Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 327

October 7, 2015

The year of the girl child in Tanzania?

October 11 is International Day of the Girl Child, and October 25 Tanzania will run Presidential and Parliamentary elections. The presidential elections, in particular, will or will not be the closest ever, depending on which poll one prefers, but one thing is clear: youth matters. According to the 2012 Census, of the close to 45 million people living in Tanzania, 44.1 percent of the population is `young’, under fifteen, and 35.1 percent are `youth’, 15 – 35 years old. 79.2 percent of Tanzanians are young or youthful. The future is now.

Perhaps it’s the young and the restless or the elections, or maybe the prospect of a new constitution which could expand the rights of women and girls, or perhaps reflecting on the International Day of the Girl Child that has Tanzania’s Daily News running a series of articles encouraging its readers to get serious about ending child marriage now.

For a variety of reasons, the rates of `child marriage’ in Tanzania are famously high, although according to some they have been descending slowly over the past decade. Just about every year, a `major’ study reports on the situation of `child marriage’ and `girl-brides’ in Tanzania. In 2013, the Center for Reproductive Rights published Forced Out: Mandatory Pregnancy Testing and the Expulsion of Pregnant Students in Tanzanian Schools, which documented the catastrophic nexus of “forced, early marriage”, “adolescent pregnancy”, and expulsion from school and from all its current and future benefits. Last year, Human Rights Watch published No Way Out: Child Marriage and Human Rights Abuses in Tanzania, and last month, HRW testified, “Although rates of child marriage have decreased, the number of girls marrying remains high. Four out of 10 girls are married before their 18th birthday. Some girls are as young as 7 when they are married.” More recently, the Fordham International Law Journal published, “Ending female genital mutilation & child marriage in Tanzania.”

All three studies, and many more, have relied on the work and insight of Tanzanian organizations, such as the Children’s Dignity Forum; Chama Cha Uzazi na Malezi Bora Tanzania (UMATI); and the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE) Tanzania. These organizations work with the Tanzania Women Parliamentary Group; the Tanzania Media Women’s Association; the Tanzania Gender Networking Programme; and Tanzania Youth for Change. Many of these groups, in particular the Children’s Dignity Forum, work closely with the Foundation for Women’s Health Research and Development (FORWARD), an African Diaspora women’s campaign and support organization. In 2013, FORWARD and the Children’s Dignity Forum co-authored, Voices of Child Brides and Child Mothers in Tanzania: A PEER Report on Child Marriage.

In other words, in Tanzania as elsewhere, women and girls, and some men and boys too, have been researching, mobilizing, advocating, circulating petitions, rewriting laws, organizing peer groups, and raising a ruckus for quite some time. Will this year be the year? The editors of the Daily News seem to think so, as they suggest in a recent editorial, “Yes, child marriages can be stopped.” Will child marriages be stopped as a result of the elections and the incoming president and parliament? Is the time for new approaches finally here? Will this be the year of the girl child in Tanzania? Stay tuned.

October 6, 2015

Zanele Muholi’s visual activism “Isibonelo/Evidence” at the Brooklyn Museum

Back in 2006, David Goldblatt showed me a catalogue showcasing fourteen South African artists’ work, with Zanele Muholi’s photograph of singer Martin Machapa on the cover. Machapa’s dashing young body, clothed in a patterned blouse knotted up to display taut belly skin, pivots towards the camera in a quarter turn. Goldblatt had mentored Muholi at Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, and he wanted to make sure I directed my attention to her work. By the following year, Zanele Muholi had a solo show, “Being”, at Michael Stevenson Gallery. I walked up the steep cobblestoned streets to the Waterkant district in Cape Town, where the gallery was then located. There, shimmering by the doorway, was the opening day crowd: narrow champagne flutes in hand, effervescent in the light of the setting sun behind Signal Hill.

Inside presented a different set of stories – stories that were rarely incorporated into the national narrative or South Africa’s celebration of itself as a newly democratic nation. I remember one of them well: Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg 2007. In it, two women are seated leaning into the warmth of an ancient Jewel coal stove, kissing in quiet intimacy. The scene could be set in early September; it is still cold; even though they are indoors, one of the women wears a blue woollen hat. But it isn’t so cold that they are bothered by their bare legs. We sense that spring is coming. The coal stove, an antique harkening back to their grandmothers’ era, is peeling in spots. There is nothing new to see here: this is an inherited way of loving, old-fashioned and solid as the Jewel.

Included in that first solo show were portraits that provided the foundation for her remarkable, long-term project, Faces and Phases, a portrait series created between 2007 and 2014, which “commemorates and celebrates the lives of the black queers” Muholi met in her journeys throughout South Africa. The project also collects firsthand accounts that bear witness to the schizophrenic experience of living in a nation where LGBTI people are often the targets of violence – this despite the fact that South Africa’s progressive constitution specifies that it protects the rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) people. Muholi points out that whilst South Africans may

…look to our Constitution for protection as legitimate citizens in our country […] the reality is that black lesbians are targeted with brutal oppression in the South African townships and surrounding areas. We experience rape from gangs, rape by so-called friends, neighbours and sometimes even family members. Some of the “curative rapes” inflicted on our bodies are reported to the police, but many other cases go unreported. At present South Africa has no anti-hate-crime legislation. Rampant hate crimes make us invisible. Coming out exposes us to the harshness of patriarchal compliance. We are also at risk when we challenge the norms of compulsory heterosexuality.

Already, in 2007, Muholi had embarked on a long-term project of cartography — mapping, marking, and revisiting her participants again and again. The target of Muholi’s project is to counter invisibility, marginality and systemic silence. She seeks, instead, to include LGBTI people to the forefront of South Africa’s liberation narrative. To that end, Muholi notes that her goal is to create an archive of “visual, oral and textual materials that include black lesbians and the role they have played in our communities”.

More than seven years after seeing her exhibition in Cape Town, I arrive at Brooklyn Museum to experience a retrospective of Muholi’s work, “Isibonelo/Evidence”, armed with a copy of her recently published book, Faces + Phases 2006 -14 (Steidl Publishers, 2014). The opening essays remind us of the significance of photographs in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: they are evidence of existence, of being, of present-ness. Muholi realises that not having photographic evidence of her maternal or paternal grandparents is a “deliberate” erasure, emphasising her feelings of “longing, of incompleteness, believing that if I could know their faces, a part of me would not feel so empty” (6). That knowledge of deliberate, systematic of erasure from the historical records of the nation is so acute that she is driven now to “project publically, without shame” (7). Following Muholi’s opening salvo, Sindiwe Magona’s powerful poem, “Please, Take Photographs!” exhorts parents to

Go to the nearest or cheapest electronic goods store

And there, buy cameras by the score

Hurry, Go! Go! Go!

Then go home; gather your family and

Take photographs of them all

Magona reminds us why even the ordinariness of photographing one’s beloved child is an act belied by an unspeakably painful understanding: we know that the young man or woman “will not see thirty.”

Muholi gifts her labours to her mother, Bester Muholi, “and to all mothers who gave birth to LGBTI children in Africa and beyond” and to those “who lost their children to hate crime-related violence”; she reminds them that they are “not alone” in their mourning. Her work here at Brooklyn Museum is a reminder of the fact that violence against LGBTI people continues; however, in mourning, we are not only asked to remember, but equally invited to celebrate and exhorted to continue—with pride and even arrogance, if necessary. The exhibition promises a wide-ranging collection of ongoing projects about LGBTI communities, both in South Africa and abroad; included are eighty-seven works created between 2007 and 2014—photography, video, and installations that showcase her mandate as a “visual activist”—ranging from her iconic Faces and Phases portrait series, the photographic series Weddings, and the video Being Scene, which focus on love, intimacy, and daily life within Muholi’s close-knit community.

As one walks in though the double glass doors to the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art on the 4th floor, one sees a larger than life portrait of Ayanda Magoloza, of Kwanele South, Katlehong, Johannesburg (76.5 x 50.5cm, taken in 2012). Ayanda’s hair is a crown of curls arranged above her head; she is the regal queen, welcoming visitors into this gallery. Positioned directly behind her is a black chalkboard with haikus of loss and rejection. The chalk inscriptions on the board are handwritten odes, minimalist narratives of loss and rejection, threats of sexual assault and bodily harm, and records of violent deaths carried out. One reads, “How are you getting satisfied with a finger and tongue? You need a penis.” In case you imagine that to be a playful bit of crassness, the next reads, “ONE TIME A GUY TOOK OUT HIS PRIVATE PARTS, AND SAID, ‘this is what you need’”. Then, that threat is made real: “THE COACH SAID HE DOESN’T LIKE ME AS A LESBIAN AND HE WANTS ME AS HIS WIFE SO THAT I CAN STOP BEING A LESBIAN. WHEN I SAID ‘NO’ AND TRIED TO LEAVE, HE BEAT ME WITH A STRAIGHTENED CLOTHES HANGER. THEN HE RAPED ME MANY TIMES, ALL NIGHT”. And another: “There are 28 stab wounds on her face, chest and legs. She even has cuts on the soles of her feet.” In between these stark lines, inscriptions of possibility, evidence of the ability to fight back—if we are gathered in numbers. Written in some of the smallest, most decorative writing on this board is this narrative: “They were outside the bar, a crowd of people calling them Tomboys. But she said, ‘No. We are not tomboys we are lesbians.’ And they left and we never saw them again.”

In order to reflect the strength of that legion, the most prominently displayed work in the first room of the gallery is the Faces and Phases portrait series, juxtaposed at a right angle to the backboard. There are thirty portraits here—ten in a row, and three deep; they are accompanied by a full digital archive giving us access to over 250 portraits taken around the world. Muholi explains that the title, Faces and Phases, is about a long-term relationship, not a simple snapshot—a process of growth and change during the time that the country, too, transitioned. The participants’ faces and bodies communicate two distinct messages: one set presents themselves to the world bold as lions—they communicate a monumental strength with the invitation of a come hither look. The others’ eyes focus on something else—they look within to find reasons to stand still with dignity, despite life experiences of pain, rejection. Muholi notes,

Faces express the person, and Phases signify the transition from one stage of sexuality or gender expression and experience to another. Faces is also about the face-to-face confrontation between myself as the photographer/activist and the many lesbians, women and transmen I have interacted with from different places. Photographs in this series traverse spaces from Gauteng and Cape Town to London and Toronto, and include the townships of Alexandra, Soweto, Vosloorus, Khayelitsha, Gugulethu, Katlehong and Kagiso.

Opposite the blackboard, framing the portraits on the right side, is a timeline of significant dates in South Africa’s hate crime history—listed are some of the most gruesome murders of gay and lesbian subjects of this country. On the other side of the timeline, a larger-than-life image of a woman’s hands holding an ID card. Disebo Gift Makhau’s Identity Card (I.D. No. 901123 0814 08 7) is held open in someone’s hands – someone wearing a jaunty striped sweater, the camera so focused on her fingers that we can see that her cuticles need some pushing back. We see that Disebo Gift was born 1990 – 11 – 23. The card was issued in 2006 – 07 – 23. The opposite page bears the stamp: “DECEASED”. It is a plain message. But nothing about the sweet face in the ID card picture prepares one for the finality of that stamped message. Muholi explains,

Phases articulates the collective pain we as a community experience due to the loss of friends and acquaintances through disease and hate crimes. Some of those who participated in this visual project have already passed away. We fondly remember Buhle Msibi (2006), Busi Sigasa (2007), Nosizwe Cekiso (2009) and Penny Fish (2009): may they rest in peace. The portraits also celebrate friends and acquaintances who hold different positions and play many different roles within black queer communities – an actress, soccer players, a scholar, cultural activists, dancers, filmmakers, writers, photographers, human rights and gender activists, mothers, lovers, friends, sisters, brothers, daughters and sons.

In Muholi’s returns and re-visitations, she communes with each of the participants, reminding us that there must be a deep and abiding relationship in order to build such an archival project. Without this on-going relationship, she would have only mapped surface structures or a general lay of the land. In returning to converse with each person, she gives them the space to show how they shift into new modes of expressing gender and sexuality, and define how they wish to be seen as desirable subjects. For that reason, explains Muholi, only photographs those who are over 17 years old; she specifies that her participants had to be 18 by the time her work was published. She also specifies that her participants must be out of the closet – because, as she said at a talk at Light Work in Syracuse, NY, she “does not want to be responsible for someone else’s closet” — that is, she does not want to “out” anyone, or decide for them when and how they negotiate that difficult entry. Her participants must be sober, and fully present in their participation in this project, so that they can consent to being photographed. They must not be drunk or smoking in the photograph, because she does not want to feed stereotypes of gay people — that their “lifestyle” drives them to lives of addiction, or that addiction is what drove them to practicing “unacceptable” sexualities. Her work is intended to convey an intentionality of steel—her own, and that of her participants.

The rooms beyond celebrate weddings, mourn at funerals, and take respite in the daily rituals—including lovemaking—that make us feel human, when the world tells us only of our marginalisation. The video of Ayanda Magoloza and Nhlanhla Moremi wedding from November 9, 2013 records the joyous event of a public declaration of love, fidelity, and promise between two women who thenceforth commit to walking together in life. There are billowing peachy-pink frocks on bridesmaids, shimmering pearls, starched white shirts under pressed black suits and perfectly tied bowties, false eyelashes curling like black waves, dramatic gold eye makeup, little white fans to chase a little breeze, and purely decorative, white lace parasols that do nothing to prevent the heat of the summer. A hilarious yellow and blue Volkswagon Beetle convertible rolls up, filled with revelers dancing to blaring music. The vows are as dramatic as one may expect; excited whispers are hushed with noticeable “shhhh….”s. Then, as with any celebration, there is ear-splitting ululating when the pastor declares that the couple is now wedded: “I declare you now to be married spouses.” This is not a union meant to be carried out in secrecy—it is noisy, bright, and out in the full glare of the sun, and the revelers carry on celebrating well into the night.

In the same exhibition space as the video celebrating the heat, colour, and sounds of a public union is “Koze Kubenini XX” (Until When XX) 2014: a Perspex casket topped with a funereal wreath, the colours on the flowers as brilliantly jarring as those in the wedding video opposite. On the walls next to the casket, posters meant to mirror posters of newspaper headlines that are pasted daily onto lampposts in South Africa, blaring the most sensational news in order to drum up sales. They read, “ANOTHER LESBIAN’ RAPE AND MURDER” and “QUEER–CIDE: 22 YEAR OLD LESBIAN GUNNED DOWN IN HER HOME. NYANGA TOWNSHIP”. Upon closer inspection, we see that Muholi’s posters are intricately beaded artworks—the yellow or white backgrounds, and the black letters forming the headlines are created by beads glued onto wood panels. By recalling the decorative beadwork for which South African women are famous, each poster now memorialises and individualises the women’s lives, rather than reducing them to a titillating headline on cheap paper that will tatter down drains by the next rainstorm.

On the day of the opening, Muholi performed a funeral, laying her body down in the Perspex casket whilst a crouching mother mourned next to the coffin. Many such mothers are mourning the loss of their children, killed solely because of the need of patriarchy and heterosexuality to violently police and punish bodies that run other to their dictates; the mother who mourned here on opening night represents but one of the many to whom Muholi has spoken in South Africa. Now, long past opening day, Muholi’s own black and white portrait from Faces and Phases is laid to rest in the white folds of a pillow inside the casket. In the portrait, Muholi is dressed in leopard print, her signature black hat, and black-rimmed spectacles. Because she has set herself against a leopard print backdrop, she settles in easily with her surroundings—a chameleon who belongs, but who nonetheless stands out. Above her, resting on the clear Perspex of the coffin, that violent wreath of flowers: the pink orchids on the wreath advertise their sex organs: the labellum, intended to invite pollinators in, are twin vulvular cushions, unashamed of their presence.

In between these celebrations and memorials to those whose lives have been forcibly taken, there is a reminder of ordinary love: Being Scene, a video of a lovemaking couple in soft focus, identities blurred (it is Muholi and her partner). We cannot identify who the figures are, nor is it pornographically focused. But we can see that the lovemaking is vigorous, penetrative, one partner atop the other. It counters claims of those who continue to imagine that in order for a woman to feel good sexually, a penis needs to be in the picture. The ordinariness of love, and lovemaking underscores Muholi’s project; she stresses the need to create a visible visual archive of a range of experiences: arrogance and sweetness, fight and contemplation.

Zanele Muholi and Visual Activism: “Isibonelo/Evidence” is at Brooklyn Museum from May 1–November 1, 2015.

October 5, 2015

Memory, between nostalgia and archive: A review of Clement Siatous’ ‘Sagren’ exhibition

Following the collective of Mauritian and international artists who exhibited in the country’s first national pavilion in Venice in 2015, a new survey of work by Clement Siatous at the Simon Preston Gallery reiterates the relevance of the small island nation in the flows and exchanges between global superpowers – in this case, Britain and the United States. Though Siatous holds Mauritian residency, he was born in the Chagos Islands, and now represents a group of refugees from the Chagos Archipelago—sixty islands in the Indian Ocean between Africa, India, and Malaysia—who were forcibly displaced in the 60s by the British military, eventually making way for a United States naval base during the Cold War.

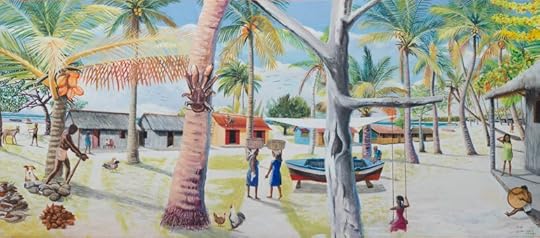

Representing the last twenty-five years of Siatous’ work, the paintings at Simon Preston Gallery are of Chagos are re-created from memory and serve to reconstruct an archive of Chagossian life before the indigenous population was forcibly deported between 1965 and 1971. Scattered between the Seychelles, Mauritius, and the U.K., the Chagossians have spent the subsequent decades petitioning the U.N. and the British government for the right to return. Curator Paula Naughton’s New Atlantis Project recounts how the House of Lords and the Queen herself ruled against the Chagossians’ return, citing the islands’ lack of population before the 18th century as grounds for nullifying the Chagossians’ claim as an indigenous population. With the Chagossians’ former world inaccessible and overgrown with generations of palm trees, the New Atlantis Project sought remnants of Chagossian history. From colonial correspondence, to furtive U.K.-U.S. communications, to metallic work implements in a distant military museum collection, there is a disturbing dispersal of Chagos’ history that echoes the diasporic journeys of its people. Herein lies the great value of Siatous’ contribution—with few written records and photographs, with their possessions and tools of life left behind on the islands during the mass deportation period, Siatous employs paint as memory and his oeuvre as archive.

The exhibition primarily consists of outdoor scenes filled with figures who greet the tasks of the day: crushing coconut meat for oil, preparing fresh seafood, digging for roots, or bundling the cargo for a ship. Despite the attention to individual figures or their dress and routines, the paintings do not represent particular historical moments in the same indexical fashion of a photograph or postcard. Subject to the fallibility of human memory, Siatous paints scenes in sequence, capturing the realities of daily life and colonial presences through the entirety of his series. Some are recreated memories to which he has direct access: in Diego, figures engaged in labors typical to his father’s generation, or the instruments used in the sega dance. Others, like the image of the ship Nordvar carrying away the remnants of the population (Dernier Voyage des Chagossiens a bord du Nordvar anrade Diego Garcia, en 1973) was not an event witnessed by Siatous, but the embodiment of a communal memory.

Clement Siatous.

“Diego”. 2015. Acrylic on linen.

Siatous’ technique of juxtaposing island paradise with portents of sorrow creates a productive tension, especially once viewers realize that the deceivingly idyllic life is complicated by the presence of British colonial officers, military vessels, or a rusting shipwreck. An uncritical viewer might read the paintings as personal musings by a naïve autodidact, but for Siatous, his personal memories commingle with the oral history shared among the Chagossian community to enact distinctly political ends.

Here, history is a tenuous blend of fact and memory—an uncomfortable balance not dissimilar to the canonized ‘histories’ of colonized populations. The difference is Siatous’ transparency. Though he paints with conviction, employing each image as a resolute statement about the existence and validity of Chagossian history, he acknowledges that no single scene has the authority to define an entire narrative. He works with larger scale painting because the borders of his own memory, and his responsibility to record it, expand beyond vignettes. Even with the generous canvas size, the majority of images crop the edge of a building or a passing boat or a dynamic figure, generating the sensation that another bustling scene is just outside the viewer’s purview. The ability to author Chagossian history is left open to other voices, his fellow refugees, whose careful guarding of traditional culture or relentless political action also shape this people’s evolving narrative.

After being denied re-entry in 1962, Siatous did not set eye on the islands’ coastlines again until 2012 when he was able to witness the erasure of his people’s presence. The now overgrown island that was once his birthplace and home, Perhos Banhos, is the poignant subject of I’sle Perhos Banhos abandonnees en 1973.

Clement Siatous.

“I’sle Perhos Banhos abandonnees en 1973”. 2006. Acrylic on linen.

This is the sole image in the exhibition lacking human figures. Split horizontally at the midpoint with a band of text identifying the setting, the two registers depict the island from close-up and long-range vantage points. In the upper register, the dense vegetation is paused in a cycle of death and regeneration as older palms collapse while the strong saplings burst through the canopy. The contemporary state of the island embodies the British reasoning for denying the Chagossians indigenous status, with its uninhabited nature echoing the primal condition from centuries ago. Siatous, however, unabashedly contrasts the untamed island with the dilapidated remnants of a dock, an indelible mark of human presence and unjust deportation. In painting the remnants of Chagossian life at Perhos Banhos, Siatous reasserts his voice against the dominating British narrative that dictates a totalizing absence of life, activity, and civilization prior to their arrival, and offers the viewer a more complex interpretation of history through personal and collective memory.

Exhibition view, Simon Preston Gallery, New York.

Oakland’s Matatu Festival: Interrogating for the place and time of an Afro Future

It is an exciting moment for Afrofuturism: the otherworldly Janelle Monáe is lauded as a music and style icon; antiracist activists turn to the oeuvre of Octavia Butler for inspiration; and science fiction from the African continent enjoys international circulation. And at a deeply distressing conjuncture when Black life is so visibly and aggressively under siege, thinking about the future is no less than a matter of survival for Black folk across the diaspora. Many writers and theorists of Black and POC speculative fiction have suggested that racism, abduction, enslavement, experimentation, colonization, and imperialism are all actually the metaphorized stuff of the sci-fi genre. Yet too often, hegemonic visions of the future—whether utopian or dystopian, 20-minutes into the future satires or sweeping space operas—leave little room for difference.

The third-annual Matatu Festival of Stories in Oakland, CA, while not explicitly a festival of Afrofuturism, explored the relationship between Blackness and futurity across artistic genres during its run from September 23rd to 26th. What are the technological circuits of the African diaspora? How can we think of this diaspora as not just a geographical relationship predicated on traumatic dispersal, but also as a temporal relationship—one that weaves together past and present with hopes and dreams of possible futures? And given this history of Black dispersal and displacement, what might a liberatory mobility look like?

While matters of the imagination, these questions are of critical importance to Black people in Oakland. After decades of racialized disinvestment, the city has come to be hailed as a site of economic, cultural, and technological innovation. Its boosters celebrate this transformation in terms of the now-familiar language of urban “renaissance”—a trope that has signaled, since the time of its referent, the European Renaissance, a techno-utopian vision of the future as salvation. But long-time residents are rightfully suspicious of the way that such narratives treat the time before the after as a “dark age,” serving as a form of cultural whiteout that is the symbolic counterpart of physical displacement. Indeed, since 1990, while it has come to be celebrated as the in the country, Oakland has lost over 54,000 (one third) of its Black residents.

The visionaries behind Matatu, however, refuse to cede the narrative of renaissance to those who would write Black people and cultures out of the next chapter in the evolution of this embattled city. If Oakland is to have a dynamic future, they seem to argue, it will be because it is still home to the disenfranchised communities of color that have long created “disruptive” innovations in consciousness, making it a “global city” with or without new tech companies like Uber.

On opening night, performance artist Saul Williams took whitewashed techno-utopianism to task with a rousing performance of spoken word poetry from his new collection US(a.) and songs from his concept album MartyrLoserKing. His a cappella chant of the thumping anthem Burundi (“I’m a hacker in your hard drive; I’m a virus in your system”) took on special significance in the Bay Area, where the language of hacking is regularly invoked by millionaire wunderkinder to circumvent the messy baggage of structural oppression with quick-and-easy techno-fixes. Instead, Williams went on to compare the Middle Passage to the Internet and encouraged the audience to “hack” into the powerful networks that classify, incarcerate, and exploit black bodies and minds in the twenty-first century.

Williams appeared alongside local experimental music duo Black Spirituals, a meeting of electronic sound artist Zachary Watkins and percussionist Marshall Trammell that defies categorization. Merging the improvisational solos typical of jazz with dense layers of electronic frequencies and hard-edged noise, the band unleashed generative soundscapes that emerged from and, just as suddenly, descended back into raucous cacophony. But as with any cutting edge, theirs was a form of “disruption” built on tremendous respect for earlier languages of sound. Later in the week, Trammell appeared again, this time with master percussionists Donald Robinson, Tacuma King, and Spirit in the first iteration of a project called “DEMOCRATICS: Decolonizing the Imagination.” Holding an improvisational dialogue between his rock-n-roll kit and the djembes, symbols, and singing bowls of his collaborators, Trammell communed with elder musicians in a lab of linguistic experimentation through the diasporic technology of the drum.

Williams and Black Spirituals followed Necktie Youth, a new film by 23-year-old South African director Sibs Shongwe-La Mer. Necktie merges a stark, almost documentarian take on upper-middle class suburban ennui with a broader, national story of youth disaffection in post-apartheid, post-Mandela, and post-“rainbow” South Africa. It follows a multiracial group of affluent early-twenty-somethings as they drift between drug-, booze-, and sex-fueled parties in the wake of the live-streamed suicide of their friend Emily. The ubiquity of technologically-mediated encounters marks betrayed promises of transcendence in the face of the stubborn recalcitrance of old and new social divisions based on race, class, geography, and mobility. While the film is firmly rooted in the geographies of contemporary Johannesburg, rendered strikingly in high-contrast black-and-white photography, it also speaks to the broader contradictions of our moment: the naive hopes we place upon the shoulders of our hyper-connected millennials, and our creeping suspicions that we’ve missed our window for revolution.

Still from Necktie Youth

There were clear resonances between Necktie and the festival’s final offering, Black President, the debut film by South African musician-turned-director Mpumelelo Mcata. President profiles the visual and performance art of Zimbabwean-born artist Kudzanai Chiurai, who has courted controversy by relentlessly questioning what is “post” about the “post-colonial” political regimes in Southern Africa. Chiurai’s piercing insights and images—which, for all of their hyperbole, are no less close to life—remind us that undemocratic narratives of salvation and renewal can be authored by Black and White elites alike. And the potential for writing the poor and political dissidents into the margins in the name of a future-oriented “renaissance” is just as high.

Still from ‘Black President’

October 2, 2015

Weekend Music Break No.85 – The Dance Edition!

The weekend is here so let’s take a break to enjoy some music… and dance! This week’s edition is a collection of dance videos, official clips, fan made and otherwise. Enjoy a glimpse at the myriad of moves hitting dance-floors and streets across the world!

We start off in the UK with a impressively growing Afro-House dance scene, dancers (and musicians) such as Reis Fernando and Milo & Fabio incorporate influences as wide as Hip Hop, Kuduro, and House; Then, we move to Trinidad where the Afropop take over continues unabated, making for some great Africa-influenced Soca moves; Yemi Alade releases a new video focused on dance, so we thought we’d include her and her dancer’s Coupe Decale influenced moves here; Colombia does dancehall to great effect, and with this video by Leka El Poeta, we get a little “Choke” as well for those who are keeping track; Not relegated to history with Harlem’s Jazz age, the Cha Cha makes it back to NY, and this rotating cast of Yak Films dancers do their best to update it to 2015; We are winning anytime Just A Band release a new video, and this dance-focused video definitely is one of their best yet; Former AIAC contributor Wills Glasspiegel co-directed this video (along side DJ RP Boo) focused on Chicago’s Footworking phenomenon, shot at the South Side’s Bud Billiken parade; which reminded me that Flying Lotus had drawn some specific connections between Jazz and Footwork earlier this year with his video for Never Catch Me featuring Kendrick Lamar; And, last but not least, Pantsula dancers also get the Jazz treatment in another former AIAC contributor (Allison Swank) produced video for the UK’s Sons of Kemet.

Digital Archive No. 20 – The Haiti Memory Project and the digitization of oral histories

Thus far in this series, I haven’t really featured any digital oral history projects, which is a shame since there are so many great collections available. For historians and anthropologists alike, spoken testimonies represent a central source for understanding African Diasporan pasts and presents. While the written word provides information and context, the spoken word also provides information in addition to the personal connections that bring scholarship to life. Digital oral history collections provide unprecedented access to these testimonies, serving as key repositories for use in both pedagogy and scholarship. The testimonies to be found in collections like these open up a realm of possibilities for bringing first-hand experiences and memories to any computer or mobile device around the world.

This week’s featured digital oral history collection is the Haiti Memory Project. This project is a selection of 25 interviews (from a much larger collection available here) focused on the 2010 earthquake in Haiti and life on the island following the devastation. These interviews were collected by Claire Antone Payton, a PhD student in History at Duke University, in Port-au-Prince in summer/fall 2010. Payton partnered with Doug Boyd of the Louie B. Nunn Center at the University of Kentucky to make these oral histories available to the public. The Nunn Center is “a leader and innovator in the collection and preservation of oral histories.” In addition to providing access to over 9,000 oral histories via their website, the Nunn Center has also developed a web-based Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS) to enhance access to oral histories online, combining time-correlated transcripts with search capability and indexing. OHMS is available for download here. Though OHMS has yet to be applied to all of the interviews featured on this site, you can access these interviews and others like them in the Nunn Center catalog.

Photo by Blue Skyz Studio on Flickr

The featured interviews range in length from 20 minutes to nearly two hours and were mostly conducted in Creole. There are some interviews in English, like this one by Claude Adolphe or parts of this one with Marc Antoine Noel, but the majority of the content is in Kreyol or French. The majority of the interviews are presented in their full format, without translation. But there are also a select number of them which include transcriptions of the original interview and their translation into English. You can read translations of interviews with Fluery Pleusimond on the earthquake, Francoise Erylne‘s story of survival, an account of the earthquake from Chrispain Mondesir, and another anonymous account of the earthquake. There is also a helpful collection of links to other digital resources on Haiti.

You can follow the Haiti Memory Project on Twitter: @HaitiMemory. Explore more collections from the Nunn Center here (including this project focusing on African Immigrants in Kentucky). You can also follow the Nunn Center on Twitter and Facebook. As always, feel free to send me suggestions via Twitter (or use the hashtag #DigitalArchive) of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

October 1, 2015

Liner Notes No.11: Musicians engage Morocco’s ‘African’ identity through Gnawa

The typical jazz festival in Morocco is characterized by a celebration of the Andalusian legacy of Morocco’s musical heritage, focusing on the sounds of Iberia’s Arab and Islamic past. But there is another type of music important to Morocco’s cultural heritage that is often overlooked at the country’s flagship music festivals. Gnawa music is the spiritual songs and rhythms to emerge from Morocco’s formerly enslaved and whose origins are in West and Central Africa. The only cultural institution to focus on showcasing this culture is the annual Gnawa and World Music Festival in Essaouira, a former trans-Saharan slave entrepôt on Morocco’s southern Atlantic coast.

The peripheral presence of Gnawa in Morocco’s premiere music festivals—Jazzablanca, Jazz au Chellah, and Tanjazz—is emblematic of what Hisham Aidi observes as “a much larger conversation about identity in Morocco, and which direction the country should face—east, west, or south.” It is a debate rooted in a historically uneasy relationship between the Gnawa people and the state. In the colonial era, French officials played upon Gnawa’s Sufism and mystic rituals to counter Islamic reform movements, and keep Morocco at a distance from the greater Middle East. During the post-independence period, the country’s political and cultural elite preferred Andalusian music as the national tradition, considering Gnawa and its rituals to be a possible source of embarrassment to the rest of the Arab and Islamic world.

However, in the past 20 years Gnawa music has made small inroads into the elite cultural spaces of Morocco. At this past month’s Jazz au Chellah Festival in Rabat, Gnawi acts such as Mustapha Baqbou, Gnaous De Marrakec, and Gabacho Maroconnection featured on the bill. The entrance of Gnawa into such spaces reflects a change in gaze from festival curators, who are now beginning to look south at the country’s West African roots. The gesture is a small, but significant step for a community that has had to continually negotiate their social and cultural legitimacy in Morocco.

Gabacho Maroconnection is a Gnawa band based in Europe, who opened this year’s Jazz au Chellah. Hamid, the band’s leader, has an almost activist vision for the role of Gnawa in the greater Moroccan society. He says, “Moroccans often forget that Morocco is in Africa… Gnawa is a bridge south across the Sahara for Moroccans to rediscover their African roots.” Hamid and other Gnawa musicians celebrate the advances Gnawa has made in the Moroccan cultural realm in recent years, but insist there is still progress to be made in order to place Gnawa next to Morocco’s more recognized music traditions. “We need more help from the people at the responsible institutions. The festivals are good, but we need help in other areas to push the cultural politics forward,” he claims.

This feeling of marginalization may in fact be the thing that brings Gnawa back to the core of Moroccan identity. It is a sentiment that resonates with many Moroccan youth, especially those living in Europe and the United States, and who have encountered their own struggles with integration. Motifs such as displacement, hardship, and suffering that are intrinsic to Gnawa music are themes that many in the diaspora relate to and use to help construct for themselves an identity and place in society. As Hamid explained, “Even if young North Africans in Europe like hip hop, they feel Gnawa. It’s biological. It’s in their roots. They may not become crazy for Gnawa, but they see it as a part of them.”

Hamid knows, because he is the perfect case study. Originally from Essaouira, Hamid’s engagement with Gnawa abroad has called him back to his roots. And even with the success he has enjoyed touring Europe, he now thinks about returning to Morocco to live permanently. It may just be that while cultural institutions within Morocco take baby steps towards embracing Gnawa, it will be Moroccans overseas, and bands like Gabacho Maroconnection that will give Gnawa music and culture an extra push towards the center of Morocco’s cultural identity.

September 30, 2015

A reflection from being on the inside of the South African badvertising industry

One of the things you must accept when you work in the advertising industry is that it is made up of people who don’t care much about anything (except retaining clients). You, the reader, the listener, the audience are the least of advertising’s concerns. Ironically, you are also its raison d’ etre. This schizophrenia is built into the mechanisms that make the advertising agency and the client relationship work. It is this common contempt for what marketing calls the ‘consumer,’ namely, you, that keeps agency and clients happy. If advertising agencies are generally condescending to the public, in most instances it is at the request of clients whom, I later learned, care even less. This is always true – and it’s even more true when the imagined consumer is black.

I worked for five years in advertising in South Africa. My first job was as an unpaid intern at LOWEBULL (before it became LOWE & PARTNERS) in Cape Town. Kirk Gainsford was at the helm of the agency as Executive Creative Director and Alistair Morgan was his deputy, the Head of Copy and Creative Director. Alistair was a man of words. His debut novel Sleeper’s Wake had just been released to critical acclaim, and I had read his short story “Icebergs” in a Caine Prize anthology. To work with a novelist in advertising is a novelty and during my five months of unpaid labour I was frequently in Alistair’s office to pick his brain about matters related to advertising and literature. He was sensitive to prose and textual aesthetics; he was not merely an adman, he was a cultural producer and it showed. He was, after all, the Creative Director on Hansa’s “Vuyo the Business Mogul” TV commercial, the cultural significance of which is best exemplified by the fact that years later a brand named Vuyo’s was launched by Miles Kubheka in Johannesburg. It followed the exact narrative of the advert, with Miles starting off as a vendor selling his Boerie rolls in a mobile van, and culminating with him opening up the first Vuyo’s restaurant in Braamfontein. Alistair Morgan, Kirk Gainsford – two white men nearing middle age – had tapped into popular sentiment (or had they been part of the engine that was creating it?). In any case, I was impressed. What had begun merely as a commercial to sell beer had exceeded its brief.

I moved from LOWEBULL and went to JWT to work with Conn Bertish who was and is an activist, artist and surfer. He didn’t possess the literary qualities of Alistair, but he had the unpredictability of a visual artist and he pushed for work that pressed against boundaries – especially those set by clients. We were working on a new J&B campaign, with him being adamant that there was a way of selling the brand without appealing to the lowest common “I have arrived” denominator, which was endemic in advertising, at the time. When he left to join Quirk advertising, I stayed behind to finish the campaign. I had been thinking about Vuyo a lot and the how in that single advert black aspirations were bottled into the single, simplistic, superhuman rags to riches narrative of ‘magical blacks’. I worried that the ad threatened to engulf every sphere of black social life – everyone was a Vuyo in the making, pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps and sneering at those who seemed trapped in the doldrums of poverty. Vuyo had made his way into my work as well. The challenging new J&B advert I had started writing with Conn, which would introduce a new way of viewing what it is we’re talking about when we talk about ‘being made’ was, by the end, just another rags to riches rag. I will admit that when it came out I was depressed, but the show had to go on. This singular narrative, this social engineering project, which we churned out with unfettered abandon, slowly unspooled, at least for me, what the post-South African state would be hinged on. It made it clear that the entire premise of our democracy, like all democracies I suppose, was self-interest. And as we all know, self-interest is always at the expense of someone else. Unfortunately, in South Africa, we know very well whom that ‘someone else’ is right down to his most minute demographic detail, and instead of speaking of ways to dismantle the oppressive structural organisation of power and privilege that would set him free to enjoy his country’s democracy, we insist that he becomes a Vuyo and pulls himself out of his bad situation without his country and state doing the work of undoing the terms that produce and reproduce his particular situation, namely, without dismantling the socio-economic structure that maintains white privilege. If we were honest with ourselves, we would surely accept Vuyo as a lie meant to bamboozle instead of empower South African blacks.

A month or two after Conn’s departure I received a call from Ogilvy & Mather Cape Town. This was after my own advert had been aired. I was still anxious about Vuyo’s granny’s exaggerated “Big! Big! Dreamer!”

“Hi, Lwandile. It’s Chris.” Chris Gotz, the Chief Creative Officer of Ogilvy South Africa.

It was 2013 and Ogilvy & Mather Cape Town was the number one ad agency in all of Africa. A call from Chris Gotz meant that you left whatever it is you were doing and took his meeting. A few weeks later I was in his creative studio. And a few months later, I left the ad industry all together.

By the time I arrived at Ogilvy & Mather, I had become less interested in selling brands and more invested in the politics of representation in commercial images. I wanted to think about the extent to which advertising is a reflection of the society, or of particular articulations of society’s anxieties, and when it became a vehicle that socially engineered people’s aspirations and tastes. I wanted to think about how much of it was selling brands, and how much was it was the manufacturing of images that ill-served the people for whom they were intended? I’d sit on Chris Gotz’s couch in his office and we’d talk about books, politics, art and literature. He was an English major in varsity, but took up History in his post-graduate studies. He went to school with Eric Miyeni and Victor Dlamini, he told me one day. I don’t recall the conversation much, but it was something about upward social mobility and bourgeois blacks. I had become in some small or big way complicit in the way in which white corporate spaces were talking about blacks, rich or poor, partly because of how I emphasised my proximity to them (by virtue of pain and position in the post-apartheid socio-politico-economic drama) and partly because of how I tried to distance myself from them (by occupying nearly every conceivable elitist white space and consuming only the best of elitist culture). Owing to his wit, I’d always regarded Chris Gotz – privately – as the Noel Coward of South African advertising, without the characteristic hyperbole. I had never really regarded myself as anything in advertising, really, other than someone whom the industry created not out of want or desire but rather, out of the necessity to keep BEE scores on par with policy requirements.

Chris was happy when I resigned, I think. He saw that my heart was not in it anymore. Gradually, we’d stopped talking about the work and we talked about transformation and racism. Secondly, he knew that it was impossible to be a solitary voice of critique in an incestuous industry, which is unable to look itself in the mirror. Black creatives are in the industry, but they are in the minority and their voices are highly attenuated. At Ogilvy & Mather I was paired with a brilliant art director and illustrator from P.E. named Pola Maneli. He would leave 2 months after my early retirement from the advertising industry to become a freelance illustrator, just as I would become a freelance writer. I feel now as though we both got sick at the same time by the same disease in the same place. We had been working to pay the rent, and then Ogilvy & Mather Cape Town produced that “Feed a child” TV commercial and I lost any illusions I had about my industry. The infamous Black Twitter has become incensed. It was enough that whites were arrogant and racist, they went as far as creating an advert that depicted a black child as a dog, thus rubbing the salt into the open wound, which has refused to heal with time for time hasn’t changed their socio-economic circumstance and their servitude to white masters. Now, in his office we talked about the internet backlash. He was genuinely surprised by it. He had workshopped the idea with some black Joburg creatives and they had found nothing untoward in the advert. Then I had wished he had consulted Pola and I, but it was too late. The damage was done. And it was for the best that things happened the way they did. At last I would be free of the position of explaining black pain to white indifference.

Although I had worked with inspiring minds in advertising, they were still white minds that thought through white bodies. Being white doesn’t automatically make one automatically racist, but white culture in South Africa is defined and sustained by racism: spatial racism, cultural racism, linguistic racism, economic racism, and every other form of racism imaginable. Chris asked me back then to write something about the advert and I had reluctantly agreed. But I knew I wasn’t going to do it. I thought this was the opportunity for the South African ad industry to ask itself some serious questions and to look at the way in which it curates and produces images and how its character narratives offend those it hopes to attract to the brand or brands and companies it represents.

My hope for common sense to prevail was misplaced in any case, for the advertising industry continued as though a poor black child had not been recently produced as a dog in our televisions; as though “Eugene” that Nedbank advert with that exasperated white narrator isn’t mocking and condescending toward our erstwhile protagonist who can’t seem, for the life of him, to make the “smart” choice with his money; had it been his own conscience speaking back to him the story would’ve been different, but then it would not be as entertaining to the white world had it not pandered to the god complex of white supremacy and its messianic tendency to manufacture the native as an unthinking subject who needs to be rescued from self-destruction.

To see the attitude towards the white and black consumer from a creative perspective within the advertising industry, one only needs to look at KFC adverts. A special consideration is made when the advert has white characters in it, while all sensitivity is discarded if the same advert has black characters instead. Black lives are not allowed to have nuance. Instead, we are laughing, singing caricatures of real human beings, our diverse aspirations contained in the swill of rags to riches. We are all kind and obsequious and forever willing to lend a helping hand. Are we not cynical and unkind and indifferent to the world around us. Why is it that nearly all black characters in adverts appear more deliberate than necessary, as though they had a grotesque deformity and therefore had to be treated with the most pitying gaze by the camera?

I have often questioned the validity and legitimacy of this communication industry, in particular, whose primary producers of information (the ad agencies and creative departments) could not be more different (read: white and privileged) and more removed from the realities and existential anxieties of those for whom their messages are intended. This distance is one of the reasons South African advertising industry produces offensive work, at best. Thankfully for the ad industry, clients are equally removed (read: white, male and privileged) from South African reality and they consent to the work. Here I need to note there is also the other phenomenon, the black representatives from the client side, who are too ashamed of their own blackness and its discomforting narrative and want the agency to produce work that plays to the white gaze, even when they are presented work that potentially restores black dignity in the way in which black South Africans are depicted and scripted in adverts. I met a few in my five years as a creative in the ad industry. There are also many black creatives without a hint of self-awareness who do not understand the first thing about the content and social impact of their work, to themselves, first, and to others. I’ve found this to be prevalent among black creatives who enjoy being tokens in the world of advertising. And there are many. You might see them on billboards of their own work; many aspire only to grow out of the advertising industry, to write books of rags-to-riches-esque themes as an extension of their advertising work. And some have done so. During the weeks leading to my departure from the industry, I tried to imagine South African advertising having the kind of creative revolution that happened in Latin America. There, in the mid-to-late 2000s, the work took on a very distinct cultural slant, as did the work out South East Asia. Both then tended to win big at international advertising award ceremonies like at Cannes.

But this is South Africa, a country that works best in denial. It would probably require someone to spend 27 years in prison before the players in the ad industry would be spurred to do a proper analysis of the missteps and implement remedial action to transform the industry. Actually, that would not be enough. Knowing the industry as I do, they would probably make room just for him, market his remarkable story of perseverance and overcoming the odds, and then award each other prizes for their contributions to transformation.

So instead, here is one my favourite South African adverts of all time. It was banned soon after it appeared on television, of course. I think the advert below, more than Vuyo, articulates popular sentiment (and as a propaganda piece it works brilliantly for it appeals to a shared sense of empowerment rather than democratic individualism), and begins to hint at something felt deep down by most black people since our moment of democracy in 1994. It is a moment of reversal, of the slave becoming master, of what liberation looks like in the mind of the previously oppressed subject in a post-colony. This it does, without sneering at the present material condition of most black people. It merely complicates the aspiration and the present lived experience in equal measure. The advert was written by the brilliant Festus Masekwaneng, co-founder and Executive Creative Director of Mother Russia (now, Mojo Mother Russia) ad agency in Joburg. And it is the advert that lured me into advertising, in the first place. I only wish there were more like it. Then, just maybe, I would still be working in advertising.

George Houser, US ally of Southern African liberation struggles, is no more

The American activist, George Mills Houser, who passed away this month at 99 years of age, while not widely known, was central to civil rights and racial justice struggles in the United States, and especially to liberation movements against colonialism and Apartheid in Southern Africa.

In the hours immediately after his passing, members of the community who fought apartheid and colonialism began sharing the news. The first prominent obituary, though, was by the New York Times. A few days later, the Washington Post published an obituary. These articles, predictably, offered great praise—and justifiably so—but equally predictable was the slant: leading with Houser’s impressive civil rights activity with CORE in the 1940s and spending almost no time on what he spent most of his life doing. The New York Times, for example, committed two paragraphs to Houser’s Africa activism, when Houser spent the last fifty years of his life fighting on behalf of African liberation and though he saw these efforts as inextricably linked to struggles close to home.

Houser helped found both the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the American Committee on Africa (ACOA), two interracial organizations that ultimately advocated for the same ideals: black humanity and equality.

For fifty years, Houser moved the proverbial ball forward while choosing to stay in the background. He did not need to grab the microphone to speak but, rather, was an ally of African Americans activists, like Bayard Rustin and James Farmer, and Africans, including a who’s who of revolutionaries like Patrice Lumumba, Amilcar Cabral, Oliver Tambo, and Kenneth Kaunda.

Houser’s parents were Methodist missionaries so George, born in 1916, lived part of his childhood in the Philippines. His parents instilled in him a belief in the social gospel and a sense of internationalism. Following in his parents’ footsteps, he enrolled at the Union Theological Seminary in New York City. While there, Houser joined the international Christian pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and took his first public step to protest war in 1940. Along with other seminarians, he refused to register for the military and served a year in federal prison. After his release, Houser transferred to the Chicago Theological Seminary.

While in Chicago during World War II, Houser helped found CORE, an interracial organization committed to nonviolence, along with James Farmer, Bayard Rustin, Bernice Fisher, and a few others—most of whom became leading civil rights activists in the 1950s and 60s. Houser became CORE’s first executive secretary. In 1947, CORE and FOR planned the Journey of Reconciliation to test the previous year’s Supreme Court ruling in Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia that banned racial segregation in interstate travel. Houser and fifteen other black and white men took buses across the South to see whether the Supreme Court ruling would be upheld. Predictably, this group found that, in numerous cities, their actions caused them to be harassed, beaten up, or thrown in jail. Rustin spent three weeks on a North Carolina chain gang for his part. If the Journey of Reconciliation sounds like the 1961 Freedom Rides, it is because the latter was a carbon copy.

However, while he remained committed to the US civil rights movement, in the 1950s Houser helped start the American Committee on Africa and devoted his considerable organizing energies to black freedom struggles in Africa for the next fifty years. As he recalled a decade ago, “We always conceived our work as part and parcel of the civil rights struggle… The struggle in Africa was to us, as Americans, an extension of the battle on the home front.”

These struggles required different tactics. In his decades of work in solidarity with African independence, he did not shy away from supporting those who advocated violence. ACOA actively worked with all sorts of organizations across the continent that believed non-violence alone would not achieve radical change, in this case, the end of European imperialism. Rather, only by taking up the gun, as it were, would imperialists withdraw to their homes in the United Kingdom, France, and Portugal. When the ANC turned to armed struggle, ACOA continued to actively support the ANC.

US citizen involvement in African struggles began long before that. The Cold War influenced US citizens’ efforts to assist African peoples’ in gaining independence from European colonizers. Paul Robeson and other African Americans known to be sympathetic to communism led the fight in the 1940s with their (CAA). However, the crusade of domestic anti-communists—led by J. Edgar Hoover and Joseph McCarthy—resulted in the demise of the CAA. (But not before preventing South Africa from annexing Southwest Africa, now Namibia, in the newly born United Nations.)

In 1952, South African activists, led by youthful firebrands in the African National Congress (ANC) like Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and Albertina and Walter Sisulu unleashed a Defiance Campaign to overturn apartheid, a series of racist laws and restrictions recently enacted (think Jim Crow on steroids).

The same year Houser, Rustin, and others in the United States founded Americans for South African Resistance (AFSAR) on behalf of this struggle half a world away. In solidarity with the Defiance Campaign and the mighty support of Harlem’s most well known minister, Adam Clayton Powell of the Abysinnian Baptist Church, they organized a motorcade of dozens of cars that picketed the South African consulate. This 1952 action might have been the first anti-apartheid protest in the United States.

AFSAR gave birth to ACOA, an interracial organization committed to African liberation struggles across the continent. Houser’s first visits to countries in West and South Africa followed shortly thereafter; he had the chance to meet Chief Albert Luthuli, leader of the ANC, before Luthuli won the Nobel Peace Prize and was banned by his own government. Subsequently, Houser was forbidden to enter South Africa until the 1990s. No matter, he took dozens of other trips to the continent to support freedom fighters, often deep in the bush of countries like Angola and Mozambique.

As Executive Director of both AFSAR and ACOA, he helped lead the single-most important US organization advocating for the independence of African nations. Acting in support of African activists on the ground, ACOA lobbied US presidents and the State Department on countless matters: Algeria’s nasty war against long-time French occupation, the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya (brutally suppressed), Ghana’s emergence in 1957 as a beacon of hope for Africans across the continent, among others.

ACOA also provided funding and organizational resources for liberation struggle activists from dozens of African nations. Houser and the ACOA offered mighty support for those who wished to lobby the United Nations in New York City and connect with sympathetic allies across the United States.

As one of the first great Pan-African presidents, Julius Nyerere, wrote in the foreword to Houser’s autobiography, No One Can Stop the Rain: Glimpses of Africa’s Liberation Struggle:

It was George Houser who introduced me to people who supported the African anti-colonial struggle. All of us who came to the United Nations or the United States during our campaigning for independence received help and encouragement from the ACOA.

Essentially, any and every African freedom fighter who came through the United States—from Eduardo Mondlane of Mozambique to Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana—met with Houser and received help from the ACOA. Sure enough, one by one, imperialism fell and new nations born.

The last of the great African freedom struggles was the forty-year, global fight to overcome apartheid in South Africa. ACOA was an early and important supporter of disengaging, later known as divestment, from South Africa and played a major role in promoting cultural, economic, and sports boycotts—for instance, supporting long-time South African exile, the colored poet and activist, Dennis Brutus. ACOA also was deeply involved the sanctions movement as it grew across the US and in Congress, ultimately overcoming Ronald Reagan’s veto in 1986.

Honoring his role in the struggle, South Africa presented Houser with the Oliver R. Tambo Order of the Companion Award, the highest honor the nation bestows upon foreigners, in 2010. This prize seemed particularly apt as Houser had been a personal friend of Tambo since 1960, when he went into exile to lead the ANC for the next thirty years.

Although Houser, clearly, lived an incredible life, he consistently remained below the radar and behind the scenes. For more than seventy years, Houser fought for racial equality in the United States, the independence of dozens of African nations, and peace. He did not seek the limelight. He did not expect change to happen overnight. He did not stop fighting. Instead, like water over a stone, he continued to educate, organize, cajole, and support. The man was an organizer’s organizer, helping build movements but not taking much credit for himself. As a result, few outside the movement knew of him.

While speaking at the fiftieth anniversary of the ACOA, Houser reminded us that we still have a long way to go. He chose to title his speech, “The struggle never ends,” the English translation of the Portuguese saying “a luta continua.” Uttered for decades by freedom fighters in Angola, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique in the face of a recalcitrant Portuguese military dictatorship, this saying became popular the world over in the 1960s and 70s.

Houser is survived by his wife, Jean, their four children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He lived for ninety-nine orbits of the earth around the sun.

A memorial was held for Houser on Saturday, September 19 at 10am at Friends House, 684 Benicia Drive, Santa Rosa on the Green. A second memorial will be held on Friday November 6th in the chapel at Union Theological Seminary, 121st Street and Broadway, New York. It will be organized by the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). For more information, contact Ethan Vesely-Flad of FOR organizing@forusa.org.

September 29, 2015

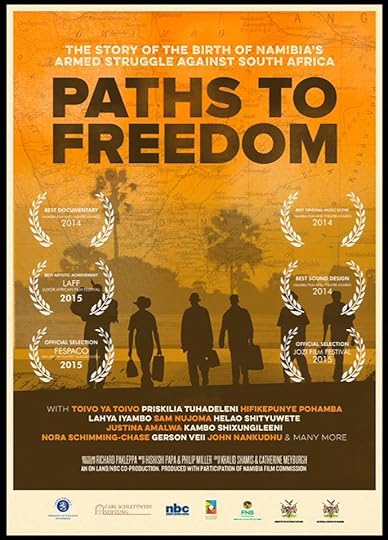

An interview with the director of ‘Paths To Freedom’, a film on Namibian liberation

Paths to Freedom is the latest from award winning Namibian filmmaker Richard Pakleppa. It takes a look at the launch of the liberation struggle by several Namibian freedom fighters, focusing primarily on the early stages of resistance to South African occupational rule in the 1960s. The film collects testimonies of the key players involved at the time, including Former presidents Sam Nujoma and Hifikepunye Pohamba; as well as former Robben Island prisoners Andimba Toivo ya Toivo and Helao Shityuwethe.

The 1960’s saw the founding of SWAPO (South West African People’s Organization) and the launch of the armed struggle to topple apartheid in Namibia. This culminated in the country’s first free and fair elections in 1989 and independence from South African rule in 1990.

Richard Pakleppa grew up in Namibia and as a student he was deeply affected by the times of revolt and activism in the 70s and 80s. He was a member of NANSO (Namibian National Students Organization) which was founded in 1984 as a non-racial, democratic and independent student organization. He is a filmmaker and activist who’s first film Saamstaan (1990) chronicled a woman’s coop of domestic workers who told their stories of what it’s like working under “Madam.” It was broadcast on NBC (Namibia’s state run broadcaster). In response the Afrikaans newspaper Republikein said that the film “breek Versioning (breaks reconciliation)”.

Paths to Freedom was showcased recently at the Durban International Film Festival in July and won the Best Artistic Achievement award at the Luxor African Film Festival in Egypt in March. In an effort to understand the genesis of this important film project I caught up with Richard and asked him a few questions.

What made you become a filmmaker?

I’ve been attracted to photographs and images and films for a long time. And I love music. So I like how films bring you close to human lives, people. And how one is working with different registers of emotion and the “material” of life through sound and picture and rhythm. Through activism where we worked with theatre and music and video the film making was also seen as a powerful tool for creating awareness, challenging, exposing , shifting things. I like the spaces that are free of the tyranny of narrative and plot. I like undiluted emotion, moments, a long single take of the burning bush in the face of a child, moods, places in which you as the viewer discover yourself, discover something of yourself.

Why did you want to tell this story? Why is this story of Namibia’s liberation struggle still important, still valid?

I think of the film as a praise song. In praise songs we remember and praise those who came before us and created conditions for us to be who and how we are today. That is true even if it is also true that the process of liberation is not completed.

What was the process like? How long did it take to make?

I made the film over 4 years. Started with no money, shot some interviews and scenes, got the main money after 2 years then the rest when I had an advanced cut. The taking out and leaving in part is a huge challenge. Especially since your research, the interviews and the archive materials you collect flood your mind with an overwhelming amount of details, stories to choose from. Documentary filmmaking cannot be capricious or arbitrary or willful or lazy. Because people trust you with their story you have to take great care. It was a struggle. But I had great interviews to work with – a huge amount of testimony. And guidance from the ancestors.

What was it like to work so intimately with these freedom fighters? How many of them have passed on since you started work on this film and what are your thoughts about that.

It is a great honor in my life to have worked with and become close to some truly amazing women and men. They all lived/live ready to die for freedom. There have been 5 funerals. Each one was also a remembering and celebrating of the life of a great and wonderful person. I wish I could tell you what huge, generous hearts these men and women have.

What was it like going to Robben Island with Helao Shityuwethe and Andimba Toivo ya Toivo?

Yes, it was amazing. They walked around the place like they had come home. Checking here and there, complaining about changes that had been made. I realised that Robben Island belongs to them. It is a deep part of their lives and their stories and their memories. It’s powerful. Because they won. They escaped. They are free to visit. To inspect the prison and the island as free men. I was overwhelmed by the power of Helao Shityuwethe and Andimba Toivo ya Toivo’s friendship, seeing them gaze into the cold mist together, their intimacy. I found a way to imagine just a little bit of the kind of solidarity they had – to keep sane in that place. Now it’s like a theme park – Robben Island for tourists. But for them it’s a place of horror and a place of triumph of endurance. We turn around a corner and suddenly the Comrade enacts a story of chilling brutality when he was beaten up just there and … how they would later laugh about it.

What can young (born free) Namibians learn from this film and this struggle? What is the “new” or “next” struggle for this generation?

Last year during the hand over of 1200 DVDs of Paths to Freedom to Namibian schools Helao Shityuwete – the man in the pink shirt in the film – said: “We are handing our story to you now. We started this struggle and it is now up to you to complete this struggle.” The struggles for freedom in Africa have been contradictory and have brought contradictory results. By remembering and praising the known and unknown heroes of our past we are called on to honour them by continuing the work they started. By being activists as they were. By caring about society. Finding a way to engage with the skills we have.

At the end of the film you post the quote:

OKURUOO

Light the holy fires

to remember the past

to remember the connection

between past and the present

Can you tell us a bit more about this–what it means, why you chose it and how it relates to the next generation?

In Herero culture Okuruoo is the holy fire that burns in the home. It keeps alive the connection with ancestors and with memories of what happened, how we got to where we are, how the actions of the people before us inform our experience in the present. In that culture it has a lot to do with landscape and the colour and shape of land and cattle and water places and the people and ancestors who established communities to which, we in the present, belong. A lot of that is expressed in songs which are like monuments. Places of memory. After the unspeakable horrors of the genocide – Herero and Nama communities were shattered and dispersed. Many proud pastoralists had been made destitute and reduced to being slave labour on their own land. As people were slowly regrouping Chief Hosea Kutako told people to light the holy fires in their houses again. It was very important. We have come through hurricanes of trauma, which after 1989 was put aside. Now Namibians are beginning to look into their pasts as part of the process of dealing with those aspects of the struggle for freedom. Struggles that have not been realized. We light that fire. The flame passes from the hands of one generation to the other. We realize it is our task, too.

Last thoughts on Namibia and where we are now?

We are in a different world with different possibilities. People have become very “depoliticized”. But that seems to be changing now. And the forms of political action are changing all over the world. It’s clear that democracy is not working well under the dictatorship of liberal capitalism. It’s clear that natural resources and wealth in the hands of the settler class, the new elites and the global corporates is not bringing an end to unacceptable poverty and inequality. But changing the ownership of the means of production is not revolutionary enough. History shows that societies need ways to insure that leaders are accountable, that they are elected to serve the people in a humble and honest way – not to lord over them; that the interests of the majority are defended, that we are not blinded by the rhetoric of the haves. I think we have the chance to imagine better solutions to many serious problems. To contribute to the circulation of critical thoughts, good ideas, incisive questions. To insist that problems be addressed in frameworks that unmask them for what they are. To really contribute to the conversation. To understand that we had a plan to create a great country for everyone and that we are serious in making that happen.

Paths to Freedom is available from Nangula Shejavali at nangula@leadingedge.com.na

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers