it. In Chicago, María de Jesús Tlatempa Bello, mother of José Eduardo Bartolo Tlatempa, even refused to repeat these “official” words out of respect to the students.

Besides highlighting this cruelty and indifference with which the government has treated the families, the family members of the normalistas have also been saying that there is no conclusive evidence to defend the official hypothesis. They accuse the Government of Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto to be concealing information and covering-up the real motives of the disappearance, and the whereabouts of the missing students.

The Government has eclipsed the participation of the 27th Army Battalion, which knew about the attack and did nothing to stop it in the four hours it lasted. The Government has also lied about the findings and the results of their own investigation: they tried to pass 28 remains of corpses as the remains of some of the normalistas, and only accepted their deceit when the parents demanded the intervention of an independent team of forensics from Argentina.

This same forensic team confirmed later that only one of the bone fragments recovered belonged to one of the students. They also shared its doubts about the original place from which this fragment was recovered, since members of the team were not allowed to be present in the process of recovery.

The Caravana has also explained that the research of experts—who have considered the weather, terrain, and evidence conditions of the place where the mass-burning of the bodies supposedly took place—concludes that this thesis is not believable. Testimonies of witnesses state that there is no evidence of a fire of the characteristics needed to burn so many bodies, and that the conditions of plant life surrounding the place have not changed as the Government says they have.

More importantly, perhaps, the parents insist that this modus operandi (the burning of bodies in an open fire) is unprecedented and does not correspond to the way in which drug cartels of the region operate.

Members of the Caravana and protestors joining them have suggested it is necessary to question the role of the U.S. government in this context. They have been questioning the U.S. military aid to the government of Mexico (known as the Mérida Initiative) in the fight against drugs, and the fact that these financial and logistic resources are being used by state forces for actions such as the disappearance of the 43 students.

The U.S. government has recently refused to condemn Mexico and has backed its military aid without acknowledging the damage that this initiative has caused the Mexican people.

Refusing to accept the death of the 43 is not a whim, as Ómar García, a student and survivor of the attacks in Iguala, remarked in Chicago (see in Spanish this interview, or his words in the welcome to the Caravana).

He feels it is a duty to resist the official version because it is full of lies, manipulations, and cover-ups. It is a side of the story that never included the parents and survivors. It is a story based on an investigation held in secrecy, by a government that cannot judge its own deeds, and that refuses to take responsibility for its actions. The Mexican government has been for too long not only connected to the drug traffic in Mexico, but has also persecuted and stigmatized political dissidents like the normalistas in Ayotzinapa.

This is why these acts by the Caravana are acts to narrate, to recount 40 times, in 40 different cities, in Nahuatl, Spanish, and English, the events in Iguala and everything that happened in the following six months. The Caravana constitutes an act of resistance to the lies and contradictions behind the government investigation, and it is specially focused on finding the 43 disappeared.

In this political gesture of refusal it is possible to see much more than the “mere” demand of memory, that is, just the necessity of knowing what happened to the 43 of Ayotzinapa: the family members do not “just” want to know what happen to them, or what is the truth behind their disappearance; they want to find them, alive, wherever they are, in whatever way possible.

The Caravana constitutes an admirable act of political resistance. By claiming that this investigation is illegitimate, and that its results cannot be true, the parents are maintaining that it must then be false, and therefore the students are alive, somewhere, until someone actually finds them death. The official version would explain the mere disappearance of the 43 students (little in number if compared to the 20,000 disappeared in the last decade by the drug cartels). But this version is incapable of explaining the actual circumstances and details of the attack on the 26th of September, the involvement of the police and militaries, the cover-ups, the silence, or the involvement of the U.S.

Thus, the family members of the 43 are traveling through the United States to also demand an answer about these circumstances, an involvement of the official forces in the events pointing to the U.S. Government through the Mérida Initiative.

It is precisely this questioning what bring this particular struggle at the forefront of a battle and an inquiry that is not only Mexican, but Latin American. The question about the Plan Mérida is also the question about the Plan Colombia, or the Plan Central America.

It is our duty to resist with the Caravana, that is, to bring the 43, alive, to Ayotzinapa, because, as the parents of the students say, “They were taken alive, and alive we want them back!”

***

The three branches of the Caravana 43 will travel in the following days to Seattle, Las Vegas, Columbus, Washington, Hartford, Boston, and will all meet in New York for four days of collective activities from April 22th. Get involved with your local organization, and give a warm welcome to parents, family members and students in your cities.

For more information please visit http://www.caravana43.com/home.html.

If you come from another African country, you can never become fully South African

The violence strikes at what is at the heart of post-apartheid South African identity. For all the talk of hospitality and “ubuntu,” xenophobic violence is a reflection of how the ruling ANC and most South Africans understand the boundaries of “South African-ness.” As commentator Sisonke Msimang suggests, what binds black and white South Africans together is a kinship based on their shared experience of colonialism and apartheid. Msimang argues that in South Africa,

Foreigners are foreign precisely because they cannot understand the pain of apartheid, because most South Africans now claim to have been victims of the system. Whether white or black, the trauma of living through apartheid is seen as such a defining experience that it becomes exclusionary; it has made a nation of us.

This is similar to a brown or black third-world immigrant trying to penetrate one or other European identity. Try as he might, he can never be fully Swedish, Danish or German. While these northern Europeans may hold an exclusionary, racial view of themselves or their nation as “white,” they share with South Africans an unwillingness to expand the boundaries of their identity. If you come from another African country, you can never become fully South African, even if you become a citizen.

In addition, for black South Africans the anti-apartheid project was framed in the first instance in nationalist terms. And that struggle promised its followers liberation from the poverty, racism, exclusion and inequality that they were experiencing. Yet, most black South Africans have experienced nothing of the sort since 1994. All that their political leaders can offer them now is chauvinism.

This is a postcolonial problem and South Africa is not exceptional. Recall the mass expulsions between Nigeria and Ghana of emigrants from both countries in the 1980s, Uganda’s ejection of Asians, the struggle over Ivoirite that broke Cote d’Ivoire apart for a while or the way the Kenyan state has mistreated its Somali citizens since independence. The specifics in South Africa may be different, but the ways in which we respond follow a same pattern. The problems of South Africa since 1994 are rooted in its unsatisfactory political settlement, in which the enormity of the problems it inherited is papered over by feel-good politics and the neoliberal course it has embarked on since. But like many other African states, we choose instead to discharge our anger on easy scapegoats: those we deem foreigners.

Read more here.

April 18, 2015

Interview With Alberto Muenala, Director of the First-Ever Kichwa Feature-Length Film

But Quechua and its regional variants have been a common point between various indigenous groups in different areas of South America since at least the 5th century AD, long before the Inca expansion. From there, it evolved into different, mostly intelligible forms, spoken across a region that corresponds to what is now known as Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia, southern Colombia and northern Argentina.

When the Spanish conquered the region, their religious men learnt and used Quechua to convert the locals into Catholicism. But, after 1781, when Tupac Amarú II tried and failed to rebel against Colonial powers and their treatment of indigenous people in Peru, the Spanish rulers banned any manifestation of indigenous culture, including their languages.

Still, Quechua managed to survive and, currently, about ten million people around the world are native speakers. Nonetheless, even though variants of Quechua are recognized as official national languages in Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia (and a regional official language in Colombia), many of its speakers worry it will fade away among the cultural hegemony of Spanish and English. Yet, many are resisting.

Recently, I had the pleasure to meet Alberto Muenala, an Indigenous and Ecuadorian filmmaker from Otavalo. He recently directed KILLA ÑAWPUMUKUN (Before Moonrise), the first ever feature-length movie done in Kichwa, the variant of Quechua spoken in Ecuador. KILLA, as the movie is simply known, is acted in both Kichwa and Spanish, and is an action story dealing with identity, loyalty and the tension between industrial development, tradition and the protection of the environment.

Muenala and I spoke in The Bronx (a stronghold of Quechua speakers in New York City) and then on email about his language, his culture and his work as a Kichwa filmmaker:

Why did you make KILLA?

The necessity to manifest our own experiences, and to walk our culture, brought us to reflect, through cinema, this current history of the peoples and nationalities of Ecuador. We know that cinema is one of the most powerful tools out there and that we can use it to open the doors so people can get to know our culture, our social issues and, most importantly, so Kichwa doesn’t disappear as an indigenous language of the people of the Andes.

How do you see the state of Quechua cinema in Ecuador and elsewhere?

After the big uprising of 1990 and 1992, in Ecuador, indigenous people were made visible, not only with their political struggle, but also by their audiovisual productions. The latter helped to create awareness on the process of indigenous peoples. Since then, audiovisual production has been an essential tool for the alternative communication of the various peoples and nationalities. That’s why we already have documentary, fictional and experimental films.

Are there any networks for Quechua Filmmakers?

There is no network for Quechua filmmakers at a Latin American level, but we do have a series of connections in Ecuador, grouping around 50 collectives, dedicated to different kinds of productions within the different peoples and nationalities.

What obstacles have you found as a Kichwa filmmaker?

The biggest has been the economical aspect. While it’s true that there are many collectives and that each of them has at least a minimal budget and equipment, there is no production company interested in permanently producing with Kichwa filmmakers. After many years of encounters between filmmakers from the different indigenous peoples and nationalities, we managed to introduce a proposal for the creation of new ways to support Kichwa cinema. Two months ago, CNCINE (Ecuador’s government institute for cinema) approved our proposal, which we hope will allow us to grow in the future. But the path to achieve mass production is still long.

Why do you think there hasn’t been a Kichwa film yet?

It’s a question of processes, of maturity, of will. KILLA comes in a moment in which there are many young filmmakers, willing to work on cinema, willing to join a collective effort, willing to overcome petty differences that did not allowed for intercultural work. With all of this is behind us, many Kichwa collectives got together and invited non-Kichwa filmmakers – which is something that doesn’t happen from the other side – and in this way we managed to create an intercultural production team. We achieved to work as a collective, and the positive results are visible in the movie.

KILLA is in its postproduction stage and Muenala has set up a Kickstarter campaign to help fund it. You can go here to support it. The campaign will be open until Monday, April 20th, 2015.

Weekend Music Break No.70

The Weekend Music break is here! Check out a round up of tunes and visuals that caught our ears and eyes at Africa is a Country headquarters this week!

Kicking things off, AIAC contributor Blitz the Ambassador has a new video for his tune Juju Girl.

French-Cuban Hip Hop Son twins Ibeyi are making their rounds in North America, and they seem to be having fun doing it!

Afrikan Boy celebrates his trans-continental identity on M.I.A. (Made in Africa).

Brazilian pop-electronic artist Silva shoots a beautiful portrait of Luanda.

Jneiro Jarel is a Viberian. I’m not sure what that is, but I’m liking it!

Busy Signal asks “What If” with impressive lyrical prowess! h/t @rishibonneville

Keeping it in the Caribbean, Champeta artist Mr. Black has a video and musical ode to the colorful sound-systems from the Caribbean coast of Colombia.

It’s been a heavy week in South Africa. So, let’s let Aero Manyelo and his fellow revelers lift us up with some Kwaito party vibes.

Afropop Worldwide shares a Benin roots-pop primer. Included is this interestingly shot video from Norberka.

And finally, Rihanna launches a discussion piece for your Saturday night dinner conversations

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers