Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 324

October 29, 2015

The tyranny of distance, up close

Remember #Kony2012? In March 2012, US-based humanitarian organization Invisible Children (IC) launched its global internet-driven campaign to “make Kony famous.” Joseph Kony, the elusive leader of the insurgent Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), had been at war with the Ugandan state and its army, the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF) since the late 1980s.

The LRA abducted hundreds of boys and girls in their frequent attacks on northern Ugandan communities, pressing many of them into service as soldiers and workers, and forcing many into sexual relationships with its men. According to escapee testimony, Kony himself had numerous child “wives” at a time. Indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity and war crimes in 2005, Joseph Kony remains at large, perhaps ill, perhaps somewhere in South Sudan. After receiving blistering criticism about IC’s methods and finances, and after a very public breakdown by its founder and main spokesperson, Jason Russell, the organization announced in December 2014 that it would hand its operations over to a much smaller, local Ugandan staff later this year. For an instant though, IC succeeded in making Kony famous.

The viral success of IC’s fundraising and public awareness campaign was the result of brilliant guerrilla marketing that sold a powerful idea: ordinary people around the world (and some extraordinary ones too) could and should act to bring an end to Kony’s atrocities. This campaign’s manipulative appeal to knee-jerk white savior impulses generated an astonishing outpouring of support. But IC’s call to capture Kony was, at its heart, also a call for US military intervention in East Africa. In the name of capturing Kony, US troops and aircraft currently operate alongside African Union and UPDF forces in Uganda and a number of other nations with contiguous borders. It is worth noting that Uganda has long occupied a special place in US security thinking, damn the consequences. This latest expansion provides new cover to a longstanding military alliance.

#Kony2012’s story of villainy and heroism in Central Africa is but one chapter in the larger story of the United States’s rapidly expanding military interests and presence on the continent. Over the last few years, more and more information about the increasing presence of US troops, equipment, and bases across Africa has emerged. This “new spice route” reflects the substantial progress the US Africa Command (AFRICOM) has made since its founding in 2006 in establishing infrastructure for a range of operations, including military training exercises, humanitarian interventions, and new logistics support bases.

Earlier this month, the online national security journal The Intercept published a series of reports, collectively referred to as “The Drone Papers”, which are based on a “cache of secret documents” obtained from a government whistleblower. Nick Turse, Jeremy Scahill, Cora Currier, and a number of other investigative journalists who have long followed US covert military activities overseas have analyzed these documents and now are beginning to publish their findings. These journalists’ chilling reportage shows that the US is undertaking significant investment in building and sustaining a base infrastructure for drone operations in East Africa, especially in Djibouti, a tiny country on the horn of Africa. Why?

AFRICOM calls it overcoming the “tyranny of distance”—that is, finding ways to overcome the vast distances involved in conducting operations in Africa, especially given the continent’s “underdeveloped” transportation network. Applied to the realm of militarized humanitarian operations, such as the deployment of a small force to assist in the fight against Ebola last year, overcoming the tyranny of distance sounds innocuous enough. Applied to the context of East Africa however, where US concerns about the activities of Al-Qaeda, Al-Shabaab and other extremist organizations in Somalia and Yemen, this phrase takes on more ominous tones. The hardening of bases in Djibouti and elsewhere serve AFRICOM’s goal of using drones to act on “kill lists” not from the safety of the United States, but instead from forward operating bases that dramatically cut response times, enabling rapid strikes against designated human targets that have been approved at the highest levels. #Kony2012 called for US military intervention in East and Central Africa to conduct a manhunt for Joseph Kony. As Joshua Keating noted in a March 2012 Foreign Policy blog post critical of #Kony2012,

One of the biggest issues with a simplistic ‘Stop Kony’ message is that discussions of Navy Seals or drone strikes are inevitable when patience runs out with Ugandan-led efforts.

A mere three years later, it seems guaranteed that many more manhunts of a different order are in the offing. The US government no longer needs a humanitarian cloak to mask its imperial purposes as it digs in to Africa as its newest frontline in the war on terror. Inevitable indeed.

October 28, 2015

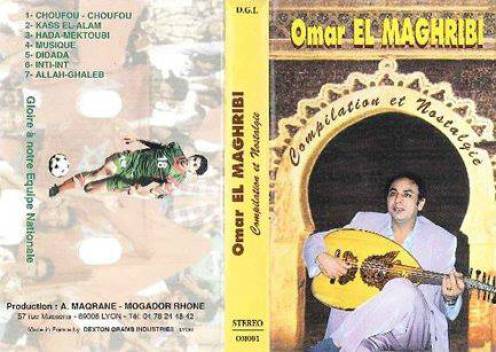

The Maghrebi experience in Lyon, France as told through cassette tapes

Lyon is an industrial town in the east of France not known for its immigrant culture or for being near any ports of entry. However, many of the Maghrebi immigrants from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia specifically, came to Lyon to work in coal mining or industrial factories. Between the 1970s and 1990s, this generation gathered in cafes and created a vibrant music scene that was turning out hundreds of small-run cassette tapes. The three CD set Maghreb Lyon, released earlier this year on archival French record label Frémeux et Associés captures the output of the North African musicians that made this city their home then.

The music on these tapes is raw and full of life. It contains angst about the plight of North African immigrants in French society. The 80s and 90s were a tough time for North African communities in France. Recognizing the context of this music, Place du Pont Productions and The Center for Traditional Music in the Rhône-Alpes split the CDs into themes. Disc 1 is “Exile and Belonging”, Disc 2 is “Political and Social Chronicles”, and Disc 3 is “Love, Friendship, and Betrayal”. It’s an interesting way to compile some of these recordings, creating a series of historically contextualized concept albums.

The following is an interview with Péroline Barbet of the CMTRA (Center for Traditional Music in the Rhône-Alpes) and Omar El Maghrebi, a Moroccan artist and long-time Lyon resident who’s one of the key artists on the recordings.

Lyon’s not necessarily known as a key place in France for immigrants, or not like Paris and Marseille. What brought people to Lyon? Why Lyon?

Péroline Barbet: It’s economic factors that move people, but in the case of Algeria, it’s also political factors. Lyon is an industrial center, which brings people for work. It’s also a big city and a very culturally diverse city that has welcomed different waves of immigration. Like everywhere else in France, Maghrebi immigration is key, but there are also Armenian, African, Asian immigrants now. Lyon is also a zone of passage for immigrants. A lot of immigrants arrive, in the case of North Africans, at Marseille, and when they can’t set down roots in that city, they head North for Lyon or Paris. I’m not an expert on the history of North African immigration, so I can only give generalities, but it seems like most of the music industry and the cassette tapes in Lyon originate in the East of Algeria. The city of Sétif in particular, and so the most represented genres–genres are not well known in France–are the Sétifi and Chaoui genres of music.

What is Sétifi and Chaoui music? How would you describe this music?

PB: Chaoui music is berber music from the Eastern Aurès Mountains, and Sétifi music comes from around the town of Sétif. They both come from the folklore of Eastern Algeria; music for dancing and popular music.

What are the instruments used? Is this music more folkloric than, say, Raï, which uses a lot of electronic instruments?

PB: For chaoui music, voice, flute (gasba), oboe (zorna) and percussions (bendir) are typical, and sometimes the violin. But these traditional musics, mostly rural, have been mixed in France with electric music and new instruments, and reinvented. That’s why we called them on the CD “urban popular music from immigration.” There is also the Malouf Arabic-Andalusian music from Constantine, Algeria, that is more meditative, and is represented by the artist Salah El Guelmi on this compilation. Moroccan chaabi is represented by Omar El Maghrebi.

Péroline, where did you find the cassettes that made up this compilation?

PB: The project comes from a collection of cassettes that was gathered by a Lyon musician who was also a sociologist, Richard Monségu. In the 90s, he did sociological fieldwork around the musical cafes in Lyon. He studied the cafés and the communities of musicians who played in the cafes. During his fieldwork, he collected over 50 cassette tapes. Once his work was finished, he became a musician and he makes world music today. The cassettes lay dormant at his place. One day, he came with these cassettes to the CMTRA (Traditional Music Center of the Rhônes-Alpes Region). For an event in 2009, we created a little audio documentary around these cassettes, and I got a chance to discover them, listen to them, also to look at them. The covers of the cassettes showed interesting sides to the music as well. At that time, I saw that there was something interesting we could do with these cassettes. What interested me was the unique sound of the cassettes; it’s a very raw sound that is very symptomatic of the 80s. There are a lot of surprises, a lot of special moments that you wouldn’t find on a more planned-out recording by someone from outside the culture. Once I started working on this I saw that it was an enormous project. We had a couple hundred of these cassettes, but there are thousands that were published by the Lyon record labels, stores, and distribution centers. Lots of these cassettes were recorded with musicians from Lyon, but a large part of it was recorded with singers from Paris, Marseille, and stars from Algeria and Morocco who had come to Lyon for a show or for a wedding party. These stars recorded in Lyon studios while they were here and the next day the cassettes were pressed, distributed, and sold in a very rapid market. It is an economy that takes advantage of these circumstances and that establishes itself very quickly according to what’s going on at the moment.

But you didn’t put the famous musicians on this compilation?

PM: The goal was mainly to work with local resources. I decided to focus on the local musicians where music wasn’t a profession; they’d record and perform after hours from their day jobs. Workers by day, musicians by night, one foot in both worlds, the musical world and the factory.

I have some questions for Omar… Omar, you live in Lyon right? Where are you from originally?

Omar El Maghrebi: Yes, of course I live in Lyon. I’m from Morocco originally, from the South, from around Agadir. I go back every two or three years, depending. I’m always in contact with Morocco.

A lot of the musicians on the compilation come from Algeria and Tunisia. Were there many Moroccans in Lyon at the time?

OEM: There’s more of an Algerian community than a Moroccan community in Lyon. There’s a lot of people from the East of Algeria, as Péroline mentioned. There are more Moroccans in the Saint-Etienne region, because of the [coal] mines. So the Moroccans worked there, but now we’re starting to see some Moroccan communities in Lyon.

Are you playing Moroccan music on the compilation?

OEM: I do a little bit. Mostly what I do are topical songs. I don’t do covers, so these are original. I do a bit of research, and I write in between the Moroccan and the Algerian styles, I try to move between the two. I don’t play typical Moroccan music, I try to blend the two.

In this cassette era, were you playing in bars or shops?

OEM: I started performing in the bars in 1976. I write these songs on themes that correspond to the sociology of immigration. What we live between us. I’m creating an image of the Moroccan or Algerian immigrant here, and sending it to people back home.

What inspired you to do this? To be a kind of musical journalist?

OEM: First off, I loved music since I was a child and played percussion. I started at 13 years old. I played Moroccan bass, I played the darbukka, but I sang a bit too. I loved singing and once I got to France I started working, and started playing for evenings with my friends in the housing unit where we lived. We were all bachelors, and Saturday afternoons we’d pass the time hanging out and playing music. Then I met an Algerian musician, a guitarist. He was playing at the bistro in Vénissieux, a suburb of Lyon. He was playing his guitar by himself, and I started to sing and he would accompany me. We had a small group and started playing out and that’s where it all started…

But the inspiration for the songs… I studied a bit of Arabic in school, and I liked philosophy. My first inspiration was to write the song called “Ma mère” (My Mother). I’d met an older Algerian singer who was a nurse in a hospital in Lyon who sang songs that were like recitations. When I met her, she said “Why don’t you make your own songs?” And that’s where I wrote my first song.

Where did you learn to play the oud?

OEM: I started learning the oud afterwards. I was playing the bendir [a North African frame drum]. Living in Lyon, I had the chance to go often to Marseille or Paris, and I met other artists. I met a Moroccan violinist who played in the cabarets in Paris. In Lyon, we didn’t have cabarets like in Marseille or Paris. This musician told me I should learn the oud. I worked on learning the oud while also working full-time at my job.

What was your job?

OEM: I work in a factory. I’m an industrial worker. I came from Morocco to work in France.

Can you talk about your song, “J’en ai marre” (I’m Fed Up)? I loved this song and the lyrics are in French and Arabic, but what is it talking about?

OEM: The song “J’en ai marre” is a song that I wrote in the 90s because the Maghrebi community in France, at a certain point, was the target of all the political parties. Immigration became a bit of a problem in France, and everyone was talking about it. Then we had the Front National [French extreme right-wing political party] talking about immigrants, and other politicians, and I was inspired to write the song because there was too much crap being said. People were getting killed. There were a lot of problems for immigrants like police stops… I was fed up. I was fed up because I was a factory worker. For the immigrants there was nothing to do but go to work and then go home. When we went outside, we’d get stopped by the cops. After writing the song, in 1997, I had two cops who stopped me at a red light. I didn’t see them coming. They pointed their guns at me and wanted to arrest me. And that was after the song! You see, these kinds of things happened at that time. Lots of police stops, and because of that I wrote the song, just to give an idea of what it meant to be an immigrant in France.

Do you think that all those police stops at that time created a kind of insular community? Because people were afraid to go out?

OEM: The problem wasn’t being afraid to go out, the problem was being profiled. We weren’t afraid of the laws or the rules, it was that we were being profiled.

Targeted, you mean?

OEM: Yeah, exactly. That’s the word. Immigrants were targeted, they became a target for everything…

PB: Can I add something? What’s interesting about these three CDs is that they’re thematic. It’s true that love songs, party songs, and songs of exile tied to immigration are themes that run through immigrant music in France and Maghrebi music since forever, or mostly in the 1930s. On the other hand, the compilation shows that in the 80s these community-based singers started taking a position and denouncing the injustices, humiliations, and mounting racism in France. There are two factors in play, first an exasperation at not being recognized (these artists had been around since the 70s), and then there was a more tolerant political context because of the years under [French president François] Mitterand starting in 1981, which allowed a lot more tolerance. So they started allowing more, and then these songs came out. Omar, in particular, was a key songwriter. There was also a singer from Saint-Etienne, Zaïdi El Batni. There were a lot of very virulent political songs. From this came a movement of French rock coming out of immigrant communities that wasn’t like Rachid Taha. The music was different; we could say that they invented a kind of music that came from here, from Lyon.

Do you think that things are better now in France? Is there still a target on North Africans in Lyon?

OEM: The target will always be there… [long pause] The target will always be there.

So there hasn’t been much change, you think, since the 90s.

OEM: It’s up to the people themselves to change. Don’t wait for society to change, because society is waiting for you to come to it. Our generation, we have kids, and these kids are now 20, 25, or 30 years old. It’s different. So, our generation, we see differently. And the other generation, they can’t know what’s going to happen and they have a different mentality. That’s why the immigrant will always be sad and unhappy, because the idea of France that he has when he arrives will be changed by what society has in store for him. People are fragile, dear friend. They have their ideas, their structure, and then things start to crack. The child passes through the crack, the father passes through, the mother passes through, and afterwards, everyone’s trying to find themselves. Despite all this, society hasn’t changed. It’s too bad. It’s too bad because the sadness the immigrant felt at 25 or 30 years old comes back when he’s 60, even when he’s retired, because he couldn’t put anything aside to provide for himself. Target or no target, everyone has to create their own environment themselves.

Omar el Maghrebi

Are you still playing music, Omar?

OEM: Less and less, because traditional music has less influence today. Since the arrival of pop, music is more for the youth these days, which is normal, but for me I haven’t changed directions. I stayed with traditional music, it doesn’t go very far, but it’s what carries me, you see what I’m saying? I didn’t get into techno music. I try to modernize my music a bit to satisfy people, but not that much because I want to stay in my idiom. I think I’ll get back into it when I retire, and I’ll take up the traditional music again.

PB: Omar’s part of the group of artists who resisted the synthesizers, the drum machines, the wave of modern music that the younger generations in the 80s rode on. There are a couple recordings like that on the same disc that has the song “J’en ai marre.” In particular, that song of Omar’s was recorded with the sound of that era, with reverb, with a drum machine, and all that. But, Omar explained to us the other day that this song was sped up by the demands of 1980s dance music because the producer wanted to get people dancing. That’s what producers of that era wanted. For Omar, his thing is that it’s all about the message, the lyrics, and this isn’t the case of all the other singers, but the texts of his songs make you think.

In any case, I can say that the singers today, the singers who I could meet with who still live in Lyon, all say that it’s not like it was before. It’s a recurring discourse and it’s true that the context isn’t the same anymore. There’s no more music in the cafes, because the cafes don’t play the same role of a meeting place for the community. The support for the music has evolved and the public has evolved also. The young generations speak less Arabic, so they don’t always understand the songs. The themes of the songs don’t concern them anymore, because these songs about the first wave of immigrants don’t don’t reveal their reality anymore: each generation has its own problems and challenges. On the other hand, it’s starting to come back because this CD came out in May 2014, so it’s starting to circulate a bit. I’m starting to meet young people in the second or third generation who grew up with the cassettes and who knew the singers. These people tell me how much these tapes mean to them: “This is my heritage.” These old singers didn’t leave many traces. That’s why the cassettes are so important, they’re supporting the memory and history, and they’re witnessing the past. I hope, modestly, that this will contribute to renewing and bringing back an awareness of the heritage, of the story of this immigration.

OEM: In any case, for my part, I’ve been playing at a restaurant in Lyon with my oud, and people are starting to come by to see me. They’re interested in the words, in the real music. People today are so overwhelmed, and they want to come back to reality. It’s difficult, because there are a lot of things that don’t work anymore. The new generation speaks French. You have to speak to them in a bilingual Arabic and if you sing in this language, you have to sing a lot faster, to do a bit of rock n’ roll. That’s the way it works with them, and that makes sense, because it’s their time now.

PB: The other thing about these old songs is that they use a lot of words in dialects. They’re very hard to understand and translate, because you’ll have these songs in Oranais [from Oran in Algeria] or Sétifi, with words in Chaoui, so much so that when people listen, they’ll understand some singers, but not others. It’s not only a musical diversity; it’s a diversity of languages and expressions.

OEM: That’s what the singers from here did; they were singers from various regions. Each one sang in the style of his region, with his own accent and his mannerisms. You see, if you’re Moroccan and you sing in a style from the Casablanca region, the people of Casablanca will hardly understand, and then the people from Agadir in Southern Morocco, won’t understand anything…

PB: That’s what happened in the cafes. All these regionalisms started mixing together, and with French culture as well, in the same places in Lyon and all of a sudden started influencing and changing each other. The music got blended together and the languages too. As the raï singer Rabah El Maghnaoui told me, as we were speaking about these interactions, “You spend some time with somebody, and you slowly become like him!”

*This post originally appeared on the author’s Kithfolk Blog. The interview was translated from French by the author and his father Louis Léger.

Mother of the Nation

No victory was achieved for the #Feesmustfall campaign last Friday. Let’s be clear about that. No fees have fallen. There is nothing to celebrate or get excited about. Fortunately, young people are not stupid nor naive as I discovered for myself.

My intention of going to the march at the Union Buildings was to pledge solidarity as a parent and to observe how the politics played itself out at these marches.

I already suspected that there was more than meets the eye with the [ANC-aligned—Ed.] South African Students Congress (SASCO) being in the leadership of these marches. Then there was the possibility of the ruling ANC’s leadership influencing the whole process to make sure that it is quelled down, and or used for their benefit in the run up to the elections.

I was alone, Smanga couldn’t come with this time. I was almost discouraged, but a friend encouraged me and said: “Diks you must go, this is likely to be the biggest march and most intense march to the Unions buildings since the 1956 Women’s march.”

When I got to Pretoria station, I found three young people who I befriended and went to the march with and spent the day with them. Two of them were women. All third year students. Samantha Sangqu is a law student at Wits University, Keabetswe Monyaki is doing a business degree at the University of Johannesburg, and Kgotso Mashego studies International Relations and Economics at Monash University. From a “social science point of view,” the three served as a good “sample” for my research observation.

When I saw them they were getting frustrated since they didn’t know directions to the park. They welcomed my support as a parent, saying “Thank you for bringing us here.”

The youngest of them, Samantha, is as short as me, we were both carrying heavy backpacks and both also fell in the near-stampede at the Union Buildings. I immediately took a liking to her. We looked out for each other throughout the march. She would look back constantly as we were marching or running and say “Ma are you there? Ma are you okay?” I just adored her. The boy, Katlego was so gentle and took responsibility for our safety, all three of us. He would run to the front, then come back to make sure that we are close to him. When he realized he was walking too fast leaving a distance between us, he would automatically slow down. I assured him that I’ve become so used to these marches and relatively fit as I’m runner so he didn’t have to worry about me.

When we got to the park, they were asking each other “where is the leadership?” They explained to me that every time they gather they’re first briefed about the goals and intentions for the day so that everyone can be on the same page. Sometimes they are gathered according to their universities, UJ and Wits University in this case, and emphasis is always placed all the time on good behavior and how important it was to make sure that the marches were peaceful. I liked that.

Immediately we got to the park, they observed that some ANC youth were wearing their party colors. There was even a woman selling ANC t-shirts and caps and other party trinkets. The students complained to each other, saying that that was not right because they have been told all the time “no one should push their party political agenda.” They expressed serious discomfort. Samantha stopped a mother because she saw her yellow outfit. She wanted to ask her what she was doing there in an ANC outfit. When the lady turned, my companions realized it was a Kaizer Chiefs colors she was wearing, they let her go. They laughed at this.

The Wits University busses arrived and the march began. Obviously there was no briefing this time, unless maybe it happened in the busses. For a moment I thought the march appeared uncoordinated because we started moving without anyone addressing us. Along the way I was learning the songs. Same old struggle songs but customized to their new struggle. The students added some steps, which added a nice flavor. I was enjoying myself.

There was solidarity expressed by people along the way, ordinary citizens, people in their cars and taxi drivers hooting, workers from buildings—especially in the government offices—others on rooftops with placards bearing #FeesMustFall messages.

Wits Student during Protest

When we got to the Union Buildings, we could immediately see that there was a problem, with dark smoke coming from the gardens. These kids got worried. When we got closer there was a group kicking toilets and getting all rowdy. There were comments from the crowd that “those must be the Pretoria students, we never do these kind of things.” The ones I was with said “Ma we have been so disciplined all this time. Even at Luthuli House [the ANC headquarters where Wits and UJ students protested earlier that week-Ed.] we were well behaved. This kind of thing is not what we signed up for.”

We briefly got inside the yard but I advised that we must immediately get out because otherwise when the police start shooting we will be trapped inside. We got out and found the majority of the group we came with, still outside the gates.

My companions related to me how they were surprised when they got to Luthuli House to find a stage erected and ANC leadership ready to address them. I asked them if they intervened and instructed their leadership while they were there that Gwede Mantashe [ANC Secretary General] and Blade Nzimande (Minister of Higher Education] should not address them. They said no it was agreed from the onset before they left that when they get to Luthuli House they don’t want to be addressed by any political party leadership, as that has always been their consistent position. They simply wanted the ANC leaders to receive their memorandum. Of course the way they insisted that Mantashe and Blade get off that stage was really humbling for the ANC leaders.

Students arrive at Luthuli House.

Make no mistake, Mcebo Dlamini is a popular and good leader. I just hope and pray that he does not get corrupted, if he’s not already. I say this based on these young people’s response when they saw him in the crowd when we were closer to Union Buildings. They were like “Oh, there’s Mcebo” with much excitement, all three of them. I watched their faces and saw relief when they saw him. That for me is a sign of a leader who is trusted by his followers. He enjoys support and credibility. I hope he does not get to abuse it for selfish interests. His charisma of course can either be a good or bad thing for the student struggle going forward. I’ll leave it there for now.

What I liked with what Mcebo and fellow leaders did was the strategy they implemented to avoid being part of the rowdy crowd and I guess also being associated with the violence. He led the march, obviously dominated by Wits and UJ students to march in the street up the road, away from the chaos. So we did not enter the precinct of the Union Buidlings. This happened almost automatically. One could see that this was a tactical retreat implemented by a thinking leadership. I told these kids that I was highly impressed by what I was observing. Clearly there was panic, this was just after we fell and there was almost pandemonium and I got seriously worried about our safety. I was not sure how the police were going to react to this madness that was unfolding there, and the helicopter hovering in the sky was also adding to the drama. Being led away came as a relief.

As we were led up the street, momentum sustained with song and slogans (“Sizabalazela ilizwe, lokhokho bethu sizabalazela ilizwe”), just to make the marchers feel that they were not isolated from the group that was inside the gardens. When we got to a safe distance up the road, we were kept waiting without anything said. Obviously everyone wondering if President Jacob Zuma had come out yet to receive the students or announce the outcome of the meeting. It was what happened next excited me.

Police Mobilize to stop the Students from Crossing the Bridge

There was a young lady who stood in front, I couldn’t see her, but apparently she was wearing ANC outfit. No one could hear what she was saying because she did not use a loud speaker. One of the girls who was standing close to us said: “But who are these ANC people who keep addressing us? We don’t know these people, who are they?” That for me was a clear indication that these kids will not be fooled by anyone. They are intellectuals, they are educated and unlike us their parents who have allowed ourselves to be fooled for 21 years, they will have none of that, no one will pull wool over these children’s eyes. Let them keep trying if they wish, they will discover the hard way.

The young people also said to me—which is another thing I so desperately wanted to hear—that they have been encouraged all this time during the protest that they must continue studying hard in preparing for exams. Sam said: “Anyone who has not heeded that call and not studied, I feel sorry for them” (By the way, she had expressed her views about the treason charges against the Cape Town students. So when she said she was studying law, I responded: “Oh that explains why you sounded so strongly about those crazy charges.”

Before I left, Samantha said “You know mama by the time we are done with this campaign, Blade Nzimande will not be the Minister of Education. How dare he say ‘Students must fall’?” I just teased her and rubbed it in by saying “Really mama, did he really say that?” She responded with a strong tone, frowning “Yes Ma, he said that.” I smiled, and on that note I thought I had seen enough and happy with what I saw and heard. President Zuma had not yet made his announcement about a zero fee increase for 2016, but I was satisfied. I bid them farewell with hugs of course and got a tight hug from Samantha. I then took a long walk from there, through Arcadia to Hatfield Gautrain station, thinking hard about the future of this country, which I believe will be in goods hands, no doubt about it.

Guatemala’s new president: a blackface star backed by the military

Jimmy Morales, a Evangelical Christian and a former TV star who has never held public office, was elected as the new president of Guatemala. In the second round election held on Sunday, Morales defeated Sandra Torres – the wife of former president Álvaro Colom – with 68% of the votes.

The president-elect, who defines himself as an “Evangelist theologian,” ran on a very conservative ballot, supporting the death penalty, while opposing same-sex marriages, abortions and the legalization of drugs. He also sought to rally around nationalistic sentiments. He was often seen wearing a Guatemala National Soccer Team jersey at political rallies, and spoke about annexing an area comprising of most of neighboring Belize (which Guatemala has claimed since 1946).

Con una playera de la Selección de Guatemala se presenta Jimmy Morales a dar conferencia. pic.twitter.com/RD0PLIEJRr

— Glenda Sánchez (@gsanchez_pl) September 7, 2015

Bueno: Jimy Morales A RECUPERAR BELICE Se ha dicho tienes que Cumplir lo que has dicho BELICE es GUATEMALA …… pic.twitter.com/qrCImNnpt5 — victor abril (@victorabril557) October 26, 2015

But last week’s vote had little to do with the candidates’ ideological positions. Morales campaigned under the slogan “Not corrupt, nor a thief,” and positioned himself as “the outsider” candidate. This was not a minor feat, as creating some distance from the established political class of the country was crucial to defeat win these elections.

Just last September, amid mass protests opposing him, then president Otto Pérez Molina was stripped of his immunity, forced to resign and sent to jail over a corruption scandal. Morales, who had been campaigning since last year, had a surge after Pérez’s resignation, as many people preferred to vote for a self-styled non-politician than for a former First Lady.

But Morales’s party, the National Convergence Front (FCN) is linked to Pérez’s Partido Patriota and, as InSight Crime reports, it “was formed in large part by former military personnel from the right-wing Guatemalan Military Veterans Association (Asociacion de Veteranos Militares de Guatemala – AVEMILGUA).” These are the same military men who,according to The Nation promote “impunity for past and contemporary military abuses.”

So Morales just might not be the independent leader Guatemalans were looking for. And, since only 35% of registered voters in the country actually cast their vote last weekend, his presidency might be just as frail as his predecessor’s.

It won’t be helpful for the president-elect either that the foreign press and public have been taking note of his troubled relationship with the different ethnicities of Guatemala.

Morales rose to fame by starring along with his brother Sammy in the TV show Moralejas, in which he played, among others, a blackface character nicknamed “Black Pitaya”:

Morales has also been criticized by indigenous groups for his portrayal of them, and has been iffy about the genocide of Ixil Maya people during the country’s long civil war.

What’s more, Morales’s right-hand man Édgar Ovalle Maldonado, a member of AVEMILGUA, was accused by NSA documents of being part of the Army’s Ixil Special Force Task in the early 80s. During that period, thousands of Ixil Mayans were killed, tortured and raped — 77 massacres were recorded. And although Ovalle has not been linked to these crimes, his presence in the government might influence how future inquiries into these events unfold.

Morales will begin his four year period January 14, when he can begin to prove if he is actually the anti-politician he claims to be.

*This article was originally published in Slant. Follow Latin America is a Country on Twitter and .

October 27, 2015

The Permanent Exile

The Pan-Africanist intellectual and journalist Bennie Bunsee (79) passed away on October 10th in Cape Town, the city where he lived and worked since he returned from exile after South Africa’s first democratic elections.

I was part of his Cape Town family. This ‘family’ was not related in the strictest sense, but gathered every now and again, most often or not at the house of lawyer Shekesh Sirkar. It is a family steeped in argument and critique and unspoken yet registered love.

Bennie had close and loving relations with many more people. Just the other day Shekesh and myself went to a restaurant and the chef came over and asked Shekesh: “How is madala?,” only to be told he had passed a few days ago. The chef stood motionless, surprised, and we all communicated our thoughts of sorrow through our silence.

This was Bennie. A man of intellect, who comfortably interacted with the restaurant staff whom he met daily in Cape Town, choosing one restaurant and for months going to it night after night until he would move to another one. He would get to know the stories of the people he met. Often he visited restaurant staff or attended their birthdays or other important events, and got to know other family members too. Mostly, he interacted with young people. Bennie was ever the father figure. He advised the young about the problems and challenges they faced, and inspired them in so many ways.

Bennie was in permanent exile; he never really came ‘home.’ I do not mean this idea of ‘exile’ only in its negative connotation; exile can also be viewed as an important vantage point. This is the sense in which Edward Said used the term, meaning forever on the margins of the mainstream and convention, in between two societies, located on the border of multiple cultures. This location allows a certain vision of societies that lends itself to permanent critique and analysis. Bennie was our conscience – asking what we were doing ‘inside’ a society that failed in so many ways to realize the noble goals and failed to continue the moral fibre that motivated the struggle over many decades. His was a life of critique. His was a life of the conscience, serving as an uncomfortable mirror, especially for his more moderated comrades, but many others too.

I’ll remember his daily phone calls, which almost always deteriorated into heated argument, only to be picked up the following day as if nothing jarring occurred. He would begin again: “Thiven, the problem is that we never resolved the national question,” “Thiven the ANC is morally bankrupt,” “Thiven the whites still control the media,’ “Thiven what are you black academics doing at UCT the place is openly racist … black intellectuals are in crisis.”

His were declarative sentences, demanding response and analysis. The argumentative declarative claim came naturally to Bennie. Bennie posed his ‘hypotheses’ emphatically in an on-going conversation about fighting imperialism, colonialism and its legacies and about the failures in our struggle—failures in thought, practice, and strategy, failure’s to recognize and confront imperialism’s eruptions in our local context, and the need to expand our consciousness beyond the narrowly political. He never gave up. He was always searching for new sprouts of hope to renew older struggles: he was drawn to sources of opposition and new energies that would contribute towards a broader revolutionary campaign to break the links in the imperialist chain. He excitedly watched the protests of the Arab Spring, the WTO protests, those against BRICS and its new bank, #RhodesMustFall and current student movements, even the Economic Freedom Front.

His was a life of moving away and towards: leaving Durban, where he was born, for Johannesburg and Cape Town is a case in point. He loved that city and its people, but also was very critical of its politics and parochial local culture and never really felt comfortable to remain and take up permanent residence. Similarly, although he spent 30 years in London, he saw the UK for its racism and double standards. We can say the same about his relations to his family and his Cape Town friends – we knew Bennie and we also did not know him. Once you said goodbye and he headed for his car you did not know where he would go. Perhaps, this is what the Cape Town experience was for him, a running away, a constant discomfort, a kind of exile. By living on the margins he opened a space for permanent critique, that necessary honesty of beliefs spoken out aloud to all, regardless of the listener. This was how he loved and we loved him.

Go well comrade Bennie. Go home at last.

*This is an edited version of remarks Reddy made at Bennie Bunsee’s funeral service. Others who spoke at the service were Kwesi Prah, Simphiwe Sesanti and Richard Sizani.

October 26, 2015

You Want Another Rap, Uganda?*

I know I should open with an origin story about “Kanda [Chap Chap]” but I can’t actually remember why HAB and I decided to make a song about Chapati. Yet that is not such a jump from the overall goal we had – and continue to have – for our music: to play with people’s conceptions. But it’s hard to flip any conceptions without a sound, so we were very lucky to have run into Hannz Tactiq early this year. Hannz is a prominent Ugandan producer who has worked with artists from Chameleone to A Pass, and has serious talent in his fingers. We gave him an outline of the beat we had in mind. We wanted to create a song with a beat that made your head nod, a familiarity that would almost disguise our subject matter. Once you hear the bass kick off, and the claps start, your mind goes to a certain place. Maybe it’s Deuces in Kabalagala on a Monday night, or maybe it’s Fusion Autospa in Munyonyo, but either way we’ve taken you there faster than a boda.

“Kanda [Chap Chap]” is our first song, but it does a good job of explaining who we are as a duo. It’s a sound born out of nights out in Kampala and at home in front of TRACE. We reference M.I. Abaga’s “Bad Belle” in our chorus, we ride our three-wheeler through our video with K.O’s “Caracara” in mind, and we try and channel some Bobi Wine as we tell stories about life in Kampala. Like the Ghetto President’s “Kiwaani”, “Kanda [Chap Chap]” is light-hearted but we also use chapati as a way to discuss identity, migration, and pride.

HAB and I are both Ugandans with roots abroad, with HAB’s in South Sudan and mine in India. We play on that as he raps in a mixture of Nubi, Luganda, Swahili, and English, and I start my second verse with “I got the same history as chapati/origins of India but born in UG/rock brown skin but ndi munnayuganda/luyembe ko muluzungu ne muluganda.” The last lines are in Luganda and translate into “rock brown skin but I’m Ugandan/I can rap in both English and Luganda.” Our lyrics and choice of language are rebuttals of what Ugandan society expects of us – that someone with some South Sudanese roots is forever “Nubi” and that Indian Ugandans are actually just Indians in Uganda. Chapati embodies this as it’s something that many thought could only ever be understood as South Asian, but has very much become a Ugandan dish. What used to be used to eat your main dish is now it’s own dish. Only in Kampala can I walk up to a roadside vendor and order two chapatis as my lunch.

And then there’s our pride. There are a lot of artists in Ugandan hip hop, and even African to be honest, who rap in a manner that imitates the sounds of New York City’s HOT97 or Power105.1 and that’s initially who we were when we started this all a couple of months ago. But we came to a point where we asked ourselves why the two of us should try and sound like we were ‘repping the BX when we were sitting in Kabalagala. It’s not just that doing so wouldn’t be honest, it’s also that we would be coming up against one of the best parts of hip hop: local pride. You can’t separate Drake from Toronto, Heems from Queens, or Blue Scholars from Seattle. So we rapped like who we are in Kampala: two fools who know chapati. And that’s what we’ll keep doing.

*“You want another rap” refers to a meme remixing a famous speech of Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni. This is the latest post in our music series Liner Notes.

After the reawakening of South African student activism, where to next?

2015 has been the year for student activism in South Africa. These spaces have been reignited with a new sense of struggle, morphing and changing, exposing fault lines and new possibilities, and pulling the rest of South Africa along with them as they go.

This is a powerful time for South Africans. Across the board people are thinking society and resistance anew. The debates which unfold on social media are opening up new spaces to understand and challenge the operation of power in post-apartheid South Africa. The students demonstrate energized resistance to the forms of injustice they and others feel. They also represent a site of deeper intellectual engagement with present conditions of oppression and possibilities for resistance, and they are pushing the rest of society to do the same.

Until recently university student activism in South Africa was something that belonged to history. Students of the 1980s often juxtaposed their own memories of campus politicization with the student apathy of the post-apartheid period. This apathy broke loudly in March of this year as students across the county spoke out about the continued institutional racism they experienced demanding the removal of statues which symbolized the colonial past #RhodesMustFall. Last week students rose up once more, this time contesting the rise of student fees and inflated cost of higher education #FeesMustFall.

Thus far the protest against fee increases has galvanized an important unity among South African citizens who feel comfortable to get behind a movement articulated against government policy. However unity and equality are not equivalent and if unity trumps equality then it serves hegemonic ends. South African disgruntlement is complicated. It comes from many different sides and holds different interests. By comparison #RhodesMustFall has not received the same unified support as #FeesMustFall which indicates some of the broader fault lines that underpin the present unity. #RhodesMustFall challenges whiteness in South Africa, it calls into question continued institutional, symbolic and material racial privilege and this is uncomfortable for white South Africans. In theory most South Africans want racial unity. However the response to #RhodesMustFall demonstrates that when it comes down to dismantling the forms of inequality inherited from the past, the division in interests emerges. This pushes us to ask a more difficult ethical question: Are South Africans able to maintain their desire for unity in struggle when their own race, class or gender privilege is challenged for the greater cause of justice and equality?

As the student movements develop and deepen, South Africans will be challenged to work out where they stand in the unity/equality equation. Different struggles also hold different interests and these don’t easily align with one another. In developing the ideological muscle of the student movement, they will be challenged to hold different forms of injustice and inequality in their analysis- against government injustice, class inequality, patriarchy and racial oppression – at the same time. What will this look like? How will it rub? How will they knit unity and equality together in order to not hail some struggles and demonize others? Can the students and their supporters remain strong in their stand against injustice even when some forms of challenge are in direct confrontation with their own class, race or gender privilege in society?

In answering these questions, it may be useful to dust off some of the old debates that revolutionary theorists were thinking through during the anti-apartheid struggle. During this time similar questions were being worked out around the relationship between race domination and class domination. At the time the movement’s stance on this was articulated in the two stage theory of national revolution. This theory asserted that first a democratic society would be created to get rid of race inequality and then the class struggle would be waged.

In a sense the first stage was brought about during the transition to democracy. However, as these current student struggles highlight, neither race nor class based oppression was defeated. With the transition, this broader ideological dialogue was replaced with a depoliticized from of reconciliation race politics, which largely ignored questions of power and injustice on both counts. The new student movement opens up a space to rethink old ideological debates, which can in turn offer a more complex understanding of South African society and our present predicament. History has shown that a two-stage approach which puts one form of struggle before another can be easily co-opted. It is at the point of the rub (between race, class and gender politics) that the difficult issues present themselves. The key ways in which power creeps in under the guise of unity is exposed precisely in paying attention to the rub. As South African citizens get behind the challenges posed by the students, this presents an emerging potential to articulate new understandings of society. Hopefully this will be one which thinks through rather than silences the rub, and which aims not only for unity and reconciliation but also for justice and equality.

October 25, 2015

Watch our 11 minute film capturing the energies of #FeesMustFall in South Africa

You could hardly catch your breath last week with the #FeesMustFall protests in South Africa. For a while, after #RhodesFell, we feared that identity politics would swallow and spit out the loose agglomeration that was that movement (there is no national coordinating body; instead it has been led by a mix of campus organizations and the local or youth affiliations of nationalist or leftist parties). But the ability of students to find and develop “a theory to suit their times, capable of holding the contradictions of ‘born-free’ life, just as their parents practiced their theory of opposition to the realities of their lives” astonishes every day. Last Friday, South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma announced that there will be no fee increases for the next academic year, starting in January 2016. This was of course some kind of victory, but not all that students are asking. President Zuma’s announcement was silent about free education or the problem of outsourcing at universities. Neither did he address police brutality or the charges against students who were arrested. The students were not appeased.

Just read, for example, the Facebook post by Wits University SRC President Shaeera Kalla. She was quick to reassert the demand for free education and to link the struggles over fees to larger struggles over university governance and outsourcing: “Comrades we have neglected our mothers and fathers being abused at the hands of outsourced companies on our watch on our campus under our gaze. Every single day Mam Deliwe, Mam Zodwa, and Comrade Matthews and many others stood firmly with us against fee increases, what do we do for them?” We don’t know where these protests are going or whether #FeesMustFall has the potential to grow into a national movement beyond university campuses, That all depends on whether #FeesMustFall manages ideological and identarian politics, and, more importantly draws in other energies, organizations or groups outside universities into the struggle. What is clear, though, is that every time the government responds, the protesters up the ante. The young ones have been born.

In this eleven minute film, edited by Leila Dougan of our film unit, we’ve culled together images from the last week’s protests (the full list of credits come at the end of the film). Much of the coverage has focused on Johannesburg and Cape Town at the expense of provincial and “historical black universities.” This film lets students from Rhodes University, mostly women, articulate for themselves what is going on in this moment. Watch:

October 23, 2015

Zanele Muholi on her life’s work archiving black South African lesbian, gay, and trans people

Throughout the length of her career, the visual activist Zanele Muholi has worked with a clear sensitivity to the importance of positioning herself – and gay, lesbian, and transgender people as a whole – in the past, present and future of South Africa. Born in 1972 in the Umlazi township of Durban, she came to photography through an advanced course at the celebrated Market Photo Workshop in Newtown, Johannesburg in 2003. Within a year, she had her first solo exhibition. Since these beginnings, she has dedicated her practice to documenting and representing the multiplicities of black sexualities and gender within South African communities, with works that engage with photographic, video and sculptural installations. Most interestingly, the work for which she is best known, Faces and Phases, takes this mandate and houses it within one of the most traditional modes of photography—portraiture.

Unapologetically exposed and carefully composed, Faces and Phases presents a glimpse into a community violently silenced within the sociopolitical realities of post-apartheid South Africa. In each portrait, the subject faces the camera frontally, with an open and direct gaze. Captured with extreme clarity, sharp details and fine tonal range, Muholi positions each figure centrally—initiating a silent, but loaded conversation between the subject and the viewer. Through Muholi’s lens, one is privy to the undeniably visible beauty, elegance and dignity of those within this community, while also being forced to confront their collective invisibility within a homophobic post-apartheid South Africa. Currently arranged in a set of sixty, set to highlight the significance of the year 1960 in both African and South African history, this series of black and white portraits presents a nuanced exploration of black female lesbian and transgender subjectivity within the galleries of the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum. Alongside a thoughtful selection of other works from Muholi’s corpus, the exhibition Isibonelo/Evidence gives a broad survey of her work, while continually communicating the underling social force that central to her practice.

Image Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum

In an interview after the opening of Isibonelo/Evidence at the Brooklyn Museum (open until 8 November, 2015), Zanele spoke with Africa is a Country’s Remi Onabanjo about the social, historical and creative resonance of images, and how she considers her artistic practice a process of collective archive-making.

Remi Onabanjo: “Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence” is currently showing at the Brooklyn Museum. I’m interested in psychological and physical steps that led to the mounting of this exhibition in the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Why now, why there?

Zanele Muholi: You know I had to accept the Brooklyn Museum invitation, which just came at the right period in my life. South Africa is celebrating twenty-one years of democracy, so I think I’m celebrating my 21st birthday party [laughs]. It’s happy twenty-one for me, but particularly on a political level to be honoring democracy in South Africa from 1994 to 2015—that is a remarkable period, especially considering all the gains that we have won as the LGBTI community. Every time when I produce or when I respond to any call, I’m not only doing it for me, but I’m doing it for many other people who might not even imagine these spaces as possible.

I come to Brooklyn to create a space where queer dialogues, LGBTI dialogues that look at black people specifically in an America at the height of racism are very much needed. I’m also here also to activate spaces, to revive a dialogue within the context of feminist arts and make that clear within museums and galleries. Recently I received a link from one of my friends who shared a clip in which Michelle Obama responded to how museums are white spaces. I think that came at a very good period in our lives to think of who gets to be shown, and how those projects are exhibited, and who curates, and the decision making prior to those shows. That helps me think of where I am right now in my life when I am clear with my political agenda and I cannot dare to be silenced.

So you were really concentrating on this being an important time politically, for you, for South Africa, even for America, with the various shifts institutionally that are happening.

Yes absolutely. And also to start a discussion on the kinds of images that are traditionally being shown. So in my exhibition, it was important to include representation in the wedding pieces, or Faces and Phases, or even the beaded pieces that declare the headlines of hate crimes that have occurred in South Africa. I am hoping to break down those notions around what is to be seen and what is not. For me to bring the marriage footage to America was very important. When people write about Africa and South Africa, it’s like we’re not progressive. People like to write about negativity when it comes to Africa you know? So I think to bring that joy, to bring that love, those relationships in these spaces, which I could say are queer spaces because of the way of thinking and decision-making—that was all very important. When people are given an opportunity to write about South Africa, nobody could think of us loving each other, building families together, creating homes that make sense to us. So that was the major thing. I wanted to bring love into the space; I wanted to bring intimacy into this space. I wanted a lot of black people who come to this museum to encounter a lot of us, that’s why you have a number of faces and phases. I wanted to give hope to that young person, that young black woman, and show her that her wish to take photographs is possible. I want to encourage young artists to think of photography as a possibility, as work—to think of art for consciousness, and in turn, museums as spaces where we can carve a new dialogue that favors us, which is why the feminist center really meant something.

You raise a great point. I’m also interested in how you see the exhibition alongside the other shows that are up in the museum. For example, there’s the Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks show, there was the Kehinde Wiley show. Did you get a chance to see them?

I saw Basquiat, because I love him. It’s a pity that he died so young. But thinking of Basquiat, that he died at twenty-something, I’m reminded of lesbians that are being butchered in their twenties, you know? Who are killed in their twenties. And also to say that his show raises a lot of questions, like when and why an artists’ is work deemed worthy; really ruminating on the politics of being shown in such a privilege space. So I’m just thinking about this young man who never had an opportunity to enjoy…

The fame, the acclaim, the respect.

Yes, the recognition that he deserved when he was still alive. So that makes so much sense. And also the portrait, his portrait outside, when you are about to [enter the exhibition]. It looks so much like Faces and Phases to me.

Yes, very true. Because of its composition.

Exactly. This guy could be any participant in Faces and Phases. He could be from South Africa. He looks so much like us. That sameness you know?

Speaking of those portraits, you talk about the importance of knowing every person who you photograph and the importance of the relationship. It’s not just your role in taking the photograph, but the work being a product of a community. So that made me really interested in how you brought along the photographers that you work with to document your performance at the opening evening of the exhibition.

Not all of them where photographers, but I do travel with participants because these are the individuals who are my pride. When I look at them, I am reminded of the opportunities that were given to me and I want to share these opportunities. I want to give people a chance to speak for themselves, to speak about their work. And also to understand what does it mean to be documented in political senses and see where the work goes once your photo is taken, how people can be appreciated. Obviously I can’t take the whole 200-plus individuals which whom I work, but bit by bit. If I could make a difference to one or two or three people that I work with, then I’ll know that for sure I’ve achieved something.

And even with your book, Faces and Phases 2006-2014, you do that, and it’s a beautiful gesture.

Yes the book, every [participant] has a copy of the book. Because who else are we producing this work for? For me photography is about relationships, which are of course made by the people, so I have to take care of the people that made [them] and of those that are closest to them. I’m trying by all means to reach out to as many as possible, but then this has become a job. That means that I have to hire people in order for them to further document and collect more life stories, to have one of the richest archives to come out of South Africa that focuses on black lesbians and trans people as a matter of fact. We can’t blame others for our failures anymore, and if we do not understand, we need to make sure that we ask questions. So we are producing an archive, we are not collecting for the archive, and I’m stressing the need for togetherness. We need to work together. It’s one thing to say ‘yes, we can’—it’s another to take action. So we own it, we own it. I want to teach people about the need to ask questions, and also to share the work that they’re doing.

Your work is so deeply informed by your personal experiences and the experiences of your participants, yet it retains such a strong political slant as well. I’m interested in how you navigate that. How do you go from the personal to the political, the public to the private, in your work?

For me, what is important now is history—making and re-writing a history in which each and every body knows that they participated. When people say the work is beautiful, I say ‘okay thank you so much,’ but honestly this work should be beyond just beautiful. It’s powerful. It’s about claiming the spaces, taking back power, owning our voices and our selves and our bodies, without fear of being judged. Saying that we are here, without fear of being displaced. If you are fearful of something, you are continually carrying an inferiority complex—but if you say you are beautiful, it means that you could speak for yourself, you could speak you mind out; love yourself before expecting the next person to love you. This all means that I have to be self-conscious, minded with everything that moves, that’s before my sexuality, but my being in space.

Who inspires you? Who do you look to?

When it comes to Americans, Audre Lorde will always be my favorite because she informed a lot of us, gave us a new way of thinking. She was an out lesbian who was not scared to speak out her mind, who freed a lot of people’s souls to be open. She spoke of queer politics and pronounced the depths of lesbian intimacy in her work, risking her career of course—wow. I like those who break the sanitization a little bit and allow people a space to read and learn that this is beyond just art. If we talk about art and activism, if we talk about visual activism and sexualization of our bodies in space, it’s just a matter of fact. There are people who I’m doing this with, who are participating with me at a time at the height of hate crimes in South Africa. I pray often that one day they could see the contributions that they have made in history. Here you have the lesbian history archives, we are building that archive and we’re making sure that we’re penetrating all the galleries and museums, and do not limit our voices and our struggle on the street. But we’re taking on a different approach of strategies for that distribution, and vocalizing our issues. So we’re not playing games here. I’m not doing this alone.

Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence is on view in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center of the Brooklyn Museum from 1 May – 1 November, 2015.

An interview with Zanele Muholi on her life’s work archiving black South African lesbian, gay, and trans people

Throughout the length of her career, the visual activist Zanele Muholi has worked with a clear sensitivity to the importance of positioning herself – and gay, lesbian, and transgender people as a whole – in the past, present and future of South Africa. Born in 1972 in the Umlazi township of Durban, she came to photography through an advanced course at the celebrated Market Photo Workshop in Newtown, Johannesburg in 2003. Within a year, she had her first solo exhibition. Since these beginnings, she has dedicated her practice to documenting and representing the multiplicities of black sexualities and gender within South African communities, with works that engage with photographic, video and sculptural installations. Most interestingly, the work for which she is best known, Faces and Phases, takes this mandate and houses it within one of the most traditional modes of photography—portraiture.

Unapologetically exposed and carefully composed, Faces and Phases presents a glimpse into a community violently silenced within the sociopolitical realities of post-apartheid South Africa. In each portrait, the subject faces the camera frontally, with an open and direct gaze. Captured with extreme clarity, sharp details and fine tonal range, Muholi positions each figure centrally—initiating a silent, but loaded conversation between the subject and the viewer. Through Muholi’s lens, one is privy to the undeniably visible beauty, elegance and dignity of those within this community, while also being forced to confront their collective invisibility within a homophobic post-apartheid South Africa. Currently arranged in a set of sixty, set to highlight the significance of the year 1960 in both African and South African history, this series of black and white portraits presents a nuanced exploration of black female lesbian and transgender subjectivity within the galleries of the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum. Alongside a thoughtful selection of other works from Muholi’s corpus, the exhibition Isibonelo/Evidence gives a broad survey of her work, while continually communicating the underling social force that central to her practice.

In an interview after the opening of Isibonelo/Evidence at the Brooklyn Museum (open until 8 November, 2015), Zanele spoke with Africa is a Country’s Remi Onabanjo about the social, historical and creative resonance of images, and how she considers her artistic practice a process of collective archive-making.

Remi Onabanjo: “Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence” is currently showing at the Brooklyn Museum. I’m interested in psychological and physical steps that led to the mounting of this exhibition in the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Why now, why there?

Zanele Muholi: You know I had to accept the Brooklyn Museum invitation, which just came at the right period in my life. South Africa is celebrating twenty-one years of democracy, so I think I’m celebrating my 21st birthday party [laughs]. It’s happy twenty-one for me, but particularly on a political level to be honoring democracy in South Africa from 1994 to 2015—that is a remarkable period, especially considering all the gains that we have won as the LGBTI community. Every time when I produce or when I respond to any call, I’m not only doing it for me, but I’m doing it for many other people who might not even imagine these spaces as possible.

I come to Brooklyn to create a space where queer dialogues, LGBTI dialogues that look at black people specifically in an America at the height of racism are very much needed. I’m also here also to activate spaces, to revive a dialogue within the context of feminist arts and make that clear within museums and galleries. Recently I received a link from one of my friends who shared a clip in which Michelle Obama responded to how museums are white spaces. I think that came at a very good period in our lives to think of who gets to be shown, and how those projects are exhibited, and who curates, and the decision making prior to those shows. That helps me think of where I am right now in my life when I am clear with my political agenda and I cannot dare to be silenced.

So you were really concentrating on this being an important time politically, for you, for South Africa, even for America, with the various shifts institutionally that are happening.

Yes absolutely. And also to start a discussion on the kinds of images that are traditionally being shown. So in my exhibition, it was important to include representation in the wedding pieces, or Faces and Phases, or even the beaded pieces that declare the headlines of hate crimes that have occurred in South Africa. I am hoping to break down those notions around what is to be seen and what is not. For me to bring the marriage footage to America was very important. When people write about Africa and South Africa, it’s like we’re not progressive. People like to write about negativity when it comes to Africa you know? So I think to bring that joy, to bring that love, those relationships in these spaces, which I could say are queer spaces because of the way of thinking and decision-making—that was all very important. When people are given an opportunity to write about South Africa, nobody could think of us loving each other, building families together, creating homes that make sense to us. So that was the major thing. I wanted to bring love into the space; I wanted to bring intimacy into this space. I wanted a lot of black people who come to this museum to encounter a lot of us, that’s why you have a number of faces and phases. I wanted to give hope to that young person, that young black woman, and show her that her wish to take photographs is possible. I want to encourage young artists to think of photography as a possibility, as work—to think of art for consciousness, and in turn, museums as spaces where we can carve a new dialogue that favors us, which is why the feminist center really meant something.

You raise a great point. I’m also interested in how you see the exhibition alongside the other shows that are up in the museum. For example, there’s the Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks show, there was the Kehinde Wiley show. Did you get a chance to see them?

I saw Basquiat, because I love him. It’s a pity that he died so young. But thinking of Basquiat, that he died at twenty-something, I’m reminded of lesbians that are being butchered in their twenties, you know? Who are killed in their twenties. And also to say that his show raises a lot of questions, like when and why an artists’ is work deemed worthy; really ruminating on the politics of being shown in such a privilege space. So I’m just thinking about this young man who never had an opportunity to enjoy…

The fame, the acclaim, the respect.

Yes, the recognition that he deserved when he was still alive. So that makes so much sense. And also the portrait, his portrait outside, when you are about to [enter the exhibition]. It looks so much like Faces and Phases to me.

Yes, very true. Because of its composition.

Exactly. This guy could be any participant in Faces and Phases. He could be from South Africa. He looks so much like us. That sameness you know?

Speaking of those portraits, you talk about the importance of knowing every person who you photograph and the importance of the relationship. It’s not just your role in taking the photograph, but the work being a product of a community. So that made me really interested in how you brought along the photographers that you work with to document your performance at the opening evening of the exhibition.

Not all of them where photographers, but I do travel with participants because these are the individuals who are my pride. When I look at them, I am reminded of the opportunities that were given to me and I want to share these opportunities. I want to give people a chance to speak for themselves, to speak about their work. And also to understand what does it mean to be documented in political senses and see where the work goes once your photo is taken, how people can be appreciated. Obviously I can’t take the whole 200-plus individuals which whom I work, but bit by bit. If I could make a difference to one or two or three people that I work with, then I’ll know that for sure I’ve achieved something.

And even with your book, Faces and Phases 2006-2014, you do that, and it’s a beautiful gesture.

Yes the book, every [participant] has a copy of the book. Because who else are we producing this work for? For me photography is about relationships, which are of course made by the people, so I have to take care of the people that made [them] and of those that are closest to them. I’m trying by all means to reach out to as many as possible, but then this has become a job. That means that I have to hire people in order for them to further document and collect more life stories, to have one of the richest archives to come out of South Africa that focuses on black lesbians and trans people as a matter of fact. We can’t blame others for our failures anymore, and if we do not understand, we need to make sure that we ask questions. So we are producing an archive, we are not collecting for the archive, and I’m stressing the need for togetherness. We need to work together. It’s one thing to say ‘yes, we can’—it’s another to take action. So we own it, we own it. I want to teach people about the need to ask questions, and also to share the work that they’re doing.

Your work is so deeply informed by your personal experiences and the experiences of your participants, yet it retains such a strong political slant as well. I’m interested in how you navigate that. How do you go from the personal to the political, the public to the private, in your work?

For me, what is important now is history—making and re-writing a history in which each and every body knows that they participated. When people say the work is beautiful, I say ‘okay thank you so much,’ but honestly this work should be beyond just beautiful. It’s powerful. It’s about claiming the spaces, taking back power, owning our voices and our selves and our bodies, without fear of being judged. Saying that we are here, without fear of being displaced. If you are fearful of something, you are continually carrying an inferiority complex—but if you say you are beautiful, it means that you could speak for yourself, you could speak you mind out; love yourself before expecting the next person to love you. This all means that I have to be self-conscious, minded with everything that moves, that’s before my sexuality, but my being in space.

Who inspires you? Who do you look to?

When it comes to Americans, Audre Lorde will always be my favorite because she informed a lot of us, gave us a new way of thinking. She was an out lesbian who was not scared to speak out her mind, who freed a lot of people’s souls to be open. She spoke of queer politics and pronounced the depths of lesbian intimacy in her work, risking her career of course—wow. I like those who break the sanitization a little bit and allow people a space to read and learn that this is beyond just art. If we talk about art and activism, if we talk about visual activism and sexualization of our bodies in space, it’s just a matter of fact. There are people who I’m doing this with, who are participating with me at a time at the height of hate crimes in South Africa. I pray often that one day they could see the contributions that they have made in history. Here you have the lesbian history archives, we are building that archive and we’re making sure that we’re penetrating all the galleries and museums, and do not limit our voices and our struggle on the street. But we’re taking on a different approach of strategies for that distribution, and vocalizing our issues. So we’re not playing games here. I’m not doing this alone.

Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence is on view in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center of the Brooklyn Museum from 1 May – 1 November, 2015.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers