Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 355

April 3, 2015

Will Africa’s Industrial Revolution Be Made in China?

Over the past three decades, consumers have grown used to seeing the “Made in China” label adorning their less expensive purchases. Once China opened its economy to international trade and investment in the 1980s, it did not take long for it to wrest domination of the lower-end manufacturing sector from its East Asian neighbours and flood the world’s high streets with cheap goods.

Low wages were at the heart of China’s success. The majority of the population lived on less than a dollar a day, so businesses had no need to pay high salaries. Combined with high productivity, this enabled them to undercut manufacturers in more advanced economies.

As China has grown wealthier and wages have increased, however, this advantage is eroding. Higher wages render Chinese producers less competitive in low-value, labour-intensive manufacturing, but they are unlikely to want to relinquish control over the lucrative cheap goods market. Higher technology products contain many low technology components and China will need a supply of such inputs as its economy becomes more sophisticated. To whom will it turn to fill its shoes?

Many in Africa are suspicious of China’s growing interest in the continent. Lamido Sanusi, the former governor of Nigeria’s Central Bank has complained that by buying primary commodities from Africa and selling it manufactured goods China is helping to “de-industrialise” the continent. South Africa’s Trade and Industry Minister Rob Davies has suggested that Chinese imports are “replacing products that could be made in South Africa.”

It is possible, however, that China is taking a longer view, and that a major motivation for expanding its African interests is to partner with the continent to build up its low-end manufacturing base.

China does not have to look far to find a precedent for this. Japan once performed China’s role in supplying the world with cheap manufactured products. Eventually some of its East Asian neighbours learned how to make these products themselves and Japanese firms began to outsource labour-intensive manufacturing to Taiwan, Hong Kong and South Korea, where wage demands were lower. As this “flying geese” pattern of development unfurled, these new East Asian tigers climbed up the value chain, leaving the production of cheap goods to Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and China itself.

Like Japan before them, South Korea and others assisted the development of this next group of tiger economies. They began by concentrating their overseas investments in mining and energy to fuel their own manufacturing sectors, only later expanding their portfolio to speed their neighbours’ industrialisation.

By reducing labour costs and improving productivity, China’s similar investments in Africa could pave the way for Chinese firms to relocate production there. China’s initial focus has been on mining and energy, but as wages have risen at home, it has invested heavily in African infrastructure and begun to help develop the continent’s human capital. China has built roads and railways, upgraded ports and airports, expanded telecommunications networks, and implemented multi-country solar and hydropower projects. It has provided capacity building support to regional trade bodies. And it has launched scholarship programmes to take young Africans to China for vocational training. Discussing his plans for an education programme to show African university students how his country developed, the Chinese ambassador to Mozambique recently told the writer Howard French that, ‘We have two aims, to show Mozambicans that they can have big goals – not just to feed themselves, but also to sell what they produce overseas.’

Last year the Chinese Premier Li Keqiang told the African Union that China was planning to move a number of labour-intensive industries to Africa. Justin Lin, an advisor to the Chinese government, has predicted that China will have to export eighty million jobs as its competitiveness in low-end manufacturing weakens, and argued that Africa is the ideal destination for many of these jobs.

Eighty million jobs will not solve all of Africa’s problems, but low-end manufacturing can perform a vital employment-creating function and lay the groundwork for a move higher up the industrial value chain. Even if this is not the motivation for its interest in Africa now, China has little choice. Far more than aid, it is jobs that Africa needs. As Chinese wages continue to increase, it is jobs that Africa will get.

April 2, 2015

Should the African Union Run a Country?

In 2001, the African Union (AU) was established to distance itself from its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which had been formed in 1963 to rid the continent of the “remaining vestiges of colonization and apartheid” and encourage solidarity among African nations. The OAU was corrupt and ineffective however, and the AU claimed a fresh start through a renewed a commitment to economic, political and social development that prioritized the needs of its member states and citizens over leaders. However, despite this expressed mandate, the AU has often been unable or, in some cases, unwilling to get involved in the issues that matter most. These include the precarious political situations in Libya, Zimbabwe, and Côte d’Ivoire. But, more recently, there have been noted shifts in the organization’s behavior, as it seeks an increased role in continental emergencies such as the Ebola crisis and the civil war in South Sudan.

December 2013 saw the start of the deadliest outbreak of Ebola the continent has ever experienced. In response to an increasingly grave situation, the AU began its intervention through the holding of the 1st African Missions of Health Meeting, held by the AU Commission (AUC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) in Luanda, Angola in April 2014. In a follow-up to this meeting, The Peace and Security Council met in Addis Ababa on August 19, 2014 and adopted several protocols as a means of addressing the current crisis. Most importantly, at that meeting the AU authorized the immediate deployment of an AU-led Military-Civil Humanitarian Mission to the affected countries. This meeting also led to the formation of the AU Support to EBOLA Outbreak in West Africa (ASEOWA), comprising of representatives from multiple AU departments, UN agencies, and partners.

The first mission was deployed on December 3, 2014. This mission began with 196 Nigerian health workers who were soon joined by 187 Ethiopian health workers, 81 from the Democratic Republic of Congo and 170 from Kenya. In-country efforts vary but it remains apparent that the efforts on the part of this mission are not evenly spread amid funding challenges, especially regarding the delayed deployment of donor funds. Yet the mission was a concrete step and future plans include the establishment of an African Center for Disease Control, to support efforts at managing epidemics across the continent.

The Ebola crisis is not the only crucial intervention in which the AU is currently involved. Another pressing issue includes the continuing crisis in South Sudan, in which the AU’s role is not without controversy. The AU has not released the findings of the October 2014 Commission of Inquiry into the civil war there, due to concerns that these findings will disrupt the peace process in Addis Ababa. Calls for a full release have intensified following a supposed leak of the report, despite claims on the part of the AU that this document is a fake. However, any claims purported to have been made in this document have serious implications for any future action in Africa’s youngest nation. Along with criticizing the role that the United States, Britain and Norway played in supporting the 2005 peace deal, the draft recommended that the members of the South Sudanese government, prior to the cabinet’s dissolution on July 13, 2014 – including the president and vice-president – not be allowed to participate in the transitional government. Most significantly, it “called for an AU-appointed and UN-backed three-person panel to oversee a five-year transition and the creation of a transnational executive that would place all oil revenue in an escrow account overseen by the African Development Bank” along with the recommendation for the establishment “of an African Oversight Force… that would be under AU command and ‘the overall charge’ of a UN peacekeeping mission.”

Whether or not the AU has the capacity to fully undertake these missions, which would effectively see the organization govern Africa’s newest nation, these situations do set a precedent for its handling of crises on the continent. The Ebola crisis indicates its increasing mandate and willingness to get directly involved in the handling of domestic affairs when they pose significant threats to regional stability. South Sudan suggests that the regional body has the authority to take over governance in a nation that has shown no ability to do so itself. These two, very significant, developments reveal the AU’s attempts to reduce its reliance on foreign entities by separating itself from the “international agenda” and highlight its intentions to take on more of an authoritative role when it comes to regional interventions.

Of particular interest, though, is the nature of these current interventions, as all members can agree that Ebola and South Sudan are humanitarian crises with regional ramifications. However, the AU is often criticized for not acting in situations with significant political salience. So, while I applaud the AU’s efforts and its re-commitment to regional development, the true test of its willingness to engage and “redefine” its current image on the continent, will be its involvement in the more politically tense situations. Until then, these current interventions can only be viewed as deviations from the norm.

Should the African Union run a country?

In 2001, the African Union (AU) was established to distance itself from its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which had been formed in 1963 to rid the continent of the “remaining vestiges of colonization and apartheid” and encourage solidarity among African nations. The OAU was corrupt and ineffective however, and the AU claimed a fresh start through a renewed a commitment to economic, political and social development that prioritized the needs of its member states and citizens over leaders. However, despite this expressed mandate, the AU has often been unable or, in some cases, unwilling to get involved in the issues that matter most. These include the precarious political situations in Libya, Zimbabwe, and Côte d’Ivoire. But, more recently, there have been noted shifts in the organization’s behavior, as it seeks an increased role in continental emergencies such as the Ebola crisis and the civil war in South Sudan.

December 2013 saw the start of the deadliest outbreak of Ebola the continent has ever experienced. In response to an increasingly grave situation, the AU began its intervention through the holding of the 1st African Missions of Health Meeting, held by the AU Commission (AUC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) in Luanda, Angola in April 2014. In a follow-up to this meeting, The Peace and Security Council met in Addis Ababa on August 19, 2014 and adopted several protocols as a means of addressing the current crisis. Most importantly, at that meeting the AU authorized the immediate deployment of an AU-led Military-Civil Humanitarian Mission to the affected countries. This meeting also led to the formation of the AU Support to EBOLA Outbreak in West Africa (ASEOWA), comprising of representatives from multiple AU departments, UN agencies, and partners.

The first mission was deployed on December 3, 2014. This mission began with 196 Nigerian health workers who were soon joined by 187 Ethiopian health workers, 81 from the Democratic Republic of Congo and 170 from Kenya. In-country efforts vary but it remains apparent that the efforts on the part of this mission are not evenly spread amid funding challenges, especially regarding the delayed deployment of donor funds. Yet the mission was a concrete step and future plans include the establishment of an African Center for Disease Control, to support efforts at managing epidemics across the continent.

The Ebola crisis is not the only crucial intervention in which the AU is currently involved. Another pressing issue includes the continuing crisis in South Sudan, in which the AU’s role is not without controversy. The AU has not released the findings of the October 2014 Commission of Inquiry into the civil war there, due to concerns that these findings will disrupt the peace process in Addis Ababa. Calls for a full release have intensified following a supposed leak of the report, despite claims on the part of the AU that this document is a fake. However, any claims purported to have been made in this document have serious implications for any future action in Africa’s youngest nation. Along with criticizing the role that the United States, Britain and Norway played in supporting the 2005 peace deal, the draft recommended that the members of the South Sudanese government, prior to the cabinet’s dissolution on July 13, 2014 – including the president and vice-president – not be allowed to participate in the transitional government. Most significantly, it “called for an AU-appointed and UN-backed three-person panel to oversee a five-year transition and the creation of a transnational executive that would place all oil revenue in an escrow account overseen by the African Development Bank” along with the recommendation for the establishment “of an African Oversight Force… that would be under AU command and ‘the overall charge’ of a UN peacekeeping mission.”

Whether or not the AU has the capacity to fully undertake these missions, which would effectively see the organization govern Africa’s newest nation, these situations do set a precedent for its handling of crises on the continent. The Ebola crisis indicates its increasing mandate and willingness to get directly involved in the handling of domestic affairs when they pose significant threats to regional stability. South Sudan suggests that the regional body has the authority to take over governance in a nation that has shown no ability to do so itself. These two, very significant, developments reveal the AU’s attempts to reduce its reliance on foreign entities by separating itself from the “international agenda” and highlight its intentions to take on more of an authoritative role when it comes to regional interventions.

Of particular interest, though, is the nature of these current interventions, as all members can agree that Ebola and South Sudan are humanitarian crises with regional ramifications. However, the AU is often criticized for not acting in situations with significant political salience. So, while I applaud the AU’s efforts and its re-commitment to regional development, the true test of its willingness to engage and “redefine” its current image on the continent, will be its involvement in the more politically tense situations. Until then, these current interventions can only be viewed as deviations from the norm.

A Closer Look at Mexico’s Drop in Violence

The Institute for Economics and Peace recently issued its 2015 “Mexico Peace Index.” The report assesses Mexico along seven indicators—homicide, violent crime, weapons crime, incarceration, police funding, organized crime, and efficiency of the justice system. Taken together, IEP’s analysis paints a very mixed picture of the country’s security situation. Importantly, the survey strongly suggests that Mexico has experienced a nation-wide drop in homicides since 2012—and an overall increase in peacefulness across the country—even as violent crime spiked significantly during the same period.

Though the report’s authors adopt a cautious tone throughout, the Christian Science Monitor celebrated their findings as confirmation that Mexico’s heavy-handed crime-fighting policies have been a success. “Despite a reputation as a violence-wracked country,” the paper’s editorial board observed, “Mexico has seen the level of homicides and organized crime drop by more than a quarter since 2011. The decline shows that the effort to break up big drug cartels is working. Good news, si?” Actually, not so much.

Its sometimes inconclusive and contradictory data notwithstanding, the report clearly demonstrates the catastrophic consequences of Mexico’s militarized war on drugs. The dip in crime highlighted by the Monitor followed five years of precipitously climbing rates of homicide that correlate almost directly with the presidency of Felipe Calderón, and the US-sponsored Mérida Initiative to combat Mexico’s flourishing narcotics trade. Since 2008, Washington has funneled over a billion dollars in military assistance, “on the theory,” in the words of John Ackerman, “that high-tech helicopters and listening devices [could] solve the problem” of Mexico’s blossoming drug trade.

The Mérida Initiative, known popularly as “Plan Mexico,” was modelled after the American-backed drug war in Colombia. Between 1999 and 2006, the United States contributed billions of dollars and sent hundreds of soldiers to Colombia to help the government there regain control of the country and eliminate security rivals. While “Plan Colombia” has been heavily criticized for contributing to worsening human rights protections and other problems, it has been touted as a Latin American success story—chiefly by those in government.

No surprise, then, that the lessons and approach of Plan Colombia might serve as the blueprint for policymakers concerned with the worsening situation in Mexico. In 2008, Washington signed a security pact with the Calderón administration designed to help the Mexican government fight the drug cartels, strengthen the rule of law and human rights protections, and bring peace and prosperity to the entire country. It did nothing of the sort.

The destruction wrought during the Calderón era (2006-2012) is staggering. In six years at the helm of power, he oversaw a war on drugs that claimed upwards of 100,000 lives, disappeared tens of thousands more, gave life to rash of state-sponsored human rights abuses, and witnessed the spread and diversification of cartel power within and across Mexico’s borders. As Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera has recently noted, “this momentous increase in violence has been accompanied by the widespread use of barbaric, terror-inflicting methods, such as decapitation, dismemberment, car bombs, mass kidnappings, grenade attacks, blockades and the widespread execution of public officials.”

The recent drop in homicides lauded by the Monitor puts Mexico back at 2007 levels—hardly cause for cheer. That year, homicide rates were considerably higher than those measured between 2003 and 2006. Not only that, the security situations in the four Mexican states specifically targeted by Calderón in the Mérida Initiative—Guerrero, Tamaulipas, Sinaloa, and Michoacán—have deteriorated over the past decade. Yet the overall trends, especially with regard to homicide rates, appear positive.

What accounts for the apparent drop in murders across Mexico over the past two years? Some, like the editors at Christian Science Monitor, will be tempted to credit the current president, Enrique Peña Nieto, with steering Mexico away from a bloody precipice towards greater peace and prosperity. They write that “the study supports work by others that forecast less violence in Mexico as recent political reforms kick in, such as changes to the state oil company and in labor laws…Mexicans expect more of their leaders, and the results are starting to show.”

Suggestions that Mexico has fared well since the PRI returned to power under Peña Nieto are simply without credibility. As massive demonstrations protesting state complicity in the disappearance of forty-three students from Ayotzinapa made clear late last year, the government continues to fail its citizenry in key areas, not least security. The IEP index supports this assertion. The percentage of homicides in the country that go unpunished has risen by more than 30 percent over the last decade, a trend that continues under the current regime.

Meanwhile, more than 30,000 disappearances have been registered by the government in the past eight years, with more than 10,000 of them still unaccounted for. Less than 1 percent of these presumably violent crimes are investigated by the state, and not a single person has been sentenced in connection with these cases. The recent discovery of a string of mass graves in the hunt for the missing forty-three has done little to change the general perception that Mexico’s governing institutions are either not able or willing to provide vulnerable citizens with basic public goods. Little wonder, then, that local self-defense groups are sprouting up across the country.

As for political reform, such as the recent privatization of the country’s oil, the jury is still out. Early indicators, though, are not promising. The prying open of Mexico’s oil wealth to private investment—beyond offering wealthy Mexicans and their foreign partners lucrative opportunities to exploit—couldn’t have come at a worse time. With oil prices slumping, and the peso experiencing heavy losses against the dollar, the state-run oil company Pemex posted a $17.7 billion loss in 2014. Far from creating new jobs, the oil reform allowed for the firing of tens of thousands of workers to stanch the bleeding. With no end to this downward slide in sight, further losses will almost certainly result more layoffs.

A more likely explanation for dropping murder and violence rates in Mexico would include a number of factors for consideration. The importance of de-escalating military operations against the cartels cannot be overemphasized. Nor can be the fact that spasms of violence between the drug gangs have resulted in winners and losers, the consolidation of control over trafficking routes, and thus fewer all-out battles for the plaza. Finally, as the IEP report itself notes, available data only represents a sliver of reality. The authors estimate that less than a quarter of all violent crime gets reported to authorities, with violent crimes against women especially underrepresented—only 8 percent of all rapes in Mexico, for example, are officially tabulated by the country’s Executive Secretary of the National System for Public Security.

Whatever accounts for the declining violence in Mexico, the country remains in a deeply precarious spot. Until Mexico experiences real political reform—truly representative politics, institutions that function for the entire polity, and the protection of the country’s resources from predatory capital—the structural forces driving the violence and crime will stay intact and continue to bring harm to large numbers of already vulnerable citizens. Unfortunately for them, as things stand at the moment, prospects for meaningful change appear to be a long way off.

The Audacity of ‘Somali Studies’

The recent #CadaanStudies controversy that pitted a German anthropologist, Dr. Markus Hoehne, against young Somali researchers, students and professionals led by Safia Aidid, a Somali-Canadian doctoral student at Harvard, prompted a frenzied debate about the state and future of Somali studies. The trigger for this controversy stemmed from the absence of any Somalis from the editorial board of a recently created Journal of Somaliland Studies. And amidst the brouhaha, the lack of Somali voices on a journal about Somalia remains one critical issue, which is about much more than Markus Hoehne and Somalia.

The #CadaanStudies discussion ultimately reveals a crucial problematic intrinsic in academic ‘expert’ discourses that marginalize some voices and bodies and privilege others, all the while benefitting professionally from the communities they purport to study.

To be sure, as an academic based in a major American research university whose published scholarship revolves on the Somali people, I found it fascinating that Dr. Markus Hoehne tells us that he “did NOT come across [sic] many younger Somalis who would qualify as serious SCHOLARS- not because they lack access to sources, but because they seem not to value scholarship as such.”

Yet what triggered my intervention here were the condescending remarks that Dr. Hoehne leveled against those who challenged him, with his statement in Somali that translated to “young Somalis should return to their clannish ways once they are done with their critique of his neo-colonial attitudes.” The original Somali in verbatim was “Waan u maaleynayaa, markaad dhameysey hadalkaaga guumaysiga ku sabsan ayaad dib u noqon kartaa qabyaaladda soomaaliyeed iwm.” This crudely expressed attitude is, I think, indicative of a more widespread problem in academic discourse.

Of course, I must note the significant contributions made by white scholars to Somali studies. I applaud and commend the amazing work that some of these produced and produce which continues to shape my own intellectual growth (i.e. Catherine Besteman, Lidwien Kapteijns, Peter Little, etc.)

With that caveat, however, it occurs to me that remarks like Hoehne’s demand that we as established scholars in Somali studies recognize the responsibility we have towards younger generations. Somalists in major research universities in Europe and North America occupy positions where they can play pivotal role in training future generations in this area study. With the devastation that Somali educational institutions have suffered over the last three decades, there is an added urgency to fulfill this obligation. Hoehne was crude and insensitive, but he was not wrong that there could be more Somalis studying Somalia, and it is our collective responsibility to incubate the next generation of experts.

Then, perhaps, we might be able rightly to marginalize a researcher who specializes in Somali studies, who engages in verbal taunts with young Somali-diaspora members, mocking them as ‘activists’ and whose identity, nation and ability he openly disparages.

We can certainly question his judgment. But more importantly we need to take his comments at face value and acknowledge that he is genuinely convinced that most Somalis are incapable to partake in knowledge production, but are fit to be mere informants and audiences for his supremely-located analytical eye.

Clearly, we can also read this thread as exemplar of how some researchers remain clueless to their positionality within research and knowledge production at this beginning of the 21st century. The power disparity that prevails between White European scholars in Somalia (or other countries in the South) and their ‘native subjects’ can either become an integral critical part of the process of knowledge production, with an explicit acknowledgement of how this power shapes the research itself, or it can remain silent, and of course ultimately also shape the research findings with serious implications. The type of knowledge that early European anthropologists whose work aligned with imperial and colonial powers represents the latter, as Edward Said’s work Orientalism, as well as Mahmud Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject cogently demonstrate.

Most relevant for Somalia, I.M. Lewis’s reductionist analysis of Somali clan structures in great part informs the unworkable clan political dispensation and regional fiefdoms that currently characterize Somalia. The International community, with Somali sectarian warlords and politicians, continues to rely on this outdated and problematic understanding of Somali social structures that was produced by British colonial academic experts.

This #CadaanStudies debate also brings to the fore a dominant new type of Somali-expert who is often very distinct from some of the primarily academic Western researchers of yesteryears. Some in this new cadre of researcher-development practitioners use their scholarship and their academic training to marginalize any critical voices. One could argue that this type of researcher-development practitioner can espouse attitudes that are messiah-like towards Somalis. One such researcher commented on a work that I did with a senior White-Canadian scholar as problematic. A key premise of this critique was that my analysis could not be ‘objective’ as I was a Somali and thus emotionally invested in the plight of refugees in Dadaab.

For such ‘expert’ researchers, Somalis cannot and will never amount to more than dependents on neo-missionary handouts. Their lot is reduced to one only known and knowable by PhD-touting young men and women whose expertise is validated as much by their hegemonic and flexible citizenship and their relationship to donor countries as it is by their university credentials. For some in this cadre, Somalis are forever slaves of their primordial ‘tribal’ instincts that I.M. Lews reified.

In such a landscape, we should read this #CadaanStudies discussion as revealing a genuine un-censored portrait of a status–quo that is rarely articulated as explicitly as it is in this thread. So perhaps we need to thank Markus Hoehne for exposing academia’s dirty secrets to the air.

And we should applaud the young Somali students, scholars and professionals who initiated this call to critically question the current state of Somali studies. We, their elders, whether Somali or non-Somali, ought to heed their call and open spaces where all conscious academics and researchers might work productively to paint a richer, fuller picture of the place that some of us call home.

April 1, 2015

Hipsters Don’t Dance Top World Carnival Tunes for March 2015

Hipster’s Don’t Dance are back with their chart for March 2015. Enjoy this round of tunes, and remember to visit the HDD blog for all their great up-to-the-time-ness out of London!

Timaya x Sanko (Remix Feat Destra)

Like all good things sometimes a little spice is need to make something great just a little bit better. Timaya’s Sanko has been the song of the past couple of month’s and the addition of Trinidad’s own Destra makes this song even more so. hopefully this song will be as successful as Timaya’s last Carribean Collaboration with Sean Paul.

Sarkodie x Ojuelegba (Wizkid Cover/Remix)

Even though they sped up the original’s beat to make it sound a tad like dembow, this remix is great. The double time flow of Sarkodie over this laidback thankful song is a great combination.

Edanos x Whine For Me (Feat. Timaya)

Newcomer Edanos teams up with Timaya for this dancehall flavoured piece of afropop. This really could be a cousin to Sanko, which if this is going to be a formula we are happy with. Highlife esque chorus’s with early ninties Taxi Gang esque riddims.

Nidia Minaj x Ne Assim

Jess and Crabbe of Bazzerk records have been releasing Afro-digital dance music for the past couple of years. Their latest release features recent interviewee Nidia Minaj, you really don’t want to miss out on one of the world’s rising stars.

Frenchy Le Boss x Flexing (Feat. Giggs)

Although the grime scene here in the Uk is getting its ovedue shine, the “rap scene’ is also getting interesting again. Here multilingual Frenchy Le Boos (born in Paris, raised in South London) teams up with London mainstay Giggs over the most invasion not produced by invasion beat of all time.

“Black President” – Mpumelelo Mcata (of BLK JKS)’s directorial debut confronts art audiences

In his inaugural project as filmmaker, Mpumelelo Mcata (guitarist of the South African alt-rock group, BLK JKS) steps away from the familiar territory of making music to present us Black President. The film revolves around the Zimbabwean born artist Kudzanai Chiurai whose work divides opinion.

The film is a bold project. What Black President achieves is to document the life of an artist in real time. It has managed in fact, to allow the artist to speak; and in so doing it gives us the rare opportunity of getting a clearer idea of what goes on in his mind – certainly beyond the confines and lofty language of art history and interpretation.

As its central theme, the film has Chiurai’s State of the Nation exhibition. (In it, Chiurai invents a state and gives it a revolutionary and female leader played by the singer Zaki Ibrahim.)

In the hands of it’s own children

In a radio interview before the exhibition, Chiurai speaks of how the political is in everything, how we cannot avoid it and why it is necessary to reflect this particularly in his own work. “You don’t want to be a generation that is forgotten,” he says, an obvious referencing of Fanon’s admonition that “each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.”

Early in the film Chiurai paints a mural along the entrance wall in the 12 Decades Art Hotel in Johannesburg’s fashionable Maboneng Precinct. The mural’s white and vulnerable woman, accompanied by (black?) balaclava-wearing men, is a powerful image.

Reactions to the mural vary, including some who think the image is disrespectful to white women and therefore in bad taste. The hotel, despite its professed artistic temperament, buckles. It issues a letter to Chiurai; it wants to respect its guests. Soon workers paints over Chiurai’s work.

Remembarance

Consider this incident in how recent exhibitions and works like Exhibit B and The Spear by the white artists Brett Bailey and Brett Murray were received inside (and outside) South Africa. The negative reaction to these bodies of work by predominantly black audiences, has generally been met with a certain kind of dismissive indignation – even in those instances where an attempt at explaining the context or relevance of the works has been made.

The protestors, for their part, have been painted as oversensitive and incapable of understanding the works. Chiurai’s mural experience therefore illustrates just how political art “censorship” in South Africa is.

Chuirai also comes under scrutiny from black audiences. Mcata films a young black man pushing Chiurai: “Kudzi…..whose Africa is that, where is it going, who consumes it? Explain to me how you came to that grotesque vision of ourselves, for whose pleasure?” The young man is clearly uncomfortable with Chiurai’s bleak vision of postcolonial politics; of political betrayal. Chiurai rebuttal is that “in most people’s lives you’ll probably be remembered for three things. The day you’re born, the day you start a revolution and the day you die.”

Black attached to it

But there’s more to Chiurai’s conviction; he has a spiritual calling as a healer. This turns out to be something that is part and parcel of Chiurai’s lineage, a calling that you cannot deny if it is meant for you. We follow Chiurai back to Zimbabwe, his home country. Chiurai’s curatorial collaborator, Melisa Goba, tries in vain to explain what all of this (the calling) means to “The White Queen,” another central and symbolically used character in the film and some of Chiurai’s work, but some cultural divides are not so easily bridged.

Fortunately, spiritual callings seem to be something that has become susceptible to contemporary times. One need not abandon life as we know it in order to answer this calling. Seen in this light, Chiurai’s work takes on a significance that transcends the simple but complicated classification of political art and indeed the very act of being political. His artistic and spiritual callings become one and the same.

Of course, and despite all the high points of the film, it is not without faults. While it is apparent that Mcata is the director, the film itself is a collaborative project that derives much of its weight from presence of Chiurai as subject. There are moments when Chiurai is uncomfortable with this position—moments when the dialogue seems stagnant and the director is at a loss for words during his informal conversations with Chiurai. Compared with the exchanges between Chiurai and Goba in the early part of the film for example, Mcata comes off looking as if he is still figuring it out. However this is not necessarily a bad thing because in the greater scheme of things it does not deter from the film’s value. Perhaps then, it is precisely this that makes the film work as successfully as it does – an aid, to help the rest of us figure it out as well.

*Film Stills Copyright End Street Productions

Playing Cricket While Black

Vernon Philander is a black South African cricket player. This week the media has found him guilty in a trial by speculation for playing cricket while black. Until 1991, and the end of apartheid, playing cricket for South Africa’s national team while black was impossible – irrespective of the sporting talent of the player involved.* Although he may now play for South Africa, Philander and black players like him are consistently reduced to their races and denied the dignity of their humanity by the South African media, which frames every dip in their form within a narrative of unearned, racially motivated placement within the Protea squad. Most recently, unsubstantiated claims have surfaced that racially motivated intervention ensured Philander a place in the World Cup semi-final, where his performance was mediocre.

This one-dimensional commentary is a common occurrence in South African cricket. Players as prolific as Hashim Amla (now South Africa’s Test captain) and Makhaya Ntini (South Africa’s first black African player and third highest wicket taker of all-time) were both summarily dismissed by many media commentators as ‘quota’ players or politically forced selections at the time of their debuts due to slow career starts (a fact which the white liberal media that dominates cricketing commentary and analysis now prefers to ignore). This was after selectors had been applauded by the very same media for ‘standing by’ Jacques Kallis through his famously poor introduction to international cricket.

The media has, however, found consistency in its ability to apply racial double-standards.

Philander, says Peter Bruce writing on the Business Day on 27 March without any need for evidence, was, despite his pedigree, not physically fit to play in the World Cup semi-final. Therefore the decision to play him ahead of Kyle Abbott (a white player) was possibly “tipped by political [reasons]” and thus “stupid”. This is notwithstanding the fact that Abbott himself several days before the game acknowledged that he remained an outsider for a place in the team for the semi-final.

Three days later, experienced cricket journalists then jumped to the same conclusion with the help of a mysterious anonymous (raceless) source within Cricket South Africa noting that Philander’s selection “was forced on Proteas” and that the captain and star of the team AB De Villiers was “reluctant to play the match” as a result. To add irony to insult, Vice and Del Carme add that the real victim in the situation is Philander who as a “star bowler” who has been “cynically undermined” by his own selection and that worst of all this selection makes it look like Philander’s selection “makes him look like a player who has benefited from being black”.

We are certain that Vice and Del Harme speak for Philander when they say that the experience of plying his trade in the biggest game of his career for a world audience was a deeply upsetting experience, whereas their heroic defensive manoeuvre of reducing him to his race has restored his dignity. The depth of both the racial and cricketing inaccuracy and offensiveness of these comments is cataclysmic. It is a poor standard of journalism that allows for publication of an article with no evidence to support its headline (despite three named sources denying the ‘fact’ of the headline).

It is unclear that Philander’s selection had anything to do with his race at all. Over his 29 Test Matches and 28 One Day International games, Philander has a better bowling average than Dale Steyn, South Africa’s premier fast bowler and indisputably the best bowler in the world. (His consistency is a key reason why ESPNCricInfo’s Firdose Moonda suggested he may be preferred ahead of Abbott in the knockout games despite Abbott’s excellent form.) However, Dale Steyn is white. This means that when Dale Steyn underperforms (as he did consistently throughout the recent ICC World Cup in Australia and New Zealand), pundits, commentators and social media enthusiasts remember the old sporting cliché that “form is temporary and class is permanent”. When on the other hand, Philander underperforms (as he arguably might have in the World Cup semi-final) his existence seems to be encapsulated by only his race. Not even Bruce claims that Philander performed worse than Dale Steyn, while Vice and Del Carme dedicated all of 3 lines to Philander’s actual performance.

The fact is that between Philander and Abbott, different selection panels could reasonably come to different decisions on talent alone. The motivation for denying this or exaggerating reasons not to play Philander while ignoring reasons not to play Abbott – such as relative inexperience, less suitability to the conditions in New Zealand where Philander had recently excelled – is at best unclear and apparently racially driven. This type of criticism is an insidious way of entrenching Imposter Syndrome, reinforcing the racist idea that players of colour are undeserving of their places alongside their white counterparts. Philander’s decent performance therefore somehow resulted in a witch hunt for racial interference.

Given the history of South African cricket, the witch hunt might be more fitting in the opposite direction. Why, for example, did only 6 black African players and 23 coloured, Indian or other racially categorised players represented the Proteas in their green and gold strip up to 2013? Why, by this same date, were 83 players out of a total of 112 to represent their country in this format white although black Africans make up 79.2% of the population; coloured and white people each make up 8.9% of the total; and the Indian/Asian population 2.5%? Why do players who have all the benefits of cricket academies, extra lessons, excellent equipment, and former professionals as coaches at their lush private schools continue to get unqualified opportunities? Why, indeed, is there so little affirmative action and transformation in South African cricket?

South Africa has a Constitution which requires us to “recognise the injustices of the past” and take proactive affirmative action measures to accommodate these and other daily, continuing racial injustices. Messrs Vice, Del Carme and Bruce: the way that works is that a player can and should benefit from being black, precisely because he is black and that this has been (and continues to be) to his significant disadvantage throughout his life. And yes, just like racism, affirmative action is deeply political and so is all sport in post-apartheid South Africa. Given this country’s history of exclusion, sporting talent is not the only reason to pick a sports player, just as talent is not the only reason to pick employees for any job. But the fact that a player may have benefited from the politics that we have chosen in this country does not mean that he is not also talented, or that he lacks “merit” to be picked in the team. Vernon Philander, in particular, is an exceptional cricketer who would make any international side on pure merit. He is also a black man. Both aspects of his identity add to the argument for choosing him to represent his country in the World Cup.

As South Africans, we are proud that our country is changing and happy to see that reflected in a cricket team that gave its heart and soul on the field for each and every one of us. Win or lose, ours is the team of Vernon Philander and Hashim Amla as much as it is the team of AB de Villiers and David Miller. And that is what it means to be a South African cricket fan: we must acknowledge the full identity of Vernon Philander – as both a black person and an exceptionally talented cricketer. A failure to do so in the media evidences a counter-productive condemnation for playing cricket while black.

* A very robust and well organized black cricket culture existed at club and provincial level under colonialism, segregation and Apartheid organized mainly under the South African Council of Sports. Some black cricketers also played in ‘separate and unequal’ leagues set up by the white national cricket board. A number of black South African cricketers made it despite white hostility, most notably the late 19th century fast bowler Krom Hendricks and Basil d’Oliveira, arguably one of South Africa’s greatest cricketers, who when denied to play at the highest level by white cricket, ended up test playing for England in the 1960s and into the early 1970s. D’Oliveira’s inclusion in an England tour to South Africa resulted in a political crisis in South Africa (and the UK) at the time. It’s not like this history isn’t known, it’s just that it is hidden in plain sight (it was extensively covered in the black press). For the history of that cricket, a number of histories exist. For starters, here, here, here, here and here. In the history of white cricket under Apartheid, only one black cricketer (he could pass for white) played for the national team, Charles Llewellyn. (Ed.)

March 31, 2015

#Nigeriadecides: Twitter has declared General Buhari as president elect of Nigeria

While you wait for INEC (that’s Nigeria’s electoral commission) to make the final call, enjoy these Buhari supporters dancing in celebration and study up on the broad context for this election between “two perfectly unacceptable candidates.” And while we’re at it, some history: Remember, 31 years ago Nigeria’s next president jailed Fela Kuti for 10 years–Fela served 20 months. Questions we need to ask: Is Buhari a “born-again” democrat, as Wole Soyinka hopes, or still a “Beast of No Nation”? And who are the Felas of today who will fearlessly tell the truth about Buhari’s government?

The defeat of a sitting president at the ballot box will be a significant thing, whatever the candidates involved, and it’s hard not to get swept up with the optimism reverberating around social media in the last two days. Some are describing this as a profoundly transformational moment for Nigerian democracy. Maybe it will be. For now we’ll stick with Cheta Nwanze’s promise to the president-elect:

Dear General Buhari, in electing you, we've come out of the mental block inflicted by the power of incumbency. Mess up, we will vote you out

— Chxta of Greece (@Chxta) March 31, 2015

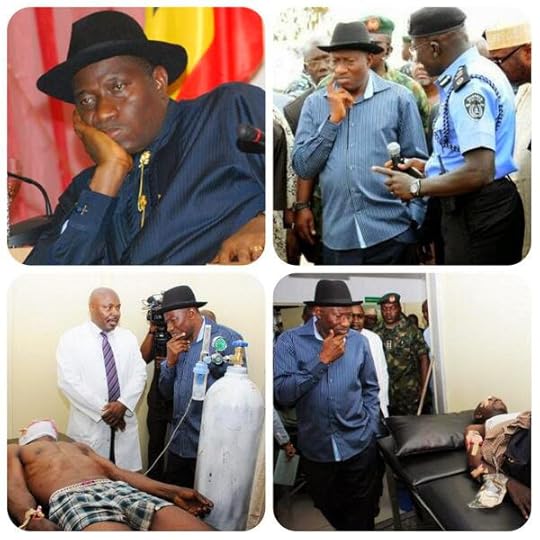

What will Goodluck Jonathan’s presidency be remembered for exactly? We suspect #GEJPose will provide the enduring image.

Why media outlets still fantasize that Apartheid’s footsoldiers will be the ones to stop Boko Haram

In the weeks leading up to the Nigerian election this weekend (official results expected sometime today), Reuters stirred up a lot of speculation with a report which claims the Abuja government is secretly using white South African mercenaries— read apartheid-era security forces—to fight Boko Haram in Northeastern Nigeria.

Then last week, The New York Times realized that Nigerian Twitter feeds have actually documented “white soldiers atop armored vehicles on what appears to be a major road in Maiduguri.” The Nigerian government initially refused to comment, then claimed that the so-called mercenaries were really “technical advisors,” only there “to provide training and technical support for foreign-bought weapons.”

Approximately zero percent of journalists were satisfied with the government’s explanation. And yet, even as international news outlets have scoffed at the government’s attempts to cloak their reliance on foreign military personnel in technocratic mumbo jumbo, an overwhelming among of coverage has relied on the idea that the mercenaries are efficient in order to justify, or at least understand, why the government of a country that was once so closely associated with the anti-apartheid and pan-African movements, could rely on the very same soldiers that fought to uphold the white supremacist regime in South Africa.

And we do know, following reports of the death of the former South African soldier Leon Lotz in Borno state on March 9, that apartheid-era forces are participating in these military (and by proximity, political) campaigns. In the 1980s, Lotz fought for a paramilitary unit, known as Koevoet, that was euphemistically tasked to “root out” nationalist guerrillas in what is now Namibia. The unit infamously targeted civilian sanctuaries including refugee camps and hospitals — and Lotz himself was formally accused of the murder of two civilians who survived the Kassinga massacre. A 1989 government inquest “determined that Lotz and Bouwer took the two into custody for interrogation, murdered them and buried the bodies in a water-filled pit,” as Binaifer Nowrojee and Bronwen Manby document in their book Divide and Rule: State-sponsored Ethnic Violence in Kenya.

Despite the fact that their crimes are public record, The Economist throws its support behind the South African mercenaries. The neoliberal stalwart assures us that their presence is a good sign — while managing to transform white men into actual guns, and reduce the grisly conflict into a bro-y business performance report:

Bringing in experienced hired guns may be a clever move by Nigeria’s army. It has performed abysmally against Boko Haram.

And The Economist isn’t the only publication relying on the contrast between the corrupt and bumbling Nigerian army and these ultra effective, white killing machines. Here’s The Conversation describing the difference between the Nigerian forces and the South African mercenaries:

(T)he Nigerian security and military forces have been embroiled in scandal after scandal ranging from corruption and desertion to human rights abuses. All this has effectively restricted their ability to act decisively against the designated terrorist organisation, which has thrived in the north east of the country over the past three years.

versus:

South Africans have a long-standing reputation as being among the best mercenaries in the world…

The use of South African mercenaries is a logical step for Jonathan’s government who has been battling the insurgency with little success. These men have a track record of providing quality counter-terrorism training through various pop-up private military and security companies. They have assisted several governments in overcoming insurgencies in Angola, Sierra Leone, Iraq and Afghanistan.

South African soldiers have extensive experience conducting mobile operations in hostile environments and can provide immediate access to airpower.

There are other textual examples we could highlight, which also accommodate the mythic power of the mercenaries. But what is most striking to me is how consistent the visual narrative is in all these reports.

Image from Foreign Policy

Image from The Conversation

Image from Washington Post

Despite the fact that the story follows reports of white South African mercenaries sighted (and photographed) atop armored vehicles in Maiduguri, by and large only Black Nigerian soldiers are pictured in the photos that accompany these articles— ie, black bodies are made hyper-visible in a story about white mercenaries. When photos of the white South African soldiers are included, they have been pulled from archival sources— which means that they actually remind us that these soldiers fight to uphold the white supremacist regime. At the same time, the photos are carefully selected to represent the white South African soldier as a sharp-sighted, rational commander. This soldier, we’re assured, never loses control, or glorifies violence (though there are plenty of archival images that would tell a different story). Equally chilling, the selection of these photos refuses to show the way the white South African soldier has aged. His body is perfectly invulnerable, always at its physical peak.

Image from The Conversation

To understand what this immortal (nay, deathless) image stands for, and how it participates in the naturalization of violence, we could start by examining the history of the most famous South African mercenary operation — Executive Outcomes.

Eeben Barlow, who was one of the apartheid state’s most senior military strategists, founded his company just when the Nationalist regime was beginning to falter. As Jeremy Harding observed back in 1997, Barlow quickly identified “political and military instability in Africa to be a market issue” — and the company’s most lucrative contracts involved secure unstable regimes in the oil-rich nations of Angola and Sierra Leone. While Executive Outcomes consistently conducted operations around extractive concessions, “Barlow has a way of speaking about the company’s benefits to civilians as though he were running a Christian outreach project.”

We needn’t defend the Nigerian government or the conduct of the Nigerian military to ask why the corruption of the state narrative effectively legitimizes the activities of the South African mercenaries — which are by definition — illegal. The often repeated, vague assumption that white mercenaries are “effective” ignores the South African soldiers’ record of human rights violations — and gives men like Eeben Barlow a get-out-of-jail free card.

White South African mercenaries have traded on lesser evil narratives and no alternative ultimatums which conflate the violence that has been inflicted on civilian populations in unimaginably horrific ways with the violence the government needs to control in order to secure the election — and as John Campbell points out, they do not promise an end to armed conflict.

In Nigeria, it remains to be seen whether Abuja’s use of mercenaries will encourage “foreign fighters” from elsewhere in the Sahel to rally to Boko Haram’s side. The Nigerian government is already claiming that Tuaregs from Mali are assisting Boko Haram. It would seem that the presence of mercenaries is “internationalizing” the struggle between the Nigerian government and Boko Haram.

And, at the end of the day, South African mercenary groups like Executive Outcomes capitalize on corruption narratives in post-colonial states, expertly mixing fears about inefficiency with dystopian imaginary of death and decay which demands evermore vigilance, evermore impenetrable, indestructible bodies that make demilitarization unthinkable.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers