Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 7

February 16, 2022

Danielle Allen ends her campaigns… or “How Institutions Insulate Themselves from Change”

This summer I did something radically out of character: I wrote a check – a political donation for the legal limit – to a candidate for elected office.

Like many Americans, I am skeptical of our nation’s electoral system. I tend to believe that American politics is so thoroughly dominated by money, by entrenched interests, by structural problems like gerrymandering and restricted access to the polls, that very little social and political change is possible through the voting booth. I believe this strongly enough that I published a book last year, Mistrust, making the case that many Americans would be better off trying to make change through activism or nonprofit organizations than through engaging directly in the political process.

This time, though, the candidate was Danielle Allen.

Danielle campaigning in a barn in Plainfield, MA.

I often introduced Danielle’s candidacy to friends by explaining simply that she’s the smartest person that I know. She’s a scholar of classical Greek political philosophy, who’s written books about ancient Athens, the US Declaration of Independence, and incredibly movingly, about her cousin’s experiences with incarceration and reentry from a drug conviction. She’s won all the academic plaudits one could hope for; a professorship at Harvard, a MacArthur fellowship, a stint at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, but she is driven by a desire to fix things. She’s chaired the board of one of America’s most prominent foundations, and she spent the first year of the pandemic running a task force building relationships between academics, policymakers, and experts to help best figure out how to tackle the social crisis. People like Danielle don’t usually run for political office, but they are exactly the people that I hope would run for political office. I was all in.

I was preparing to do something else radically out of character this Thursday. I was planning to go to the town hall in my hometown, Lanesborough, Massachusetts, and participate in the Democratic Party Caucus. I intended to nominate myself as a delegate to the Democratic Party Convention to make the case for Danielle Allen being included on the Democratic primary ballot. I expected to lose. Our town is very small and sends only two delegates to the convention. One of those delegates must be female. I felt pretty sure one of the established players in the local Democratic Party would self-nominate to support Maura Healey, but I wanted to be part of a movement to try to get Danielle on the ballot.

For more than a year, Danielle has been traveling across the Commonwealth, meeting small groups of voters and listening to the problems that people articulated; housing, transportation, the opiate epidemic. She’s responded with a series of detailed and rich policy papers that have been thus far, shaping the conversation about what might change in my home state.

But I’m not going tomorrow night because Danielle suddenly dropped out of the race. I was surprised. I’d spoken to her just a few days before and she told me her read on the situation. She told me that she didn’t expect to poll well against Healey, the front-runner based on her name recognition from her time as state Attorney General. The plan was to try and come in second in the caucuses and use the run up to the election to have a conversation about possible futures for the state.

And here’s the rub: the caucuses are winner takes all. In a race like this one where a well known candidate like Healey is likely to get the majority of votes in most Massachusetts’ towns, it’s incredibly difficult for an outsider candidate to turn up 15% of the delegates. If Massachusetts allowed each town to allocate delegates proportionally, it’s a fair fight, but in a race where majority rules, a popular candidate like Healey will knock everyone else out of the field. After two weeks of caucuses, Danielle’s advisors told her she had no path towards 15%. State Senator Sonia Chang-Diaz is likely to come to the same conclusion in the next week.

What this means, in practical terms, is that the Massachusetts governor’s race is likely over, less than a month after Healey declared her candidacy. Massachusetts is a safe democratic state. We occasionally elect moderate Republicans to the governorship, often after Democrats have run up social spending. But Charlie Baker, the relatively popular Republican governor, is not running for a third term and the Trump-endorsed Republican candidate is not very popular. The brutal battles over the future of the Republican party make it hard for Massachusetts Republicans to nominate the sort of candidate who could win statewide. And so, it is likely that the Massachusetts governor’s race has been settled this past weekend before even the Democratic primary occurs. Due to the structure of the town caucuses, Healey will likely emerge as the only candidate on the Democratic ballot, and the Democrats’ registration advantage makes the race itself a non-contest.

The irony for me in all of this is that Danielle is not just someone I admire; she’s a colleague I work with closely and who has greatly helped shape my thinking about civic participation. We talked (and argued) extensively in the lead up to my book Mistrust. While I believe that many institutions of American life are so broken and unfit for purpose that we might do better in seeking to radically change them than to make small fixes to them,

Danielle makes a compelling case that we cannot abandon our existing institutions instead, we need to examine them closely, think about their original intentions and motivations and help bend them back to purpose. Her book, Our Declaration, is an ambitious rereading of the Declaration of Independence, which finds within its text written in part by slaveholders, a compelling argument for equality of all Americans and in “the pursuit of happiness” a commitment to the continued hard work of building a healthy society together.

In honor of Danielle, I wrote in my book about radical institutionalists, people who believe that our best path to change comes from the hard work of forcing our existing institutions to work for all of the people. And yet, what are our institutions but a set of rules and procedures and processes, sometimes apparently arbitrary, but ultimately deeply significant. What’s the logic of the 15% rule in the Massachusetts caucus? Presumably the goal is to create a meaningful choice between serious candidates and to strip away those who’ve found little or no support. Yet Allen has has held events all across the Commonwealth, has raised more than a million dollars, has a well-staffed campaign and a pile of thoughtful political proposals, while Healey only officially entered the race less than a month ago.

There’s countless other structures in American democracy where a small tweak in the rules might lead to a radical change in outcomes. Advocates for ranked-choice voting point out that voters often pick a candidate who they feel is good enough but not their first choice so that they can prevent another candidate from winning. For instance, you might vote for a moderate Democrat because you want to prevent a Republican from taking the office. In ranked choice voting, you can vote for a more progressive candidate, rank the more moderate candidate second, and the Republican third and more accurately express your preference. Advocates for this system believe that candidates farther from the center and candidates from third parties would have a much better chance of electoral success if this form of voting was used.

The truth is it’s hard to get people to pay attention to these structural changes. Politics is more a game of individuals and narratives, but here’s where there’s a chance to bring these two together. The Massachusetts gubernatorial race would be a far better, more interesting, more civically engaged contest had Danielle Allen stayed in the race. Democrats would have had months to hear from Allen, Chang-Diaz, and Healey about rival visions for the Commonwealth, and different policy ideas would have been put forward.

Can we use the story of the first Black woman to run for governor of Massachusetts as a moment to pay attention to a structural issue that otherwise might go unnoticed? Can we look at the sad case of a gubernatorial election being settled months before anyone votes and conclude that it might be the appropriate time for a rule change?

Danielle has promised to focus her efforts on challenging access to the ballot in Masschusetts, telling audiences that the Massachusetts caucus system is structured to “push out qualified but nontraditional candidates and rob [voters] of a real choice on their ballot”. In a communication with supporters earlier today, she pointed out that Massachusetts’s rules on ballot access are way out of line with most other US states. In addition to winning caucuses in enough towns to generate 15% of delegates, a candidate needs to present 10,000 signatures to be present on the state-wide ballot. In California – a much larger state – a candidate can present 7,000 signatures, or $4000 and 100 signatures.

Institutions, above all, are meant to serve us all of us. That’s what Danielle Allen taught me. Here’s hoping her campaign, which ended far too soon, might teach us something about how we need to change and transform Massachusetts institutions.

The post Danielle Allen ends her campaigns… or “How Institutions Insulate Themselves from Change” appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

February 3, 2022

My pandemic coping strategy: interviewing.

As we head into the third year of the pandemic, everyone I know is missing something. Live music. Reliable child care. The simple joy of working from a coffee shop, of casual contact with strangers.

My family and I are not untouched by COVID, though we’ve been incredibly lucky. I am deeply grateful to have a job that allows me to work remotely when I’m not teaching in the classroom, and a safety net that includes affordable healthcare if I do get sick.

But I’m missing something too. Initially, I thought it was travel – a major ingredient in my life that’s been almost entirely absent. But I don’t miss airplanes, racing for flights, dicey hotel rooms or living out of a suitcase. What I do miss is surprise. Not major, life-changing surprises, but the surprise of turning a corner in an unfamiliar city and seeing something unexpected. The surprise of ordering dinner in a language you don’t really speak and being served something you didn’t actually intend. The surprise of meeting a new colleague or catching up with an old and dear one and having a conversation go somewhere you hadn’t imagined.

These conversations take time. Being masked together in an office tends to limit interactions to the purely pragmatic: Could you please help me with this? Let me convey this information to you. What I miss are the discursive conversations that happen waiting for the train, or sitting on the floor outside the conference room waiting for the next session. I miss being surprised by what friends are working on, thinking about, obsessed with.

What’s helped is podcasting. Not podcasts – I’m sick of the voices and cadences of even my favorite serendipity brokers, wonderful folks like Roman Mars and Avery Truffelman, and I long for a future where I’m excited to hear from them again. No, I’m getting my juice from interviewing people for Reimagining the Internet, the podcast Mike Sugarman and I launched last year for the Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure.

Reimagining the Internet was initially intended to be a set of short (20 minute) episodes in which I asked internet luminaries for their thoughts on fixing the various problems we currently experience on the internet and the broader digital public sphere. Almost immediately, the guests steered the show in other directions, towards questions of whether computing is an inherently extractive industry, or towards the value of the principled stance of refusing to fix unfair and unjust systems and working instead for their abolition.

As Mike has taken his reins as producer, he’s challenged my preconceptions as well, bringing the idea of digital public infrastructure into realms like music streaming services, and introducing me to brilliant people not on my radar. The conversations that produce these episodes have grown from twenty minutes to an hour, and Mike struggles to edit them down to a listenable length.

Late last year, I interviewed Fred Turner, a Stanford historian who’s written two of the most influential books about the origins of the internet, From Counterculture to Cyberculture and The Democratic Surround. His most recent book was a surprise to me: a collection of photographs and essays called Seeing Silicon Valley, co-authored with Mary Beth Meehan. Turner sees the oft-celebrated, long-idealized Silicon Valley as where the fraying of America is perhaps most apparent, the unbridgeable gaps in wealth and power between the founders of and investors in big tech firms, and the people who do the invisible work around these firms of cleaning the bathrooms and preparing cafeteria meals.

The surprise in the conversation came not from learning that a security guard working full-time at Facebook lives in a garden shed without plumbing – I’ve spent enough time in Silicon Valley (and in America as a whole) to understand how inequality can manifest so profoundly. It came from Fred’s diagnosis of the current state of American society. Fred believes we are torn between an impulse towards individual success and towards a desire for community, and since the Vietnam War which split Americans along lines of class, wealthier Americans have opted almost entirely for individual success over collective welfare. But Fred sees the roots further back: in the Puritan idea of predestination. In a world where culture has preordained that some are saved and some are damned, evidence of ones divine status manifests in wealth, a trend Turner sees unfolding in Silicon Valley today.

But as much as old friends like Fred Turner have surprised me, I’ve been even more surprised from people I’m meeting through the podcast. Early in the show’s run, a listener suggested that we pay attention to questions of how caste discrimination was shaping the contemporary internet. We invited Thenmozhi Soundararajan, aka Dalit Diva, to join us and explain how caste has become a critical issue in global technology circles.

Soundararajan explained the idea of “digital brahmanism” to us, the idea that patterns of caste oppression get replicated both in technologies that permit harassment of oppressed castes and within tech companies that are only starting to consider racial and religious diversity, and have not worked to understand why caste diversity may be important to track as well. While we’ve seen encouraging indicators like Alphabet Workers Union demanding caste be added as a protected category for the workers they seek to represent, Soundararajan is not ready to declare any US tech companies “caste competent” at present.

My biggest surprise was the equation Soundararajan challenged me to consider: the balance between discomfort and death. “Discomfort doesn’t have to be the stop of where our interventions can be, because the reality is, is that for that dominant-caste person I deeply understand why it’s uncomfortable, but what’s uncomfortable to them could be a death sentence, or a physical attack for someone who’s caste oppressed. They’re actually uniquely in a position to intervene on their family as distasteful as it would be to them because they aren’t going to be the recipient of atrocity the way that I might be, or as someone else who’s caste oppressed.”

Our conversation with Dalit Diva made clear to Mike and me how important it is that we interview people whose perspective on the internet comes from standing in a sharply different place than our own. Of the episodes to be released soon, I’m most looking forward to my conversation with Dr. Jonathan Ong, my colleague in UMass Communication, who studies dis/misinformation through the lens of troll farms and online influence operations in The Philippines.

So yes, I know that responding to COVID by starting a podcast is roughly as original as baking sourdough bread or posting Wordle scores. Still, it’s done a better job satisfying my need for surprise than any other coping strategy I’ve found, and I hope perhaps some of these conversations can surprise you as well.

Some other recent favorites:

Kevin Driscoll on the early roots of the social web in Minitel and bulletin board systems

Heather Ford on the weird ways in which Wikipedia has become the agreed-on arbiter of our contemporary reality.

Tracy Chou of Block Party on making the internet safer for minoritized users through collective action.

And a closing plug – if you’re enjoying Reimagining the Internet, that’s probably because Mike Sugarman is an amazing producer. He’s building a portfolio of amazing podcasts at the intersection of academe and contemporary issues, working to make scholarly debates and questions interesting and accessible for wide audiences. If that’s something you think you might like to do, you should give him a call.

The post My pandemic coping strategy: interviewing. appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 7, 2021

Hope and Joy

My great aunt Jean carried a huge plastic tote bag as her purse. On each side of the bag were photos of eight of her grandchildren, surrounding a photo of a bottle of dish soap on one side, and of laundry detergent on the other side. “See?” she’d say, “They’re my pride and joy!” (Get it? Jean would check to be sure you got it.)

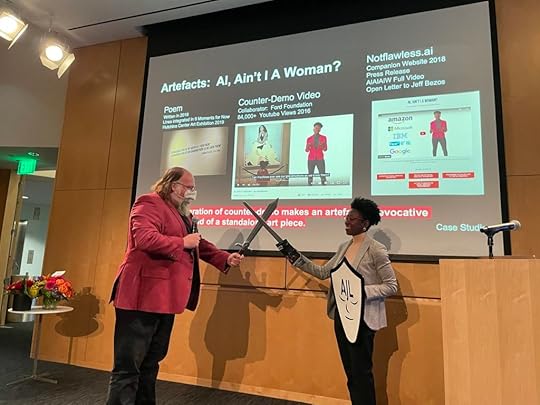

This cheap, plastic sword is one of my most prized possessions. It has five signatures on it, the five students I’ve awarded PhDs to for their work at Center for Civic Media at the MIT Media Lab.

It’s part of a tradition that I started as a joke. As Nathan Matias was preparing for his PhD defense, I saw a photo of Finnish PhD students being awarded top hats and swords to recognize their achievement as defenders of the truth. I decided it would be nice to have a similar tradition at MIT, but felt that perhaps students would need to earn those swords. So I appeared at Nathan’s PhD defense with two plastic swords. When the committee met to evaluate his dissertation defense, I asked all committee members to sign the sword. I then presented him with it and attacked him with my own sword… to his great surprise!

He defeated me in single combat and started the Center for Civic Media tradition that a PhD defense should be a literal defense. Erhardt Graeff took the tradition to the next level, scripting a battle with me ala The Princess Bride, in which we both began our sparring match left-handed and switched to our dominant hands. Jia Zhang opted out of the tradition in a distinctive way. Upon being presented with her sword, she simply stabbed me in the ribs with it, ending the match.

After I left MIT in 2020, it wasn’t clear what we should do with the tradition. Joy Buolamwini and Alexis Hope, both defending this season, suggested that the tradition might need to alter to recognize the fact that A) we are in a different stage of our work as a lab, and B) it’s not necessarily fun to have a 300 pound man charge at you with a plastic sword in front of friends and family on one of the most stressful days of your life. We’ve now adapted the ritual for a post-MIT context. The defending student is presented with her sword, she and I bow to one another, cross swords, tap each other on the shoulder, and hug. That’s what Dr. Joy Buolamwini did last night at the end of her brilliant defense.

Joy’s work has gotten a great deal of attention through extensive news coverage and a documentary, The Coded Gaze, that builds on her research on algorithmic bias in computer vision systems to examine the broader space of ways in which biases can be built into algorithmic systems. It would have been pretty easy for Joy to have built a dissertation purely around that work begun while she was a Master’s student, but is still generating new research papers, congressional hearings, and numerous follow on audit studies. Instead, she did something different and very brave. Her dissertation examined the idea of an evocative audit.

An evocative audit is designed to complement an algorithmic audit. An algorithmic audit is conducted scientifically, dispassionately, and carefully, and evaluates the ways in which an algorithmic system succeeds or fails in different test cases. Joy’s work with Timnit Gebru, analyzing computer vision systems to demonstrate that they failed disproportionately often on black women’s faces is a classic algorithmic audit, and algorithmic auditing has now become an important and growing field as we seek to understand the power of algorithms in our lives and hold them responsible.

But the reason Joy’s algorithmic audit is so well known is the evocative audit she paired it with. Joy’s most famous demonstration, a counter demo that she calls it, is one in which she sits in front of a computer vision system that sees a lighter skin woman’s face perfectly, but fails to recognize her face. When Joy puts on a featureless, white mask, the system recognizes her immediately. This failure and the emotions it generates is the heart of the evocative audit. Unlike the algorithmic audit, it is not dispassionate or scientific. It has an N of one, making it hard to generalize from, but that one is an individual who is affected by the system in profound and emotional ways.

The evocative audit draws on traditions of black, feminist scholarship to challenge the idea that dispassionate rationality is the only way to interrogate these powerful systems. In Joy’s work, the dispassionate, rational algorithmic audit is strengthened and complimented by an artistic intervention that shows why the systems are so important and so powerful. Joy would already have been heading off to a brilliant career as an activist (and I dare to hope, at some point, as an academic) based on her algorithm and auditing work, but the self-reflection she carries out in her dissertation work is truly extraordinary. I think it’s going give us a new set of categories for understanding the work that has to be done publicly to understand why audits matter so much to individuals and how the numbers and statistics behind these audits can be connected to real human lives.

Joy’s defense comes a few weeks after another brilliant defense coming out of Center for Civic Media. Alexis Hope’s work also began during her Master’s student years. Along with Catherine D’Ignazio and a large and passionate set of collaborators, she organized the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” Hackathon, bringing the visibility of the MIT Media Lab to a set of techno-social issues that rarely get considered in a technological context. Alexis’s work built from a personal narrative much as Joyce built from the personal narrative of her invisibility in the face of machine vision systems. Alexis traces her interest in the breast pump to a conversation with Catherine D’Ignazio where Catherine talked about the frustrating and dehumanizing experience of using a machine that is fundamentally unchanged in its designed since it came out of the barn for milking cows. Alexis helped organize and lead four hackathons over the course of her academic career at MIT focused on different aspects of maternal and women’s health.

As she moved through the process of designing these interventions, her project of self-reflection and criticality stands as an example for anyone who hopes to innovate towards more just futures. Alexis reflected on the first breast pump hackathon, which was enormously successful in attracting press and sponsor attention, and concluded that it had failed in one critical way. The breast pumps designed at the hackathon move to the market as products, but those products cost between $500 and a thousand dollars, putting them out of reach of the people who most desperately needed a redesigned breast pump, low income workers who did not have parental leave and who had to return to work soon after giving birth. Alexis and her team recognized that the team they had assembled, while more gender diverse than most hackathon teams, was neither racially nor socio-economically diverse.

As Alexis went through the hard work of building a team to hack breast pumps for low-income mothers, she found herself confronting the reality that she and her colleagues had to do a great deal of work around anti-racism training and understanding their own biases before creating spaces that were open to participants of different backgrounds. Much as Joy’s dissertation reflected on the lessons learned in communicating these audits through personal experience, Alexis’s dissertation reflected on the intense and hard work necessary to create accessible and inclusive spaces to make real collaboration between people from different backgrounds.

The work of these two remarkable women has given me my own chance for self-reflection at an odd inflection point in my career. During the pandemic, I have left one institution for another and found myself welcomed as someone experienced and established in my field, which comes as something of a surprise to me. I have always thought of myself as an enfant terrible, an untrained scholar coming from the outside to disrupt existing systems. But I’m nearing 50 now. The beard I grew over the pandemic has come in bushy and gray. I have helped five students within the Center for Civic Media earn their doctorates and shepherded others through the process. There are six assistant professors at elite universities across the Northeast who’ve come out of my lab, and proudly, two of them are tenure track academics who like me, have not completed their terminal degrees. Somehow over the course of the pandemic, I have woken up and discovered that I have become a senior scholar, and I love it.

My aunt Jean had her pride and joy. These two remarkable young women are my Hope and Joy. I don’t know exactly how they will change the world going forward, but I have every confidence that their impact will be massive and positive. I do have a clearer sense for how their work will impact me. I understand now that my work is to help a next generation of thinkers understand that they have the power to transform the technological world for the better. My work at UMass centers on two key ideas. One is that we cannot limit ourselves to critiquing and then fixing broken technological systems. Instead, we must go further and imagine better systems that we could build in their place.

This is not a naked celebration of innovation for innovation’s sake, an embrace of disruption as a way of being. Instead, it is a recognition that begins from critique, looking carefully at the limitation and harms of technological systems, but daring to imagine not just tinkering with those systems and making them less harmful, but designing and building systems designed with entirely different intents: with the goal of making us better and stronger citizens and neighbors, with the goal of building technologies that do not calcify existing social injustices, but work to upend them. This project will certainly fail. But coming from a place of critique, it will be better positioned than existing technological systems to examine and wrestle with its own failures.

Second, I’m ready to dedicate this phase of my career to help and bring more people like Alexis and Joy through the academy and out into the world. UMass is making a bold investment in the field of public interest technology, a new field that seeks to help technologists have a positive impact on their communities by matching technological expertise with careful thinking about social change, to criticize, improve, and overturn unjust systems.

When I explain public interest technology to audiences, I fall back on the example of my friend, Sherrilyn Ifill, who runs the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, the nation’s leading civil rights law firm. Sherilyn brought her team to the Media Lab to visit with Joy, me and my student Chelsea Barabas. She came to hear to about bias in facial detection systems – Joy’s work – the problems of carceral technology – Chelsea’s work – and to have a broader conversation about the role of algorithms and racial justice. I asked Sherrilyn why it was worth her time to bring her entire team for a day to an academic laboratory when such pressing work around civil rights issues lay in front of them.

Sherilyn explained that if the NAACP LDF had been able to stop red-lining in the 1950s, she believed the racial wealth gap between black and white Americans would be almost non-existent as opposed to the eight to one gap that it is today. “The next red-lining is going to happen via algorithm,” Sherilyn told me confidently, “and we need to understand those algorithms.” Sherilyn’s right, she usually is.

Public interest technologists are people who understand technology deeply enough that they can work within an organization like the NAACP LDF and help those fierce and effective lawyers understand the technology well enough to change the battlefield around discriminatory algorithms. Inspiring and amazing women like Joy Buolamwini and Alexis Hope are the sort of public interest technologists I hope to help bring into the world. Specifically, the work both of these women have done is so inspiring, it’s calling hundreds of other people to this subject. We now have the interesting challenge of trying to figure out how to educate these students so that they can follow in the paths established by my Hope and Joy.

I thought it was sweet and somewhat cheesy whenever Aunt Jean would show me her totebag. I’m beginning to understand the sort of pride one can have for people whose futures you’ve helped to influence, but whose trajectory and success is theirs alone. Congratulations, Joy. Congratulations, Alexis. And congratulations to anyone inspired by their example to follow in their footsteps.

The post Hope and Joy appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 23, 2021

Microfinance and public shaming in Nigeria

I got an interesting email from a young Nigerian today alerting me to the problem of social shaming and microlending. He wanted me to promote his petition and so I did a little research. (This post was a Twitter thread, which I tried to share with the young man in question. He pointed out that Twitter is currently blocked in Nigeria, so I’m expanding this slightly and putting this on my blog so it can be better shared by him and others.)

App-based microlending is popular in Nigeria, both because banks generally require collateral for loans and because the bureaucracy involved with lending can be overwhelming. So there’s a flock of new lending sites springing up, like FairMoney. FairMoney reported lending out $93m USD in 2020 in amounts from $3-$1000. Interest rates ranged from 30-260% APR, against 15-20% APR for bank rates. In other words, these are payday loans with sometimes predatory terms, but they’re what people can access.

FairMoney may play hardball with high rates, but there’s another tactic that’s raising eyebrows – and inspiring petitions: public shaming. Fail to pay your loans with OKash, a rival to FairMoney, and the app begins sending notes to the contacts in your phone! OKash (made by the same Chinese company behind the Opera browser) has a clause in the terms of service that reads “In the event we cannot get in contact with you or your emergency contact, you also expressly authorise us to contact any and all persons in your contact list.” In other words, default on a loan and we tell your parents, your friends, your boss… OKash has raised eyebrows in Kenya, where there’s no financial regulatory structure to protect what seems like an obvious privacy violation.

These techniques have gone even further in Nigeria. Apps access your social media and post on your behalf. Collection agents, filling a daily quota of collections, call your friends late at night and tell them they are the “guarantors” of your loan. Some collection agents use background sounds like sirens to imply that they’re in a police car, coming to capture you.

What’s most fascinating to me about this is that this is the dark side of an idea popularized a few years ago: credit scoring via social networks. The theory: analyze enough customers and their social networks and you’ll detect who is creditworthy. This is one of those ideas that’s probably terrible even if it works – imagine getting rejected for a loan and told that your friends network predicts that you’ll be a bad borrower? How does one contest that decision? Ensure that the algorithm isn’t unfairly biased against certain groups of people? But proponents argue that the upside is that this form of credit check could open lending to billions of people who have phones, but don’t have existing credit histories.

Indeed, OKash explains its need for your personal information in terms of determining your eligibility for lending: “OKash will access your mobile device for the permission of (but not limited to )contacts, location,SMS,calendar and camera to estimate the suitable loan offer for you. It is a very important part of evaluation process.” But can you trust OKash with your data? “We promise that we will never disclose your personal information to third parties without your consent. (exempted late refund and service requirement).” Oh yeah, that little exemption…

I ask students always to think adversarially about tech and ethical issues. One of the most popular assignments is when I ask students to look at a tech they’re trying to improve and write a Black Mirror episode about it. Student projects often steer in a very different direction once they’ve had the chance to consider how their preferred tech can – and likely will – be abused. It’s not that hard to imagine data used to determine creditworthiness being used, instead, to threaten and harass customers who fail to pay up in a timely fashion. In some ways, it’s amazing that it hasn’t happened sooner in societies with poor consumer protection systems.

Fortunately, Nigerian authorities are starting to act, fining another lender, Soko Loans, for invasion of privacy. And we’re starting to see more traditional methods, like blacklists for repeat deadbeats.

Two takeaways from me: 1) Tech innovation is always going to run ahead of legislation, and that can mean terrible things for consumers. 2) When you hear an optimistic new idea for financial inclusion, imagine the worst way it can be weaponized and work to eliminate it.

The post Microfinance and public shaming in Nigeria appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 18, 2021

I read Facebook’s Widely Viewed Content Report. It’s really strange.

What content is popular on Facebook?

This is a surprisingly difficult – and very important – question to answer. Facebook is the most popular social network in the world, and is used by roughly 7 in 10 Americans, roughly half of whom visit the site multiple times a day. 36% of Americans report that they regularly read news on Facebook. This means that Facebook could be a powerful vector for sharing misinformation or extremism that readers interpret as news.

Journalist Kevin Roose began publishing a Twitter feed in July 2020 that showcased the 10 “top performing” links on Facebook as determined by Facebook’s Crowdtangle analytics tool. Most days, the “top performing” links come from right-wing commentators and provocateurs like Dan Bongino, Ben Shapiro, Fox News and others. This seems to contradict the popular narrative that Facebook is biased against conservatives and suggests, instead that conservatives – and particularly incendiary ones – thrive on the platform.

Facebook really doesn’t like this feed. A few weeks after Roose began the project, John Hegeman – the head of Facebook’s news feed – took to Twitter to explain that Roose was tracking “engagement” – the number of people who liked, commented on or shared a given story. A better way to understand popularity of stories on Facebook was “reach”, i.e., the number of feeds a story appeared in. Facebook’s reach statistics show that mainstream news content is far more common on Facebook than the far-right content Roose was featuring. In my personal favorite part of the Twitter thread (now deleted) Hegeman conceded that Roose came to reasonable conclusions given the data he had, and that Hegeman couldn’t share the data that illustrated his points, though Facebook was exploring making it public.

Well, now that data’s public. Sort of. A little bit of it. And it’s pretty interesting, though not always in the way Facebook may have meant it to be.

Facebook is now publishing a quarterly transparency report – the Widely Reviewed Content report – which includes some helpful high level information about what US Facebook users are seeing in their news feeds. It’s interesting to see that 57% of posts in news feeds come from the friends users have chosen to follow – arguably the core value proposition of Facebook. 19.3% come from Groups and 14.3% from Pages followed (brands, public figures, and content providers, like news outlets.) 9.5% is attributed to “unconnected posts” or “other” – I believe these are not ads (“sponsored posts” as opposed to “organic posts”, which Facebook is revealing in this report), but includes posts Facebook is recommending to users above and beyond the interests they’ve stated due to subscription to pages, groups or friend feeds. (“Content that did not come from friends, Pages people followed, or Groups that they were a part of, also referred to as unconnected posts, made up a relatively minor percentage of content views.”) Why am I harping on this? It will make more sense once we start looking at the top 20 domains section of the report.

Facebook’s report make the important point that most content encountered on the news feed is not “news”, in the sense of breaking news – usually, its friends updating each other on the cute thing their baby/dog/robot vacuum cleaner did. The top 20 domains represented in the Facebook data represent only 1.9% of the stories in Facebook feeds, and those associated with traditional news sites represent only 0.3%. So, news as traditionally thought of is an ingredient in the Facebook news feed, but not a big one.

So what’s in there? Well, Facebook gives us only the top twenty domains, and most of them aren’t super informative. YouTube is the top domain that appears in Facebook’s news feed… which tells us basically nothing. That could be a handful of wildly popular videos, the low hum of GenXers sharing music videos from the 1980s or boatloads of innocuous content intermingled with QAnon propaganda. 13 of the 20 domains shared by FB are essentially information free: Vimeo, Eventbrite, Google, Etsy, Google Docs, Linktree, Spotify, Tiktok, GoFundMe, Twitter, Amazon and MediaTenor, a GIF hosting site. So far we’ve learned that big web companies are popular and people share GIFs on Facebook.

What about the other seven? Five are mainstream news sites – ABC, NBC and CBS News, CNN and the UK Daily Mail. It’s interesting that Fox isn’t in there, and notable that the Daily Mail, a conservative leaning publication notorious for sensationalism and poor fact checking, ranks higher than all but one mainstream news outlet.

And then there’s the other two. Unicef captures the third spot, briefly leading me to believe that Facebook was emulating FC Barça before they lost their soul and providing the international agency with free publicity. Roose on the Facebook Top 10 feed suggests a different explanation – UNICEF posts routinely appear on Facebook COVID-19 info panels, likely driving a great deal of traffic to the site – here is an example of a popular post, the #3 URL on the Facebook newsfeed in Q2 2021.

But who the hell is playeralumniresources.com? They’re the #9 most common domain in the Facebook news feed, and their homepage is the #1 most common URL in Facebook’s set, with 87.2 million views. Well, they’re a speaking agency of former Green Bay Packers players, who are available to join you for a round of golf, a fishing expedition or to sign autographs. And while I personally would be willing to pay a good deal of money to catch walleye with William Henderson (#33, legendary Packers fullback and Superbowl champion), the popularity of this page suggests that there’s something wacky about this data set.

The obvious hypothesis is that Player Alumni Resources is buying a boatload of Facebook ads and perhaps either people are organically sharing those ads or FB is putting a thumb on the “unconnected post” feed to boost their results. Fortunately, Facebook has an archive of ads on the site, and we can see that Player Alumni Resources is a known Facebook advertiser. But they’re not running ads at this point, so we can’t get data on them. Did they run a shitload of ads last quarter? Dunno – I’d need to scrape and store Facebook Ad Library data to answer that question. At least we know that Player Alumni Resources is not likely generating the single most popular URL on Facebook through their organic reach – they’ve got 4109 followers of their Facebook page.

I repeated the same searches for popular URLs #2, #4 and #5, the universally well known Pure Hemp Shop, MyIncredibleRecipies.com and ReppnforChrist. (The latter sells stylish, pro-Jesus apparel.) The CBD seller and the t-shirt maker look like the Packers speakers bureau – they’re past Facebook advertisers, maintain very small FB pages and are not running ads. Nothing for the recipe site. (Should I have searched for myinediblerecipies?)

Unless there’s a data error here, I’m guessing that Player Alumni Resources shows up in your “suggested for you” part of your feed pretty damned often if Facebook knows you’re a Packers fan or from Wisconsin. (Or both, but the set of Wisconsonites who are not Packers fans is blissfully small.) What’s the suggested for you” feed? I liked an article on McSweeney’s once – probably the piece about the snake fight portion of the PhD defense – and I now get suggestions for McSweeney’s articles incessantly in my news feed. They aren’t marked as sponsored content, so they’re not ads, I guess? But they sure feel like ads.

What’s going on here? Dunno. And that’s my overall reaction to Facebook’s transparency report. It shares a few interesting figures that reinforce the narrative that Facebook is more about posts from friends and family than news. But it doesn’t share enough data that we can come to any meaningful conclusions. If the domain list included a thousand URLs, perhaps, we might be able to compare attention to a mainstream news site like CNN to a fringe newssite like the Dan Bongino podcast. But with only 20 domains – 13 of which should probably not appear in the set, as they’re generic to the point of meaninglessness – it’s very hard to know what’s going on.

This data exists, by the way. Facebook generated a set of shared URL data through data partnership Social Science One. That set includes URLs shared at least 100 times, and it is accessible only to a set of researchers who’ve applied for access through a process that’s been criticized as slow and ultimately unsatisfying, due to concerns about data quality.

I am genuinely glad that Facebook is releasing more data about what’s popular on their platform. I am also genuinely astonished that this is what Facebook produced for their first effort. The data is accompanied by a thoughtful “companion guide” that helps explain how the newsfeed algorithm works. Did no one think to offer some marginal notes on why FB released only 20 top domains and URLs? Why obscure advertisers somehow emerge as the most popular URLs on the platform? The cynical side of me reads this report as transparency theatre – a chance for FB to tell critics that they’re moving in the direction of transparency without releasing any of the data a researcher would need to answer a question like “Is extreme right-wing content disproportionately popular on Facebook?”

Earlier this year, my colleagues and I released a 65 page report written for funders who support research on the media ecosystem about access to data about the big social media platforms. I will spare you the long read and offer my personal executive summary (not necessarily endorsed by my coauthors): Stop fucking waiting for the platforms to give us data. They’re not going to give us data. We need to get our own data.

Creative researchers are finding ways to generate data sets that we cannot currently – and perhaps may not ever – get from social media platforms. Jason Baumgartner’s desperately under-resourced Pushshift.io has scraped a full archive of Reddit and has become indispensable for researchers of that platform. At least three groups are recruiting panels of Facebook users and asking users to donate their data so researchers can better understand what they’re seeing on Facebook. Facebook has responded to this effort by shutting down the accounts of one team of researchers in such a heavy-handed fashion that the acting director of the FTC’s consumer protection bureau felt compelled to weigh in.

Maybe the next quarterly report will share 100 URLs instead of 20. Maybe Facebook will explain that I somehow missed a wildly popular post about someone’s weekend golf game with placekicker Chris Jacke. But it’s frankly pathetic that, given the importance of these questions, researchers wait for these tiny snippets of information from behemoths like Facebook. It’s time for us to figure out how – respecting user privacy and research ethics – to get the data we need to understand what’s going on with these platforms.

Update: as folks are discussing the report and my analysis of this on Twitter, Kevin Roose has weighed in with theories about these oddly popular URLs. The most plausible explanation: they’re spam. Wonderfully, in one case, they’re spam that appears to be being posted by an account associated with Jaleel White, the actor who played Urkel on Family Matters.

Perhaps it’s admirably honest that Facebook is admitting its spam problems through this transparency report? Or perhaps we should be surprised – disturbed? – that a company with a trillion dollar valuation, releasing a report to document its transparency efforts, would make an unforced error of not filtering spam out of their site statistics?

I’m guessing the original version of this FB report may not remain up permanently – here’s a copy as of 6pm today on perma.cc just in case it’s cleaned up in the future.

The post I read Facebook’s Widely Viewed Content Report. It’s really strange. appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

July 2, 2021

Why Study Media Ecosystems?

A few years ago, friends involved with the Media Cloud project – notably Fernando Bermejo, Hal Roberts, Rahul Bhargava – and I began talking about the need for academic approaches to media studies that sought to understand effects well beyond a single medium like Twitter or Facebook. The Media Cloud project is a tool for understanding how dynamics of social media might influence coverage of ideas and issues in news media, so it’s unsurprising that this was an interest of ours. But we wanted to connect with other scholars who found it limiting to study phenomena in a single digital medium and wanted to focus on the broader media ecosystem.

We’ve held two conferences on media ecosystems now, the most recent organized by Fernando Bermejo and hosted at MIT just before the pandemic shut down the world. After the last conference, I felt like writing a manifesto of sorts, a plea that we build better tools and methods to understand phenomena that emerge across social media, traditional news, search engines and other features of the digital ecosystem. Invited to participate in a special issue of Information, Communication & Society by my friend Dan Mercea, I did so.

The argument behind this paper is pretty simple. In the 1930s, biologists began to talk about ecosystems as an object of study beyond individual organisms. That shift allowed us to identify and discuss patterns that aren’t as apparent studying individual species. We need a similar shift away from studies that focus primarily on behaviors on Twitter, Facebook or any specific subset of media and towards understanding social media, digital media, traditional news media and other discursive spaces as part of an interconnected media ecosystem. This ecosystem demands new methods and tools for study, some of which are being developed and some of which we need to begin creating.

I should have expected this to be a controversial paper – it fits the “Thoughts on How Everyone Else is Bad at Research” category of xkcd’s Types of Scientific Papers, which is bound to piss people off. I meant it to be a shout out to the scholars doing ambitious, cross-platform research, not a diss of people doing deep work on a single medium. Let’s just say that Reviewer 2 had a lot to say about the first draft.

Whether your reaction to my argument is “Well, duh!”, “Well, that’s bullshit” or “That’s interesting”, I hope you’ll give it a read. The link on the Taylor and Francis site will provide some limited number of free reads, but there’s a full-text pre-print available right here as well:

Why Study Media Ecosystems prepressDownloadThe post Why Study Media Ecosystems? appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

June 14, 2021

Recommendations from the road

Amy and I had about as gentle a pandemic as one could have. No one in our immediate family contracted COVID, we both were able to move our jobs online with no major hitches, and our time at home gave us great time with Drew, who has turned into a remarkably smart, sweet and lovely eleven year old.

But each evening around 6pm, I began to get restless. The proximate cause – I was sick of everything we had in the refrigerator and just wanted something different. On a deeper level, I was sick of being in the same place all the time, despite the fact that the place we were was, and is, a lovely and comfortable place to be.

Tulsa, OK

Tulsa, OKThis makes a certain amount of sense. For the last seventeen years, I’ve commuted to work in another city 150 miles away from my home, and I’ve travelled extensively, averaging 200 nights on the road a year. In a way, going cold turkey on travel was harder than cold turkey on alcohol – I never found a good substitute for the stimulation and joy I get from travel, while non-alcoholic beer and hop tea mean that I very rarely miss drinking booze.

Del Prado motel, Cuba, NM

Del Prado motel, Cuba, NMWhat got me through the spring semester was planning an epic road trip. For nineteen days and 6800 miles, Amy and I wandered from Massachusetts to the Grand Canyon, up through Utah to see friends in the Denver area, and back home on a final sprint through Nebraska, Iowa and the upper midwest. The miles of different landscapes were like a deep drink of cold water for my eyes – my mind and heart were filled in a way that I hadn’t felt for over a year. The places we went – Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde, Rocky Mountain National Park and others – and people we saw were wonderful, but the sheer experience of being in a different place, free to wander in any direction, was what filled me up.

Cadillac Ranch, Amarillo, TX

Cadillac Ranch, Amarillo, TX6800 miles is a lot of hours behind the wheel – about 140 hours over three weeks. While talking with Amy was the best in-car entertainment, we listened to some remarkable stories that I wanted to recommend here:

We tried to listen to audiobooks that reflected on the landscapes and places we were passing through. We spent a great deal of time in the Navajo nation and greatly enjoyed Code Talker by Chester Nez and Judith Avila. Nez was one of the 32 Navajo US Marines who designed an unbroken military code used throughout the US war in the Pacific. I’d heard the basics of the code talker story, but Nez’s memoir takes us from his childhood herding sheep and living in a shelter made of sticks, through his adolescence in brutal boarding schools and into the jungle heat of island by island combat. We alternated between laughing at Nez’s good nature (he may have been the only soldier to genuinely enjoy military cooking, as his boarding schools basically starved him) and the insane demands made of him and his fellow Navajo Marines, who were so indispensable as communications technicians that they were part of the landing party in five sequential island invasions. The pride Nez felt in using Navajo to serve his country, and the shameful way he was treated on his return (New Mexico didn’t allow Native Americans to vote until 1948) was stunning and sobering. Navajo Bridge, Marble Canyon, AZAmy and I are suckers for podcasts that tell long, immersive, complex stories. Passenger List is our current fave, a labyrinthine and complex story about a downed airliner, a young woman trying to find her brother, and the complex conspiracy in her way. But Passenger List is a serial, and sometimes you want something spooky, creepy, all-consuming and compressed into two hours – a movie, instead of a TV show.

Navajo Bridge, Marble Canyon, AZAmy and I are suckers for podcasts that tell long, immersive, complex stories. Passenger List is our current fave, a labyrinthine and complex story about a downed airliner, a young woman trying to find her brother, and the complex conspiracy in her way. But Passenger List is a serial, and sometimes you want something spooky, creepy, all-consuming and compressed into two hours – a movie, instead of a TV show.Shipworm bills itself as an audio movie, and it lives up to that ambition – you walk away from the experience satisfied in the same way you might from a fulfilling psychothriller. It’s the story of a lovely, small-town doctor who begins hearing a voice in his head that tells him to do… things. Strange, disturbing things. Like the best thrillers, what seems random and arbitrary early in the story fits neatly into the story as it develops. I came away feeling deeply manipulated by the authors, in the best possible way, and I fervently hope that we see the rise of the audio movie as a new podcasting format. Too many shows lurch on for week after week, dribbling out small bits of a large story – getting a fully-contained story in one massive bite is deeply satisfying.

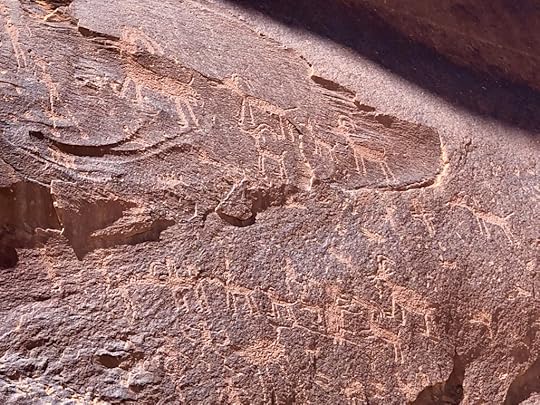

Petroglyphs, near Mexican Hat, UTI took some time off from my daily news habit (On the Media, The Daily, etc.) but spent some quality time with long-form audio journalism. The superstar in that category was American Rehab, an eight part investigative series from Reveal and the Center for Investigative Reporting. The series begins with the story of a sister who helped her brother find an affordable opioid rehabilitation program, only to discover that she’d signed him up for eighteen months of unpaid servitude, working up to 84 hours a week at dangerous jobs in exchange for three packs of cigarettes and “therapy” that mostly consisted of being screamed at by program administrators.

Petroglyphs, near Mexican Hat, UTI took some time off from my daily news habit (On the Media, The Daily, etc.) but spent some quality time with long-form audio journalism. The superstar in that category was American Rehab, an eight part investigative series from Reveal and the Center for Investigative Reporting. The series begins with the story of a sister who helped her brother find an affordable opioid rehabilitation program, only to discover that she’d signed him up for eighteen months of unpaid servitude, working up to 84 hours a week at dangerous jobs in exchange for three packs of cigarettes and “therapy” that mostly consisted of being screamed at by program administrators.Finding out that drug rehab programs are creating a shadow, unpaid labor force is fascinating enough, but there’s way more to American Rehab. Turns out that the many US firms that use unpaid work as a form of “therapy” trace their roots to Synanon, a fascinating 1950s-60s cult that used a form of “attack therapy” called The Game to crush the egos of participants and rebuild addicts as recovered citizens. Synanon had some real success in the early years before descending into criminality and cultishness – it spawned dozens of similar treatment programs, some of which continue today, using the discredited idea that hard, unpaid work can cure addiction.

The team behind American Rehab did years of thoughtful reporting to expose Cenikor, a particularly vile and abusive child of Synanon, and to document the vast size of the unpaid labor force of addicts in recovery. If anything, I wanted even more of the story, particularly examination of the idea that we know what actually works to treat people for opioid addiction (medication-assisted treatments like methadone and buprenorphine) but so often opt for “tough love” and abstinence approaches that have a dismal track record.

Aside from audio recommendations, some more general recommendations from three weeks on the road:

Prahbupada’s Palace of Gold – we spent hours reading the history of the Krishna Consciousness movement and the complex history of this intentional community in West Virginia, but none of that prepared us for the combination of an improbably beautiful palace on a rural farm and a community of lovely, sweet people dedicated to living their lives there.

Palace of Gold, New Vrindaban, WVRed Oak II. When his hometown of Red Oak, Missouri disappeared, Lowell Davis rebuilt it, building by building, creating a completely inauthentic ghost town out of bits of other rural ghost towns. That the town is perfectly preserved, inhabited, but wholly uncommercialized (you’re hard pressed to find anyone even to give a donation to) makes it a particularly surreal and wonderful experience.

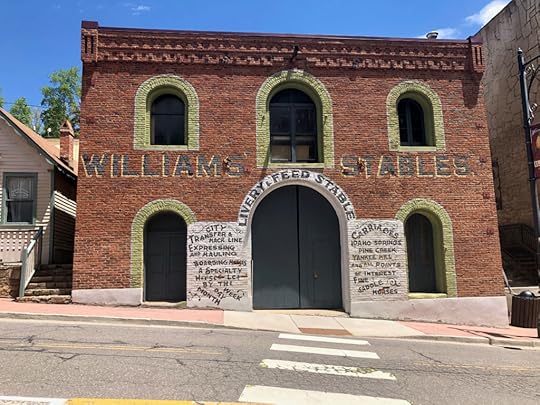

Palace of Gold, New Vrindaban, WVRed Oak II. When his hometown of Red Oak, Missouri disappeared, Lowell Davis rebuilt it, building by building, creating a completely inauthentic ghost town out of bits of other rural ghost towns. That the town is perfectly preserved, inhabited, but wholly uncommercialized (you’re hard pressed to find anyone even to give a donation to) makes it a particularly surreal and wonderful experience. Red Oak II, Carthage, MOGilpin County Museum. There’s two old mining towns side by side, about an hour’s drive out of Denver. Black Hawk is a miniature Las Vegas, modern glass and stucco, and thoroughly avoidable. Central City is an architectural gem, filled with masterpieces from the 1870s gold rush. The Gilpin County historical society maintains two museums, both excellent, and worth many hours of your time. I’ve never seen a small town do a better job of preserving its heritage and I am wishing every community – including those I live in – had museums like these ones.

Red Oak II, Carthage, MOGilpin County Museum. There’s two old mining towns side by side, about an hour’s drive out of Denver. Black Hawk is a miniature Las Vegas, modern glass and stucco, and thoroughly avoidable. Central City is an architectural gem, filled with masterpieces from the 1870s gold rush. The Gilpin County historical society maintains two museums, both excellent, and worth many hours of your time. I’ve never seen a small town do a better job of preserving its heritage and I am wishing every community – including those I live in – had museums like these ones. Central City, ColoradoThe biscuits and gravy at Bob Evans. I am very glad and very sad in equal measure that Bob Evans does not have any locations in western MA.Grillin’ Dave-Style. I ate a lot of BBQ on this trip, but the best, believe it or not, was in Zanesville, Ohio. Dave’s brisket is amazing, and his beans, loaded with burned bits of brisket, may turn Zanesville into a frequent stop on trips through the midwest. Please hold whatever comments you have about real BBQ not existing outside of North Carolina/Texas/Oklahoma/Kansas City etc. – this was freaking delicious and I want more now.

Central City, ColoradoThe biscuits and gravy at Bob Evans. I am very glad and very sad in equal measure that Bob Evans does not have any locations in western MA.Grillin’ Dave-Style. I ate a lot of BBQ on this trip, but the best, believe it or not, was in Zanesville, Ohio. Dave’s brisket is amazing, and his beans, loaded with burned bits of brisket, may turn Zanesville into a frequent stop on trips through the midwest. Please hold whatever comments you have about real BBQ not existing outside of North Carolina/Texas/Oklahoma/Kansas City etc. – this was freaking delicious and I want more now.Random photos from our trip on my instagram.

The post Recommendations from the road appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

April 15, 2021

A milestone I never expected

I got the good news today that I have been granted tenure at the University of Massachusetts. This is very good news, as the tenure process is inherently a gamble: if you begin the tenure process and are not offered tenure, you’re generally not permitted to remain at a university, and I have just gotten started at UMass. Better yet, I really like it here and plan to stay for a long time.

But tenure is a complicated thing for virtually all academics, and perhaps especially so for me. It’s increasingly clear that academe is splitting into two tracks: tenure, where scholars have a good deal of security and stability once they’ve become associate professors, and adjunct status, where academic work is poorly paid, insecure and highly contingent. I am glad to have joined a university where a combination of faculty and union advocacy limit the use of adjuncts and where much of the faculty is able to pursue tenure, but it’s not a system that seems broadly sustainable or fair.

I recognize also that tenure can often calcify structures of power – notably sexism and white supremacy – that desperately need to change. The same structure that offers academic freedom and the ability to research and speak without fear of losing one’s job also gives guarantees of employment that make it harder for academic departments to reflect the diversity of their student body and the nation that they serve. At the worst, tenure sometimes protects faculty from the consequences of their unacceptable behavior, notably sexual harassment, which remains significant within academe. In feeling intense gratitude at being awarded tenure, I am also deeply aware of the complicated nature of practice and its implications.

For me, personally, tenure was never an aspiration. I came to academe later in life, and through the back door. I dropped out of a Masters program in 1994 to work in the early dot.com economy, moved from a startup company (Tripod.com) to starting up a nonprofit organization to work on technology education in the developing world (geekcorps.org). When that NGO folded and I came to the Berkman Center (now Berkman Klein Center) at Harvard, I intended to spend a year thinking about my future, not nine years building another NGO (globalvoices.org) and a media analysis platform (mediacloud.org). In retrospect, I should have used my time at Harvard to earn a PhD. In my defense, it wasn’t entirely clear what I should have sought a PhD in, as my interests spanned a wide range of academic topics.

Berkman and Harvard took a chance on me, giving me ample opportunity to discover that I enjoyed research not only on the topics I was most passionate about, but on a wide variety of unanswered questions about how media attention, censorship and constraints on online speech work. I got an other astounding chance from MIT, who not only allowed me to teach with only a BA, but to advise doctoral students and award PhDs. Those PhD students now teach at Cornell, Olin College and Northeastern, and students who are finishing their doctorates this year are already doing groundbreaking and widely recognized research. I hope that MIT feels like the success of those students validates the bet they made that I could advise doctoral candidates.

When I was recruited to UMass, it wasn’t at all clear to me that I would be hired to the tenure track. Tenure is so closely tied to the PhD and to the conventional academic pathway that I assumed I would be hired into a position similar to the one I held at MIT: Professor of the Practice, an academic status that allow experienced practitioners to teach, but does not confer the full rights and privileges of “academic” faculty. (At MIT, I taught Master and doctoral students and led research grants, but was not a member of the faculty.) Deans John Hird and Laura Haas surprised me by telling me that I was being recruited as tenure-track faculty and they expected me to file my tenure case as part of the hiring process. Again, I am incredibly grateful for an academic institution taking a chance, and I hope to reward UMass’s gamble with a long career at this excellent university.

I want to thoroughly acknowledge the many privileges that have allowed me to take this unconventional path. I had significant financial security after leaving a startup that allowed me to take advantage of a fellowship at Harvard and pursue years of research where my costs frequently weren’t covered by the grants I was able to receive. It’s not a coincidence that I’m a white male, the most overrepresented category in academe, and where my status as an unconventional academic may have been more controversial if I were a woman or a BIPOC person. I got incredibly lucky in that my academic interests aligned with a field experiencing significant growth: had I discovered my passion for English literature after a successful professional career, it’s unlikely that academic institutions would have been so welcoming to an uncredentialed scholar.

So while I feel intense gratitude in being awarded tenure, it’s a different feeling for me than it is for many young academics for whom years of hard work as PhD candidates and as assistant professors has been rewarded with a promise of security and stability. Gratitude, surprise and a sense of how unpredictable one’s path through life can be are my emotions, rather than the sense of hard work and a job well done that I hope my peers who’ve completed a more conventional path feel.

That said, I want to make the case that we need more people who’ve taken the unconventional path towards professorship, not fewer. While the contemporary doctorate descends from the church-issued “licentia docendi” (license to teach), until the 20th century, most teaching faculty in the US and Europe did not have doctoral degrees. The research doctorate came from the German academic system and the first PhD was offered in the US at Yale in 1861. The spread of the degree as a qualification for teaching has been gradual, and in some European countries, many distinguished faculty and scholars do not hold PhDs. In other words, while most teaching faculty in the US these days have PhDs, that’s a fairly recent development, and it’s far from universal in academia globally.

The PhD is excellent preparation for academic research and teaching: the students I’ve worked with as an advisor have used their PhD research to learn the hard work of developing and testing hypothesis, collecting, cleaning and analyzing data, writing cleanly and citing work that supports and challenges their work. The PhD can be a great way to develop these skills, but it’s not the only way. I’ve sharpened my writing by writing books and popular press articles as well as academic ones, and I push my students to write for non-academic audiences as well as academic ones so that their work can be widely understood. Some of the best data scientists I know are not academics, but journalists, industry professionals and others whose work requires them to ask hard questions about data and to be rigorous and honest about the results.

Much of my work these days focuses on the idea of technology in the public interest: the emerging field of people who think critically and carefully about technology and how it can be used for social change and public benefit. This is a field that will develop best from both inside and outside academia. We need to learn from people researching bias in AI from within the lab, but also from people working in tech companies and government about what actually works in leveraging technology for social change. We need pathways for people who discover in their professional work that they want to research problems deeply and rigorously from within an academic framework and to share what they discover along the way with generations of young scholars. We’ve gotten increasingly good at understanding that not all PhDs will – or should – become professors, and I hope we can move towards a realization that not all professors will have – or should have? – PhDs.

I am profoundly grateful for my membership in academe, a club to which I do not have the formal qualifications for admission, but which has nevertheless provided a warm welcome. I am eternally grateful for all the individuals and institutions who’ve taken a gamble on me in the past, and I hope to reward their confidence in the future. And I hope I can both recognize the struggle and hard work that so many of my peers have gone through to earn tenure via more conventional routes while reminding people inside and outside academia that there’s more than one path to a lifetime of teaching, learning, research and service.

At university events like graduation, you’ll see the faculty line up in procession with colorful academic hoods that reflect the universities they’ve gone to and the degrees they’ve earned. Next time you watch one of those processions, look for the rare odd one out, the scholar wearing the basic black baccalaureate robe. We’re there too, just as proud of our work learning and teaching and of the paths that have brought us here.

The post A milestone I never expected appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

February 26, 2021

The Year of Going Nowhere

Today is the anniversary of the day I started paying attention to the coronavirus pandemic in earnest. We’re about to see a wave of these posts of people reflecting on a year in isolation – I had planned to write one in early March. But on reviewing my email, I see that on February 26, my colleague at the MIT Media Lab Dr. Kevin Esvelt sent out a long email that began “Raising a topic considered fringe is inherently socially awkward, and can even be considered taboo when it’s associated with unequal health and mortality risks.” He noted that he had initially predicted that the novel coronavirus was likely to cause between a thousand and ten million deaths worldwide, and that recent news forced him to raise the upper bounds on his estimate to forty million deaths.

Kevin’s caution in sending the email out was reasonable – in late February 2020, the pandemic was something that had hit China hard, but hadn’t been reported as a cause of death in the US. In retrospect, we know that there was an ongoing outbreak in Seattle, Washington, but the first death from COVID-19 wasn’t announced until February 29. It’s remarkable to think of how quickly Kevin’s caution went from being a possible overreaction to a topic on the fringe of most Americans’ attention to being a prescient view of the new normal.

Having received Kevin’s email and watching the news closely, I still got on a plane to Seattle on Monday, March 2, 2020 to give a speech at a conference. I remember the faint signs that the world was about to change: a statue of a dog outside a store near Pike’s Place Market was wearing a surgical mask, though none of the humans were. We were ordered not to hug or shake hands at the conference, so we awkwardly bumped elbows.

On Monday, March 9, 2020, I began cancelling travel, changing an important meeting in NYC to a videoconference and dropping out of a speaking engagement because I didn’t want to spend a day in a conference room with strangers. The organized was initially pissed with me, and then, by a day before the conference, seemed to realize that something was going on that was entirely beyond her control.

There was incredible uncertainty about what to do in early March: should we stop traveling, start working from home? With no guidance from federal or state governments on what precautions to take, employers became the deciders and they watched each other closely. When Microsoft announced that a few of its employees had tested positive and ordered everyone else to work from home, it started a sea change in the tech industry. MIT waited for Stanford, UWashington and Harvard to stop in person classes, then ordered us to start teaching remotely as well. My last in-person class was on March 11 – half of the class had already decided to participate remotely, and we felt a frisson of danger when we got together for a class picture to celebrate our last class together. That was the last time I taught at MIT and the last time I taught in a classroom.

I remember feeling incredibly grateful once MIT had ordered us not to travel and to work and teach from home. I was having a hard time feeling safe in Boston. I stopped using the T and walked or drove to campus. But life was a series of calculations: do I step into a crowded restaurant? Hug a friend? It feels weird to have your employer decide that it’s time to take something like a pandemic seriously, but that’s how it happened for me. I started the process of calculating risk a year ago today, and was happy to outsource much of that calculation to MIT and others a few weeks later.

And now, for me and for most everyone else, it’s been the year of going nowhere. My photo stream is devoid of the wanders through city centers that animate my life and decorate the walls of my home. This year’s photos are close to home: Drew launching model rockets, catching fish and learning to shoot a bow and arrow; Amy punching holes in the ceiling and wiring new lights; the few, precious friends who’ve visited us outside and distantly.

It’s a year of growth rather than motion: my son gets taller, my beard gets longer. My gym muscles shrink, my core gets stronger with bench presses traded for yoga, done badly and slowly. There’s change – a new university, a new lab, a new book – but the photos tell a quieter story. Leaves sprout, darken from chartreuse to green, to red, yellow and brown, until everything’s replaced by endless white. The woodpile grows and shrinks. The dog find a new slipper to destroy and eviscerates it over the course of a month.

Late one night, email answered, papers edited, I was oddly bored. Amy asked me what I was doing that gave me joy. I thought for a long time about that question and didn’t answer her until later in the week. It’s not that my life is devoid of joy – my kid, my partner, students and colleagues over Zoom, a vast pile of board games. It’s that a massive, central source of joy in my life is the experience of getting off a plane or a train in an unfamiliar city, wandering aimlessly, drinking in unfamiliar sights and sounds. That finding an unexpectedly good doner kebab in a new town is satisfying in an entirely different way that eating the best meal in your favorite familiar restaurant. I miss exploring the world to a degree that I would have found almost unimaginable before this year.

It hasn’t been a bad year, this year of going nowhere. We are safe, untouched in our immediate bubble by the disease. We are employed, in school, connected to family and friends. I suspect, with distance, I will remember it as a surprisingly sweet break from life as usual, a time that forced us all to think about what’s essential and what’s optional, whether the way we have always done things is the way we should do things. We are lucky and blessed and privileged, and we are sad and tired and bereft. We are waiting to reemerge as the snows melt and the herds become vaccinated. We will someday get on planes again, perhaps with masks this time, and I will get lost in an unfamiliar city whose name I had only read about in books and it will fill me up in a way I cannot articulate.

We are a year in and it’s not over yet. We’re okay. We’re not okay. We will be okay.

The post The Year of Going Nowhere appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

February 18, 2021

Hey Twitter, I need it not to be 6ourbon 7ime

I quit drinking a bit more than three years ago. I wrestle with terms – I had a fairly easy time quitting, which makes me wonder whether “alcoholic” is the right word for me, but “problem drinker” certainly describes my experience. I liked drinking alcohol, and I had a hard time stopping once I started. I did things I regret when drunk, damaged relationships, mistreated friends and abused my body. I am proud of my sobriety and hope to stay on this path in perpetuity.

Unlike some people who stop drinking, I haven’t removed all the alcohol from my house. My partner has an occasional glass of wine and back when we could have friends come to visit, we’d have wine and beer around for guests. But there’s no bourbon in my house because that was my special poison. I got drunk on big cups full of diet pepsi and Jim Beam, sipped in front of the TV to relax at the end of the long day. Almost every day was a long day.

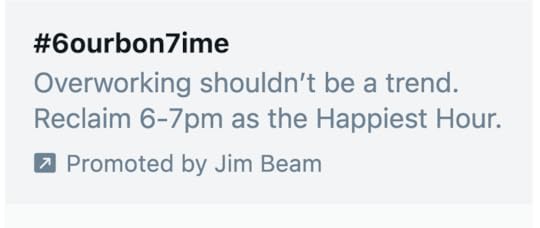

So this ad on Twitter is tough for me.

Put aside for the moment the whole question of whether it’s appropriate for Jim Beam to appropriate the language of self-care to promote their liquor. I don’t want to see this ad. It’s not good for me to see this ad. I would argue that it’s not even good for Jim Beam for me to see this ad – I am not the sort of responsible Jim Beam consumer the brand claims to be seeking out.

I block ads with Ghostery on Firefox, but Twitter’s ads come through. I’m okay with that – I would prefer a world where I could pay Twitter for their service, but I appreciate that Twitter makes it easy to block individual advertisers… and I block many of them. But this isn’t a conventional ad – it’s a promoted Trending Topic.

Several people have suggested that I might turn off the ad by disabling personalization – I’ve done so. The ad persists. How about blocking the specific advertiser? I did that too – it involves going specifically to Jim Beam’s profile page and blocking them. Not that much of a problem for me, but I can imagine people in recovery for whom that step would have been difficult and unpleasant. But it doesn’t actually remove the promoted trending topic – it’s still there when I reload Twitter after blocking Jim Beam.