Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 102

April 14, 2022

Integrity always pays

Image via Bildnachweise CC BY 2.0.

Image via Bildnachweise CC BY 2.0. In a play I watched 15 years ago in Ouagadougou, a character on stage indignantly cried ���Everyone knows who killed Sankara!��� His counterpart quietly replied ���Really?��� The audience held its breath tensely. The first character, deflated, mumbled ���Yes ��� it was malaria.��� Bursts of cathartic laughter.

Today Burkinabe no longer resort to such subterfuge to talk about Thomas Sankara���s death. A historic trial in Ouagadougou last week established responsibility for the assassination of the iconic revolutionary leader and his 12 companions during the coup of October 15, 1987. The stiff sentences of life imprisonment handed down to the three main accused, former President Blaise Compaor�� (who succeeded Sankara), and two senior members of his military command, Hyacinthe Kafando and Gilbert Diendere, also sent messages that many Africans have been yearning for: impunity has its limits, and dreams shall not be killed.

The dream that cannot be killed is that of continuing what Sankara achieved in his four short years of rule. Remembered for being a thorn in the side of Western powers���France in particular���through his relentless challenges to the neocolonial world order, Sankara stood out for the extent to which he actually walked his talk. Applying his vision of integrity and self-reliance, he was uncompromising on corruption and drastically reined in government waste, obliging ministers to trade in luxury cars for simple Renault 5s and fly in economy class.

Thanks to his sincerity, at a time when most Africans languished in morose post-independence hangovers, Sankara galvanized Burkinabe to invest their own money and labor in community infrastructure development. In 1987, the Food and Agricultural Organization noted with astonishment how quickly Sankara had helped the dry Sahelian country to finally achieve food self-sufficiency. Particularly prescient on environmental issues, Sankara obliged every resident to plant at least one tree, and one government program planted 10 million trees in just fifteen months. With clear-eyed foresight, in a 1985 speech to forest rangers, he warned that the destruction of the Amazon rainforest would have devastating consequences for all. Sankara summed up his greatest achievement as being getting Burkinabe to have confidence in themselves and in their ability to shape their own destiny.

The Sankara trial, which ran over six months and saw 110 witnesses take the stand, was serious business. But it also had its moments of ridiculous revelations, with disclosures of details that could have come straight from the mind of satirical playwrights. Ousseni Compaor��, Sankara���s chief of military police, revealed how he stumbled upon Sankara clearing out his office desk drawers before traveling abroad. Sankara explained that he knew full well that in his absence Blaise always found an excuse to occupy his office, and thus this was a habitual precaution he took.

There was also the story of soldier Bossobe Traor��, whom the trial acquitted, confessing to his 1987 girlfriend, while she served him soup and beer at her eatery, that they may never see each other again because in a few days there would be a coup against Sankara. The eatery was called La Buvette Coloniale (the Colonial Bar). What more ironic a setting could there be for a Judas-like betrayal of an African leader celebrated for standing up to colonial powers?

The weightier moments of ridicule involved adults stubbornly refusing to take responsibility for their past actions. Soldier Nabonswende Ou��draogo, sentenced to 20 years imprisonment, will likely need more time than that to live down the ridicule of his defense. When a witness account placed him in the thick of the action during the coup, he explained that the witness must be confusing him with another soldier, a certain ���Nasonswende.��� The prosecution lawyer pointed out that the so-called Nasonswende was a good deal taller. Undeterred, Nabonswende went on to explain that while he was present at the Conseil d���Entente, the military headquarters where the fatal shootings happened, when he heard shots, despite all his years of military training he chose to jump, fully armed, into an empty swimming pool where he remained from 5pm until 9am the next day.

Nabonswende of course was just small fry in this trial, though it is worth pointing out that other subordinates, doing little more than following orders, who owned up to their actions, such as soldier-driver Yamba Ilboudo, received lighter sentences. The readiness with which the higher-ranked accused adopted ridiculous stances, however, is a greater cause for consternation.

General Gilbert Diender��, at the time responsible for the security of the Conseil d���Entente camp and chief of the commando that carried out the coup attack, to his credit, actually turned up for the trial, unlike Compaor�� and Kafando who had to be judged in absentia. (To his discredit, Diender�� had little choice as he was already in prison for a coup he led in 2015, one year after Compaor�����s fall.) However, for someone who held posts which required a high level of responsibility, he claimed responsibility for practically nothing. In his version of the fateful day, he had left the Conseil d���Entente in the afternoon by a small gate in the back for the obligatory Thursday sports session a few kilometers away. When he heard the shots, he made no use of the walkie-talkie he had at his disposal as a senior command, but decided to trot back ���prudently��� to the camp unarmed and in his tracksuit to find out what was going on. He arrived to find Sankara and his companions dead, and concluded that a member of his commando had taken an unfortunate and unilateral initiative to arrest Sankara. The judges chose instead to believe the witness accounts that placed Diender�� at the camp just before the act, and that indicated he had clear foreknowledge of the planned coup and was being reported to by those tasked with carrying out the plan.

Compaor��, exiled in Cote d���Ivoire since his ousting by the 2014 mass insurrection, simply boycotted the trial. Compounding this dismaying lack of courage was Compaor�����s choice of lawyer: Pierre Olivier Sur, a Frenchman (moreover the only white lawyer of the trial) who seemed incapable of not dripping with disdain for Compaore���s country. At the outset of the trial, on RFI radio, Sur, with cheerful scorn questioned, how serious any proceedings that were to be held in a ���banquet hall��� could be. The choice of this large infrastructure, moreover built by the Compaor�� regime, was made to permit a larger audience to attend the trial, and luckily so, as on April 6, 2022, the 1000-seater hall was packed full with family members and ordinary citizens eager to hear the verdict of what Sur repeatedly dismissed as a ���sham��� trial. (In the inevitable film version of the trial, Sur���s character would likely loosen his inhibitions and just go ahead and call it a ���banana-republic��� trial). Interviewed after the verdict from Paris, Sur called for it to be thrown into the ���dustbin of judiciary history,��� as the Burkinabe court���s decision would certainly be overturned by more competent international courts. Aside from claiming that his client had not received legal summons, he did not give much detail on why a historic trial for Africa belonged in a dustbin.

Sankara, despite his great popularity, was nonetheless a divisive figure at home. Not all Burkinabe welcomed the outcome of the trial. Supporters of Compaor�� and Diender�� said the stiff sentencing thwarted efforts at national reconciliation. They forget perhaps that reconciliation requires, first, actual dialogue (Compaor�� refusing to attend the trial excluded this possibility), and second, speaking honestly and with responsibility. Before the overflow of citizen frustration resulted in the 2014 insurrection, several opportunities were offered to Compaor�� to exit history through a respectable door; he ignored these, ended up fleeing his own country, and taking up his wife���s nationality to avoid extradition. Had either of the three condemned to life imprisonment shown the courage to play their part in reconciliation by recognizing their past errors, the sentencing likely would have been different. They would also have avoided the ridicule they poured on themselves.

A while back, Zimbabwean anthropologist Shannon Moreira, writing about the climate crisis in Southern Africa, asked: ���What kind of ancestor do you want to become?��� African leaders should regularly start asking themselves that question, for the Sankara trial shows that sooner or later history shines a harsh light on ridiculous irresponsibility. Ordinary citizens too need to ask themselves that question. One defense lawyer���unable to understand why Sankara did not flee when intelligence reports from several countries (Algeria, Cuba, and the US, among others) warned him of an imminent coup���stated, ���If [Sankara] had been normal ��� in his place ��� I would have gone to Ghana and tried to make Blaise Compaor�����s life miserable from there. Or I would have gone to Fidel Castro���s Cuba. I would have taken my wife and two kids, and left behind Burkina Faso and its problems of under-development.���

These are only easy choices for those who do not ask themselves what kind of ancestor they will be. Sankara clearly understood that integrity, while sometimes supremely painful in the short term, always pays in the long term.

April 13, 2022

Art and the struggle for Ambazonia

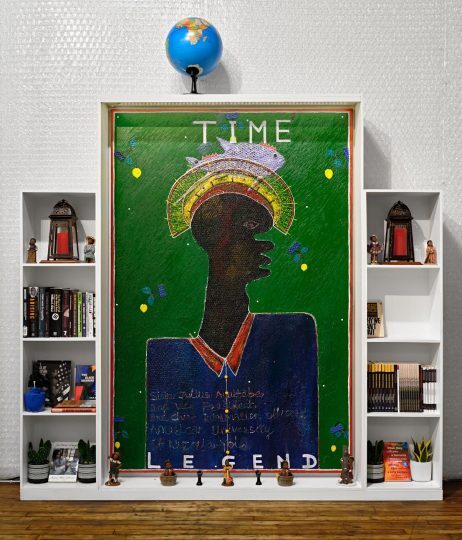

Adjani Okpu-Egbe, "Sisiku AyukTabe, the Martin Luther KING Jr. (MLK) of Ambazonia," 2021, mixed media on canvas mounted on customized wooden bookshelves with varied object installation, 76 x 79 x 9 in. Image courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP); photograph by Shark Senesac.

Adjani Okpu-Egbe, "Sisiku AyukTabe, the Martin Luther KING Jr. (MLK) of Ambazonia," 2021, mixed media on canvas mounted on customized wooden bookshelves with varied object installation, 76 x 79 x 9 in. Image courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP); photograph by Shark Senesac. ��� Adjani Okpu-Egbe���I want my work to be the hypothesis to someone else���s research.���

Artist Adjani Okpu-Egbe, wrapping up a five-month artist residency in Brooklyn, volunteers this statement in Bursting Bubbles (2021), a short film by Maliyamungu Gift Muhande that premiered in late February 2022. The Cameroonian-born artist���s scientific-sounding framing might seem out of place. In fact, it flips the script on everyday notions of art viewing as passive contemplation������taking in��� exhibitions, ���receiving��� messages, etc. For Okpu-Egbe, art instrumentalizes the viewer for a collective endeavor. What, then, is the hypothesis? And what is the research?

Okpu-Egbe���s solo exhibition in Brooklyn, curated by Amy Rosenblum-Mart��n with Maliyamungu Muhande as curatorial advisor, ran from September 2021 through February 2022 in conjunction with the artist���s residency at the International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP). The exhibition title alone offered much to consider: On Delegitimization and Solidarity: Sisiku AyukTabe, the Martin Luther King Jr. of Ambazonia, the Nera 10, and the Myth of Violent Africa. Its three gallery rooms displayed twelve artworks plus a documentary-style film tracing a long arc of political history.

After being governed by German colonial rule from the late 19th century until World War I, Cameroon was divided under League of Nations mandates (later United Nations ���trust territories���) into a small western British zone and a much larger French zone. This division ended upon independence in 1960, when a French-backed Cameroonian government took power, led by Ahmadou Ahidjo (1960-82) and then Paul Biya (1982-present), who is now Africa���s second-longest-serving head of state. Okpu-Egbe, as both artist and activist, focuses on conditions in Anglophone southwestern Cameroon, where he was born in 1979 (in Kumba) and lived until 2004. He is now based in London.

Anyone familiar with African decolonization likely knows the names of Francophone Cameroonian anticolonial nationalists active in the country���s southwest and coastal regions and abroad. These include Ruben Um Nyob��, a founder of the Union des populations du Cameroon (UPC) who died at the hands of the French military in 1958, and F��lix Moumi��, another UPC leader whose poisoning in Geneva in 1960 by the French secret service was never brought to justice. Okpu-Egbe���s work shines a light on more recent���yet perhaps lesser-known���political developments. He especially highlights ten incarcerated activists, whom he dubs ���the Nera 10,��� who had been arrested at the Nera Hotel in Abuja, Nigeria in January 2018 and subsequently extradited to Cameroon. The Nera 10���s leader is Sisiku Julius AyukTabe, a champion of nonviolent self-determination for the Anglophone southwest. Officially, this area comprises Cameroon���s Northwest and Southwest regions, but advocates have renamed it Ambazonia in the context of what has come to be known as the Anglophone Crisis (2016-present).

���Ambazonia,��� coined after Ambas Bay in the mid-1980s, has been adopted by several groups seeking Ambazonian independence amid a broad spectrum of Anglophone tactics and goals that range, in varying combinations, from negotiation and decentralization to armed insurrection and full secession. As Okpu-Egbe explained in an interview, however, the Anglophone Crisis isn���t fundamentally about language. It���s more about citizenship and sovereignty; it stems from government efforts to marginalize residents of the former British Southern Cameroons by undermining their strong judicial system, school curricula, and social organizations, all of which happen to be (at least partially) Anglophone in origin.

In ���Sisiku AyukTabe, the Martin Luther King Jr. of Ambazonia��� (2021), Okpu-Egbe paints the impassioned and now imprisoned Ambazonian leader AyukTabe, his head turned in profile and upper torso in frontal view, as a ���legend��� on the cover of Time magazine, framed tangibly with shelves displaying books, lanterns, figurines, plants, a globe, and other objects. Large flat swaths of color on the canvas contrast with the smaller textured zones���imprints of bubble wrap on casting paint���constituting AyukTabe���s head and the fish adorning his crown. Okpu-Egbe here politically mobilizes what we might call ���legitimization,��� countering the ���delegitimization��� of the exhibition���s title���a reference to all-too-common attributions of African conflicts to ancient tribal hatreds (���the myth of violent Africa���), or to scant coverage of Cameroon in the international media despite thousands dead and more than 700,000 displaced in recent years.

Adjani Okpu-Egbe, “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self,” after Kerry James Marshall, 2021, mixed media on paper, mounted on side of dismantled baby crib, 68 x 27 x 8 in (left); shown with “A Dedication: Tamir Rice, Baby Martha Neba of Muyaka, Solidarity and Hope,” 2021, acrylic and oil on canvas and mixed media installation with found objects, 76 x 26.5 x 7 in (right). Image courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP); photograph by Shark Senesac.

Adjani Okpu-Egbe, “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self,” after Kerry James Marshall, 2021, mixed media on paper, mounted on side of dismantled baby crib, 68 x 27 x 8 in (left); shown with “A Dedication: Tamir Rice, Baby Martha Neba of Muyaka, Solidarity and Hope,” 2021, acrylic and oil on canvas and mixed media installation with found objects, 76 x 26.5 x 7 in (right). Image courtesy of the artist and International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP); photograph by Shark Senesac.This leads us to ���solidarity,��� the exhibition title���s second half. In a sense, Okpu-Egbe and his fellow activists (notably the Ambazonia Prisoners of Conscience Support Network) follow in the footsteps of earlier anticolonial nationalists. The work of these anticolonial nationalists, documented by historian Meredith Terretta and others, involved appealing to the international community through petitions to the United Nations and forging pan-African connections elsewhere in Africa and in the diaspora. Okpu-Egbe speaks forthrightly of his art as a platform for activism. His restoration of AyukTabe���s good name on a replica cover of Time stands as a metaphor for this platform���and maybe also for the overarching project of Ambazonians, who are not ���separatists,��� Okpu-Egbe insists, but ���restorationists��� striving for wholeness and belonging.

Analyzing Okpu-Egbe���s portrait of AyukTabe in a review for Hyperallergic, art critic Billy Anania found it ���unclear whether the inclusion of this corporate magazine [Time] aims to be devotional or ironic.��� Maybe both, and neither. Could the word ���tactical��� also capture the infiltration of Time by one of Ambazonia���s sage leaders, who gets likened to Martin Luther King Jr. and appears in the signature deep brown-black skin tone of one of the most celebrated African American painters, Kerry James Marshall? It is significant that Marshall���s avowed mission is one of restoring visibility to black subjects; Okpu-Egbe cites him directly in another work in the exhibition, ���A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, after Kerry James Marshall��� (2021). The United States, with its forceful African American constituency, is, after all, an influential center of global power. For better or worse, though mostly for the better, to build community and find visibility in the US is to amplify one���s cause.

April 12, 2022

An independence revue

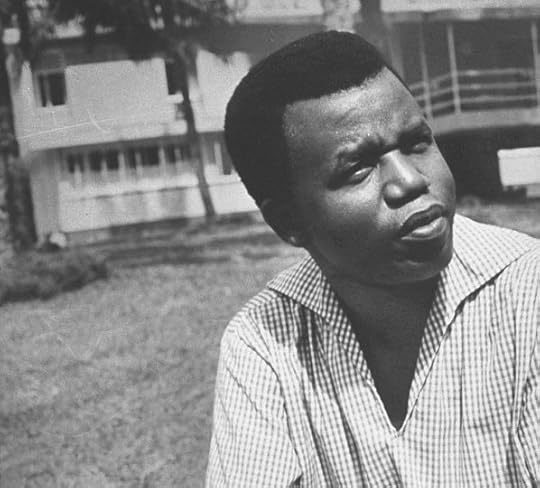

Image credit Carlo Bavagnoli, 1966. Public domain image.

Image credit Carlo Bavagnoli, 1966. Public domain image. This month on Africa Is a Country Radio, we wrap up our literary theme with a show inspired by Chinua Achebe, and take a listen to music from the post-independence era. We start out with music from the early 1960s, the point at which many African nations first came into being (after many years of imagining what nationhood might mean), where we can hear how some of the threads of national identity we have today were formed���borrowing global influences, and inserting local perspectives into both the form and content of the music. Then we move into the political, economic, and creative peak of post-independence in the 1970s when most nations became independent, some of them saw a commodities boom, and many local music industries saw their peak in investment. The music recordings from throughout this era is some of the most inspired, popular, and globally influential the African continent has ever produced.

Listen below, or on Worldwide FM and follow us on Mixcloud.

Sanctioning the regime in Senegal

Photo by Catherine Avak on Unsplash.

Photo by Catherine Avak on Unsplash. On Sunday, January 23, 2022, nearly seven million Senegalese voters were expected to elect mayors and departmental councils in a combined election that had been postponed three times. More than a dozen political parties and coalitions competed in 500 municipalities and 46 departments. Despite the plurality of the political formations, three coalitions drew most of the popular attention and votes.

The ruling coalition, Benno Bokk Yakkaar (BBY), had the daunting task of consolidating its political gains since 2012, when it triumphed in legislative, municipal and presidential elections. One of BBY���s major challenges was to win in large cities, such as Dakar, Thies, Saint-Louis, Kaolack, and Ziguinchor and safeguard its electoral base following a 2019 presidential election victory. Further hurdles arose from dissent within the President���s camps that led many allies to form parallel sub-coalitions. Despite conserving the majority of the districts, the BBY���s margin of victory significantly diminished.

Yewwi Askan Wi (YAW), a coalition spearheaded by Ousmane Sonko and Barthelemy Dias, both considered the rising stars of Senegalese politics, along with Khalifa Sall, a former ally of President Macky Sall. All three have been the subject of legal challenges: Khalifa Sall was imprisoned in 2018 for alleged embezzlement of public funds, losing his job as mayor of Dakar before being pardoned by President Sall (no relation). Following his official candidacy nomination for Dakar mayor, Dias appeared in court regarding a 2011 case involving the death of a young man named Ndiaga Diouf. The latter was shot dead after he and a group of people (allegedly sent by the then ruling Senegalese Democratic Party���PDS) attacked Dias and his Mermoz Sacr��-Coeur City Hall. Although he claimed self-defense, Dias spent six months in prison in 2011 and was freed in 2012 when Macky Sall took office. Sonko, a rising politician popular among the younger Senegalese, is the subject of a rape charge that led to unprecedented civil unrest across the country. On March 3, 2021, Senegal experienced the worst popular uprising in its history following Sonko���s arrest. A young masseuse, Adji Sarr, alleges that Sonko, the most vocal opponent of the Sall regime, raped her several times in the massage parlor and threatened her life. Sonko denies all allegations, however his subsequent arrest as well as growing frustration with the ruling coalition sparked demonstrations across the country targeting the ruling coalition, government officials, public infrastructures and French-owned multinationals. After five days of bloody confrontation, and 14 people dead, President Sall mobilized the army to support the embattled police and Sonko was released under judicial supervision.

Although Sonko���s case is still pending, the spectra of the uprising, doubled with the socio-economic ordeals of COVID-19, continue to hover over Senegal���s popular consciousness. The uprising particularly fueled media and popular conversations as well as the campaign���s rhetoric and swayed votes against the regime. Therefore, the significance of these elections lay in a trinary: first, the need for the Sall regime to ���reconcile��� with the masses post-uprising, to test its waning approval rating and the citizens��� eagerness to express their grievances against a precarious and dependent economic; second, a weaponized judicial system under attack (by the executive branch); and finally a deliberate lack of clarity regarding President Sall���s intent to run for a third term in 2024. The latter point is at the heart of the Senegalese political conversation. President Sall declared on live TV in December 2019 ���my response is neither yes nor no��� to the question of whether or not he was going to seek a third term. To many citizens, this seemed like overt constitutional defiance and a gross lack of respect vis-��-vis the people to whom he promised: ���In 2019, if the people renew their trust in me, this will be my last term. I think it���s very clear and it���s settled by the constitution.��� Supporters of the YAW coalition leaders continue to deem charges brought against Sonko, Dias and Khalifa Sall as politically motivated. Meanwhile, YAW is banking on a bottom-up strategy to dominate the municipal districts and weaken the dominant coalition in the upcoming legislative (2022) and presidential elections (2024). Insisting on President Macky Sall���s ineligibility for a third term (per the current constitution), YAW plans to support several candidacies in 2024 and coalesce behind its highest-scoring candidate for an eventual runoff election.

A third coalition, W��llu Senegal, is led by the former ruling party PDS. Besides striving to leave a solid imprint in the municipal election, W��llu Senegal also aims to restore the popularity of the PDS, which has been in decline since it lost power in 2012. (Abdoulaye Wade, Senegal���s president from 2000 to 2012, and whose unconstitutional race for a third term lost them that election, is still listed as the party���s General Secretary.) Apart from Sonko���s who is a staunch self-proclaimed pan-Africanist, there are no apparent ideological demarcations between these political coalitions.

Election day in January 2022 remained relatively peaceful around the country in contrast with the cycle of violence noted during the campaigns. Three days prior to the vote, severe clashes took place in Dakar between opposing supporters of Barthelemy Dias, contender for the highly coveted mayoralty of Dakar, and members of the Coalition BBY. Both camps blamed the other for incidents that resulted in three people being seriously injured. Similar acts of violence occurred in Ziguinchor, Sonko���s stronghold, where supporters physically fought with members of the ruling coalition on election day.

Major wins and lossesThe YAW and BBY claimed victory in the wake of the 2022 elections, and the former dominated in Gu��diawaye, Dakar, Thi��s, Diourbel, Ziguinchor, and Rufisque among other key places. The significance of these locations is that they combine 60% of the Senegalese electorate thus posing a major threat to the ruling coalition in the upcoming presidential elections. The loss of Gu��diawaye, a city administered until 2022 by President Sall���s brother (Aliou Sall), was highly symbolic and reflective of the popular disapproval of the Sall regime as well as the popular disdain Aliou incurred as a result of shady dealings with Frank Timis around oil and gas contracts widely exposed by the Senegalese media and a BBC special report in 2019. Sonko���s victory in Ziguinchor, formerly run by Sall���s ally, Abdoulaye Bald��, consolidates the former���s supremacy in the Casamance region, which he won with a landslide during the 2019 presidential election despite the enormous resources President Sall and his allies injected in the region to gain popular endorsements. Since Sonko officially took office as the sixth mayor of Ziguinchor in February this year, he has taken strong and symbolic actions including Africanizing street names that carried symbols of French colonization. The public warmly welcomed this rechristening, which reflects Sonko���s pan-African agenda. Dias, the new mayor of Dakar, has promised similar initiatives.

The BBY���s defeat in Dakar remains the most resounding setback, although Macky Sall trivialized it, arguing that the capital���s City Hall was not in his hands or his political formation to begin with. He stated: ���if one loses in places they���ve never won, it is not the end of the world. I never won in Dakar. In Ziguinchor it was Abdoulaye Bald�� who always won. Thi��s was always controlled by Idrissa Seck.��� This attempt at minimizing the opposition���s momentum seemingly conceals an electoral miscalculation and/or a ���misreading��� of the results. If similar voting patterns unfold in the upcoming presidential election, the opposition will win the popular vote and take power. In other words, the ruling party won the majority of the municipalities and departments, but only totaled about 43 percent of the votes, a significant decline in contrast to its 58 percent in the 2019 presidential election. This is analogous to an American presidential election where a candidate could win the majority in the electoral college, lose the popular vote, but still get elected president. If BBY scored below 50% in a presidential election, this would trigger a runoff election which has proved detrimental to the regime en place as evidenced by Senegalese political history in the last two decades. Therefore, the municipal election was an undeniable loss for BBY and maybe an antecedent to the upcoming presidential race.

A key takeaway from the 2022 poll is that, in contrast to the neighboring countries that recently experienced military coups, the Senegalese democratic process remains fundamentally solid. However, this should not be taken for granted, particularly when it comes to term limits. Political clientelism and the weaponization of the judicial system and bodies (especially women���s bodies) for personal political gains also remain major stumbling blocks in Senegalese democracy. The massive participation of young contenders and calls for all candidates to prioritize young women���s agenda also made these elections historically noteworthy. This materialized into the resounding victories of YAW candidates Khadija Mah��core Diouf and Seydina Issa Laye Sambe in districts formerly controlled by BBY. Their victories are�� the result of a frustrated youth vis-��-vis a regime that has failed to solve the staggering unemployment rate, corruption, injustice, and lack of opportunities. Though youth candidacies might be construed as ���reactionary,��� they have redefined the notions of participatory and representative democracy in Senegal. The most important takeaway is that this recent electoral cycle constitutes a warning sign for a regime that peddles the idea of a third, unconstitutional term. After defying the state apparatus in 2021, Senegalese voters have sent a strong message of disobedience and sanction via their ballots in 2022 and may have already signaled their readiness for regime change in 2024.

April 11, 2022

This is appropriation that���s acceptable

Image via Akal�� Wub�� Facebook profile.

Image via Akal�� Wub�� Facebook profile. After twelve years of covering, performing, and writing Ethiopian groove within the 1960s and 1970s vintage repertoire, Akal�� Wub�� recently dissolved. The group released four albums over the course of their career, the last one a celebrated collaboration with veteran Girma Beyene after his comeback.They were one of the most prominent foreign performers of the ���Swinging Addis��� groove, which, fifty years on, is a global language. I have seen Akal�� Wub�� records on display at the iconic Fendika in Addis Ababa and joined Ethiopians who danced in nostalgia during their performance with Girma in London. The tenure of the quintet���consisting of Etienne de la Sayette, Paul Bouclier, Lo��c R��chard, Oliver Degabriele, and David Georgelet���shows that Westerners can meaningfully immerse themselves in and build on music as cultural outsiders and earn respect from the community they appropriate from.

Unlike today, cultural appropriation was seldom discussed ten to fifteen years ago, when Akal�� Wub�� and other foreign groups started performing Ethiopian music. The term was mostly limited to academia and did not carry as much stigma as it does today. Then, ethnomusicologists analyzed how non-Western music was recontextualized in the West. For example, Herbie Hancock was scrutinized for appropriating Hindewhu, a single-pitch flute tune from Ba-Benz��l�� Pygmies, with a beer bottle, and Madonna was reproached for sampling Hancock���s appropriation. Decades later, popular debates around cultural appropriation resurface frequently and intensely. Rawiya Kameir argues that, ironically, such discourses have appropriated cultural appropriation from its academic context. But regardless of how one thinks about the issue, it remains the lens through which artists like Akal�� Wub�� are often scrutinized.

Critiques of cultural appropriation are often voiced based on ethical or aesthetic concerns. Aesthetically, critics say, cultural outsiders can produce inauthentic art, since ���the ability to use a style successfully is linked to participation in a culture.��� Critics with ethical concerns look at cultural appropriation as theft, an instance of a powerful group capitalizing on the artistic expressions of a less powerful group. Or they see it as offensive, since artistic expressions by minorities enter the mainstream stripped of context in a manner considered unintentional or sacrilegious. As music critic Ralph Gleason has said, ���whites diminish [blues] at best������an aesthetic objection������or steal it at worst������an ethical objection.

Foreign bands that draw from Ethiopian jazz and groove fall broadly into two categories: fusionists and contextualists. The two categories make for different targets, with different ethical and aesthetic cultural appropriation concerns. Fusionists borrow Ethiopian music but provide little or no contextual reference. Examples here are Karl Hector & The Malcouns or Budos Band. In fact, the latter used the Ethiopian repertoire so noticeably in their second album that American-Ethiopian ethnomusicologist and musician Danny A. Mekonnen describes it as original Ethio-groove. But he also criticizes the group for only mentioning this influence in interviews and not in linear notes, where Budos���s music is marketed as the ���quintessence of Staten Island Soul.��� In subsequent Budos albums, the Ethiopian influence is less dominant. To fusionists, Ethiopian music is not an artistic parameter but one of many influences.

Contextualists, on the other hand, own their Ethiopian context and seldomly, only carefully, fuse it with different genres. Akal�� Wub�� falls into this category. Other contextualists are Tezeta Band, Anbessa Orchestra, Ethioda, Badume Band, and Imperial Tiger Orchestra. By producing Ethiopian groove under the banner of Ethiopian-inspired artwork, Amharic titles and album names, and context references in descriptions, they point listeners to the culture they appropriate music from. Contextualists cover Ethiopian compositions but also write original Ethio-groove. Degabriele from Akal�� Wub�� told me that the band had many debates on how to adopt the music while keeping the essential Ethiopian modes. Some of Akal�� Wub�����s rearrangements draw from more modern funk influences and occasionally psychedelic rock.

Ethiopian musician Girum Mezmur told me that just like foreigners��� backgrounds influence their music, Ethiopians also make numerous adaptations. According to Mezmur, Ethiopians ���do not perceive [Ethio-groove as] pure [when performed] in a certain way and [im]pure in another.��� He thinks the musical quality of foreign Ethio-groove can vary. Akal�� Wub�� has ���impressed��� him, as they ���are careful how they have reinterpreted Ethiopian pieces ��� with a [regard] for the original music.���

To Mezmur, foreign and Ethiopian influences each bring advantages and disadvantages to the music. Ethiopians know the context better, he says, and have grown up with the music, which provides them with cultural insight that can be helpful���but also limiting. He also does not express moral objections to bands like Akal�� Wub��; instead, he considers it ���a good thing��� that Ethiopian music has been getting considerable attention abroad. If foreign bands take the genre seriously ���and respect it,��� he says, they deserve to perform.

As a respected musician of Addis Ababa���s 1960s and 1970s generation, Girma Beyene likely would not have recorded and performed with Akal�� Wub�� if their music did not meet his aesthetic requirements, or if he considered their music to be inauthentic. Mahmoud Ahmed, another veteran, and Melaku Belay, a renowned contemporary artist and promoter, have also performed with the band.

Ethio-groove contains musical components that can be traced back to religious and traditional Ethiopian contexts. This could, according to the relevant cultural appropriation objections, offend Ethiopians. However, here in Ethiopia, the initial sacred-to-popular transition was first done fifty years ago, by Ethiopian artists who fused Ethiopian Orthodox liturgical chants (and other elements) with funk and jazz. Mulatu Astatke is a devout Ethiopian Orthodox Christian who researched old church music and instruments, purposefully appropriating them for his fusion work. He created his fusion abroad, clearly stating that his music draws from various non-Ethiopian sources, and his first band members were Puerto Ricans.

Akal�� Wub�����s discography stands on the shoulders of such Ethiopian musicians, who thoughtfully injected traditional and religious musical elements into a transnational popular genre. Ethiopian and non-Ethiopian fans of this type of pentatonic groove are grateful to Akal�� Wub�� for their appropriations. Going forward, the quintet may still occasionally back Girma Beyene, like coming August in Crozon, France, but will no longer arrange and record music and instead work on new projects.

April 6, 2022

A question of color

Bulawayo Street Life. Credit Julien Lagarde via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Bulawayo Street Life. Credit Julien Lagarde via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu���s 2018 novel, The Theory of Flight, takes place in an unnamed country and features a main character, Genie, who has fantastical beginnings. Genie wasn���t born; she hatches from a golden egg and dies by ascending above the clouds on silver wings. Though the setting is unnamed, it is obvious that Siphiwe is writing about Zimbabwe. As the judges of the 2022 edition of the Windham Campbell Prize described her this month, ���Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu is both a chronicler and a conjurer whose soaring imagination creates a Zimbabwean past made of anguish and hope, of glory and despair: the story of the generations born at the crossroads of a country���s history.��� Siphiwe is from Zimbabwe���s second-largest city, Bulawayo, and this is where a lot of the action of the novel takes place.

Siphiwe studied screenwriting in a US college and has a postgraduate degree in film. Her short film, Graffiti, has won film prizes such as the Silver Dhow Award at the Zanzibar International Film Festival in 2003. I have interviewed her before, discussing the Afrofuturist themes in The Theory of Flight (this was her first novel; her second is The History of Man). But this time, what interests me is how she writes about race in Zimbabwe in The Theory of Flight. I was struck by one character in particular: Vida, or Jesus, who is Genie���s great love. He is what is known in southern Africa as ���coloured������shorthand for a person of mixed race, though it points to a more complex history than just mixing. In a video interview with Siphiwe about The Theory of Flight, English professor Tsitsi Jaji, who is also from Zimbabwe, said about Vida/Jesus: ���I have to say: I have never read a novel that took a coloured Zimbabwean seriously, as [someone with] a rich and complex inner life as well as social life, [like The Theory of Flight does].��� The interview explores these themes.

Sean JacobsDo you think that The Theory of Flight���s combination of myth and actual history, especially postcolonial history, makes it possible to emphasize and complicate all kinds of Zimbabwean racial and ethnolinguistic identities?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuI think being absolutely honest about Zimbabwe���s actual history is what makes it possible to show the complexities of Zimbabwean identity. If anything, I am writing against the nationalists��� myth of an uncomplicated nation���a nation whose people are encouraged to think about and discuss difference in the simplest of terms (black versus white, ethnic group A versus ethnic group B, etc.). But in order for this [mythological thinking] to happen, history���actual history���has to be misrepresented, mistaught, or simplified. Because history���actual history���never results in anything that simple. History���actual history���is extremely messy and complicated and often brutal, violent, and ugly. History���actual history���is about change, change that is the result of contact and encounter ��� and there is power at play in every contact, ��� in every encounter. But that is exactly what we inherit: this messy, messy, knotty thing. So our desire to simplify it makes sense but does not lead to honesty. I do not particularly relish having to agree with Hegel on anything, but I do agree with his dialectic; once A encounters B the result is something new and different���it is change. In my work, I am trying to be honest about the changes that have happened throughout the country���s history and how these changes have impacted, and in some cases even created, particular ���Zimbabwean��� identities.

Sean JacobsWere you surprised by Tsitsi Jaji���s comment that coloureds are missing or treated superficially in novels or fiction about or set in Zimbabwe?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuI was not surprised, no. At the time I published The Theory of Flight, I had only read one novel that focused on the experiences of coloured Zimbabweans: Paul Hotz���s Muzukuru. That novel really helped illuminate for me some of the experiences that coloureds in then-Rhodesia had during the war.

I have recently read Violette Kee-Tui���s wonderful Mulberry Dreams, which presents us with the social lives of coloured Zimbabweans. I am sure there are other books���or, rather, I hope that there are���which highlight different aspects of the coloured experience in the country. Zimbabwe sorely and desperately needs a diversity of voices and representation in its literature.

Sean JacobsWhy do you think there is so much silence about mixed-race or coloured people in Zimbabwe?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuI think there is so much silence about mixed-race or coloured people because to talk about mixed-race or coloured people would be to talk about the many messy things in our actual history. We would have to talk not only about the colonial encounter and the violence it visited upon the black body���though actually, this is something that we have been taught not to have a problem discussing because it falls neatly into the oppressor versus oppressed category���but also talk specifically about the violence visited upon the black female body.

The difficult thing here is that we also have to make room for love. Not all encounters were violent���there are love letters in the archives that tell this story, letters confiscated by a colonial system afraid of losing face and eager to hide certain truths. But the idea of love is complicated here as well. If the white man exists in a system in which he has all the power, is it love or coercion? How much choice and agency can a black woman be seen to have under the circumstances?

All these complexities tend to silence the tongue, but I think what silences it even more is the treatment that mixed-race or coloured people had to face. In the early days of the [colonial] encounter, you could actually have racially mixed families, but that did not last long���settler colonialism and its very binary understanding of the world and its peoples could not let it. Families were torn apart. White fathers [were] made to not be directly responsible for their offspring by anti-miscegenation and racist laws; black mothers were made to bear the brunt of both colonial and traditional patriarchies��� very narrow and myopic sexist ideas about unwed mothers; and mixed-race children were forced to exist in a liminal space, never quite being either or.

All this led to a deep sense of shame���and shame often leads to silence and silencing. For a while there, Southern Rhodesian coloureds preferred to have Cape Coloured roots (whether real, imagined or manufactured). But while Cape Coloureds had definitely come with the settlers (working as drivers, porters, etc.), they were not the sole root of Southern Rhodesia���s coloured population.

Sean JacobsJust to clarify for readers, the term ���Cape Coloured��� is used to distinguish coloureds from Cape Town and surrounds from the rest of South Africa and the region; it is also where most people deemed ���mixed��� live in South Africa and Southern Africa and comes with a certain cultural capital in terms of politics of belonging ���

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuAnd because nothing stays the same, there was a time when settler colonialism realized it could use the coloured community to create something of a middleman, and to this end focused on educating coloured children to act as such���even if educating them meant forcibly removing them from the only homes and families they had ever known. Again, families were torn apart. As a result, in segregationist Southern Rhodesia, four races were created���white, coloured, Asian, and black���and a racial hierarchy was established. Within this hierarchy, relations between the ���races��� were erased, so when independence was attained in 1980, it became easier and more expedient for those who now had power���the blacks���to be silent about that relationship as well. Silence is evidently preferable to acknowledging the messy, messy, knotty history we have inherited.

As the above shows, whites, blacks, and coloureds themselves have played a part in creating the different silences about the coloured and mixed-race experience in the country.

Sean JacobsHow did you go about constructing Vida or Jesus? What was your research process like, and did you unearth anything surprising?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuAfter the war, when my family returned to the newly independent Zimbabwe, we settled on a beautiful smallholding on the outskirts of the city of Bulawayo, called Rangemore. It had been, under Rhodesia���s segregationist laws, a coloured zone. We were one of the first black families to move in and it was in this community that I spent my formative years.

I lived in Rangemore but attended a school in the city: Coghlan Primary School. I would board the bus from the city to Rangemore at City Hall. And at the bus terminus at City Hall, there was a former Rhodesian Forces soldier who wore his military fatigues and was christened Jesus by the denizens of the city.

All of this is to say: I did not rely on research to construct Vida/Jesus; I relied heavily on memory.

Sean JacobsIf I think of scholarship on coloured Zimbabweans, I think of the work of Ibbo Mandaza (whose study, Race, Colour and Class in Southern Africa, also included Zambia and Malawi) or James Muzondidya. But those are at least a decade or two old. Did you come across more recent scholarship?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuYes, you are right; scholarship on coloured Zimbabweans is scanty at best, and while the works of Mandaza and Muzondidya are seminal, there definitely needs to be new scholarship.

I have appreciated coming across personal and social histories���a particular favorite autobiography is The Other: Without Fear, Favour or Prejudice by Judge Chris N. Greenland and Palmira R. Greenland, but that too is now more than ten years old.

Sean JacobsIs it coincidental that Vida is also the character that at first, when he enjoys professional success as an artist, is deemed perfectly postcolonial (���a truly postcolonial artist���), then later is classified as ���too white��� by those in power? Is this the fate of the mixed-race or coloured person: that he or she is never enough?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuI think it is the fate of most ethnic minorities to be used as pawns in the game of politics. I think when it is convenient, as it was at a certain point during the colonial era, then coloured people are seen and counted, and when it is not convenient, as it has been for most of the postcolonial moment, then coloured people are not seen or counted���that is, made to matter politically. They are treated as expendable entities, which makes their position in society extremely precarious.

In the novel, Vida enjoys his moment of fame and is politically recognized, because The Man Himself [the president of the unnamed country] wants to be seen as cosmopolitan, open-minded, anti-racial, etc. But when that image is no longer the one that will give him the most political capital, he eschews it and Vida along with it.

Sean JacobsIn 1965, Beatrice Beit Beauford, who owned the farm where the main character Genie was born, gave birth to two coloured twin boys, ���flouting the state anti-miscegenation laws.��� As a result, the white state decided that whites like her who slept with blacks could not be trusted. Is there a long history of the British, Rhodesian, and then Zimbabwean states preventing the races from mixing?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuYou cannot establish a narrative in which one race is inherently superior to another and then allow the races to mix���that would be antithetical and reveal the very lie at the heart of the narrative you have created. Now, of course, as I have already mentioned in an earlier answer, the races mixed. But all things are never equal, and the ���acceptable��� mix was the one between a white man and a black woman. So while there were anti-miscegenation laws, the black female body was rendered oversexed and, therefore, unrapeable and always already dangerous. This meant that whatever white men did to black female bodies, they were never held accountable.

The same could not be said of black men where the white female body was concerned. The white female body, especially in the colonies, was written or seen as pure and virtuous���the complete opposite of the colonized female body. To keep that virtue intact, there were fears of Black Peril and Yellow Peril. And whereas the white man could get away scot-free for violating a black female body, the same could most certainly not be said about the black man violating the white female body.

So in the novel, when Beatrice Beit-Beauford, a white female, decides to have a relationship with a black man, she is doing so much more than sleeping with the enemy. She is attacking the very foundation that upholds the narrative of settler colonialism���and therein lies her real danger.

Sean JacobsThis interview has focused on questions about race in relation to Vida, but you extend the same complexity to other characters. For example, there is a character who is a state spy, representative of Shona majoritarianism and the violence of the postcolonial state. But even he is humanized and redeems himself. Similarly, there is a character, Genie���s mother, who aspires to be a country singer; she models herself after Dolly Parton. It reminds me of something I read that Dambudzo Marechera once said about Zimbabwean literature: ���If you are a writer for a specific nation or a specific race, then fuck you!��� I think you successfully avoided that trap. Was that your intention?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuYou���ve got to love Marechera! I absolutely agree with him, although I am sure that my Lutheran upbringing would make me express myself very differently. Yes, it was definitely my intention to portray my characters as complex human beings. My experience of human beings is that they are incredibly self-contradictory, complicated, complex, and prone to conflict; my experience of fictional characters is that they are incredibly self-contradictory, complicated, complex, and prone to conflict. There are so many different things that make up who we are���some of them are good and some of them are bad. As a writer, I think it is always important to remember, as Dave Mason once sang, ���There ain���t no good guys, there ain���t no bad guys. There���s only you and me and we just disagree.���

Sean JacobsDoes it help that The Theory of Flight takes place entirely ���at home��� and not in locales in the diaspora, the loci of much of the recent fiction with Zimbabwean themes? Does that explain why, despite the novel taking place in an undisclosed country, you get the local nuances right?

Siphiwe Gloria NdlovuI am not sure. I guess the irony is that I wrote 90 percent of the novel while I was living in the diaspora. Perhaps nostalgia and distance gave me 20/20 vision.

April 5, 2022

People live here

Image credit Abir Anwar via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Image credit Abir Anwar via Flickr CC BY 2.0. Since last year, as thousands of Maasai are at risk of being evicted from their homes, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area has been in the news. For decades now, the residence of Maasai in Ngorongoro has been a concern for conservation authorities and NGOs, tourism companies, and the Tanzanian state���all of whom worry that they may be spoiling the natural beauty of Ngorongoro. Although the threat of dispossession has loomed large over Ngorongoro residents in the past, this time the Tanzanian government seems to be particularly serious about resettling thousands of Maasai pastoralists in the name of conservation.

To better understand why the Maasai are perceived as a threat to Ngorongoro, we need to take a look at the colonial beginnings and the postcolonial history of the conservation industry in Tanzania. By resettling the Maasai from the Serengeti to Ngorongoro in the 1950s (where other Maasai had already lived prior to the establishment of Serengeti National Park), the British colonial administration and international conservation interest groups had sought to protect the Serengeti from the pastoralists. In doing so, they promised the Maasai that they would never be evicted from the Ngorongoro highlands. At the time, the irony of protecting the Serengeti from the people whose land use and environmental conservation practices had led to the very creation of the famous Serengeti plains was apparently lost on the colonial administration and Western conservationists such as Bernhard Grzimek.

To European colonizers, resettling the Maasai was not only good for nature conservation, but for evicted populations themselves. To this day, people living around protected areas in Tanzania continue to experience a deeply paternalistic treatment by the state, which perceives them as backward and in need of modernization and development. The state has mobilized the colonial discourse of a civilizing mission whenever Maasai or other pastoralists are resettled in the name of ���conservation��� and ���development��� in Tanzania. While this colonial legacy persists today, what has changed since the end of colonial rule is the paramount role of the tourism industry in present-day Tanzania.

When Tanzania���s world-famous protected areas were initially created, tourism was hardly developed as an economic sector and poorly integrated into the global tourism industry. What is more, in socialist Tanzania under Nyerere, the role of tourism was hotly debated and deeply contested, as Issa Shivji���s 1973 edited volume Tourism and Socialist Development demonstrates (it is unfortunately out of print today). Should Africans endure the ���extremely humiliating subservient ���memsahib��� and ���sir��� attitudes��� in order to ���create a hospitable climate for tourists��� in return for foreign exchange? Can, in other words, the economic promise of tourism outweigh the price of ���cultural imperialism���? These were central questions 50 years ago���questions that seem almost entirely out of place today.

Since the liberalization of the Tanzanian economy beginning in the 1980s, the state has worked closely with western conservation NGOs, donors, and private tourism companies to grow the tourism industry in the country. Today, tourism funds conservation projects across the country and is a source of wealth and power for Tanzania���s political and economic elites. In 2017, Ngorongoro alone was visited by almost 650,000 tourists and generated around 56 million USD in entry fees. Before the pandemic, the direct and indirect contribution of tourism to Tanzania���s GDP was almost 11 percent, and the tourism industry was Tanzania���s largest source of foreign exchange.

Nature conservation has thus become economically unsustainable without a vibrant international tourism industry. At the same time, tourism depends almost entirely on the conservation of Tanzania���s flagship species���most prominently its elephants and lions���in some of the world���s most famous protected areas, such as the Serengeti and Ngorongoro. It is this conservation-tourism industrial complex that offers Tanzania���s political and economic elites the justification to continue threatening rural people with eviction and resettlement. The more successful Tanzania���s tourism sector is, the more the state desperately tries to protect its cash cow from any potential risks. Tourism has thus become a trap. The state cannot live without it, while some of its people suffer from it.

Due to this questionable role of tourism, the state treats rural people living around protected areas as conservation subjects whose contribution as citizens is primarily judged in relation to their value for the conservation-tourism industrial complex. Through tourism ads and brochures, the Maasai are visually represented and celebrated as exotic conservationists when they attract more tourism. When it undermines tourism potential, however, they are vilified through media campaigns. Ultimately, state and conservation authorities see any group whose land use practices are perceived to threaten the generation of revenues from international tourism as economic saboteurs. In Ngorongoro, once people were perceived as a threat, a slow process of marginalization and ���stealthy dispossession��� was set in motion to render their land grabbable and local people relocatable.

We should not overlook���or worse, dismiss���this patronizing relationship between the rent-extracting state-conservation-tourism nexus and its rural subjects when we discuss environmental conservation issues, when we are concerned about the state of wildlife, or when we consider the next trip to protected areas in Tanzania. We should not overlook, in other words, how ���tourism perpetuates a colonialist political economy in a postcolonial world.��� Tourists who visit Tanzania indirectly contribute to strengthening this status quo and thus bear some responsibility. Whether they agree with it or not, international tourists visiting Tanzania���s world-famous protected areas are complicit in this politics of conservation.

What, then, can be done? Grassroots efforts from Tanzanian civil society to stop the evictions should be supported. Environmentally minded people could reconsider their donation practices and stop funding conservation organizations that���directly or indirectly���support the fortress conservation model in Tanzania and beyond. People considering visiting Tanzania as tourists can also do their part by demanding that tourism operators present Tanzania as a country populated by people and wildlife, not as an unfenced zoo whose violent history of evictions remains invisible in curated and sterile safari experiences. Tourists can also consider boycotting protected areas whose operation and conservation is bound up with the dispossession of people living in or around these areas.

April 4, 2022

The art of football

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��.

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��. In the lead up to the 2014 World Cup, held in Brazil, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosted Futbol: The Beautiful Game. Though the art world long held a fascination with football and football art (think, for example, Andy Warhol���s famous painting of Pele), that show, curated by Franklin Sirmans, mainstreamed a growing interest in curating shows about sports, particularly football. Since then, football as art or football art has grown in popularity and around the world. In South Africa, for example, there have been large-scale exhibits focused on football art, but they either resemble trade shows or prioritize social history. Which is where Exhibition Match, comes in. Curated by Phokeng Setai and Alex Richards, it consisted of three elements: the site-specific exhibition; a football match; and a club lounge. The exhibition ran between February 16 and 28 at A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town. Setai and Richards now want to replicate the exhibition elsewhere in South Africa and beyond.

Sean JacobsHow did you both come to your interest in football and art, or football art? Tell me about the genesis of the project.

Phokeng SetaiOn a personal level, you could say that football art and art-football have been formative outlets for me in my socialization as a being in the world. These two elements are still central to the person I am today. One (football) is a hobby, the other (art) an occupation so to speak; only because the labor that I produce revolves around the sphere. But I could say that they���re both a lifestyle for me. Alex and I are Arsenal Football Club supporters and we also share a keen interest in the visual arts, not to mention the fact that we also work in the art sphere, albeit in different roles. We share a common interest in both fields and were led to create a project where the two things we absolutely love could be in conversation.

Alex RichardsI have loved and played football since I was young and grew up in an art-world household, so it is a marriage of two things that I have always connected with. The genesis of the project was a realization of just how many people in the arts love football. Often, conversations at exhibition openings between my colleagues and I were about the sport. There was then a moment where we recognized the similarities between the two spheres. That���s when the show and match idea became more concrete.

Sean JacobsCan you talk us through the different elements of Exhibition Match and what you wanted to achieve with each of them���that is the exhibition, the match, and club lounge��� as well as these together as a unit?

Phokeng SetaiThe exhibition component was as much an expression of our fascination and deep engagement with visual culture, as it was about showing preexisting conversations between the two worlds. From the beginning we saw the match as the main event. I saw it as a moment for theater to occur, where we could lean in into the performative aspects of spectacle that the art world so loves and fetishizes. But perhaps more importantly, for me, it presented itself as an occasion and opportunity to create cohesion; a moment to be in community with each other. To a very large extent I consider that intervention to be an attempt at creating a social sculpture. Whatever that means and whatever possibilities it opens up for creating solidarity in our ecosystem and beyond.

Alex RichardsThe exhibition was quite simple: trying to source as many artworks that related to football as possible (preferably with a South African focus, though this was also out of logistical and financial limitations), from which a thread of team and individual or team vs individual was extracted.

The match was actually the core idea of the project. The past few years have been very isolated���no parties, no travel, not much physical human interaction. So that���s why the timing, the first physical local art fair in two years, felt right. The match also allowed people to come together who usually don���t. We had artists playing with other gallerists and art writers playing with art handlers. This type of opportunity for connection across the art world is rare and we think enriching.

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��.

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��.The members lounge was organically arrived at. A4 Foundation���s�� project space has a small, enclosed area with a lot of mid-century furniture which feels nostalgic, just as with many club lounges, and we thought this would be a great space to house some of the personal archives generated as part of the show, due to its intimate setting and familiar feel. Playing with the idea of a club lounge or using a trophy cabinet aesthetic in a usually art-specific space felt appropriate for the project. In the lounge we had a Playstation console set up���this is because the actual field we were going to play the match on was a venue to play a virtual game on FIFA 19. This felt like a good way to introduce the idea of the physical match into the members lounge and to continue the nostalgic feel (for people my age, playing FIFA was a favorite pastime) while still connecting it with what was to come���the physical game.

In terms of how they all work together, I had been thinking a lot about what my personal curatorial language was and I settled on the idea of experience���in the sense of�� active participation by the visitor. The connection and combination of all three aspects felt like the best way to appeal to the different types of people we wanted to appeal to: something known (exhibition), something remembered (lounge) and something new (the match).

Sean JacobsWhat was the relationship between the offline and online, particularly Instagram, aspects of Exhibition Match?

Phokeng SetaiOur Instagram served the purpose of something akin to an online exhibition. It gave us the possibility to connect the local to the global and demonstrate to our public(s) that these connections are not only real, but very cultural too in how ubiquitous they are.

Alex RichardsThe Instagram account was important for a few reasons. The first was we needed to get the word out and to have a central space from which to contact any participants or to generally engage with the public. Its visual nature also allowed us to post images from the show, but also from all over the place in an attempt to garner more engagement. The main reason was we needed a place to house our People���s Archive���as some elements were video and not object based, and not available to us. Neither of us are deeply into social media but we found the prospect of having another curatorial space exciting. The Instagram page itself is like an advert for the project as we would like to grow it. The platform seems the most accessible and has the ability to be a living archive.

Sean JacobsYou mentioned elsewhere that through Exhibition Match you figured out ���… how to create cohesion between members of the larger arts community, in a manner that is devoid of the usual grandiosity and exclusivity that is typical of most art events.��� What do you mean by that?�� What do you think the art community doesn���t get about football?

Phokeng SetaiWe were interested in creating a contact zone, a place of intersection and knowing the history of football as a very popular sport, we knew that it would have the effect of drawing attention to it. Art events, such as art fairs, have a similar effect to football in terms of attracting public interest. The similarities are very stark. In my experience football gatherings do something very different from art fairs and that is creating a togetherness that is palpable but at the same time almost illusory. Despite the latter, we have that feeling of unity and the sense of community that is in the air at sports games as a positive force. After the events of the past two years Alex and I wanted to explore this connection, more especially in the context of the art world, which thrives on creating conditions for individuation to occur.

Alex RichardsReading it back it seems like a bold claim. What we mean is that there are certain barriers that are set up between members of the art ecosystem, be these in the general workplace with its hierarchies, spatial divisions, and the feelings of exclusion that are often generated. A football match is something that feels accessible and what people might be more familiar with than a typical exhibition opening.

Sean JacobsI really liked the living room set. Can you say what you wanted to convey with it?

Phokeng SetaiWe envisioned the living room in general to be a space for play. A space that could simulate that feeling of waiting for the ���big match��� to start. When I think about it now, the living room was a site where play, excitement and embodied lived experience came together. All expressions that art and football are able to elicit in their actors.

Alex RichardsI mentioned it a bit in my earlier answer. A mix of nostalgia and a space to show artworks in a context that they aren���t usually seen in. Equally, a space to show objects and thoughts from the People���s Archive in a space more true to how they might be shown in the real world or their natural setting. The idea was to convey comfort.

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��. Sean Jacobs

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��. Sean Jacobs You mounted the exhibit in a city, Cape Town, known for its antipathy to football. But also the city���s elites, especially the white elites and its new multiracial elites, prefer rugby. These elites are almost exclusively the products of the country and the city���s elite universities and schools and prefer rugby. Rugby connects South Africa with Britain, the English world, and Britain���s other former settler colonies. By contrast, football in South Africa is a working-class sport and connects Capetonians and the rest of South Africa with Africa and with working-class cultures in Europe and the rest of the world. It is not the pastime of the art world. Is that a correct assessment?

Phokeng SetaiTo a large extent, I would say that you���re right, football is more of a game that is accessible to the working-class masses, especially in Africa, than I would say rugby is. This is why I think it was the perfect mediator for us to intervene into the modes of circulation associated with the art ecosystem. Especially during an exclusive art-world event such as the art fair, which structures itself around reproducing these class and gender-based inequalities.

Alex RichardsCape Town is notoriously a complex place, particularly in relation to how it sits in the context of South Africa and Africa. Both Phokeng and I aren���t from here���I am from Johannesburg and he is from Bloemfontein. But we both now find ourselves here as arts workers, and thus it was the practical place to begin the project. But, I think we will both agree that this city wouldn���t have been our first choice for the reasons you describe. This being said, on the ground, football is played all over the place in Cape Town, from manicured indoor football centers, on improvised large outdoor fields and by children on the side of the highway. To disregard football in Cape Town because of what Cape Town represents would be unfair. There are also two teams in the PSL from Cape Town���City and Stellenbosch (ex Vasco De Gama)���the latter being an interesting case study of an essentially Afrikaans region and symbol, now represented by a black majority team. There is also the story of Chippa United���now based in Gqeberha, but originating from Nyanga on the outskirts of Cape Town.

I also think football is something that connects South Africa to Britain in a way that is not just elitist.�� There is a massive following of the English Premier League here, which I think happens throughout the continent. One thing I have always been interested in is the fact that South Africa speaks UK English and uses the metric system, yet we call it the game soccer. This might be an indication of exactly what you are speaking about: rugby as football is the focus, the other football can be called soccer.

Sean JacobsOn Instagram, you included an image of a local Cape Town club, Saxon Rovers, winning the Rushin Trophy in 1953. To any close observer, this points to segregated football in Cape Town. How much did the exhibition engage with the racial political economy of the sport in Cape Town?

Phokeng SetaiThe images of the Kensington-based team, Saxon Rovers, came in as a submission from a member of the public whose family history is connected to the team. This, for me, was the success of that archival component we integrated into our exhibition���s online editorial (i.e. Instagram). It enabled us to solicit these kinds of narratives/histories that otherwise would not have come out. I believe that in learning about these histories, which particularly have to do with Black/Brown lives, and creating an outlet for them to be known, we are rewriting the history of the political economy of football in Cape Town, albeit in a very small way. Those who didn���t know will now get to know.

Alex RichardsThis was a submission to the People���s Archive by Tammy Langtry, a curator currently based in Johannesburg. Members of her family founded the team in 1953. We engaged by attempting to have as varied voices as possible, with the hope that the good, the bad and the ugly about the sport would reveal itself through personal experiences, going beyond the curatorial framework. I suppose because the focus was on the relationship between art and football it is something we could only touch on explicitly, but implicitly all those relations are also laid out. For example, the member���s lounge was located inside an institution in the CBD;�� however welcoming and public facing this is, it still presents a near-insurmountable barrier for some. In the racial political economy of the exhibition is the story of the racial political economy of football and the racial political economy of art. The match we played had participants from across the city���people of different backgrounds and income brackets. Overall, this was the first iteration of the project. I think moving forward a deeper engagement with the host city, its past and its complex stories would provide a great generative opportunity.

Sean JacobsYou were inspired by or took advice from Franklin Sirmans, who was responsible for the Futbol: The Beautiful Game at LACMA in Los Angeles in 2014. How do you think this relationship between galleries and museums with football as art or football art has changed since then?

Phokeng SetaiIn my opinion, and from what I have seen in the course of doing research preparing for our exhibition, there has been very little absorption of this trend on the African continent. I cannot speak for other contexts because I am not so well versed in their dynamics in the same way as I am about the African continent. There is a huge disconnect that exists between the fields of art and sport, not just football. I would personally like to see more confluence between these two cultural genres. To answer your question: there has been minimal change, if any, and I would love to see more because I think together these two components could ignite real cultural change if instrumentalized well.

Alex RichardsWe wanted to speak to Franklin first and foremost because of his love for football. This was key to the project as a whole���trying to connect as many football-loving art world people as possible. Like most projects, you look at what came before you, and his show stood out. I am not sure how much the relationship has changed between institutions and football/art other than maybe an increased awareness of the amount of artwork speaking to football, as well as the sport���s potential to be a metaphor for�� other urgent ideas. We know football and art are both deeply political, yet this aspect is often underplayed in promoting both as fun or entertainment. It���s possible that this seemingly simple nature of the two could be used to engage, answer, or discuss bigger societal questions. I would also think that the subject of football might attract a different audience to a museum, particularly a younger audience.

Sean JacobsHow do you react or interpret something like Serie A club Napoli���s decision last year to commission artist Guiseppe Klain to design a limited edition Maradona ���fingerprint��� shirt, which they wore for only three matches?

Phokeng SetaiI didn���t know about this collaboration before reading this question. Since then, I read about it and looked up the jerseys that were produced. It is amazing to see and I am starting to notice more of these synergies between art and football now that I am sensitive to them. It is very nice to see, because both football and art-making are expressive modalities. This is what makes them very similar. Just thinking of kit and boot design and creative outlets such as that; these roles have been existing for a long time. Exhibitions such as ours definitely help put a microscope on these functions and how they converge in the different fields, so to speak.

Alex RichardsI think the idea is positive, in the sense of having artists design football kits. Our own kits were designed by Dada Khanyisa (within the limitations of a kit-building program). I do think this particular idea by Napoli wasn���t great conceptually or very interesting aesthetically.. The fact that they only wore the kit for three matches interests me in its similarity to an editioned artwork���limiting its number of times used may supplement or create commercial value through that very scarcity. In general, I am interested in the commerciality of a kit and the consequent issues with sponsors. I think of the Gazprom sponsorship and the subsequent removal of ���3��� on the Chelsea kit and the removal of betting companies in Spanish football. I prefer kits without corporate sponsorship. The fact that kits change every season is surely very commercially motivated, but also provides greater opportunity for collaborations like the one you mention.

Sean JacobsOn Instagram, you featured an Andy Warhol painting of Pele.�� Sport as pop art is well established in the global north? What is that history like on the continent? Can you point to some markers, if any?

Phokeng SetaiAbsolutely! This trend exists on the continent too. When I think of the football fandom phenomenon I can���t help but see the numerous examples that exist, and this is but one angle. In the same breath we can talk about players such as Teko Modise, who was sponsored by big multicultural companies, and that highlights the culture of players being sponsored by football boot suppliers, such as Adidas and Nike, which have a big pop-cultural appeal. Another famous example of this is Benny McCarthy creating a song with TkZee that became a classic tune that, to this day, gets the masses going whenever it plays. To be fair, there are so many examples it���s very difficult to decide which ones to include and which ones to exclude.

Alex RichardsI think something like the hairdressing signage we featured could be an example. Where famous footballers haircuts are offered to clients and their image used as a model. I���d argue that portraits of footballers on the sides of shops next to items to purchase could be seen as both pop art and advertising. I do think that the love for public murals of football stars on the continent is important. I think to some extent Makarapas in South Africa could be seen in this way too.

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��. Sean Jacobs

Exhibiton Match, 2022, Courtesy of A4 Arts Foundaiton ��. Sean Jacobs You include one image by David Goldblatt: ���Drum majorette, Cup final, Orlando Stadium, Soweto. 1972.��� You mention on Instagram that Goldblatt ���… took another photograph on that day���one with a slightly more sinister edge, a policeman���s German Shepherd is the focus as a reminder of the times��� and that ���(i)n 2009 Goldblatt also photographed the refurbished FNB Soccer City Stadium with the ruins of Shareworld in front of it.��� Is minimal or sparse engagement with football by South African art photographers (not news photographers) unusual, or par for the course?