Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 97

June 14, 2022

The beginning is always the body

Resting head, 2020. Collage with paper pins 27.5 x 39.5cm (52.5 x 68cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery.

Resting head, 2020. Collage with paper pins 27.5 x 39.5cm (52.5 x 68cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. This interview was first published in 2021 as the introduction to the catalog of ���Frida Orupabo. Hours After,��� October 17 to November 14, 2020, at Stevenson Johannesburg. It is kindly republished here. The introduction is taken from the exhibition���s website.

In this new body of work, spanning sculpture, film and works on paper, Frida Orupabo combines fragments of colonial, personal and modern archival material sourced from digital and analog media to disassemble the politics of care, childbirth and mothering through the perspective of Black womanhood. Hints of pale color are introduced to Orupabo���s traditionally monochromatic repertoire, and domestic furnishings, once peripheral items in her tableaux, take on greater significance as she centers the contexts of her individual figures.

Elvira Dyangani OseI want to start talking about something that is very critical for your practice, and that is your use of Instagram as a laboratory, a collection of memory, a kind of archive, as well as a way to make this visible to the public. I was saying to you last time we spoke that sometimes I feel scared to go to your Instagram, and we will explore your use of imagery that is violent, that talks about aggression inflicted on bodies, on individuals, people who are part of your repertoire, your icons. It has been critical for me to follow your Instagram feed to understand how much that has a say in the way that you elaborate the work we experience in exhibitions.

Frida OrupaboI started on Instagram in 2013, if I am not mistaken. So it has been going on for a long while now, and if you go way back you���ll see mostly personal images of me and friends, images from everyday life. And then it gets less and less private���or not less private, but there are fewer and fewer images of me, my family and friends, and more and more videos, images and texts that I have found online. It was important for me to create a space where I could gather everything that was significant for me. I have a terrible memory, so my Instagram feed is also an archive that I can revisit, to remember. It is a source (among many others) for my collages. It has also functioned as a safe space for thinking out loud, and to find my own voice.

Lying with objects, 2020. Collage with paper pins 60 x 115cm (89.2 x 135.6cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose

Lying with objects, 2020. Collage with paper pins 60 x 115cm (89.2 x 135.6cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose You were observing how Instagram has been conceived to represent the self in a very particular way. There���s a sort of stream of thought that gets captured in an instant. It���s a moment of archive but also this sense of being a thought-capture, a reference, a memory, that all of a sudden is retained through that journey. And of course, as we go into critical moments of pain, of sorrow, of collective mourning, aspects of that���a sense of aggression, of violence towards bodies, towards collectives, towards cultures, certain cultures and certain communities���are also visually there. That���s why I found it so touching, so poetic, because it reflects my own experience of the world, and in a way the best artists, musicians, poets and books are those that make us feel a sense that we have been there. That, in a way, we have jumped into a different kind of existence that has somehow come into realization in the moment we are confronted with that aesthetic experience. With a sense of deep enjoyment, a sense of complete embodiment, right?

Frida OrupaboAbsolutely. And that���s why I took back what I said about it not being personal because it is highly personal still. And it is like you said: I can go back and remember where I was in that moment, in that time���emotionally, spiritually, physically. There are also many places that I don���t like to revisit. In many ways, it is a place filled with images that speak to one another; it���s a diary, it���s my life. Spending time on Instagram used to be the same as spending time in an apartment alone. Maybe some neighbors observed you, but it didn’t interfere with your mission or thoughts. Getting more followers has changed that a bit. There are multiple narratives, and we have different ways of interpreting the images that are put together. I still enjoy this process, even though I dislike Instagram more and more. It has changed so much since I started in 2013. Then it was very simple, you didn���t have to see what you didn���t want to see. Now it���s almost like watching television, with advertisements popping into your face. It distracts from the rhythm of being there and creating.

Elvira Dyangani OseIt���s interesting that you mention the disruption to narratives because this practice is very much about storytelling. At times your pieces can feel like a self-contained narrative, and also a disruption of something else. Could you take us through your creative process, and also your intention with storytelling?

Frida OrupaboIn general I spend a lot of time online.

Elvira Dyangani OseHahaha, you can say it! We like honesty here.

Frida OrupaboI seldom use images from books or physical archives. I go online and gather things that I like and put them in a file for later use. I often use Google, Tumblr or Pinterest. For instance, for the exhibition Hours After, I have been very interested in labor, pregnancy, women���s bodies, the treatment or mistreatment of the body today and historically. So this is what I have been looking for. When I feel ready I will start to work on the collages. Forcing it is never a good idea.

Alongside that I will usually play around with different images on my phone that might end up on my Instagram. It can be a narrative or just a bunch of images that speak to a feeling.�� The focus is not only on the subject (or subjects), it���s also very much on the shapes and colors. Often there can be a conflict between the message and the aesthetic.

Holy cross, 2020. Collage with paper pins 143 x 85.5cm (170.5 x 113.5cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose

Holy cross, 2020. Collage with paper pins 143 x 85.5cm (170.5 x 113.5cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose And is this conflict a need to create ambivalence?

Frida OrupaboNo. The ambivalence that I���m interested in will always be there. It���s more that the message or narrative can be very strong, or important, but if it doesn���t go aesthetically I can���t put it out.

Elvira Dyangani OseThere is something that always haunts me when I see your works live, which I have done on two occasions. It also happens when you see them online, or reproduced in print, but when you see them in person there is something haunting that takes me back to my first lessons in art history and the way that the characters in paintings look at you. There���s something very specific in your choice of a certain gaze in your collages. I feel like the agency of the people that you bring together through the collages resides mainly there. There are always certain choices where our gaze is returned to us. I wonder if you can talk a little bit about that.

Frida OrupaboMost of the images come from colonial archives, but I also use images from other sources, even paintings sometimes. When choosing images I am looking for resistance or some type of tension, especially in the way a subject sees, or stares. It forces you to stop. Resistance can also be seen in a position���how people sit or stand, how they dress, how they hold their hands.

Elvira Dyangani OseI feel like, in a way, you are liberating them from an inherent pain, a violence that the images already contain. Somehow this is promised in the work ���

Frida OrupaboThere���s something about removing the subject from the context and everything attached to it. The subjects are placed, they are undressed or dressed���they are defined from the outside. There���s also something very familiar about the stare that I recognize from my own upbringing���you know, being brought up in Norway in a predominantly white society, in a white family (except for my sister). I felt for a very long time that I was unable to speak. The only thing I had was my eyes and my anger. Anger is a form of resistance. It sends out a message to your whole body that something is wrong���that what is being done towards you is not OK, even when you remain quiet as an oyster. And so this is what I recognize in many of the images from the colonial archive���the anger and the quiet resistance.

Elvira Dyangani OseCan you elaborate a bit more about your upbringing, and how that narrative of the self comes to this persona or character that you create through your practice? The understanding of a certain kind of Blackness or ���otherness���. I was thinking as you were talking about what it means to see oneself being seen. The life experience of a Black man, a Fanon. This closeness to an observation of the other. Seeing oneself, as you said���how that had somehow marked not only your understanding of Blackness but your understanding of the human, which is something that you have also emphasized. Do you want to take us through this journey?

Frida OrupaboThe city my sister and I grew up in in the late 1980s and early 90s was predominantly white.��I remember being obsessed with images of Black people because of their absence. We hardly saw any images and when we did they were often racist, sexist ��� So the importance of visuals was created in me at a very early stage. At first I just collected images. It was not until I got my first computer that I started to manipulate and make collages. Before that I mostly painted and drew. It was important for me to create visuals where the subjects looked back. which was a direct response to my own life and experiences���to the feeling of being determined, given an identity that I didn’t understand or agree with. There is this clash between the internal you, how you see yourself, and what is projected on you from the outside. I���m interested in what that does to you as a human being.

When I had my own daughter I went back home to collect some old children���s books I used to have when I was a toddler. I remembered them as sweet but when I opened them and started to read I was shocked. Most of them had some type of racist content. Books, songs and television shows that I used to read, sing and watch were filled with racist content. You know, it���s everywhere, and when you realize that, you get a perspective on what type of environment you lived in, and you ask the question, ���how did I survive���?

Baby in belly, 2020. Collage with paper pins 60 x 122cm (89 x 149cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose

Baby in belly, 2020. Collage with paper pins 60 x 122cm (89 x 149cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose Maybe your work is your way to survive.

Frida OrupaboYes, I believe my work has been and still is essential.

Elvira Dyangani OseYou want to free your characters from a certain idea of Blackness that is imposed on them. I wonder if you could elaborate a bit more on that, how your gesture towards that occurs in the work.

Frida OrupaboI am interested in creating complex narratives���sometimes you can have several narratives alongside one another and they could be conflicting. The same thing with identity: it���s important for me to create identities or subjects that break with what we are used to seeing or hearing. I was talking to someone the other day about Blackness and identity, and I was reminded of Kathleen Collins who speaks about the importance of going against mythical characters. I���m obsessed with that. We want to fight against these stereotypes so much that we sometimes end up creating superhumans, or saints. For me this is not reality, this is not who we are; at least not who I am. We have both good and bad, ugliness and beauty, and for me that is more interesting to look into.

Elvira Dyangani OseYou feel like we recall a sense of tradition, we engage with ancestry in a different way���is there something like this in the formulation of those mythical moments of creation? You think that our origin or our world might offer a path that was denied to you in the sense of how your identity was imposed through your upbringing? Whereas now, somehow you are searching for the journey in your own terms?

Frida OrupaboI don���t know, that���s a difficult question. What I���m doing is exploring through the visuals. I���m exploring things that are going on on the inside and things that I experience around me. I am trying to make sense of it and to see the connections, often without coming to a final answer. I just know where I don���t want to go.

Elvira Dyangani OseWhere don���t you want to go?

Frida OrupaboI don���t want to create or reinforce stereotypes of superhumans, saints, strong women who carry babies, men and whole nations on their back with a smile.

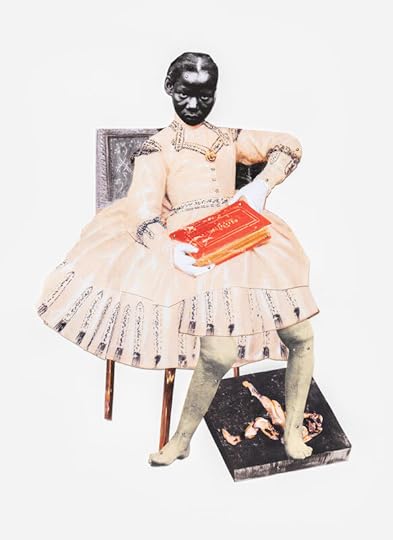

Woman with book, 2020. Collage with paper pins 97 x 72cm (125 x 100cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose

Woman with book, 2020. Collage with paper pins 97 x 72cm (125 x 100cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose We���ve been speaking about the creative process that culminates in the collages, but there���s also the display. I wonder if you can take us through what it means for you to confront the public with these images, to think about exhibition-making as the framework in which these messages are delivered.

Frida OrupaboYou know, when I work I don���t think so much. I don���t think about the selection of images���it goes automatically. The initial process happens more or less on an intuitive level. I am more conscious when I am selecting the collages I will bring into a show or a gallery space. As mentioned, it has been important for me to show subjects that stare back at the spectator (although not all of them do). I want people to feel confronted���to question their own gaze, what it is they see and why; to make them more aware about themselves than the work. This means that I have had to get rid of my shyness and fear of speaking. Because what I want to accomplish with my work will never be given; it has to be named, defined and contextualized by me.

Elvira Dyangani OseLet���s go back to your show Hours After and some of the issues you mentioned, like labor. You are working on violence and aggression towards the female body, which is something very important to your practice. I wonder if you could take us through some of the thinking that made the new series possible.

Frida OrupaboFor me the beginning is always the body. I���m very interested in how we think about different bodies, especially the Black female body. And how the body is experienced at different times, in different situations, and stages in life. The new series came forth mainly because of my own experience with pregnancy and labor. It made me want to explore these themes in more depth. I was interested in these topics prior to having my own daughter but I think what pushed me to do a whole exhibition was a need to explore my own experiences and unprocessed emotions linked to the new situation. It made me think more about motherhood and the expectations, the roles you are given and what you actually feel. It also made me go back and reread various articles about Black women���s experiences with the healthcare system, especially with regard to pregnancy, labor and mistreatment���there are plenty of horrible stories and statistics. I don���t think we have any statistics on this in Norway; this was mostly literature from the US. Anyway, around the time when I started working on my exhibition there were simultaneously lots of posts made by women on Instagram���about their own negative experiences with the healthcare system. I also had conversations with friends and family which made me question my own experiences even more.

For me the hospital was an unfamiliar domain. I felt that I lacked the tools to be able to judge and separate good, professional treatment from bad treatment due to my skin. For example, how to understand the lack of eye contact with some of the nurses and doctors, and the lack of vital information and knowledge being passed on to you about you and your baby.

Elvira Dyangani OseIt���s interesting that you mention this because I went through a process of insemination���full disclosure here!���and I am a single mom in a mono-parental family. There are several aspects that you���ve mentioned around not only the process of labor but also the carrying and, as you���ve said, how one should feel. What are the subjectivities, not only of the mother but also femininity? What is your definition of womanhood and how do you engage with it in your practice?

Frida OrupaboWomanhood …

Elvira Dyangani Ose… Yeah, and motherhood. I remember that initial sense of uncanniness���there was something uncanny about seeing a fetus growing inside me. Also this realization that there���s the process of the longing to be a mom, the anxiety, the obsession to be pregnant, and then all of a sudden there���s you and the baby and you are like, this whole thing is not about me. It���s not about me.

Frida OrupaboYeah, the change is crazy, and the emotions are running wild. In my work you often see that the mothers seem quite distant. They are holding the baby but they are staring right at you or maybe past you. Some of the collages showing mothers together with their babies feel almost hostile, turning you into an intruder once you enter the room.

I want to show loving and furious women and mothers. I believe this speaks to my own sentiments and experiences of being a mum and a woman. I am loving and furious. Things are complex and contradictory.

Labor I, 2020. Collage with paper pins 69.5 x 115cm (94.5 x 142.5cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose

Labor I, 2020. Collage with paper pins 69.5 x 115cm (94.5 x 142.5cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose There���s a comment here from Nkgopoleng Moloi that picks up on ���what you said about the power of the eye���the possibility of speaking with your eye when you can���t use words���. Could you respond to that?

Frida OrupaboI���ve never felt confident with writing or speaking. It���s only through the visuals that I really feel liberated. I think about nothing and no one. I trust my eyes completely. For me the visual is my way of speaking and that���s why it���s difficult to speak about. There are so many ways to interpret or understand a work���most times I don’t have a clear understanding of it myself���but that is also the beauty of it.

Elvira Dyangani OseI love this possibility of challenging oneself about what is understood. If I hear what you are saying correctly, there is no right or wrong here. There���s simply our perception of the work and the fact that it touches our personal memories, and that���s why it has such incredible power. Perhaps what is important in what you do is that the labor of learning and interpreting is on the side of the viewer. And being forced to do that is, I think, fundamental. Forced in the sense that sometimes it can be a punch in the face and sometimes it���s like a poetic whisper. Right?

Frida OrupaboYeah. We were speaking about the way the subject is looking at you and, as you are saying now, challenging the viewer. I forgot to say that it also challenges people to position themselves. Not everyone will do that, but this is what I want, for you to see you more than to see the work, and to question what you see and why you see the things you see. To be white often means you will see yourself as neutral���with no position, no culture, no skin. This is a dialogue that I want to have, that we all have a position and we need to acknowledge that. That���s when it becomes interesting, when you see that and acknowledge it.

In bed, 2020. Collage with paper pins 73 x 119cm (102 x 146cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose

In bed, 2020. Collage with paper pins 73 x 119cm (102 x 146cm framed). Courtesy Stevenson Gallery. Elvira Dyangani Ose One of the most interesting aspects of the recent anti-structural-racism movements is that it has become much more evident that, firstly, everyone is racialized and should be understood as such���that construct affects us all; and second, whiteness needs to be acknowledged in the sense that it established all the unconscious bias approaches within the structures that marginalize. So I feel like your work offers the viewer the possibility to understand how they are seeing, whether they see the other, the work, the artist behind the work, or themselves.

Frida OrupaboHopefully that takes place.

Elvira Dyangani OseLet���s end off with this question from my friend Khwezi Gule, director of the Johannesburg Art Gallery. He says, “I am curious why Frida���s palette is mostly black and white with a little bit of color here and there. What does that offer, what does it take away?”

Frida OrupaboInteresting question. Basically my collages are black and white because I use images from old archives. They are all in black and white or sepia. I haven���t thought much about color until recently���color is difficult, both in regards to the aesthetics and what it might symbolize. It adds new meaning. For this show, Hours After, I have added colors for the first time. As mentioned, some of the subjects I���ve been working on are linked to pregnancy, labor, birth. And the use of light colors���light pink, light green���are associated with these things ��� different fluids coming from the body, and I also find them to be colors that smell. I wanted that for the exhibition���to give it a sense of smell.

June 13, 2022

Sampa The Great’s new chapter

Photo �� Imraan Christian.

Photo �� Imraan Christian. Zambian rapper and singer Sampa the Great (Sampa Tembo), took to the stage at Sydney���s famed Opera House recently in her first Australian performance since the beginning of the pandemic. She performed two shows to open the city���s annual Vivid Festival.

At the onset of the pandemic, Tembo headed to Zambia when her father contracted COVID-19, and was unable to return due to stringent border closures. After two years, it���s as if she was teleported back to center stage with a flash of vibrant colors reflecting the nuanced landscapes of Zambia, bringing the audience to their feet in exhilaration at her concert An Afro Future.

While stuck in Zambia, placing her trust in a higher power, she focused on being ���present��� where she was planted. Tembo reconnected with her roots, collaborated with local artists, reflected on her experience as a black woman and envisioned what she wants the future to look like. The essence of this personal journey is captured in An Afro Future. ���This is a 360-degree moment for me. I went home, I reconnected with my people, we made some music together���some wild tings!��� she said to a jam-packed audience at the Joan Sutherland theater.

Tembo was born in Zambia, grew up in Botswana and lived briefly in the US, before spending some years in Australia. Music has always been part of her life, ingrained into the fabric of Zambian society, traditionally used to mark life events including weddings, graduations, general celebrations and funerals. Growing up Tembo, ���felt a sense of spiritual power singing in unison with everyone at these gatherings, often without any instruments,��� she says. Yet, it wasn���t until she first heard Tupac Shakur at the age of nine that it was game over. She instinctively knew hip hop would be her mode of self-expression.

���Walking into my cousin���s room and hearing Tupac! Yo! What is this?,��� she tells me in a tone reflecting the sense of awe and wonderment she felt when first hearing Shakur���s track Changes:

At the time, I think it was also a case of middle kid syndrome, where I felt I wasn���t being heard. I���d always written down my thoughts and feelings in my journal, it was hard for me to express myself. When I heard Tupac rap it was as if someone was speaking poetry to music. I felt it was like what I did when I wrote in my journals, and it sparked my love for expression. It was a mixture of the culture that I was in, the music I heard growing up and hip hop being that vessel that got me to where I am now���

Tembo���s ascent has been steady and impressive. She began her career in Australia, where she created her most well-known projects, The Great Mixtape (2015), The Birds and the Bee9 Mixtape (2017) earning her praise from artists like Lauren Hill and Kendrick Lamar and amassing the prestigious Australian Music Prize for Best Album of 2017. Her debut album The Return (2019), won several Australian Recording Industry Association Music Awards (ARIAs) and a second Australian Music Prize for Album of the Year���a record-breaking achievement. In 2020, she garnered the attention of Michelle Obama who included Tembo���s track Freedom on her personal Spotify Playlist. While still early in 2022, Tembo made history performing with the first Zambian band to play at Coachella and the Sydney Opera House.

���An Afro future means no limits to the way you express yourself regardless who is watching and for who is watching,��� she says. Tembo opened the show with a traditional Aboriginal custom, the Welcome to Country, signifying respect and acknowledgement of Australia���s First Nations Peoples, their ownership and custodianship of the land, their ancestors and traditions. She followed with acknowledgement of and voiced her solidarity with the black diaspora, its continued struggles but also triumphs, setting much of the tone of the show that would follow.

Tembo performed an hour-and-a-half set with an electrifying mix of hip hop, soul, Afrobeats, and traditional Zambian music. Her voice oscillating between high energy poetic flows in tracks such as Rhymes to the East, The Final Form and OMG, with softer soothing tones in songs like Lane (a new track featuring Denzel Curry) and Black Girl Magic (a song she originally wrote for her sister)���all the while masterfully commanding the stage and intoxicating the audience. Tembo also had some surprises for the audience: she performed new music, including Let Me Be Great featuring the legendary Angelique Kidjo, (who initially approached Tembo for a collaboration after seeing her perform on NPR Music) and Wildones, by Tembo���s sister and fellow singer, Mwanj�� Tembo (who joined her on stage).

Laced in between celebratory moments, were others of vulnerability where Tembo shared anecdotes. Despite an overwhelmingly white audience, she didn���t shy away from speaking about some of her experiences as a black woman existing in heavily colonized environments with the residual impacts on her own internal space. For instance, the idea of beauty, personal agency and access. She spoke of her subsequent journey of self-discovery, self-empowerment and overcoming various societal constructs imposed upon her���urging the audience to do the same in their own lives.

���This is the privilege of going back home and reconnecting with your roots,��� she says of standing in and sharing her truth despite who is watching. Accompanying her on stage was a five-piece Zambian band and six dancers who lifted the energy in the vibrantly colored but predominantly red lit intimate space, evoking a transcendent spiritual experience. ���Red is the color of blood, the thing that ultimately connects us all,��� Tembo says of choosing it as the dominant color of the show. There was a mood of nostalgia in the air, almost like a lingering affectionate hug akin to seeing an old friend after an extended period apart, yet Tembo says it wasn���t always this way. ���It definitely wasn���t as welcoming in the beginning, otherwise there���d be no need for a renaissance. Is it more welcoming now?… I think it has no choice,��� she remarks of the Australian music industry. ���The voices that were coming from young black creatives in Australia were too loud to be ignored. It garnered international attention as well and it would be foolish to pretend that this wasn���t happening in their backyard,��� she adds.

Tembo���s mighty influence on the Australian music industry is undeniable. However, she���s conscious of the artists that came before and paved the way for her, Tembo also hopes that she���s paved the way for more to come. ���I always try and make sure I use my platform to give other creatives a chance and share the stage with people who look like you, talk and feel like you,��� she says.

An Afro Future was also a chance for Tembo to evolve her artistry by incorporating more of her interests and extensions of herself live on stage by adding dance, spoken word and color. ���I thought let���s make it more theatrical,��� Tembo notes. Aware of other black creatives watching and the pressure they may feel to present in a certain way, ���I also want to show that there isn���t one way of being black. Black is everything baby!���

For Tembo���s new chapter, she confesses that she���s excited to explore more abstract expression with her visuals: ���Telling more visual stories, with music there���s no holds barred now. We���re going in any and all directions we���re inspired by and without any fear. Lane [her new track featuring Curry and accompanying video shot in Cape Town, South Africa] was the first step in working in visual expression where we���re trying everything and it���s only going to grow from there, from film to short stories and so forth.���

Welcome home

Photo �� Imraan Christian.

Photo �� Imraan Christian. Zambian-Australian rapper and singer Sampa the Great (Sampa Tembo), took to the stage at Sydney���s famed Opera House recently in her first Australian performance since the beginning of the pandemic. She performed two shows to open the city���s annual Vivid festival.

At the onset of the pandemic, Tembo headed to Zambia when her father contracted COVID-19, and was unable to return due to stringent border closures. After two years, it���s as if she was teleported back to center stage with a flash of vibrant colors reflecting the nuanced landscapes of Zambia, bringing the audience to their feet in exhilaration at her concert An Afro Future.

While stuck in Zambia, placing her trust in a higher power, she focused on being ���present��� where she was planted. Tembo reconnected with her roots, collaborated with local artists, reflected on her experience as a black woman and envisioned what she wants the future to look like. The essence of this personal journey is captured in An Afro Future. ���This is a 360-degree moment for me. I went home, I reconnected with my people, we made some music together���some wild tings!��� she said to a jam-packed audience at the Joan Sutherland theater.

Tembo was born in Zambia, grew up in Botswana and lived briefly in the US, before relocating to Australia where she���s now based. Music has always been part of her life, ingrained into the fabric of Zambian society, traditionally used to mark life events including weddings, graduations, general celebrations and funerals. Growing up Tembo, ���felt a sense of spiritual power singing in unison with everyone at these gatherings, often without any instruments,��� she says. Yet, it wasn���t until she first heard Tupac Shakur at the age of nine that it was game over. She instinctively knew hip hop would be her mode of self-expression.

���Walking into my cousin���s room and hearing Tupac! Yo! What is this?,��� she tells me in a tone reflecting the sense of awe and wonderment she felt when first hearing Shakur���s track Changes:

At the time, I think it was also a case of middle kid syndrome, where I felt I wasn���t being heard. I���d always written down my thoughts and feelings in my journal, it was hard for me to express myself. When I heard Tupac rap it was as if someone was speaking poetry to music. I felt it was like what I did when I wrote in my journals, and it sparked my love for expression. It was a mixture of the culture that I was in, the music I heard growing up and hip hop being that vessel that got me to where I am now���

Tembo���s ascent has been steady and impressive. She began her career in Australia, where she created her most well-known projects, The Great Mixtape (2015), The Birds and the Bee9 Mixtape (2017) earning her praise from artists like Lauren Hill and Kendrick Lamar and amassing the prestigious Australian Music Prize for Best Album of 2017. Her debut album The Return (2019), won several Australian Recording Industry Association Music Awards (ARIAs) and a second Australian Music Prize for Album of the Year���a record-breaking achievement. In 2020, she garnered the attention of Michelle Obama who included Tembo���s track Freedom on her personal Spotify Playlist. While still early in 2022, Tembo made history performing with the first Zambian band to play at Coachella and the Sydney Opera House.

���An Afro future means no limits to the way you express yourself regardless who is watching and for who is watching,��� she says. Tembo opened the show with a traditional Aboriginal custom, the Welcome to Country, signifying respect and acknowledgement of Australia���s First Nations Peoples, their ownership and custodianship of the land, their ancestors and traditions. She followed with acknowledgement of and voiced her solidarity with the black diaspora, its continued struggles but also triumphs, setting much of the tone of the show that would follow.

Tembo performed an hour-and-a-half set with an electrifying mix of hip hop, soul, Afrobeats, and traditional Zambian music. Her voice oscillating between high energy poetic flows in tracks such as Rhymes to the East, The Final Form and OMG, with softer soothing tones in songs like Lane (a new track featuring Denzel Curry) and Black Girl Magic (a song she originally wrote for her sister)���all the while masterfully commanding the stage and intoxicating the audience. Tembo also had some surprises for the audience: she performed new music, including Let Me Be Great featuring the legendary Angelique Kidjo, (who initially approached Tembo for a collaboration after seeing her perform on NPR Music) and Wildones, by Tembo���s sister and fellow singer, Mwanj�� Tembo (who joined her on stage).

Laced in between celebratory moments, were others of vulnerability where Tembo shared anecdotes. Despite an overwhelmingly white audience, she didn���t shy away from speaking about some of her experiences as a black woman existing in heavily colonized environments with the residual impacts on her own internal space. For instance, the idea of beauty, personal agency and access. She spoke of her subsequent journey of self-discovery, self-empowerment and overcoming various societal constructs imposed upon her���urging the audience to do the same in their own lives.

���This is the privilege of going back home and reconnecting with your roots,��� she says of standing in and sharing her truth despite who is watching. Accompanying her on stage was a five-piece Zambian band and six dancers who lifted the energy in the vibrantly colored but predominantly red lit intimate space, evoking a transcendent spiritual experience. ���Red is the color of blood, the thing that ultimately connects us all,��� Tembo says of choosing it as the dominant color of the show. There was a mood of nostalgia in the air, almost like a lingering affectionate hug akin to seeing an old friend after an extended period apart, yet Tembo says it wasn���t always this way. ���It definitely wasn���t as welcoming in the beginning, otherwise there���d be no need for a renaissance. Is it more welcoming now?… I think it has no choice,��� she remarks of the Australian music industry. ���The voices that were coming from young black creatives in Australia were too loud to be ignored. It garnered international attention as well and it would be foolish to pretend that this wasn���t happening in their backyard,��� she adds.

Tembo���s mighty influence on the Australian music industry is undeniable. However, she���s conscious of the artists that came before and paved the way for her, Tembo also hopes that she���s paved the way for more to come. ���I always try and make sure I use my platform to give other creatives a chance and share the stage with people who look like you, talk and feel like you,��� she says.

An Afro Future was also a chance for Tembo to evolve her artistry by incorporating more of her interests and extensions of herself live on stage by adding dance, spoken word and color. ���I thought let���s make it more theatrical,��� Tembo notes. Aware of other black creatives watching and the pressure they may feel to present in a certain way, ���I also want to show that there isn���t one way of being black. Black is everything baby!���

For Tembo���s new chapter, she confesses that she���s excited to explore more abstract expression with her visuals: ���Telling more visual stories, with music there���s no holds barred now. We���re going in any and all directions we���re inspired by and without any fear. Lane [her new track featuring Curry and accompanying video shot in Cape Town, South Africa] was the first step in working in visual expression where we���re trying everything and it���s only going to grow from there, from film to short stories and so forth.���

The UK and migrant men from the Global South

Photo by Alistair MacRobert on Unsplash

Photo by Alistair MacRobert on Unsplash Ann Stoler, professor of anthropology and historical studies at The New School, calls it ���colonial aphasia.��� She borrows the definition from a medical condition that affects someone���s ability to communicate after a stroke or head injury. The patient can forget how to write and understand spoken and written language. Colonial aphasia challenges what some of us may know as ���colonial ignorance������a form of denialism that relies on a purported lack of knowledge of colonial pasts and their present-day relevance. In a way, ���colonial ignorance��� denotes a passive phenomenon, amnesia of sorts. Yet, as Stoler reminds us, colonial histories are ���neither forgotten nor absent from contemporary life.��� They are here, with us, and felt disproportionately by particular bodies. Instead, ���aphasia��� recognizes the active act of forgetting, a concerted political and personal act that occludes the protracted temporalities of colonialism and diminishes our ability to retrieve language to make sense of how we see colonialism manifesting in our everyday lives.

UK Home Secretary Priti Patel���s speech announcing the UK plan to send single young male asylum seekers to Rwanda typified this idea of colonial aphasia. As in most of her speeches, Patel articulated this aphasia with great confidence and eloquence: ���The United Kingdom has a long and proud history of offering sanctuary to refugees,��� she tells us. Perhaps it is worth revisiting our past to understand how deeply fabricated this statement is.

The UK���s immigration system has its roots in racism and colonialism. By tracking the colonial roots of legal categorizations, we see how immigration laws in the UK included and excluded certain people from legal status in order to legitimize colonial power. These policies emerged soon after the formal end of colonialism to control the entry of the racialized poor into Britain and to ensure the immobility of others, notably former colonial subjects such as Caribbean���mainly Black���and South Asian migrants. In this sense, Britain has a longstanding history of draconian immigration policies, from implementing indefinite immigration detention to the deeply racialized postwar immigration controls that followed the Windrush immigration of the 1940s and 1950s���controls which White politicians justified by claiming that immigration would cause irreparable damage to the ���racial character of the English people.���

More recently, the degree to which British immigration is so exhaustively racialized and gendered is manifest in an agreement between the UK and Rwanda to send single young male asylum seekers to Rwanda���not for offshore processing to then be settled in the UK, but as a permanent destination. Although there has been much criticism of this latest policy within the UK and elsewhere, little has been said about why it is single young men that are the primary target of this policy. Here again, we need to revisit our history to understand how this came to be.

The British empire was pivotal in shaping global understandings of race and gender. Modern Euro-American states like Britain coproduced and reproduced���and, whenever necessary, rearticulated���the conditions and terms of society���s racial character, which is complexly entangled with gender, nationality, sexuality, class, and religion. Gender was indispensable to this articulation. As feminist scholar Anne McClintock reminds us, ���gender dynamics were, from the outset, fundamental to the securing and maintenance of the imperial enterprise.��� Conquest was in part legitimized on the basis of colonial imageries about colonized men and their masculinity���for instance, as hypersexualized, violent, and threatening, especially to White European women. In this way, Britain has long been preoccupied with state-directed racial, classed, and gendered exclusions, as evident in its segregation, immigration, and carceral policies, especially of poor Black and Brown men.

It is within this context that we must understand why men from the Global South���men predominantly from Africa and the Middle East���are the target of this policy. Men from the Global South are the subject of this policy because they are often demonized by alarmist media and policy discourses across Europe, including in the UK. These discourses often invoke colonial tropes such as Black African men being inherently patriarchal, ���brutish,��� ���criminal,��� ���promiscuous,��� and carriers of disease, or stereotypes of Islam as the embodiment of unfathomable extremism and excessive violence. In this sense, their identities are not only understood as inherently threatening, but also incompatible with the vulnerability that could secure them refugeehood in the UK.

Sexuality and age also play a crucial role in signaling who is supposedly a threat to UK citizens and the UK government. The use of ���single��� and ���young��� by the Home Office is instructive in telling the public who should be feared. In the UK in particular, the notion of the ���lone��� racialized ���youth��� has historically been used to criminalize Black and Brown British male youth and adult men; their ���deviant��� and ���criminal��� behavior is pathologized by ascribing blame to their ���dysfunctional��� family units. In the image of the Global North, families are based on the idea of a heterosexual family romance, in which there is a father, mother, and a couple of children. This family unit contrasts with family units from ���cultures of deprivation,��� where ���inadequate family structures��� are perceived to exist: the notoriously absent father, the mother who has borne too many children, and similar dynamics. Single men seeking asylum from the Global South are considered racialized and sexualized figures without normative families and therefore incompatible with ���British culture.���

Indeed, the presence of young�� Black and Brown single men from Africa and the Middle East in Europe raises angst about White feminine sexuality and racial purity. To allow for consorting between Black bodies (whether Black African or Arab/Muslim) and White female ones would result in a change in the nation���s color through the offspring of such relationships. For those racialized as White, it would amount to conceding White demographic power over public spaces���and, finally, conceding the entire nation and its future.

And so here we are. If we are to truly grasp the full significance of the agreement between the UK and the government of Rwanda, we must see how it relies on a sophisticated form of colonial aphasia that plays on widely circulated and popular ideas about single, young, racialized men being inherently threatening and incompatible with vulnerability. The severance of these immigration policies from their colonial origins conceals that their contemporary effects are ongoing expressions of empire and global racial ordering.

June 10, 2022

It takes a team to raise an athlete

Sharlan Boer, coach Norman Ontong and Chenique Sas. Courtesy of Norman Ontong ��.

Sharlan Boer, coach Norman Ontong and Chenique Sas. Courtesy of Norman Ontong ��. On April 22, 17-year-old Chenique Sas ran her personal best (PB) at the Athletics South Africa (ASA) Senior Track and Field National Championships at Green Point Athletics Stadium in Cape Town to win gold in the 3,000-meter steeplechase. In its summary of the event, ASA reported: ���Chenique Sas collapsed at the finish after a tough 3 000m steeplechase race in 10:43.20, narrowly holding off Lizandre Mulder (10:44.14) ������

Steeplechase is known for being among the toughest track-and-field events. Although this was a ���pure klas��� (pure class) achievement for Sas, as various local newspapers reported, the focus on her ���collapsing��� or ���exhaustion��� fails to capture the significance of her victory. The story of struggle and sacrifice in the making of an athlete is not for governing bodies like ASA to tell. To unpack such stories requires attending to the athletes who crossed the finish line a few seconds later, the coach who remains unnamed, and the team that nurtures children against all odds.

Let���s start with the athlete Sas ���held off.��� Lizandre Mulder runs for Free State. She is white. Sas runs for Boland. She is coloured. Mulder recently graduated with a law degree from the University of the Free State and is set up for a successful career, with or without athletics. Sas, on the other hand, is at HTS Drostdy, previously a whites-only school, only because of her athletics achievements. Neither her material circumstances, nor her grades, would have qualified her to attend this school. Mulder trains alongside the likes of Olympian Wayde van Niekerk and Paralympian Louzanne Coetzee, at the state-of-the-art sports facilities of KovsieSport. Sas trains with a volunteer organization, almost persona non grata in athletics circles.

Still, this was not the first time Sas outran Mulder, seven years her senior and better known among the race officials and commentators. The last time Sas beat Mulder was at the Athletes Academy Invitational on March 28, where the two athletes pushed each other to achieve their individual PBs in the 3,000m steeplechase. Sas might continue to enter future competitions as an underdog, but on the running track the Sas-Mulder combo has all the makings of a healthy rivalry.

Chenique Sas is a member of Fit2Run, a small non-profit initiative run entirely by volunteers. It was established in 2008, when a group of committed runners and schoolteachers in Worcester and adjoining farmlands area observed, year after year, that while the primary school athletics competitions were dominated by coloured and African athletes from underprivileged backgrounds, the secondary school competitions were dominated by white athletes from privileged backgrounds. Their first response to support the talented primary school athletes was to introduce them to the local athletics club. But they soon found that the athletics club had no program for juniors and members were unwelcoming to children from poorer backgrounds. This is when Norman Ontong (Sas���s coach) and colleagues decided to set up Fit2Run, which would focus primarily on junior athletes.

In 2011, Fit2Run, based in Worcester, a small town 120km northeast of Cape Town, was finally ratified as an athletics club by Boland Athletics, the regional athletics federation, affiliated to Athletics South Africa (ASA). However, the ���club��� status was revoked before long. As Ontong shares in a chapter we co-wrote about Fit2Run for a book on physical culture in South Africa:

Based on Boland Athletics��� policy of ���one club per town or municipal area��� (Boland Athletics, 2012: sec.31.4.7), ostensibly put in place to unify racially separated athletics clubs in each town under apartheid, WAC [Worcester Athletic Club, the local athletics club] filed an objection against Fit2Run Athletics Club. We soon found ourselves in a legal battle with Boland Athletics, who won the case. By the end of 2012, they retracted our club status.

On the same day of her greatest achievement thus far, Sas also had her training partner, Sharlan Boer, running the finals. Boer runs for Western Province. She is a friend and a mentor to Sas. While both athletes train under the expert guidance of Ontong at Fit2Run���s training facilities, they run for different clubs, affiliated with different athletics federations within the Western Cape Province. This is one of the ramifications of the retraction of Fit2Run as an athletics club. Western Cape is the only province in the country with three provincial athletics governing bodies, despite the government’s mandate to have one provincial governing body per sporting code.

Not only is it expensive to compete as independent athletes, the Fit2Run athletes also end up running for different clubs affiliated with different federations. This effaces Fit2Run and the many struggles and sacrifices behind the success of the likes of Sas. It effaces the work of coaches and volunteers, who bear the burden of the legacies of apartheid but cannot be acknowledged when they tackle the socio-economic class manifestations of racist policies that remain in post-apartheid South Africa.

Communication scholars have pointed to how sports commentaries remain racialized, wherein which black athletes are repeatedly congratulated for their ���natural��� talent and white athletes for their technical skill and intelligence. The behind-the-scenes work, analysis, last-minute adjusting of race strategy, and care practiced by black athletes and coaches is lost in the way athletics results are reported by controlling bodies like ASA or sports media. The following example from Ontong, an experienced and successful runner, coach, and a meticulous student of the sport is instructive. It shows how strategy was adjusted, after consideration of the line-up of the final race:

The time [of Sas] was fastest but Kristy Bell was named as the favorite [to win the race]. I analyzed all the athletes in her [Sas���s] race. One hour before the SAs [the race], we changed plans. Our original plan was to go for the qualifying time for the World Youth (U20) Championships in Colombia, later this year (August 2-7), no matter if we came 3rd. When I analyzed the other athletes, I recognized that Sharlan was the fastest in a 2000m SC, Chenique 2nd and Bell 3rd. So, we decided to go for the win. That���s why Sharlan was in front for the first 3 rounds.

There was not enough info about the athletes��� 3000m SC races. That’s why I went back to their 2000m SC times. We didn���t worry about Mulder because Chenique beat her 4 weeks before [in the same event]. But Mulder came back really good.

Given the much-celebrated speech of former president Nelson Mandela that ���sports have the power to change the world,��� one would think that organizations such as Fit2Run would receive active support. Yet, its struggle to exist tells a more sobering tale. Fit2Run�� continues as a non-profit organization, affirming that it is not sports, but individual and collective commitments that can change the world. But such changes require sacrifices and endurance to overcome the odds. Rather than earning a living from their professional expertise and experience in athletics, Ontong and his colleagues have taken to nurturing athletes for whom they will forever be raising funds. Increasing specialization in track-and-field, road-running, and cross-country, means that athletics is no longer the cheap sport it is often made out to be. The difference between collapsing at the finish line and finishing the race with raised arms is related to good(and often expensive) nutrition.

The real success of Fit2Run is personified more by Sharlan Boer than Chenique Sas. Boer has been with Fit2Run from the beginning of the organization. It is no surprise that she would run a race to her coach���s strategy to ensure Sas���s victory. Boer holds many regional records in her main events and regularly qualifies for nationals. At this stage, she is less likely to break any national or world records, but she is already mentoring upcoming athletes at Fit2Run.

A recent New Frame article about Keegan van der Merwe, a 26-year-old working class�� coloured athlete from Mitchell���s Plain in the Western Cape, puts the work Fit2Run does in perspective. Despite commitment, talent, and grit, the level of athletics success Van der Merwe aspires to has thus far eluded him. His story also points to the neglected ���sports development��� that organizations like Fit2Run try to address. In the absence of Fit2Run, the stories of Boer, Sas and hundreds of other young athletes from Worcester���s coloured and black townships that Fit2Run caters for, would be similar to Keegan van der Merwe���s..

Sas has potential and time on her side to chase the world record in the steeplechase. And when she does, South Africans from all walks will not only cheer her on and celebrate all her victories as their own (as they have for Caster Semenya and Wayde van Niekerk), but also will admire the courage, struggles, and sacrifices she has made to achieve such success. However, there are few South Africans the likes of Ontong and his team. Whether she breaks the world record or not, Sas is assured that Fit2Run will be there to help drive her success and that of other aspiring athletes..,

June 9, 2022

What���s the matter with private equity in Africa?

The Edro III is a Sierra Leone flagged cargo ship that stranded in the Sea-cave area near Paphos (Cyprus). Image credit Tobias Van Der Elst via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

The Edro III is a Sierra Leone flagged cargo ship that stranded in the Sea-cave area near Paphos (Cyprus). Image credit Tobias Van Der Elst via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. Anyone curious about the future of capitalism in Africa might want to take a look at the Sierra Investment Fund (SIF). In 2006, Freetown-based ManoCap, a private equity (PE) firm with a social responsibility bent , launched SIF to invest in Sierra Leonean companies. The CDC Group, a UK government agency, contributed $5 million to the endeavor.

Money in hand, SIF���s managers at ManoCap went to work. In October 2008, they made their first purchase: a half century-old seafood company called Sierra Fishing Company. The next month, they made two more buys: an ice maker called Ice Ice Baby��� which sold ice, primarily to the local fishing industry���and a mobile payments company.

If the fund���s strategy wasn���t clear after its first year, it was in October 2009 when it cut its fourth and final deal, for a Freeotwn trucking company called Dragon Transportation which, in the CDC���s words, ���provides transport services to the Sierra Leonean market with a focus on the distribution of fish, ice, and other perishables.���

Thirteen years later, the CDC (now called British International Investment) still holds an ���active��� investment in SIF, according to its website. Though few people know it, British taxpayers own a stake in the biggest and most tightly integrated seafood operation in Sierra Leone.

For investors looking to bank on the ���Africa rising��� story, PE has proven the surest vehicle for success. Last year, the industry pumped $7.1 billion into African companies, beating the 2017 record by more than $2 billion. It���s easy to see why investors would want to place their bets on the continent: out of 30 countries that recorded an average growth rate above four percent from 2016-2020, 14 were in Africa. But stock exchanges��� the standard means for investing in companies in developed countries��� are generally weak in Africa.

Even where exchanges exist, investors want guides��� people who know ���how things work��� and see opportunities they can���t. Since African businesses��� even really successful ones��� often do not adhere to international standards for industries they operate in, investors also want people who can hold them to those standards so as to make them resemble more closely the European or American companies they���re used to. Private equity does all of that.

In Africa, PE is staking claims in everything from hotels to private schools, poultry farms to bottling plants. Wherever it goes, it���s creating new pathways for investors to introduce capital and influence to African economies. Given PE���s rising influence in Africa, it���s important to consider how activists might influence the industry. To understand how one might do that, it helps to understand how PE works.

Private equity begins with a partnership. On one side is the PE firm��� the ���general partners,��� or ���fund managers��� in industry terminology. On the other side is an assortment of outside investors, known as the ���limited partners.��� Private equity funds all over the world typically recruit public entities as investors, from pension funds to university endowments. Funds operating in Africa attract the same groups, but to them, they typically add development finance institutions (DFIs), like British International Investment or the International Finance Corporation, the private-sector lending arm of the World Bank Group. (A research project I conducted with Joeva Rock for a consortium led by the advocacy group Thousand Currents, found that more than half of funds investing in Africa from 2006-2018 had received DFI support.)

For outside investors, PE means access to tremendous power: using their money, fund managers not only buy stakes in companies, they also apply their expertise in business and finance to make them bigger and more profitable. But although both sides pool their money in a single fund, only the fund managers decide where the money goes.

Consider the example of Resource Capital Fund VII, a fund invested in mining companies active in Burkina Faso and Guinea. According to the terms of the partnership, which I obtained through a public records request, the fund managers reserved the sole right to choose where to invest the money. They didn���t even have to tell the outside investors where they planned to invest ahead of time. From the time investors signed the agreement, they could expect the fund to hold their capital for 10 years���a standard lifetime for a PE fund. That is, unless the fund managers decided to keep the money for another two, in which case they reserved the right to do so with or without the outside investors��� consent.

Even the normal path of recourse for an investor scorned���the courts���were limited under this agreement. By signing it, investors waived their right to a jury trial and agreed to only bring a lawsuit in the country where the fund was domiciled���in this case, the notoriously business-friendly jurisdiction of the Cayman Islands.

So how can people hold the PE industry to account? Though pension funds sometimes act as though their first responsibility is to capital, and not to their constituents, they are not beyond the influence of a committed public. In 2020, a coalition of unions and advocacy groups in New York compelled the state legislature to mandate pension divestment from fossil fuels and increase investments in clean energy. The new rules only applied to ���public equities,��� or investments traded on stock markets, but one could see how similar coalitions could direct their attention to PE. To begin with, they could tell investing bodies to ask fund managers questions. They could also insist that fund managers sign binding human rights and environmental commitments and disclose where they intend to invest. The PE industry is competitive: if pension funds and endowments don���t like what they hear, or if the managers for one fund refused to make any concessions, they could always take their money to another.

What is critical to remember is that once they invest in a PE fund, outside investors will likely have little to no power to influence it. After they���ve committed their capital, it may be too late to force change, no matter how much they���ve invested, or how urgently the world needs it.

June 8, 2022

Navigating queer utopia

Pride Johannesburg 2013. Image credit Niko Knigge via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Pride Johannesburg 2013. Image credit Niko Knigge via Flickr CC BY 2.0. The book Seeking Sanctuary: Stories of Sexuality, Faith and Migration is a compilation of the stories of fourteen queer African Christians who have migrated to (and within) South Africa. These stories are contextualized within the LGBT Ministry of the Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Braamfontein, Johannesburg. Here, we encounter the narratives of lesbian, gay, and trans-identifying Africans in their own voices. They represent diverse country contexts, including Zimbabwe (Dumisani, D.C., Thomars, Mike, Tino, Toya, Tinashe), Cameroon (Mr. D), Ethiopia (Eeyban), Zambia (Dancio), Nigeria (Sly), Uganda (Angel), South Africa (Zee), and Lesotho (Nkady). The author, John Marnell, is honest about the predominance of gay men���s and Zimbabwean men���s narratives in the book. While this may not be representative of the migrant population in South Africa, it is perhaps reflective of the relative safety and agency available to various groups.

The collection addresses a particularly notable gap on migrants and migration in research on Christianity and sexuality in southern Africa. These narratives have often been sidelined as researchers, including myself, have been more interested in exploring the Christian queer subject who remains at home, within their religious institution or country, despite anti-queer doctrines, policies, and legislation. While these studies have generated important insights into how queer people navigate oppressive or exclusionary contexts, the diverse narratives in Seeking Sanctuary highlight the significance of exploring movement, boundary-crossing, and liminality in religious and queer studies in Africa.

Seeking Sanctuary stands alongside other publications���such as Stories of Our Lives, by the NEST Collective in Kenya, and Sacred Queer Stories: Ugandan LGBTQ+ Refugee Lives and the Bible, by Adriaan van Klinken and Johanna Stiebert with Sebyala Brian and Fredrick Hudson���in building an archive of queer, African, and religious narratives. In Van Klinken���s words, the multiplicity of stories compiled in the book, like its interlocutors, ���challenge[s] the overall silence and taboo surrounding homosexuality and sexual diversity in African theology.��� Seeking Sanctuary is unique, however, in that it provides an empirical challenge to the myth of South African queer exceptionalism. South Africa is often portrayed as ���Africa���s gay capital��� because unlike elsewhere in Africa, it enshrines protections on the basis of sexual orientation in its constitution and was the fifth country in the world to legalize same-sex unions in 2006. This reputation, however, is proven flimsy at best. The spate of killings of queer people throughout South Africa, which caused public outcry in early 2021, is evidence that this idea is not based on the realities of people���s lives. Similarly, this collection shows the tenuous nature of queer freedoms in South Africa.

The stories in Seeking Sanctuary do not paint a binary picture of contributors��� home countries as oppressive and violent and South Africa as the land of milk and honey. Their narratives are complex and nuanced, with many stories telling us about loving homes and families and idyllic, sometimes even privileged, childhoods. In contrast, many of the contributors experience violence, discrimination, corruption, and liminality in South Africa. There is a longing evident in many of the narratives to leave South Africa, if only their home countries��� laws would change or if only they could be freer about their sexuality with their family or community.

Indeed, South Africa is not a queer utopia. It seems that merely the potential and promise of safety (however limited) that lies within South Africa���s constitutional protections and its political discourse around queer freedoms is enough to convince many migrants to remain within its borders. Class matters: notably, it seems that in large part, those who were already relatively financially privileged in their home country are the ones able to access some of this potential for safety and stability. For many, the prevalence of xenophobia pushes them to seek out security and networks within already established migrant communities in South Africa, yet queerphobia pushes them to find belonging and connection in queer South African communities. This liminality places them in especially vulnerable positions, and there are few examples in any of the contributions that express genuine experiences of sustained belonging, security, and safety.

While not primarily a theological text, Seeking Sanctuary also contributes to the emerging body of scholarship producing ordinary queer theologies in Africa. The book reminds us again, as Black feminists have consistently done, that ���stories are data with soul.��� The soul within these narratives brings to life the ways in which love, compassion, justice, and charity can be queered. Significantly, we see in the book how these meanings are constructed in relation to the various versions of Christianity in which narrators locate their spiritual formation���versions which include forms of Methodism, Anglicanism, and Pentecostalism, to name a few. Further, because the LGBT Ministry featured in Seeking Sanctuary is within a Catholic congregation, the book also begins to engage with Catholicism in South Africa���a particularly under-researched site. The stories of the ministry���s founders, Father Russell Pollit and Ricus Dullaert, and the current leader of the ministry, Dumisani, combined with the narratives of those who have sought sanctuary in this group, demonstrate the practicalities and challenges that accompany establishing affirming religious spaces.

The stories featured in Seeking Sanctuary are courageous, resistant, critical, insightful, and instructive. This book is an exceptional gift for activists, scholars, and allies who seek to queer their religious homes and/or provide a place of healing and affirmation for others. The migrant narratives featured in Seeking Sanctuary allow readers to empathize with the lived experiences and humanity of those often placed on the margins of South African society in unique ways. This in itself is a worthy contribution, as the stories serve as useful catalysts for dialogue within and between queer Christians, religious institutions, and perhaps political bodies, too. This book carries this potential largely because of the courage of those who tell their stories. The contributors remind us, in their narratives, of how easy it is for them to become targets of violence and persecution, which they experience within their families and communities (born into, found, and created) or at the hands of state officials, public servants, and religious authorities in South Africa and their home countries.

Their stories also highlight the unique and intersecting systems of oppression that shape their everyday lives, including queerphobia, xenophobia, underemployment, and poverty. These structural realities shape contributors��� different pathways to (and also within) South African borders of citizenship and belonging and point to the immense task that remains in realizing the potential of South Africa���s constitutional ideals. Contributors��� expressed hopefulness in relation to their experiences with the LGBT Ministry, also serves as a challenge to religious institutions in South Africa to engage in the possibilities of creating queerer forms of ministry���even when their official theological stances may not be queer affirming. These written stories serve as an illustration of small victories that have been won in religious spaces in Africa and, perhaps more importantly, as a reminder that there are still many stories to be told and much work to be done.

When Egypt was Black

Photo by Sumit Mangela on Unsplash

Photo by Sumit Mangela on Unsplash In his monumental 1996 book Race: The History of an Idea in the West, Ivan Hannaford attempted to write the first comprehensive history of the meanings of race. After surveying 2,500 years��� worth of writing, his conclusion was that race, in the sense in which it is commonly understood today, is a relatively new concept denoting the idea that humans are naturally organized into social groups. Membership in these groups is indicated by certain physical characteristics, which reproduce themselves biologically from generation to generation.

Hannaford argues that where scholars have identified this biological essentialist approach to race in their readings of ancient texts, they have projected contemporary racism back in time. Instead of racial classifications, Hannaford insists that the Ancient Greeks, for example, used a political schema that ordered the world into citizens and barbarians, while the medieval period was underwritten by a categorization based on religious faith (Jews, Christians, and Muslims). It was not until the 19th century that these ideas became concretely conceptualized; according to Hannaford, the period from 1870 to 1914 was the ���high point��� of the idea of race.

Part of my research on the history of British colonial Egypt focuses on how the concept of a unique Egyptian race took shape at this time. By 1870, Egypt was firmly within the Ottoman fold. The notion of a ���Pan-Islamic��� coalition between the British and the Ottomans had been advanced for a generation at this point: between the two empires, they were thought to rule over the majority of the world���s Muslims.

But British race science also began to take shape around this time, in conversation with shifts in policy throughout the British empire. The mutiny of Bengali troops in the late 1850s had provoked a sense of disappointment in earlier attempts to ���civilize��� British India. As a result, racial disdain toward non-European people was reinforced. With the publication of Charles Darwin���s works, these attitudes became overlaid with a veneer of popular science.

When a series of high-profile acts of violence involving Christian communities became a cause c��l��bre in the European press, the Ottomans became associated with a unique form of Muslim ���fanaticism��� in the eyes of the British public. The notion of Muslim fanaticism was articulated in the scientific idioms of the time, culminating in what historian Cemil Aydin calls ���the racialization of Muslims.��� As part of this process, the British moved away from their alliance with the Ottomans: they looked the other way when Russians supported Balkan Christian nationalists in the 1870s and allied with their longtime rivals in Europe to encroach on the financial prerogatives of the Ottoman government in Egypt.

Intellectuals in Egypt were aware of these shifts, and they countered by insisting they were part of an ���Islamic civilization��� that, while essentially different from white Christians, did not deserve to be grouped with ���savages.��� Jamal al-Din al-Afghani was one of the most prominent voices speaking against the denigration of Muslims at the time. His essays, however, were ironically influenced by the same social Darwinism he sought to critique.

For example, in ���Racism in the Islamic Religion,��� an 1884 article from the famous Islamic modernist publication al-Urwa al-Wuthqa (The Indissoluble Bond), Afghani argued that humans were forced, after a long period of struggle, ���to join up on the basis of descent in varying degrees until they formed races and dispersed themselves into nations … so that each group of them, through the conjoined power of its individual members, could protect its own interests from the attacks of other groups.���

The word that I have translated as ���nation��� here is the Arabic term umma. In the Qur���an, umma means a group of people to whom God has sent a prophet. The umma Muhammadiyya, in this sense, transcended social differences like tribe and clan. But the term is used by al-Afghani in this essay to refer to other racial or national groupings like the Indians, English, Russians, and Turks.

Coming at a time when British imperial officials were thinking about Muslims as a race, the term umma took on new meanings and indexed a popular slippage between older notions of community based on faith and modern ideas about race science. Al-Afghani���s hybrid approach to thinking about human social groups would go on to influence a rising generation of intellectuals and activists in Egypt���but the locus of their effort would shift from the umma of Muslims to an umma of Egyptians.

In my book, The Egyptian Labor Corps: Race, Space, and Place in the First World War, I show how the period from 1914 to 1918 was a major turning point in this process. At the outbreak of the war, British authorities were hesitant to fight the Ottoman sultan, who called himself the caliph, because their understanding of Muslims as a race meant that they would naturally have to contend with internal revolts in Egypt and India. However, once war was formally declared on the Ottomans and the sultan/caliph���s call for jihad went largely unanswered, British authorities changed the way they thought about Egyptians.

Over the course of the war, British authorities would increasingly look at Egyptians just as they did other racialized subjects of their empire. Egypt was officially declared a protectorate, Egyptians were recruited into the so-called ���Coloured Labour Corps,��� and tens of thousands of white troops came to Egypt and lived in segregated conditions.

The war had brought the global color line���long recognized by African Americans like W.E.B. Du Bois���into the backyard of Egyptian nationalists. But rather than develop this insight into solidarity, as Du Bois did in his June 1919 article on the pan-Africanist dimensions of the Egyptian revolution for NAACP journal The Crisis, Egyptian nationalists criticized the British for a perceived mis-racialization of Egyptians as ���men of color.���

Pharaonism, a mode of national identification linking people living in Egypt today with the ancient pharaohs, emerged in this context as a kind of alternative to British efforts at racializing Egyptians as people of color. Focusing on rural Egyptians as a kind of pure, untouched group that could be studied anthropologically to glean information about an essential kind of ���Egyptianness,��� Pharaonism positioned rural-to-urban migrants in the professional middle classes as ���real Egyptians��� who were biological heirs to an ancient civilization, superior to Black Africans and not deserving of political subordination to white supremacy.

Understanding Pharaonism as a type of racial nationalism may help explain recent controversies that have erupted in Egypt over efforts by African Americans to appropriate pharaonic symbols and discourse in their own political movements. This is visible in minor social media controversies, such as when Beyonc�� was called out for ���cultural appropriation��� for twerking on stage in a costume depicting the Egyptian queen Nefertiti. But sometimes, social media can spill over into more mainstream forms of Egyptian culture, such as when the conversation around the racist #StopAfrocentricConference hashtag���an online campaign to cancel ���One Africa: Returning to the Source,��� a conference organized by African Americans in Aswan, Egypt���received coverage on the popular TV channel CBC. While these moral panics pale in comparison to American efforts to eradicate critical race theory, for example, they still point to a significant undercurrent animating Egyptian political and social life.

The body in flight

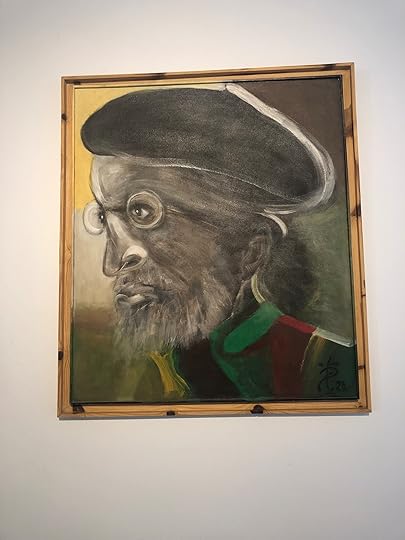

Installation view of "Now/Naaw" at Selebe Yoon. Photo credit Serubiri Moses ��.

Installation view of "Now/Naaw" at Selebe Yoon. Photo credit Serubiri Moses ��. Inspired by a play on the Wolof word meaning ���to fly,��� the exhibition Now/Naaw features the work of important Senegalese artist El Hadji Sy (born 1954). The exhibition, currently installed at Selebe Yoon, a gallery in the Plateau, Dakar, is organized in the context of the Biennale de l���Art Africain Contemporaine de Dakar. In its 14th edition, the Biennale���known simply as Dakar Biennale, or Dak���Art���opened on May 19th of this year. Led by scholar Dr. El Hadji Malick Ndiaye and funded by the government of President Macky Sall, this year���s edition has been long-anticipated, given that the recurring event last took place in 2018 before the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Ndiaye���s exhibition framework focused on the importance of African epistemologies as an energizing force following the pandemic���s spiritual and economic toll on a planetary scale. Curated by Jennifer Houdrouge, director of the Selebe Yoon gallery and residency space, Now/Naaw was championed as the first significant exhibition of the artist���s work in Dakar in decades. It included at least 30 artworks, including many recent works installed on wheels in the style of ���moving artworks.���

Some of El Hadji Sy���s accomplishments include his membership���starting in 1974���in the Senegalese art collective, Laboratoire Agit���Art, which was founded by famous filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambety and artist and philosopher Issa Samb. This group was considered a crucial site of intellectual opposition to former Senegalese president L��opold S��dar Senghor and to the national art school, ��cole de Dakar, led by Pierre Lods. Sy also initiated and administered the Village des Arts de Dakar, an important hub for Senegalese artists beginning in 1977. Sy���s other contributions include his curatorial contributions to the 1995 landmark exhibition Seven Stories of Modern Art in Africa at the WhiteChapel Gallery in London. In 1999, Sy received the National Order of the Lion, Senegal���s highest honor, from then-President Abdou Diof. He has had several solo retrospective exhibitions in Europe, but the Selebe Yoon exhibition is his first in Africa.

Installation view of “Now/Naaw” at Selebe Yoon. Photo credit Serubiri Moses ��.