Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 323

November 6, 2015

New doc film, ‘We Will Win Peace,’ skillfully debunks many myths behind conflict minerals in the Congo

Washington, DC: In front of the White House an activist carries a megaphone facing a crowd. He is visibly agitated, excited as he screams: “We will win peace… in the Congo!” The Congo, or Democratic Republic of the Congo as the country is called since the ousting of autocrat Mobutu in 1997, is the scene of the most persistent concatenation of armed conflicts since the early 1990s, allegedly due to greed for raw ore and rare earth.

“It is true that the minerals in our cell phones link us to crimes against humanity.”

The activist and his colleagues from Enough Project, an American NGO that tries to “end genocide,” claim to have found the logic of these wars: rebels who rape helpless women and girls in order to ransack the vast mineral riches of eastern Congo. Their claim, as powerful as it is simple, was instrumental in paving the way for a legal novelty: a US piece of law that immediately engages with the exploitation of so-called “conflict minerals” in Central Africa including tin, tantalum, tungsten, gold (aka 3TG). Unfortunately, though, the claim is untrue – and this is what a new feature-length documentary is about.

Seth Chase, Ben Radley and their team produced a meticulously researched 90 minute film on an issue that may simultaneously be the most salient in media terms, when it comes to Western perception of the Congo, and the most misunderstood in its essence and meanings. We Will Win Peace navigates through this cleavage in both virtual and actual life. In the footsteps of Mr. Ryan Gosling, Ms. Nicole Richie, and other celebrity activists, Chase traces the making of a narrative of eastern Congo’s recurrent conflict throughout a plethora of YouTube clips. Enough Project consistently denied to be interviewed and, Radley admits, “It was certainly frustrating and revealing to experience the difficulty of holding such actors accountable when their actions cause harm.” In turn, the filmmakers do something neither advocacy nor US congress leaders seemed to have considered necessary – a series of in-depth interviews and testimonies from Congolese miners, civil society activists, and analysts who describe the impact to date of Dodd-Frank Act, Section 1502. So, how has this bill come about and what relevance has it for eastern Congo?

“It creates dogma, it makes the world black and white… while the world isn’t black and white.”

Almost ten years ago, a group of American congressmen – some of them close to the current President under whose name the eventual “Obama’s Law” is known in the Congo – went forward with a law project to break the suspected link between rape, violence, and greedy warlords. Despite the massive support of NGOs such as Enough Project and others, the draft did not make it through the house, and the Conflict Minerals Act failed. However, Enough’s leader John Prendergast and Senators Brownback and Durban did not relinquish; and an emaciated version of the Conflict Minerals Act made its way into the miscellaneous provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, a vast law package aiming at improved business regulation and consumer protection in the slipstream of the American mortgage and financial crisis. As Prendergast confessed to the late Didier de Failly, a Belgian missionary and human rights defender, the crucial accompanying measures to make transparent mining viable were then dropped for the sake of simplicity and policy success.

We Will Win Peace goes beyond merely unveiling the political ramblings around Capitol Hill. In the movie, Séverine Autesserre, a professor at Columbia University and author of several books on peacebuilding and the Congo, explains how the simple story that led to Dodd-Frank 1502 not only obscures myriad other causes and consequences of conflict and violence in the Congo but actively contributes to a biased solution with counterproductive effects such as an increase of sexual violence since the law’s adoption. Jason Stearns, the Director of the Congo Research Group at New York University, stresses the futile Western perception of Congolese “rebels on dope and opium”, looting mines and raping: “This is not what the conflict is about today, and it was not what the conflict was about when it first started in 1996.” Stearns used to lead the UN Group of Experts, a panel mandated to track violations of sanctions and human rights in the realms of arms trade and 3TG mining. In more recent reports, this panel confirms that – at least indirectly – US legislation and the ensuing de facto embargo on Congolese minerals helped smuggling to skyrocket.

Dangerous narratives create unintended consequences.

However, Dodd-Frank 1502 does not forbid anyone to trade in these minerals, it simply imposes on US stock market listed companies (and their suppliers) to report on whether or not they have sourced from the Congo and its neighbors and give proof of their efforts to perform “due diligence” in their business activities. Does that tame civil war? Enter Thierry Sikumbili, a provincial head of Congo’s mining export authority: “Can you cite one country in this region that produces arms? I don’t think so. You ask us to trace our minerals, but I would have liked the West to trace its arms. It is a bit like wanting one thing and its opposite at the same time.”

The documentary follows several miners and petty traders across Congo’s Kivu region. Artisanal exploitation of these minerals is estimated to be the lifeblood for millions of Congolese. Jean de Dieu Habani, a tailor working in one of eastern Congo’s mining hubs, is one of them. He recalls how his business was affected by the de facto embargo and how all his peers have become jobless since “Obama’s Law” remote-controls the handling of Congolese mineral trade. Debora Safari, a restaurant owner from Lemera outlines how embargo-related price drops and the ensuing monopolisation of mining through the international tin industry’s iTSCi project has left her without income as miners cannot afford eating at her restaurant anymore. Apocalypse Fidèle, a miner-turned-rebel, reports how he has been denied digging for a living and ended up joining Raia Mutomboki, the “militia of angry citizens.” Radley explains how “high levels of poverty and unemployment provide fertile ground for armed group recruitment, so if you are overly zealous in your regulation of the sector to the point that it suffocates, you will be adding as much fuel to the fire by providing fresh recruits as you are dousing by depriving militia leaders of mineral revenue.” He adds, “focusing exclusively or overly on the mining sector is not a solution, but a distraction from deeper, more thorny issues.”

It is the strength of this formidable documentary to go beyond simple stories. By giving a voice to the Congolese, it mercilessly uncovers the failure in understanding the Congo and its conflicts, partly for the sake of policy, partly for mere neglect of the government, the civil society, and ultimately the miners in the Congo. In Chase’s own words, “we wanted to show the very real consequences of trying to apply a solution from the outside, we wanted to investigate a Congo that was connected to the rest of the world via an image of war and suffering. For me this is a film about broken systems, and people trying to survive within.” We Will Win Peace is a crucial, deep, and unavoidable account of what the “white saviour” syndrome and “badvocacy” can spark if the main objective is to respond to one’s own advocacy rather than to the people it is ultimately about.

November 5, 2015

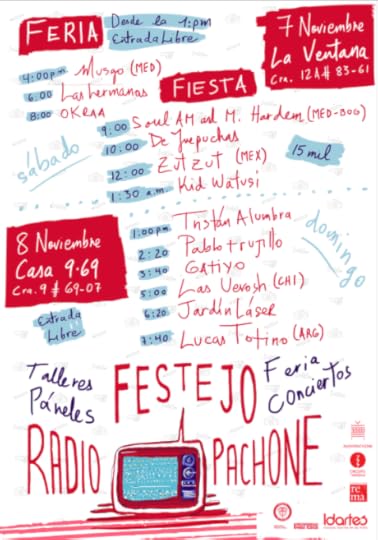

Come to the Third Festejo Pachone in Bogotá

About five years ago, three friends and I gathered in an apartment in downtown Bogotá, Colombia, and decided to create an online radio station. We called it Radio Pachone. We didn’t know how to properly record sound, or how to produce a show, or how to edit audio, but we were sure that there were many things that we wanted to talk about and that they weren’t being mentioned in mainstream media.

So we looked online, we reached out for help, we asked people to loan us equipment and, since the very first show, new friends started to join us, excited to contribute their knowledge to make this thing even better. Our small radio-thing immediately started to become larger than we had ever thought.

We had planned to use it to talk about music, movies and artists from Colombia and Latin America (and beyond) that we enjoyed but had minimal (or no) coverage in local media. Yet, soon we were debating pressing cultural issues with committed and interesting artists and activists. We were doing beautiful soundscapes and sound experiments. We were broadcasting live concerts from our studios – which began as that apartment’s living room, and then moved to anywhere we could fit – and not only with Colombian bands, but also with people coming from all over the world.

We were meeting a lot of incredible, talented people, but many of them had trouble making a living from doing the things they loved (just like us, who worked in Radio Pachone for free). So we joined forces with our friends from Fundación Rema and we decided to create a festival where all of the interesting people we had met – and the others that we knew were out there – could meet each other, create networks, debate arts, culture and beyond and, hopefully, start new projects together.

We wanted it to be an open, inviting festival, where the attendants would be as important as the people showcasing their work, so we called it Festejo (or “Celebration”). After crowdfunding and navigating the always intricate bureaucracy of the city, we staged the first Festejo Pachone in June, 2013.

It was a blast. Bogotá’s unpredictable rain came and went with the violence of an insecure emperor’s army, but also about a thousand people came and went through the live discussions, the live music shows and the stands for independent artists, designers, publishers, record labels and so on that we had lined up that day.

After its success, my friends from Radio Pachone (when I had already moved away) staged the second Festejo Pachone in 2014, also in Bogotá. The city backed down from giving the permit to use a public park for it less than a day before it was scheduled to happen. Fortunately, there are now many friends around this project and, with their help, the Festejo II still happened that day, just in a different location.

This Saturday 7th and Sunday 8th, the third Festejo will happen in Bogotá, and if you happen to be around, you really should attend. It will be a great showcase of interesting things happening around the city, which are plentiful.

(When we started, I remember saying that we wanted to make people stop saying “there is nothing to do in Bogotá,” because there were always many things to attend, you just had to lose that mentality and venture out there. Now, the Festejo is part of the Capital de Festivales movement, a group of year-round festivals and events that give bogotanos a lot to do.)

At the third Festejo, there will be booths for independent creators, there will be discussions about the state of arts and culture in the city, the country, the region and the world, and there will be 12 concerts by bands coming from Colombia, Argentina, Chile and Mexico.

Most of this will be free (except for things happening on Saturday after 9:00 Pm, when you would have to pay 15,000 pesos, or about 5 U.S. dollars) and most of it will happen right at the heart of Chapinero, our spiritual home in Bogotá.

Saturday will be at La Ventana de la T (Carrera 12A # 83-61). Sunday will be at Casa 9-69 (Carrera 9 # 69-07).

Check out the program here:

Check out some of the bands, too:

Here’s the very undescribable, but also very awesome Chilean duo Las Uevosh

Here’s the techno-pop-culture jams from Bogotá’s De Juepuchas

Here’s Argentinian Lucas Totino with his cool rock

Hope you can make it!

Incumbent Alassane Ouattara’s electoral sweep might be a good outcome for Côte d’Ivoire

The contrast between the October 2015 (two Sundays ago) and 2010 presidential elections in Côte d’Ivoire could not be any starker. In 2010, the incumbent president, Laurent Gbagbo, refused to step down, despite internationally-endorsed electoral results which indicated the victory of his rival, Alassane Ouattara. A four-month stand-off ensued, with both men declaring themselves president. In April 2011, pro-Ouattara forces swept into the country’s commercial capital, Abidjan, and captured Gbagbo (with some assistance from France and the UN), paving the way for Ouattara to assume the presidency. The post-electoral fighting resulted in about 3,000 deaths and a million displaced people. A few months later, Laurent Gbagbo was transferred to the International Criminal Court in The Hague to account for his role in the post-electoral violence. Against this backdrop, the 2015 election was laudable for its absence of violence. There were virtually no serious incidents reported anywhere in the country. The election was peaceful, deemed free and fair by election observers and the outcome — Ouattara’s resounding victory with 83,66% of the vote in the first round — was accepted by his rivals.

Ouattara’s margin of victory and the distribution of his support also mark a clear difference with the 2010 election. The 2010 poll produced very strong regional electoral cleavages, with Ouattara gaining the vast majority of his votes in the (largely Muslim) North and Gbagbo drawing his support from the (largely Christian) South. These patterns clearly replicated the division between the two sides in the country’s recent civil war. It is all the more striking then that in 2015 Ouattara received the majority of the vote in all but 2 of the country’s 30-plus regions. While voters’ area of residence and their religion were very strong predictors of vote choice in 2010, they no longer played such a role in the most recent election.

Yet, Ouattara’s overwhelming victory throughout the country should not be seen as synonymous with a complete reconciliation between the previously hostile parts of the country. Some tension, antipathy and resentment of perceived “victor’s justice” are still palpable in the South. Ouattara’s forces were never held to account for their role in the post-electoral violence, a role recently criticized by the Human Rights Watch. Rather, many Ivorians probably concluded that Ouattara’s victory was inevitable in the absence of any viable opposition to him. Gbagbo’s Popular Ivorian Front lost much of its weight since Gbagbo’s downfall, with the successor, Pascal Affi N’Guessan, garnering only 9.3% of the vote. Indeed, turnout in former Gbagbo strongholds in the South was lower than in the North, indicating that many of Ouattara’s opponents decided to stay home, rather than actively support any of his rivals. At 54.1%, the electoral turnout for the country as a whole was still respectable, but considerably lower than the 80% recorded in 2010.

Remarkably, much of the Ivorian political class seemingly came to the conclusion that it was better to join the incumbent than to campaign against his. Ouattara’s striking electoral “knockout” owed much to the “bandwagoning” of some of his former adversaries. Chief among them was Henri Konan Bedié who endorsed Ouattara and actively campaigned for him. Bedié’s support of Ouattara appears all the more calculated because of Bedié’s history of questioning Ouattara’s nationality, with the infamous concept of Ivoirité, aimed to exclude many Northerners from participating in politics. This time around Bedié and his spokesmen told voters in the center of the country that voting for “Alassane [Ouattara] was the same thing as voting for him [Bedié].” Several other Ouattara’s rivals withdrew from the presidential campaign.

Still, despite the cynicism of the political class, Ouattara’s electoral sweep might be a good outcome for Côte d’Ivoire. His resounding victory throughout the country could help overcome to some extent the divisive legacy of the civil war. More importantly, an orderly election without violence is a good step towards recovery, helping the country heal and continue its economic growth. Yet, in the long term, Côte d’Ivoire would benefit from more robust and principled opposition.

November 3, 2015

Beasts of No Nation and the child soldier movie genre

Distributed by Netflix, American director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s film adaptation of Nigerian Uzodinma Iweala’s novel Beasts of No Nation is receiving rapturous praise from mainstream critics in Europe and the United States, nearly all of whom, in asserting the film’s singularity, seem distinctly unaware of the fact that it belongs to a rather robust, longstanding cinematic subgenre. Extending the category of the war film, this particular subgenre sees African child soldiers perpetrating acts of extreme violence within vaguely sketched sociopolitical conditions.

Like the novel on which it is based, Beasts takes place in an unnamed African country shaken by an unspecified and ongoing conflict. But while the novel is written in a variant of English that strongly suggests the influence of various Nigerian dialects, the film’s first act features characters speaking Twi, an Akan language widely used in Ghana. That Twi goes unmentioned in the publicity surrounding Beasts is a measure of the filmmakers’ commitment to their gimmick—to the coy presentation of an ill-defined “Africa” as a screen on which spectators might project their assumptions. Indeed, mainstream critics are split on the subject of the film’s “real” setting: A. O. Scott sees Sierra Leone or Liberia, while David Edelstein insists it’s the Democratic Republic of Congo. In any case, the film sets out to depict one possible process through which a mere boy might become a murderous soldier, strategically dispensing with Twi as soon as the boy, Agu (played by the remarkable Abraham Attah), takes to the forest to escape the troops responsible for the deaths of his father, brother, and friends. As if in a dream, the boy suddenly finds himself in thrall to a charismatic commandant (played by the great Idris Elba) who leads a squadron of child soldiers on an ambiguous quest to “reclaim” the country.

It is a testament to Elba’s talent and inventiveness that he rejects standard actorly approaches to the madness of military leaders, offering a surprisingly lethargic, drawling take on the brutal commandant. Far from fresh, however, is the film’s take on the subject of child soldiering in sub-Saharan Africa. At least two writers—Julie MacArthur on Shadow and Act and Zeba Blay on The Huffington Post—have drawn attention to such important antecedents of Beasts as Newton Aduaka’s Ezra (2007), Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire’s Johnny Mad Dog (2008), and Kim Nguyen’s War Witch (2012), films that, in hailing from various sites and sources of production, have helped to construct the child-soldier subgenre as a truly transnational affair.

That Fukunaga’s Beasts breaks no new narrative or thematic ground is scarcely a sin. But the film evokes the type of Tarzanism by which Western cultural producers perpetually seek to gain artistic legitimacy, proffering a cinematic vision of reflexive violence (couched as inherently, ahistorically “African”) as well as an especially aggrandizing, extratextual portrait of an American male director who made a “risky,” malarial, downright Conradian trek into the darkness of the global South. Fukunaga’s film was, as many a press release has made clear, filmed in Ghana. Less available, however, is the fact that Fukunaga shot retakes in Brazil, letting the lush landscape of that South American country stand in, however unconvincingly, for some of the environmental specificities of West Africa.

At the same time that Beasts is being positioned as “authentically” African in Western press accounts, the film’s authorized distribution pattern has effectively ignored, even actively excluded, African contexts of reception. The problem is partly structural: Netflix reportedly paid roughly $12 million for the film’s worldwide distribution rights, but the term “worldwide” refers, in this instance, only to locations where Netflix may be accessed (and where, for that matter, high-bandwidth streaming is possible in the first place). Netflix is inaccessible in Ghana, where Beasts was shot, as well as throughout West Africa. Even if it were accessible, however, local conditions of access to the Internet are such that it would be rather frustrating (to say the least) to attempt to stream bandwidth-heavy content like Fukunaga’s 137-minute film. Beasts is thus multiply distanced from the West Africa in which it was made and in whose name it claims to speak.

Significantly, West Africa is being written out of new narratives of film distribution that tout Internet access in general and Netflix penetration in particular, rendering the region a veritable blank space even as its screen depiction is central to “revolutionary” modes of dissemination. The first narrative fiction film to be released simultaneously in theaters and on Netflix, the “history-making,” “epoch-defining” Beasts is presently unavailable via either platform in the very places where it was shot—in the very region that it purports to depict. Such harsh irony is painfully familiar, with deep roots in global capitalism and an obvious analog in the sort of “parachute journalism” that produces reports on the global South for the exclusive edification (and delectation) of consumers in the global North.

Not only have such African filmmakers as Aduaka, , , Lancelot , , and (among many others) tackled the topic of youth violence, rendering Fukunaga’s Beasts redundant at best, but some of the industrial contexts in which these directors have worked are witnessing renewed efforts to reclaim traditional spaces of exhibition for African films. Consider, for instance, the New Nollywood Cinema, a movement to produce features on celluloid and high-definition digital video for distribution to upscale multiplexes around the world. If Beasts can’t be legally streamed in a Netflix-free West Africa, then it should at least be screened in such Ghanaian and Nigerian venues as Silverbird, Ozone, and Genesis-Deluxe.

Probably by design, Beasts of No Nation has found itself at the center of debates about movie-going in the digital age, with four of the biggest theater chains in the United States boycotting the film on the basis of its immediate (rather than delayed) availability on Netflix. Partly in response to this boycott, Netflix has modified its initial narrative of abundant availability, suggesting that, in collaboration with the fledgling distribution company Bleecker Street, it is now restricting the theatrical exhibition of Beasts to a few art house cinemas in London, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, strictly to qualify the film for Oscar nominations.

While much has been made of the paltry box-office returns on Beasts, with some pundits intimating that “African” subjects are never really salable, no one in Hollywood seems willing to concede the existence, let alone the viability, of African markets for theatrically distributed feature films. Even if Silverbird, Ozone, and Genesis-Deluxe are unlikely to dramatically boost the film’s worldwide grosses, it is worth questioning the ethics of a distribution policy that, with a joint focus on Oscars and the Netflix “brand,” completely excludes Beasts of No Nation from legal consumption in much of sub-Saharan Africa. Such a lacuna powerfully symbolizes the opportunism of a film that must be pirated in order to be seen in its primary site of production—and that, in its end credits, thanks Nigerian actor-director Kunle Afolayan by misspelling his name.

Beasts of No Nation represents the latest reminder that Western constructions of “Africa” are often deployed for the sake of brand differentiation—as ways of separating the “brave” from the staid, the “bold” from the boring. Fukunaga, like Sidney Pollack with 1985’s Out of Africa, has “heroically” made his “African” film, and executives at Netflix are being similarly lionized for agreeing to distribute it. If his experience in Ghana sets Fukunaga apart from filmmakers who confine themselves to Hollywood soundstages, then it also separates Netflix from its competitors in the video-on-demand market, none of which have subsidized “African” projects.

Perhaps unintentionally, the opening shot of Beasts concretizes the very assumption that appears to be underwriting the lack of legal availability of the film in West Africa—namely, that the region is without screens on which to legitimately project Western cultural products. A discarded SANYO television set, its glass screen missing, frames our first glimpse of Fukunaga’s Africa: an impromptu football match monitored by boys who later try to sell the television set (what, with an entrepreneurial panache, they label “an imagination TV”) to a Nigerian soldier. “The Nigerians are keeping the peace,” explains Agu in voice-over. “They are always buying things, so they are easy to be selling to.” (Netflix and Bleecker Street, in doing nothing to ensure the film’s legal availability in media-literate Lagos, apparently didn’t heed Agu’s advice.)

At first, Beasts is in potentially productive conversation with the syncretism of much of African popular culture, featuring a male character (Agu’s older brother) whose bedroom walls are covered with images of Black Americans (from Michael Jackson to Snoop Dogg), as well as a media-rich environment in which Telemundo programs compete for attention with Perry Henzell’s Jamaican film No Place Like Home. When several wandering boys encounter a disgruntled “witch woman” who, accusing them of theft, promises that their futures will be dark, the film is seemingly drawing on one of the richest Nollywood traditions, mixing juju and social realism. Such rewarding (and perhaps accidental) references to West African representational traditions disappear after only a few minutes, however—never to return. Beasts of No Nation is a purportedly African story made in a conspicuously American style, with a brief average shot length, slow-motion interludes, and the ostentatious shakiness of handheld camerawork (which plainly replicates the iconography of Western “eyewitness” reporting).

Beasts is, like Blood Diamond (2006) and The Last King of Scotland (2006) before it, the type of film that seemingly satisfies so many requirements of the Western imagination, including through the off-screen mobilization of Fukunaga’s personal, adventurist narrative. The experience of making Beasts gave the director a chance to boast about having contracted malaria on the African continent, presumably after foolishly refusing the antimalarial pills that must have been abundantly available to him. In published interviews (such as one with Rolling Stone, tellingly titled “How ‘Beasts of No Nation’ Almost Killed Cary Fukunaga”), the filmmaker suggests that his bout with malaria provided an unexpected creative boost—a chance to finally sit still and tweak his “African” screenplay. That there are hundreds of millions of global malaria sufferers for whom the disease is decidedly not a source of pride is apparently lost on Fukunaga, who, with Netflix’s help, is ensuring that Beasts of No Nation is intelligible only as a familiar Western fantasy.

November 1, 2015

What is the university for?

In the wake #FeesMustFall protests which electrified South Africa one week ago, much has been made about the way in which universities have been bent to the needs of international capital and its neo-liberal demands. Students and workers rightly condemn the expense, outsourcing and indebtedness that make a mockery of the university’s ‘ideals’ of thoughtfulness, critique and freedom. This should be so. Yet we should not be tempted to idealize the university ‘as it was’ – especially in a country like South Africa, where universities have meant oppression, segregation, epistemological violence and apartheid, as much as (or even more than) they have meant ‘knowledge.’

Instead, unlike in the global north, in South Africa the possibility exists to admit to two ways we hear the parsing “for” in “what is the university for.” On the one hand, we hear a question about what the university is supposed to be doing now, and on the other, we hear a question about the university’s standpoint. With the emergence of a new scripting of the university in the image of capital and its drive to accumulation, the question of what the university stands for seems to take precedence over the question of what the university is to be doing now. The demand is not to reverse the orders of these questions but to realize that in South Africa today, the opportunity exists to study both senses of hearing the phrase “what is the university for”, in their very simultaneity, and at whatever speed. In such simultaneity the university may open itself to a future in which it more searchingly requires its students, faculty and workers to think ahead by asking what we should be desiring at the institutional site of the university.

We would be remiss if we did not think of the university as more than an institution that preserves the best of what we have learned for the greater public good. The university is, and must be uncompromisingly intellectual in its desire, commitment and pursuits of these two simple, albeit contested ends. An emphasis on what the university ‘was’ is conservative; we need to be thoughtful. The university is perhaps to be approached less as a question of putting knowledge in the service of the public, than as a space for inventing the unprecedented. .

As much as universities are thought to advance knowledge, its reigning ideas have shifted considerably over the centuries. If at one moment the reigning idea of the university was that of reason, it later emerged as an institution grounded in the concept of culture. Today it is being appropriated to the logic of the market and a prospective future of growing indebtedness. Taken together, this latest installment of the idea of the university that appears to be proliferating globally is creating a deep sense of anxiety, alienation, and a feeling of proletarianization. The university is becoming a hyper-industrialized information machine that is beginning to reveal itself as an information bomb.

In contrast to the hyper-industrialized information machine, the university’s uncompromising intellectual sense historically derives primarily from the idealism that brought it into being, and in the second, in its overwhelming, but not exclusive location in the changed circumstances of the Second World War. Such idealism contended with the hegemonic formations of state, capital and the public sphere in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In Africa, the birth of the university accompanied the wave of nationalist independence movements that swept through the continent in the aftermath of the Second World War, with the promise of development underwriting its public commitments. And in South Africa specifically, the university was tied more fundamentally to the determinations, intensification and demands of a racializing state and capitalist formation. The distortion in the original idealism of the university has been overtaken by the long twentieth-century in which the university became entangled in an even longer process of dehumanization. It has also been overtaken by a rapid expansion of technological objects through which research and teaching are now extensively mediated, resulting in, among other manias, the fetish of outcomes and measured results.

Bound at once to a contract with the state and simultaneously to a public sphere, the university has had to reinvent its object of study, abiding by duration and commitments to the formation of students in respect of its reigning ideas. It is in the interstice of these seemingly opposing social demands that the inventiveness of the university as an institution is most discernable. Rather than being given to the dominant interests of the day, whether state, capital or public, the university ought by virtue of its idealism to be true to its commitment to name the question that defines the present in relation to which it sets to work, especially when that question of the present may not appear obvious to society at large. Yet, in naming this question the university is ethically required to make clear that it does not stand above society.

Today there is growing concern that the university has lost sight of its reigning idea – the demands of radical critique and timeliness – and all the contests that ensue from claims made on that idea. In the process its sense of inventiveness has been threatened by an encroaching sense of the de-schooling of society, instrumental reason and the effects of the changes in the technological resources of society that have altered the span of attention, retentional abilities, memory and recall, and at times, the very desire to think and reason. Scholars around the world bemoan the extent of plagiarism and lack of attention on the part of their students; features that they suggest have much to do with the changes wrought by the growth and expansion of new technological resources. What binds the university as a coherent system is now threatened by the waning of attention and the changes in processes of retention and memory. In these times, retention has been consigned to digital recording devices. Students and faculty are now compelled to labor under the illusion that the more that we store and the more we have stored, the more we presumably know.

Here again we can learn from our past. The movement that unfolded in the 1980s at SA universities was a statement of force against the cynical reason of apartheid, yes, but it also contained an element of the creative act, the process of inventing the unprecedented, which underwrote every effort at turning apartheid’s rationality on its head. It is a version of the creative act that is now threatened by the onset of memory loss. In its place seemingly more vacuous words have come to take the place of formidable concepts in formation. Words such as ‘efficiency’ and ‘excellence’ now replace more thoughtful and thought-provoking notions of “epistemological access”. Where the concept of “epistemological access” generated extensive curricula debate in the 1980s, efficiency and excellence serve as buzzwords with little or no epistemic grounding. And newer scripts of creativity are producing fantasies that may yet prove to be the nightmare for students in the future. The speculative logic of the student as an entrepreneur of the self lends itself to the promise of consumption and fulfillment, but at the same time, drags students into a state of limbo and mere functionality. Against this slide into mindless creativity, an older notion of the creative act, like the notion of a work of art that resists death, must surely be a possible concept upon which to constitute a future university. This is a work of art that calls on a people that does not exist yet. It is the idea of the university that creates the space for the invention of the unprecedented.

There has never been a more hazardous time to forget to ask “what is the university for?” The university’s future resides in cutting into the future and into established knowledge. All the while, we should hear in the echoes of the past, the demand to keep desire alive, to remain awake, and to constitute a community that is open to the future.

In South Africa, where the university under apartheid was placed in the service of a cynical state rationality that divided society along race, class and gender lines, the question of our time now demands that we ask how we reinvent the idea of the university. We need to think once again about approaches to technology, the state and the public sphere – and how each gives a view on the desire that now remains repressed in our respective knowledge projects. We need to recuperate the sense of attention and play, of the creative act as opposed to the banality of neoliberal creativity, that will prove indispensable for naming our present and finding our way out of those predicaments that threaten to undermine the best of our knowledge upon which the future of our students, faculty, its workers and that of the institution of the university rests.

October 31, 2015

Africa is a Radio: Season 2, Episode 6

Africa is a Radio show for October 2015. Sean and Elliot are on a break from the show, so Boima fills in with some new tunes from around the African Diaspora, with special shout outs to the South African student protesters, and young Afrobeats artists in the UK.

Tracklist

VVIP – Skolom feat. Sena Dagadu

Aewon Wolf – Sukumani 2.0 feat. Mashayabhuqe KaMamba

Pablo Vittar – Open Bar

Maffalda – Fuck Your Feelings

Ifé – 3 Mujeres (Iború Iboya Ibosheshé)

Leka el Poeta & Master Boy – Ella Queire Hmm Hmm Hmm

Atumpan – African Wine

Olami Still – Call on me

J Hus – Dem Boy Paigon

Mazi Chukz – SOS feat. Baseman & Ezi Emela

Khuli Chana & Patoranking – No Lie

Ace Harris – Drop feat. R. City, Lloyd Musa, and Yung Muse

DJ Flex and DJ Dotorado – Bando Remix

Aero Manyelo – DNA Test

Big Space – Long Ride

Olatunji – Ola

October 30, 2015

Weekend Music Break No.87

Weekend is here so that means it’s time for another music break! If there’s any theme this weekend, it is artists who are looking back into the past to tap into some kind of inherited tradition or cultural roots… and then one just for fun. Enjoy!

We covered Gabacho Maroconnection earlier this month in our Liner Notes series — here they perform their song “Allah Moulena”; We also ran an interview with Somalia via Seattle rappers Malitia Malimob — this song samples traditional Somali sounds; A throwback tune from Youssoupha (who’s 2015 album NGRTD is pretty great) — a dedication to his father the great Tabu Ley Rochereau; Fally Ipupa taps into some traditional rural Congolese sounds, updating them with a 2015 Kinshasa flair; D Banj and Akon also bring some new ancient rhythms to the club… it would be really great to hear this kind of rhythm on the dance floors of mainstream clubs in New York or Las Vegas… recent Instagrams by super producer Swizz Beatz point to the possibility of that reality not being too far away; Blsa Kdei taps into a classic Highlife sound, with the lilting guitar on “Mansa”; Featurist gets particularly traditional with his fashion style and moves in this video for “BABAAH” (the dance of grandfather!); Ghanian SK Kakraba is a master of the Gyil — living in Los Angeles he recently released a record on the Awesome Tapes from Africa label; Malian Kora player Abou Diarra plays a live session accompanied by acoustic guitar; and finally, after seeing great success in the UK for his Afropop hit “The Thing“, Atumpan goes dancehall and turns in a video for “African Wine” shot at this year’s Nottinghill Carnival in London.

The Community Video Education Trust

I’ve had a really hard time staying focused for the past couple of weeks, given the current protests in South Africa. Everytime I opened Twitter, I was bombarded by images and videos from Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Pietermaritzburg (to name just a few) that that simultaneously shocked and inspired me. I found myself drawn to these social media outlets, Watching the 11-minute film about the #FeesMustFall protests earlier this week, I found myself thinking about how the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa was captured, preserved and understood on and through film. One amazing digital collection that enhances understandings of the South African struggle against apartheid through the medium of film. That collection is the Community Video Education Trust.

The Community Video Education Trust (CVET): Documentary Footage of the Anti-Apartheid Struggle in South Africa is one such collection that shows the potential of video for not only reaching broader audiences, but also portraying a different perspective that is possible through oral history alone. CVET is Cape Town-based project formed in 1976, geared towards democratizing technology through training communities in video production. This site is a collection of those videos, documenting a side of the liberation struggle from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s that is not as widely available as the more traditional narratives of the struggle against apartheid. The videos were digitized and assembled into the website as it stands to day through a collaboration between result of collaboration between the Michigan State University African Studies Center, the South African Film and Video Project (SAFVP), MATRIX: Center for Digital Humanities and Social Sciences (as part of their African Online Digital Library) and CVET.

Delving into the videos, there is a wealth of material available from footage of the funeral of the Gugulethu Seven to Abdullah Ibrahim’s return from exile to Albie Sachs moving return to District Six. You can also view important historic events like, for example, the launch of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in Cape Town in 1983.

If you don’t have specific issues or figures to search for, you can also sort through the videos by organization, person, and genre. The project recently updated all of their videos from Real Player, which will help to sustain this project as technology continues to develop, preserving this important videos that challenge top-down accounts of this era. As Jacqueline Mainguard wrote in a 1995 article for theJournal of Southern African Studies, “no single cultural form is able to express the full experience of apartheid although specific representations may seem to fulfill a sense of the totality of the experience” (Mainguard, 659). The representations contained in the CVET collection help to supplement other accounts to strive towards finding “a sense of the totality of the experience” of the anti-apartheid struggle.

As always, feel free to send me suggestions via Twitter (or use the hashtag #DigitalArchive) of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

*This post is No. 22 in our Digital Archive series covering African archives on the web.

The Brother Moves–the pan-Africanist children who are here to realise Sobukwe’s ideals

“Kancani kancani njayam’, kancani kancani njayam'”. Makhafula Vilakazi utters the words, the poet in servitude of the masses, echoing a phrase familiar to the innercity hustler, dweller, and worker. Little by little my guy, little by little, he says. The Brother Moves On are with him on stage, regulating rhythm, distilling this code of the streets, this thug mantra. The place? A club in the heart of eGoli, the city of dreams. The occassion? A joint gig with the Blk Jks for a once-off project called The Blk Rabbit. Makhafula’s donning a t-shirt with Robert Sobukwe’s face on it. He is backed by a band which understands Sobukwe’s significance and, I assert, see themselves as the pan-Africanist children who are here to realise his ideals. The overall impact of the performance razes through the conscience, like a paper cut which leaves deep-seated scars. After the poem, the lyrics.

Guitarist Zelizwe Mthembu’s (Zweli) voice takes charge and the band follows his lead. He narrates the story, the all-too-familiar tale, of getting mugged in Jozi. You hear it all the time how people’s phones, wallets and dreams get snatched real quick quick in a city that’s always on a giddy prowl for an opportunity to take ownership regardless of who the owner is. Zweli’s letting the music guide him in telling every person’s worst nightmare: Jozi’s street regulators will jack you of your only source of income, ask any musician.

“Ai dude, like me, I kinda got ticked off about it and I thought I should write a song about it, ’cause I got mugged like four times.” That’s Zweli speaking. The location of the conversation? Jazzworx, a renowned studio where the band’s been camping for the weekend to record songs which’ll either make an EP or end up on some project. They were unclear at that point, still in talks which would hopefully enable their music to transcend the circle of followers which has been expanding as a result of the band’s regular, expertly-executed gigging.

Jazzworx is a rap fan’s ama-kip kip store. Framed album covers by artists such as Proverb, Pro-kid and HHP line the walls from the moment one enters the studios, grappling for space from one end, right through to the living room where the conversation with Zweli’s happening. He almost got his guitar taken during one of the mugging attempts. “I was like ‘yho, no this can’t keep happening man, I’m gonna complain, maybe the universe will hear my cries’,” he says.

The song gets into the why of robberies by letting the mugger speak for themselves. “Each verse [introduces] a different character. First verse is the guy who describes how he got robbed. The second verse is from the perspective of the criminal; he’s saying ‘yo man, you live this indulgent [lifestyle] and wherever you are, you’re just showing people how much money you have while we’re sitting here hungry’ so I’m gonna take your shit,” continues Zweli.

The third character is inspired by Ma’leven, a familiar name given to hardboiled thugs in the hood. In this particular case, it’s a robber Louis Theroux meets while out on one of his out-there field experiments. “I took some lines from him and I put them together to show you the mind of a criminal. And the fourth verse is just an older man complaining like ‘this shit needs to stop!'”

Ultimately, then, Shiyanomayni’s a song about wealth distribution. It’s the seemingly-hollow dream of the realisation of an equal society where breaking bread equally becomes the norm as opposed to a daily cry on protesters’ placards.

So, shiyanomayini sbali, (and that includes your data bundles to stream the video below)!

*”Shiyanomayini” is from The Brother Moves On’s Black Tax EP and is available to stream/purchase on Bancdcamp. Their remastered Golden Wake EP is out today, also via Bandcamp.

*The band will be embarking on a European tour in December:

Zurich(Rote Fabrik) 3/12/2015

Rennes(Transmusicale) 5/12/2015

London(Birthdays) 6/12/2015

The Brother Moves On Have Released Two New EPs + A Video

“Kancani kancani njayam’, kancani kancani njayam'”. Makhafula Vilakazi utters the words, the poet in servitude of the masses, echoing a phrase familiar to the innercity hustler, dweller, and worker. Little by little my guy, little by little, he says. The Brother Moves On are with him on stage, regulating rhythm, distilling this code of the streets, this thug mantra. The place? A club in the heart of eGoli, the city of dreams. The occassion? A joint gig with the Blk Jks for a once-off project called The Blk Rabbit. Makhafula’s donning a t-shirt with Robert Sobukwe’s face on it. He is backed by a band which understands Sobukwe’s significance and, I assert, see themselves as the pan-Africanist children who are here to realise his ideals. The overall impact of the performance razes through the conscience, like a paper cut which leaves deep-seated scars. After the poem, the lyrics.

Guitarist Zelizwe Mthembu’s (Zweli) voice takes charge and the band follows his lead. He narrates the story, the all-too-familiar tale, of getting mugged in Jozi. You hear it all the time how people’s phones, wallets and dreams get snatched real quick quick in a city that’s always on a giddy prowl for an opportunity to take ownership regardless of who the owner is. Zweli’s letting the music guide him in telling every person’s worst nightmare: Jozi’s street regulators will jack you of your only source of income, ask any musician.

“Ai dude, like me, I kinda got ticked off about it and I thought I should write a song about it, ’cause I got mugged like four times.” That’s Zweli speaking. The location of the conversation? Jazzworx, a renowned studio where the band’s been camping for the weekend to record songs which’ll either make an EP or end up on some project. They were unclear at that point, still in talks which would hopefully enable their music to transcend the circle of followers which has been expanding as a result of the band’s regular, expertly-executed gigging.

Jazzworx is a rap fan’s ama-kip kip store. Framed album covers by artists such as Proverb, Pro-kid and HHP line the walls from the moment one enters the studios, grappling for space from one end, right through to the living room where the conversation with Zweli’s happening. He almost got his guitar taken during one of the mugging attempts. “I was like ‘yho, no this can’t keep happening man, I’m gonna complain, maybe the universe will hear my cries’,” he says.

The song gets into the why of robberies by letting the mugger speak for themselves. “Each verse [introduces] a different character. First verse is the guy who describes how he got robbed. The second verse is from the perspective of the criminal; he’s saying ‘yo man, you live this indulgent [lifestyle] and wherever you are, you’re just showing people how much money you have while we’re sitting here hungry’ so I’m gonna take your shit,” continues Zweli.

The third character is inspired by Ma’leven, a familiar name given to hardboiled thugs in the hood. In this particular case, it’s a robber Louis Theroux meets while out on one of his out-there field experiments. “I took some lines from him and I put them together to show you the mind of a criminal. And the fourth verse is just an older man complaining like ‘this shit needs to stop!'”

Ultimately, then, Shiyanomayni’s a song about wealth distribution. It’s the seemingly-hollow dream of the realisation of an equal society where breaking bread equally becomes the norm as opposed to a daily cry on protesters’ placards.

So, shiyanomayini sbali, (and that includes your data bundles to stream the video below)!

*”Shiyanomayini” is from The Brother Moves On’s Black Tax EP and is available to stream/purchase on Bancdcamp. Their remastered Golden Wake EP is out today, also via Bandcamp.

*The band will be embarking on a European tour in December:

Zurich(Rote Fabrik) 3/12/2015

Rennes(Transmusicale) 5/12/2015

London(Birthdays) 6/12/2015

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers