Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 318

December 5, 2015

Weekend Music Break – Madiba The 5th December Edition

On this day two years ago, Nelson Mandela passed. Madiba and his legacy has been covered widely on this site already, so for this weekend’s music break we’re going to jump into the archives and feature a collection of favorites we’ve already dedicated to him, as well as some new new new… If you have some reading time as well this weekend, check out our Mandela archive here.

December 4, 2015

Decolonising Lesotho’s Literary Landscape

The past few weeks have been a tough balancing act for Lineo Segoete. She is co-director of Ba Re, Lesotho’s only literature festival founded in 2011 by the late, great pearl of infinite wisdom Liepollo Rantekoa. The festival runs over two days and starts today in the capital Maseru. Segoete had had to deal with last-minute cancellations from guests (Kenya’s James Murua) and “concerns” from Rantekoa’s family. The latter, she says, arose out of lack of constant back-and-forth communication, and have been ironed out.

But it’s generally been a good year for Ba Re, short for ‘Ba re e ne re’ (Sesotho: Once upon a time). They have experienced exponential growth since 2011, the year in which Liepollo gathered poet and author of the recently-released A Half-Century Thing Lesego Rampolokeng, along with Kgafela wa Magogodi as guests at the inaugural showcase. This year’s line-up of the two-day festival has writers from around the continent. Besides the festival, Ba Re the organization is in continuous engagement with various stakeholders in Lesotho to revive the country’s once-bustling publishing industry — Thomas Mofolo’s Chaka comes to mind — and to boost literacy rates and build an appreciation for the arts in general in a country which doesn’t see a correlation between Creative Industries and Science- and Business-oriented subjects, in effect downplaying the importance of the former.

To this end, Ba Re have initiated a partnership with Peace Corps in Lesotho whereby on-the-ground volunteers run writing competitions and a spelling bee contest in the country’s 10 districts. “We hold a national ceremony with the outcomes,” says Lineo, the co-director. “The spelling bee was actually the highlight of our year. We had students from all of the districts except Maseru. That was deliberate because we actually do want to reach out to the outskirts, the more rural areas where access to these kinds of resources are super-limited,” she expands. There were prizes on offer for all of the participants. The winners received full scholarships for the next academic year.

Lineo re-counts last year’s festival by way of a Sesotho saying “Ha ho ntho’e mpe e se nang molemo.” A few months away from the festival, the then-tripartite Lesotho government, headed by Motsoahae Thabane, suffered a military coup. A state of emergency was declared, leading to safety concerns from funders who eventually pulled out of the event altogether. Still, they were able to pull strings together and make the festival happen. Yewande Omotoso and the Chimurenga massive were among those in attendance.

“What we took from that [experience] was that there’s a great need for artistic expression in the country. Most of our guests from last year were like ‘guys, this is a landmine! You should be writing about this. This should be a book. You should be published!” says Lineo excitedly.

Lineo Segoete is co-director of the Ba Re E Ne Re literature festival

The festival happens in the midst of political instability yet again. Though not as tense as last year, events surrounding the impending release of the Phumaphi commission’s report — set up following events which included botched assassination attempts on the former Prime Minister, and the assassination of former army commander Maaparankoe Mahao — have rendered Lesotho a shadow of its former peaceful self.

Ba Re have heeded the wise words of last year’s participants and are using the festival to, among other things, imagine a future for Lesotho’s arts industry, and to have a conversation about decolonising the country’s literature sphere. “From the writing competition, we learned that there is a lot of creativity in the country, and it’s quite different from what we are used to in terms of the books that have been published in the past, which were mostly influenced by religious dogma and politics.” Lineo says that what they are encountering is a shift towards a “broader worldview” which is reflected in the writing. “To us, it reveals that we are aware that we are part of a global society and we’re just trying to claim our place in this world that we live in,” she added.

Besides their core activities, Ba Re are also seeking out ways to help writers get published. Lineo says this is where their growing network in the field of literature comes in handy. She shares a bit about her exchange with Moses Kilolo from Jalada Africa. “[We] started talking on social media and sharing ideas and conversation. We were like ‘you know what, we should have someone from Jelada Africa come to Lesotho as well, especially because you guys deal with publishing and you have such a great set-up. We can actually learn a lot from you!'” she says.

As our conversation nears to an end, Lineo shares the following sentiment: “Part of the underlying motivation behind this project is for us to be more in touch with our cultures, especially considering our colonial heritage and history. The fact that we’re doing this in Liepollo’s memory is a way of acknowledging our ancestors. For us, that is an even bigger motivation. It’s a communication between us and the other side of life; a conversation between the past and the present.”

* The festival starts today 5-6 December 2015 at Machabeng College in Maseru. This year’s theme is “Reclaim your story”

A Cartographic Narrative–The 1760-1761 Slave Revolt in Jamaica

In my opinion, spatial analysis represents one of the most compelling new modes of storytelling provided by the digital turn. David Bodenhamer noted the value of spatial analysis in an interview for the New York Times in 2011. The value of the “spatial turn” as some have termed it, Bodenhamer argued, is that it “allows you to ask new questions: Why is it that something developed here and not somewhere else, what is it about the context of this place?” These new questions that arise with the implementation of spatial analysis, as Bodenhamer suggests, add new features to historian’s traditional analysis of change over time. Projects like this week’s featured site, Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760-1761: A Cartographic Narrative, expand these investigations from change over time to change over time and space, both conceptually and visually.

Slave Revolt in Jamaica visualizes the story of the “greatest slave insurrection in the eighteenth century British Empire.” In 1760, in the midst of Britain’s Seven Year;s War, around 1500 enslaved men and women staged a massive insurrection in Jamaica; a struggle that lasted from April 1760 to October 1761. This project not only maps the events of this insurrection dynamically, providing an animated tour through the events of this insurrection, but also provides a curated archive of documentary evidence to support the data given on the map. The data and archive on the site was accumulated and organized by Vincent Brown, is a professor of History and African American Studies at Harvard University. Slave Revolt builds on Brown’s corpus of written analyses of death and slavery in the Caribbean specifically and the Diaspora more broadly.

It is important to note that this project, just like Brown’s written works, represents an argument. The “narrative” in the site’s title is not only descriptive, but also represents a central tenet of the project’s goals. This is not simply a map displaying data. It is a narrative of the events of the slave insurgency and an argument about the nature and character of the rebellion. Brown intended to use this map as a way to change the debate around “public perceptions of black insurrection. Brown explained in a 2013 interview:

As with more recent disturbances, people at the time debated whether the slave insurrection in Jamaica in 1760-61 was a spontaneous eruption or a carefully planned affair. Historians still debate the question, their task made more difficult by the lack of written records produced by the insurgents. Cartographic evidence developed…shows that the rebellion was in fact a well-planned affair that posed a genuine strategic threat, not an indiscriminate outburst.

In addition to the historical argument that Brown presents through the map, one of the most compelling things about this project is it’s simple, well-constructed design. Brown built Slave Revolt in Jamaica with Axis Maps, a company specializing in custom interactive maps (you can find some of their other collaborations here). David Heyman, the managing director of Axis Maps, noted the power of interactive mapping in a 2013 interview on the project for The Voice Online. “We wanted to build the simplest and most elegant map possible in order to provide users – expert historians and members of the public alike – a high quality and detailed narrative of the uprising, allowing them to understand the story visually as well as through text,” Heyman explained, “Interactive cartography provides a completely new method through which to interpret existing demographic and event data into a more rounded historical narrative, revealing surprising and unprecedented patterns that were previously hidden.” Slave Revolt in Jamaica is a compelling example of the power of interactive mapping for storytelling and scholarly analysis.

As always, feel free to send me suggestions via Twitter (or use the hashtag #DigitalArchive) of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

*This post is No. 23 in our Digital Archive series covering African archives on the web.

South Africa’s anarchist hip hop collective

How do you make people realize they’re in chains? For Soundz of the South (or SOS) – an anti-capitalist resistance collective from Khayelitsha, Cape Town – you give them hip hop.

That injunction dates back to hip hop’s origins in New York City. At street parties in the South Bronx in the 1970s, sound equipment was often wired up to park lampposts. Hip hop’s origins were strictly DIY and, most importantly, a direct reaction to the structural marginalization of communities and the racism of the mainstream media. SOS are carrying on that initial spirit through hip hop activism that is relevant to their own struggles.

As a collective of both activists and artists they are committed to decentralization, direct action, autonomy and self-reliance. Like anarchist thinkers Emma Goldman or Mikhail Bakunin, they believe that hierarchies corrupt and only horizontal organisation can eliminate inequality. Besides recording albums, SOS hosts regular meetings and “critical” documentary screenings, weekly slam sessions, organize protests and discussions, attend regular conferences and have set up campaigns such as “Don’t Vote! Organise!” or initiatives to save Philippi High (a school on Cape Town’s Cape Flats). They also started the Afrikan Hip Hop Caravan, an annual series of events (this is the third edition) currently taking place through the end of December.

A recent track was directly inspired by the collective’s involvement in the #FeesMustFall student protests. When I interviewed members Milliha, Anele, Khusta, Sipho and Monde, they were resolute that their music has to be political. “What hip hop should be about is hold accountable those who are in power,” says Anele. The reasons are that it’s a genre young people can relate to, and accessible because, as Milliha explains, unlike punk music, “You need a pen and paper, and the beat will come on its own.” The sentiment is that, when country’s President, Jacob Zuma’s main virtue is a charismatic dance, and bling bling, booze and bitches flood the mainstream, grassroots hip hop is the alternative media.

SOS members, who are also part of other activist organizations such as the Housing Assembly and ILRIG, understand that there’s more to social change than music. To be part of the collective, you have to be involved in regular discussions, protests, meetings, take on tasks, organize, and identify with the principles. Many times on-the-ground work comes first, which inspires ideas for songs. But Anele stresses, what hip hop does do is help listeners wake up and mobilise action. “It demystifies big issues and brings politics back to the people,” he says, or as Monde puts it, “We’re taking whatever is out there and bring it closer to those who can’t reach it.”

The Afrikan Hip Hop Caravan aims to take this kind of awareness across the continent. It was conceived by SOS, Uhuru Network, and various cultural activists in 2011. In each participating African city, there’ll be the Afrikan Hip Hop Conference, to encourage discussion about hip hop’s role in community struggles, and the Afrikan Hip Hop Concert, to give repressed, underground hip hop a platform. 2015’s edition will start in Arusha, Tanzania, and the main focus will be migration against the backdrop of the recent xenophobic attacks in South Africa, the European refugee crisis, and shooting of black teenagers in the United States. Inspired by Dakar hip hop artists who got together to stop president Abdoulaye Wade from unconstitutionally seeking a third term in office, the idea is to explore the origins of certain problems, relate them to current issues and transcend borders.

SOS’s involvement in the caravan, as well as everything else they do, is self-financed. Strictly rejecting any funding from corporate brands (saying no to Red Bull for instance, Khusta tells me) to maintain autonomy, SOS decide collectively what happens to any proceeds. Nobody receives money to spend at their own discretion. Instead, Khusta explains, it goes back into the community. As a group with no set amount of members, they’re not interested in branding themselves nor registering with a label – “We don’t make songs for the radio,” says Anele.

In South Africa music has played an important role in the struggle of oppressed people. President Jacob Zuma must be aware of a rhythm’s convincing power – when it’s election time he brings mainstream DJs to the township. That’s why SOS don’t want listeners to switch off to their beats. Following Bakunin, they believe a “sweet” democracy that demands gratitude for pseudo-freedom distracts from important realities. “And that’s what we have, and that’s why we’re doing what we’re doing, to make people realise they’re in chains. They are working and creating wealth for others to enjoy,” explains Anele. Unfortunately, he continues, many anarchist comrades don’t get hip hop – “They see a lot of black power and think it’s nationalism” – but he’s convinced that there is no line between anarchism and hip hop. Hip hop is the voice of the working class.

*The Cape Town Afrikan Hip Hop Concert and Conference will take on December 12th 2015 at Moholo Live, and on December 13th at Buyel’mbo Village, Khayelitsha. If you can’t make it, watch out for Freedom Warriors Vol 3. and The Afrikan Hip Hop Caravan Collaborations from 2013 to be released soon.

December 2, 2015

Europe’s Eritrean “problem”

In the aftermath of the Paris attacks, many of Europe’s right wing parties were quick to insinuate Syrian refugees were to blame and to call for stricter immigration and border controls. But even before the attacks, some European governments were already maneuvering to prevent refugees from entering their countries. Eritreans—who represent one of the largest groups of refugees seeking safety in Europe in recent years—have been a primary target of those who would close Europe’s doors.

Efforts to exclude Eritrean refugees from Europe began over a year ago in Denmark. In mid-2014, the Danish Immigration Service embarked on a fact-finding mission to Eritrea after seeing a dramatic rise in the number of Eritreans seeking asylum. The mission report—based primarily on anonymous interviews in Asmara—declared conditions had improved enough that Eritreans would no longer be recognized as refugees in Denmark. Human rights organizations denounced the report, and two men who contributed to it resigned, saying they were pressured to ensure the report allowed Denmark to adopt stricter asylum practices. After a period of public pressure, the Danish government announced Eritreans would still receive asylum in Denmark, but the report remained public.

… For over a year, the European Union has also been quietly working with the Eritrean government on stemming migration and calling for, among other things, “promoting sustainable development in countries of origin…in order to address the root causes of irregular migration.” This October, the EU Development Fund announced it was resuming aid to Eritrea with a possible $229 million package for economic development in part to give peoplealternatives to migration. According to official EU sources, the funding will help tackle poverty and “directly benefit the population.” Such a rationale seemingly ignores that most Eritreans indicate leaving to avoid the regime’s human rights abuses—although officials said such cooperation allows “the EU to reinforce a political dialogue to highlight the importance of human rights.”

Read the rest here.

Flotsam No.1,000,0001

December 1, 2015

Africa is a Radio: Season 2, Episode 7

2015’s last episode of Africa is a Radio features a snippet from an extended interview with Pakistani-American journalist Rafia Zakaria, as well as a selection of tunes from Africa and the rest of the Atlantic world.

Check it out below, and see you in 2016!

Tracklist

1) Raury – Devil’s Whisper

2) Burna Boy – Soke

3) Oliver Mtukudzi – Ndima Ndapedza

4) Gah Gah – Kasbah

5) Interview with Rafia Zakaria

6) Booba – Mon Pays

7) Nasty C – Juice Back Remix feat. Davido and Cassper Nyovest

8) Ziminino – Intermitência

9) Nega Gizza – Filme de terror

10) Santos Junior – N’Gui Banza Mama

11) Fabregas – Mascara

12) Franko – Coller la petite

13) VVIP – Dogo Yaro feat. Samini

14) Kafu Banton – Vivo en el ghetto

15) Lokassa Ya Mbongo – Bonne année

Mahmood Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject, 20 years later

I first encountered Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism early in graduate school, in a class I took for its intriguing title – “Colonial Law and the Modern State.” In that class, and then in “Major Debates in the Study of Africa,” we were guided by Mahmood through Citizen and Subject and through the literature that went into shaping it; I subsequently came out of graduate school under the impression that everybody who studies African politics spends weeks reading Henry Sumner Maine’s Ancient Law and Jan Smuts’s lectures. After that experience, it was perhaps inevitable that Citizen and Subject’s framework for grasping the specificity of the political in Africa would shape the intellectual trajectories of many of us in those classes – it certainly did mine – as well as of many of those who studied with Mahmood in the decades before and the decades since.

Citizen and Subject has been particularly close to my mind of late, for this term is first time I have actually taught the book. For the last few years, during which I worked alongside Mahmood at the Makerere Institute of Social Research in Kampala, Uganda, Mahmood was there to teach Citizen and Subject himself. But now, running my own classes on African politics at Cambridge University, I have realized how essential the book remains. It is unparalleled in its ability to re-frame the polarized and reductive debates that are still the substance of Africanist political science, just as they were 20 years ago – debates over concepts like clientelism, corruption, democratization, ethnic violence, or civil society. And so when students ask, “but what’s the alternative?” there is almost always some place in Citizen and Subject to point to.

The book’s pedagogical importance derives from its method: at each step, a dominant debate is identified and the common presumption shared by the opposing sides to that debate revealed. The book thus seeks “to problematize both sides of every dualism by historicizing it, thereby underlining the institutional and political condition for its reproduction and for its transformation” (299). What a salutary change it would be if this one sentence were to replace the inevitable litany of focus group discussions and key informant interviews found in the “Methodology” sections of too many African politics research proposals!

The book’s method, in turn, derives from its understanding of political reality. It identifies the contradictory nature of all movements, all struggles, all efforts at reform, whether by state or by society. It shows how those efforts are shaped by the political structures they seek to transform, and so may end up reproducing those structures in the very effort to overcome them. Politics is a field of dilemmas, and transformation is tenuous and partial even in the best of circumstances. So there is no singular revolutionary moment but always multiple, allied but contradictory, processes of reform, as the dilemmas of state and social power are identified and negotiated. But this also means there is always cause for optimism, always an emancipatory moment that can be identified, proclaimed, and redeemed. Politics thus has an ineradicable intellectual dimension, for, as the book puts it, “analytical failures can become political failures” (29) – but analytical progress can also, thereby, help enable political progress.

Citizen and Subject is a call for the reform of the study of African politics, and itself exemplifies that reformed discipline. It declares its endeavor as being “to establish the historical legitimacy of Africa as a unit of analysis” (13). The “starting point” in this “creation of a truly African studies” is thus to establish “the commonality of the African experience, [which] seems imperative at this historical moment” (31). Once this specificity of the African experience is grasped, genuinely comparative global studies can proceed.

The book seeks the content of Africa’s specificity by tackling head-on what is typically seen as the continent’s irreconcilable internal difference: South Africa. Taking South Africa as part of Africa, the book argues, can best reveal what is common to the continent as a whole. Its unwavering commitment to bring South Africa back in, however, remains as uncommon today as it was twenty years ago.

And so the question of South Africa and African studies remains imperative. In fact, the question has received fresh political impetus by #RhodesMustFall at the University of Cape Town, #OpenStellenbosch, and other struggles in South Africa, whose demand to decolonize knowledge by bringing Africa into the curriculum – thus establishing a genuine African studies in South Africa – is paired with demands for the broader decolonization of the university.

Citizen and Subject, of course, has decolonization at its center, and explores the dilemmas of the vast efforts after independence to decolonize civil society, including decolonizing universities and the curriculum. Indeed, the decolonization of knowledge production was the substance of state intervention and social struggle from Makerere to Ibadan for years. This history of actually existing efforts at decolonizing knowledge production in Africa, however, raises a complex question for today’s struggles in South African universities. We might ask whether, by framing the task of radically transforming the university and establishing African studies in South Africa as decolonization, today’s South African struggles risk being temporally out of joint with struggles around justice in knowledge production elsewhere in Africa.

From a perspective outside South Africa, to represent the demand for justice in knowledge production today as the need for decolonization may appear outdated or paying short shrift to the ambiguities of actually existing decolonization. Elsewhere in Africa, the key task in justice in knowledge production may appear differently: Mahmood has often framed the Makerere Institute of Social Research’s objective as being to study the world from Africa, and not to study Africa as divorced from the world. I see this project as an effort to fulfill Citizen and Subject’s call for genuinely comparative study, in which Africa is a unit of analysis, thus breaking free from the limitations of African area studies while not ignoring Africa’s specificity.

Juan Obario, Suren Pillay, Manuel Scwhab and Adam Branch.

And so the efforts to establish a decolonized African studies in South Africa may need to engage with actually existing struggles over justice in knowledge production throughout Africa, past and present, if they are not to risk confirming South African exceptionalism – and African idiosyncrasy – in the very attempt to overcome that exceptionalism. This is precisely this kind of dilemma that Citizen and Subject helps alert us to in the broad process of decolonization. The effort to study the world from Africa may thus be the counterpoint that ensures African studies does not amount to an assertion of Africa’s idiosyncrasy. The South African student activists’ decision to put questions of intersectionality, patriarchy, and a living wage at the center of their agenda may represent this kind of counterpoint, opening decolonization up to analytical and political engagement beyond South Africa. Conversely, the demand for decolonization may be the counterpoint that ensures that “studying the world from Africa” starts from an engagement with Africa’s specific history and is not co-opted by neoliberalism’s “centers of excellence” and “world-class universities.”

Beyond Africa, the demand to decolonize knowledge and the university has resonated widely. In the UK, there is Rhodes Must Fall at Oxford and “Why is My Curriculum White” at the University of London. And of course, while Henry Sumner Maine and Jan Smuts may have been forgotten to students of Africanist political science, they are still very much present at Cambridge. The call to Decolonize Cambridge, to rethink the curriculum, to raise questions of access and representation, have increasing political heft in this post-colonialist context.

In many other places across the world with their own specific histories of relations with Africa, such as the Americas, the question of African studies is similarly provoking debates around justice in knowledge production. And perhaps the widespread rise in interest in the study of Africa globally, for instance in India, China, or Turkey, can lead the question of African studies to play a critical role in generating a broad re-thinking of global knowledge production and of the politics of the university. Critical debates around African studies – asking both about a decolonized study of Africa and a globalized study of the world from Africa – need to be cultivated in these many locations, thus helping to develop novel intellectual responses to the epochal political transformations we are seeing today. Which refers back to what I see as being the central lesson of Citizen and Subject: that it is the task of critical intellectual work to engage concrete political struggles, identify their emancipatory moments whatever their immediate limitations, and let this optimism help open the field of political possibility.

*Branch first made these comments at a special roundtable at the African Studies Association in San Diego in November 2015 on the twentieth anniversary of the publication, in 1995, of Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject.The panelists were former Mamdani students Suren Pillay, Juan Obarrio and Manuel Schwab.

Mahmood Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject, twenty years later

I first encountered Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism early in graduate school, in a class I took for its intriguing title – “Colonial Law and the Modern State.” In that class, and then in “Major Debates in the Study of Africa,” we were guided by Mahmood through Citizen and Subject and through the literature that went into shaping it; I subsequently came out of graduate school under the impression that everybody who studies African politics spends weeks reading Henry Sumner Maine’s Ancient Law and Jan Smuts’s lectures. After that experience, it was perhaps inevitable that Citizen and Subject’s framework for grasping the specificity of the political in Africa would shape the intellectual trajectories of many of us in those classes – it certainly did mine – as well as of many of those who studied with Mahmood in the decades before and the decades since.

Citizen and Subject has been particularly close to my mind of late, for this term is first time I have actually taught the book. For the last few years, during which I worked alongside Mahmood at the Makerere Institute of Social Research in Kampala, Uganda, Mahmood was there to teach Citizen and Subject himself. But now, running my own classes on African politics at Cambridge University, I have realized how essential the book remains. It is unparalleled in its ability to re-frame the polarized and reductive debates that are still the substance of Africanist political science, just as they were 20 years ago – debates over concepts like clientelism, corruption, democratization, ethnic violence, or civil society. And so when students ask, “but what’s the alternative?” there is almost always some place in Citizen and Subject to point to.

The book’s pedagogical importance derives from its method: at each step, a dominant debate is identified and the common presumption shared by the opposing sides to that debate revealed. The book thus seeks “to problematize both sides of every dualism by historicizing it, thereby underlining the institutional and political condition for its reproduction and for its transformation” (299). What a salutary change it would be if this one sentence were to replace the inevitable litany of focus group discussions and key informant interviews found in the “Methodology” sections of too many African politics research proposals!

The book’s method, in turn, derives from its understanding of political reality. It identifies the contradictory nature of all movements, all struggles, all efforts at reform, whether by state or by society. It shows how those efforts are shaped by the political structures they seek to transform, and so may end up reproducing those structures in the very effort to overcome them. Politics is a field of dilemmas, and transformation is tenuous and partial even in the best of circumstances. So there is no singular revolutionary moment but always multiple, allied but contradictory, processes of reform, as the dilemmas of state and social power are identified and negotiated. But this also means there is always cause for optimism, always an emancipatory moment that can be identified, proclaimed, and redeemed. Politics thus has an ineradicable intellectual dimension, for, as the book puts it, “analytical failures can become political failures” (29) – but analytical progress can also, thereby, help enable political progress.

Citizen and Subject is a call for the reform of the study of African politics, and itself exemplifies that reformed discipline. It declares its endeavor as being “to establish the historical legitimacy of Africa as a unit of analysis” (13). The “starting point” in this “creation of a truly African studies” is thus to establish “the commonality of the African experience, [which] seems imperative at this historical moment” (31). Once this specificity of the African experience is grasped, genuinely comparative global studies can proceed.

The book seeks the content of Africa’s specificity by tackling head-on what is typically seen as the continent’s irreconcilable internal difference: South Africa. Taking South Africa as part of Africa, the book argues, can best reveal what is common to the continent as a whole. Its unwavering commitment to bring South Africa back in, however, remains as uncommon today as it was twenty years ago.

And so the question of South Africa and African studies remains imperative. In fact, the question has received fresh political impetus by #RhodesMustFall at the University of Cape Town, #OpenStellenbosch, and other struggles in South Africa, whose demand to decolonize knowledge by bringing Africa into the curriculum – thus establishing a genuine African studies in South Africa – is paired with demands for the broader decolonization of the university.

Citizen and Subject, of course, has decolonization at its center, and explores the dilemmas of the vast efforts after independence to decolonize civil society, including decolonizing universities and the curriculum. Indeed, the decolonization of knowledge production was the substance of state intervention and social struggle from Makerere to Ibadan for years. This history of actually existing efforts at decolonizing knowledge production in Africa, however, raises a complex question for today’s struggles in South African universities. We might ask whether, by framing the task of radically transforming the university and establishing African studies in South Africa as decolonization, today’s South African struggles risk being temporally out of joint with struggles around justice in knowledge production elsewhere in Africa.

From a perspective outside South Africa, to represent the demand for justice in knowledge production today as the need for decolonization may appear outdated or paying short shrift to the ambiguities of actually existing decolonization. Elsewhere in Africa, the key task in justice in knowledge production may appear differently: Mahmood has often framed the Makerere Institute of Social Research’s objective as being to study the world from Africa, and not to study Africa as divorced from the world. I see this project as an effort to fulfill Citizen and Subject’s call for genuinely comparative study, in which Africa is a unit of analysis, thus breaking free from the limitations of African area studies while not ignoring Africa’s specificity.

And so the efforts to establish a decolonized African studies in South Africa may need to engage with actually existing struggles over justice in knowledge production throughout Africa, past and present, if they are not to risk confirming South African exceptionalism – and African idiosyncrasy – in the very attempt to overcome that exceptionalism. This is precisely this kind of dilemma that Citizen and Subject helps alert us to in the broad process of decolonization.

The effort to study the world from Africa may thus be the counterpoint that ensures African studies does not amount to an assertion of Africa’s idiosyncrasy. The South African student activists’ decision to put questions of intersectionality, patriarchy, and a living wage at the center of their agenda may represent this kind of counterpoint, opening decolonization up to analytical and political engagement beyond South Africa. Conversely, the demand for decolonization may be the counterpoint that ensures that “studying the world from Africa” starts from an engagement with Africa’s specific history and is not co-opted by neoliberalism’s “centers of excellence” and “world-class universities.”

Beyond Africa, the demand to decolonize knowledge and the university has resonated widely. In the UK, there is Rhodes Must Fall at Oxford and “Why is My Curriculum White” at the University of London. And of course, while Henry Sumner Maine and Jan Smuts may have been forgotten to students of Africanist political science, they are still very much present at Cambridge. The call to Decolonize Cambridge, to rethink the curriculum, to raise questions of access and representation, have increasing political heft in this post-colonialist context.

In many other places across the world with their own specific histories of relations with Africa, such as the Americas, the question of African studies is similarly provoking debates around justice in knowledge production. And perhaps the widespread rise in interest in the study of Africa globally, for instance in India, China, or Turkey, can lead the question of African studies to play a critical role in generating a broad re-thinking of global knowledge production and of the politics of the university. Critical debates around African studies – asking both about a decolonized study of Africa and a globalized study of the world from Africa – need to be cultivated in these many locations, thus helping to develop novel intellectual responses to the epochal political transformations we are seeing today. Which refers back to what I see as being the central lesson of Citizen and Subject: that it is the task of critical intellectual work to engage concrete political struggles, identify their emancipatory moments whatever their immediate limitations, and let this optimism help open the field of political possibility.

*Branch first made these comments at a special roundtable at the African Studies Association in San Diego in November 2015 on the twentieth anniversary of the publication, in 1995, of Mamdani’s Citizen and Subject. Other participants on the panel include were former Mamdani students Suren Pillay, Juan Obarrio and Manuel Schwab.

November 30, 2015

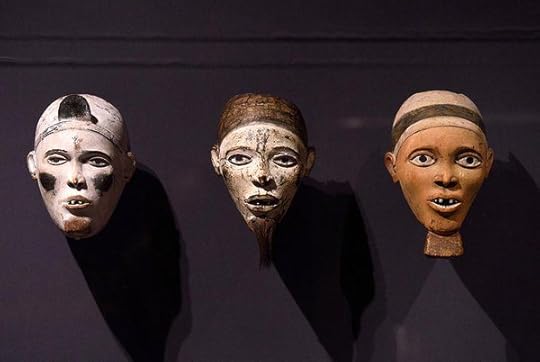

The Magnificence of Kongo Art

Twenty-one years ago, “Angolan Sculpture, memorial of cultures,” curated by Marie Louise Bastin in the Lisbon Museum of Ethnology, traced a panorama of ethnic and cultural diversity for Southwest Africa and in that way, dignified the once-Portuguese colony. Then four years ago, in 2011, Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau curated “Angola, figures of power” at the Dapper Museum in Paris. This exhibit, which lasted nine months and was a collaboration with the Luanda National Museum of Anthropology, for the first time brought together parts of ten different European collections on Angola. Well-respected researchers like Manuel Gutiérrez, Boris Wastiau, Manuel Jordán e Bárbaro Martinez-Ruiz were invited to write the catalogue, hold a conference, and debate art historical questions related to the exhibit. This gave Angolan art new visibility.

Now comes “Kongo: Power and Majesty,” a very important exhibit (until January 3, 2016) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, which exalts the glories and trials of the Kongo Kingdom. The show, curated by Alisa Lagamma (the Curator in Charge, Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Met), also comes with a beautiful catalogue published by Yale University Press.

The Kongo Kingdom comprised a vast area of Central Africa that today encompasses the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Angola. Kongo interacted with Portuguese, Dutch, and Italian traders, missionaries, and explorers across several centuries beginning in the 15th century. As a result Kongo artists produced new aesthetic forms, which are showcased in this show. The exhibit underscores that initially equal relations shifted to the detriment of the Kongo over time and the aesthetics of the work embody those radical changes.

Even though I worked for two years at the Museum of Anthropology in Luanda, I confess a greater attraction for contemporary African art. My fascination has to do with a better understanding of the arts from this time. But, even if it seems paradoxical, I still pay attention to how, through the years, museums around the world present classical and/or traditional African art (foregoing for now a discussion of these concepts).

In my view, “Kongo: Power and Majesty” is a beautiful exhibit because it puts the problems of history, like the slave trade and colonialism, front and center without minimizing them. The exhibit contains three elements worthy of note: in the first place, through the painting of Dom Miguel de Castro, emissary of Soyo (a province of Kongo) and through the relevant historical documentation displayed (namely correspondence between the Kings of the Kongo and the Holy See), it places the Kongo Kingdom in the full swing of the 17th century, amidst the most significant inter-state relations of the time, or in other words, at the epicenter of the first globalization known to humanity.

Image Credit: The Met

Secondly, executed in a delicate manner, and in a way that runs against the tendency predominant in other exhibits and to what we see in anthropological and ethnological studies, the show transfers our attention – that of the perception of our current moment – to the pomp and splendor of the Kongolese Kingdom and Society through a presentation of little known luxury textiles, simply displayed and demanding more systematic study. In contrast to the internationally known Kuba cloths, we know little about the importance of textiles in Kongolese society and culture: if we were to study them perhaps we would enrich our knowledge of the Kongo Kingdom and the relationships, for example, that its elite had with European upholstery making in the period.

Thirdly, without a doubt, the series of powerful figures, Nkisi Nkondi Mangaaka, occupy a central place among the collection of 146 pieces that comprise this exhibit, organized in three galleries, and displayed against a background of a deep indigo color. Used in mytico-religious ceremonies, the Mangaaka evoke the power of the ancestors and the manner through which they manifest in rituals that contribute to consolidating or transforming the becoming of an individual or a specific collectivity.

“Kongo: Power and Majesty” is timely for arriving at a moment in which the world needs to know more about this kingdom and in which the Angolan Ministry of Culture, through the personal involvement of its Minister, Rosa Cruz e Silva, via its project “Mbanza Kongo, a city to unearth,” has undertaken great efforts to put Mbanza Kongo on the world map of the Cultural Patrimony of Humanity. The Angolan state is acting to protect this historic place.

At the same time, we should keep in mind the announcement of the Sindika Dokolo Foundation (based in Luanda) regarding the restoration of two Mwana Pwo pieces during the III Luanda Triennale as well as other declarations of its founder. For example, in an interview with Raphael Minder of the New York Times this summer, Dokolo advocated the return to the continent of classical/traditional African art pieces and artifacts. This is a position that has gained political ground in recent years (possible objections, such as the creation of adequate museological conditions to receive the objects, are minor or, in any case, can be resolved).

But perhaps what we need to do in these circumstances and given the complexity of the question, which should have neither to do with celebrity or private agendas, is unite our forces to produce more encompassing solutions. Such solutions could include an analysis of the problem, for example, by the UNESCO Committee for Cultural Patrimony (and related institutions pertaining to member states). Every African country, taking into account its specificities, could develop potential positions for the state to take either individually or collectively (with other member states). Once an institutional front with real power exists, only then can we talk more of the magnificence of Angolan art, or African art in general. Such important questions should not be left in private hands, no matter how noble the end.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers