Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 3

March 13, 2025

Freedom Interrupted: Electoral Interference

I’m at Attention: Freedom Interrupted, a conference at McGill University this week, an international conversation about information and democracy that brings together scholars, activists and policymakers from the US, Canada and around the world. It’s a timely conversation – the US and Canada seem to be descending into a trade war and Canadians are responding with understandable anger towards their southern neighbor. Conversations about foreign election interference – the topic proposed for the conversation six months ago – now seems like a subset of broader conversations about the future of information and democracy.

That’s not to say we’re not seeing old-fashioned election interference. Marcus Kolga of DIsinfowatch offers a chilling overview of Russian interference in Moldovan and Romanian elections. Russia directly paid hundreds of thousands of Moldovans to vote against a pro-EU candidate, and ran massive pro-Russian campaigns on Telegram. These were unsuccessful and the pro-EU candidate was re-elected.

But Russian disinfo did manage to spoil the first round of Romanian elections, Kolga tells us. Calvin Georgescu, an obscure fringe candidate, rose in prominence during the first round of the elections through a suspiciously successful TikTok campaign. There’s lots of evidence that Georgescu, who advocates ties between Romania and Russia, perhaps most compellingly the fact that investigators found $10 million dollars and a ticket to Moscow buried under his house. While Romania threw out results from the first round of the election, JD Vance spoke in favor of Georgescu, complaining that Romania was unfairly overturning results.

Russian disinfo is showing up in more developed nations as well, Kolga argues. AfD in Germany is carrying water for Russia, advocating for removal of sanctions against the nation and for Germany to end support for Ukraine. The technique of amplifying and supporting fringe parties is a common Russian tactic, he argues.

Mercator senior fellow, Felix Kartte notes that finding Russian propaganda used to involve complex forensic work. Now Russian propaganda is mainstreamed and peddled by the US president. Elon Musk is using his platform to share far-right propaganda regarding the German election. Our toolbox is still designed to study the 1.0, and we are instead dealing with broadcast propaganda, he warns.

Shirin Anlen from Witness connects issues like deepfakes and non consensual imagery with attacks on democracy. We’re still in the “prepare, don’t panic” stage of deepfakes, she suggests, but we are seeing some worrying indications. AI is being used to translate speeches into multiple dialects, letting a leader like Modi speak to multiple audiences at the same time. Also, deepfakes are being used to create entertaining memes, less than for fooling the electorate. But the specter of deepfakes makes it easier to accuse real information of being faked and runs the risk of making us doubt real audio and video evidence.

A question to the panel asks whether younger voters are more vulnerable to influence of people like Andrew Tate. Kartte notes that young people are co-creators of these narratives, not just consumers. The far right has mastered integrating political messaging with lifestyle codes and know better how to meet the emotional needs of young people than the left. Shirin notes that human rights no longer seems to trigger a response in young audiences – right-wing extremists seem better able to identify issues that resonate with these audiences.

A questioner from Colombia mentions that Russia is not the only country that interferes in overseas elections – American interference in Colombia is more subtle than Russian interference, but still problematic. How should we draw the line between politics and interference? Moderator Paul Wells references a referendum in Quebec in 1995 where Bill Clinton spoke about the importance of a unified Canada: “That was clear foreign election interference. The difference is that I liked it.” Kartte talks about the distinction between Russian propaganda media and state-supported media like Deutsche Welle – “it’s not like a law of physics, it’s a finer line”.

Another questioner points out that Canada is going to be facing a very brief electoral campaign – how do we “prebunk” narratives designed to undercut the election? Shirin notes Zelenskyy’s success in debunking a deepfake that announced a Ukrainian surrender – speed and clarity is key in this work.

The post Freedom Interrupted: Electoral Interference appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

March 12, 2025

He’s not a neoliberal, “He’s a thug” – Stiglitz on Trump, in Montreal

Joe Stiglitz is a bright guy. He won the Nobel for Economics in 2001 for his work on markets where information is asymmetric. He’s the former chief economist of the World Bank, the former chairman of the US council of economic advisers, and the author of tons of books. Tonight, he’s talking about his new book, The Road to Freedom: Economics and the Good Society, at a McGill University event in Montreal. (He and I are in town for a conference on media and democracy at McGill this week.)

(This is a liveblog. I’m going to get things wrong – feel free to let me know in the comments and I’ll fix things.)

He’s in conversation with Christopher Ragan, the founding director of the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill, and an accomplished macroeconomist. Ragan disclaims that he’s not going to give any questions about Donald Trump until the final question because Stiglitz’s book, and the questions it raises, precedes Trump’s presidency.

Stiglitz begins by explaining his understanding of neo-Liberal capitalism, which he believes has failed and needs to be superseded with progressive capitalism. Neo-liberal echoes back to 19th century liberalism, but hopes to do something slightly different: if you strip away regulations and created unregulated free markets, the economy would prosper. Related was the idea of trickle-down economics: if we had sufficient growth, everyone would eventually prosper.

Neo-liberalism was a reaction to the government interventions under FDR in the US to alleviate the Great Depression and the actions in Canada and Europe to create a robust welfare state. Stiglitz mentions Milton Friedman and Frederich Hayek as the dominant voices arguing that disassembling these state interventions would lead to widespread prosperity. Asked who is arguing for neoliberalism today, Stiglitz argues that most contemporary economists understand that markets often fail, particularly facing serious problems like climate change. The dominant school in macroeconomics in the US – the Freshwater school – uses models that hearten back to neoliberalism. The predilection, Stiglitz argues, is to find market solutions to problems and then to solve the problems that are created with neoliberal solutions.

The problems with neoliberalism include income inequality, the failure of markets with crises like the mortgage crisis of 2008, and the poor performance of markets in sectors like the American healthcare are sector. Americans spend 4-5x as much as Singapore, 2x of what France spends and gets much worse outcomes: “That’s the market… one factor is a large role of monopolies.” Stiglitz mentions the assassination of the CEO of United Healthcare and notes, “The frustration with US healthcare is universal”.

Ragan asks whether the problems with neoliberalism are specific to the United States, and Stiglitz wonders whether US universities have indoctrinated economists all over the world, turning them into neoliberals. He argues that the “Chicago boys” have thoroughly taken over Latin America, where figures like Javier Milei in Argentina, who is preaching the virtues of Hayek, despite the ways in which that economist’s theories have been disproven. He hails back to Adam Smith, who he says noted that market actors would conspire to rig markets rather than competing: “They persuaded themselves that markets are naturally competitive. But when you open up your eyes… it’s a cognitive dissonance I’ve never understood.”

Stiglitz’s book is titled as an obvious response to Hayek’s “The Road to Serfdom”. Stiglitz notes that classic neoliberal texts offered ideas of “freedom” as a freedom to exploit workers and markets. Friedman’s influential article on CEO’s maximizing shareholder value was basically a plea for CEOs to exploit workers, consumers and anyone else, in the hopes of maximizing profits… and in the process, social welfare. Stiglitz remembers a seminar he offered at Chicago, where Friedman confronted him afterwards – Stiglitz believed that Friedman became an ideolog around the idea of the value of unregulated markets. Stiglitz refers to Isaiah Berlin’s idea that freedom for the wolves is death for the sheep – one person’s freedom is another person’s oppression. A company’s right to pollute might lead to the unfreedom in which we suffer from pollution.

In a book written decades ago, Stiglitz tells us, John Rawls argues that you should think about public policy issues as if you didn’t know where in society you were going to end up. Once you’re actually in a society, you have a vested interest in protecting your social class. If we didn’t know what position in society we would play – if we had a “veil of ignorance” – we would make better decisions about social policy and public goods.

The USA is a great place to be born in the top 1% – preferably the top 0.001% – but a lousy place to be in the middle of the economic distribution, Stiglitz tells us. If you’re going to be born in the middle, Europe or Canada provide much better services and opportunity. When we consider trade offs that play one person’s freedom against another, the veil of ignorance helps us make wise decisions. Consider COVID-19 and mask mandates: almost any rational society would require vaccination, social distancing and masking in order to protect millions of citizens. “The freedom not to die, not to be hospitalized outweighs the freedom to not wear a mask.”

Ragan asks, “What is it about a neoliberal world that leads to income inequality?” Stiglitz notes that in absence of good regulation and income redistribution we see a natural tendency for greater market power, which means those who control the markets have enormous power. Classical economics believes that markets will squeeze out profits as firms compete: that’s clearly not the case with Amazon or Facebook. Instead, power concentrates.

Ragan and Stiglitz do a pretty good job of staying off contemporary politics until NAFTA comes up – Stiglitz was advising Clinton when the agreement was on the table, and raised concerns that trade with Mexico – essentially transferring low-skilled labor to that country in the form of importing cheaper goods – would lower US wages. For Clinton, the idea that economic growth would raise all boats, was an article of faith. (Ragan notes that Canadians thought that NAFTA was a pretty good idea until about two weeks ago. Stiglitz quips, “That’s because you believed in the rule of law. I’m an academic – I’m more cynical than that.”

Rather than the freedom to move jobs anywhere it’s cheapest, Stiglitz argues that we need a freedom of opportunity, a freedom for children to access education and healthcare. That means we need to reduce economic disparities within societies and between societies. “In the US, we have a meritocracy – at least it looks like a meritocracy. But your ability to go to Harvard, Columbia or other elite schools is highly dependent on your parent’s income.” These schools are “need blind”, but the high schools students attend reflect the economic inequalities of the communities people live within.

The economic system we live within is not a free market, Stiglitz explains: there’s countless rules that matter immensely, and those rules are set within political processes. The US Supreme Court interprets the first amendment to allow money to have unbridled political influence. When a state government was concerned about the inequalities of this system, hoping to equal campaign funds, the Supreme Court intervened and argued for the importance of economically unequal speech. “Consider this an advertisement for becoming the 51st state.”

The dysfunction in the US comes in part from market power over media. The information ecosystem is affected by who owns the media – including social media – and what regulations they are controlled by. Not long ago, Stiglitz reminds us, we had rules like the Fairness Doctrine, which required equality in representation of views. Having eliminated those rules, we now have nakedly partisan media like Fox News. “When you have a media that can be bought by wealthy media, the views of that group get amplified.” What results is not a town square, but an echo chamber for those at the very top.

In 1996, Stiglitz reminds us, the US passed the Communications Decency Act, which included section 230, which means social media has no liability for what they carry – he reminds us that there was no public discussion of this provision. This provision should have been discussed, he argues – “it means there is no accountability, no responsibility” for what’s on these platforms. “You have junk going in to the information ecosystem… to get rid of the pollution takes a lot of work!” It’s a public good to clean up this ecosystem, Stiglitz argues.

Ragan points out that there are significant free speech arguments that get raised by Stiglitz’s idea of “cleaning up” online speech. Stiglitz argues that we’ve never had entirely unrestrained speech: we prohibit incitement, child sexual abuse material. He suggests we might need to rethink the balance around online speech: perhaps we reconsider a “right to vitality”. (This is often talked about as “a right to reach” on social platforms.) “In the midst of a pandemic, telling people that vaccinations are dangerous is, itself, dangerous.”

An hour into a conversation, we’ve largely avoided mentions of Trump. But his last question from the stage asks whether Trump is a neoliberal – his emphasis on tariffs contradicts neoliberal doctrine.

Stiglitz is blunt: “He’s a thug.” He understands Trump more in terms of Russian oligarchs than traditional economics. Telling a story about a dinner with a Russian oligarch, he oligarch told him :”Trump is just a traditional Russian businessman.” Russian oligarchs don’t honor contracts, they don’t make ethical commitments. Understand Trump in those terms and he makes more sense.

Ragan asks whether Stiglitz is surprised at Trump’s approach towards allies like Canada, Panama and Denmark. “Some of this is bluffing: the Art of the Deal is about seeing what you can get.” Canada has an advantage that a major fraction of exports are natural resources. That means there’s a global market for those products. (Not electricity, I’d note…) There’s some rents around Canadian oil given pipelines to the US – Ragan notes that developing LNG will give Canada more independence in this sector. “One needs to think about how to impose pain on the US.”

Is there a way to look at the current moment through a lens of optimism? Stiglitz notes that we are still in democracies – a fragile one in the US – and that most people agree on the policies behind progressive capitalism. Even in the US, policies like high equality education and healthcare have broad support. Ragan says “You’re arguing that any rational society would agree with progressive capitalism – are we not a rational society?”

Stiglitz targets the media again. People keep hearing a narrative that tarifffs will make Americans rich again — it’s going to take a while for people’s lived experience to counter those narratives. He notes that Trump’s tax cuts for the wealthiest became deeply unpopular once people realized how few benefits they saw from those policies. The only downside, Ragan notes, is that we might need to wait months or years for people to see these harms unfold.

I was struck by a question Stiglitz took and his answer. The questioner asked him a) why he was speaking about his book in Montreal at this moment of tension between the US and Canada and b) about the chutzpah he was showing in critiquing Trumpian economics so directly. Stieglitz explained that a) this is what academics do – we go to conferences and share ideas and b) if you’re lucky enough to have tenure, you should use it to say provocative things, knowing you’re protected. I was happy to hear that, particularly at a moment where anyone from Columbia, where Joe is affiliated, has every reason to be gun-shy.

I disagree with some of Joe’s remarks near the end on restricting online speech and hope to have the chance tomorrow to persuade him that middleware is a better solution to speech problems than censorship.

The post He’s not a neoliberal, “He’s a thug” – Stiglitz on Trump, in Montreal appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

February 20, 2025

Liz Pelly at UMass: Spotify, the Mood Machine

The UMass Responsible Tech Coalition hosted journalist, editor and musician Liz Pelly to talk about her new book, “Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist”. She’s introduced by my friend and colleague Mike Sugarman, who has interviewed her for our podcast Reimagining the Internet, and followed Liz’s career in DIY music for years. Mike contextualizes Liz’s work at Silent Barn in Bushwick, Brooklyn, an independent music venue organized as a community-led space. Silent Barn was organized along many of the principles of Occupy, supported almost entirely by ticket sales and sadly closed in 2018… but Mike sees Silent Barn as a model for how the music industry could be designed differently, a question that Liz asks and answers within her new book.

Mike namechecks Nathan Schneider, a media scholar at UC Boulder whose work on online platforms warns of the risks of digital “feudalism” – we have little to no power over the spaces like Twitter or Facebook we interact within. This, in turn, might damage our democratic and participatory muscles. The solution is to get involved with community organizations where our input is real and impactful. With that in mind, Mike suggests that involvement in projects like Silent Barn can be a counterpoint to faceless systems like Spotify that entertain but disempower us

.

.

Liz began researching Spotify in 2016, but it took much longer for a book to emerge. In 2016, Liz was working as a freelance writer and tending bar and booking gigs for Silent Barn. Liz’s work writing about music for publications like the Boston Phoenix has been complemented by building the DIY music scene, hosting gigs and putting up touring musicians, giving her a skeptical perspective on the music industry.

In 2017, inspired in part by Astra Taylor’s work The People’s Platform, Liz began writing about consolidation and corporate power in internet culture spaces. She wasn’t a big Spotify user at the time, but became fascinated with the app as a pathway into understanding how corporate consolidation was changing music. She began writing about “backdoors” into Spotify playlists – her first piece on Spotify in 2017 asks about how music recommendations put certain artists and songs in front of users of the platform, and how the service’s “editorial voice” came into being.

Pelly’s book Mood Machine is “a 90,000 word answer to those questions”. Her sources behind the book were the people she met in her work with Silent Barn and led to dialog with music executives, artists, music writers and others with insights on Spotify’s weird journey from “a search bar for all music” to a world of algorithmically promoted AI music slush, recommendations based on payola and artist exploitation. The goal of the book is to debunk some of the myths of a platform like Spotify and to reveal the actual mechanisms at work behind the profitable service.

In particular, Pelly is interested in the myth of Spotify as a neutral meritocracy, a space in which the best work rises algorithmically to the top. The reality is more about arrogant billionaires overconfidently celebrating their machines and ignoring the social problems they leave behind. To tell this sometimes hidden history of Spotify, Pelly interviewed over 100 people, many of them artists affected by the rise of the platform. She offers this as a “pro-artist” work, noting that it’s strange to have to put yourself in the “pro-artist” camp. Swedish journalists, who covered the platform during its emergence, were also an important source.

So were internal documents from Spotify, including Slack conversations, sometimes shared from former employees. It’s a journalistic book, not an academic history, Pelly explains, and includes everyone from activists protesting against Spotify to shows the platform threw in Brooklyn, to founder Daniel Ek’s Twitter account and YouTube videos of Spotify execs talking about the platform at inception. The book brought her twice to Sweden, including a trip to Ek’s hometown, the Stockholm suburb of Rågsved, which houses a community music space much like the one Pelly lived at and helped run.

Pelly’s initial interest in Spotify focused on playlists and the notion of playlist creators as the new “gatekeepers” to music distribution. But over time, the focus shifted to labor movements: the ways in which the commodification of music by services like Spotify have changed the experience of being a musician. She notes the emergence of “ghost artists”, music commissioned at discount royalty rate from AIs or session musicians to create tracks for playlists for sleeping or studying. This connects to the power of algorithms in shaping what we pay attention to and hear… and what we pay for. Spotify thinks of itself as a “two sided marketplace” selling music to consumers and algorithmic promotion and advertising to musicians. In effect, services like Spotify end up emerging as the new bosses in the music industry, displacing music execs.

Reading from chapter 8 of the book, Pelly points out that listeners rarely get to see how much data the platform is collecting on them, except at year’s end with Spotify Unwrapped. The nature of the data visualization changes every year – one year, it focused on the “aura” of the music listeners encountered, working with a mystic to create colorful squares to represent the mood of the music. This vision of mass personalization turns music from a community and collective expression into a moment of personal expression: “make the music revolve around me”. What results, Pelly believes, is a deeply alienated way of appreciating music. You know what the machine thinks you like, but you don’t know why, and you can’t challenge it when it’s wrong. You’re sorted into a silo rather than encouraged to connect with the people building scenes and communities around musics.

Taja Cheek (who records as L’Rain) tells Pelly that we can no longer agree on a common view of history and facts, and that hyperpersonalization drives us into individual cultural silos as well, at the expense of the musicians creating this “content” in the first place. Pelly looks to musicians, not just businesspeople, as the people with possible solutions to Spotifycation of the music industry. American musicians cannot legally unionize – as independent artists, they would be considered a “cartel” – but musicians are starting to form solidarity organizations, protesting the financial injustices of streaming services. She looks at how public libraries are beginning to fund local streaming services, which provide access to local musicians who might not otherwise get carriage (and certainly not much revene) from huge networks like Spotify. What’s instructive about local, small-scale streaming services is not technological innovation, but the ways that communities can put forward alternative business models that are fairer to musicians and to listeners.

Pelly interviewed a librarian in Edmonton, Alberta, who launched a local digital music poject. That included conversations with local artists about the design of the network, including a conversation with fifty local musicians to help codesign the service. Another example of a social, not technical, hack is Catalytic Sounds, a co-op of 30 avant-jazz artists based around Chicago, where the $5 monthly subscription fee for streams of original music goes 50% to support the platform and 50% split between the 30 creators.

She closes with the last paragraph of the book (“not the last paragraph of the book, but the last paragraph I wrote, if that makes sense). The ineffability of music is at risk if we don’t protect both the musicians who create these works and our own emotions and choice.

The post Liz Pelly at UMass: Spotify, the Mood Machine appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

January 13, 2025

From WEIRD to Wide: my keynote at CSCW 2024 in Costa Rica

This past November, I had the privilege of offering the closing keynote at CSCW 2024 – the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing – in San Jose, Costa Rica. I’m a huge admirer of CSCW and the work presented there, though it was my first time in attendance. (I was hoping to go the previous year, but my paper was rejected… which is what’s great about blind peer review.)

This was the first time CSCW has been held in a Latin American country, and the conference organizers are two brilliant Latina scholars, Rosta Farzan and Claudia López. The opening keynote was given by Paola Ricaurte, an amazing Mexican scholar who is rethinking how AI systems could be built to empower communities, rather than extracting data from them. I wanted to make sure that my remarks celebrated the presence of the conference in the Global Majority world and built on Paola’s work, which has deeply influenced my thinking.

What follows is unlikely to be an exact rendering of what I said on stage – I improvise from notes when delivering talks – but is a pretty good summary of what I hoped to say.

From WEIRD to Wide: Global Views of the Quotidian Web

November 13, 2024

Three behavioral scientists at the University of British Columbia – Joseph Heinrich, Steven Heine and Ara Norenzayan – published a remarkable paper in 2010 titled “The Weirdest People in the World?” The paper observes that a huge percent of research in psychology and behavioral economics comes from studying a very specific population of people: undergraduates at North American universities. An analysis of top journals in six subfields of psychology revealed that 96% of findings came from countries with less than 12% of the world’s population… and from a specific and narrow subset of individuals within those countries.

The authors characterize the subjects of these research studies as WEIRD: Western, Educated, from Industrialized and Rich Democracies. The bulk of their argument looks at research studies on apparently “universal” phenomena, like the Müller-Lyer illusion. Designed by sociologist Franz Carl Müller-Lyle in 1889, many people have difficulty seeing these two lines as equal in length.

[image error]

But the tendency to see these lines as different in length is strongly culturally linked. Foragers and other people who spend a lot of time outside, like the San people of southwestern Africa, generally see the lines as the same size, which they are. Of populations studied in a comparative analysis, US university students ended up at the other end of the spectrum, estimating a 20% difference between line segments. The speculation is that the illusion relies on how perspective is represented in western art, and how we learn to see corners in enclosed spaces. People who spend a lot of time in enclosed, man-made spaces with corners see this illusion while people who spend more time in natural environments are less likely to see it.

Heinrich and colleagues examine dozens of comparative studies between people in the Global North and the Global Majority. They look at differences between North America and industrialized, rich populations in Asia, between university educated people and less educated people in the United States and come to the conclusion that, on many – not all – comparative measures, American university undergraduates are at the extremes of the distribution on psychological and behavioral economics tests.

This has significant implications for research. The studies being conducted are methodologically sound, but it’s not clear that you can extrapolate any general truths about human beings from them. “It is not merely that researchers frequently make generalizations from a narrow subpopulation. The concern is that this particular subpopulation is highly unrepresentative of the species”. In other words, it’s a really bad idea to run experiments on American undergraduates and conclude that the results are universalizable – not only is that not true, but American undergraduates are likely to be one of the least representative samples you could possibly study.

(By the way, one of the few groups even WEIRDer than American undergrads are American professors. In particular, Americans – and professors in particular – are extremely confident that we’re right. One study Heinrich and his colleagues cite finds that 94% of American university professors believe that we are above average. So perhaps take everything else I have to say today with a grain of salt.)

I’m interested in this paper because I am worried that scholars may be making some similar mistakes in studying social media. The scholars who experiment on American undergraduates aren’t particularly fascinated by this population: they are a sample of convenience, the easiest population to study.

We often use samples of convenience in studying social media as well. Frequently we design research based around what data is easily available. This led to lots of studies of Twitter based on access to the Twitter API – as a field, we probably paid a disproportionate amount of attention to a platform that was less important in terms of social influence than Facebook or Instagram based on the ease of studying it. We’ve recently seen a wave of work on Reddit based on access to the excellent Pushshift corpus and the ability to do full-text searches against years of data across a whole platform. A great deal of work on mis/disinformation focused on URLs with wide reach on Meta platforms as studied with Crowdtangle, which gives insight into widely shared URLs in public groups, but omits information about more obscure links shared.

You’ll note, of course, that all three tools I just mentioned – the Twitter API, Pushshift and Crowdtangle – are all inaccessible to most researchers at the moment. This is an unfortunate trend as regards “permissioned” ways of studying social media, and given Elon Musk’s influence in Washington, it seems likely that we will see increased hostility to research on social media platforms conducted in partnership with platforms. My lab has a history of “unpermissioned research”, creating data sets without the cooperation of the platforms that are being studied. This includes Media Cloud, a large data set of news stories from around the world, and a pair of data sets my team has been developing at UMass, TubeStats and TokStats.

[image error]

My colleagues Ryan McGrady, Kevin Zheng and I started a project two years ago to generate a random sample of YouTube videos. On the one hand, this is very easy to do – YouTube videos have a predictable URL sequence, and all you need to do is generate random IDs and see which ones exist on YouTube’s server. The hard part is that you have to do this billions of times to find even a handful of videos. We were able to generate a set of random videos and found some shortcuts in the process, which means we should be able to generate a set of random YouTube videos going forward and share them with other researchers.

More recently, we’ve figured out how to do the same thing with TikTok, and we’re about to publish our first paper on that data set. In studying random videos from YouTube and TikTok, we’ve become acutely aware of two biases that we see as shaping what we know about online video in particular, and perhaps social media as a whole.

The first bias is a bias towards popularity. If you look at videos in terms of their influence on politics or on popular culture, it makes good sense to look at videos with large audiences. But it’s worth remembering how unrepresentative those videos are of the content on YouTube as a whole. Only 15% of all YouTube videos have a thousand or more views. If you’re sampling YouTube by collecting videos recommended by YouTube’s algorithm – a popular technique for developing samples of YouTube videos – you are mostly videos within that top 15% and many from the top 1-5%.

If your main concern is studying the influence of videos on broad audiences, it’s perfectly reasonable to study the most popular videos. But if you’re studying the broader dynamics of a platform, particularly the experience people having creating videos on these platforms – producer, rather than consumer, dynamics – it’s essential to look at this broader sample as well, and to recognize that the samples are very, very different. The videos that receive the most attention tend to follow the economic model of “like and subscribe” – they are videos made by influencers and brands, and they are hoping to achieve as large an audience as possible. But that’s far from the only way people use YouTube. Kevin Zheng likes to explain YouTube by showing these four videos:

Consider this video by John Green, a very successful YouTube influencer. It’s got 16 million views and is easily within the top 0.01% of YouTube videos – indeed, it’s helped define a category of explanatory videos and spawned countless imitators.

Let’s contrast with an example of a video from a failed influencer – here’s my TED Talk. Like John’s video, it’s been up for a very long time. And in the general scope of YouTube it’s pretty successful – it’s in the top 1% of videos. But it’s been seen by less than a million people and it’s an example of someone who was shooting for a wide audience and missed. It’s easy to assume that most YouTube videos hoped to be John Green and ended up falling short, but that’s not an accurate picture of what we’ve found online.

’

Contrast that, in turn, with a video that’s reached a much smaller audience, but arguably has done a better job of fulfilling its function. This is a school board meeting from Amherst MA, where our lab is based. It’s got about 175 views, putting it in the top third of all YouTube videos. But unlike my TED talk, it’s not a failure.

Indeed, let’s imagine for a moment that this school board meeting got 1 million YouTube views. That would indicate that something went really badly wrong during the meeting in question. The people who put this up weren’t looking for a huge audience – they were trying to bring transparency to a public meeting, to archive a civic event for future use. Those are entirely legitimate – and common – uses for YouTube, even if they are entirely different from influencer logic.

According to our sample, the median YouTube video has 42 views, which implies that half have even fewer views. To give audiences a sense for what these videos feel like, I showed brief clips from a dozen videos, including:

An overexposed image of a window, with a man’s voice intoning “The falling snow”

A highly produced video of a religious leader answering questions about managing one’s emotions, in an Indian language with English titles

A young girl dancing to a Mexican pop tune

Gameplay from a first-person shooter game

A brief clip from a South Asian religious ceremony

A snippet of a cartoon in Russia, possibly from the Soviet era

A mechanic explaining damage to a camshaft

Footage from Minecraft entitled “How diamonds are mined in different countries”

A woman singing a hymn in a church

A clip from a highly produced documentary with a synthesized voiceover

(I created this collage by collecting a dozen videos at random from our set retrieved from sampling YouTube. I took brief clips from each to try to show their content and ended up discarding one video that was sexually suggestive. I am not linking the videos for reasons discussed a few paragraphs below, i.e., concern that while these videos are publicly available, they may or may not be public documents.)

We’ve watched thousands of YouTube videos in our lab, and we’re starting to see some common patterns. There’s enormous amounts of videogame livestreaming, but there’s also millions of hours of religious services from all over the globe. There are ads for cars and apartments, how-to videos for simple and complicated things and lots of homework assignments.

To be clear – these videos are helpful for understanding YouTube from a production point of view, and less helpful for understanding a consumer point of view. Because our randomly selected videos often have very few views, they are not a great proxy for what people are seeing on YouTube. But they are an excellent way to see the diversity of uses people have found for posting and sharing online video. And the very breadth of uses people have put online video to creates a unique and valuable cultural archive.

I’ve started referring to this long tale of YouTube videos as “the quotidian internet”. There are thousands of ordinary, everyday ways to use YouTube or TikTok, and I think we neglect these non-influencer uses at our peril. For millions of people who publish content on YouTube, this – not launching a career as an influencer – is what YouTube is for, and the experience these users have is more like that of the teenager posting homework to YouTube than that of John Green.

Taken as a whole, these quotidian videos represent a fascinating sort of archive. Collectively they represent a picture of the world at different moments in time between 2005 and now. We can get a sense of what people were wearing, how we spoke, how our homes and our technology looked at these moments in recent history, much as we find looking through magazine ads from the 1950s or family photos from Hungary in the second half of the 20th century.

Pulling apart this sample of the quotidian internet by date to see how fashions or behavior change over time is only one way to approach this archive. We’re learning even more by pulling it apart by language and nationality. In our YouTube videos, we use OpenAI’s Whisper to guess at what language is being spoken in a given video. TikTok actually gives us the country from which each video was uploaded. That’s allowed us to create language specific corpora and work with researchers who’ve got the language and cultural knowledge to understand what’s going on.

Jane Pyo, a scholar of South Korean news media, is working with us to understand Korean-language YouTube, and made a surprising observation after watching her first 100 Korean-language YouTube videos: 9 of the 100 were about contemporary politics or news. We were stunned, because in the English-language videos we’d seen, news was extremely uncommon. It turns out that English is the exception here – in many other languages, YouTube is a space to post clips from the news, comment on them and post your own takes on the news.

Jane’s dissertation work looks at South Korean news as a low-trust, but high engagement space. News is perceived to have a strong right bias, and her research documents conflicts between left-leaning critics of the news and their targets in mainstream media. We see those patterns unfolding in Korean news on YouTube – there’s high engagement with news disseminated on the platform, but there’s also a lively culture of political commentary, including this video from a far-right influencer. He’s a middle-aged, far right guy who’s talking about politics as he drives, characterizing the current liberal government as illegitimate, arguing that there hasn’t been a legitimate president since Park Geun-hye was impeached for abuse of power. Given the rightwing lean of Korean media we might expect Korean YouTube to lean to the left, but never underestimate the energy of a middle-aged dude who thinks the world is against him. You’ll note that he has almost two thousand followers, even if this rant has only 38 views, suggesting a community of people using video to talk through political opinion.

Harshita Snehi in our lab has been leading our work to understand Hindi language YouTube videos. Like Jane, she’s finding a lot of news videos, but she’s been seeing a very different pattern. There are thousands of newspapers and small news stations in India, and many are owned by figures like Gautam Adani, a pro-Modi billionaire, who’s been purchasing independent media outlets and influencing their coverage.

Watching clips from these stations in our random sample, Harshi is seeing evidence of a media campaign that features people from rural India talking about ways Modi has made their lives better… and evidence that these videos are the result of careful engineering by Modi’s BJP party, bringing people from rural areas to capital cities and ensuring that they are featured in local media. Harshi’s from the same state as this woman and observes that she’s married and would generally appear in public with her hair covered, as you can see from the scarf she’s wearing. It’s not an accident that a pro-Modi station has found a pro-Modi woman willing to tell the story of how rural women love Modi-ji – these videos are a new form of astroturfing, a way of documenting the public’s love for BJP and ensuring anyone searching for local information on YouTube finds these opinions.

[image error]Visualization by Kevin Zheng

We decided to pay special attention to Hindi because there was a huge surge in Hindi content in 2020 and 2021 – we naively assumed that it had something to do with increased internet access in India. Harshi pointed out that TikTok was banned by the Indian government for national security reasons in 2020, and millions of Indian TikTok users poured from that platforms onto local platforms, onto YouTube and presumably onto Instagram as well.

This helped explain something we’d noticed about Hindi-language content on YouTube – videos that had under 40 views were more likely to have “likes” than comparable content in Russian, Spanish and English, and slightly more likely to have comments. Harshi started looking at these videos and discovered that lots of them are what we now call “friends and family” videos. They’re glimpses of daily life, of in-home religious ceremonies, likely shared with friends and family over WhatsApp or other small-group social networks.

[image error]Our estimates, as of summer 2024, of the size of TikTok and where creators are located. This data is subject to revision as we finalize it for publication.

TikTok has caught on incredibly fast in India and throughout Asia – in the graph above based on our estimates of TikTok’s growth, you can see TikTok in India outpace the rest of the world. No one catches up until over a year after India has banned the platform! Pakistan and Bangladesh, which share some cultural overlaps with India, remain two of the biggest countries for TikTok. We think TikTok is being used in these countries less as an influencer network and more like a video version of WhatsApp, a way in which friends and family are able to stay in touch with one another even when some folks in the conversation have low levels of literacy.

We’re now doing comparative studies of Hindi, Urdu and Bengali across YouTube and TikTok to try to test this hypothesis, which also helps explain why our early estimates of TikTok’s size – in terms of total videos hosted – show it to be several times larger than YouTube. That wouldn’t make much sense if TikTok were an influencer network like US YouTube, but it makes lots of sense if it’s a video-based social network. (We hope to release our paper on random sampling of TikTok, an estimate of TikTok’s total size and geographic distribution of TikTok producers in Q1 of 2025).

Our data-based work can tell us only part of the story. Testing our hypothesis of TikTok as a video-based social network will require both content analysis and ethnographic work. We will need people with linguistic and cultural experience to help us understand the content of the videos we’ve found and to conduct interviews with users of TikTok in Bangladesh and Pakistan. Our data helps us find hypotheses to test, but testing those hypotheses requires an array of mixed methods. But the ethnographic questions we are now asking come directly from analyzing data of quotidian creators.

Our discoveries with short-form video reveal a second bias we want to be careful to question: an assumption that the same technologies work the same way in different parts of the world. There’s a tendency to assume that because YouTube was started in the US that the ways it’s used in the US are the “right” ways and that these patterns will be seen in other nations.

But as we’ve drilled into how YouTube is used in different countries, it’s clear that generalizations are dangerous. And perhaps it’s especially dangerous for TikTok: if our estimates are right, about 5.9 billion of 81 billion videos on TikTok were uploaded from the US – roughly 7.3%. No European and no other North American countries appear in the top 10 – Mexico is #12. TikTok is a Chinese-builr network whose userbase is predominantly from the Global Majority and the responsible way to study it is going to be to center the perspectives of researchers from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia where the network has the most traction.

Twenty years ago, I was a researcher at Harvard’s Berkman Center when blogs were beginning to impact American politics. Colleagues at Berkman organized a conference about blogs and politics partially focused on how left-wing US bloggers were influencing the fringe of the Democratic party in the US. My colleague Rebecca MacKinnon and I felt like an important part of the story was being left out: the rest of the world. We invited bloggers from two dozen different countries to come to Harvard and talk about the different ways blogs were being used in Iran, Iraq, Malaysia and Kenya.

What emerged from that conference was Global Voices, a worldwide network of writers, translators and activists, excited to share what’s going on in their parts of the world with the rest of the internet. Global Voices looks like a global news site, and it is, but it’s also a giant participatory ethnography project, exploring the ways in which the internet – which allows us to express ourselves to local and global audiences – gets used differently by different groups of people around the world.

Global Voices is now twenty years old and has spawned a whole family of related projects. One of the many outgrowths of the community of thousands involved with GV is a set of scholars who work all over the world understanding how digital media works differently in diverse parts of the world. I’m hoping that this is one of several networks that can provide insights into the ways different communities are using online video.

But I also think there’s an amazing opportunity to build new networks around the idea of studying digital media from a global majority point of view and integrating multiple perspectives. I’m proud to be part of a new lab at UMass called GloTech – a group of scholars including Jonathan Ong, Burcu Baykurt, Seyram Avile, Wayne Xu and Martha Fuentes-Bautista, who are doing critical work on technology rooted in local knowledge and expertise and what we can learn from multiple perspectives. In cooperation with Marcelo Alvez at Pontifical Catholic University of Rio, GloTech organized one of the best conferences I’ve been to in years, Disinformation and Elections in the Global Majority, which brought scholars, journalists and activists from India, Moldova, South Africa, Indonesia, Myanmar, Brazil and the Philippines to look at how online disinformation is evolving in different media ecosystems.

This hope of building multiperspectival research networks is why I was so excited to have the opportunity to speak at CSCW this year, and particularly in a year we’re meeting in Costa Rica. Understanding how social media – and particularly social video – work requires us to get beyond the WEIRD biases that assume that how American influencers use social media is the way the rest of the world uses social video. We need to build collaborations between qualitative and quantitative researchers around the world, researchers who’ve got a deep understanding of local politics and culture, to understand the unique and creative ways video is being used differently around the world.

The data sets we’re creating are going to be shared through SOMAR with research teams who are willing to agree to the privacy protections necessary to share this data without exposing personally identifiable information. The videos we’re collecting are “public”, but most of them have only been viewed by a few dozen people – we believe that the ethical way to handle this data is to treat it as personally identifiable information. Within those constraints, my lab is excited about working with collaborators around the world – we’d like to share data with you, to learn from you, to coauthor with you, if appropriate. (When the data set on SOMAR is live, I will link to it here.)

In other words, we’re trying to take on work, understanding the value of quotidian video online, that can only happen if we’re able to work with quantitative and qualitative researchers around the world. More broadly, it means we need more structures to feature the excellent work already being done around the world on social media and to help it reshape our preconceptions about the digital world.

Henrich and his colleagues warn that there’s a danger of WEIRD bias in behavioral research, and I think it’s likely that we’ve replicated some of those biases in social media research. But we have the potential to go from WEIRD to wide, to demonstrate that social media evolves differently in different parts of the world, that different people use tools in different and valid ways. We’d love your help exploring the wide world of quotidian video and understanding the global ways this space is evolving.

The post From WEIRD to Wide: my keynote at CSCW 2024 in Costa Rica appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

December 6, 2024

Rising Voices: Listening to the world on its own terms – an update from the Global Voices summit in Nepal

A MASSIVE part of Global Voices is the Rising Voices program led by Eddie Avila. As he puts it, Rising Voice is about “helping communities meet their self-determined needs” – often this means preserving languages and ensuring they thrive in digital spaces. 20 language activists take the stage in Nepal at the 2024 Global Voices Summit to talk about language promotion efforts.

Preserving a language has multiple elements. It’s about ensuring that scripts are digitized, so that we can read and write a language online – this might include scanning and digitizing analog books, as well as designing contemporary fonts. (In one case, it means a calligraphy festival – Callijatra – to celebrate the calligraphy of Nepal’s languages.)

20 activists, 20 languages at the GV Summit

But preserving a language also means ensuring it’s used in modern times. A popular way of doing this is building a Wikipedia edition. We meet a volunteer with the Doteli Wikipedia, which has been underway since 2014. It was founded by a volunteer who wasn’t from the region where the language was spoken, but wanted to ensure the language survived. Now there is a Doteli speaker running the project, and as of 2017, it’s been a standalone Wikipedia project. There’s a digital dictionary for the language as well.

These challenges are not to be underestimated – there’s not a single, agreed upon script for Doteli. And volunteers in the project speak different dialects of the language. They’ve decided to solve the problem in action: let’s work together and see what emerges.

Another approach for linguistic survival is seeking a language’s presence in Google Translate. We hear from an organizer who’s worked to create enough of a corpus in Nepalbhasa, a language spoken by the Newar people, which has been threatened since Nepali has emerged as the dominant language in the country and particularly in the Kathmandu Valley. Much like creating a Wikipedia, a Google Translate instance is a way of ensuring a language is “on the map” globally, and offers infrastructure to ensure learners and less-experienced speakers can connect with content.

Much of the work Rising Voices has done over the years is with communities in Mexico, Central and South America, areas where indigenous languages are threatened by the emergence of Spanish as a regional language. Abisag “Abi” Aguilar from Quintana Roo, who is studying to be an elementary school teacher, makes TikTok and Instagram videos about traditional sweets and medicines in the Yucatec Mayan language. This work brings Mayan language into online spaces and is complemented by local arts and crafts workshops which create environments for children to learn about their culture and create environments where children feel safe speaking their languages.

Genner Llanes-Ortiz at the Global Voices 2024 summit in Kathmandu, Nepal

Professor Genner Llanes-Ortiz has been working with Global Voices in partnership with UNESCO to create “Iniciativas digitales para lenguas Indigenas” – digital initiatives for indigenous languages – a toolkit in Spanish and English to help people preserve and promote their languages. The toolkit is the result of work since 2014, including annual meetings in Mexico which bring together indigenous language speakers to build a structure for protecting languages:

Facilitar (Facilitate)

Multiplicar (Expand)

Normalizar (Normalize)

Educar (Educate)

Recuperar (Recover)

Imaginar (Imagine)

Defender (Defend)

Proteger (Protect)

Within a framework like this, Genner showcases efforts like a First Languages map in Australia, culturally appropriate emojis and comics that celebrate local languages and cultures.

Our session closes with activists speaking their local languages, with explanations of why it’s so important to speak their language. (A screen behind the participants offers translation of their words). Here are some excerpts:

Amrit Sufi, speaking in Angika: “I see a future in which the new generation doesn’t feel inferior about speaking Angika and carries it forward joyfully.”

Janak Bhatta, speaking in Doteli – “Death of a language leads to the death of literature, culture and civilization. It is the death of heritage… Forgetting your mother language is like drowning and disappearing.”

Sadik Shahadu, speaking in Dagbani – I hope to see significant improvements for Dagbani in Machine learning applications, natural language processing (NLP) and language AI such as Google translate and chatGPT.

Umasoye Igwe, speaking in Ekpeye – “I want to see my language being used by all members of my community as the primary language of communication offline and online.”

Siya Masuku, speaking in isiZulu – “In my context as a graphic novelist working in isiZulu, I would like to create stories that can be adapted from print to film, empower amaZulu to take ownership of their language revitalization efforts, and collaborate with other indigenous language communities to create language education programs and materials, research and academia.”

Subhashish Panigrahi, speaking in Balesoria-Odia “To use digital tools for your language, social media is a great starting point because it helps you connect with the community, particularly the youth.”

I am periodically reminded how Global Voices has grown and evolved since Rebecca MacKinnon and I tried to feature blogs from outside the US to tech-savvy audiences in American academe and journalism communities. We focused on making other conversations visible to English-speaking audiences, sometimes translating, but always featuring work in English. It wasn’t Until Portnoy Zheng started translating stories from Global Voices that we even discussed other language editions of the site.

Now Global Voices Lingua publishes dozens of editions of the site in different languages, and we offer fair trade translation services that are used by many leaders in the open source and international development communities. Many GV authors write in their native language and have their words translated into English, French, Spanish or other global languages. And the work of Rising Voices means that our community is not just reaching Japanese and Russian, but Doteli and Dagbani.

Eddie’s work is probably the furthest from any work I’ve personally done on Global Voices – I am working hard to get better at Spanish and learn enough French to navigate my frequent visits to friends at Sciences Po in Paris. But I am absolutely convinced that the work Eddie and Rising Voices are doing to preserve and promote multilingualism online is some of the most important work to ever have come from our community.

The post Rising Voices: Listening to the world on its own terms – an update from the Global Voices summit in Nepal appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 28, 2024

Danielle Allen at UMass Amherst on “How to be a Confident Pluralist”

Danielle Allen is one of the great thinkers of our generation… by which I mean the GenX generation that teeters on the brink between hopelessness about the future of democracy and passion about the ways in which our systems could be changed for the better. She is a classicist and political scientist at Harvard University, a former candidate for Governor of Massachusetts, and a democratic activist, leading Partners in Democracy.

More personally, Danielle is a friend and mentor, someone I turn to when I am feeling hopeless about the state of democracy in our country. We disagree on many things – reacting to my book Mistrust, Danielle has been clear that she’s committed institutionalist, dedicated to change through existing political systems, while I’m a big believer that some of these systems need to be productively disrupted. She’s a deep believer in the hard work necessary to build alliances between diverse groups of people. And she’s someone who’s done a fantastic job of using positions of meritocratic power – visible academic posts, a column in the Washington Post – to give voice to important issues around race, class, power and justice.

Danielle Allen in the UMass Amherst Old Chapel

The timing of Danielle’s talk is fascinating. We’re a week away from a very scary election, and this morning Danielle announced that she’s stepping away from the Washington Post, reacting to Jeff Bezos’s decision to prevent the newspaper from endorsing a presidential candidate. I had the chance to catch up with her this morning off the record and know that she’s working hard to maintain hope and optimism at a moment where things feel fragile and fraught – here’s my notes from her talk to a UMass audience this afternoon, titled “How to be a Confident Pluralist”

Danielle notes that this is a moment to consider what a healthy, flourishing democracy requires of us. Her work at Harvard, and as an activist, is on democracy, past, present and future… and she assures us that there’s no question mark at the end of that phrase. She shares her heritage with democracy, including a grandfather who established a first chapter of the NAACP in northern Florida in the 1940s, a moment where demanding the vote for African Americans required risking ones own life. Her grandparents on her mother’s side worked on women’s suffrage, with her grandfather marching for women’s rights while her grandmother gave birth.

Danielle’s father had 11 brothers and sisters, and she tells us that someone was always running for office. In 1992, her aunt was on the ballot in the Bay Area for the left-wing Peace and Freedom Party, while her father was running for Senator as a Reagan Republican. They couldn’t have been further apart, she tells us – her aunt was one of the first women married to another woman in California, while her father was a pipe-smoking, virtue-focused conservative. They fought fiercely over the Thanksgiving dinner table. And they both lived lives very consistent with their values and ideas. As a young woman, Danielle watched the debate, and noted that they shared a sense of purpose: a commitment to equality, empowerment and self government. They disagreed passionately about how this came about, but they both believed individuals needed the ability to succeed and grow. And Danielle knew that they had a bedrock commitment to treating each other with respect.

Many of us live with the question, “Can democracy survive?” or “Is democracy all it’s cracked up to be?” Danielle is confident in her answers – yes, democracy is essential. The question is how we get out of these troubled times and into a place where democracy works and flourishes.

If we are going to be free, if we are going to be able to shape our own lives, the key question is how we join in community with others to shape our collective lives. That seems harder now than in 1992 – the space between the left and the right may be even further than between the Peace and Freedom party and Reagan’s Republican party. But the path forward is the path of confident pluralism.

At the heart of confident pluralism is the idea that you are confident in your values and what they lead you to… and open to the idea that others are also passionately motivated by their own values. You need to understand and feel confident in defending your values, but confident enough to understand that someone else is working from values as well. (She namechecks John Inazu for putting forward the language of confident pluralism she is using here.)

Her father and her aunt were fighting to be part of institutions that channeled disagreement into democracy. You cannot have a political system without disagreement, but the point of democracy is to channel that disagreement into politics, rather than into violence. Fighting for the right to vote in 1940s Florida is part of fighting to be part of the contest. The end result of that contestation is not going to line up with your desires. 330 million people with different lived experiences is going to lead to compromise and negotiated settlement. Literally no one is going to get their perfect outcome. That makes democracy sound like a lot less fun.

But wait, isn’t democracy supposed to be the will of the people? That will of the people never looks like your will or my will. But being part of that process is that her grandparents were working for.

Diverse cultures should give us a diversity of thought, potential and ideas. The many ways of life that can be lived alongside one another are part of the benefits of pluralism. Being part of that process gives you the benefit of empowerment – you are part of the process, even if you don’t get exactly what you want.

We are at a moment of profound transformation: the global economy has been radically transformed by technology. Industrial activity has moved outside of the US, the economy has been reorganized around services, and we continue feeling these transformations in how out societies and workplaces function. Social media and the fracturing of attention is transforming us, and the rise of AI may transform things even further. Massive investment in technology is transforming the public sphere, including journalism and media, as well as new industries like social media and search. There’s enormous concentration of wealth, and disempowerment of large numbers of people in society.

We are watching the struggle of democratic institutions to navigate rapidly changing conditions – not only these economic challenges, but global challenges like climate change, and local challenges like gun violence. At the same time, authoritarian countries seem like they are adapting more quickly to some of these changes. Is democracy actually helping us, at a moment where it seems so toxic, divisive and paralyzed?

Those autocratic forms of governance don’t build legitimacy over time. They squeeze people out of participation and remove large swaths of the public from decisionmaking. Democracies, by contrast, enable the whole of society and takes advantage of their wisdom. She cites Amartya Sen’s observation that a democratic India has not suffered a famine, because the power of voters can pull attention to the suffering of people who might starve in an autocratic system.

The democratic pathway can look like it’s not getting the job done. For democracy to meet and master the challenges of a time like this, we need the collective intelligence of people working together on these problems. That, in turn, requires the culture of confident pluralism, the willingness to put opinions on the table and negotiate with others participating in the process.

She offers five steps for the prospective confident pluralist:

1) You need to know what are your core values, and why? Freedom? Equality? Justice? Wealth? Family? God? Solidarity? Community? Why do I put these forward, how are they different from what my parents valued?

2) Commit to the institutions of negotiation. You have to commit to nonviolence in decisionmaking, channeling disagreement into negotiation.

3) We have to know how to actually compromise. You can’t have these structures without compromise.

4) If you’re going this work of bringing compromise into your practice, it begins with listening – you need to understand both your own values and the values of others. One path to this is to mirror back to others what they said and check that you understood people correctly. Try this, and you’ll find 90% of the time, the other person will tell you “No, you didn’t hear what I was saying” – it can take a long conversation to even get to a strong articulation of what you’re disagreeing on… and you’re likely to find synergy and common ground in the process.

5) Finally, you’ve got to reject the culture of toxicity. You have to reject name-calling, the assumption of ill intent. Instead, you have to mirror Danielle’s father and aunt, having bedrock respect and ensure the safety of the other person.

Danielle talks about her work with a framework for curriculum for civics classes for K-12, funded by both the Trump and the Biden administrations, with a group of 300 individuals representing a wide range of geographies, experiences and expertise. All had an urgent sense that kids deserved richer civic learning opportunities, and all knew they would disagree on a bunch of stuff. The goal was to take the disagreements seriously, dig in and do the hard work so they could get to the finish together. That worked for about two weeks, until an argument: Were we educating people for life in a democracy or life in a Republic?

In Utah, it’s a matter of state law that we educate people that we live in a Republic, not a democracy. It’s a red herring, Allen explains: both words were used in the founding of the country. After a great deal of argument, they saw the values behind the arguments: rule of law, order and structure for the Republic folks, universal inclusion and popular participation for the democracy folks. They found a compromise around “constitutional democracy” as words that honored both.

She refers to a commission designed to bridge across political divides, Our Common Purpose, convened by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, which came up with 31 recommendations for how we could transform democracy. (I was part of this commission.) The electoral college was an extremely fraught issue, because it can undermine the legitimacy of democracy, allowing the minority to win presidential elections. Democrats often wanted to get rid of the electoral college, while Republicans argued that the thumb on the scale for smaller states was essential. Both sides could see that a result that didn’t align with a popular vote was a problem, as was the ways of ensuring that smaller states weren’t silenced by California and Texas.

The solution that emerged was an expanded House of Representatives. It’s been roughly 100 years since we’ve significantly expanded the House, which would allow larger states to have more representation, but still give a boost to smaller states through the Senate. (Danielle ended up gaining bipartisan consensus for a significantly larger house, doubling the size. I argued for a 10,000 person house, holding to the original 30,000 to 1 ratio in the Constitution, which no one else liked as an idea.)

The only way to get these compromises: reaffirm the dignity of the people in front of us, work to understand their values, and seek to find solutions that allow us to advance democratic institutions together.

The post Danielle Allen at UMass Amherst on “How to be a Confident Pluralist” appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 9, 2024

What if our nation is not built for climate change?

Florida is preparing for Hurricane Milton, the second significant storm in two weeks to impact the southern US. Hurricane Helene killed at least 220 people and caused horrific damage in North Carolina, many miles from the coast, where massive rainfalls triggered widespread flooding.

These storms are likely part of a new normal, in which warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico evaporate more, supercharging storms with more wind energy and greater rainfall. A chart in the New York Times shows just how warm this season has been compared to the already warm past decade – surface temperatures for much of the Gulf is 90F (32C), and this excess heat was predicted to lead to a terrifying hurricane season for 2024. Those predictions seem to be coming true.

In late August, 99% Invisible, the wonderful podcast from Roman Mars and crew on design and urbanism, ran a six-part series produced by Emmett FitzGerald called “Not Built for This”. Examining the surprising brittleness of American infrastructure in the face of climate change, the series is a portrait of a country that’s being transformed and doesn’t realize it yet.

The series takes on some of my favorite topics including managed retreat (offering incentives to move people from the most vulnerable neighborhoods to safer places), the perverse incentives that surround the insurance industry and its regulators, and the idea that there may be biological maximum temperatures that species – including humans – cannot adapt to.

The series does what good climate coverage must do: pair scientific fact with great storytelling, giving us the voices of people who are being forced to make major life changes. Some of those life changes include moving – one of the most powerful stories is of a woman pressured out of her neighborhood in Lake Charles, Louisiana by a buyout, giving her money for a house that would likely be unsellable otherwise. While the funds allow her to move to a less flood-prone neighborhood, it takes her from a tight-knit Black community and puts her in suburbia, and she wonders why the city couldn’t have invested instead in making her neighborhood more resilient.

The message of the series is in the title: our infrastructures were simply not built to survive the sorts of extreme weather that is rapidly becoming routine. There are some ironies to this: Lake Charles is a city built to serve the oil and gas industry, and it’s been one of the most profoundly affected by climate change, with rising sea levels, risk of storms and serious heat risk. (Risk Factor from FirstStreet.org lists heat and wind risks for Lake Charles as Extreme, its highest category, and flood risk as moderate, rising to major for its roads and infrastructure.) Tampa, squarely in the sights of Hurricane Milton, is similarly understood as a high risk location with major flood risk, and extreme wind and heat risk.

But you don’t have to be on the Gulf Coast to be at high risk from climate change. The New York Times ran a story titled “Climate Havens Don’t Exist”, noting that many people had moved from coastal North Carolina to the mountains surrounding Asheville, only to face the wrath of hurricane Helene. The dangers of the Asheville area were known to people who model climate change – while Asheville itself was known to have major flood risk (the fourth of six levels in FirstStreet’s models), Chimney Rock Village, NC, which has sustained some of the most significant damage, was known to have severe flood risk.

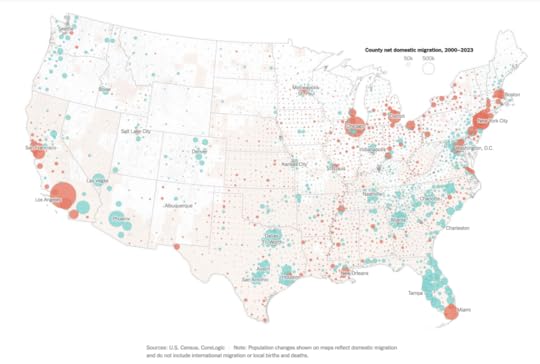

The Times headline is probably provocative but wrong – there are climate safe havens, but moving from the shore to the mountains may not be the reduction of risk you’d hope it would be. Many of the safer locations to mitigate climate risk are in the Great Lakes region, an area that’s been losing population for decades. Indeed, over the past decades, Americans have continued fleeing safer locations and moving towards more brittle and vulnerable ones in the south and west.

Americans have migrated from north to south in great numbers, increasing the population in cities vulernable to wind, flood and heat risk that increases with climate change.

Abrahm Lustgarden, a climate reporter for ProPublica, wrote an excellent book called On the Move about climate-based migration, in the US and globally. Lustgarden’s personal decisionmaking informs the story: he lives in a wildfire-prone part of California, keeps a “go bag” packed at all times in case his family needs to flee, and intersperses his own questions about whether it’s time to migrate with his interviews throughout the book. In the wake of Helene, he notes that we might finally be seeing evidence that at-risk communities might lose population in the near future. The evidence is subtle and complex: it doesn’t mean we’re seeing the abandonment of cities like Tampa, but that growth in the most vulnerable areas may be 2-7% below where it would have been if these communities were not experiencing significant climate risk. But it can be really hard to see those patterns against a 70 year pattern of Americans moving from the Northeast and Midwest to the South and West and a more recent pattern of moving from central cities to suburbs and exurbs in search of more affordable housing.

If we do see cities like Tampa start to lose population – at first by growing more slowly – Lustgarden predicts we’ll see the wealthiest and most flexible move first, with the poor and elderly left behind. This could lead to a “death spiral” for cities, with fewer taxpayers left to fund essential infrastructures and services. So not only are our infrastructures not built for this, but we may be facing cities that aren’t built to fund this.

I found the fifth episode of Not Built For This to be the most powerful and memorable. It was, I suspect, meant to be the “good news” episode – it’s the story of how Hamilton City, CA, a small community of Latino farmworkers located outside of Chico, finally got a levee to protect their homes. And while it’s a moving story with funny elements – a local fundraising event that became famous for its homemade tamales is a recurring theme of the episode – it’s basically a twenty year story of government bureaucracy failing to protect vulnerable people, until it finally did. My takeaway: if it requires twenty years of tamale-fueled fundraisers to get sufficient money for a poor community to build a levee, we’re all screwed. Not only is our country not built for this, but its processes are too slow and onerous to react to an interlocking set of crises that are unfolding faster than we expected.

Hurricane Helene has already become highly politicized, thanks in part to a wave of disinformation from right-leaning news sources anxious to shift blame for slow hurricane recovery to the favorite target of undocumented immigrants. (The conspiracy theory holds that FEMA is running out of money to help flood victims because they’ve overspent on resettling undocumented immigrants in the hopes of securing democratic votes. It’s not true – while FEMA has been helping resettle immigrants, in part because of stunts by red state governors bussing migrants to blue states, FEMA is not out of money.) Milton seems likely to affect Florida (with a vocal pro-Trump governor) and the swing states of Georgia and North Carolina, and how these states recover from hurricane damage may affect the 2024 election. But once that smoke clears, we need – as a nation – to have a broader conversation about where and how we live.

The post What if our nation is not built for climate change? appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 29, 2024

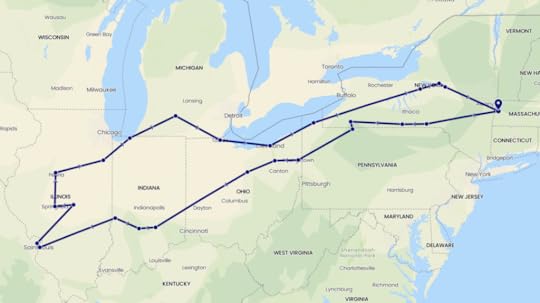

Road trip: The Company Town and the Corn Fields

“The rest rooms are upstairs. Turn left at the Chihuly.”

While those aren’t the directions I usually expect to hear in the Visitors Center of a small city, Columbus, Indiana is anything but an ordinary town.

Dale Chihuly chandelier, Columbus Indiana visitors center

There are two primary reasons to come to Columbus, and to some extent, they are the same reason. Cummins is headquartered here, the makers of diesel engines and generators that power trucks, buses, boats and buildings around the world. And Columbus has more architecturally significant buildings in the span of a few blocks than most major US cities do within their entire footprint.

J. Irwin Miller is the explanation both for why Cummins is in Columbus and why I detoured in my drive across Indiana to visit. The child of a college professor, Miller was born in Columbus in 1909, educated at Yale and Oxford, and joined Cummins, a family business in Columbus, in 1933 – his uncle, a banker, was cofounder of the company, which was starting to produce diesel engines for locomotives. After a stint in the Navy in the South Pacific during WWII, Miller ascended the ranks at Cummins, becoming president in 1947 and chairman in 1951. And then he started having some fun.

First Christian Church, Columbus, IN