Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 359

March 19, 2015

Stirring the Spirits of the Murdered Miners: a review of the play “Mari and Kana”

On Thursday, 13 March 2015, at Cape Town’s Company Gardens, during the Infecting the City Festival, a public arts festival in the City of Cape Town, something unspeakable happened. The widows of the Marikana Massacre victims (the August 2012 police killing of 34 striking platinum miners in South Africa’s Northwest Province), in a play titled Mari and Kana, were trying to wake up their husbands from their graves by yelling at them. Marking the gravesite, in front of the Iziko Museum, were thirty-nine white crosses laid out on the lawn.

During the play, the dead miner’s restless spirit circled above the Company Gardens. Even now, days after the crosses have been removed and the actors have long left the stage, the chilling atmosphere set by the play still hangs there.

The performance took place in front of the Iziko Museum, under the invasive statues of colonial rule. The space allowed the performance to be expansive, spreading out on the lawn. The play was haunting and convincing such that it became convincing that the miners were really lying in those graves. The play depicted reality with such preciseness that parts of it became the reality it was depicting.

The Infecting the City festival turns city streets and architecture into galleries and performance spaces, the everyday city walker and art coexist in the city streets, influencing or hindering each other’s movements, or completely rejecting each other. The festival, by virtue of confining itself in the city, is not without its problems of inclusivity. People who live far from the city have to come to the city to experience it. With Cape Town’s Group Areas Act mapping, this is particularly hard to do, even impossible, even though the majority of them converge in the city to access public transport, they are often in town for a limited time, so limited in fact that they are always running to the public transport terminals to catch an earlier bus, train, taxi home. That the festival took place during the week, only spilling to the weekend by its last day, made it extra hard for people to attend.

Long before the play was scheduled to start, the audience gathered around the lawn to see it, some were seated, some stood and others walked around in doubtful gaits, anticipating it.

During the delay, to while away time, I made my own doubtful gaits, to nowhere in particular. Behind the food stalls was the new garden plot.

Many centuries ago, at the same venue, a horror occurred here. The first was when Jan Van Riebeeck came and appropriated the land, named it after the Dutch East India Company and set it up as a vegetable garden. The second horror happened when historians erased the Khoikhoi, original inhabitants of the gardens from the history books.

The horror has unfortunately not stopped. The City of Cape Town recently completed a garden plot in the Company Gardens, which begn construction in February 2014. The new plot was constructed using Dutch colonial gardening principles. Its open stone-lined irrigation channels are also designed after the Dutch “leiwater” water channels. The city named the new garden plot section, the VOC Vegetable Garden (after the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie).

Mari and Kana was presented by Theatre4Change Therapeutic Theatre. The cast was made up of Aphiwe Livi, Azuza Radu, Thembelihle Komani, Thumeka Mzayiya, Abonga Sithela, Slovo Magida, and Lingua Franca.

On the festival programme, Mari and Kana, are described as “Mari and Kana invite us to experience the emotional journey of losing their fathers: The work explores attempts at finding consolations for those left behind by the protagonists’ brothers, sons, uncles and fathers after the Marikana Massacre. The 39 graves presented in public space allow audiences a more intimate and active engagement with the subject.”

During the performance, the gravesite was real such that when the homeless men and women who have made Company Gardens their home roamed around, within the graves, stomping on the graves of the dead, a chill rushed through my body. When kids fled their parents and walked on the graves, their mother’s faces were mortified. It was more than kids stomping on a stage, this was a gravesite, and nobody walks in the gravesite unless they are there to talk to the dead in the way that people talk to the dead.

On Friday evening, during its second performance, speaking to the director, Mandisi Sindo, the plot, he told me, was a narrative of two children, Mari and Kana, coming out of jail and finding their mothers grieving for their dead fathers. Sindo explained to me that the purpose of his theatre group, Theatre4Change Therapeutic Theatre is to help people heal.

To an extent the performance does this but also it does something else, something more terrifying than helping people heal. It opens wounds that have not healed.

When the actors ran frantically from one grave to the next, looking for their loved ones, shouting all the thirty-nine people who were massacred in the Marikana Massacre, screaming at them to wake up, one did not experience the feeling of healing but grief, anguish and the spirit of the dead circling around.

Even after the performance ended, the crosses never became mere props in a play. One could not walk on the lawn, where they were and not feel like stomping on the spirit of the dead.

Azuza Radu and Thumeka Mzayiya, the two leading actors were not concerned with the technicality of acting or entertaining the audience, this is not to say they do not how to act or entertain. Their acting was very real such that they were not simply playing widows looking for their husbands. When they kneeled on their husband’s graves, screaming and cyring at them to wake up, one wished they could walk to the stage and comfort them.

The play made its way into one’s heart not only with the dance but also with the text. The lyrics and the poems were poignant. The poetry was delivered without the accent of poetry or the dramatisation of dramatic theatre.

“It is you black police.

He will never send us money.

He will never write us a letter.”

The text of the music still haunts me many days later after the show. It echoes and echoes in the back of my mind, like a voice faintly and continuously yelling in the dark.

The play had no denouement because it would have been cheating its own narrative. The way it ended was with a song of healing, with an upbeat and somber lyrics.

“The day of the sun rising is coming.

The heaven is not going to rain and thunder forever.

Heal my son. Calm down my son.”

Long after the actors had left the stage, the audience had dispersed, and the stage was cleared of its props, I was left staring into the empty space where the play had taken place, reimagining it, dismissing it, attempting to abandon it there and not take it with but the play is still replaying in my mind, over and over again, action by action, haunting me to remember the Marikana Massacre.

March 18, 2015

Interview with Nidia Minaj: The multi-influenced teenage producer making noise in Lisbon’s vibrant Afro-electronic music scene

Anyone who has been paying attention to the global electronic dance music scene knows that there’s an explosion of musical creativity happening in the different Portuguese speaking ports around the Atlantic. Lisbon in particular has shown an impressive and diverse output of new Africa-influenced dance styles. The main live event celebrating that scene, Noite Principe — based at a club called The Musicbox in the center of Lisbon, and centered around an independent record label called Principe Discos – has become a mecca for international electronic music heads in recent months. As much as it’s revered globally, most impressive is the impact this party has been able to make locally — bringing together youth from disparate parts of a racially, economically, and culturally segregated city, and expose them to each other’s sounds, cultures, and selves.

Sonically, the DJs and producers are omnivorous and indiscriminate in their influences, and the resulting products reflect that. Local music style variations like tarraxo, kuduro, funana, batida, and a local house-influenced sound called afrobeat, form a stew with internationally popular flavors like trap, r&b, Brazilian Funk, house, coupe decale and yes, afrobeats. However the sounds coming out of this scene aren’t just simple copies of above named genres. Each producer I’ve come across is quite singular in their take on the Afro-portuguese dance sounds, and can mix all or none of these things in a single track.

Principe Discos artists in particular are marked by their preference for minimalistic electronic drum programming (rather than lush-layered synth melodies for example.) Like the footwork producers of Chicago, their sound is tailor made for dancers watching each other in a dark nightclub roda. I see these producers almost as painters of beats, rather than traditional song composers. And in a way, their compositions deserve more than words — one just has to listen and watch to understand.

In order to begin highlighting more of the incredible musical phenomenon here, I wanted to put up an interview I conducted with Bordeaux-based producer of Cape Verdian, and Guinea-Bissauan origin, Nidia Minaj — the latest artist to release on Principe Discos. I actually corresponded with her via another label Brother-Sister records, who released her debut project, Estudio da Mana.

Here are selections from that interview with both Brother-Sister records and Nidia, in which we explore a bit her rise as a teenage super-producer from a small French city.

Nidia, How did you learn how to make Beats?

Nidia Minaj: I learned how to make beats “alone,” I looked on youtube and asked DJ Dadifox to explain things that I didn’t understand.

From what I can tell, there aren’t many women producers in the scene in Portugal. Being outside of that scene, do you think it’s easier to enter into the scene as a woman?

NM: For me it’s not a question of being easy or difficult. I do what I love, and that’s all that matters to me.

Are there many young Africans in Bordeaux? How is life for them there, are there parties, dances, something like that?

NM: Yes, there are many Africans in Bordeaux, and their life is very exciting. The Africans in Bordeaux are always in parties, the parties in Bordeaux start on Thursday and end on Monday. On Mondays, half of my class in school is asleep for having gone to the parties!

Do you do, or want to do collaborations with artists in other countries, like Portugal, Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau?

NM: With vocalists, not yet. However, I already have many vocalists asking me for beats. But, I never do it because I don’t have a lot of time. For me, to make a beat for a vocalist isn’t to make a beat in two or three hours. For me it has to be an entire day to do everything right and finish mastering everything. It has to be a quality beat. I do collaborations with other DJs, but for vocalists.

Do you communicate regularly with any artists outside of your city, and if so is it only by the Internet?

NM: I communicate a lot with some artists. I communicate more with Angolan artists, some I know by the Internet, or we already have met in person.

Do you want to experiment with the music of your parent’s home countries? Have you visited either of them?

NM: I want to experiment with all the musics that I like. I’ve never been to my parent’s home countries, but I would really like to go.

Who are Kaninas Squad and what happened to them? Do they still make music?

NM: The Kaninas Squad was my group that I had with some friends in Portugal. The Kaninas Squad aren’t together anymore since I left Portugal, they didn’t make any new music, and now they only do live shows. However they changed their name. My friends are now called As Mais Potentes.

———

Who are Brother and Sister records?

Brother Sister Records: Brother Sister Records is an artist-run label that we started almost ten years ago as a loose collaborative collective of DIY bands and producers. It’s primarily based in Melbourne, Australia, but some of our founders/artists are currently based in New York, Windhoek, and Kuala Lumpur.

We’re proud of the fact that the label’s output shifts as our tastes do. In the beginning we were putting out different forms of guitar music (folk, post-punk, etc). Our recent releases span from music with intercultural elements to more familiar club sounds. We also run a monthly guest mix series that has been a great way to support and interact with artists we love, like Beak, Strict Face, Neana, etc.

Does Brother-Sister Records have representation and/or relationships in Portugal or France?

BSR: No. The label is pretty independent/DIY. In the beginning each of us was making music with no real “ins” in our local music scene. We, like many, had to learn everything by trial and error. That ethos has endured — BSR isn’t at all institutional. For us it’s just good to be able to share our past experiences to emerging artists and to offer support to good music, especially by artists who we think are overlooked. The label also allows us to pursue our own interests into musical collaboration and research and so its a good way to learn whats going on in, and to interact with, other places and other cultural contexts. It’s more about opening up spaces for things to occur.

Are you in touch with other producers in the Lisbon scene?

BSR: We’ve been massive fans of the latest phase of kuduro/tarraxo/fodencia coming out of Portugal and France for quite a while now, and have been in touch with some of the artists from that scene. The incredible thing is how young most of them are and how fresh and emotive so much of their music is. There are also some really interesting musical links between those artists and DJs in Lusophone countries in Africa and even in Brazil. What we’ve found is that the less established artists, who also tend to be the ones we love the most, often have never met each other and are just collaborating on tracks via the Internet.

Have you been to any of the Noite Principes, or have you been in touch with any one at Principe Discos?

BSR: It’s great that Principe Discos has emerged as a strong forum for artists like Nigga Fox, Lilocox and the Tia Maria crew, all of whom thoroughly deserve the attention. We haven’t reached out to them, partly because sites like Soundcloud allow us to communicate directly with the emerging artists whose tracks we love.

Do you have any other plans for Nidia in terms of managing her career?

BSR: We initially approached Nidia as massive fans. It seemed crazy how unknown she was, and it was especially exciting to see a very young female DJ making this sort of music. We wanted to learn more about her and to spur her on to make a formal release, which could garner a different sort of attention from the individual (amazing) tracks she had been dropping on Soundcloud. Obviously, we would love to continue working with Nidia but we also hope that a label or labels with better resources and larger listener-ships will think about working with Nidia in the future.

Does the Development Industry really need new clothes?

If you don’t work in the international development field, it may have escaped your attention but we currently find ourselves in the dawn of a new global development epoch. As the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) expire in September 2015, their replacement – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – will soon take over.

The ultimate goal of this brand new set of global standards and targets is to put in place the strategies, principles and partnerships to make this world a more equal and just place over the next fifteen years. The recently released synthesis report offers a (provisional) blueprint of what sustainability will look like. Its ultimate aim? Ending poverty, transforming lives and protecting the planet. The first goal is to “eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere”.

The word sustainable shows up no less than 199 times in the report’s 34 pages (plus 12 hits for sustainability). As it stands, there are seventeen goals, 169 targets and six essential elements (dignity, people, prosperity, planet, justice and partnership) that will guide the allocation of trillions of development dollars and shape national policies of member states (though the extent of the latter will differ in each country). With ambitions this high, the SDGs are worth speculating about, as evidenced by a slew of recent op-eds and blog posts.

With fifteen years of the MDGs behind us, an evaluation of their impact seems a logical starting point to assess the new agenda’s potential to drive positive change. Yet, as some commentators have pointed out, there are some notable differences between the two agendas. One major difference between the old and the new set of goals is the process to create them. Unlike the ten MDGs, which were established by then Secretary-General Kofi Annan and a handful of confidantes, the SDGs are the product of huge rounds of global consultations. A consequence of the more inclusive approach of the SDGs, as some governments and human rights NGOs have lamented, is that the new goals and targets are too many, and lack both clarity and direction. For economics professors Abhijit Banerjee and Varad Pande, who wrote about it in the New York Times, it will be challenging to balance ambition with practicality. Former World Bank Economist Charles Kenny is skeptical about the impact of the MDGs and, by implication, the potential of the SDGs. According to him, the MDGs may have led to an increase in aid – but it’s not clear they always led to progress. One critical problem of the new agenda, Kenny argues, is that the goals lack a clear rationale on what, exactly, they will accomplish and how.

Similarly, Duncan Green, an advisor for Oxfam, argues that we lack the actual evidence to show that the MDGs influenced government policies. Drawing on the findings of a report called Power of Numbers, he points to the limitations and unintended consequences of measuring justice and human well being with quantifiable targets. One example, offered by the report and cited by Green, is the MDGs’ focus on gender parity in education, the workforce and the political sphere. “’These narrow targets were a dramatic change from the more transformative understanding of “gender equality” that had emerged from the 1995 Beijing Conference on Women and the civil society movements of the 1990s.” With regards to education, the MDGs’ preoccupation with raising primary school access, often hailed as one of its greatest achievements, has been singled out for its detrimental effect on the quality of education, as many schools lack the resources and teaching staff to actually accommodate the newcomers. While it’s important to get all children in school, enrollment and attendance rates don’t tell us much about what they’ve learned in class.

William Easterly, currently a Professor at NYU and famous for his skepticism towards development aid, told the New York Times that development experts “mistake development for an engineering problem” when in reality development progress only happens “when people identify problems and push for solutions through their political systems.” He recently shared on Devex that the SDGs mirror the development community’s “fetish with action plans.” To him, the excessive usage of the term sustainability in a global framework that tries to please everyone rendered the project somewhat empty. Yet even he admits that both the MDG and the SDG share the potential to spur “advocacy and motivation.” However, with the efforts and budgets that are invested in the SDGs, they should amount to a great deal more.

March 17, 2015

Photo of the Day: Irony arrives to Brazil

In today’s news, the mainstream Brazilian media try their hardest to illustrate that protests against, and calls for impeachment of sitting Brazilian president, Dilma Rousseff (for her proximity to the Petrobras scandal), are not solely from the disgruntled “white elite” (one commenter said that the protests looked like a World Cup matches — another that the protests were just a scheme to unload all the overstocked Brazilian National Team gear after their disastrous exit from the tournament.)

