Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 282

May 18, 2017

Rosa Parks doesn’t live here anymore

Gesundbrunnen Wriezener Straße Rosa-Parks-Haus

Gesundbrunnen Wriezener Straße Rosa-Parks-HausSitting in a back room of the Babylon Kino, in downtown Berlin, we listened as Fabia Mendoza proudly rifled off the numerous front pages her husband, the artist Ryan Mendoza, had made since the sensational story broke about the relocating of civil rights icon Rosa Parks’ house. We had just watched her documentary The White House, the official backstory to the project. It presents a visual chronicle of how Ryan Mendoza entangles a journey of self-discovery into the current housing blight in Detroit, ultimately rescuing Rosa Parks’ house from the demolition list and re-erecting it in Berlin.

The documentary shows Ryan Mendoza initially traveling to Detroit to acquire a house to send to Europe for an art installation. To the artist’s complete surprise, the White House project generates a slew of negative publicity, casting him as a contributor to the blight and criticizing him for promoting “Ruin Porn.” After a second urban intervention, he gains notoriety as an artist working with blighted houses in Detroit, which eventually leads to Rhea McCauley, Rosa Parks’ niece, approaching him for assistance to save the house where Parks lived in the 1950’s from demolition. Despite initial reservations about playing into a “white savior” stereotype, he takes on the project, stripping the house, packing it up, and rebuilding it alone back in Berlin.

In the Q&A after the screening, a polished, clued up, and prepared Fabia Mendoza, spun the project’s positive media impact. She was at pains to dispel any lingering suspicions about her husband being just another white savior. Yes, there was some controversy, but what was more important was “awareness”, that everyone was now talking about Rosa Parks, she explained. Yet, we wondered, when did people stop talking about Rosa Parks?

The documentary carries the tension of a good story trapped in a short-sighted race-sensitive idea of white male saviors exploiting black culture. The film calls on black working class Detroiters to tell their story about the city, about poverty and the housing crisis. We’re introduced to kids cycling on colorful, pimped-out bikes who tell us about their streets and the city. Later, interlocutors sing or rap for the director, taking advantage of the opportunity to express their black city culture. This is “real Detroit” telling its own truth.

Hearing that Ryan Mendoza wants to relocate a house from Detroit to Germany for his White House project, members of the public initially express surprise but eventually lend their support, perhaps in the belief that it will highlight their plight. And yet, strangely, while it is undeniable that this is about banks and the city of Detroit abandoning poor black folk, the voices the Mendozas coral in this footage often insist that this is not a story about race. It is one about humanity.

Against the black urban mise en scene that is Detroit, Ryan Mendoza appears as an intruder who breaks into scenes with his tallness, his goofy, larger-than-life self. He’s in the houses, down and dirty in the business of demolition. He makes a cameo in a rap song filmed in the aftermath of the demolition of Rosa Park’s house, and is shown as the lonely worker painstakingly rebuilding it again in his courtyard during a cold and dark Berlin winter. You get the sense that for him it is all pomp and drama, deeply felt. When the media coverage gets dark, he delivers candid monologues about how personal a crisis the misunderstandings are.

But what indeed has Ryan Mendoza put up in Berlin? A house, a heritage object, or an art-installation? Is a house still a house when it is dismantled, its frame moved across the world, and reassembled in a courtyard without street access? Berlin regulations do not allow one to simply up and build a house where you like. Fabia Mendoza made it clear: the Rosa Parks House is officially a “temporary installation” and as such is unconnected to utilities, only partially visible from the street, and without an interior. For us at least, this change in state is important. And indeed, members of Miss Parks’ family clarify, remarking in the film and elsewhere how the house is now “in its afterlife.”

Read in this way, Ryan Mendoza has made a personal art project out of a piece of Black history. Herein lies one of the fundamental issues of the white savior complex, a phenomenon nodded at but entirely undigested by the artist. To riff on Teju Cole’s eloquent critique, in this form of the white savior complex, African-American heritage here, and Black heritage more generally, is simply a space onto which white egos can be projected, a space in which any white European or American can satisfy their artistic or emotional needs.

In doing so, even when “making a difference” or “raising awareness”, they draw more attention to themselves than to the issues at stake, inserting themselves into a conversation that fundamentally should never be about them. “It feels good,” notes for example a Berlin Tagesspiegel journalist about Berlin being able to play host to the house. The question is never asked, though, of whether it is important or even necessary that a German city feel good about the legacy of an African-American civil rights icon.

To be clear, as one always needs to be when critiquing the white savior complex in action, this is not racism, nor do we fault the Mendozas for, as far as we can tell, they’re making an effort to help both the Rosa Parks Foundation as well as Detroit and Berlin-based youth social initiatives. Yet we wonder: was the $100,000 raised to disassemble and move the house to Berlin somehow not enough to save the house where it was, or otherwise help the Rosa Parks Foundation on the ground in Detroit? Or were other options simply never considered?

In the end, how far have we come? The problem remains that the story is still about the white savior. It is not about justice but still about the emotional experience that validates privilege. It is only enough to pause and acknowledge, as Ryan Mendoza does before continuing to tear down his first house, that one is white and this should really be about black people.

There is hence no consideration of the other ways in which a person with a certain privilege can attempt to help a community. In the end, Rosa Parks’ house is no longer part of the black heritage landscape in the United States – across the world, Ryan Mendoza’s Rosa Parks House ensures that the artist’s name now has a place next to Miss Parks’ in any conversation about her legacy. Yet, wasn’t this always about his story?

Like so many others, this rescuing of black history comes with a slick sheen of altruism. But for the Mendozas it framed as a struggle, a burden. They never wanted this house. It belongs in the US, they insist. As Ryan Mendoza himself put it, “I would like to see it here for as short a time as possible. I totally love this house but this is not my house. I’m trying to give back as much as possible.” But what is never made clear, however, is what it would take to get the house back – or where exactly it would go.

The house has taken on a life of its own, through educational projects, and art and cultural performances that riff on Rosa Parks’ place in American cultural memory. But in all of this, we cannot help sense that something is not quite right. That the house is out of place here in the outskirts of Berlin. That Rosa Parks’ story fits awkwardly with that of a white European artist seeking to reconnect with his American roots. Somehow, in this fantastic tale of rescue and re-erection, we cannot but shake the feeling that, ultimately, Rosa Parks is simply a famous guest in the big story of Ryan Mendoza’s house.

May 17, 2017

Green White Green is a love letter to Nigeria’s youth

Still from Green White Green

Still from Green White GreenAbba Makama’s exuberant comedy Green White Green (2016) belongs to a new breed of Nigerian art films made outside of the Nollywood industry. Financed, in part, by the federal government’s now-defunct Project Act Nollywood, Green White Green bypassed familiar Nigerian distribution streams, including the local multiplexes, for the international film festival circuit, where it has been met with considerable acclaim.

The film had its US premiere at this year’s New York African Film Festival. An official selection of last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, Berlin Critics’ Week (a sidebar to the Berlin International Film Festival, run by the German Film Critics Association), and African International Film Festival (where it won Best Nigerian Film), Green White Green follows the fortunes of three Nigerian teenagers as they anxiously await the transition to university life.

Green White Green is Makama’s feature-film debut. It begins with a sardonic survey of Nigerian national identities, emphasizing the country’s three most prominent ethnolinguistic groups — the Hausa, the Yoruba, and the Igbo — in a brilliant parody of documentary-style didacticism, complete with stentorian voice-over narration. Perhaps most amusingly, the representative Yoruba family features a matriarch who uses Nigerian film to loquaciously express her ethnic chauvinism, loudly proclaiming the allegedly unique beauty of the Yoruba-identified work of Tunde Kelani and Kunle Afolayan — much to the chagrin of her son, Segun (Samuel Robinson), whose closest male friends, Uzoma (Ifeanyi Dike) and Baba (Jammal Ibrahim), hail from Igbo and Hausa families, respectively. Acknowledging the persistence of ethnic nationalism (embodied most memorably in the figure of an Igbo man who speaks endlessly and eloquently of Biafra and of the separatist dream that it represented), Green White Green depicts the mutually transformative friendship of three “ethnically different” young men whose elders nurture more conservative notions of “proper” social interaction.

Green White Green trailer

Makama’s film is a hopeful, downright energizing love letter to Nigeria’s enterprising youth — to a new generation plainly capable of greatness. During the Q&A that followed the screening at Lincoln Center during the festival in New York City, Makama was asked why — and with what conceivable justification — his film is so positive, so optimistic. He replied that while his original vision was much darker — arguably in keeping with contemporary Nigerian sociopolitical realities — the finished film reflects his vision of a culturally sophisticated, creative, and altogether driven young generation (which includes the youthful Makama himself), as well as his love of comedy. Co-written by the playwright Africa Ukoh, the script for Green White Green features, along with a number of hilarious one-liners, biting references to certain patterns of ethnic prejudice familiar from Nigerian popular culture (“When did Igbo people start to become dominant in the visual arts?” asks a snobbish and altogether tone-deaf Lagosian gallery owner, perplexed upon discovering Uzoma’s artistic talents).

Makama is a master of satire, as evidenced by a succession of short films that he made before Green White Green, including 2010’s Direc-toh, an uproariously funny take on Nollywood’s legendarily speedy shooting schedules, and 2012’s Quacks, which pokes fun at wealthy, well-educated Nigerian expatriates who return to their home country only to pompously prescribe remedies for its innumerable political problems (all while remaining ensconced in their air-conditioned, generator-driven compounds, of course). Strikingly, Quacks includes priceless documentary footage of Occupy Nigeria (specifically, the Ojota fuel subsidy protests of January 2012), shot by Makama’s friend and collaborator Tejumola Komolafe. Similarly, Green White Green is punctuated by documentary inserts, demonstrating Makama’s commitment to recording and conveying the lived realities of Nigeria even while offering jaunty satire.

Still from Green White Green

Still from Green White GreenBorn and raised in Jos, Makama attended college and graduate school in the United States before returning to Nigeria to found Osiris, a production company based in Lagos. Working out of the Osiris offices in Lekki, Makama has secured work in an impressive array of media, from television to the internet, collaborating with such corporations as BlackBerry, Viacom, and Globacom. In 2015, he directed Nollywood, a short documentary for Al Jazeera, which outlines the development of one of Nigeria’s most prolific media industries. Despite his career’s intersections with the Nollywood industry (and with what might be termed the Nollywood imaginary), Makama told me that he does not identify as a Nollywood filmmaker. For one thing, his work does not rely on Nollywood stars, nor does he depend upon the traditional, Idumota-, Onitsha-, and Asaba-based marketers for financing and distribution. Makama’s work thus serves as a vivid illustration of the importance of distinguishing Nollywood from other, independent forms of Nigerian cinema.

May 16, 2017

The Coffin Revolution

Image via Bonteh’s Blog.

Image via Bonteh’s Blog.On November 21, 2016, Mancho Bibixy, the newscaster of a local radio station, stood in an open casket in a crowded roundabout in the Anglophone Cameroonian city of Bamenda. Using a blow horn, Bibixy denounced the slow rate of economic and structural development in the city, declaring he was ready to die while protesting against the social and economic marginalization of Anglophone persons in the hegemonic Francophone state. Quickly dubbed the Coffin Revolutionary by English-speaking Cameroonians, Bibixy emerged as a key leader in the larger Anglophone political movement against the Cameroonian president’s policies requiring all the country’s schools and courts to use French.

While the majority of Cameroonians speak French, two western regions of the country were once part of the British Empire, and English continues to dominate in these regions. After 1922, Cameroon was a mandate territory of the League of Nations, then became a United Nations trust territory that Great Britain and France jointly administered. The British Mandate territory of Cameroon included the Southern and Northern Cameroons. The court system is based on common law. These facts, and the history that led to it, are little known among both scholars and journalists outside the country.

The protests began a month earlier as thousands of Anglophone Cameroonians, from teachers and lawyers to irate youths protested the Francophone president’s dicta in the streets of Anglophone cities.

Within months, Bibixy and two other high-profile male Anglophone protesters would be arrested and face the death penalty. The state used a 2014 law created to help combat Nigeria-based Islamist militant group Boko Haram, whose fighters regularly launch attacks in Cameroon; it formally tried the three men for complicity in hostility against the homeland, secession, civil war and campaigning for federalism. In response, hundreds of infuriated youths, mostly young men, stormed the streets to demand the unconditional release of Bibixy and the others. The government responded by outlawing groups that advocate for Anglophone rights and shutting off internet connections to Anglophone regions of Cameroon in January.

The protests in English-speaking Cameroon are the culminating point in Anglophone secessionist/separatist movements that dates to the 1960s. The British Northern and Southern Cameroons severed from Europe on February 11, 1961. Each had a plebiscite that required them to choose between union with Nigeria and union with the former French administered region, Cameroun. As Anglophone activists point out, outright independence did not appear on the ballot and evidence suggests France and Britain rigged the votes. The Northern Cameroons became part of Nigeria, which had been a British colony, while the Southern Cameroons joined Cameroun in the Republic of Cameroon, a loose confederation with semi-autonomous states, the West Cameroon State (Anglophone) and the East Cameroon State (Francophone).

While the West Cameroon State had nominal independence that extended to its own political parties and press (East Cameroon had only government-run newspapers but West Cameroonian newspapers, while heavily influenced by political parties, had a press at least theoretically independent of the state) the Francophone majority was an ongoing threat to its political autonomy. Political elites used varied social and political strategies in the period of the federal republic to preserve a distinct Anglophone national identity. These efforts did not prevent the Francophone government from making all West Cameroonian political parties and newspapers illegal in 1966 or the dissolution of the federal republic in favor of a unitary republic in July 1972. But Anglophones continued to profess a distinction from Francophones, and consequently described themselves as forcibly re-colonized within the Francophone Republic during the 1960s and 1970s.

Indeed, the regime of Cameroon’s first president, Ahmadou Ahidjo, a Francophone, arrested and imprisoned his political opponents, many of them Anglophone, and severely repressed resistance from the 1960s to 1982. As Achille Mbembe and Meredith Terreta have both highlighted, the Francophone Cameroonian state has used violence, interrogations, intrusive intelligence gathering, imprisonment, disappearances, propaganda campaigns, resettlement and concentration camps and public beatings since the dawn of independence. Consequently, as Nantang Jua and Piet Konings contend, Anglophone political elites resorted to less visible and controllable forms of protest until the mid-1990s. At this point, the government adopted wide-ranging political reforms, including the introduction of a multi-party system, fewer restrictions on forming civil associations and private newspapers and a human rights commission. These reforms freed Anglophones to act more openly, and they successfully placed the “Anglophone Problem” on the national and international agenda. Organizations, such as such as the Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC), sprang up to advocate for self-determination in the form of a return to a federal republic and later the creation of an independent state, which they call the Republic of Ambazonia.

The events of 2016 and 2017 indicate the rolling back of protections that led Anglophone Cameroonians to organize for a political configuration that would allow them full citizenship. Videos showing security forces brutalizing Anglophone student protestors in Buea, the capital of the southwest region of Cameroon, have circulated on Youtube. The Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium (CASC) called for a “Ghost Town” campaign, imploring Anglophones to withdraw from public life for two days in late January to protest the French-only rule and the shutdown of the internet. The campaign advocated that Anglophones completely withdraw from all forms of public life to stunt the economy and to protect themselves from the “trigger-happy [police] forces” in the streets. In Bamenda business activities grounded to a halt as markets, banks, fueling stations and commercial centers closed. The consortium had called for no violence during the Ghost Town movement, but angry youths barricaded the roads in Limbe, which harbors the country’s lone oil refinery. Any commercial bike rider or taxi driver caught working had to face the enraged youths. Matters reached a climax when hundreds of angry Limbe youths stormed French schools in Limbe. Hundreds of Francophone students and teachers were forced out of their various school premises by furious youths as police fired tear gas and gunshots to disperse the ramping crowd.

The ban on membership in CASC and SCNC came later that month. The internet ban made Anglophone residents of Cameroon what newspaper reports termed “digital refugees,” as they traveled to Francophone towns or Nigeria to access the internet. International pressure led to the restoration of the internet on April 21, but the government announced its determination to control internet use and block its use by secessionists and political dissidents. Whether organizers of the strike will negotiate with the government, which they made contingent on internet restoration, is unknown.

Anglophone Cameroonians have endured forcible internal colonialism by a hegemonic Francophone African “other.” Their situation raises critical questions related to self-determination, inquiries that scholars, non-governmental organizations, and policymakers should investigate. Like many fragmented African states in the postcolonial period, Cameroon has prohibited democratization and self-determination. The threat of chaos and state failure makes the project of resistance urgent. Yet interrogations of Anglophone separatism/secessionism might illuminate secessionist movements in countries like Canada, where a Quebec sovereign movement persists, as well as throughout the Global South as in Western Sahara. Indeed, neither western or African media nor academic literature can afford to continue to erase or marginalize Anglophone Cameroon from the region’s present and history.

May 15, 2017

The problem of white supremacy is not rocket science

I was losing my temper.

I was sitting in the cinema in central London watching LA 92. The spark, I’m sure, was the soundtrack. As if the beating of Rodney King’s bones, the breaking of his skin and flesh, required this exaggeration of music. As if the Los Angeles riots – the looting, the shooting, the deplorable attacks on drivers – required this orchestral melodrama. As if, I was thinking while squirming in the second row from the back, we could be weaned off white supremacy with violins.

Afterwards, a friendly stranger holding a beer and a rollie said it reminded him of Adam Curtis’ Bitter Lake. He was referring to the use of archive footage spliced together with newsreels, and the absence of a narrator. But I don’t think this comparison is helpful. Bitter Lake is a sophisticated attempt to expose simplistic Western narratives of good and evil, focusing specifically on Western politicians’ hypocritical approach to militant Islam and Saudi Arabia and their disregard for Afghanistan. LA 92 is a choreographed reproduction of the 1992 Los Angeles riots that reinforces lazy narratives on racism and violence.

We see the astonishing police attack on Rodney King on 3 March 1991 and, thirteen days later, the shooting of another African-American, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, by a female Korean shopkeeper. We see a lot of media footage of the trials that followed both events, leading to the acquittal of the four white police officers, who pounded King so relentlessly with their batons, and a $500 fine to the woman who was found guilty of the involuntary manslaughter of Harlins. We watch the riots unfold and escalate. We see the assaults on drivers by several African-American men, who manage to stop moving cars and trucks on the road. The attacks on two truck drivers – Reginald Denny, a white man, and Fidel Lopez, a Guatemalan immigrant – are horrendous. Both men were dragged from their vehicles, their bodies smashed and kicked repeatedly. We see Lopez lying on the road being spray-painted black as he goes in and out of consciousness. We see Korean shopkeepers in a shoot-out in front of their stores. We see an elderly woman weeping. We see much to make us gasp, to make us want to shield our eyes from the screen.

It is challenging viewing, particularly near the end when we are shown the mesmerizing footage of King, stuttering and blinking and appealing for calm: “Can we all get along? Can we get along? Can we stop making it horrible for the older people and the kids?” Watching this made me feel even more agitated. It looked like King was being used by the authorities. His call for calm seemed to be a call to the black community, as if the black community was the problem. Sitting in the cinema in central London, surrounded mainly by other white audience members, it felt like we were all being let off the hook. Here was the bashful, broken African-American man, beaten up and beaten down by racist white cops, now close to tears, begging everyone to just get along. And here he was doing what the cops and the army could not do – ending the riots.

LA 92 is topped and tailed with a slice of black and white footage from a 1965 television report, Watts – Riot or Revolt? The white American journalist, Bill Stout, looks into the camera and asks: “What shall it avail our nation if we can place a man on the moon but cannot cure the sickness in our cities?” This question was posed by the McCone Commission, which investigated the causes of the 1965 Los Angeles riots as well as proposing what might be done to avoid a repeat. By book-ending LA 92 with this particular clip, the film’s makers seem to be posing the same question in 2017 for the 1992 riots. Well, it may have seemed pertinent in 1965, four years before Neil Armstrong took man’s first steps on the moon, but it is limp in 2017. The problem of white supremacy is not rocket science.

Six days before I sat down to watch LA 92, I went to another London cinema to see I Am Not Your Negro. Both films are documentaries made of archival footage. Both films attend to racism in the United States. Both films look back. And so the similarities end. Whereas LA 92 runs without narration, I Am Not Your Negro threads James Baldwin’s words over the images, read (perhaps a little too) slow and deep by Samuel L Jackson. Whereas LA 92 shows beating and kicking and stealing and lying and crying, I Am Not Your Negro gives us shopping, TV shows, consumers, demonstrators, democracy and Doris Day singing and dancing. Whereas LA 92 reproduces the idea that there is “a Negro problem” and reduces responsibility for racism to the far away far right, a few bad apples in the police force and a couple of deluded right-wing judges, I Am Not Your Negro insists that there is not and never was “a Negro problem” because the problem is white people’s refusal to see ourselves and to take responsibility for our history. I Am Not Your Negro questions the true value of consumption and capital. It urges us – even nice white, left-leaning people who go to the cinema to watch critical films about race in the States – to consider who we are, what our ancestors have done, what we are still doing and how we are benefitting from the white supremacist system in which we live.

After the screening of LA 92, there was a Q&A. Chairing the discussion was Bonnie Greer OBE, the novelist, playwright, broadcaster and critic. Also on stage were LA 92 producer, Simon Chinn, and David Lammy, Labour’s candidate for MP for Tottenham, and author of Out of the Ashes: Britain after the riots. Greer began by praising Chinn emphatically for what she described as a work of art. At some point, someone in the audience asked about the decision not to have a narrator. Responding, Chinn said that the riots and King’s beating had been so heavily mediated already – on private cameras as well as by professional news crews – that he and the LA 92 team had not wanted to mediate the story any further. In so many words, he said that they had wanted to avoid injecting their own opinions onto the film – as if choosing footage, editing it and splicing it together is not a deeply subjective act of mediation.

I wanted to say so many things, I ought to have walked out. But my temper got the better of me and my hand shot up and before I knew it, I was holding a mic, telling the audience how angry I was. My frustration was such that I became quite inarticulate. Failing to string a decent sentence together, a string of questions fell from my lips. Noting that the audience was almost entirely white, I asked why the panel thought minority communities needed to do more work to fix divisions and reduce anger and violence, when most white people haven’t even begun to consider their whiteness, let alone the system of white supremacy. I complained that documentary films are not being made about the Bullingdon Club, whose members can smash up restaurants without facing charges or losing their place at Oxford University or their chance to govern the country. I said something positive about two other films Chinn had produced – Man on Wire (2008) and Searching for Sugarman (2012) – before stating frankly that I hadn’t liked this one at all. At some point, Greer interrupted me. Not unfairly, she asked me to make my point. Defeated, I remember saying: “I’m angry, I’m angry, I’m just so angry and I want you to know that.” A woman a few seats away clapped very quietly and leaned over to whisper that she agreed with me, even though I wasn’t entirely sure what I’d actually said. I thought about Baldwin. Every time he’s seen speaking publicly in I Am Not Your Negro, he looks close to tears, he chain smokes, and rage and hurt are oozing from his pores. Yet Baldwin is always articulate, considered, brave and candid. What a fool I had just made of myself. What a missed opportunity.

As the Q&A continued, so I continued bubbling over with anger. I was thinking that the documentary we had just watched seemed to suggest that the police beating of Rodney King was somehow equal to the protesters’ attacks on the two truck drivers. Of course, they are all horrific acts of violence – but they are not the same and they are not equal. They have different meanings that need to be unpacked. If the film didn’t do that for us, then we, the audience, should do it for ourselves. And we should have that conversation publicly. I was thinking about the man who captured King being beaten on his personal camera. I think it was Greer who commented that this act of filming meant, finally, everyone could see how police regularly treated African-American men. This may be true, but 25 years on and it doesn’t seem to have stopped the shootings and the beatings. Surely we, the white-skinned public, need to put our own bodies on the line. We need to take risks with our own bones and flesh. We need to physically intervene when we witness racist violence taking place. Filming is too easy.

I was also thinking about the context in which we had been watching this film. In London, many of us take it for granted that white Americans are more racist than we are, that we can look down on their crude and cruel ways because we are better and kinder. I was wishing that we were discussing white supremacy, acknowledging that this is the system in which we are living – in the States, in the UK and throughout Europe. I was thinking about all the London dinner tables I’ve sat at, listening to highly educated white people insist they would never vote Conservative but are quite happy, over lemon meringue pie, to make ignorant comments about “Africa”, choosing words like “primitive” and “under-developed” to emphasize their point of view.

If you are still wondering what my point is, let me try to be more clear. Racism is not confined to the KKK and the neo-Nazis, or even the Republican Party and Britain’s Conservatives. There are many white people who feel afraid when they see a black man on their street, who imagine that this black male body will do them harm. There are many white people who don’t want a black family moving in next door. There are many white parents who do not trust a black teacher to educate their child as well as a white teacher. There are many white people who understand themselves to be superior because that is how they have been encouraged to think. These white people may read the Guardian. These white people may enjoy dancing to Bob Marley. These white people may enjoy going on safari. These may appreciate Lenny Henry. These white people may live in Brixton. These white people may send money to Comic Relief. These white people may boast about their multicultural community. These white people may love Doris Day. They may not think about John Wayne. These white people may admire Barack Obama. These white people may love Nelson Mandela. These white people take their whiteness for granted. They know white supremacy has nothing to do with them, these white people.

May 12, 2017

Thinking aloud with Stuart Hall

In this bid to free myself from living the life of the colonized, I never had any aspiration to be English, nor have I ever become English

-Stuart Hall (with Bill Schwarz) Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands (2017)

My first ever introduction to the work of Stuart Hall (1932-2014) came in the form of an enthusiastic invitation to watch a video of one of his lectures after Sunday dinner with my friend Aslam Fataar at his home in Cape Town in the late 1990s. The exigencies and attention required by my immersion in ethnographic fieldwork on Muslims in Cape Town at the time meant I paid scant attention to it, and that my real discovery of Hall’s work came years later in Norway. Yet, the circumstances of my initiation to Hall do not strike me as particularly surprising. Hall had many readers in various post-colonies, and the attraction of his thought and legacy, and not the least the appeal of his particular mode of engagement with the world in and outside of academia to intellectuals who share his formative experiences with both creolization and colonial and late-colonial subjugation, has long been apparent.

Three years on from Hall’s death in 2014, there is a virtual cottage industry of publications of and about his work. This is not the least due to the commitment of Duke University Press’ editor Ken Wissoker to bringing Hall’s publications to the attention of new and old readers in a reasonably priced series. From the preface to Hall’s own Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands, an intellectual autobiography based on Bill Schwarz 30 years of conversations with him, we learn that Hall wanted to publish with this particular press in the U.S., due to its long-standing record of publishing the work of some of the most outstanding Caribbean-born modern intellectuals, such as Marcus Garvey and C.L.R. James. As a reader, two of the chief merits of Hall’s and Schwarz’s Familiar Stranger and the Jamaican-born anthropologist and political theorist David C. Scott’s Stuart Hall’s Voice: Intimitations of an Ethics of Receptive Generosity is that they bring us much closer to an understanding of the role that Hall’s formative years in colonial Jamaica played in his life and thought than what one could often intuit from his own work.

Scott is a former student of Talal Asad at the New School For Social Research in New York, now a professor of anthropology at Columbia University. He is a long-standing editor of Small Axe, that supremely interesting Duke journal dedicated to Caribbean arts and letters, as well as the author of a number of important monographs on the past and present of the Caribbean. He is therefore more qualified than most scholars to write about Hall.

We learn from Familiar Stranger and Stuart Hall’s Voice that Scott, though born in Jamaica, is of a much younger generation than Hall. Hall notes that his own “conditions of existence” were those of the “closing days of the old colonial world,” and that though only six years old at the time, the epochal event which formed his political generation was the “events of 1938” in Jamaica. He also notes that Scott, “two generations younger,” formed part of a “radicalized cohort of the 1970s” in Jamaica. Hall also drily comments on the fact that though many continued to consider him a proverbial “post-colonial,” and as a product of 1968, he was really a child of colonialism and of 1956. Of privileged stable and Christian middle-class brown rather than black background, Hall’s escape from Jamaica and to Oxford in 1951 was also an escape from the conditions of his upbringing in a society shaped by the multiple and perennial shadows of colonialism and slavery, which prevented him from an all-too-open identification with the racially and economically marginalized majority of black Jamaicans. Here are some of Hall and Schwarz’s memorable formulations about what it meant to “think the Caribbean”:

I came to understand that, as a colonized subject, I was inserted into history (or in this case, History) by negation, backwards and upside down – like all Caribbean peoples, dispossessed and disinherited from a past which was never properly ours.

For the young Hall, racialization was close and personal: his elder sister Pat, five years his senior, suffered a life-long mental breakdown as a result of Hall’s racially obsessed mother putting a stop to her romantic involvement with a black student from another Caribbean island whilst studying medicine. The story has of course been told before in John Akomfrah’s elegant and elegiac documentary tribute to Stuart Hall, The Stuart Hall Project, but Hall’s rendering of the personal tragedy here adds texture and nuance. This is the peculiar and internalized madness which will be familiar to many citizens of post-colonial societies to this day, and not the least to South Africans forced to imbibe the bitter poisons of racialized thinking and classification under Apartheid and their long afterlife among the dispossessed in post-Apartheid South Africa. What these experiences meant in Hall’s intellectual thought is fleshed out well in Scott’s book.

For a radical thinker like Hall, unlike say Ernesto Laclau, the questions relating to identity were not simply intellectual abstractions, but lived and embodied experiences. “The distinctions between my life and ideas really have no hold,” Hall remarks in Familiar Stranger. Hall’s co-authored book is an intellectual autobiography written in the style of the late Edward Said’s poignant memoir Out of Place or the late Chinua Achebe’s thrilling The Education Of A British-Protected Child, and we therefore learn relatively little about Hall’s formidable wife, the distinguished British historian Catherine Hall. But we get a glimpse of Stuart and Catherine Hall’s problems with the social world of racial and class exclusion his parents inhabited when learning that Catherine on her first ever visit to Kingston in 1965 had an altercation with his mother, brought on by the latter treating a black Jamaican housemaid as if she did not exist and talking about “the servant problem” in front of her maid. Hall was acutely aware of the structures of possibility and impossibility which marked his early life and his mother’s obsessions with graduations of color and status.

“It is important for me to acknowledge, personally, that the pathologies which accompanied my upbringing weren’t peculiarly mine, and need to be located in their larger history,” Hall writes. Hall himself was more dark-skinned than either one of his parents and siblings, and so it comes as no surprise to hear him self-describe, like Edward Said did, as a proverbial “black sheep” of his family.

It would perhaps be more apt to characterize Scott as more of a political theorist than an anthropologist – but then again, the policing of disciplinary boundaries by virtue of an insistence in ethnographic fieldwork here or there being the sine qua non of anthropological virtue and integrity is, and remains, one of the more problematic aspects of modern anthropology. Much like Hall, Scott is a disciplinary hybrid of sorts, well-read not only in political theory and anthropology, but also in philosophy, letters and arts. It is not that Hall and Scott are in consent about how to understand and analyze the post-colonial present. In his introductory apologia, Scott alerts the reader to the fact that he wasn’t and isn’t drawn to Hall as an intellectual friend due to his sharing either Hall’s theoretical idiom, conceptual language, or his substantive views. Instead, Scott conceives of Hall as “an exemplary intellectual” that is “productive to think with” and “to think through.”

Scott’s small and eminently readable book is written as a series of epistolary letters to his late friend and mentor. Scott’s choice of genre gives a sometimes eerie impression of a one-way dialogue with a dead intellectual. When the book merits our attention, it is in its keen attention and responsiveness to central themes in Halls oeuvre, and Hall’s mode of thinking and engaging as a public intellectual. For Scott calls attention to Hall’s using his particular and characteristic voice as a public intellectual as a mode of thinking itself; and speaking and listening a way of clarification.

Hall was of course a pivotal figure of the so-called New Left, which emerged in its nascent form at Oxford University in the mid-1950s, and a founding father of Cultural Studies. His autobiography – regretfully to my mind – stops before his move to Birmingham to take up the chair in Cultural Studies, one that would make him a household name for academics across the world. He spent a great deal of time and energy trading barbs with classical Marxists with whom I often disagreed vehemently about matters relating to the analysis of ideology, contingency, identity and the role of determination in human history. And so Scott is right to assert that his “post-Marxism grows out of a never-ending – and never-endingly agonistic – engagement with Marx and Marxism.”

Returning to Hall’s work in the years after his death, I have like many others been struck by his prescient views of the neoliberal revolution ushered in by Thatcherism in Britain and by extension Reaganism in the U.S., in works such as The Great Moving Right Show. For though the very term neoliberalism, as Scott is right to note, came relatively late to Hall’s work, Hall saw much more clearly than any Marxist at the time the extent to which this was also a cultural revolution of a kind whose aftermath would inflict systematic and long-term damages on the lives we all live, and fundamentally alter the political terrain so as to make it increasingly difficult to oppose it and to mobilize against it. We now live in a present in which the term “identity politics” has become a monumental straw man for all that ails our societies North or South, and when bending backwards to accommodate a resurgent “white identity politics,” of course never named as such in the past or present (“identity” supposedly being the preserve of “minorities,” though Western history tells us all about the sheer absurdity of a such a proposition) the order of the day for politicians left, right and center. It is therefore salutary of Scott to bring renewed attention to Hall’s seminal work on identities, and the way in which Hall’s work on this stands removed from a certain form of “postmodernist celebration of migrancy as an inventive self-fashioning gesture”:

For the migrant (or anyway the black colonial migrant) is always obliged to respond to an interrogation that precisely objects and constructs her or him in a constricted place of identity- that demands an answer in the policing jargon of identity: Who are you? Why are you here? Where are your papers? When are you going back to where you came from? Identity here is inflicted; it is not a luxury. Therefore, identity for the migrant is not always-already a question; this question is always inscribed in a relation to dominant, sometimes in fact, repressive state power.

Hall was, by his own admission, not the most systematic of thinkers: his preferred form was the academic essay, and his public interventions addressed present contingencies in the manner which one imagines being preferred by a Gramscian organic intellectual of sorts. There wasn’t from Hall’s side any intention of presenting “the final word” on anything, and little to be had in terms of grand theorizing – all aspects that one imagines contributed to the annoyance which Hall met from classical academic Marxists of his time. Scott is exceptionally good in bringing out this aspect, which he proposes stems from Hall’s dialogical orientation or his “thinking aloud,” in Hall’s intellectual production. I particularly relished Scott’s subtle and impressive take down of the utterly condescending and unexamined white Marxist literary critic Terry Eagleton’s supposed “critique” of Hall in the London Review of Books in 1996 (“hip, neat, cool, right-on… Hall has never authored a monograph”) in the first chapter of Stuart Hall’s Voice.

Scott’s epistolary letters, which emerge out of a series of invited lectures he gave at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) in South Africa in 2013, are also of great value for their bringing the scholarship of intellectuals to which Hall paid relatively limited attention himself to bear on the analysis of his work.

If you think you know enough about the importance of Marx, Gramsci, Fanon, Baldwin and Althusser for Hall, here is as good a chance that you will get to see it from a fresh and original yet attentive and closely-read angle. There has never been a better time, in the context of the re-emergence of racialized modes of thinking, racism and discrimination across vast swathes of the Western world, to read and re-read Hall.

We owe it to both Schwarz and Scott for once more bringing the relevance of the late and great Hall’s work to our attention.

May 11, 2017

Reclaim the City

Protesters at Tafelberg.

Protesters at Tafelberg.The Tafelberg site in Sea Point, a rich suburb of Cape Town, has come to symbolize the vested interests that corrupt our state and maintain white property powers’ near-exclusive access to well-located land and housing in Cape Town. In December 2015, this prime piece of state-owned land was sold to a private buyer with no strings attached. Since launching in February 2016 the Reclaim the City movement has brought political, legal and researched objections to the sale. This campaign is a call for Tafelberg, and all suitable public land to be used to decolonize and desegregate the city, to redress the past and build the just and equitable society that our Constitution requires.

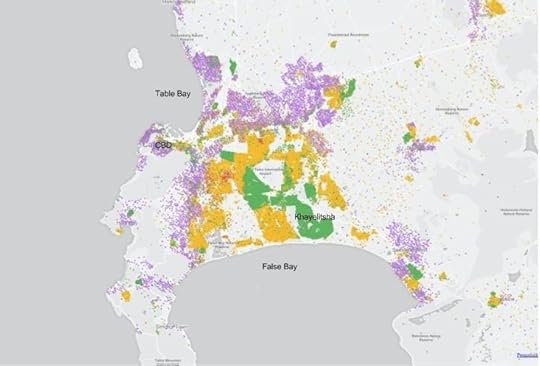

Census data shows that the race-based blueprint resultant from colonial and Apartheid segregationist spatial planning remains largely unchanged. A property boom in the Cape Town inner-city means that displacement continues to happen, albeit due to market forces, perpetuating our inherited Apartheid city design. Inequality is so deeply etched into the geography of Cape Town ensuring the status quo remains intact. The city’s defining characteristic is one of “inverse densification”: a largely poor and working class black majority live on the urban periphery, in overcrowded settlements, far from jobs and with poor access to amenities and services.

On the other hand, well-located central areas, most of which were previously designated “whites only” areas, are characterized by low densities coupled with an acute shortage of affordable housing options, despite excellent access to amenities, services and employment opportunities.

It is against this backdrop that the sale of state-owned land, located in the heart of the city, to exclusive private interests must be challenged. Contestation around the Tafelberg site and sale is where these battle lines have been drawn. The Tafelberg Remedial School site is a property of 1.7 hectares, roughly the size of two soccer pitches, on Sea Point’s Main Road. It belongs to the Western Cape provincial government, which declared the site “surplus” to government’s service delivery objectives, in spite of a request from its own Department of Human Settlements that it be reserved for affordable housing. In late 2015, the province’s Department of Transport and Public Works, sold Tafelberg to a private buyer for R135 million.

The site was sold to help fund an unaffordable billion rand public-private partnership to build a new office block for provincial government. The then head of public works, who was instrumental in putting the site to the market, left his position and became a director of a property company which quickly snapped up a R90m building across the road from the Tafelberg site. Property moguls Lance Katz and Samuel Seeff demanded that the Sea Point Jewish community not engage on the issue of housing at Tafelberg claiming that it would be detrimental to “community interests.” Legislated bodies intended to exercise parliamentary oversight of property deals were in total disarray and have been reduced to “rubber stamping.” More fundamentally it revealed that the state’s archetypal approach to “urban regeneration” is deeply anti-transformative.

After a court order interdicted the sale of the site, an unprecedented public participation process brought the issue of spatial Apartheid to front and centre of civic politics through the campaign to #StopTheSale of Tafelberg. Finally, the fact that not a single subsidized housing unit has been built in the inner city and surrounds since the end of Apartheid 23 years ago is getting its due recognition.

2011 Census data shows a highly racially segregated Cape Town. Note the higher urban densities in Black and Coloured neighborhoods on the urban periphery. Source Adrian Firth.

2011 Census data shows a highly racially segregated Cape Town. Note the higher urban densities in Black and Coloured neighborhoods on the urban periphery. Source Adrian Firth.A new public consensus is being built around the issue. Input from a wide range of stakeholders, from policy and development experts to working class residents under constant threat of eviction from central suburbs like Sea Point called for the site to be reserved for housing. In depth studies proved that social housing was feasible on the site. But instead of grabbing the opportunity to take a bold step to deal with segregation in Cape Town, the provincial government opted to continue with the sale citing a number of pseudo-technical arguments that have all been rebutted.

Since its launch in February 2015 the Reclaim the City campaign has directly confronted property power through the courts, in policy and on the streets. In response to Province’s decision to continue with the disposal the campaign has escalated to civil disobedience with supporters occupying two provincially owned sites which were vaguely “promised” for affordable housing in lieu of Tafelberg. As the battle for Tafelberg moves back to the courts, the campaign for this prime piece of land has already opened up the opportunity for a bold new urban politics in Cape Town’s center of power.

May 10, 2017

Senegalese struggles play out on screen

Scene from “Marabout’ directed by Alassane Sy. Credit: Film Still.

Scene from “Marabout’ directed by Alassane Sy. Credit: Film Still.Explaining why his films typically center around the heroism of daily life, Ousmane Sembene once said: “We have most individuals, both men and women, who are struggling on a daily basis in a heroic way and the outcome of whose struggle leaves no doubt. This is a struggle whose purpose is not to seize power, and I think the strength of our entire society rests on that struggle.”

The New York African Film Festival just concluded its 24th edition. This year, it put Senegal in the spotlight, featuring five short films (“Senegal Spotlight”) from there. Whether heroic or not, the five short films capture the daily struggle of ordinary Senegalese citizens and touch upon the main issues that the Senegal’s urban society faces.

In the last scene of Maman(s), the eight-year old Aida asks, “Mom, does dad still love you?” To which her mom responds, “Yes, of course”, looking away. This film portrays the crammed lives of Senegalese migrants in the suburbs of Paris, where cultural and societal baggage is compounded by the economic hardships of living in the periphery. When the father returns from Senegal with a second wife and baby in tow, we see through Aida’s eyes the imbalance and struggle to adjustment to this new life. This film is foremost about cultural translation in foreign spaces, immigrant families in tiny places, and surviving both physical and psychological violence.

Maman(s) Trailer

Violence is also the central theme of Marabout (directed by Alassane Sy, whose acting résumé include Restless City, Mediterranea, and White Colour Black), in which a group of street children commonly known as “talibé” are abused by their teacher/guardian (the “marabout”). State and society fail to solve this tragedy that is so visible in Senegal’s main cities. A police detective spends his day chasing around a kid who has stolen his phone only to later come to face with the brutal lives of the talibé. Perhaps as an indictment of the state failure, Detective Diagne arrives too late, after one of the kids has slit the marabout’s throat, and escaped.

Marabout Teaser

Escaping is also a major theme across all the films. In Boxing Girl, a young woman escapes her boring life as a hairdresser when she finds a pair of boxing gloves and tries them on. Guided by the mystical power of the gloves, she wanders around the streets and ends up in a boxing ring, after she is told that “Not everyone is made to be a champion.”

The young men also try to escape their daily struggle through treacherous migration routes or finding refuge in their dreams of leaving. With the ocean running out of fish because of the EU and Chinese fishing boats, local young fishermen find themselves idling, dreaming of escape. That is the story of Matar, the main protagonist in the film Dem! Dem! “Leaving is the only solution. So things change,” Matar tells her girlfriend.

Samedi Cinema is a much lighter story of escape, as two kids try to figure out ways to find money to see the final movie screening before the last theatre in town shuts down. This of course raises the issue of the lack of movie theaters and cultural venues in Senegal, despite the very dynamic Senegalese film industry.

Samaedi Cinema trailer

May 9, 2017

Finding humor in Egypt’s tragedy

At the height of the Egyptian revolution, Bassem Youssef, a Cairo surgeon, regularly posted satirical YouTube videos, which he shot in a laundry room when he was off duty. When Egypt’s longtime dictator, Hosni Mubarak, was forced to resign, Youssef, buoyed by the new media openness made the leap to late night television. In 2012, Egyptians elected Mohammed Morsi – in the country’s first free and fair presidential elections. Youssef’s show, Al Bernameg, thrived during Morsi’s short lived one-year term. Soon he was being compared with Jon Stewart, though Yousef commanded three times the audience of Stewart. He was one of the most famous comedians in the world and central figure in the Egyptian media. By 2013, Morsi was overthrown by Egypt’s military, leading to the rise of General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Though Morsi’s government once sued Youssef for mocking the president, the generals had no sense of humor and were less forgiving. By 2014, pressure on the television channel led to Youssef’s show being shut down. He is now the United States, giving speeches about press freedom and working on a new show.

The short rise and fall of Al Bernameg, is now the subject of a documentary film, Tickling Giants, by director Sara Taksler. We get to see a close-up, first person account of how the revolution unfolded, the show’s three-season run neatly coinciding with major political changes, from the euphoria and optimism of 2011, to the reign of Morsi and rise of el-Sisi. Youssef floats atop events as they play out in the streets of Cairo before director Sara Taksler’s cameras.

She rides along with Youssef and his cast of supporting characters – writers, cartoonists and comedians – as they rise to global fame. The film shines during the Al Bernameg’s troubled third season, as the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), led by el-Sisi, comes to power and the show becomes another arena for political contestation amidst hyperpolarization in the wake of Morsi’s ouster.

Threats to critical voices by the Egyptian state are a looming presence throughout the film, whether it is controlled by the Muslim Brotherhood or the resurgent generals, but it is ultimately the audience that turns against Youssef’s stinging critical satire during the third season of his show. While the documentary focuses on the revolution and the role that satire can play in a changing society, its exploration of el-Sisi’s rise and how the creators and writers of the show react to it that is most compelling, offering a fresh insight into the tragedy and disillusionment of the post-Morsi era.

“People value personal freedom over the freedom of expression” Youssef posits, as the country turns to the once-maligned military establishment to extract it from the incompetency and divisiveness of Morsi’s government. Though the default mode of the subjects is levity, an edge and weight comes through in their exchanges during the most intense moments of the revolution, as when the writers are discussing the way forward in the aftermath of the coup, and Youssef offers a sharp rebuke, “Principles alone don’t change things.”

Youssef and company are caught off guard by how quickly the mass of people appear to abandon the ideals of the revolution in favor of the false promise of stability offered by SCAF, from being enthralled by the possibilities opened by the uncertainty of the revolution to embracing the poisonous discourse of establishment, replete with conspiracy theories about foreign plots. This is a narrative that has become very appealing in recent years, as the victories of the revolution are continuously reversed. In the space of a television season, Youssef goes from the voice of the people to a dupe in the eyes of much of his audience. The film, through Youssef’s narration, excellently exposes the way the narrative of the counter-revolution shaped events, and rendered the very idea of change undesirable to a weary and uncertain public. As el-Sisi set about crushing the vestiges of the revolution, Youssef’s satire and relentless critique of authority quickly go out of fashion; people no longer want their ideas prodded, even in a humorous way, preferring to believe the official story as long as it means a return to normalcy in their everyday lives.

Tickling Giants is ultimately a tragicomic glimpse into a time when everything was possible. It is a film that is well worth watching, both as an airy primer on the Egyptian revolution and a thorough exploration of the power and limitations of satire. As Egypt enters its fifth year of el-Sisi’s reign, it can be difficult to look back with anything but despair at the lost hope of the Arab Spring, but, as Youssef notes in his closing remarks, “A revolution is not an event, it’s a process.”

*The film is currently available on Netflix in a number of Middle Eastern, European, Australasian, and African countries. It will be available in the US on Amazon and iTunes in June 2017.

May 8, 2017

Karel Schoeman, discovering the completed journey

Image Credit: Editions Phebus.

Image Credit: Editions Phebus.The famous last paragraph of Karel Schoeman’s Another Country reads:

Once, when he had just arrived here; once, in another time when he had still been strange here, alienated from the country in which his stay, as he had thought, was to have been merely temporary – once, his walks in the evenings had taken him to the edge of the town and he had hesitated there, wavering before the landscape that had lain open before him, unknown and unknowable, and an inexplicable fear had filled him at the sight of that emptiness. But there was no cause for fear, he thought as he began to walk slowly and without hurrying back towards the landau, leaning on his cane. The emptiness absorbed you and silence embraced you, no longer as alien wastes to be regarded uncomprehendingly from a distance; the unknown land grew familiar and the person passing through could no longer even remember that he had once intended to travel further. Half-way along the route you discovered with some surprise that the journey had been completed, the destination already reached.

The South African novelist Karel Schoeman died on May 1. It appears he committed suicide. Schoeman published 19 novels, ten autobiographical works and about 40 historical works reflecting life in the colonial Cape (most of them tomes), mostly in his first language, Afrikaans.

The reaction to his passing by journalists, literati, historians, philosophers and other readers in various publications during the past week, attest to his indisputable position as one of the most remarkable South African writers. He was remarkable for many reasons, one of them his unrivaled output. Many of these historical works are biographies – sometimes on well-known individuals from history, but more often on the lives of forgotten and seemingly unimportant individuals.

Schoeman’s work has always focused on the past (even in a dystopian novel like Promised Land; Na die geliefde land). He describes the past thus: “The past is another country, unreachable in its distance, and what can be recovered from it, what can be preserved out of it, you carry with you.”

Sometimes the past is also likened to an impenetrable darkness. With his meticulous historical research, Schoeman traveled to that other country, he penetrated the darkness by recovering painstaking detail, often about seemingly insignificant persons or episodes. The patient reader who follows these long, winding renderings finds no clear philosophical arguments or moral judgements, but as if carried away by the rhythm that almost becomes an incantation readers find themselves returning from another country with something preserved from the experience. Perhaps this is most clearly suggested by the end of Verliesfontein, but it surely holds true for all his work, because Schoeman’s novels are the kind of novels that Milan Kundera idealized when he wrote: “The sole raison d’être of a novel is to discover what only the novel can discover. A novel that does not discover a hitherto unknown segment of existence is immoral. Knowledge is the novel’s only morality.”

Schoeman wrote the kind of novels that discovered hitherto unknown segments of existence. These discoveries of new knowledge were usually the result of painstaking renditions of everyday experiences of ordinary people. The apparently insignificant details that form the backbone of his novels slow down the reading process, and it creates an awareness of each passing moment. His later work (the “voices trilogy, Hierdie lewe, Die uur van die engel and Verliesfontein as well as Verkenning), reveals a painful awareness that language can never represent the past, can never succeed in presenting reality. We cannot pin down and preserve any moment in reality. Life is slipping away like sand. We only have the odd traces that remind us of our predecessors and past events. Schoeman doesn’t provide answers. His novels are performances providing experiences of possible ways of thinking, of remembering and of being.

JM Coetzee’s remark about ’n Ander land (Another Country) actually holds true for all Schoeman’s novels: “’n Ander land strikes one as a philosophical novel not because it carries out a philosophical investigation in any depth, but because it performs a mimesis, an imitation, of the movements of the spirit in the process of a philosophical quest.” For this reason Schoeman’s later novels are probably the ultimate in the sense that they cannot be rendered in any other medium. They cannot be summarized or filmed, but provide experiences of thought processes about what it means to live and die. But of course they are not examinations of living and dying on a vague existential level, his novels investigate what it means to live and die in Africa.

Not all Schoeman’s novels are impossible to render in other media. The 1973 novel, Na die geliefde land (the double implications of the title lost in the English translation, Promised Land) has been filmed almost three decades later and this dystopian work remains a careful analysis of the tension between nostalgia and creativity as responses to crisis.

Schoeman refused to be a guide. He did not indicate a route. Rather he forced readers to a stand still, to reflect and to discover, with some surprise, that the journey has been completed.

May 6, 2017

Le Pen vs. Macron: Implications for Africa

After a highly fractured vote in the first round of the French presidential elections, Marine Le Pen, of the right-wing Front National party, will face off against Emmanuel Macron, leader of the centrist En Marche! movement in the second and final round today (Sunday). Polls open at 8am in metropolitan France.

Interpretations abound about what each candidate would mean for France: in one typical dichotomy, Le Pen represents the preservation of French values in the face of globalization and Europeanization, while Macron is said to be a sell-out, representative of France’s economic elite and a sure path toward the loss of French specificity and culture; in another, Le Pen represents regress and a closing off from the world, while Macron represents openness to a progressive and inevitable march toward globalization; alternately, for some leftists, many of whom voted for Jean-Luc Mélenchon (who came in fourth, albeit within just 4% of Macron and Le Pen) or Benoît Hamon (who came in fifth), Le Pen represents a racist, nationalist brand of populism developed in reaction to—and made possible by—continuous neoliberal economic policies of the sort espoused by Macron.

This election has been especially wrapped up in the question of France’s national identity and its place in the world and has been cast as particularly decisive for world politics, with each candidate singing to the tune of a different discourse. For European Union member states, especially, the decision of the French electorate could have rather immediate, concrete repercussions given the candidates’ opposed views on membership in the union. Yet as regards Africa, many features of French policy on the continent are likely to remain the same, regardless of who wins. For example, given France’s long-standing counterterrorism efforts and the recent attacks there, the French military presence in Africa—which has its origins in the colonial project and which still operates in part from old colonial military bases—will undoubtedly remain strong. Interventions in Mali, Central African Republic, Chad, Ivory Coast, Libya, and Djibouti have all been justified by the French government as counterterrorism efforts in the interest both of France and of these implicated countries. Whether or not one takes this justification to be true, France certainly has further unspoken interests in maintaining a presence there, such as access to natural resources, especially now that it finds itself in competition with China for influence in francophone Africa. As it stands, though, France remains the main trading partner for many of its former colonies. For Macron or Le Pen, the difficulty could come in increasing the French presence subtly enough so as not to invite accusations of neo-imperialism.

Despite the continuity of this long-standing national strategy in Africa, there would, of course, be differences between a Le Pen and a Macron presidency. A Le Pen presidency could be especially fraught with complications regarding the diaspora in France, where French citizens of African descent have been demonized throughout her campaign. For one, Le Pen has talked of forcing dual nationals to give up one passport unless the other nationality is a European one. This concession toward the notion of a culturally coherent Europe is a strange one considering the Front National leader has campaigned on a platform that includes leaving the E.U.; indeed, it seems to betray the purity of a nationalist ideology ostensibly based on a simple distinction between France and all other countries, instead further revealing that among all these other countries, the European ones are better than the others. This paradox suggests a racialization of nation-states that is nonetheless consistent with the xenophobia of her campaign rhetoric—and, indeed, consistent with the policies of European countries—which has made her immensely unpopular among French citizens of African descent (although many such citizens are likely to not vote). One common fear among these citizens is that a Le Pen presidency would embolden those sympathetic to her message to become more active in their racism.

Regardless of all this, Le Pen seems keen to maintain an active foreign policy with African countries, based on relationships of “non-interference, which doesn’t mean indifference.” It appears that Le Pen would try to pay lip service to isolationism and to national sovereignty—which serves her domestics interests—all the while preserving French involvement in the continent. If this is to pass, she might have to betray her anti-Europeanism once more given that previous French engagement in Africa has been endorsed and facilitated by the E.U. and the U.N. Towards the end of solidifying French activity in Africa during her potential presidency, Le Pen recently visited Chad and the headquarters of the French anti-insurgent Operation Barkhane, in N’Djamena.

The specific repercussions of a Macron presidency for Africa would not foreseeably give way to the theatrics that a Le Pen presidency could well do. Yet Emmanuel Macron is a staunch supporter of the European Union, whose policies have had damaging consequences on the African continent, through the Union’s Common Agricultural Policy, for example, which has flooded the African market with European produce and raised taxes on certain imports into Europe, effectively forcing many African vendors to abandon the market. In addition, the ongoing immigration of Africans to Europe across the Mediterranean has compelled European states to try to outsource their border security apparatuses to North Africa. By converting North Africa into a securitized buffer zone, Europe could push potential skirmishes and the poor treatment of immigrants southwards, thereby avoiding human rights scandals on its own soil and reinforcing the image of Africa as a site of perennial conflict to be fixed at the opportune moment. Despite the explicit racism and clear danger of Marine Le Pen’s discourse—and, hence, the relative appeal of Macron’s rejoinder discourse of tolerance for many Africans and French people of African descent—a Macron presidency and all the progressivism that the European Union seems to embody for his supporters would still allow difficulties to continue for many African countries. The real danger of a Macron victory is that, simply by virtue of not being Le Pen, his policies will be treated as reasonable.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers