Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 320

November 23, 2015

Refugees need freedom, not handouts

للغة العربية اضغط هنا*

As a refugee rights activist and an immigrant who has experienced all of the trials and tribulations faced by those seeking asylum in Europe, my head is full of thoughts and questions I’d like to share.

Do we see the repetitive media messages, particularly those delivered by the German Chancellor, materialize on the ground? In reference to efforts for integration, Angela Merkel proclaimed, “We have done it.” But how accurate is this statement when, in many cities across the country, we see xenophobic demonstrations targeting Muslims and foreigners in general.

Does the burning of more than one hundred future resettlement shelters reflect a culture of integration and welcoming?

When the German parliament issues new laws that restrict or prohibit freedom of movement for refugees, thus forcing them to remain in deteriorating asylum camps, or the distribution of canned food rather than offering a stipend; does that reflect a culture of integration and welcoming?

German society, propelled by the political elite, spread their culture of integration and welcoming by making refugees feel victimized and dependent. All the while forgetting that they are contributing to the instability elsewhere in the world that has forced so many to flee. They forget that German companies continue to export arms internationally, including to active conflict zones. Take for example the arms deal with Saudi Arabia, currently leading the offensive in Yemen under the guise of legitimate support.

In order to stop the flow of African refugees, Germany has chosen to incentivize dictatorships (Sudan, Eritrea, South Sudan) to monitor their borders. This has been accomplished in part by generous financial support and the establishment of refugee camps outside of Europe.

With these new restrictions, the so-called culture of integration and welcoming has failed miserably in Germany. This becomes particularly clear if we consider the results: The refugee protest movements, which began in 2012, continue today. Refugees remain confined within German borders – a decision that was approved by the German parliament at the beginning of 2015. This confirms the death of the culture of welcoming and integration in Germany.

What is required to solve these problems goes beyond the scope of law. Great effort must be put forth to end war, and cease the support to dictatorships propped up by European powers.

As immigrants, refugees and citizens, we must fight together to stop the rampant racism created and sustained by the government and their policies of forced isolation.

Refugees must not be seen as victims or burdens, dependent and in need of help. There should be political solidarity. Refugees do not need food and drink in so much as they need freedom, dignity, and safety from xenophobic attacks. Finally, they need protection from the laws that restrict their movements and remove their freedoms. They live in authoritarian conditions in countries said to be democratic.

*The Inequality Series is a partnership with the Norwegian NGO, Students and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Through writing and dialogue, SAIH aims to raise awareness about the damaging use of stereotypical images in storytelling about the South. They are behind the Africa For Norway campaign and the popular videos Radi-Aid , Let’s Save Africa: Gone Wrong and Who wants to be a volunteer , seen by millions on YouTube.

For the third time, SAIH recently organized The Radiator Awards ; a Rusty Radiator Award went to the worst fundraising video and a Golden Radiator Award to the best, most innovative fundraising video of the year. You can view both winners here .

November 20, 2015

Weekend Music Break – Black Consciousness Day Edition!

Happy Dia Nacional da Consciência Negra and Dia de Zumbi dos Palmares! For those of us who don’t know, today is Black Consciousness day in Brazil, a day marked by the anniversary of the death of Afro-Brazilian folk hero Zumbi dos Palmares. Zumbi was the leader of the 17th Century Quilombo community that at its height had a multi-ethnic make up of 20,000 inhabitants, and then was violently crushed by the Portuguese on this day in 1695.

More than 300 years after the death of Zumbi, addressing the situation of racial inequality in contemporary Brazil remains like the challenge of a jigzaw puzzle with missing pieces. If there’s any truth available it’s that that there are literally a hundred different perspectives on it, many of which have been covered on this site. So since this day is about the reflection on the contributions African descendants have made to the creation of the Brazilian nation, take a break to read up on our archives. And, enjoy this Afro-Brazilian themed weekend music break!

In related news, I’d like to take a minute to announce the beginning of a new online platform I’m launching called INTLBLK. And in conjunction with this special day in Brazil, it’s fitting that the first project to come through the pipeline is the debut single from the Afro-Brazilian, Bahia-rooted super group Ziminino, made up of Rico Bêis and Rafa Dias.

Check out the first single from Ziminino, Intermitência, below (with a remix from yours truly), and follow the updates from INTLBLK on our website (intlblk.com), Tumblr, Twitter, and Bandcamp.

November 19, 2015

Sharjah Biennale: Exploring the boundaries of the nation through art

2015 has been the year of art biennales that attempted to change the world – or at least make the art world have those difficult conversations it likes to avoid at its fancy gatherings. The biggest and the most talked about of these was, of course, the Venice Biennale, curated by superstar curator Okwui Enwezor, who made it a point to stress his desire to critique the politics of national identity, the exclusions that are inevitably tied to the creation of national histories, and capitalism itself as a prevalent, violent, and exclusionary force. Pavilions and events connected to the Venice Biennale were preoccupied with reflecting Enwezor’s overarching and ambitious critique, yet the flash and the elitism of the art world remained as much a part of Venice as in previous years; asked JJ Charlesworth on Artnet, “Could it be that in the partying and the networking, and all the talk of politics and capitalism, the real point for all these countries and non-countries is to be part of the new machinery of the global economic world order, of which art biennials have become the cultural window-dressing?” No matter how earnest Enwezor’s intentions may have been, art seems to be inevitably reeled in by that machinery, and the biennale has become the gutting table on which the artist – and all the striving that brought their work the attention of elite choice-makers – is eviscerated and displayed for the powerful buyer.

Given the pointedness of Charlesworth’s question, I wonder whether it is possible for exhibitions and biennales to extend an invitation to the global elite—who, after all, can financially support artists—and create spaces in which art and artists can challenge prevailing aesthetic, political, or social views? That is, can art remain a location for re-thinking, for both contemplation and action—and still ask questions that make us uncomfortable—in the era of the art fair and the biennale?

Earlier this year, I had the privilege of being invited to the Sharjah Biennale. Straight afterwards, I flew to Joburg, and whilst there, I saw a more modest exhibition curated by Athi Mongezeleli Joja; and just at the beginning of November, I went to Recontres de Bamako: Biennale of African Photography (more on that later this week). None of these were on the scale of Venice, and the partying was definitely on a lower scale, but these biennales and exhibitions revolved around some similar concerns to those that Enwezor may have hoped to get the art world to consider. The Sharjah Biennale invited a group of art writers to its “March Meetings”—a series of presentations, lectures, panel discussions, and site visits designed by the curatorial team to cultivate critical conversations about the issues significant to the shaping of that year’s biennale. This year, the questions circled around the idea of what constitutes the nation—real, ephemeral, imagined and material. What does it mean to create national identity and belonging in the twenty-first century, and what are the consequences? More specifically, what does it mean to be a nation—or create belonging within a bordered identity—in a time when the nation state, and identity politics that often accompany the nation seem more fragile than ever, more passé, more distrusted? Is it possible to establish nation and identity, considering impermanence, decay, change, and environmental forces as stark as they are in a desert landscape? What about the impossibility of controlling the shape of how others—those within, and those outside—may see us? Establishing nationhood is as precarious as high-school popularity contests: if those who are powerful and instrumental to whether others recognise our sovereignty do not acknowledge us, we will inevitably have difficulty making our way through the world. And those within our borders, too, may not recognise us as legitimate: it’s difficult to encourage a unified identity when those within find the disciplinary measures taken in order to shape our identity too painful to accept. That leads us to the crucial question: is nation and identity—as nationalists and proponents of identity politics often claim—a coat that can shelter the many colours of its inhabitants, or a punitive and corrupt veil that is constraining and injurious even to those contained within its boundaries?

These are dangerous questions to ask in fragile political situations, where nation-building is underway at a manic rate in not just symbolic but material terms (witness the interminable construction projects at every turn, the ceaseless clanking of metal and concrete, the wiry, desiccated figures of imported labourers eating their meals using pieces of cardboard for plates), whilst the question of what will sustain this nation (where will the water come from for this new green vista, sprouting in the desert? What will happen when the oil wealth runs out?) cannot be far from anyone’s mind. Perhaps mania helps avoid contemplation.

Thus, despite the lack of clear curatorial intention in the choice of works by Sharjah Biennale 2012 curator Eungie Joo, it was a delight to find several artworks that encouraged contemplation and thoughtful play. More than that, being in a location whose rising structures, irrigation systems, food preparation and toilet cleaning were dependent on visible (yet invisible) and precariously positioned migrant labour, juxtaposed by the presence of artworks that pointedly commented on the precarity of “civilisation” was disquieting and unsettling in the way that art should. Perhaps even more remarkable: that the Sharjah Art Foundation President Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, and the Al Qasimi family as a whole want to explore these ideas, even as they are positioned only twenty minutes from the Gulf state that unthinkingly builds to forget precarity.

The “March Meetings” workshops took place in May this year, due to some logistical issues. Writers and several artists were invited to the sessions, which began in the morning, and went on well into the afternoon. From the first session—which focused on Past Disquiet: an archival and documentary exhibition that excavates the history of The International Art Exhibition for Palestine (Beirut, 1978)—we were oriented towards thinking about the ways in which nationhood is formed collectively, through the recognition of neighbours and allies. That opening conversation between Kristine Khouri and Rasha Salti highlighted the significant role that art exhibitions—especially those outside the framework of museums and institutions— played in international anti-imperialist solidarity movements of the 1970s, bestowing value on particular struggles for nationhood—in this case, the contested conceptual borders of Palestine.

The second day of the meetings began with Maxim Gvinjia, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia (a former Soviet colony), and currently its Ambassador in the UAE, in conversation with Egyptian artist Hassan Khan. The Republic of Abkhazia is only recognised by seven other nations (and three of those seven are also not recognised by most “legitimate” nations). Gvinjia admitted—whilst speaking about the precarity of his position as an ambassador of a country that is not recognised—that he just got fired from the position of Foreign Minister: “I’m doing this Mickey Mouse job for so many years that I don’t see anything else.” And yet, duty remains: although it “was never [his] ambition to be a politician; it’s always been a job.” He then jokingly emphasised the close relationship between the work of representing a nation’s face and theatrical performance, revealing that he “always wanted to be a superstar or a rockstar; I was even in a hip hop band.” Khan then pressed Gvinjia, asking whether what he is doing isn’t borne out of conviction, whether it did not require more emotional involvement that he was willing to bare. Would he call himself a “nationalist”, ushering the populace of Abkhazia back in time to an imagined location—rather than to a physical place—a time and vision of imagined unity aided, perhaps, by the expulsion (or voluntary departure due to the 13-month-long war that began in August 1992, depending on whose point of view) of Georgians, who were the largest ethnic group in pre-war Abkhazia. Khan was adamant that states are problematic—built on exclusions that create disastrous conditions. He pointed that it took mass mobilisation (which he distinguished from a mindless mob in the throes of “hysteria”) in Egypt to oust Mubarak, standing firm in the face of opposition from his powerful allies in the West; for Khan, “total revolution” cannot happen in a “year or a moment”—it is an on-going thing that has to be negotiated and fought for. Gvinjia only conceded, “all states and governments are temporary; sometimes the state survives in name, but the government changes.” He repeated a truism that many recognised: people wanted revolution, and they got it, but now they didn’t know what to do. Nationalism, he, concluded, was the “fast food that people liked”.

We saw a film, “Lost Letters To Max”, created and directed by Eric Baudelaire. The film followed Maxim Gvinjia, and references to the letters written by the two men to each other. As a sort of continuing performance of his work as an ambassador, Gvinjia then held “office hours” in the auditorium of the March Meetings spaces. What does a conversation between an artist and an “Anambassador” reveal? Seated on a gilt chair behind a heavy, polished desk, flanked by two flags, the Anambassador took questions about how Abkhazia manages the day to day operations, including getting visas for citizens wishing to travel—which seemed to be one of the most annoying consequences of being a non-nation. Here, “He may host events, greet visitors, hold discussions and invite guests. The Anembassy is a performance (can it be anything else?); it is not official and it has no function in an operational sense. It will operate as a ritual that is both real (since Max was Foreign Minister) and a fiction, but a fiction meant in a very political sense: fiction as a territory of resistance for those who are given no space in the real.”

The next set of discussions addressed what the curator called “the state of the state within an increasingly fragmented context and time”; the most educative part of this was arts director of the International Academy of Art Palestine in Ramallah Khaled Hourani’s description of the two-year obstacle course he and his collaborators ran through in order to bring a Picasso to Palestine for the first time. Hourani described what it took to get Picasso’s “Buste de Femme” (which he jokingly said was a “rubbish” Picasso—some third-rate thing that the Netherlands allowed them to have after endless negotiations) to travel from the Van Abbe Museum in the Netherlands to the tiny International Academy of Art-Palestine in Ramallah. What was significant about this rubbish Picasso? That having it in Palestine, to allow Palestinians to be able to see a Picasso like any other people who would only complain about the museum’s entry price—this made a symbolic statement about Palestine’s nationhood. His narrative, and this exercise demonstrated the seminal role that particular artworks created by ubiquitously recognised artists—especially, perhaps, those European artists one associates immediately as a “thing” one must know about and see if one is interested in art—can play in publicising an occupied people’s struggle for recognition and normalcy. The impossibility of surmounting the obstacles would make any person give up, accept this denial of participation in ordinary things as part of occupation. One of the biggest hurdles Hourani and his collaborators faced was in getting the work insured; no insurance company usually associated with the transportation of artworks wanted to touch this one. Who did? A company that insures tuna fish—they accepted because, apparently, “it was easier to insure a Picasso than tuna.”

Transportation and checkpoints were another contentious issue: the painting cannot be exposed, yet at the checkpoint, the whole crate was required to be opened. When it arrived at Qalandia, in the no-man’s land between Israel and Palestine, where they could not see what was going on—no Palestinian guards could be there, and they could not contact the Israeli guards—they asked news media personnel and their cameras to act as guards. This odyssey eventually became a conceptual work, and a film, Picasso in Palestine, documenting the hurdles that Hourani—and Palestinians as a whole—face as they attempt to be recognised, to become a part of the world of normalcy and ordinariness. Tellingly, noted Hourani, at the Museum of Israel in Jerusalem, just 20km away, there are several Picassos—out of the view of most Palestinians. He added, with understated irony, “If we are an independent state, we wouldn’t care about getting Picasso in Palestine…[but] we are never mentioned when museums speak about showing work.” So by bringing some common artist’s work—and not even a beautiful work at that—at a more than ordinary cost (a quarter of a million dollars), one proves one’s existence, one’s right to enter that world of ordinary existence.

During the Present Future of Emancipation group discussion, the person who had, perhaps, taken some of the most dangerous actions in order to emancipate not only herself, but to help make way for other women, was the quietest in the group. This was Lala Rukh, artist and early feminist activist in Pakistan and founding member of the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) in Lahore, who was there with her young interlocutor, artist, writer and curator Mariah Lookman, representative of a new generation of women activists in Pakistan. There she was, in denim jeans and a t-shirt, at an energetic sixty-seven years, recounting anecdote after anecdote about what it was like to live under the Zia-ul-Huq regime’s violent, repressive, and censorious martial law, and what she and her women counterparts faced as they went out into the public sphere to demonstrate against Zia-ul-Haq’s Hadood ordinance and the Law of Evidence, both of which made it impossible for women to testify against abuse, because it was designed to question their competence to testify without having male witnesses to the crime. WAF was composed of women who had been working, as journalists, in theatre, as academics; their first demonstration was to make an outcry, at the airport, about the banning of the Pakistan Women’s Hockey team in 1981; another time, they had a public chaadar burning (about which there was a lot of disagreement, because WAF members had varying opinions about whether doing such a symbolically incendiary act would bring too much negative attention). Together with another organisation she belongs to, Simorgh collective, a women’s resource and publication centre, Lala Rukh also participated in carrying out studies into how schoolchildren were being impacted by changes to their curriculum, textbooks, the censorship enforced on popular media such as films and adverts. This study was eventually published: “Re-inventing Women: the portrayal of women in the media-the Zia years”. As she said on a recent interview on Zubaan,

The kids that have come out of that [post Zia-ul-Haq] education have actually been quite religious. I mean, we were secular people but our children are religious, because they’ve been through that education system. Although some things have changed and a lot of contradictory things are taking place now…On the one hand, you have globalization and exposure to all kinds of media but on the other side, you also have the Taliban types. So they’re somewhere in the middle and some do see that this kind of religious extremism is not acceptable. But if you end up in an argument with any of these kids, they will defend religion to death.

All the while, she remained an artist; her drawings and photographic works are considered to be among pioneering works in the South Asian minimalist tradition.

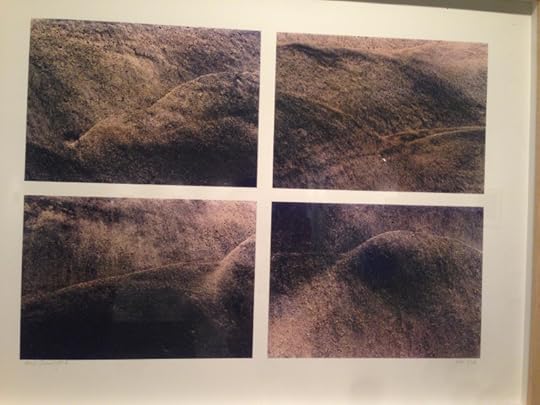

The restraint evident in her artwork is the very opposite of her voluminous energy, political narratives and activism. It is as if, trapped in that wiry body full of energetic outbursts is a centre of meditative beauty. Her paintings, which we got to see at the gallery at The Sharjah Art Museum, were small jewels of silver, grey, and black: invitations to come close, to contemplate stillness. “River in an Ocean” (mixed media on photographic paper), for instance, is a meditation on the disappearance of self into the vastness of oneness with a great and all-absorbing other. In one variation (1993), the path of the river through the landscape and its entry into the ocean is unmistakable: directed and full of silvery purpose; in another, earlier iteration (1992), the speckles of the river’s energy are already part of the sea water, glistening in moonlight coming through cloud cover. Here, Lala rukh lets the individual self of the river be lost in the great body of the ocean.

***

After these discussions, we finally had time to see the artists’ work, which were in several locations in the city, mostly within a walking distance or a short taxi ride. After a grueling day of talks and debates, two Egyptian art journalists and I walked in the late afternoon heat—temperatures were hitting the 40s—promptly getting lost, of course, looking for the main exhibition spaces. At times, I acted as the emissary, asking Indian shopkeepers for directions, and at others, it was my Egyptian colleagues, Dina Kabil, Head cultural section at Al Ahram Weekly, and poet and journalist Zein Alabedin Khairy, who asked (their dialect of Arabic and that spoken in the Emirates are too different for clear communication, but inevitably, there were Egyptians there, too, minding the shops and small restaurants) for the way to one of the main exhibition spaces in the Arts Area. We were told: follow the city wall: high, thick, with beautifully carved gateways (all locked), and we will come to an open doorway. We were sticky with heat and thirst. We got water and juice from a shop, and were rallied when the shop owner said, yes, just a little more. That is where people are taking their kids to play cricket. And indeed, I’d read that one artist had created a cricket pitch on the grounds (Gary Simmons’s “Across the Chalk Line”), intended for it to be a “real use” space. So we knew we must be close.

When we did finally find the opening in the city wall that led to the tranquillity of the collection of galleries—low, cool, modernist-minimalist buildings that were a colour that matched the sand, with some intricate iron fixtures that harkened back to Sharjah’s heritage—we wound around the maze of buildings, looking at the little maps given to us and the direction boards that appeared here and there, searching out the buildings containing the works that each of us first wanted to see. Of course, we made many mistakes, and walked into the “wrong” building many times more than the “correct” one, revealing works that sometimes left an impression, and at others, made us wonder why the curator had included it.

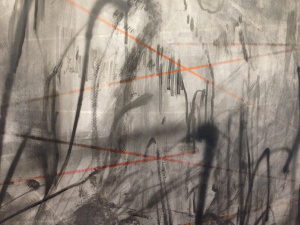

Whose work was at the top of my list? That of Ethiopian born artist Julie Mehretu. I waked in to one of the larger buildings, not realising that I’d finally found the right gallery, and spoke to the museum guard, asking about where her work might be. It turns out he was Nigerian; so we did a quick greeting based on our shared, imagined “African” identities. He walked me through a turn in the building, and there they were: enormous maps, complicated as cities riddled with our conscious actions, and the human unconscious driving that endless labour. Contemplating Mehretu’s massive canvases in real life is to be invited into journey that goes ever inward into the landscape of the subconscious. They are monumental in scale, with the power embodied by Richard Serra’s metal cenotaphs. But Mehretu’s paintings contain intricate, criss-cross of complex brushwork that draws the viewer closer, rather than demanding that we stand back and be imposed upon by the work. Close up, the scratches of paint on the canvas look like calligraphy marks, the black and amber hues layered over each other. But unlike calligraphy, which depends on creative leaps within a rule-based world, Mehretu’s brushwork draws attention to chaos, to how pointless human endeavour might be. Those marks could signify the disordered-orderedness of dense human habitation and human movement: we build material infrastructures that help us situate ourselves, we layer our lives with the solidity of our webs of social relationships, and then, we find them constraining and decide to do something completely other than what the structures ask us to do. In one of Mehretu’s canvasses, I saw the solid network of an established cityscape, dense and rich with generations of love and irritation. In another, I saw a flock taking off—a collective flight that one might think cannot happen without accident. Yet somehow, movement happens, despite the chaotic wingbeats.

Each time we stepped out of the air conditioning of a gallery and into the gravel crunch of pathways connecting the buildings, puzzling out which building this or the other artist’s work might be, the sun was setting progressively. So every few minutes, the light and the atmosphere surrounding the buildings shifted. The salt of the sea adjacent to the buildings was on our skins, and now we could taste the spray. The electric lights, housed in beautiful ironwork lamps lights came on, and everything around us was bathed in warm amber.

Then, as we stepped into Taro Shinoda’s contemplative installation, titled “Karesansui”, we heard the evening call to prayer: it was with this evocative and powerful call, inviting us into a state of mindfulness, that we went though the doorway to see the work. The museum guard responsible for minding this space was especially careful—making sure we stepped on permitted pathways, and did not disturb the sand. A rectangle of fine, white desert sand was circumscribed by a delineated border of rounded black pebbles; surrounding the black pebbles were pale grey pebbles on which visitors could walk. The first thing one notices as one steps in to this space is that there are two smallish conical indentations in the surface of the sand, undermining the perfect smoothness of the surface, but at the same time, drawing attention to perfection. Later, I learned that those conical indentations were ever expanding, because sand was trickling out progressively through 3.2 milimeter shutter holes into holding tanks one metre deep underneath. At one end of the sand rectangle, there was a small hut like structure – an engawa, or a shaded wooden platform—where one could, explained the guard, sit on the raised platform under the thatched roof of the hut, and contemplate. What to contemplate? Impermanence, of course.

Image via Tazuri

Later, Shinoda showed us the monitoring station built in the back—cameras revealing how the sand is—continuously and very, very slowly—trickling out through tiny openings under the bed of sand. He had to set this monitoring station up because at first, the sand kept clogging up the hole, and the process would stop. Shinoda’s artwork is meant to make the observer only have an elemental relationship to the object, and because of that, be moved to think on emptiness; being shown the engineering that went into the construction of a device was, perhaps, like seeing the Wizard of Oz’s backstage area. But instead of being demoralised by the fakery employed by a figure projecting power, here, I think that the two Egyptian arts writers and I were delighted and even more impressed. What made Shinoda come up with this? He and other artists, when they first came to visit the site, were taken on a trip into the desert. He’d never seen anything like it, he said: vast stretches of rolling dunes. This artwork was his response: the context of desert nations that are doing their best to build monuments both cultural and material to permanence. How did he make the sand in the pool so smooth? That problem posed real trouble for the perfectionist. He tried several methods, yet remained unsatisfied. Finally, someone told him about an Indian guest worker—a wizard who, using some sort of “magic” (a broom, actually), makes the sand perfectly smooth every two weeks. I asked, from several people, who this wizard was, but neither Shinoda nor others central to the Biennale knew his name.

On one of the last days, the artists, writers, journalists, and critics who had come for the March Meetings were taken to off-site exhibitions. First, to Egyptian artist Hassan Khan’s installation, which commented, wryly, on the attempt to construct nations on obsessive compulsive fantasies of symmetry and elegant design, and the disintegration of those dreams into unviable—and inelegant forms—of capitalism. His installation was exhibited in what was affectionately known as “The Flying Saucer”: itself an ode to capitalist dreams gone awry. It is a hexagonal building that was originally a French bakery, then a fried chicken shack that was eventually abandoned. On the roof, Khan set up two billboards with works by Andeel, an Egyptian cartoonist: an adult man is speaking on a mobile phone, whilst holding his young daughter’s hand. They walk in front of a ubiquitous cityscape (though one iconic skyscraper in the distance is unmistakably the Burj Khalifa in Dubai), under a blazing yellow sun and a blue sky pale with heat. The little girl is carrying a red monster—a toy that appears to be sluglike and immobile, but with a fierce set of dagger-like teeth set in a semi-circle in its gaping mouth. She is staring google-eyed at her father; her own, minimal-dash of a mouth shows her mute absorption of the scene. The adult human’s head and face has multiplied into three: He is a modern god of many heads, occupying as many positionalities as this location requires. Each speaks in a different language: Arabic, Urdu, and English. He asks, “Is there no respect at all?” in three languages. The answer, of course, to such a question is “No.”

Inside the Flying Saucer, panels of coloured glass filtered the heat and light of early summer, making it appear as though we were inside a jewelbox—though the plastic nature of these jewels was accentuated by the kitsch structure. An 8-minute video, The Slapper and The Cap of Invisibility, playing on loop featured a slapstick comedy—two men in a nonsensical argument, pointlessly going back and forth—containing tropes recognisable to any who watched Egyptian TV. Next to the video, two sculptures: “Dryscrapers And Buttshakers”. One, a sleek, minimal column of crystalline clarity (the “Dryscraper”), its cascade of smooth ridges reflecting a multitude of colours filtering through the plastic panels set over the glass windows surrounding the hexagonal building. The second sculpture (the “Buttshaker”) is less elegant and eye-catching; in fact, whilst we were drawn to the glimmering column, we avoided the other—a blob of clear plastic, roughly made of irregular discs gathered in a circle. It’s the shape that a child might give to a hastily drawn daisy with too many petals. Through these juxtaposed structures and the loud, cackling, arguing men in the adjacent video, Khan examines our desires for permanence and perfection, the cold structures that reflect our ideas of what the pinnacle of capitalism will appear to be, as well as the imperfect discards of capitalism. In between these two—the epitome and its antithesis—are confusion, anxiety, and irony.

After this, we set off to see Argentinian artist Adrián Villar Rojas’ installation at the Kalba Ice Factory, an hour’s bus ride through the desert and rolling mountains on perfectly constructed, gleaming black tarmac. Villar Rojas is known for his impressive, large-scale, site-specific sculptural installations that transform their immediate environments. At Kalba, his work didn’t disappoint: in a building that used to be an ice factory—again, in disuse—he used a mix of cement and local clay to make rectangular structures resembling high-rises and skyscrapers.

But these structures were destined to decay, even as we watched: inserted into the beautiful topography of coloured clay and cement were bits of date palms and still-identifiable husks of coconut. There were bird skulls and shells from the gulf of Oman nearby that his workers and collaborators had brought in. Some of the lower structures even had seeds scattered on them, which germinated when rain came through the open roof, producing sprouting plants—which inevitably died when the rains stopped, their plans unable to come to fruition. All these vegetable objects were strategically imbedded into the cement and clay, and as they decayed, they left lovely womb-like spaces, indentations, and pock-marks. In one moment, one sees the permanence and solidity of these towers and the beauty of their imposing monumentality; in the next, the vibrant, life-supporting platforms they provided ran out of sustainability, and all one sees are the ephemeral dreams and anxieties on which they were constructed.

Outside, the temperatures were at their noonday highest, even though it was not yet midsummer (a hotel employee told me that recently, a law asking construction forms to give workers a respite when the temperatures hit 50C was passed. But he wasn’t sure that this rule was followed, in reality. The temperatures reach their absolute impossible, and the radio announcers will declare that it’s pushing from 48C to 49 C—he made a insistent, shoving motion with his foot to accentuate his narrative—but it’s almost never declared to be 50C. How is this possible, he asks, rhetorically). I walked past small gatherings of workers, sitting in the back of small structures adjacent to the art spaces, built to shelter them and provide a space for them to cook meals. Some of their faces and bodies looked distinctly like a home that my family left behind some forty years prior: the date palms they sat under were different, but they could have been island fishermen under coconut palms, facing not the Gulf of Oman’s rising and falling tides, but those of the Indian Ocean. When I spoke to them, it turned out one of them is Sri Lankan. Of my family’s ethnic group (his coastal Sinhala sounds so different from what is spoken in my family that I had a little trouble keeping up). The other, a Tamil man from Tamil Nadu. They have been here, at this location, from the beginning of Villar Rojas’ project. They mention that a worker was injured in the making of Villar Rojas’ structures. But…they do not know what has happened to him. At home, the different clans to which these men belong (who also claim me, at times that are convenient or lucrative to them) are warring. Here, like all precarious groups, they are in it together—and perhaps this is a cliché. They have cooked a small meal and eaten—after helping prepare a sumptuous meal for us, waiting inside a café next to the art spaces: large langoustines and other delicacies, presented to us not by these men, but beautiful Filipina women and Filipino men.

On my last morning, I went on my own to see a closer off-site installation. To get to the warehouses at Port Khalid, one walks along the concrete border that guides the estuary of the Sharjah Creek flowing into the sea, and at a small signpost, one waits for a boat to take one to the other side. The boat arrives every fifteen minutes; I didn’t have to wait long on the dock before a small, open boat with a noisy motor pulled up. By that time, several people had lined up. We all boarded the boat, they nimbly and elegantly, despite its rocking in the wake of passing boats, and I with more fear. Those experienced to this routine sat immediately on the side that would not be hit by the heat of the sun when the boat turned towards the opposite shore. We paid out the equivalent of a dollar. After fifteen minutes, the boat reached the other shore, and I asked directions, vaguely describing something to do with art. No one knew. They had construction sites to hurry to. I saw a signpost—and followed it, staying on the shaded side of a row of date palms. Under one, two men were asleep. Eventually, after a ten-minute walk, I saw another signpost on the sun-side of the path. Large lorries kicked up dust on the road, and the other side was a quiet blaze. Even at 9:30 in the morning, crossing that 20 metres to the other side of the road meant sweat leapt out of every pore.

Two separate installations: the first, in a derelict building with an open front, where the wall had been either knocked down or never completed, an installation by the curator’s brother, Michael Joo: Locale Inscribed (Walking in the desert with Eisa towards the sun, looking down). In the adjacent room, where it was even more closed and stuffy because no air could circulate in that space, the inevitable blue-shirted, black trousered security guard sat on a plastic chair. He was mopping his face with a sopping cloth. I greeted him. He was from Nigeria, from the north of the country, near Kano. I looked at the installation, then asked if I could walk up the stairs near the guard’s station. Upstairs, more signs of a building once in use, though it was not clear for what. A deep layer of dust and sand covered everything, including the occasional broken chair or desk. Dirty prayer mats lined one room. I asked the guard: how is it for you, staying here hour after hour, as the heat becomes unbearable, with only a cloth to mop his face? His only answer: “It is our duty.”

The installation next door, Asuncion Molinos-Gordo’s WAM (World Agricultural Museum, which she originally made in Cairo in 2010, was housed in a smaller, closed building that was air-conditioned. Molinos-Gordo’s multifasceted installation could be mistaken for an educational museum for children, documenting the ways in which farmers first created seed banks, and how, in the late twentieth century, multinational companies enforced draconian copyrights of genetically modified seeds. But Molinos-Gordo positions what look like classroom displays—a little handmade-looking, a little educational-textbook-kitschy—without a direct critique, so one had to know the problematic ways in which multinationals, under the banner of “feeding the world”, have edged out and destroyed farmers and their livelihoods (and many farmers to suicide), and made the global population dependent on seed that cannot be grown without the chemicals produced by the same company. Wandering through the small, closed rooms (perhaps this building once served as offices for petty officials who minded the nearby warehouses’ business), the air conditioning was a welcome relief. The guard here was from Chennai, and was delighted that I’d visited his city, and that I thought well of it. He suffered visibly less than his Nigerian counterpart at the warehouse. I don’t think he and the other guard at the warehouse took turns, either, working shifts in one building, then the other, sharing their suffering. But during my visit, there was a respite, for a few minutes. We took a selfie.

The few conversations I had with construction workers, the coffee-makers, and the security guards were both deep and banal, with that level of intimacy one can only have with complete strangers from whom nothing is expected. Yet, there is the possibility of breaking a long-held emotional fast. In the end, I knew that the labour conditions here are not too different from that of labour conditions one might find for similar immigrant workers here in the US. There is no way to pretend that there are terrifying labour conditions in the Gulf states for certain pools of workers, but I know I must look at in a global context of near-indentured and indentured labour, especially in the industries of construction, agriculture, and maintenance (food preparation, cleaning). What is largely invisible to the consuming public in the US is highly visible here.

Shallow as my conversations were, what insight one can get from the security guard, the builder, the maintenance worker—each of whom live with and experience the Biennale’s artwork every day, but are rarely acknowledged as caretaker of a nation’s heritage, or, in Sharjah’s case, its attempt to position itself, opposite a sister-Emirate that has dedicated itself to self-construction through hyper-materialism, as a site of cultural and intellectual production. Some of these labourers helped actually co-create that art—maintaining the iconic smoothness of Shinoda’s sand, and building the monumental pillars designed by the Argentinian artist, for instance. But at Kalba, when I asked after the “other constructors” of Villar Rojas’ pillars (reportedly, twelve men helped Villar Rojas construct his monumental pillars), the curator bristled at the question: “That’s a stretch of the imagination,” Joo said, to call the construction workers co-creators. She is clearly of the school that worships the artist alone as master and creator, wherein the labour that accompanies that of “master” is made invisible. Strange that the very constructs Joo purportedly wanted to question in theory during the March Meeting discussions, or conceptually address through artworks, was not something she wanted to apply to the practicalities of building and maintaining artworks. It’s funny how one can subscribe to the philosophy of monument construction (whether it be physical buildings or an artist’s or a curator’s ego) as a means of ensuring one’s self-worth—so much so that a question about the construction of material objects is perceived to be threatening enough that it needs to be slapped away. Given that the artworks in question were, in fact, meant to begin a conversation about impermanence, her reaction bordered on the absurd.

When one attends exhibition spaces like that of the Sharjah Biennale, and experiences the political, philosophical, and aesthetic messages that biennales or even smaller, but politically significant exhibitions are attempting to project, it’s impossible not to think about the role that art, and the shaping of art play in shaping the nation. Despite the popular belief that art exhibitions and biennales—and the curators who fashion them, as well as the artists who are invited to them—remain critical of dominant narratives within those locations, many are actually instrumental to fashioning national identities and the ideologies of nation states. Curators and artists alike are more likely to reflect the face of their community and its values, even though they may simultaneously ask us to question certain portions of those values. Curators and artists are liable to being co-opted to create “heritage”, to signal togetherness after a long battle, to confirm solidarity between ordinary people despite political differences. Art can be harnessed as capital to coin legitimacy for nations, powerful leaders, and power itself—and curators, perhaps more than the invited artists themselves—play a crucial part in this political game.

Still, not everyone in the Emirates is blind to the complications that are part of everyday reality here—and difficult conversations about these realities are permitted. In another gallery in Sharjah, the Maraya Art Centre, an exhibition curated by Murtaza Vali—himself Gulf-raised as a kid in a family of Indian descent, who now lives in Brooklyn, New York. “Accented” highlighted a very different approach to questions one cannot avoid in the Gulf, with each artist engaging directly with migrancy, the lack of belonging one feels as part of the generations born there with no right to live and work in the Emirates, always being out of place. Here, the majority of the population is “accented” and marked as different, other—in the very location they and their families helped build. In one small, easily overlooked piece, “Shaping Resistance”, the artist listed each person who contributed his labour in alphabetical order: Tariq Mahmood Muhammad Riaz Ahmed, Sajad Hussain Bughio, Muhammad Shabbir Ahmad Din, Vikram Divecha, Shahid Ahmad Bashir Mahmood, Mohammed Mostafa Mohammed Junu Mia. The artist’s name was just one in the list. For this project, the artist gained permission from the Sharjah Municipality to conduct a two-month collaboration with Pakistani gardeners responsible for maintaining the park hedges at the Al Majaz Waterfront where the middle classes of Sharjah enjoy leisure time with their families. Divecha and his collaborators then subtly disrupted the formal and precisely manicured order of park shrubbery by shaping hedges into playful and irregular shapes: conical shapes here, a wave like formation there. First, the gardener-collaborators drew sketches that they identified as “khubsoorat” (Urdu for “beautiful”). Ideas for hedge designs were culled from this pool of sketches. In the gardens, through which I walked with Valli later, I saw modest bursts of playful self-expression permitted to otherwise invisible laboring hands—evident in shrubbery that was already growing over to erase that moment of visibility. At Maraya Art Centre, what I was seeing were some of the notebooks with sketches—a bird, some vegetation, a boat and a flag emblazoned with an easily recognisable sliver of moon, denoting a state that wants to illustrate its devotion to Islam. One person contributed small pieces of paper with writing, and these roughly torn rectangles were arranged in a small circle of petals.

After the previous day’s experience at Kalba, how revolutionary that small gesture seemed.

Brazil’s Cold Welcome to Dr. Carl Hart

Brazil’s mythological ethos of racial democracy exhausted itself, again, this past August.

Dr. Carl Hart, neuroscientist and professor at Columbia University, was invited to São Paulo by the Brazilian Institute for Criminal Sciences in order to lecture about the war on drugs and how it marginalizes and excludes blacks and poor people from society. The media went into a titillating frenzy before he uttered a single word because he had been, supposedly, barred from the Tivoli Moffarej. The five-star hotel’s PR machine quickly rebuked the accusation by releasing inaudible video footage showing Dr. Hart going straight to the toilet upon his arrival and circulating on hotel premises without incident. Their guest later corroborated the story in an online interview, adding that he was approached by conference organizers as soon as he came out of the restroom. They apologized because, as he entered the hotel, a security guard, believing that a dreadlocked black man had ventured far beyond his designated confines, was about to approach him. However, Dr. Hart clarified that his entrance to the hotel was uneventful and all of the energy that was used to express sorrow and regret over an incident that never happened, should instead be used to address serious racial problems that continue to plague Brazilian society.

I can’t imagine another place on the face of this earth that prides itself more on racial diversity than Brazil. Even the United States’ post-racial fairytale has worn thin as the Black Lives Matter campaign sweeps the country. Now, that’s not to say that Brazil is not diverse. African, Tupí-Guarani, Portuguese and other European contributions to the country’s sociocultural aesthetics are undeniable. However, this argument reeks foul as it’s subsumed under the canopy of racial democracy. Heralded into the public imagination at the turn of the nineteenth century, dominant white society couldn’t have found a better cliché ally that veiled and nullified legitimate claims of institutionalized racism. In layman’s terms, racial democracy implies that miscegenation between three primary groups (Indians, Africans and Europeans) produced a country void of racism. It was conceptually part and parcel of maintaining Brazil’s hyper-stratified society, tactfully detruding and keeping Afro-Brazilians at the very bottom of the socioeconomic totem pole.

In recent years, the Brazilian government has implemented higher education and television quotas for Afro-Brazilians, slightly increasing their enrollment in public and private universities and presence on TV screens. The Folha de São Paulo, one of Brazil’s most influential and widely read newspapers, responded by producing a video stating why the organization doesn’t support quotas. Earlier this year Amnesty International released a report stating that mainly young and black residents of favelas (shanty towns), rural workers and indigenous peoples were at particular risk of human rights violations. Also this year, Ban Ki-moon, the United Nations Secretary General stated that 50,000 people are killed in Brazil every year. A joint study released by the UNESCO, the Latin American Social Sciences Institute, and the Brazilian government revealed that, of those deaths, black people were 142 percent more likely to be targeted. A major Brazilian television station reported the findings but excluded the exorbitantly high percentage of black victims. In 2013, Cuban doctors arrived in Brazil as part of a program called Mais Médicos (More Medics). Their mission was to attend to the needs of economically impoverished and secluded communities, areas that had been historically ignored by Brazilian doctors, an overwhelming majority of whom are, inevitably, privileged white men and women. Upon the arrival of Cuban doctors in the state of Ceará, hordes of Brazilian doctors lined the airport terminals and chanted “slaves” and other epithets at the black medics who had come to help.

So powerful is the idea of racial democracy that it also impacts the viewpoints of some Afro-Brazilians. Once, while in the northeast of Brazil, I spoke with a young black man about the dynamics of society and power. He chided my innuendos linking access to resources to an elite, white monopoly. Fatigued by our cat and mouse debate, I bluntly stated that we cannot ignore the fact that these individuals control the upper echelons of political and economic power in this country. He immediately countercharged that some black people can be just as racist as white people. Our discussion ended and my dear fellow returned to his impoverished community, home to many black people.

Ironically, Dr. Hart’s main purpose of traveling to Brazil was overshadowed by the viral trivialization of an event that, seemingly (seemingly), never occurred. An outcry of regret and apologies followed but he declined to accept. He had seen and heard enough, refusing to be hoodwinked by the sexy lore of racial democracy. Even his lecture, shortly before it got underway, profiled the confluence between the war on drugs and racism. As everybody gathered in the auditorium, strange sensations must have converged upon him. The audience settled into their seats. The guest speaker opened his discussion by saying (this is my translation from what was reported in several Brazilian media outlets) “Look beside you—do you see how many black people are here? You should be ashamed of yourself.” In an audience of roughly one thousand people, mainly criminal lawyers and judges, Dr. Hart only saw two or three black people.

November 18, 2015

#MovieNight

This is the first edition of a new weekly series of posts/listicles we’ll be doing to keep you up to speed with the world of African cinema/TV/online video content. We’ll be sharing news, trailers and complete short films. Welcome to our movie night.

1. Remember director Ava DuVarney’s distribution and exhibition network ARFFM? It’s now an “independent film distribution and resource collective” called ARRAY. It opened its first two films they’re opening last Friday: Sarah Blecher’s “Ayanda” set in Johannesburg and Takeshi Fukunaga’s Liberian immigrant tale “Out of My Hand.”

Here’s a teaser for “Out of My Hand”:

BTW, read an interview with Fukunaga about making “Out of my hand” from our archives.

2. The British Film Institute interviewed Rwandan filmmaker Kivu Ruhorahoza (he is talented for real) on his new film “Things of the Aimless Wanderer.”

3. The trailer for the new film, “Am I Too African to be American or Too American to be African?” (It seems to be from the same genre as “The Neo-African Americans.”

Here’s the trailer:

4. More trailers: Watch the trailer for “Sembene!” the new documentary about Ousmane Sembene, the “Father of African Cinema”

5. Check out this dystopian Kenyan short Monsoons Over The Moon over two parts (HT @ShadowandAct):

6. South African performance art duo FAKA have released a new video which they call a “Gqom-Gospel Lamentation for Dick.” (The video was in part inspired by South African pop icon Brenda Fassie’s rendition of the song “From a Distance,” which in itself is worth a rewatch.)

7.. Watch Miel a new short film inspired by black migrant experiences by Belgian/Congolese brother and sister team Malkia and Nganji Mutiri.

8. “Africa” now has its first superhero TV show (can this first be confirmed?). It’s is a South African production. Here’s a trailer.

9. Finally, “The World’s First American Nollywood film” (this must be the week of firsts?), “Pastor Paul,” recently premiered in Ghana. Here’s a teaser:

The emperor gets a new wardrobe

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently had 40 African leaders donned in his signature raw silk kurtas (aka Modi jackets) and safas at the closing gala of the India-Africa Forum Summit in late October. The gesture symbolized “stitching together the fabric of new partnerships with Africa,” wrote author Vikas Swarup (of Slumdog Millionaire fame), on Twitter. As India tightens its grip on economic powerhouse status, the Summit is part of a broader strategy for India to gain greater access to growing economies in Africa.

India also announced at the Summit a commitment to offer billions in credit, build infrastructure for health, agriculture, start a development fund of $100 million and provide 50,000 scholarships for African students (to mention a few). India has clearly taken note of China’s success in a $200+ billion courting of the continent. On a purely business level, it makes sense for India to leverage the popularity of development discourse to infiltrate Africa. This way, the subcontinent positions itself both as generous cousin and friendly proprietor.

I am not denouncing the potential merits of some bilateral partnerships; nations usually do not make economic strides alone. African states want to grow and African people are eager for greater opportunities and incomes. Knowledge exchange is a good thing, as can be trade and access to the resource pools of foreign partners who have more advanced infrastructure and technology.

Nevertheless, the approach of many African leaders is to engage with various foreign partners who offer similar vices vis a vis development, that is; aid, debt and outsourcing. At the recent Indo-African Summit the Indian Government showed it was willing to help African leaders get their financial fix. The effect is that Indian cultural influence will likely rise in Africa, while African political elites will continue to use the spoils of development to serve their personal interests.

For example, Lesotho Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili was quoted at the India Summit praising the Indian armed forces, who have been training officers from Lesotho as a form of in-kind aid. The Mountain Kingdom is becoming increasingly military-run with a polarizing Lieutenant General who was appointed by Mosisili. A football match between the military and National University of Lesotho students recently turned violent because the military disapproved of the students’ song choices. No one was prosecuted.

Events like the India-Africa Forum Summit make one wonder about the untold millions of dollars dedicated to shaping specific public perceptions about quality and outcomes. On the surface, India is the charitable patron who aims to build training facilities for skills development and enhance manufacturing capacity as well as self-reliance. But aside from a $10 billion concessional credit and $7.4 billion credit programme, the Indian government’s proposed reforms will enhance their profile and brand image more than contribute to any kind of “development”.

The politically correct justification for the habitual insistence of countries such as India and China to exploit national friendship as a mechanism for commercial benefit is that there can be unity in diversity. Do we therefore shut up and feign ignorance to the apathetic capitalistic agenda at play?

Evidence of how well South African and Chinese enterprises blossom in Lesotho is already observable in the clothing choices of many Basotho. It is not uncommon to see Basotho in Chinese attire at shopping complexes or walking on the streets. It should not come as a surprise then, to see a rise in popularity of saris and Modi jackets on the streets of Maseru and other African cities as Indo-African ties strengthen. The adoption of foreign style is an indicator of the power and financial influence of the foreign investors who woe African leaders under the guise of development. With the closing of the India-Africa Forum Summit and the promises such an affair brings, the emperors of African countries are once again wearing new clothes.

*The Inequality Series is a partnership with the Norwegian NGO, Students and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Through writing and dialogue, SAIH aims to raise awareness about the damaging use of stereotypical images in storytelling about the South. They are behind the Africa For Norway campaign and the popular videos Radi-Aid, Let’s Save Africa: Gone Wrong and Who wants to be a volunteer, seen by millions on YouTube.

For the third time, SAIH is organizing The Radiator Awards; on the 17th of November a Rusty Radiator Award is given to the worst fundraising video and a Golden Radiator Award is given to the best, most innovative fundraising video. You can vote on your favorite in each category here.

November 17, 2015

Xenophobia after the #ParisAttacks isn’t limited to boneheads like Rupert Murdoch

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Paris on Friday, several news-outlets reported that one of the terrorists may have entered Europe as a refugee. This made global headlines, and will likely have fixed itself in the public memory despite the fact that all of the attackers so far identified were EU nationals. The media went with the story regardless, and the connection between the attacks and the refugee crisis cannot now be undone in any simple way.

Legally speaking, nobody enters Europe as a ‘refugee,’ and the application process for refugee status is incredibly lengthy and complicated. We should all be skeptical about the naked attempt from the political right to hijack public sentiment around the Paris attacks to make cheap political capital out of basic xenophobia.

While European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker asked EU countries not to confuse criminals with asylum seekers and refugees, politicians began publicly linking the migrant crisis to the recent terrorist attacks in Paris. And this wasn’t limited to Rupert Murdoch’s incoherent twitter handle, or boneheads like Jeb Bush and Ted Cruz grandstanding in the United States. Marine Le Pen (from the extreme right National Front) said in a speech following the reports that one of the attackers arrived to Europe through Greece, that it was time for France to “take control of its borders” and return its “illegal” migrants to their countries. Polish minister for relations with other European nations, Konrad Szymanski, was also quick to announce that Poland was backing out of the EU’s quota system in order to “retain full control over its borders, asylum and immigration.”

It is important to recognize that these politicians are using the recent attacks to bolster their calls for keeping migrants out, and it is perhaps even more important to remember that these statements are coming from xenophobic right-wing parties who have long advocated a closed-door policy, and not solely for security reasons. Le Pen, for example, went as far as calling for a referendum on France pulling out of the EU, arguing that “the European Union is death: the death of our economy, our social welfare system and our identity.” The Paris attacks also took place three weeks before France’s regional elections and for Le Pen, this is a time to capitalize on xenophobic fears by using the words “migrant” and “terrorist” interchangeably.

It is essential to remember that issues of minority and refugee rights have long been pressing in Europe, and that the EU needed to conduct immigration reforms long before the attacks. Politicians were already deeply divided over how to handle the influx of migrants. It is therefore of no surprise that the recent attacks only serve to fuel right-wing populism.

Waiting to be local

The predicted El Niño rains start in September. Kampala is wet in the afternoons and sometimes in the nights too. The traffic jams are jarring. It is wise to stay home. It is wise to stay home because you resigned from your three part-time university teaching jobs in Kampala to move to London for a fellowship at the African Leadership Centre. Does it matter to the British visa and immigration official who will allow or deny you entrance?

It is wise to stay home because you do not want to explain the shame and embarrassment of having to wait for three weeks to be judged fit to live in London, to friends who are demanding on social media for a photo of you in Trafalgar Square. You are stuck here waiting, for your passport to be returned to Kampala from Pretoria where UK visa and immigration decisions are made, so you can fly into the term that is already two weeks underway.

That is when the video and transcript of Taiye Selasi’s TED talk, about being local in many places across nations, finds its way into your Kampala living room. The crux of the talk is against the idea of a nation. Localities should matter more than ‘nations’, or ‘countries’, Selasi orates. The question “where are you from?” does not make sense to her. She wants to be asked where she is local instead.

“I have no relationship with the United States, all 50 of them, not really. My relationship is with Brookline, the town where I grew up; with New York City, where I started work; with Lawrenceville, where I spend Thanksgiving. What makes America home for me is not my passport or accent, but these very particular experiences and the places they occur. Despite my pride in Ewe culture, the Black Stars, and my love of Ghanaian food, I’ve never had a relationship with the Republic of Ghana, writ large. My relationship is with Accra, where my mother lives, where I go each year, with the little garden in Dzorwulu where my father and I talk for hours. These are the places that shape my experience. My experience is where I’m from.”

The first week of October is gone. There is some news from Pretoria. They want you to send them proof that you are not infected with tuberculosis. Jesus Christ. You already had to sit two separate English tests to prove that you could study and live in London. The list of things you have had to do is long, and maybe when you get the visa you will forget about it, but tuberculosis?

You do the test and send the results. And wait. Revisit Taiye Selasi’s speech. One of the things that pulls you to speeches, novels, plays, films, music, art and other works of creativity is their ability to reflect your own happiness, sadness, triumphs and troubles, thoughts and experiences. You listen for a second time because you somewhat hope that she remembers that not everyone has permission to turn anywhere in the world into their own locality. To claim any place as their home. Some people are allowed only one home, and some, no home at all.

You wonder if what Selasi is describing is within your reach. You wonder if you can ever look at Catford in London as the place where you are local. Whether the rituals, relationships and restrictions that you will have in Catford will ever matter at all. How does one shed off their foreignness to be able to claim places that do not want to be claimed? What does it take for one to call a place their locality? You once lived in Budapest. Could you call it your own? You spent a few months in Hamburg, but long enough to have rituals, build relationships and become aware of your restrictions. But can you ever call it yours?

Selasi says that human beings can’t be multinational in the sense that a company like Nike is. But maybe multinational commodities are exactly what neoliberal capitalism makes of us – coming on the heels of the industrial revolution, enlightenment and whatever else has put monetary and other types of values on everything, including human lives. When the British visa official decides that I am fit to study and live in London, and a certain someone (whose names we never take time to even note) is not fit enough, what they are in essence doing is assigning a value to these lives and experiences. Deciding which ones they want, and which ones they do not.

Some of us will not accept that we are unwanted. And so we find ways of appearing in spaces of which whole institutions were established to keep us out. When we appear, do we have the same right to own these spaces and call them our own, and shrug off the identities that locked us out before? What does it take for one’s psyche to feel at home in more than one place? What does one do to earn that privilege? Is it carrying a British passport? An American passport? Both? But then again, there are those who carry those passports and still are not allowed to own nor claim any locality. This is why they are asked again, where they are ‘really’ from when they answer the first time by referring to a locality that their passport proves. You can’t be from there is the message. You are not allowed to be from here.

So when my waiting ends, I will need to find some advice on how to own a place, on how to remove myself from the metaphysical and physical space that the British visa and immigration office is established to cement, such that Catford becomes my locality. But I won’t get ahead of myself; I resume my waiting.

*The Inequality Series is a partnership with the Norwegian NGO, Students and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH).

Through writing and dialogue, SAIH aims to raise awareness about the damaging use of stereotypical images in storytelling about the South. They are behind the Africa For Norway campaign and the popular videos Radi-Aid, Let’s Save Africa: Gone Wrong and Who wants to be a volunteer, seen by millions on YouTube.

For the third time, SAIH is organizing The Radiator Awards; on the 17th of November a Rusty Radiator Award is given to the worst fundraising video and a Golden Radiator Award is given to the best, most innovative fundraising video. You can vote on your favorite in each category here.

November 16, 2015

A book for George Clooney and college classrooms on humanitarianism

In the world of transnational activism, there is a pre- and post-#Kony2012 era. In fact, #Kony2012 constituted a cathartic moment, a psychotic disturbance – both literally and figuratively – that unleashed an unprecedented amount of questioning and criticism of international advocacy networks and their methods.

A new book, Advocacy in Conflict: Critical Perspectives on Transnational Activism, edited by Alex de Waal, a British researcher and writer on African politics, is part of this trend. The post-Kony2012 model of advocacy is “driven by a dominant western NGO or network, run by specialized lobbyists who act as brokers with policy-makers, adapting their agenda and methods to accord with the practicalities of that lobbying process” (de Waal, p.37). These specific forms of activism have weakened or led to abandonment of key principles of advocacy. Thus the book’s editor and authors advocate a “reclaimed activism.” How can international advocacy movements be self-reflective and accountable to the people on whose behalf they speak?

The high profiles case studies include the campaigns for democracy in Burma and for indigenous rights in Guatemala, activism against conflict minerals in the Congo, the movement for Palestinian rights, and the campaigns against the Lord’s Resistance Army, better known as #Kony2012. On the latter, the book sheds light on the problems of single conflict narrative of the #Kony2012 debacle, the trouble with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) and its American lobbies, as well as lesser thought about transnational activism concerning for instance the quest for disability rights, or the campaigns against land grabbing or small arms trade in Africa.

American political scientist Laura Seay examines the case of the “conflict minerals” campaign in the DRC, which was spearheaded by the Enough Project, a Washington, DC-based group. Seay argues that the evidence shows that the campaign has had adverse effects on the economy and politics of the DRC. As Seay contends, the campaign “constitutes a case of ‘policy-based evidence making’ … in which a predetermined narrative overrode evidence contrary to the narrative’s claims” (p.116). The unintended consequences of section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act (which requires US companies to disclose if any of their products contained “conflict minerals” (gold, tin, tungsten and titatium) which originated in the DRC), included loss of employment for the locals, harm to the regional economy, and the shutting down of mining activities which led to increased militarization of the Kivu provinces. The Western NGO does well, Congolese do not.

This was not a one-time occurrence but a central dynamic of this form of advocacy. As De Waal notes, “Transnational advocacy occurs where humanitarian action meets social and political activism” (p.19). Although many supporters of the Kony2012 movement were young social liberals, one may also note “contiguities with right-wing evangelical Christian groups that have aggressively promoted a homophobic agenda,” which means that transnational activism “can be progressive at home and regressive abroad” (p.19).

The cases analyzed in the volume point to the larger issue of what may be called “Bono’s humanitarianism.” This variety of work does not challenge the power, given that one of the organizing principles of humanitarian action is to use resources and expertise to “mitigate suffering, so as to preserve existing power” (p.20, emphasis added). This argument echoes Roxane Doty’s assertion that foreign aid does at the global level what the welfare system does domestically – mainly enabling the administration of poverty, and the surveillance and management of the poor.

Instead the authors note, ultimately, “reclaimed” activism is “activism that prioritizes the empowerment of people (rather than media impact) as the basis for transformational change, and that is accountable to the people most affected by an issue” (p. 271). The essential components of “reclaimed activism” include empowering local actors, assessing the broader context underlining the events, encourage a wide range of actors to participate in activism campaigns, and promoting diverse voices and understandings of an issue.

Although these solutions seem like common sense rather than eureka moments in activism, I am left wondering if trying to “reclaim” activism by reverting to these strategies does not miss the point that there has not been a triumphant golden era activism to revert back to. A call to adopt and embrace these strategies seems to resonate better in my mind as a progressive goal for which we should aim than one to revert, as if they were here ante, and had been abandoned.

The primary target audience of this book is western activists, especially at a moment where activist campaigns recruit mostly from high schools and college campuses. Consumers of advocacy campaigns will also do well to read this book, “before rushing to buy bracelets and posters or participating blindly with the assumption that good intentions are good enough” (p.280). The book is also important as a teaching resource for US academics (those who shape the minds of the recruits targeted by Western NGOs and other humanitarian institutions), relevant for western media coverage of transnational activism, and will certainly resonate with local constituencies that are affected by transnational activism one way or the other. And as one blurb of the book remarked, “George Clooney should read it from cover to cover.”

There will be think pieces

There will be many think pieces composed about the #ParisAttacks. They will be thoughtful, they will be polemic, and be jingoistic and angry. They will express love, hate, and fear. They will be weary and wary – they will be received wearily and warily. They may be all of these things and more all at once.

These articles, the books that will come of them, the policy changes and immigration debates and socio-cultural shifts that will arise alongside them will be about Daesh/ISIS and their goal of hell of earth.

They will be about French and European and American democracy (“civilization”) and Islam’s supposed incompatibility with those presumed ideals. They will be about Muslim condemnations of the attacks and about the predominately Muslim victims of other attacks.

They will be about the French bombing raid of Raqqa and the “colonial tax” that fourteen African nations pay to France that may well fund the onslaught besieged civilians in Raqqa now face.

Hollande, Credit EPA

They will be about locating the roots of contemporary terrorism within the frightening constellation of Western warmongering, bought dictators, and Wahhabism. They will be about Daesh’s indisputable origins in the Iraq War.

They will be about the Daesh bombings in Beirut, the rising death count in Egypt at the hands of Daesh, the Iraqis and Syrians who everyday fight to survive in nations torn apart by a Hydra of warfare. They will be about the impossibility of ending wars that grow twice larger for every one that is inadequately put out.

They will be about the 24-hour live feed news cycle and Facebook safety checks and the sudden ubiquity of the French Tricolor in response to devastation in Paris and the comparative silence on Beirut, Baghdad or Mogadishu and Northern Nigeria.

They will be about lazy social media algorithms that resurrect old, underreported incidents of trauma and violence in Kenya and Yemen. They will include sloppy dismissals of places “over there” (like Africa and Asia?) that are “used to” such violence and therefore do not command our equal attention. They will be about France’s current state of emergency and its frightening origins in the Algerian War for Independence. They will be about the last massacre that took place in Paris: a massacre of Algerians in 1961 at the hands of French police.

Credit: Antoine Antoniol (Getty Images)

They will be about anti-Muslim and anti-black and anti-brown violence on a global scale. They will be about the far-right and the disintegrating left. They will be about the discomfiting lyrics of Le Marseillaise and those who sing it for comfort.

Some of these articles will also be about subverting Daesh and disrupting Islamophobic and xenophobic backlash. They will be about the beautiful game and Saint-Denis and how football unites and divides us.

They will be about the 11th arrondissement and the diverse, hopeful, too young people who have died and those who live. They will be about Adel Termos, who wrapped his arms around a suicide bomber in Bourj al-Barajneh and died so countless others could live. They will be about Waleed Abdel-Razzak, critically injured by the blasts while he queued outside the State de France for tickets to the match – not an Egyptian terrorist but in fact a loving son, brother, and football fan.

There will be many pieces like these. There will be many more to come. We will mourn again. Some of us have been mourning already. Even more have never stopped mourning. Too many.

Daesh wants refugees to have no refuge. They want a global war. They want to expand the global war that the United States and other Western nations have been waging for over a decade. A lot of our heads of state want to give it to them. If there is a moral high ground, it is unclear who occupies it. If there is a moral high ground, it rests on the countless victims of our unending wars. One thing is very clear, however. There will be articles. There will be many more articles. And we must decide what we need from them. What we demand from them. Do we want to be a little more human, or a little less, as this rock we live on hurtles around the sun?

For me, a Muslim apostate, I hope it is more. More human. More humanity.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers