Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 283

May 6, 2017

“The past flows into the future”

It’s sad when you speak to a footballer and it’s impossible to discuss anything other than the ball.–Rachid Mekhloufi.

The football World Cup of 1958 is mainly remembered for two men. The first is Pelé, and the second is Just Fontaine. On the way to the semi final, which they lost to Brazil, Fontaine scored thirteen goals for France, still a world cup record. France beat Germany in the play-off to finish the tournament in third.

Absent from Les Bleues throughout the tournament was Rachid Mekhloufi, a twenty-one year old forward who played for Saint Étienne. Rachid was born in Sétif, Algeria, the son of an auxiliary policeman, but under a constitution which formally designated the colony as part of France, he was eligible for the metropolitan team. Like the tough defender Mustapha Zitouni, from Algiers, Rachid was a star, and a guaranteed pick for France.

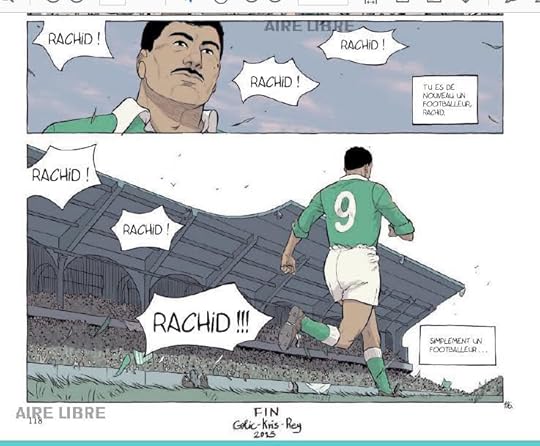

So it was a great shock when nine Algerian professional footballers playing in France disappeared in the night of April 13-14, 1958. ‘DISAPPEARANCE OF NINE ALGERIAN FOOTBALLERS (INCLUDING ZITOUNI)’, ran the headline on the front page of L’Équipe. The players, together with a few more recruits from home, set up based in Tunis, where they formed an Algerian national side avant la lettre, assembled by the National Liberation Front (FLN). They spent the next four years touring the non-aligned and anti-imperialist world, representing the nation-to-be in North Africa, the Middle East, China, Vietnam and the Soviet bloc. “I met people like Ho Chi Minh, people who made history,” Mekhloufi said later, “the Rachid of 1958 and 1962 were two completely different people.” The graphic novel, Un Maillot Pour l’Algérie, published last year (in French only, so far) tells the story of Rachid and his teammates.

As the brilliant English writer Joe Kennedy put it, “it would not be absurd to say that the world at large thinks of Algeria as not one, but two nations: the first an inscrutable, largely uninhabited North African republic characterized by governmental and religious instability, the second a deterritorialized, quasi-European entity existing sort-of amorphously within the political boundaries of France and increasingly separate from its geographical origin.” Naturally, Kennedy was writing about football – specifically, the prospects of the Algerian team in the World Cup of 2014 – but just as naturally, he was talking about so much more.

Political islamophobia has played a prominent role in the French presidential elections scheduled for tomorrow (and not only from Le Pen, for the record), but its object is mysteriously dislodged. The Muslim or Arab danger is both the third generation “Algerian” youth of the suburbs (whose grandparents came to work in the same factories that employed Abelhamid Kermali before he began playing for Mulhouse), and the desperate refugees dying in the Mediterranean. European neo-nationalist politics is born in this post-colonial neurosis.

The National Front’s taxonomy of citizenship is ordered in the light of this slippage, while the anger and venom at its heart were born in the defeat in Algeria. Before it implanted itself in the de-industrialised towns of the North and East, the Front’s strongest base was in mediterranean towns and cities like Béziers, where thousands of bitter pieds-noirs, (former colonists resident in Algeria) fled after the 1962 cease-fire. The current Mayor of Béziers, a FN fellow-traveller called Robert Ménard, was born in Oran. He refuses to mark the ceasfire of March 19, 1962 – “I don’t celebrate defeats” he has said – and renamed the local Rue de 19 Mars 1962 after an officer involved in the failed coup against De Gaulle of 1961. For Ménard the contemporary fight for “the resurrection of Europe” makes sense only in the light of his childhood in Algeria. “The past flows into the future.”

Though the story of Un Maillot Pour l’Algérie is ultimately one of triumph, the players suffered too. Though glad to serve the cause, they gave up friendships, relationships and promising careers. Prior to 1958 they had lived tangled lives of friendship and football in two continents and, (supposedly) one country. In one scene an argument breaks out as the team watch the World Cup on television and Zitouni celebrates Fontaine’s goals. “Hey Mustapha… one would think that it was you who won… remember where you are eh?” a teammate rebukes him. “So?” he snaps, “I’ve got the right to be happy for my friends, no?”

Zitouni, Mekhloufi and the rest of the FLN team were noteworthy in French league football in the 1950s, but they were not out of the ordinary. In 1957, the same year that Rachid helped Saint Étienne to a league title, Abdelhamid Bouchouk and Saïd Brahimi scored in the final to win the Coupe de France for Toulouse. One of Rachid’s teammates at Saint Étienne was the Cameroonian Eugène N’Jo Léa. Even the great (white) star Fontaine had been born in Marrakech: colony and metropole were well and truly entangled, in football as in everything else. The only possible humane way out of the present crisis of European racism lies in a recognition of this tangled history.

After the cease-fire, Rachid Mekhloufi returned to Saint Étienne, where he played until 1968, winning the league in 1964, 1967 and 1968. In his final game he scored both goals in a 2-1 win over Bordeaux which secured the club’s first ever league and cup double.

One of the strengths of the graphic novel medium is the way that authors and artists use its conventions to foreground decisive moments and central ideas. A character faces the front of the frame, or the picture is zoomed suddenly in or suddenly out, as if to underline a phrase or a line of dialogue. Before his first match, the coach warns him that the stadium is full of those who have come to see “A soldier, a traitor, a deserter. [Show them that] you are once again a footballer.” As the teams emerged, Rachid recounted later, the stands were totally silent.

In this match, depicted in the final pages of the book, Rachid goes on a run, past one, two, three players. “Shit, he’s even better than before”, a face in the crowd exclaims. He breaks in to the box, squares the ball, and his teammate finishes. The whole team mob Rachid. “Il est pour toi celui-la, Rachid! Il est pour toi!” the goal scorer shouts. The crowd chants, Ra – Chid, Ra – Chid, Ra – Chid.

May 5, 2017

Weekend Music Break No.105 –French presidential election edition

Paris, even though I’ve never lived there, has perhaps been more important in my formation as a DJ than any other city (ok maybe New York is tied). Its diverse immigrant communities have created a rich cultural mix, the impact of which has spread across the globe. For example, without France’s African communities, the global Afropop (Afrobeats) industry from Lagos to Johannesburg wouldn’t have the reach or aesthetic it touts today. Standing on the front lines of the global battle against European supremacy, and redefining what belonging means in the global North in general, I believe we all owe France’s immigrant communities a deep debt.

This playlist is dedicated to all my French immigrant whatever generation brothers and sisters living up and down the country. My thoughts and heart are with you this weekend.

Weekend Music Break No.105 – France election edition

Paris, even though I’ve never lived there, has perhaps been more important in my formation as a DJ than any other city (ok maybe New York is tied). Its diverse immigrant communities have created a rich cultural mix, the impact of which has spread across the globe. For example, without France’s African communities, the global Afropop (Afrobeats) industry from Lagos to Johannesburg wouldn’t have the reach or aesthetic it touts today. Standing on the front lines of the global battle against European supremacy, and redefining what belonging means in the global North in general, I believe we all owe France’s immigrant communities a deep debt.

This playlist is dedicated to all my French immigrant whatever generation brothers and sisters living up and down the country. My thoughts and heart are with you this weekend.

May 4, 2017

The Archive of Malian Photography

“Every unit of meaning, and not just every image, is a public crossroads of histories of interpretation.” This reflection comes from Paul Landau’s introduction to Images and Empire: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa (2002), but also applies to the images and the overall mission of the Archive of Malian Photography. By digitizing more than 100,000 images by Malian photographers, project director Candace Keller, a professor of African art history and visual culture at Michigan State University, hopes that the collection will “shape the way photographic history and cultural practice in West Africa are taught and studied since the concepts displayed go beyond what we’re used to seeing….” In pursuing these goals, the archive not only preserves an important element of Mali’s artistic past, but also shifts the interpretations possible at this particular historical crossroad.

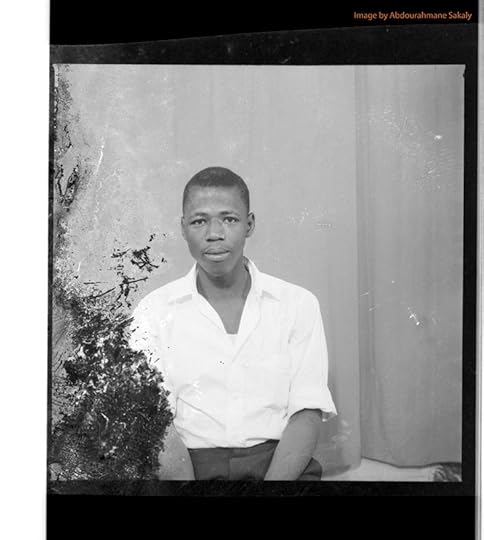

Mamadou Cissé. Ségu, Mali. Circa 1969 via Archive of Malian Photography.

Mamadou Cissé. Ségu, Mali. Circa 1969 via Archive of Malian Photography.In collaboration with the Maison Africaine de la Photographie in Bamako, Mali and MSU’s MATRIX: The Center for Digital Humanities and Social Science and funded by National Endowment for the Humanities and the British Library Endangered Archives Programme, the Archive of Malian Photography project has preserved photographs by five Malian photographers: , , , , and . Currently, users can explore about 28,000 photos taken by Cissé and Sakaly in Bamako, Mopti, and Ségu. These photographs depict the rich texture of Malian life, as Keller reflected in email correspondence with me.

“These collections house images of political leaders, religious figures, and pop-cultural icons. They also depict rural and urban practices. They capture voting procedures, weddings, birthday parties, horse racing, and other events. They reveal consistent and changing trends in dress hairstyle, and other forms of personal adornment as well as aesthetic and artistic values and innovations in portraiture, across five decades, in at least three different locations in Mali (Bamako, Ségu, Mopti),” Keller explained, “Therefore, the information they capture can inform historical, cultural, and political understanding across a variety of academic disciplines.”

In addition to preserving these photographs, Keller and her collaborators saw the project’s primary function is protecting the photographs. “The project is designed to address present conditions that render these archives and, by extension, the cultural heritage of Mali and the artistic legacies of the artists, vulnerable,” Keller explained to me via email, “These include harsh climactic conditions (heat, dust, flooding and humidity) and exploitation by unscrupulous agents in the international art market.”

The exploitation of West African photographers by international actors has been chronicled in Keller’s scholarship, most notably in her 2014 article for African Arts, “Framed and Hidden Histories: West African Photography from Local to Global Contexts.” Keller has found that since the 1990s, several negatives from private archives of photographers were removed and later appeared in print or digital format, with no compensation granted to the photographers or their families. With this in mind, the team made certain to protect the photographs at every stage of the process, ensuring that the negatives never leave Mali, that the photographers or members of their family are actively engaged in the selection process, and only providing access to low-resolution versions of the images on the site (the full terms of the Partnership Agreement are available in both English and French on the site).

Abdourahmane Sakaly. Bamako, Mali. February 1958 via Archive of Malian Photography.

Abdourahmane Sakaly. Bamako, Mali. February 1958 via Archive of Malian Photography.The implications of this project are broad and far-reaching. For Keller, this project helps to contextualize the work of Malick Sidibe, a photographer who is a major focus of her own research (Keller was previously featured in Africa is a Country following the death of Sidibe in April 2016). In preserving the work of not only Sidibe but his predecessors and contemporaries, the Archive of Malian Photography aids in contextualizing what Keller refers to as the “narrow ‘canon’ of [Malick Sidibe’s] oeuvre.”

Furthermore, this project provides new vistas on Mali’s past, opening up photographic collections that might otherwise have been lost to the ravages of climate and time, while also expanding our perspective on Mali’s past.

Follow MATRIX on Twitter for updates on the Archive of Malian Photography. Feel free to send me suggestions via Twitter (or use the hashtag #DigitalArchive) of sites you might like to see covered in future editions of The Digital Archive!

May 3, 2017

The African Union is now complete, but at what cost?

At the end of January this year, Morocco was readmitted to the African Union, after spending 33 years on the “outside.” Morocco left the Organization of African Unity in 1984 due to the organization’s recognition of Western Sahara’s sovereignty by admitting a delegation claiming to represent the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) as its 51st member two years earlier. Morocco’s readmission is important because it calls into question the AU’s political stance and its apparent commitment to ensuring the sovereignty of all members.

The AU has faced its fair share of challenges since its formal establishment in 2001. Its lax membership requirements, a remnant of its OAU legacy from the early 1960s, resulted in an organization of 53 countries, (54 with South Sudan’s admission in 2011), that was not entirely certain as to how to define itself or adhere to the principles it purported to embody. However, these lax membership requirements seemingly had their limits. The admission of the SADR was effected despite Morocco seeking claim to this territory, a site of contention for more than a decade between the Polisario Front, which represents the indigenous Saharawi people, and Morocco. Consequently, Morocco decided to leave the organization. In doing so, it became the only African country to not be a member of the African Union.

Not surprisingly, Morocco realized that it is better to be part of the club than out of it and began to petition for readmission in 2016. The petition came with the request that the AU cease to recognize the “phantom state” of Western Sahara as Morocco considers it to be an important part of its kingdom. Nevertheless, this “phantom state” is a member of the AU, and there is the expectation that the right to sovereignty of member states be upheld, which led to disagreements on the part of several countries.

There were those that supported Morocco’s return and those that remained critical of its refusal to recognize Western Sahara’s right to self-determination. Yet, despite reservations on this matter, Morocco was readmitted with 39 members voting in support. Those in support of Morocco’s return to the AU argue that it was a choice between “unity and harmony,” but one can not ignore its increasing financial presence on the continent, especially in West Africa. This positioning led to a fierce reaction on the part of President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe who, despite ruling the country for 37 years, being accused of several human rights violations, and his wife stating that the party would field him for president in 2018 “as a corpse”, chastised the organization for its lack of ideology and how easily it was influenced by financial incentives.

Although Morocco is the fifth largest economy in Africa and may help fill the financial void left by Muammar Gaddafi, the AU appears to have sacrificed its own principles and morality to secure its finances. Mugabe’s challenge calls into the question the AU’s position on a number of issue; positions that have not always been clear due to outgoing chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s seeming lack of direction for the organization in recent years. (Her critics suggest she used her time there to organize a stealth campaign, now in full swing back home, to become South Africa’s next president in 2019 when her former husband’s two terms expires.) South Sudan and the current violent conflict that it faces is one example of the inaction on the part of key international and regional actors, that has left the AU in charge of addressing this large-scale humanitarian challenge, with the possibility of it serving as a trustee for the young nation. Still, the question of whether the AU should lead a country and its capacity to do so remains a concern.

Furthermore, the AU’s inability to address some of these political concerns has allowed the smaller regional blocs to wage an attack against the existence of a continental body given the differing levels of political development across the continent. This was evidenced, for example, by the support given to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) for its ability to navigate the recent political tension in Gambia and committing to limiting the space for a dictator like Yahya Jammeh to survive. What will this lack of direction mean in addressing issues related to South Sudan, or the violence perpetrated by French soldiers in the Central African Republic (CAR)? What does it mean for the AU’s role on the continent?

There is no doubt that the AU has the potential to be an important political actor but it faces severe limitations as a continental body. In order to establish itself and successfully address the current issues, the AU needs to critically reevaluate itself and what it aims to achieve as an organization. It needs to take a firmer stance on Morocco’s position in the organization if it is truly committed to preserving Western Sahara’s right to self-determination. Morocco’s seeming disregard for finding a solution was evidenced by its absence at the Peace and Security Council (PSC) meeting held to discuss the issue. While the PSC voiced its concern at this meeting, no enforcement mechanism was put in place. Another area to be addressed is ensuring that source of funding does not dictate behavior. The AU must be able to use its funds in accordance with its mandate in spite of who the key financiers are. Member countries are signatories to the AU Constitutive Act and should not be at the mercy of the more financially viable states. If the AU is unable to address these internal contradictions, then its continued and, potentially debilitating, identity crisis will only worsen.

May 2, 2017

The Indian-African alliance

Author Vik Sohonie and friends in Somalia.

Author Vik Sohonie and friends in Somalia.There has been a healthy response of anger in the wake of unjustified, brutal attacks against African nationals — particularly students — in recent days in India. Indian racism against black Africans is not a new phenomena, and such hatred is deeply embedded into the Indian psyche since the days of colonialism, when the British Empire’s classic strategy of divide and rule placed Indians as indentured servants, one artificial level above enslaved Africans. However meager the distinction, the damage was done, leaving a chilling legacy that plays out until today. Africa Is A Country has previously documented India’s hostile nature towards Africans.

Why do I say brethren? Because in all the analysis and outrage, little attention is given to how Indians are viewed and treated not only on the African continent, but by peoples of African descent across the world, whether in the Caribbean, South America or the United States.

I was born in India, grew up in Thailand, Singapore and the Philippines, with academic and working stints in the United States, Germany, Haiti and across the African continent. I run a music label dedicated to African music. As an Indian, I see my mission not only as disseminating the magnificent music cultures of Africa that rarely get international exposure, but also connecting India and Africa through forgotten cultural ties in a way that all the burgeoning bilateral trade deals simply cannot.

From my experience, Indians are respected and often adored across Africa. Our merchants and traders, particularly from the Gujarati coast, have long been welcomed to East Africa’s shores. The pre-European Indian Ocean economy saw a kinship between the peoples of the subcontinent and particularly the people of the Somali and Swahili coast. Our cuisine, language, dress and music profoundly influenced many African cultures.

In my travels to Ghana, I was afforded curious attention by Ghanaian women who reminded me that Indians are considered icons of beauty. In Sudan, revealing my Indian origin elicited smiles from everyone — immigration officials to the tea lady on the street. “You are always welcome in Sudan,” the customs agent told me at Khartoum airport as I departed. The same words were spoken by the immigration office in Mogadishu, Somalia.

In Somalia, where Indian music inspired generations of Somali musicians and Hindi words pepper the Somali tongue, I was often told “You are our brother.” Somalis, like so many Africans, received their degrees in New Delhi and Hyderabad. They used those skills to build their country before the civil war of 1991 decimated it. My music label’s latest project focuses on Somali music before the civil war, an innovative period that drew greatly from Somalia’s infatuation with Indian cinema.

In Djibouti, where French is spoken, telling people I was Indian was met with a heartwarming response: “Les Indiens sont un grand peuple (Indians are a grand people).” Having faced overt and latent racism for most of my life, particularly in Southeast Asia, where the common tropes of being unclean and sexually deviant were leveled with tiresome frequency, hearing how Djiboutiennes held us in such high regard came as a positive surprise. Finally, Uganda, which has a tempestuous relationship with South Asians thanks to the antics of Idi Amin, holds as its national dish the ever-present “Rolex” — a chapati roll filled with egg, avocados, cabbage and chilies. The US dollar might be the global reserve currency, but Indian food in many countries in Africa is without doubt the reserve cuisine.

My travels to Africa made me proud to be Indian, while most of my youth was spent lamenting the fact, thanks to anti-Indian racism. And the reverse is also true. In New York, as a graduate student, I visited an exhibition in Harlem on the African presence in India. The artwork told a story of Africans forging their way within various civilizations on the subcontinent. Ethiopian traders like Malik Ambar advanced to positions of great authority.

Harlem was an apt location to host this exhibition. In the book, Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America, writer Vivek Bald reveals how Indians fleeing British ships found sanctuary in the northern Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem amongst black Americans. Our food and music intermingled with the soul food cuisine and jazz culture of the time. The Harlem Renaissance welcomed Indian influences. Intermarriage became common.

This mirrored my experience in the United States. Despite attending American schools in Asia, my multicultural upbringing made finding a clique in university challenging. Yet it was the students from the Caribbean, Nigeria and Ghana who took me in. We shared similar values, a compatible sense of humor, a love for spicy food, and of course, football. Many Indian students, uncomfortable with their new American surroundings, found solace in Afro-Caribbean and African student communities, where an unknown but very real fraternal bond existed.

Indeed India and Africa’s trade ties grow greater by the day. Airtel dominates the mobile sector in much of the continent. Indian banks like Bank of Baroda can readily be found in financially liberalized African economies with shared legacies of British rule. The Indian presence and experience in Africa is ancient and welcomed. Visas are not a hinderance. I have never traveled elsewhere in the world where my Indian passport is a marker of respect rather than a guarantor of scrutiny — not even the countries I once called home.

India might still get the raw end of the deal in the ever-so problematic worldview of powerful western media outlets, but in the forums of the Global South, India remains a respected leader. But it seems India’s role in the world and how it views itself has changed dramatically, and that has had a direct impact on how Indians view time-honored friendships and those that share a similar history of colonial rule and exploitation. The alliance of Hindu nationalism and neoliberal capitalism has moved India further away from its role as a vanguard of the dispossessed and displaced, to be a convenient ally of western power. In doing so, its historic ties with Africa have been replaced with solely a desire for profit, rather than continuous exchanges of solidarity.

African diplomats and governments have every right to threaten downgrading ties if Indians continue to treat people they should regard as their kin as subhuman targets of national frustration. More so than our neighbors to the east, who do not welcome us as Vedic brothers and sisters, or our neighbors to the west, who see our bodies as disposable labor, Africans are our closest natural allies in the world — more so than the United States, certainly more so than the government of Israel (India is the largest importer of Israeli arms). If we fail to realize this and continue our brutal ways against their most studious and ambitious, we risk losing our place in the world, alienating those that who hold us in high esteem, and dismantling a relationship forged over millennia. We must decolonize our minds to truly assume the leadership role we want — and deserve — in the modern world. That begins by welcoming and treating Africans in India the way Indians are welcome and treated in Africa.

May 1, 2017

The Spirit of Marikana

Lonmin mine workers in Marikana listening to a speech by President Jacob Zuma after the shooting deaths of their colleagues. Image via Government of South Africa Flickr.

Lonmin mine workers in Marikana listening to a speech by President Jacob Zuma after the shooting deaths of their colleagues. Image via Government of South Africa Flickr.The Marikana Massacre on August 16th, 2012 witnessed the killing of thirty-four black mineworkers by South African police. This was the most potent episode of state violence inflicted upon civilians since the Soweto Uprising of June 1976 – like Soweto, Marikana has been referred to as a turning point in the history of the country.

As we argue in our new book, this time it was not a major township in the country, Soweto, which had erupted but South Africa’s platinum belt which holds more than 80% of the world’s platinum. Platinum mineworkers were on a militant strike, demanding more than double their salaries at Lonmin, the third largest platinum mine in the world. The dominant story in mainstream media as well as scholarship has understandably tended to focus on this single event, the Marikana Massacre, painting a sad story of black mineworkers who were objects of police brutality. In our research, we aim to provide an alternative perspective, one that first and foremost describes the mineworkers as active agents who sought to control their own destinies in the midst of plutocratic mine-owners and their “pocket trade union’s” (the National Union of Mineworkers) opposition.

While undertaking research for the book, we created long-term relationships with mineworkers who were at the forefront of their movement. In order to write heroic figures back into the history of working class organizing and militancy in South Africa and beyond, we used mineworkers’ actual names in the book so that generations from now, readers and the public may know that these were real people, with real dreams and hopes who risked their lives for basic dignity and economic freedom. Siphiwe Mbatha, a socialist civic organizer turned ethnographer, and I had arrived two days after the massacre to begin to uncover the origins and historical development of the movement. While at first it was only possible to learn about the massacre itself (given the urgency), over the next two years we were able to trace the now infamous “living wage” demand of R12,500 (equivalent to approximately USD$1000 at the time) per month back to a discussion between two workers in the changing rooms at one mine (in one specific shaft at Lonmin called Karee) in June 2012, to the moment of the massacre, and the culmination of the longest strike in South African mining history in 2014. We show how the massacre had the counter-intuitive effect of uniting rather than silencing the new found resistance.

Within the approximately two-year period that the book deals with, we also provide one of the first detailed histories of the then upstart Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) which workers continued to join en mass from 2012 until 2013 when the union gained official recognition at South Africa’s major platinum mines. The book looks at the formation of independent worker committees which were elected by mineworkers at each of the platinum mines and highlights that the most strident “organic intellectuals” among these refused to simply be absorbed into AMCU’s trade union bureaucracy. The radical democratic culture of the worker committees were, for a time, carried forward into, and forced upon, AMCU.

The first detailed ethnography of this movement also offers broader insight into South Africa’s contemporary political scene. It tells the hidden story of the context in which Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party was formed and the ways in which it fueled the fire against ANC President Jacob Zuma and the ruling party itself. It offers a lens through which to understand the continued decline of the ANC, which still has blood on its hands from the Marikana massacre – with some arguing that the massacre can be traced back to Zuma himself. As we highlight in the book, Zuma lambasted the strikes in the platinum belt, and at different points in time publicly blamed the strikers for the deaths of thirty-four of their fellows on August 16th.

As the protests continue to unfold across the country, it is important to note that the idea of #ZumaMustFall in fact emerged most forcefully amongst platinum mineworkers who blamed the ANC and its leaders (especially Zuma and Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa) for the brutal assault that was inflicted upon them. The history of the social movement also brings to light that having good negotiators, government leaders or members in parliament did not bring a victory to the working class. Our research is not about the ways in which gifts are bestowed by elites or leaders upon the oppressed. Instead, it is about how ordinary people took control over their lives. In the process of self-emancipation they became makers of their own history and shapers of the South African political landscape.

April 28, 2017

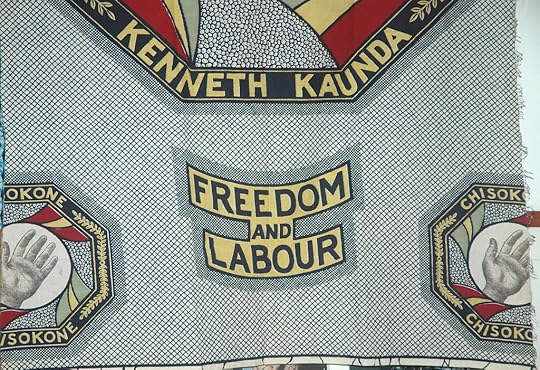

Kenneth Kaunda and the national question

Staatsbesuch Sambia, President Kenneth D. Kaunda and Farbwerke Hoechst. Image via Wikimedia.

Staatsbesuch Sambia, President Kenneth D. Kaunda and Farbwerke Hoechst. Image via Wikimedia.As he attains the young age of 93, Zambia’s first President Kenneth Kaunda (KK to his supporters), has lived to see five of his successors have a go at leading the country. When he lost the 1991 presidential elections to Fredrick Chiluba, he witnessed what must have been a heart wrenching campaign of vandalisms designed to dismantle his legacy and remove from collective memory the 27 years of his rule. In actual fact it was nothing of the sort. The Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD) and its foreign investor partners implemented a well concerted asset stripping strategy that was as devastating as it was ruthless. The deindustrialization, mass unemployment and even population decline that followed have already been studied. The point is that after 26 years of the post-KK administration, we can now make a fair comparison of the 27 years of KK’s First and Second Republics and ask whether indeed the neoliberal MMD was better than the socialist oriented United National Independence Party (UNIP).

Here I want to focus on the national question and the state of affairs in the social, political and cultural matters of state to evaluate the KK legacy. To cut to the chase, it seems that “the Third Wave of Democratization” in Africa was followed by a new scramble for its natural resources. The nationalism of the anti-colonial movement of KK and his generation has now given way to the tribalism (identity politics in globalization-speak) of the comprador oligarchs, those who profited from the privatization of state owned enterprises and those whose very existence is tied to foreign companies. As is well known, comprador means anti-national and these are the forces that Kaunda defeated in 1964, 1968 and in the coup attempts that were concocted to unseat him in the name of democratization.

The national motto on Zambia’s coat of arms is One Zambia, One Nation. But because of the passion with which KK used the slogan in public, it has come to be associated with his name. What exactly does it mean – One Zambia One Nation? It is not just a slogan, it is actually an attitude of mind, if not a way of life, a political culture if you like. One cannot belong to a nation whilst working against it and working against fellow citizens. For KK One Zambia One nation meant holding the country together and uniting behind the cause of national liberation: Thus to One Zambia, One nation, he always added –One Africa, One Revolution.

What he gave to Zambian children he also gave to Angolan, Mozambican and Zimbabwean children, what the state provided for the children of the rich the state also gave to the children of the poor, equal opportunity to sit in a classroom and learn life skills that would enable them to serve their country and people across Africa. So those who have dismantled KK’s legacy have thrown the children out of the classroom and their parents out of the factory into the street. They have promoted tribalism and sold themselves to the Foreign Investors, sometimes not even the highest bidder for their souls.

When Kaunda became Zambia’s first president in 1964, the neighboring Congo was already in a crisis of Cold War proportions. Like Zambia, the DRC was also a copper and cobalt mining economy and international forces were propping up the secession of Katanga under Moise Tshombe, threatening to dismember the country. The tragic war that engulfed the new Republic culminating in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba has to this day continued to haunt the Congo and its neighbors with the country still being pulled in different directions and still the playground of foreign capital. For KK One Zambia, One nation meant doing everything possible to prevent a Congo disaster in Zambia and that we can safely say, Kaunda achieved, against all odds.

During the first ten years of KK’s administration, Zambia recorded massive growth in infrastructure development. What is notable is that whereas British colonial development strategy was to focus investments in the towns along the rail line from Livingstone to the Copperbelt, KK directed state funds to the construction of new schools, clinics and hospitals and agricultural extension centers in all the districts. Although the urban bias persisted as it must on purely economic reasons, there was no rural district that did not get its share of government investments.

So how did all this unravel in 1991? First and foremost the Zambian economy was ‘singing’ much like the way it is singing in Venezuela today. Blame mismanagement but also blame the real cost of equitable public investments. There are no shortages in a survival of the fittest free market because those who cannot afford the electricity, garbage collection, local bread or imported fruit simply go without it. In a socialist oriented economy where goods and services are provided according to need and therefore subsidized by the state, there are always shortages. And so the people get tired of the queues and the cheap quality and the lack of choice. To be fair, the state does tend to become authoritarian as well and people do have a right to demand change but when you throw away the local textiles and local beverages to make way for the higher quality imports, you had better be prepared to lose jobs, incomes and livelihoods in those industries.

Kaunda’s successors have all tried to hold the nation together but they have not all believed in the project of African liberation which is so central to the attainment of economic freedom. They have tried to attain development as directed by Foreign Investors but found themselves lacking the imagination, the capital, the ability, nay, the freedom to bring this to fruition. As the Chinese have demonstrated, it is not the IMF, the World Bank or Goldman Sachs that made the Four Modernizations possible, it was a Chinese plan.

It is not too late to rediscover our African unity and defeat the xenophobia inherent in the identity politics of Trump, Le Pen, May and all those African followers that refuse to be their brothers’ keepers but arrogantly claim to put their country first when clearly what they mean is their billionaire deals first.

For us in the still much oppressed Africa, we must not forget that KK not only preached unity for Zambia but also said One Africa, One Revolution. In fact our freedom and our unity (Uhuru na Umoja as the Tanzanian national motto says) are inextricably connected. Unless one has a Pan-African view of the world, and unless one has a liberation ideology, their identity politics can only be exclusionary, xenophobic and essentially an illusion.

One Zambia, One Nation therefore must become an emancipatory slogan again. It must be driven by a sense of community and it must unite society behind the common goal for humanity: a better life for all.

Lessons from Kaundanomics

A story is told that a few years after independence in 1964, Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s first president, visited one of the mines in the mineral rich Copperbelt Province and was immediately struck by the complete absence of Zambians in senior management positions. He proceeded to ask the mine owners as to when they reasonably thought Zambians would be ready to occupy positions of influence within the country’s mining sector. With straight faces, the mine owners responded “not before 2003, Mr. President.”

Following independence from Britain, Zambia’s economy was organized broadly along capitalist free market lines. The economy, split up into mining and non-mining sectors, was wholly in the hands of foreign private interests. The copper mines, the country’s jewels, were owned a 100% by Anglo American Corporation and American Metal Climax. Both companies having obtained the rights to mine copper in perpetuity from Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company (Rhodes had himself obtained the mining rights under dubious circumstances). The non-mining sector – including banks, insurance companies, construction companies and so on – were similarly in the hands of foreign interests.

The logic, or at least hope, in organizing the economy in this way was that unfettered foreign capital would not only drive productivity improvements at home, including knowledge and technological transfers, but would, crucially, play a big role in meeting the newly independent country’s social expenditure targets. The latter point was of vital importance given that the colonial government had disproportionately privileged whites in the provision of social services.

Unsurprisingly, unfettered foreign capital did the exact opposite. Instead of re-investing a considerable proportion of their profits in local operations, the mining companies externalized almost everything. Before independence, mining companies had re-invested about 50% of their profits in Zambian operations. After independence, the rate of re-investment fell to about 20%, according to estimates by Oliver Saasa, a Zambian development expert.

Things were not any better in the non-mining sector. Saasa estimates that the outward remittance of dividends to foreign owners increased by 84% in 1966, two years after independence. As for the commercial banks, they continued just as before to favor resident Europeans in the provision of credit facilities. Only 15% of bank credit was extended to Zambian citizens, a move that constrained the emergence of an indigenous entrepreneurial class. In as far as funding the state purse was concerned, the mining and non-mining companies utilized all manner of gimmicks, including “invisible costs,” to ensure that their tax liabilities in Zambia were kept to a bare minimum.

It very early on dawned on Kaunda and his team that “the encouragement of private investment inevitably meant the promotion of the dominance of foreign enterprises in the productive sectors of [Zambia’s] economy.” Rather than be engaged in a never-ending game of dubious logic with the foreign capitalists, Kaunda decided to act.

On 19th April 1968, he announced the Mulungushi Reforms and ordered that the state would henceforth take a controlling position in all private retail, transport and manufacturing firms in the country. In the following year, at a community meeting in the historic township of Matero, Kaunda announced a partial nationalization of the country’s mines.

80% of the economy was now in the hands of the state. A process of realigning the objectives of enterprise with those of the country was immediately set into motion. The copper mines were to fund a generous “cradle to the grave” welfare system that would reverberate beyond the Copperbelt and benefit everybody. Within a decade of the reforms, Zambians were occupying leadership positions in the economy putting to shame the dire predictions made in the 1960s. More importantly, free education and free healthcare for all with guaranteed social mobility became the mantra by which the country was to live by.

In 1991, Kenneth Kaunda graciously exited from office after losing that year’s elections. The new government, intoxicated by the fumes of neoliberalism then sweeping the globe, embarked on an ambitious privatization program whose coup de grâce was the re-transfer of the mines to foreign private interests.

Immediately afterwards, unemployment and destitution, particularly on the Copperbelt, became the order of the day. Access to quality social services, once guaranteed to all, were now the preserve of a tiny elite. A schism ran right through the country forming class cleavages wherever it went.

In our hurry to get rid of Kaunda, we had also gotten rid of Kaundanomics and we therefore lost our way.

April 26, 2017

How France will eat itself

Still from Matheiu Kassovitz’ La Haine (1995).

Still from Matheiu Kassovitz’ La Haine (1995).The film La Haine became an instant classic on its release in 1995 for its livid account of police abuse as a structural form of violence in France. The film remains a poignant depiction of the lingering problem of police brutality in the banlieues (suburbs) of Paris, where most of the city’s poorer African- and Arab-descended populations live. The film’s 24-hour narrative follows the daily lives of three young Parisians, Vinz, Said, and Hubert, after one of their friends, Abdel Ichaha, is brutalized by the police and rendered comatose. Mathieu Kassovitz, the director, was inspired by the true events of the death in police custody of a young French-Zairian, Makome M’Bowole, in 1993. M’Bowole was handcuffed to a radiator and shot at point blank range.

Twenty-two years later, on Feb. 2, 2017, at 5 pm, in Aulnay-sous-Bois, a mutli-ethnic suburb in north-west of Paris, Théodore L, alias Théo, a 22-year-old French-Congolese community worker, feared for his life when a group of four policemen brutally sodomized him. He recalls that he was on his way to see one of his friends when he found himself face to face with the officers from la brigade spécialisée de terrain (BST – a special unit dedicated to field policing in impoverished urban zones) who were routinely checking identity papers during a stop-and-frisk. While Paris police say alleged rape was an “accident,” Theo suffered severe anal injuries and was diagnosed with a 10cm deep anal tear.

Theo’s rape joins a long list of similar cases of police brutality directed at the French youth of African descent. On October 18, 1980, Lahouari Ben Mohamed, a 17-year-old boy, was shot in the head by a policeman during a stop-and-search operation in Marseille. On December 6, 1986, Malik Oussekine died a day after he was physically brutalized by two plainclothes policemen in Paris. Between November 5-29, 1991, Ahmed Selmouni was physically and sexually abused during his arrest in Seine-Saint-Denis, a suburb in the northeast of Paris. On October 27, 2005, Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, 17 and 15 years respectively, were electrocuted in the Paris suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois after police chased them as they were their way home from a football match. Their death led to the outbreak of the urban riots of 2005.

Eleven year after those riots, which marked a turning point in French modern history, police brutality continues to mediate the relationship between French citizens of African descent and public and political institutions. Their conditions continue to worsen.

On July 19, 2016, Adama Traoré, a 24-year-old French-Malian, was found dead in police custody in Beaumont-sur-Oise, a small town north of Paris. The unexplained circumstances of his death have been linked to serious allegations of a state cover-up and show how the problematic dimension of police brutality in France underscores issues of race and violence that have always shaped French politics. Not only did the local prosecutor falsely declare Traoré’s death to be as a result of a heart attack and a serious blood infection, but also his mother and brother were gassed by the police and the mayor of Beaumont threatened to sue his older sister. Later the same year, two of Adama’s brothers were sentenced to eight- and three-month prison terms in prison, respectively, for threats and violence toward officers.

The ensuing public and media attention following the wide reporting of Theo’s case showed the extent to which the issue of police brutality is a systemic problem.

In an interview on a French talk show, Luc Poignant, a veteran police officer and a spokesperson of a police union, deemed the use of the racial slur “Bamboula” as acceptable when addressing African men. The term is highly-pejorative translating “player of drums” or “dancing N-word.” It was used to described African soldiers in colonial French wars and refers to their perceived naivety, cannibalism, and brutal primitivism.

The attention to the complex relations between French media, the political caste and French people of African descent in Kassovitz’s film still resonates in today. In 1995, the prime minister Alain Juppe set up a compulsory screening for his cabinet. After the 2005 urban riots, the now famous Kassovitz-Sarkozy exchange captured public attention and generated heated debate over police brutality, the role of the politicians and the alienation of minority populations. Kassovitz went further to call Sarkozy, the interior minister at that time, an “irresponsible” politician, comparing him to “a starlet from American Idol” who acted “like a warmonger.”

As Marine Le Pen is likely, I think, to be France’s next president, the looming threat of more violent bloodier urban riots in the wake of other events of police brutality is a reality. She is unapologetically racist, xenophobic, intolerant politician who feeds on problems of unemployment and fragmented multiculturalism to make neofascism mainstream again. The far-right leader ended her campaign by vowing to suspend all legal immigration to France which would save her country from “savage globalization” by putting “native French first.” When asked her opinion about Théo’s incident, she insisted on backing the police unconditionally. She called protesters against police violence “scum.”

La Haine ends with the tragical scene of shocking violence where Hubert, the rational figure in the movie, uses Vinz’s .44 magnum revolver to avenge the death of the latter by a policeman. As the closing credits roll, we hear Hubert’s voice retells the old story of a person that, while falling from a fifty-story building, keeps reassuring himself by repeating “So far so good … so far so good … so far so good.” The election of France’s next president will not only risk shuttering the dreams of social cohesion but it will widen the already explosive political and social gap.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers