Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 105

March 4, 2022

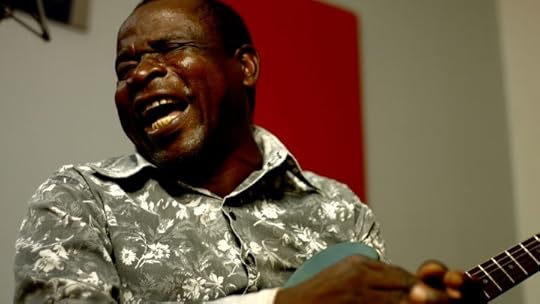

Tram 83, a soundtrack

Image via author.

Image via author. Africa Is a Country Radio continues its literary theme for its third season on Worldwide FM. The third installment in our theme of African literature is inspired by the debut novel from Fiston Mwanza Mujila, Tram 83. The story takes place in the fictional City-State, a resource rich secessionist state in central Africa. In the book, a nightclub, Tram 83, serves as a gathering place for all the characters in the book: from shady international businessmen to miners and students to sex workers and mercenaries.

While at times it may be grotesque or exaggerated, the essence of Tram 83 is not unlike some of the nightclubs that I have been lucky to experience around the world (not just in African cities, but from Dubai to San Francisco to Rio de Janeiro). These are places that have also influenced my own musical tastes. So, as a dedication to all the central places of gathering at or of the global margins around the world, I present Tram 83, a soundtrack.

Listen below, get the tracklist on Worldwide FM and follow us on Mixcloud.

March 3, 2022

The Russians are here

Photo by Alice Kotlyarenko on Unsplash.

Photo by Alice Kotlyarenko on Unsplash. A week into Russia���s war with Ukraine, the global, geopolitical fissures are starting to crystallize. Russia���s defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, announced that it would stage an ���anti-fascist��� conference in August; with the list of planned invitees so far including China, the UAE, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia. One wonders whether other African countries will follow Abiy Ahmed���s increasingly despotic regime is joining this coalition of ���anti-fascist��� (read anti-liberal) states (Africa���s voting patterns on UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/1: one against, 17 abstentions, and eight absentees, is an early indicator). Indeed, Russia���s aggression is now being cast���after obligatory mention of the Ukrainians���as a challenge to the liberal international order.

These are the terms on which this war is now framed. The great confrontation of the 20th century was between capitalism and communism, the one before us, so we are being told, is between liberalism and illiberalism. Receding into the background are the Ukrainians themselves, and further still, the fact that both the West and Russia bear responsibility for this situation. As Jacobin staff writer, Branko Marcetic summarized: ���The latest escalation in the Ukraine crisis requires us to hold two ideas at the same time: that Vladimir Putin bears much responsibility for the immediate crisis, and that the long-standing US refusal to accept limits to NATO expansion helped bring it about.��� Anatol Lieven made the same point in an interview with Prospect Magazine.

This nuance evades most mainstream coverage and commentary. American liberals���the most powerful of that orientation globally���are now warmongers. They want a deathmatch with Putin, who, to be sure, is deplorable. But for them, this is about reinforcing a great power status as Russia, and especially China, threaten to bring about a properly multi-polar world. It remains that there is no reason for NATO to exist, no reason for it to expand either. Still, at the encouragement of mainly the US and UK, Ukraine was encouraged to join NATO, even though there had never been sincere intention to mobilize NATO���s defensive capacities to aid Ukraine were it to come under attack. As a matter of political realism, top foreign policy thinkers have been warning for years about how such posturing would end. The deafening silence to Zelensky���s pleas for more Western support is the surest proof of its hollowness as a dream sold to Ukraine by the West. Anatol Lieven again:

We never had the slightest intention of defending Ukraine, not the slightest. Even though Britain and America and the NATO secretariat to the Bucharest Conference in 2008 came out for NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia (the NATO HQ was completely behind it on American orders), no contingency plans were drawn up, not the most remote or contingent ones, for how NATO could defend Ukraine and Georgia. There was no intention of ever doing that at all.

While sharply criticizing the West���s role for creating the conditions for conflict is one thing, it is another to exonerate Russia completely and claim its posture is defensive. So goes the bizarre line being peddled by tankies and Russophiles eager to construe Russia���s aggression as an anti-imperialist advance. In this thinking, America is the one true evil and anyone standing up to Uncle Sam, a hero. Nationalists (and nationalists parading as leftists) in Africa justify solidarity for Putin���s invasion by referencing the close ties between the Soviet Union (of which, lest we forget, Ukraine was a part) and various anti-colonial movements during the Cold War. This is true, but assuming ideological continuity between the former Soviet Union and Putin���s regime betrays both ahistorical fantasy and willful stupidity. Putin himself attributes Russia���s seemingly inferior position in world politics to the communists of yesteryear while being viciously anti-communist today.

It���s no surprise then, that upon further scrutiny, those pro-Russia types are the same characters prone to glorify authoritarianism elsewhere���be it Paul Kagame in Rwanda or Narendra Modi in India. For them���like those populist sympathizers of former South African president, Jacob Zuma���the Bonapartism embodied by Putin makes for a seductive model of governance. As resonant is Putin���s anti-West, supposedly nationalist, worldview, which dovetails with the ambitions of Zuma���s ���radical economic transformation��� and sets the standard for state capture. Tom Parfitt���s 2014�� interview of ex-Kremlin adviser Geb Pavlovsky in The New Left Review explains as much:

[Putin���s] thinking was that in the Soviet Union, we were idiots; we had tried to build a fair society when we should have been making money. If we had made more money than the western capitalists, we could have just bought them up, or we could have created a weapon which they didn���t have. That���s all there is to it. It was a game and we lost, because we didn���t do several simple things: we didn���t create our own class of capitalists, we didn���t give the capitalist predators on our side a chance to develop and devour the capitalist predators on theirs.

Putin and his apologists are anti-West simply because they long to be in its commanding place. Not against schoolyard bullies, but irritated they aren���t the biggest ones. Nationalism, as authors like Adom Getachew carefully show, was a positive force in the 20th century. Anti-colonial nationalists sought not only independence for themselves, but also the reconstruction of the international state system along egalitarian lines. Now, nationalism is a spent force, made redundant by irreversible globalization. Putin���s to-do about Russia���s glorious past and his role in preserving it serves mostly to legitimize the billionaire class that his regime spurred. And, like nationalisms elsewhere, it mystifies class cleavages in society and the economic stagnation wrought by it. Often overlooked in the analysis of the crisis is its political economy, as a clash motivated less by national feeling of the many, but monied avarice of the few. Sam Greene pointed out before the invasion (and before Russia would find out that invasion would prove a grave, economic miscalculation):

The expansion of EU influence puts insurmountable pressure on the Russian political economy to move from a rent-based, patronal model of wealth creation and power relations, to a system of institutionalized competition. Having satellite states that are governed in the same patronalist mode as Russia gives Moscow geo-economic breathing space, adding years or decades to the system���s viability. Losing those satellites removes those years and decades.

The anti-imperialist stance is not on the side of the West, nor with Russia (and by extension, China). It is refusing to pick a side in an elite-serving great power conflict using Ukraine as its proxy. The anti-imperialist position is non-alignment from below and encourages our states to follow such a foreign policy. The African proverb that history���s great purveyor of non-alignment, Kwame Nkrumah, was often wont to recite goes: ���When the bull and elephant fight, the grass is trampled down.��� Non-alignment, then, does not mean indifference���it means solidarity with those who stand to suffer from war most, and against war because it causes suffering for most. Therefore, we must be unequivocally anti-war, and unconditionally in solidarity (not unlike that which was afforded to the plight of Black Americans last summer) with ordinary Ukrainians, and ordinary Russians, who did not sanction this war and will endure greater repression as they take to the streets to oppose it. The best advice is from Gregory Afinogenov, an assistant professor of Russian history at Georgetown University, in Dissent Magazine:

Those in the West who sympathize with the plight of Ukraine have no choice but to trust in Ukrainian and Russian resistance to Putin���s war. Thousands of Russians have already been arrested for protesting against the war, a number that is sure to grow significantly as the war expands. Millions of Ukrainians don���t want to die in bombings, live under imperial rule, or be forced into emigration; millions of Russians don���t want to be immiserated by sanctions or be conscripted into an invasion that gains them nothing. In our response to the war, we should be careful not to simply echo Russia���s nationalist elites���they think blaming NATO will shift attention away from their increasingly repressive, kleptocratic, and militarist rule at home. Our loyalties must lie with the people of both Ukraine and Russia, and with the cause of peace.

The well-documented racism and xenophobia against Africans fleeing Ukraine, whether by Ukrainian border guards or their Polish counterparts or by ordinary Poles, has made some Africans tune out or be ambivalent. But why are we surprised?�� Once again, we must resist the instinct to see the unfolding catastrophe through the prism of culture war. We can admit both the horrendous treatment of Africans, while standing with the Ukrainian people and Russians bravely opposing Putin���s war from within. Nor should the occurrence of the latter be license to spitefully side with the Russian state���as if Russia is an anti-racist paradise! Some corners of what is dubbed ���Black Twitter��� online, mainly influenced by American cultural and race politics, have done so over the last few days.

More dangerous, is to treat the war as if it had no bearing on Africa. Immediate concerns surround the dependence of some African countries on Ukrainian and Russian imports, and given Russia���s ramped-up presence on the continent, the implications beyond the short-term will be profound. In itself, the financial war playing out will have reverberations beyond Europe and North America, and if the possibility of nuclear escalation becomes less remote, well, the global fallout from that should be clear.

There is truth to the Western prognosis that Russia���s aggression is a challenge to the post-Cold War, liberal international order. The deeper truth is that it has been crumbling for longer than they cared to realize. The hypocrisy being called out now, on the West���s actions in Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, Yemen, Kashmir the Sahel, and especially Palestine, tell us that the ���rules-based��� international system was a fiction from the start, in place to consolidate Western dominance. Putin is not the first to fight a hugely unpopular war. Furthermore, although the West will inflict as much economic pain on Russia as it can, it will preserve its material interests, and will not go as far as prohibiting the trade of Russian oil and natural gas on which its economies are dependent. We must�� take advantage of this moment. Call the West on its double standards. Why are Ukrainians ���freedom fighters��� when they pick up arms, but a young Palestinian throwing a stone at an Israeli tank is a ���terrorist���?

Outside of the media, the space where we have seen Western double standards on full display the most, is sports. In the last week, FIFA and UEFA, which control global and continental football in Europe respectively, went from hedging about the war (Russia���s national team could still play fixtures but sans national colors, anthems, and flags) to an outright suspension of all Russian national and club teams from its competitions. Similarly, some of Europe���s top clubs funded by Russian money, most notably Chelsea, Everton, Schalke, and UEFA itself, have cut ties with Russia���s oligarchs. Anyone familiar with FIFA, or any of the other global sports bodies known for their reticence to punish Russia, was thrown for a surprise. Just last month, the IOC, which organizes the Olympics, allowed Russia to compete despite its national teams openly using banned substances to increase their chances of winning. Also, with the exception of the sports boycott against Apartheid South Africa, FIFA has rarely acted against rogue states, especially ones who illegally occupy and oppress others: Saudi-Arabia in Yemen, the US and its various invasions and occupations in the past, Morocco in Western Sahara, India in Kashmir, and Israel over the Palestinians, just to name a few. Israel���s case is one that hits closer to home for European football: Israel is a member of UEFA.

Perhaps, after Russia and Ukraine inevitably sit around a table to negotiate a new relationship, another consequence may be ushered in���one in which global hypocrisy and obfuscation, whether by the world���s governments, media, or publics, about the suffering of others that don���t look like “us,” have to face up to their own light. And then imagine, together, another kind of world, underlined not by great power competition, but solidarity binding ordinary people across borders. As Nkrumah put it, facing neither East nor West, but forward.

Probably not. Still, we dream.

March 2, 2022

When people cough, black stuff comes out

Image credit Estacio Valoi.

Image credit Estacio Valoi. This investigation was produced with support from the Information for Development Trust and conducted in partnership with Mozambican NGO Justi��a Ambiental. It was first published on the ZAM Magazine website. It is republished here with the kind permissions of the magazine and the author.

A troubling pattern of land-grabbing, violence, pollution, and death in Mozambique���s Tete province contradicts a Brazilian coal mine���s claims of ���responsibly sourced��� coal. It also shows, once again, that Mozambique���s government authorities and security forces are squarely on the side of those responsible for the damage.

Six years ago, the plunder of rubies in Mozambique���s Cabo Delgado province made headlines around the world, mainly thanks to work I did. Most shocking was the fact that Mozambique���s ruling Frelimo party government seemed to be fully on the side of the mining interests, in which prominent Frelimo individuals shared as shareholders and directors. It never intervened to protect locals who were violently removed from their land and sources of income, partly by the Mozambican police Rapid Response Unit.

Sadly, there has been no change in the ruling elite���s attitude when it comes to the exploitation of the country���s abundant resources. This article documents more such plunder, including fish and seafood, wood, and other natural resources.

Fifteen years ago, in 2007, the Mozambican government signed a mining contract with Brazilian coal mining company VALE in a partnership with Mitsui Corp. The Moatize coal mine in Tete province was officially inaugurated in May 2011 and now produces 11.3 million tonnes of coal annually. In January 2021, VALE announced plans to pull out of the project and, in December 2021, entered into a binding agreement with Vulcan, part of India���s Jindal Group, to sell the Moatize coal mine as well as its projects in the Nacala Logistics Corridor (for which a community of 2,000 families were resettled). However, this transaction can only take place if the Mozambican government approves it. Whether it would do so was not clear at the time of publication of this article.

A new investigation, in partnership with the environmental NGO Justi��a Ambiental, has found that in the past decade more than 1,300 families were removed from their homes in Tete province to make way for a VALE coal mine. Most of these families had relied on subsistence agriculture, cattle raising, and brickmaking from clay found at the river banks. They were removed to resettlement areas with allocated houses plagued by faulty infrastructure, as well as poorly installed electrical and sewage systems. With the almost daily explosions in the mines, more than 1,000 houses now have cracked walls, and many have already collapsed.

Even worse, the resettlement areas have very poor soil, are far from markets and without access to water. The rivers that once provided the communities with water for farming, cattle, and other basic needs were diverted to supply water to the mine, polluted, or simply buried by tons of sand.

In Moatize, today, thick black clouds blanket the skies every time dynamite is blasted in the mine, the surfaces are always covered with black dust, and maize flour can no longer be left to dry in the open air. There is a great lack of water, and what comes out of the tap is black like coal. The cattle, left without pasture, survive on garbage dumps scattered throughout the city of Moatize.

The total number of citizens in Tete province affected by the pollution is estimated at roughly 500,000. Among them are many who complain of coughing and general ill health. ���Here, when people cough, black stuff comes out and the doctors say it���s mine dust,��� a community member tells us, adding that ���…once, VALE, the government and a team from the hospital came to test people for a week. They saw that they had a cough, and that they were spitting out black things. But the company never returned to report back.���

According to a hospital official who requested anonymity, most of the patients treated at the Moatize Hospital are diagnosed with tuberculosis. ���Every day, here at the hospital, we receive a greater number of people with tuberculosis. We think it is due to the pollution. This (VALE) company is hurting us, even I am feeling sick,��� said the official, continuing that the hospital ���also saw many people who had been drinking dirty water from the river.���

According to laboratory analyses carried out on water in 2021 at Justi��a Ambiental���s request, water and air pollution are three times above the national and international limits established by law. Cadmium levels of 0.009 mg/l were recorded in VALEs concession area, while the levels considered admissible by Mozambique and the World Health Organization are 0.003 mg/l. Cadmium is a heavy metal that causes damage to the nervous system and can cause disturbances in fetal development, even in low concentrations.

Besides the pollution, the area has become generally unsafe, especially for children. In September 2014, Ester Eduardo Pinto (14), from Primeiro de Maio, was buried alive by a dump truck while playing in a hole in the sand. In the same month a group of children drowned when trying to bath in a hole abandoned by VALE. Six years later, in November 2020, in Cateme, a child died and four others were seriously injured when they stumbled upon an old war mine while playing inside the resettlement built by VALE.

In the case of Ester, VALE paid the family 5,000 meticais (USD78) ���to help with funeral expenses. In none of the cases did VALE or the government accept any responsibility.

Image credit Estacio Valoi.

Image credit Estacio Valoi.Moatize���s peasant farmers and brickmakers have been trying to get compensation for their loss of livelihood. VALE has compensated some of those who were forced to hand over their land to the mining company, but many others claim they were left out of the agreements. Cases regarding compensations, and equally promised new land allocations and social projects, date back to 2008, 2010 and 2012, with very little, if any, progress.

Zita, a widow in Paiol, told us how she and her now deceased husband Refo Agostinho were gradually forced to give their land away to VALE. For her and Refo, brick making had been a hugely successful enterprise. It had fed their four children, paid for their school and covered other needs. The demand was such that they eventually employed fifteen workers and also built a house and bought a car. Then Refo expanded into milling, welding and panel beating, while Zita tended to her farm in nearby Canchoeiro. ���For 20 years we developed this activity,��� says Zita. ���Then VALE took everything from us.���

The couple were officially entitled to compensation for the brickmaking, milling and farming land that was taken by the mine. But VALE kept them tied up in delays. ���They would say process X had to go through to position Y, but they always refused to give us money, continuously talking but without a solution��� says Zita. Others experienced similar treatment. ���So we organized protests to demand compensation. But the police arrived, intimidated (us) and took (Refo) to jail.��� In the end, the Agostinho family received about 60,000 Meticais, not even a few months of the income that Zita and Refo Agostinho had generated before.

Zita is convinced that Refo died because of what happened. ���He suffered stress and grief after that. He had stomach aches and blood pressure problems, and eventually died of a heart attack. Now, I support the children alone. I depend on a single mill, which he left to us.���

Likewise, Paulo V��tor Maferrano (41) from Chipanga in Moatize, made around 30,000 Meticais per month from farming and brickmaking. ���The mining company started occupying Chipanga in 2008, which they initially said they would not do. People who were removed from other areas had already come to Chipanga to make their machambas (small plot farms). But then suddenly, VALE started moving us out of Chipanga too.���

Left without his machamba and his brickworks, Maferrano and his colleagues and neighbors lodged compensation forms. ���We went to both the government and VALE. First they said they were going to give us 60,000 Meticais to leave our fields and stop our activities, and then they would give us 125,000 Meticais in compensation. That was in 2008. 2021 is about to end and people have not been compensated yet.���

Representative Nordino Timba Cha��que of the Nhankweva brickmakers commission, a group of close to 600 brickmakers, says he is fed up with VALE���s ���neverending promises and unfulfilled agreements��� with the local communities over the years. ���About 500 or so people, from a total of around 3,000 brickmakers, received 60,000 Meticais to stop their activities. But that was not the compensation. VALE still had to pay 125,000 Meticais to each of us. We never received that. They kept telling us to come back.���

Recently, however, VALE suddenly stated it will no longer pay any compensation to�� brickmakers at all. ���It announced that it no longer recognised us and that we are not part of the registration lists,��� says Cha��que. ���They said that the lists had been tampered with by infiltrated people from the community. But there were government staff and technical staff from the municipality involved with the lists, together with VALE. How could people have infiltrated?���

A former employee of the company that was contracted by VALE to draw up the compensation lists, confirms. ���There are 5,000 people on the lists,��� says the employee, who asks to remain anonymous. ���But VALE started accusing us of putting extra people on the lists in exchange for money, which is not true. We were even expelled. They confiscated our private phones and searched them.���

In the meantime, the situation has worsened. In 2019, VALE started the expansion of the Moatize III Mine, an extension that cut several neighborhoods off from the Moatize River. Meetings between the mine, the government and affected communities have not resulted in any compensation so far.

Protests from the communities have mostly been met with violence and intimidation. On May 6, 2021 a group of brickmakers and peasants occupied a section of the mine, blocking its access road, to demand answers from the company. The protest ended peacefully when brickmakers agreed with representatives of VALE and a government delegation that the matter would be debated the following day with the entire community in the neighborhood square. However, the VALE and government delegations never showed up to the meeting. Instead, the police came.

���Suddenly, we realized that the UIR [Rapid Response Unit] and the people were running from one place to another,��� recalls Vasco, a local, who was at home at the time. ���There were gunshots. They threw tear gas. I decided to pick up my six-year-old son from school immediately. When I got back home, we got inside the house and I shut the door. But everytime they have a meeting here (at the community square), they come to borrow my chairs. So, amidst the havoc, a neighbor came to return the chairs. He knocked on the door, I peeked out the window and only saw him. I didn���t know he was accompanied by a UIR agent. I opened the door and the agent shot me in the stomach. No questions asked. Nothing. He just said ���these are the agitators��� and fired the gun at me.���

Thanks to his small son, who called his mother from his father���s cell phone, Vasco received transport and hospital care. ���If it hadn���t been quick, I don���t know what would have happened.��� According to Vasco, the doctor told him that black particles found inside his body during the operation could have been dust from the mining company. ���He said that this could be the dust we inhale every day.���

Since he was shot, Vasco���s health is not the same. He can���t do tasks like weeding or carrying water, and at work as a truck driver for a security company contracted to VALE, his wound pains him.

���When I put on the seat belt, it goes through my belly here, and I still have stitches��� the government was aware of what happened to me, and nobody came here to even see how I was doing.”

On November 20, 2021, four representatives of families whose homes have cracks were detained when they tried to complain to the mine. They remained in prison for three days. Shortly afterwards, on December 23rd, two brickmakers were equally detained, this time for five days, after a community meeting where VALE’s refusal to pay compensation was discussed.

Meanwhile, according to three interviewed local journalists who asked to remain anonymous, the media have been instructed by local authorities to ignore the injustices around the VALE mine. ���The (state) radio directors told us to only talk with VALE directors, not with the locals nor with the oleiros (brickmakers). Moatize���s Mayor, Carlos Portim��o, who has a history of attacking and threatening journalists, is widely suspected to be behind such instructions.

In the past two years several attempts have been made to obtain documents from VALE. But even though the company regularly proclaims that transparency is its policy,�� and has promised such transparency also in community meetings in Moatize, none of the requested information has been forthcoming. When Justi��a Ambiental went to court to obtain access to VALE���s environmental monitoring reports from 2013 to 2020, it obtained a favorable court judgment. But, the mining company, argues that the reports are of a ���confidential nature,��� is still withholding them, and has appealed.

In 2020, the Mozambican Bar Association (OAM) had already successfully asked the courts to subpoena VALE to make available ���…information of public interest,��� including the Memorandums of Understanding and other agreements signed between the government, VALE Mo��ambique and the affected communities.The OAM had also requested information regarding ongoing resettlement processes and the total amount of taxes paid by VALE to the Mozambican state. Although the Administrative Court of the City of Maputo mandated VALE to provide the information and also dismissed the company���s subsequent appeal, VALE has yet to provide the documents.

The schism between promises and actions is also present at VALE���s mother company, VALE S.A. in Brazil. According to communications received by Justi��a Ambiental, several of those present at a shareholders meeting held in Rio de Janeiro in April 2021 voted not to approve the management report, which omitted important information about the projects in Mozambique. These shareholders also requested numerous documents of public interest, including the ones requested by Justi��a Ambiental and the OAM. Senior executives of the company then pledged to send the requested documents from headquarters, but none have been forthcoming.

VALE did not respond to requests for comment sent during the preparation of this article. Neither did the Mozambican police, nor the Mozambican Ministry of Mining and Natural Resources.

March 1, 2022

A Total mess

Image credit Justi��a Ambiental via Facebook.

Image credit Justi��a Ambiental via Facebook. Since oil and gas multinational TOTAL showed its face in Mozambique, it has brought nothing but disaster and suffering. In Cabo Delgado province, where it leads the offshore $24 billion Mozambique Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) project, it has irreversibly destroyed the lives of people, before it has extracted even a drop of gas. In February, Total boasted that it had made an annual profit of $15 billion in 2021 . This money, which will buy shareholders the freshest oysters and the best French champagne in Paris��� most expensive restaurants, was made from the bodies and lives of people, mostly in the Global South, and at the expense of the economies of developing countries.

TOTAL is one of the biggest players in Mozambique���s gas industry, and to prepare for future gas extraction, it is constructing the onshore Afungi LNG Park, which houses the aerodrome, treatment plants, port, offices and other support facilities for many of the projects and contractors. To make way for the 70km2, the company displaced more than 550 families from surrounding communities. Fishing communities who had been living mere meters from the ocean for generations were displaced to a ���relocation village��� more than 10km inland, with no way of accessing the sea. Farmers who had now lost their land, were given small, inadequate pieces of land far from the relocation houses they had been given. These communities have lost their livelihoods and have been left destitute.

The climate and environmental impacts of the project will be irreversibly devastating: gas extraction will lead to the elimination of several endangered species of fish, flora and fauna of the Quirimbas Archipelago, a UNESCO Biosphere, off the coast of Cabo Delgado. The methane emissions from the construction of just one LNG train will increase the greenhouse gas emissions of the whole country by up to 14%.

Since 2017, communities in Cabo Delgado have faced horrific violence, first by insurgents and then from Mozambique���s military. TOTAL was well aware of this violence when it took over the project in 2019, which was more than two years after the first attacks were reported. Following a major insurgent attack on Palma village���the nearest large village to the Afungi Park���in March 2021, TOTAL�� decided to abandon the area and ongoing processes with the communities, claiming ���force majeure��� (i.e, that because of the insurgency it could not fulfill its business obligation) and pulling its staff out of the area, pausing the project indefinitely. It was clear during this attack that the Mozambican army was only interested in protecting TOTAL���s assets; 800 soldiers defended the Afungi park, while only a handful were defending Palma and civilians. Once TOTAL left, they stopped compensation payments to community members completely and have not fulfilled their payment obligations to contractors, including small Mozambican businesses.

The gas industry has been central to this violent conflict between insurgents, the Mozambique, South Africa and Rwanda armed forces, and mercenaries. So far, it has displaced 800,000 people, many of whom are now in refugee camps in neighboring Nampula province. While TOTAL and the other industry players, as well as the Mozambican government, immediately dubbed the attackers as ���jihadists��� or ISIS, the reality is much more complex. Locals were promised jobs, but have only received temporary, menial and unskilled work, while watching TOTAL and government elites plunder their land. This increase in poverty and marginalization and oppression has led to social tensions further fuelling the conflict. Local people have reported situations where the Mozambican military that had been deployed to protect them against insurgents, extorted people for their compensation, sometimes holding beneficiaries hostage, or threatening their families with violence (including sexual assault).�� Despite being aware of the actions of the military, TOTAL requested that the government deploy more Mozambican troops to protect their assets. The government also contracted a South African private security company, Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), to fight insurgents. However, locals reported that DAG helicopters fired indiscriminately at civilian infrastructure. The company���s contract was quietly not renewed.

Deployed in July 2021, the Rwandan army is notorious for the horrific torture of alleged Congolese and Rwandan dissidents in military detention centres. Although TOTAL insists that it has nothing to do with the Rwandan army���s presence in Mozambique, the company has a history of basing its operations in politically sensitive areas.

In Myanmar, TOTAL was providing the oppressive military junta with the majority of its revenue through the Yadana gas project. The military junta is known for ethnically cleansing the Rohingya population and committing mass human rights violations including rape, sexual abuse, kidnappings and torture. Recently TOTAL claimed it would stop its operations in Myanmar, but again, it will be getting away with the destruction it has left in its wake. In Yemen, the Balhaf LNG site (of which Total owns 39%), was exposed for housing the base for the Shabwani Elite, an UAE-backed tribal militia. Officially a counter-terrorism group, they have unofficially become known as a group created to protect fossil fuel interests. The site also has also been revealed to house UAE notorious ���secret prisons��� holding Yemeni detainees.

From the moment TOTAL came into the picture, it has searched for ways to avoid responsibility for its actions and the generally onerous impacts of the extractives industry. One way it does this is by blaming everything on Anadarko, the US company that initially led the Mozambique LNG project, until TOTAL took over in 2019. Anadarko had started a sham of a consultation process, which violated several principles�� of free, prior and informed consent. Community members were unable to dissent in consultation meetings or through the committees set up to represent them, for fear of reprisal from the government or of not receiving adequate compensation. Community leaders were often corrupted and in some instances, gave false consent on behalf of the community.

Despite knowing the issues with this process, TOTAL made it worse and even less democratic upon taking it over. Instead, it took advantage of the worsening conflict and its climate of chaos, fear and repression to fast-track the consultation process. So when the military and police provided security for consulting teams, the atmosphere of fear had already silenced the voices.�� Communities have filed complaints with TOTAL, informing them about the irregularities and dangers of compensation payments. Although TOTAL ignored these complaints, or waved them away, they cannot say they were unaware. Meanwhile, the company claims that Mozambique LNG will be a way to lift millions of Mozambicans out of poverty. But history has shown that even though the country has hosted several extractive projects over decades, none of them have benefited the people, with the economy only becoming increasingly worse. Still, only one-third of the population has access to electricity and TOTAL will not provide them with power���the vast majority of it will be exported to other countries, like the UK, US, China, India and the Netherlands.

Furthermore, the Mozambican government has a history of corruption involving fossil fuels. TOTAL is undoubtedly aware of the “tuna bonds” scandal of 2016, currently at the center of Mozambique���s biggest ever corruption trial. Mozambican officials took an illegal $2 billion loan from Credit Suisse and VTB Bank, promising to pay back the money in gas revenues, while spending it on weapons to protect gas reserves. One doesn���t need more proof than this to know that the gas revenues will almost certainly not trickle down to the people. Mozambique is still trying to climb out of the debt crisis and deep financial hole this deal pushed them into. By going about its usual business with the Mozambican government in the face of this racket, TOTAL is merely enabling and normalizing corruption.

The gas industry will be a major economic disaster for Mozambique, and TOTAL is actively ensuring that the country receives little benefit: the Mozambique LNG consortium, of which TOTAL is the leader, along with the other consortiums of Rovuma LNG and Coral LNG, have subsidiaries in tax-havens, such as Dubai, through which the gas revenues will flow. Mozambique has a double tax agreement with Dubai, which means the consortiums will not pay the 20% withholding taxes on interest and dividends as they would have done under Mozambique���s tax laws.

A recent report by Berlin-based company OpenOil shows that this means Mozambique will lose $5.3 billion in tax revenue over the life spans of Mozambique LNG and Coral LNG. Furthermore, the consortiums have also received an 8% corporate income tax reduction from the Mozambique government for the first eight years of production. It is clear that those making decisions about the gas industry in Mozambique, both locally and on a global scale, are unperturbed by the impact of gas on the climate, people and economy of the country. Human rights defenders have brought this disastrous situation, in detail, to the attention of those financing, investing in, benefiting and purchasing from the industry. These include the governments of the UK, US, South Africa, Italy, France, Netherlands, Japan, Standard Bank, HSBC, BP, and many others.

Yet they feign ignorance or find lame excuses to ignore the suffering of affected communities and face the grim reality to which their profiteering is contributing. It has become clear that the gas industry calls the shots, and governments simply go along with them. Northern companies and governments who wax lyrical about their stringent human rights policies are unconcerned about violating those of the Mozambican people. While they tell anyone who will listen that they are moving away from fossil fuels in their countries, in Africa and the Global South they are merely planning more, thinking no one is watching. It has become clear that the people of Mozambique cannot rely on the decision makers in power to protect them, the environment, or climate against TOTAL, and the global fossil fuel industry. These decision makers are well aware that the gas industry will just continue to line the pockets of the local and international political and economic elites, as it has done for generations.

Civil society and activists need to deal with TOTAL directly, to support the people whose homes, lives and livelihoods they are destroying, to bring their voices to international podiums. Fights have been won before: in 2020, the community of ��Xolobeni in the Eastern Cape region of South Africa, won a groundbreaking court case that ultimately pushed Transworld Energy Resources to halt its heavy mineral sands mining project. And in the last few months alone, two campaigns ruined Shell���s plans. The Stop Cambo campaign against an oil field in the North Sea, pushed Shell to pull out of the project after the campaign became so so strong that members of the UK and Scottish parliaments were forced to discuss it and ultimately pushed back against the project. In South Africa, fishing communities and activists won a court case making Shell halt its seismic drilling in KwaZulu-Natal. Furthermore, the UK High Court will soon rule on a legal challenge by Friends of the Earth England, Wales and Northern Ireland, with the support of Justi��a Ambiental, to cancel the UK government���s $1.15 billion financing of the Mozambique LNG project. With the Mozambique LNG project on pause, those campaigning against this monster must stay on the attack, until TOTAL has no choice but to fix their mess and leave, for good.

February 28, 2022

Will the populist wave crash over South Africa?

Church Square Pretoria, South Africa. Image credit Vladimir Varfolomeev via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0

Church Square Pretoria, South Africa. Image credit Vladimir Varfolomeev via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0 Twenty-eight years in, South Africa���s democratic order is in a bad place. Warning signs are to be found everywhere one looks. Several years after Jacob Zuma���s kleptocratic presidency, the state remains mired in corruption and mismanagement and is failing to reverse a catastrophic decline in basic services and infrastructure. Its security apparatus, deeply penetrated by criminal and seditious elements, seems powerless in the face of growing political violence and gangsterism. Populist parties are gaining ground, while demagogic, anti-constitutional voices increasingly dominate social media and fuel a new wave of xenophobic violence. Polls show collapsing support for democracy and growing receptiveness to authoritarian forms of government.

All of these morbid symptoms are well chronicled in a now daily stream of commentary issuing earnest warnings and dire prognostications about the fate of our democracy. These concerns are made far more acute by the gloomy international backdrop against which they are set. According to a growing consensus among political scientists, the world is in the midst of a ���third wave of autocratization��� ushered in by the 2008 financial crisis. That crisis definitively concluded the long expansive phase of democratization that had begun in the 1970s. Since then, fewer and fewer countries have seen any improvement in the health of their democratic institutions, while the number of places experiencing democratic ���backsliding��� has shot up.

Democracy���s retreat is conterminous with the globe-spanning rise of right-wing populism. Populists now control the government in numerous countries of the Global South, including major economies such as Brazil, India, the Philippines, and Turkey. In most cases, they assumed power through free and fair elections. But they���ve wasted little time in turning on and undermining those democratic freedoms once in office. Coups and full-blown dictatorships have been rare in the current authoritarian wave���its modal form has been the hollowing out of democratic institutions from the inside by incumbent governments. Populists have also claimed power in a handful of OECD countries, and have become a major electoral force in most others, often ending decades of duopolistic control by centrist parties.

The scope of these trends suggests that they are being propelled by deep structural forces. On the Left it is common to see populism as an expression of the intractable crises of the current, neoliberal stage of global capitalism. Neoliberalism���s most salient hallmarks have been soaring inequality and petering growth. It has given rise to both an unprecedented, decades-long stagnation in living standards at the bottom of the class ladder and a historically novel scale of wealth accumulation at the top. In this reading, populism is at root a reaction to the iniquities of our current Gilded Age, one that has assumed nativist forms due to the Left���s inability to offer meaningful alternatives to market-led globalization.

If it���s true that hard-edged economic forces are driving forward the populist tide then there is every reason to fear deeply for the fate of South African democracy. Even when measured against the subpar averages of the neoliberal era, post-Apartheid South Africa���s economic record has been exceedingly dire. Growth over the last decade has been negative in per capita terms. Inequality still registers higher than any other large economy. So does unemployment, by extraordinary margins. A jobless rate hovering for decades at levels normally only seen in the most severe recessions is the grimmest and most distinctive feature of South Africa���s economic malaise.

According to most analysts, the populist turn is already well underway here. Its main incarnation until now has been the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) led by Julius Malema. When the EFF launched in 2013, its ���Marxist-Leninist-Fanonian��� program combined appeals to class and ethnicity in roughly equal measure. Since then, class issues have gradually fallen off in its agenda, while the racial identities it invokes have grown narrower and more chauvinistic, bounded by anti-Indian and now anti-foreign vitriol. It increasingly converges with the populist movement that gestated within the ANC during Jacob Zuma���s tenure, now organized under the banner of ���Radical Economic Transformation��� (RET).

The ���Radical Economic Transformation��� faction�� also garbs itself in the symbolism of the Left, but its true nature is plain to see: it represents the most voraciously corrupt elements of the ANC, intent on reviving the Zuma-model of statecraft in which the fiscus is treated as a giant slush fund for the accumulation of ���tenderpreneurs.��� In the course of the last year, the RET faction lost several key battles in its fight with the group aligned to the ANC���s current president, Cyril Ramaphosa. But its continued vitality, and capacity for disruption, were demonstrated last July when it unleashed several days of chaos on the country following Zuma���s arrest for contempt of court.

Last November���s local government elections, in which support for the ANC sunk to its lowest levels yet, saw the sprouting of smaller new populist formations and ethnic parties. Notable among them is ActionSA, led by former Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba. Mashaba is a self-made businessman and an open admirer of Donald Trump.�� He first took office in 2016 as a member of the center-right Democratic Alliance (DA), the dominant white party, but split from it three years later, after it veered into culture-war politics and began purging most of its black leadership. In 2020 he formed ActionSA around a more conventional right-populist platform of anti-corruption and strident xenophobia. That message proved popular in November, winning the party an average of 16.1% in the wards that it contested in Johannesburg.

With South Africa���s economic and social crises magnifying each year, and with the populist tide sweeping forward unabated around the world, even in places of far less economic distress, it���s not hard to see why so many analysts feel that���s it���s only a matter of time before South Africa succumbs to an authoritarian movement promising order amidst the chaos.

Populism there and hereBut as Adam Prezworski reminds us in a recent book on the global crisis of democracy, structural pressures emanating from the world system are always refracted through national political contexts. The populist wave has not been monolithic but has comprised distinct variants of populism, rooted in different social bases and developing along distinct political trajectories. It���s not clear that any of these provide a clear signposting of where South Africa is headed.

Take Northern Atlantic countries for example. Populist successes there have plainly been connected to economic polarization. Plenty of micro-level evidence links growing populist support to trade shocks and deindustrialization. But these forces have been at work for decades. We could not understand why the response to them took the form it did, when it did, without looking at the transformation of political institutions, in particular the declining vitality of party democracy and the crisis of representation to which it has given rise.

The last several decades have seen the decline and hollowing out of mass-based political parties, on both sides of the spectrum but particularly the Left. Membership rolls have shrunk, participation has grown more fleeting and electoral turnout has diminished. Affiliated civic organizations, such as social clubs, newspapers, mutual aid societies, and, crucially, trade unions, have withered���part of a broader decline in associational life that extends down to the neighborhood and community level, leaving Western societies far more atomized. This has produced a deep ���void��� where once a dense thicket of institutions mediated the relationship between states and individuals.

These trends are themselves closely linked to the way that neoliberal globalization attenuated democratic life by cordoning off large areas of economic policy behind technocratic control. Social democratic parties collaborated fully in this process, which lent momentum to ���Brahminization������their parting of ways with the working class and re-orientation to highly educated urban professionals. It���s no surprise that populists, who���ve harnessed the anger stoked by a detached and unrepresentative political elite, have made their largest gains in blue-collar towns and rural areas, particularly those most devastated by globalization.

It���s striking to consider how different the dynamics of mass politics have been in post-Apartheid South Africa. If one measures it from the high-water mark of popular mobilization following the downfall of Apartheid, one would of course detect clear signs of decline in the vibrancy of civil and political organizations. But no ���void��� has ever yawned at the center of our political space. Where one might have been, the ANC has continued to loom large.

Indeed, even as its own electoral support has slowly declined, the ANC���s membership rolls have ballooned. Between 2002 and 2007 total membership climbed from 400,000 to 1.2 million and has since crept higher. Some fraction of these are ghost members or passive clients, added to the rolls to inflate the delegate power of one or another faction. But even accounting for these distortions the numbers suggest a vast expansion of the ANC���s reach. And that reach doesn���t end at the boundaries of the party. The trade unions and civil society bodies in its orbit may have ceased to be organs of grassroots democracy, but many continue to operate at some kind of mass scale, with fairly deep penetration into workplaces and communities.

While mass parties were disappearing from the scene in Europe, the ANC was fusing itself with the state and using its control over public employment and procurement to become a giant engine of class formation among the historically disadvantaged. It facilitated a vast lateral flow of rents through tenders and state contracts, creating a client business class. But it also ensured a steady flow of patronage downwards in the form of public jobs, smaller-scale tenders, and service delivery.

Local ANC branches, often supported by civil society groups like SANCO, have assumed a key brokerage role in this���interfacing with communities and managing the exchange of resources for the political support that undergirds the ANC���s hold on power. To some extent they also�� allow grievances to be conveyed upwards, facilitating some responsiveness of the state to local needs. So rather than the citizenry being entirely cut off from political life through the loss of mediating organizations, in South Africa there has been a proliferation of local points of (indirect) contact with the state, affording representation through clientelist arrangements.

The situation is changing – fiscal constraints and factionalization are throwing the party-state into crisis and eroding the ANC���s support, but these are still nascent trends. It���s thus no surprise that the dominant expressions of populism that we���ve so far seen have emerged not in the vacuum of an emptied political space, but from within the dominant party. The EFF and RET are often likened to right-wing populisms abroad because of their authoritarian, nationalistic and increasingly xenophobic tendencies. But beyond identifying a few common traits these analogies tend not to be especially helpful. The EFF and RET are distinctive beasts occupying a very unique political niche.

If we���re concerned primarily with assessing their prospects, then two key points of distinction are worth highlighting. The first is that the two are offshoots of the governing party, the latter still formally a part of it. After Malema���s split from the ANC, he managed initially to maneuver his new party into a very strategic position: able to claim a provenance in the Congress movement with all the symbolic benefits that entail, but independent enough to avoid association with its dismal record in power. The EFF sought to cast itself in the traditional role of the ANC Youth League, which Malema once led, as the radical conscience of its mother body. That position has now been lost. Driven by the sheer venality of its leadership, the EFF has re-enmeshed itself into the patronage networks of the party-state and started to openly align with the RET faction. The two are increasingly seen by commentators, and likely by the electorate, as manifestations of the same social essence.

The ties of both of these formations to the party-state will naturally limit the extent to which they are able to capitalize on anti-political and anti-elite sentiment. Outsidership has been an essential ingredient of the success of populist movements abroad, even when led by bona fide elites like Trump or career politicians like Modi. They���ve almost universally put anti-corruption and demands to ���drain the swamp��� at the center of their platforms. Neither the EFF nor RET will have successful recourse to the same tactics. Indeed, both are already themselves tainted���quite accurately���with a stigma of corruption and this probably goes far in explaining their inability, so far, to muster broad public support beyond a militant core.

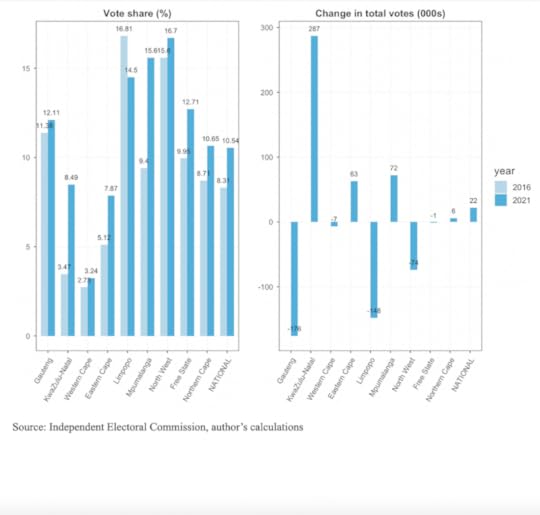

Table 1: The EFF���s growth in 2021 was largely due to the post-July fallout in KZN.

Table 1: The EFF���s growth in 2021 was largely due to the post-July fallout in KZN.The EFF grew extremely rapidly in its early days, and has shown a consistent capacity for impressive street-level mobilization, but has been stagnating at the polls for the last several years. The 10.5 % it netted in local government elections last year, a 2% bump from five years prior, is a poor result given a context favorable to populist messaging. Its growth in 2021 came overwhelmingly from KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province, where it benefitted���along with all other opposition parties���from the ANC���s hemorrhaging support in the wake of the July unrest (Table 1). In Gauteng and other provinces, it proved as susceptible as other major parties to collapsing turnout, which reflects poorly on its ability to capture anti-political sentiments.

Leaders of the RET faction, for their part, appear to be broadly disliked by the general public. Zuma���s approval rating when he left office was 25% (net -48%). Suspended ANC Secretary-General Ace Magashule, the second most high profile RET figure, has an approval rating of around 11% while Malema���s is 26%. Compare this with Ramaphosa, whose approval rating has fluctuated between 60 and 80%.

The second thing that distinguishes these groups from populist authoritarians abroad is the enmity they face from dominant sections of capital. Populism has not generally been the preferred choice for most large-scale capitalists, but neither has it been viewed as any kind of first-order threat. As typified in Trump���s tax breaks, populists in government have generally shown a willingness to offset potentially harmful protectionist policies with other kinds of giveaways to big business. In some cases, like Modi���s India, the relationship between the two has been deeply congenial from the start.

That won���t be the case for the EFF or RET. Both have made opposition to so-called ���white monopoly capital��� a defining part of their agenda. Whether it���s one they would actually stick to in power is a different question. They are in the end oligarchic movements, dominated by elites whose ability to extract rents from the state will ultimately depend on there being some measure of economic stability, which will deter any inclination to tamper with property rights. Still, a return to the untrammeled looting of state resources is not an agenda they are likely to divert from, and that means there will be no easy accommodation between them and large-scale capital.

In this sense, the EFF and RET are radical movements, even if there���s nothing progressive about them. They are a threat to dominant economic interests. Unfortunately, for them, this means they will confront the same challenges as other radical movements. In addition to facing powerful counter-mobilization from big business, they will have to contend with the latter���s structural power, stemming from its control over investment and unemployment. Parties that don���t kowtow to ���business confidence��� risk being branded as economic wreckers, which makes it far harder for them to appeal to middle-ground voters. In this way, capitalist opposition will not only constrain what RET populists are able to do with power, but their ability to lay hold of it in the first place.

The limits of middle-class populismPerhaps a better place to look for precedents in trying to gauge populism���s local prospects is South Africa���s BRICS partners, Brazil and India. The populist turn in those countries has taken a very different form to the West. Neoliberalism shaped the broader context in which it unfolded. However, the sociologist Patrick Heller argues that the proximate causes of the realignments that brought Bolsanaro and Modi to power have more to do with the ways that previous governments deviated from orthodox neoliberalism.

The Workers Party (PT) government in Brazil (2002-2018) and Indian National Congress (INC) (2004-2014) both blended neoliberal macroeconomic fundamentals with elements of welfarism and efforts to expand citizenship rights to marginalized constituencies. In India, this took the shape of a series of rights-based laws enshrining, access to information, basic education and, most important from a redistributive standpoint, the right to 100 days of paid public employment for every rural household. The PT���s flagship piece of welfare legislation was the famous Bolsa Familia program of conditional cash transfers. But, in fact, its most effective weapon against inequality was the progressive increases in the minimum wage, which rose by 75% between 2003 and 2013. Coupled with a favorable global environment, these demand-boosting policies helped to unleash rapid growth and elevate a large section of the poor into the lower rungs of the middle classes.

According to Heller, the eventual result of this was a furious political backlash from elites and the more established middle classes. This was animated by fear of intensified competition for traditionally hoarded jobs and opportunities and also by resentment at the breakdown of status hierarchies. Elites for their part resisted social policies for conventional reasons���their tendency to drain fiscal resources and weaken market dependence. The joining of these reactionary impulses produced what Heller calls ���retrenchment populism��� characterized by attacks on welfare and right-based legislation, but also by efforts to repress civil society and confine marginalized groups.

Recent data on voting patterns from Piketty���s World Inequality Lab seems to bear out this argument. It shows that the poor in Brazil largely remained loyal to the PT, while the party’s electoral decline was driven by the rapid desertion of voters in the top half and the top 10% of the income distribution. In India, the data reflect Modi���s success at consolidating the BJP���s bases among the wealthy and upper castes ahead of his 2014 victory. But it also reflects a sudden swing towards the BJP of a significant segment of the lower castes, won largely on the basis of appeals to religious conservativism charged with anti-Muslim bigotry. Bolsonaro achieved a similar result at a smaller scale in Brazil, garnering a beachhead of poorer voters through an alliance with conservative evangelical churches.

There are tempting comparisons to be made between ANC policy and welfare-neoliberalism of the PT and INC. The ANC also combined extensive liberalization and macroeconomic conservatism with social policies that, in comparative terms, have been generous and highly redistributive. However, the ANC never succeeded in unlocking the kind of rapid growth that Brazil and India achieved. Its social policies have had a more palliative quality���they���ve worked to temper the extremes of South African inequality without providing a strong springboard for middle class advancement. Consequently, resentment towards social entitlements for the poor has not been a lightning rod of middle-class politicization in the ways it has in other ���emerging economies.���

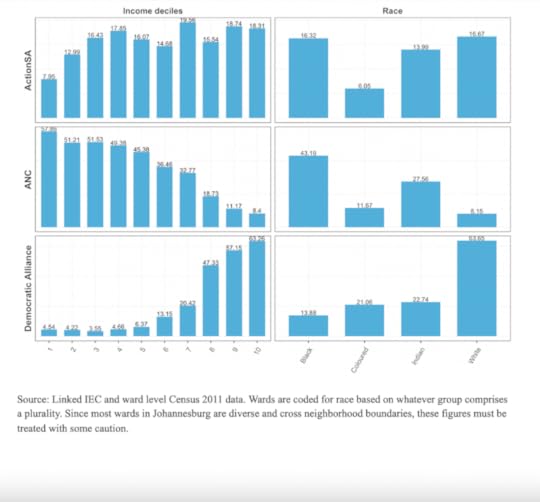

Nevertheless, there are signs of fairly deep middle-class discontent coalescing around other issues that are potential pressure points for populist agitation. Corruption is a key one, extreme crime rates are another. And although usually associated with working class communities, anti-immigrant sentiment appears to have gained a good deal of cross-class resonance. These are all core issues around which Mashaba’s ActionSA mounted its highly successful first campaign last November. Ward-level data suggests that Mashaba managed to appeal to an impressively diverse constituency, with ActionSA voters fairly evenly spread across suburbs and townships (Table 2).

Table 2: ActionSA���s populist message drew diverse support in Johannesburg.

Table 2: ActionSA���s populist message drew diverse support in Johannesburg.Despite these early successes, Mashaba and other aspiring populists will face major challenges in assembling the same kind of coalition that has powered authoritarian populisms elsewhere in the Global South. The first hurdle they face is that their potential middle-class base, which is small to begin with, is heavily segmented by racial divisions which were only deepened in these latest elections. Notwithstanding Mashaba���s small inroads, the DA���s pivot to color-blind, culture-war liberalism allowed it to recoup earlier losses and maintain its dominance of the white vote. Coloured voters defected in large numbers from the party, but largely to their own race-based parties.

It���s not really clear what strategy a party like ActionSA might muster for surmounting the deep racial loyalties of the middle-class electorate. It was virulent Hindu nationalism that yoked together Modi���s middle-class coalition across regional and caste lines, providing him not only�� voting fodder, but also disciplined cadres. Bolsonaro similarly draws his most fanatical, street-fighting battalions from chauvinistic, military-worshiping currents of nationalism with deep purchase in the middle class. There���s no equivalent force that could play the same role in South Africa���a pan-racial nationalism has never existed here.

Yet, when we subtract white, Indian and coloured voters, the South African middle class starts to look like a far flimsier foundation on which to try and build mass-based populism. What remains���the black middle class���is itself heavily divided. It comprises large parvenu layers that owe their class position to the party-state, to which they will have strong residual loyalties. Anti-corruptionism will have little traction among them. They���re likely to give far greater salience to continued opportunity hoarding by whites, but any pandering to those concerns will only alienate Mashaba from high-turnout suburbs.

What this means is that, for aspiring populists, plebeian votes will have to be a far larger part of their electoral math from the start. Anti-immigration and tough-on-crime stances will be powerful tools for making inroads into poor constituencies, and Mashaba has shown an ability to wield them effectively. Yet, while there is plenty of room for populist expansion among the poor, there will be strong limits to achieving the kind of majoritarian support that could subtend a full-blown ���populist turn.���

In urban areas, Mashaba���s more conservative brand of populism will be contesting for space with the ethno-nationalist, class-inflected messaging of the EFF. Its growth potential will be closely governed by the pace of decomposition in ANC support. While clearly in decline, the latter remains overwhelmingly the dominant force within poor communities. Party realignment within the working class looks set to be a protracted process.

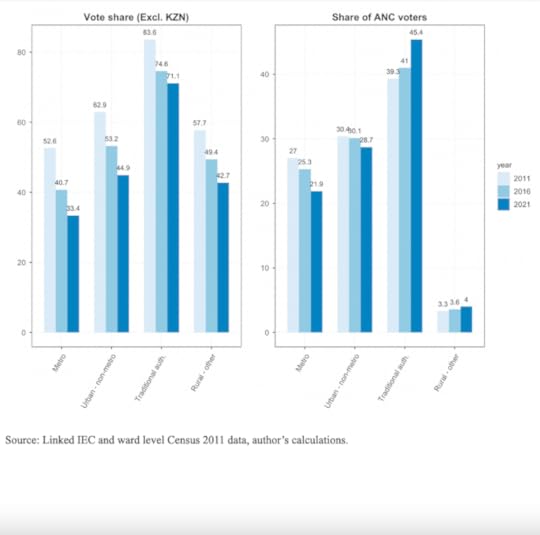

In the countryside, the dilemmas for new parties are magnified. The vast majority of the rural population lives under traditional authorities, which were originally the colonial state���s instruments of indirect rule. Today they���re a somewhat mixed bag: some abide by certain principles of consultative democracy while others, perhaps most, remain firmly in the colonial mold of concentrated patriarchal authority. For whatever reason, they���ve retained far greater legitimacy than other spheres of government (Table 3). Because they facilitate access to mining rights and influence the voting behavior of their ���subjects,��� they���ve become important cogs in the ANC���s patronage machinery, helping to secure its hold over the rural population in exchange for a share of the mineral rents and supportive legislation. Excluding KZN, where the party lost considerable ground to another ethnic formation, ANC support in 2021 held up far better in traditional areas than other parts of the country, declining at half the rate it did in large metros (Table 4).

Table 3: Traditional Authorities have retained far greater legitimacy than other spheres of govt.

Table 3: Traditional Authorities have retained far greater legitimacy than other spheres of govt.Bypassing chiefly influence and re-tooling a populist message to directly appeal to rural constituents will be a significant challenge for new parties. It���s one that already seems to have deterred the EFF. Consistent with their open reversion to a politics of the belly, the party resorted to bribing a notoriously violent and corrupt Xhosa chief ahead of last year���s elections, and bragging about it on their social media.

Table 4: The slow ruralization of the ANC. A parcelized polity

Table 4: The slow ruralization of the ANC. A parcelized polity In short, the dilemma facing populists, and indeed all political newcomers, is that the South African polity is parcelized by deep, cross-cutting cleavages. These have been to some extent obscured by the ANC���s expansive coalition, but will come to the fore again as that coalition fragments.

Three cleavages in particular have been highlighted in this analysis. The first and most primordial are racial and ethnic divisions. Two-and-a-half decades of formal equality has sadly done little to erode their salience. They present the most immediate challenge to parties trying to establish a base in the more diverse urban middle classes, but may come to assume wider relevance as the bonds of the ANC���s encompassing nationalism start to wither.

Second, are the deep divides created by the party-state. The ANC���s ���cadre deployment��� and procurement policies have created huge supporting constituencies and undergirded the construction of sophisticated political machines with extensive reach into poorer communities. But, inevitably, they���ve also fomented intense opposition. The corruption associated with the party-state is a source of profound outrage spanning all socio-economic fault-lines and even cutting through the elite sphere. Large-scale capital views the ���tenderpreneurial��� business class as a pronounced threat to the integrity and partiality of the state.

Finally, there are the cleavages created by South Africa’s ���bifurcated state.��� These are cleavages of conscious design, originating in the colonial era but maintained and reinforced by the democratic state. The ANC���s efforts to shore up traditional authorities as little archipelagos of despotism are continuing today through two major pieces of legislation on the traditional court system, one recently passed, the other nearing enactment. Whether conscious or not, this has proven an effective electoral strategy, helping the party to secure its bases in the hinterlands as it loses its grip on the cities.

Of course these cleavages are not immutable. Political parties don���t simply reflect divisions in the society but help to shape and re-make them. In the longer term it���s not at all impossible that some new populist formation will manage to cobble together a majoritarian coalition that cuts across and starts to erode these various fault lines. But for now the populist turn in South Africa looks to be a splintered one.

A takeover of the ANC by RET or some other faction remains by far the most likely near-term route to populist government. Patrimonial groups have the structural dynamics on their side���the ruralization of the party increases its relative clout at national congresses, which may well allow it to reverse the setbacks recently experienced. An RET victory, however, would immediately send the ANC���s electoral support further south and could even occasion splits in the Tripartite Alliance. The party would have to assume power in coalition (perhaps with the EFF) or with a wafer-thin majority. Unlike Modi or Bolsonaro it would have no green light from big business for undermining democratic institutions, so any movement in that direction would trigger capital flight and economic collapse.

That would create a dangerous dynamic. It could radicalize RET, forcing them to try and rapidly subvert the constitutional order rather than chipping away at it as other populists have done. But they���d likely be doing so from a position of weakness, heading a divided movement and with low levels of public support. Their success is far from guaranteed.

On the other hand, fragmentation may mean stasis. The same deep political cleavages make it harder for parties to find common ground and form functioning coalitions���as we���ve already seen at the local level. Even if they could do so, none of them have a serious vision of how to lead South Africa out of the intersecting, mutually reinforcing crises in which it���s become embroiled. Ending the ANC���s unassailable electoral advantage might bring some welcome changes���like a roll back of the party-state���but it won���t in and of itself deliver the structural reforms needed to seriously address poverty and unemployment.

Those crises have the potential to force South Africa down a path towards democratic breakdown very different from the ones that other countries have followed. The most acute danger is that the country gets trapped in a downward spiral of cumulative causation, in which mounting social disorder and disinvestment feed off each other. StatsSA���s recent announcement of a 1.5% retraction in GDP following weeks of unrest in July already gives us a foretaste of that frightening scenario. Self-reinforcing dynamics of this kind call for bold public action to break the cycle and set the country on a new path. But it���s not clear where the agency for such action would come from.

As ever there is an alternative. The wider processes of realignment underway also create the potential for realignment on the Left. For the whole democratic period the socialist movement has been weakened by its own cleavages, which have divided an ���independent Left��� rooted in social movements and small radical parties, from an ANC-aligned ���official Left��� with a base in the unions and the Communist Party. The fracturing of the ANC���s coalition is making it possible for these two halves of the Left to find each other once again and instill new life into class struggle politics.

For the marriage to work, both partners will have to be prepared to make major changes. The independent left will have to move quickly past the sectarianism and movementism that have plagued it in its years of marginalization. It will have to learn to think in bold political terms. As William Shoki argues it will have to take a large leaf out of the populist book, eschewing old doctrines and crafting a message capable of relating to people���s immediate demands for political inclusion and material redress.

But, unlike other Left populists, it cannot afford to confuse the message with the movement. If it is to keep its sights on the big structural changes we need, then it has to also remain committed to reviving and scaling up mass organizations, particularly those rooted in the structural power of labor. For that to happen, the organizations of the ���official Left��� not only have to be reclaimed from the ANC, but also fundamentally reformed. Historic traditions of shop-floor democracy and social movement unionism provide models for how this might be done.

The Left may only have a very limited window in which to put class politics back onto a mass footing. As we should know all too well in this country, parties have ways of institutionalizing themselves and establishing durable bonds of loyalty within their support base. If the Left fails to secure a seat at the table as the ANC coalition gets carved up it may find itself excluded for a generation or more.

February 25, 2022

Silencing the past of Egyptian football

Egyptian fans celebrates in a street in Cairo after Egypt beat Cameroon in their African Cup of Nations quarter-final football match in Angola on January 25, 2010. Image credit Ahmed Abdel-fatah via Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Egyptian fans celebrates in a street in Cairo after Egypt beat Cameroon in their African Cup of Nations quarter-final football match in Angola on January 25, 2010. Image credit Ahmed Abdel-fatah via Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Nearly every day when I arrive for work at the New Cairo campus of the American University in Cairo, I walk through the Omar Mohsen Gate. This pedestrian security gate was named after an undergraduate economics major who died violently at a 2012 soccer match in Port Said between Egyptian Premier League teams Al Ahly and Al Masry. The tenth anniversary of that match passed earlier this month on February 1st. Egyptians appeared to have hardly noted it. If they did, they did not say or write much about it, and with good reason: four days later, their Pharaohs of Egypt would play against the T��ranga Lions of Senegal in the marquee final match of the 2021 Africa Cup of Nations in Cameroon. The tension and drama of the final did not disappoint, though the outcome left many Egyptians disappointed as much as it left many Senegalese���whose team had never won the AFCON title���elated.

Including Omar Mohsen, seventy-four people died, and 900 were injured on that February 2012 day in Port Said. In an unlikely upset, Al Masry defeated Al Ahly, the winningest team in Egyptian football history, 3-1. But as the final seconds of the match wound down, Al Masry fans invaded the pitch and began assaulting Al Ahly players with knives, clubs, and flares, chasing the players into their dressing room. They also attacked Al Ahly supporters in the stands. (These fanatical football supporters were known in Egypt as ���Ultras.���) The violence produced a mad rush to exit the stadium, but one of the gates near the Al Ahly section of the stadium was locked. People screamed from the pressure of the crowd, suffocating or getting crushed to death. One young man approached the gate from outside the stadium to help the besieged crowd. When he succeeded in breaking the lock from the outside, the crowd inside the stadium slammed open the heavy metal gate with such force that it fell on the young man and smashed him to death. Other Al Ahly fans were thrown to their deaths from the top of the stadium.

As the violence escalated, Egyptian security forces at the game stood by and smiled, apparently enjoying the spectacle. They did next to nothing to intervene. This, combined with the fact that so many fans were allowed to pass through stadium security screening with knives and clubs, quickly produced accusations that the Egyptian government was in on the plan to attack Al Ahly players and supporters. The largest finger pointed at the ���old regime��� of deposed President Hosni Mubarak. Perhaps an easy target by this point, a little over a year after the start of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, which saw Mubarak removed from power, many observers suspected the old regime of a last counter-revolutionary gasp by sowing disorder among people hungry for the return of order and stability. In the ensuing legal process, seventy-three people were arrested, and eleven of them were condemned to death. Another soccer match between Al Ahly���s Cairo rival, Zamalek, and Ismaily was canceled later that night after news of the deaths in Port Said reached Cairo. In the wake of this disaster, the Egyptian Football Association suspended play for the next two years.