Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 321

November 16, 2015

The “refugees welcome” culture

In June 2012, several refugees in the city of Würzburg stitched up their mouths to protest the lack of response to their political demands. Four demands have been at the core of the reinvigorated refugee movement ever since: Germany should abolish all Lagers (asylum centres in which the large majority of asylum seekers is housed, sometimes for years and decades, and often in isolated areas of the countryside), stop all deportations, abolish mandatory residence law (Residenzpflicht, a legal requirement for many refugees to only live and move within narrow district boundaries defined by the local foreigners’ office) and guarantee refugees the rights to work and study. The refugee movements’ long-standing critique of German asylum law and the discriminatory regulations governing the lives of many asylum seekers has gained visibility in recent years – yet in the past months, it has been eclipsed in the press and in public debate by the new idea of a German Willkommenskultur (“welcoming culture”). Heeding the history and present of refugee resistance in Germany has never been more crucial.

The recent refugee movements in Germany are part of the larger struggles of immigrants and minorities against racism in post-War Germany (e.g. the Ford strike in 1973, or the movement of Antifa Gençlik, founded in 1988). The history of racist violence, which came to head in the reunified Germany of the early 1990s, provides an important reference point for current debates. Increasing arson attacks on asylum centres, and racist pogroms in the 90s were cited as important justification for claims by politicians and the media that Germany had “reached capacity”. As a result, the German government severely restricted German asylum law in 1993.

Subsequently, self-organisations such as the Refugee Initiative Brandenburg brought their critique of isolation and human rights violations in German asylum homes to international attention. Other refugee organisations such as The Voice, Karawane and Refugee Emancipation developed strategies to reach out to refugees and invite them to join a political struggle for human rights that included speaking out against the total lack of education and work opportunities and denial of health care.

The revived refugee movement in 2012 was convinced that the master’s tools – individualised recourse to the courts and bureaucratic labyrinths – would never dismantle the master’s house. Refugees from all over Germany defied mandatory residence law, mobilised across Lagers and set out on a protest march from Southern Germany to the federal capital, insisting that they must be present and visible when decisions about their lives were made. They occupied public spaces, buildings, embassies, churches, trees and roofs in Berlin, Munich, Hamburg and Hannover and took to hunger strikes.

While the refugee movement eventually gained access to the mainstream media and shifted the discourse on migration, asylum and refugees slightly, this was recently swept away in the context of Europe’s “refugee crisis”. Starting this past summer, thousands of Germans offered their support to newly arrived migrants, and Germany was lauded in the international press as the ‘welcoming champion’. Yet, while the current flurry of activity offers conveniently de-politicised gestures of charity, it mostly ignored or sidelined refugees who were already self-organized. These groups have made clear that sincere support must engage in the politics that frame causes and experiences of the flight to Europe as well as the experiences refugees make here.

A colonial mask of silence is being put back on refugees through the charity dimension of the Willkommenskultur hype: It “prevents her/him from revealing those truths, which the white master wants ‘to turn away,’ ‘keep at distance’ at the margins, invisible and ‘quiet’”.

Rather than thanking Germany for its supposed generosity, the refugee movement in Germany has not tired to point out the past and present interconnectedness of prosperity and peace in Germany with poverty and war in other parts of the world: it scandalizes neocolonial resource extraction from the Global South and weapon exports, and generally calls for resistance against nationalist, racist and capitalist border regimes. It is uncomfortable for the majority of German society to be faced with people as (political) subjects who frame their demands from a postcolonial perspective, who speak out against rampant racism across German society, and who refuse to differentiate between socio-economic and political refugees by pointing out that economic questions are also political.

But the racist violence of the 1990s euphemised as “concerns of the citizenry” had paid off – and continues to do so. A sharp rise in arson attacks on asylum centres as well as rising rightwing agitation and violence once again occasion sombre warnings by politicians and pundits/journalists about the need to ensure that the “mood” of the population is kept in check. These public figures suggest that high numbers of refugees will “provoke” racist violence. To prevent violence, they advocate reducing the attractiveness of Germany for refugees by curtailing their rights. Political parties across the spectrum, media, and a significant percentage of citizens now demand deportations and the worsening of living conditions for all migrants – especially those not considered ‘proper’ refugees – in the name of Germany’s “welcome culture” for ‘real’ asylum seekers.

In both the smouldering remains of burned asylum homes and the political manoeuvres that follow, recent history looms large: a first batch of legislation to tighten German asylum law was passed in July, followed by another set of restrictive changes in October. A recent cabinet agreement was hailed by its advocates as the “harshest measures ever to limit the intake of refugees in Germany”. The measures particularly lash out against Roma people from the Balkans fleeing persistent racial discrimination and people escaping poverty. Several countries are newly reclassified as safe countries of origin, meaning people fleeing persecution there have very little chances of getting asylum in Germany. Lager control is tightening; incarceration and deportations increasingly facilitated.

Which path Germany will now follow might depend on which experiences become a reference point in current debates: The shadow of the 90s where violent racists succeeded in having asylum laws restricted or the history of self-organised refugee resistance. Those who decide to “help” need to start by listening to what refugees actually want. As The Voice activist Rex Osa has reiterated in a recent interview: What refugees demand is that the notion of “help” needs to include support for self-organisations of refugees and requires a double perspective: It is important to look at both reasons for people to flee and the racism they experience in Germany. It is only then that the status quo of self-congratulatory, paternalistic help can be transcended into political solidarity.

*The Inequality Series is a partnership with the Norwegian NGO, Students and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Through writing and dialogue, SAIH aims to raise awareness about the damaging use of stereotypical images in storytelling about the South. They are behind the Africa For Norway campaign and the popular videos Radi-Aid, Let’s Save Africa: Gone Wrong and Who wants to be a volunteer, seen by millions on YouTube.

For the third time, SAIH is organizing The Radiator Awards; on the 17th of November a Rusty Radiator Award is given to the worst fundraising video and a Golden Radiator Award is given to the best, most innovative fundraising video. You can vote on your favorite in each category here.

There’s more to Germany’s newfound “refugees welcome” culture

In June 2012, several refugees in the city of Würzburg stitched up their mouths to protest the lack of response to their political demands. Four demands have been at the core of the reinvigorated refugee movement ever since: Germany should abolish all Lagers (asylum centres in which the large majority of asylum seekers is housed, sometimes for years and decades, and often in isolated areas of the countryside), stop all deportations, abolish mandatory residence law (Residenzpflicht, a legal requirement for many refugees to only live and move within narrow district boundaries defined by the local foreigners’ office) and guarantee refugees the rights to work and study. The refugee movements’ long-standing critique of German asylum law and the discriminatory regulations governing the lives of many asylum seekers has gained visibility in recent years – yet in the past months, it has been eclipsed in the press and in public debate by the new idea of a German Willkommenskultur (“welcoming culture”). Heeding the history and present of refugee resistance in Germany has never been more crucial.

The recent refugee movements in Germany are part of the larger struggles of immigrants and minorities against racism in post-War Germany (e.g. the Ford strike in 1973, or the movement of Antifa Gençlik, founded in 1988). The history of racist violence, which came to head in the reunified Germany of the early 1990s, provides an important reference point for current debates. Increasing arson attacks on asylum centres, and racist pogroms in the 90s were cited as important justification for claims by politicians and the media that Germany had “reached capacity”. As a result, the German government severely restricted German asylum law in 1993.

Subsequently, self-organisations such as the Refugee Initiative Brandenburg brought their critique of isolation and human rights violations in German asylum homes to international attention. Other refugee organisations such as The Voice, Karawane and Refugee Emancipation developed strategies to reach out to refugees and invite them to join a political struggle for human rights that included speaking out against the total lack of education and work opportunities and denial of health care.

The revived refugee movement in 2012 was convinced that the master’s tools – individualised recourse to the courts and bureaucratic labyrinths – would never dismantle the master’s house. Refugees from all over Germany defied mandatory residence law, mobilised across Lagers and set out on a protest march from Southern Germany to the federal capital, insisting that they must be present and visible when decisions about their lives were made. They occupied public spaces, buildings, embassies, churches, trees and roofs in Berlin, Munich, Hamburg and Hannover and took to hunger strikes.

While the refugee movement eventually gained access to the mainstream media and shifted the discourse on migration, asylum and refugees slightly, this was recently swept away in the context of Europe’s “refugee crisis”. Starting this past summer, thousands of Germans offered their support to newly arrived migrants, and Germany was lauded in the international press as the ‘welcoming champion’. Yet, while the current flurry of activity offers conveniently de-politicised gestures of charity, it mostly ignored or sidelined refugees who were already self-organized. These groups have made clear that sincere support must engage in the politics that frame causes and experiences of the flight to Europe as well as the experiences refugees make here.

A colonial mask of silence is being put back on refugees through the charity dimension of the Willkommenskultur hype: It “prevents her/him from revealing those truths, which the white master wants ‘to turn away,’ ‘keep at distance’ at the margins, invisible and ‘quiet’”.

Rather than thanking Germany for its supposed generosity, the refugee movement in Germany has not tired to point out the past and present interconnectedness of prosperity and peace in Germany with poverty and war in other parts of the world: it scandalizes neocolonial resource extraction from the Global South and weapon exports, and generally calls for resistance against nationalist, racist and capitalist border regimes. It is uncomfortable for the majority of German society to be faced with people as (political) subjects who frame their demands from a postcolonial perspective, who speak out against rampant racism across German society, and who refuse to differentiate between socio-economic and political refugees by pointing out that economic questions are also political.

But the racist violence of the 1990s euphemised as “concerns of the citizenry” had paid off – and continues to do so. A sharp rise in arson attacks on asylum centres as well as rising rightwing agitation and violence once again occasion sombre warnings by politicians and pundits/journalists about the need to ensure that the “mood” of the population is kept in check. These public figures suggest that high numbers of refugees will “provoke” racist violence. To prevent violence, they advocate reducing the attractiveness of Germany for refugees by curtailing their rights. Political parties across the spectrum, media, and a significant percentage of citizens now demand deportations and the worsening of living conditions for all migrants – especially those not considered ‘proper’ refugees – in the name of Germany’s “welcome culture” for ‘real’ asylum seekers.

In both the smouldering remains of burned asylum homes and the political manoeuvres that follow, recent history looms large: a first batch of legislation to tighten German asylum law was passed in July, followed by another set of restrictive changes in October. A recent cabinet agreement was hailed by its advocates as the “harshest measures ever to limit the intake of refugees in Germany”. The measures particularly lash out against Roma people from the Balkans fleeing persistent racial discrimination and people escaping poverty. Several countries are newly reclassified as safe countries of origin, meaning people fleeing persecution there have very little chances of getting asylum in Germany. Lager control is tightening; incarceration and deportations increasingly facilitated.

Which path Germany will now follow might depend on which experiences become a reference point in current debates: The shadow of the 90s where violent racists succeeded in having asylum laws restricted or the history of self-organised refugee resistance. Those who decide to “help” need to start by listening to what refugees actually want. As The Voice activist Rex Osa has reiterated in a recent interview: What refugees demand is that the notion of “help” needs to include support for self-organisations of refugees and requires a double perspective: It is important to look at both reasons for people to flee and the racism they experience in Germany. It is only then that the status quo of self-congratulatory, paternalistic help can be transcended into political solidarity.

*The Inequality Series is a partnership with the Norwegian NGO, Students and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Through writing and dialogue, SAIH aims to raise awareness about the damaging use of stereotypical images in storytelling about the South. They are behind the Africa For Norway campaign and the popular videos Radi-Aid, Let’s Save Africa: Gone Wrong and Who wants to be a volunteer, seen by millions on YouTube.

For the third time, SAIH is organizing The Radiator Awards; on the 17th of November a Rusty Radiator Award is given to the worst fundraising video and a Golden Radiator Award is given to the best, most innovative fundraising video. You can vote on your favorite in each category here.

November 15, 2015

Asking for a friend

The big questions that animated our friend this week:

Facebook, thanks for the ‘Paris Safety Check.’ Can we have one for Baghdad, Beirut and Borno too?

Why is a public execution with a sword worse than an indiscriminate drone attack?

Why weren’t the recent suicide attacks in Baghdad and Beirut and Borno also an attack on humanity?

Are the #Parisattacks really the “worst peacetime attack in France since World War II,” as BBC reported?

Where are the good analyses on the pro-Igbo protests in Nigeria?

Did you know that Angolan transgender kuduru artist Titica won the “African Feather of the Year” award in South Africa for defending the rights of the LGBT community?

Is Yannick Bolasie’s Youtube channel (including clips documenting his arrival at the airport in Kinshasa and from the pitch in Bujumbura right after a 3-2 away win in a World Cup qualifier) the best thing ever?

Does anyone want to doggedly overthrow Paul Theroux’s supposedly self-amassed obstacles to write his biography? I mean, his “writing” is already enough?

Why is France24 taking advice from FW de Klerk (who as recently as 2012 still defended Apartheid) on immigration?

Why does Stellenbosch University (where English will become the only means of instruction) suddenly care about coloured Afrikaans speakers?

What if black people inverted South Africa’s township tours?

How can a non-musician discuss the future of music from anything other than a consumer point of view?

If you’re in San Diego for the annual meeting of the African Studies Association on Friday night, why not come to our book launch?

* That’s The Maribyrnong Six in the image above. BTW, we wish our friend Binyavanga Wainaina a speedy recovery.

The Stade de France–A History in Fragments

The French national team player Patrice Evra was dribbling up the pitch when the second bomb exploded. Two minutes earlier, the same thing had happened: a loud, resonating explosion heard by the 65,000 fans gathered to watch a friendly match between Germany and France. There was a wave of shouts – not quite a cheer, almost something like tens of thousands of people saying “whoa,” or “what”? – but no panic. People mostly seem to have thought it was a loud firework, perhaps a flare exploding in one of the tunnels. Football games are full of noise, after all, and sometimes explosions. So the game went on.

A stadium, these days, can be a curious bubble. Millions watch what happens there on television, but when you are inside you can easily be relatively cut off from the broader world. With tens of thousands of people in one place trying to tweet, text, instagram, you often can’t get cell service. So it was that those gathered in the stadium were among the few in Paris not to quickly find out what was going on. People rarely leave their seats during a football match – the pace is constant, you might miss one of the few goals – and the halls and entrances are mostly empty, a kind of buffer.

But around them, over the course of a little over a half hour, three suicide bombers set off bombs in and around the Stade de France. One was caught by security trying to enter the stadium, and set off his bomb as he backed away from the security checkpoint. Another detonated his bomb on a street that runs along one side of the stadium. It is named after Jules Rimet, a French World War I veteran who created the World Cup in the early twentieth century. A third bomber followed suit near a McDonald’s nearby. At least two people were killed in these attacks, and many more were injured.

When he heard the second explosion, Evra stopped for a minute, pondering the echoing sound. He looked up but – ever the footballer – had the presence of mind to pass the ball back to a teammate. A German player trotted after it, a little languidly. It was just a banal moment in the midst of a football match, but slightly off kilter, slowed down.

Evra was born in Senegal of a father from Guinea and mother from Cape Verde, but grew up in France. He is one of many players on the French national team of African descent. What was he thinking when he heard that explosion? Did he wonder, for a moment, whether continuing to play was a kind of madness? Or did he, and the other players, make the same decision that many are now saying we should: that in the face of horror the only thing to do is to keep playing, moving, living?

Watching it now – knowing all that we do about what happened Friday night in Paris – we can perhaps count it as one of the most surreal things to ever take place in this storied stadium, a place built nearly two decades ago specifically to house history.

July, 12, 1998

The Stade de France was built for the 1998 World Cup in France. It is in Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of the city famous for its ancient basilica and, more recently, as one of the banlieue regions often depicted primarily as sites of poverty, conflict with the police, and fertile ground for Islamist militancy.

When Smail Zidane, the father of the great French footballer Zinedine Zidane, had migrated to France in 1953 from Algeria, he worked for a time on a construction site in Saint-Denis. Without enough money to pay rent, he slept on the construction site. His son Zinedine grew up in Marseille, playing football in the plaza or the project where he lived. He didn’t like to head the ball, and when he was recruited to a football training academy at the age of thirteen had to be taught how to do it.

But in the final of the 1998 World Cup, Zidane used his head to score first one goal, then another, against the Brazilian team. His head won France its first ever World Cup, in the Stade de France. After he scored, he ran to the side of the pitch where his friends from his project in Marseille were in the stands. “We looked at each other,” he remembered later, with “a profound look, as vast as the football fields that we ran around on as kids.” Locked in an embrace for a long time with his friends, Zidane could smell “all those Marseille afternoons” as his friends shouted in his ear: “you’re the kid from the cité, our buddy who scored those two goals.” On the way back from the stadium – as deliriously happy French fans were flooding the streets for what would become several days of celebration, often chanting “Zidane President!” – he began thinking about “the murmurs that were rising up from the paths of the village where my father was born.”

Looking back on that evening a few weeks later, he described his goals as a testament to the possibility of Algeria and France reconciled: “it was the son of a Kabyle that offered up the victory, but it was France that became champion of the world. In one goal by one person, two cultures became one.”

The evening of the victory, after they had collected their trophy and shaken hands and had their picture taken, even after many of the fans had left, players from the French team remained on the pitch at the Stade de France, sitting, chatting, enjoying themselves almost like they were at a picnic on a Sunday afternoon.

November 13, 2015

Just before the half, France scored a goal against Germany, to the cheers of the crowd. The players still didn’t know what was going on, nor did the fans, at least most of them, at least not enough to create a panic. But President François Hollande, who was in attendance at the match, was quietly escorted out of the stadium, heading to out to speak to the press, and then to visit the sites of the carnage around Paris.

During the half, the team coaches learned the news, but decided not to tell the players. The match officials asked them to go out and play the second half nonetheless, having decided the safest thing was to keep the crowd in the stadium, which seemed relatively secure compared to the streets outside. A sanctuary.

France scored again. So it is that, drowning amidst the news from Paris, there can be this now insignificant headline: France defeats Germany in friendly match, 2-0.

October 6, 2001

It was a long-awaited and long-planned game at the Stade de France: a friendly international game between France and Algeria. It was layered, in fact over-burdened, with symbolism. Algeria had won its independence through a brutal war with France – one that had led to much violence in Paris too, including a brutal night of killings of Algerian demonstrators by French police in 1961, and terrorist bombings by various sides in the conflict. Algeria’s flag and anthem carry the history of its anti-colonial revolution. On the French team, meanwhile, the star was Zinedine Zidane, born of Algerian parents. Who would the many French fans of Algerian descent root for, the press wondered? Could football heal the wounds of history?

Seventy-nine minutes into the game, Algeria was losing 4-1 when Sofia Benlemmane, a dual Algerian-French citizen and women’s semi-professional football player, ran onto the pitch carrying an Algerian flag. Soon, others followed, and the pitch was overtaken by fans of the Algerian team, running, waving flags, laughing, chased here and there by security guards. The players were urged off the pitch, and the match was called off. But defender Lilian Thuram stayed. Born in Guadeloupe and raised in a project south of Paris, Thuram had famously scored two goals in the semi-final of the 1998 World Cup, becoming almost as famous as Zidane in the process. He had become increasingly politically active and vocal since then, speaking out against racism. His immediate reaction was to worry about how the pitch invasion would be used by the right in France. He grabbed one of those running with an Algerian flag and gave him a lecture. Don’t you realize, he told him, that they will use this against you? That it will seem to confirm everything they are saying about you: that you can’t truly be French?

A few days later French far right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen announced his candidacy for president outside the stadium, evoking the pitch invasion as clear proof that immigration was a menace to French society, that the integration of North African migrants had failed, and that France needed a leader like him to set back on the right course. He made it into the second round of the election, the best showing ever for a far-right politician, though was ultimately defeated by Jacques Chirac.

Since then, it has become a bit of a tradition that games between France and North African teams – Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria – involve some kind of controversy, usually the booing of the Marseillaise by fans rooting against France. There follows, inevitably, a round of laments about this. Sometimes players are taken to task, as they first were by Jean-Marie Le Pen during the 1996 European Cup, for not singing the Marseillaise before games. The Stade de France, in these moments, becomes the theatre for the problem of history unresolved, unending.

November 13, 2015

Only by the end of the second half did new spread among the crowd about what was happening. The killings at the Bataclan, on streets, on restaurants. Leaving the game, the players saw the news on television. One player, Antoine Griezmann, began trying to get news of his sister Maude, who he knew had gone to attend the concert that evening at the Bataclan club. He learned later that she had been able to escape.

But Lassana Diarra, who had played for most of the match, learned that his cousin Asta Diakité had been shot in one of the attacks on a restaurant. Diarra’s parents are from Mali, and he is a practicing Muslim. In a statement after the attacks, he explained that for him Diakité had been a “reference point, a source of support, a big sister,” and declared that in a “climate of terror” it was critical for “those who are representatives of our country and its diversity” to “speak up and stay united in the face of a horror that has neither color nor religion.” “Together,” he went on, “let us defend love, respect and peace.” In mourning, Diarra sought to channel some of the hopeful vision of France that has often been represented by the football team of which he is a part. Will he be heard?

Diarra probably learned about the death of his cousin while the team was still waiting at the Stade de France, where they spent many hours after the game. The Germans, told it would be unsafe to travel in busses, spent the night in the stadium.

The fans in the stadium, who by the end of the match had learned what was happening, had their own decisions to make. Should they leave the relative confinement, maybe even security, of the stadium in order to go out into a city that feels under siege? Already last year, during the Charlie Hebdo shootings, Parisians had been asked to stay home as the drama unfolded. Getting in and out of the stadium, through its tunnels, into the streets or onto the metro, is always a moment of potential danger. Authorities limited the exits and asked for calm.

Hélicoptère, pelouse envahie, scènes surréalistes. pic.twitter.com/PT5HXyKbDK

— Vincent Menichini (@v_menichini) November 13, 2015

Many of the entrances were closed off, and fans didn’t seem to know what to do. Many began walking, running, towards the pitch itself. But there was no general panic. Some of those who made it to the tunnels to the subway found solace and calm by singing the Marseillaise as they walked, slowly, pressed together, out towards the city and, further, home.

But others had a different reflex, which was to wait in a place that seemed safe: on the football pitch itself. Having left the stands they gathered there, waiting, checking phones, sharing news, talking, crying. That green rectangle of the Stade de France is the mythic site of the victory of 1998, of the pitch invasion of 2001. It is a patch of grass that millions of French have watched and fretted over year after year during games. But that night it served perhaps its greatest purpose: it became, for a time, a refuge.

November 13, 2015

Sex, beer, and Ndombolo: an interview with Fiston Mwanza Mujila

Tram 83 is Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s dazzling first novel. It follows an idealist writer named Lucien in an unnamed African mining town governed by global capitalism’s worst impulses. In the midst of a world reduced to chaos, survival and exploitation, Lucien tries to finish his grand oeuvre, a “stage-tale” entitled “The Africa of Possibility” and dedicated to Patrice Lumumba. The novel’s action occurs almost exclusively in a nightclub where child miners mix with striking students, rapacious Western businessmen, and women who are, in the words of one of the characters, “emancipated, democratic, and independent”. Mwanza’s vivid representation of this temple of intemperance and, more generally, of the human landscape in which Lucien must function, makes his novel a fascinating read that oscillates between gripping dystopia and humanist celebration.

Tram 83 was published in French in 2014 and has already won several literary prizes in Europe. It is now available in English, and translations in several other languages will appear soon. However, few Congolese writers works have been made available internationally; in fact the last time a Congolese novel was translated in English was 1993, when the DRC was still named Zaire.

Mwanza grew up in Lubumbashi, Southeastern Congo’s copper capital. Lubumbashi is a city pregnant with difficult histories, where the wounds of colonial segregation overlap with the more recent memories of secession, dramatic economic decline, and the violence of politicized ethnic identities. It is also a cultural crossroad where artists have taken advantage of the great distance that separates them from Kinshasa to go where their own imaginations took them. Not coincidently, the city also claims the photographer Sammy Baloji (who happens also to be Mwanza’s cousin) and the baroque singer Serge Kakudji, two artists whose work have a brilliance and freshness that resembles his own.

I recently talked to Mwanza on Skype in his home in Graz, Austria, where he has lived for several years. We discussed his novel, the recent protests in Kinshasa, and the new generation of Congolese musicians.

Your novel conjures the energy of the Congo, yet you wrote it from Austria. Was it a challenge to write a novel that is so infused with disorder, vitality, and convulsions while living in a country mostly known for – excuse the clichés – its draconian sense of order, quaint national costumes and picture-puzzle landscapes?

The Congo is like a cumbersome piece of luggage that you would carry everywhere. When you leave the country, you take the Congo with you. You become the Congo. You get interested in everything that is going on back home and you become more Congolese than the people there. The teeming reality of the country imprisons you when you’re home and you don’t have to define yourself. When you are abroad, you look at the country in a different way. You feel more Congolese and you feel you have to define your difference.

You are just back from a long tour in the United States. How was Tram 83 received there?

The reception of the book in the U.S. is not dissimilar to my experience in Austria. American or Austrian readers are obviously less familiar with francophone African literature than, say, readers in France or Belgium. This is actually quite refreshing, because people actually look at your text, at what you are saying, at your aesthetic, at your language. While in France, people are often interested in genealogies – “you write like so and so” –, which reduces the book to a form of ethnological reading.

I also think there is a genuine interest in the DRC in the U.S. It might be because somehow the country has been at the center of the world since the Berlin conference. And even people who don’t know much about the Congo will still at least be able to relate to a few images. They will remember Mobutu, the Rumble in the Jungle, or some of our musicians.

Tram 83 takes place in a fictional city that often evokes Kinshasa, Mbuji-Mayi or Lubumbashi. Yet, you situate that city in an unnamed African country, which is explicitly not the DRC. Why did you choose to employ geographical ambiguity?

It is impossible to write about the Congo. It is impossible because it is a country that still doesn’t exist. It does not exist as a place of rights, as a normal state. It is also impossible to write about the violence in the Congo and its millions of victims. The only way you can write about this is by embracing extremes, exuberance, and poetry. And my novel is like a long poem.

I wanted Tram to be able to represent a form of exploitation and neocolonialism that happens throughout Africa, not just in the Congo. Yet, the mining cities of Mbuji-Mayi and Lubumbashi, and their transformation since the liberalization of mining, were indeed my most direct sources of inspiration.

Some reviews of the novel have missed its humanist dimension, which was crucial for me. The use of children in the mines, the women who prostitute themselves in the mines, the new slavery of the mines, I did not invent it. Even you or me, we can go to a place like Mbuji-Mayi today, rent a concession, hire ten miners and pay them in Monopoly money. The novel contributes to the understanding of these new wretched of the earth.

Tram 83 does not only conjure the mining worlds of Central and Southeastern Congo. It is also an unforgettable portrait of the larger-than-life universe of Congolese nightlife, and notably of Kinshasa’s bar scene. The nightclub of your novel is a real pandemonium, a place where sexual exploitation coexists with hedonism, artistic creativity, and the emergence of new ways of making society.

Do you think Congolese politics can be reinvented in bars and nightclubs?

Politics is already happening in these places. Everybody knows that the most important decisions in the Congo are made at night, and not in official buildings. In my novel, people are going to the nightclub to talk about everything. The place becomes life itself, as well as its own country. It is a place that is both cruel and hopeful, where someone can be pimping young women while being the most kind-hearted person. You have people like that in the Congo too. And change also often comes from these very contradictions.

Towards the end of the novel, the patrons of the bar – the students, the miners, the prostitutes, the profit-seeking tourists – all come together and nearly succeed in overthrowing the dictatorial dissident general who rules over the city-state.

It is difficult not to notice the resonances with the recent mobilization in Kinshasa against the extension of Joseph Kabila’s presidency beyond its constitutional end date in 2016. What do you expect for the future of the Congo?

I am actually rather optimistic. The protests of January show a change of consciousness among the country’s youth. Despite the violent repression that followed the protests, I think lot of hope comes from a new general awareness that the youth created by taking the streets. Chaos is a possibility, but it will not turn into a civil war. People feel that they have been deceived, but they still want change. And they want to participate in the construction of a legitimate state based on the rule of law. There is a lot of hope, but it also feels as if we were at the eve of a battle, a battle that could be the last one. Next year will be decisive for the country. People are mobilized and I think the government will fold.

What is also happening, both in the Congo and in the diaspora, is a movement away from the world of beer and music that I describe in the novel and that has kept the Congolese youth away from the important questions. The boycott among the Congolese diaspora in Europe against Congolese musicians who have supported the current regime is part of that movement.

What is your view of the music scene in Kinshasa today? The sonic environment of your novel includes jazz and rumba extensively, but not contemporary Congolese so much. I think you only allude once in passing to JB Mpiana’s horse dance.

I listen to everything, from Grand Kallé to Fally Ipupa, and from King Kester Emeneya to Koffi Olomidé. But, in my opinion, there has been a decline in Congolese music that started at the time of Mobutu’s so-called democratization in the 1990s. There was a rupture with the era of the Francos, Rochereaus and Papa Wembas of Viva La Musica, when music was a serious business. Paradoxically, the democratization process introduced the cult of personality in Congolese music. Before the 1990s, what was important was the orchestra more than individual musicians: Empire Bakuba with Pepe Kallé, OK Jazz with Franco, Afrisa with Rochereau, Viva la Musice with Wemba, or Zaiko Langa Langa. Each of these orchestras had its own identity and worked as an institution. Today, there is an over-commercialization of music that has had a very negative impact on its quality.

But don’t you think there are interesting things happening in the new generation? For example, Fabregas’ recent hit “Ya Mado.” The song is basically a quintessential emblem of Congolese popular culture: it warns the youth about the dangers of HIV-AIDS while launching one of the most sexually explicit dance moves of the year. In a way, the song is a good description of the constrained moral and social space in which the women of your novel are evolving.

I think there are interesting things coming out of the new generation of musicians. Today’s music is very much like the country itself and its attempts to recover after years of political crises. There are weaknesses, but also reasons for hope. Next to songs of poor quality, you will also find real nuggets of gold. You only have to dig. You will not be disappointed. One among others to look at is Ferré Gola. I consider him Pepe Kallé’s heir.

Fabregras, on the other hand, responds mainly to the market. He is giving consumers the type of dance moves they expect. He has the spirit of an animateur, with the culture of the hit single. He is thinking about how to get people to the dance-floor. And throwing in suggestive choreography will always do the trick. Yet, I don’t think that people will remember this song in five years, because there is nothing new in the lyrics. We are very far from the 1980s and 1990s when musicians were contributing powerful songs like Stervos Niarcos’ “Kinshasa-Brazza” or Dindo Yogo’s “Mokili echanger.” The lyrics of these songs helped people develop a sense of their collective history. This is the kind of cultural mapping that I am trying to emulate in my writing.

The land grabs in Africa you don’t hear about

In the ongoing global debate about income and wealth inequality, a little known fact with particular relevance for Africa and with far reaching consequences has flown under the radar: land in Africa, which historically has been available to many, is increasingly becoming concentrated in the hands of the few.

More than half of all those living on the continent derive a livelihood from land through agriculture. In some countries like Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia, the percentage of people depending on the land exceeds 70 percent. Most of these people tend to be poor, growing just what they need and selling what little surplus remains.

The last couple of years have seen an increase in the number of media reports exposing “land grabs” in Africa. These reports have tended to focus on transactions involving Chinese or Middle-Eastern companies. For instance, the Guardian carried a widely shared story in 2013 on the proposed leasing of 1,500 square kilometers of land bordering the Serengeti National Park to a Dubai-based hunting and safari company. The deal would deprive thousands of Maasai of valuable grazing land for their cattle. Two years prior, the Guardian ran an extensive story on China’s Africa land grab.

While there is little doubt that Chinese and Arab interests are procuring land in Africa, a careful review of the evidence suggests that the biggest perpetrators are much more insidious. In a highly insightful book titled The Great African Land Grab?, Lorenzo Cotula of the International Institute for Environment and Development has marshaled the best available evidence on the scale and geography of the problem. Given that most transactions involving land take place behind a veil of opacity, credible continent-wide estimates of scale are hard to come by. Mr. Cotula instead chooses to focus on a handful of countries (Ethiopia, Liberia, Mozambique, Nigeria and Sudan) where systematic national land inventories have been conducted. In these five countries, the evidence shows that about 10 million hectares of land, roughly the size of Iceland, has been acquired between 2004 and 2009. Contrary to media accounts and widely held perceptions, it is well-connected urban nationals (such as civil servants, business people and politicians) who have grabbed the majority of this land in rural areas.

For instance, Nigerians acquired 97% of almost 1 million hectares of land between 2004 and 2009. In Sudan, Mozambique and Ethiopia the percentages acquired by locals were respectively 78%, 53% and 49%. A study based on a 2010 survey of land acquisitions in Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger found that over 95% of the investors in land deals were locals. One of the reasons why land deals involving locals go unreported in the media is that individually they tend to be small, about 85 hectares on average, but cover lots of land in the aggregate given the number of transactions.

A second set of culprits, also flying underneath the media radar and unbeknownst to many land rights campaigners in the West, are actually Western-based companies. A study reviewed in Mr. Cotula’s book showed that about half of all the land acquired in Africa between 2005 and 2011 was done by Western companies. European companies often lead the way – a situation that brings back bitter memories of colonial era land grabs. The same study showed that companies based in the United Kingdom, the United States and Norway were respectively the 1st, 2nd and 4th biggest external land grabbers in Africa.

Whereas the land grabbers of yore were mainly interested in plantation agriculture, the current generation is a diverse bunch. About 60% of the land acquired is for growing crops for biofuels to meet increasing energy demand in the West. Some of the land is used to plant trees to take advantage of carbon credit schemes. Norwegian companies are in the lead here having large tree plantations in Mozambique, Tanzania and South Sudan. Hedge funds are also involved, channelling money from Western pension funds, endowments and wealthy individuals into land deals hoping to cash in on any future rises in the price of land.

Ironically, the African middle class is acquiring land using the same methods and tactics perfected during the colonial era. Prior to colonization, local people laid claim to land using complex customary systems that had developed over centuries. The role of traditional authorities was to keep a record of different subjects’ land claims and to resolve any land conflicts that arose. The onset of colonialism had a profound impact on this system. For one thing, the colonial administrators elevated the position of traditional authorities vis-à-vis subjects and reinterpreted customary law so that all land decisions resided with the chief. All someone had to do when acquiring land was to deal with the chief – cutting out the original occupants of the land from the decision-making process. According to Cotula, the same modus operandi has sadly continued today, as people with money create alliances with local leaders in order to seize land.

Naturally, the impact on people whose land is taken is devastating. Families have lost land to farm on and land for cattle grazing. Sometimes they’ve lost complete access to water resources. What’s most tragic is that the urban elite often acquire land not to make meaningful investments, but for purposes of conspicuous consumption or to speculate on land prices. Western companies who acquire land rarely even use it.

So what can be done? First, we need increased transparency around land transactions in Africa. As things stand today, it is difficult to know who owns what in most countries. For instance, land policy in Zambia is still formulated on the basis of a land audit performed in the early 1990s (Cotula thinks this is no accident, as out of date data favours the land grabbing elite). Second, there is a need for African countries to reform colonial era titling systems to incorporate the claims of customary “title deed” holders. Lastly, the World Bank has recommended the levying of an annual land tax. Such a tax has the potential to raise money to compensate those whose lives are disrupted. The tax can also ensure that wasteful activities such as conspicuous consumption and land speculation are kept to a minimum (although the irony seems to be lost on the World Bank that they too have been involved in land grabs in Africa).

The last decade or two has seen millions of the rural poor losing their claim rights to land. The debate on inequality in Africa needs to be rooted in this reality if it is to have any relevance at all.

*The Inequality Series is a partnership with the Norwegian NGO, Students and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Through writing and dialogue, SAIH aims to raise awareness about the damaging use of stereotypical images in storytelling about the South. They are behind the Africa For Norway campaign and the popular videos Radi-Aid, Let’s Save Africa: Gone Wrong and Who wants to be a volunteer, seen by millions on YouTube.

For the third time, SAIH is organizing The Radiator Awards; on the 17th of November a Rusty Radiator Award is given to the worst fundraising video and a Golden Radiator Award is given to the best, most innovative fundraising video. You can vote on your favorite in each category here.

November 12, 2015

Africa is a Country will join the Pan African Space Station in New York City for the next 3 days

The Pan African Space Station (PASS) is an online music radio station and pop-up studio project of Chimurenga, a Cape Town-based platform founded by Ntone Edjabe in 2002. This Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Africa is a Country will be presenting three panels at PASS’ library-of-people installation at the Performa 15 Hub in New York City. Alongside a host of talented artists, writers, and intellectuals, we are happy to be part of the multi-media and cross-disciplinary event, and to be able to invite friends and colleagues to present on various aspects related to contemporary African culture and current affairs that are covered and recurrent on this site.

The three panels, curated by AIAC managing editor, Africa is a Radio host, and music section editor, Boima Tucker, are:

Friday 13th Nov. (3pm): Block The Road: The Sound of Afrosoca

An exploration of the recent explosion of cross-Atlantic exchange between Caribbean and African musicians, with Rum N’ Lime Radio co-hosts – Queens-based writer and academic Rishi Nath, and DJ, producer, and Trinidadian Soca ambassador DLife.

Saturday 14th Nov. (4pm): Adrift: A soundtrack for migration

A current and former member of the Brooklyn DJ collective Dutty Artz, DJ Ushka (Thanu Yakupitiyage) and Lamin Fofana, will talk about Fofana’s recent EP as a jump-off point to discuss migration — from what the Western media has dubbed a European “migrant crisis” stemming from Africa and Syria — to other examples of being “adrift.” The two will draw on there personal experiences as immigrants to the U.S from Sri Lanka and Sierra Leone respectively to discuss how they’ve incorporated heavy themes of (im)migration into their work as musicians and activists. The hour will feature both Ushka and Lamin’s musical selections as a soundtrack to being adrift – in terms of bureacracies, physical space and geopolitically.

Sunday 15th Nov. (4pm): Seeing voices: Reflections on African photographic portraiture

Zachary Rosen moderates a discussion between guests Awam Amkpa, a professor of cultural analysis at NYU and curator of the photography exhibition Africa: See you, see me, and Delphine Fawundu, a Brooklyn-based photographer. In her work she focuses on identities through cultural expression; incorporating themes of social justice, music and history.

Visit the PASS blog and/or 15.performa-arts.org for more info on the entire event. If you can’t make it to the Performa 15 Hub, be sure to tune in on the Pan Africa Space Station feed! Live streaming takes place from November 11-15th 3-8pm (NY time).

Africa is a Country will join the Pan African Space Station in NY!

The Pan African Space Station (PASS) is an online music radio station and pop-up studio project of Chimurenga, a Cape Town-based platform founded by Ntone Edjabe in 2002. This Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Africa is a Country will be presenting three panels at PASS’ library-of-people installation at the Performa 15 Hub in New York City. Alongside a host of talented artists, writers, and intellectuals, we are happy to be part of the multi-media and cross-disciplinary event, and to be able to invite friends and colleagues to present on various aspects related to contemporary African culture and current affairs that are covered and recurrent on this site.

The three panels, curated by AIAC managing editor, Africa is a Radio host, and music section editor, Boima Tucker, are:

Friday 13th Nov. (3pm): Block The Road: The Sound of Afrosoca

An exploration of the recent explosion of cross-Atlantic exchange between Caribbean and African musicians, with Rum N’ Lime Radio co-hosts – Queens-based writer and academic Rishi Nath, and DJ, producer, and Trinidadian Soca ambassador DLife.

Saturday 14th Nov. (4pm): Adrift: A soundtrack for migration

A current and former member of the Brooklyn DJ collective Dutty Artz, DJ Ushka (Thanu Yakupitiyage) and Lamin Fofana, will talk about Fofana’s recent EP as a jump-off point to discuss migration — from what the Western media has dubbed a European “migrant crisis” stemming from Africa and Syria — to other examples of being “adrift.” The two will draw on there personal experiences as immigrants to the U.S from Sri Lanka and Sierra Leone respectively to discuss how they’ve incorporated heavy themes of (im)migration into their work as musicians and activists. The hour will feature both Ushka and Lamin’s musical selections as a soundtrack to being adrift – in terms of bureacracies, physical space and geopolitically.

Sunday 15th Nov. (4pm): Seeing voices: Reflections on African photographic portraiture

Zachary Rosen moderates a discussion between guests Awam Amkpa, a professor of cultural analysis at NYU and curator of the photography exhibition Africa: See you, see me, and Delphine Fawundu, a Brooklyn-based photographer. In her work she focuses on identities through cultural expression; incorporating themes of social justice, music and history.

Visit the PASS blog and/or 15.performa-arts.org for more info on the entire event. If you can’t make it to the Performa 15 Hub, be sure to tune in on the Pan Africa Space Station feed! Live streaming takes place from November 11-15th 3-8pm (NY time).

Catching up with Noura Mint Seymali

In the dark, beautifully backlit confines of The Triple Door in Seattle, Noura Mint Seymali was holding court. A smallish woman from Mauritania, she ruled the stage with a fiery intensity that only the most powerful divas can maintain. She plucked her instrument, the ardine (a kind of harp that is somewhat similar to the kamele n’goni of Mali), with exact precision and sang with a voice so powerful it felt like it could pierce your skull. Along with her husband, Jeiche Ould Chighaly, whose psychedelic electric guitar riffs would put any Jimi Hendrix wannabe to shame, the young American drummer Matthew Tinari who’d been helping them book their tour and translating for the audience, and bassist Ousmane Touré who’d known her since she was a child, she tore the roof off this usually serene concert hall. It was an amazing experience, and in fact Seymali has been making big waves in the US since the release of her most recent album, Tzenni, on European label Glitterbeat. Backstage, we hung out a bit and talked about Mauritanian life and culture.

Seymali is the daughter of the famous and respected Mauritanian musician Seymali Ould Ahmed Vall who was responsible for modernizing much of Mauritanian music, for notating the Moorish traditions in sheet music, and for basically being the main ambassador of Mauritanian music to the West. It’s a position that his daughter now holds, and clearly believes in with a huge passion. Seymali learned from her stepmother as well, the beloved national singer Dimi Mint Abba (as well as many other family members).

The music that Noura Mint Seymali plays is rooted in the intensely complex classical music of Moorish North Africa. In Mauritania, there are five modes to the music and traditional artists move in a kind of “melodic orbit” through the modes during a performance. Each mode has multiple under-modes that are referred to as black or white. It’s a kind of coloring to the music that helps bend the mode in a certain direction, either black which lends violent tension, or the white, which lends a softness or elegance. The push and play between these helps transform each mode. “Our music is rich,” Jeiche says to me backstage, and it’s no exaggeration. You’d need a degree in ethnomusicology and years of study to really get at the heart of what is made to seem effortless.

The following is an interview with Noura Mint Seymali and Jeiche Ould Chighaly, conducted backstage at The Triple Door, with help from Matthew Tinari.

How is music transmitted in Mauritania? In families, from father to son, or what’s the process?

Noura Mint Seymali: There are women, griots, the ancient ones. It was these griots who made music in Mauritania, but now there are a lot of people making music who are not griots. Normally, though, in Mauritania, only the griots make this music. It’s made in families, like my own. I’m a griot, as was my father, his father, and twenty-one fathers before that.

21 generations?

Noura: Yes! Jeiche too is from a family of griots.

Is it common for a woman to be a griot?

Noura: Yes, there are female and male griots, especially female in Mauritania.

Jeiche Ould Chighaly: But before the 60s, women who were not griots couldn’t sing, only the griots could sing. Now, people who aren’t griots can sing.

The instrument you’re playing, the ardine, is it for griots only?

Noura: Until now, the ardine was for griots only. For the female griots only; there was another instrument for the men. The tidinit is for the men [Note: Jeiche’s guitar playing is directly based on the tidinit] and the ardine is for the women. It’s an ancient instrument.

Did you learn the ardine from your mother?

Noura: From my grand-mother. My father was a great musician. A professor of music and a composer as well. He wrote a lot of songs in Mauritania and he is very very well known there. He did many things. He wrote down the modes in Mauritanian music…

Matthew Tinari: He was explaining Moorish music, explaining all the instruments, the modes.

Noura: He explained the ardine, the tidinit… He wrote down in his book everything that’s in Mauritanian music.

What age did you start playing music?

Noura: I was nine or ten years old. I sang with my brothers, with my family.

Jeiche: Her brother is a composer and lives now in Spain. He married a Spanish woman. He’s a composer and he had this family band. He was the soloist, there was a brother who was the bass player, and his sister on the drums. It was a family band, but modern.

Noura: After that I went to school for my studies and was playing traditional music with my family. Then I started playing for weddings in traditional groups. Then in 2004 I started modernizing the music I played. We brought in the drums, the bass. That was difficult in Mauritania.

Jeiche: Mauritanians don’t like fusion music. They like the tradition more than any fusions. There are young people who like this, but there are all these older people who always want to be under the tents with the griots.

What’s the wedding music tradition in Mauritania?

Noura and Jeiche: It’s during the holidays of Tabaski (Eid el Adha) and Ramadan… When Ramadan is over there’s a big party. Since everyone’s tired because of Ramada, they want to make music. Plus there’s also the Tabaski holiday as well.

Are you guys busy with these weddings in Mauritania?

Jeiche: Yes, before we came here to the US for our tour, we were at a wedding. Noura was with us and people were just throwing money on us while we were trying to play !

Noura: But I don’t like playing weddings.

Jeiche: She doesn’t like weddings, but I love them. My father didn’t go to music school, he just came from the tradition. He died this year, he was 92 years old, and he was the one that taught my family music.

Matthew: His father had a lot of wisdom in his music.

Jeiche: He was a poet, he knew all about Mauritanian music and modes. Yobua was his name.

Noura, What kind of changes did you make to the tradition?

Noura: I added the bass and drums, I put in modern rhythms, but at the same time paired them with very traditional melodies and songs. Like the last song we played was a very modern rhythm but the song is traditional. The songs remain traditional, but we’ve reworked the rhythms.

Jeiche: The songs speak about the magic of Mauritania. About the prophet, about many things… Marriage, love, food.

Noura, do you write the songs in the group?

Noura: No, there are a lot of people who have written these songs from all over Mauritania.

Matthew: Maybe I’ll just explain a little bit… There’s a repertoire of poetry that all the singers draw on. Each griot takes a bit from here and a bit from there. It’s more like your rendering of poetry that’s in the public domain. It’s like rap or reggae where there’s all these sort of memes or lines out there and you’re drawing on them.

Do people recognize the lyrics? Like, “Oh, that comes from this poem…”

Jeiche: All Mauritanians know poetry, or most do. It’s popular. They know arabic poetry, but for us, we don’t sing arabic poetry, we sing hassani poetry. That’s the language that we speak.

Noura, what was a lesson you learned from your father?

Noura: Lots of things, lots of things… A lot of melodies. He said to sing with your stomach. You musn’t sing with your voice, you must sing with your stomach. If you sing with your stomach, you won’t get tired. Even if your voice gets tired, your chest won’t get tired.

Did you always want to play the ardine?

Noura: For me, the most important thing is to show the ardine. Because this is our tradition…

Jeiche [translating from Noura’s Arabic]: She’d like Mauritanians to know that what she’s doing is to ensure that Mauritania becomes better known. There are plenty of people that know nothing about Mauritania. She’s like a messenger of the music. Many people like this, but there are others that always want to stay in the tradition. Someone just sent her a Facebook message: “Noura, come back for my wedding, I can’t do my wedding unless you’re there!” But she’d rather be doing these kinds of concerts on tour, maybe leaving the weddings to her brothers and sisters.

To me, Mauritanian music kind of sounds like music in the Sahara. Are there ties between these traditions?

[heated discussion in Arabic]

Noura: No, in the Sahara there’s no music or culture of music.

Jeiche: They collect ideas from our music. There are no griot families in Saharan music.

I was thinking of the folks in Tinariwen or other Tuareg artists.

Jeiche: The Saharans or the Tuaregs, they take our music, but then it’s not at the level of our music.

Matthew: Mauritanian music has never really hit the international stage in the same way that Tuareg or other music really has. There’s a feeling that some of those cultures look to Mauritania for inspiration. There are elements of Mauritanian music that has been integrated into those styles over the years. But yet, Mauritanian music has never really broke. That’s a whole other conversation because it’s kind of political.

Jeiche: Our neighbors, they put out our music before we can get it out. You know, people like Abdallah of Tinariwen, when they see us they say, “Bravo, Bravo!” They know that this music comes from us. In the Sahara there are no griots. There are people who have music and if they listen to us for a bit, they take ideas. But it’s something different. There aren’t any of our modes, or the black and white modes.

What do the griots, especially the female griots, do in traditional society? Are they like journalists or politicians?

Jeiche: They don’t get into politics, but they take the stories and history of all the people in Mauritania. They know all these stories. Sometimes, we have these songs. If you love a girl and you can’t tell her that you love her, but it’s something that could be said with poetry. A griot could sing to this girl and tell her about you…

*This post appeared in its original form on the author’s Kithfolk Blog. The interview was originally conducted in French, Arabic, and English.

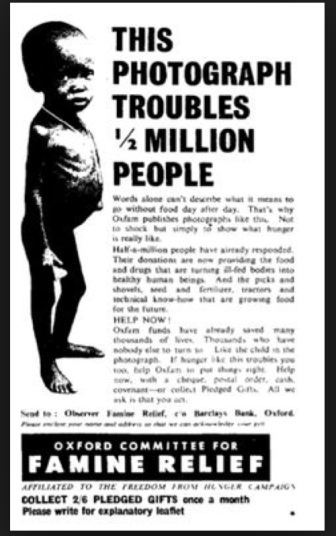

A short history of helping far-off peoples

In the past two centuries, as technologies of mass media have advanced, so too has our knowledge of the suffering of distant others. It is through this knowledge that the new ways of generating empathy underpinning the modern humanitarian movement came into being. But the desire to help others is difficult to disconnect from representations of their need.

Humanitarianism is a modern phenomenon, generally traced to the late-eighteenth century, when new forms of print media publicized the plight of far-off peoples. At heart it was about helping a distant stranger, rather than a friend or neighbour.

The abolition of slavery is usually credited as the first humanitarian campaign. During the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries western activists sought to create sympathy for enslaved peoples in the Caribbean through images and narratives that focused on both bodily and emotional pain. New ways of generating empathy for the suffering of distant strangers were created though lurid descriptions of torture and suffering. These were widely circulated due to the expansion of technologies such as the printing press, and reached new audiences due to expanded literacy. By focusing on the physical and emotional pain of slaves, humanitarian appeals highlighted the shared humanity of slaves. In doing so, these appeals created and extended empathy for distant strangers. Thus, humanitarianism has always been inseparable from its literary and visual representations.

However, anti-slavery appeals did not portray slaves as equal to western audiences. The images of the anti-slavery campaign instead showed slaves as helpless, supplicant and grateful to their Western liberators. In the quintessential anti-slavery image, an enslaved man asks the viewer, ‘am I not a man and a brother?’ He does so kneeling with clasped pleading hands. While attempting to overcome the most profound inequality created by early imperialism – the slave trade – anti-slavery campaigns also entrenched colonial hierarchies, portraying African people as helpless and white Westerners as their natural ‘saviors’.

Following the anti-slavery campaign, humanitarian appeals proliferated. From the mid-19th century onwards, a host of newly created humanitarian organizations vied with one and other to win the support of potential supporters and donors. To do so, they sought to show that the subjects of their appeals were the most worthy of humanitarian aid. While a few organizations – such as the newly established International Committee of the Red Cross – did this by highlighting the heroism and bravery of those in need of help (soldiers, in the case of the ICRC), for the most part, appeals echoed anti-slavery rhetoric, emphasizing the helplessness and humanity of victims of war, famine and poverty across the world. In addition to helplessness, mid-nineteenth century appeals emphasized new a criterion for sympathy: innocence.

Increasingly, humanitarian appeals focused on women and children, considered to be blameless, helpless and, unlike adult men, removed from the complexity of politics. Appeals for causes ranging from the Irish Famine in the 1840s to the South African War (highlighting the plight of the Boers) in 1899-1902 were almost identical: they emphasised the suffering of mothers and the starvation and sickness of children. The recurrent motifs of the modern humanitarian movement had begun to emerge. Over the course of the twentieth-century, through the rise of mass media and mass marketing, these persistent humanitarian tropes would be increasingly refined and standardized, and images of ‘innocent’ ‘helpless’ women – and, even more often, children – came to represent all moments of humanitarian crisis and forms of need.

The persistent use of mothers and children in humanitarian appeals has had two important effects. First, by depicting ‘starving children’ in humanitarian appeals, humanitarian organizations gave donors a sense of superiority over the people that they ‘saved’. They invited the white West to be ‘parents’ to people in need and, by extension, portrayed people and nations in need of assistance as ‘childlike’ – reinforcing colonial hierarchies and stereotypes.

Second, by depicting children, humanitarian organizations obscured the often-controversial politics of aid. Both now and in the past, humanitarian emergencies often emerge in the context of military conflict or political corruption. By presenting images of children – isolated from adult community members – humanitarian organizations distance the need for aid from the conditions that produce it. Donors feel as if they are giving to ‘innocent children’ rather than politically suspect adults. This approach has not only led to scenarios in which aid exacerbates conflict or props up bad leadership. It also – just as problematically – creates an ideal of ‘non-political’ humanitarianism and the recipients of aid as devoid of political ideals and agency. Three instances of extreme humanitarian crises from the twentieth century – the Russian famine of 1921, the Biafra-Nigeria War or 1967-70, and the Ethiopian famine during 1983-85 – illustrate some of the problematic effects of humanitarian appeals.

Oxfam 1995 aid campaign

In 1921, a mass famine swept Soviet Russia, endangering the lives of 10 million people. Western aid agencies, such as the newly founded Save the Children Fund, realized that if they were to raise money for Russian citizens that they would have to overcome significant anti-Communist hostility from potential European and American donors. Just a few years prior, the Communist government had seized power in Russia and created an international outcry. As they withdrew from the allied effort in the First World War, Russia issued anti-capitalist propaganda, and amongst other atrocities, executed the popular Russian royal family.

Humanitarian organizers in the West knew that if they were going to create sympathy for Russian famine victims, they would need to obscure the political context of a famine taking place under Soviet rule. To do so, humanitarian appeals depicted only children. Drawing on religious and romantic discourses of children’s innate value and innocence, appeals claimed that the young “could not be Bolsheviks” or “had no politics.”

In 1921, cameras were rare. Few relief workers carried them into the field. The Save the Children Fund thus relied on journalists for images of starving children, and promised large payments for “ideal” fundraising images. They drew up guidelines of what ideal images should look like: they should portray children – usually girls – under the age of 10 wearing few clothes in order to show their hunger, and should not contain adults. Mothers, it was later agreed, were perhaps acceptable, but certainly not men (who would be thought of as soldiers and Bolsheviks).

These images were an extraordinarily successful fundraising device, enabling a famine relief effort that fed three million children. But, the famine relief scheme also had unanticipated consequences. The Russian famine was not a natural phenomenon. It was caused by years of civil war, and the ineffective agricultural policies of the new Soviet government. By feeding Russian citizens, the West would enhance the legitimacy of the communist regime; a regime that would, ten years later, use famine as a weapon against its opponents in the Ukraine, and deny relief workers entry to assist in their relief. Even when aid was portrayed as non-political it could, of course, have far-reaching political consequences.

In 1967, the eastern area region of Nigeria attempted to secede – briefly becoming the independent state of Biafra, leading to a brutal and bloody civil war. Starvation was used as a weapon against the Biafran people, as Nigerian Federal troops blocked supply lines to the self-proclaimed independent state.

In a bid to secure international recognition for the secession, Biafran leaders attempted to highlight the political legitimacy of their cause. The Biafran people, they argued, had been systematically discriminated against in Nigeria, and the Nigerian state had itself only been created though the piecemeal amalgamation of culturally and ethnically distinct areas under British colonial rule in 1914. Yet these attempts to gain political legitimacy were widely unsuccessful: Western public opinion was initially unconcerned, while the British and American governments continued to support Nigerian federal forces with shipments of arms.

It was not until mid-1968, when the news reports of British journalist Fredrick Forsyth beamed images of starving Biafran children onto the television screens of millions of viewers that the Biafran cause captured the international imagination. As Forsyth himself explained, “people who couldn’t fathom the political complexities of the war could easily grasp the wrong in a picture of a child dying of starvation.” In an era when many homes were newly equipped with televisions, Western audiences were forced to confront the suffering of “Biafran babies” in their own living rooms. These images of staving children worked both to simplify and “humanize” the conflict for a Western audience, and aid organizations such as the Oxfam and the newly established Médecins Sans Frontières drew unprecedented donations to deliver humanitarian supplies behind the Nigerian blockade.

Undoubtedly, humanitarian intervention spurred by images of starving Biafra children saved lives. Yet, it has also been argued that humanitarian intervention served to prolong the Biafra-Nigeria war ultimately leading to further loss of life. The Biafran famine appeal also had long-term cultural implications. In the late-1960s, an era in which may African states had become newly independent, Biafran famine appeals reduced the complexities of post-colonial politics to the image of a helpless, starving child, whose future rested not upon political self-determination, but Western aid.

Fast forward to the 1983-1985 Ethiopian famine. Then familiar humanitarian tropes were deployed once again to create sympathy for victims. A host of NGOs (and pop stars) publicized the plight of Ethiopian children, who, like the Russian and Biafran famine victims who had come before them, were the subjects of graphic photographs and lingering camera shots focusing on the pain and physical deformities that chronic hunger produced. In a series of near-identical humanitarian appeals and news reports cameras panned from helpless, hungry mothers and children to wide-lens shots which emphasized the scale of the crises (among them the song and video for Band Aid – the first of a now familiar genre of charity music appeals satirized by Africa for Norway). In these appeals, victims of hunger were reduced to a “mass of humanity” as viewers were told repeatedly that the famine was on a “biblical” scale. As in Russia and Biafra, the causes and context of the famine were obscured in order to create a compelling humanitarian narrative: Ethiopians were hungry, and Europeans could “save” them by making a simple donation.

Humanitarian appeals that obscure the complex political causes of disasters do not only undermine the agency and individuality of their victims. As Alex de Waal argues in his book Famine Crimes these humanitarian appeals – by presenting famines as unavoidable emergencies that can only be resolved through Western aid – diminish the responsibility of governments to meet the needs of their citizens. In the case of Ethiopia, de Waal argues, humanitarian appeals and humanitarian aid ultimately absolved the government of responsibility for the famine, thereby strengthening the authoritarian Mengistu regime and disempowering Ethiopian famine victims.

The nature of humanitarian appeals has had profound effects. In the short term images of suffering children have captured the imagination of the western public and allowed for interventions that have saved lives in moments of crisis. Yet, in the longer term, humanitarian images have obscured the causes and political complexities of disasters, and undermined the agency of their victims – both symbolically and practically. They have perpetuated hierarchical relationships between the Global South and the West. By masking the political causes of humanitarian crises, instead offering a simplified narrative in which victims of hunger as ‘saved’ by one off interventions by Western aid agencies – sustainable, long term solutions to hunger and poverty remain out of reach. It remains to be seen if we can strive towards a system that asks tough questions as opposed to presenting simplified rescue solutions, but in 2015 we should not be content with reproduction of the images and inequalities of the past.

*The Inequality Series is a partnership with the Norwegian NGO, Students and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Through writing and dialogue, SAIH aims to raise awareness about the damaging use of stereotypical images in storytelling about the South. They are behind the Africa For Norway campaign and the popular videos Radi-Aid, Let’s Save Africa: Gone Wrong and Who wants to be a volunteer, seen by millions on YouTube.

For the third time, SAIH is organizing The Radiator Awards; on the 17th of November a Rusty Radiator Award is given to the worst fundraising video and a Golden Radiator Award is given to the best, most innovative fundraising video. You can vote on your favorite in each category here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers