Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 278

June 28, 2017

Africans want in on the Virtual Reality game

Still from ‘Let This Be A Warning’ by The Nest Collective

Still from ‘Let This Be A Warning’ by The Nest CollectiveThe human desire to experience another perspective, place or reality has a long history in the visual arts. Recent innovations mean 360° video is now frequently available on social media, with content from news outlets and humanitarian organizations. With the advent of this increasingly accessible technology, the storyteller’s toolkit is suddenly more powerful. The ability to create an immersive experience for the audience changes how narratives are constructed and received. Africans also want in on the game.

Virtual reality (VR) technology provides another a form of storytelling for filmmakers.

Four new VR films were recently showcased at the 19th annual Encounters South African International Documentary Festival. Let This Be A Warning by The Nest Collective, The Other Dakar by Selly Rabe Kane, Nairobi Berries by Ng’endo Mukii, and Spirit Robot by Jonathan Dotse. This was the second year that the festival included a Virtual Encounters Exhibition.

When I watched Let This Be A Warning, I recognized the common technique of using science-fiction to critique society from an alternative view point. The Nest Collective tells an African story through the often white-dominated genre of sci-fi because of its potential for commentary. The premise is around the arrival of a presumably white space traveler landing on a colonized black world and the reaction of that society to this visitor. The filmmakers wonder whether future black worlds will be as welcoming to “westerners” as they were before. The first person point of view, like a video game, makes the audience look through the unwelcome visitor’s eyes. I am curious how different audiences receive this social question. How does this film play to an audience of color versus a white audience? What kinds of conversations about the past and potential future are initiated?

The Other Dakar is a strange journey of magical realism, described as an homage to Senegalese mythology. The creator, Selly Rabe Kane, known worldwide for her fashion designs, uses her talents to build a stunningly beautiful and surreal experience. Otherworldly fashion driving the story reflects Kane’s sensibilities as a designer. This world of Dakar, as explored by a little girl in the film, is full of symbolism with striking colors, and patterns. Although I was somewhat disoriented in the fantastical 360° video, the central message was clear: artists are at the core of Dakar’s cultural soul. Watching this film triggers reflection on the role of artists in cities throughout Africa and beyond.

A poetic dreamscape in Nairobi Berries is a representation of filmmaker N’gendo Mukii’s feelings about living in the city of Nairobi. Two women and a man are seen passing through each lyrical scene. Themes of beauty and darkness, so common in urban life, struggle with each other at every step. N’gendo uses bold colors, animations of butterflies, water, and fire as visual metaphors of her emotions. She taps into the powerful nature of immersive media that cuts through a viewer’s intellectual analysis of an experience. The themes of the beauty and hardness of daily life in Nairobi can be universalized to the common urban reality.

The use of public spaces is a constant battle in every city. The Chale Wote Street Art Festival transforms the streets of Accra, Ghana, into open spaces of dance, music, painting and other art forms. Jonathan Dotse, from Afrocyberpunk, explores the 6th annual Festival in the film Spirit Robot, named after that year’s theme. The event, as explained in the film, was organized to address the lack of infrastructural support for art. The viewers are transported through the streets of Accra to experience several art pieces as they learn about the festival’s story. I was captivated by the art in each scene, particularly when hearing the mural painter mixing his colors and seeing an audience watching an elegant dancer. I enjoyed learning about the festival, but the narration was hard to follow in the VR environment and I wanted to invest more time to fully absorb what was happening around me.

Without the constraints of traditional video, narrative structures must be transformed to effectively communicate to the immersed viewer. New artistic possibilities are boundless for 360° film as the technology becomes more accessible.

June 27, 2017

Behind new Gulf crisis is same old order

Out of nowhere, it seems that a simmering rift between Qatar and the other Gulf States has boiled over into a full crisis. Earlier this month, that rift turned to open conflict for the first time since 2014, as “Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates as well as Egypt and a number of other Arab nations cut ties with Qatar.”

According to Al Jazeera, Saudi Arabia is using its considerable economic clout to pull African countries into the dispute with “huge offers of aid and loans.”

Senegal, Chad, Mauritania, Eritrea, and Niger have recalled their ambassadors to Qatar.

Somali President Mohammed Abdullah Farmajo, reportedly turned down an $80 million offer from the Saudis to join the diplomatic effort to isolate Qatar. The Saudis also “threatened to withdraw financial aid” to the embattled state.

Djibouti has joined the Saudi campaign as well, downgrading its diplomatic relations with Qatar, which has withdrawn its troops from an international peacekeeping mission on the Djibouti-Eritrea border in response.

Relations between Qatar and the other Gulf Cooperation Council countries soured during the early years of the Arab Spring, before the toppling of the first democratically elected President of Egypt, Mohammed Morsi. During this period, the Qatari government was at the apex of its regional power. The previous Emir, Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, had developed a successful strategy for achieving outsized influence for the tiny, gas-rich state, which eschewed the positions of its neighbors to play the mediator for regionally divisive entities, from Iran and Hamas to Israel and the Taliban.

Alongside these diplomatic efforts, the Emir fostered Qatar’s soft power, through the once-mighty Al Jazeera satellite news network, which grew to be the bane of regional autocrats and colonizers. When the region caught fire in 2011, Al Jazeera’s coverage helped bring the revolutions to TV screens across the region. Though embattled despots always claimed that Al Jazeera was simply an instrument of Qatari foreign policy, this was not the case in those days. A more recent shakeup at AJ has many suspecting that the network is under closer supervision of the Emir.

Qatar backed Islamists that came to power in during the Arab Spring, particularly Mohammed Morsi in Egypt, looking to take advantage of the historical events to increase its regional influence. This led to a simmering unease with the other Gulf States, who benefited from the pre-Arab Spring order and backed the old regimes, with the exception of Syria.

Ostensibly, this diplomatic crisis started when a Qatari news outlet was hacked to circulate incendiary statements falsely attributed to Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, who vehemently denied them. Despite the denial, state-owned media agencies in the other Gulf States continued to circulate the statements, leading many to believe that the hacks were part of a premeditated media campaign to justify a diplomatic and economic assault on Qatar.

The timing may seem odd, as Qatar has largely retreated from its more muscular regional policies following the Egyptian coup in 2013. Since then, a poisonous discourse has developed around the Arab Spring, perpetuated by reactionary forces – the UAE and KSA chief among them. These forces oppose any efforts to change the regional order, from which they benefit tremendously, at the expense of the mass of people. The KSA and UAE, like their right-wing allies in the West, maintain that the only way to keep religious extremism and terrorism at bay in the region is through authoritarianism and repression. They seek to portray the events in the wake of the Arab Spring as the investible result of any political opening in the region, any challenge to the stability they impose.

Qatar, which went against the grain and supported the opening, albeit opportunistically and for its own geopolitical gain, has been wrapped into that discourse. The same claims that are animating a full assault on the state were the ones that justified the 2014 diplomatic closures, and the same ones used by opponents of the revolutions in Egypt, Tunisia, Syria and Libya. These opponents seek to portray the revolutions as foreign plots against their governments, whether Qatari, American, or Israeli.

President Trump’s tweets may indicate that his administration green lit the assault on Qatar, and signal his willingness to let the Saudis have their way in the region. It is telling that the accusations against Qatar that have been made by Saudi media outlets are similar to those being made by neoconservatives and the Israeli right; they oppose Qatar’s hosting of Hamas and other groups expelled by regional powers, its more open policy toward Iran, and its role in supporting the Arab Spring uprisings.

Qatar’s regional policy is undoubtedly as grounded in realpolitik as those of its adversaries in the region. It is after all, a small, authoritarian monarchy, not a revolutionary state. The actual goals that animate Qatari policy do not negate the fact that this latest crisis reveals the absurd hypocrisy of the other Gulf States, which couch their positions in the region in the language of “moderation,” whilst partnering with right-wing racists in Israel and the United States, reinforcing the latters’ most detestable beliefs about Muslims and Arabs in order to build support for an anti-Iranian project.

A recent leak of email correspondence between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) ambassador to the US, Yousef al-Otaiba, and influential right-wing players in Washington, including a neoconservative think-tank, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), which takes up positions similar to the Israeli right, demonstrates most irrefutably that the Gulf States, Israel and the Trump administration are ultimately united in their opposition to any challenges to the Middle Eastern political order. This, despite evidence that this order is built upon repression and plunder, benefits US oligarchs, oil titans, weapons contractors and backward autocrats at great expense to the mass of people.

Writing to former Bush Administration officials Stephen Hadley and Joshua Bolten just after Morsi was toppled in Egypt, Al-Otaiba argues that the “Arab Spring has increased extremism at expense of moderation and tolerance,” and that “countries like Jordan and UAE are the ‘last men standing’ in the moderate camp. The arab spring [sic] has increased extremism at the expense of moderation and tolerance.” He goes on to suggest that the US should “empower and protect those forces who preach moderation and tolerance, values that are common with those of the US.” Al-Otaiba argues that the US would be “abandoning the moderates” if it did not support the positions of the UAE and KSA in the region.

The language of “moderation” is similarly used by Zionists, neocons, and the Gulf States to extol the virtue of whichever geriatric despot they currently favor. It serves as a thin veneer of principle to justify support for despotism and theft. Moderation means nothing but favorable geopolitical alignment. The group of countries Al-Otaiba is referring to include the Gulf States, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and Jordan.

A brief skimming of Human Rights Watch (HRW) country reports for these states reveals the true “values” that bind Al-Otaiba’s moderate camp. According to HRW, Jordanian law “criminalizes free speech,” the regime detains journalists and activists under the auspices of wide ranging counter-terrorism laws. It maintains a personal status code that is discriminatory against women, no to mention its unequal treatment of the kingdom’s nearly two million Palestinian residents.

Human Rights Watch reports that the UAE has a long history of banning human rights activists, jailing dissidents, “draconian” counterterrorism laws, legalised discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender. It has just declared that “showing sympathy for Qatar on social media” is a crime punishable by up to 15 years in prison.

The KSA, meanwhile, is one of the most oppressive states on earth.

The Al-Otaiba leaks have also laid bare the extent to which the Gulf States are aligned with Israel in their attempts to crush the last vestiges of the Arab Spring and wage war on Iran. Although this unofficial alliance is far from a secret, the leaks reveal an interesting level of cooperation between the UAE and a neoconservative think tank, the FDD, which lobbies US officials to take on the policy preferences that align with the Israeli right.

The FDD claims to believe “that no one should be denied basic human rights including freedom of religion, speech and assembly; that no one should be discriminated against on the basis of race, color, religion, gender, sexual orientation or national origin; that free and democratic nations have a right to defend themselves and an obligation to defend one another; and that terrorism – unlawful and premeditated violence against civilians to instill fear and coerce governments or societies – is always wrong and should never be condoned.”

I wonder if those ideals pertain to Palestinians. What about the Emiratis Al-Otaiba represents?

Benjamin Netanyahu takes a similar approach in his rhetoric, emphasizing the tacit alliance between Israel and the Gulf States in his efforts to market Israel’s belligerence as anything other than what it actually is. “Major Arab countries are changing their view of Israel … they don’t see Israel anymore as their enemy, but they see Israel as their ally, especially in the battle against militant Islam” he told the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations in February.

Of course, the Gulf States are not waging diplomatic and economic warfare on Qatar to combat extremism at all, they themselves are absolute monarchies claiming to rule through divine right, and using religious justifications to impose a draconian authoritarianism and stomp out challenges to their rule. They have worked diligently to turn the mass uprising of 2011 into a sectarian debacle because, above all, the Gulf States and Israel benefit tremendously from the authoritarian order that has kept the region underdeveloped and unfree for decades.

The latest crisis is surely nothing more than a defense of that order.

June 25, 2017

Weekend Special No.2034

Twitter a while back: ‘Robert Mugabe is old enough to be Muhammadu Buhari’s father.’ Robert Mugabe, 93, is campaigning to be reelected next year. He is “slurring his words and dozing off (just resting his eyes, a spokesman claimed).” He may still win. Wole Soyinka was right in 2011 when he described Mugabe as “still riding it out on his own wall, blotting out the horizon for others with his grossly inflated ego. As for Buhari, he has been in London for nearly 50 (take that in) uninterrupted days on the second of his “medical checkups” this year (the first was a month) and we’re only in June. Word is he suffered a speech impairment. He can’t speak. Meanwhile, Nigeria’s economy is currently mired in a recession. As we said last week, this is about the north wanting to have its turn in the presidency. Nigerians be damned.

Moving on. South Africa’s ruling party, the ANC, is dominating by the Jacob Zuma-faction. He is close to the Guptas. They’ve captured the state and lining their pockets. They also have a media operation: a British PR agency, a TV channel, a newspaper, “opposition” research (basically “fake” news) and “paid twitter.” They are also cynically exploiting South Africa’s class and race inequalities. “White monopoly capital” and “radical economic transformation” are their manifestos. The truth is they want neither of these. Instead, they’ve presided over a period in which black South Africans, the majority, have been subjected to high levels of state violence, broken schools and overcrowded hospitals. In the process, the Zuma-Gupta faction (and their boosters) have discredited left ideas in the public sphere and emboldened liberals and the right. As one economist told me: “Chris Malikane [a New School economic Ph.D. hired as a policy advisor by the Finance Minister] probably did serious damage to left economists wishing to make public interventions in South Africa.” The same goes for the noises they’re making about reforming the central bank (known as the Reserve Bank), as the country’s public protector recently suggested. There are legitimate reasons to debate the role of central banks (see former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’s new memoir). Most South Africans can’t wait for 2019.

About time: South Africa’s “Competition Commission has laid a charge against Rooibos Limited for its alleged abuse of the tea market.”

Did ECOWAS (the 15 member West African economic organization of states) forget about the occupation of Palestine when they welcomed Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to their annual summit? We predicted this.

“Can Africa prosecute international crimes?” A better question would have been: “Have African countries prosecuted international crimes?” Yes, the 2016 prosecution of Hissène Habré. As Sarah Jane Koulen argues, “had the title been a research question, it would have been poorly formulated as it allows for a simply yes or no answer. In addition, it strikes me as indicative of a particular kind of evaluative paternalism that has come to operate within the discursive field of international criminal justice. An audience gathered in Europe to ask of Africa whether it can … Do what exactly? Measure up? Meet the standard? Contained within the question, lies an implicit presumption that the conclusion of the discussion could be ‘no’. This is not provocative. It is cynical and offensive.” Read the rest here.

Obligatory cultural reference: We don’t like to judge movies by their trailers, but why can’t I shake the feeling that the #BlackPanther teaser trailer reminds me of a mix of ‘King Solomon’s Mines’ and ‘Coming to America’? Basically, two sets of mutually reinforcing fantasies about Africa and Africans as backdrop for the morality tale of a comic. Not so fast, says one of my interlocutors: “It has a “lost world” King Solomon’s Mines look except Alan Quartermain is the villain and the natives are the heroes and not impressed and they definitely won’t be mistaking any guys who played hobbits in other movies as gods which is to say it looks great.”

The new Tupac movie, “All Eyez on Me,” is not just bad history and bad facts, it is also just bad.

Speaking of excellent cultural criticism. Zadie Smith on the new film “Get Out,” Dana Schutz and the empty debate (in the phrase of Huffington Post editor of chief Lydia Polgreen) on who owns black pain.

And Michael Ebenazer Kwadjo Omari Owuo, Jr. does it again.

All bullshit claims aside about Lavar Ball turning capitalism on its head (he is basically a mix of a showman, carnival barker–an old American tradition–who gets how US media culture and promotion works), he sounds like a great father.

RIP Prodigy. “I’m only 19, but my mind is old”

HT: Doron Isaacs, Lydia Polgreen, R.L. Stephens, Kenichi Serino, Sam Argyle, Ben Fogel.

June 23, 2017

Weekend Music Break No.110 — Abdullah Ibrahim’s ‘tawhid’

Abdullah Ibrahim Mukashi Trio, Gent Jazz Festival, Gent, BE, 11.07.2015. Image Credit Bruno Bollaert via Flickr.

Abdullah Ibrahim Mukashi Trio, Gent Jazz Festival, Gent, BE, 11.07.2015. Image Credit Bruno Bollaert via Flickr.Cecil McBee’s thumping bassline complimented by the sporadic drums of Roy Brooks creates a melancholic setting for Abdullah Ibrahim’s exultation titled “Ishmael” (recorded 1976), named after the son of the Biblical Hagar and Abraham. While listening, expectations fall irrelevant, mesmerizing the audience. The mind flows with the beat, following the wailing melodic drifts of Ibrahim alternating between saxophone, piano and voice.

In a review of Ibrahim’s recent concert at New York City’s Town Hall, held on South Africa’s Freedom Day, Giovanni Russonello wrote for the New York Times, “There was darkness and suspense, and a sense of broad expanse.”

A shadow underlies many artistic expressions, including human spirituality and religion. In 1962, with Nelson Mandela imprisoned, the Cape Town-born Ibrahim left South Africa for Europe – where he met his mentor, Duke Ellington – and then on to New York to attend Juilliard. After struggling with alcohol and marijuana misuse and “searching for spiritual harmony in an increasingly fractured life,” Ibrahim returned to Cape Town.

“Years of smoking and drinking had battered his body,” writes John Edwin Mason, a professor of African History at University of Virginia. “In New York, doctors and a Native American medicine woman both told him to ‘straighten up.’ And he did, entering a period of ‘cleaning’ and embarking on a spiritual quest that began in New York City and culminated with his conversion to Islam, in Cape Town.”

Speaking about this turning point in his life with the UK Guardian in 2001, Ibrahim said, “I went back to church; I didn’t find it there. I went into all religions – the [Bhagavad] Gita, I-Ching. Then I realized most of the friends I grew up with were Muslim. Cape Town has a rare harmony, intermarriage.” The musician converted to Islam in 1968.

During this period in the 1960s, harmony was sought after in America as well. Many American jazz musicians viewed Islam as part of a decolonization movement, as an escape from their country’s segregation laws.

Before his conversion, Ibrahim was exposed to many musicians involved in the Muslim movement in America. Figures like Sheikh Daoud Faisal, a fellow alumnus of Juilliard, inspired up-and-coming jazz musicians like Ibrahim. Faisal lead a mosque in Brooklyn Heights and was a representative of Morocco at the United Nations. Archie Shepp, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, and Pharoah Sanders, to name a few, were also influenced by Islam, specifically Sufism and the Gnawa music of Morocco.

“Ibrahim was riveted by these artists who were emphasizing links between Black America and Africa and writing anthems of solidarity,” Hisham Aidi, Columbia University lecturer and author of Rebel Music: Race, Empire and the New Muslim Youth Culture (2014) tells me via email. “Black and coloured South Africans living under white minority rule also saw Islam as a way out.”

In Cape Town in 1974 Ibrahim wrote his own anthem of solidarity titled “Mannenberg,” heralded as “the unofficial anthem of South Africa.” For many, Islam was “a way out,” an expansion of the mind, a collaborative fight against oppression. “Mannenberg” is a musical extension of this consciousness.

“[Ibrahim] found the Black Power movement liberating with its expansive definition of blackness that included ‘coloured’ individuals like him,” Aidi says. “The rhetoric and sound of unity appealed to him. Stokely Carmichael was not Muslim, but he had a strongly pro-Muslim discourse, and stressed the unity of Africa from Cairo to Cape Town. Interestingly, to this day, when Ibrahim talks about his Muslim faith he tends to stress the concept of tawhid – meaning the unity or oneness of God.”

While tawhid refers to the unity of God, it also maintains that the rest of the world is many. This paradox of oneness and multiplicity is central to Islam. It is also a major theme in Ibrahim’s music. Musicians perform in aggregate, forming an apparent whole. This dialectical relationship forming a captivating breathe of sound is only possible with someone as talented and devoted as Ibrahim guiding the movement.

“The most beautiful, potent aspect of Islam is the unity of things,” Ibrahim told the Guardian. “You can’t throw anything out of the universe. This realization has been a driving force for me.”

From Cairo to Cape Town to New York the fight against oppression lingers to this day. Ibrahim’s music continues to ring true for millions united as one.

June 22, 2017

Dakar’s African Renaissance

Image Credit: Jonathan E. Shaw via Flickr.

Image Credit: Jonathan E. Shaw via Flickr.I have wanted to come to Dakar since I was a young man growing up in western Kenya reading Léopold Sédar Senghor’s poetry.

My mother, a schoolteacher, made me read Senghor’s poetry aloud before asking me to explain what Senghor was thinking when he wrote his poetry. In my late teenage years, I read Mariama Ba’s “So Long A Letter,” one of the most acclaimed literary books out of Senegal. The powerful images from the book forcefully introduced the world to the life of women in Senegal and the intersection of African traditional culture and Islam. In 2002, as I was becoming a man, at Kenyatta University, my mother and I watched Senegal beat its former colonizer, France, in the World Cup, though it looked more like a contest between Africans in the diaspora against Africans at home; most of the French players are of African descent. My mother was jumping all over the seats with joy. Senegal would later be eliminated in quarter finals.

Dakar airport is like those in any other developing country, with its remnants of colonial structures. The city is beautiful in a way. In an honest sort of way, in a “I am going to charm you and not rob you” kind of way. Nairobi is different. Kampala also. Detroit too. Those places twist people’s arms for the smallest of gifts.

Standing atop the 160 steps of Dakar’s African Renaissance monument, installed by former President Abdoulaye Wade, reminds me of the Gaza strip. Rows of short, square brown unpainted houses. No shine in them, just brown, the color of concrete and sand with the beautiful Atlantic as a backdrop. The people in them and their taxis on the streets are colorful. Like little butterflies on a brown background. Restaurants like the one where I am seated waiting for fresh fish, have been made very popular by Anthony Bourdain’s “Parts Unknown” on CNN. My waiter is wearing Kanye West’s shoe line. The Yeezys. I cannot afford these shoes. The prices of the limited edition are steep in the United States. How can he? In a country that is over 90% Muslim and elected a Christian president, I guess possibilities abound.

Senegal has been a diplomatic and cultural bridge between the Islamic and black African worlds. Some devout non-hijab wearing Muslim women are still be bound by religion. Iif indeed there is equality, why is the woman in the African Renaissance Monument behind the man? Why is she not by his side as a strong family forging forward together? Why is the African woman always left behind yet she carries the burden of the entire family in most instances. In this era, one could argue that the monument is not adequately feminist. But then again there is a child pointing to a new dawn. Tomorrow, I need to find out if the child is indeed pointing to a dawn of a new era or to France as some people say.

Senegal maintains closer economic, political, and cultural ties to France than probably any other former French colony in Africa. West Africa also seems to be led by many children. Cunning African children of the French. Black-skinned Frenchman. Identity crises start at the highest levels of the government.

I want to ask my taxi driver questions but I only go as far as mentioning my hotel. I do not speak French. He only speaks Wolof and a little bit of French. The Sufism practiced here is tempered with the many years of exchange between Islamic and African traditional cultures. It is quite different from the one portrayed as violent and perverse in western media.

As Ba writes: “In Senegal, you are free. You wear what you want. Eat what you want. Do what you want.”

Dakar is safe. I have been told this before. I am walking from Just4U, one of the local dancing spots. Tonight is hip-hop night and a band is made up of youth from Chiekh Anta Diop University. They are belting rap songs in a seamless mix of French and Wolof. The crowd is enjoying every bit of it. I decide to walk to my hotel. A man of my age with a long cylindrical loaf of bread joins me. We exchange pleasantries and I am pleasantly surprised that he speaks a bit of English. My excitement quickly turns to frustration because of our inability to understand each other and communicate freely as Africans. It is disturbing that the only pathway for Africans to understand each other within Africa is to master the language of former colonialists. Is there hope in the unifying power of language; the way Swahili operates in East Africa? Rwanda and Tanzania seem to be doing fine after replacing French and English respectively with Swahili as the main language of instruction in schools.

I am lucky my new friend Mohammed understands some English. His brother works in Dubai as a waiter and has a Kenyan girlfriend. We are immediately connected. Mohammed says, “I walk you like this, me is gud polis.” We smile in the night breeze of the Atlantic. He nudges me on the side, lifts his shirt and shows me a pistol. He realizes my concern and quickly moves to assure me saying, “Here, polis no shoot people.” I am rather disturbed that I am very relaxed in the presence of a stranger with a gun. Normally I am suspicious of cops. In my home country Kenya, years of corruption have blurred the line between a common thief and a police officer. An armed police officer as well as an armed robber have robbed me in Kenya. In the United States where I work, the history of police killings of black people has made me very paranoid of the police. I have learned instinctively to change lanes in traffic whenever there is a police car behind me.

Mohammed pulls out his phone and shows me photos where he is in official paramilitary uniform. I am thinking, how did I come to trust these people so easily? Then it hits me. It is something in the people of Senegal that is so endearing. You can feel it when you arrive at the Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport. It is their good nature. Dignified men and women come out in groups to work out at the gyms set up by the government right on the sandy shores of the Atlantic. People are obsessed with physical fitness and spirituality.

I later visit Goree Island aboard a ferry named “Beer.” It coincides with visits by various school- going teenagers. At the slave house, one of the main attractions at the Island, our guide, Abdou says, “Twenty-five million slaves were sold through this Island. Six million died.” He points at me saying, “Strong men like him, would fetch a lot of money. Thin men, would be fed blood beans to fatten up like cattle to fetch more money.” This is a lot to take in. “And young girls, like this one,” Abdou points out at one of the school girls, “fetched a lot of money because they were virgins. Older women were cheaper.” The schoolchildren are giggling. They are eager to get into the tiny cells that held trouble-making slaves.

When we finally step out of the slave house, we find Amina and a cohort of women waiting for us to go buy their merchandise. Amina’s child has traditional African beads straddling her waist. Amina says that the beads keeps evil spirits away. I tell her I was raised Christian and that my parents would always fight my grandmother when she tried putting similar beads on my nephew’s waist. I am wondering how these people have found a way to blend African spirituality with Islam.

Amina says, “African God, no fight with Islam.”

June 21, 2017

Biafra as focal point for fresh perspectives of Nigeria

Image Credit: Goya Bauwens via Flickr.

Image Credit: Goya Bauwens via Flickr.In the past few months, there has a resurgence of Biafra in Nigeria by a group known as Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB), led by Nnamdi Kanu. Interestingly, the new agitation began in the diaspora, in the United Kingdom where Kanu is a citizen, through Radio Biafra. Using easily accessible social media platforms and broadcast technology, IPOB was able to reach thousands of Igbos and non-Igbos across Nigeria and the world. IPOB has been variously described as a breakaway faction of another pro-Igbo group, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra or MASSOB.

Kanu is now in Nigeria, where he was briefly imprisoned by the Nigerian state for a year and a half. The government charged him with treason; in some of his speeches he told supporters, “We need guns and we need bullets.” The trial is ongoing.

Since the truncation of the march to a democratic Nigeria in 1993 by the military junta of General Ibrahim Babangida, there continues to be a resurgence of ethnic agitations for self-determination and in the case of IPOB, secession from Nigeria. The reason for such resurgence is often dominated by cries of marginalization and in some cases domination of power. The aggrieved point to the fact that the presidency of Nigeria has been dominated by the Hausa/Fulanis, an ethnic group mainly in the north. The election in 2015 of Muhammad Buhari, considered a member of the northern elite, further heightened the agitation for self-determination or secession by various groups from the south, IPOB in the southeast and Niger Delta Avengers in the south-south. More importantly, control of Nigeria’s oil resources in the Niger Delta often get inserted into the agitation for self-determination or secession either by groups within the Niger Delta or those outside of the region.

Narratives of belonging most times dominate this form of insertion and who can claim membership in whatever country emerges from the rubbles of Nigeria. For example, in the map circulated on the Internet, the entire Niger Delta region is incorporated into Biafra by IPOB and the response of different groups in the Niger Delta had been to dissociate itself from such a map while also lending support to the IPOB agitation as a legitimate struggle against Nigeria. The insertion of Niger Delta by IPOB in the proposed Biafra Republic is understandable considering the fact that the Niger Delta produces the wealth that Nigeria relies on in running its mono-economy—an economy heavily dependent on oil extraction. The Niger Delta was also central to the prosecution of the civil war, also known as Nigeria-Biafra war, between 1967 and 1970, the period when oil extraction started taking a deep root in the socio-economic and political life of Nigeria.

However, what is missing in the conversation around the resurgence of Biafra currently is how the structure of the economy creates spaces of violence and oppression of the majority of the Nigerian population. It is the structure of the capitalist economy that puts the commonwealth of Nigerians in the hands of a few elite. The elite beneficiaries of the Nigerian commonwealth cut across all ethnic groups because capitalist exploitation defies ethnic colouration. Therefore, the many years of marginalization and disfranchisement of the greater majority of the Nigerian populace from the structure of the economy shapes today’s agitation for self-determination and secession. The elite class have been in power since independence and continue to recycle themselves while sometimes tokenistically co-opting a few into their fold. The dominance of a rampaging neoliberal economic and political practice, and the absence of a coherent and coordinated opposition in Nigeria further compounds the problem for the Nigerian populace. The absence of a sound and strategic opposition to a structurally deficient economic system that could shape the discourse of power and resources further creates a space where those economically and politically disenfranchised look for creative ways of survival. Thus, agitation for secession and self-determination is symptomatic of a system that remains ineffective in addressing the problems of the people of Nigeria.

In the two decades preceding the advent of the current pseudo-democratic system, particularly the 1980s and 1990s, the Nigerian left was the formidable intellectual and political opposition to elite greed and capitalist exploitation. The many organizations formed by the broad Nigerian left were able to generate a particular discourse that put social inequality and elite mismanagement of the nation’s human and material resources at the core of the problems within the Nigerian state. The rise of neoliberal economic and political practices and its resultant effect on left politics has seen the rise of NGOism, which represents a particular space that fails to account for why and how people are socially and politically disenfranchised.

The ascendancy of ethnic agitation cannot be disconnected from how neoliberal economic and political practices of the last three decades have continuously taken away the wealth of the people and concentrated it in the hands of the few. The rich are getting richer in Nigeria while the poor are left to fend for themselves. The irony of it all is that when a few elite lose power at the centre, the poor become the pawns that are used to whip up ethnic and religious sentiment.

Not surprising, then, that Atiku Abubakar, the former vice president, is clamoring for the restructuring of the federation. At the same time, it should worry us that Ohaneze Ndigbo, an elite Igbo organization, whose members have always collaborated with other elites to decimate Nigeria’s commonwealth are today throwing their support behind IPOB. To those who are familiar with the different epochs of struggle in Nigeria, this is no surprise.

In the 1990s, various left organizations converged to form the Campaign for Democracy and the Democratic Alternative as platforms within which power could be wrestled from the elite. The latter responded by forming its own National Democratic Coalition, NADECO, and when democracy was finally won, NADECO members took credit for it and positioned themselves as the leaders of the new republic. The struggle for a truly democratic Nigeria was lost at that point and the outcome is what we are witnessing today.

To be clear, IPOB, NDA and other ethnic organizations have the right to self-determine whether they want to be part of Nigeria or form their own independent republic. However, it is important to ask questions that could help us engage in a healthy conversation as we mark the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Nigeria-Biafra war.

Biafra as the focal point for fresh perspectives of Nigeria

Image Credit: Goya Bauwens via Flickr.

Image Credit: Goya Bauwens via Flickr.In the past few months, there has a resurgence of Biafra in Nigeria by a group known as Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB), led by Nnamdi Kanu. Interestingly, the new agitation began in the diaspora, in the United Kingdom where Kanu is a citizen, through Radio Biafra. Using easily accessible social media platforms and broadcast technology, IPOB was able to reach thousands of Igbos and non-Igbos across Nigeria and the world. IPOB has been variously described as a breakaway faction of another pro-Igbo group, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra or MASSOB.

Kanu is now in Nigeria, where he was briefly imprisoned by the Nigerian state for a year and a half. The government charged him with treason; in some of his speeches he told supporters, “We need guns and we need bullets.” The trial is ongoing.

Since the truncation of the march to a democratic Nigeria in 1993 by the military junta of General Ibrahim Babangida, there continues to be a resurgence of ethnic agitations for self-determination and in the case of IPOB, secession from Nigeria. The reason for such resurgence is often dominated by cries of marginalization and in some cases domination of power. The aggrieved point to the fact that the presidency of Nigeria has been dominated by the Hausa/Fulanis, an ethnic group mainly in the north. The election in 2015 of Muhammad Buhari, considered a member of the northern elite, further heightened the agitation for self-determination or secession by various groups from the south, IPOB in the southeast and Niger Delta Avengers in the south-south. More importantly, control of Nigeria’s oil resources in the Niger Delta often get inserted into the agitation for self-determination or secession either by groups within the Niger Delta or those outside of the region.

Narratives of belonging most times dominate this form of insertion and who can claim membership in whatever country emerges from the rubbles of Nigeria. For example, in the map circulated on the Internet, the entire Niger Delta region is incorporated into Biafra by IPOB and the response of different groups in the Niger Delta had been to dissociate itself from such a map while also lending support to the IPOB agitation as a legitimate struggle against Nigeria. The insertion of Niger Delta by IPOB in the proposed Biafra Republic is understandable considering the fact that the Niger Delta produces the wealth that Nigeria relies on in running its mono-economy—an economy heavily dependent on oil extraction. The Niger Delta was also central to the prosecution of the civil war, also known as Nigeria-Biafra war, between 1967 and 1970, the period when oil extraction started taking a deep root in the socio-economic and political life of Nigeria.

However, what is missing in the conversation around the resurgence of Biafra currently is how the structure of the economy creates spaces of violence and oppression of the majority of the Nigerian population. It is the structure of the capitalist economy that puts the commonwealth of Nigerians in the hands of a few elite. The elite beneficiaries of the Nigerian commonwealth cut across all ethnic groups because capitalist exploitation defies ethnic colouration. Therefore, the many years of marginalization and disfranchisement of the greater majority of the Nigerian populace from the structure of the economy shapes today’s agitation for self-determination and secession. The elite class have been in power since independence and continue to recycle themselves while sometimes tokenistically co-opting a few into their fold. The dominance of a rampaging neoliberal economic and political practice, and the absence of a coherent and coordinated opposition in Nigeria further compounds the problem for the Nigerian populace. The absence of a sound and strategic opposition to a structurally deficient economic system that could shape the discourse of power and resources further creates a space where those economically and politically disenfranchised look for creative ways of survival. Thus, agitation for secession and self-determination is symptomatic of a system that remains ineffective in addressing the problems of the people of Nigeria.

In the two decades preceding the advent of the current pseudo-democratic system, particularly the 1980s and 1990s, the Nigerian left was the formidable intellectual and political opposition to elite greed and capitalist exploitation. The many organizations formed by the broad Nigerian left were able to generate a particular discourse that put social inequality and elite mismanagement of the nation’s human and material resources at the core of the problems within the Nigerian state. The rise of neoliberal economic and political practices and its resultant effect on left politics has seen the rise of NGOism, which represents a particular space that fails to account for why and how people are socially and politically disenfranchised.

The ascendancy of ethnic agitation cannot be disconnected from how neoliberal economic and political practices of the last three decades have continuously taken away the wealth of the people and concentrated it in the hands of the few. The rich are getting richer in Nigeria while the poor are left to fend for themselves. The irony of it all is that when a few elite lose power at the centre, the poor become the pawns that are used to whip up ethnic and religious sentiment.

Not surprising, then, that Atiku Abubakar, the former vice president, is clamoring for the restructuring of the federation. At the same time, it should worry us that Ohaneze Ndigbo, an elite Igbo organization, whose members have always collaborated with other elites to decimate Nigeria’s commonwealth are today throwing their support behind IPOB. To those who are familiar with the different epochs of struggle in Nigeria, this is no surprise.

In the 1990s, various left organizations converged to form the Campaign for Democracy and the Democratic Alternative as platforms within which power could be wrestled from the elite. The latter responded by forming its own National Democratic Coalition, NADECO, and when democracy was finally won, NADECO members took credit for it and positioned themselves as the leaders of the new republic. The struggle for a truly democratic Nigeria was lost at that point and the outcome is what we are witnessing today.

To be clear, IPOB, NDA and other ethnic organizations have the right to self-determine whether they want to be part of Nigeria or form their own independent republic. However, it is important to ask questions that could help us engage in a healthy conversation as we mark the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Nigeria-Biafra war.

June 20, 2017

James Baldwin on film

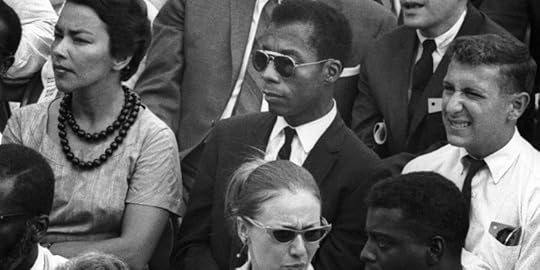

Still from ‘I Am Not Your Negro’

Still from ‘I Am Not Your Negro’Since 1949, James Baldwin has been singing a song. It’s an old tune, at times tender, chiding, insistent, blaring, but always loving. It is, at its core, a bluesy refrain to the country that formed him, tormented him, his contemporaries, and his kin, and ultimately drove him from its shores.

We should be careful, however, not to assign to the author, playwright, and poet, who detested categories so ferociously, the hollow moniker of expat. The long tension between the person, James Baldwin, and the appellation often applied to his famous personage, provides much of the drama in Terrence Dixon’s and Jack Hazan’s rare film document, Meeting the Man: James Baldwin’s in Paris (1971). Shot twenty-two years after Baldwin first left New York with forty dollars in his pocket for the cold, exacting streets of post-war Paris, Meeting the Man stages for the viewer the stunning misapprehension of the man and the “Negro” celebrity as we find an elegantly turned-out Baldwin in an early scene in front of the Place de la Bastille intensely dragging on a cigarette, his darting and ever-alert eyes scanning Dixon for the import of this cinematic encounter.

As they work out on celluloid the terms of this profile piece, Baldwin clarifies for Dixon his acute disinterest in presenting for a Western audience what he snarlingly refers to as “James Baldwin’s Paris,” reminding him that he could be Bobby Seale or Angela Davis. Dixon dismisses the life and death context of 1970s America to which Baldwin alludes and refuses the comparison given the author’s notoriety. He presses an increasingly agitated Baldwin who then pointedly declares that he is not “some exotic survivor.” Baldwin’s explicit identification with Davis and Seale (both of whom had been charged with crimes in the serious climate of the black power struggles of the time) is but one example of that dirge Baldwin had been singing all his writing life. In front of that monument to the revolutionary impulses of 18th-century French citizens determined to rend freedom and equality from the hands of the dominant and the ruling, James Baldwin’s voice slows down as he queries the hypocrisy between the criminalized struggle for liberation by black revolutionaries in the U.S., and the celebration of égalité and fraternité in Europe.

Ten years later and only a few years before his death, we discover the author at the very beginning of I Heard it through the Grapevine (1982), his cinematic collaboration with Dick Fontaine and Pat Hartley chronicling his return to cities of civil rights struggle in the American South, writing rather pensively at a desk as his boomingly weary voice provides the opening narration: “Medgar, Malcolm, Martin, dead…But what about those unknown, invisible people who did not die, but whose lives were smashed on Freedom Road. And what does this say about the morality of this country or the morality of this age?” The knowing flourish of Baldwin’s lament concerning the material and psychic state of “those unknown, invisible people” in the aftermath of one of the most organized and sustained movements for social transformation this nation has ever witnessed, challenges the viewer to consider the twenty-first century legacy of a struggle the author would later famously characterize as “America’s latest slave rebellion.”

In this film, Baldwin presages and enacts this necessary consideration as he recounts his return to Atlanta, Georgia, to his brother, David, who wonders “what Martin would have thought of his Atlanta now?” He is contemptuous of the highways, freeways, and buildings all bearing Dr. King’s name less than twenty years after his assassination and reads these inscriptions as part of the “extraordinary make-up job” on which the nation has embarked:

And there is the [Martin Luther King, Jr.] monument, which is, and this is a difficult thing to say, but I will say it, absolutely as irrelevant as the Lincoln Memorial. It is one of the ways the Western world has learned, or thinks it’s learned, to outwit history, to outwit time—to make a life and a death irrelevant, to make that passion irrelevant, to make it unusable for you and for our children. And we’re confronting that!

Baldwin engages in a kind of cinematic fieldwork as he returns to reconnect with the civil rights activists with whom he labored in Selma, Birmingham, New Orleans, Florida, Atlanta, Washington, D.C. and, with Amiri Baraka in Newark. Grapevine marks his return to the South after he interrupted his European sojourn to travel to Charlotte, North Carolina in 1957 after seeing an image of Dorothy Counts desegregating a school a year earlier.

This scene of Dorothy Counts facing vulgar, raging white mobs stands out for me in Raoul Peck’s new documentary, I Am Not Your Negro (2016). There is something ancient and haunting in Samuel Jackson’s intonation of Baldwin’s voice as taken from I Remember This House, the author’s thirty-page unfinished manuscript about the lives and assassinations of Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin. Relying on the manuscript, and carefully selected archival videos and images, Peck weaves together a chilling narrative of the history and present of black people in this country. From television interviews, clips from Hollywood’s still jarring racial history, to more recent scenes of the militarized responses to protests of police violence in Ferguson, Baltimore, and elsewhere, Peck makes chilling connections between America’s now and then.

I remain compelled by the treatment of Counts in Peck’s new documentary not only because of the grace and impossible courage required of a girl so young, but because of what it confirms about this young experiment called America. Those mobs of angry white citizens represented the country. We can dismiss the national obscenity of grown men and women jeering and spitting at a dignified, young black girl attempting to seek a quality education as the actions of ignorant southerners, but we would be mistaken. If the “story of the Negro in America is the story of America” as Baldwin maintained, what do we do with his statement which provides the charged, if historically understated title of the film? Well, James Baldwin’s devastating 1963 tour of San Francisco, filmed and released by KQED as “Take This Hammer,” which documents the struggle to shield black children in the city from the almost universal message of dispossession and despair that engulfed communities already under siege by the forces of gentrification and urban renewal, might provide an answer. Another important record of Baldwin on film, a particular scene in Hammer is singular in its emotional and metaphysical clarity: Baldwin, seated, dressed in white, a kerchief tied carefully around his neck, considers the existential roots “of something in this country called the nigger.” He continues that he had to know early in life that what was being described had nothing to do with him. He knew, he insists, despite all that had been done to him, that “what you were describing was not me.” If it is true, as Baldwin began, that “what you say about me reveals you,” and since “you” had invented this figure and felt the need to invest black people with all those sedimented associations then, Baldwin argues, you are in fact the nigger.

As the latest entry of the brilliance of James Baldwin on film, I Am Not Your Negro (along with Baldwin’s scathing account of American film-making, The Devil Finds Work) lays bare the rhetorical and imagistic sleight of hand that enables the fiction and terror of race in American life to persist with such a renewed and deadly power. As he suggests, the extent to which we truly wrestle with our psychic need for the myth of the “nigger,” will determine the future of the country. It is still the only song left to sing.

* This was first published on Brooklyn Rail. It is kindly reproduced here with the permission of the editors.

June 19, 2017

The right to ‘eat’

Politics in many parts of Africa is often understood through a metaphor of eating – a point to which Jean-François Bayart drew our attention in his seminal 1989 publication, The State in Africa. In contrast to the social scientific discourse of corruption, the idiom of eating is more neutral and bespeaks necessity. While eating to excess while others go hungry may be corrupt and immoral, everyone must eat to survive. This moral ambivalence is often lost on social scientific thinkers and journalists, who tend to portray “corruption” on the continent (even of the petty or distributive variety) in black-and-white, moralistic terms. Although corruption is a common source of public outrage and complaint, many Kenyans debate the issue in shades of gray, recognizing the sometimes-blurry line between graft and redistribution.

The relationship between politics and consumption is far from abstract. The run-up to the 2017 general elections in Kenya, which has coincided with the rising cost of staple foods, has literalized the “politics of the belly.” This year, inflation reached a four-year high as prices for basic commodities (including cabbage, milk, and sugar) rose precipitously. Kenyans have been particularly hard-hit by the mounting cost of maize flour, used to make Kenya’s most popular (and populist) dish: ugali. In response to spiraling prices, the government waived tariffs for imported maize and, in mid-May, introduced a subsidy on maize flour. These efforts, however, have barely eased consumer suffering.

Ugali politics has since dominated Kenya’s headlines. The opposition and ruling coalitions have blamed one another for the rising prices and flour shortages, trading accusations of negligence and malfeasance. Irregularities surrounding a recent maize import have become fodder for speculations circulating on Twitter and other social media. The Jubilee government has been accused of manufacturing the maize crisis to benefit politically connected commodity traders and using an aptly timed subsidy to win over the electorate. (In typical sardonic fashion, Gado captured these allegations in a series of recent political cartoons). Others charge NASA politicians with politicizing the issue, fueling protests (under the hashtag #ungaRevolution) and obscuring their own responsibility for the maize shortage. While the ruling coalition undoubtedly holds the greatest share of blame for the crisis, it is worth noting that both William Ruto, the sitting deputy president, and Raila Odinga, the opposition’s presidential candidate, have been accused in the past of profiting from the illegal manipulation of the maize market.

Some observers believe that the rising cost of food may fundamentally alter long-standing voting patterns. According to these forecasts, the food crisis will prompt Kenyans to vote on “economic issues,” rather than along “tribal lines,” in the upcoming election. Such arguments rest on a false assumption that material factors are distinct from “ethnic” politics. Economic considerations often drive people’s voting decisions, whether they cast a ballot for a politician of their ethnicity or for a member of another group. For many Kenyans, having one’s “own” in power ensures that a limited amount of wealth (whether through licit or illicit channels) will flow down to ordinary people through social relations of kinship and clientage. These lines of patronage can be essential to people’s survival and should not be readily dismissed as “holdovers” from the past or evidence of “stunted” development. Practically speaking, the reigning alternative (the neoliberal/good governance “consensus”) offers little guarantee of a greater share of the pie.

The food crisis also reveals the need to situate Kenyan politics within a broader understanding of the regional and world economy. The rising costs of food is the result of a confluence of internal and external factors: recent drought in the region, inflationary pressure caused by a strengthened US dollar and rebounding oil prices, dependence on rain-fed agriculture, and profiteering by millers, middlemen, and politicians. It reveals a citizenry prone to elite mismanagement and corruption, susceptible to shocks in the world economy, and increasingly vulnerable to the vagaries of climate change.

The right to “eat” (whether literal or metaphorical) is foundational to the moral economy of politics in Kenya. Certainly, the “politics of the belly” can (and often does) foster elite accumulation, a problem that has reached new heights in recent years. It can also breed divisive forms of nativism, especially during election seasons (a problem encapsulated in the Kenyan expression: “It’s our turn to eat.”*) But there is also subversive potential to the metaphor of “eating,” which can enable citizens to highlight inequality, make claims on the redistributive functions of the state, and publically shame gluttonous and corrupt politicians.

* This expression serves as the title of Michela Wrong’s popular book on John Githongo, the former Kenyan journalist who exposed a particularly egregious case of government graft known as the Anglo-Leasing scandal.

June 18, 2017

Weekend Special, No.1976

This was the week of June 16th–the commemoration of the 1976 Soweto Uprising, which gave impetus to the long last phase of the struggle against Apartheid in South Africa. (If you’re wondering about the contemporary incarnations of that revolt, look no further than #FeesMustFall, #RhodesMustFall, the Economic Freedom Fighters and groups like Equal Education and Reclaim the City.)

Speaking of youth politics: Friday was also the birthday of the late poet Tupac Shakur (1971-1996). He would have been quite middle aged had he been alive: 46 years old. As I wrote in 2011, “… his intensity did not just appeal to just young people here in the United States, but also on the continent.”

And this time last week in 1980, Walter Rodney (Google: “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa“) was assassinated by a pro-American black nationalist regime. As the poet Linton Kwesi Johnson said about Rodney’s crime: “… all that him did wan’ was fi set him people free.”

Speaking of pro-American regimes: We posted on Paul Kagame. That brought out the trolls on Twitter.

Meanwhile, “fewer African students are coming to universities in South Africa due to xenophobia fears and long visa delays – and it could be affecting the future rating of [the country’s] universities …”

From a friend in Britain about the Grenfell Tower fire in Central London that killed (by last count) 58 people; another 54 are presumed missing (and thus dead); mostly working class people, including a large number of African immigrants: “I have never seen such class anger on my TV since the Miners’ Strike in 1984.” As Linton Kwesi Johnson said (yes, him again): Inglun is a bitch. But as my friend continued: “The sympathy for the victims are cross class but its a class issue. Jeremy Corbyn’s sensational electoral result has given working class people confidence–it’s so obvious.”

On Corbyn’s victory, I wrote an article for a South African newspaper, The Mail & Guardian, on what it all means beyond Britain, especially for Africans starved of political alternatives (it’s behind a paywall). Here’s an excerpt:

In contrast to the excitement around Corbyn, politics on the continent is largely stale, dominated by national liberation movements or legacy political parties (including communist, socialist or labour parties) that are long discredited, either rigging elections, suppressing voters, using violent tactics to silence critics, and in cases, where there are free and fair elections, to organize politics via patronage and influence trading (Nigeria), presenting voters with political parties that are ideologically indistinct (Kenya, Ghana) or taking voters for granted by assuming past achievements make them immune to losing office (the South African ANC). In most cases, the alternatives are clean-cut, personality-driven politics combining austerity with market reform.

… Corbyn’s draw, as the left American writer Bhaskar Sunkara wrote in Jacobin Magazine, was that he stood up for socialist ideas beyond simplistic populism and argued for them in public, despite ridicule from media and political-economic elites: “Labour’s surge confirms what the Left has long argued: people like an honest defense of public goods.”

In South Africa, for example, the ANC’s empty rhetoric of “radical economic transformation” combined with a vacuous Afropolitanism is looking more and more like a cover for looting the state. But South Africa also points to the most exciting possibilities for a new kind of politics. Perhaps the most profound takeaway for Africans from Corbyn and Labour’s showing last week is that after years of lip service to left programs, we now have evidence that a real commitment to such programs can mobilize previously apathetic or excluded constituencies. This is something that a combination of South African movements such as #FeesMustFall, left populist movements like the EFF, trade unions (the ones who broke away from Cosatu), the planned Workers’ Party and social movements like Reclaim the City, could rally around together for 2019.

Remember this description of Mobutu Sese Seko? “The all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, goes from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake.” It’s been updated.

BTW, this whole ‘debate’ about cultural appropriation is so much time wasting. Both ‘sides.’ Exhibit 1,000,0001.

This is a good policy: to put condoms in South African schools.

If you’re a South African football fan, this is big news: “Finally, South Africa has beaten Nigeria in an official competitive match.” But not everyone got the menu, like this South African football writer who can’t distinguish between the weight of that competitive fixture and a friendly match. I give up.

Is there anyone who , is suddenly serious about renaming South Africa? The curator and arts activist Valmont Layne has seen this playbook before: “The pattern seems to be 1. take a legitimate and emotive issue in the body politic (eg. economic transformation). 2. Save for an opportune moment to seed a controversy around it (eg. to reduce the heat from #Guptaleaks). 3. Plunder while the debate rages. 4. Repeat.”

Since he won’t shamelessly self promote: Boima Tucker, our managing editor, made an album with his group, Kondi Band. Read it about here, here and here. It also comes with a music video of Boima wondering through Hong Kong:

What will we do without Snoop Dogg. We’ll even forgive him the “Coming to America” themed birthday parties:

Finally, NPR ran an article about the popularity of Latin American telenovelas in Africa; about how it reflects aspirational culture on the continent; “… the Latin American telenovelas work in Africa because they feel authentic.” Not so fast, according to a Brazilian friend of mine, the novelist Marilene Felinto (in an email): “Brazilian telenovelas are export products of Rede Globo Television, not only for Portuguese-speaking Africa, but also for Portugal, China, among other countries around the world. Rede Globo is the largest Latin American media conglomerate. Globo’s telenovelas are experts in creating propaganda mechanisms that perpetuate, in the unconscious of Brazilian poor and middle classes, compliance with social exclusion and class discrimination. The telenovelas, which have high technical quality, are, ironically, another reason for the embarrassment of being Brazilian–not to mention what constrains us today: an illegitimate government, a coup d’état, retreat in social policies … also promoted and supported by Rede Globo and other media conglomerates.”

HT’s and shoutouts: Valmont Layne, Anakwa Dwamena, Marilene Felinto, Peter Dwyer, Abraham Zere and Dylan Valley.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers