Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 98

June 7, 2022

Milking the dream

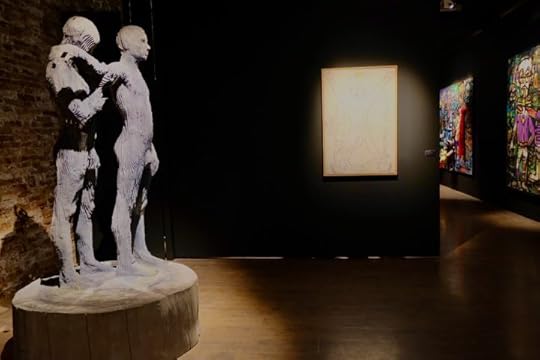

C��te d'Ivoire pavilion installation with Aron Demetz, Fr��d��ric Bruly Bouabre, and Yeanzi. Photo by author ��.

C��te d'Ivoire pavilion installation with Aron Demetz, Fr��d��ric Bruly Bouabre, and Yeanzi. Photo by author ��. The last time I attended the Venice Biennale was in 2015, when Nigerian-born curator Okwui Enwezor included an Isaac Julien-directed oratorio of Marx���s Das Kapital. Meanwhile, at the opening of the Biennale, Julien was thrown a party by Rolls Royce. Enwezor displayed these kinds of ironies. His Biennale artworks tended to flatten everything into politics, but for African artists, it was a crucial move that shifted the meaning of modern and contemporary African art away from performing its indigeneity to demonstrating that it precipitated decolonization.

This year���s surrealist theme, ���The Milk of Dreams,��� engages the obverse of political modernism. The chosen artists explore the mutations and illogic of a world engulfed in a pandemic, rapid climate change, and multiple scenes of hyper-mediated violence. There are more women artists featured in this year���s exhibition than ever before, and much of the art concerns women. One of five ���time capsule��� rooms is filled with the work of women and non-European surrealist artists, including rare pieces by Congolese artist Antoinette Lubaki: two untitled works that were collected by a Belgian collector in the 1930s, the height of colonial-era art by ���na��ve��� artists. The label assures viewers that ���these works show a sensibility unparalleled in the world of modern art������really, a recapitulation of primitivism. However, the global surrealism of the exhibition seeks to critique while allowing for the emergent and the grotesque. When indigeneity is performed, it is as an alternative to extractive capitalism. Head curator Cecilia Alemani���s three broad themes of the Biennale are ���the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses; the relationship between individuals and technologies; the connection between bodies and the Earth.���

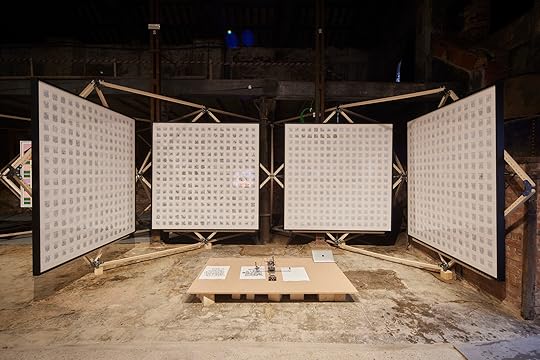

AFROSCOPE, A��she: Sunsum Kasa (2021 / 2022). Multimedia Installation. Digital collage. NFT Components: 1,024 ink drawings on 8.4 x 8.4 cm, sheets of paper, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Minted Artworks. Photo courtesy of artist ��.

AFROSCOPE, A��she: Sunsum Kasa (2021 / 2022). Multimedia Installation. Digital collage. NFT Components: 1,024 ink drawings on 8.4 x 8.4 cm, sheets of paper, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Minted Artworks. Photo courtesy of artist ��.For the main exhibition, Alemani chose twelve African artists out of 213: Igshaan Adams, currently in a solo show at the Art Institute of Chicago; veteran painter Ibrahim El-Salahi; Kudzanai-Violet Hwami; Bronwyn Katz; Antoinette Lubaki; historical Egyptian painter Amy Nimr; ceramicist Magdalene Odundo; Elias Sime���s massive wall panels with reused computer circuits; and Zimbabwean Portia Zvavahera���s meditations on Pentecostal spiritualism. Pavilions from the continent represented Uganda, Cameroon, Egypt, C��te d���Ivoire, South Africa, Ghana, Namibia, and Kenya.

The artists included in these African pavilions negotiate wildly different levels of access to materials and representation as they explore notions of personhood pressed to the edges of existence. Engagements with technology sit awkwardly next to a preponderance of painting and the handwrought, as in South Africa���s pavilion, where Phumulani Ntuli pairs augmented reality via tablet computers with his acrylic canvas, ���Swaying Through the Portholes��� (2021). Ghana���s pavilion (its second after 2019) presents a range of statements on ���Africa��� by curator Nana Oforiatta-Ayim, whose appointment and choices were subject to some grumbling by veteran Ghanaian artist Rikki Wemega-Kwaku. The pavilion includes artist Afroscope���s automatic drawings made with a computer program that is installed along with the work, as well as Na Chainkua Reindorf���s paintings that feature women in masquerade. All of the work is mounted on a latticework bamboo structure by D.K. Osseo-Asare; the result is a sustainable and tactical design. The exhibition celebrates unknown and young artists.

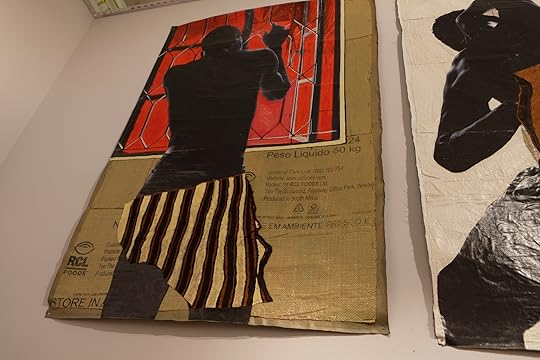

Installation detail of Collin Sekajugo, Red Sky (2021). Photo by author ��.

Installation detail of Collin Sekajugo, Red Sky (2021). Photo by author ��.The problem of access for artists in Africa is nowhere more obvious than in the Cameroon pavilion, which is, oddly, staged in two locations. One exhibits the Cameroonian artists, while the other features art by Global Crypto Art Collective DAO, which funded the Cameroon pavilion. Not one Cameroonian artist has participated in the NFT portion. Cocurator Sandro Orlandi Stagl seems to have simply used Cameroon���s pavilion to mount what all of the art world press have declared the ���first NFT exhibition at the Venice Biennale.��� (Stagl was previously the curator of the infamous 2015 Kenya pavilion at the Venice Biennale.)

There are too many of these games to enumerate here, but suffice to say that the Venice Biennale can be like the Olympics in its usurpation of national pavilions by the private sector. The ���real��� Cameroon installation features Ang��le Etoundi Essamba���s ���A-FIL-IATIONS��� (2022), a series of lush, large-scale photos of women in various poses with brightly colored thread draped onto their bodies. These and other excellent works (including a Black ���Salvator Mundi��� by Spanish artist Jorge Pombo) are installed in the courtyard of an arts high school. Works by Salifou Lindou and Afran highlight, respectively, the corruption that causes gross inequality and the addictive and destructive effects of social media.

In the C��te d���Ivoire pavilion, an installation with dramatic lighting and an architectural focal point is used to feature an Italian artist, Aron Demetz, somewhat obscuring the intricate work of Saint-Etienne Yeanzy. Still, a good pairing in the pavilion is Demetz���s homoerotic nude male sculptural pair alongside veteran Ivoirian artist Fr��d��ric Bruly Bouabre���s large drawing of a figure with an impossibly long phallus.

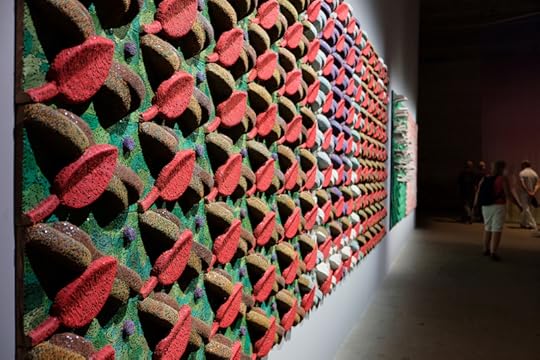

Installation detail of Elias Sime, Red Leaves (2021). Photo by author ��.

Installation detail of Elias Sime, Red Leaves (2021). Photo by author ��.Collin Sekajugo���s paintings in the Uganda pavilion are a powerful response to continued financial pressures and persistent representational stereotypes. ���Stock Image 017-I Own Everything��� (2019/22) and other works speak to the proliferation of artwork that features a Black figure in front of a patterned background, a style made famous by Kehinde Wiley but originating with 1990 Biennale favorite Seydou Ke��ta. Sekajugo���s works are paired with sculptures made from Acaye Kerunan���s social practice of weaving with groups of Ugandan women. They sourced palm and raffia from wetlands as a form of care for the environment; the piece is hyper-local and centers women���s work. Happily, Uganda won a Special Mention award.

The Venice Biennale represents a collection of enormous investments in art infrastructure. This year���s installations make clear that despite the lack of investment from African nations or the occasional hijacking by mercenary curators, African artists are finding ways to be seen. In this town born of globalism and mercantilism, the work nudges its audience to notice their contortions.

June 6, 2022

Where, and why, is North Africa?

Men playing at the porch of a mosque in Rissani, South-East Morocco. Image credit Ralf Steinberger via Flickr CC BY 2.0

Men playing at the porch of a mosque in Rissani, South-East Morocco. Image credit Ralf Steinberger via Flickr CC BY 2.0 How the Middle East as a region came to be, and why it matters, is very much on my mind these days: the centrality of race, the legacies of colonialism, the articulation of political projects around transnational identities, the role of the social sciences in producing and reproducing conceptions of regions. My recent piece in Foreign Affairs (���The End of the Middle East���), for example, questioned the geographical, political, and analytical usages of the conventional map of the Middle East as a region. That article built upon a huge 2020 project interrogating transregionalism which I developed with Hisham Aidi and Zachariah Mampilly and which primarily focused on North Africa���s place between Africa and the Middle East. That project continued in last year���s Racial Formations collaboration, which continued to explore these themes of transregional comparative research across Africa and the Middle East. If all goes well, I���ll be finishing a book on the subject in the next year.

Those questions and themes brought me to two books from outside political science which explore these issues in really provocative ways. Abdelmajid Hannoum���s The Invention of the Maghreb is a tour de force of historical scholarship, showing how French colonialism produced the idea of the Maghreb (North Africa) through deeply racialized repertoires of mapping, ethnography, and standardization. Megan Brown���s The Seventh Member State looks at Algeria as part of the negotiations over the European Economic Community. Each of these new books pushes us to rethink our understandings of what regions like ���Europe��� and ���North Africa��� really mean���and how deeply racialized their production really was.

The Invention of the Maghreb is one of the most interesting books I���ve read in the past few years, with a theoretically grounded and empirically rich historical narrative which constantly challenges assumptions and raises new questions. Hannoum traces how the concept of the Maghreb came to be defined as fundamentally and essentially different from the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. Much of this had to do with colonial competition. The French Maghreb had to be essentially different from a British-dominated Middle East, hence the exclusion of Egypt, as well as Italian-colonized Libya. Across his chapters, Hannoum shows how French cartographers and ethnographers worked to demonstrate that the differences between the Maghreb and Egypt were so deep that even the Sahara Desert had different physical qualities in the two regions.

Hannoum centers racial formations in how the French distinguished the Maghreb from the rest of West Africa. Africa, by this racialized logic, was defined by blackness; lighter-skinned North Africans, particularly Amazigh and Arabs, were viewed as something closer to, if not quite equal with, white Europe. The evidence he marshals across these chapters of the fundamental racism in French practice is overwhelming. One of the critically interesting lines he traces across French practice is the ethnographic creation of the Berber as ���a new category of the colonial discourse��� set in total opposition against ���the Arabs��� as well as black Africans, wiping out previous ethnographies revealing the diversity of peoples and cultures.

Hannoum traces the creation and naturalization of the concept of the Maghreb from 1830 (the year of Algeria���s conquest) to the 1960s. He engages, of course, with earlier definitions by Ibn Khaldun, the Ottoman Empire, and others, but maintains that there is something fundamentally different about how France created and shaped the region through distinctive colonial technologies and ways of thinking.

France did all this in the interest of governmentability, with imperial control requiring the shaping of culture, identity, and practice. In line with work by Timothy Mitchell on Egypt, Hannoum focuses on ���the operation of colonial technologies of power.��� (The fact that Hannoum barely engages with Mitchell only illustrates the divides between North Africa and Middle East studies.) Colonial institutions depended not only on brute force, but on the production of knowledge and categorization which rendered societies legible and governable. His book goes into great detail on the contributions of the various social and physical sciences to this project���anthropology, historiography, geography, linguistics, statistics, biology, zoology���all part of the imposition of a colonial modernity rationalizing colonized societies along European terms.

Hannoum pays particular attention to mapping as a technology of power: colonial ���violence relied on cartographic knowledge and in turn produced a subdued land to be mapped ���correctly.������ He shows the evolution of the presentation of the Maghreb in these maps: when Algeria is separated from Mali, then from Morocco; when Libya is included and excluded. But ultimately, the defining line is race: ���the Maghreb has a geographical limit, the sands, and a racial limit, blackness.��� The Sahara���in rather sharp contrast to its actual lived reality���is presented as a ���buffer��� between black West Africa and the white Maghreb. The legacies of those racial formations continue to shape North African politics to the present day, as essays by Afifa Ltifi, Hisham Aidi, Steven King, Paul Silverstein, and Eric Hahonou in our Racial Formations collection demonstrate.

Where Hannoum shows us how the Maghreb came to be differentiated from West Africa and Egypt, Megan Brown���s new book shows another dimension of differentiation, this time from Europe. It seems obvious that Algeria would be part of the negotiations over the 1957 Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community (EEC). After all, in 1957, Algeria was still very much a part of France, despite the escalating war of independence. But its participation hasn���t really been a major part of the historiography or political science of the EEC. Nor, as Megan Brown shows in her fascinating new book, The Seventh Member State, was what this actually meant for the meaning of Europe ever entirely clear.

There is, of course, a vast literature on Algeria���s war of independence and its 1962 separation from France���Todd Shepard���s The Invention of Decolonization stands out for me on the French side, and Jeffrey James Byrne���s Mecca of Revolution on the Algerian side. And there���s also, of course, a vast literature on the negotiations over the formation of the European Economic Community; I haven���t kept up with that literature lately, but back when I taught courses on comparative regionalism, Andrew Moravcsik���s The Choice for Europe was my go-to text. I don���t remember thinking about Algeria much when reading about European regional integration.

The two literatures, on decolonization and regional integration, seemed to run on parallel tracks. Brown expertly weaves together the two timelines, showing how deeply interwoven the course of Algeria���s war for national independence was with the course of the creation of the European Economic Community. She ���calls for a new reading of the spatial boundaries of integrated Europe��� through a detailed reconstruction of the negotiations, agreements, and administrative decisions made by European bureaucrats. Algeria was included by name in the 1957 Treaty of Rome, and European regulations extended to Algeria for five years, until Algeria���s independence. Even after that, the EEC was uncertain about how to deal with Algeria. The idea of Algeria as the ���seventh member state��� struck Europeans as absurd���despite the fact that for half a decade, it had in fact been included.

Algeria���s status within the European Community stood against a broader European debate over ���Eurafrica��� (the subject of a full chapter in Brown���s book). Four of the six European states negotiating the Treaty of Rome had imperial interests at the time (and Britain���s empire weighed heavily on French opposition to its inclusion), but Algeria���s status as constitutionally part of France set it apart from the rest of its own empire���or any other imperial possessions held by its European counterparts. Brown shows how France fought for Algerian inclusion in the EEC, both for economic reasons and as an alternative forum to demonstrate Algeria���s Frenchness as the Algerian National Liberation Front���s diplomacy made inroads at the United Nations. But as Algeria moved towards independence, French interests changed. As Europe contemplated what to do with independent Algeria, race again weighed heavily in rendering its inclusion ���obviously��� absurd. As Brown puts it, ���European officials not only wrote Algeria out of the EEC, its history as a part of its foundational territory was erased from memory.���

I���m fascinated both by the fluidity of regional identity in the early periods described by both Hannoum and Brown, and by the naturalization of those identities over time. Race, obviously, plays an enormous role in fixing these regional boundaries. So too does colonialism and, later, great power politics, as well as highly local political dynamics. What���s especially interesting is the role played by the social sciences in producing and reproducing these naturalized conceptions of region. That���s been the subject of a great amount of important research in recent decades, obviously not only in Middle East-focused literature. It helps us to think through how our own work as political scientists either reproduces or challenges those modes of power today.

Colonial vice at the Venice Biennale

Photo by Peinge Nakale on Unsplash

Photo by Peinge Nakale on Unsplash The 59th edition of La Biennale di Venezia (Venice Biennale), which opened in April and runs to November, added five new national pavilions to its exhibition roster���Cameroon, Namibia, Nepal, the Sultanate of Oman and Uganda. At least two of them have already generated controversy in the media. The Biennale appears intent on deferring to the models that increasingly bind the art world to the world of business, and controversy surrounding two African pavilions make this very clear. They invite us to interrogate how the increasing interest in African art may be linked to the power dynamics that define the global international market.

A group of Namibian artists petitioned the Namibian government (through a campaign aptly titled ���Not Our Namibian Pavilion���) to withdraw its support for the national pavilion, an effort that met with some success.The pavilion opened, but not without scandal that led the show���s main sponsor, luxury travel company Abercrombie and Kent, to pull out, along with patron Monica Cembrola, an Italian art collector with a special interest in African art. The artists��� request that the pavilion be presented as a personal project of Marco Furio Ferrario, the curator, rather than a Namibian national exhibition was ignored. The Namibian artists denounced a ���poor and inadequate debut, with an old-fashioned and problematic view of Namibia and Namibian art��� linked to the impromptu curatorship, and to sponsors whose interests were clearly linked to the interest of tourism, rather than the country���s cultural and art sector. Despite the country���s flag being prominently displayed at the entrance to the pavilion, the Namibian government���s position remains unclear.

The Namibian pavilion features the ���land art project��� titled ���The Lone Stone Men of the Desert.��� It is credited to an anonymous artist known only as RENN. It consists of a series of stone and iron sculptures representing human forms that appeared a few years ago in the Kunene desert in Namibia. There are many debates in the art world about anonymity and authorship. Collective authorship, for example, is what defines most of the works of Brazilian contemporary Indigenous artists, whose names often refer to a collective people. But as the Namibian petition states, ���RENN, the artist, is publicly known in Namibia as a member of the tourism industry. His identity is now semi-public: a 64-year-old white Namibian man, born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and largely disconnected from contemporary art and the country���s cultural scene. He has never exhibited in personal or collective exhibitions, national or international.��� Nor does his name or work appear on the internet, apart from at the Venice Biennale. It is therefore surprising that RENN was chosen to debut work at a national pavilion at one of the most prestigious art events on the global calendar.

The same can be said for the curator. According to his website Marco Furio Ferrario is a ���Strategic Consultant��� with a specific focus on business growth. An author and curator, born in Milan in 1984, he completed his Master’s degree in 2011with a thesis on logical-mathematical and rational decision-making processes in stressful situations. Not to discredit his multidisciplinary profile, but at least minimal experience in the art and culture sector would seem appropriate to curate such a prestigious exhibit. Instead, Ferrario���s experience in Namibia concerns management and business innovation in the tourism sector, particularly in the nature reserves, Elephant Lodge and River Camp, which his website defines as ���two of the most exclusive lodges in Namibia,��� and part of Okahirongo Lodge, one of the pavilion���s sponsors. Coincidentally, the activities offered at the lodge���ranging from desert adventures to ���immersion in the heart of Kaokoland and the extraordinary Himba culture,������are similar to those offered by the art project curated by Ferrario.

If nothing can be found on the internet about Ferrario���s artistic credentials, the connection with the land which the project is interested in is very clear. As defined in the curatorial text: ���The chosen setting is such that only two types of observers can find the works of art: the Himba tribes (which are one of the few tribes that still live in a pre-technological state�� and the few lucky and courageous travellers who venture to discover the desert (who mostly belong to social groups opposed to the Himba, with highly technological and urbanized lifestyles��� (read: tourists who frequent the Namibian resorts that Ferrario intends to promote).

According to the petition, this project ���is highly problematic as it is imbued with the historically racist premise that Indigenous peoples are perceived as closer to nature than to humans. This was used to justify the oppression of Indigenous peoples, labeling them as naive and subhuman.���

If the curatorial text presents ���the relationship between human cultures and nature��� as central, the same text explains the absence of any consideration of contemporary debates about the regimes of power that affect the production of knowledge and art. Moreover, the ways in which the West continues to look at the world and ���the other,��� the maintenance of the prejudiced and colonial dichotomy of the uncivilized versus civilized, as well as clear use of culture and art for economic strategies. The ���brave travelers���are given to exploit the wild inhabitants of the desert, just as the curators and sponsors are given to manipulate the culture of the others to propagate their own businesses, and those of local elites. As the petition states: ���this is the same ideological basis that supported colonial expansion and the occupation of territories such as Namibia and the exploitation of its people and natural resources.���

Meanwhile both the curator and the patron issued statements in defense. Ferrario, the curator, explained he ���…saw RENN���s artworks in the Namibian desert and fell in love with them��� adding that he had begun to think about how to show them internationally during the pandemic, and knew the Biennale would afford the biggest global stage. Pressed about the fact that RENN���s has no background in the arts sector, Ferrario argued, ���I did not choose an artist, I chose artworks. The point of this exhibition is that art comes before the artist.��� In personal communication, Cembrola noted that she wasn���t told about the identity of the artist. The petition clearly indicated that the artist was not representing Namibia and because her aim is to ���help emerging artists from Africa,��� she decided to withdraw.

Despite having no background or record in the art field, Ferrario has the means to put RENN���s work on the global stage in Venice. The patron, affected by a rather common Western spirit of salvation, wants to ���help emerging artists from Africa��� (and according to her website loves African art), yet has no clue about the artist she is going to invest not only her money but also her credibility as an emerging African art collector and patron. People involved in the art scene in Namibia that I interviewed confirmed that the pavilion cost about USD100,000���a significant amount of money for a pavilion that features 30 colored pictures in ordinary wooden frames, four pairs of binoculars (the artistic contribution of a duo of white, female Milanese designers, and added to the original plan after the complaint about a solo artist) and five statues. Cembrola brought Abercrombie and Kent on board as the main sponsor. In a press release, Ferrario states that most of the people involved in the production of the pavilion worked for free, while Cebriola, in a personal communication affirmed the pavilion looks like it used 10% of the resources available for the installation.

Although Abercrombie and Kent pulled its support, it is worth noting that it is a multinational luxury travel company, founded by a white man who claims to be ���born on safari and raised on his family farm in Kenya,��� recalling the worst aspects of Karen Blixen���s Out of Africa. The smaller sponsors, Onguma Safari Camps, Chiwani Cam, the aforementioned Okahirongo Lodge, the Windhoek Country Club Resort, the Gondwana Collection, are all luxury hotels and continue to support the project. Namibia Media Holdings (NMH), responsible for the pavilion���s communication, is also a platform that supports the tourism sector. In this context, the Biennale looks more like a luxury safari tourism fair than ���a meeting point between people in art and culture.���

No less concerning is the pavilion of Cameroon, making its debut and, at the same time, conceiving its market with Non-Fungible Token (NFT) Art. An NFT can be any type of digital file: a work of art, an article, a song. You can own it, but you cannot touch it. In order to sell their works and maintain ���certified ownership��� of them, NFT artists must mint them in a cryptocurrency, such as Blockchain, through a digital transaction that refers to who generated it, thus creating an immutable trace of origin. If one of the three thematic areas of this edition of the Biennale concerns the relationship between individuals and technologies, there are conflicting opinions about digital art in the context of the NFT, and its presence in Venice will definitely reinforce its legitimacy.

Titled ���The Times of Chimera,��� the Cameroon pavilion, curated by Paul Emmanuel Loga Mahop and Sandro Orlandi Stagl, will occupy two locations: the Michelangelo Guggenheim State School of Art and Palazzo Ca��� Bernardo. The first will receive four Cameroonian artists (Francis Nathan Abiamba, Ang��le Etoundi Essamba, Justine Gaga and Salifou Lindou) and four international artists (Shay Frisch, Umberto Mariani, Matteo Mezzadri, Jorge R. Pombo). The second NFT exhibition will have 20 artists from various countries���mainly Argentina, China, Spain, Italy, and Germany, only one from Cameroon. Stagl is known for curating the controversial Kenya pavilions in the 2013 and 2015 editions of the Venice Biennale. As reported by Lorena Mu��oz-Alonso, Kenya debuted at the 2013 Biennale with a group show of 12 participating artists, only two from Kenya: Kivuthi Mbuno and Chrispus Wangombe Wachira. Even worse, in 2015, the pavilion, curated by the same team, featured only one Kenyan artist, Yvonne Apiyo Braendle-Amolo.

The Cameroon pavilion seems to repeat the same vice: preferencing artists from other countries to those from the host country. Among 28 invited artists, only four are from Cameroon: Francis Nathan Abiamba, also known simply as Afran, who was born in Cameroon, studied contemporary art at the Academia de Carrara, Bergamo and currently lives in Italy; Ang��le Etoundi Essamba a Cameroonian photographer who studied in France and is a graduate of the Photo Academy of Amsterdam, where she currently lives; Justine Gaga, a sculptor and video artist based in Bonendale, Cameroon, who collaborated for many years with Goddy Leye at ArtBakery, an initiative that promotes the development of contemporary art and practice, with a special focus on multimedia art in Cameroon and Central Africa; and Salifou Lindou, a self-taught artist who lives in Douala and works in painting, sculpture and video. In 1988 Lindou participated at the Dak���Art Biennale and in the same year he co-founded the design collective Kapsiki Circle with fellow Cameroonian artists Blaise Bang, Herv�� Yamguen, Herv�� Youmbi and Jules Wokam.

Commissioned by Armand Abanda Maye, the director of arts promotion and development at the Cameroon Ministry of Arts and Culture, the pavilion has no government funding. The project is instead supported by private sponsors and investors from the Global Crypto Art-Decentralized Autonomous Organization (GCA-DAO), a collective initiative that is on the rise on the so-called ���Web3������ an internet-based infrastructure that uses blockchains. The GCA-DAO was formed in December 2021 by five founders from the NFT community, 15 contemporary art and crypto-art professionals, and 22 traditional artists. It is responsible for the selection of the artists in the NFT exhibition in C�� Bernardo. Artists do not pay to participate, but a donation of one or two works is ���suggested.���

Shortly before the start of the Biennale, GCA-DAO sold tradeable passes on its website at 2.8ETH (about USD8700). Passholders are afforded the status of ���councilors��� of the organization, VIP previews to the exhibition, and other exclusive perks. During the course of the Biennale works are not sold outside the exhibition, but potential investors and collectors are encouraged to buy and collect them before and after. Artists are also free to market their work. Global Crypto Art-DAO plans to continue its ���curatorial��� work in the future.

The provenance of the works and the intention of this NFT exhibition becomes more questionable when it is noted, for instance, that the artworks of the selected Brazilian artist, Jo��o Angelini, were minted by the gallery that represents him and not by the artist himself. Web 3 is made up of ���user-generated content, with user-generated authority,��� in this case the artist���s. The best practice in this field would require that an artwork by a living artist, such as Angelini, has to be created by the artist and not through a reproduction, even if agreed, by the gallery.

Global Crypto Art-DAO is explicitly monetizing the exhibit even before it happens��� selling tradeable subscriptions in Ether, the second-largest cryptocurrency, almost passing it off as a performance���with the endorsement of the institution. Announcing something that is part of the Biennale with a price list is a bit obscene and contrary to the overall goal of such an event, which is not an art trade fair. The Namibian pavilion example is instructive: RENN���s artworks are on sale for around USD16,000, and unique sculptures at just over USD50,000, as part of the pavilion���s ���fundraising goals and packages.��� It is highly unlikely that the Biennale���s organizers and their legal team are unaware of these economic practices that go beyond cultural extractivism, and raise serious ethical and professional questions.

In the Namibian case the association between the economic interests linked to the curator���s previous activities and the tourism economic sector are clear and need to be considered in relation to Indigenous land ownership. Amartyuan Sen, mentioned in ��nde Somby���s presentation ���When a Predator Culture meets a Prey Culture,��� states that one of the characteristics of humanity is that the stronger have an obligation towards the weaker. Somby makes a simple but effective example. He shows that as in the animal kingdom big fish can eat small fish. In humanity there must be something to protect the smaller fish, and ���sometimes this is morality, sometimes the rule of law.��� It is evident that in spheres where the rule of law is of little concern, even morality is missed.

As the Namibian artists responsible for the petition well describe: ���A group of Italians with no relevant curatorial experience���not to mention significant involvement with Namibian art���took on the task of ���representing��� Namibia in Venice [���] [people] alien to sensibilities related to decolonial and intersectional issues, especially in a particularly complex post-apartheid era in which efforts to correct past injustices are essential to addressing a project of this nature���. The lack of sensibilities related to decolonial and intersectional issues clearly emerges also in the case of the Cameroon pavilion and its curator, whose fame is linked mainly to the shameful events of the Kenyan pavilion in 2013 and 2015. After seven years we move to another country but the actors and the scenario are the same.

The myth of the prestige and validity of the work of art, implicitly linked to participation in the historic Venice Biennale, seems to be in decline. Or, at the very least, increasingly reduced to a logo that can be used in post-Venice portfolios.

June 4, 2022

The political economy of “decolonization”

Image credit Ting Chen via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

Image credit Ting Chen via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0 Kenya has a rich history of decolonial struggles, but the conservative mainstream political vernacular prevents more engaged praxes for decoloniality in both public and private spaces. When it comes to academia, Njoya argues that “anti-colonial resistance” is more “reputation than reality,” and this is a situation that has detrimental effects on both students and the academics trying to push these important conversations. The following article is a part of our series of reposts from The Elephant. It is curated by editorial board member Wangui Kimari.

Over a decade ago, I was a fresh graduate, still aflame with post-colonial critiques of empire and eager to implement this consciousness in my new station back home in Kenya. In one of my first assignments as a na��ve and enthusiastic administrator, I attended a workshop on implementing the Bologna Process in higher education.

For me, the workshop was odd. We were implementing an openly European framework in Kenya, a country which gained fame for challenging cultural colonialism, thanks to people like Ngugi wa Thiong���o���s and his classic��Decolonising the mind. It was surprising to me that this workshop would happen in a country where it has now become standard practice in Kenyan literature to present the great art of our ancestors as a evidence disproving the claims of colonialism. Our students cannot read an African work of art without lamenting the colonial experience. Surely, implementing a European education agenda in 21st century Kenya should raise some hullabaloo. But this Europeanization of our education seemed to raise no eyebrows.

Eventually, I could no longer ignore this elephant in the room. So I asked: why are we implementing a process without discussing where it came from and what problem it was addressing in its context?

I have now learned that such questions are not to be asked in Kenyan universities, which is the point I will emphasize later. For the moment, I will repeat the answer I was given: if the Bologna Process improved higher education in Europe, it will do the same for us in Kenya.

At that time, I was too academically shy to interrogate that answer. It did not occur to me to research whether it is true that the Bologna process delivered the spectacular results in Europe that we were being promised, or even to find out the reactions of European faculty and students to the process. In retrospect, I now understand why I could not interrogate that answer.

To be a young academic in Kenya gives you a fairly strong inferiority complex. Rather than acquire humility of knowing that there is so much to learn, you acquire a shame of knowing. Worse, you fear asking questions because the answer you get sometimes suggests that you are arrogant, which is usually expressed as an accusation that you think only you have a PhD. So I accepted the answer I got.

Imagine my surprise to later discover that there was a political economy around the Bologna Process. The short version of it is that the Bologna Process was an effort by the European Union to��fight back against the US and UK��efforts to monopolize the higher education ���market��� with Ivy League and Oxbridge universities. Bologna Process was continental Europe���s way of commercializing itself at home, and in Africa, setting European universities as the standards against which African universities benchmarked themselves.

Within continental Europe, students demonstrated against this standardization at protests called ���Bologna burns.��� Faculty pointed at the neoliberal and corporate agenda of the Bologna Process. In African continental platforms like CODESRIA, African scholars raised questions about the political motives of the Bologna Process and pointed out that African universities would complacently implement the process largely because Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) had rendered universities vulnerable to external interference.

But in Kenya, land of��Decolonizing the Mind? We academics quietly implemented it without raising questions.

Anti-colonial resistance in the Kenyan academy is more about reputation than about reality. The Kenyan academy is�� conservative as a whole, despite its rhetoric of opposing colonialism and affirming African culture. It appears that the global resonance of the Mau Mau and the persecution of faculty and students by successive Kenya governments have made the world see more anti-colonial resistance in the Kenyan academy than exists in reality. As a result, the Kenyan academy remains stuck in a gap between the rhetoric of decolonizing on one hand, and on the other, the reality of coloniality and of the university as an agent of coloniality.

Even I, a Kenyan, was still mesmerized by our anti-colonial reputation when I naively asked why we were implementing the Bologna Process. It is only after ten years of never getting direct answers to my questions about the Kenyan obsession with global ���standards,��� ���competitiveness��� and benchmarking,��� that I slowly accepted that there is a fundamental dissonance in the Kenyan scholarly consciousness.

This reality, in a nutshell, is why the current discussions of decoloniality may not take root in the Kenyan academy.

That is not to say that the concept of decoloniality is irrelevant. My Bologna Process experience is proof that coloniality of power is very much entrenched in Kenya. Policy travel in education has made Kenyan education bureaucrats, many of whom are academics and professors, adopt and implement Euro-centric policies in Kenya���s schooling system. Meanwhile, the policy makers frown upon and run away from questions about the policies themselves.

This brutal reality has hit home for me with my public engagement on the competency based curriculum. The Ministry of Education policy makers have refused to answer questions on the imperial and commercial interests behind the competency curriculum. Worse, some of the supporting documentation they have filed in court cases, to which I have had access, openly demonstrate the racial bias of the foreign promoters of competency, especially in the United States.

As if that is not absurd enough, Kenyan scholars of education seem unperturbed by this overt imperial control of Kenyan schooling. A search on Google Scholar for Kenyan studies on CBC shows that few, if any, carry out an actual philosophical or political critique of the school system and of the international actors behind it. More absurd, the concern of some of the scholars is with the indigenous content in what is basically a recolonizing curriculum.

The insights from decoloniality studies cannot be more urgent in Kenya. Decoloniality would help us distinguish between maintaining an anti-colonial rhetoric and reinforcing colonial logics of power. It would enable us to understand that even�� African cultures can be weaponized for colonial agendas. It would help us detect and explain the inertia and decline of Kenyan universities.

But here���s why it will be difficult for decoloniality discourse to take root in Kenya.

As an approach, discussion of decoloniality requires certain institutional conditions. One is our ability to be political. To be political, as Lewis Gordon says in several of his works, is to go beyond oneself. One must be willing to ask about implications for people beyond the self, for time beyond the present, for space beyond the here. Second, one must have a fairly robust knowledge of national and international history. Third, one must be willing to accept their own implication in the colonial project.

All these conditions do not exist in Kenya. Kenya is a very��conservative country, in the political sense of the word. By its very essence, conservativism denies the political. Conservativism explicitly discourages discussions of power and sociality�� in institutional and daily conversation. The question I asked about why we were implementing a foreign education policy was a political one because it was a question beyond myself. It was a question about the institution, society and international community.

The only questions we Kenyans are allowed to ask are about the personal. We Kenyans are not allowed to think socially and globally. Hence one will often hear Kenyans silencing one another with responses such as ���speak for yourself,��� or ���that does not apply to everybody.��� Similarly, the answer I got was that the Bologna Process would work for me as an administrator faithfully implementing it, and maybe for the institution, but it remained silent on the larger society.

On the question of history, it goes without saying that Kenya does not teach its history, either in the syllabus or in popular arts. The competency curriculum, for example, has reduced history to citizenship, which means that there is an intention to limit Kenyan children���s knowledge of history to legitimizing the state. For the few Kenyans who escape the war against humanities by the Kenya government and private sector, and who specialize in the arts and humanities in the university, we are preoccupied with protecting our jobs as we are accused of teaching subjects which have ���no market.��� With such a weak public grasp of history, a decoloniality conversation in Kenyan academic circles becomes difficult.

The third issue, of personal implication of academics in the colonial project, is probably the most difficult to tackle. Because of the de-socializing and de-politicizing rhetoric of what Keguro Macharia calls��Kenya���s political vernacular, Kenyans find it psychologically difficult to deal with contradictions, and deflect them with the conservative moral rhetoric of blame. If one points out the colonial threads in a particular policy, a Kenyan academic will typically respond with statements such as ���let���s not blame one another,��� ���we need to be positive so that it works,��� or ���let���s not politicize issues,��� or ���let���s not take this personally.��� It is inevitable that the social and political conversation which decoloniality demands will be difficult for us when we operate in an atmosphere where cannot have conversations beyond the self and morality.

Decoloniality in Kenya may be permitted in Kenyan universities if the Kenya government receives a grant to promote it, or if the British Council or other foreign donor will sponsor a conference on it. And it will likely hover around the old, conservative slogan of ���let���s go back to our cultures��� which, as Terry Ranger wrote, was a slogan from the colonial government itself.

For the decoloniality discourse to take root in Kenya, we need to deepen our knowledge and teaching of history. We cannot have a conversation about history when we do not know it. We need to overtly confront the conservative Kenyan political vernacular. We must refuse the small space of blame that makes us constantly apologize for possibly treading on people���s feelings and sounding like we are assigning personal guilt. We must refuse to be policed by demands for verified facts and data as a condition for having a social conversation.

But that work is easier said than done. Kenyan academics who take this journey should know that challenging these discursive barriers will, most likely, come at an emotional and professional cost. We should not be surprised by accusations of being negative and confrontational, or by being isolated and lonely within our institutions. I know several Kenyan academics who are suffering painful psychic injuries after being isolated for daring to do this work. But we can survive and thrive if we deliberately search for solidarity among individual academics across the country and the world who are having that conversation.

June 2, 2022

A crop that changed the world

Photo by Tom Hermans on Unsplash

Photo by Tom Hermans on Unsplash In the last pages of her debut book, Slaves for Peanuts: A Story of Conquest, Liberation, and a Crop That Changed History (2022, New), journalist Jori Lewis breaks the fourth wall to bring readers into the present and share a story from her reporting process. The archives she had mined were rich with stories of a village called Kerbala���an outpost of French control on the westernmost coast of Africa which thrived at a time when France controlled all of what is now Senegal and much of West Africa. Kerbala had been a haven for freed slaves who had escaped bondage further inland in the 19th and early 20th centuries. But more than a century after its heyday, the village had very nearly disappeared into the landscape. Still, the journalist writes, she wanted to see whatever was left of it for herself, so she took a cab inland from her base in Senegal���s coastal capital of Dakar before riding a horse-drawn cart to a remote village. There, she met an old man who, she was told, might know where the village once stood. The mood was a bit desperate, and the author tempered her optimism: there was no reason to suspect that even the area���s oldest resident would remember the stories of people who ���weren���t warriors or princes or learned clerics.��� And in fact, after some careful thought, the man said he had no recollection of it. Instead, he said a prayer for the author: that Allah would help her find what she was searching for. Lewis thanked him in two languages, and then, she writes in the last words of the book, ���I continued along my way.��� It���s a fitting end to a story about a people who, beyond being forgotten, were scarcely remembered in the first place.

Slaves For Peanuts is a story about a crop and the people who grew it at the margins of an empire. The slaves in this case were not in the southeastern United States, but in West Africa���specifically, in the humid, inland pastures which, in the 1840s, were the most abundant source of the world���s most important oilseed. Like many (if not most) imperial forays of the day, the peanut���s importance came down to a coincidence of taste, industry, and geography: Europe needed oil���to cook and grease machines, but especially to manufacture soap with. Olive oil was well suited to the purpose, but olive trees were vulnerable to frost and tended to grow in areas prone to conflict, making the supply unreliable. Palm oil made perfectly good soap and was popular in England, but its yellow hue was unappealing to French consumers. In the 1840s, French industrialists turned to peanut oil���and soon realized it could be used in a variety of ways, from cooking to fueling lamps.

In France, many consumers���already accustomed to white olive oil bars���likely didn���t even notice they were buying something new when soap manufacturers switched to peanut oil. But in Africa, the shift was nothing short of transformational. At the start of the peanut boom, France���s presence in Africa was limited to a few outposts on the westernmost edge of the continent: ���more a hodgepodge of settlements than a cohesive colony, with an ever-rotating population of temporary agents for trading companies.��� The largest, on an island called Saint Louis at the juncture of the Senegal River and the Atlantic coast, was a gateway through which the region���s wealth passed on its way to Europe. The rest of Africa lay just beyond it: ���a whole continent���one where the French were guests, not hosts,��� as foreboding as it was vast, and where practices which were illegal in French territory���including slavery���were widespread. While the French occasionally played the role of white interlocutor, the Africans of the interior were content to keep them at arm���s length.

Peanuts changed all of that. After France banned slavery in all its colonies in 1848, French colonialists began to see themselves as being part of a ���civilizing������not just a mercantilist���cause in Africa. But rising demand for peanuts had spurred demand for farm labor���and thus for slaves. As the French followed their commercial interests ever deeper into the African countryside, freeing more and more people from bondage as they went, the contradiction between their dual missions became harder to ignore. ���The trading period has begun; it is said that there will be many peanuts this year,��� one commander reported to the local governor in the late 1870s, eyeing the inevitable shift towards French control. ���There is, however, one small dark cloud. It is the upcoming liberation of the slaves.���

The geopolitical game Lewis describes in Slaves for Peanuts is an old one, and one essential to the formation of the modern world: one side declares itself ���modern,��� ���civilized,��� or otherwise ���advanced������not just technologically, but morally as well���all the while depending on an influx of goods at a cost that���s only possible in the ���heathen,��� ���barbaric,��� or ���underdeveloped��� areas outside its control. As Lewis shows, division and denial allowed European soap buyers to stake a position of ethical supremacy without having to pay a great deal for the high standard of living they craved.

Readers will recognize parallel arrangements that make the comforts of our own world possible: think of how cheap agricultural goods like avocados (and workers) pass across the US-Mexican border, or how retailers in the US, Europe, Japan, and other countries source goods from China���where labor and environmental regulations are lacking���all while crowing about the ���green��� commitments they���ve made at home. For all of France���s proclamations of libert��, ��galit��, and fraternit��, slavery was essential to both the moral and material architecture of French imperialism in Africa. But legitimizing moral hypocrisy has always been essential to making capitalism work.

One thing that has changed is our perception of those travesties. Modern technology makes it possible for rich nations to exploit poorer ones from a distance, allowing a degree of psychological dissonance. But in the 19th century, exploiting Africa���s lands���and the human hands that worked them���still required maintaining a nearby territorial presence. At least a few proponents of France���s ���civilizing mission��� had to live in close contact with the people who suffered under it, making the hypocrisy of the whole thing all but impossible to deny.

Lewis sifted the details of 19th-century Senegal mostly from yellowed letters, account books, and dispatches from archives in six countries. That alone is an astonishing achievement. What is more remarkable is that she was able to depict not just the early colonizers, but the Africans as well, including a few former slaves who either fled for French domains like Saint Louis���and rose to prominence in the tumultuous atmosphere of the colonies���or started their own communities nearby, like Kerbala.

Nonetheless, most of Slaves for Peanuts is necessarily limited to the stories of people whose lives history managed to record���namely, the missionaries and inland power brokers who dealt and corresponded with the French regularly. At times, the plot can be hard to follow, as their priorities shift and new people cycle in from Europe. The slaves are a constant presence, but they typically exist in the background, recognizable as a collective more than as individuals.

Where the story becomes most vivid, however, is in Lewis���s descriptions of landscapes, which she often renders more clearly than the characters who populated them. One can see how areas separated by the hard lines of colonial decree were brought together by the bonds of human connection. ���Saint Louis prospered despite all the odds,��� she writes, introducing the emergent destination for the liberated. She goes on: ���It went from a sandy island with a small, fortified post to a proper city as traders and dealers imported stone from the Canary Islands to build houses, and people from the kingdoms up the river or across the dunes staked their tents or built houses of mud and reeds. Eventually, the city filled the whole island and had to expand. … Soon, bridges from island to island were built, to link the major points of the archipelago and provide for communication and commerce with the people up the river and across the dunes. Still, going to Saint Louis took fortitude and determination.���

Ultimately, depending on forced labor for such a basic commodity became untenable for a power that considered itself the vanguard of civilization in Africa. By the 1880s, after having indirectly encouraged slavery for decades, France (along with several other European powers of the day) declared an ambitious plan for conquering the rest of the continent and cited slavery���s persistence as a justification for it���marking the start of what the British called the ���Scramble for Africa.��� Hundreds of miles from the coast, at the groundbreaking for a new garrison in Bamako, Mali���one of the last stops of a future rail line which would connect West Africa���s interior to its coast and sustain French dominance in the region for generations���one French colonel told the crowd that slavery was ���an integral part��� of African morality, and one that Europeans alone had the responsibility to end. Having already spent hundreds of millions of francs attempting to abolish the practice, he said, ���Republican France can spend a few million to modify, little by little, with wisdom and prudence, the vicious, unproductive, immoral system which is so beloved of all these peoples.���

By then, whatever memory French colonialists retained of having encouraged that ���immoral system��� had already faded. In time, the memory of the slaves themselves would pass as well.

Stellenbosch University���s intractable racism problem

Stellenbosch. Image credit Kent Wang via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0.

Stellenbosch. Image credit Kent Wang via Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0. The case of a white law student at Stellenbosch University breaking into the room of a Black student and urinating on the latter���s possessions and objects is one more episode in an ongoing story of racism���s resilience in South African social life. Of course, Stellenbosch University has a peculiar recidivist streak when it comes to these kinds of incidents (as a former student at the university, Simone Cupido, capably elucidated in this article). Those of us Black academics���I am a faculty member in the English department���who are positioned in a relationship of proximity to the event must diagnose what it means to be Black at such an institution. Diagnosing this event gives meaning to the sense of being caught up in something ugly, by allowing us to assign it to a certain pattern and category of behavior.

We are by now familiar with the way a racist incident generates its own language of understanding; the inclination to think of it in terms like ���outbreak��� and ���larger issues.����� It rapidly becomes a scene in which we flail about for meaning. Racist incidents that happen in large institutions that have a strange, doubled life have seen, in the aftermath of this event, expressions of impatience proliferating on social media: ���What do you expect from Stellenbosch / Why are we surprised that this is happening at Stellenbosch/Stellenbosch has always������ etcetera. From the outside, this incident at Stellenbosch University is a self-evident case study of something that has always been there.

Internally, the gestures and statements tend to be ones of disavowal. Accompanying the anger at the actions of the individual student, one perceives a gathering sentiment along the lines of ���well, of course, racism happens everywhere … / well, obviously it is unacceptable and does not reflect our values …���; statements in which racism is an inconvenient disruption of the work we are all doing. The brusque tone of these renunciations has the consequence of making those of us who want to dig beneath the surface of the event feel as though we are part of the inconvenience because we want to ask what is being taken for granted, rather than rushing to formulate palliative answers that make the problem go away. Our departments and faculties rush to issue assurances of our bona fides, more for the sake of the students than for the academics, who are meant to take it for granted that the space they work in is not actually a harbor for racist ways of being in the world. This assumption of our own criticality is how academics shield themselves against having to examine their own implication in ���incidents��� like this. But if we understand ourselves as being implicated in what goes on within the institutions where we work, then we understand our proximity to the problem in a different way.

I have worked at Stellenbosch University for 13 years and seen the different ways in which the university sustains and generates harmful ways of engaging with the world among its white students. It is a campus where I have repeatedly had white students bump into me on the sidewalk, or obliviously almost run me over as I walk onto a pedestrian crossing, only to express confusion at my presence, since their world is ordered according to the expectation that Black people will move aside for them. It is a campus where the Black nod is a ready acknowledgement among staff and students of the daily microaggressions that happen here. I have been here through language policy debates where white people needed to be convinced that Afrikaans, as it is used here, is frequently exclusionary. I have been here through residence policy debates where white people needed to be told that not wanting to share a room with a Black person is not simply a cultural preference. I have been here through Open Stellenbosch and the reactionary backlash that followed, and I was here when a white student decided to stick up posters with Nazi iconography on them, calling for white students to unite to preserve their culture. To the outside world, the frequency of these episodes generates an obvious question: ���Why is nothing being done?��� It is a question that proliferates in many variations because there is a perception of institutional lethargy or intransigence before

I want to unfold this latest deployment of racism as what I term a history of bad relation. I define ���bad relation��� as a public interaction in which negative behavior occurs because the perpetrating party has sentimentalized attachments to ways of knowing that are harmful. At Stellenbosch University, the on-paper facticity of the university���s efforts at transformation exists simultaneously alongside an enrooted resistance to decisively confronting the problem of cultural and racialized parochialism. The university is an ongoing scene of intractability, in which the resilience with which racism resurfaces episodically is enabled by the university���s tendency to treat racism as an issue that must be soft-soaped to avoid alienating white people.

It seems almost a banal observation that the resilience with which racism persists at this university is due to the conditions which enable it to play out. I think that understanding what transpired in this way moves it beyond the logics of problem management, where the aim is to provide symptomatic relief: make the incident go away, and the problem is solved, goes the logic. Of course, there are many ways to tell the story of racism at Stellenbosch University. Some of them are divergent: some open up routes of questioning, while others close those foreclose those routes.

The late affect theorist Lauren Berlant coined the term ���genre flailing��� to describe a kind of crisis management that usually arises after a moment of disruption that intrudes on our confidence about how to understand the world. While I think it is necessary to talk about what has happened at Stellenbosch, I worry that in our flailing for a form of recognition, we risk departing from the scene of injury towards a more comforting abstract space where we shift the discourse to the enduring meta-problem of racism in South Africa. If these problems resist unseating, it���s because the premises are wrong. By insisting that we give our attentiveness to individual scenes of racist action, we move away from considerations of the embeddedness with which racism circulates here, the ways it finds new paths of renewal with each cycle of students, the way these intractable people attach themselves to the institution.

Sitting with the problemMy own path is to try to upend the issue. I teach classes where I engage with students about the ways in which we might understand political and cultural life through individual and collective experiences of mood and feeling. As a result, I���m interested in thinking about how Stellenbosch University���s ongoing racism problem might be traced to its insistence on soft-soaping racism. Whenever race ���turns up���, to use Sara Ahmed���s phrase, it is always as an interruption of the fantasy that racism is a problem that is being dealt with successfully at the university. It is a fantasy we are exhorted to make our own as people who work within the institution, but one that some among us have a greater investment in than others.

When I started working here, friends, family, and strangers with whom I fell into conversation, would all ask a variation of the same question: ���how do you work there?��� The ���you��� in this question is implicitly ���someone who is not white���, while the ���there��� corresponds to a perceived sense of the institution as unreformed from its history as an intellectual factory for Apartheid. The imagery that accompanied this question seemed derived from Apartheid���s hauntological picture gallery: intractable Afrikaners in khaki, a landscape deliberately scrubbed of Black people, a heartland stuck in the loop of an ugly cultural nostalgia.

The reality of Stellenbosch University is more Abercrombie and Fitch than AWB. The university has rebranded itself comprehensively as a future-forward institution of higher learning. It places its faith not in the clasp of tradition, but in the clean reassurance of corporate imagery. It aspires to run like a business. The varsity maroon t-shirt is a corporate uniform that expresses the idea that who is in the shirt does not matter once the shirt is donned.

My overriding impression of Stellenbosch University, 10 years on, is of a strange and unsettlingly ahistorical homogeneity designed to produce the idea that the unfortunate past has been banished in favor of an idyllic ���racial harmony,��� of the sort our oafish former chancellor called for recently. The vacuous sporting bonhomie of the Matie identity, and the persistent exhortation to embrace the empty signifier ���excellence,��� all seem to take very little stock of where we are, and who is populating the institution. Stellenbosch University is a predominantly white campus: the 2018 data (in a spreadsheet provided on the university website only in Afrikaans) has the numbers at 58.1% of enrolled students being white, and those demographic numbers give substance to the subjective impression I have of being in a demographically unrepresentative part of the country when I am on main campus. Most of my white students do not notice their whiteness because they are not encouraged to think of themselves as white people operating in a particular social moment, a social moment that is structured by various forms of inequality and dis/advantage. The workshopped discussions and student-circle initiatives that form part of the university���s diversity machinery do little to trouble the lived experiences of the many students for whom the fantasy of a white world is granted legitimacy here.

On the contrary, these students inhabit a world where they are encouraged to embrace a banal identity founded on the binding logics of the sports field. I recall how during the Open Stellenbosch disruptions, the recently installed Vice Chancellor declared that ���[W]e are all 100% responsible to be the change we want to see.��� He said this as though being untransformed was somehow the fault of those who came to Stellenbosch expecting it to be a South African university. A rejoinder to: ���We are not all responsible for the work of change, because it is not the duty of Black people to educate people out of their racist assumptions of ownership and belonging.��� During the week that this ���incident��� occurred, I noted with poignance the angry words of a Black student, who expressed her frustration that it was Black students who were being distracted by racism while white students quietly went on as though nothing had occurred.

When white students at this university behave in ways that are dehumanizing to Black people, it should not be read as occurring in a vacuum. Nor should it be assumed that these students are simply bringing their disagreeable styles of relation from home into the neutral university space. Rather, their intractability flourishes here because of Stellenbosch University���s seeming ambivalence towards it. I have seen enough to suggest that there is a sense, among many Black students and staff, of a latent ambivalence to the presence of Black people in this institution, which displays itself as a peculiar institutional lethargy. Suddenly, an institutional machine that runs as professionally as you would expect of a place that once saw fit to appoint Johann Rupert, the second wealthiest person in South Africa, to its chancellery, seems capable of only a befuddled shrug in response to racist behavior.

Whether perceived or actual, tacit indulgence gives validation to displays of obscene enjoyment by endorsing policies that endorse intractability as a socially unacceptable category of behavior to be negotiated with. Z���Socially unacceptable��� is not a dynamically policeable category, which is why people drive too quickly or listen to music loudly in places where there are prohibitions against these things. As a result, we sit with the strange scenario where the university can point to the strides it has taken in recent years towards creating a transformed and integrated university community, while issuing reports that testify to its skewed demographic. The same intractability means that while our students have sporadic discussions in residence about ���inclusivity,��� the university also grants its approval to openly bigoted figures like Helen Zille���the leader of the dominant party among white South Africans, the Democratic Alliance���who is given a platform to say cretinous and anti-intellectual things to influential sectors of the university, things that seem very much at odds with the ideas the university wishes to communicate about itself.

It could be argued that the university���s journey toward transformation must be seen in a longer, historically informed context. The problem with this thinking is that it assumes a linearity of cause and effect, where the end goal of an enfolding set of measures will be the achievement of a transformed university. This logic does not reckon with the ways that certain divergent energies���intractable people, right-wing groups actively pushing in the other direction���have overtaken the conditions that form the groundwork for policies, rendering them passe as they are implemented. The effect of this, for Black students and staff, is the alienating feeling of being drawn into conversations about why one deserves to be treated with humanity, all the while feeling that not enough is being done to create a space hospitable for all.

In a recent Facebook post, South African political analyst Eusebius McKaiser���writing incisively of a similar instance of institutionally-located racism���offered up the following questions:

Do these schools have explicit anti-racism policies? What do they look like? What do they say?What ���up until now��� has been the exposure of the perpetrator to curriculum content aimed at developing a young man who is anti-racist? Has he ever encountered such content, experiential learning modules, etc., or has it been assumed that simply having black classmates and the odd black staff member will guarantee respect for all people? Where is the evidence of EXPLICIT anti-racism curricula?Similarly, what explicit policies and procedures are in place to respond to acts of racism?I want to propose that a proper reckoning with racism at Stellenbosch University might begin with a consideration of these questions. While the cathartic expulsion of the ���bad person��� is a good step, one that can exist concurrently with the awareness that there are larger problems, the solutions being implemented need to move towards more robust anti-racist action that reckons with the constitutive violence of the institution.

We know that intractability is a globally resurgent psychosis, from North America���s conservative politics to the anti-migrant parochialism deforming Europe and Britain. There is enough out there to suggest that intractability is potentially lucrative, and so the depressing answer might be that Stellenbosch University���s lassitude arises because the intractable people who are persistently racist are also the people who bring in the money that keeps the institution afloat. But because a public university in South Africa is a shared object, those of us who are transforming the object through our backgrounds and our political projects must share it with people who want it to remain aligned with their fantasy. It is a problem of living that cannot be solved until we agree that being here means no longer accommodating bad relations in the name of a moribund idea of ���inclusivity.���

June 1, 2022

Imagining new stories, new freedoms, and new joys

Still from Rafiki ��

Still from Rafiki �� It���s difficult to think of anyone who has done more to illuminate the queer careers of African cinemas than Lindsey Green-Simms. Starting with her groundbreaking 2012 essay ���The Video Closet: Nollywood���s Gay-Themed Movies,��� which she coauthored with the redoubtable Nigerian writer, activist, academic, and African literatures expert Unoma Azuah, Green-Simms has forged a distinct path within the growing field of queer African studies. Newly published by Duke University Press, her book Queer African Cinemas (2022) is an invaluable contribution that confirms its author���s status as a leading Africanist working at the intersections of postcolonial thought, queer theory, and screen media.

Green-Simms���s task has been doubly daunting. It���s challenging enough to get scholarly communities to take African cinemas (particularly Nollywood) seriously, and harder still to convince naysayers that ���queer��� has any real currency on the continent. The book���s title, then, is a provocation. For not only is ���queer cinema��� discernible in and through African industries; it���s also multitudinous, varied, and diffusive. It demands the plural form that Green-Simms assumes. Her book, while it cannot be comprehensive, offers rich insights into the queerness of audiovisual cultural production (and reception) in key national and regional contexts. Green-Simms rightly notes that some African media industries are simply more prolific than others���that it makes sense to scrutinize developments in and around production hubs in, among other megacities, Lagos, Nairobi, and Cape Town. But she does not deny the existence of other, smaller sites of production and reception���including those yet to be ���discovered.��� After all, queerness itself is illimitable, and potentially locatable in ���unlikely��� places. Queer African Cinemas is magisterial, but���excitingly���it is not the last word on the subject. Green-Simms has written a clear-eyed, authoritative book on which future studies will be obliged to build.

Queer African Cinemas is framed by recent events, registering ���the upsurge in homophobia that swept up many African countries in the first decades of the twenty-first century.��� Indeed, the intensification of anti-gay and anti-trans legislation in Nigeria (which saw the signing of the far-reaching Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in 2014), Uganda (where the bluntly named Anti-Homosexuality Act was signed just one month later), and other African countries is one reason for the aforementioned reluctance to take the notion of ���queer African cinemas��� seriously. If homosexuality is illegal (and Nigeria���s Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, at least on paper, criminalizes even support for LGBTQ rights), then how can queer movies be made? Green-Simms offers a brilliant, deeply theoretically informed, and altogether inspiring answer to that question, highlighting filmmakers who have endeavored to ���find alternatives to the violent heteronormativity that continually threatens hopes of queer belonging and life-building.���

Queer African Cinemas thus avoids the sort of pessimism that would simply deny queer Africanity���or, in an equally essentialist mode, consign the continent to the reactionary shadows. At the same time, Green-Simms acknowledges (and includes in the eponymous category) some patently anti-queer films, like Dickson Iroegbu���s Law 58 (2012), which opens with a text that denounces homosexuality as an ���inordinate act.��� Simply put, Queer African Cinemas is not fettered by respectability politics. Green-Simms is not out to emphasize only ���positive��� representations. Indeed, her book is queerly open to interpretive possibilities, to a greater degree than anything I���ve read on the subject. It offers a model for how to ���do��� queer African studies.

Central to this model is Green-Simms���s nuanced account of the concept of resistance. She asks, ���What happens when we see resistance not as the opposite of subordination and complacency but as something that is entangled with it? While resistance is often assumed to be transgressive or in opposition to power, it can often mean the exact opposite.��� She also queerly considers some of the complicated legacies of European colonialism. Queer African Cinemas specifically looks at how British penal codes written around the turn of the twentieth century continue to structure the criminalization of homosexuality and same-sex marriage in Nigeria, Uganda, and Kenya. Indeed, anti-sodomy laws drafted in 1897 have not only remained on the books in Nigeria but have also been expanded in recent years.

Queer African Cinemas is no simple inventory of LGBTQ images. It also engages the political economy of commercial filmmaking on the continent. In the case of West Africa, that means emphasizing that FilmHouse, the largest theater chain in the region, is a vertically integrated company with a production and distribution branch called FilmOne. Green-Simms���s work demonstrates what���s dangerous about a firm like FilmHouse having such disproportionate power in West Africa. She writes about how FilmOne agreed to stream the queer-friendly 2018 Nollywood film We Don���t Live Here Anymore but then got cold feet and pulled the film from its Nigerian site���allegedly in response to subscriber complaints, but probably also out of fear of government reprisals. In Nigeria���s current first-run theatrical marketplace, there are precious few alternatives to FilmHouse, as Genevieve Nnaji recently learned when her directorial debut Lionheart (2018) was denied a significant big-screen release despite the superstar���s best efforts. Yet for all these hurdles, queer African cinemas survive, including in festival spaces and other idiosyncratic locations to which Green-Simms is admirably alert.

Queer African Cinemas is, then, attentive to conditions of production, distribution, and consumption on the African continent. An introductory chapter explains the historiographical and theoretical stakes of Green-Simms���s arguments. Chapter 1 adopts a regional perspective to consider the queer credentials of ���West African wayward women��� in an array of films produced over a number of years. Chapter 2 considers the complex and often contentious process of negotiating queer characters and themes in Nollywood films. Chapter 3 investigates postapartheid South African cinema, and Chapter 4, returning to the regional vantage of the first chapter, offers an eye-opening account of ���queer love and critical resilience��� in East Africa. A coda offers the author���s thoughts on the possible futures of queer African cinemas, including through a breathtaking reexamination of Mohamed Camara���s canonical Dakan (1997)���a film that, like Green-Simms���s book, ���holds space to imagine new stories, new freedoms, and new joys.���

Climate change as class war

Photo by Matt Palmer on Unsplash

Photo by Matt Palmer on Unsplash It goes without saying that the climate crisis is the problem of our time. Yet, despite rhetoric from governments and big corporations that structural changes are imminent, none seem to be forthcoming and emissions continue apace. How come? Professor Matt Huber joins Will to discuss his latest book, Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet (Verso, 2022).

Professor Huber argues that the only way to confront climate change is to build working-class power on a planetary scale. What kind of politics does this entail, and if the working-class is the agent of change���who, exactly, is the working class? Professor Huber is an assistant professor of geography at Syracuse University and is also the author of Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom, and the Forces of Capital.

Listen to the show below, and subscribe via your favorite platform.