Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 330

September 19, 2015

Achille Mbembe on The State of South African Political Life

In these times of urgency, when weak and lazy minds would like us to oppose “thought” to “direct action”; and when, precisely because of this propensity for “thoughtless action”, everything is framed in the nihilistic terms of power for the sake of power – in such times what follows might mistakenly be construed as contemptuous.

And yet, as new struggles unfold, hard questions have to be asked. They have to be asked if, in an infernal cycle of repetition but no difference, one form of damaged life is not simply to be replaced by another.

The force of affect

Indeed the ground is fast shifting and a huge storm seems to be building up on the horizon. May 68? Soweto 76? Or something entirely different?

The winds blowing from our campuses can be felt afar, in a different idiom, in those territories of abandonment where the violence of poverty and demoralization having become the norm, many have nothing to lose and are now more than ever willing to risk a fight. They simply can no longer wait, having waited for too long now.

Out there, from almost every corner of this vast land seems to stretch a chain of young men and women rigid with tension.

As tension slowly swells up, it becomes ever more important to hold on to the things that truly matter.

A new cultural temperament is gradually engulfing post-apartheid urban South Africa. For the time being, it goes by the name “decolonization” – in truth a psychic state more than a political project in the strict sense of the term.

Whatever the case, everything seems to indicate that ours is a crucial moment in the redefinition of what counts as “social protagonism” in this country. Mobilizations over crucial matters such as access to health care, sanitation, housing, clean water or electricity might still be conducted in the name of the implicit promise inherent to the struggle years – that life after freedom will be “better” for all.

But fewer and fewer actually believe it. And as the belief in that promise fast recedes, raw affect, raw emotions and raw feelings are harnessed and recycled back into the political itself. In the process, new voices increasingly render old ones inaudible, while anger, rage and eventually muted grief seem to be the new markers of identity and agency.

Psychic bonds – in particular bonds of pain and bonds of suffering – more than lived material contradictions are becoming the real stuff of political inter-subjectivity. “I am my pain” – how many times have I heard this statement in the months since #RhodesMustFall emerged? “I am my suffering” and this subjective experience is so incommensurable that “unless you have gone through the same trial, you will never understand my condition” – the fusion of self and suffering in this astonishing age of solipsism and narcissism.

So it is that the relative cultural hegemony the African National Congress (ANC) exercised on black South African imagination during the years of the struggle is fast waning. In the bloody miasma of the Zuma years, these years of stagnation, rent-seeking and mediocrity parading as leadership, there is hardly any center left standing as institutions after institutions crumble under the weight of corruption, a predatory new black élite and the cynicism of former oppressors.

In the bloody miasma of the Zuma years, the discourse of black power, self-affirmation and worldliness of the early 1990s is in danger of being replaced by the discourse of fracture, injury and victimization – identity politics and the resentment that always is its corollary.

Rainbowism and its most important articles of faith – truth, reconciliation and forgiveness – is fading. Reduced to a totemic commodity figure mostly destined to assuage whites’ fears, Nelson Mandela himself is on trial. Some of the key pillars of the 1994 dispensation – a constitutional democracy, a market society, non-racialism – are also under scrutiny. They are now perceived as disabling devices with no animating potency, at least in the eyes of those who are determined to no longer wait. We are past the time of promises. Now is the time to settle accounts.

But how do we make sure that one noise machine is not simply replacing another?

Settling Accounts

The fact is this – nobody is saying nothing has changed. To say nothing has changed would be akin to indulging in willful blindness.

Hyperboles notwithstanding, South Africa today is not the “colony” Frantz Fanon is writing about in his Wretched of the Earth.

If we cannot find a proper name for what we are actually facing, then rather than simply borrowing one from a different time, we should keep searching.

What we are hearing is that there have not been enough meaningful, decisive, radical change, not only in terms of the life chances of the black poor, but – and this is the novelty – in terms of the future prospects of the black middle class.

What is being said is that twenty years after freedom, we have not disrupted enough the structures that maintain and reproduce “white power and supremacy”; that this is the reason why too many amongst us are trapped in a “bad life” that keeps wearing them out and down; that this wearing out and down of black life has been going on for too long and must now be brought to an end by all means necessary (the right to violence?).

We are being told that we have not radically overturned the particular sets of interests that are produced and reproduced through white privilege in institutions of public and private life – in law firms, in financial institutions such as banking and insurance, in advertising and industry, in terms of land redistribution, in media, universities, languages and culture in general.

“Whiteness”, “white power”, “white supremacy”, “white monopoly capital” is firmly back on the political and cultural agenda and to be white in South Africa now is to face a new-old kind of trial although with new judges – the so-called “born-free”.

Politics of impatience

But behind whites trial looms a broader indictment of South African social and political order.

South Africa is fast approaching its Fanonian moment. A mass of structurally disenfranchised people have the feeling of being treated as “foreigners” on their own land. Convinced that the doors of opportunity are closing, they are asking for firmer demarcations between “citizens” (those who belong) and “foreigners” (those who must be excluded). They are convinced that as the doors of opportunity keep closing, those who won’t be able to “get in” right now might be left out for generations to come – thus the social stampede, the rush to “get in” before it gets too late, the willingness to risk a fight because waiting is no longer a viable option.

The old politics of waiting is therefore gradually replaced by a new politics of impatience and, if necessary, of disruption. Brashness, disruption and a new anti-decorum ethos are meant to bring down the pretence of normality and the logics of normalization in this most “abnormal” society. Steve Biko, Frantz Fanon and a plethora of black feminist, queer, postcolonial, decolonial and critical race theorists are being reloaded in the service of a new form of militancy less accommodationist and more trenchant both in form and content.

The age of impatience is an age when a lot is said – all sorts of things we had hardly heard about during the last twenty years; some ugly, outrageous, toxic things, including calls for murder, atrocious things that speak to everything except to the project of freedom, in this age of fantasy and hysteria, when the gap between psychic realities and actual material realities has never been so wide, and the digital world only serves as an amplifier of every single moment, event and accident.

