Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 277

July 6, 2017

African military partnerships in the age of the ‘enemy disease’

U.S. Army Africa familiarization nvent on maintenance for Armed Forces of Liberia, Monrovia, Liberia, May, 2010. Image via US Army Africa Flickr.

U.S. Army Africa familiarization nvent on maintenance for Armed Forces of Liberia, Monrovia, Liberia, May, 2010. Image via US Army Africa Flickr.One of the most disturbing developments in the 2013-2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa was the decision, in late summer 2014, to place armed Liberian security forces around Monrovia’s West Point neighborhood. In an effort to contain the disease, the Liberian government deployed an urban warfare tactic against its own citizens. The cordon sanitaire was short lived and tragic: at least one person was killed (Shakie Kamara, shot by officers manning the barricades); trust in the government’s ability to manage the crisis was further eroded; and the action exacerbated the disease’s overall toll on the city.

Just weeks later, President Barack Obama ordered US troops to deploy to West Africa to partner with other agencies in fighting an Ebola outbreak spinning rapidly out of control. Critics decried the use of US forces as first responders, arguing that Operation United Assistance constituted a neo-colonial occupation and represented the securitization of a public health emergency.

But the critical emphasis on large-scale deployments like OUA distracts from careful analysis of a more impacting and worrisome kind of partnership. The fact is that by the time OUA was announced, US armed forces had already had a long partnership with Liberia’s military. Military-to-military relationships have become the dominant mode of US engagement with the African continent, and these relationships are overwhelming cast as institutional partnerships. (To wit, ten of the twelve areas of security cooperation are described by AFRICOM on its website as partnerships.)

In the Liberia case, that partnership is especially close. The peace agreement that ended the long running conflict in 2003 called for the dissolution of Liberia’s national army and its complete reconstitution under US supervision. The agreement outlined a plan to make the new Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) a multi-talented force that could not only perform traditional defensive operations against external threats, but could more importantly “respond to natural (and other) disasters, assist in the reconstruction of [Liberia] and support and participate in regional and international peace.” The goal was to produce a “force for good” in Liberia, as a 2015 Michigan National Guard report put it.

To that end, the Michigan Guard (the lead US military agency in the Liberia relationship for the past several years) has sent public affairs officers, lawyers, medical teams and engineers along with its combat trainers. Liberia has participated in a range of multi-nation AFRICOM institution building programs, including (ironically), an initiative launched in 2008 to help African militaries plan their response to pandemic disease outbreaks. As is the case with a number of national militaries in Africa, military-to-military partnerships with US troops were intended to bolster African forces’ capacity to be first responders to a wide variety of future crises, including the effects of climate change, resource shortages, poverty, proliferating criminal gangs and political corruption.

Yet, in Liberia, as elsewhere across the continent, this broad human security approach to partnering across militaries has in practice been subsumed by preparing for the “kinetic” demands of counterinsurgency. In a September 2016 interview with African Defense, Brigadier General Donald C. Bolduc, the head of US Special Operations Command-Africa (SOCAFRICA) made clear that the non-human challenges facing African partners are simply threat multipliers for the most pressing concern: that “violent extremist organizations” (VEOs) will make use of Africa’s chaos to recruit disaffected youth (especially young men). In other words, the broad human security mandate to which African partner forces are supposedly being supported to respond is, in the end, only of concern to the extent that it enables the more pressing problem of fighting a very human enemy.

This is a worldview in which disease, poverty, corruption and natural disasters are problems primarily because they can be exploited by human enemies. And it is a worldview that continues to prioritize war fighting as the ultimate skill set for both US and partner forces. As a consequence, the capacity of the AFL to be a “force for good” in addressing broad human security goals has been structurally undermined. Sean McFate, one of three DynCorp contractors hired to design and implement the first AFL restructuring programs, has described the gutting of civil/military relations classes from the earliest days of the program. Non-combat peacekeeper training, for example (the kind of training that might have helped stabilize, rather than aggravate, an urban crisis like Monrovia’s Ebola outbreak), has been a consistently underfunded and under-developed aspect of military re-structuring.

It is a problem exacerbated by the tendency to focus not on training African forces in their entirety, but on elite commandoes. Special forces and anti-terror units have received advanced training in specialties like urban warfighting and counter-insurgency at the expense of training the bulk of African partners in skills such as non-lethal crowd control or disease tracking.

“By helping Africans help themselves,” said Maj. Albert Conley III of USARAF’s Counter Terrorism bureau, “it means that we don’t have to get involved ourselves. If Africans are solving African problems, then the U.S. government doesn’t have to use the U.S. Army to solve African problems.” What exactly solving African problems means is generally left unstated in that oft-repeated slogan. But the West Point cordon sanitaire may well be its inevitable, logical conclusion. African military partners are regularly promoted as “forces for good” whose writ is to deal with all manner of threats. But if in practice military partnerships are designed primarily to combat the spread of terrorist networks, to keep Africa’s perceived chaos in its place, then urban warfare tactics like the armed cordon will be the only response to every problem – human, environmental, or pathogen.

* This series of essays emerges from a project based at the University of Washington that explores “partnership” as a programmatic priority and affective ideal in initiatives between the United States and African countries. We consider the politics of partnership in three different realms of US-Africa relations: military training and disaster relief, reproductive health initiatives and study abroad programs.

African military partnerships in the age of the enemy disease

U.S. Army Africa familiarization event on maintenance for Armed Forces of Liberia, Monrovia, Liberia, May, 2010. Image via US Army Africa Flickr.

U.S. Army Africa familiarization event on maintenance for Armed Forces of Liberia, Monrovia, Liberia, May, 2010. Image via US Army Africa Flickr.One of the most disturbing developments in the 2013-2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa was the decision, in late summer 2014, to place armed Liberian security forces around Monrovia’s West Point neighborhood. In an effort to contain the disease, the Liberian government deployed an urban warfare tactic against its own citizens. The cordon sanitaire was short lived and tragic: at least one person was killed (Shakie Kamara, shot by officers manning the barricades); trust in the government’s ability to manage the crisis was further eroded; and the action exacerbated the disease’s overall toll on the city.

Just weeks later, President Barack Obama ordered US troops to deploy to West Africa to partner with other agencies in fighting an Ebola outbreak spinning rapidly out of control. Critics decried the use of US forces as first responders, arguing that Operation United Assistance constituted a neo-colonial occupation and represented the securitization of a public health emergency.

But the critical emphasis on large-scale deployments like OUA distracts from careful analysis of a more impacting and worrisome kind of partnership. The fact is that by the time OUA was announced, US armed forces had already had a long partnership with Liberia’s military. Military-to-military relationships have become the dominant mode of US engagement with the African continent, and these relationships are overwhelming cast as institutional partnerships. (To wit, ten of the twelve areas of security cooperation are described by AFRICOM on its website as partnerships.)

In the Liberia case, that partnership is especially close. The peace agreement that ended the long running conflict in 2003 called for the dissolution of Liberia’s national army and its complete reconstitution under US supervision. The agreement outlined a plan to make the new Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) a multi-talented force that could not only perform traditional defensive operations against external threats, but could more importantly “respond to natural (and other) disasters, assist in the reconstruction of [Liberia] and support and participate in regional and international peace.” The goal was to produce a “force for good” in Liberia, as a 2015 Michigan National Guard report put it.

To that end, the Michigan Guard (the lead US military agency in the Liberia relationship for the past several years) has sent public affairs officers, lawyers, medical teams and engineers along with its combat trainers. Liberia has participated in a range of multi-nation AFRICOM institution building programs, including (ironically), an initiative launched in 2008 to help African militaries plan their response to pandemic disease outbreaks. As is the case with a number of national militaries in Africa, military-to-military partnerships with US troops were intended to bolster African forces’ capacity to be first responders to a wide variety of future crises, including the effects of climate change, resource shortages, poverty, proliferating criminal gangs and political corruption.

Yet, in Liberia, as elsewhere across the continent, this broad human security approach to partnering across militaries has in practice been subsumed by preparing for the “kinetic” demands of counterinsurgency. In a September 2016 interview with African Defense, Brigadier General Donald C. Bolduc, the head of US Special Operations Command-Africa (SOCAFRICA) made clear that the non-human challenges facing African partners are simply threat multipliers for the most pressing concern: that “violent extremist organizations” (VEOs) will make use of Africa’s chaos to recruit disaffected youth (especially young men). In other words, the broad human security mandate to which African partner forces are supposedly being supported to respond is, in the end, only of concern to the extent that it enables the more pressing problem of fighting a very human enemy.

This is a worldview in which disease, poverty, corruption and natural disasters are problems primarily because they can be exploited by human enemies. And it is a worldview that continues to prioritize war fighting as the ultimate skill set for both US and partner forces. As a consequence, the capacity of the AFL to be a “force for good” in addressing broad human security goals has been structurally undermined. Sean McFate, one of three DynCorp contractors hired to design and implement the first AFL restructuring programs, has described the gutting of civil/military relations classes from the earliest days of the program. Non-combat peacekeeper training, for example (the kind of training that might have helped stabilize, rather than aggravate, an urban crisis like Monrovia’s Ebola outbreak), has been a consistently underfunded and under-developed aspect of military re-structuring.

It is a problem exacerbated by the tendency to focus not on training African forces in their entirety, but on elite commandoes. Special forces and anti-terror units have received advanced training in specialties like urban warfighting and counter-insurgency at the expense of training the bulk of African partners in skills such as non-lethal crowd control or disease tracking.

“By helping Africans help themselves,” said Maj. Albert Conley III of USARAF’s Counter Terrorism bureau, “it means that we don’t have to get involved ourselves. If Africans are solving African problems, then the U.S. government doesn’t have to use the U.S. Army to solve African problems.” What exactly solving African problems means is generally left unstated in that oft-repeated slogan. But the West Point cordon sanitaire may well be its inevitable, logical conclusion. African military partners are regularly promoted as “forces for good” whose writ is to deal with all manner of threats. But if in practice military partnerships are designed primarily to combat the spread of terrorist networks, to keep Africa’s perceived chaos in its place, then urban warfare tactics like the armed cordon will be the only response to every problem – human, environmental, or pathogen.

This series of essays emerges from a project based at the University of Washington that explores “partnership” as a programmatic priority and affective ideal in initiatives between the United States and African countries. We consider the politics of partnership in three different realms of US-Africa relations: military training and disaster relief, reproductive health initiatives and study abroad programs.

July 5, 2017

Against the romance of study abroad

Are study abroad programs best understood as a neocolonial activity? In what ways might a typical neocolonial critique, while accurate, cause us to overlook other possibilities of how study abroad does or could operate?

We both teach at the University of Washington (UW), where we lead study abroad programs to Tanzania, South Africa, and Spain. The idea of global partnership is central to every aspect of study abroad programs as practiced at our university and many others. The university partners with faculty to create programs from the course content to the logistics. Faculty are expected to find local partners to facilitate learning experiences that will transform their students. Once abroad, local partners activate their personal and professional networks, as well as give of their time, to facilitate not only the learning of US-based students, but also their safety and comfort. Local partners are often compensated for lectures and sometimes as coordinators, but at rates that reflect salaries in their countries, therefore at a much lower rate than their US-based partners. Partnership becomes an idea invoked often in theory, yet referring to very different types of transactions in practice.

The term global partnership, whether applied to research, business, education or even activism, implies a kind of equality in agency if not in resources. Thus, the frequent mobilization of the term – particularly in connection to the African continent – seeks to convey that the individuals or institutions involved in those partnerships have moved beyond the inequitable relationships of the past: slavery, colonialism, structural adjustment, Cold War military domination and cultural imperialism. According to the discourses of global partnership, our relationships are no longer ones of exploitation or domination – in short, neocolonialism – but rather ones of reciprocity and mutual benefit.

We call bullshit. Global partnership, as the term is currently used, has become so ubiquitous as to be vacated of meaning. Nearly any kind of agreement or relationship, contractual or informal, is now being described as a partnership, regardless of the degrees of reciprocity involved. We recognize that any formal or informal partnership, or any relationship for that matter, will contain varying degrees of reciprocity or mutual benefit at different times, and rarely is any relationship perfectly reciprocal at any moment, or even over the long term. Yet we hold out the ideal that reciprocity and mutual respect should be at the core of any partnership, and that to achieve these goals, one must keep dynamics of power and privilege at the fore. The discourses of global partnership, however, mask dynamics of power relations in the name of equality. They allow individuals and institutions to reinscribe unequal power relations with so-called partners in Africa while deflecting attention away from claims of reciprocity and histories of accountability.

Let us give an example. In the summer of 2016, we co-led a study abroad program called “Critical Perspectives on Ecotourism in Tanzania.” As part of the program, we hired a tour company to provide transportation throughout our time in rural Northern Tanzania. As a result, students and faculty spent many hours in small vehicles with three guides, who worked as drivers, nature guides and cultural interpreters. As is often the case with travelers of all types, the three guides built significant rapport with our students – sharing food, jokes, stories, and swapping nicknames. They became the closest relationships many of our students had with any Tanzanian individuals. After a day of game driving, the group settled into a hotel in northern Serengeti. Students were shocked and appalled to learn that the guides would not be staying or eating with us, as they had been previously, but instead would lodge in the bare-bones quarters reserved for staff of tour companies.

Why was this so upsetting to our students? Was it upsetting to the guides? Or was it a relief for the guides to spend some time “off the clock” and free from having to interact with our group? Was the lack of luxury in the staff quarters something that bothered the guides as much as the students?

What this experience most profoundly did for our students was disrupted the illusion of an easy, uncomplicated friendship or equality – a true partnership – between them and the guides, and made visible privileges in many forms: of travel, mobility, leisure and comfort. The experience also highlighted the very different approaches to the relationship taken between our students and the guides, wherein the students approached the relationship in a spirit of and desire for friendship, knowledge, and access to an “authentic” Tanzanian experience, whereas the guides approached the relationship as work, as part of their chosen profession and business, and as something in which they took pride but had no illusions of equality or simple reciprocity. In short, this experience reminded the students that the guides were doing a job.

Conceptualizing the guides as “doing a job” provides a very different valence to these relationships than “forming a partnership.” This is not to say that the guides did not enjoy their friendships with our group, or for that matter, that the students (and certainly we as faculty members) did not still see ourselves as doing a job. Our argument is not that these roles or experiences are dichotomous and cannot occur simultaneously. What it does point out, though, is the masking of unequal power relations through the claim of global partnership is not an unintended consequence or an unfortunate side effect of the discourse, but rather its point.-

It is relatively easy to critique our group’s western gaze or the students’ narratives of discovery and redemption. But our students’ concepts of study abroad are individual manifestations of the larger institutional fantasy of the joys and benefits of setting off to study abroad. The fact is that US institutions benefit immensely from partnerships that exploit existing unequal relations of knowledge and power. In this way study abroad programs recast global partnerships as a nostalgic form of exploration (our programs at UW are even called Exploration Seminars). When pushed to use their authority and finances in more reciprocal ways, US institutions often revert to a narrative of transforming their own students to one day change the world for the better in some abstracted future, while at the same time using financing models that rely on student fees to pay for direct student costs, actively precluding broader reciprocity.

We cannot expect that US institutions will embrace a more radical project of reciprocity without pressure. If UW and other institutions of higher education really want to build more equitable global partnerships, we suggest treating our partners as co-faculty with appropriate titles and compensation; supporting reciprocal exchanges and opportunities for students from host countries to participate alongside our US students in their home countries; and finally, situating reciprocal study abroad squarely in university efforts to address diversity and equity. This final step would not only address issues of access for US-based students, but begin to engage with the neocolonial power relations that continue to benefit US institutions of higher education, often at the expense of our “global partners.”

This series of essays emerges from a project based at the University of Washington that explores “partnership” as a programmatic priority and affective ideal in initiatives between the United States and African countries. We consider the politics of partnership in three different realms of US-Africa relations: military training and disaster relief, reproductive health initiatives and study abroad programs.

July 4, 2017

Nationhood and the struggle for Biafra

Biafran activists protest in London outside the British parliament. Image Credit: Alisdare Hickson via Flickr.

Biafran activists protest in London outside the British parliament. Image Credit: Alisdare Hickson via Flickr.Since the arrest of Nnamdi Kanu, the leader of Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), by the operatives of the Nigerian Department of State Security (DSS) in October 2015, public protests have intensified, both in Nigeria and its diaspora, calling for the independence of Biafra. The demands include an appeal to the Nigerian government to conduct a referendum on independence. Kanu has since been released from prison (in April this year), but the protests continue: the goal, after all, is the separation of Biafra from Nigeria.

The demand for Biafra and the clampdown on the agitators by the Nigerian government brings the 1967-1970 Nigeria-Biafra War back to individual and collective memories. On May 30 2017, a stayaway call by Kanu, dubbed “Stay at home”, paralyzed five southeastern states of Nigeria where Igbos predominate. The day marked 50 years since the declaration of independence of the Republic of Biafra by Xolonel Chukwuemeka Ojukwu in 1967. The continuing struggle for the sovereignty of Biafra 50 years after only suggests that nationhood is not a forgotten idea among the Igbos.

Four years after that declaration, Ojukwu fled into exile and a new commander-in-chief, General Philip Effiong, surrendered to Nigerian president, General Yakubu Gowon. By then about three million Biafran lives had been lost in the genocidal war. General Gowon declared his “No victor, No vanquished” slogan and announced a three-point agenda of “Reconciliation, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction.” The objective was to maintain a united Nigeria.

It can be argued that Gowon’s three point plan did little to promote any of the three Rs. Igbo properties in other parts of the country were confiscated or seized in cases of “abandoned properties”; bank accounts of most Igbo men and women who had declared for Biafra during the war were frozen; and as B.J. Audu states, military officers and men from Eastern Nigeria, who, out of no fault of their own, fought on the Biafra side, found their names either removed from the lists of officers of the Nigerian army, air force and navy or were not entitled to either pension or gratuities.

Nevertheless, the Igbo have come out of this sordid experience stronger. Collectively, they have rebuilt their communities and surpassed other groups in Nigeria in at least four areas: technological innovation, international migration, intellectual prowess and economic prosperity.

Before and during the war, Biafrans locally manufactured most of the weapons and other machineries used against Nigerian forces. They refined petroleum crude locally, built roads, airstrips and bunkers, and repaired vehicles. Igbos emerged as the only manufacturers of cars and other electronic products from Nigeria. As far back as the 1980s, it was common for Nigerians to refer to local technology products as “Ibo made.” Igbos are also known among the wider Nigerian population to be adept at commerce and entrepreneurial pursuit. As Ndubisi Nwafor-Ejelinma notes, more than any other Nigerian group, Igbos own businesses and conduct commercial activities in every part of the country and around the globe.

The war caused the displacement of a great number of Igbos from their ancestral homes to many parts of the world. Post war economics in Nigeria have seen this migration trend continue and remittances from expatriate Igbos are used to rebuild Igbo communities, while contributing to the Nigerian economy as a whole. The Igbo well represented in the faculties of many universities around the world. Many Igbo writers engaged the Nigeria-Biafra war in their works, as way of documenting the tragedy for the future generations and to remind the world of the effect of genocidal war on the human psyche.

For two decades, there has been a sustained agitation for secession of the Biafra by a vanguard dominated by Movement for the Actualization for the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) and IPOB. Smaller groups like Eastern Peoples Congress (EPC), Biafra Peoples National Council (BPNC), Biafra Liberation League (BLL) and, recently, the Biafra Independence Movement (BIM), add their voices to the call. Anti-secession groups are also active. Igbo youths against the call for Igbo nationhood have formed the Igbo for Nigeria Movement (INM) under the leadership of Mazi Ifeanyi Igwe. The Njiko Igbo Movement (NIM), founded by Igbo politicians and led by Orji Uzor Kalu, works to secure a Nigerian president of Igbo background.

Still it is probable that an independent Biafra may be realized if the current wave of non-violent protests is sustained. Since neither the MASSOB leader, Ralph Nwazuruike nor Kanu are beneficiaries of political position or financial gain to date, their sustained demand for Biafra nation may be genuine after all.

Nationhood not forgotten in struggle for Biafra

Biafran activists protest in London outside the British parliament. Image Credit: Alisdare Hickson via Flickr.

Biafran activists protest in London outside the British parliament. Image Credit: Alisdare Hickson via Flickr.Since the arrest of Nnamdi Kanu, the leader of Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), by the operatives of the Nigerian Department of State Security (DSS) in October 2015, public protests have intensified, both in Nigeria and its diaspora, calling for the independence of Biafra. The demands include an appeal to the Nigerian government to conduct a referendum on independence. Kanu has since been released from prison (in April this year), but the protests continue: the goal, after all, is the separation of Biafra from Nigeria.

The demand for Biafra and the clampdown on the agitators by the Nigerian government brings the 1967-1970 Nigeria-Biafra War back to individual and collective memories. On May 30 2017, a stayaway call by Kanu, dubbed “Stay at home”, paralyzed five southeastern states of Nigeria where Igbos predominate. The day marked 50 years since the declaration of independence of the Republic of Biafra by Xolonel Chukwuemeka Ojukwu in 1967. The continuing struggle for the sovereignty of Biafra 50 years after only suggests that nationhood is not a forgotten idea among the Igbos.

Four years after that declaration, Ojukwu fled into exile and a new commander-in-chief, General Philip Effiong, surrendered to Nigerian president, General Yakubu Gowon. By then about three million Biafran lives had been lost in the genocidal war. General Gowon declared his “No victor, No vanquished” slogan and announced a three-point agenda of “Reconciliation, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction.” The objective was to maintain a united Nigeria.

It can be argued that Gown’s three point plan did little to promote any of the three Rs. Igbo properties in other parts of the country were confiscated or seized in cases of “abandoned properties”; bank accounts of most Igbo men and women who had declared for Biafra during the war were frozen; and as B.J. Audu states, military officers and men from Eastern Nigeria, who, out of no fault of their own, fought on the Biafra side, found their names either removed from the lists of officers of the Nigerian army, air force and navy or were not entitled to either pension or gratuities.

Nevertheless, the Igbo have come out of this sordid experience stronger. Collectively, they have rebuilt their communities and surpassed other groups in Nigeria in at least four areas: technological innovation, international migration, intellectual prowess and economic prosperity.

Before and during the war, Biafrans locally manufactured most of the weapons and other machineries used against Nigerian forces. They refined petroleum crude locally, built roads, airstrips and bunkers, and repaired vehicles. Igbos emerged as the only manufacturers of cars and other electronic products from Nigeria. As far back as the 1980s, it was common for Nigerians to refer to local technology products as “Ibo made.” Igbos are also known among the wider Nigerian population to be adept at commerce and entrepreneurial pursuit. As Ndubisi Nwafor-Ejelinma notes, more than any other Nigerian group, Igbos own businesses and conduct commercial activities in every part of the country and around the globe.

The war caused the displacement of a great number of Igbos from their ancestral homes to many parts of the world. Post war economics in Nigeria have seen this migration trend continue and remittances from expatriate Igbos are used to rebuild Igbo communities, while contributing to the Nigerian economy as a whole. The Igbo well represented in the faculties of many universities around the world. Many Igbo writers engaged the Nigeria-Biafra war in their works, as way of documenting the tragedy for the future generations and to remind the world of the effect of genocidal war on the human psyche.

For two decades, there has been a sustained agitation for secession of the Biafra by a vanguard dominated by Movement for the Actualization for the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) and IPOB. Smaller groups like Eastern Peoples Congress (EPC), Biafra Peoples National Council (BPNC), Biafra Liberation League (BLL) and, recently, the Biafra Independence Movement (BIM), add their voices to the call. Anti-secession groups are also active. Igbo youths against the call for Igbo nationhood have formed the Igbo for Nigeria Movement (INM) under the leadership of Mazi Ifeanyi Igwe. The Njiko Igbo Movement (NIM), founded by Igbo politicians and led by Orji Uzor Kalu, works to secure a Nigerian president of Igbo extraction.

Still it is probable that an independent Biafra may be realized if the current wave of non-violent protests is sustained. Since neither the MASSOB leader, Ralph Nwazuruike nor Kanu are beneficiaries of political position or financial gain to date, their sustained demand for Biafra nation may be genuine after all.

July 3, 2017

#Fallism as public pedagogy

UWC protests. Image Credit Barry Christianson

UWC protests. Image Credit Barry ChristiansonClenched fists raised above their heads, the cast of The Fall occupy the black, naked stage bathed in light. Their lips are sealed with masking tape; their eyes filled with recalcitrance. Art imitating life, imitating art. Seven University of Cape Town (UCT) graduates relive their experiences as members of the #RhodesMustFall (RMF) movement weaving together powerful narratives of student activists who used Cecil John Rhodes’ statue as a symbolic focal point in their demand for a decolonized education. What The Fall conveys unequivocally, is that the RMF movement had an important pedagogical dimension; it was a moment of learning.

While we tend to associate learning that is often procured at significant cost from a university with innovation and creativity, pedagogical practices have largely remained anachronistic within these ivory towers. Most university classrooms look the same: someone with knowledge stands in front of the class, while students sit in rows of chairs absorbing this knowledge through osmosis. The most creative professors get, is to rearrange the chairs into a circle.

For those of us privileged enough to have purchased a formal education, we recognize the limits of this kind of learning. The corporatization of universities compels professors to spend most of their time publishing papers in peer reviewed journals that only five and a half people will read. There is little incentive to teach; let alone be a good teacher. But here’s the kicker: as recipients of this kind of education who know that sitting in a crowded lecture theatre is largely a waste of time (and money), we continue to believe and invest in this traditional system of learning. Worse still, we dismiss any other form of education that fails to imitate the antiquated classroom model.

While watching The Fall, I learnt more about patriarchy and decolonial thinking than I did during several years of law school. And for those who think that law schools should not engage with questions of patriarchy or decolonial thinking in the first instance, your struggle for wokeness may take a little longer. But for those who recognize that learning can take place in eclectic spaces, I would like to push this idea a little further. Acts of disruption, such as when shit was thrown onto the Rhodes statue by student protestors at UCT, buildings were occupied and art was burnt, constituted moments of learning.

While you may not agree entirely with the disruptive tactics employed by the students, their actions compelled us to think critically about symbols and their meaning; symbols we may have otherwise accepted as incongruous vestiges of our colonial past (and present). And is that not essentially what education is about: teaching us to think critically, to question and challenge?

Adopting the conceptual framework of public pedagogy, the Fallist movement can be reimagined as interlocking moments of knowledge creation that simultaneously challenge the academy’s epistemic deference to Euro-American knowledge. Fallists serve as pedagogues who draw on scholars such as Frantz Fanon, activists like Steve Biko, and concepts such as intersectionality, to weave together a decolonial framework that attempts to make sense of black pain and white violence. Fallism is therefore not only about the destruction of old symbols, but it is also predicated on the creation of new knowledge and ideas that enable the humanization of black bodies.

As darkness slowly envelops the intimate theatre pierced by the defiant glow of a few mobile phones, the audience comprised primarily of young black and white South Africans rise enthusiastically to applaud the sold out performance. The young black woman sitting next to me responds to the student activists’ call for a decolonized education by snapping her fingers approvingly. It’s the final day of The Fall’s second run at the Baxter Theatre in Cape Town, not too far from where the Rhodes statue was eventually removed. The cast emerges from back stage after the show to warm embraces and requests for selfies from audience members.

The Fallists are not uncritical of their movement; they recognize the internal struggles of queer people and women who fought to have their voices heard within RMF. These frictions are symptomatic of unresolved agitations deeply embedded in the genetic constitution of South Africa and its peoples. The rise of Fallism as an epistemological orientation, not only in South Africa, but also on campuses across the world, demands that we rethink our understanding of what constitutes knowledge and how this knowledge is transmitted. It compels us to center black pain and offers spaces for new ways of learning and being.

As Fallism rises, so must we.

July 2, 2017

Sunday Read: Friends in a Ship

Image Credit: Merseyside IT on Flickr.com

Image Credit: Merseyside IT on Flickr.comI. Tesiro

All my mates are married with children. They have made human connections to last a lifetime. They have formed partnerships with people who have chosen to be with them.

They have begun their journeys into mid-life crisis, legacies and death. They know their friends who will lend them money and who may take care of their children in their absence. They have moved into the secondary worries of life while my soul wrestles with primary emotions like love and companionship.

Decades of camouflaging the nature of my heart and erections has robbed me of pleasant opportunities to honestly connect with other souls. Throughout my years of academic learning and societal upbringing, I never had a friend who knew my thoughts, the candid details of my escapades and how I felt about guys. I disguised the identity of my heartbeat and the footsteps of my spirit. Even my shadow was not my own.

It was a lifetime performance of lies and false living. I played the role of a homophobic straight guy while I craved to hold the hands of a guy. I worshipped at the temple of homophobes while I prayed for a man to call my own. I encouraged the affections of women but preferred the hugs of a man. I wasted decades of my life building connections with people who hated my kind, my heart and the things that made me whole. I discriminated against effeminate guys, badmouthed gay love in straight circles and avoided people with homosexual inclinations. I killed every honest emotion in my heart and disavowed everyone with the ability to fall in love with my soul. Because the Bible said so, I agreed to hate myself.

Everything changed when I lost an old friend in 2015. He discovered the duplicity of my character and chose to cut me off. That was when I realised that my friends were acquired based on false pretences. I didn’t give them the choice to evaluate my soul and decide if they liked me for who I was. A friendship based on a misconception is a fraudulent acquisition. Like fake jewelry, it will fail every examination and test of time.

In 2016, I renounced the acquisition of fake friends and fraudulent relationships. I began to build real ships based on truth, trust and total honesty. I began to entrust honest people with the truth about myself. And I have started accumulating friends who love me as I am, men who understand the nature of my affections and have connected with my soul in ways I thought was impossible.

II. Prophet

I met him on the bench where wise-inhalers relaxed beside our neighbourhood canal. His fingers were beautifully crafted, his nails ripe for biting and his hand drawing a splendid sketch of a futuristic African man in a rural setting. His bad boy grin emanated from white teeth in burnt brown gums. I loved his lumps of Nazarene locks and would later enjoy digging my fingers into his bed of virgin-black dreads. I was stunned by his neo-liberal intelligence, non-conformist opinions and free-hearted disposition. I never expected to find someone like him at an impoverished bunk in an under-developed suburb of Lagos.

I was days away from completing my memoir, in need of a neighbourhood confidant who appreciated literature, and chilling by myself in a ship without friends. Our conversations were easy, laughter was plenty and our encounter seemed like a case of artistic serendipity. He was uncommonly generous with his smokes, respectfully considerate of my age and genuinely impressed by my literary hustle. His validation restored my waning confidence in my art and I began to see myself through his doting eyes at a time when my hopes were dependent on the success of some grants and residency applications.

I tested our friendship by reading portions of my memoir to him. That was how he learnt about my sexuality. He was flabbergasted but our friendship continued. I fell in love with his mind and the way he permitted the rights of my soul to co-exist with his heterosexual heart. He was confident in his masculinity and wasn’t threatened by my homosexuality. He listened to my past like a priest and wasn’t disgusted by the nature of my sexual expressions. He accorded me the rights of a fellow human being, the respect of a fellow man and he dignified our fellowship. I felt no shame or embarrassment discussing my same-sex affairs with him. He did not sneer at my sexuality or try to condescend to my emotions. Affairs of my heart were simply affairs of another heart. It was the strangest friendship in my homophobic world. His honesty was very strange.

I’m jealous of his girlfriend and make no attempt to hide my feelings. He doesn’t give a fuck about my jealousy and has probably told her about my existence in his life. Maybe that’s why she calls him every bloody second to speak for hours. At this stage of my life, a good friend is better than the best lover. I do find him sexually attractive and wouldn’t mind exploring his body.

But that’s because I’m a bloody motherfucker. And I think he knows this and that everyone has a friend who wants to fuck them. Hence the creation of the friend zone for safety purposes.

I feel safe with him, in spite of my sexual stirrings for him. He has made me believe that every gay man will find straight friends who understand them, heterosexual men who are not threatened by homosexual love, in a bold new ship where all men are free to express different shades of masculinity, and where everyone has acquired the grace to love gay men with no strings attached.

That is why I call him Prophet. He’s my gift from Ago, the Lagos suburb that robbed my soul.

June 30, 2017

Decolonizing philosophy

Wits University Campus. Image credit: Paul Saad via Flickr.

Wits University Campus. Image credit: Paul Saad via Flickr.Many philosophers consider their field to be the mother of all disciplines. The popular picture is that philosophy, like a fertile womb, gives birth to other sciences and fields of inquiry which then move on with their own methodology and concerns (and they never call their parents!). Naturally, if there is any credence to this methodology, then decolonization of the curriculum or academia needs to start with philosophy.

On the global level, the discipline has been riven with controversy recently. In an open letter to the Journal of Political Philosophy, Yale philosopher Chris Lebron exposed the lack of concern for including issues surrounding Black Lives Matter within the remit of an otherwise all-encompassing publication. The issue was sparked when a (published) symposium was eventually conducted by the journal, with one significant omission, namely there were no black philosophers invited to participate despite relevant expertise.

Across the ocean, a similar occurrence caused ripples within the South African philosophical community when a panel was configured on the topic of “South African Identity” which notably neglected philosophers of color, even those actually working within related areas. Again the outcry, both global and local, was that Black Voices Matter philosophically speaking.

In the wake of the #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall movements, questions of curriculum change became pertinent and stentorian in South African academia. Whether we are questioning the colonial legacy of specific disciplines (see here for economics and here for mathematics, traditionally thought to be held to standards of exigency or abstract reality respectively) or the university as a whole (see here for discussion), the role of philosophy requires special treatment. I think this is the case even if we do not accept the birth-mother story since philosophy is still often associated with critical thinking and engagement with other disciplines.

In fact, transformation in philosophy has been slow and rocky. Most of the departments in South Africa are predominantly represented by a privileged minority (at both the graduate and faculty levels). In response to these concerns, philosophers such as Raphael Winkler, at the University of Johannesburg, argue that a more pressing issue is the phenomenon of “white guilt” and who in society has the right to be an authority on matters of race and/or national identity. There are no doubt interesting philosophical questions here, however, I think such debates are red-herrings to the curriculum issue. The issue of transformation and Africanization of the philosophical curriculum is an issue of structure, content and composition not only personnel.

There are a number of options available to any project aimed at reconstructing the philosophical curriculum in South Africa. As noted in one particularly poignant response to Winkler’s article, the history of South African philosophy is a battle between two western traditions. On the one hand, we have continental philosophy. These are the departments, mostly located at historically Afrikaans universities, often associated with existentialism, psychoanalysis and literary criticism. On the other hand, we have the analytic tradition. These are the departments that follow a tradition closely linked to the birth of mathematical logic and the philosophy of language in the early 20th century in Britain. There is not much communication between these schools of thought. But in either camp, much of the agenda, questions and methodology have already been set by the parent countries in the West.

One path to confronting this situation is the path of inertia. We can just keep on keeping on until acted upon by a rational force of nature. Perhaps alter the personnel with a more representative sample but leave the issues and methodology largely unchecked. There is nothing wrong with the possibility of African philosophy per se, but it needs to show its worth to be considered a serious contender for default status. I think there are two worries with this kind of position. One is that it could unduly deculturalize philosophy. Analytic philosophy, despite often using techniques of investigation such as deductive logic, is not an objective science (continental even less so). It has historical and cultural baggage (like many other disciplines). Its topics are informed by many of these erstwhile positions (would Descartes or Rawls have put so much weight on weightless disembodied individual thinking if they had strong communal ties as expressed in the Southern African concept of Ubuntu?). Another issue with this sort of view is that it assumes African philosophy is a final product. But to me the excitement of the possibility of an African philosophy is precisely located in its inchoate nature.

Another strategy could be the formation of a comparative discipline, such as comparative politics, which examines western and non-western philosophical thought side-by-side. I think that this possibility is promising. But it suffers from feasibility issues, namely that if the philosophers who are teaching this new field are mostly trained in analytic philosophy, there is a strong likelihood that the resulting comparison will reduce African philosophy to a curiosity or an “exotic” side thought. This is a nontrivial worry (but also not insurmountable).

The last option is that we make a genuine attempt to Africanize the curriculum. By this I mean we question the content (kinds of questions we ask), the methodology (how we ask and answer those questions) and our sources (who is saying what and what their positionality is). This would be an exploratory project and might lead us to many points of contact with other traditions, both analytic and continental, and further abroad, Indian and Chinese or even lesser explored traditions. Of course, this path is beset with complexity. Is there any such unified object as “African” thought or philosophy? Need there be (the West may have done quite well without a similar unified object of “Western thought”, see Appiah’s account)?

Perhaps in following a dictum of Edouard Glissant (that “the West is not the West: it is a project not a place”) we can appreciate an African philosophical project not bound by geography or history but not ignorant of them either. These are surely the questions that would engage the brilliant minds of our future scholars and attract the collaboration of others further abroad. Continuing to exclusively exist within the same western intellectual atmosphere seems to me like a much less exciting prospect.

June 29, 2017

Museums, another “sight” for struggle

The exhibition Goede Hoop: South Africa and the Netherlands from 1600 at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (February 17 to May 21) may be over, but it is sure to carry long-lasting effects. The curatorial statement described this exhibition as intending to explore “what took place between 1652, when Jan Van Riebeeck landed at the Cape and Mandela’s visit to Amsterdam in 1990.”

The exhibition Goede Hoop: South Africa and the Netherlands from 1600 at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (February 17 to May 21) may be over, but it is sure to carry long-lasting effects. The curatorial statement described this exhibition as intending to explore “what took place between 1652, when Jan Van Riebeeck landed at the Cape and Mandela’s visit to Amsterdam in 1990.”

Framed by the museum as a critical showing of the “relationship” between South Africa and the Netherlands, the museum’s promo video made it seem that the curatorial team had set out to expose the colonial dirty laundry of the Netherlands and the crimes of their “distant cousins,” the Boers and Afrikaners, some of who are descendants of Dutch colonial settlers.

Goede Hoop preview trailer

My interest in this exhibition is two-fold. First, the Western Cape province, where my family is from, was once a Dutch colony named Kaap De Goede Hoop (Cape of Good Hope), founded in 1652 until1806 when the British took control. The colony’s economic base was built on slavery. In the surnames that form part of my family tree and the language spoken by my parents, Afrikaans, there are traces of this history. Second, I am currently working on a Ph.D. proposal focused on how European museums and curators approach the subjects of colonialism, decolonization and coloniality. As a black South African woman, it is important to me that I also come to terms with the fact that part of this bloody, violent collective history is entangled with my personal history and parts of my identity.

Walking through the exhibition was like making my way through a hall of mirrors: what’s reflected feels familiar but the image has been distorted and obscured. At the entrance to the exhibition is a panel titled “Thanks and Acknowledgements.” Under “Curators” I expected to see some collaboration with South African curators, artists, scholars or researchers, but there are none. Surely an exhibition looking at contemporary South Africa would involve at least one South African curator. Who is telling the story is as important as what story is being told and the omission of South African voices at the onset is deeply problematic. From this point onwards I become conscious that in this exhibition my voice doesn’t matter and that perhaps this exhibition is not for me at all.

The first room is supposed to speak of the Indigenous people of the region of what is now the Western Cape. No mention is made of the hunter-gatherer San societies that were exterminated by the impact of the arrival of the Dutch East India Company founded in 1602 to coordinate the Dutch trade and colonial expeditions to the East Indies. I guess the panoramic landscape representing the land that was to become the Cape of Good Hope colony didn’t speak of Dutch pastoralists’ murderous land-grabbing and ecologically damaging farming practices that ensued.

Another area of focus is the “Genesis of the Afrikaaner or Afrikander,” which doesn’t explain the historic complexity of the terms Afrikander or Afrikaaner, but reinforces narrow understandings of who this group of people are and their history. What complicate this identity and the idea of the Afrikaner as “white” and “European” and troubles notions of racial purity which led to the Apartheid system is that the first people who identified as Afrikanders were African or of both African and European descent. Klaas Afrikaner and his son Jager Afrikaner were members of the Orlang community that formed part of the broader Khoi Khoi society. In the mid-19th century, emancipated slaves, and slaves born in the Cape Colony were known as Afrikaners, whereas the settlers of Dutch descent referred to themselves as “Boere,” “Christene” and “Nederlanders.”

The narrative jumps between periods and centuries and as a result I feel like I must have missed something. Who were the enslaved? How did they get to the Cape? Why are they portrayed as subjects without agency: voiceless, silent and other. This is another missed opportunity to explore how slavery and slave history shaped present-day South Africa and how the psyche of the Western Cape in particular is still deeply rooted in the relations between master and slave.

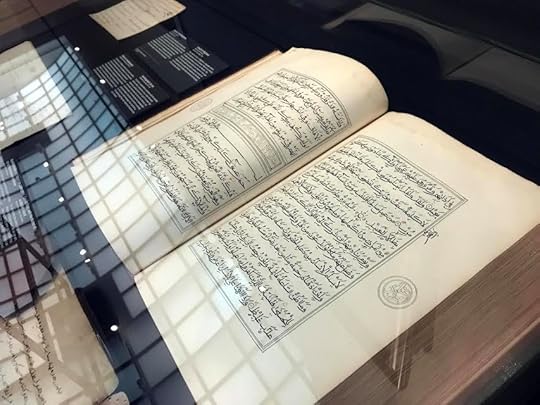

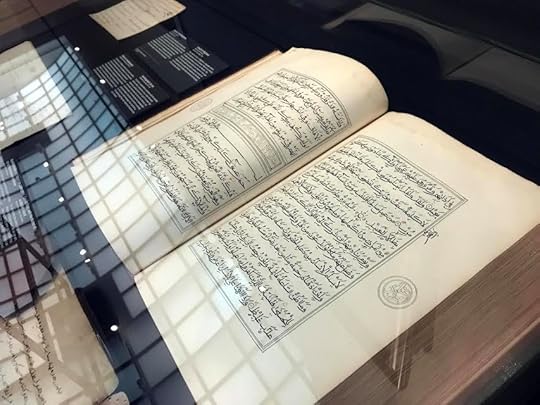

The “Influence of Islam” display reads as an unimpressive footnote, especially since it had such a massive impact on Cape society and connects Cape Town to the Indonesian Archipelago (another Dutch colony). The earliest Afrikaans text was a Qur’an written in Arabic Afrikaans script, and research into the work of the historian Achmat Davids and into his archive would have provided a great deal of material for the exhibition. (For more on this, see an article I co-wrote with Dylan Valley in 2009.)

A few days before I left, the Dutch activist, Marjan Boelsma (she had been involved in the Dutch anti-Apartheid movement) wrote an open letter to the Chair of the Rijksmuseum (posted on Facebook) which critiqued the exhibition as a “missed chance.” The letter was signed by numerous activists, scholars, artists and curators. They charged that the exhibition plays down the Netherlands’ role in colonialism in South Africa, excluded black South African curators, and relied on Eurocentric archival documents, among others.

It didn’t help that a few weeks after the exhibition opened, a former leader of the second largest political party in South Africa, the Democratic Alliance, tweeted her appreciation for colonialism’s supposed positive legacy. Helen Zille, who is white, governs the Western Cape, which has a violent history of slavery and colonialism. Random, often fatal, violence against black South Africans, especially in small farming towns and communities outside of major urban centres, also proves that relatively little has shifted regarding the colonial power relationships amongst the white and black populations of the country.

Others critical of this exhibition have already commented on its problematic use of language, both in the Dutch text and its translation into English. What I found particularly bizarre was the use of the word “hotchpotch” (possibly as a stand-in for the less desirable miscegenation?) which trivializes experiences of violence, erasure and centuries of oppression. Terms like “savage warrior” are also not problematized and unpacked critically.

In another room there is a large display of what can only be described as ethnographic caricatures of South African people by Robert Jacob Gordon. This display is arranged from the perspective of the colonial gaze – colonialists living in Cape Town in the 18th and 19th centuries. This work also gives the impression of the Western Cape region as uninhabited empty land, up for grabs. The label accompanying these caricatures suggests that the Dutch treated slaves badly, but we see no visual evidence of this. And did I miss the significance of Jan Van Riebeeck as a symbolic figure used by the nationalist, Apartheid government? Surely this is important to show because it was fundamental in historicizing Afrikaner nationalism and its claim to a European identity.

The next display, “1806: British Empire Annexes the Cape” fast-forwards to the British Invasion of the Cape. Subsequently, we arrive at the Anglo Boer war. A label describes the Dutch calls to support their “distant cousins”, the Boer. The exhibition then briefly mentions Afrikaner support for Nazi’s during the Second World War and that Dutch Social Nationalists moved to South Africa after the war. At this point, I notice the landscape paintings on display by the artist Jacob Hendrik Pierneef, who was heavily influenced by Afrikaner nationalism and its desire to carve out a unique identity following the Anglo-Boer war, and critiqued for depicting empty landscapes void of indigenous South African homesteads or life outside of that of the Afrikaner.

We are catapulted into the anti-Apartheid movement and struggle, highlighting Dutch support for the end to Apartheid. In this room, Nelson Mandela is deified as the representative of both struggle and freedom and most-importantly, reconciliation. What’s unsaid, is how Apartheid rule (1948-1994) allowed the Netherlands a pass to ignore its colonial past. The exhibition flirts with the attempt to acknowledge that some of the deep-seated socio-economic political issues we are dealing with in South Africa in the present have something to do with the lingering effects of Dutch colonization. But the argument made is rather muddy and instead, the Rijksmuseum presents a simplistic and palatable exhibition for Dutch (and other western audiences).

Although these national European exhibitions on colonialism can be read as an attempt at symbolic reparations to educate their publics on colonialism, the exhibitions themselves often fail to do this by resorting to tropes of indigenous peoples. They reinforce skewed power relations through curatorial practices that erase or omit local voices. For example, no young black artists are included in the “contemporary art” display supposed to represent the future generation of South Africans. Instead here we see the works of photographer Pieter Hugo and painter Marlene Dumas.

This exhibition proves once again that as Africans, we need to take charge of how our history is represented and set the historical record straight.

This is a site of struggle in itself.

Museums–another “sight” for struggle

[image error]

The exhibition Goede Hoop: South Africa and the Netherlands from 1600 at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (February 17 to May 21) may be over, but it is sure to carry long-lasting effects. The curatorial statement described this exhibition as intending to explore “what took place between 1652, when Jan Van Riebeeck landed at the Cape and Mandela’s visit to Amsterdam in 1990.”

Framed by the museum as a critical showing of the “relationship” between South Africa and the Netherlands, the museum’s promo video made it seem that the curatorial team had set out to expose the colonial dirty laundry of the Netherlands and the crimes of their “distant cousins,” the Boers and Afrikaners, some of who are descendants of Dutch colonial settlers.

Goede Hoop preview trailer

My interest in this exhibition is two-fold. First, the Western Cape province, where my family is from, was once a Dutch colony named Kaap De Goede Hoop (Cape of Good Hope), founded in 1652 until1806 when the British took control. The colony’s economic base was built on slavery. In the surnames that form part of my family tree and the language spoken by my parents, Afrikaans, there are traces of this history. Second, I am currently working on a Ph.D. proposal focused on how European museums and curators approach the subjects of colonialism, decolonization and coloniality. As a black South African woman, it is important to me that I also come to terms with the fact that part of this bloody, violent collective history is entangled with my personal history and parts of my identity.

Walking through the exhibition was like making my way through a hall of mirrors: what’s reflected feels familiar but the image has been distorted and obscured. At the entrance to the exhibition is a panel titled “Thanks and Acknowledgements.” Under “Curators” I expected to see some collaboration with South African curators, artists, scholars or researchers, but there are none. Surely an exhibition looking at contemporary South Africa would involve at least one South African curator. Who is telling the story is as important as what story is being told and the omission of South African voices at the onset is deeply problematic. From this point onwards I become conscious that in this exhibition my voice doesn’t matter and that perhaps this exhibition is not for me at all.

The first room is supposed to speak of the Indigenous people of the region of what is now the Western Cape. No mention is made of the hunter-gatherer San societies that were exterminated by the impact of the arrival of the Dutch East India Company founded in 1602 to coordinate the Dutch trade and colonial expeditions to the East Indies. I guess the panoramic landscape representing the land that was to become the Cape of Good Hope colony didn’t speak of Dutch pastoralists’ murderous land-grabbing and ecologically damaging farming practices that ensued.

Another area of focus is the “Genesis of the Afrikaaner or Afrikander,” which doesn’t explain the historic complexity of the terms Afrikander or Afrikaaner, but reinforces narrow understandings of who this group of people are and their history. What complicate this identity and the idea of the Afrikaner as “white” and “European” and troubles notions of racial purity which led to the Apartheid system is that the first people who identified as Afrikanders were African or of both African and European descent. Klaas Afrikaner and his son Jager Afrikaner were members of the Orlang community that formed part of the broader Khoi Khoi society. In the mid-19th century, emancipated slaves, and slaves born in the Cape Colony were known as Afrikaners, whereas the settlers of Dutch descent referred to themselves as “Boere,” “Christene” and “Nederlanders.”

The narrative jumps between periods and centuries and as a result I feel like I must have missed something. Who were the enslaved? How did they get to the Cape? Why are they portrayed as subjects without agency: voiceless, silent and other. This is another missed opportunity to explore how slavery and slave history shaped present-day South Africa and how the psyche of the Western Cape in particular is still deeply rooted in the relations between master and slave.

The “Influence of Islam” display reads as an unimpressive footnote, especially since it had such a massive impact on Cape society and connects Cape Town to the Indonesian Archipelago (another Dutch colony). The earliest Afrikaans text was a Qur’an written in Arabic Afrikaans script, and research into the work of the historian Achmat Davids and into his archive would have provided a great deal of material for the exhibition. (For more on this, see an article I co-wrote with Dylan Valley in 2009.)

A few days before I left, the Dutch activist, Marjan Boelsma (she had been involved in the Dutch anti-Apartheid movement) wrote an open letter to the Chair of the Rijksmuseum (posted on Facebook) which critiqued the exhibition as a “missed chance.” The letter was signed by numerous activists, scholars, artists and curators. They charged that the exhibition plays down the Netherlands’ role in colonialism in South Africa, excluded black South African curators, and relied on Eurocentric archival documents, among others.

It didn’t help that a few weeks after the exhibition opened, a former leader of the second largest political party in South Africa, the Democratic Alliance, tweeted her appreciation for colonialism’s supposed positive legacy. Helen Zille, who is white, governs the Western Cape, which has a violent history of slavery and colonialism. Random, often fatal, violence against black South Africans, especially in small farming towns and communities outside of major urban centres, also proves that relatively little has shifted regarding the colonial power relationships amongst the white and black populations of the country.

Others critical of this exhibition have already commented on its problematic use of language, both in the Dutch text and its translation into English. What I found particularly bizarre was the use of the word “hotchpotch” (possibly as a stand-in for the less desirable miscegenation?) which trivializes experiences of violence, erasure and centuries of oppression. Terms like “savage warrior” are also not problematized and unpacked critically.

In another room there is a large display of what can only be described as ethnographic caricatures of South African people by Robert Jacob Gordon. This display is arranged from the perspective of the colonial gaze – colonialists living in Cape Town in the 18th and 19th centuries. This work also gives the impression of the Western Cape region as uninhabited empty land, up for grabs. The label accompanying these caricatures suggests that the Dutch treated slaves badly, but we see no visual evidence of this. And did I miss the significance of Jan Van Riebeeck as a symbolic figure used by the nationalist, Apartheid government? Surely this is important to show because it was fundamental in historicizing Afrikaner nationalism and its claim to a European identity.

The next display, “1806: British Empire Annexes the Cape” fast-forwards to the British Invasion of the Cape. Subsequently, we arrive at the Anglo Boer war. A label describes the Dutch calls to support their “distant cousins”, the Boer. The exhibition then briefly mentions Afrikaner support for Nazi’s during the Second World War and that Dutch Social Nationalists moved to South Africa after the war. At this point, I notice the landscape paintings on display by the artist Jacob Hendrik Pierneef, who was heavily influenced by Afrikaner nationalism and its desire to carve out a unique identity following the Anglo-Boer war, and critiqued for depicting empty landscapes void of indigenous South African homesteads or life outside of that of the Afrikaner.

We are catapulted into the anti-Apartheid movement and struggle, highlighting Dutch support for the end to Apartheid. In this room, Nelson Mandela is deified as the representative of both struggle and freedom and most-importantly, reconciliation. What’s unsaid, is how Apartheid rule (1948-1994) allowed the Netherlands a pass to ignore its colonial past. The exhibition flirts with the attempt to acknowledge that some of the deep-seated socio-economic political issues we are dealing with in South Africa in the present have something to do with the lingering effects of Dutch colonization. But the argument made is rather muddy and instead, the Rijksmuseum presents a simplistic and palatable exhibition for Dutch (and other western audiences).

Although these national European exhibitions on colonialism can be read as an attempt at symbolic reparations to educate their publics on colonialism, the exhibitions themselves often fail to do this by resorting to tropes of indigenous peoples. They reinforce skewed power relations through curatorial practices that erase or omit local voices. For example, no young black artists are included in the “contemporary art” display supposed to represent the future generation of South Africans. Instead here we see the works of photographer Pieter Hugo and painter Marlene Dumas.

This exhibition proves once again that as Africans, we need to take charge of how our history is represented and set the historical record straight.

This is a site of struggle in itself.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers