Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 351

April 17, 2015

Fresh Eyes: KB Mpofu’s moments of intimacy

We head to Zimbabwe for the continuation of our Fresh Eyes series. Based in Bulawayo, KB Mpofu is a self-taught photographer who shoots portraits, fashion editorials and NGO work.

With portraits in particular, the camera itself has a presence which heightens the intensity of the interplay between photographer and photographed. This is a delicate relationship to manage and it can manifest in myriad ways, not all of them pleasant. When viewing Mpofu’s work, the emotional nature of his photographic process reveals itself in the expressions of his subjects. Whether capturing moments of introspection or the everyday, Mpofu elicits a prevailing intimacy from the people he photographs. He memorializes his subjects in bouts of meditative calm as the light lays upon them.

In his own words:

My choice of subjects mostly comes from an instinctive place, resulting in some candid moments. I always back my instincts to see spontaneous photo opportunities around me. I am fascinated by the contrast between light and darkness and how it can be used to create a sense of anonymity. Lately I have been drawn into portraiture work that captures mood through light and composition.

For more of KB Mpofu’s work visit http://kbmpofu.com/

April 16, 2015

Photo of the Day: What value do we place on African lives?

Today for the first time since Mandela was freed, I am ashamed to be a South African. All the years of pride in my birthplace have been replaced with loss and disbelief. The heroes our soil created who believed in freedom and equality regardless of anything else — race, gender, religion, creed and origin — Lilian Ngoyi, Steve Biko, Oliver Tambo, Chris Hani, Ruth First, Nelson Mandela, Robert Sobukwe, Walter and Albertina Sisulu, Braam Fischer, Albert Luthuli, among the many must be weeping silently in their graves. How can it be that blood we are shedding flows from people of Africa — the Congolese, the Mozambicans, the Zimbabweans, the Malawians and the Somalis. How did we get to this point where we kill and attack other Africans on the basis of origin?

The letter that I want to write to my sister’s unborn child, whose father is Mozambican, is that I am sorry that I did nothing. That I did not toyi toyi outside parliament demanding that the President take action and that King Zwelithini publicly condemn those who were killing and stealing in his name. That while I admired how the world responded to Je suis Charlie, I could not create the same anger and protest for the students in Garissa, let alone the African foreigners in South Africa. That all I could do was condemn the atrocity among friends and family but that I could not stand up for her like the heroes before me had stood up for me. That as South Africans we had become so numb to violence that another African life killed violently or removed forcibly was not as concerning for us as getting tickets to the One Direction concerts were or berating Eskom for their failure to provide artificial light while our internal candle had been snuffed out. That I did not say to the ANC women’s league ‘for goodness sake where are you? What are you doing while thugs kill and steal from people and chase mothers carrying their babies? You were there for Reeva Steenkamp when her family needed you most but where are you now when your country and its daughters and her children need you even more?’ That I did nothing except pray, pray that even though my uncle Thekiso Matima and other noble MKs had been willing to risk their lives so that I could be free, there was nothing I could do for my cousins from Somalia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Angola who were being attacked simply because they were not from South Africa.

What humanity is there in killing and chasing away our own brothers and sisters? What is the value we place on African lives?

Achille Mbembe writes about Xenophobic South Africa

“Afrophobia”? “Xenophobia”? “Black on black racism”? A “darker” as you can get hacking a “foreigner” under the pretext of his being too dark — self hate par excellence? Of course all of that at once! Yesterday I asked a taxi driver: “why do they need to kill these “foreigners” in this manner?”. His response: “because under Apartheid, fire was the only weapon we Blacks had. We did not have ammunitions, guns and the likes. With fire we could make petrol bombs and throw them at the enemy from a safe distance”. Today there is no need for distance any longer. To kill “these foreigners”, we need to be as close as possible to their body which we then set in flames or dissect, each blow opening a huge wound that can never be healed. Or if it is healed at all, it must leave on “these foreigners” the kinds of scars that can never be erased.

I was here during the last outbreak of violence against “these foreigners”. Since then, the cancer has metastized. The current hunt for “foreigners” is the product of a complex chain of complicities — some vocal and explicit and others tacit. The South African government has recently taken a harsh stance on immigration. New, draconian measures have been passed into law. Their effects are devastating for people already established here legally. A few weeks ago I attended a meeting of “foreign” staff at Wits University. Horrific stories after horrific stories. Work permits not renewed. Visas refused to family members. Children in limbo in schools. A Kafkaian situation that extends to “foreign” students who entered the country legally, had their visas renewed all this time, but who now find themselves in a legal uncertainty, unable to register, and unable to access the money they are entitled to and that had been allocated to them by Foundations. Through its new anti-immigration measures, the government is busy turning previously legal migrants into illegal ones.

Chains of complicity go further. South African big business is expanding all over the Continent, at times reproducing in those places the worse forms of racism that were tolerated here under Apartheid. While big business is “de-nationalizing” and “Africanizing”, poor black South Africa and parts of the middle class are being socialized into something we should call “national-chauvinism”. National-chauvinism is rearing its ugly head in almost every sector of the South African society. The thing with national-chauvinism is that it is in permanent need of scapegoats. It starts with those who are not our kins. But very quickly, it turns fratricidal. It does not stop with “these foreigners”. It is in its DNA to end up turning onto itself in a dramatic gesture of inversion.

I was here during the last “hunting season”. The difference, this time, is the emergence of the rudiments of an “ideology”. We now have the semblance of a discourse aimed at justifying the atrocities, the creeping pogrom since this is what it actually is. An unfolding pogrom to be sure. The justificatory discourse starts with the usual stereotypes — they are darker than us; they steal our jobs; they do not respect us; they are used by whites who prefer to exploit them rather than employing us, therefore avoiding the requirements of affirmative action. But the discourse is becoming more vicious. It can be summarized as follows: South Africa does not owe any moral debt to Africa. Evoke the years of exile? No, there were less than 30,000 South Africans in exile (I have been hit with this figure but I have no idea where it is coming from) and they were all scattered throughout the world — 4 in Ghana, 3 in Ethiopia, a few in Zambia, and many more in Russia and Eastern Europe! So we will not accept to be morally blackmailed by “those foreigners”.

Well, let’s ask hard questions. Why is South Africa turning into a killing field for non-national Africans (to whom we have to add the Bengalis, Pakistanis, and who knows whom next)? Why has this country historically represented a “circle of death” for anything and anybody ‘African’? When we say “South Africa”, what does the term “Africa” mean? An idea, or simply a geographical accident? Should we start quantifying what was sacrificed by Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and others during the liberation struggle? How much money did the Liberation Committee of the Organization of African Unity (OUA) provide to the liberation movements? How many dollars did the Nigerian state pay for South Africa’s struggle? If we were to put a price tag to the destructions meted out by the Apartheid regime on the economy and infrastructures of the Frontline states, what would this amount to? And once all of this has been quantified, shouldn’t we give the bill to the ANC government that has inherited the South African state and ask them to pay back what was spent on behalf of the black oppressed in South Africa during those long years? Wouldn’t we be entitled to add to all these damages and losses the number of people killed by Apartheid armies retaliating against our hosting South African combatants in our midsts, the number of people maimed, the long chain of misery and destitution suffered in the name of our solidarity with South Africa? If black South Africans do not want to hear about any moral debt, maybe it is time to agree with them, give them the bill and ask for economic reparations.

Of course we all see the absurdity of this logic of insularity that is turning this country into yet another killing field for the darker people, “these foreigners”. But it would not be absurd, since the government of South Africa is either unable or unwilling to protect those who are here legally from the ire of its people, to appeal to a higher authority. South Africa has signed most international conventions, including the Convention establishing the International Penal Tribunal in The Hague. Some of the instigators of the current “hunting season” are known. Some have been making public statements inciting hate. Is there any way in which we could think about referring them to The Hague? Impunity breeds impunity and atrocities. It is the shortest way to genocide. If these perpetrators cannot be brought to book by the South African State, isn’t it time to get a higher jurisdiction to deal with them?

Finally, one word about “foreigners” and “migrants”. No African is a foreigner in Africa! No African is a migrant in Africa! Africa is where we all belong, notwithstanding the foolishness of our boundaries. No amount of national-chauvinism will erase this. No amount of deportations will erase this. Instead of spilling black blood on no other than Pixley ka Seme Avenue (!), we should all be making sure that we rebuild this Continent and bring to an end a long and painful history — that which, for too long, has dictated that to be black (it does not matter where or when), is a liability.

April 15, 2015

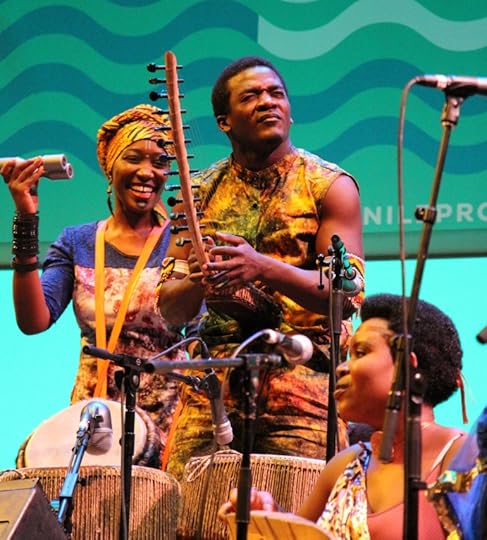

The Nile Project wants to unite a region and overcome ‘World Music’ cliches

The Nile Project sounds like a natural unit—timbres balanced and songs carefully arranged—you can easily forget what a strange union this is, that is until you watch them tune. That’s when Kasiva Mutua, a percussionist from Kenya, starts pouring water on her drum skins to lower the tone while Mohamed Abo Zekry presses his ear to the body of his oud so he can match the tuning of the paired strings. The Ethiopian saxophonist twists his mouthpiece and Steven Sogo of Burundi adjusts the wooden pegs that shift the pitch of the umuduri—a single metal string on a bow affixed with resonating gourds. It is quite a sight, and it reminds you that this isn’t just any band. Founded by Egyptian ethnomusicologist Mina Girgis and Ethiopian-American singer Meklit Hadero, The Nile Project is a collaboration of musicians from around the Nile River Basin that aims to promote dialogue about water politics through performance and education. Just getting their instruments in tune is the first step in that conversation, one that the group’s founders hope will continue beyond the concert hall.

As the show begins I am struck by the lack of ego on stage, each player contributing just enough sound and personality to fill out the texture and no more. With twelve people from seven countries sharing a stage, that is no small feat, and in a way, this is what is most impressive about the Nile Project—not the fact that they can bring together an oud virtuoso and a Burundian singer—but that both those people can leave enough sonic space for us to appreciate the other. With each member coming forward to lead a different song, the concert at times feels like a variety show of styles from the region. This format plays perfectly to the ‘world music’ appetite of an American audience—the fact is that most listeners can’t sit through an entire evening of Egyptian classical music—but it also highlights the diversity of the region. Spanning as it does the Mediterranean world and the Great Lakes of East Africa, the Nile Basin defies any and all generalizations of what ‘African Music’ might be. It also ignores the assumed divide between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, and not simply by their resident’s co-presence on stage. The Nile Project musicians have taken the time to learn each other’s styles, and even each other’s instruments: Hani Bedair, the Egyptian percussionist will slide over at times to play Ugandan hand drums and Sophie Nzayisenga has a special Rwandan harp tuned for playing in the Ethiopian modal system.

Image Credit: Marié Abe

I have to admit that when I first saw the group I was a little skeptical of its idealistic message and sweeping musical fusion. But I quickly realized that this isn’t the kind of surface level fusion that starts with a question of: “wouldn’t it be cool if we combined x and y?” The Nile Project begins with a geographic fact: a river that touches eleven countries on its journey to the sea. That reality offers not only a historical basis for collaboration, but also a social imperative for cooperation: several of these countries are engaged in disputes over water issues. The Nile Project’s founders don’t claim that they will resolve these conflicts through music alone, but they see real value in the sharing of songs and stages as an opening for a broader exchange. That I can believe, especially after watching the group’s rich and joyful performance. When one of the founders, Maklit Hadero of Ethiopia, addresses the audience before a song, she asks: “Can you tell how much we enjoy each other?” Then she adds—as if there is any doubt—“its real.”

Football’s messenger is no more

If Maradona is football’s god, then Eduardo Galeano wrote football’s holy book. The Uruguyan (who also had good politics: “I don’t believe in charity. I believe in solidarity. Charity is so vertical. It goes from the top to the bottom. Solidarity is horizontal. It respects the other person. I have a lot to learn from other people”) passed away this week. Also known as Football is a Country’s patron saint, he wrote mostly about football before television. Go well, great writer. In the meantime, go read our countryman Gary Younge’s account of his meeting with football’s messenger here. Then read my favorite entries, which I copied, from Soccer in Sun and Shadow below.

***

The Opiate of the People

How is soccer like God? Each inspires devotion among believers and distrust among intellectuals. In 1902 in London, Rudyard Kipling made fun of soccer and those who contented their souls with “the muddied oafs at the goals.” Three quarters of a century later in Buenos Aires, Jorge Luis Borges was more subtle: he gave a lecture on the subject of immortality on the same day and at the same hour that Argentina was playing its first match in the 1978 World Cup.

The scorn of many conservative intellectuals comes from their conviction that soccer worship is precisely the superstition people deserve. Possessed by the ball, working stiffs think with their feet, which is entirely appropriate, and fulfill their dreams in primitive ecstasy. Animal instinct overtakes human reason, ignorance crushes culture, and the riffraff get what they want.

In contrast, many leftist intellectuals denigrate soccer because it castrates the masses and derails their revolutionary ardor. Bread and circus, circus without the bread: hypnotized by the ball, which exercises a perverse fascination, workers forget who they are and let themselves be led about like sheep by their class

enemies.

In the River Plate, once the English and the rich lost possession of the sport, the first popular clubs were organized in railroad workshops and shipyards.

Several anarchist and socialist leaders soon denounced the clubs as a maneuver by the bourgeoisie to forestall strikes and disguise class divisions. The spread of soccer across the world was an imperialist trick to keep oppressed peoples trapped in an eternal childhood.

But the club Argentinos Juniors was born calling itself the Chicago Martyrs, in homage to those anarchist workers, and May 1 was the day chosen to launch the club Chacarita at a Buenos Aires anarchist library. In those first years of the twentieth century, plenty of left-leaning intellectuals celebrated soccer instead of repudiating it as a sedative of consciousness. Among them was the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, who praised “this open-air kingdom of human loyalty.”

***

Blacks

In 1916 in the first South American championship, Uruguay creamed Chile 4–0. The next day, the Chilean delegation insisted the match be disallowed “because Uruguay had two Africans in the lineup.” They were Isabelino Gradín and Juan Delgado. Gradín had scored two of the four goals.

Gradín was born in Montevideo, the great-grandson ofslaves. He was a man who lifted people out of their seats when he erupted with astonishing speed, dominating the ball as easily as if he were walking. He would drive past the adversaries without a pause and score on the fly. He had a face like the holy host and was one of those guys no one believes when they pretend to be bad.

Juan Delgado, also a great-grandson ofslaves, was born in the town of Florida, in the Uruguayan countryside. Delgado liked to show off by dancing with a broom at Carnival and with the ball on the field. He talked while he played, and he liked to tease his opponents: “Pick me that bunch of grapes,” he’d say as he sent the ball high. And as he shot he’d say to the keeper, “Jump for it, the sand is soft.”

Back then Uruguay was the only country in the world with black players on its national team.

***

Andrade

Europe had never seen a black man play soccer.

In the 1924 Olympics, the Uruguayan José Leandro Andrade dazzled everyone with his exquisite moves. A midfielder, this rubber-bodied giant would sweep the ball downfield without ever touching an adversary, and when he launched the attack he would brandish his body and send them allscattering. In one match he crossed half the field with the ballsitting on his head. The crowds cheered him, the French press called him “The Black Marvel.”

When the tournament was over, Andrade spent some time hanging around Paris as errant Bohemian and king of the cabarets. Patent leather shoes replaced his whiskery hemp sandals from Montevideo and a top hat took the place of his worn cap. Newspaper columns of the time praised the figure of that monarch of the Pigalle night: gay jaunty step, oversized grin, half-closed eyes always staring into the distance. And dressed to kill: silk handkerchief, striped jacket, bright yellow gloves, and a cane with a silver handle.

Andrade died in Montevideo many years later. His friends had planned several benefits for him, but none of them ever came off. He died of tuberculosis, in utter poverty.

He was black, South American, and poor, the first international idol ofsoccer.

***

Leônidas

He had the dimensions, speed, and cunning of a mosquito. At the ’38 World Cup a journalist from Paris Match counted six legs on him and suggested black magic was responsible. I don’t know if the journalist noticed, but Leônidas’s many legs had the diabolical ability to grow several yards and fold over or tie themselves in knots.

Leônidas da Silva stepped onto the field the day Brazilian great Arthur Friedenreich, already in his forties, retired. Leônidas received the scepter from the old master. It wasn’t long before they named a brand of cigarettes and a candy bar after him. He got more fan letters than a movie star; the letters asked him for a picture, an autograph, or a government job.

Leônidas scored many goals, but never counted them. A few were made from the air, his feet twirling, upside down, back to the goal. He was skilled in the acrobatics of the chilena, which Brazilians call the “bicycle.”

Leônidas’s goals were so pretty that even the goalkeeper would get up and congratulate him.

***

Didi

The press named him the best playmaker of the 1958 World Cup.

He was the hub of the Brazilian team. Lean body, long neck, poised statue of himself, Didi looked like an African icon standing at the center of the field, where he ruled. From there he would shoot his poison arrows.

He was a master of the deep pass, a near goal that would become a real goal on the feet of Pelé, Garrincha, or Vavá, but he also scored on his own.

Shooting from afar, he used to fool goalkeepers with the “dry leaf”: by giving the ball his foot’s profile, she would leave the ground spinning and continue spinning on the fly, dancing about and changing direction like a dry leaf carried by the wind, until she flew between the posts precisely where the goalkeeper least expected.

Didi played unhurriedly. Pointing at the ball, he would say: “She’s the one who runs.”

He knew she was alive.

***

Eusebio

He was born to shine shoes, sell peanuts, or pick pockets. As a child they called him “Ninguém”: no one, nobody. Son of a widowed mother, he played soccer from dawn to dusk with his many brothers in the empty lots of the shantytowns.

He set foot on the field running as only someone fleeing the police or poverty nipping at his heels can run. That’s how he became champion of Europe at the age of twenty, sprinting in zigzags. They called him “The Panther.”

At the World Cup in 1966 his long strides left adversaries scattered on the ground, and his goals, from impossible angles, set off cheers that never ended.

Portugal’s best player ever was an African from Mozambique. Eusebio: long legs, dangling arms, sad eyes.

***

Goal by Pele

It was 1969. Santos was playing Vasco da Gama in Maracanã Stadium. Pelé crossed the field in a flash, evading his opponents without ever touching the ground, and when he was about to enter the goal along with the ball he was tripped.

The referee whistled a penalty. Pelé did not want to take it. A hundred thousand people forced him to, screaming out his name.

Pelé had scored many goals in Maracanã. Prodigious goals, like the one in 1961 against Fluminense when he dribbled past seven defenders and the keeper as well. But this penalty was different; people felt there was something sacred about it. That’s why the noisiest crowd in the world fellsilent. The clamor disappeared as if obeying an order: no one spoke, no one breathed. All of a sudden the stands seemed empty and so did the playing field. Pelé and the goalkeeper, Andrada, were alone. By themselves, they waited. Pelé stood by the ball resting on the white penalty spot. Twelve paces beyond stood Andrada, hunched over at the ready, between the two posts.

The goalkeeper managed to graze the ball, but Pelé nailed it to the net. It was his thousandth goal. No other player in the history of professional soccer had ever scored a thousand goals.

Then the multitude came back to life and jumped like a child overjoyed, lighting up the night.

***

Pele

A hundred songs name him. At seventeen he was champion of the world and king of soccer. Before he was twenty the government of Brazil named him a “national treasure” not to be exported. He won three world championships with the Brazilian team and two with the club Santos. After his thousandth goal, he kept on counting. He played more than thirteen hundred matches in eighty countries, one after another at a punishing rate, and he scored nearly thirteen hundred goals. Once he held up a war: Nigeria and Biafra declared a truce to see him play.

To see him play was worth a truce and a lot more. When Pelé ran hard, he cut right through his opponents like a hot knife through butter. When he stopped, his opponents got lost in the labyrinths his legs embroidered. When he jumped, he climbed into the air as if it were a staircase. When he executed a free kick, his opponents in the wall wanted to turn around to face the net, so as not to miss the goal.

He was born in a poor home in a far-off village, and he reached the summit of power and fortune where blacks were not allowed. Off the field he never gave a minute of his time and a coin never fell from his pocket. But those of us who were lucky enough to see him play received alms of extraordinary beauty: moments so worthy of immortality that they make us believe immortality exists.

***

Goal by Maradona

It was 1973. The youth teams of Argentinos Juniors and River Plate were playing in Buenos Aires.

Number 10 for Argentinos received the ball from his goalkeeper, evaded River’s center forward, and took off. Several players tried to block his path: he put it over the first one’s head, between the legs of the second, and he fooled the third with a backheel. Then, without a pause, he paralyzed the defenders, left the keeper sprawled on the ground, and walked the ball to the net. On the field stood seven crushed boys and four more with their mouths agape.

That kid’s team, the Cebollitas, went undefeated for a hundred matches and caught the attention of the press. One of the players, “Poison,” who was thirteen, declared, “We play for fun. We’ll never play for money. When there’s money in it, everybody kills themselves to be a star and that’s when jealousy and selfishness take over.”

As he spoke he had his arm around the best-loved player of all, who was also the shortest and the happiest: Diego Armando Maradona, who was twelve and had just scored that incredible goal. Maradona had the habit ofsticking out his tongue when he was on the attack. All his goals were scored with his tongue out. By night he slept with his arms

around a ball and by day he performed miracles with it. He lived in a poor home in a poor neighborhood and he wanted to be an industrial engineer.

***

Havelange

In 1974, after a long climb, Jean-Marie Faustin Goedefroid de Havelange reached FIFA’s summit. And he announced: “I have come to sell a product named soccer.”

From that point on, Havelange has exercised absolute power over the world of soccer. His body glued to the throne, Havelange reigns in his palace in Zurich surrounded by a court of voracious technocrats. He governs more countries than the United Nations, travels more than the Pope, and has more medals than any war hero.

Havelange was born in Brazil, where he owns Cometa, the country’s largest bus and trucking company, and other businesses specializing in financial speculation, weapons sales, and life insurance. But his opinions do not seem very Brazilian. A journalist from The Times of London once asked him: “What do you like best about soccer? The glory? The beauty? The poetry? Winning?” And he answered: “The discipline.”

This old-style monarch has transformed the geography ofsoccer and made it into one of the more splendid multinational businesses in the world. Under his rule, the number of countries competing in world championships has doubled: there were sixteen in 1974, and there will be thirty-two as of 1998. And from what we can decipher through the fog around his balance sheets, the profits generated by these tournaments have multiplied so prodigiously that the biblical miracle of bread and fish seems like a joke in comparison.

The new protagonists of world soccer — countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia — offer Havelange a broad base of support, but his power gains sustenance, above all, from his association with several gigantic corporations, Coca-Cola and Adidas among them. It was Havelange who convinced Adidas to finance the candidacy of his friend Juan Antonio Samaranch for the presidency of the International Olympic Committee in 1980. Samaranch, who during the Franco dictatorship had the good sense to wear a blue shirt and salute with his palm extended, is now the other king of world sport. These two manage enormous sums of money. How much, no one knows. They are rather bashful about the subject.

***

The Telecracy

Nowadays the stadium is a gigantic TV studio. The game is played for television, so you can watch it at home. And television rules.

At the ’86 World Cup, Valdano, Maradona, and other players protested because the important matches were played at noon under a sun that fried everything it touched. Noon in Mexico, nightfall in Europe, that was the best time for European television. The German goalkeeper, Harald Schumacher, told the story: “I sweat. My throat is dry. The grass is like dried shit: hard, strange, hostile. The sun shines straight down on the stadium and strikes us right on the head. We cast no shadows. They say this is good for television.” Was the sale of the spectacle more important than the quality of play? The players are there to kick not to cry, and Havelange put an end to that maddening business: “They should play and shut their traps,” he decreed. Who ran the 1986 World Cup? The Mexican Soccer Federation? No, please, no more intermediaries: it was run by Guillermo Cañedo, vice president of Televisa and president of the company’s international network. This World Cup belonged to Televisa, the private monopoly that owns the free time of all Mexicans and also owns Mexican soccer. And nothing could be more important than the money Televisa, along with FIFA, could earn from the European broadcast rights. When a Mexican journalist had the insolent audacity to ask about the costs and profits of the World Cup, Cañedo cut him off cold: “This is a private company and we don’t have to report to anybody.” When the World Cup ended, Cañedo continued as a Havelange courtier occupying one of the vice presidencies of FIFA, another private company that

does not have to report to anybody.

Televisa not only holds the reins on national and international broadcasts of Mexican soccer, it also owns three first-division clubs: América, the most powerful, Necaxa, and Atlante.

In 1990 Televisa demonstrated the ferocious power it holds over the Mexican game. That year, the president of the club Puebla, Emilio Maurer, had a deadly idea: Televisa could easily put out more money for the exclusive rights to broadcast the matches. Maurer’s initiative was well received by several leaders of the Mexican Soccer Federation. After all, the monopoly paid each club a little more than a thousand dollars, while amassing a fortune from selling advertising.

Televisa then showed them who was boss. Maurer was bombarded without mercy: overnight, creditors foreclosed on his companies and his home, he was threatened, assaulted, and declared a fugitive from justice, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. What’s more, one nasty morning his club’s stadium was closed without warning. But gangster tactics were not enough to make him climb down from his horse, so they had no choice but to put Maurer in jail and sweep him out of his rebel club and out of the Mexican Soccer Association, along with all of his allies.

Throughout the world, by direct and indirect means, television decides where, when, and how soccer will be played. The game has sold out to the small screen in body and soul and clothing too. Players are now TV stars. Who can compete with their shows? The program that had the largest audience in France and Italy in 1993 was the final of the European Cup Winners’ Cup between Olympique de Marseille and AC Milan. Milan, as we all know, belongs to Silvio Berlusconi, the czar of Italian television. Bernard Tapie was not the owner of French TV, but his club, Olympique, received from the small screen that year three hundred times more money than in 1980. He lacked no motive for affection.

Now millions of people can watch matches, not only the thousands who fit into the stadiums. The number of fans has multiplied, along with the number of potential consumers of as many things as the image manipulators wish to sell. But unlike baseball and basketball, soccer is a game of continuous play that offers few interruptions for showing ads. The one halftime is not enough. American television has proposed to correct this unpleasant defect by dividing the match into four twenty-five minute periods–and Havelange agrees.

***

The 1990 World Cup

Nelson Mandela was free, after spending twenty-seven years in prison for being black and proud in South Africa. In Colombia the left’s presidential candidate Bernardo Jaramillo lay dying and from a helicopter the police were shooting drug trafficker Rodríguez Gacha, one of the ten richest men in the world. Chile’s badly wounded democracy was recuperating, but General Pinochet, at the head of the military, was still keeping an eye on the politicians and reining in their every step. Alberto Fujimori, riding a tractor, was beating Mario Vargas Llosa in the Peruvian elections. In Nicaragua, the Sandinistas were losing that country’s elections, defeated by the exhaustion wrought by ten years of war against invaders armed and trained by the United States, while the United States was beginning a new occupation of Panama following the success of its twenty-first invasion of that country.

In Poland labor leader Lech Walesa, a man of daily mass, was exiting jail and entering government. In Moscow a crowd was lining up at McDonald’s. The Berlin Wall was being sold off in pieces, as the unification of the two Germanys and the disintegration of Yugoslavia began. A popular insurrection was putting an end to the Ceausescu regime in Romania, and the veteran dictator, who liked to call himself the “Blue Danube of Socialism,” was being executed. In all of Eastern Europe, old bureaucrats were turning into new entrepreneurs and cranes were dragging off statues of Marx, who had no way of saying, “I’m innocent.” Well-informed sources in Miami were announcing the imminent fall of Fidel Castro, it was only a matter of hours. Up in heaven, terrestrial machines were visiting Venus and spying on its secrets, while here on earth, in Italy, the fourteenth World Cup got under way.

Fourteen teams from Europe and six from the Americas took part, plus Egypt, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, and Cameroon, which astonished the world by defeating the Argentine side in the first match and then playing head to head with England. Roger Milla, a forty-year-old veteran, was first drum in this African orchestra. Maradona, with one foot swelled up like a pumpkin, did the best he could to lead his team. You could barely hear the tango. After losing to Cameroon, Argentina drew with Romania and Italy and was about to lose to Brazil. The Brazilians dominated the entire match, until Maradona, playing on one leg, evaded three markers at midfield and set up Caniggia, who scored before you could even exhale.

Argentina faced Germany in the final, just as in the previous Cup, but this time Germany won 1–0 thanks to an invisible foul and Beckenbauer’s wise coaching.

Italy took third place, England fourth. Schillaci of Italy led the list of scorers with six, followed by Skuharavy of Czechoslovakia with five. This championship, boring soccer without a drop of audacity or beauty, had the lowest average scores in World Cup history.

***

Gullit

In 1993 a tide of racism was rising. Its stench, like a recurring nightmare, already hung over Europe; several crimes were committed and laws to keep out ex-colonial immigrants were passed. Many young whites, unable to find work, began to blame their plight on people with dark skin.

That year a team from France won the European Cup for the first time. The winning goal was the work of Basile Boli, an African from the Ivory Coast, who headed in a corner kicked by another African, Abedi Pele, who was born in Ghana. Meanwhile, not even the blindest proponents of white supremacy could deny that the Netherlands’ best players were the veterans Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard, dark-skinned sons of Surinamese parents, or that the African Eusébio had been Portugal’s best soccer player ever.

Ruud Gullit, known as “The Black Tulip,” had always been a full-throated opponent of racism. Guitar in hand, he sang at anti-apartheid concerts between matches, and in 1987, when he was chosen Europe’s most valuable player, he dedicated his Ballon d’Or to Nelson Mandela, who spent many years in jail for the crime of believing that blacks are human.

One of Gullit’s knees was operated on three times. Each time commentators declared he was finished. Out of sheer desire he always came back: “When I can’t play I’m like a newborn with nothing to suck.”

His nimble scoring legs and his imposing stature crowned by a head of Rasta dreadlocks won him a fervent following when he played for the strongest teams in the Netherlands and Italy. But Gullit never got along with coaches or managers because he tended to disobey orders, and he had the stubborn habit of speaking out against the culture of money that is reducing soccer to just another listing on the stock exchange.

***

Maradona

He played, he won; he peed, he lost. Ephedrine turned up in his urinalysis and Maradona was booted out of the 1994 World Cup. Ephedrine, though not considered a stimulant by professional sports in the United States or many other countries, is prohibited in international competitions.

There was stupefaction and scandal, a blast of moral condemnation that left the whole world deaf. But somehow a few voices of support for the fallen idol managed to squeak through, not only in his wounded and dumbfounded Argentina, but in places as far away as Bangladesh, where a sizable demonstration repudiating FIFA and demanding Maradona’s return shook the streets. After all, to judge and condemn was easy. It was not so easy to forget that for many years Maradona had committed the sin of being the best, the crime of speaking out about things the powerful wanted kept quiet, and the felony of playing left handed, which according to the Oxford English Dictionary means not only “of or pertaining to the left hand” but also “sinister or questionable.”

Diego Armando Maradona never used stimulants before matches to stretch the limits of his body. It is true that he was into cocaine, but only at sad parties where he wanted to forget or be forgotten because he was cornered by glory and could not live without the fame that would not allow him to live in peace. He played better than anyone else in spite of the cocaine, not because of it.

He was overwhelmed by the weight of his own personality. Ever since that day long ago when fans first chanted his name, his spinal column caused him grief. Maradona carried a burden named Maradona that bent his back out of shape. The body as metaphor: his legs ached, he couldn’t sleep without pills. It did not take him long to realize it was impossible to live with the responsibility of being a god on the field, but from the beginning he knew that stopping was out of the question. “I need them to need me,” he confessed after many years of living under the tyrannical halo of superhuman performance, swollen with cortisone and analgesics and praise, harassed by the demands of his devotees and by the hatred of those he offended.

The pleasure of demolishing idols is directly proportional to the need to erect them. In Spain, when Goicoechea hit him from behind — even though he didn’t have the ball — and sidelined him for several months, some fanatics carried the author of this premeditated homicide on their shoulders. And all over the world plenty of people were ready to celebrate the fall of that arrogant interloper, that parvenu fugitive from hunger, that greaser who had the insolent audacity to swagger and boast.

The folly of barring pregnant girls from school in Sierra Leone

Pregnant girls are now barred from school in my country Sierra Leone. The government has decided that as schools reopen this week for the first time since the vicious Ebola outbreak that has claimed over 10, 000 lives – and plunged our country into fear, lock downs, economic and emotional pain – pregnant girls should simply stay away. According to Dr. Minkailu Bah, the Minister of Education, Sierra Leone is “not going to legalize teenage pregnancy.”

To justify this baffling policy, the Minister and his supporters, including the Council of School Principals and the Head Teachers Association, have invoked custom (it’s not our “custom” to have pregnant girls in class with other girls who are “innocent”) and morality (pregnant girls are a “bad influence” on other girls). Human rights organizations and advocates like myself have expressed outrage and shock (you can sign my petition on the issue here.) As I asked the Minister on a recent BBC interview, show me one person who has seen a pregnant girl and thought, I also want to get pregnant. There’s simply no evidence of this “influence” – yet so far, nothing has convinced Bah to reconsider his position.

Public policy should not be based on notions of custom and selective applications of moral codes. But it’s worse than that. Let me explain.

One reason why this issue gained attention is because the Ebola crisis played a part. Schools have been closed for almost a year due to the epidemic, and girls have been forced to remain in often over-crowded households that have been under government-mandated lockdowns, sometimes for months on end. Sexual activity likely increased during this time and with no way for girls to access contraceptives, there’s a visible number of pregnant young girls around the country.

The Minister and his supporters have claimed, “If these girls really wanted to learn, they would use condoms or other methods of contraception.” This argument, of course, ignores some basic facts. In Sierra Leone, only 8.2% of females 15-49 years use any method of modern contraceptives. And only about 5% of young people aged 15-24 years said they used a condom the last time they had sex. To make matters worse, during the peak of the Ebola outbreak most of the Reproductive Health Centers were completely shut down, further diminishing an already abysmally limited service. And the use of condoms and other contraceptives often requires negotiation and bargaining clout that most poor young girls simply do not have.

Teenage pregnancy has actually been an issue in Sierra Leone for a long time. One in three girls aged 15-19 in Sierra Leone has been pregnant or had a child at least once. Sierra Leone also has one of the highest rates of early marriages in the world. About 20% of girls between 15-24 years are married by the age of 15, and about half of girls in Sierra Leone are married by the time they reach the legal age of consent (18 years). According to the Population Council analysis of Sierra Leone’s Demographic and Health Survey data in 2008, about 85% of girls in Sierra Leone aged 15-24 years said their first sexual encounter was with a man who was at least ten years older — so many of these sexual encounters are actually statutory rape cases that go unreported. These sets of figures are important because they show that most of what the Minister and his supporters call “immoral behavior” happen within the context of illegal actions committed against the girls; namely child marriage and statutory rape.

In addition, there is the issue of transactional sex. A young girl at a workshop I ran with rural girls in Port Loko, Sierra Leone in April 2013 told me that although she was in school, she helped take care of her younger sibling; whenever she lacked money for basic necessities, she was forced to sell sex. Her story is not unique. Poor girls across the country are often forced to sell sex in exchange for grades, food, jobs and pretty much anything they need from men in positions of power. (For example, Dr. Bah’s former Deputy Education Minister is currently in court for allegedly raping a girl who came to his office to ask for help with school fees.) Yet it’s the girls who are burdened with the moral stigma and condemnation for taking the only option that society often affords them.

Recently some advocates in Sierra Leone — including some prominent gender activists claiming they want to find a middle ground — have called for the creation of an alternative system of education just for pregnant girls. They argue that we can create a special system that takes care of their unique needs. But we already treat pregnant girls as near criminals, shunning them in the community. We have a school system – and economy — that is still struggling to find its feet after the Ebola crisis. Why would anyone believe that the government can create and run a high quality alternative school system? But more importantly — even if such a program were created (as it is in other countries), it should be the girl’s choice to opt into such a system.

Going to school is a fundamental human right guaranteed by the constitution of Sierra Leone and by international law. It’s a right that every child, including pregnant girls, should enjoy – even when it’s inconvenient for someone’s “views on morality.”

The tragedy of this policy extends beyond the impact on individual pregnant girls – it also affects our country. Every year a girl stays in school increases her chance of succeeding in life — of taking care of her family, of immunizing her baby and sending her to school, and of being an active member of a society capable of fighting diseases like Ebola. Every year she stays out of school; it’s twice as likely that she will never return. In a country with one of the highest adult illiteracy rates in the world, we should be busy building bridges for all to access education — instead we are building walls and shutting out hundreds. That has to change.

This is the sound of Cecil John Rhodes falling

Historic moments get a lot of phone camera coverage these days, but I wondered if radio could better capture the atmosphere at the rally to celebrate the removal of the Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town. As the #RhodesMustFall movement said repeatedly, it’s not just about a statue. So I recorded what people were saying and singing.

I took a portable digital recorder to the mass rally outside the Azania House (the renamed administration building occupied by the student activists). The rally featured powerful speeches from students, academics, workers and school children. There was poetry, song, and then the mass surge to upper campus to see old Cecil the statue being taken down and driven off on the back of a lorry.

April 14, 2015

Non-Racialism as Post-Racialism in ‘Soft Vengeance,’ a documentary on Albie Sachs and the New South Africa

One of the more memorable elements in Abby Ginzberg’s documentary Soft Vengeance: Albie Sachs and the New South Africa (2014) is an interview with Henri van der Westhuizen, a former South African military intelligence officer responsible for the placement of the car bomb that would blow off Sachs’ arm in Maputo in 1988. The film was shown last week at the UC Berkeley Law School, where both Ginzberg and Sachs were present. It was revealed during the Q&A that Sachs later learned that the bomb wasn’t intended for him at all. As van der Westhuizen told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, “What’s important was the fact that Albie Sachs was not the target, because Indress Naidoo was the target.” Naidoo, one of the top ANC leaders in exile in Mozambique in this period, was left unscathed.

After giving a talk some years later, Sachs recalled, someone asked him about this revelation. “That’s my bomb!” he joked. The bulk of the questions Sachs fielded during the Q&A concerned his relations with van der Westhuizen: Did the former military operative tell him he was sorry? Would the apology even matter? Was it awkward?

This preoccupation with a disembodied sense of reconciliation mirrors the general narrative structure of the film.

While it would be unfair to overemphasize its brief thoughts on the post-apartheid period, the subtitle does play up this bit — “Albie Sachs and the New South Africa” — and this was the second major theme that emerged from the Q&A. A number of audience members asked Sachs what has happened since the transition in light of the film’s rose-tinted glasses.

He emphasized the significance of Marikana, but not in the way I imagined one would. Rather than discussing the slaughter of 34 striking miners, the most substantial use of force against civilians in South Africa since Sharpeville in 1960, Sachs noted the ANC’s reaction to the massacre. It was viewed by the party as an aberration, he insisted, rather than the norm, distinguishing the post-apartheid government from its authoritarian predecessors. The fact that a government commission was convened and will soon release a report expected to contain open criticism of the ANC and the South African Police Service was his primary evidence.

I couldn’t help but think of Cyril Ramaphosa as a glaring counterexample. Ramaphosa, interviewed repeatedly in the film as one of Sachs’ comrades in the anti-apartheid movement, notoriously emailed Lonmin management, the South African Police Service, and Minerals Minister Susan Shabangu just prior to the shootings. He described the miners as “criminal,” calling for “concomitant action.” Excerpts from these emails, sent while he was a board member at Lonmin, were published in every major newspaper in South Africa.

Hardly an obscure story, mass campaigns calling for Ramaphosa’s arrest were immediate and persist today. Dali Mpofu, the lawyer representing the miners, called for him to be tried at the International Criminal Court. University of Cape Town’s Dean of the Faculty of the Humanities Sakhela Buhlungu subsequently declared, “There is no doubt [in my mind] that the hand of Cyril was there [in mineworkers’ deaths]. Whether he says he was taken out of context, the fact of the matter is that he was involved in the killing of the Marikana mineworkers.”

On December 18, 2012, just shy of three months after the Marikana massacre, Ramaphosa was elected Deputy President of the ANC at the party’s Mangaung conference. He had the full backing of Zuma’s camp, receiving more than six times as many votes as either of his competitors, Mathews Phosa and Tokyo Sexwale. He will surely win the Deputy Presidency in the 2017 elections. All of this is to say that Sachs’ claim that the ANC reacted to Marikana as an aberration is preposterous. Indeed, they’ve done everything in their power to delay the release of the Farlam Commission’s findings.

A second major problem with the framing of the “New South Africa” that emerges in the film’s ending is its deceptive presentation of housing delivery after apartheid. The trope is a common one, with the distribution of free state-provisioned formal homes representing decolonization more generally in countless documentaries. The delivery of a million houses is frequently remembered as a personal promise made by Mandela rather than a key component of the 1994 Housing White Paper, a document produced by the National Housing Forum. (The NHF was dominated by the Urban Foundation, a neoliberal urban policy think tank established by the Anglo-American Corporation’s Harry Oppenheimer in 1977.) Twelve million people have been housed since 1994, we’re informed, with twelve million to go.

The problem with this claim is that according to the Department of Human Settlements, roughly 3.8 million subsidies for new home construction have been released since 1994. With an average household size of 3.1, this yields the 12 million figure featured in the film. But note my careful language: 3.8 million subsidies. The Department of Human Settlements does not keep track of how many homes were actually constructed, and as of 2013, only 1.5 million had actually been filed with the Deeds Registry. In short, it’s quite unlikely that twelve million have actually been housed during this period, and even if this were an accurate figure, it certainly wasn’t through the provision of free formal houses.

Relatedly, the “12 million down, 12 million to go” framing is inaccurate. Rather than a reserve of apartheid-era squatters waiting to be housed by the ANC, an enormous proportion of those awaiting formal homes moved into peri-urban shack settlements after the demise of apartheid. According to the Johannesburg-based Socio-Economic Rights Institute, the first fifteen years of democracy saw a nearly nine-fold increase in the number of informal settlements in South Africa. (While of course we are also concerned here with the population dynamics within each settlement, such data is not readily available.)

This isn’t so perplexing once one considers the urban question in the context of democratization. If apartheid was about coercively controlling urbanization, relocating unwanted black residents to rural bantustans, the lifting of influx controls in 1986 opened the floodgates. From this period on, and especially after 1994, residents of underdeveloped former bantustans converged on cities across the country in search of employment.

The unnuanced picture of post-apartheid South Africa presented in Soft Vengeance does a real disservice to any understanding of the country today. Certainly the real subject of the film — Albie Sachs’ role in the anti-apartheid struggle, his drafting of the 1996 Constitution, and his role until very recently as a justice on the Constitutional Court — receives more in-depth treatment, and for this alone, the film is worth watching.

But the self-congratulatory tone of its narrative of the ANC’s post-apartheid tenure is disingenuous. It’s a triumphalism that derives from an understanding of non-racialism as post-racialism. Rather than land reform, a conscious attempt to reverse apartheid’s geography of relegation, or other concrete socio-economic policies, the film views the transition in terms of an emergent post-racial sociality. The Ubuntu effect, we might call it, emphasizing reconciliation over truth in the TRC.

A rare non-white member of the audience at the screening asked one of the last questions. He told Ginzberg and Sachs that he had been active in the anti-apartheid movement while a student at Berkeley Law in the 80s, and he recalled Desmond Tutu speaking at Berkeley in 1987 to thank students for their involvement.

“I too was intrigued by van der Westhuizen’s apology to you,” he told Sachs. “I was wondering,” he continued, “if he also apologized to any of the non-white people he hurt over the years?”

There is an emergent alternative to this model of non-racialism manifesting as post-racialism. It’s probably a misnomer to call it “emergent,” as it has been there all along, but it is at least rearing its head again. I am talking about the successful campaign and occupation at the University of Cape Town, organized under the slogan #RhodesMustFall.

Of course UCT remains a bastion of elitism and will hardly be the site of any struggle determining the future of South African social relations. But note the rhetoric deployed: for the first time in quite awhile, the question of decolonization is back on the agenda, even if it is being articulated in strange ways, inscribed on the bodies of statues. Against a backdrop of service delivery protests, declining voter turnout, unprecedented strike waves, and the fissure of COSATU, it’s hard to take the reconciliation narrative seriously anymore. What is reconciliation without land reform, without the eradication of the veritable indentured servitude so prevalent in the Western Cape’s farmlands or in the platinum belt?

As calls for civility peter out like a dying gasp, the rhetoric of decolonization is back in the mainstream. From the rise of the Economic Freedom Fighters to the post-Marikana wildcat wave to the debates over DOOKOOM’s “Larney Jou Poes,” South Africa’s black majority is no longer content with an assumed consensus of reconciliation, or what I’ve called non-racialism as post-racialism. Rather than the progressivism it purports to be, this brand of non-racialism is no better than denial.

Flotsam: “How come there ain’t no brothers up on the wall?”

Long before (26 years ago) #RhodesHasFallen, but long after Steve Biko and Black Consciousness, Spike Lee (in Do the right thing) predicted the world historical events at the University of Cape Town last week.

Maboneng on fire

I was retweeting things like “It was only a matter of time #Maboneng” after someone was shot in the head during the eviction protests in Jeppe; that afternoon on my way home from work I was ducking and diving to dodge a burning Bridgestone in the middle of Marshall Street in Johannesburg. Then the following day, news came of David Adjaye’s plans to ‘revitalize’ Hallmark House, the latest Maboneng precinct project.

The redevelopment of the industrial high-rise is the first time that the Tanzanian born, London-raised world-renowned architect has undertaken a project in southern Africa. His firm, Adjaye Associates, has previously done work on the Peace Center in Oslo, the Moscow School of Management, the Msheireb Downtown district in Doha and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C

Gut reaction: This is like watching a bullet coming towards my head in slow motion. The irony is like a ball of frustrated resignation in the pit of my stomach, a similar feeling aroused by ‘ghost squads’ of plainclothes police cruising along Siemert Street pointing automatic rifles out of the open doors of police minibuses at the window washers at intersections. Incidentally, this is the location of the soon-to-be-transformed 17-storey building. At times, the latent trauma of ‘revitalization’ feels like what I imagine a crime novel by Samuel Beckett to be: a surreal, felonious theatre of the absurd centered around questions of economic development, social justice, who-is-most-to-blame and of course, WTF to propose as a solution to human beings trapped in an incomprehensible world subject to any occurrence (like property developers playing Monopoly with homes).

Second reaction after rant against God in the style of Frank Gallagher shouting at the sky: But actually, my Dad is probably going to tell me about this, surreptitiously imploring me to think it’s cool to look at buying one of these properties. He will sell me dreams of Hallmark House’s gym, onsite spa, café, swimming pool and outdoor cinema (part of the Bioscope brand of cinema currently running in Maboneng.) My Mom will chime in: “Units are already on sale from R495 000 (premium apartments are expected to sell for about R2 million) which could totally be an investment for you. Did you watch the budget speech? Do you know the new housing rates eliminate transfer duty on properties below R750 000?”

And part of me will get excited thinking about a rooftop balcony with plants and Smack! microbrewery and Firebird roaster (confirmed tenants in the building, I don’t know what they are but I imagine they are craftily delicious). My imagination carried me away to a fantastical world reminiscent of the Sims-style rendering of the building plans, the kind of place where I can solve all my problems like white women in a romantic movies, by eating a giant tub of ice-cream or drinking tea by the window while wearing an oversized sweater (visual image courtesy of @fastingcannibal).

BUT! What about the people?! How do I upgrade my lifestyle to that dream world, while my neighbors set theirs on fire? Jonothan Liebemann, CEO of Propertuity, which is behind the Maboneng developments, put it best: “Property is a high-impact industry, it changes people’s lifestyles. At Propertuity we approach this industry with ideas that people say are impossible, that are crazy and won’t work.”

It is certainly a crazy idea for me to lament ethical consternation about buying into gentrification to my parents, because they want me to make the most of the opportunities on hand, especially ones they weren’t allowed. It didn’t work when I quoted a previous AIAC article: “But guyssss, the intersection between the individual and the city presented by the Maboneng ‘regeneration project’ (gentrification is too suitable and honest a word)… is a strictly curated experience that takes place along clearly delineated class lines. Class lines that keep some in and most others out.” My folks be like: GET IN THERE!

I then quoted my guy, Achmat Dangor: “It struck me that our history is contained in the homes we live in, that we are shaped by the ability of these simple structures to resist being defiled” and began to explain the irksome feeling I got about this celebrity architect. Describing the influence of having lived in Tanzania, Egypt, Yemen, Lebanon and England (his father was a diplomat), he says things like “I was forced from a very early age to negotiate a wide variety of ethnicities, religions, and cultural constructions. By the time I was 13, I thought that that was normal, and that was how the world was. It gave me a kind of edge in an international global world.” And that this edgy African-British identity also gives him an altered perspective from others in the profession because he is “not just not always looking at the usual references.” The aim of this particular passion project is to “combine an African aesthetic with a contemporary vision“.

It is still not normal to easily negotiate a wide variety of ethnicities, religions, and cultural constructions in Johannesburg away from quirky bubbles like Maboneng, because of the inherent politico-economic inequality in this society. But again Jon-Jon’s got the answer: “Partnering with Mace will allow us to continue disrupting normality in a significant way.” The introduction of the famed starchitect onto this spatial social scene is interesting indicator of norm disruption because he is a pretty high profile example of “African aesthetic with contemporary vision” (homeboy hobnobs Kofi Annan and Barack Obama). It’s a weird city-narrative development that a celebrity architect is going to be designing what could potentially become my home/hotel/history, in the context of gross urban poverty and inequality. (I could just be sour about the artist renderings of the new building only having beige faces in a black city, but Adjaye just gives me the impression that had he been a rock star in the 80s, he would have performed at Sun City during the boycotts.)

Adjaye’s previous buildings have been described by Rowan Moore as:

Works of a realigned world, where the distribution of money and power ignores former distinctions of third and first worlds. They collectively offer the same reorientation as those world maps that dispense with the Eurocentric bias of Mercator’s projection.

Go figure that he would say something like, “you will look at this building and think that it is in some other city, and then you will realize its in Johannesburg; it’s in Africa.” This makes me uncomfortable. Surely my World Class City can do more than superimposing superstarstructures to prove its progression?

It can certainly do more for inclusive development. Journalist Greg Nicholson describes Maboneng as a symbol and a scapegoat during violent protests, given the controversial debate about its impact in the city and the lack of evidence linking Propertuity to the protest – the buildings where evictions are set to take place are far from precinct, and close to the decrepit local men’s hostel.

According to the City, which held a meeting last week with community leaders and police, there are three private companies trying to evict tenants on three different properties, but some community members say eight buildings have received eviction notices. Propertuity has made it clear that the group is not involved in either buying or evicting from the Jeppe buildings. Maboneng has been steadily growing for years, and the hasty actions of copycat developers are leapfrogging off this success. It is similar to the Chinese concept of “dragon head enterprise”. With the leader of the pack having distanced itself for responsibility, those behind these evictions must be identified and held accountable, while riding the inner-city cash-cow by selling dreams to consumers (like my parents, and of course, the market of young/ professional/ creatives wanting an alternative to suburban Johannebsurg.)

There is some synergy between the City’s approach to development and a critique of Adjaye’s previous public projects: “there’s a tendency for the story behind the design to outrun the realization… there is a disconnect between the parts that speak of public life and interaction.” City planners, developers and designers shape the way that homes and histories are constructed (be it colonial structuring or imported Tuscan villas in gated complexes). This protest is a portent of more to come if the planner-designer-developer triad does not do better with the trendy opportunities at hand and take responsibility for marginalized residents by communicating clearly, presenting options for low-cost inner-city housing, and advocating for inclusive development that goes beyond ‘mixed-income’ hotel apartments and international rappers at street festivals because “a relatively contained protest could soon mushroom into another existential problem for Johannesburg.” Surely we have enough of those already.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers