Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 281

May 31, 2017

‘The African Who Wanted to Fly’ softens the image of China in Africa

When he was fifteen, the Gabonese Luc Bendza embarked on his life journey to China to follow the footsteps of his childhood movie stars, Bruce Lee and Wag Yu. Notwithstanding obstruction from his family, the cultural shock and economic hardships in China, and continuous racial unfriendliness in his host community, Bendza joins a prestigious wushu academy and excels. But Bendza went beyond that, to become a professor at the school for more than 20 years; won the first world championship of wushu; and met and worked with Jackie Chan and Bruce Lee’s producer. Bendza’s remarkable life is now the subject of a 72-minute documentary film, Samantha Biffot’s film “The African Who Wanted to Fly” (2015).

The documentary is shot in China, Gabon and Belgium with narrators speaking in their respective languages, mostly French and Mandarin (it is subtitled in English). Weaving back and forth in time and space, Biffot’s documentary opens with the current phase of Bendza when he accomplished “half of his dreams” and established his name. Slowly, the documentary delves into his upbringing to narrate—through his siblings and childhood friends—his obsession with Kung Fu.

Born into a family of teachers in middle-class family in Gabon, Bendza, like most of his contemporaries, where other means of entertainment was little, spent his afternoons practicing martial arts. He was obsessed with Bruce Lee and attempted to mimic his gestures and utterances at home with his family and friends outside. Unlike his friends who had other lives, Bendza lived an aloof style; focusing on his ultimate goal—to fly. Already named “master” among his contemporaries at his early age, he attracted a crowd of about 300 to 500 people from his neighborhood and other far places during his King Fu shows with his group.

Bendza’s life changed when he met a Chinese visitor who came to Gabon as interpreter to the Chinese medical team; Bendza befriends him and immediately impresses his guest. After noting his determination to go to China and study martial art, he agrees and helps him convince his family.

As the documentary film shows, China was not easy for Bendza. Being the only black person in the whole school, combined with the lack of cultural exposure of Chinese people at that time posed serious challenges. From young students in a desolate area running away from their seats after seeing him on stage to locals who would use derogatory words on the streets even when walking with his family to his in-laws who initially resisted to allow their daughter to marry a foreigner, Bendza has gone through many cultural trials and tribulations. It is against such continuous challenges and walking in a tight rope, balancing the two cultures and nations that he eventually came all the way to accomplish his dream. In tough times when he was pushed to the edge of quitting, it was the wushu discipline that helped him continue unabated.

Biffot’s excellent documentary is more than Bendza’s personal journey. Rather it seamlessly captures the popular cinema culture in many parts of Africa of the mid 1980s and early 1990s. Bendza’s aspiration has been widely shared by many young boys who dreamed of one day becoming Bruce Lee and other martial art masters. Biffot’s documentary projects how the dream of many young boys could have been had they trekked their journey.

Biffot masterfully overcomes the inevitable challenge of a documentary film–the long and intensive interviews. “The African Who Wanted to Fly” breaks the long narration through music, enticing scenery of nature and footages from films, and reenactments. The soundtrack of the film has also played a key role in making easier to follow the documentary. At times, serene and melancholic instrumental Chinese music and other times vibrant hits that also combines Gabonese beats, the music transitions from one scene to the next and weaves back and forth in time and space smoothly.

The underlying teachings of martial arts–living harmoniously with nature—is also manifested in documentary. The communal music performances in the parks across China is well documented and serves the purpose of breaking the monotony in the film.

The making of the documentary film and watching itself is an embodiment of the wushu philosophy as it is produced in line with art of living in peace with nature that withstands violence.

At bigger scale “The African Who Wanted to Fly” also helps soften the image of China in the continent where it is devolving into cheap products and market control. The popular perception of Chinese about Africa, as demonstrated in the film is, borrowed from the Western media and even becomes worse as it is copy of the original. It is mainly through such cultural exchanges and sports that perception of each other can be improved. Bendza is living testimony. Where others failed, sports and arts can bridge such gaps.

May 30, 2017

It wasn’t cricket

Cricket fans watching South Africa vs Australia. Image via Flickr.

Cricket fans watching South Africa vs Australia. Image via Flickr.Ashwin Desai’s book Reverse Sweep: A Story of South African Cricket Since Apartheid opens with a quote by white South African writer, JM Coetzee: “Cricket is not a game. It is the truth of life.” In a book that is a sublime infusion of politics and cricket, Desai, a South African Indian writes with a lyricism of which Coetzee, a Nobel Laureate now living in Australia, would be proud.

Yet, while Coetzee’s poetics compare playing cricket to an unpassable test, Desai’s deal with more systemic challenges faced by black South Africans in even getting onto the field in the first place. A sociologist, he treats the reader to a scathing critique of the South African cricketing fraternity over the Apartheid, transition and early democratic eras through the lens of race and class. He expertly and personally narrates the impact on the South African game of racism, neo-liberal capitalism, corruption and maladministration. In many ways, therefore, the book reads as the story of South Africa – from the perspective of an Indian South African activist, academic and cricket fan – lathered with beautiful cricketing metaphors.

It is a book that reverberates with familiar post-apartheid narratives: the speedy abandonment of resource redistribution in favor of international competitiveness; a corruption and bribery scandal toppling the first African institutional head; conspicuous double standards applied against new black players as compared to white players; and the “necessary evil” of apartheid-era administrators and leaders continuing to profit from their expertise and connections in the democratic era, entirely without sanction. It is a devastating indictment of governance in South African cricket in particular and the country more broadly.

Using some of Desai’s own chapter headings, in this review, we attempt to briefly capture the breadth and power of this book in the hope that it will challenge many who may not read it and influence many more to find a way to do so.

Of white knights and A partheid ideologues

Perhaps the most powerful narrative in the book is its indictment of the past and present white cricketers, cricket journalists and cricket administrators (both from South Africa and abroad) for their hypocrisy, brazen racism and servile self-interest. Understood in its full context, Dr Ali Bacher, the book’s apparent grand villain, is representative of a range of other white people involved in pillaging black cricket in South Africa all the while masquerading as saviors, philanthropists or activists.

Bacher, the last white captain of an official Apartheid-era South African cricket team, was the key orchestrator of so-called “rebel tours” of international cricket teams to South Africa throughout the international sports boycott on South Africa (instituted because anti-Apartheid activists rightly insisted that there could be “no normal sport in an abnormal society”). Throughout, Desai describes a range of pathetic excuses presented by Bacher for these profit-motivated tours: that Apartheid was not really so bad; that racism existed in all countries; and most offensively, the claim that actually the breach of the boycott was good for black cricket in South Africa and black South Africans more generally.

Desai cuts to the core, noting that while Bacher could be correct that on one such rebel tour black West Indian fast bowler Colin Croft might have been seen speaking to coloured children on the boundary, and white children may well have offered his teammate Franklyn Stephenson a cold drink, that this was hardly proportionate to the harms caused by the rebel tours and “what Bacher might have added is that white children had been offering their leftovers to the ‘garden boy’ for centuries in South Africa”. As if to cement the irony of Bacher’s pitiful excuses, Croft, himself heavily criticized by his compatriots for agreeing to tour South Africa, was thrown off a whites-only carriage of a train in Cape Town.

Despite this, Bacher managed to ascend to prominence, remaining synonymous with cricket administration in South Africa for over a decade after the end of the Apartheid, fashioning himself as a human rights activist. In line with a common trope in South African cricket, he claims not to have “understood the full reality of South Africa” or “what the fight against apartheid was all about.” Drawing the link between Bacher’s behavior and the opportunism of many similarly situated white South Africans, Desai is scathing:

When did Bacher’s human rights activism begin exactly? After he was the last white captain of an official apartheid era team, but before he organised the rogue tours that broke an international boycott? Or did he become interested in human rights after the tours but before Mandela was released? If it was the latter, he joined many white South Africans, who, as the saying sarcastically goes, never support apartheid.

New whites for a new South Africa

Either way, Bacher, along with other putatively reconciled but unchanged “new whites” slid smoothly into the “new South Africa” without skipping a beat or losing a cent. South Africa’s willingness to compromise with (white) moneyed interests, buoyed by notions of reconciliation and rainbow nationalism, produced an immediately co-opted color-blind non-racialism.

After fighting tooth and nail to enforce South Africa’s international isolation from the cricketing world, the African National Congress went out of its way to support the immediate re-entry into international cricket for an all-white side – accompanied by two black “non-playing,” “development” cricketers – in India in 1991. Desai details how Nelson Mandela himself, famous for his willingness to don the infamous Springbok jersey three years later, actively supported this venture. Ironically, Madiba adopted the position of the colonial cricket establishment when he described as “extremists” those who maintained that there could be no normal sport in an abnormal society, stating instead that “sport is sport, and quite different from politics.”

None of this, as we know, is inconsistent with the ANC’s post-1994 politics or its centralizing, controlling behind-the-scenes-maneuvering culture. That culture has long destroyed parts of the anti-Apartheid movement that agitated for a more radical transformation of society. Nevertheless, the clarity of Desai’s revelations rankle for those of us who retain some belief in the idea that the ANC was ever a genuine advocate for the obliteration of white supremacy, poverty and inequality.

In cricket, the contingent calling for radical change were the black clubs and activists (represented by the South African Cricket Board and South African Council of Sport) who called for policies to redistribute resources following Apartheid’s deliberate destruction of black cricket. Desai makes a convincing argument that the top-down approach of Dr Bacher’s administration – beginning with the reintegration of a white team into international cricket and aiming to trickle down benefits to the grassroots – and supported by the likes of Steve Tshwete, Sam Ramsamy and Nelson Mandela, has profoundly stunted exposure and opportunity within the cricket microcosm. Furthermore, this approach dismantled the structures that advocated politically for substantive change in the form of the politics of reparation and redistribution, favoring instead the politics of representation, or, in Bacher’s words the need for more “black faces.” Desai observes “at a general level depoliticisation was thus the handmaiden of demobilisation. Change was defined as a set of technical issues and targets to be met.”

Given this approach, it is unsurprising, that the present crop of black South African cricketers hail primarily from well-resourced private schools and formerly exclusively white public schools, as Desai notes. Their backgrounds, rather than proving the success of transformation strategies, often highlight the complete failure of a truly developmental cricket program in South Africa – a program able to produce competitive teams in poorer black areas such as the rural Eastern Cape where the game remains extremely popular.

Desai also highlights the blatant racism of white cricketers participating in rebel tours and the continued self-seeking racism of white South African cricket coaches and players in the post-Apartheid period. From Brian McMillan’s instructions to bowl an Indian batsman a “coolie-creeper,” to Craig Matthews’s description of Paul Adams’ bowling action deriving from him “stealing hub caps off moving cars,” to Bob Woolmer and Mickey Arthur’s insistence on picking players only for “cricketing reasons,” Desai illustrates how so-called non-racialism disguises direct individual and system racism that has been at the core of post-Apartheid South African cricket. Even players that perhaps cut more sympathetic figures, like Alan Donald, participated in rebel tours during the boycotts.

Sports journalism and the padding of history

Astonishingly, through a deliberate retelling of history by the white cricketing establishment, and a smooth transition from white players participating in rebel tours into media pundits, commentators and journalists, Desai describes how this history – and even this present – has been deleted.

We have written before on this blog about the racism in contemporary South African cricket journalism, but Desai’s book reveals that such incidents are merely a continuation of a long-term and elaborate journalistic project to soften the writer’s own complicity with Apartheid. Iconic white players who are memorialized in South African cricketing folklore, such as Barry Richards and Graeme Pollock, willingly participated in rebel tours with enough political consciousness to threaten to boycott games if they were not paid equally to touring teams, yet they somehow lacked the conscience to consider the inequality of Apartheid South Africa and the total absence of black players on their teams.

Desai reveals too that many household favorites over the last two decades of cricket on television and radio were in fact players on rebel tours who either actively supported Apartheid or were willing to play in support of it for their own financial benefit. Hidden in the public eye are the likes of Mike Haysman, Geoff Boycott, Robin Jackman, Kepler Wessels and Colin Bryden. Their justifications for their actions are not even requested by the South African public who accept on good faith their friendly faces, cricket expertise and detailed knowledge of South African cricket. It is no wonder that when they draw on history these voices choose to regret the tragedy of players like Richards and Pollock not being able to play test cricket rather than reminiscing about the total obliteration of black cricket and the erasure of players such as Baboo Ebrahim, Suleman Dik Abed, Krom Hendricks and Basil D’Oliveira.

Bryden, whose voice for many of us remains synonymous with South African cricket because he has narrated so much of it over the radio, himself worked both as a journalist and for a promotions company supporting rebel tours. Though Bryden may have believed that he was acting in the best interesting of South African cricket, Desai concludes decisively: “for people like Bryden, South African cricket was essentially white cricket… Bryden makes the seamless journey from propagandist to journalist and back again.”

Black s kins, white helmets

Perhaps the weakest part of Desai’s book is its lagging analysis of modern developments afoot in South African cricket. For example, although he analyses the problematic underrepresentation of South Africa at every world cup between 1992 and 2011, there is no analysis of the 2015 World Cup. Nor does Desai deal in any meaningful detail with the impact of recently expanded quotas at both national and provincial levels.

Desai broadly characterises two present positions on racial transformation in South African cricket as the “colour-blind non-racialists” and the “racial bean counters.” He accuses the latter of “aggressive African nationalism,” “chauvinism” and “almost messianic drive” to include more black faces in the South African team at any cost. With an eye on a bottom-up, grassroots driven approach to the development of cricket in South Africa he supports the resurrection of a “militant non-racialism,” an “idea that places both the idea of racial transformation and class privilege centre stage.”

In our view, Desai is too harsh on quotas and too willing to support a radical construction of non-racialism that has never genuinely existed in South Africa. Although noting at least once that “quotas were necessary to force selectors to divest themselves of prejudicial thinking and make the objectively correct cricketing decision,” Desai appears at points to conflate the laudable politics and pragmatism of quotas with those opportunistic politicians who promote them. Indeed, the astoundingly quick turnaround of South African cricket over the last year since Sports Minister Fikile Mbalula imposed a ministerial ban on hosting or bidding for major events until Cricket South Africa met its own transformation targets, is telling.

The problem has never been a lack of black interest in or ability at cricket. The problem, is, and has always been, the willingness of the large, white-run old boys network – of which Bacher was the key protagonist – to manipulate black interest for white gain, all the while professing to be acting in the interests of black cricket(ers).

Batting in uncertain times

Desai’s book reflects lifetime passion for cricket and his deep disappointment with its administration and the way it has served black South Africans. That conflict is intimately familiar. We also both grew up loving the game of cricket despite, and sometimes unconscious of, its whiteness. We were devastated by Hansie Cronje’s betrayal and delighted by the achievements of Graeme Smith’s team and the emergence of black talent such as Makhaya Ntini, Herschelle Gibbs and Paul Adams.

As we have become conscientized, it has been disturbing to recognize the casually biased views of many powerful people within the cricketing sphere towards black cricketers and their open hostility towards discussions of race in cricket. We regret the treatment of black players such as Lonwabo Tsotsobe, Aaron Phangiso, Vernon Philander, Thami Tsolekile, Charl Langeveldt and Garnett Kruger, and the South African cricketing public’s insistence that world class players like Hashim Amla and Temba Bavuma have to prove themselves over and over again.

This book reminds us of the personal responsibility for reflection (if not conscientization), particularly within the elite circles that continue to control access to resources and opportunities for others. Transformation requires insiders (and their children) from the old system to understand and interrogate their privilege, particularly because South Africa has entrenched systems that require bottom-up and system-wide transformation. This starts with a proper appreciation of the dirty history of South African cricket and how corrupt white officials, players, coaches and journalists have contributed to reproducing it.

As cricket fans, we have not been merely betrayed by Hansie Cronje or Dr Ali Bacher. We have been betrayed by whiteness. That is the story of South African cricket in post-Apartheid South Africa. We applaud Desai for telling it.

May 29, 2017

Blaxploitation, Italian style

The Eritrean-Italian actress Zeudi Araya who appeared in number of Italian films in the 1970s.

The Eritrean-Italian actress Zeudi Araya who appeared in number of Italian films in the 1970s.Italian cinema is renowned the world over for its technical and artistic innovations, from the neorealism of De Sica and Rossellini to the surrealism of later Fellini, or the radical sexual explorations of Pasolini to the anti-colonialism of Pontecorvo. Consistent throughout this rich legacy of cinema however, but scarcely remarked upon, is the presence of black folk in both minor and major roles.

The stories of these actors, several uncredited in their early films, remained largely untold until the 2013 publication of film scholar Leonardo de Franceschi’s comprehensive, edited volume L’Africa in Italia: Per una controstoria postcoloniale del cinema italiano (Africa in Italy: A postcolonial counter-history of Italian cinema). This book, along with filmmaker Fred Kuwornu’s own experiences in the Italian film industry as both an actor and a director, inspired the documentary Blaxploitalian: 100 Years of Blackness in Italian Cinema.

Kuwornu’s documentary is equal parts individual narrative, detective film, film studies lesson, and call to action. It asks, who are (or were) these actors? What do their experiences, and the roles they played, say about race and national identity in Italy? And what can be done today to ensure that Italian cinema reflects the increasing diversity of Italian society?

Kuwornu is an Italian-Ghanaian filmmaker who was born and raised in Bologna; he now resides part-time in New York City. A student of political science, he was inspired to begin documentary filmmaking after acting and working as a set assistant for Spike Lee’s 2008 film Miracle at St. Anna, about African-American soldiers in Italy during World War II. He produced two acclaimed documentaries prior to Blaxploitalian: Inside Buffalo, about the African-American soldiers of the 92nd Infantry Division who served in Italy during World War II, and 18 Ius soli, about the children of immigrants born in Italy and their struggles for Italian citizenship. [Full disclosure: I have known Fred since 2013, and assisted with the translations for Blaxploitalian.]

Blaxploitalian explores the stories of Afro-Italian, African-American, and Afro-Caribbean actors whose roles helped to shape the Italian film industry. Beginning in 1915, when the first black actor appeared in an Italian film, the documentary’s “one hundred years of blackness” spans Eritrean actors who arrived to Italy after the dissolution of the Italian Empire and African-Americans who found greater opportunity in the Italian film industry than in the United States (the documentary even shows a jaunty 1954 article from Jet Magazine entitled “Italy’s Movie Boom for Negro Actors”). Kuwornu manages to track down and interview many of these actors, including Denny Méndez, the now Los Angeles-based Dominican-Italian actress and model who shocked the nation when she was crowned Miss Italy in 1996. These engrossing interviews are interspersed with conversations with Italian film scholars such as Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Leonardo de Franceschi about the multiple inflections of blackness in Italian cinema (the “exotic,” the “native who must be subjugated,” etc.) and the relationship between cinema, colonialism, and nation building.

Toward the end of Blaxploitalian, however, the tone of the documentary shifts. Kuwornu shows that Black folk in Italy are increasingly taking roles behind the camera; they are also pushing for more equitable (and less stereotypical) representation. Actor after actor in the documentary describes the humiliation of being asked to put on an exaggerated “African” accent for a role, or only being called to audition for the part of the nanny/prostitute/terrorist/undocumented migrant.

One actor in particular recounts the mind-bending story of auditioning for the role of a southern Italian, and then being told that he looks more North African – but later, when he comes in to audition for the role of a North African, he is told that he looks too southern Italian. For every Black actor who is told that he is too “African” to play the part of an Italian, another is told that she is too “Italian” in her mannerisms to play a character of African descent.

Fortunately, this double-bind is slowly beginning to give way as Afro-Italian actors gain momentum in their advocacy for roles that reflect the “everyday multiculturalism” of Italian society. Igiaba Scego, for instance, describes the significance of Ethiopian-Italian actress Tezeta Abraham’s role in the television series E’ arrivata la felicità’:

Tezetà plays the role of Francesca, a woman who works in a children’s bookstore, and is not too lucky with men. A sort of Black Bridget Jones, with multicolored sweaters that would make the real Bridget jealous… Furthermore, her Roman accent, combined with her rough voice, “rocks,” as the young people might say. It rocks indeed, symbolically linking her to the tradition of the best Italian films, in which Cinecitta’ studios were transformed into city outskirts, into narrative, into life… Tezetà’s Francesca is important for another reason: she is a mirror for many Afro-Italian girls who work, study, and love in this Italy, which is more and more mixed even if it doesn’t see itself that way. Italy tells very little, especially on TV, about the changes it has undergone since the 1970s.

Fred Kuwornu has asserted elsewhere that new media tools such as crowdfunding and social media, along with the increasing accessibility of digital media filmmaking tools, have also contributed to this growing pluralism, since it has become easier and more affordable for people to tell their own stories (instead of waiting for major media outlets to take notice).

Blaxploitalian is part of a broader media diversity campaign entitled “United Artists of Italy,” which Kuwornu has spearheaded along with several other Italian creatives. In addition to this project, activists in Italy have recently advocated for less stereotypical depictions of the African continent, and for laws that would require more equitable representation on television. These campaigns have brought national attention to the pervasive sexism and racism in Italian media –from the use of blackface in a video published by the website of the national newspaper La Repubblica, to the racially-charged imagery of laundry detergent commercials (as documented by Cristina Lombardi-Diop), to a recent segment on the national RaiUno television channel about the benefits of “choosing a girlfriend from the East.”

Of course, media diversity is not just an Italian issue; the work of Kuwornu and his colleagues is inspired by and interwoven with similar initiatives elsewhere: #OscarsSoWhite in the United States, as well as the work of Idris Elba in the UK and Omar Sy in France. But one could argue that there is a particular exigency to the situation in Italy, in which the ongoing refugee “crisis,” the obstruction of a legislative proposal to grant citizenship to the children of immigrants, the rise of the far-right, and economic stagnation have conspired to produce an especially virulent brew of anti-Black racism all’italiana. In this context, Blaxploitalian implicitly argues, representation matters.

May 26, 2017

Linton Kwesi Johnson and Black British Struggle

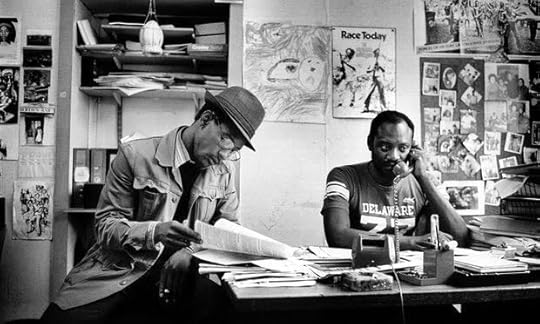

Linton Kwesi Johnson and the late Darcus Howe at the offices of “Race Today.” Photo Credit: Adrien Boot.

Linton Kwesi Johnson and the late Darcus Howe at the offices of “Race Today.” Photo Credit: Adrien Boot.Linton Kwesi Johnson, the Jamaican-born British poet and reggae artist, memorialized bblack power and immigrant rights movements in the UK of the 1970s and 1980s on records such as “Forces of Victory,” “Dread, Beat and Blood,” and “Bass Culture.” LKJ was deeply involved in those struggles not only as an artist but as an activist and intellectual. Entering politics through the youth section of the British Black Panther Party in Brixton, he went on to join the “Race Today” newspaper collective. There, along with Darcus Howe, who passed away last month, and other black British radicals he helped reflect, amplify, and organize black and Asian community resistance to police abuse, National Front skinhead attacks, and systemic racial exclusion in British society. In this interview, the originator of dub poetry talks the role of culture in politics; antiracist and class struggle in the UK; and the importance of a wide range of figures from Althea Jones-Lacointe and CLR James to Ken Booth and the Last Poets.

Music clearly played a big role in the antiracist struggle here in the 1970s and early 1980s. Could you talk about how black British youth identified with Jamaican music and its relationship to their own struggles?

All right, let me put it this way; reggae music was the umbilical cord that connected my generation of Jamaican youth to Jamaica. It provided us with an independent identity. It was rebel music and we identified with it because my generation was basically the rebel generation, as opposed to our parents who were more conformist. We were the rebel generation and Reggae music was our music. It afforded us an identity, it provided us with the nexus of a culture of resistance to racism in Britain. A lot of the lyricism that came out of those Reggae tunes were couched in Rastafarian language of anti-colonialism and the image of the rude boy. We identified with that image, the rebel image.

So, reggae music was crucial for us, in terms of self identity and in terms of consciousness, really, because a lot of the songs that we were listening to as youth, like Ken Booth’s “Freedom Street,” for example, we could identify with the lyrics of that. And when Bob Marley sang about “Concrete Jungle,” we could identify with that concrete jungle. We have our own concrete jungles here in Britain and London, in Manchester and Birmingham and so on and so forth.

Your own poetry is often concerned very with local conditions in England, in London. It must have circulated among British youth as well during this time. Did you see a relationship between culture and politics? I know that you were also the arts editor at Race Today. Do you understand culture to be part of politics?

Absolutely, that was our position that there was a cultural dimension to political struggles and that cultural activism went hand in hand with political activism and they complimented each other. We got those ideas from Amilcar Cabral for example, from Guinea. Yeah so yes, in fact a lot of people became politicized through culture.

C.L.R James was also very influential, is that right?

Yes I was one of C.L.R James’, one of the people who helped to look after C.L.R James during his last days. He lived with us, he lived upstairs on the top floor of the building that housed the Race Today collective of which I was member. And I spent quite a bit of time with him, sitting by his bedside and chatting and all of that. Yeah so James is, but of course you know James was a renaissance man and he was into Michelangelo and Keats and Shelley and Shakespeare and all of that but he understood and appreciated the artistic and the cultural expressions of the working class and the peasantry. I remember he wrote an article for us on Ntozake Shange for example. And he could talk for hours about the calypsos of the Mighty Sparrow and so on.

When Bob Marley came to live here after the assassination attempt in Jamaica and was here recording “Exodus”, he was packaged by Chris Blackwell and Island Records as a kind of a commercialized rock star. But did his presence here have any effect on black British youth?

Bob Marley had a huge effect on black British youth because he was a reggae star artist from Jamaica who was being treated like a rock star. And there was great joy that this was happening amongst young black people. There was a great joy that this thing was happening. At the same time, some of us felt a little bit resentful that our reggae artist from Jamaica was being appropriated by the rock world. You know? He belonged to us. He didn’t belong to white people. He was a black reggae artist, he was no rock artist.

But, by and large, Bob Marley’s success gave a fillip, stimulated British Reggae music. So there was generated greater interest in reggae music. And a lot of black youth who weren’t so much into reggae, because they wanted to distance themselves as a second generation from the roots of their parents. And they felt they were more sophisticated or whatever, or they had petty bourgeois aspirations or whatever. They were more into American music. Bob Marley converted those people to reggae (laughs). And it was on the back of the success of Bob Marley emerged bands like Aswad. Existing British reggae bands like Matumbi and Steel Pulse kind of took off and got record deals with some of the major record labels. I myself got signed to Island Records on the wave of all of that success. Yeah, so reggae was very important in terms of its influence on my generation of youth.

Bob Marley was a deeply, deeply spiritual person, there’s no doubt about that. He was a Rastafarian, but Rasta is part spiritual and part political, you can’t talk about Rastafari without talking about politics and you can’t talk about Rastafari without talking about spirituality because they’re both things. In fact I would say that Rastafari was and is a kind of spiritual response to the anti-colonial struggle or it was a way of expressing the anti-colonial sentiments, our section of the black population. Bob Marley was essentially, as I said a deeply spiritual person, but he was a Pan-Africanist, a Garveyite, and one only has to listen to the lyrics of his songs to realize that he was a political animal.

The CIA would not have opened a file on Bob Marley had he been, you know, non-political. You look at songs like “Burnin’ and lootin’ tonight,” “Get up, stand up,” there’s a song on “Uprising” where he urges the listener to rebel he says “We’ve been trodden on the wine press far too long, rebel, rebel.” In “Africa unite” he talks about African unity and that sort of thing so yes Bob Marley was deeply spiritual and also political. He wanted to distance himself from local politics in Jamaica but I mean in the early 70s he was on the bandwagon, the cultural bandwagon that the People’s National Party rolled out in the 1972 election. The attempted assassination was because he was seen to be an asset for the PNP in the build-up to the 1976 election.

So he was someone who at least amongst the political classes, they felt that he had a … He commanded a tremendous amount of respect amongst the masses and he had clout amongst the masses and whoever had him in their corner had a big advantage. But Bob Marley didn’t really want to be seen as a political partisan in fact in one of his songs I think it’s “Rat Race” he says “Never let a politician do your favor, they will want to control you forever.” But he certainly, as I said if you analyze the lyrics of his songs, you can see that he was a politically conscious person. And I mean in a lot of cases for Bob Marley, the personal is the political. He’s writing a song maybe about a personal grievance but it’s couched in the language of politics.

Did he ever reach out to or have any connection with the local struggles here in England when he was here in the late 70s?

Not that I know of, not that I know of. But I’m almost sure that there was solidarity with our struggles here. But you know of all the Wailers, Peter Tosh was the one who was more overtly political. Peter Tosh got involved in demonstrations, got locked up by the police and beaten up by the police. He was far, far more militant and outspoken than any of the other Wailers.

You had connections with other Jamaican artists and Jamaican poets. Mikey Smith was here for some time in England and you were close.

I brought Mikey Smith over from Jamaica. I’d met him in 1979 when I’d done a couple of shows in 1979 for Peter Tosh. Used to have these youth consciousness concerts once a year and 1979 I did two gigs with him, one at the Ranny Williams Center in Kingston and one in Hellshire Beach. I was part of a line up that included Black Uhuru, The Tamlins, I can’t remember who else was on the bill, I was the opening act, in those days I was playing with backing tapes and dancers. I didn’t bring the dancers to Jamaica with me so I only had the music, what they called playback.

Anyway cut a long story short, it was on that visit to Jamaica that I was sought out by Mikey Smith and Oku Onuora both of whom were students at the Jamaica school of Drama. And Mikey I think was specializing in directing, anyway they sought me out and they found me and we just hit it off and for me it was wonderful to know that there was a school of poetry in Jamaica which was based on a revival of orality in Caribbean poetry. And that saw itself within the tradition of reggae music. In the same way that you had blues poetry or Jazz poetry in America and it gave me a great sense of validity because I was plowing a lone farrow here in England at least so I thought. But when I went to Jamaica and heard these guys Mikey Smith and Oku Onuora, came and said “Yes there are other people doing what I’m doing,” and it was great.

In fact I coined the term dub poetry but I was using that to describe the art of the Reggae djs like U-roy and Big Youth and so on. But Oku Onuora was the one who kind of conceptualized the idea of dub poetry as a term to describe this new movement of orality in Jamaican poetry. So Mikey wanted to know … These guys were looking at me as if I was some kind of big star in England and I could open up the doors to success for them. Anyway cut a long story short, I had founded or co-founded a company called Creation for Liberation and through Creation for Liberation I was able to invite Michael Smith to England to do a poetry tour and he also performed at the first international book fair for Radical Black and Third World books in 1982. And I also released Mikey’s record ‘Mi Cyaan believe it’, ‘Mi Cyaan believe it’ and Roots on my record label LKJ records in fact it was the first record I ever put out on my record label.

But the year before that in 1981, I happened to be in Barbados fronting a documentary for the BBC called ‘From Brixton to Barbados’ about the Carifesta, the regional arts festival they have every six years or so and that year it was in Barbados. And Mikey Smith was there in Barbados and Anthony Wall thought it would be a good idea to film him performing his famous poem ‘Mi Cyaan believe it’ which was broadcast on the BBC. So that’s how Mikey got introduced to the British public.

What is it about poetry that makes it particularly suited to political expression?

I don’t know, I haven’t got a clue. All that I know is that I came to politics, I came to poetry through politics. It was as an activist in the Black Panther movement that I discovered something called black literature, books written by black people which I didn’t know anything about before that. And WEB DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk which wasn’t really poetry it was prose but it was very poetic prose, stirred something in me and made me want to write, write verse. So I don’t know but personally speaking I’ve always been attracted to political poetry and there’s some people who would argue this kind of arty-farty notion of art for art’s sake bullshit that politics has no part to play in art which is just a lot of nonsense. I don’t know if it’s because poetry is really about language and how one uses language in a kind of a succinct kind of a way. And you know there’s a musical dimension to it. I don’t know I really can’t answer that question but I’ve always been attracted to political poetry and lyrical poetry and if you look at the canon of British poetry, it’s full of political stuff from Alexander Pope, Shakespeare, Shelley.

Were you influenced at all by The Last Poets or Gil Scott Heron?

Well they were a big influence on me, the last poets were a big influence on me because I heard them when I was in the Black Panthers. I think we had about one or two LPs we used to circulate amongst the youth membership, I was in the youth section to begin with before I became a fully-fledged member. We had Message to the Grass Roots by Malcolm X and it was also had an LP by the last poets that was circulating around and I thought “Wow these guys are using the language of the street as a vehicle for poetic discourse I mean this is fantastic, this is great I want to do something like that with Jamaican speech.” So yeah, they were a big influence on me and this idea of the voice working with percussion, with drums and all of that, I first got an insight into that from the last poets. Yeah they were a big influence.

I found out about Gil later on and me and Gil did a tour of America back in the 80s. We played all over America from New York to Alabama.

His father was Jamaican, I think.

Yeah his father was Jamaican footballer. Played for one of these football clubs. Yeah but me and Gil did a tour of America and I loved his stuff, I think Gil is in that tradition of the Last Poets. But I became great friends of Amiri Baraka who is coming out of that blues, jazz tradition. So I’ve always seen this relationship between music and poetry, I’ve always been attracted to it. Yeah, those guys were a big influence.

So in some ways some of the culture of anti-racist struggle or immigrant rights struggles changed after the insurrections of the early 1980s. Do you think there was a change in kind of the politics and the racial climate for the worse under Thatcher? Did things kind of move in a different direction?

Well, I really don’t know how to characterize that period because it was a period of intense class struggle, class struggle and the racial dimension of that was important. It was a period of anti-fascist struggle and anti-racist struggles. It was a period that saw the rise, well not so much the rise but perhaps the consolidation, of white racism in the mainstream. I think organizations like the National Front lost support because people who may have thought of voting for them thought the conservative government was right wing enough so they would rather vote for the Tories.

It’s a very complex period because I think as an electoral force, the Thatcher period dealt a death blow for the extreme right in this country. It was a period that also saw solidarity, a great solidarity between black and white working class youth. Rock against Racism was a big success and it helped to bring us together. It was period of intense struggle, class struggle as well as anti-racist struggles, it was a period when Mrs. Thatcher came to power with one mission and that was to claw back the gains that the white working class had won for itself in the post World War two settlement and she took on the miners and won and so on and so forth.

The great irony is that after the black insurrections of ‘81 and ‘85, 1985, it was under a Thatcherite government that things began to change for black people. Slowly the emergence of a black middle class that was nurtured by the Tory government under something called the intercity partnership lead by a man called Michael Heseltine who was the minister at the Department of the Environment.

And after, one of the significant things that happened was that in 1981 after the racist murder of 13 black children in New Cross, the New Cross massacre action committee, which was a broad-based organization of activists from up and down the country, we organized on the second of March 1981, we mobilized nearly 20,000 people marching from New Cross to Hyde Park to protest the murders and the way the police had been dealing with it. Handed in a letter of protest to Number 10 Downing Street and so on. It was a watershed moment because it made the British establishment take note of the fact that we had black power and we could mobilize that power and it was during that Thatcherite period that they began to speed up the process whereby a black middle class could emerge. Because before the 1980s black people had been one the periphery of British society, we were marginalized. We come into the Mother country and were treated like fucking third class citizens you know what I mean? We were marginalized. And by the end of Thatcherite period a black middle class began to emerge and by the end of the 20th century we were closer to the center than the periphery.

What were the conditions like in the 1960s and 70s for black Britons?

During the 1960s and 70s for black people, Britain was a very racially hostile place to be living in. Black people were marginalized and treated like third class citizens. In the sixties, I can’t remember in which constituency, in Birmingham for example, the conservative candidate’s slogan was “If you want a nigger for a neighbor, vote liberal or labor,” so that was a kind of, you know… And in the period following Enoch Powell’s famous “Rivers of Blood” speech, you know Powell was a conservative politician who made a bid for the leadership of the Tory party by playing the race card and he advocated the repatriation of black people and all that and made some big speech about rivers of blood and racial war, racial conflagration and all of this kind of stuff, on the back of that there was a rise in racist and fascist attacks against black and Asian people. Racist murders, and during that period the police would deny that racist attacks and racist murders that there was any racial motive what so ever, it was only after the New Cross fire in 1981 that the police began to introduce into their vocabulary the idea of racially motivated crime. In the consciousness of the police, in the vocabulary, it didn’t exist. It was if a white man called a black man a nigger and stabbed him it was just treated as a criminal act.

Even the police themselves were often …

Well during that period, I would say that the National Front and other like racists were indistinguishable from your ordinary police officer because they more or less dealt with black people in the same way. And I mean in the period that saw criminalization of a whole section of black youth belonging to my generation, you know we had the infamous suss law where you’d be arrested and charged with attempting to steal from persons unknown. This vague law, vagrancy act from the 19th century, 1840 something that was used against the black youth of my generation. But it’s also a period of self organization. We responded by building autonomous political organizations, cultural organizations, began to establish independent institutions, like for example this year 2016, this year marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of New Beacon books, the first Black publishing house and book seller in this country.

It was around that period too that saw the formation of the Caribbean artists’ movement, founded by people like John La Rose who was the founder of New Beacon, the Jamaican novelist and broadcaster Andrew Salkey and the Bajan poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite. Two years later in 1968, Bogle-L’Ouverture, another black bookseller and publisher was also founded. So you know we began to build political organizations, the Panthers, Panthers was founded in 1967 although it was first called United Colored Peoples Association before it became the Black Panthers.

Lots of black power … Late sixties was a black power period. We had an eye on what was going on in the United States of America, our parents were more like Martin Luther King followers, we were more like Malcolm X followers and so we had lots of black power organizations, not just here is London or where the Panthers were based but in Nottingham, in Bristol, in Birmingham, in Manchester, organizations up and down the country. That is why were able to mobilize so many people, nearly 20,000 people when the New Cross fire happened in 1981 because we had already built this network of organizations up and down the country. So it was a period of resistance, it was a period of fight back, it was a period of building.

You had built autonomous black institutions and then were able to also mobilize white solidarity once New Cross happened, is that right?

Well there was always some solidarity amongst white people from going back from the early days, you know? Progressive people on the left of the labor party for example. And there were always decent people amongst white working class as well. It was not that everybody was a racist you know, there was decent white people as well but racism was endemic and still is in British society. Amongst those independent autonomous institutions that we built, were churches, because we weren’t welcomed in the white churches when we came here, especially the Anglican churches. The churches of the working class like the Methodists would be more accommodating but you go to an Anglican church and if you weren’t told directly by the vicar after the Sunday service that you’re not welcome there, you pick up the vibes anyway and people began to so black people started their own churches. As a matter of fact in 2016 now I think that the most organized section of the black community in this country are the churches.

How did you connect the Panther idiom with the British black struggle in that period – with the British version of black struggle as opposed to the US one?

Well you know the black struggles that were going on in the 60s, 70s really cannot be localized because black power was everywhere. There were anti-colonial struggles being fought in Africa, for example, against the Portuguese for example, there was anti-apartheid struggles going on in South Africa, there was struggles for, anti-colonial struggles going on in Zimbabwe, Rhodesia, these things were in the news. People like Martin Luther King came to this country and visited. We had people like Malcolm X came over here and visited. I don’t know how the Black Panthers actually started because I joined relatively late but it was an African brother called Obi Egbuna who started it. So we understood, we were aware of what was going on in the United States of America, we identified with those struggles being waged in the United States of America, even in the Caribbean, in Jamaica, in Trinidad, in Barbados, we knew all about all those struggles.

When we came here, it was a rude awakening for a lot of us and um, you know in my parents’ generation, they identified…you know in a lot of West Indians’ homes you would go and you would see a picture of white Jesus on the wall, you would see a picture of Martin Luther King and you might even see a picture of J.F. Kennedy on people’s walls you know? We were aware, my parents’ generation were aware of and identified with the civil rights struggles that was going on in America and so parallels between what was going on over there and what was happening to them here. My generation, we were more militant, we were the rebel generation and we identified with the Black Panthers in America. We weren’t into this kind of doctrine of non violence preached by Martin Luther King, we adopted Malcolm X’s slogan “Freedom by any means necessary,” fire for fire and blood for blood you know and that was it. So that’s how it was.

Can you just say what your involvement was in the English Black Panthers and where it was operating from?

The Black Panthers, I was a member of the Brixton branch of the Black Panthers movement, we had branches in West London, North London and South London and I was in the Black Panthers in South London. And our leader was a remarkable woman called Althea Jones-Lecointe who is a consultant gynecologist or something now in some big hospital. In those days she was doing a PhD in biochemistry, brilliant woman. She came to my secondary school and gave a talk and I think that’s what made me curious about the Black Panthers and I started going to their meetings and asking questions and so on. And I thought well, I want to be a part of this movement. My activities included going from door to door to try and get people interested in the organization, I would kind of campaign and we had campaigns as well, for example, a man called Joshua Francis was beaten up, badly brutalized by the police and there was a campaign for justice going on. I would be involved in those campaigns, attending demonstrations. Saturday afternoons or Saturday mornings I would be either in Brixton market, Balham market or Croyden market selling our newspaper, the Black Panther paper. We had direct links with the American Black Panthers we used to sell their papers too. In fact Angela Davis came over and visited us at one stage. And I got my political education in the Black Panthers, you know? We studied books like C.L.R James’s ‘The Black Jacobins’ – a history of the Haitian revolution lead by Toussaint L’Ouverture, we studied that. We studied books like Eric Williams’ ‘Capitalism and Slavery’. We studied books like E.P Thompson’s ‘The making of the English working class’, we studied ‘Black Reconstruction’ by W.E.B Dubois you know some serious education that I wouldn’t have gotten otherwise.

Can you describe the scale of the Black Panthers?

I don’t know, I wouldn’t really hazard a guess but we had two sections in the South London chapter, we had the youth league and the Black Panthers. As a youngster I couldn’t have just become a Black Panther like that, I had to join the youth section first and kind of serve like an apprenticeship and then you became a fully fledged member and it was kind of a hierarchical structure. You had a central core and so on, but all I can tell you is that we had a chapter in Brixton, we had a chapter in West London and we had a chapter in North London and we had connections with other like-minded organizations in London in Nottingham, in Birmingham, Manchester and so on and so forth. There were organizations, I can’t even remember the names of some of them. In London we had other organizations like the Black Unity and Freedom Party, you had SELPO, South-East London people’s organization. I can’t remember all of them but our membership but our presence was greater than our membership. I mean you might not have had more than 100 people as signed-up members in a particular branch of the Panthers but the support and the people you could mobilize would be ten times that or 20 times that. Or people who came to meetings who were not fully fledged members but they came to meetings anyway. So in terms of numbers I wouldn’t really hazard a guess.

I remember seeing footage one time of James Baldwin coming here in 1968 speaking at the West Indian Center. Was Baldwin someone that people read or talked about?

Of course, you know I remember I was running a bookstore outside a record shop in Brixton as part of my activities when I was a part of the Black Panther youth league, and was minding the book stall. Books that we got from New Beacon books, we had a store right outside Desmond’s Hip City record shop in front of the Atlantic pub at the Junction of Atlantic Road in Coldharbour Lane, a little bookstore there selling these books. And James Baldwin came down to Brixton and he came to the book store and I remember showing him, James Baldwin, a copy of his own book The Fire Next Time!

May 25, 2017

A different kind of girl power

In recent years there has been a global convergence on the “girling of development”; in other words, girls’ empowerment and education as a way to address poverty. This includes corporate campaigns such as Nike’s Girl Effect and those by state aid organizations such as USAID’s Let Girls Learn. These campaigns promote understandings about girls’ empowerment that portray girls as individuated selves who can overcome structural difficulties – such as poverty and disease – if they only re-invent themselves by working hard, staying in school, delaying marriage and entering the workforce. This kind of “girl power” assumes an autonomous girl-subject who must rely on herself to improve her circumstances. This attention to the individual deflects attention from the role of the state, foreign policies, consumption patterns in the global North, as well as capitalist relations that exacerbate poverty in the global South. Poverty appears to be a personal problem rather than a political one.

Such storylines devolve into blaming local culture, families, and/or religious communities for the direct and structural violence that girls experience in the global South. The portrayal of Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai in Western media often blames the entirety of Muslims and the nation of Pakistan for the bad behavior of the particular members of Taliban who attacked her. What we have then is a simultaneous elevation of the individual as the site of power and the demotion of the collectivities to which she belongs. These logics are deeply problematic because they shift blame to local entities (families, for instance) that, too, are enveloped in poverty due to capitalist relations. Furthermore, such logics mark religions and religious communities as irrelevant to modern times. Hence, one of my preoccupations has been to reclaim religion/families/cultures from these tired portrayals and excavate alternate evidence. Queen of Katwe, a Disney production directed by Mira Nair, provides one such intervention.

Queen of Katwe official trailer

The film Queen of Katwe traces the life of chess champion, Phiona Mutesi, who lived in the shantytown of Katwe in Uganda. At the age of nine, she enrolls in a chess program managed by a local church ministry, enticed by the free cup of porridge that is distributed to students there. Through perseverance and practice, support from her mother, and a tenacious coach, Phiona goes on to win the national championship. Hers is, indeed, a story of triumph against insurmountable odds; a life-script that, perhaps, is not accessible to many girls in Katwe. However, the movie makes a range of interventions in the conventional wisdom about what constitutes education and points to the need to re-think dominant conceptualizations of “girl power.”

Phiona did not go to school and yet she was able to reason her way through the rigorous sport of chess. We, hence, immediately encounter a girl who succeeds outsides the context of formal schooling. Next, religious institutions and ethics inspired by religion play a crucial role in the lives of the characters. Phiona, for instance, encounters chess through a Christian sports outreach ministry that runs various programs for underprivileged youth in Katwe. The program provides sports but also feeds kids, a service that is crucial in the context within which Phiona lived. We also observe what a life lived in the service of others looks like in the character of coach Robert Katende. Hired only in a part-time capacity because that is all the church can afford, Katende is later offered an engineering job, which he declines to continue working with the Pioneers (his chess students). That is his life’s work.

In addition to highlighting the role of religious institutions in improving the lives of the most marginalized in society, we encounter Phiona’s mother, Nakku Harriet, who provides a glimpse into yet another support system for Phiona. Nakku, who is widowed and has four children, is fiercely protective of her family and works hard to provide food and shelter. Even though events beyond her control lead her older daughter, Night, to get pregnant early, Queen of Katwe develops the characters of Nakku enough for the audience to not devolve into blaming the mother for the daughter’s transgression.

Significantly, it also develops Night’s character – through scenes that show that she cares for her family, particularly Phiona – to avoid marking the black girl as a site of hypersexuality and promiscuity. Indeed, Nakku and Night’s life circumstances present complicated options linked to survival, which resist reduction to stereotypes. Likewise, we meet supportive friends and siblings who are equally crucial in Phiona’s ascent.

Phiona’s story of triumph then is not the triumph of the autonomous, empowered girl who single-handedly beats the odds and moves out of the slums. Rather, it is a story about interdependencies, where religious institutions, community, siblings, a well-wishing mother and religiously-inspired ethics all play a role in creating moments of relief. Such complex portrayals of black girlhoods call on the audience to re-think assumptions about success and girl power.

Yet, Queen of Katwe also shows how individuals’ as well as communities’ capacities for action are mediated by structural constraints – gatekeepers in the form of state officials and school masters, or fees to enter chess tournaments. We thus leave the movie with a understanding that improving the lives of girls in the global South entails not only resisting the demonizing of their cultures, families, and religions but also paying attention to the structures that limit their opportunities.

May 24, 2017

Take me to your leader: Eritrea’s Isaias Afwerki

Donald Rumsfeld and Isaias Afwerki. Image via Wikicommons.

Donald Rumsfeld and Isaias Afwerki. Image via Wikicommons.Despite all that’s been written and spoken about extreme repression and economic blight in Eritrea, surprisingly little has been publicized about its inscrutable leader, Isaias Afwerki, who has led the country with an iron fist since independence in 1991. Based on common knowledge among Eritreans in the country and other information that I have collected over the years from frequent contacts, I am attempting to profile him.

Having closed all independent media and banned international correspondents, President Afwerki rebuilt the national media to exclusively serve his own interests and ambitions. In regular interviews with the state media, he approves all questions beforehand. In the midst of interviews, he often takes over, addressing a single question with lectures that ramble on for 30 minutes or more. The journalists’ only role is to help him transition between topics and occasionally nod in approval or agreement. Once during a pre-recorded interview, one of the “journalists,” Asmelash Abraha, fell asleep during the president’s long reply. In his regular interviews with the state media, Afwerki talks at leisure and analyzes many world developments. During an interview on the national broadcaster, Eri-TV, journalist, Temesghen Debessai, asked the president questions interchangeably in three languages, Tigrinya, English and Arabic. Afwerki talked about a variety of issues, demonstrating his command of language, history and current events for his Eritrean audience.

Afwerki appoints and fires ministers unpredictably and erratically. Journalist Seyoum Tsehaye tells a story about his encounter with Afwerki before he himself was imprisoned (15 years later he is still behind bars). Tsehaye, then director of the newly established ERI-TV, was summoned to the office of the president. The two had a heated exchange, and the president demanded he leave. Before Tsehaye reached his own office, Afwerki had called Tsehaye’s immediate supervisors to effectively freeze him from his job.

Similarly, Andebrhan Welde Giorgis wrote in his book, Eritrea at a Crossroads: A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal and Hope (2014), that a disagreement he had with President Afwerki when he was governor of the national bank resulted in the sudden appointment of Tekie Beyene to take over his position. He was instructed to vacate his job the same afternoon.

Another example of Afwerki’s arbitrary and abrupt nature in dealing with underlings in his government involved the National Holidays Coordinating Committee. This is the key office that undertakes all national celebrations, including planning and carrying out propaganda. When some of the performances at the Independence Day celebration of May 24, 2010, displeased the president he ousted Zemhret Yohannes, the committee chair and a longstanding executive member of the ruling party.

Later, Afwerki appointed Semere Russom, minister of education, to chair the committee. Barely a year into his term, Russom returned from a trip to China to learn that his position had been taken over by Luel Ghebreab, then chairwoman of the National Union of Eritrean Women (NUEW). Ghebreab herself fell out of favor the next year (both as chair of the holidays committee and chair of the women’s association) and was replaced by Zemede Tekle.

Afwerki is notorious for not providing clear directives when he appoints people to a new position or to launch a big program. Frequently, he meets with people and approves directives while in his car or walking, or when out-of-town on public holidays. Without having adequate knowledge or a full grasp of the new task, newly appointed officials must navigate their way perilously through trial and error.

In the regular cabinet meeting, ministers take turns to present the quarterly or semi-annual reports of their respective ministries through Power Point presentations. All other sensitive issues are handled autonomously by the president and his favorite (at that moment) officials, mainly from the army and security.

Corruption is not only tolerated but encouraged, and the president uses it to buy loyalty. Relatively incorruptible government officials are considered a potential threat, so Afwerki makes sure he appoints loyal subordinates who will report directly to him.

Since the mid-2000s, the president has started a so-called “tour of inspection” that allows him to personally monitor all development projects across the country. During these tours, he advises or instructs private businesses and hands down directives directly affecting these government projects. Disregarding the expertise of professionals or ignoring them entirely, Afwerki approves projects that cost millions. For example, during the second half of the 2000s, all Eritrea was talking about a dam project called Gerset – a name that became ubiquitous in the national media. Afwerki was the sole architect and engineer for the project, which he launched against the repeated advice of professionals. Although the intended goal was irrigation, after Gerset was built, (not unexpectedly) the whole project proved to be a failure. It sustained massive cost over-runs due to the huge cost of pumping water uphill. Fast forward to today, and the whole embarrassing project has faded away from the collective memory.

The Gerset project wasn’t unusual. President Afwerki often takes on massive but under-researched projects that gobble up a significant material and human resources. Some of the most hyped and now totally failed projects of recent years included a cement factory in Massawa; a banana and tomato-packing factory known as “Banatom” in Alebu (with an Italian investor); the Massawa International Airport; the Massawa Free-trade Zone; and a sugarcane farm in Af-Himbol.

Since 2012 these types of projects have been on the increase. As a likely result, the president spends less and less time in his office. Instead he handles domestic issues by phone from his current work place, and leaves international affairs to his political adviser, Yemane Ghebreab.

One recent project to which Afwerki devoted his time was the Kerkebet dam, about five hours west of the capital. With the grand idea of developing drip irrigation, he relocated to the site and spent all his time closely monitoring and supervising construction. Army recruits and construction workers toiled away in three daily shifts, which meant using ample electricity at night (which is unusual in Eritrea).

After the Kerkebet project was finalized in a relatively short time around 2012, Afwerki moved to another, bigger construction site known as Gergera, about an hour’s drive south of the capital.

Gergera Dam – intended to be used as a source of water for most of the country’s southern region and extending to the eastern lowlands – started in the second half of 2013. The project coincided with the new “popular army” scheme of 2012 that required all citizens, including civil servants, to contribute free manual labor. Makeshift tents were erected and food rationed while most civil servants and civilians spent their days collecting stones. Except for ministers, mothers and married women, all nationals including celebrities such as singers and athletes had to provide free manual labor. The president and officials in his favor at that time would closely monitor every development, constantly assessing the level of loyalty shown by the laboring citizens.

As the physical project of Gergera was about to end, Afwerki shifted interest, and in 2014 started yet another similar project, in Adi-Halo, about a half-hour’s drive from the capital. (A simultaneous project, Gahtelay, is in progress in a different location). The president still maintains the tradition of moving his offices periodically. This time he moved his office to Adi-Halo, both working as site manager and running the every-day functions of national government.

In Adi-Halo, President Afwerki has been working tirelessly to adjust government salaries. With a few handpicked and seasonally favored assistants, and of course without any consulting professionals, he has been employing an unconventional matrix to restructure the salary scale. It consistently fails to meet his expectations. Thus, government employees are earning a disproportionate amount of monthly salary despite the fixed scale. In his traditional New Year’s interview, he acknowledged that this project will take some time.

Afwerki also has been working diligently to manage the financial chaos he himself created. The Eritrean national bank changed its currency note toward the beginning of 2016, as part of a controversial currency replacement program.

Under the program, nationals are only allowed to withdraw up to 5,000 Nakfa of their savings in any given month. It requires that all transactions above 20,000 Nakfa be handled through bank checks despite the fact that checks are not widely used in Eritrea. Only three people in the country can verify and approve a transaction of more than 20,000 Nakfa, which normally takes about one month to complete. With the high inflation rate, 20,000 Nakfa can buy, for example, just one Samsung smartphone.

Afwerki enjoys and never misses the endless commemorations of major battles that the nation celebrates with great fervor. All top government officials are expected to suspend their work and leave town for days to accompany him. During these junkets, in the midst of his endless jokes and ridicule/praise, officials get a feel for their current status with the president.

In addition to the routine public ridicule and humiliation most officials undergo, President Afwerki is known for physically assaulting top government officials including ministers or national figures, such as journalists. His character is taken as the model and it trickles down the lowest ranks.

Having effectively demolished all public institutions and structures, Afwerki’s character and his legacy will take a generation to fix. As he frequently utters in some private occasions, however, is unfazed. The “country is his sole creation whose existence depends on his personal whim.”

May 22, 2017

The moral imperative on South African farms

Yolanda Daniels is a domestic worker with three children. She has lived on a farm outside of Stellenbosch in South Africa’s Western Cape for more than 16 years with the white farm owner’s consent. Like many other women living on farms, overwhelmingly coloured and black, both the security of Ms Daniels’ employment and housing are precarious and constantly under threat. Both are reliant often on the whims of their male partners or husbands, but mostly of white farm owners and managers.

For several years the farm manager on the farm where Ms Daniels lives, Mr Scribante, sought her eviction through a number of unlawful and indirect means. The final manifestation of these attacks was opposing her attempt, at her own cost, to making necessary improvements to her home such as leveling floors, establishing a system of running water and a washbasin, adding windows and laying paving outside the house.

Prior to this, he had attempted to get her to leave by unlawfully disconnecting her electricity supply, removing the door from her home and simply ceasing to perform his obligation to maintain the premises. On both previous occasions, as a result of Ms Daniels’ tenacity and persistence, the Magistrates Court had come to her aid. On this occasion, however, neither the Magistrates Court in Stellenbosch, the Land Claims Court in Randburg nor the Supreme Court of Appeal in Bloemfontein vindicated her rights.

Ms Daniels, whose rights were recently upheld in a path breaking Constitutional Court judgment, is not alone in having called upon Constitutional Court for assistance in affirming her rights. In Ms Daniels case, the court was clear that both the constitution and the Extension of Security of Tenure Act entitled her to make the necessary improvements required to ensure a dignified home, regardless of Mr Scribante’s consent. But many similar examples exist.

Elsie Klaase, for instance, is a seasonal worker on farm near Clanwilliam. In 2016, after 30 years of living and working on the farm with her three children and three grandchildren, the Constitutional Court upheld Klaase’s application resisting her eviction. This following the Clanwilliam Magistrates Court and the Land Claims Court decisions that Ms Klaase herself had no independent legal right to continue occupying her home on the farm because her husband was evicted after being dismissed from his employment on the farm. The Constitutional Court lambasted the judgments of the lower courts for “demean[ing] Mrs Klaase’s rights to equality and dignity” by only considering her occupation as legitimate “through” or “under” her husband.

Then there’s Magrieta Hattingh, is an elderly woman living on a farm in Stellenbosch. She lived there with her three children and three grandchildren for more than 10 years and had worked on the farm for some of this time. The Magistrates Court, Land Claims Court and Supreme Court of Appeal denied that her right to a family life included the protection of the occupation of her grandchildren and adult children. It took a 2013 Constitutional Court judgment to affirm the validity of Hattingh’s right to family life, because, as it pointed out “families come in different shapes and sizes.”

These three examples illustrate a ubiquitous problem with respect to the precarity of farm workers in general, and women in particular, drawing attention to broader social issues and systems of oppression. First, women living and working on farms find themselves in dual patriarchal relationships: the relationships with their male partners and their relationships with farm owners and managers. Their employment is, by design, often seasonal (and therefore temporary and contract-based). As the cases of Klaase and Hattingh show tenure for them and their families has also been deeply insecure.

Second, the majority of farm owners and managers are white and the majority of farm workers and dwellers are black African or coloured: the legacies of colonialism and

Apartheid are alive and well on farms throughout South Africa.

Third, more than 20 years after the adoption of the constitution and nearly 20 years after parliament’s enactment of the Extension of Security of Tenure Act, legal representation and protection of farm workers’ rights remains the exception, not the norm. It took Hattingh, Klaase and Daniels all several rounds of draining, costly, demoralizing litigation in courts around the country for the justice system to vindicate their rights. This suggests that both the legacies of patriarchy, white supremacy and capitalist worker exploitation may often be reproduced by South Africa’s justice system.

It is in this context of the daily realities of women living and working on farms in South Africa that last week’s watershed Constitutional Court judgment in Ms Daniels case must be appreciated. The court’s judgments reveal the palpable disdain for Mr Scribante’s actions noting that he himself accepted that without the improvements Ms Daniels sought to make, the “dwelling is not fit for human habitation.” It affirmed that, after attempting to reasonably engage Mr Scribante, Ms Daniel’s was well within her right to make improvements that amount to “ordinary, basic, things” without his consent.

But the increased influx of similar conscience-crushing cases that the court has heard in the last few years also led it to make statements of broader importance about the treatment of black farm workers by white farm owners and managers in South Africa. In a judgment written by Justice Madlanga, the court acknowledges importance of land reform and redistribution as a means of “recognizing the injustices” of the past, which include colonial- and Apartheid-imposed systems of racism and sexism. Justice Madlanga affirms the deep physical, psychological, economic and emotional pain that go with such dispossession. His judgment begins with a quote from a farm worker at a community meeting imploring his comrades “we must remember that there is only one aim and one solution and that is the land, the soil, our world.”

It proceeds, therefore, to make it categorically clear that white farmers’ property rights need to be better balanced with black workers rights to dignity, housing and security of tenure. It accepts the vulnerability of black women to evictions despite protective laws noting they are “susceptible to untold mistreatment.” These are important reaffirmations by the court that it will not stand in the way of any efforts to redouble commitment to redistribution of land and wealth. This is of course, if politicians of various loyalties are indeed committed to “radical economic transformation” and claims of “economic freedom.” It invites us to question whether the constitution and judiciary are convenient scapegoats rather than obstructions to transformation as is now so often suggested.