Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 276

July 19, 2017

What’s missing from feminist readings of Nollywood romantic comedy ‘Isoken’

Still from ‘Isoken’

Still from ‘Isoken’You are bound to be inundated by all manner of readings of Isoken, Jadesola Osiberu’s new Nollywood rom-com, the majority of them feminist. Those readings will recapitulate society’s pressure on single women. They will critique the near-universal acceptance in Africa of marriage as the crowning achievement of a woman. They will point out subtle and blatant patriarchies. They might miss the inexplicable, self-inflicted assumption of an image based on what a gaggle of women approximates to be a man’s desire. (Some extra-feminist readings will rightly concentrate on the interpretation of the contrast between Osaze and Kevin’s cultural relationships with Africa.) These (feminist) readings will be vital of course, but here’s something outside the sometimes cloying box.

In 1962, J.P. Clark, then a journalist, was tapped to Princeton University’s year-long Parvin Program, one of those weapons of elite instruction deployed in and on Africa to counteract Soviet ideological influence. Things didn’t go as planned. Clark would prove a difficult customer to brainwash, and nine months in he was expelled from the program, and subsequently departed from the United States.

In 1964, Clark exacted his revenge. America, Their America, his travelogue and memoir of the fiasco, was published (the book was re-issued in the run-up to the 2016 elections in the United States). With it, J.P. Clark would unwittingly take part in one of the stranger postcolonial phenomena of the 20th century.

One of the hallmarks of imperialism in Africa has been its arrogation to itself of the ability, through literature, to define a people and their location through reported observation enabled by travel. In America, Their America, it is Clark who erects this imperial observatory on foreign soil. Where the usual postcolonial program was defensive against sly and blatant imprecations of the subjectivity of Africa and Africans, Clark went on the offensive. Thus, the United States and what it meant to be American became “other”, were defined through Clark’s sensibilities. The imperial gaze had been inverted. Postcolonialism had itself become imperialism.

But stranger things were yet to come.

In 1984, Professor Robert M. Wren, once of University of Lagos’s Department of English, would publish J.P. Clark, a book-length study of Clark’s oeuvre. Wren was interested in Clark’s plays and poems, but to get at the poems in America, Their America, their provenance had to first be accounted for. Wren, mind you, was white, American and a Princeton alum. What followed was a “postcolonial” critique of Clark’s imperialistic portrayal of America, a critique as indignant as any of Achebe’s trenchant critiques of colonial literature. Imagine that: Clark as center and America as the margins that, through Wren, wrote back.

Just this kind of strange upending of categories is what Isoken participates in.

Still from ‘Isoken’

Still from ‘Isoken’In her 34th year, the successful, eponymous center of the movie finally – somehow – finds a man who is worthy of her attentions. That man is Osaze (played by the squint-eyed Joshua Benjamin), a suave returnee Afropolitan born of good Bini stock who has recently raised US$3million for his business.

It’s classic. One man’s sustained attention begets another. Where were they before now? is probably a question many women (and men) have been forced to ask the heavens. Isoken Osayande, played by the slinky Dakore Akande, runs into Kevin (Marc Rhys) – a wise-cracking English photojournalist with the Associated Press who will not smell US$3million in three life times – in farcical circumstances. (Is a lot of money the new white skin?)

Things develop – or degenerate. Isoken eventually acknowledges that she finds Osaze enervating and Kevin energizing. To proceed as the world wants is to die. Cue bedlam.

Nothing has exactly been out of place so far. But at the meeting called to resolve – or at least make sense of – the bedlam, Isoken is forced to reveal the centrality of Kevin to the state of things. What – another man? No, not just another man. An English one. The one true love of her life. A white Englishman.

There’s shock. Played by the preternaturally beautiful, ever theatrical Tina Mba Isoken’s mother Yesoken’s reaction is particularly telling. It’s an unusual reaction, the sort of alarm a mother might emote upon finding out she’s been housing a collaborator with the invading Brits in Overanmen’s Benin. Or the sort of reaction a white Alabama woman marrying a black man might have elicited in 20th century (who am I kidding?) US of A.

Still from ‘Isoken’

Still from ‘Isoken’A lot has happened since Overanmen was king. By design, Africa has largely been centripetal, a votive vortex to a grasping, overbearing West, blackness to whiteness, barring some occasional tokenisms – like independence.

In a place where whiteness is what is usually culturally aspired to, it feels very gratifying that Isoken, like America, Their America, has marginalized whiteness, has once again made whiteness the subversive choice, something that instinctively arouses startling shock, not drooling, starry-eyed admiration. Yesoken’s instinctive reaction in particular made Kevin something like that black man, and the choice something like his marriage to the white Alabama woman, a subversion of the reified status we often ascribe to whiteness.

The film is a rom-com and the moment soon dissipates, but with Isoken, we are back to basics. For a tiny little bit.

July 18, 2017

Jonathan Jansen’s lopsided view of #FeesMustFall

Students at UWC during #FeesMustFall protests. Image Credit Barry Christianson.

Students at UWC during #FeesMustFall protests. Image Credit Barry Christianson.Jonathan Jansen, the former vice-chancellor of the University of the Free State in South Africa likes to project himself as someone who does not like beating about the bush. He often uses his prominent media profile to make strong statements about the state of education in the country. The decisions he made during his tenure as vice-chancellor were controversial at times. His withdrawal of charges against the “Reitz Four” – racist students who humiliated five black workers – shortly after Jansen’s appointment there in 2009 in particular received a great deal of criticism.

During his inaugural speech, Jansen argued that punishing individual racists would not solve systematic racism, and he even went as far as apologizing on behalf of the University for the students’ horrific actions. This argument resonated with the one put forward at more length in an earlier book, Knowledge in the Blood: namely that accountability for racism or the humiliating initiation rituals at historically Afrikaans universities should not be shifted onto individual students, but that instead its historical and structural roots should be examined.

Surprisingly, Jansen was much less forgiving of students of the #FeesMustFall movement during the 2015 and 2016 protests. Jansen was quite outspoken in his condemnation of the movement on social media platforms. In this new book, Jansen elaborates on his criticism of #FeesMustFall, and in line with his previous work, he doesn’t see the protests as originating from individuals or individual groups (although he does map the fragmentation of the movement as an overarching national protest in 2015, to a more campus-bound one in 2016). Instead, he sees the uprising as stemming from greater societal issues: an unwelcoming institutional culture; structural inequality; a lack of preparation for tertiary education in primary and secondary education systems; disillusionment with government’s moral bankruptcy; corruption; and declining support to universities.

As indicated by the book’s subtitle, however, Jansen does not view the student protests as a positive response to these varied and immense challenges; he believes the movement has sparked a cycle of disruption and destruction that could mean the end of public universities.

Jansen’s framing of the student protests as violent conflicts (instead, perhaps, as a difficult but important contestation about fundamental constitutional rights), is clearly illustrated by the presentation of the book: a type of war report, dispatches from the trenches, from the viewpoint of the generals of one side of the battle – the vice-chancellors affected by the protests. Jansen interviewed the university leaders to get an insider’s view of how their distinct institutions were affected by the protests, but also – and this is the most intimate part of the book – how the vice-chancellors personally reacted to the stresses and danger of the protest actions, how their lives and the lives of their families were affected and how they managed that impact. These interviews are revealing, and highlight the effects of the tension around the fragile situation and personal attacks on vice-chancellors, often in a touching way.

Jansen is also critical of the rhetoric around “decolonization” of the curriculum that often lacks intellectual depth and precise definition. He also has it in for the media, both mainstream and social, that often sat in wait for conflicts to erupt on campuses rather than conduct in-depth analyses of the problem.

Another issue Jansen tackles is the “welfarisation” of the South African university: the increasing role that universities play in providing socio-economic backing to students – from psychological support to accommodation or meals – and the expectations this creates among students. Add these expenses to a balance sheet that is increasingly skewed due to declining support from government, pressure on students from rural and poor areas to succeed to embark on a career that could help them support family members, and demands on institutions to decolonize in ways that often amount to racial essentialism, and you have a recipe for a nearly impossible task for universities to remain sustainable and internationally competitive.

The picture Jansen paints is indeed a worrying one – not only because of the tactics the protesters started resorting to, but also precisely because of the depressing underlying range of economic, political and social factors that he outlines. Yet, one can’t help but wonder whether the tone of his criticism, which sometimes borders on contempt or Afro-pessimism, exposes something about his own exhaustion and frustration arising from the position he held.

Regardless of how informed Jansen might be, by only interviewing vice-chancellors and no student leaders or lecturers who are more sympathetic towards the student movement, the book provides a one-sided image of the events. Although Jansen refers anecdotally to his interactions with students, the book’s focus on the experiences of the vice-chancellors privileges the institutional perspective. The principle of audi alteram partem falls by the wayside, and one can but wonder what the book would have offered had a more representative range of interviewees been sought.

What motivates a student to face teargas and armored police to march to Parliament and the Union Buildings? Is it really simply disillusionment and anger that maintained the movement, or is there a hopeful message to find here as well, namely that this generation of young people considers their education important enough, and corrupt governance contemptible enough, for them to put their bodies on the line for those beliefs?

These are the questions which Jansen’s dystopian book unfortunately does not provide the answers to. Although the reader of this book will be provided with an insider’s insight to the institutional side of the conflict, the questions asked by the protesting students require a multi-leveled answer, one that will have to draw on all the knowledge and experiences that scholars and students can provide.

The students have confronted us with a range of political, economic and intellectual questions to be answered – not merely posed a problem that needs to be managed.

* This review first appeared in Rapport, a publication of Media24.

July 17, 2017

How do you write about a flawed film?

Still from Waithira

Still from Waithira“What are the ingredients that make up a life?” wonders filmmaker Eva Munyiri at the beginning of Waithira, a film that, in her words, is “a portrait of family, and a study of migration, assimilation and generational spirit.” Here she patches interviews with family members across various geographies and generations–from Dresden in Germany, to Mutuini in Kenya and North Wales–to reflect on the impact they believe their grandmother Waithira, who the film is named after, has had in shaping all of their lives.

I’m not a sophisticated film watcher, but some of the ingredients that made up my concerns while watching and reviewing this film are how to applaud the important subject, capturing images and creative bricolage that feature in this project made by a vibrant African female filmmaker, while also critiquing some of what I see as its limitations.

A film that is anchored in the portrait of a resilient grandmother, who has raised many generations through great sacrifice and determination is, undoubtedly, much warranted. The tributes to her by all of those who recall her here offer tender insights into this fearless matriarch. At the same time, for the most part, it seems that what is most valued in two of the three members of Waithira’s family interviewed, progeny of more or less the same generation and from whom we compose a portrait of Waithira the senior, is their intelligence, sure, but also their ability and desire to live in northern metropoles far from home in Kenya.

It is wonderful to see all of these beautiful women charting new paths in different places, and whose freedom and possibility are, so we are to believe, an inheritance from a righteous grandmother. At the same time, better linkages between these scenes was required as we have to clutch at many tenuous strings in order to make our own connections (perhaps this was the intention?).

It seems there are very many sub-themes in the film; displacement and exile, non-traditional women, the filmmakers excavations of herself, freedom as inheritance, pasts that are buried deep but that can never fully disappear, family disintegration and even Mau Mau. Unfortunately, they never fully come together in a way that brings all of these memories through one central nervous system. Though some scenes are offered similar staging – such as when all three Waithira’s are doing their nails or traveling by bus in three different spaces – for the most part they remain visually effective but disassociated recollections that leave the viewer grasping.

When the sole male protagonist, her uncle, is interviewed about his experiences during the 1952-1960 state of emergency, he talks about the immoderate beatings, denial of education, the confiscation of family livestock, imprisonment of fathers and other ways this time was registered by a child watching imperial violence unfold in his family. It is not so much the words, but the embodied way that he narrates this period – simultaneously a pain-laden contortion and parsimoniousness – that critically establishes the experiences of Mau Mau and their supporters. We need to hear these stories. Especially since (against the irony of a president like ours named Freedom and the fact that Mau Mau (also known as The Kenya Land and Freedom Army) and their descendants are likely the most over-researched group in Kenyan history but are still landless, the recent monument in their honor seems to signal an imposed foreclosure, (an imperial “dusting shoulders”), to prevent greater discussion into how they have been forced from our past and present.

My concern with these references to Mau Mau, however, is what I perceive as the overwhelming focus on Kikuyu loss during this period. I fear this contributes to the unproductive pile of Kikuyu nationalist kaka responsible for many of the circumstances we are in at the moment. When uncontested statements such as “other tribes were free and they were loyal to the British” are voiced by a protagonist without further elaboration, or the filmmakers narration, from an unnamed source, that “the Kikuyu could easily be described as the most exploited group of Africans in Kenya” proceed unchallenged, I fear it reifies Kikuyu exceptionalism and this, in my opinion, has a range of dangerous implications. Is an uncritical nostalgia to blame for these musings? Should we attribute it to artistic navel gazing? Whatever the motivation, it remains (at least for me, a Kikuyu, most uninterested in Kikuyu nationalism) deeply unsettling.

The first two lines of the film proclaim: “The knots are untied and I go off untethered.” Poetic. Definitely. But maybe if Waithira’s story was presented as a symbol of other grandmothers and women in Kenya and beyond – those who had to encounter the worst of colonial and postcolonial violences through their bodies and spirits – it would have allowed for more texture and breadth. Perhaps if there was more recognition of the middle-class privilege that permits for the worldliness of most of the female characters presented here, it would help us discern many more of the complex layers that assemble women’s experiences across multiple generations.

Ultimately, while we get to see some of the ingredients that make up Waithira’s life, and vivid cinematography of the places where her life and memory have been extended, as a viewer I would have preferred more knots to be tied and a little less untethering.

July 16, 2017

Sunday Read: For us, Zimbabweans, South Africa is home

Image of Johannesburg’s skyline by Babak Fakhamzadeh. Via Flickr.com

Image of Johannesburg’s skyline by Babak Fakhamzadeh. Via Flickr.com“Zimbabwe” is fodder for all kinds of rhetoric, whether populist or conservative, that now swirls among South African political and economic elites. You just have to declare someone a Zimbabwean or use Zimbabwe as some kind apocalyptic future. It has become a potent political takedown. Take for instance, the allegation by Vytjie Mentor, a former MP of the ruling ANC party, that new finance minister Malusi Gigaba is a “Zimbabwean.” In another case, the discredited general secretary of the powerful South African Transport and Allied Workers’ Union (SATAWU) and ANC branch member, Zenzo Mahlangu, faced the same fate. Mahlangu suffered a worst fate: His political enemies made sure he was deported.

Even President Jacob Zuma is measured by how much he is leading South Africa to emulate Zimbabwe. Since coming into office in 2009, his government has careered from one corruption scandal to another. In the latest scandal to grip his administration, Zuma is accused of allowing financial and political dealings between the state, his sons and the shady Gupta family. To some, this is a stark reminder of the rampant patronage politics in neighboring Zimbabwe that contributed in turning the country into a corruption-filled cesspool.

“Zimbabwe” is also a bogeyman. It’s an uncomfortable reminder that, if not addressed with the urgency they deserve, or if left in the hands of opportunistic politicians, morally imperative questions like the struggle for land and its redistribution, can go terribly wrong. Again, some populist outfits, often with undefined agendas, are quick to take “Zimbabwe” as a launch-pad for their incendiary and racially charged rhetoric. For example, Andile Mngxitama of the “Black First Land First” movement delights in posturing as a champion of black people who will “follow Zimbabwe” and take land from whites “by force.”

Yet, when “Zimbabwe” is not used as a synonym for insults, contempt, and scapegoating, we, from the lands north of the Limpopo river, have always braved the bone-jolting tracks of the savanna to Johannesburg, Durban, Kimberly, and Cape Town to leave marks that are not easy to ignore on the social and political landscapes of those places. We have pursued education, sport, religion, and various forms of activism – in short, we have actively engaged ourselves in all markers of civic life. For us, South Africa is just across the river. We consider ourselves an indispensable and integral part of its national life, because it is our home.

Clement Kadalie, the godfather of black trade unionism in South Africa, born in Malawi, honed his skills in Zimbabwe and arrived in Cape Town an accomplished proletarian. The celebrated ANC stalwart, and first black African Nobel laureate, Chief Albert Luthuli, gazed at the sun for the first time in Bulawayo. In song, poetry, stories, and other genres of popular culture, we leave indelible spoors. Men and women, black and white, from Johannesburg to New York, were dazzled by August Musarugwa’s saxophone as he churned out hits like “Skokiaan” (or when it was covered by musicians like Louis Armstrong – Ed.). Dorothy Masuka’s perfect vocals took her from singing in the eating-houses of Bulawayo to being one of the most formidable anti-Apartheid voices. Born to a Zimbabwean father, Dj Oskido’s influence in the emergence of the popular “kwaito” music genre can’t be overlooked. The same can be said about Anesu “Appleseed” Mupemhi, who made his name as a chanter in the kwaito trio Bongo-Muffin. These artists built a religious following among music- loving southern Africans during careers spanning more than two decades. Others wedged themselves into television and film studios. Alyce Chavhunduka, Peter Ndoro, Leeroy Gopal, Simba Mhere, Tendai Chirisa and Luthuli Dhlamini are easily remembered and much-loved faces of South Africa’s prime-time television.

The raw physical strength of Tendai Mtawarira made him a household name in South African rugby. Popularly known as “Beast”, Mtawarira will be remembered for as one of the few black players to honourably don the green and gold colors of the South African national team, in a sport that is notoriously allergic to racial transformation. From the mid-1990s, Zimbabwean-born football players also captured the imagination of sport-crazed South Africans. We can count on the list, Ian Gorowa, Wilfred and William Mugeyi, Cleopas Dlodlo, Robson Mtshitshwa, Alois Bunjira, Adam Ndlovu, Benjamin Mwaruwaru, Tinashe Nengomasha, Khama Billiart and Knowledge Musona, among others.

Many of us, however, never made it onto the front pages of newspapers and magazines. “Shosholoza, Shosholoza kulezo ntaba” (“go forward to those mountains”) sang our migrant workers, in awe of the train that that took them through the forbidding mountains and across the Limpopo River, to labor on the mines of Johannesburg. We crossed, and continue to do so, the crocodile-infested river and the unpredictable Kruger National Park. We brave the guma-guma highway men who patrol the bushes of Musina, the unceasing road accidents, the pesky police and boarder officials. We sustain transnational households on both sides of the river, ignoring those geopolitical lines scribbled in Berlin of 1884. Even when vulnerability mars our movements, we calculate all that before crossing to either side of the river. We turn the tragic into the jocular. It is home after all.

“Xenophobic pogroms” must be a “rude reminder” that one had to visit the other side, someone once joked, and the gumbakumba deportation trucks from South African police are the “free transport”. Clamp downing down on us in Hillbrow, under the pretext of “managing immigration” just sends us under the radar. We render ourselves invisible or present fake chidhuura documents. For us, that Berlin line is “fake” and deserves “fake” legitimation.

We won’t quit, because for us, Zimbabweans, South Africa is home. We’ll jump that apartheid era fence, with or without the dompas.

July 14, 2017

Biafra as memoir

In 2005, a former diplomat from the Republic of Biafra named Godwin Alaoma Onyegbula reflected in his memoir on what being Nigerian meant to him: “I was born in this country, over seventy years ago, and know no other country better than I know Nigeria. I have lived through colonial Nigeria, independent Nigeria, Biafran Nigeria, and present Nigeria.” Onyegbula continued, “We think we have lived through [this], [as] one country, but experience suggests otherwise. It is becoming more difficult to find an ‘authentic’ Nigerian; that is, someone whose ‘Nigerianess’ is obvious, and clearly distinguishable, to himself and others.”

In the last 50 years, hundreds of people like Onyegbula who supported Biafra or fought against it have written their memoirs, ranging from small hand-printed pamphlets to thick, heavily-footnoted volumes. In various ways, all address what it means to be Nigerian in the wake of the Nigerian Civil War. In the long period of military rule that followed the end of the war, closed archives and an officially enforced silence meant that few historians openly reckoned with Biafra’s legacy.

Fiction was one site where Nigeria worked through the meanings of the war, especially in the work of well-known novelists, such as Chinua Achebe, Buchi Emecheta, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and Cyprian Ekwensi. Today the younger fiction writers, Chinelo Okparanta, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Sefi Atta are helping to bring debates about the war back into public discussion.

But by volume, the most significant body of writing on Biafra is neither history nor fiction, but memoir. A vast number of memoirs on Biafra circulate in Nigeria, and only a fraction of them are available outside of the country. The topics they address vary, from fiery political screeds on the causes and consequences of the war to intimate recollections of suffering and loss. Many, though not all, are written by people who supported the Biafran side. Some blend genres, mixing rumor with recollection, and a few take liberties with the war’s plot. As Onyegbula candidly warned in his own memoirs, “biography becomes boring when entirely true.”

Virtually every important military figure on both sides wrote accounts of their lives (some, like Olusegun Obasanjo, wrote more than one). A fair number of these were ghostwritten or “as told to” someone else; penning memoirs for prominent people has become a cottage industry for Nigerian historians and journalists. The recollections of well-known figures in the war – government officials, officers, scientists and intellectuals among them – are widely read and discussed in Nigeria today. Some are hawked in bus stations and taxi ranks, alongside self-help books and prayer manuals. The contents of one unpublished autobiography by Emmanuel Ifeajuna, a 1966 coup-plotter turned Biafran officer, generates enormous speculation about the conspiracies leading up to the war.

But what is most remarkable about Biafra’s autobiographical literature is the number of ordinary people who wrote their memoirs. Most are privately published in tiny editions, intended for personal distribution rather than sale. They contain greater moral shading than most writings on the war – far more than the records of international humanitarian organizations and foreign governments, which are quickly becoming the go-to source for historians of Biafra. Their authors include market women, rank-and-file soldiers, farmers, bureaucrats and teachers. Deserters and small-time war profiteers wrote them too, suggesting that there is more than self-aggrandizement to the war stories that ex-Biafrans tell. Their anger is often tempered with regret, and few are tales of unmitigated bravery or heroism. As a Biafran private named Thomas Enunwe recalled of his time in uniform, “going to fight in the battle field was like going to be tied up for the firing squad.”

Enunwe and others like him wrote to instruct future generations, to stake claims (political and otherwise), and to set the record straight about their actions during the war. They argue sharply with one another, and with the versions of events that both the Nigerian government and new Biafran movements like the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) and Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) would prefer to tell. As Biafra comes back into the headlines, it is worthwhile to look at how those who experienced the war accounted for themselves in its aftermath. Both sides of the debate will likely be surprised by what they find there.

July 13, 2017

South Africa’s Very Own David Brooks

Jonathan Jansen. Image by Penn State University, via Flickr.com

Jonathan Jansen. Image by Penn State University, via Flickr.comJonathan Jansen’s celebrity has always struck me as a bit of a throwback in contemporary South Africa, a final remnant of the preemptive post-racialism of the 1990s. To be fair, it was no mean feat for a black man to waltz into the University of the Free State, one of the country’s most notorious bastions of troglodyte racism and set about wanting to transform it into a symbol of reconciliation, let alone a majority black university. The previous vice chancellor (the equivalent of a university president in an American context) resigned after four white students filmed themselves forcing five black workers to eat food upon which the boys had just pissed, and Jansen took over. As the story goes, he forgave the students (without, I should add, getting the workers’ consent to do so) and invited them to return after they’d apologized. They didn’t, and they never returned. Jansen then used the incident to launch a program of reconciliation on campus.

Yet what’s so odd about Jansen’s brand of post-racialism isn’t his emphasis on reconciliation. Save for actual racists, no one’s against reconciliation where such a thing is possible. But that’s the key phrase: where such a thing is possible. I’m not in the business of kicking dead horses, but it would be bizarre to read Jansen’s transformation of one university as an indication that South Africa’s higher education system has been substantially integrated, decolonized, or whatever other concept we might apply. But in a talk in Cape Town on Wednesday night, July 12, this is precisely what he did. An employee at the Book Lounge in Cape Town’s city center told the audience that he couldn’t recall a bigger turnout for a big launch in the entire time he’d worked there. It was hard not to notice that the crowd was predominantly over fifty and white. This isn’t to say that it was entirely white — of course it wasn’t — and there were plenty of younger people there. But it’s worth noting that a talk on race in higher education by a black man — though he’d of course disagree that the talk was about race at all — was attended largely by older middle-class whites who seemed to hang on his every word.

Jansen recently released a book on the ongoing student struggles across South Africa, but from the perspective of the administration. For As by Fire: The End of the South African University (reviewed here), he interviewed eleven vice chancellors across South Africa. As he opened his talk on Wednesday, he told the crowd that the South African political scientist Susan Booysen’s edited volume Fees Must Fall (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2017) conveys the student perspective — and even includes a couple of actual student contributions, as if it were shocking that people in their early twenties could pick up a pen — and that he was trying to bring the administration’s perspective. We also need workers to write a volume, he added, pushing the pluralism of “rainbow nation” post-racialism. If only the various perspectives could hash it out, everything would be fine.

He then took a step back: actually, Booysen’s volume doesn’t speak on behalf of all students — just protesters. And it leaves out a second major constituency: these students’ parents and alumni, who have a stake in the image of the university. This was huge for Jansen, who repeatedly returned to his alma mater — Stanford University — as a point of comparison. (Jansen, who grew up in Cape Town, did his undergraduate degree at the University of the Western Cape; he subsequently obtained a Ph.D. in Education from Stanford). He told us that other than Harvard, no school in the U.S. has as much money as this private university, and that it was constantly constructing new buildings, not to mention investing in Silicon Valley. Of all the signs of academic success, he picked a construction boom and investment in the private sector? And of course all of this was beside the point. Why was he comparing one of the richest schools in a country with some of the top universities in the world to a place in which all major universities are public?

Jansen during the book launch at the Book Lounge. Image by the author.

Jansen during the book launch at the Book Lounge. Image by the author.But Jansen was obsessed with the American comparison. He complained that South African newspapers are kak, but in the US, they have The New York Times. He asked if anyone had read David Brooks’ column yesterday. It was, he insisted, better than anything ever published in a South African paper. I snorted a little, assuming he was joking, but then I realized: Jonathan Jansen is totally the South African David Brooks. The column he was citing was about how what appear to be class divisions in education aren’t really about structural barriers at all, but about culture. (Brooks went on about how his friend with a high school education couldn’t recognize certain kinds of ham.) And the persistent segregation of South Africa’s public education system isn’t about racism, racialism, or racial capitalism, Jansen would echo; it’s about a failure to truly speak to one another!

I couldn’t help but wonder why Jansen was focused so intently on signs of elite status in a country attempting to remedy the effects of decades of apartheid schooling — but he answered my question before I could finish asking it. We don’t want to quash individualism and turn our higher education system into a factory. Universities should be for cultivating leadership skills among the best and the brightest, and other such snooty platitudes. In other words, South Africa’s last surviving champion of post-racialist reconciliation didn’t seem so intent upon transformation after all.

And race? It didn’t even come up until the Q&A period. Not once. As a proxy though, Jansen did rail against the concept of “decolonization” that characterized South African student struggles in what we might call their third phase. To project my own periodization upon his telling, it all began with #RhodesMustFall. A coherently organized student movement at the University of Cape Town worked not only to topple the Cecil Rhodes statue, but they did so in a way that was immediately intelligible to the (white) middle class public. This was good.

Phase 2 was also good. Until 2015, he explained, the movement was nonviolent, and even better, non-racialist. For this, he insisted, student activists should be applauded. This of course maps onto #FeesMustFall, a student-worker alliance against fee hikes and outsourcing on campuses across the country. Or in other words, this was the moment of united struggle in the name of class.

But then #FMF gave way to a third period — decolonization struggles — in which students turned violent, racist, and misogynistic — all words he specifically attached to this movement. It was obvious that his emphasis was on his perception of these student mobs as racist, by which he seemed to mean that they articulated their demands in terms of race at all. “We’re all subjects of a great colonial plot,” he joked, before launching into a pedantic lecture about the concept of “decolonization.” It comes from three authors, he insisted: Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and Albert Memmi, and they were all writing in and about the 1960s and 1970s. Context is essential. We’re no longer colonized, nor is South Africa recovering from the immediate aftermath of colonization, and besides, even if it were, all three of those authors wrote in response to French colonial atrocities.

“Let’s not overstate the problem,” Jansen continued. “Let’s not name it wrongly because that is disingenuous.” Given how frequently he was reminding the audience of his academic training as a social scientist, I couldn’t help but wonder why he would reveal that he hadn’t read any postcolonial theory written in the past forty years, or why he would feign ignorance, as if he couldn’t actually understand the meaning of the concept in its current context.

When it came to the Q&A, only one person challenged anything Jansen said — a young black man who implied that he’s a student at the University of Cape Town. He asked a pointed question about post-racialism, asking how we can talk about reconciliation and such when segregation persists and has even been augmented in many cases. He asked why we’re trying to discuss strategies for “fixing” public education in a room full of old white people. Why aren’t our parents here? he asked, gesturing to his group of friends. Look out the window! See all of the black parents walking to and from work down Buitenkant Street on the side of the Book Lounge? That’s why they’re not here. How can we discuss this problem as if it’s simply a question of reason, he was suggesting, when material conditions prevent the majority party from even being at the table?

I could see audience members rolling their eyes. It was the most substantive question of the evening, and easily the most thoughtful, yet Jansen gave it short shrift. He insisted that we can’t keep emphasizing race in every conversation, as if excising the concept from our repertoire would correspond to an eradication of racism (let alone racialism) in everyday life. But this corresponds precisely to the ideology of post-racialism in contemporary South Africa: it’s less about a verifiable observation than a strategy for shutting down any discussion of race whatsoever. No one could argue with a straight face that South Africa’s higher education system is anything approximating integrated, or that the geography of apartheid schooling doesn’t persist in a novel public v. private guise. But here was Jansen advocating an elitist schooling model in a post-apartheid context, all without so much as mentioning race, save for selectively denigrating the very concept.

No education crisis wasted: On Bridge’s “business model” in Africa

The dream is wonderful: provide a good education to millions of children growing up in poverty. That’s why Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, the World Bank and the Dutch Ministry for Foreign Affairs are pouring millions into a company that aims to turn that dream into reality. Investigations show, however, that both the children and their teachers get a raw deal.

Shannon May is clearly emotional when she walks onto the stage in early February 2017. The founder and strategist behind the world’s largest chain of kindergarten and primary schools is about to speak to a room full of women. She will talk about education, motherhood and the reasons why she founded her company, Bridge International Academies, with her husband Jay Kimmelman in 2008.

May and Kimmelman are in Nairobi, the city they live in and where Bridge has its headquarters. About 70 percent of the more than 100,000 pupils attending Bridge schools live in Kenya and around 6,000 staff work and live there. It was also the company’s base for expanding into Uganda, Liberia, Nigeria and India.

In her speech, May tells the story of the founding of Bridge: “I was speaking with mothers and with fathers, about their struggles… two things came up across hundreds of conversions I had… the first was health… the other thing was education.”

This made May think about her own childhood: if she hadn’t had good teachers, she would never have been admitted to Harvard and she would probably never have worked at Morgan Stanley. She would certainly never have come up with the idea of setting up Bridge, the “edu-business model” that aims to provide affordable, high-quality education to millions of children from families who have to live on less than US$2 a day. When the couple founded Bridge in 2008, their dream was to emancipate these children.

The exact number of children involved is unclear. Sometimes her husband talks about 700 million children, at other times it’s around 700 million families. According to the World Bank, 767 million people worldwide currently live below the poverty line of 1.90 dollars a day. Whatever the exact figures are, they are high and education opportunities fall short of what is needed. There are not enough good state schools and private schools are often too expensive. May and her husband have spotted a gap in the market: education needs to be better than what state schools offer, and provided at only 30 percent of what the state currently spends per student.

May, close to tears, continues her speech in Nairobi: “Bridge is different because it exists for only one reason, it’s so that every child, not just the rich kids, not just the kids in the cities, not just the kids who have mothers and fathers who can look after them and teach them at home but every kid no matter what else is going on in their lives can go to a great school.” She is even more positive in an interview: “We fight for social justice, to create opportunities.”

And for profit. According to her husband, the “global education crisis” is worth about US$51 billion a year. In 2013, Kimmelman explained in a presentation how, for less than US$5 in tuition fees per pupil per month, Bridge could grow “into a billion-dollar company” and “radically change the world.” Earlier he and May promised that they could do this for US$4 per month per pupil.

Big dreams and even bigger promises. However, my research and research done by others shows:

that their quality claims have not been supported by any independent research;

that the education provided turns out to be more expensive than promised;

that underpaid teachers have to recruit additional pupils;

that they have dismissed criticism from non-governmental organizations and trade unions;

that critics are silenced;

that a PR offensive has been launched in order to continue selling the education services provided.

Furthermore, €1.4 million of Dutch taxpayers’ money has been poured into the company. Dutch support was provided because Lilianne Ploumen of the country’s Labor Party, currently caretaker Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, believes that Bridge uses an “innovative and cost-effective education model, which is able to keep tuition costs per child down.”

How do you improve education, make it cheaper and also make it profitable? May and Kimmelman have come up with an “innovative pedagogical approach.” The possibility of setting up a few thousand standardized schools within a few years is to be the first innovation. The profit made from each school may be low, but once half a million pupils are recruited — the number of enrollments that Bridge needs to break even — business really takes off. The plan is to reach two million pupils by 2018 and 10 million by 2025.

This rapid growth would be made possible by using Bridge’s second innovative method, namely its very own approach to the role of teachers and their salary scale. May believes that “qualities such as kindness” are more important than diplomas and this allows for significant savings. In Kenya, where the starting salary for qualified teachers is around US$116 dollars a month, Bridge teachers usually earn less than US$100 a month. However, as Kimmelman explains in a presentation, teachers can earn bonuses by recruiting new students themselves. Marketing is a core task for both teachers and school principals.

A third innovative aspect, explains May, is the smart use of technology. It works like this: a team of “master teachers” designs digital “master lessons” that are so detailed that all a teacher needs to do is read them from a special Bridge tablet (know as the Nook).

Leaning how to use the Nook is therefore a key component of the crash course that Bridge teachers must complete. Over three to four weeks, they learn how to download new lesson material, how to present it, and how to record daily scores and progress made with the lessons.

This last skill is crucial, says May. It allows Bridge to see “hundreds of thousands of assessment scores” every day and to find out “what works and what doesn’t.” The “extremely robust data” can then be used to “continuously improve the teaching material.”

Setting up schools from scratch, paying teachers and developing and maintaining technology all cost money.

“One of our challenges when we were first pitching Bridge to investors was getting them to… see people living in poverty not just as beneficiaries but as customers,” May explains in a 2015 World Economic Forum video. It must have been a convincing argument because May and Kimmelman have attracted more than US$100 million in support since Bridge was set up in 2008. Supporters range from venture capitalists, like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, to development agencies such as the World Bank.

My request for information under the Dutch Freedom of Information Act revealed that the Dutch government, too, invested nearly €1.4 million in Bridge between 2015 and 2016 via contributions to the Novastar East Africa Fund. Minister Ploumen says that this “indirect support complements the weak public education systems in these countries.”

Support is not only provided through funding. In 2015, the World Economic Forum named May “One of Fifteen Women Who Changed the World.” That very same year, the President of the World Bank, Jim Yong Kim lauded the Bridge business model as one for the future. And a few months ago, Bridge won the Global Shared Value Award, a prestigious prize awarded to companies that have a social mission.

It has made May and Kimmelman extremely self-confident. We have “definitively proven that it is possible to provide high-quality education […] and in doing so solve an increasingly urgent crisis for families, communities and countries,” May wrote in February of this year. Kimmelman even believes that international research shows that Bridge “students already perform better than others in six months.”

If that would be true, why have they still not reached those millions of pupils? Anton (a former academy manager with Bridge, who did not want his real name published) is familiar with the darker side of Bridge’s “innovative pedagogical approach.” Anton was fired after a year in the post when a quality assurance manager and a regional manager made an unannounced visit to his school and discovered three pupils attending in contravention of school fees policy.

The children were registered with Bridge, but were no longer allowed to attend classes because their parents had fallen behind with the payment of tuition fees. Anton knew that he was supposed to turn pupils away if their parents had not paid. He had already had his salary docked once and was at risk of losing his job if he continued to allow those pupils to attend.

Apparently, the children had returned because their parents were not at home and they didn’t feel safe outside. So, their class teacher had allowed them back into the classroom without getting Anton’s permission. But the visiting quality assurance and regional managers did not agree that this was a good enough reason and Anton was told to clear his desk.

On reflection, Anton says he is relieved that he is no longer working for Bridge. He was under too much pressure to attract new pupils and the “rigid payment system” put him in uncomfortable waters with parents. Every month, about half of the parents couldn’t pay their fees on time, and would get upset with Anton when their children were, again, sent home from school. These tensions made it even more difficult to attract new customers and to persuade existing customers to bring in new ones.

“We promised them heaven” says another former academy manager. John (name changed) says it was the only option, “otherwise, you lost your job.” He worked at Bridge for two and a half years before he handed in his resignation. The low salary and the heavy work load (60 hours a week, according to John) were contributing factors. His pangs of conscience were the deciding factor: he felt that he was “constantly deceiving parents.”

It wasn’t because Bridge had directly instructed him to “only mention the basic price to new customers and avoid mentioning additional costs, such as exam fees and uniforms.” But since his salary was partly calculated on his success rates, he often told half truths.

If parents weren’t happy with the strict payment arrangements and threatened to transfer their children to a school with more flexible system, John would think up an argument in an attempt to keep them, telling them for example “that there would soon be a sponsor for them who would pay the tuition fees on their behalf.”

How representative are these reports from these two former academy managers? Juul (name changed) can tell us more. Juul, a researcher, was part of a team that in early 2016 completed nearly four hundred interviews with Bridge parents (128), pupils (65), teachers (21) and academy managers. The research was carried out on behalf of Education International, an international trade union for teachers, which is not a competitor of Bridge.

The academy managers and teachers who were interviewed expressed the same frustrations as Anton and John. They described the marketing work as annoying, demoralizing and underpaid. The Nook script was considered to be restrictive and almost half of those interviewed said that they did not use the Nook as intended or sent “meaningless data” to the headquarters.

“You hear such sad stories,” said Juul. “Some parents took out loans to pay the tuition fees and were evicted from their homes because they were unable to make payments on time.”

Bridge, however, doesn’t agree with the research. In a statement, the company called the report nonsense. It claims:

Bridge internal data shows that 64 percent of Bridge teachers enjoy teaching in Bridge classes;

100 percent of them would like to grow with the company; and

96 percent of teachers appreciate the community engagements responsibilities assigned to them.

According to May, the study is therefore proof of the witch hunt that Education International started against her company. The organization had already published a similarly critical report on Bridge in Uganda. May continues to believe in her dream: “Changing the status quo is inherently a challenge to entrenched interests and existing models.”

But those “entrenched interests” aren’t finished with Bridge yet. Angelo Gavrielatos led the Education International research project. He shows me a short film in which Kenyans from various national educational institutions and former Bridge staff criticize the company’s infrastructure, facilities and teaching materials. For example, a former staff manager says that “people are being misled” with promises about an “excellent lesson package.”

A package, it should be noted, that has never been approved by the Kenyan authorities. A leaked letter from the Ministry of Education reveals that a Kenyan inspection had deemed Bridge’s teaching material “largely irrelevant to Kenyan teaching objectives” and that the teaching methods don’t allow teachers enough room to tend to pupils with special needs.

Education International is not the only organization to criticize Bridge. At the start of 2015, 116 non-governmental organizations sent a letter to World Bank President Jim Yong Kim. They stated that there was no evidence at all that Bridge had succeeded in delivering better results than competing state schools and criticized Kim for blindly accepting Bridge’s unverifiable “internal data.”

What’s more, Bridge is by no means as affordable as the company claims. In Kenya, the cost per student is between US$9 and US$13 a month once exam fees, uniforms, books and administration costs are included. The situation is similar in Uganda, the organizations write.

According to Bridge, the organizations’ calculations are entirely wrong. However, when asked, the company does not deny that, in practice, tuition fees are higher than the promised fees of US$4-6. May, meanwhile, continues to insist that Bridge’s prices are reasonable. Because, she writes, by sending their children to Bridge, parents have “determined for themselves that Bridge is affordable” and that they feel that the tuition fees charged by Bridge “are an appropriate rate.”

However, voices within the United Nations have also started to speak out against the Bridge model. When it was announced at the start of March 2016 that Liberia was considering outsourcing its entire primary school system to Bridge, the Special Rapporteur on the right to education stated that “public schools, their teachers, and the concept of education as a public good, are under attack.”

Questions are also being raised by the Ugandan government. Following an inspection, the Ministry of Education found that Bridge schools “showed poor hygiene and sanitation which puts the life and safety of the schoolchildren in danger” and decided that the company had to close 63 schools. May puts this setback down to troublemakers who have “sold lies to the Ugandan government.” Lies that “unfortunately the government has taken seriously.”

It’s Kenya where May’s dream really begins to turn into a nightmare. In August 2016, the Ministry of Education sent the company an ultimatum. Bridge was given 90 days to adapt the curriculum to Kenyan guidelines and ensure that at least half of the teachers had a diploma. If they didn’t meet those requirements, Bridge was at risk of having to close down all of its schools.

But Bridge won’t be beaten. It is trying to silence Kenyan critics, as shown in two leaked letters. One was addressed to the head of the national teachers’ union, the other addressed to the director of a national school association. The first was sent by Bridge’s law firm, the second by Bridge’s in-house lawyer. In both letters, the recipients are threatened with a defamation lawsuit if they continue to speak out against Bridge and portray it as a company that “is only interested in profit.”

Steps have also been taken in Liberia to counter negative reports. Anderson Miamen from the Liberian Coalition for Transparency and Accountability in Education described the situation to me in an e-mail. When he wanted to interview Bridge teachers at the start of this year as part of an assessment study, he discovered that they had apparently been “warned against speaking to visitors or researchers. Especially not about their welfare or that of the children.”

Bridge has also launched a PR offensive. The company opened a London communications office earlier this year and has advertised several vacancies for PR professionals who should have good contacts with the media in order to “promote and protect” Bridge’s reputation.

Since then “Bridge’s success” has been widely praised on Twitter. For example, “A survey shows that 87 percent of the Bridge parents believe that Bridge teachers are well trained and that their teaching method is the best.” There is no link to the survey, only photos of smiling pupils in Bridge uniforms. The new PR manager, Ben Rudd, did not want to send me the survey either. He did, however, send promotional material that refers to the same internal data and mysterious studies. He also offered to arrange a “high-level quote.”

And the data that May earlier described as “robust?” They are up for sale. At least, that’s what a leaked Bridge presentation, meant for investors, from 2016 suggests. In this presentation, Bridge outlined new profit-making opportunities, including the sale of customer information to lenders and insurance companies, and increased profit margins on school lunches and student uniforms.

What has happened to May and Kimmelman’s dream? Opposition from governments, non-governmental organizations and trade unions seems to have slowed down Bridge’s growth considerably. It also looks like the company is not going to reach its planned target of two million pupils by 2018. The company wrote me that it currently has just over 100,000 pupils.

Not all of Bridge’s innovations are bad, of course. Absenteeism among teachers appears to be lower at Bridge schools than at state schools. Juul says that other schools could also take Bridge’s electronic payment methods as an example as a way to tackle corruption.

As for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and its investment of €1.4 million, spokesperson Herman van Gelderen informed me by e-mail that compliance with quality standards and affordability are part of “our involvement and dialogue with Bridge. The findings in the article serve as a basis for discussing these issues with Bridge.” The same applies to the teachers’ workload and remuneration.

Van Gelderen points out that the quality of the education provided is better than at state schools. To back up his argument he refers to a national test in 2015 and 2016 on which Bridge students apparently scored slightly higher than the national average. But even if Bridge performs better than state schools, it still doesn’t tell us anything about the quality of the education provided by Bridge. Because — and May also admits this herself in an article — the poorest and, therefore, often weaker students, who bring the average exam scores down, mainly go to state schools. Moreover, Bridge is a private school and can therefore also influence scores by not accepting weaker pupils or by unnecessarily making them repeat a year. In Education International’s report, teachers admit that this kind of selection occurs.

High-quality education cannot simply be provided using a universal script, and meaningful learning outcomes cannot be summed up in self-assessed evaluations. Especially not if they are part of a business model that does not tolerate transparency or independent evaluations, and where profit incentives, branding bluff and promotional spiel are rewarded more than honest, critical reflection.

* This is a translation of an article originally published in the Dutch news magazine De Correspondent (contact). Some names have been changed to protect identities. However, true identities have been verified by the editor-in-chief of De Correspondent. The leaked documents have also been reviewed and verified by the editor-in-chief of De Correspondent. This article has been translated from Dutch to English by Johanna McCalmont – translator; Tina Vonhof – reviser, provided by Translators without Borders.

July 11, 2017

Somalia, People of Football

Somalia has never qualified for the World Cup. For a long time, whether by lack of organization, money or crippled by civil war (1966-1978 and 1986-1998) they just didn’t enter. More recently the national team had to play “home” matches in Kenya and Ethiopia. Some players have been threatened by Al Shabaab, who, like the Taliban, considers football sinfull. But, as the the President of the Somali Football Association says in the documentary film, Men in the Arena: “Our people are a people of football.”

Somalia has never qualified for the World Cup. For a long time, whether by lack of organization, money or crippled by civil war (1966-1978 and 1986-1998) they just didn’t enter. More recently the national team had to play “home” matches in Kenya and Ethiopia. Some players have been threatened by Al Shabaab, who, like the Taliban, considers football sinfull. But, as the the President of the Somali Football Association says in the documentary film, Men in the Arena: “Our people are a people of football.”

The film is directed by American J.R. Biersmith. The main characters are two promising, young footballers, Sa’ad Hussein and Saadiq Mohamud. The first lives in Somalia (where he has been attacked and threatened by Al Shabaab), while the second lives as a refugee in Kenya. Fleeing war, they want to make it to the West and play football. The film follows their separate, and often connected, journeys (beginning with their participation in a regional tournament in East Africa) between Somalia, Kenya and the United States, becoming in the process a classic sports film, but also a corrective to one-dimensional portrayals of Somalis and Somalia, as well as political refugees. The film is now available on most on-demand services, including Amazon, iTunes, Vimeo, Youtube and Hulu [from July 10th]). Here’s the trailer:

Men in the Arena official trailer

We interviewed Biersmith over email.

The film’s title draws on a speech given by Teddy Roosevelt in 1909 in Paris. It so happen that he gave the speech after spending one year hunting in Central Africa and given that Roosevelt was also quite conservative in what he thought of Africans or how he related to them , w hy the title?

Ambassador Fred Ngoga-Gateretese, of the African Union Commission, referenced Roosevelt’s speech when he shared his thoughts about the Somali national team’s performance in the 2013 tournament that opens the film. When you spend the kind of time we did with these guys and fully grasp what each has been through, you quickly realize they don’t care much about critics. They care about their teammates, their families and the Somali fans that come in droves to support them. We thought about Roosevelt’s expedition and the hunt that took north of five hundred animals in the name of science, but we also thought about Mandela who had passed away during the tournament and the story of his giving the ‘Man In The Arena’ passage to the Springbok rugby squad at the 1995 World Cup. The Somali Football Federation lacks the resources, technical training and medical care to compete at this level but it didn’t keep them from showing up and leaving it all on the pitch.

How is your film , say in conversation with Western films and media coverage of Somalia, like “Black Hawk Down” or the many “pirates” films and documentaries?

Sa’ad was born just outside of Mogadishu in April 1993, just six months before the October battle in Mogadishu that became the basis of Mark Bowden’s best selling book and eventually an Oscar winning film. Saadiq was born three years later in 1996, but his mom had fled Mogadishu to join his father in Kenya late in 1993. That single event changed American foreign policy and subsequently changed much of what the West came to know about Somalia. Then Captain Phillips came along, and Barkhad Abdi was nominated for an Oscar. That was a wonderful story but his character played into the single story narrative of fear. We set out to try and broaden that lens and offer up a look at the young people that have called Somalia home since the war broke.

What would you say are generalizable about the experiences of Sa’ad and Saadig ?

If you’re born into a failed state I don’t know that anything is generalizable. Each family is doing their best to survive and youth grow up believing the only way to better their lives is to leave the country. Tahrib, trafficking, is all too often the path chosen despite the inherent risks. Sa’ad and Saadiq’s journey is somewhat unique because of their reputations as footballers in Mogadishu. We grew increasingly concerned about their participation in the film and inability to protect themselves given how candid they were – candor that we feared would make them targets.

In the film, the President of the Somali Football Association says “ Our p eople are a people of football.” Can you briefly outline the history of football in Somalia? It’s highs and lows, achievements and prospects?

There is a professional league based in Mogadishu with a rich history that reached peak popularity in the late 1970s and 1980s. The sports archives were destroyed in 2010, so it’s always been a challenge to fully wrap my head around the strength of the league, but through photos and accounts shared by fans and former players we got the sense that Mogadishu stadium was once the place to be. There’s been a number of interruptions and a number of people who have taken advantage of funds allocated by FIFA towards Somalia football but I’ve come to respect the commitment by the federation to keep the league going. Without a league it’s much more difficult to draw the talent required to put a competitive national team on the field.

Watching the film, we get a sense that you went beyond reporting and became involved the lives of both Sa’ad and Saadig . Is that a correct assumption?

We knew going in this would be an extraordinarily complicated endeavor, but I wasn’t quite prepared for just how difficult it would be. After the tournament in Nairobi, we knew we wanted to build the film around Sa’ad and Saadiq and that wasn’t going to be easy. I had to dig deeper to fully grasp where their lives were headed and how we could best capture their journey. When you do that, the walls come down, trust develops and truth emerges. It’s that truth that gets tucked away because of the fear of repercussions. I felt it was imperative that I deliver on the trust they placed in me.

When Saadiq came to America, he was 18 and knew nothing about this country or how he was to operate inside it. He needed support, he needed family, he needed time to grow and I along with my sister and brother-in-law realized just how important it was for him to get that support with each month that passed. Then I had to start working to get Sa’ad on safe soil because there’s no way he could stay in Mogadishu sharing what he did in the film. I never dreamed it would be the US, but once we got him in front of UNCHR in Kenya and the US State Department stepped in he was coming to America. The six months it took for him to get vetted was a nightmare. He didn’t speak Kiswahili, corrupt police got to him eight separate times chasing bribe money of which he had none, and he was surviving on food and shelter provided by Saadiq’s friends. When UNCHR called saying he was clear and he needed to make a decision about where to go in America, he said he wanted to be with Saadiq.

What are the current prospects for the Somali football team? Have things improved for the team since the election of Farmaajo as the country’s president earlier this year?

Banadir stadium has undergone extensive renovations and that’s a real source of pride for the federation. They’ve also developed another site with artificial turf so that’s a step in the right direction. Of course a return to Mogadishu stadium is the dream in large part because of what that would signal in terms of peace.

What has happened to the people (both Sa’ad , Saadiq , their parents and their close friend, Liban , who lives in the US and helped promote their soccer potential ) profiled in the film since it was made?

Sa’ad, Saadiq and Liban all feel a constant pressure to get money home to loved ones. Much more so for Saadiq who is still learning how to meet the demands of being a Division 1 student athlete. Sa’ad is working and continuing to chip away at his English at the International Institute in St. Louis. He plays in a pick-up league on the weekends. Liban is in the process of getting his citizenship, which is exciting because now he can go after the cyber security jobs he’s long dreamed about. In the meantime he’s driving for Uber.

What are the prospects for Somalia, in terms of its political future?

Good people and good intentions can get compromised in the political theatre, and that’s certainly the case for a place like Somalia where oligarchs cling to chaos for profit and tribal alliances are given priority. Having said that, Farmajo’s election in February felt like a real moment in the long road back to peace. To see images of people pouring into the streets to celebrate was encouraging, but he has a giant task before him.

We made two trips to DC to screen the film and on both occasions the Somali Embassy in DC was extremely supportive – especially Thabit Abdi, who was recently appointed the Mayor of Mogadishu. When I think about a man like Thabit and a woman like Hadiija Diiriye, the new Minister of Youth & Sport, I’m hopeful for Somalis future. I know we are excited about the prospect of working with both to get the film in front of Somali youth.

Do you think national football teams matter? If so, how does it matter for a place like Somalia?

There are few things more instinctual than finding an object to kick around as a kid and then trying to lure another kid to join to make a game of it. Football is the global game because anyone can play as long as you can form a ball and find some open space. Somali’s love football not only because it’s what they know but because it’s an outlet for fun.

There’s a scene in the film where the Somali national team coach is speaking to all of the players in a team meeting and we thought it was important to include because it’s a window into how coaches are teaching more than just football. They’re preparing these young people to be good teammates and leaders on the field and that translates to actions off the field. The coach was constantly reminding them that the nation was watching and it was important for young people to see how they conducted themselves.

Finally, what has been the reaction to the film, and its international reception, including in Somalia itself? Do people there generally agree with its portrayal of the country and its football?

Storytellers make choices in the editing room that can help shape what an audience can feel inside of a given scene. So the very nature of that process leaves room for critique. It also opens up the opportunity for discussion and inspiration. We did screenings across the country and that was great because we got to engage in thoughtful Q&A’s and witness just how much Sa’ad and Saadiq’s story impacted people.

There’s an old adage that says journalism is first rough draft of history and we took that very seriously especially in light of the destruction of the sports archives in 2010. We approached this film by focusing on the dreams of young people and the backdrop in which those dreams were experienced.

Sa’ad and Saadiq’s journies are a draft of Somali history. It’s their truth and that can’t be destroyed this time.

July 10, 2017

Nigerians: Gays, as long as they’re not our gays, are okay.

For a week in April, Richard Quest was in Lagos, Nigeria. I have always been fascinated by him. Quest has a hoarse voice, an odd demeanor and a presentation style that isn’t a common sight on television. He draws you in, even if you are not interested in business. I have been a fan since the first time I saw him delivering the business report on CNN years ago. Until his visit, I did not know that he was gay. The truth is, even if I had known, it wouldn’t have mattered. “Quest Means Business” is a brilliant show – and the sexual identity of its presenter makes not one jot of difference.

I was however, fascinated by the many Nigerians hobnobbing with him.

Quest was at Oshodi, the heart of Lagos mainland. He visited Tejuosho market, the main market on the Island. He spoke with industry experts. He took selfies with cleaners on Lagos roads. He ate jollof rice at a local arts center. He jogged on Lekkoyi Bridge with media entrepreneur, Mo Abudu and interviewed key Nigerian ministers. He was welcomed so warmly that he even took to Twitter to talk about Nigerian “friendliness.”

I would like to see this as a win in the fight against homophobia. It could be interpreted as a huge step forward that Nigerians interacted with an openly gay person without contracting “gayism” – one of my personal favorites in the informal homophobia dictionary. Nigerians breathed the same air as Quest, an openly gay man and no one died.

Sadly, this sudden “friendliness” of a largely homophobic society has raised several questions. Nigerian-born LGBTI activist Bisi Alimi, who lives in United Kingdom, suggests there is more at play. In a Facebook post, Alimi wrote, “Richard Quest is in Nigeria and getting a hero’s welcome. Lest we forget, he is a man living openly as gay, but what we do to our LGBT? Either kill them or imprison them. Shame on you hypocrites!”

Loaded in this are questions: would Nigerians still have welcomed him if they knew he was gay? Would they still have shone their teeth into the cameras for selfies? Quest’s visit to Nigeria perhaps may actually be pointing a finger at the double standards in Nigeria, especially for the LGBT bashers aware of his sexuality.

As many Nigerians who have been open about their homosexuality in Nigeria can attest, once you are out, the doors to opportunity start shutting. Alimi knows this all too well. In 2004, he came out on television show called “New Dawn with Funmi.” That singular act triggered off series of (re)actions. Firstly, it killed his acting career. As if that was not enough, he was physically assaulted on numerous occasions, and victimized to such an extent that he was forced to leave the country. It had a wider effect too: New Dawn was pulled off the air, and viewers were denied the opportunity to explore crucial issues that affect the rights of all Nigerians.

In 2103 Nigeria adopted the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA), which effectively legalized homophobia. Recently, Romeo Oriogun, a Nigerian poet who identifies as queer won the Brunel International Poetry Prize; he was celebrated by many in the literary community. Yet at home in Nigeria, he experienced a wave of hatred. So it is fascinating that within weeks we have two stark examples of intolerance towards a fellow Nigerian who happens to be gay, and high levels of acceptance and tolerance towards a gay British man. Reports of the effects of the SSMPA leave a bad aftertaste. With increasing mob violence, there are few places LGBT people can go for shelter and legal support.

After his visit, Quest tweeted, “The youth of Nigeria are the country’s secret weapon. I’ve been impressed with the young people I’ve met there.” Quest is right about youths being Nigeria’s secret weapon. It is something many Nigerians know. However every weapon has both the power to protect and the power to harm. Homophobia is on the increase, even among young people. Recently, there were reports of attacks at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Like Alimi, and Kenny Bademosi – the founder of Orange Academy who left in 2015 after coming out – too many young talented Nigerians are getting on the next boat, bus or plane to escape homophobia.

As he filmed “Nigeria at Crossroads,” Quest interviewed the who-is-who in Nigeria. Each of them suggested ways for the country to move forward – pointing out new directions for the economy, for education and health, even the environment. The one issue Quest and his guests did not touch on was human rights. For the LGBT people in Nigeria, navigating these crossroads may not be as easy as Quest made it seem as he meandered the Lagos markets. The truth is, most LGBT people in Nigeria can’t simply walk through our streets as Quest did with their rights protected. Few LGBT people can simply be who they are – as Quest is – and just wander into our hearts. Quest may mean business but the question is, does Nigeria? Countries that mean business keep their citizens’ humanity intact. They certainly don’t ostracize their best and their brightest.

July 7, 2017

Of gag rules and global partnerships

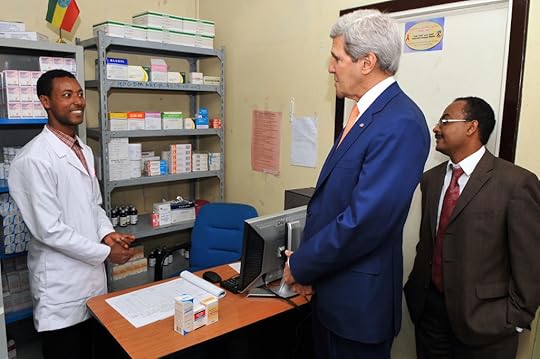

Secretary Kerry Visits PEPFAR-Supported HIV Clinic in Ethiopia. Image via US Dept of State Flickr.

Secretary Kerry Visits PEPFAR-Supported HIV Clinic in Ethiopia. Image via US Dept of State Flickr.On his third day in the White House, Donald Trump signed an executive order barring U.S. funding to international organizations that discuss abortion as a family-planning option. Women’s rights and reproductive health advocates immediately pointed to the grave effects that reinstatement of this policy, first introduced by the Reagan administration in 1984, would have in Africa. Several cited a 2011 study that offered evidence that enforcement of the “global gag rule” under the George W. Bush administration had the perverse effect of increasing abortion rates in much of sub-Saharan Africa by reducing women’s access to family planning services and causing some women to substitute abortion for contraception. The Trump-Pence administration delivered to their conservative Christian and pro-life voters by expanding the global gag rule to apply to all U.S. global health assistance, not just funding for family planning. Whereas the U.S. government’s current spending for family planning overseas amounts to approximately $600 million, its pot for global health aid totals more than $8 billion.

Together with the reactionary populism of “America First” that helped bring Trump to power, the expanded gag rule presents a challenge to the future of global health work in Africa and to one of its most touted ideals: partnership. It also provides an opportunity to reflect on the vexed history of that work and to reclaim partnership’s progressive political potential.

Over the past fifteen years, global health has emerged as one of the most prominent faces of American influence in Africa. In the wake of 9/11, the Bush administration paired the expansion of anti-terrorist military operations in the Horn of Africa and the Sahel with the extension of global health work through the establishment of the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The U.S. government funding for global health more than quadrupled while a number of private organizations, most notably the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, began devoting significant resources to improving health in sub-Saharan Africa.

Partnership was a keyword that accompanied this dramatic expansion. Global health leaders argued that their efforts differed from previous approaches by rejecting paternalism and advocating for equal, collaborative partnerships between wealthy and poor nations. As some declared in 2009, “The preference for the use of the term global health where international health might previously have been used runs parallel to a shift in philosophy and attitude that emphasizes the mutuality of real partnership, a pooling of experience and knowledge, and a two-way flow between developed and developing countries.” Partnership thus became a programmatic priority and affective ideal that global health practitioners struggled to make a political reality.