Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 100

May 23, 2022

Beja music cannot be beaten by any regime

Noori and his Dorpa Band. Image credit Yasir Elhassan, courtesy Ostinato Records ��.

Noori and his Dorpa Band. Image credit Yasir Elhassan, courtesy Ostinato Records ��. I was beaten by Omar al-Bashir���s regime. I was subjected to repression and abuse by his security services. They threatened me and imprisoned me several times. The persecution led me to migrate to Egypt, where I practiced my music freely in Egyptian cultural centers and collaborated with Egyptian artists. After eight years, I returned to Sudan and found that the situation was even worse than before���and that we, the Beja people, are still suffering as an artistic community.

During Al-Bashir���s reign, art was directed according to the regime���s agenda. They fought artists who did not align with or belong to the regime���Beja artists who sang for their own heritage, singing in the language of their community. These artists were never represented on radio or TV or presented publicly in approved festivals inside and outside Sudan.

The Beja people are considered one of the tribes that live a harsh life because of our mountainous desert region on the east coast of Sudan by the Red Sea. Although our region is rich in precious metals such as gold, uranium, silicon, and mica���used in a variety of electronic equipment worldwide���we still suffer to this day because of our marginalization and neglect by successive governments in Sudan, especially during the past thirty years.

Noori. Photo by Janto Djassi courtesy Ostinato Records ��.

Noori. Photo by Janto Djassi courtesy Ostinato Records ��.Al-Bashir used to look at us with nothing but racism and describe us as ignorant and illiterate. He would say we offered no benefit to the state. He and others would describe us as people with an unpleasant smell, and because Beja people are known for their unique hairstyles, they would call us carriers of lice. They say we are a backward and lazy people.

Bashir recruited men of the richer, more influential classes among the Beja in order to implement the agenda of the ruling National Congress Party. Their goal was to obliterate and replace the identity of the Beja. Bashir���s regime did not take even a single measure in favor of the Beja people; our treatment was entirely violent.

The Beja people have held a number of peaceful demonstrations over many years to express our grievances. We have closed and barricaded the national road linking Port Sudan, the country���s largest port, to all other cities of Sudan more than once. The world knows what Bashir did in Darfur, what he did in South Sudan, but they don���t know what has happened in east Sudan to the Beja. If the Beja people are treated better, this will help solve many problems across Sudan. This is why the world must pay attention to the Beja struggle. We have been at the forefront of Sudan���s revolution, demanding political and economic reform since before 2019.

Dorpa Band. Photo by Janto Djassi courtesy Ostinato Records ��.

Dorpa Band. Photo by Janto Djassi courtesy Ostinato Records ��.We are distinguished by our great height and skin color, some brown, some wheatish in color. Some of us grow the hair on our head until it becomes thick, and use a special comb made of wood which we call ���dhal��� in our local dialect. During their occupation of Sudan, the British called the Beja people ���Al-Fazi Wazi������or ���Fuzzy Wuzzy,��� a slur coined by Rudyard Kipling.

We are adept in the craft of hunting. We also have special rituals in the way of roasting, grinding, preparing, and drinking jabana (coffee), one of our most important drinks.

The Beja are also distinguished by the manufacture of weapons, including special knives and swords and a weapon made of wood called the ���safrouk.��� You can not find a Beja person who does not carry a knife on his shoulder or a sword, one of our customs and traditions. They are considered symbols of strength and protection of our own. The Beja people formed a class of archers in ancient Egypt. We are fighters.

I have my own weapon: a tambo-guitar, a special instrument I made many years ago. It combines an electric guitar I found in the scrap heaps of Port Sudan with a five-string tambour my father gifted me.

Photo by Janto Djassi courtesy Ostinato Records ��.

Photo by Janto Djassi courtesy Ostinato Records ��.When I was ten years old, I used to rehearse on a traditional tambour that my father had. I used to go to the coast of the sea and sit and practice Beja music in its rawest form. Today, I compose my own music with Beja melodies. When I came up with the idea of making the tambo-guitar���and, thank God, I succeeded���I was able to use it to preserve Beja culture while also adding a modern touch to the music so it can be appreciated today.

Despite the marginalization of the Beja, our culture has not been killed. We remain committed to our heritage and spend our time playing traditional percussion instruments and the tambour and singing our traditional songs to keep them alive.

Music exists deeply within the conscience of the Beja people and has a great influence on them. We believe in our culture and translate it into music, even to the point of frenzy. I believe that music has a great role in our unity and struggle. It is an enduring mark of our survival, our resistance.

We have a distinctive art and our own tunes that are very different from anywhere else in Sudan or the Red Sea. Our melodies are characterized by the depth and power of their sound, which comes from hearing our music echo along the mountains of our area. Our music is sweet, nostalgic, ambiguous, and honest. It is also very old���ancient. The Beja people are ancient, with pharaonic origins. Our melodies are equally as old, tracing back to pharaonic times. Beja music thus forms an unbroken chain of melodies that have been passed down many generations.

Beja music cannot be beaten by any regime.

Noori & his Dorpa Band���s debut album, Beja Power!, is out June 24th.

May 20, 2022

The psychological pains of Ethiopian intellectuals

Still from Sami���s Odysseys.

Still from Sami���s Odysseys. At the end of Robin Dimet���s documentary about Sami, an Ethiopian man who has spent 20 years translating Greek mythology into Amharic, this heartfelt dedication appears on screen:

To the illuminated loners,

To the fools who feed on books,

To the impassioned outsiders,

To the flayed alive smitten with poetry,

To the open-hearted and inept,

To the radiant and misunderstood.

Sami is all these things: open-hearted and inept, radiant and misunderstood, a man flayed alive and smitten with poetry. While Dimet follows Sami���s attempt to print his translations as a book, the documentary focuses on the many contrasts that mark his life and the country he calls home. This is a film that is as much about Ethiopia as it is about Sami, as we see people struggle within a backdrop of massive construction and development projects.

Sami is easy to warm to, a man who, despite his flaws, is gentle, intelligent and self-deprecating. He lives in a tiny room, the walls covered with mold and electrical wires hanging from the roof. Throughout the film, we learn some of Sami���s struggles. One in particular: the loss of his artist friend Mesfin Habtemariam, shows how Sami���s life is marked by trauma and heartache, but also buoyed by the connections he has made with others through art and literature. Enthusiasm for his translation project and a desire to contribute knowledge to his country are strong currents that run throughout.

The film is full of imagery that shows the bizarre intersection between Ethiopia and the West: Sami���s artist friend, Dany, paints Ethiopian hero Abichu in a European style; plays a piano that is out of tune, his song of choice resembles Ashenafi Kebede���s famous piece ���The Shepherd Flutist;��� the barbershop where he has his haircut is full of images of Western celebrities, such as Will Smith; and livestock meander around a sea of cars and construction sites. We see a number of paintings of naked women, a practice that is very much imported (naked women never feature in traditional Ethiopian paintings). It is startling, at times, to see artwork that is so very European, full of black bodies, in an African country that was never colonized. Yet, like so many other parts of this film, it speaks to the fact that Ethiopia has undergone native colonialism, a process whereby a country���s ruling elite utilizes Western epistemological, ideological, and institutional structures of power to govern their own people.

Sami shows fondness and despair in his relationship with modern things. They are near to his feelings but distant from his reality. The paintings, the piano, the laptop, the Greek stories, are things that have little to do with how most Ethiopians live. Yet, his community trusts and respects him. They issue him essentials on loan, polish his shoes for free, give him feedback for his translation (although some do so without reading the text fully), praise him with songs, and fundraise for his publication. Throughout the film we see others encouraging Sami to talk about himself, his difficult translation journey, and his motivations, despite his resistance at every turn.

Still from Sami���s Odysseys.

Still from Sami���s Odysseys.The film treats Sami very tenderly, but it does not delve into the source of his suffering. It depicts him as a passionate man struggling to achieve his dream despite the crushing poverty around him. It excludes so much of the complex ties that have woven his life with his community. Only viewers with a keen knowledge of Ethiopia���s history will be able to reflect on the invisibility of cultural destruction and war and the enduring threads of compassion and care people offer to each other. The history of the Derg (which governed Ethiopia after the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie and was overthrown in the early 1990s), the ���Red Terror,���, and even the recent struggles with civil war and COVID are only touched on, with Sami refusing to go into much detail beyond saying that he lost his youth and that he is grateful to be alive.

Sami���s pain is seen in his gestures, his behavior and the way he seems to shrink himself, but he tries very hard to hide it. Director Dimet does not go deeper into this history to show why a man like Sami lives with such suffering, with poverty, and dignity at the same time. That being said, Dimet does handle the themes and topics in his film with care, and the continual framing of Sami���s life with Addis Ababa���s sprawl of unfinished high-rise buildings invites viewers to consider the noble people who are abandoned in the obsessive drive towards development.

Indeed, viewers may admire Sami���s creative and intellectual pursuit in the face of crippling poverty. As an Ethiopian myself, however, I see it as deeply indicative of the way in which Ethiopia as a country has been consumed by the West. As the film shows, Ethiopia is desperately seeking to emulate modern Western life through mass construction, new technology, English everywhere���and yet this kind of development leaves people like Sami behind.

At the end of the film, we learn that Sami is estranged from his son, but he hopes that when his son reads his book, he will understand why he was neglectful. Sami himself is so consumed by his translation project, believing that Ethiopians need access to this ancient Greek wisdom, that he sacrifices himself, his body and his family, similar to the zeal we see in Ethiopia���s Western educated elite, who seek to ���modernize��� the country at the expense of Ethiopia���s most treasured cultural values, experiences and wisdom. From this film, I see modernism as nothing but the desire to be absorbed into the West, to be consumed by it, to find solace in its seductive promises that require the sacrifice of one���s culture.

Sami���s sacrifice speaks to a deeper psychological pain many Ethiopian intellectuals face. Since the time when Sami was young, Ethiopia has been going through a radical change, especially in cities like Addis Ababa. This change was motivated by the desire to liberate Ethiopia from its ���backward��� traditions and ���modernize��� it through European knowledge and culture. Western education promoted the idea that Ethiopians were living in a pre-modern society, similar to Europeans in the Medieval period, and that by following Western practices, they would evolve into a ���modernized life.��� Based on this belief, educated Ethiopians justified their disconnection with their traditional culture and society. Separation from Ethiopia���s rich millennia-old heritage was, and still is, regarded as a necessary sacrifice for the modernization of the country. Sami is driven by the same impulse that is leading the country on a tragic and meaningless path to a world where people sleep in rooms full of mold as high-rise apartment blocks climb around them. Although this commentary may not have been Dimet���s intention, the film is shot in such a way that multiple readings���from Western and Ethiopian perspectives���are possible. (For a deeper discussion of modernist art in Ethiopia, based on the lives of Ethiopian artists, see Modernist Art in Ethiopia.)

This film offers a great many things to its viewers: a remuneration on the impassioned and at times self-destructive zeal of the artist; a story of the deep relationships forged between creatives; a reminder of the violence of development that is implemented without care for people like Sami; and a reflection on the very human desire to contribute something to one���s society, to live a life that leaves something behind.

May 19, 2022

Omar Blondin Diop and Issa Samb���s Senegal

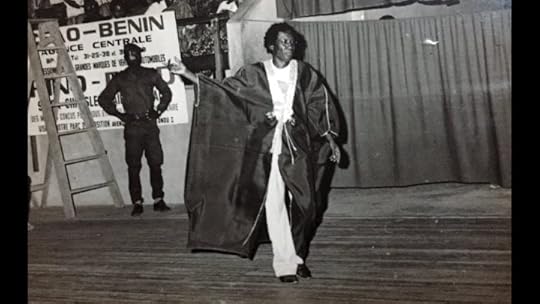

A still of Omar Blondin Diop and Mustapha Saha in the film Mai ���68 �� Paris by Alain Tanner and Jean-Pierre Goretta.

A still of Omar Blondin Diop and Mustapha Saha in the film Mai ���68 �� Paris by Alain Tanner and Jean-Pierre Goretta. When I remember Omar Blondin Diop and Issa Samb, I can only write in the narrative present. Upon his return to Paris after the lifting of his residency ban in September 1970, Omar talks about innovative, promising artists, eager to defolklorize African art. To me, he is someone who has an eye for talent, in search of an irrecoverable change of course through art. Senegal���s May 1968 is a bloodbath. Must one prove that an African can create beauty based on the Western model?

Omar constructs bridges between cultures. He wants to make Dakar an interactive matrix. He gathers information about the global avant-gardes. He maintains relationships with journalists, artists, and American intellectuals. He goes with me to Croissy, to the home of my friend, actor and filmmaker Pierre Cl��menti, a precursor to the French underground. I recall a memorable evening with Julian Beck, Judith Malina, and the Living Theatre the night before their event in Nanterre University���s large amphitheater. They are rehearsing their show, Paradise Now, for the Avignon Festival. Pierre Cl��menti is reciting Antonin Artaud���s The Theater and the Plague, a text written in 1934 which recalls the Great Plague of 1720 in Marseille. I recently reread the book; odd parallels between 1720 and the situation in 2020. Omar is a man of the theater���in the way he dresses, speaks, his posture, with his intimidating dignity. A few days later, he is immersed in Antonin Artaud���s complete works. He is part of our ���Coupole��� (French for cupola) gang, where nights begin at the brasserie on the Boulevard de Montparnasse and continue till morning at Rosebud, the American bar on Rue Delambre. Omar develops project after project���a radical critique of hierarchical society, the totalitarianism of the state, brainwashing by the education system, film synopses, outlines of theatrical plays, and drafts of books. I would be delighted if we could find written, photographic, or film archives from between 1968 and 1969, when Omar is sowing situationist seeds.

We must restore Omar���s philosophical, literary, and artistic personality. In 1968, I kept a diary where I documented juicy, interesting adventures and misadventures, striking meetings, and restorative exuberances. Omar writes a lot, takes notes in carefully kept notebooks. I am appalled that I can only find two or three photos of him in May 1968. What happened to his writings, his photos, apart from those his family has preserved? I know, having witnessed it in London between June and August 1968, that Anne Wiazemsky photographs him often. She gives him a Beaulieu Super 8 camera right in front of me. Jean-Luc Godard is insanely jealous. Omar tells me that he is the sole author of his contribution to La Chinoise (The Chinese Girl). His style and words are easily recognizable. Jean-Luc Godard is happy to just jot down a few questions. And yet, the filmmaker appropriates the entire script and its dialogues. The two surviving actors are Jean-Pierre L��aud, who I bump into from time to time at La Closerie des Lilas���he is still affectionate toward me, still withdrawn, and permanently confined in his inner delirium���and Michel S��m��niako, now 80 years old, a world-renowned photographer who specialized in light painting. He gives me all his archives on the film La Chinoise, including the daily call lists showing that Omar often needed to be present���whereas in her biographical account, Une Ann��e Studieuse (A Studious Year), Wiazemsky says that Omar only participated in the film on the day he performed.

Omar���s current political exploitation would have unnerved him. The enfant terrible of the undefinable revolution loathes protocol, distinctions, honors, and special treatment. One day, in the pleasantly cramped quarters of the Caf�� Old Navy on Boulevard Saint-Germain, where we rub shoulders with Nathalie Sarraute, Samuel Beckett, and Arthur Adamo, Omar spends a long time scribbling incomprehensible pages of numbers and letters. I finally ask him what he is doing. He replies: ���I���m trying to balance the revolution. It is not easy.��� What revolution? A revolution fashioned after Western concepts, where capitalism changes according to the situation: wild capitalism, fascist capitalism, monopolistic capitalism, global capitalism. Capitalisms which are protected, in each case, by an impenetrable arsenal of laws. Justice, in this system, has no meaning. The philosopher Simone Weil (1909-1943) makes this instructive observation: ���The Greeks had no conception of rights. They had no words to express it. They were content with the name of justice.��� The Romans invented the legal system. Rights only produce and reproduce injustice.

A stay in Dakar with economist Samir Amin. Regular visits to the studio of Issa Samb, also known as Joe Ouakam. He says to me: ���Sorry about the street���s name���Jules Ferry���it was not my choice. The colonialist choice of Versailles racism crushing the municipality alone shows the criminal aberrations of the ideology of N��gritude.��� He shows me his tree, an enormous rubber tree, maybe a thousand years old, heaven���s messenger. A chorus of birds. An unbelievable clutter drowned in greenery. An open-air studio. A planetarium. A real flea market. Trinkets, decorations, figurines. Hand puppets, rod puppets, marionettes. Dusty jackets hanging from the branches. They welcome friendly ghosts at dusk. Decrepit specters. Ernesto Che Guevara, Am��lcar Cabral, the Black Panthers. Collages. Scarecrows. Simulacra. Daily palavers on wobbly chairs. The world comes together and falls apart away from public view. Voices from elsewhere. A perceptible presence of undetectable visitors. Interconnected paradoxicalities, between daily complexities and cosmic jaunts. Suspended time. Consolidated space. Quantum escapades. Ancestral orators, tricksters, and mocking blackbirds invite themselves into the courtyard. Joe betrays himself when he points his gaze toward the imperceptible, or when he perks up his ears for no apparent reason. He is in dialogue with the invisible. His wooded life in the heart of the city punctuates his silences, his verbal witticisms, his dance steps. Joe wears Omar Blondin Diop���s absence like an open wound. We share our inconsolable sorrow. When we express our nostalgias for 1968, he intersperses the exchange with the leitmotif, ���A shame Omar is gone.���

The Agit���Art experiment and Tenq workshops in Dakar bring together artistic practice and the history of Chinese immigrants. ���Tenq��� means connection in Wolof. A camp near the airport, turned creative space. The former cafeteria is now a gallery. The Tenq 96 manifesto is posted on the huts. Several unifying figures: the philosopher, poet, and artist Issa Samb (1945-2017), the artist El Hadji Sy (born in 1954), the filmmaker Djibril Diop Mamb��ty (1945-1998), the photographer and filmmaker Bouna Medoune Seye (1956-2017), the painter and sculptor Amadou Sow (1951-2015). And still others. An entire generation of exceptionally talented intellectuals. The group is opposed to the neocolonial ideology of N��gritude that L��opold S��dar Senghor promoted. It develops new forms of expressions. The event receives media coverage, goes international, and perpetuates. Among the main facilitators, El Hadj Sy is invited to the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt for an exhibition titled, ���Painting, Performance, Politics,��� between March and October of 2015. In June 2013, at the Office for Contemporary Art Norway in Oslo, Issa Samb is offered a retrospective, which brings together emblematic works of his previous twenty-five years: paintings, drawings, sculptures, collages, installations, and performances. The daily, mythological, empirical, and phantasmagoric worlds merge together. Enigmatic, sibylline, cryptic works. The formalism of the ��cole de Dakar is obsolete. The abstract aesthetic is under attack. Spontaneity and experimentation are grounded in social realities. Public involvement is required. Its credo: give, receive, detoxicate, reconcile, heal, witness, popularize, perpetuate, act, interact, imagine, conceive, produce. Learn, create, and pass it on. Communicate with the wisemen of the sacred forest. Free the masks, totems, effigies, and fetishes from the museum���s incarceration.

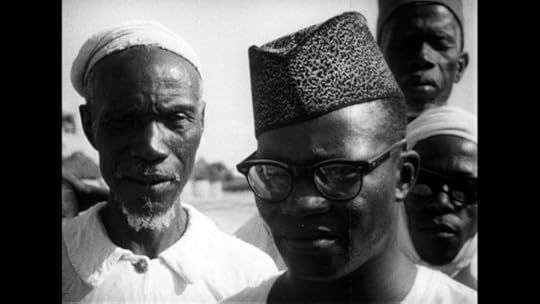

Issa Samb aka Joe Ouakam. Portrait. By Mustapha Saha ��.

Issa Samb aka Joe Ouakam. Portrait. By Mustapha Saha ��.Le Politicien (The Politician), a satirical weekly created in exile by Mam Less Dia in the 1970s, alludes to this. Support for disobedient writers, artists, and journalists. Clandestine correspondences. Remote letters, internal replies. In Dakar���s Plateau District, Issa Samb���s address is unmistakable. The weekly writes: ���The district was called Plateau. It was the occupier���s district, the collaborators��� district. It became the district of the bourgeoisie, the district of those who had means, the district of those who had influence, the district of cedar and scabbard fish. It was the district of the people of renown ascendency and descendance. The district of the people nominated ex-officio. The Plateau district had not moved. It was emptied of its former occupants, who had left for elsewhere, farther away, leaving room for Cape-Verdean immigrants, Joe the Philosopher and rue F��lix Faure���s philosopher���s apprentices. The Plateau district had been cornered by its own fortification which plunged into the ocean and thus had kept all its distinction as a private district.��� We occupy a house, a ruin, a courtyard and deconstruct its past, create a new existence, with a new ethnic belonging, a new valuation, a gratifying trajectory. We sink into it. We mold into it. We feel alive. We recover the fragrant plants, essential emotions, mental delight. Agit���Art launches the Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ), freedom through the artistic creation of an urban space, the transfiguration of ordinary life through inventions, collective innovation, exhibitions, performances, and video projections. Restoring art to its original form: life. The residents are actors, creators, designers. The title of my ���68 poster: ���Beauty Is in the Street.��� The residents of Rue Jules Ferry, renamed Rue Joe Ouakam, mobilize.

On February 17th, 2022, the municipal council of Ziguinchor, the largest city in Casamance, decides to rename the streets bearing the names of French dignitaries. Rue du G��n��ral De Gaulle becomes Rue de la Paix. Avenue du Capitaine Javelier is changed to Avenue du Tirailleur Africain. Rue du Lieutenant Lemoine henceforth bears the name Thiaroye ���44, after a locale near Dakar where African soldiers, who had fought for France, were gunned down in December 1944 for demanding payment for their services. Rue du Lieutenant Truch is changed to Rue S��l��ki, in memory of a battle won in 1886 by resistance fighters from that village against French colonial troops.

The COVID crisis revives writing surreptitiously. Hey Joe, civilization is dying. Merchants are closing shop.��Beggars are leaving the city. Cats, rats, cockroaches are running away. Factories, offices, mosques, and churches are shuttering their doors. Imams, priests, marabouts, griots, and sorcerers are cloistering themselves. At the Vatican, the pope is at his window praying alone. Shielding measures. Prophylactic distancing. The streets are desolate. Theaters are empty. Under the kapok trees, the palaver continues indefinitely (passage inspired by an Agit Art text from November 2020).

Issa Samb is a psychic artist. He navigates endlessly between immaterial entities and their symbolic incarnations. He is a soothsayer of poetic inspiration, artistic vision, and scientific intuition. When he is trusting, he speaks with ease about clairvoyance, retrovision, telepathy, and divination. He is given to inhabiting his astral double at will, navigating his intellectual automatism unguarded, deploying his imagination uninhibited. His lapses, from medications, from cogitations, from cognitive urges, are translated into images. Installation materials pile up, magnetize, hypnotize, and exchange their messages through vibrant undulations. Art is a semiotics of terrestrial, cosmic, and psychic causalities. A painted lady landing on a fragile stem without disturbing its balance. A spring murmuring underground. Quantum mechanics. A theory of dynamic systems. Art adventuring into the mathematical universe. Infrareds. Holograms. Spectrograms. Astral travel. Returning to Earth.

We go back to the idea of a collective project about Timbuktu and Tamasheq in Amazigh, founded by the Tuaregs in the 11th century by the name ���Tim Buqt,��� which means distant well. Long discussions. Joe is walking a tightrope. His studio does not belong to him. He knows he can be thrown out at any moment after his owner-friend has passed. ���Everything which has the effect of uprooting a human being or of preventing one from becoming rooted is criminal��� (Simone Weil again). For Joe, art is turbulence, buoyancy, a metamorphosis of quotidian burden. He wants to avoid commercial vampirization. Nomadic atavism. I take a stand against perishable, degradable, preemptive culture, which mirrors consumerism.�� To go beyond the ephemeral, putrescible, destructible, provisional installation, pathetic performance. To immortalize the trace. Transmit memory. The very purpose of these lines. For our project on Timbuktu, Joe would have fashioned sculptures���out of papier m��ch��, out of clay, cast in bronze if possible���books, papyrus, parchment, palimpsests, idols, tablets, and hands in the writing position. Figures of scribes, calligraphers, ideographic writers, hieroglyphics writers, graffiti artists, taggers walking around in the air. I would have made paintings and corresponding texts. Timbuktu, the cultural capital of West Africa in the 15th century. Tens of thousands of manuscripts, copies of ancient books, of all the sciences, in Arabic, in Hausa, in Peul, a significant number of them on Moroccan culture. Books scattered throughout family libraries. Mali���s population mobilized in 2012 to save several hundred thousand manuscripts from public burning. We have this premonition. Joe makes some installations with bundles of newspapers and masses of books. He makes a throne out of them and sits on it. Our project could not see the light of day because once again, that same year, 2012, I was called as a sociologist to advise the presidency of the French Republic. I painted Joe���s portrait to make up for it.

I see Joe again in 2012 during his exhibition at Documenta 13.�� The event excites him, but at the same time, it bothers him. He is afraid of being appropriated by neoliberalism. I say to him: ���Joe, look at yourself in the mirror. If there is one person on this earth who cannot be appropriated, it is you.��� Documenta was created in 1955 by Arnold Bode (1900-1977), an anti-fascist architect-designer born in Kassel who wanted to reconcile the Germans with international modern art after Nazi isolation. The exhibition is held every five years. It is shown throughout the entire city of Kassel, which was destroyed by British bombs during World War II, in preserved historic sites; in sacralized ruins; in memorial buildings; in parks: Wilhelmsh��he Park, Karlsaue Park, Sch��nfeld Park; in Hauptbanhof Central Station; at the Orangerie, a history museum; at the Ottoneum, a former theater, today a natural history museum; at the Neue Gallery; at the Friedericianum, one of the oldest European museums, renovated in 1982. The more recently built Documenta Hall stands in contrast, with its glass and iron architecture. Joe, whose curiosity is insatiable, is as interested in urban history as he is in the monuments and visual art.

Kassel, the former capital of the Kingdom of Westphalia (1807-1813) ruled by J��r��me Bonaparte, Napol��on���s brother; the city where the brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, as the court���s librarians, collected and universalized old folk tales. ���Snow White,��� ���Sleeping Beauty,��� ���Little Red Riding Hood,��� ���The Valiant Little Tailor,��� ���Tom Thumb.��� An artist���s vigil. This recalls the African legend of the sorcerer from Niamina. The story goes back to time immemorial, when Heaven lived on Earth. The Earth bore a daughter, Mahura, who, among many qualities, had one shortcoming: she worked too much. She ground millet from morning to night. Her pestle constantly knocked at Heaven���s door. One day, exasperated from receiving those blows, Heaven wrapped itself in clouds and floated higher and higher until it was far, far away. Mahura was in despair for having separated Heaven from Earth. She tried to rectify her error. She sent two sumptuous gifts up to Heaven, a gold nugget and a silver pebble, which expanded in the celestial vastness and became the sun and the moon. But Heaven refused to return to Earth.

The commissioner of the exhibition, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, curator of Rivoli Castle in Turin, f��tesJoe. She invites him to meetings with journalists, to receptions, and to discussions. The estate is scintillating with a thousand enchanting lights. Beyond the spectacle, stimulating perceptions, sensations and emotions. In his signature patchwork jacket, his midnight-blue beret secured tightly on his head, Joe arranges his installation around a tree, a faithful reproduction of a corner of his courtyard in Dakar. He shows me his new shoes; ���works of art,��� he tells me. Senegalese fabrics, red boubous hanging on branches, kola nuts, gourds, bits of wood, an open suitcase, crosses, dolls, everything brand new, specially crafted for the event. The fabrics and foliage flutter in unison. The vivid colors are imprinted on your eyes as if they were flowers. The sensations render any commentary futile. A poet, dramaturge, actor, sculptor, painter, prehistorian, Trans-Saharan traveler, phalansterian, marabout, sorcerer, exorcist, prophet, witch doctor, geomancer, and magician, with his rebellious faluche, his Sartrean pipe, and his Guevara-esque nonchalance, Issa Samb has made a religion out of total art. He is a charismatic, magical artist, a centrifugal force endowed with wisdom and perspicacity.

May 18, 2022

Inhabiting the shapes and sounds and patterns of other people

Image credit Erik Hersman via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Image credit Erik Hersman via Flickr CC BY 2.0. Binyavanga Wainaina was a key representative of African literary and public intellectual culture from the early 2000s to about 2014. From then until his tragic death in 2019, his public appearances became infrequent as did his output, save for his extraordinary account of his stroke in Granta, ���Since Everything Was Suddening into a Hurricane.���

As Africa Is a Country colleague, Zachary Rosen, reminded me while I was writing this: it is especially important to talk about and elevate Binyavanga���s contributions to cultural politics and the political economy of publishing because young people coming of age today may not have witnessed his creative expression in action or felt the energy of his literary work. For those lucky to have been in his presence, like Zach and I, Binyavanga was quite a scene: ���… speaking with his arms, his head, his whole body; assured meandering words flowing forth, to where one couldn���t be sure at first, but they always got there if given the chance.���

Binyavanga lived publicly and fully. Inevitably, he divided opinion and had his defenders,�� critics, allies, and enemies. I myself, who broadly identifies with leftist working-class politics and draws on those traditions��� rich histories on the African continent, particularly in my native South Africa, didn���t always agree with Binyavanga. A case in point was his ���Upright People��� movement near the end of his life, which was hard to pin down with its contradictory mix of libertarian impulses and radical democracy. But at the same time, I admired how he lived his own principles and how brave he was. And how cutting he often was about politics. As he wrote, in his memoir, about his native Kenya���s politics on one of his visits there from South Africa: ���I returned to my home, Kenya, to find people so far beyond cynicism that they looked back on their cynical days with fondness.���

And, while Binyavanga is considered a charter member of the Afropolitans, he also struggled with it, critiquing its limitations and trying to stand alongside as well as apart from it. In this, he reminded me of something Edward Said said about himself once (and which I partly adopted as a credo):

I���ve never felt myself to belong to any establishment of any kind, any mainstream. I���m interested in mainstreams, I���m jealous of them, I sometimes, occasionally, envy people who belong to them���because certainly I don���t���but on the whole I think they���re the enemy. I feel that authorities, canons, dogmas, orthodoxies, establishments, are really what we���re up against. At least what I���m up against, most of the time. They deaden thought.

Or as Binyavanga himself wrote in his 2011 memoir with its aspirational title, One Day I Will Write About This Place:

I am starting to scribble my thoughts, to write these moments. It is when this is all done that I do what I do best. I look up, confused and fearful, all accordion with kimay [a word he invented to describe how he was hearing and seeing the world]; then soak in the safe patterns of other people, and live my life borrowing from them; then retreat���for reasons I don���t know���to look down, inside the safety of novels; and then I lift my eyes again to people, and make them my own sort of confused pattern. I am no sharp arrow cutting through the career ladder. It���s time to try to make some sort of sense of things on the written page. At least there, they can be shaped. I doubt myself the moment I think this.���

I am remembering how I first came to know about Binyavanga and his work. And this involves the fact that a big part of his biography involved his deep connection to South Africa.

If you know his personal biography, which he writes about in One Day I Will Write About This Place, he came to South Africa, in the early 1990s, to study at the University of the Transkei in Umtata. It is worth highlighting the fact that he came to study in a region that was the remnants of a South African bantustan; not just any bantustan, but one that was central to apartheid���s divide and rule politics, and at the same time some of its most disruptive oppositional forces. (People forget Bantu Holomisa, the progressive general who in 1987 had orchestrated a coup against the Matanzimas and Stella Sigcau and then made the Transkei a safe haven for returning exiles like Chris Hani after 1990.)�� That Binyavanga went to Transkei rather than the more high profile schools where many well-to-do families from elsewhere on the continent sent their children, such as the University of Cape Town, Rhodes University, and Wits University, is testament to making choices that, like Said, are anti-mainstream.

Binyavanga would stay in South Africa for at least the next decade trying to build a professional reputation as a caterer and food consultant, as well as a writer. As he described himself at the time: ���As a hobby, I collect information about traditional and modern cuisines of Africa, and write extensively about them. It is my aim to start to find an Afrocentric perceptual framework with which to comment about cuisines of the continent.��� Already he was showing his penchant for self-promotion and bawdy humor: ���I am widely regarded as the leading commentator on African Cuisine in South Africa … But I would much rather describe myself as a dedicated Food Slut.���

It was his writing that first drew my attention. When I discovered his work around 1997, he was writing a weekend column about food in one of the daily newspapers, and I was just back from studying in the US so couldn���t help but notice his writing, though it was buried between TV listings and photos of social events. Next to a lot of ordinary writing in much of the surrounding pages, Binyavanga���s prose jumped off the page. Now, I couldn���t find a sample of one of those pieces, but another piece that he published elsewhere at the time, gives a flavor:

I had a memorable Kenyan meal at a friend���s place in Sandton three years ago. We ate a roast leg of goat, sukuma wiki (curly kales) and m���kimo with njah beans. There was bottle after bottle of Tusker beer to wash it down. The fresh goat and the njah beans had been smuggled through Johannesburg airport by our enterprising hostess. The beer came wrapped in a diplomatic pouch, and the curly kales were hijacked from the fish section at a nearby ���Pick ���n Pay ( it uses the green vegetables to dress the display). I am told that ���Pick ���n Pay��� cameras in Johannesburg have learnt to spot Kenyans as soon as they walk into the supermarket: “Warning to all fish market staff���you are about to be undressed!”

By the turn of the century our paths crossed at the journal, Chimurenga Magazine, edited by Ntone Edjabe, and where I helped out as a contributing editor.�� Binyavanga was moving back to Kenya and in 2002 one of his short essays, ���Discovering Home,��� published in Chimurenga, and described in some places as an autobiographical novella, won the short story Caine Prize. At the time he won the Caine, he was only the third recipient. The Caine Prize, based in Britain, had been inaugurated in 2000. Leila Aboulela was the first and Helon Habila the second recipient. The prize would elevate Binyavanga���s public profile and set an expectation that he would write a novel. Later, Binyavanga would disavow himself from the Caine, but more on that later.

In 2006, Binyavanga���s life and people���s expectations of him changed with the publication in Granta of a short piece, ���How to Write About Africa.��� That article lampooned Western media stereotypes of Africa and made him a global star. It is also where my work and later that of Africa Is a Country, which I founded in 2009, became very clear.

At the time, mainstream media coverage of Africa in Europe and the US was abysmal. On top of it, the popular sources about African politics and culture were mostly blogs that highlighted development debates, NGO issues, the pros and cons of US or EU foreign policy for Africa argued between Americans, and the aspirational politics of African government elites like Thabo Mbeki���s ���African Renaissance.��� They had very little to do with actual African politics, aspirations, or perspectives. I saw Africa Is a Country as intervening in those debates. But I also wanted to introduce audiences to leftist or progressive perspectives on African affairs and undercut the dominant media narratives about Africa. �� Binyavanga would also later publish a few essays in Africa Is a Country, adding to its legitimacy and cultural capital, but nothing we did could equal the impact and reach of ���How to Write About Africa.��� Nothing since has slapped as hard as a piece of cultural criticism since Chinua Achebe, in 1975, wrote An Image of Africa about Joseph Conrad���s Heart of Darkness. One big difference between Achebe���s and Binyavanga���s essays was that the latter had the internet as a distribution tool. One African journalist in 2010, at least four years after its publication, summed up the impact of ���How to Write About Africa:���

[it] remains the most forwarded article in Granta���s history. The laugh-out-loud-funny satire captured every recorded stereotype that has been used by journalists, novelists, and historians when writing about Africa and its myriad countries, peoples, languages, and animals���and turned each clich�� on its head. The actor Djimon Hounsou even made a video of himself reciting the essay in a faux-serious tone.

Later, Binyavanga would write, in Bidoun, ���How to Write About Africa II: The Revenge,��� about the reception to the original essay. He revealed that it was, with few edits, entirely based on an email he had fired off in frustration to the editors of Granta over its ���Africa��� issue. The editor encouraged him to turn it into an essay. But Binyavanga also revealed how tired he had become of how that essay framed his writing and the view of him in public life:

Novelists, NGO workers, rock musicians, conservationists, students, and travel writers track down my email, asking: Would you please comment on my homework assignment / pamphlet / short story / funding proposal / haiku / adopted child / photograph of genuine African mother-in-law? All of the people who do this are white. Nobody from China asks, nobody from Cuba, nobody black, blackish, brown, beige, coffee, cappuccino, mulatte. I wrote ���How to Write about Africa��� as a piss-job, a venting of steam; it was never supposed to see the light of day. Now people write to ask me for permission to write about Africa.

If ���How to Write About Africa��� connected early Africa Is a Country and Binyavanga, his coming out as gay in 2014, was the first time, outside of appearing on panels, for us to work together. That moment was also an interesting one for African digital cultures.

The story revolves around events leading up to and on Binyavanga���s 43rd birthday on January 18, 2014. On that day, Africa Is a Country and Chimurenga Chronic simultaneously published an online essay by Binyavanga, ���I am a homosexual, mum.��� Referring to the post as the ���lost chapter��� of his 2011 memoir, ���I am a homosexual, mum��� was written in the form of a letter to his late mother and ������ cuts back and forth between different ages, as well as real and imagined memories.��� As we learn, sadly, from the piece, he never actually told his late mother (who passed away a few years ago) that he was gay.

A few days later, Wainaina and those close to him, also put up a series of Youtube videos in which he expanded on his reasons for coming out, and also opined on a range of other topics (a sort of video manifesto). While the videos had some traction, it was his essay that went viral.

The essay was reported on by most mainstream Western media and also in African media (both print, television, and online), especially in Kenya where Binyavanga resurfaced on chat shows.�� The attention did not surprise anyone. The publication of ���I am a homosexual, mum��� coincided with a fierce debate and a stifling legal environment for gay people in a number of African countries. At the time, 35 countries in Africa had ���anti-homosexuality laws.��� As The Guardian reported at the time, Binyavanga specifically timed his essay to coincide with: ,

��� a moment when his country, Kenya, is ratcheting up its official and colloquial homophobic rhetoric. When its neighbor Uganda���his mother’s home nation���has had before its parliament a bill introducing the death penalty for some homosexual acts and where a leading gay rights campaigner was not long ago murdered. And at a time when Nigeria���a country Wainaina is in the habit of visiting several times a year���[openly flaunted its repression of LGBTQI people]. Wainaina���s lost chapter, then, was a pointed and deliberately provocative act.

What interests me is how ���I am a homosexual, mum��� entered our media worlds: the fact that it was first posted on two small African, niche websites���Africa Is a Country and Chimurenga���before it was picked up and reported by mainstream media.

Binyavanga���s choice to publish the essays at Africa Is a Country may have surprised many.�� There was an important rationale behind the decision as Binyavanga would explain in an interview on American public radio a few days later,

I���m a writer, and I���m an imaginative person. And I think I kind of had a feeling, having been in the media before, that the media kind of deals in sort of, you know, nice things, but bullet points ���: [And he made scare quotes] ���In the heart of gay homophobia darkness in Africa Binyavanga writes ������ [or] ���Binyavanga explained how homophobia in Africa works��� ��� So it was very important to me that first ��� I didn���t want this story published in The New Yorker or in some magazine abroad or anything. I wanted to put it out for people to share. I wanted to generate a conversation among Africans ��� just talk around the issues in a certain way.

So, Binyavanga wanted us to imagine for a moment that if Africa is a Country and Chimurenga Chronic didn���t exist, he would have had to go to an elite Euro-American publication like the New Yorker, the New York Times, or The Guardian. Equally important, had Binyavanga made the announcement in a Western mainstream media outlet, opponents of gay rights on the continent (who include a number of Western enablers) would have seen him in a Western media outline, and concluded: ���See, homosexuality is a Western thing,����� and could have easily dismissed him or cast doubts on his motives.

For that, I am eternally grateful to Binyavanga.

In his final years, Binyavanga prefigured some of the kinds of ideas that are now mainstream among black creatives or Africans or African-descended people in publishing. He became more outspoken about building African creative infrastructure (this included his disowning the Caine Prize). He also urged Africans to connect���not uncritically or romantically���with our traditions and histories, our own usable pasts, in confronting and imagining new futures. His broad project ���Upright People��� movement was an example of this.

In the end, it was sad to watch from afar as his body began to fail him, and overwhelmingly sad when news arrived that he had a fatal stroke.

In One Day I Shall Write About This Place, ��Binyavanga writes: ���what a wonderful thing. I think, if it were possible to spend my life inhabiting the shapes and sounds and patterns of other people.���

I think he did and we���re better off for it.

This is adapted from a presentation at an online event celebrating Binyavanga���s life on March 31, 2022: A Celebration of the Legacy of Binyavanga Wainaina at Yale.

May 17, 2022

Take it to the house

Giannis Antetokounmpo. Image credit Keith Allison via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0.

Giannis Antetokounmpo. Image credit Keith Allison via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0. This month we’re kicking off a new seasonal theme on Africa Is a Country Radio. Over the next six months, on each episode we will soundtrack a different sport, exploring its relationship to music, the politics surrounding it, and its relationship to the African continent. To start things off, in the midst of NBA playoff fever, we take a look at the fascinating historical relationship between basketball, music, and racial politics in the US, as well as glance at some of the global reverberations of the game in recent years.

Listen below, or on Worldwide FM and follow us on Mixcloud.

May 16, 2022

The case for educational justice in post-COVID Africa

Image credit Olympia de Maismont for the European Union, 2021 via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image credit Olympia de Maismont for the European Union, 2021 via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. As is still common in the ���Global South,��� Affo, 29, was born in a polygamous family comprising more than two dozen children. Yet, he is the second child to have obtained a high school degree and the only one to have gone to university: A rare ���progressive��� family and a great ���achievement��� by community standards. Affo was brought up in a place where educational opportunities are nearly non-existent. His native village is more than 15 km from the closest town with a high school. Growing up, Affo had no bicycle, much less a motorbike to commute the distance. When he was lucky, a rare commodity in such a place, he would get a lift along the way.

Added to that challenge was the fact that, for the seven years of his high schooling, he had to judiciously combine studies with various part-time jobs to make ends meet, not just to pay tuition fees, but also to cover daily expenses. Thus, he faced seemingly insurmountable disadvantages at achieving a basic education. But Affo���s is not an isolated story. Rather, it���s the specter that has been haunting Benin and the wider African continent.

This is an uneven battle, one that is set to ultimately make him fail. Failure here means giving up on your education, just like so many before you. If we���re serious about intergenerational fairness, we need to urgently address education challenges facing millions of Affo across Africa. Only then might we be able to rewrite a generational contract that is fair to everyone everywhere.

The challenges with education in AfricaIn the African context, the clich�� that education is the path to prosperity and growth remains critical because that path is yet to be properly charted. A widening ���educational inequality��� is a major global problem, but its effects are particularly dire in Africa given the significantly low level of literacy in the region and the failure of education systems to adapt to the constantly evolving dynamics of learning. While the global literacy rate stands at 90%, the average in Africa is around 70%. However, this continental average does not provide us with an accurate understanding of the lived realities, as Affo���s struggles attest. Literacy rates vary widely by country; for instance, it stands at a sorry 19% in Niger and 38% in Benin. Guinea is said to have a literacy rate of 30%, 32% for South Sudan, 33% for Mali, 37% for Central African Republic, 38% for Somalia. Thus, at a time when the world is pushing to reach the ���last mile��� of literacy, an overwhelming majority in these countries can neither read nor write.

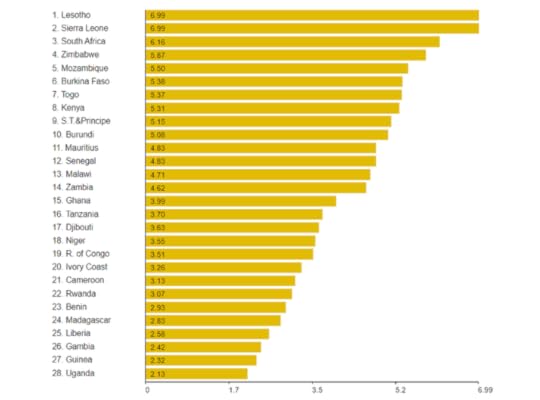

There is also the lack of commitment and prioritization with regard to education. Many African countries have pledged to commit to UNESCO���s benchmark of allocating 15-20% of the annual budget to the education sector. Yet, as the figure below���which presents the latest data on public spending on education per GDP for 28 selected African countries���shows, most have consistently failed to turn that pledge into a tangible reality. With these devastatingly wrong calls on education, the channels of cross-generational transfer of capital���symbolic or material���are fatally broken at best and, at worst, non-existent. As the region also registers the worst education spending efficiency, the social ladder is a portrait of utter anguish for the likes of Affo, with only public authorities and sound policymaking to lean on to make it to the other side of the socioeconomic divide.

Source: UNESCO (2018)

Source: UNESCO (2018)The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these dynamics by disrupting students��� education and learning. Worldwide, an estimated 1.6 billion students have been impacted by the pandemic, with more than 24 million children potentially never returning to school as a result. The disruption is even more pronounced in Africa, due to the inability to shift to remote learning in many places, especially for children from poor and rural communities. This means that many students received no education at all after schools closed across the continent in March 2020. Also significantly exacerbating pre-existing educational inequalities in the region is that students who were already most at risk of being excluded have borne the bulk of the tragedies magnified by the pandemic. Yet, we know that inequality is a deadly issue.

In some more specific contexts, insecurity coupled with health risks led to the closure of more than 1,640 schools in Mali, affecting more than 2.9 million children in the country. Following what is the world���s longest COVID-19 school shutdown, which affected 10.4 million students, about 30 percent of students in Uganda are expected to not return to school due to teen pregnancy, early marriage and child labor. Similarly, when schools reopened in Kenya in January 2021, one-third of adolescent girls and a quarter of adolescent boys between the ages of 15 and 19 didn���t return. Amid the chaos of the pandemic and the even more daunting aftermath, the World Bank warned that the COVID crisis threatens to drive unprecedented numbers of children into learning poverty. It then goes without saying that such educational challenges and inequities could further widen the already enormous gap between the rich and the poor for generations to come.

Implications and global consequencesEquitable quality education is a fundamental building block for gaining the needed skills and knowledge to meaningfully participate in society. Yet, this is fundamentally lacking in much of Africa. Though the continent receives immeasurably less international attention, it is beyond doubt that the future of the world hinges on Africa���s ability to productively harness the energies of its booming population, which will only be possible through inclusive quality education and learning. Africa is where unprecedented demographic shifts are taking place. The continent���s population will rise to 2.5 billion by 2050, more than China and India combined. Indeed, Africa���s population could well increase to a staggering 4 billion people by 2100, according to the UN. One of six people on Earth today live in Africa, and the proportion could become one of four by 2050 and more than one of three by 2100.

Furthermore, with over 60% of its population under the age of 25, Africa currently hosts the largest population of young people in the world, binding up the future of the global labor force to that of Africa. This makes education an even more pressing issue, if only because adequate investments in quality learning and training will shape the continent���s ability to transform its booming population for growth and prosperity. It will also affect nearly everything about people���s daily lives���from employment and geopolitics to migration and trade���far beyond Africa, and for generations. As Howard W. French rightly argues, the future of Africa is one of the most important questions facing humanity today.

Actions are needed, and I broadly sketch out how and what it will take for inclusive quality education to pave the way for a renewed and fairer intergenerational contract for Africa and the world.

A new education framework for Africa: The blueprint requires redesigning Africa���s education systems to fit the needs and skills of the 21st century. Most of the continent���s education systems are terribly ill-fit for purpose in the dynamic and constantly evolving job markets. Outdated curricula have left students without the practical and soft skills needed to succeed in today���s competitive world. (Not to mention the overcrowded classes, insufficient teaching materials, insufficient equipment, lack of laboratories and libraries���all of which lead to poorly educated and unemployable masses.)�� So, Africa ought to provide kids with a dynamic and adaptive education framework that is both accessible and inclusive. Such a framework should be student-centered, as well as encourage and incentivize creativity and entrepreneurship. The blueprint requires not only inputs from the students in developing adaptive curricula, but also promotes the 4Cs���critical thinking, collaboration, creativity and communication. These are the skills needed to succeed in the 21st century.

Moreover, the new blueprint also calls for strengthened partnerships with various stakeholders, including (and especially) tech companies and other private sector actors. This would play an invaluable role in helping eradicate technological illiteracy and respond to new demands, as illustrated by the outbreak of the pandemic, which forced African countries to close schools with dire consequences. The two years of pandemic have provided us with a clear glimpse of what learning will look like in the coming years. Therefore, tech companies should play a more prominent role for the Fourth Industrial Revolution to provide a lifeline to Africa���s young, eager population.

One inevitable outcome of Africa���s population boom will be a pointed rise in human-mobility. Though discussions about African mobility often come with disdain and outright racism, it is clear that better education and learning outcomes on the continent���ranging from universal literacy and schooling for girls and boys to vocational training���could create the necessary conditions for people to stay put and participate in the transformation of the continent. Even those who decide to leave would have acquired the capacity to meaningfully contribute to the growth and prosperity of their new places. This is already happening in many regions: in the US, where African immigrants have a higher level of education than both the immigrant population as a whole and the US-born population.

Finally, the education framework will necessarily be inclusive of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. Considering the fact that climate change could wipe out 15% of Africa���s GDP by 2030 and push an additional 100 million people into extreme poverty, these strategies are more than urgently needed. This means that Africa will bear some of the harshest impacts of the rising temperatures, although it contributes so little to global gas emissions and is the least financially capable of responding to the looming ecological catastrophes. This is probably the clearest illustration of environmental injustice that will haunt the continent for generations. An adaptive and dynamic education could help mitigate some of these looming crises.

Beyond the aid mindset: There is a robust literature on the undeniable pitfalls of foreign aid in Africa. But it is still worth warning African countries about relying on foreign handouts if they are to succeed in implementing the new framework needed to thrive in the tumultuous and ever-shifting post-COVID era. Just like it has done with other deficiencies, the pandemic has laid bare the many issues that result from over-reliance on foreign aid. For example, consider the multilateral Geneva-based initiative, COVAX, set up in 2020 to help supply COVID-19 vaccines to poorer countries. Due to supply shortages that resulted from vaccine-grabbing and vaccine-nationalism, COVAX has failed to meet the set goal of supplying 2 billion doses and vaccinating 20 percent of the population in these countries by the close of 2021.

Furthermore, the continent receives about $60 billion in foreign aid per year, but that is significantly less than the estimated $89 billion it loses to illicit financial flows. One clear implication, but also a central challenge, is to cut off these illicit flows and channel them towards development projects, including the financing of the adaptive and dynamic education blueprint. Clearly, the continent possesses the necessary resources to finance its educational revamping without waiting for external handouts.

In addition to breaking free from the cycle of dependency, moving beyond the aid mindset would ensure that African countries are able to set and implement their own strategic priorities with regard to renewed education.

The new education blueprint in action?As discussed above, inclusive quality education that meets the dynamic job markets is the way out of the conundrums facing Africa. Making it to the better side in the post-COVID era requires the continent to build a more secure and prosperous future for its youth. Though on a much smaller and localized scale, this is exactly what my colleagues and I strive to do at ���Educ4All,��� a grassroots initiative I founded in 2013. It promotes the crucial role education plays in emancipating and empowering marginalized communities. These communities take the driver���s seat because they know better the challenges facing them. Such initiatives are needed to promote inclusive intergenerational justice. This will allow Affo and millions of others to no longer have to commute 15km to enjoy their fundamental right to education and learning.

Pulling this off is surely a daunting task. But if William Jennings Bryan is right, then Africa���s destiny will not be a matter of chance but that of choice. Thus, Africa can no longer afford to wait for external Messiahs. Meaningful change cannot be handed out; it has to be achieved internally, and prioritizing effective and inclusive education is the right place to begin.

May 13, 2022

A man of few words

President Mwai Kibaki with Catherine Ashton. Image via European External Action Service on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

President Mwai Kibaki with Catherine Ashton. Image via European External Action Service on Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Ever since Mwai Kibaki, the third president of Kenya, died on April 21, John Githongo, Kenyan activist and former permanent secretary in charge of governance and ethics in Kibaki’s regime, has been asked to comment on his passing. Here he writes not of “hate,” but of his complex relationship with a man with whom the nation had many hopes, and one who “broke his heart.” The following article is a part of our series of reposts from The Elephant. It is curated by editorial board member and author of this post, Wangui Kimari.

We have reached a phase in Africa���s post-independence history where we cannot off the top of our head count the number of retired heads of states who are living peacefully at home or have quietly passed on into the great beyond. This is no mean achievement for the continent. Following independence from colonial rule, presidential transition was one of the things we in Africa often did badly; the tradition had long been for leaders to be shot out of power. This has changed. The eulogizing through gritted teeth of the 1970s has given way to far more elaborate and socially reassuring mourning processes. We have come a long way.

Last week Kenya and the region laid to rest Mwai Kibaki, the country���s third president since independence. Many have reached out to me for comment or to write an obituary about him. I decided not to until the funeral was over and those essential rituals had been concluded by family and nation. It���s our African way. Others sought not my comments on my time with Kibaki but some sensational attack. I explained to one, ���I don���t hate Mwai Kibaki, I never have. He isn���t a man who caused me to hate; he is someone who broke my heart.���

I had the honor of working for Mwai Kibaki from the beginning of 2003 until 2005���the shortest stint in any job during entire my professional career. Kibaki employed me as his permanent secretary in the Office of the President in charge of Governance and Ethics. I had an office at State House, in part signifying the fulfillment of the campaign promise Kibaki had made to deal with corruption once he took office. At 38, I was truly excited by this honor to serve my country and the head of state. Being based at State House was a huge deal in the Kenyan political context. Random people would walk up to me and narrate long stories of their travails at the hands of, say, the judiciary, which they felt I could resolve simply because I ���sat at State House.��� We set up a Public Complaints Unit (PCU) to handle this and the rest of what became a flood of requests, entreaties, complaints and narrations of woe that, in particular, were directed to the president by ordinary wananchi at their wits end. The PCU was transformed into the Ombudsman���s office that was originally based at Cooperative Bank Building.

In my exuberance I had forgotten my own previous writings on the intrigues and machinations that took place in that house. Within a year, I realized that what I had considered a perk was no longer a perk at all. As time passed, I was reminded that while much that was good emanated from this seat of power, often too, a darkness also arose from this place that sprung from the most craven of our desires and our base greed. I came to discover that a drought was a business opportunity for some, that the reason the caps of policemen were falling part in the rain was a contract. Even the sausages, mandazis and bottles of mineral water that were served to us so efficiently could often be a racket. Shocked not only by the price the government was paying for mineral water but also by the utter resilience of the racket that was forcing his ministry to buy the water at five-star hotel prices, one minister took to buying his own water from Uchumi Supermarket.

All leaders leave behind them a mixed legacy.

Before working for Kibaki, the most memorable story I had been told about him was of a time he attended a meeting of the Gikuyu Embu Meru Association (GEMA) in the 1970s. At this meeting the proposal was floated that every effort should be made to ensure that the presidency never leaves the Kikuyu community. Kibaki, who I was told was never that great a fan of GEMA, stood up and warned the gathering that they should not become like the monarchist Kabaka Yekka������King Only������movement and party in Uganda that had been started by elements of the Baganda elite to exclusively serve the interests of their own community. This had helped fuel anti-Baganda sentiment among the then ruling elite, comprised mainly of leaders from the north of Uganda. Kibaki was a respected leader not known for expressing emotive off-the-cuff sentiments. His ���Kabaka Yekka��� comment disrupted the entire meeting and it was left to others to recover the ground they felt his sentiments had lost them. This and other such commentaries regarding his political values made a major impression on me; they chimed with his public profile as it already was: laid back, non-confrontational, erudite, not inclined to tribal groupings and too much noise on the political stage.

When I joined his administration, the Kibaki I found myself working with fit the image I had of him. Prior to this, in 2001-2002, I had worked as part of the team that crafted his transition and anti-corruption strategy. He wasn���t a man of too many words and even though the part of his legacy that has been spoken about most glowingly is the economy, Kibaki never gave lectures about economic policy. It was almost as if his understanding and posture in regard to restabilizing the economy was implicit and he surrounded himself with people who ���got it,��� as it were. In truth, within months of taking office and inheriting a stagnated economy, he had not only turned it around, but Kenya was literally open for business again. This aspect of making Kenya a viable local and international investment destination, was his most profound legacy.

Kenyans laud Kibaki���s economic management in part because of the decline in public finance management that followed his departure. This is especially true now, in this historical moment, because it is ���legacy time��� in Kenya, with presidential transition elections less than 100 days away. President Uhuru Kenyatta is fighting to save his legacy from the damage wrought on the economy since 2013 by Jubilee���s graft that has been on a scale that it is difficult to qualify, rationalize, synthesize and even begin to coherently explain except as a form of collective delinquency. Add to this a rapidly changing global economic and political environment and a demographic youth bulge that in five short years has apparently been catapulted from being taken with the feel-good celebrity, flashy trappings of Kenyatta���s political ���bromance��� with his deputy president, to being enamored with half of the fractured pair, especially in the urban areas. For a man known as a teetotaller, Deputy President William Ruto has embarked on a hallucinogenic attempt to distance himself from the corruption.

My own sense was that Kibaki���s anti-corruption fight was important to him not only as a political deliverable to Kenyans, as he had promised, but as essential to doing what he had mapped out in his own mind to do for the economy. Kibaki set out to fight corruption recognizing that leadership choices informed the behavior of institutions rather than the other way around. In the entire time I worked with him I never bumped into people visiting him for tax waivers���an endemic problem under the previous regime. Kibaki genuinely wanted to fight corruption, especially at the beginning. In hindsight, I would say now that as politics became more complicated and cantankerous, and as relations with other NARC coalition partners grew more and more tricky to manage, and totally contrasting views vis-��-vis the raging debate around a new constitution kicked in, priorities drastically changed. It did not help that powerful commercial interests now viewed both NARC and the development of the draft constitution as it was unfolding as hostile to their personal interests. At the time, I missed the signals of the gradual transformation. As Anglo-Leasing rolled on, it became that dead rat in the rafters of our government���s hut��� it stank, we knew it was there, we pretended to search for it but understood that that dead rat was very much ours.

Mwai Kibaki was a man of few words. Dunderheads bored him unless they were sincerely amusing. He avoided confrontation at all costs; it wasn���t in his DNA. This means that he often spoke in a kind of code even when unhappy with someone or something. And silence was very much one of Kibaki���s languages. ���Hiyo maneno tutaangalia��� (That matter we shall review) usually meant no to the proposal that was being presented. ���Sikia huyu mtu sasa?!��� (Listen to this guy now?!) usually meant someone was saying something disagreeable or that he considered dumb. ���Bure kabisa!��� (Totally useless!) meant just that, whether it was in relation to a person, a group or a proposal. When he said ���Huyo wacha tuone vile ataenda��� (Let���s see how that one gets on), it was code signalling his estimation that someone had embarked on a doomed project or initiative. He had absolutely no interest in sycophants bringing him rumors and tittle-tattle (fununu and porojo) about the minor political scheming of others. That said, in what was both ultimately a strength and a weakness, Kibaki trusted and believed in old friends deeply, including, as one colleague of his from Nyeri described to me, ���the mercenaries who don���t care for him.��� For me, his dropping the ball on the corruption agenda was devastating.

In retrospect, I can also see clearly now that the seeds of the 2007-8 post-election violence were planted in 2003-4. As Kibaki settled into office, the idea of a group of political and business leaders from the Mount Kenya region���the so-called ���Mount Kenya Mafia������took root fueled by growing graft, going from myth to reality between 2004 and 2005 when the government dramatically lost the constitutional referendum held in November that year. I found it deeply ironic that the man I knew as having warned GEMA���s leaders in the 1970s about becoming an exclusivist Kabaka Yekka-type organization, now found himself leading an administration that, between 2005 and the deadly 2007 election, was consumed by the very narrative he had warned against. It culminated in the most devastating part of his legacy: the relatively brief but deadly explosion of violence that irrevocably stained his record even more than losing his grip on graft did.

I wasn���t present in Kenya when the post-election violence broke out, even though I later bore witness to the damage it wrought, first on its immediate victims, and ultimately on the fabric of the nation itself. I will leave it then, to others to comprehensively reflect on that part of his legacy. What I can comprehensively speak to is that which I witnessed up close: the disintegration of the anti-corruption agenda with which he came into office. My own ultimate impression is that, witnessing his frailty, some of Kibaki���s most steadfast allies made up their minds: ���Time may be short! Let���s make hay while the sun shines!��� And so Kibaki became a commercial vehicle for a range of actors determined to line their pockets. Indeed, the most supreme irony is that he outlived some of the more avaricious of these friends. What they started, especially vis-��-vis the acquisition of commercial debt by the Kenya government, grew from the Anglo Leasing skunk inherited from the previous regime into the behemoth that is today���s public debt load that has forced Kenya back into the hands of the very IMF that Kibaki had seen off by 2005.

The late Mwai Kibaki was impossible to hate at a personal level���he simply didn���t give one cause. He was an easy-going and effortlessly brilliant interlocutor. My most traumatic and saddening moments in public service were when we exchanged loud harsh words. But in truth, all who manage to climb the slippery political pole to the top leave both enthusiastic supporters behind them and damaged ones too. Kibaki, unlike others who have served in the position of president in Kenya and in other countries of the region, may not have been a determined destroyer of men, but he too could be a political heartbreaker and a great disappointment when he moved smoothly on, having suddenly dropped you off unexpectedly at the red lights, leaving you in the hands of some of his less scrupulous handlers.

Mwai Kibaki has shuffled off this mortal coil. May he rest in eternal peace and may his family find succor at this difficult time of the passing of a brilliant, complex man.

May 12, 2022

El maestro siempre

Still from El Maestro Laba Sosseh.

Still from El Maestro Laba Sosseh. The documentary film El Maestro Laba Sosseh (2021), directed by Maky Madiba Sylla and Lionel Bourqui, is full of pathos, guilt, regret, and nostalgia for times long gone. It is also a party���an overdue celebration of the life and legacy of the first Senegalese musician to receive a gold record.

It all started with an interview published in the Senegalese newspaper L���Observateur on June 13th, 2007. The first line: ���Admitted to the infectious diseases section of Fann Hospital, Laba Sosseh, the first African to receive a gold record, sends a cry for help.��� The article was accompanied by a disturbing picture of the man once nicknamed ���El Maestro��� for having shaped the heydays of Afro-Cuban music in Africa, particularly in Gambia, Senegal, and Ivory Coast. Sosseh, at the time 64, looked much older. As if afflicted with kwashiorkor, El Maestro was bony, his eyes were bulging, and his skin was gray. He looked nothing like the handsome international superstar he once was. ���I feel too lonely,��� he told journalist Mame Sira Konat��, whom he had summoned in order to ���unburden himself.���

Many decried this undignified picture of El Maestro. How could this happen to a man who was once so famous? His musician friends rallied to organize a telethon to help him with medical bills, but it was a little too late. Sosseh passed away on September 20th, 2007. Nothing significant was done by Senegalese state authorities to pay homage to this musical icon, who was among the first to carry the country���s name to an international stage.

Born in Bathurst���the former name of Banjul, the capital of Gambia���in 1941, Sosseh moved to Senegal in the early 1960s to join Ibra Kass�����s Star Band, one of the first orchestras in Dakar and the launchpad for stars like Youssou Ndour. Sasse and the inimitable Nigerian saxophonist Dexter Johnson formed a powerhouse duo and crystallized Afro-Cuban music in West Africa. Sasse reinterpreted Cuban classics like and El Manisero and had duos with Cuban stars such as Monguito, Roberto Torres, and Orchestra Aragon. But his greatest accomplishment was his ability to infuse the polyrhythmic Cuban sounds with West African colors, singing in Wolof, Lingala, and Gu��r�����because for him, Cuban music is quintessentially African. When his relationship with Johnson soured in 1968, Laba Sosseh left for Ivory Coast, where he enjoyed huge success under the patronage of then-President Houphouet Boigny. But when he returned to Senegal nine years later, mbalax (Senegalese pop music) had taken over and Afro-Cuban music had been buried in the memories of people from his generation. Even though El Maestro tried to resuscitate it, he too soon faded into the musical archives.

Maky Madiba Sylla is one of those who believes that Laba Sosseh deserved to be celebrated. So that���s what he does.