Now, we here at Africa is a Country are aware that the media tends to sensationalize racial and social divides in Brazil, however we couldn’t help point out that with just a touch of irony, one lucky contestant (I mean c’mon…) was able to gain his fifteen minutes, by answering the call to fulfill the Brazilian media’s wildest fantasies.

Translation: “White elite against Dilma”

Under the radar: Guinea Bissau’s Sana Na N’Hada is one of Africa’s most important filmmakers today

In a cinematic career spanning some four plus decades Sana Na N’Hada has borne witness to the best and the worst times in Guinea-Bissau. He joined Amìlcar Cabral’s revolutionary army in the heady days of the war for independence. In the restive years following self-rule he set about making evocative films that, at their very best, captured and challenged the prevailing zeitgeist. Today, approaching his 65th year, undiminished and evermore imaginative, he is still hard at work shedding light on the political and social realities in his homeland.

His latest film Kadjike (Sacred Bush), 2014, is set on the pristine shores of the Bijagós Archipelago, and follows the lives and rituals of the islanders as they face up to the threat of drug traffickers in their midst.

In the last decade Guinea-Bissau has become the key transit hub for cocaine trading between Latin America and Europe. The Bijagós Archipelago, a sprawling mass of largely uninhabited islands, has been the focal point of trafficking activity in the country that has turned it into what some observers call a ‘narco-state’.

On a simple level, Kadjike is a coming of age drama. On a deeper level it is a meditation on the schism between tradition, Guinean customs, and the rising tide of modernity–something which has been a constant theme throughout N’Hada’s cinematic career.

On the eve of his initiation into adulthood Ankina is torn between his responsibilities to his people and his love for a girl with whom customs forbid a relation. Drug traffickers promising a better life in the city lure his boyhood friend Toh away from the island. Facing important decisions at the crossroads of their young lives, both boys must find a way out of their predicaments – a way back to their people.

The poignancy of this film lies in the juxtaposition between the natural beauty of the archipelago and the imminent dangers that lurk in the shadows of this fragile world.

“I want to show people why the natural beauty of my country is so important and why we need to stand together to prevent our nation and culture to be harmed” – N’Hada says.

Kadjike is only N’Hada’s second feature film. His first, Xime (1994), follows the struggles of a rice peasant confronted with losing the authority over his two sons during the fight for independence.

In the intervening years N’Hada has flirted with both documentary and shorts. Despite his minimal output he is arguably one of the most important filmmakers on the continent today and has long been regarded, along with his contemporary Flora Gomes, a titan of Guinean cinema. Both are credited with producing the first ever fiction film (Mortu Nega, 1988) to be made in Guinea-Bissau.

N’Hada’s career in cinema began during his days as a revolutionary in Amìlcar Cabral’s independence movement. He was taught first aid in order to help out at the local field hospitals, and with the remaining part of his time he went from village to village to educate the people about the fight for independence. It was during this time that he began to turn his back on his medical studies in favour of cinema. At the behest of Cabral he travelled to Havana along with Gomes, studying under the auspices of legendary Cuban cinematographer Santiago Àlvarez.

Upon his return to Guinea-Bissau he rejoined Cabral’s movement and set about documenting the war of independence on film. Reflecting on his cinematic conversion he states, “I didn’t come into cinema because of talent but because I felt obligated to tell certain stories. There has always been a question of necessity.”

In 1976, shortly after independence, N’Hada co-directed two short films with Gomes: The Return of Cabral and Anos No Assa Luta – both tributes to the revolution and to their great political icon Amìlcar Cabral.

His life long friendship and collaborations with Gomes has produced some seminal works in the canon of Guinean cinema. His greatest recognition however has come in the form of Sans Soleil, a documentary collaboration with French filmmaker Chris Marker. Shot in the early eighties, it was recently voted one of the top five best documentaries ever made.

As well as Gomes and Chris Marker, N’Hada counts celebrated Senegalese filmmaker Sembène Ousmane and Santiago Àlvarez among his great cinematic influences.

Despite all the uncertainty facing his country today N’Hada remains hopeful about the future. As we speak, he is already turning his mind to his next feature, a film documenting the positive effects of independence in his homeland.

With Luta Ca Caba Inda (The Struggle is Not Over Yet), an ongoing project first shown in 2012, N’Hada may yet bequeath his most profound legacy to Guinean cinema. Along with Gomes he has set out to find and make accessible the remains of raw film material made in the country after independence but either lost or damaged in the era of political upheaval.

For a man who has seen so much and lived through such uncertain times it is perhaps the defining point of reference for his dedication to his country and his people that he has found time, since 1979, to head the National Institute of Cinema of Guinea-Bissau.

Trailer for Kadjike:

Dir. Sana Na N’Hada, Guinea-Bissau, 2013, duration 115 min, production LX Films.

(Screened at Film Africa London, November 2014)

Why won’t the Malawian media report on crazy mobile phone rates?

BBC recently reported that the average Malawian spends more than MK5400 (US$12) a month. That’s more than half the average monthly income in Malawi. Proportionate to earnings, Malawi has the most expensive mobile phone rates in the world.

There is no shortage of complaints within Malawi about expensive phone tariffs but this report (based on findings by the International Telecommunications Union) shows the extent of the problem. For a week, following the report, I monitored local newspapers reports and the mobile phone rates received no coverage at all. Not even by the growing number of columnists and opinion writers.

Why the silence on a story that is obviously of pressing concern to ordinary Malawians, and which made a splash internationally?

Only Nyasa Times, Malawi’s populist news website, republished a copy and paste version of BBC’s piece. Newspapers are the main agenda setters within local media in Malawi, and they didn’t cover the story at all.

There are two major mobile phone companies in the country, Airtel Malawi and TNM. These are also the main providers of mobile internet. Those familiar with the political economy of the local media will understand the media blackout on the mobile rates story. Like the rest of the world, Malawi’s newspaper industry depends on advertising revenue and mobile phone companies have become indispensable source of that revenue. The media industry cannot afford to get on the wrong side of these mobile phone corporations.

For a long time, the Malawian government and NGOs were the largest advertisers but mobile phone companies have now taken over because they are very consistent advertisers and they buy prime space in bulk —daily space for a whole year in some cases. There is fierce competition between the duopoly of Airtel Malawi and TNM and this drives the need for endless media advertising between the two.

An insider working with Airtel says: “all mobile phones companies buy strip ads [advertising banners on the bottom of front and back page] for the whole year.”

A look at a whole week’s run of the country’s two dailies, The Nation and The Daily Times shows strip ads alternating between the two mobile phone companies. If Airtel has a front page on Monday, TNM will have the back page, and on Tuesday it is the other way round.

According to the insider, these strip ads are worth MK180 000 (US$400) a day, which means newspapers make roughly MK131 million (US$291,111) annually from strip ads alone. Add these strip ads to various full-page adverts worth an average of MK280 000 (US$622) per advert, and you see that the revenue is colossal.

The insider said, of course the government and NGOs are important but they are not as valuable as mobile phone companies because government and NGOs mostly place job vacancies and press statements, which are neither daily nor in colour—which is more expensive, and they do not book expensive prime spots like front and back pages.

This explains the newspaper blackout on the mobile phones rates story. The mobile phone companies may not issue editorial directives but, as they say, only a foolish dog bites the hand that feeds it. Newspapers know exactly what to do. Of course the local media always have a go at politicians, the government and the civil society.

The media responsibility, always, is to hold to account those holding public positions. But this must include powerful corporations that rip off poor Malawians, 75 per cent of whom live on less than US$2 a day.

Of course Malawi media does a lot of commendable work reporting on government excesses and corruption in high places but the media know that they can afford to get on the wrong side of the government and politicians. The media know they have a public backing should the government withdraw advertising revenue or bring draconian media laws. This was the case in 2010 when the government of the late Bingu wa Mutharika threatened to withdraw advertising with some private media houses such as the Nation Publications Limited.

In 2007 Blantyre Newspaper Limited (BNL) were forced to retract a story they reported on a love triangle involving a Catholic priest, a banker and a married woman. The woman’s husband was seeking divorce in court after discovering that the wife was having an affair with the two men.

At the time BNL had a debt with the bank where the involved banker worked and his influence forced the immediate retraction of the story despite the fact that the story was based on a case that took place in an open court. Caroline Somanje, a journalist who wrote the story and BNL General Manager were fired from BNL for no editorial reasons, as BNL alleged, but for being insensitive to BNL’s financial interests.

Corporations in Malawi have more media influence than the government. Sadly, most people only pay attention to government’s efforts to muzzle the press, most through threats and regulation. This means corporate powers in Malawi are left unchecked. It would not surprise me that mobile phone companies also have financial support of the political establishment. Political parties in Malawi are not mandated to disclose their sources of income, and so they don’t.

Image via Innovations/Concern

March 16, 2015

What are you scared of Joseph Kabila? Senegalese, Burkinabe, and Congolese Activists Arrested in DRC

Being a pro-democracy, nonviolent youth activist is a dangerous thing in some countries. On Sunday afternoon activists from Senegal’s Y’en a Marre (We’re Fed Up) movement and Burkina Faso’s Le Balai Citoyen (Citizen’s Broom) along with several journalists and Congolese activists were detained after a press conference just outside of Kinshasa. The local NGO Filimbi invited the activists to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for a series of workshops and events. The exact charges or reason for the arrests are unclear.

In DRC during the past few months, citizens have hit the streets en masse in opposition to legislative changes that call for a census before the 2016 election. Many see this as a means for President Joseph Kabila to stay in office beyond his two-term limit because it would take some time to organize a national census. Demonstrations have been violent with hundreds of arrests and more than 40 deaths.

Apparently, just the presence of the West African activists was threatening to the Kabila government. The Y’en a Marre protest movement emerged onto the scene in early 2011. The founders—consisting of youth activists led by a collective of some of Senegal’s most famous rappers and journalists—first organized protests to denounce injustice and inequality in the country. The movement gained popularity when then 85-year-old two-term president Abdoulaye Wade proposed changes to the constitution that would have ensured his success in the next elections by reducing the number of votes needed to win an election from 51 percent to 25 percent. The changes would have also established the post of vice-president, to which many claimed Wade intended to nominate his son Karim, thus creating a family dynasty. Wade responded to the massive protests by withdrawing the proposed changes, yet he moved forward with his controversial bid for a third term. Y’en a Marre and other citizen coalitions turned their energy toward defeating Wade at the ballot box. The collective used the tools they had at hand—their popularity, their microphones, and their access to the media. They took to the streets to reach out to the population by conducting community meetings and handing out flyers. They also created strategic media campaigns consisting of a series of songs, videos, and concerts, which also included a voter registration campaign and a get-out-and-vote campaign titled Ma carte mon arme (my card my weapon) and Juni Juni votes (thousands and thousands of votes).

Le Balai Citoyen (Citizen’s Broom) formed during the summer of 2013, to struggle against bad governance and to improve social conditions in Burkina Faso. When they formed the goal of Balai Citoyen was to struggle against the ruling party’s attempt to change the constitution to allow 27-year President Blaise Compaore to run for a third term. The name Balai Citoyen signifies the need to sweep the political scene clean. The musicians at the head of the primarily youth-led Burkinabe movement are rapper Smockey and reggae artist Sams K. Their movement gained popularity in October 2014 with the citizen uprising that ultimately Campaore to resign.

There are clear similarities between Y’en a Marre and Le Balai Citoyen. Both groups assert a pro-democratic and non-violent position and both call for the participation of the population to create change through protests. According to Smockey, “like the movement Y’en a Marre of Senegal, Le Balai Citoyen will be the voice to denounce bad governance.”

Y’en a Marre’s ultimate objective has been to cultivate a Nouveau Type de Senegalais (NTS), or new type of Senegalese citizen, one with a heightened sense of civic responsibility. Increasingly they assert the desire to effect continental change. While the Arab Spring left regional instability and insecurity in its wake as weapons and fighters have traveled across the Sahel, the Y’en a Marre protest movement is having a different type of regional impact as the rappers have traveled and connected with other activists across Africa. These new nonviolent, pro-democracy movements have slowly and quietly gained momentum over the past three years. According to Aliou Sane, one of Y’en a Marre’s spokespeople who is among those arrested in DRC, “The countries of West Africa all suffer from similar problems relating to governance and leadership.”

The two groups have been successful because of their direct messaging to the people but more importantly because they emphasize peaceful protest. In 2011 journalist and coordinator of the movement and also detained in DRC, Fadel Barro, stated, “we did not want the Arab Spring. We always wanted non-violence. We wanted to defeat Wade in elections, we did not want our country in flames.”

Y’en a Marre and Le Balai Citoyen have always acted in accordance with the law. All of their activities in DRC have been public with activists regularly updating Facebook and tweeting their whereabouts. They made it clear that they believe in working through democratic institutions. The government of DRC therefore has nothing to fear other than the spread of ideas. The international community should press for the immediate release of these activists who have always offered an alternative to violence.

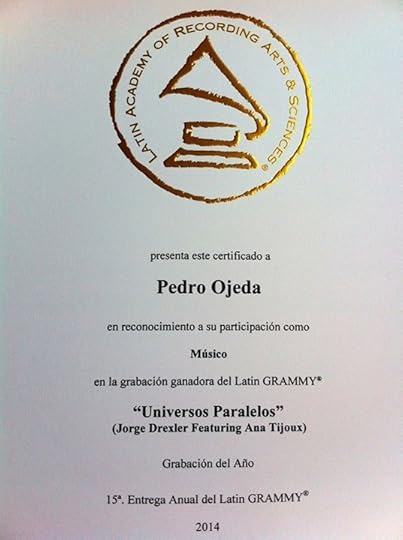

Dear Grammy Awards: A Letter From a Colombian Musician

Pedro Ojeda is a Colombian musician, member of many influential bands, such as Los Pirañas, Romperayo, Ondatrópica and Chúpame El Dedo. Last year, the song “Universos Paralelos” by the Uruguayan Jorge Drexler and the Chilean Ana Tijoux, was awarded a Latin Grammy as “record of the year.”

Recently, Ojeda received a diploma from the Grammys for being part of the group of musicians who worked on the recording of the song. This prompted him to write a heartfelt note to the Grammy Awards on his Facebook profile, which we now translate and share:

Dear Grammy Award:

Thank you for sending me this nice diploma to my house (for having been part of the album of my friend Drexler, who is a great guy, following the call of my pal [Mario] Galeano [from Frente Cumbiero, Ondatrópica, and others, and one of the producers of Drexler’s “Bailando en la cueva” album], who is also a great guy). Nonetheless, I would like to take advantage of this situation to propose a debate about the, in my humble opinion, inordinate relevance you have in the life of many musicians from my country (and from many other countries).

While the recognition you give to highlighted artists and to high quality music recordings (even though I have never liked any kind of competition), I am very worried about the fact that many musicians from my generation, specially the youngest ones, see you as their god, as the only longed-for goal, that they think the only way to succeed in life is through your validation, and that their only life dream is to go to your house in Las Vegas and take a picture with you.

This pyramidal, lazy and monothematic cultural phenomenon tends to disconnect many young people from their environment and their local-artistic, cultural and political problematics. It also makes them underestimate and negate the great musical and cultural value of their history and surroundings, and of the great deal of musical masters and cultivators from their country, who have never played, and possibly will never play, on your red carpet, nor will they be part of your chosen ones and nominees because they are not part of your allies, giant record labels (or majors), and they don’t have the money to be part of your showroom.

These young people I speak of, blinded by your recognition, also don’t notice the great amount of festivals, musics, melodies, rhythms, repertoires, musical and cultural circuits that exist in Colombia and Latin America, just as in the rest of the world, different from the standards that are heard and managed in your awards and in your circuit.

This is why I think is of vital importance that, in every town and city, we stop looking only towards your house in Las Vegas, so we can begin to look at each other and start to get rid of this third-world burden on top of us.

Thank you for your attention,

Your friend,

Pedro.

#WhiteHistoryMonth: Britain’s Racist Election

Last night, Twitter in the UK was all over a Channel 4 documentary, “Britain’s Racist Election.” It tells the story of the election of racist Conservative politician Peter Griffiths (pictured above) to a seat in Smethwick in the West Midlands in the 1964 General Election. Watch the documentary here (it’ll hopefully be available on YouTube soon).

Here’s the trailer:

The story is remarkable (for a fuller write-up, check Stuart Jeffries’ piece for the Guardian from last year) and well worth repeating. For example, we find out that it was Cressida Dickens, the 9-year-old daughter of a Conservative party strategist, who coined the infamous slogan: “If you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Labour.” She says the slogan occurred to her after chanting the rhyme “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe, catch a n***** by the toe” in the school playground.

“If you want a n***** for a neighbour, vote Labour” was daubed on walls across Smethwick during the 1964 campaign, and has become recognized as the nadir of British electoral history.

There is also archival footage of the inaugural meeting of the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham, led by a 27 year old named George Newey.

We then see Malcolm X visiting Smethwick in 1965, after white residents attempted to institute segregation in the town. He was murdered just nine days later.

Obvious parallels are being drawn with the cynical mobilization of “fears over immigration” by all the major parties ahead of the upcoming general election in May. The film closes with soundbites from current prime minister David Cameron, Labour leader Ed Miliband and UK Independence Party’s Nigel Farage, each bloviating over “immigration” in a way which has become terribly familiar — the very same euphemisms mark the speech of out-and-out racists from back in the 1960s — and which sadly looks certain to be a vote-winner for them at the polls this time.

The landscape has shifted in the past decade. In 2005, Conservative leader Michael Howard was panned when he was seen to be cynically demonizing asylum seekers and immigrants to increase his popularity. His key strategist on that failed campaign was the Australian Lynton Crosby. Now Crosby is back running the Conservative election campaign for 2015, and applying the same old playbook. This time it’s working, and all the major parties sound like Michael Howard did in 2005 when he was widely criticized for leading “the nasty party.” What was “nasty” in 2005 is the norm in 2015 — focus-group approved and rabbited relentlessly across all platforms.

One pitfall the film avoided was the centrist tendency to tie the history of racism in British politics to the fringe xenophobic party UKIP (previously the British National Party served this role). UKIP have attracted extraordinary amounts of media coverage in the past year or so, and are commonly framed as dangerous rivals to the Conservatives for right-wing votes. In fact, UKIP are a major asset to the Conservative Party, whose venal assault on the living conditions of ordinary people and the major institutions of Britain’s social fabric in the name of “austerity” gets a gloss of respectability by contrast with the overt bigotry of UKIP.

There is also a broader historical context which the film never quite investigates, but that Musa Okwonga pointed to:

The framing of the UK #immigration debate is so often "they are coming here to take our resources". There's an Empire-sized irony in that.

— Musa Okwonga (@Okwonga) March 5, 2015

The imperial history that continues to undergird British anxieties about non-white presence in the UK (the polite term used to be “multiculturalism” before that became a name for something which “failed” in the 90s) needs to be analyzed in terms of class. Then as now, ordinary people are being screwed by their government (“austerity”) and “immigration” is simply the most popular scapegoat.

W.E.B. Du Bois argued exactly 100 years ago that nascent welfare programs in the early 20th century effected an alliance between rich and poor at home that was only possible due to economic expansion overseas through imperial projects. The popular idea of “the undeserving poor” was mainly displaced to Africa and other parts of the British Empire, with exploitation reorganized along what Du Bois called “the color line.”

The Empire remains hugely popular among people of all classes in the UK, with romantic myths of “Britannia ruling the waves” closely guarded by the current government with the help of the likes of Niall Ferguson. But the Conservatives also know, deep down, that the Empire is over. The alliance Du Bois pointed to between different classes no longer seems necessary — there is no Empire left to exploit.

The idea of “Johnny Foreigner” using the National Health Service or a state school, without having paid for it, is so awful for many Brits that it makes more sense to scrap the whole thing. Any public institution guilty of such “waste” must be privatized because private enterprises are absolutely “efficient.”

The press is fixated, to an astounding degree, on “benefit scroungers,” but it is never enough to show white “indigenous” British benefit scroungers, however much that usefully plays on the demonization of the working class. What is needed are recognizably “other” scroungers. Thus infuriated, the great British public feel sure they are being horribly ripped off by the free healthcare, education and other public services they have relied on all their lives.

And so, in Britain in 2015, racism is being used to dismantle the consensus on the welfare state, and to undo the greatest achievement of British democracy.

March 15, 2015

Between Magic and Reality On Otavalo, in the Largest Outdoor Indigenous Market in South America

Rimarishpa, rimarishpa kausanchik (Talking, talking we live)

Hiding in between the fertile Andean nostalgia, overlooked by the volcanoes Imbabura and Cotacachi, the colorful textiles of the city of Otavalo, in northern Ecuador, contrast with the green pastures and grey volcanic soil. In this commercial post the past and present are in permanent dialogue in the ongoing process of self-actualization of the Otavalo indigenous people, once more strained by the tension of Westernization and tradition.

The colors of Otavalo

Waking up before the sun raises, Julio goes out to work in the minga (communal reunion) that the town council has invoked to fix the road that leads down to the city. Cars will soon be passing by. With a hoe in his hand he works for the next hour. As the sun appears in the east, he can’t help but think that the best places in the market have already been taken.

He returns home and feeds the chicken grains of corn while his wife, María, cooks potato tortillas for the three kids. He sends the two oldest ones to school, while he ties the two-year-old in a green sheet behind María’s back. It combines well with her blue anaco (dress), her embroidered blouse, her golden necklace and her single black braid falling down her back. He wears his espadrilles, white pants, a blue poncho and a hat from which the same black braid falls.

Julio uses public transport, a small bus that rolls peacefully down the mountain and sometimes shuts down its engine to save some gas while endangering the passengers. After an hour he arrives to the warehouse where he keeps his textiles. He packs them all into a bag twice his size, and heads to the centennial Plaza de los ponchos, crafted, at least in its current design, by the Dutch artist Rikkert Wijk in 1971. It is the largest outdoor indigenous market in South America.

Once inside, he notices the familiar array of alpaca sweaters and socks with animal and symmetric patterns, wool pants of every (in)conceivable color, paintings and tapestries depicting the triangular ponchos and hats worn by anonymous figures, jewelry and handicrafts, the Andean charango (a string instrument) and the quena, an instrument which imitates the sound of the wind. Some are handmade and others are cheap imitations of folkloric paraphernalia and motifs.

With his stand open, the first American tourists arrive. This haggling event will become a multilingual experience. Americans will begin speaking in a broken Spanish, to which the Otavalo will answer in a more fluent English. The dialogue will continue in both languages, an agreement is close to being made, but then Julio turns to María and asks in Quichua what does she think of the price.

The American tourists have to wait for an agreement. If Maria doesn’t approve, more haggling will be done. The American tourist may have overpaid, who knows, but he will leave with the sensation that he did not just buy a textile, but an entire folkloric experience.

Symbolic Rituals

But rather than romanticizing the history of these centenary people, the present state of Otavalo is a coincidence of historical events. Their plight has been the plight of many indigenous people throughout South America: trying to maintain and reclaim their own culture since the Incaic expansion to the north.

The Inca method of conquest included relocating and fragmenting the conquered people to prevent any organized uprisings. Nevertheless, the Incas were impressed with the Otavalo technique of manufacturing textiles and assigned them to weave for their nobility. Later, during the Spanish colony, Otavalo was made into a textile producing obraje, a business enterprise in which indigenous people were employed, and usually exploited, as the workforce. Yet, despite continuously succumbing to foreign rule, the Otavalos managed to maintain the community united and to recreate their identity around the textile manufacture.

In 1822, the independence of Ecuador from the Spanish crown accelerated their transformation. Since then, a mixture of external forces and domestic agency have gone to reshape the identity and subsistence of the Otavalos.

After its colonialist expansion and Industrial Revolution, Britain had a virtual monopoly of the world trade of wool and cotton, which it could produce cheaply. This monopoly lasted until World War I when British exports were blocked by German U-boats.

This shift in the global market further developed Otavalo’s local textile industry, but it was not the only factor. In 1954, an UN-sponsored mission had brought Dutch artist Jan Schroeder, who taught interlocking tapestry to communities in the mountains. In the 1960’s, members from the American Peace Corps came to town and, in a still polemic move, encouraged locals to change their craft and to incorporate other cultures’ designs so they could make their sales more efficient and their profits bigger. Finally, the building of the Pan-American Highway, which goes through Otavalo, put the town on the map.

The question is then, how genuine is the Otavalo product and culture? Nowadays, Otavalos can be merchants or farmers, rich or poor, may have never left the city or have travelled worldwide. Nevertheless, their continual ritual existence, anywhere where they are in the world, has located their identity somewhere in between the magical and the rational.

Besides the material symbols of identity and their language, they embrace both Catholicism and traditional legends, celebrating Christmas and Inti Raymi as a community happening. These traditions of feasting and dance become spaces of dialogue where the identity of the Otavalo is put under question. Despite the differences and inequalities, by engaging in dialogue, they develop bonds of belonging.

One traditional legend tells of a drought that hit the region. The elders demanded that a young and beautiful virgin had to be sacrificed to the god of the volcano. Nina Paccha was chosen but her lover Guatalqui preferred to run away with her. They were persecuted and, as they ran, the elder or taita Imbabura turned the woman into a lake and Guatalqui into a tree, now known as El Lechero, while drops started to fall from the sky, marking the end of the drought.

In the Otavalo worldview this story is as real as the market economy they live in. This is evidence of the negotiation between oral memory and immediate material surroundings; a negotiation which has entered a new stage in the era of information and the tension between tradition and Westernization. One won’t trump the other. Instead, they will coexist as a conclusion for the meaning of being Otavaleno: a way in which, from communal belonging, you can draw a sense of individuality.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers