Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 286

March 22, 2017

French elections and France’s colonial war in Algeria: What’s in an apology?

In a recent interview on a private Algerian TV news station, French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron called France’s colonial history an act of barbarism and a crime against humanity; if elected head of state, he would issue an official apology to all victims of colonialism. With this condemnation and promise, coming already more than half a century after the independence movements that marked the end of the old colonial project, Macron, the leader and founder of the progressive En Marche! party and current front-runner in what has proven a turbulent race, has rekindled a divisive debate in France ahead of the first round of voting on April 23.

Polling suggests that the country is almost evenly split in its opinion of colonialism (those who agree with Macron have a very slight edge over those who disagree). From across the political spectrum his comments have elicited strong reactions, although, predictably, the sharpest criticism has come from the right.

Marine Le Pen — Macron’s main competitor and candidate for the right-wing Front National and for whom colonialism rather perversely represents the positive sharing of French values — responded by accusing him of disloyalty to France. Le Pen’s response is in keeping with the nationalist rhetoric that she has used to great effect throughout her political career and especially during this presidential race, which has come in the wake of a series of extremist attacks in the country. Indeed, her reaction reveals a disturbing tendency in France: because of the history of atrocities committed by the French government and its citizens, the strong tradition of French Republican pride, which rests on equality and universal human rights, requires a second, twin tradition of amnesia and revisionism in order for it to appear unsullied. One might recall that former president François Mitterrand maintained that he would “not apologize in the name of France” for Vichy’s complicity with the Nazi government. It was Jacques Chirac who issued a full apology in 1995, half a century after the Holocaust.

In Algeria, Macron’s condemnation of colonial violence was met with approval by several public figures and political leaders. Algerian politicians, for whom such a statement is long overdue, are largely bitter about the issue of an apology for colonialism: for the French government to choose not to recognize the torture, rape, killing, seizure of property, and assault on dignity suffered by Algerians at its hands amounts to arrogance and callousness. Admitting that these atrocities were committed under colonialism and during the Algerian struggle for independence, would bring necessary closure.

Despite the two clear, opposed stances on colonialism that Macron’s comments appear to have dusted off and presented anew, the relationship between Algeria and France is both antagonistic and intimate, the site of quite a few knots and gray areas. For instance, although France began its nuclear tests at the time of the Algerian War of Independence in the colony’s desert south, it was the Algerian independence movement and current ruling party, the Front de Libération Nationale, that later allowed the bulk of French nuclear testing to continue after independence by granting the French government access to the Sahara during the annexes secrètes of the Evian Accords — hence the FLN government’s silence regarding the thousands that suffer from the released radiation to this day.

A history of cooperation between the governments of both countries makes the potential consequences of Macron’s would-be apology difficult to disentangle. Already, without an apology, the two countries have a strong symbiotic trade relationship — though China has come to surpass France as Algeria’s primary trading partner. And as Macron mentions in the interview, as it is, both countries cooperate heavily on counterterrorism efforts.

Of course, this is not to discount the symbolism of an apology. To be sure, France is not the only country to glaze over its brutal colonial past; if Macron were to be elected and issue an official apology to France’s former colonies, it could set a precedent for other European states and pave the way for reparations. Such an apology might also serve to humble those who are quick to promote the French self-image of liberté, égalité, fraternité, doubtless a noble credo, but one that is often mobilized along the fault lines of the old colonial imagination to distinguish a just France from its corrupt and unstable former colonies. However, in an already divisive political climate exacerbated by Islamophobia, in light of the recent attacks in France, such an apology could also lead to further entrenchment into progressive and nationalist camps. Nevertheless, for French citizens of Algerian or other African descent, an admission of the destructive nature of colonialism would amount to an initial recognition by the French state of the phenomenon that underpins the structural racism they encounter in their daily lives.

However, Macron’s comments also invite former French colonies to consider their own national memories. In Algeria especially, there is a certain paradox in the fact that national identity has been so strongly constructed in opposition to the colonial power that delineated it as a coherent territory. In some sense, Algeria, the “country of a million martyrs,” has depended on the image of a colonial France in order to create a unified national memory across its vast geographic and cultural expanse; this is especially true of the FLN, whose legitimacy is bound up in the struggle for independence against the French. Of course, an apology would be welcomed by the Algerian government, but an unresolved debate with France on the effects of French colonialism has been able to serve as an end in itself.

What’s in an apology?

In a recent interview on a private Algerian TV news station, French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron called France’s colonial history an act of barbarism and a crime against humanity; if elected head of state, he would issue an official apology to all victims of colonialism. With this condemnation and promise, coming already more than half a century after the independence movements that marked the end of the old colonial project, Macron, the leader and founder of the progressive En Marche! party and current front-runner in what has proven a turbulent race, has rekindled a divisive debate in France ahead of the first round of voting on April 23.

Polling suggests that the country is almost evenly split in its opinion of colonialism (those who agree with Macron have a very slight edge over those who disagree). From across the political spectrum his comments have elicited strong reactions, although, predictably, the sharpest criticism has come from the right.

Marine Le Pen — Macron’s main competitor and candidate for the right-wing Front National and for whom colonialism rather perversely represents the positive sharing of French values — responded by accusing him of disloyalty to France. Le Pen’s response is in keeping with the nationalist rhetoric that she has used to great effect throughout her political career and especially during this presidential race, which has come in the wake of a series of extremist attacks in the country. Indeed, her reaction reveals a disturbing tendency in France: because of the history of atrocities committed by the French government and its citizens, the strong tradition of French Republican pride, which rests on equality and universal human rights, requires a second, twin tradition of amnesia and revisionism in order for it to appear unsullied. One might recall that former president François Mitterrand maintained that he would “not apologize in the name of France” for Vichy’s complicity with the Nazi government. It was Jacques Chirac who issued a full apology in 1995, half a century after the Holocaust.

In Algeria, Macron’s condemnation of colonial violence was met with approval by several public figures and political leaders. Algerian politicians, for whom such a statement is long overdue, are largely bitter about the issue of an apology for colonialism: for the French government to choose not to recognize the torture, rape, killing, seizure of property, and assault on dignity suffered by Algerians at its hands amounts to arrogance and callousness. Admitting that these atrocities were committed under colonialism and during the Algerian struggle for independence, would bring necessary closure.

Despite the two clear, opposed stances on colonialism that Macron’s comments appear to have dusted off and presented anew, the relationship between Algeria and France is both antagonistic and intimate, the site of quite a few knots and gray areas. For instance, although France began its nuclear tests at the time of the Algerian War of Independence in the colony’s desert south, it was the Algerian independence movement and current ruling party, the Front de Libération Nationale, that later allowed the bulk of French nuclear testing to continue after independence by granting the French government access to the Sahara during the annexes secrètes of the Evian Accords — hence the FLN government’s silence regarding the thousands that suffer from the released radiation to this day.

A history of cooperation between the governments of both countries makes the potential consequences of Macron’s would-be apology difficult to disentangle. Already, without an apology, the two countries have a strong symbiotic trade relationship — though China has come to surpass France as Algeria’s primary trading partner. And as Macron mentions in the interview, as it is, both countries cooperate heavily on counterterrorism efforts.

Of course, this is not to discount the symbolism of an apology. To be sure, France is not the only country to glaze over its brutal colonial past; if Macron were to be elected and issue an official apology to France’s former colonies, it could set a precedent for other European states and pave the way for reparations. Such an apology might also serve to humble those who are quick to promote the French self-image of liberté, égalité, fraternité, doubtless a noble credo, but one that is often mobilized along the fault lines of the old colonial imagination to distinguish a just France from its corrupt and unstable former colonies. However, in an already divisive political climate exacerbated by Islamophobia, in light of the recent attacks in France, such an apology could also lead to further entrenchment into progressive and nationalist camps. Nevertheless, for French citizens of Algerian or other African descent, an admission of the destructive nature of colonialism would amount to an initial recognition by the French state of the phenomenon that underpins the structural racism they encounter in their daily lives.

However, Macron’s comments also invite former French colonies to consider their own national memories. In Algeria especially, there is a certain paradox in the fact that national identity has been so strongly constructed in opposition to the colonial power that delineated it as a coherent territory. In some sense, Algeria, the “country of a million martyrs,” has depended on the image of a colonial France in order to create a unified national memory across its vast geographic and cultural expanse; this is especially true of the FLN, whose legitimacy is bound up in the struggle for independence against the French. Of course, an apology would be welcomed by the Algerian government, but an unresolved debate with France on the effects of French colonialism has been able to serve as an end in itself.

March 21, 2017

The unfinished business between Cameroon and France

In January this year, Cameroonian President Paul Biya (in office since 1982), cut off the southwest and northwest regions of the country’s access to the internet to punish anglophone Cameroonians for protesting their linguistic, political and economic marginalization. The UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression, David Kaye, called the move a violation of the right to freedom of expression. The executive committee of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences issued a statement about the situation in Cameroon and to support the UN Special Rapporteurs’ calls on the government to “investigate the deployment of violence against protestors and to exercise greater restraint in policing.”

For those familiar with Cameroonian decolonization, the internet suppression reminded of an earlier time: symptomatic of a violent method of administration forged during Cameroon’s transition to “independence,” by France and “moderate” local elites.

A new book that tells that story of decolonization and its legacy for present-day Cameroon is La Guerre du Cameroun: L’Invention de la Françafrique. It is written by French journalists Thomas Deltombe and Manuel Domergue, along with Jacob Tatsitsa, a doctoral student in history at the University of Ottawa. Achille Mbembe wrote the foreward. La Guerre du Cameroun reveals the façade of a sovereign Cameroonian state behind which France negotiated, with the Cameroonian leaders of its choice, its post-independence strategic and economic hold on the Cameroonian government against a backdrop of counterrevolutionary and psychological warfare. Between 60,000 and 120,000 civilians out of a population of just over three million were killed between the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s. At least 440,000 Cameroonians were resettled in “regroupment” villages, forever changing the rural landscape of affected zones.

The French administered French Cameroon for the United Nations. It implemented policies of isolation akin to those Biya has put in place for Anglophone Cameroon today. French administrators prevented members and sympathizers of the most popular pro-independence party, the Union of the Populations of Cameroon (UPC), from communicating with the rest of the world: Administrators intercepted mail and telegraph services, and established a cordon sanitaire around the UN Visiting Missions of 1955 and 1958 to keep them away from nationalist demonstrators. In violation of the UN trusteeship agreement requiring France to prepare the territory for self-government, the French administration banned the UPC and its affiliated women’s party, youth party and confederated trade unions. With all avenues to political action closed off, the UPC leadership resorted to violence, implanting maquis (guerrillas) severely lacking in arms and resources throughout the southern regions of the territories. While the world looked the other way, the French unleashed an asymmetrical counterinsurgency, uprooting the maquis and brutally punishing the civilian populations in their vicinity. Interrogation, detention without trial, torture, and extrajudicial killings became features of daily life under a Franco-Cameroonian hybrid state even before the UN Trusteeship was lifted with independence on the January 1, 1960.

The violence increased after independence. French “technical assistants” Paul Audat and Jacques Rousseau authored Cameroon’s constitution in the months that followed. Its key feature was Article 20 which allowed the national assembly to grant full presidential powers to new President Ahmadou Ahidjo — whom the French recruited to the ranks of the postal service in 1947 and enabled to become Prime Minister in February 1958. After independence and freed from UN inquiries, France remained in command of the Cameroonian national army and police until 1965 making the war more lethal. It was after independence that the French army operationalized its forced resettlement policies, recruited tens of thousands of civilians to auxiliary militia forces, unleashed a campaign of aerial bombardment, and systematized torture as a mode of interrogation.

Deltombe, Domergue and Tatsitsa have spent the past decade delving into the partially declassified archives of France and the scattered and disappearing archives of Cameroon, and collecting firsthand testimonies of the war. In 2011 they published a meticulously referenced and nearly eight hundred page account of the war: Kamerun: Une guerre cachée aux origines de la Françafrique, 1948-1971 (La Découverte, 2011). Conversations around the book among historians, statesmen, journalists, writers, activists and students of African history and French colonial history eventually provoked responses from French officials about the war they would prefer forgotten.

On an official visit to Cameroon in July 2015, French President François Hollande, referring to the “painful memory” of Franco-Cameroonian relations, remarked: “There have been tragic episodes,” and declared his wish that all the archives be “opened for the historians.” It was the first reference a French head of state has ever made to the history of Cameroon’s decolonization.

Hollande’s words expressed the ambiguities that characterize the Cameroonian and French governments’ reticence in acknowledging the past (even as it ignored the responsibility for the roles each have played in shaping the present). In excavating the foundation of extreme violence upon which Cameroonian sovereignty was mortgaged, La Guerre du Cameroun: L’Invention de la Françafrique suffers from no such ambiguity. The authors’ earlier book served to document. This one serves to bring the past — of France, of Cameroon — into the present and open it to public debate. Whether it will succeed in holding France accountable depends upon its public reception in France, in Cameroon, and beyond. With history unsettled, the present is on shaky ground, and a different future cannot be envisioned.

Much of Cameroon’s present trips over the political detritus of unsettled memories of the past, referred to by those who survived it as simply “the troubles.” President Paul Biya himself embodies the 1960s-era Franco-Cameroonian pact forged in those violent years. He completed his secondary school education in Paris in the late 1950s, and took university and postgraduate diplomas in political science and public law in prestigious institutions of higher learning Paris in the early 1960s. Not even thirty in 1962 when he entered the executive branch of Cameroon’s government as Chargé de Mission to the President, Biya’s age and longevity — as the third oldest and fourth longest reigning African head of state — are millstones of the past weighing down an otherwise youthful Cameroon.

Neither the French nor the Cameroonian state has ever facilitated historical inquiry — in fact the opposite is true. Yet curious moves are afoot. In an interview at the book’s launch in Yaoundé in late December 2016, Philippe Larrieu, First Counsellor to the French Ambassador of Cameroon, announced that the French embassy was planning, in collaboration with a Cameroonian cultural association, a memorial colloquium in 2017. Larrieu explained that the colloquium, based on the contributions of researchers, experts, historians and political scientists, would break the silence about “the dark period in the history of Cameroon and Franco-Cameroonian relations.”

In mid-February, I received an invitation to an International Colloquium “History and Memory in Cameroon: Legacies and Practices” from Kalliopi Ango Ela. Who is Mrs. Ango Ela? She is a French expatriate who has resided in Yaoundé since 1987 where she teaches at the French school Fustel de Coulanges. She served from 2009 to 2015 as elected Counsellor and then Senator to the Assembly of French expatriates. She is also the director of the Paul Ango Ela Foundation of Central African Geopolitics, named after her late husband, a Cameroonian intellectual.

The timing appeared odd. Is this the memorial colloquium to which the French embassy’s First Counsellor referred in December 2016? But there is no explicit link to French embassy in the call for papers, the program committee or the invitation. This made scholars wonder: Is France funding and directing this memorial colloquium from the shadows? France certainly has a role to play in reconciling official history with unsettled memories of the past. But it appears that once again, and rather predictably, France would rather play puppeteer than transparently acknowledge its role in first shaping — and now underhandedly curating — its colonial past. Good faith gestures by the French organizers would have been to invite the authors of La Guerre du Cameroun to this conference, and to take steps to include survivors of the war, journalists, academics and others in Cameroon who have spent decades preserving memories of the country’s violent past.

March 20, 2017

The Dutch disease

Coming ahead of the French presidential elections in April and the German national election in September, last Wednesday’s election in the Netherlands (won handily by the center-right VVD of Prime Minister Mark Rutte) was seen as a test of populist right-wing sentiment in Europe. More importantly, it was also a referendum about left politics in the Netherlands; how we talk about race and class.

In the end, Geert Wilders’ far-right PVV, only won 20 out of a possible 150 seats, leaving the VVD with 31 seats, to form a new coalition government. More significantly, the traditional left Labour Party (PvdA) lost over 29 seats, suggesting that many voters who may have supported leftist parties before, switched allegiance to the right.

International media celebrations aside, Rutte’s win does not signal a victory over the populist, right-wing Islamophobia represented by the odious Wilders. Far from it, the fact that Wilders — against earlier predictions — did not become the largest party is directly related to Rutte adopting similar rhetoric as the PVV.

The election was animated by three linked “problems”: Islam, immigration and the economy. They are not new, however, and each have a much longer historical presence than is admitted in much of the analysis. Take the so-called “emergence of Islamophobia” in the Netherlands. What happens when we label something an emergence? What happens when the Netherlands is understood as “decent” and that this decency is now lost, categorized as having “departed” from its liberal, tolerant, reasonable past?

The reality is that citizenship rules and regulations, categories of belonging, media, educational and everyday semantics – all of the structures that organize daily life are thoroughly racialized. Take the Dutch categories of allochtoon and autochtoon which rely on colonial understandings of who was part of the Dutch empire and who was not, by designating who is “ethnic Dutch” and who are immigrants. This basically breaks down as white Dutch versus its brown and black citizens. Similarly, so are debates about who has integrated well (Indonesian colonial subjects) and who failed to integrate (Surinamese, Antilleans, Moroccans) are also based on clear colonial legacies. The violence Indonesians faced when they came to the Netherlands is erased and the racism and lack of support Surinamese, Antilleans and Moroccans were met with when they arrived, is conveniently forgotten.

When we begin tracing these historical legacies, we notice that modern nation and state building in the Netherlands was a racial project from the very beginning. When migrants began to arrive from North Africa and Southern Europe in the late 1960s, much of the discourse surrounding “problems” with the white working class was extended to these new migrant groups, specifically the notion that they needed to be civilized into Dutch culture. Surinamese men were discursively portrayed as violent and aggressive in the 1980s. Yet in the 1990s this portrayal extended to and became focused on Moroccan men.

The identity of the rational, white bourgeois Dutchman is constituted in a dialectical relationship with numerous “Others” — thus making the discursive formation necessary to Dutch identity. This draws our attention to the continuing need in Dutch society to create “Others” in order to both construct the identity of the civilized Dutchman.

When Southern European and North African immigrants arrived in the Netherlands in the 1960s, their constructed racial otherness was understood through cultural differences. Culture became the vessel through which racial difference was understood and class the vessel for understanding the racial difference of the Dutch working classes leading up to the 1960s. In both instances, racial constructions were hidden under the label of either class or cultural difference.

And yet, despite this, there is a tendency in the Netherlands to locate racism in individuals, as isolated incidents. As sociologist Melissa Weiner, who has written extensively about Dutch racism, points out:

Ask a White Dutch person about racism in their society and most will quickly respond that, except for maybe a few right-wing politicians and individual racist incidents each year, racism does not exist. Indeed, it cannot. Because, according to many, ‘race’ does not exist in The Netherlands.

As Weiner shows, this process of othering is the construction of the Dutch self-image as tolerant and thus of Dutch society as excluding racism, homophobia, sexism, and so on. Attempts to argue that this election shows how the Netherlands has “changed” and lost its tolerance/liberalism/decency are problematic and plainly incorrect precisely because building the nation was a racialized project from the very start. Islamophobia is only the most recent expression of this project, but it is not new, nor a departure.

The emergence of the Dutch welfare state is key to contextualizing this project. In an excellent post, the cultural critic Egbert Alejandro Martina shows how the emergence of the Dutch welfare state represented an attempt to make the white working class “fit for (bourgeois) society” which was seen as preferable to improving conditions of the working class by raising the standard of living. The welfare state was envisioned as a disciplinary force that would deflect attention away from structural inequalities and instead discipline the working class through biopolitics, absorbing and neutralizing any threat it posed. This later transformed as a means of disciplining bodies seen as racially and/or culturally different.

What is new, however, is today’s material context: the crisis of neoliberal capitalism and the dismantling of the welfare state. It is not a failure of integration that forces politicians to discuss Muslims; rather it has been an extremely successful tactic that has deflected attention away from the state’s role in dismantling the social services Dutch citizens have had since the 1950s. These cuts to the welfare state have led to economic inequalities that have resulted in antagonism towards anyone seen as a “foreigner.” This is not, however, a natural response to economic crisis. It is a concrete result of historical processes of class and race intersecting to produce the Dutch state and Dutch nationalism.

The tendency to ignore the Dutch colonial past – social forgetting as Weiner calls it – is important here in understanding why there is so little resistance to the extreme racism rampant in the Netherlands today. This Dutch colonial history is not something to be navigated or worked through, and indeed can be presented positively or, at least, as a relic of a time that was not necessarily “wrong.” The denial surrounding both its status as a colonial empire, and the fact that the Netherlands controlled territories until 2010 and its neutral moral position on colonialism allows the Netherlands to construct a national imaginary based on tolerance.

Similarly, Gloria Wekker’s excellent book White Innocence, points to “a central paradox of Dutch culture”: “the passionate denial of racial discrimination and colonial violence coexisting alongside aggressive racism and xenophobia.” This includes how black people are portrayed in Dutch media, deliberate ignorance about race in universities, contemporary conservative politics (including gay politicians embracing anti-immigrant rhetoric) and blackface.

It is this archive that is important to remember. White innocence, along with social forgetting, have functioned to hide the central role of race in Dutch nation building. The Dutch self is a racialized self. This is not new, but as old as the Netherlands itself.

This is why I believe the newly established political party “Artikel 1” is an important intervention in contemporary Dutch politics. Because it is based on anti-racism and not just class politics, it breaks the silence surrounding a wilful silence about Dutch history and provides what the Dutch left has long failed to provide: a politics that is about race and class and gender and sexuality – not just about class in a reductionist sense. There is still a long way to go, but speaking about race and racism is a necessary step.

* This is an edited version of a post that first appeared on Salem’s blog, Postcolonialism and its Discontents.

March 19, 2017

The Algerian Revolution 55 years later

Still from ‘Battle of Algiers’ (1966).

Still from ‘Battle of Algiers’ (1966).The Algerian revolution against French settler colonialism, which marks its 55th anniversary today, March 19th, stands as one of the most iconic victories for Third World liberation. In the furnace of the brutal, seven-year-long struggle, Franz Fanon forged The Wretched of the Earth. The Front de Libération Nationale’s (FLN), victory was remarkable not only because of the brutality of the French settler colonial project but because, although splits within the FLN certainly existed, there was a general consensus that political independence was not the end of the revolutionary process. The next stage was to transform Algerian society and reverse what the FLN understood as the economic and social backwardness caused by colonial exploitation, through a sweeping project of nationalization, centralization, and planning. The experience of Algeria’s revolution then, serves as a powerful example of both the achievements and failures of a revolutionary program put into practice with state power and massive natural resource wealth.

The FLN was made up of a wide range of ideological tendencies unified by the common desire for independence from the French. However, the left wing of the party rose to prominence after the victory in the war of independence. Ahmed Ben Bella, the first president of Algeria, represented the Marxist tendency of the left wing of the FLN, which was split between his camp and that of Houari Boumediène, who espoused an ideology similar to Nasserism in its rejection of Marxian materialism and embrace of Arab nationalism. One of Ben Bella‘s first economic policies was to nationalize industrial property and codify a system of worker self-direction.

In 1971 the regime nationalized 51 percent of the main French petroleum company operating in its territory and 100 percent of French natural gas concessions. Firmly in control of its petroleum resource revenue, the FLN set about implementing an ambitious development plan; to use petroleum revenue to develop an industrial economy that would be the basis for a total transformation of society. The FLN‘s state-led development was remarkably successful in achieving economic growth and raising living standards through huge investment in education and healthcare systems, which were non-existent before independence. Gross fixed capital formation was higher than the East Asian states on average during the 1970s and manufacturing-value added was growing faster than the overall economy by the mid-1980s.

By that time however, low oil prices exposed the contradictions of this petroleum-financed, state-led model. The manufacturing investment which the government made in the wake of the 1973 oil embargo windfall could not buffer the economy from the decline in the price of oil. In response, the regime embarked on a process of neoliberal economic restructuring. The reforms were similar to those which were being imposed onto heavily indebted countries as a condition for receiving loans from the International Monetary Fund elsewhere in the world in the 1980s. Influenced by the neoliberal ideology; “industrial policies” were out and the market mechanism became the solution to nearly every economic problem.

The sizable Algerian industrial workforce had other ideas, and led a wave of strikes culminating in the general strike of 1988, in which 98 percent of workers participated. With strikes and social unrest crippling the economy, the FLN announced that multiparty elections would be held for the first time.

What follows is well known; Islamists were able to capitalize on disillusionment with the FLN’s faltering program. That the regime had no response to declining oil prices but to cut back the gains of the previous decades through drastic austerity, leaving it vulnerable to critique from the left and the right. However, the discourse of the victorious Front Islamique du Salut (FIS) did not center on a critique of state socialism from a market rationality perspective, but the Eurocentrism of the regime’s understanding of what constitutes modernity itself.

For the FIS, the concepts of socialism and secularism were foreign, specifically French, imports, grafted onto Algerian society by a leadership that had internalized the contempt and hatred of the colonial masters, and opposed to an “authentic” identity centered on Islam.

An internalized Eurocentrism was not peculiar to the FLN, it was very much hegemonic throughout the 20th century, underpinning the competing socialist and capitalist teleologies of the time. One of the most enduring legacies of colonialism is after all, the idea that it is impossible to contemplate a future in which the rest of the world does not resemble Europe. The process of “development” was then and still is understood by most as “the diffusion of the superior [i.e. European] model,” in the words of Egyptian economist, Samir Amin.

This is a discourse which resonated because it was articulated against the backdrop of a broader shift, as the international economic and political order dominated by the binary of Euro-American Keynesianism and its Soviet state socialist challenger crumbled, taking their respective ideologies and their high modernist, teleological belief in progress through reason along with them into oblivion.

The eight year civil war that resulted from the nullification of the election results left Algeria at an impasse that characterizes the Arab world to this day. The secular modernization regime, stripped of its raison d’être, can only define itself in opposition to the Islamist threat. Devoid of the real content of the social and foreign commitments constituted its mandate, regimes like the FLN, the Baath in Syria, the Egyptian military hobbled along through the neoliberal period as empty shells. Just as financialization, deregulation, and cheap labor propped up the neoliberal order in First World, debt, geopolitical rents, and the record high oil prices have done in the Third World.

Within the constraints of neoliberalism, escaping the cycle of oil dependence is not only inadvisable, it is impossible; states should chase Ricardian advantage, diversification is distortionary, the heavy state intervention that industries require to become sustainable is infeasible, even if there is political will to attempt such an endeavor.

55 years after the victory against France, in the absence of the sweeping project that animated the revolution in its early days, Algeria has withered into another rentier security state, albeit with a secular veneer. 95 percent of the annual budget comes from petroleum. Its geriatric leadership responded to the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 by increasing subsidies, doling out a bigger share of the petroleum revenue, and crushing dissent with its infamously efficient security apparatus, just as Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies did. “Oil dollars may make the world go round, but they have kept Algeria still.” Six years later, discontent lingers, and sporadic protests and riots are common.

In 2017, however, as in 1981, the oil bonanza has come to an end, and the hundreds of billions of dollars the generals amassed in the last decade are rapidly dwindling. The recently passed annual budget is a typical austerity budget, replete with key subsidy cuts and tax hikes.

The praxis of neoliberalism has created the conditions of its own ideological collapse, which are manifest in the First World in the form of the twin shocks of Brexit and Trump’s victory. In the Arab world, these conditions opened the way for the Arab Spring uprisings. Though the Algerian regime, like the Jordanian monarchy, was able to survive the initial wave of protests unscathed, a deteriorating economic outlook in the region combined with depressed oil prices pose a huge challenge in 2017. The Algerian revolution did not die with the rightward shift of the FLN in the 1980s, it lives on in opposition.

March 16, 2017

We are all Helen Zille. Or, why the West thinks that colonialism was not all bad.

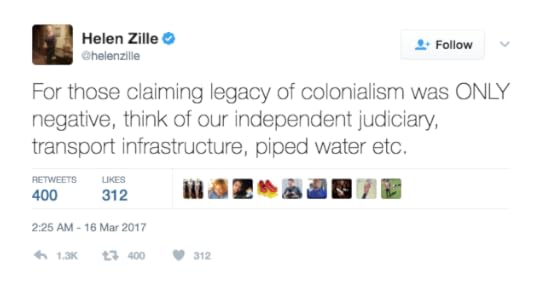

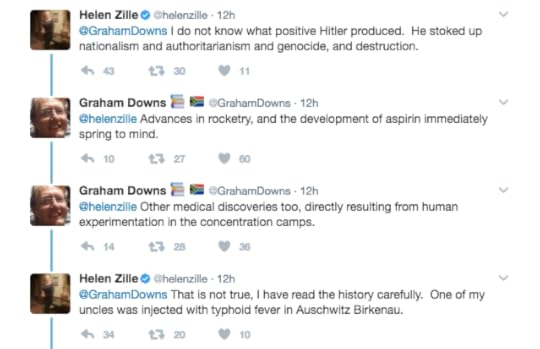

In a series of tweets circulated earlier today, Helen Zille, who is Premier of the Western Cape (one of South Africa’s nine provinces) and the former leader of the country’s second largest political party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), asserted there are many positive aspects to colonialism.

Zille, who is white, governs the Western Cape, which has a violent history of slavery (her core base includes many descendants of slaves) and is scarred by migrant labor, an integral part of capitalism in South Africa.

It all started with Zille wondering aloud why Singapore, a country “colonised as long as SA [South Africa], and under brutal occupation in WW2 [World War Two]”, was so successful and what lessons can be drawn for South African democracy. She first listed a series of neoliberal platitudes such as “meritocracy, multiculturalism, work ethic, openness to globalism, English and future orientation” – all thinly disguised colonial tropes. But unlike most of her liberal peers in similar conversations, she went further and openly endorsed the virtues of colonialism:

This reply made her defense of colonialism stand out even more:

A Twitterstorm (mostly by young black South Africans) against Zille’s words, eventually forced her to apologize. But she did not retract her claims and, at the time of writing, the controversial tweets have not been taken down. This is certainly not the first time that she airs bigoted views.

This time however the DA leadership has been more decisive in condemning the former leader. The DA is trying hard to expand support from its traditional white voter base into black communities, and Zille’s comments are a major setback. The party leader Mmusi Maimane and spokesperson Phumzile van Damme — both black — promptly rejected Zille’s views. Maimane said that the Western Cape premier will face a disciplinary process. But one wonders whether the DA leadership really means business when it comes to fighting discrimination. Mayor of Johannesburg Herman Mashaba, also from the DA, was never called to account for his xenophobic remarks which helped fuel recent violence against foreigners in Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Amidst the national outcry against Zille, many white liberals were quick to express outrage. The public outpour on social media, however, does not quite match the fact that Zille’s views are widely shared among white South Africans.

This is not a class or education issue. It goes beyond the crude beliefs of Afrikaner groups like AfriForum, and runs all the way to the top of the white establishment. White scholars rarely condemn colonial conquest in its totality. Their views of a non-racial society are shaped by a certain brand of colonial liberalism that was opposed to apartheid, but saw the idea of European civilization spreading to Africa as a fundamentally good thing, and certainly a better outcome than letting Africans rule their own countries according to their own traditions and aspirations. For them, a non-racial world is one where some fictitious “European values” have spread to all racial groups, thus ensuring that the primacy of the West is maintained.

But white South African scholars are not alone in this belief. They are not academic “deplorables” in an otherwise respectable world, an unfortunate accident of Western liberalism. They are an integral part of the Western propaganda machinery that continues to uphold the same worldview. That colonialism was not all bad is the default position of most Western social science. What has changed over time is the degree of sophistication that we use to mask these views under acceptable politically correct language.

The end of colonialism, apartheid and Jim Crow have marked the global rise of liberal racism – what sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva calls “racism without racists”. Even when we do not openly endorse colonialism like Zille does, our works are filled with strategic silences, omissions and erasures that continue to sustain ideas of Western superiority.

Some scholars hint at the superiority of the political institutions of Western democracy. Others mention the “inevitable” rise of capitalism, seen always as a quintessentially Western achievement. Others still talk about the “advanced” cultural practices of “European modernity.” Even critical Western scholarship opposed to the neoliberal paradigm rarely acknowledges the persistence of whiteness and racial inequalities, often developing criticisms of the world of finance, the banks or the multinationals that underplay the role of race in these institutions. These coded forms of racism have contributed to consolidate white supremacy in the last few decades of neoliberal hegemony.

That edifice is now crumbling. The Zilles of the world are tired of beating around the bush. They want to speak openly about white superiority and do not want to feel uncomfortable for their views.

They believe that postcolonial countries have been given a chance but failed to assert their worth, denying the fact that neocolonial structures are just as sturdy as colonial ones. They are tired of “diversity talk,” it is all a sham in their opinion. They see a return to the “good old days” of fascism, colonialism, Jim Crow and apartheid as the way forward.

The shift from liberal racism to explicit white supremacy says more about the current political moment in Europe and the US, than the obsession with the ills of the “liberal establishment.” The latter is often evoked by white middle and working classes to highlight their loss of privilege — and only theirs — as unacceptable. Their discourse is now converging with the reactionary colonial conservatism common among white South Africans, as it did in the early days of colonial conquest.

Signaling the virtues of colonialism has a clear political purpose. In a world of increasingly scarce resources, and with Western economies in decline, the fascist frenzy of the UK and US governments can only be served by stepping up the ongoing massive exploitation of natural resources in the global South.

The aspiring guardians of “Western civilization” follow in the footsteps of their liberal predecessors. With the failures of the free market fully exposed, they once again need an overt colonial ideology to justify the pillage.

In Africa, southern African whites operate as a conveyor belt for Western interests, working closely with the army of Western migrants that occupy key positions of the economy and development industry across the continent. The tiny African elites they have co-opted are rapidly losing legitimacy, and are increasingly alienated from the vast majority of citizens. Helen Zille is one of the many hired guns offering their services to the likes of Donald Trump and Theresa May to help them strike favorable trade deals and wage wars to protect Western interests.

How do Germans continue to ignore the Namibian genocide?

In July 2015, the German government acknowledged, in an as yet informal way, the genocide perpetrated by German colonial troops in present day Namibia during 1904-1908. Negotiations between the two governments commenced in November of that year. Today this process is at an impasse for a number of related reasons: the German side refuses to consider any material transfers a legal obligation following from the genocide, while in Namibia, there is consensus that an apology as well as reparations are a prerequisite to reconciliation. At the same time, both the German and the Namibian governments insist on bilateral state-level negotiations, while affected communities vociferously demand to be included in a “round table.” By now, the negotiations are also implicated in the movement for ancestral land that has gained new momentum in Namibia since late 2016. It appears that all these issues need to be addressed for a settlement to enjoy acceptance and legitimacy.

In Namibia, the negotiation process is in the public limelight. The German public and mainstream media hardly notice it. This vast difference is hard to accept or even to imagine particularly for Namibian activists, and consequently is often understood as an active refusal to acknowledge historical facts. While this has doubtlessly been the case in the past and remains to a considerable extent, another reason for what I consider as postcolonial asymmetry seems to be both more effective and intractable.

Let us rehearse basic figures: Namibia’s population of 2.3 million contrasts Germany’s 82 million; its Gross Domestic Product of US$ 11.49 billion is dwarfed by Germany’s US$ 3879 billion; in foreign trade volume, Namibia ranks as Germany’s partner No.116. By mere numbers, Namibia has very little leverage on Germany. Most Germans can easily afford to ignore their country’s colonial past including the genocide. They do not feel any impacts if they are not alerted or look out for them. Very many are not even aware that Germany once was a colonial power. Concern for some 15,000 German speakers in Namibia is not evident in the German public.

For people from Central and Southern Namibia, the opposite is the case. Vestiges of German colonialism are ubiquitous, in an array of colonial buildings and monuments, now used as tourist attractions; in the presence of an economically highly privileged and powerful, closely-knit community of German speakers; and in particular, in a persistent pattern of land distribution that is a direct consequence of the genocide. In continuation of the genocide, all affected African communities were stripped of their land. This was turned into crown land and opened for white settlement, first from Germany, after 1915 from South Africa. The landscape was thoroughly rationalized according to the needs of commercial agriculture. This remains evident in wide road corridors, fenced-in farms and spaces devoid of people and animals.

Affected communities in Namibia have kept the memory of anti-colonial resistance and of the genocide alive. Shortly after independence in 1990, a movement set in to claim apology and reparations from Germany. By now, they have coalesced into a strong voice and the government has taken up the demand, although serious controversy remains about the modalities of the negotiation process. Nevertheless, the genocide is a public issue in Namibia, and this has also been evident from big turn-outs to mark important events such as the crowd of 4,000 that stormed Hosea Kutako International Airport in Windhoek in 2011 to welcome the return of a first batch of human remains that had been deported to Germany during colonial times.

Awareness raising for the genocide remains an uphill affair in Germany, mostly taken up by small postcolonial initiatives in league with sections of the Afro-German community. These initiatives have managed to generate some attention in national and international media at special turning points, but their impact remains limited, as is the pressure such civil society moves or any opposition party can hope to bring to bear on government policy.

So far, the German government is sticking to its guns: apology as an outcome of negotiations, no reparations, limiting the negotiation process to the two governments. The last two points form the substance of the Class Action Complaint brought by Ovaherero and Nama and to be given an initial hearing by a New York judge on March 16. The need to resort to legal action is yet another consequence of postcolonial asymmetry and the stubborn recalcitrance on the part of those who seemingly can afford such a stance precisely on account of such asymmetry. And so the globally peripheral take their case to the “center” in hope that a court in a country with its own history of genocide against indigenous peoples might honor the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights.

March 15, 2017

Germany’s Marshall Plan for Africa

Angela Merkel and Mahamadou Issoufou in Niger. Image via German Government website, credit Steins.

Angela Merkel and Mahamadou Issoufou in Niger. Image via German Government website, credit Steins.On January 18th, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development unveiled its new Africa policy framework “Marshall Plan with Africa”. The idea was first put forward by global interest groups The Club of Rome and “Senat der Wirtschaft,” who emphasized that in the context of Africa’s demographic trend, Germany will have to mobilize more aid and private investment. The idea was also floated by Niger’s President Mahamadou Issoufou during German chancellor Angela Merkel’s state visit to Niger in October 2016. Issoufou called for a US$1 billion package to create jobs, prevent conflict, and reduce migration. Merkel was hesitant to endorse Issoufou’s proposal (it’s unclear why), yet just four months later Germany unveiled its Africa policy using that same title.

There is a long and misleading legacy of Marshall-Plans being called for in different parts of the world across a range of different contexts. In development advocacy, the term has often been instrumentalized by “big-push” theorists such as economist Jeffrey Sachs. These theorists are convinced that a large increase in development assistance will deliver low-income countries from poverty traps. However, the context in which Germany benefitted from the original Marshall Plan right after World War II was very specific to that moment and place. At that time, Germany had a large pre-existing industrial capacity, while the Marshall Plan’s transfers to European partner countries such as France, Italy, and the United Kingdom increased demand for German exports.

Before scrutinizing the plan in detail, it is useful to think about which political dynamics may have led to the adoption of this ambitious framework. With upcoming federal elections, Merkel has come under growing domestic pressure over her “open” refugee and migrant policy. Reports suggest Merkel has recently been in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya to discuss the migrant crisis with aim of managing the flow of migrants. It is her second Africa trip in six months after having not visited the continent in five years. Germany’s minister for international development, Gerd Müller, will likely not retain his portfolio following this year’s federal election, and aspired to leave a legacy with the Marshall Plan. He is also a member of Merkel’s Bavarian sister party CSU, which has criticized her migrant policy almost as passionately as the right-radical AFD. Similar to his British Tory counterpart Priti Patel, Müller and other German politicians have communicated and legitimized Germany’s aid budget by promising fewer migrants.

Leaving aside the moral argument about instrumentalizing international aid, and normalizing anti-migrant sentiments, evidence suggests that aid might actually increase migration. As the Center for Global Development’s Michael Clemens has pointed out, migration from low-income countries increases over the course of a “mobility transition”, (at least) until countries reach upper-middle income status. Instead of promoting fairytales to an increasingly anti-migrant electorate, policymakers are shying away from taking the courage to put things into perspective, while acknowledging the hard truths about global migration:

One, migration will not decrease from its current levels anytime soon and money invested specifically for migrant-deterrence aid is money wasted.

Two, repressive migration regimes actually force people to stay in Europe and disrupt potentially virtuous circular migration patterns. West African immigrants to France frequently moved between France and their country of origin. After the French migration regime was tightened, many feared that they would not be able to comeback, and felt forced to stay.

Three, poorer countries such as Kenya, Lebanon, and Uganda are hosting more migrants and refugees per capita, without comparable levels of xenophobia and exclusion.

Four, in the future, NATO should consider the long-term consequences of military interventions.

Another underlying political dynamic is Germany’s reluctant embrace of global leadership. Germany has historically approached international development assistance with the rhetoric of altruism. But increasingly, it has become more explicit in linking national and sometimes European interests to its international development policy. Contrary to the trend in other Western countries, Germany’s official development assistance (ODA) has increased by 26 percent in 2015, with the country spending $17.8 billion. According to Devex, German development aid is expected to increase by more than $8.9 billion more than initially planned between 2016 and 2019.

Though the increase in aid is substantial for Germany, it hardly qualifies as a Marshall Plan capable of delivering the infamous big-push for all African countries. Carlos Lopes, former Secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, joked that it is roughly equivalent to the budget of a medium city in Europe.

But rather than solely providing a material increase in aid, the plan was to provide a blueprint for future international development policy. The plan consists of three pillars: Economic Growth, Jobs and Trade; Peace, Security, and Stability; and Democracy, Rule of Law and Human Rights. Countries that pursue anti-corruption, women’s empowerment, and good governance are to receive a 20% increase in development assistance, while it is unclear how this will be judged. From a governance perspective, the plan is short on fresh proposals, but rather reiterates the uninspiring “good governance” and “rule of law” rhetoric, which has been criticized by scholars such as Mushtaq Khan. African researchers have also pointed out that the plan bypasses existing continental development frameworks, ironic since policymakers made sure to call it the Marshall Plan with Africa.

With regards to financing in the context of Africa’s large infrastructure gap, the plan also attempts to find ways with which to incentivize private, and institutional investors such as pension funds to invest in African infrastructure. Under its current G20 presidency, Germany has committed to boost current multilateral development guarantees, and aims to create a currency exchange fund against local currency risks. Helmut Reisen, formerly head of research of the OECD Development Centre, has pointed out, that this was already envisioned under the “G20/OECD High-Level Principles of Long-Term Investment Financing by Institutional Investors”, but did not succeed in significantly raising investment levels. He points out that development finance institutions such as the IFC have used innovative instruments such as a Managed Co-Lending Portfolio Program, or a First Loss guarantee to draw in long-term investors such as Allianz AG, but he remains skeptical about their potential for African countries. More emphasis should rather be placed on domestic resource mobilization and the fight against illicit financial flows, which are higher than overall development assistance according to some estimates.

While the plan calls for increased market access for African exports, it does not address the frequent disconnect of European development-and trade policy. Since the Lomé Convention in 1975, the EU has granted non-reciprocal trade preferences to African countries, but under the Cotonou Agreement, this system was replaced by the negotiation of economic partnership agreements (EPAs). EPAs are negotiated with different African regional trading blocs. Cameroon has angered other partners in the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) because of its unilateral decision to ratify the EPA. The East African Community (EAC) is divided with Kenya, and Rwanda in strong support of the EPA, and Tanzania, and Uganda calling for a renegotiation of the agreement. Germany’s stated goal is to promote job creation and increase value added exports. For this to be genuine, EPA’s have to uphold the integrity of regional blocks, leave policy space for industrial policies, and refrain from dumping subsidized agricultural products into African markets.

Finally, in light of Germany’s recent acknowledgement of the Herero, and Nama genocide, which we discussed here, Germany has yet to address its guilt as a colonial empire, and genuinely respond to calls for reparations. Traditional traditional authorities of the Herero and Nama have filed a class action lawsuit against Germany seeking reparations. The pre-trial conference of that case (Rukoro et al. v. Germany) will be held tomorrow, March 16, in New York’s Southern District Court.

March 14, 2017

The roots of the current crisis in South Africa

Over the last few weeks it has come to light that South Africa’s Social Security Agency (SASSA) has no idea how it will pay 17 million social (welfare) grants to around 11 million South Africans on April 1. This has understandably caused some concern, with the media, civil society organizations and trade unions accusing the department and the minister, Bathabile Dlamini, of deliberately endangering the welfare of the poorest South Africans. Social grants are direct cash transfers provided to South African citizens who meet specific criteria. The vast majority of grants are child grants, which in 2016 amounted to R350 per child per month (approximately US$26). Social grants are one of the few redistributive policies pursued by the state in the post-apartheid period, and they had a marked impact on chronic poverty rates and, research suggests, led to improvements in child health and school attendance.

The roots of the current crisis can be traced back to 2012 when the department shifted from a model in which provinces were charged with distributing funds to a single national model. The company that was chosen for this public-private-partnership was Cash Paymaster Services (CPS) which is a subsidiary of Net 1 UEPS Technologies Inc.In 2014 the country’s constitutional court declared the contract with Net 1 to be invalid due to extensive irregularities in the tender process—at the last minute SASSA included criteria for biometric technologies that could only be met by CPS. The court allowed CPS to continue paying out grants on the condition that SASSA regularly report back to them about developing an alternate system for grant payment. They didn’t. What has unfolded in the first few months of 2017 is a testament not only to bureaucratic incompetence, but the ways in which state elite and the private sector have found ways to swindle the poor.

What has been forgotten in the grants crisis, however, is the extent to which those who received grants have long been in a state of crisis. Since CPS took over the payment of grants in 2012 recipients have been plagued by illegal deductions from their grants. In another article, I wrote about the ways in which CPS has colluded with banks to sell grant beneficiaries dubious cell phone and insurance deals that are next to impossible to cancel. While these deductions were declared illegal by SASSA in 2016, this has meant little as they have continued apace. Erin Torkelson’s recent article in the Cape Town news site GroundUp reveals the extent of this horror: A mother in tears after receiving only 26c of her child grant from a CPS paypoint. There has been no study on the extent of these deductions since May 2016, but by all accounts (including extensive documentation by Black Sash) they are occurring at an alarming rate. All of which seems to confirm the political scientist and newspaper columnist Steven Friedman’s point that CPS effectively took over SASSA in 2012 compromising its autonomy and control over the grants process. That’s the first crisis.

The second crisis is the fact that social grants are wholly insufficient to actually support poor households and that their value has been declining as the cost of food has sky-rocketed. This is particularly acute in rural areas where the rate of unemployment is even higher than in urban townships. This is not only about corruption in the payment of grants, but the fact that many of those people receiving grants are well below the poverty line. The average inflation rate (CPI) in 2015 was 4.51% and in 2016 it was 6.59%. Between the 2014/2015 and 2015/2016 budget year old age grants increased by 4.4%. Over the same period child support grants increased by 4.7% and disability grants increased by 3.6%. What this means is that the poor can buy less with their grants each year, and this is being made worse through illegal deductions. This is being forgotten in a crisis that is being cast as a spat between politicians, bureaucrats and businesspeople.

In 2016 Nandi Vanqa-Mgijima, of the International Labour Research and Information Group (ILRIG), and I conducted research on social grants, illegal deductions and the ways in which grants are used in poor and working class communities. We found numerous cases of social grants being used beyond the household, as an effective subsidy to inadequate public services. Community health care workers used their own grants to purchase medical supplies to treat people with HIV-AIDS living in their neighbourhoods. Waste pickers used their grants to purchase the equipment they need to clean up their communities and, as a result, make a living. Parents used social grants so their children could get to university when student loan funding was inadequate or late. Social grants are, in many senses, the glue holding families and communities together. Disruptions in payment would be catastrophic and would drive many into the arms of formal and informal moneylenders—although this is already happening as Net 1 provides microloans to grant recipients through Easy Pay and Moneyline.

The third feature currently being overlooked is the extent to which the chaos generated by this crisis presents an opportunity for the ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC). Politicians using social grants to further their own ends is nothing new. The ANC has essentially worked to position the party rather than government as the main benefactor in this system. During the recent local government elections, for example, the ANC’s Gwede Mantashe reminded unemployed fathers that it was the ANC who ‘raised’ their children through child grants. In a recent press conference, the minister of social development, Minister Dlamini was lavished with praise by community and religious leaders for ‘uplifting’ the poor. Dlamini is also president of the ANC’s women’s league and staunch supporter of president Jacob Zuma.

While the confusion created by the current scandal certainly casts Dlamini and other ANC bigwigs in a bad light, it also presents a rather terrifying opportunity in which the party could begin to use social grants to further their own interest—more so than at present. It is common knowledge that, in almost every township in the country, having political connections, which most often means through an ANC councillor, is a sure way to receive tenders and access to various forms of employment. In one township that I’ve conducted research getting a public works job usually involves going to local party meetings and donning a party t-shirt. Is it so unthinkable that access to social grants could similarly be used as a form of political patronage in the future?

Finally, there’s the already well-documented fact that the CPS contract has been enormously beneficial to a range of characters within or close-to the ruling party. The fact that SASSA had no real contingency plan for who would take over grant payments after the contract was declared invalid by the Constitutional Court in 2014, or claimed that the renewed tender bid was unsuccessful, speaks to the extent to which they are willing to go to preserve networks of graft and influence. The recent revelation that President Zuma’s lawyer Michael Hulley was involved in negotiations to keep the CPS contract only confirms the extent to which this contract is bound up in shady business and political deals.

The country’s constitutional court has repeatedly asked SASSA to explain why it had no contingency plan for the payment of social grants when the current contract expires at the end of March. It should be clear by now that Dlamini has no interest in seeing SASSA insource grant payments. She has effectively positioned CPS as the only body that is capable of distributing grants nationally. And this may very well be true, but this is only because officials at SASSA have ensured that this is the case. Whatever system of payment emerges in the future it will almost certainly involve CPS and Net 1, and because of this money will continue to flow to their bank accounts and their majority shareholders, Allan Gray, who recently described illegal deductions from social grants as part of a process of ‘financial inclusion’ for the poor. Who benefits from this will speak volumes about the nature of the current crisis and the extent to which a few politicians and business people are willing to risk the livelihoods of millions to line their pockets.

March 10, 2017

Was Mohandas Gandhi a racist?

In April 2015, the statue of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in Gandhi Square, Johannesburg was almost covered with white paint by a young protestor before he was arrested. The previous months had seen a sustained agitation at the University of Cape Town for the taking down of the statue of Sir Cecil Rhodes – the imperialist and racist benefactor of the University.

The statue came to stand in for a colonialism yet to end. In this attack on pigeon perches all over South Africa, a statue of the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa in Durban was covered in red paint; perhaps only because he was white, and not as an indictment of his poetry. There was some irony to the fact that the statue of Gandhi was almost whitewashed, considering the better part of his life was spent in fighting white imperialism.

This month, professors at the University of Ghana called for the removal of the statue of Gandhi that had been unveiled by the President of India in June. All of these instances are reflective of a rethinking happening in Africa of the role of colonialism, anticolonialism and the idea of African identity.

The politics of statuary represents a deeper crisis located in questions of belonging, entitlement and exclusion in postcolonial Africa.

In 1986, the Kenyan writer and intellectual Ngugi wa Thiong’o (formerly James Ngugi) wrote his manifesto Decolonising the Mind, arguing for linguistic decolonization and combating the continuing influence of English as a language and European thought in politically decolonized, but intellectually still-colonized Africa. Thirty years down the line, the same issues have resurfaced; Ngugi, Frantz Fanon, and the South African thinker of black consciousness, Steve Biko are back on the agenda as South Africans and Africans, more generally, ask themselves, what has not changed.

African universities have been ravaged by the attack of neo-liberal thinking and privatization that have made universities into factories and leeched them off politics. In South Africa, a battle has just been joined. The Feesmustfall movement that commenced in late 2015 challenged both high fees and the exclusion of youth from universities.

The movement also protests against a syllabus that is nothing more than a version of courses taught in Euro-American campuses. The universities in Africa are haughtily monolingual in a multilingual landscape and the issue of African knowledge systems is not even considered. We gave up this battle, if it was ever fought, in Indian universities fairly early on, producing generations of academics to service the Euro-American knowledge economy, much as we produced clerks for the British colonial service.

Now, what does all of this have to do with Gandhi and statues of him?

For this, we need another diversion into the histories of Indians in Africa. For over half a millennium, Indian mercantile groups, particularly Gujaratis, have been trading with Africa, preceding the coming of European colonialism. They came to control trade over much of East Africa and this led to tensions with a largely agrarian African populace. As money lenders, petty shopkeepers, and as oceanic traders, the ubiquitous Indian became a metaphor for commerce.

VS Naipaul’s novel A Bend in the River (1979) was an early exploration of the simmering animosity between Indians and Africans, and the protagonist Salim, has to leave the African country where he lives and trades in the face of a rising tide of black nationalism. In South Africa, while the first generation of Indians largely came as indentured labor, many merchants came as passengers on the ships and set up businesses, arousing the ire and racism of local white Europeans.

Under apartheid, Indians built up their own institutions of education and networks of trade, drawing upon historical connections as much as skills derived from hardship. They also participated in anti-apartheid politics producing leaders, such as Monty Naicker, Amina Cachalia, Yusuf Dadoo and Ahmed Kathrada. Gandhi and his idea of non-violence were an organising principle for the African National Congress, and it allowed for a politics of affinity between black African and Indian. When apartheid ended, a significant majority of Indians were well placed to take up new opportunities, economic and political, aided by affirmative action for those historically disadvantaged under the white Afrikaner rule.

For the majority of black people who have been disadvantaged first under apartheid and then under post-apartheid politics, several factors, such as an economy not in their control, a kleptocracy in power, and institutions weighted against the entry of the poor as well as the perceived success of the Indian community feed into the discourse of Africanness and the outsider. Uganda witnessed the most extreme form of this in 1975 when the dictator Idi Amin expelled Indians from the country.

Gandhi has become an icon of Indian identity and its metaphor all over Africa. Gandhi was invited to come to South Africa in 1893, from his career as a briefless barrister in India, by a wealthy Gujarati merchant to resolve a familial dispute. Once in South Africa, he realized he had landed in the middle of a politics of race that was about making legislative and legal distinctions between Whites and the rest.

Gandhi fought a rearguard action against a slew of legislations that brought together racial discourses of disease and hygiene along with the fear of Asiatic migration into South Africa aimed at the Indian laborers in particular. Gandhi’s strategy was to disaggregate the threat: separating the Indian merchant from the Indian laborer; the Indian from the African; the rich and middle-classes from the poor and indigent; the clean from the dirty; and the civilized from the barbarian.

Gandhi resented the attempts “to degrade the Indian to the position of the Kaffir” and degeneration that would follow. He said:

“By persistent ill-treatment they cannot but degenerate, so much so that from their civilized habits they would be degraded to the habits of the aboriginal Natives, and a generation hence, between the progeny of the Indians thus in course of degeneration and the Natives, there will be very little difference in habits, and customs, and thought…a large portion of Her Majesty’s subjects instead of being raised in the scale of civilisation, will be actually lowered.”

Gandhi presented the effort of the Indians in South Africa, as a manly “struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

When university professors ask for the removal of Gandhi’s statue, they draw upon these multiple histories. Gandhi is a metaphor for the Indian presence in Africa and histories of both Indian racism as well as commercial wealth. The idea that decolonization as yet has not been achieved targets both questions of western knowledge as much as perceived Indian economic success. It also represents an elite discourse that deflects the ills of the nation-state and postcolonial corruption on to the “outsider” and “foreigner”. To paraphrase Samuel Johnson, xenophobia is the last refuge of the postcolonial scoundrel.

Gandhi in South Africa certainly played the politics of race but his life was one of an unremitting engagement with the meanings of inclusion and exclusion. The irony is that, while Gandhi becomes increasingly sidelined in the maelstrom of Indian politics, in Africa he has come to stand in for the Indian presence.

* This post was previously published on Scroll.in. It is republished with the permission of the author.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers