Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 104

March 18, 2022

Does class matter?

Soweto, South Africa (Image by Marc St on Unsplash).

Soweto, South Africa (Image by Marc St on Unsplash). On this week’s AIAC Podcast, we chat with Professor Vivek Chibber about his latest book, The Class Matrix: Social Theory After the Cultural Turn. Why, despite the powerful antagonism capitalism generates between bosses and workers, is it so resilient? Why did class disappear as an analytical category for the international left? Can the left rebuild class consciousness through organizing, or are the multiple crises the world faces too insurmountable and the obstacles to organizing too great?

Vivek Chibber is a Professor of Sociology at New York University and the author of Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital and Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India. He is a contributor to the Socialist Register, American Journal of Sociology, Boston Review, the New Left Review and Jacobin. He is also the editor of Catalyst: A Journal of Theory and Strategy.

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/eda779e0-a9b7-47a5-adb4-da9c68dd2af0/aiac-talk-why-class-matters.mp3March 17, 2022

The future we’ve promised our girls

Image credit Chantal Rigaud for the Global Partnerhsip for Education via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Chantal Rigaud for the Global Partnerhsip for Education via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. In the wake of Malawi���s 16 Days Of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, we need to consider all the less outwardly violent���but nonetheless oppressive���ways that we deal with women and girls in Malawi. These practices make it such that gender-based violence (GBV) is not an exception to our ways but, ultimately, a necessary, defining rule. If we consider as violence not just physical and sexual abuse and assault, but emotional and psychic damage that is specifically gendered���directed against women and girls simply because they are women and girls���then we may start to better understand the roads by which the more explicit forms of GBV travel and eventually manifest. Litigating in favor of the humanity of our girls and women cannot and should not start in the courtroom, after obvious crimes have been committed; it must start before, within the foundational expectations of their lives.

Take the example of Grace, one of my many nieces from my mother���s village. She is seven years old; whip-smart, talkative, confident, and thoughtful, she is quick to identify things that don���t make sense and then equally quick���on account of her intelligence���to take advantage of those same nonsensical things if there is something to be gained from it. Being as young as she is, she is still physically confident���she plays hard, she roams where she likes, she takes up space and believes she deserves to. With the right resources and societal structures in place, Grace might have a limitless future in front of her: the ability to make the greatest use of her character, gifts, and skills to build exactly the future she wants for herself and even to surpass her own expectations. If she were a boy, we would have no question as to the brightness of the future ahead of her.

Except Grace profoundly understands the system she is in, and at seven, she is resigned to it in a manner far exceeding her small age. (Sometimes, I think her preternatural wisdom is where the inexplicable spackling of white hair a couple of inches above her right ear comes from.) So resigned is she that one day at my mother���s house in Blantyre, she marched to the kitchen while my grandmother���s nurse was making stewed beef for Grandma���s dinner and declared, ���You need to show me how to cook that. When I get married I want to be able to cook that too.��� My mother was horrified when the conversation was relayed back to her by Grandma���s nurse. I think the nurse had thought it was hilarious for a seven-year-old to say something like that; my mother didn���t. ���A seven-year-old already talking about marriage?��� my mother said. ���She should be focused on school! Not marriage!���

When I was a young girl in Malawi, I did what I was supposed to���worked hard in school, did well in all my schools here and abroad, eventually moved out of my parents��� house to strike out on my own. Despite making my own life, I am nonetheless increasingly under familial pressure, mostly from the family���s elders, in exactly two respects: to find a husband so that he can take care of my mother, and to leave my life abroad behind, move back home, and keep my mother company, especially since she lost her husband���my father���three years ago. Yet when I���ve tried to explain that I work abroad now in order to make sure I can support my mother in the way she���s accustomed to later, I���m met with blank stares. And I haven���t even dared to explain that I don���t plan to abdicate responsibility for the eventual care of my mother to a stranger to my family, even if in the form of a husband, simply because he is a man.

So was Grace really wrong, then? ���Work hard in school,��� we tell our girls. ���School is good; it will bring good things to you,��� we are told when we are young and then repeat to the next generations of girls when we ourselves are grown. Except the dirty little secret is that the only thing school brings our girls is the opportunity to find a better man to marry on the road to becoming fully-fledged women in our society, and by ���fully-fledged women��� we mean women who successfully attach themselves to a man who defines them and then learn how to shoulder the backbreaking yet invisible work of keeping our communities standing with nary an open complaint. Because the truth is that the only thing we as Malawians truly expect���indeed demand���of our women is to tirelessly support the existence of their community���s men���husbands or brothers or uncles or sons���whether or not that effort is earned by or returned from those same men.

Do we truly expect our girls to work hard in school, then, or to work hard in the service of our men? What is the point of telling a girl to work hard in school, to focus on her studies and not men, if the fact of her having gone to school ultimately won���t matter in our society if she is without a man to underscore her worth? When, no matter how much schooling she���s had, her life���s ultimate destination is always expected to be the same, that she marries and then serves her community with no mind for her own needs until her death? We don���t really want girls educated for their own sake���we want girls whose educations we can talk about like shiny objects we���ve collected, especially if that education was funded by a male relative. If we���re proud a girl went past a high school education, it���s not because we are proud of her intrinsically and excited for the woman she will eventually become. Instead, we���re proud to tell people we have a girl who made it so far, because it makes her more attractive as a man���s future wife.

In a strange way, then, I admire Grace for seeing it so clearly, for having the insight not to bother with a futile fight that will only exhaust her and cause her feelings that her society will have no ability to hold or accept. At thirty years past her age, I am only starting to see the truth���past our billboard platitudes and radio jingles enunciating the worth of women and to the truth that without a man to be attached to or a community I am energetically serving in some capacity, I am societally irrelevant. I can play the game, certainly���I genuinely enjoy cooking, I���m clean to a sometimes annoying fault, I can talk with my mother late in the night about her plans for her retirement without Dad, I can expend time and money coming home twice a year with suitcases full of clothes, books, and gifts for my relatives. I just can���t reconcile myself to the idea that I haven���t done this fully if I haven���t completely erased myself first, whether to my society or to a man.

In a society where girls are trained to gradually become invisible, the violent endpoint of that spectrum is inevitable. We can���t talk about the scourge of GBV, then, without first naming the uncomfortable reality of the extent to which we render our girls and women invisible, treating their lives as though they are worthless without a man to give them value. This all exists on a spectrum: GBV is not just about physical and sexual abuse, but about power and the dynamics of that power within a societal setting. And a man who engages in this kind of violence against women does it not solely because of something broken inside of him that makes him prone to this behavior, but because he subconsciously understands that not even his society considers the female-gendered being in front of him to have intrinsic value worth developing and upholding. Her gender is the basis for that violence, because were she to be of a different gender���his gender���he never would engage in that violence to begin with.

Change the equation and you change the results: start cultivating girls as people in their own right rather than as auxiliary figures to an eventual man���s self-evidently worthy life, start genuinely treating boys and girls in the same ways as they grow up���as deserving of the same degree of investment and worthy of the same kind of excitement about who they are to become, rather than members of one gender being taught cooking and cleaning while those of the other are taken on business trips and later given money to start ventures of their own���and you will begin to see a meaningful shift in the violence, both quiet and loud, that girls and women are trained to expect as their lot in life, especially when they dare to step outside their expected roles. Let us not have this be another thing we pay mere lip service to in order to make ourselves feel good. Let us do more than tell the Graces of the world to work hard in school���let us have a real plan for the fully self-actualized people we aspire for the Graces of the world to become.

March 15, 2022

Copyright is colonialism

DJ Ripley. Image credit Fredric Fresh.

DJ Ripley. Image credit Fredric Fresh. Africa Is a Country Radio continues its literary theme for its third season on Worldwide FM. The fourth installment takes a look at the politics of copyright, and the long history of resistance (or indifference) to that regime from the global margins. Larisa Mann aka DJ Ripley takes a look at the specific case of Jamaica in her book Rude Citizenship: Jamaican Popular Music, Copyright, and the Reverberations of Colonial Power. This episode is essential for anyone who has an interest in music industry futures, from NFTs to streaming and beyond.

We open the show with a selection of (colonial/copyright) resistance music, and DJ Ripley takes us out with a selection of classic jungle and dancehall tunes that inspired her work as a musician and academic.

Listen below, or on Worldwide FM and follow us on Mixcloud.

March 14, 2022

The politics of imperial gratitude

South African Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Lindiwe Sisulu with President Vladimir Putin. Image credit DIRCO via Gov. ZA on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0.

South African Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Lindiwe Sisulu with President Vladimir Putin. Image credit DIRCO via Gov. ZA on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0. The night before he commanded Russian troops to invade Ukraine, President Vladimir Putin gave a speech that faulted Ukrainians for failing to express gratitude and fraternal loyalty to Russia. Bombing Ukrainian cities and targeting Ukrainian civilians is hardly a sound way to evoke thanks or brotherhood, but Putin aims to make the cost very high indeed for spurning Russia���s ostensible friendship. As they respond to the invasion, African countries have had to weigh Russia���s value as a potential friend. Their responses have varied, from Kenya���s condemnation of Russia���s actions to Eritrea���s support for them. South Africa has taken a stance that avoids antagonizing Russia, refusing to name or condemn the invasion while calling for negotiations between Russia and Ukraine.

Putin is not seeking to resurrect the Soviet Union, but to undo what he considers a foundational Soviet mistake: granting a limited degree of self-determination to Ukraine. In attacking Ukrainian sovereignty, Putin expects support from Russia���s allies, including countries like South Africa that are part of BRICS (an association of major emerging economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). The Russian government���s ability to exert pressure has important economic and geopolitical dimensions, but the vocabulary used to solicit support is saturated with history and emotion. Russian generosity in the past, so the story goes, demands South African gratitude and cooperation in the present.

By now, you know the basics: in 2014, Russia annexed Crimea���part of independent Ukraine���and began backing separatist paramilitaries in Ukraine���s eastern Donbas region. In a televised speech on February 21st of this year, Putin interpreted Ukrainian history as a series of lies and betrayals that weakened and manipulated Russia. On February 24th, Russia launched airstrikes in Kyiv as it initiated a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Putin seems to have radically overestimated popular Ukrainian desires for the kind of ���liberation��� on offer from Russia; the tenacity of Ukrainian resistance has stunned the world.

On February 22nd, on the cusp of renewed crisis, South African Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Naledi Pandor called for peaceful dialogue and moving ���the process forward without accusing any party.��� The department���s updated statement on February 24th, which called for a withdrawal of Russian troops, nevertheless refused to identify Russian aggression, instead using the carefully actor-free phrase ���escalation of conflict.��� ���We call on all parties,��� it read, ���to resume diplomatic efforts to find a solution to the concerns raised by Russia.��� Even that mild statement from Pandor���s ministry has raised the ire of President Cyril Ramaphosa and the African National Congress (ANC), who reportedly see it as too strongly condemning the attack on Ukraine. On March 10th, Ramaphosa called Putin and then thanked him on Twitter for providing ���an understanding of the situation that was unfolding between Russia and Ukraine.��� Putin, according to Ramaphosa, expressed appreciation for South Africa���s ���balanced approach.��� Lindiwe Zulu���an alumna of the Peoples��� Friendship University in Moscow and currently the chair of the ANC���s Subcommittee on International Relations���cited the ���relationship we have always had��� as a reason why ���we are not about to denounce��� South Africa���s friends in the Russian government. The ANC continues to endorse dialogue while a war rages. South Africa is to toe the Russian line.

But the past is more complicated than official Russian and South African statements suggest. Here���s a look at what they don���t say.

The Soviet Union���s support for the ANC and South African Communist Party (SACP) in exile is well known. The first black South African to visit the Soviet Union requesting assistance in fighting apartheid was Pandor���s father, Joe Mathews. Reports in Russian archives document his numerous conversations with Soviet officials in the early 1960s. As Matthews later put it: ���We looked at historical analogies and became convinced that you had to have some power or other backing you, otherwise you wouldn���t be able to launch a sustainable armed struggle.��� Between the early 1960s and the late 1980s, the Soviet Union assisted the anti-apartheid struggle with money, arms, military training, education, weapons, diplomatic support, food, books, medical care, international transport, and more.

Today, it suits both the South African and Russian governments���now economic partners in BRICS���to view Soviet support for the ANC and SACP as basically Russian. Yet the Soviet Union was bigger than Russia. In fact, by the late Soviet period, only about half of its population was ethnically Russian. Non-Russian parts of the Soviet Union played important roles in the anti-apartheid struggle as well. Ukraine, especially so.

Ukraine was one of two Soviet republics to have its own representation at the UN (the other was Belarus). While the Permanent Mission of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) by no means had foreign policy independence, Ukraine prominently advocated for measures against the apartheid government. In 1962, with a powerful declaration of support from the Ukrainian SSR, the UN General Assembly recommended stringent diplomatic, economic, and military sanctions against the South African government. Year after year, the Soviet Union supported draft resolutions recommending sanctions, and year after year, Western powers vetoed those resolutions. In 1985, the Ukrainian mission to the UN endorsed comprehensive sanctions against South Africa, stating that ���South Africa���s disregard of United Nations decisions, its illegal occupation of Namibia, its ceaseless acts of aggression, its State terrorism and threats against independent African states, the continual build-up of its military capacity and its plans to produce nuclear weapons constitute a direct threat to international peace and security.��� If you have heard similar language recently, it���s almost certainly been used to describe Russia���s actions.

While ANC and SACP leaders went for specialized political training in Moscow, many outside the leadership studied in Ukraine. Beginning in the early 1960s, several thousand African students came to the Soviet Union annually. Over 30 percent of them studied in Ukrainian institutions. The first cohort of ANC students to pursue university degrees in the Soviet Union began their studies in Kyiv in 1962, and several remained in Ukraine for four more years. On his way to a degree in national economic planning, for example, Sindiso Mfenyana (future secretary to parliament) performed choral harmonies to adoring Soviet audiences, took a boat cruise down the Dnipro River to the Black Sea, and organized informal discussions with students from other national liberation movements. Living in Kyiv, students took note of Ukrainian complaints about Moscow���s policies and attitudes. Mfenyana remembered that ���Ukrainian students in class were quite vociferous about the Ukraine being the breadbasket of the Soviet Union and yet the best of their produce was hardly visible in their shops, but was in abundance in the state capital, Moscow.��� Political activist and scholar Fanele Mbali was also in the first ANC group, studying national statistics in Kyiv. Mbali observed that though Ukraine ���came second only to the Russian Republic,��� ���relations between the Ukraine and Russia were somewhat strained��� due to the proud nationalism of Ukrainian leaders and their sense that Ukraine was feeding the whole Soviet Union without benefiting Ukrainians.

It wasn���t only students who went to Ukraine. Of the ordinary soldiers in uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK, the ANC���s armed wing) who trained in the Soviet Union, most went to Ukraine. Between 1963 and 1965, according to historian Vladimir Shubin, 328 recruits received military training near Odesa, on the Black Sea coast in Ukraine. In the mid-1960s, the Soviet Union opened a training center for guerilla fighters in Perevalne, in the Crimean peninsula. In 1969, after Tanzania expelled MK, the Soviet Union relocated most of the force to Crimea. Many MK veterans fondly remember the local women who cooked and cleaned for them, treating the young soldiers with hospitality and affection. Military trainees were significantly more removed from local society than their student counterparts, and they usually did not learn much Russian. Many made no distinction between Ukrainians and Russians, who were all Soviet white people speaking similarly unfamiliar Slavic languages.

The same Ukrainian nationalists who had made an impression on Mfenyana and Mbali also complained about how Ukrainian contributions to African training and education were undervalued or erased. Instead, Russians absorbed all the status and gratitude associated with Soviet aid. Ivan Dziuba, author of the dissident Ukrainian text Internationalism or Russification, captured this frustration, lamenting that Ukrainians had not ���received a single word of thanks from those Asian and African peoples.��� As historian Thom Loyd has demonstrated, multiple imperial hierarchies overlapped in Soviet Ukraine. Ukrainian nationalists resented Russian arrogance and rejected the notion that Russians were developmentally superior or naturally fated to rule. At the same time, Ukrainian nationalists saw themselves as advanced, European, and worthy of African gratitude.

The premise of Soviet generosity was laced with harmful racial stereotypes. Official and unofficial Soviet culture considered Africans to be backward and poor. In the romantic politics of the early 1960s, Soviet perceptions of Africans as backward encouraged a socialist version of a civilizing mission, in which a benevolent Soviet mentor provided guidance and resources to needy African pupils. Amid the disillusionment of the 1980s, perceptions of backward Africans instead fueled a new kind of prejudice that saw poverty and violence as inherent features of African society that no amount of Soviet education or aid could displace. Popular racism, always present in Russia, Ukraine, and other parts of the Soviet Union, got much, much worse amid the political reforms and economic collapse of the late 1980s.

When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev spoke of a ���common European home��� from 1987 onwards, it was implicitly understood that the Soviet Union was shedding its commitments to the Global South as it turned to embrace the West. Ukrainians voted for independence in December 1991, and the Soviet Union dissolved quickly thereafter. In the Soviet Union���s last years, when popular revolt against apartheid intensified and the South African government instituted multiple states of emergency, Soviet foreign policy did an about-face. Rejecting their previous support for armed struggle, Soviet officials advocated dialogue and negotiated settlement. More radically still, the Soviet Foreign Ministry began to question and dismantle its opposition to the National Party government. Between 1988 and 1991, the intelligence services of the Soviet and apartheid governments developed a cozy relationship. In 1990, the Soviet Union began enthusiastically pursuing sanctions-busting trade deals facilitated by the apartheid government and arms dealer middlemen. In February 1992, after the Soviet Union had finally disintegrated, South Africa established diplomatic relations with post-Soviet Russia. All of these actions infuriated the ANC, which had counted on continued Soviet support.

On February 28th, as attacks on Kyiv intensified, the Russian embassy in South Africa celebrated the 30-year anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two countries. A statement released by the embassy celebrated a long, unbroken history of Russian support for the ANC, from exile to government. The statement carefully omits the period in the early 1990s when Russian governments preferred the National Party to the ANC, as well as the late 1990s when the ANC regarded post-Soviet Russia as a powerless has-been in global politics. It was economic ties, in particular mining interests, that drove the ANC to rediscover Russia. After nearly a decade of delays and cancellations, Nelson Mandela visited Moscow in 1999. ���We received enormous assistance from the Soviet Union, the assistance we could not get from the West,��� said Mandela. ���Russia should have been the very first country that I visited, and I have come to pay that debt now.��� Credit for supporting the exiled ANC accrued to Russia alone among the Soviet successor states.

Russian officials counted on the gratitude of South Africans who had lived, trained, and studied in the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, they were often disappointed. In one instance, Russian arms manufacturers expected the ANC government to purchase Russian fighter jets instead of British or Swedish, a deal which did not materialize. It was only later that Putin���s government began in earnest to cultivate a myth of solidarity among ANC alumni, deliberately obfuscating the enormous ruptures between the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia. Independent Ukraine has had an even more fraught relationship to the Soviet past, and���according to Liubov Abravitova, Ukraine���s ambassador to South Africa���never prioritized building connections with African alumni.

Loyalty to Russia in the ANC���and in the South African government���revived after South Africa���s accession to BRICS in 2010. While its track record is mixed, the idea of a bloc of regional powers standing up to the Western-dominated unipolar world order has had durable appeal. Recent years have seen increased Russian efforts to cultivate relationships on the African continent, including at the first Russia-Africa Summit on the Black Sea in 2019. In 2014, when the UN General Assembly voted on a resolution protecting Ukraine���s territorial integrity, South Africa joined 27 other African countries in either abstaining or voting no. On March 2nd of this year, in light of the recent invasion, the General Assembly again tabled a resolution on Russia���s actions in Ukraine. This time, 28 African countries voted in favor and 17 abstained or voted no. South Africa was among the abstentions.

In the past few weeks, Russian information and disinformation services have hammered on the narrative that Russia is Africa���s loyal friend while Ukraine is full of racists and Nazis. Many of the 16,000 African students who were in Ukraine at the beginning of the conflict have tried to flee to neighboring countries. In transit and at the borders, they have faced serious racial and national discrimination, being���sometimes literally���shoved aside to prioritize Ukrainian refugees. Russia Today, the Russian government���s English language news service, has gleefully reported on racism at the Ukrainian border. Such discriminatory practices have given succor to those who wish to diminish Ukrainian suffering, reinforcing rather than rejecting the Western press���s habit of downplaying the suffering of other dehumanized populations.

Throughout the Cold War, apartheid propaganda���with help from sympathizers in the West���portrayed the ANC and SACP as the Soviet Union���s playthings, puppets and proxies, with no legitimate independent existence. The ANC and SACP demanded recognition for themselves as legitimate political actors and for South Africa as more than just another theater of the global Cold War, rebutting their opponents��� treatment of them as nothing more than a front for Moscow���s superpower ambitions. But recent statements from the ANC and SACP regard Ukraine���s democratically elected government in exactly the same way, only here Ukraine is a front for US-led NATO imperialism. Asked to clarify if the ANC sees Russia as an aggressor, Lindiwe Zulu named NATO as the responsible party for making Russia feel threatened. ���The aggressor is US imperialism,��� argued SACP Deputy Secretary General Solly Mapaila. ���Russia has to defend itself.��� And Ukraine? Ukraine���s existence���and the political desires and interests of Ukrainians���are simply irrelevant to a vision of politics that consists only of bad American imperialists and those who fight back. The suggestion is that imperialism is only imperialism if Americans do it.

To be sure, some justifications for solidarity with Ukraine are flawed. Why should South Africans defend an idea of the West that has defined itself by excluding and subordinating people of color? Why defend an idea of democracy that has offered cover for a series of imperialist military adventures by the United States? One need not endorse these ideas���or all parts of the Ukrainian nationalist project���to express solidarity with human beings who are being shelled in an unprovoked attack. Likewise, there are good reasons to be critical of NATO expansion, and we should evaluate carefully the West���s role in escalating tensions. But Russia���s government bears responsibility for the huge moral leap to initiating this war���a war that may be impossible to win.

In the face of war, ANC leaders appear enthralled by the idea of repaying a historical debt. In addition to fudging a history that is more complicated than meets the eye, this stance plays into a neo-imperial way of thinking. Though Putin���s Russia differs from the Soviet Union in most important respects, one continuity is a powerful narrative of innocence abroad and an expectation that Soviet (then Russian) benevolence would generate gratitude and loyalty among those in need. Gratitude���or the expectation of it���stabilized an imperial hierarchy: Russian givers claimed superiority over and obedience from non-Russian recipients. Wrote the anthropologist Bruce Grant, ���While the gift of empire may ultimately be unilateral, it sets in motion a remarkably effective means of establishing sovereignty over others, hinging on a language of reciprocity that requires little or no actual reception among the conquered.��� From the 1990s to the present, one consistent Russian imperial lament is that non-Russians within the former Soviet sphere and in the world at large are insufficiently grateful for all of Russia���s generosity.

Ukrainians have rejected Putin���s claim to their allegiance. South Africa���s leaders, with much less at stake, have not.

March 10, 2022

Not so quiet resilience

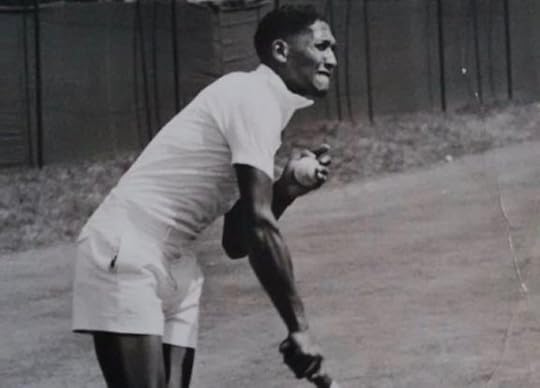

Image via Herri Foundation Courtesy of the Samaai family ��.

Image via Herri Foundation Courtesy of the Samaai family ��. The governing body of world tennis is the International Tennis Federation. It organizes games between professional players, ranks them and sanctions tournaments. This includes junior players. Every year the top junior players compete in a series of graded tournaments around the world. The first tier is known as the junior ���Grand Slams.��� Like with the senior circuit, this refers to the four traditional open tournaments played at Wimbledon, in France, the US and Australia. Below these four are a group of six ���Grade A��� tournaments. One of these Grade A tournaments is played every October in Cape Town, South Africa. In 2019, that tournament was renamed the David Samaai Junior Open.

David (Davey) Samaai was the first black (and or coloured) South African to play at Wimbledon in 1949 when he was 21 years old. He may well be the first black or African tennis player to qualify for Wimbledon too. He qualified again in 1951, 1954 and 1960. His best performance was reaching the third round in 1954. In addition, he also played in the French, German and Swiss Opens. While overseas, he also won several smaller tournaments (mainly in Britain), and played against several of his white countrymen, beating some of them convincingly, including the captain of South Africa���s all-white Davis Cup (national) team, Gordon Forbes. As Samaai would later describe his game against Forbes; it was ���a match which could never have materialized at home.���

In June 2019, a few months before the announcement of the David Samaai Junior Open, Samaai died at his home in Paarl in the Western Cape province.�� He was 91 years old. At the time, Gavin Crookes, then-CEO of Tennis South Africa (the body that runs organized tennis in South Africa), said about the renaming the Grade A tournament in Cape Town after Samaai: ���Whilst this tribute will never adequately recognise the challenges he had to overcome as a black South African, playing in an era that was strictly amateur, as well as the achievements he attained as a top player in the world of tennis, I have little doubt the fact that these trophies will be presented to two of the top juniors in world tennis will go some way to making him proud ��� in his quiet and modest way.���

Crookes��� praise aside, it was his reference to Samaai���s ���quiet and modest way,��� that is telling.

Despite Samaai���s singular achievement ��� at a time when South Africa���s whites-only regime intensified its oppression of the majority black population ��� he is hardly mentioned in popular discourses about sports, especially in local and international media, and the legacies of racism in South African sport and society. And his achievements are not well known outside tennis. When Samaai is celebrated, there is, like with Crookes, a lot of talk about his quiet resilience.

The silence in popular media and culture around Samaai���s incredible achievements is even more depressing given that he played at a time when black tennis players hardly featured internationally. If you google ���who was the first black (or African)�� player to compete at Wimbledon,��� references to Althea Gibson first�� come up.�� Gibson, a black American tennis player who was born in the same year as Samaai, 1927, first qualified for Wimbledon in 1951 when she was 23 years old, two years after Samaai had already played at Wimbledon.�� She went onto an illustrious career, winning the Wimbledon women���s doubles championship in 1956 (with an Australian partner) and then won the women���s singles title in 1957, becoming the first black or African person to win a Wimbledon or any Grand Slam title.

When it comes to men���s tennis, in most tales of tennis history, Arthur Ashe, another American tennis player, is credited as the first black male player to compete at Wimbledon. Ashe first played at Wimbledon in 1963, fourteen years after Samaai. He would go on to win the Wimbledon men���s singles title in 1975, making him world number one that year. Ashe started competing as a professional in the late 1950s and would become the first global black male tennis star. He is still the only male black or African tennis player to have won at Wimbledon, the US Open (1968) or the Australian Open (1970). The only other black male player to win a Grand Slam singles title is Yannick Noah in 1983.�� Noah struggled at Wimbledon though; his best showing was in the third round. (Incidentally, Noah���s father, Zacharieh, was a professional football player from Cameroon whose team won the Coupe de France in 1961. After his retirement, Yannick Noah partly grew up in Cameroon where it was also where he started playing tennis.)

Of the leading male players still active, the best performance of Gael Monfils of France (his father is from Guadeloupe and his mother from Martinique, immigrants from France���s ���departements��� in the Caribbean) was a fourth round showing at Wimbledon in 2018. Jo Wilfried Tsongo, also French (his father is from Congo-Brazzaville), has been to the semifinals (2011 and 2012) and quarterfinals (2010 and 2016) of men���s singles at Wimbledon.

None of these players come close to the achievements of Serena Williams, who has won 23 Grand Slams, the most by any player in the Open era, including seven women���s singles titles. Williams is arguably the greatest tennis player of all time, male or female.

One reason for omiting Samaai���s achievement as the first black African player at Wimbledon, may be that the American narrative about everything – including designating who was ���the first��� at anything – dominates in the black world. Another may be that Samaai downplayed his achievement. Samaai���s biographer Michael Le Cordeur writes that Samaai detested being referred to as a ���coloured tennis player.��� It may also have something to do with how coloured people are viewed in South Africa; in some accounts they are not counted or don���t count themselves as black. However, there is no evidence that Samaai had anti-black politics. In fact, after he retired from tennis, he played a leading role in school sport organized by SACOS, known for its boycottt stance vis-a-vis apartheid segregated sports and for forging a political consciousnes among black (this included coloured and Indian) sports people at grassroots level.

A much more plausible reason may be that tennis is hardly considered a mass sport ��� whether in South Africa or elsewhere. However, Samaai���s own involvement in tennis as a player and administrator and the deep well of organized tennis culture in coloured, Indian and African townships under apartheid, undermines that popular perception. Samaai���s father, for example, played tennis in the 1930s, belonged to a club in Paarl and later built a tennis court for his sons in their backyard. Samaai himself met his wife on the court and they played mixed doubles together in amateur tournaments organized by a well-coordinated national coloured tennis association around the province and the country. Nevertheless, to this day, most South Africans experience tennis as a TV sport happening somewhere in Europe or North America, living vicariously through Venus and Serena Williams or Roger Federer (whose mother is a white South African; Federer, incidentally, was also Samaai���s favorite player).

Tennis, like other modern sporting codes, came to South Africa with colonialism. Unlike those others, tennis as a game became more associated with white elites and with money. The cost of playing (finding a court, court fees, equipment, the right attire) was prohibitive. As a result, tennis never developed the political or social connotations of sports like cricket (with English South Africans and false notions of equality), rugby (Afrikaner nationalism and white resilience and triumph in the face of international criticism of Apartheid) or soccer and boxing (with black mass participation, fame and class mobility) under Apartheid. (It is worth mentioning that sports like rugby and cricket have deep histories among the black population that parallel or even predate that of�� whites, but that the idea that black people came to them late, persists.)

As for professional tennis in and from South Africa ��� both under apartheid and now ��� it is mostly white players who represent the country overseas. Even when South Africa was the subject of sports sanctions, white players still played overseas. The ITF ostensibly banned South Africa from international tennis, but the country still fielded all white Davis Cup teams into the late 1970s after the ITF let South Africa qualify via the Latin American region. (In one case, in 1978, when the sports boycott movement against Apartheid nearly derailed a Davis Cup tie between South Africa and the USA in Nashville, Tennessee, the white South African Tennis Union recruited a 18 year old coloured tennis player, Peter Lamb, then on a college scholarship in the United States to the team to deflect criticism of its racist policies. They had no intention to play Lamb.) On top of it, white South Africans weren���t banned from competing as individuals internationally. As a result, players like Forbes, Cliff Drysdale, Ray Moore, and later Johan Kriek and Kevin Curran, still played world tennis on the ITF circuit throughout and right till the end of Apartheid.

South African tennis thus took on a very white and very exclusive image, which it still does to a large extent even after Apartheid. The combined effect of these media constructions and how the game was organized was to obscure tennis��� appeal among the black population and their role in its development as a sport. Samaai���s story is wound up with the independent tradition of black tennis and is a corrective to these misconceptions.

Samaai was born in 1927 in Paarl, a medium-sized town in wine country about an hour���s drive to the northeast of central Cape Town. Paarl is the largest town in the Cape Winelands, an area which foundation is built on slavery at the Dutch Cape Colony. It was also where Afrikaner nationalists plotted to rewrite the history of the Afrikaans language as white instead of a vibrant creole. Davey was the oldest of seven sons. The late 1920s was not a good time to be born black in South Africa, less so to imagine a career as a black tennis player. While Apartheid would only be formally introduced after 1948, the Union of South Africa ��� the white-run state ��� was already implementing a slew of new discriminatory laws limiting black advancement.

Samaai���s parents, John and Sophia, were of modest income, but owned a house at 19 Du Toit Street in Paarl���s downtown. In 1950 that section of town would be declared a whites-only ���group area.��� The Samaais held on for another nearly two decades, before they became the last family in the area to be forcibly removed to a nearby coloured township.

John Samaai, according to , was ���a competent social player.��� By the 1950s, there were five tennis clubs in Paarl with mostly coloured members, and John was a member of the Ivy Lawn Tennis Club. John naturally introduced his eldest son to the game, andt it helped that the family lived next to a tennis court. Davey started hitting the ball with his dad at the club from around 5 years old. It soon became clear that he had a feel for the game. Davey complimented his father���s training with street tennis played with wooden bats. At some point, John Samaai built the family their own tennis court in their backyard and Davey practiced there with one of his brothers, Frankie.

Not long after, Davey began to compete at club level, playing with a borrowed racquet. (He only got his own racquet when he went to play overseas.) When Davey was 18, he was already national champion (the South African Coloured Tennis Championship) of the South African Tennis Board, which organized the game amongst coloureds. He would retain that title for the next 21 years. (A sidenote: Samaai was a talented sportsman; he also got provincial colors in rugby.)

As he couldn���t try himself against the best local white tennis players who enjoyed better facilities and training, he decided he would try his luck overseas. According to Le Cordeur, Davey���s form should have made him an automatic choice for the 1949 Davis Cup team, but apartheid denied him this honor. ���For the first time, Davey felt that apartheid was standing in his way to greater success��� and that it was time to try his luck overseas. (Later in the UK, he beat South African Davis Cup players like Abe Segal, Gordon Forbes and Cliff Drysdale in practice.)

Samaai would talk about the level of competition among his cohort of coloured players: ���I have no doubt in my mind that we would have beaten any other white club in South Africa had we had the chance to show of our skills.���

Davey���s trip to Europe was fundraised from the local coloured community. When he arrived in the UK, he received an invite to visit the Dunlop offices in London, where he was given six tennis racquets as a sponsorship. At first he struggled on the English grass courts, but soon settled in, becoming known for ���his big forehand, scorching backhand, fearsome serve, balance, anticipation, impeccable net play, speed around the court and stamina.��� One of his first victories, along with his English doubles partner, Colin Hannan, was a victory over a white South African duo, N. Cockburn and S. Levy. A number of other victories over white South African players, who he was prohibited from competing against back home, followed. Davey���s supporters in the coloured community followed his progress closely via the local press and when he played Forbes in 1954, ���were buying newspapers everyday to monitor his progress.���

To get into Wimbledon, you had to be nominated by your country association. Davey could expect no help from the white tennis establishment at home to make this happen. He had to earn the right by playing in a series of smaller qualifying tournaments in the UK, which he did. In his first try at Wimbledon in 1949 he was beaten by an Australian, Jack Harper, 6-1, 6-4 and 6-3 in the first round.

He would qualify again in 1951. During the same year, he made it to the second round of the French Open. (It is unclear if, apart from being the first black South African to play in the French Open, he was also the first black player from the African continent to do so.)�� In 1954, which witnessed his best performance at Wimbledon, he ended up playing his third round match on center court, where he lost to Australian Ken McGregor. This match was his ���career highlight��� and obviously served to showcase black tennis from South Africa on a global scale.

In 1960, at 32 years old, Samaai qualified for Wimbledon for the last time. But by then, his priorities had changed. He had married Winnie, his longtime girlfriend and mixed doubles partner and started a family. Although Samaai would make a few more trips to Europe to play in club tournaments and back in Paarl played in competitive tournaments well into old age and after Apartheid ended, he switched his priorities to teaching for which he had qualified before he left for Europe the first time. He threw himself into the teaching profession with the same dedication he showed to tennis.

Michael le Cordeur���s book Davy Samaai The People���s Champion despite its title and cover image (Samaai hitting a backhand shot at Wimbledon), spends as much time detailing Samaai���s long career as a tennis player, but equally as a teacher, choir director and his being instrumental ���in broadening access to higher education for the rural Afrikaans speaking community.��� Le Cordeur, a professor of education, ascribes Samaai���s success to his family dynamic (two other brothers, Ronnie and Gerald, had fame as performers and artists), to his local community, and ���because he led by example.���

Le Cordeur���s book is not the usual sports biography. Text is interspersed with photographs (giving a scrapbook effect), verbatim testimonies by friends and relatives (his children, grandchildren) and clippings from old newspapers. The result is a celebration of Samaai���s life. (Even Samaai���s funeral is extensively covered.) Le Cordeur writes in the introduction that the current generation don���t know who Samaai was ���because our history has been deleted from the mainstream media in South Africa, which refused to acknowledge what Davey and people like him did to liberate South Africa.���

Le Cordeur wants to ���take ownership of our sport and education, and to take back our space.��� I suspect what he is referring to, but he doesn���t elaborate, so we don���t know exactly what Le Cordeur planned to do. At some level, however, Le Cordeur���s call to take ownership, gels with the call to decolonize knowledge, which by itself is a worthwhile undertaking and which has gained impetus in South African history writing and in popular discourses about South Africa���s past.

As a player, Samaai wasn���t viewed as particularly politically radical. He felt his tennis should speak for him. Nevertheless, Le Cordeur describes him as a ���loyal member��� of the South African Council on Sport or SACOS ���in their fight against discrimination and apartheid.��� (SACOS was founded in the early 1970s to coordinate anti-apartheid sports among black sports bodies explicitly opposed to Apartheid, many dating their origins back to the 1880s. SACOS��� leadership was close to the sports boycott movement in exile and locally to black consciousness, Trotskyist tendencies and the Pan-Africanist Congress and later some elements in the United Democratic Front. SACOS advocated for ���no normal sports in an abnormal society��� and rejected any sponsorships or state support that implied segregation. It was prominent until the end of the 1980s when it was overtaken by the National Sports Congress, a new sports coordinating body which was effectively the sporting arm of the ANC. A proper history of SACOS still needs to be written.)

A British journalist who interviewed Samaai for a short profile in 1961, described his relations with the white South African tennis contingent as ���cordial.��� When pressed, Davey said: ���I hope they are not embarrassed by having me here. I don���t think they are, do you? We seem to get on very well together. When I arrive, everyone wants to know, ���How did you get on with the South African players.��� My answer will always be ���we are very good friends���.��� In his last match in the UK in 1961 (a tournament in Birmingham), Samaai and his doubles partner, John McDonald from New Zealand, played against the white South Africans Ian Vermaak and Berti Gaertner in the final. The matchup was significant, as it was ���the first time a non-white South African had ever played against white South Africans in a tennis final.��� For context: back home the white South African government of Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd had decided to leave the Commonwealth over a demand that it end Apartheid and instead declared a whites-only republic. It had also begun to imprison and banish to exile its main political opposition in the ANC, Communist Party and the Pan-Africanist Congress.

Samaai and McDonald won the game and afterwards the two white South Africans, according to Le Cordeur, ���seemed completely at ease with this quiet, dignified man.��� Le Cordeur quotes Samaai (it is unclear when) saying that after the match the three players discussed politics and the white South Africans wanted to know ���both sides of the story.���

Today people would call that false equivalence.

Samaai then told his white countrymen ���my personal opinion of things,��� that ���I would not come here and criticize our government���s policies. It wouldn���t be the right thing to do. After all, I am South African.���

It may be that he was either apolitical and didn���t have a framework to understand what was going on in South Africa or he did, and was too scared to take the political risk. Le Cordeur���s decision to project this as a beacon of forgiveness on the part of Samaai and Vermaak and Gaettner is a stretch (���these tennis players had reached reconciliation 34 years ahead of what was called the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1995���).

Which brings me back to those characterizations of Samaai as ���quiet and modest��� and a ���quiet, dignified man.��� At some level it feeds a notion of coloured political (and sports) actors as nobly long-suffering and meek, and ultimately apolitical, as opposed to rowdy and troublesome blacks. The problem is Samaai���s actual life doesn���t gel with that. Later in Davy Samaai The People���s Champion��� in a short chapter, Le Cordeur documents some of Samaai���s life as a sports administrator and simultaneously activist against Apartheid sport and building alternative sports structures. It is also where we get a semblance of Samaai���s sports politics which was far from quiet or dignified. Samaai played a key role in the formation of the Tennis Association of South Africa (TASA), who played under the SACOS banner, helping to grow tennis in mostly coloured townships. Also, Samaai was associated with figures like Frank van der Horst, Hassan Howa and Eddie Fortuin, all SACOS leaders and associated with a strident anti-apartheid politics.

Samaai and other TASA leaders and coaches rejected attempts at bribing them, refusing to be forced into doing ���what was against their principles.��� Following unification between white and black tennis in 1999 to form the TSA, as a sign of how imperfect the process was (to a large extent it kept old class and racial inequalities intact in the sport), Samaai became vice president and Crookes president. That same year, President Thabo Mbeki awarded David Samaai the Presidential Sports Award for Lifetime Achievement.

March 9, 2022

Flawed lenses

Image credit Nicolas R��nac via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

Image credit Nicolas R��nac via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0. In 1976, when my three-year-old son was hospitalized for a serious illness, a powerful photo of a rhino and her calf came to my attention. I identified with it instantly, and an image of a rhino mother and offspring has hung near my desk ever since. She might not see well, the image suggests. It might take a lot to provoke her. But head for cover if you ever do anything that endangers or threatens her child. A decade later, as an activist and staff member for the American Committee on Africa, I was engaged in solidarity work with Namibia���s liberation movement (the South West African People���s Organization, or SWAPO) and wrote about the exploitation of Namibia���s mineral wealth before independence. I���ve cared about Namibia and rhinos for a long time.

That���s why I was thrilled when I came across The Black Rhinos of Namibia, by Rick Bass, published in 2013. I would find it to be a beautifully written, deeply felt account of a trek to find the black rhino, one that causes the author to ponder unanswerable questions about Earth, the rhinos, the land, about time and space. However, after my initial reaction to the title, I took in the book���s subtitle: Searching for Survivors in the African Desert���not ���an��� African Desert, not the ���Namib��� Desert���and it is from here that Bass makes telling omissions and errors in the story’s background and context.

There is a complexity to the use of ���African.��� As Chimamanda Adichie has said, ���Before I went to the US,��I didn���t consciously identify as African.��But in the US, whenever Africa came up, people turned to me.��Never mind that I knew nothing about places like Namibia.��But I did come to embrace this new identity,��and in many ways, I think of myself now as African.��� These are complexities that Bass seems not to understand or appreciate.

Bass, like many others, speaks first of Africa as an idea, a single place, not a continent with 55 countries. Meanwhile, he writes very specifically about his own home: Lincoln County, Montana, a tiny, impoverished community with high rates of unemployment and a population ravaged by an asbestos mine. He says that this place gives him a set of lenses that would ���allow me to look at Africa.���

Bass sees with the eyes of an environmentalist, engaged in work to protect the habitat of Montana���s grizzlies. ���Everything I would see,��� he writes, ���would be new and different, but the prescription for my lenses did not need changing, and the stories were so eerily the same.��� He goes on: ���It seemed the only difference was one of time, not space; that the rhinos were the grizzlies, and Africa���s Bantu our Sioux.”

���Bantu��� is a word with a history, the nomenclature chosen by the apartheid government of South Africa to speak of the majority African population of South Africa: the population that apartheid separated into twelve ���Bantustans��� based on language (Zulu, Xhosa, Tsonga, Venda, etc.) in a strategy of divide and rule. It is also a linguistic term, which includes hundreds of distinct languages from Southern to Central Africa and the Great Lakes, and as many as 350 million speakers. It is not meaningful to compare Bantu and Sioux. The Great Nation of the Sioux is indigenous to the Great Plains of North America and today number an estimated 10,000 people. A more meaningful comparison would be to Namibia���s indigenous people���not the Bantu, not the Herero, but the San and several other peoples including the Nama.

Another more meaningful comparison would be that genocides were perpetrated in both places. The Native American population endured one. The Germans carried out a genocide in Namibia. Instead, Bass gives a harrowing description of how ���prisoners��� were shipped to inhospitable Damaraland to die because of ���how tedious it was to execute entire villages.��� He is speaking of the Herero and the Nama, but in his telling, these ���prisoners��� remain nameless.

Bass is a geologist. He is thinking geologically. He writes of the Namib Desert: ���Existing unchanged for so long���ten million years, at least, on the oldest unchanged landscape on earth���the Namib Desert has not so much as blinked, geologically speaking, in its last fifty-five million years.��� In passages such as this, Bass tells the story of his trek in the desert in search of the black rhino. Near the end, he says that he is awestruck, overwhelmed by the beauty of the land, and he struggles to find language for what he has seen.

He has seen a black rhino���one of a species which, he tells readers, is extremely nearsighted. He explains this nearsightedness by asking: ���for who, or what, needed vision in [that] landscape in which nothing ever changed, and in which there were so few challengers���so few of anything?��� May I suggest that Rick Bass could use new lenses to address his nearsightedness, not for the landscape and the flora and fauna, but for the historical and geopolitical context in which they exist.

I think back to that little boy who first made rhinos important to me. When he was still young, I took him to the Statue of Liberty in New York City. The museum in the statues��� base included a model of a ship that brought captured Africans to enslavement in the New World. That is, perhaps, the first time that he attached meaning to the word ���African,��� and what he saw made a deep impression on him. I suspect also, that as a little child in mid-America, I first heard the term ���African��� mentioned with slavery. Is it too much to suggest that such innocent learning in young children haunts us into adulthood and hovers unnoticed, blinding us to how much work we need to do to see our history and that of the African continent in all its complexity?

March 8, 2022

Why are Nigerian academics on strike?

Photo by John Onaeko on Unsplash.

Photo by John Onaeko on Unsplash. Organized through the Academics Staff Union of Universities (ASUU), academics at Nigeria’s public universities are on strike. They’re seeking to force the Nigerian government to implement a 2009 agreement promising increased pay and greater investment in tertiary education. Over the years, the government has been steadily defunding public universities and encouraging privatization. In this episode, Will chats to Sa’eed Husaini and Temitope Fanguwa to understand the origins of the strike, as well as the role of academics in Nigeria’s left politics. On the heels of #EndSARS, could Nigeria be on the cusp of its own #FeesMustFall moment?

Temitope is a Marxist historian with a central focus on African economic history in the Department of History and International Studies, Osun State University, as well as a budding social justice activist and epistemic-decolonizer; and Sa’eed is a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Lagos and a contributor at Africa Is a Country plus Jacobin Magazine. Sa���eed is also a regular guest host of The Nigerian Scam, a leftist podcast examining politics, history, and the fraudulence of bourgeois society from class and ideological perspectives���be sure to check it out.

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.

https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/133b4230-64d0-40bc-a30f-195f1aea0a06/aiac-talk-why-are-nigerian-academics-on-strike.mp3The promise and peril of the digital economy

Roofs of Marrakech. Image credit David Denicol�� via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Roofs of Marrakech. Image credit David Denicol�� via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Digital technologies enable new ways of organizing the production of services, unconstrained by spatial distances. By making it possible to carry out a service from everywhere in the world, digitalization has facilitated the increased fragmentation and outsourcing of services that were previously constrained by the need for geographic proximity between buyer and seller. The digitalization of the economy is at the same time giving rise to new forms of work and new ways of organizing labor processes���across the globe.

In The Digital Continent: Placing Africa in Planetary Networks of Work, Mohammed Amir Anwar and Mark Graham explore the development and organization of digital labor���defined as ���work activities involving the paid manipulation of digital data by humans through [information and communication technologies] such as mobile phones, computers, laptops, etc.������in Africa. They argue that African workers are playing an increasingly central role in digital capitalism by training ���artificial intelligence��� and machine learning algorithms, tagging images, and performing customer services, design tasks, data management, and so on. Thus, Anwar and Graham argue that digital capitalism is���despite rarely being mentioned���increasingly ���made in Africa.��� The aim of their book is to make both African workers and Africa as a core location in the digital economy visible.

Based on extensive fieldwork in five countries���Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda���Anwar and Graham first argue that digitalization has made African countries lucrative destinations for offshoring services. They explore two such cases: ���business process offshoring,��� where a firm outsources non-core functions to specialized subcontractors, and the ���remote gig economy,��� composed of service tasks (such as writing, transcription, search engine optimization, and so on) mediated and coordinated by digital platforms and carried out by individual workers for customers who can be located anywhere. Second, they show how the African labor force is increasingly drawn into the digital economy, as workers who struggle to find employment in the ���analog��� sector of the economy turn to digital labor to make a living. This, Anwar and Graham argue, raises concerns for employment protections, social rights, and working conditions on digital platforms.

Anwar and Graham intervene in a prominent narrative promoted by governments, the World Bank, development organizations, and consulting firms that frames digitalization and information and communication technologies as ���technological fixes��� that will create jobs, reduce poverty, improve productivity, and lead to economic growth in Africa. Although digitalization and the fragmentation and outsourcing of production processes has integrated Africa into global production networks, Anwar and Graham argue that ���Africa continues to be locked into a value-extractive position in the global economy.��� Rather than a frictionless and ���flat��� global economy, Anwar and Graham���s analyses show how digitalization amplifies existing inequalities and power relations; in Africa, digital production is primarily characterized by poorly remunerated tasks at the bottom of the value chain that do not, in practice, represent economic improvements for workers.

For some segments of the population, such as university-educated workers unable to capitalize on their credentials, the digital economy provides an important lifeline. On the one hand, these forms of work provide a certain flexibility and autonomy. Workers are often able to, at least partially, set their own schedules. On the other hand, however, digital labor can also contribute to precarity, as contracts are usually short, working hours long, and social benefits and labor rights irregular or lacking. This is, Anwar and Graham argue, partially a result of workers being classified as self-employed independent contractors, the piece-rate model of compensation, and the ease with which digital firms can transfer tasks to another worker, company, or continent.

In addition, Anwar and Graham highlight the so-called ���algorithmic management��� used in these digital business models. Digitalization, they argue, is not only a tool for capital���s expansion into new localities, markets, and industries���digital technologies also enable managers to exert new forms of control over workers and labor processes. The authors term this form of management ���digital Taylorism,��� a digital manifestation of the Taylorist principles of detailed surveillance, meticulous control over labor process, disassembly of the production process, and ���deskilling��� every task to improve productivity and lower the costs of labor power. While the notion of ���digital Taylorism��� highlights platform capital���s control over workers and labor processes, it might neglect a key feature of ���algorithmic management���: its strategic use of freedom and flexibility. While Taylor���s ���scientific management��� instructed workers on how each particular task should be performed, digital platforms usually allow workers to choose when they want to work, what tasks they want to do, and how they want to do them���partially in an effort to avoid being classified as their employers. Moreover, worker evaluation occurs through rating systems, with workers being sanctioned with moves like ���deactivation��� or firing if their average rating falls below a certain threshold. Thus, ���algorithmic management��� might be seen as representing a mode of management and control diverging from the core principles of Taylorism.

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the ways in which workers assert agency and resist capital���s control, as Anwar and Graham do in detail. Drawing on the notion of ���hidden transcripts,��� they theorize labor agency not solely in organized and collective action, finding that digital workers in Africa exert individual agency through everyday practices and strategies of ���resilience, reworking, and resistance.���

The Digital Continent is a very well-researched and well-written book. Anwar and Graham build on an impressively rich empirical material, mixing statistics and excerpts from interviews to give readers a proper understanding of workers��� lives, struggles, and aspirations. The presentation jumps eloquently between theoretical discussions, explications of labor geography concepts, and empirical investigations, producing thorough and thought-provoking analyses. This is particularly true for the final chapter, where the authors discuss measures for building a fairer global economy and world of work.

As a researcher studying platform work in the Norwegian transportation industry, the similarities between the working conditions, biographies, and experiences of the workers I interview in Oslo and the workers I met in The Digital Continent is striking. They are drawn from similar segments of the labor force and express the same ambivalence toward the real economic opportunities���combined with precarious working conditions���offered by the digital business models. Despite the field���s recent emphasis on how digital business models are being ���embedded��� in local social, political, and economic contexts, these models seem to create surprisingly similar outcomes in very different parts of the world. This puzzle might suggest that although digital labor platforms have to adjust to local conditions, regulations, and so on, they also function as technological and global capitalist machines, exporting the same employment model and ���algorithmic management��� from Silicon Valley (where they are usually designed) to every corner of the world, creating similar outcomes for workers regardless of their different contexts while also taking advantage of local specificities. This highlights Anwar and Graham���s conclusion that the fight for a fair digital economy has to be global.

March 7, 2022

Ukraine and the left���s imperialist economism

Photo by Marjan Blan | @marjanblan on Unsplash

Photo by Marjan Blan | @marjanblan on Unsplash The war in Ukraine, the first war in Europe since the conflagration in the former Yugoslavia, continues to dominate the world���s media. The massive Russian invasion rolls on, slowed by Ukrainian resistance. Popular anti-war sentiment has led to sanctions and the actions by the US and the EU as they quickly distance themselves from Russian oligarchs with whom they were so recently entangled. The surfaces of the dirty money of global capital have been suddenly illuminated.�� At the same time, the war has highlighted the narrowness of the crude anti-imperialist positions that, while focusing on American brutality and warmongering, are silent about the actual invasion of an independent country and thereby avoid engaging the concrete contradictions that are emerging. (Within the ANC government in South Africa there is hedging by the current leadership, and wholehearted support of Putin and the Russian invasion by prominent supporters of the former leader, Jacob Zuma, who had close links with Putin during his time in office, while the SACP condemns Ukrainian racism making it clear that you simply can���t be an anti-racist and against Putin���s war.) “Ukraine is Russian.” Which is exactly what the French said of Algeria when after the FLN declared war in 1954. There was no war, just a ���dispute.��� This analogy to colonial wars is enlightening especially since Lenin���s last written statement on what he called the ���National Question��� concerned Ukraine and described basic principles for socialists and anti-imperialists:

A distinction must necessarily be made between the nationalism of an oppressor nation and that of an oppressed nation, the nationalism of a big nation and that of a small nation. In respect of the second kind of nationalism we, nationals of a big nation, have nearly always been guilty, in historic practice, of an infinite number of cases of violence; furthermore, we commit violence and insult an infinite number of times without noticing it … That is why internationalism on the part of oppressors or great��� nations, as they are called (though they are great only in their violence, only great as bullies), must consist not only in the observance of the formal equality of nations but even in an inequality of the oppressor nation, the great nation, that must make up for the inequality which obtains in actual practice. Anybody who does not understand this has not grasped the real proletarian attitude to the national question.

A ���proletarian attitude��� to the national question was the discussion in South Africa in the struggle years of the 1980s.

It is always remarkable how ideas that seemed to be buried in their context become newly alive as a new crisis reveals the fault lines on which the possibility of a new stage of revolutionary consciousness emerges. The war in Ukraine has suddenly made real a debate between the great revolutionaries Lenin and Luxemburg over 100 years ago. Both were revolutionary socialists and both were rigorously anti-war, but the fact that Lenin advocated for the defeat of his own country in the imperialist First World War set him apart from many others at the time. I was reminded of this in a recent post by ���Militant Anarchist��� about the invasion of Ukraine. ���In Russia, a small victorious war (as well as external sanctions) will give the regime what it currently lacks,��� they write, ���It will give them��carte blanche��for any action, due to the patriotic upsurge that will take place among part of the population. And they will be able to blame any economic problems on sanctions and war.���

Resistance to the war in Russia is growing. They add, ���The defeat of Russia, in the current situation, will increase the likelihood of people waking up, the same way that occurred in 1905, or in 1917���opening their eyes to what is happening in the country.��� Of that 1917 revolution, Lenin reminded his comrades that the Russian workers had targeted the capitalists and the ���Great Russian overlordship of many of the nationalities in Russia.��� Lenin thus insisted from the beginning that different nationalities in ���Great Russia��� be given the right to freely determine themselves and warned against chauvinism in his own party. He was talking to many in the party leadership, including Stalin when he said: ���Scratch a Communist and you���ll find a Great Russian chauvinist.��� Stalin���s counter-revolution, forced collectivization, and starvation of Ukrainian peasants, was rooted in such chauvinism just like Putin���s war today.

When the Irish Easter Rebellion of 1916 rocked the powerful British empire, Lenin called it a ���bacillus for revolution,��� a revolutionary beginning that opened the eyes of the world to the possibility of a new society being built out of the human waste and destruction of the imperialist war. It made international solidarity concrete, demanding that British anti-war socialists support ���revolutionary defeatism��� by supporting the Irish rebellion. Luxemburg, the great anti-war internationalist, had undergone no such rethinking on what was then called the ���national question��� and continued to consider the idea of national self-determination ���petit-bourgeois phrase-monger[ing].��� She railed against ���independent Ukraine��� calling it ���Lenin���s hobby,��� and was dismissive of�� Ukrainian self-determination considering it ���a folly of a few dozen petty-bourgeois intellectuals��� remarkably arguing that it didn���t have ���any historical tradition since Ukraine never formed a nation or government, was without any national culture.��� Lenin did not waver from the principle of national self-determination, even as the revolution was challenged by reactionary forces allied with the White army.

From a Marxist point of view, Russia���s invasion of Ukraine has economic as well as strategic consequences and ideological goals. As well as gas and oil, what is at stake is control of land���namely the rich soil of Ukraine with its highly productive ���black soil��� which makes it one of the world���s largest grain producers, especially wheat for the Black Sea and Middle East markets. It is the world���s largest producer (75%) of sunflower oil, grown in the Sunflower Belt, which stretches from Kharkiv to the Ternopil region in the west. Corn and soybeans are among the other main crops grown in what Putin considers Russia���s breadbasket.

Now indebted to the IMF, and consequently austerity programs and privatization, Ukrainian land and its rural people (about 30% of Ukraine���s population live in rural areas) are threatened by a pincer movement���IMF enclosures on the one hand, and a Russian take over on the other.

Caught between these powerful logics of capitalist accumulation, it is Ukrainian self-organization and mutual aid that can change the dynamic. As ���Militant Anarchist��� put it, ���for Ukraine, its victory will also pave the way for the strengthening of grassroots democracy���after all, if it is achieved, it will be only through popular self-organization, mutual assistance, and collective resistance.��� Along with revolutionary defeatism against the imperial power, Russia, these are arguments for self-determination through popular organization from below in Ukraine.

Such a stance is a welcome breath of fresh air given that the so-called anti-war and narrowly anti-imperialist and socialist groups have been silent about Russia���s military threat and silent on the war against Ukraine and on the shooting and bombing. They forget that Marxism is a philosophy of liberation or it is nothing.

Arming the people is changing the dynamic on the ground and while it is utterly understandable, as it was in Syria when Assad and Putin bombed the people, that Ukrainians call on NATO to save them, it is the people���s own self-activity and the building of grassroots solidarity that is their real hope. This is not to blame the Ukrainians who must do what they have to do, but it does make clear how ���the West���s��� lack of support for the Syrian revolution and lack of sanctions against Russian bombings emboldened Putin and the Russian military in Ukraine and highlighted the hypocrisy and chauvinism of Europe. An element of this contradiction can be seen in the solidarity expressed as Europeans welcome hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees. This welcome is in sharp contrast to the attitude toward refugees from the mass murders in Syria who were turned back at Europe���s borders. And importantly this racism which is at the heart of European civilization is being called out.

At the same time, support for arming the people helps generate what Lenin called ���democratic tendencies among the masses.��� This is not meant to glorify these tendencies, which Lenin adds, exist alongside chauvinism and racism because ���capitalism in general and imperialism, in particular, transform democracy into an illusion.��� Lenin stressed the ���co-existence of imperialism and the democratic tendencies among the masses.��� He called the position of left opponents of national self-determination, including Luxemburg,�� ���imperialist economism.��� The imperialist war and the betrayal of the second international socialists, who voted to support it, led Lenin to a study of Hegel���s dialectic as he sharpened the need to spell out exactly what he stood for as he looked for new revolutionary beginnings in the democratic tendencies among the masses in action as sources to change the world:

The dialectics of history is such that small nations, powerless as an independent factor in the struggle against imperialism, play a part as one of the ferments, one of the bacilli, which help the real power against imperialism to come on the scene, namely, the socialist proletariat.

Whether there can be such a ferment remains to be seen. Resistance in Ukraine to the Russian invasion requires building popular organization from the ground up while keeping Western imperial interests at arm���s length.

March 4, 2022

The young ones

Photo by Jessica Pamp on Unsplash

Photo by Jessica Pamp on Unsplash Kenya will hold its next general election in August 2022, but despite all of the noise from campaigns, the mudslinging, money and voter courtship, only 12% of potential new young voters have registered to vote. Could this youth antipathy herald an important moment in the long running gerontocratic male-centered and elite process that is Kenyan politics? The following article is from our series of reposts from The Elephant curated by editorial board member Wangui Kimari.

With just six months to go until Kenya���s general elections, preparations are in full swing. But the Kenyan authorities seem to be struggling in at least one area: voter registration.

The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) has been trying to get young adults who have become eligible to vote since the last polls in 2017 to register for the upcoming elections. In October, the commission set an ambitious target of adding 6 million people to the voter register within a month, but only a quarter of that number showed interest. In January, the IEBC tried again. Today, near the end of the exercise, it has only netted 12 percent of the remaining 4.5 million potential voters it was targeting.