The age of urgency is also an age when new wounded bodies erupt and undertake to actually occupy spaces they used to simply haunt. They are now piling up, swearing and cursing, speaking with excrements, asking to be heard.

They speak in allegories and analogies – the “colony”, the “plantation”, the “house Negro”, the “field Negro”, blurring all boundaries, embracing confusion, mixing times and spaces, at the risk of anachronism.

They are claiming all kinds of rights – the right to violence; the right to disrupt and jam that which is parading as normal; the right to insult, intimidate and bully those who do not agree with them; the right to be angry, enraged; the right to go to war in the hope of recovering what was lost through conquest; the right to hate, to wreak vengeance, to smash something, it doesn’t matter what, as long as it looks “white”.

All these new “rights” are supposed to achieve one thing we are told the 1994 “peaceful settlement” did not achieve – decolonization and retributive justice, the only way to restore a modicum of dignity to victims of the injuries of yesterday and today.

Demythologizing whiteness

And yet, some hard questions must be asked.

Why are we invested in turning whiteness, pain and suffering into such erotogenic objects?

Could it be that the concentration of our libido on whiteness, pain and suffering is after all typical of the narcissistic investments so privileged by this neoliberal age?

To frame the issues in these terms does not mean embracing a position of moral relativism. How could it be? After all, in relation to our history, too many lives were destroyed in the name of whiteness. Furthermore, the structural repetition of past sufferings in the present is beyond any reasonable doubt. Whiteness as a necrophiliac power structure and a primary shaper of a global system of unequal redistribution of life chances will not die a natural death.

But to properly engineer its death – and thus the end of the nightmare it has been for a large portion of the humanity – we urgently need to demythologize it.

If we fail to properly demythologize whiteness, whiteness – as the machine in which a huge portion of the humanity has become entangled in spite of itself – will end up claiming us.

As a result of whiteness having claimed us; as a result of having let ourselves be possessed by it in the manner of an evil spirit, we will inflict upon ourselves injuries of which whiteness, at its most ferocious, would scarcely have been capable.

Indeed for whiteness to properly operate as the destructive force it is in the material sphere, it needs to capture its victim’s imagination and turn it into a poison well of hatred.

For victims of white racism to hold on to the things that truly matter, they must incessantly fight against the kind of hatred which never fails to destroy, in the first instance, the man or woman who hates while leaving the structure of whiteness itself intact.

As a poisonous fiction that passes for a fact, whiteness seeks to institutionalize itself as an event by any means necessary. This it does by colonizing the entire realms of desire and of the imagination.

To demythologize whiteness, it will not be enough to force “bad whites” into silence or into confessing guilt and/or complicity. This is too cheap.

To puncture and deflate the fictions of whiteness will require an entirely different regime of desire, new approaches in the constitution of material, aesthetic and symbolic capital, another discourse on value, on what matters and why.

The demythologization of whiteness also requires that we develop a more complex understanding of South African versions of whiteness here and now.

This is the only country on Earth in which a revolution took place which resulted in not one single former oppressor losing anything. In order to keep its privileges intact in the post-1994 era, South African whiteness has sought to intensify its capacity to invest in what we should call the resources of the offshore. It has attempted to fence itself off, to re-maximize its privileges through self-enclaving and the logics of privatization. These logics of offshoring and self-enclaving are typical of this neoliberal age.

The unfolding new/old trial of whiteness won’t produce much if whites are forced into a position in which the only thing they are ever allowed to say in our public sphere is: “Look, I am so sorry”.

It won’t produce much if through our actions and modes of thinking, we end up forcing back into the white ghetto those whites who have spent most of their lives trying to fight against the dominant versions of whiteness we so abhor.

Furthermore, we must take seriously the fact that “to be black” in South Africa now is not exactly the same as “to be black” in Europe or in the Americas.

After all, we are the majority here. Of course to be a majority is a bit more than the simple expression of numbers. But surely something has to be made out of this sheer weight of numbers. We can use this numerical force to create different dominant standards by which our society live; paradigms of what truly matters and why; entirely new social forms; new imaginaries of interior life and the life of the mind.

We are also in control of arguably the most powerful State on the African Continent. This is a State that wields enormous financial and economic power. In theory, not much prevents it from redirecting the flows of wealth in its hands in entirely new trajectories. As it has been done in places such as Malaysia or Singapore, something has to be made out of this sheer amount of wealth – something more creative and more decisive than our hapless “black economic empowerment” schemes the main function of which is to sustain the lifestyles of the new élite.

The neurotic misery of our age

Finally, it is crucial for us to understand that we are a bit more than just “suffering subjects”. “Social death” is not the defining feature of our history. The fact is that we are still here – of course at a very high price and most likely in a terrible state, but we are here.

We are here – and hopefully we will be here for a very long time – not as anybody else’s creation, but as our own-creation.

To demythologize whiteness is to dry up the mythic, symbolic and immaterial resources without which it can no longer dabble in self-righteousness or in the morbid delight with which, as James Baldwin put it, it contemplates “the extent and power of its own wickedness.” It is to not be put in a position in which we die hating somebody else.

On the other hand, politicizing pain is not the same thing as advocating dolorism. In fact, it must be galling to put ourselves in a position such that those who look at us cannot but pity us victims.

One way of destroying white racism is to prevent whiteness from becoming a deep fantasmatic object of our unconscious.

We need to let go off our libidinal investments in whiteness if we are to squarely confront the dilemmas of white privilege. Baldwin understood this better than any other thinker. “In order really to hate white people”, he wrote, “one has to blot so much out of the mind – and the heart – that this hatred itself becomes an exhausting and self-destructive pose” (Notes of a Native Son, 112).

This is what we have to find out for ourselves – in a black majority country in which blacks are in power, what is the cost of our attachment to whiteness, this mirror object of our fear and our envy, our hate and our attraction, our repulsion and our aspirations?

Part of what racism has always tried to do is to damage its victims’ capacity to help themselves. For instance, racism has encouraged its victims to perceive themselves as powerless, that is, as victims even when they were actively engaged in myriad acts of self-assertion.

Ironically among the emerging black middle class, current narratives of selfhood and identity are saturated by the tropes of pain and suffering. The latter have become the register through which many now represent themselves to themselves and to the world. To give account of who they are, or to explain themselves and their behavior to others, they increasingly tend to frame their life stories in terms of how much they have been injured by the forces of racism, bigotry and patriarchy.

Often under the pretext that the personal is political, this type of autobiographical and at times self-indulgent “petit bourgeois” discourse has replaced structural analysis. Personal feelings now suffice. There is no need to mount a proper argument. Not only wounds and injuries can’t they be shared, their interpretation cannot be challenged by any known rational discourse. Why? Because, it is alleged, black experience transcends human vocabulary to the point where it cannot be named.

This kind of argument is dangerous.

The self is made at the point of encounter with an Other. There is no self that is limited to itself.

The Other is our origin by definition.

What makes us human is our capacity to share our condition – including our wounds and injuries – with others.

Anticipatory politics – as opposed to retrospective politics – is about reaching out to others. It is never about self-enclosure.

The best of black radical thought has been about how we make sure that in the work of repair, certain compensations do not become pathological phenomena.

It has been about nurturing the capacity to resume a human life in the aftermath of irreparable loss.

Invoking Frantz Fanon, Steve Biko and countless others will come to nothing if this ethics of becoming-with-others is not the cornerstone of the new cycle of struggles.

There will be no plausible critique of whiteness, white privilege, white monopoly capitalism that does not start from the assumption that whiteness has become this accursed part of ourselves we are deeply attached to, in spite of it threatening our own very future well-being.

September 18, 2015

Weekend Music Break No.83 – Banned in Nigeria edition

This summer Nigeria’s Broadcasting Corporation, or whoever is in charge of censoring content there, decided to ban 18 pop songs from its outlets for either containing “vulgar lyrics,” “obscene video” or something else. What is interesting is that except for two songs by Omarion featuring Chris Brown and Jhene Aoki (“Post to Be”) and Nicki Minaj (“Anaconda”), most of the songs are by Nigerian pop stars. Musicians like Davido, Naeto C, Olamide, Wizkid, etcetera have seen their music banned. Which makes us conclude, that for all that talk of Nigerians as a chaste, church going lot (the view that the government and governing elites want to convey), they’re not that innocent.

In any case, while the music is banned on the public airwaves, they can still be played in clubs or in your car or streamed on your phone. So here, dear reader are those 18 songs as a #WeekendMusicBreak.

#DigitalArchives No. 19: ‘Claremont Histories’ and the preservation of nostalgia

So far, a lot of what has been covered in this series has focused on digitized archival sources or social justice projects. The preservation of nostalgia has not received as much attention (with the exception of Nigerian Nostalgia), though the digital realm has opened up new vistas for collective remembering. This nostalgia comes in many forms, from private messages on social media to chat rooms to more official projects like this week’s featured site, Claremont Histories. Focusing on the Cape Town, South Africa, suburb of Claremont and the struggles in this neighborhood following its designation as a white area under the Group Areas Act, this site pulls together photos, texts, and newspaper clippings to bring the history of Claremont to life. The main focus, however, is on the memories of the Claremont residents who contributed their photos and memories to the site. This focus is communicated clearly in the mission statement of the site.

I want to tell you a story. Or rather, a thousand stories. Stories about Claremont, the area now known as Harfield Village. Our stories are our memories, and they make us laugh, make us cry. This site is a dedication to those who lived in and share wonderful memories of Claremont before the forced removals under the Group Areas Act. They’re not all happy memories, but we would like to share both the good times and the bad. So that we don’t forget – so that nobody forgets – about the colourful, beautiful, difficult and vibrant lives of the people of Claremont.

You can navigate the content on the site in a variety of ways. You can browse through examples of the good stuff (pleasant nostalgic memories of Claremont residents) or some of the bad stuff (more unpleasant memories of forced removals and racism). You can also explore the memories of Claremont through the biographies and reminiscences of residents themselves, like Salegga Mustapha, who was raised in Claremont and is still actively involved in the neighborhood through the Claremont Re-united Alliance. Mustapha was also one of the contributors who loaned out a number of photos and artifacts for inclusion in the site, which you can view in her gallery. There is also a gallery of newspaper clippings that could provide a jumping off point for anyone interested in researching the history of this Cape Town suburb.

Salegga on York Street, Claremont

Follow Claremont Histories on Facebook and, if you have your own memories of Claremont, you can contribute via the Contact page on the site. You can also learn more about Claremont on South African History Online. As always, feel free to send me suggestions via Twitter (or use the hashtag #DigitalArchive) of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

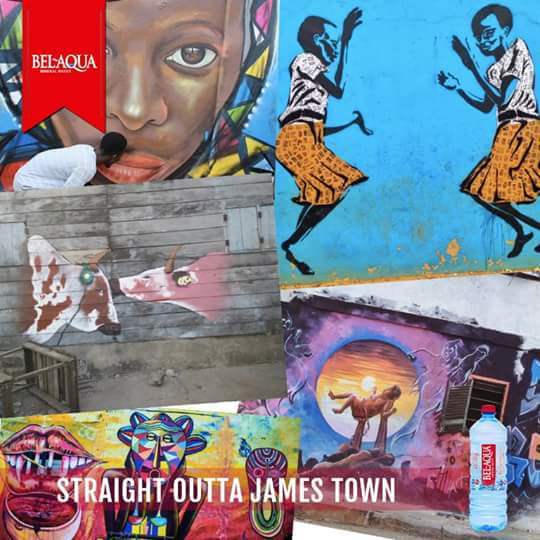

Ghana’s CHALE WOTE Street Arts Festival and the corporations

The CHALE WOTE Street Art Festival in Accra has grown over the last four years, expanding to new audiences in Ghana and across the world, particularly through social media and word of mouth. In 2015, the crowds came out in full speed and so did the corporations.

Local authorities estimate that more than 30,000 people participated in the now four-day event, a fact that clearly appealed to at least five multi-million cedi companies who set up shop ad hoc at the festival without prior approval or authorisation from the festival organisers.

The companies that targeted the 2015 festival without going through the proper procedures of vending, include Red Bull, Vodafone, Hello Foods, Blue Skies and Bel Aqua.

Red Bull vendors gained unauthorized entry into the festival and left branded cars at the entrance on Sunday, August 23. Vodafone vendors walked through the festival wearing branded vests selling recharge cards to customers. Hello Foods employees wore branded T-shirts and passed out flyers to festival-goers. Blue Skies set up a vending truck at the entrance of Seaview Hotel on Sunday, August 23 after being told several times by the organizers to leave. Bel Aqua took images from the festival and created an advertising campaign on their social media platforms branding their water.

What makes these exploitive practices even more appalling is that more than fifty small to large-scale businesses were legitimately represented at the festival as vendors in food, fashion, design and technology, having paid for space to operate and share their products and services with patrons.

This kind of corporate exploitation isn’t new to the arts on the continent though. There’s a long global history of well-resourced companies hijacking work and recognition from artists in order to sell to customers. Particularly on the continent, it is a difficult terrain for art creators who must navigate life often with little or no financial support for their work.

Many corporations operate quite differently when they do business on the continent. Africa is seen as a resource extraction mine and the relationship with art is no exception. In many ways, artists in Ghana are treated no differently than mine workers who are far removed from actually enjoying the profits obtained from mineral production. Art is also a natural resource that can transform the life of a nation. An art economy is developing in Accra, and albeit small, it is also consistent. All the more fascinating is how such developments are largely happening outside of state and corporate support.

Ghana is on the verge of a cultural economy explosion and artists have been the center of this shift, creating a new eco-system and network for creative entrepreneurs. CHALE WOTE is an independent structure, built through the energetic efforts of groups of artists, to ensure it takes off each year.

So when high net worth companies gain unauthorized entry into the festival and market their products and services to attendees, it demonstrates a lack of respect for the festival and participating artists. This is evident in their unwillingness to pay for rightful access to the festival or the use of works by artists. Would these companies try such things within the western countries they also do business?

For CHALE WOTE, this is not the first time we have encountered this phenomenon. Last year, after negotiations went sour with Guinness, the company hired bloggers to attend the festival and snap photos of the artwork and events, as a way to add fuel to the #madeofblack campaign launched in Ghana the following week. Airtel Ghana also used a mural created by Jason Nicco-Annan during CHALE WOTE 2014 in a commercial that has been screening since last October. Unfortunately, neither the festival organisers nor Nicco-Annan were contacted for permission to use this work in the commercial.

Such actions, particularly by big business, exhibit a blatant sense of entitlement to the work of artists who are, in turn, treated with neglect and impunity. This amounts to theft, a persistent stealing of the intellectual property and livable wages entitled to artists. This dishonest practice does not acknowledge the time, energy, and cost that the organisers and artists have committed to the realisation of CHALE WOTE each year. The artists are often not recognized by name, their work is not portrayed accurately, and they are not contacted for payment for the use of their work in commercial advertising.

What’s even more disturbing is how images are lifted easily and associated with products and services that may be misaligned with the artist’s intentions and morals. Artists’ messages are being compromised through association with the selling of particular products Furthermore, why is consent not the first place to start? It is it not okay to continually take from artists without any recourse.

The exploitative behaviour of corporations goes against the very vision and mission of the CHALE WOTE Street Art Festival, which is to provide a platform to Ghanaian artists to create, collaborate with international artists, exhibit and make a livable wage from their work.

We’re left with no choice but to call out these predatory capitalist practices for what they are. Cease and desist with the tomfoolery corporations. African artists are not pawns.

Working alongside many others, we are relentless in our pursuit of justice.

September 17, 2015

For the first time, an Ethiopian film was selected for Cannes. We interview director Yared Zeleke

Cinematographer Yared Zeleke is making Ethiopia proud. The movie Lamb – both written and directed by Yared – is the first Ethiopian film to have ever been selected for the Cannes Film Festival.

Lamb is the first feature film for 37-year old Yared, who studied at New York University’s film school. The world premiere was held on Thursday night in Ethiopia’s National Theatre in capital city Addis Ababa. The story is about a 9-year-old boy who loses his mother due to drought. His father decides to find work in the city and leaves him with relatives. The Guardian has described the film as an “ethnographic film made entirely from the inside out.” We caught up with Zeleke in Addis Ababa after the premiere.

How do you relate to the main character?

I relate to the main character, as far as I also had a childhood full of love and color but I was separated from my childhood-home age nine, right before I turned ten. It was during the time of the Derg* and my father had already escaped to the U.S. It was natural for my family to want to send me to join my father because of better education, better opportunity. But for me it was a nightmare. Because I left behind everybody I loved, and everybody I knew. I left my home. And that little kid in me is heartbroken. That’s some of the main themes in the story, about how a child deals with loss.

Drought and hunger play a central theme in your movie. Why would you choose subjects that have stereotyped Ethiopia for decades?

When I went to the U.S., a lot of times people would think I’m from the desert and I was starving and things like that. I grew up having to defend who I was as a child. I play with this cliché in this film. Because the majority of the images you’ll see is green beautifully lush green landscape, and a lot of the narrative is driven by food.

Another important topic to the livelihoods of the characters seems to be rainfall, or the lack thereof.

Ethiopia is experiencing a changing climate. There is a debate in some parts of the United States, but here in Ethiopia it’s a reality. 85% are still farmers. So it’s not even a debate, it’s a reality. Our country was once very forested, very green. Today it’s mostly deforested, but outside of that, the pollution from wealthier countries is causing havoc on the lives of farmers here.

Never before has en Ethiopian movie been officially selected for the Cannes Film Festival. How was it to receive the news of your selection?

It was one of these really exhilarating rare moments in your life. It’s like natural sort of high, and a real honor and real blessing to be selected and at the same time to represent Ethiopia. In Cannes, when a film is selected it’s like the Olympics, you represent the country.

How would you describe Ethiopia’s film industry?

Ethiopia’s film industry is developing and I’ve seen much improvement actually in the past seven years that I’ve been coming back and forth. Of course there is room for improvement and I hope to contribute. In the future I would like to teach and also screen films from around the world. We have 3000 years of incredible extraordinary history, beautiful culture and landscape, beautiful people. That should be shared with the world, they should know that Ethiopia is worth looking into.

Will all your movies be about Ethiopia?

I think so, even I made a film in the US which I think I will at one point, it will have some Ethiopian elements. At least, Muleken Melesse’s music or something.

You used the music of different Ethiopian musicians for the movie Lamb.

I really go out of my way to discover and rediscover Ethiopian music. Some people prefer the old, some youth are listening to contemporary but I listen to everything. A lot of times people give credit to the old ones but there is some incredible new stuff out there. There are ten songs, contemporary mostly, in my film now and there will be more to come in the future. I want to make Ethiopia cool, because it is. This country is a dream for an artist because it still has so much soul.

What will be your next project?

My next film is all about youth because Ethiopia is a very youthful nation. I also want to do something really cool so that the youth don’t loose that sense of identify because Ethiopia is one of the places on earth where identity is still strong and its beautiful. We don’t have McDonalds or anything like that. I want to maintain our cultural diversity, our religious diversity and our sense of beautiful identity.

Zeleke, Image credit: Manhattan Digest

The movie “Lamb” will be released in 15 countries, including Turkey, Germany, France, Switzerland, Taiwan, the UAE, Mexico, and Norway.

*The Derg was the military regime under the leadership of Mengistu Hailemariam who overthrew emperor Haile Selassie in 1976. The Derg is considered Ethiopia’s most brutal regime in history.

September 16, 2015

Black Magic Women: Ancient, new, and circum-Atlantic

Before we hear her commanding voice, we feel her power buffeting two bible-carrying pastors who’ve accosted a young woman, talking on a phone, walking down a pathway. As they invade her personal space, we hear an insistent beat, first soft, then gaining force. It deflects the chasing proselytizers; the pursued woman escapes into the foreground. We are swirled into an alternate universe. Out of the mist in a jungle clearing she looms, sitting on a throne flanked by drummers, wielding sceptre, face paint, and megaphone.

Thus begins the new music video, ‘Black Magic Woman’, by Azizaa, ‘Ewe from Ghana soaked in the American pop culture by living here for over twenty years’. Produced by Wanlov the Kubolor, half of the Fokn Bois and an artist in his own right, it cannot but be provocative. The video’s address is Ghana, and contemporary West Africa. But its remit is wider: the repossession of time itself through a feminist reclaiming of the sacred.

The already scrambled time of African modernity is visually communicated through the bibles, men clad in shirts, ties, and trousers, and woman on a mobile phone. But murkier, more jumbled-up temporalities await in the jungle. The Black Magic Woman’s ‘ancient mind’ is ‘dreaming of aliens from the sky’ as did Sun Ra; the electronic pulse dialogues with percussionists; the bullhorn and megaphone are both prostheses of power. This mash-up of the ‘jungle’ and the sonic-lyric registers of Afro-futurism decolonizes the forward march of secular, factory, colonial time. As Azizaa says, ‘my music is a bridge between the ancient and the modern, the present and the future.’

It’s also a bridge between West Africa and the Americas. The last time a Black Magic Woman was invoked in a memorable song, it was Carlos Santana’s: ‘put a spell on me, baby’—an avatar of the exotic. As the ‘Black Magic Woman’ returns to the African Jungle, the pasts of slavery and colonialism meet the present of postcolonial West Africa. Christianity’s eschatology, a possible escape route from modernity’s metronome, is rejected as a legacy of colonialism and empire. Contemporary African Christianity is exposed as complicit with the restriction of women’s mobility and independence. Where is a spirituality that can decolonize the soul while empowering women? It’s in indigeneous West African spirituality that she finds the answer.

Not for Azizaa, however, a tidy nativist indigeneity, but the re-assemblage of cultural resources already re-assembled in New World diasporas. ‘A voodoo priestess who creates voodoo music that is essential to my spiritual wellbeing,’ Azizaa is also the ‘daughter of Oshun’ (one of the female powers of the Afro-Cuban pantheon). Eschewing Hollywood–style voodoo with its dolls and hexes, her music, ‘spiritual but light-hearted, with a hint of sarcasm’, draws from female divinities with Yoruba roots, diasporic agencies, and various caprices and demands. Their auras range from the dark to the lighter; In Azizaa’s Black Magic Woman, possessor equally of ‘darkness’, ‘dragon’s breath’ and a sexy beauty, we see the dangerous Erzulie Dantor, the coquettish Erzulie Freda, the jewellery-loving Oshun, and the ‘supersyncretised’ Yemaya/ Lemanja/ Mami Wata: unpredictable Black Magic Women all, aliens from the sky, washed up on Black Atlantic shores.

Azizaa reclaims ‘voodoo’ from both the Afro-diasporic imaginary and Ghanaian pentecostalism: ‘”Vodou” means “free the people” in Ewe. So my music is for the free souls and minds.’ West African musical reinterpretations of Black Atlantic spirituality’s diasporic afterlives are a long-standing phenomenon. Cultural producers from across the region insist that ‘salsa came from here’, or that the ‘clave’, the signature rhythm cell of Cuban music, can be traced back to a village in Mali or Benin. This transatlantic cosmopolitanism evades imperial histories through affective strategies of reparation and reconnection: note, for instance, the ‘vodou-funk’ of Benin’s Orchestre Poly-Rythmo de Cotonou.

Azizaa updates this trend with a feminist reworking of transatlantic voodoo and the nativist trope of the ‘Afro-tribal’. The Black Magic Woman also answers back to Chinua Achebe’s magisterial novel, Things Fall Apart, whose descriptions of the drums are set in a pre-colonial past thanks to realism’s collusion with linear narrative. Azizaa’s video is an aural-visual-percussive riposte to Achebe’s evasiveness regarding Christianity and female agency. Her use of English is welded to spoken word traditions and to the ‘Africa’ of the ribcage, thorax, and solar plexus. Watch how, at 4.22-2.29 in the video, body movement transmits the Black Magic Woman’s majesty as embodied, kinetic, and ‘African’, capable of ‘reconverting’ evangelist and pastor.

Ex Africa aliquid semper novi — from Africa always arises something new for the world. Aziza’s pocomagicmix of a video gives a new twist to strategic essentialism through its audacious and hypnotic power.

All descriptions of Azizaa’s music and cultural influences are taken from the author’s correspondence with her. Thank you, Azizaa.

September 14, 2015

#RespecTheProducer | Awesome [Beat] Tapes From Africa!!!

Sabelo Mkhabela is an emcee caught in limbo. Currently, he’s a functional as a writer wading his way through Cape Town alleways with headphones fully locked and loaded. When not contemplating whether or not to drop another mixtape — his music is on Soundcloud — he likes listening to beats of all kinds. Generally, he prefers ones with a boom and a bap and a clack-clack, accompanied warm, woozy synth pads, or abrasive, crackly, cranky snares drums. So we asked him to pick a selection of some beat tapes in his possession and write about them. This article is part of a series on music producers throughout the African continent called #RespecTheProducer. Check out daily updates on tumblr and follow the Instagram account.

*

Just before meeting with Cape Town hip hop duo Ill Skillz, producer J-oNE did something amazing when he released a beat tape consisting of beats he had made on [the beat-making software] Fruity Loops 9 (FL9). He made all the beats in December 2011 in Pretoria on his little brother’s laptop. “I had no beatmaking equipment at the time so I jumped on my nigglet’s laptop, gathered the few drum samples I had on my external hard drive, installed Fruity Loops 9 and just did what it does,” said the producer in an interview I did with him about two years ago. The tape is packed with soothing Rhodes keys, ambient pads unobtrusively creeping behind warm basslines and varied rhythms. The beats sound full, yet still leave space for vocals. This explains why some of them ended up on Ill Skillz’s Notes from the Native Yards album. “Cyber Lust” with its soaring pads and perennial bassline became “Fuck Your Day Job”. The sax-led “” with its heavy drums and club-ready chants became the banging “2 Dope Boyz”. The organ squelches on “Crate Break – Short Word From Our Sponsors” made for a perfect canvas for Uno and Flexx to throw tirades at the system on “Give Us Free”. On The All Fruity Loops Tape, J-oNE showcased some of the various beatmaking styles he is able to pull off. The warm and damp “The Dilla Joint” – my personal favorite – saw J-oNE recreating Dilla’s neo-soul signature sound backed by those creaking vinyl sounds. He even managed to emulate Dilla’s plodding drums and uniform arrangement giving a Dilla fan like myself goose bumps all over. J-oNE succeeded at merging smooth ambient pads and lively percussion making this a perfect backdrop for dreams and musings.

Namibian producer Becoming Phil is an anomaly on All Sorts Vol. 1. He offers a variety of sounds — familiar and rare samples alike. Sample-spotters will recognize most of the tracks being re-imagined by the producer. Phil’s chops and loops are basic. He excels in blending them with the subtle synthesizers he uses on some of the beats. All Sorts Vol. 1 is a light listen, where the samples lead, Phil prefers his drums smooth. Even when they attempt to thwack, he has a way of keeping them in the background. The tape left me feeling nostalgic. The soundscape consists mostly of breezy production reminiscent of the 90s. A variation in rhythm makes sure you bob head differently to almost every beat. And at 30 tracks, the tape’s guaranteed to have something for everyone.

Namibian producer Becoming Phil is an anomaly on All Sorts Vol. 1. He offers a variety of sounds — familiar and rare samples alike. Sample-spotters will recognize most of the tracks being re-imagined by the producer. Phil’s chops and loops are basic. He excels in blending them with the subtle synthesizers he uses on some of the beats. All Sorts Vol. 1 is a light listen, where the samples lead, Phil prefers his drums smooth. Even when they attempt to thwack, he has a way of keeping them in the background. The tape left me feeling nostalgic. The soundscape consists mostly of breezy production reminiscent of the 90s. A variation in rhythm makes sure you bob head differently to almost every beat. And at 30 tracks, the tape’s guaranteed to have something for everyone.

[Note: The beats were mixed by Nyambz, whom we’ve written about here]

With production credits on one of the most talked about albums of 2014 – AKA’s Levels, Tweezy didn’t need a beat tape to “get his name out there”. He is the man behind AKA’s massive hits like “All Eyes on Me”, “Run Jozi” and what I believe to be one of his best beats, “Sim Dope”. But Tweezy felt like showing the world that he could do more than just make bangers, that’s why he released the God Level EP mid-2014. The tape kicks off with an ear-drum wrecker, “Pata Pata” where the producer samples Miriam Makeba’s tune of the same name. He plugs Mama Afrika’s vocals into a circuit of regular 808s, high-time hi-hats and a low-octave electronic bassline. The beat takes off where “All Eyes on Me” left off; it could be a beat AKA left out. For the first half, Tweezy brings pulverizing basslines and layers an assortment of synthesizers on top of them. It’s a turn up! On the second half, he reveals another side of his we haven’t heard: Mellow keys and subtle electronics which sit on smooth, friendlier basslines. The beats, however soulful, are still catchy. Tweezy’s strongest traits are his basslines – they are full and loud but are not painful at all! Just dense. And firm. His mixing abilities put many vets to shame; all the sounds he uses exist in their own, distinct frequency. It’s no surprise, then, that AKA roped him in for Levels. The rapper needed Tweezy more than Tweezy needed the rapper.

Clean Thoughts and Dirty Beats is an on-going series by Hipe. The Cape Town producer releases instrumentals that artists – Cream, Jaak, Rattex, Imbube, Ben Sharpa, The Anvills and more – have jumped on before. The first volume, which hasn’t been followed up in two years, attempts to sum up Hipe’s career. It’s a story for another day if it does succeed in that department. What the compilation does is showcase the producer’s versatility and cements his legacy in the South African hip hop scene. From blunt soul chops to Hipe’s signature horn loops, and the prevalent head-bopping boom bap rhythm, the tape teleports you into the Hyperbolic Chamber (Hipe’s production enclave). What you find there is virtuoso use of the MPD drum machine, Hipe’s beats are purely organic; no PlayStation sounds here! Though boom bap is a wholesale sound, where the only attempts at innovation have been merging the 90s’ style of beatmaking with electronic elements (think Black Milk and 88 Keys), Hipe has mastered his own technique. In his work, you hear a lot of familiar sounds, just sounds you haven’t heard in one beat. Take Jaak’s “Sweet” for example, where Hipe loops accordion riffs over his melodic bassline. He does throw in some exclusive pieces sporadically between the familiar instrumentals, ranging from his interpretation of Nigerian traditional music, to some flirtations with 70s and 80s soul and pop. A lot of regular boom-bap beats (“Bass & Kicks”) show up somewhere along the line. But mostly Hipe keeps things interesting, as each track comes with its own mood, from the ominous “Intergalactic Crew” to the breezy “Ill Vibe Music” by emcee Mingus, and straight street (“Welcome to Khalcha” by Rattex). Not forgetting the skittering drums on “Slew Them” which suite whatever mood you are in. Maybe Hipe’s kind of production is not making waves on mainstream radio stations such as 5FM and YFM. But that doesn’t anyone from appreciating it.

Clean Thoughts and Dirty Beats is an on-going series by Hipe. The Cape Town producer releases instrumentals that artists – Cream, Jaak, Rattex, Imbube, Ben Sharpa, The Anvills and more – have jumped on before. The first volume, which hasn’t been followed up in two years, attempts to sum up Hipe’s career. It’s a story for another day if it does succeed in that department. What the compilation does is showcase the producer’s versatility and cements his legacy in the South African hip hop scene. From blunt soul chops to Hipe’s signature horn loops, and the prevalent head-bopping boom bap rhythm, the tape teleports you into the Hyperbolic Chamber (Hipe’s production enclave). What you find there is virtuoso use of the MPD drum machine, Hipe’s beats are purely organic; no PlayStation sounds here! Though boom bap is a wholesale sound, where the only attempts at innovation have been merging the 90s’ style of beatmaking with electronic elements (think Black Milk and 88 Keys), Hipe has mastered his own technique. In his work, you hear a lot of familiar sounds, just sounds you haven’t heard in one beat. Take Jaak’s “Sweet” for example, where Hipe loops accordion riffs over his melodic bassline. He does throw in some exclusive pieces sporadically between the familiar instrumentals, ranging from his interpretation of Nigerian traditional music, to some flirtations with 70s and 80s soul and pop. A lot of regular boom-bap beats (“Bass & Kicks”) show up somewhere along the line. But mostly Hipe keeps things interesting, as each track comes with its own mood, from the ominous “Intergalactic Crew” to the breezy “Ill Vibe Music” by emcee Mingus, and straight street (“Welcome to Khalcha” by Rattex). Not forgetting the skittering drums on “Slew Them” which suite whatever mood you are in. Maybe Hipe’s kind of production is not making waves on mainstream radio stations such as 5FM and YFM. But that doesn’t anyone from appreciating it.

Nigerian emcee and producer Teck-Zilla released Son of Sade in 2014. He released it on his mother’s birthday, whose name is Sade. He sampled Nigerian singer Sade’s songs for all the six beats on the project. Sade’s music is rich. This gave the producer plenty of sounds – keys, saxophones, and of course, her woozy vocals – to chop. Teck is inspired by the golden era of hip hop; it’s written all over his work. He prefers the boom-bap sound, but can also appreciate that we are living in the 21st century. On “Dream Weaver”, he throws thwacking 808s over a saxophone loop and still manages to keep the soul seeping through. Most boom-bap projects tend to fail to keep the listener interested, but Son of Sade is a monolithic offering whose brevity ensures it doesn’t get monotonous. The producer is not a novice. The clarity of his samples and the crispness and accuracy of his drums is impressive. This is the kind of beat tape that has you thinking of flows and concepts. My personal favourite is “Theme to S.O.S”, I even rapped over it.

Mokhele Ntho (also known as Suade Ritchie) is a soft-spoken introvert, the perfect personality for a producer. He’s the kind to spend hours indoors tapping on his Akai MPD26 drum pad, eyes fixed on the computer screen. He lives in his own world; a world that excites him; a world you have to understand, in order to understand him. I met Mokhele while we were both university students. He played me some of his beats in his room in Liesbeeck Gardens one afternoon. He had a story to tell about each and every beat he played. When he shot me a link to BlackWindows.WhiteRoses, I was excited! The brief project is the perfect backdrop for cold winter nights spent alone. The beats have Mokhele’s personality written all over them – the aeriform pads over basslines so healthy and so sure of themselves they seem to have a life of their own. His basslines are my favourite aspect of his production, not to say anything else is any bad. They are highly textured, and it doesn’t take a scrupulous ear to pick up the evidence of the thorough and calculated tweaking that went behind creating them. The project is tied together by a uniform sound yet it doesn’t sound monotonous. It sounds like storytelling without words. The producer made the project in two months, ensuring that each beat led into the next. “I repeatedly played the previous beat I had made over and over before I moved on to next one to maintain consistency between the track in order for the project to have unity and sound like a single project,” he said when I spoke to him. “The way the tracklist is setup is exactly the order of creation, I didn’t follow a selection process – I didn’t make trillions of beats then picked from them.” My personal favourite is “Fear of Dolphins”, the violin towards the end of the beat cuts deep, makes you think about your past, present and future. Mokhele has a way of making soulful sound cool!

Reflections on the state of LGBT activism in Africa

In 2014 at an annual summit of the African Union, Joachim Chissano – former head of state of Mozambique – made a declaration in which he called African nations to uphold the rights of all citizens, including sexual minorities, and consider the decriminalization of certain forms of sexual relationships between consenting adults. The speech may have caused a stir in that assembly room in Addis Ababa, but it hardly made headlines outside of Lusophone Africa. One year later, Mozambique would be amongst the first African countries to decriminalized homosexuality by removing penal sanctions inherited from its former Portuguese colonizer.

Despite the good news from Mozambique, many African governments continue to either ignore the issue of sexual discrimination amongst its citizens, or actively enact repressive policies and laws to punish sexual relationships between people of the same gender. The debate has become an internationally polarizing one, playing out in mainstream press, and in settings such as the United Nations General Assembly or the Human Rights Council. Sometimes eclipsed by the debates going on in these high profile arenas, it is worth noting that positive steps towards LGBT rights are also happening locally across the continent.

Contrary to what the international media would have you believe, there have been narrow windows opening for LGBT Africans in the past decade. These changes have occurred in legislation, judiciary decisions, courts, health policies and more importantly in shifting public opinions among the youth. There are lessons to be learned and numerous Africans to be praised for championing change.

In Botswana and Kenya, after years of challenges by local activists, court authorities have given LGBT organizations permission to operate within civil society. In 2004, Cape Verde decriminalized consensual relations between adults under the leadership of Pedro Pires, and Sao Tome & Principe also decriminalized homosexuality in 2013. In Rwanda, politicians and President Kagame himself have refrained from supporting a bill to criminalize homosexuality, unlike their immediate neighbours.

Gay pride events, which constitute the visible side of LGBT political mobilization in the West, are still an extremely rare occurrence on the continent (with the exception of South Africa). However, activists in countries such as Uganda and Mauritius have held Pride events in recent years (albeit in covert ways). In Cape Verde, the city of Mindelo now holds an annual street party where LGBT people and allies celebrate together.

The work of local LGBT groups and human rights defenders is crucial in spearheading the policy changes that we are beginning to witness. A growing number of LGBT organizations are documenting cases of violence and discrimination occurring in communities. In Nigeria for instance, human right defenders publish data on violations against LGBT people occurring in workplaces, families, police stations, housing, schools or healthcare institutions. This evidence is then used to lobby national human rights institutions — often with little success – as most national human rights institutions do not recognize LGBT rights as priority. However, the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) has started to take note of our work. In 2014, it broke its silence on the matter by issuing its first ever resolution LGBT rights. Resolution 275 explicitly condemns violence against LGBT people noted across the continent, and calls for states to protect human rights defenders working with sexual minorities. Another notable win was the formal offer of observer status granted to the Coalition of African Lesbians this year.

Africa’s response to AIDS is also gradually giving attention to LGBT issues. Most countries now specify in their AIDS policies, the need to target men who have sex with men as priority groups. However, public health efforts are hampered by punitive laws against homosexuality that exist in 38 African countries. Negative public opinion further drives gender and sexual minorities underground and creates a climate of fear.

Training sessions on gender and sexual diversity are now delivered in the health sectors of most African countries. These programs often explore the impact of apathy, prejudice, stigma and discrimination toward sexual minorities. Among the health officials and providers taking part, it is common to see professionals struggling to name a single ally of LGBT people in their country. Gender experts admit that they have never met transgender people from their country. They readily admit that the root of stigma and discrimination — and the laws which entrench them — are rooted in ignorance, and the strict gender norms which prevail in our countries. This is at least a step forward.

The visibility of LGBT people comes at a high price, and many activists still fear to speak openly. But recent surveys show that attitudes are shifting. For example in Nigeria, one survey showed that acceptance of LGBT people is far higher among younger Nigerians. New ways of resistance are flourishing in the arts as well; writers like Abdallah Taia, Binyavanga Wainaina, Chimamamnda Ngozi Adichie, photographers like Zanele Muholi and poets like Diriye Osman are breaking boundaries and giving voice to previously hidden narratives. African scientists are also now joining the debate, The Uganda Academy of Sciences now recognizes that gender and sexual identity are “part of a continuum and that no positions on this spectrum are “unnatural”” – despite what President Yoweri Museveni and a proposed Ugandan law have claimed. The point is, Africa has always been a place of resistance to all forms of oppression. And beyond what the mainstream media would have you believe, the current direction of LGBT rights dialogues in several African countries should give us reason to hope for a better and more positive future for Africans of all stripes.

September 12, 2015

Weekend Music Break No.82 – Catch up edition!

Africa is a Country has been on break for about a month, and in that time we’ve accrued a bit more videos than the usual ten we post for our Weekend Music Break. So as we make our way back into our posting stride, enjoy the following set of twenty-five videos from across Africa and its diaspora:

It feels good to be back!

At the Heart of the West Indies Parade

In New York City, Labor Day is associated with the West Indies Carnival. This enormous parade is a magnetic force that attracts, on average, one million spectators every year. It is not a space to talk about labor or exploitation. It is a massive celebration of Caribbean culture and heritage.

The carnival takes place in Crown Heights, East Flatbush, and other surrounding neighborhoods of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, where many West Indian families are resisting gentrification. Mists of smoke grill and the strong aroma of curry surrounds the parade. While people eat, trucks loaded with speakers blast every possible genre of Caribbean music, from reguetón club hits to hip-shaking gospels. This creates an ambiance carnivalesque unrivalled by other festivities in any of the five boroughs of the city.

This carnival used to take place in Harlem––once a beacon of African American culture and African heritage in the US. Harlem lost the permit to host the carnival in 1964 due to disturbances. A fact that is perhaps more telling of the political climate than of what the carnival has represented throughout its history: imagine the plausible occurrence, in the minds of officials, of an energetic celebration of African heritage and miscegenation, joining forces with the then growing protests spurred by the Civil Rights Movement.

But the Carnival resisted, and it moved to Brooklyn. A less known festivity that is paired with the carnival, J’Ouvert (or Jouvay, which is creole for open day) breaks out at midnight with drums playing on Flatbush Avenue and then disperses until the dawn of Labor Day. This festivity is not only of great importance due to its ritual significance, but also because it is celebrating the emancipation from slavery. The festivity is tied historically to representations of disruption of social norms and the establishment.

While mainstream media tends to focus on episodic gang-related violence surrounding the carnival (especially during Jouvay), this photo essay attempts to portray the many facets of this massive celebration. Cultural pride, diversity, familial and ancestral ties are at the heart of this parade. Not to mention a surge of creativity.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers