Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 4

August 17, 2024

Road trip: Peoria to Kankakee

In 1999, a book called The Places Rated Almanac offered a ranking of American cities in terms of their desirability as places to live. There are a lot of these rankings – they’re now a staple of click-based internet culture. There’s nothing preventing you from creating your own arbitrary ranking of America’s best or worst cities. Indeed, you could misread the project that I’m trying to do here, visiting what I’m calling “undervalued cities”, as a ranking of the potentially worst. (My point, in case that hasn’t been clear, is that these places are often surprisingly great and that market prices don’t always equal lived reality.)

This particular listing offered Kankakee, Illinois as the worst city in the United States in terms of crime, job prospects, and other quality of life factors. Being ranked last on someone’s arbitrary list wouldn’t have been a big deal but for the fact that David Letterman, at that point an enormously popular late night host, made Kankakee a regular bit. First, he did his top ten list on Kankakee, offering possible tourism slogans:

Number ten. You’ll come for a pay phone. You’ll stay because your car’s been stolen. Number nine. Ask about our staggering unemployment rate. Number eight. We put the ill in Illinois. Number seven. We also put the annoy in Illinois.

Then, in a subsequent week, he called the mayor to ask whether the attention to the town had caused any problems. The mayor, Donald Green, turned out to be a funny guy. Asked what the Indian name “Kankakee” meant, he quipped, “middle-class factory town”. To keep the gag going and to “help” Kankakee, Letterman gifted the town with a gazebo… and then a few weeks later, with another gazebo so that Kankakee could attract tourists to the twin gazebos of Kankakee.

The charming part of the story happens fifteen years later, when students researching their hometown in 2014 found their town as the butt of a joke on national television. They’re all familiar with these gazebos, but now they see them in a very different light. They see them as tangible evidence of something that they feel every day living in Kankakee, which is the ways in which they are look down on and made fun of by residents in neighboring towns. Kankakee is what you might call the “anchor city” – while it’s a small town (24,000), it’s the biggest population center and the county seat for a relatively rural region of northern Illinois. (My trip is ordered around MSAs – metropolitan statistical areas – and this leads to some weird disparities. Gary Indiana with 68,000 people is part of the Chicago MSA, while Kankakee stands on its own.)

Driving through Kankakee, it’s at the junction between the parts of Illinois that are soy and corn, and the part that’s America’s steel belt. When some of the industrial employers in Kankakee shut down, as has happened all over the Great Lakes region, there was an exodus from the town, particularly white flight to neighboring suburbs. The city is now 38% black, 34% white and 23% latino which has led some in the surrounding suburbs to refer to the city as “ghetto”. This American Life, which did an excellent piece on Kankakee and the fate of the gazebos, reports that “skankakee” has an entry in Urban Dictionary – I couldn’t find it.

Still, it’s This American Life from which I head the story of students mobilizing to tear down the gazebos. Correctly assuming they’ll be accused of tearing things down rather than building them up, they decide to build something positive: a rocking chair to celebrate Dave Letterman’s retirement, presented to him in a ceremony in a downtown movie theater that Letterman sends camera crews to broadcast.

Jaenicke’s Root Beer stand, Kankakee

I found the TAL story while waiting for my Italian beef at Jaenicke’s Root Beer Stand, looking for background on the city. All I knew before arriving was its mention in the folk song “The City of New Orleans” about the legendary train that ran down the Mississippi. As such, I started my tour of the city visiting the Kankakee Railroad Museum, which is run primarily by model railroad enthusiasts who built wonderful HO, O and N scale rail layouts, representing not only Kankakee in its glory days, but some of the other great cities of the area.

A car from the North Kankakee city electric trolley.

My tour guide had worked with the Illinois Central Rail and walked us through a caboose showing what railmen used to do, watching the train go around the corner to see if anything was dragging or sparking, something that might indicate a stuck brake or any other potential dangerous situation. According to my guide, the Kankakee River was the first major barrier to the railroad coming south out of Chicago, so the city gained a roundhouse, a mechanical device that allows trains to around on a giant rotating platter, so that the train had gone from Chicago to Kankakee could go back. Once steel bridges made it possible to cross the river, Kankakee emerged as a railroad hub with four major lines coming through the city. As I’m finding all across my travels, having transit turns out to be the key towards having industry. If you have access to rail, you’ve got access to raw materials and a path to ship out your finished goods. And so Kankakee, in the 19th and much of the 20th century became a middle class factory town.

Commercial Kankakee

While Kankakee is certainly not the most vital looking city I’ve seen on my trip, it’s not the worst either. And it’s got the feeling of a town that has something to celebrate in terms of its diversity. One of the prettier blocks in town features two beauty shops, one featuring hair braiding, presumably for a black clientele, while the other advertises mostly in Spanish, presumably for a Latina audience. They bracket a cafe that seems to be popular with Kankakeeans of all backgrounds. Across town is a wealth of taquerias, mercados and carnecerias, pointing to a Chicano population and there’s some colorful aspects of hiphop culture, some tricked out SUVs and one very joyful young black man driving around on a garishly painted Slingshot, an open-roofed motorcycle trike. I can imagine this feeling unfamiliar to someone visiting from a small agricultural town or suburb. But it felt to me like a vital place, working to turn itself around. And mostly, it felt like a place saddled with an unfair reputation.

I woke up that day in Peoria, a city I knew only from a set of vaudeville-era references. I’d always understood the expression “Will it play in Peoria?” to refer to a town that was backwards, hopelessly middle-American and unwilling to experiment. Turns out that’s entirely wrong. Instead, Peoria was a popular stop on the vaudeville circuit, closely linked to Chicago on rail, and was often used as a place to try out new material because the audience was experienced and critical. Whether or not something played in Peoria would often dictate how well it would do out on the road.

The phrase took on another meeting when people started using Peoria as a test market, because it had demographics similar to the country as a whole. Then the question of “Will it play in Peoria” became a proxy for “Would a people buy it coming from the city that had roughly the same representation as the nation as a whole?” That changed years ago, Tulsa became the city as Peoria became less white, more black, and less close to representing the nation as a whole.

Peoria has always been the but of certain jokes. Some theorize that, like Kankakee, it’s a fun name to say. Peoria has this wonderful set of mellifluous vowels, which may make it a particularly good punchline, as in, “I spent the four longest years with my life in Peoria one night last week.”

The sign for a local auto shop. Evidently she’s clothed in the winter but emerges when it’s beach season. Peoria, IL

I like Peoria a lot – it’s high on my list of favorite towns on this trip so far. It’s beautifully situated on the Illinois River, and the town is figuring out how to reclaim that space that traditionally has belonged to factories and turn it into a centerpiece of the town. I ran that morning on a trail that follows the river from a riverfront park across the street from Caterpillar’s Visitor Center and a glossy new riverfront museum. Caterpillar’s no longer headquartered in Peoria, but they still have a major presence and some large factories. The Catepillar visitor’s center is a major tourist attraction, with simulators that let you experience driving Catepillar’s big machines. I didn’t visit because I would have felt bad elbowing small children out of my way for a turn.

Peoria’s Riverfront Museum is a great attempt to create a big city museum experience for a comparatively small community (111,000). It’s got a planetarium, a big screen not-quite-IMAX theater, and a set of exhibits that feature some excellent contemporary art and a wonderful overview of local history. The city is the birthplace of Richard Pryor, who began his stand-up career in Peoria’s clubs before conquering the nation. There’s an exhibit on Poro Beauty, whose founder became the country’s first black female millionaire. Peoria is the home of the first commercial automobile made in the United States, which inspired Henry Ford.

Peoria has a lot to be proud of, and the city seems to be putting its best foot forward. There’s a sculpture walk, a mural welcoming people to the community, and an active group of downtown businesses working to encourage people to discover the city. There are some exciting restaurants, a climbing gym, as well as lots of the other features you’d expect in a downtown looking to attract people to loft living in some of the old buildings. Peoria’s got one of the problems I see in many towns as they look for their next act, which is that it’s almost always easier to build new than it is to get people to reconsider the downtown. East Peoria is a pleasant, but boring array of your standard American big box stores and restaurants just over the bridge from the historic center.

Across the Illinois River to the former Hiram Walker distillery in Peoria, IL

As I explored deeper into the city, I started finding Black and Mexican Peoria, including a wonderful spot for catfish and okra in the back of a local market. I also get the sense that, despite my misconceptions of Peoria as straight laced and boring, that it’s a good place to have fun. Looking for the old Hiram Walker distillery, which now makes commercial ethanol for fuel, I stumbled onto two strip clubs that seem to be doing a brisk business. As I was checking in at a downtown hotel, guests were preparing themselves for a night out in a city that has a history of bootlegging, mobsters and having always been a good place to have a good time.

The Alkebulan Museum in Kankakee

Peoria’s got investment from Caterpillar and other local employers and absolutely feels like a town on the rise. It’s harder to know where Kankakee is going. On my way into town, I stumbled onto a museum that didn’t appear on any of my maps. It was closed, but the signage made clear that someone is working hard to preserve Kankakee’s Black history and culture. At the end of the day, that’s what really matters: whether or not someone loves a city and is working hard to take care of it. I look forward to visiting the Alkebulan the next time through town. And perhaps I’ll figure out how to party in Peoria in my middle aged sober sort of way.

The trip so far:

Driving by Data Set

By the numbers: What statistics can and can’t tell you about undervalued cities

A Square Deal in Binghamton

Buried, with dignity, in Elmira

Side Quest in northern Ohio

In search of the “statistically improbable restaurant”

Decatur – From corn to soy to crickets?

The post Road trip: Peoria to Kankakee appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 15, 2024

Roadtrip: Decatur, from corn to soy to cricket city?

Heading into Decatur on Illinois Route 48, you quickly begin to sense a pattern. You pass a field of corn followed by a field of soybeans. Soybeans, then corn, corn, then soybeans. The highway follows the railroad track and every five to ten miles, there’s a small town, little more than a grain elevator, some sort of general store, and occasionally a bar or saloon. By the time I got to Decatur, the main question on my mind was this: Was this planting strategy an economic hedge? Were farmers betting that if one crop failed or the market was lousy, the other crop would sell, or was there some good agricultural reason to rotate corn and soybeans?

Staley’s house – now a museum – in Decatur

And because that’s the sort of guy I am, it’s the first question I asked Laura Jahr, the director of Decatur’s Staley Museum, when she let me in. I was the only museum guest today, so she had some time for extra questions. Gene Staley, as it turns out, is the reason why Illinois’s full of corn and soybeans. Staley grew up in North Carolina and didn’t much care for farming. However, he possessed significant talents as a salesman. The product that made it big for him was baking soda. At turn of the 20th century, baking soda was a novelty that let housewives make cakes and cookies much more easily than whipping eggs full of air. But it was corn starch that made his fortune.

Staley and a single employee began packaging corn starch in Baltimore, a bustling city where he had settled. They were a great success, and quickly Staley ran into supply problems. He purchased a disused mill in Decatur – a reminder that cities have been changing their core industries for well over a hundred years now – and turned it into a corn wet-mill. Local farmers overplanted corn to meet the mill’s needs and quickly experienced lower yields and failing crops.

An exciting array of Staley products available for the home!

Legend has it that Staley had been given soybeans as a child by missionaries, recently returned from Asia with stories of the “wonder bean”. Soy was being grown in North Carolina, mostly for cattle forage, and also because it had a tendency to restore the soil that corn has been grown on. Soybeans “fix” nitrogen, taking atmospheric nitrogen and making it accessible to plants via bacteria that live on soybean roots. And rotating crops helps prevent pests that can destroy one species from taking hold year after year. So Staley began encouraging farmers to plant soy, promising to pay for their beans, and building a mill to extract soybean oil, first through steam and then through hexane extraction.

So that’s why there’s corn followed by soy, followed by corn. And the kernel and the bean – the title of the Staley biography I bought in a local bookstore – turned Decatur into Soy City and Illinois into the US’s #1 soy producer.

The castle in the cornfields: Staley’s headquarters

The heyday of the Staley Company was the first half of the 20th century – it was bought by British firm Tate & Lyle in 1988, but was just spun out as “Primient”, meant to invoke “primary product ingredients”, a US firm that basically has the same assets and purpose of the Staley company. Walking by the plant in the afternoon, a woman who lives across the street told me that they’re hiring, and that the parking lots are full for the first time in a while. She loves the colored lights that illuminate the company headquarters each night, a building understandably called “The Castle in the Cornfields”.

I love stories like Staley’s, which combine multiple transformations of society into a single figure. We can trace three to Staley. One is soybeans, which were virtually unknown in the midwest and only grown as cattle feed in the south, but which have become a major source of protein globally (they long have been in Asia), something important in a world where animal protein feels like an increasingly unsustainable luxury. The second is corn syrup, which Staley and company produced vast quantities of, and helped turn into a primary product ingredient for much of the American food system, with seriously negative effects. At the 21c Hotel in St. Louis earlier the same day, I saw a wonderful piece in which an artist had encrusted three cans in sequins, one of Budweiser, one of Red Bull and one of Coca-Cola. She titled it “Canned corn, canned hype, canned corn”.

The third transformation is a bank shot, but an arguable one. In the early 20th century, college football was quite popular but professional football had not really developed. Instead industrial teams played one another and Staley really wanted his Decatur team to be competitive. They faced off against another factory team and Staley was very frustrated that that team appeared to have employed some ringers, recent college football players who were evidently on the payroll mostly for their football prowess. Staley figured if that’s the way the game was played, he’d just go one better and recruited a whole football team made of some of the best college players of the day, all of whom he hired at the Staley factory. In fairness, they did work at the factory, though Staley gave them two hours off each day for practice. When they started playing the local competition, they crushed them.

However, running a football team is different from running a factory and significantly more expensive. Staley discovered that the road games played in Chicago sold vastly more tickets than those played in Decatur, where he mostly sold highly subsidized tickets to his factory employees. So the team lasted as Staley’s team from 1920 to 1922 before becoming the Chicago Bears. Arguably, we have Staley to credit or blame for professional football in the US. (Baseball was already significantly professionalized, so he was replicating an existing system.)

I didn’t come to Decatur for Staley, though. Decatur was, in many ways, my primary destination on this trip. I have organized this road trip around the idea of the undervalued city. I’ve been using a simple metric, median home price over median income to figure what cities are undervalued. Decatur is number one in the US. Last year you could buy a median home indicator for a little less than two years median salary.

The Masons lodge in Decatur, in need of some love.

“Cheap” is a complicated word. We tend to be suspicious of the cheap. It’s a synonym for shoddy, not well-made, low quality. I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect coming to Decatur. I had a tough time finding many attractions I wanted to see or restaurants I wanted to visit. And so I was worried that I might have set this trip up around a city I was going to dislike. But that’s not what happened.

Decatur appears from nowhere, out of the fields. It’s got a tidy and surprisingly energetic downtown. Walking around on a Wednesday evening, parking lots were busy, people were dining outside at a variety of restaurants. There was a microbrewery and a cigar bar, and cute shops, including Novel Ideas, one of the best used bookstores I found in my recent travels. You weren’t going to mistake Decatur for Youngstown, OH or Bradford, PA, some of the most downtrodden cities I’ve been to on this trip. The city has shrunk in population since its heyday in the 1980s (94,000) and is down to about 70,000, but there are signs that this might be the bottom. Unemployment is higher than the state average, but there are significant manufacturing employers, and there’s evidence of an immigrant population, a highly rated taqueria and a Latin market, as well as some American retirees moving in, drawn by low house prices.

I’m reading the largest insect protein facility in the US in the city, growing crickets for animal feed. (If anyone can get me a tour of this facility, I will turn the car around right now!) On a sunny Wednesday night in August, watching streets filled with life, Decatur looks like a pretty good place to be.

The trip so far:

Driving by Data Set

By the numbers: What statistics can and can’t tell you about undervalued cities

A Square Deal in Binghamton

Buried, with dignity, in Elmira

Side Quest in northern Ohio

In search of the “statistically improbable restaurant”

The post Roadtrip: Decatur, from corn to soy to cricket city? appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 14, 2024

Roadtrip: In search of the “statistically improbable restaurant”

The first thing I do when I come to an unfamiliar city is look for where I want to eat. This is in part because I am a large man and eating is one of my primary pleasures in life. But looking for exciting food is one of the best ways to understand the past and future of a town.

If you come to visit Pittsfield, Massachusetts, you’ll find the usual chain restaurants and a number of red sauce Italian places. You might be surprised to find some very good Polish food, often in obscure little corners. My local orchard is planted with a wealth of sour cherry trees, which were particularly popular with the Polish immigrants to the area to make sour cherry brandy. You can get golumpki and other handmade Polish delights in the dairy case next to Vermont cheddar cheese and apple butter. I have no Polish heritage, but as a nod to the Polish cuisine all around, the breakfast buffet when Amy and I got married featured kielbasa and homemade kapusta, a wonderful fried sauerkraut. In other words, the Polish restaurants give you a clue to some of the migrant past in and around our town. So when I head into an unfamiliar city, I want to see whose cuisine is on offer, to see who I’m going to meet as well as what I want to eat.

Searching for restaurants gives me tips on neighborhoods that are being transformed by recent immigrants. When Amy and I passed through Lewiston, Maine earlier this summer, our first stop was the highest rated Somali restaurant. Not only did we have a delicious plate of food, but we also found ourselves at ground zero of the local Somali community. We were able to roam throughout the neighborhood they have made their own, visiting the grocery stores and import export shops. We were especially fascinated by the almost visible boundary between Somali Lewiston and Old Maine Lewiston at the public library, a reflection perhaps that integration of the Somali community has been a complex process.

When I look at the restaurants in an unfamiliar city, I’m looking for the statistically improbable restaurant. Here’s what I mean by that phrase: Early in Amazon’s evolution, they offered a clever feature to look at the contents of the book without giving readers full access to the text. One of the features they offered was “statistically improbable phrases”. A statistically probable phrase is a common one: “good morning”, “early afternoon”. A statistically probable phrase doesn’t tell you very much. It’s so common as to be almost meaningless. But a statistically improbable phrase can serve as a topic summar of a book. Amazon no longer offers this feature but SIPs of my book Mistrust would have included “global voices”, “digital cosmopolitanism” and other signatures of the ideas I was trying to share.

Let’s assume for the moment that most towns over 5,000 people have at least one Chinese restaurant. (Jenny 8 Lee’s Fortune Cookie Chronicles is a good introduction to this phenomenon.) The presence of a Chinese restaurant doesn’t tell you much about the demographics of a town, unless it’s specialized in Szechuan or Xian cooking, for example (in which case, you’re almost certainly in a big city.) Similarly, towns over 15,000 have a Thai restaurant, through a conscious government strategy of “gastrodiplomacy”. But if you encounter a Bosnian restaurant in a city of 50,000, it’s almost certain that there’s a significant local Bosnian population.

This trick isn’t that impressive in global cities like New York, Los Angeles or Houston, but for cities under a million, it can tell you a great deal about who’s come to town and who’s been in town. In my experience, restaurants are a trailing indicator while grocery stores are leading indicators. This makes sense: when people settle in an area they first need places to buy familiar food. Only once you’ve got a significant population of fellow immigrants to eat your cooking, or enough economic security that you’re willing to risk introducing your cuisine to your local community are most people able to open a restaurant.

Vansa Ghar restaurant in Akron, OH

When I passed through Akron a few days ago, there were several Nepali restaurants. Indian restaurants are pretty common in cities mid-sized and higher, but Nepali restaurants are pretty unusual. There are several in the Akron area, mostly clustered in northern suburbs of North Hill and Cuyoga Falls. I chose Family Vansa Ghar Restaurant & Bar, in part because the menu had some dishes I’ve never seen before. I ordered jhol momo, dumplings in a sour curry sauce, which was so delicious, I drank it after eating all the dumplings. The other was gundruk soup, which features fermented mustard leaves, which were chewy, tender and delicious, even as I was picking them out of my teeth.

As I enjoyed the food and the service of lovely folks who explained they had just opened the establishment, I read about the Nepali population in Akron. There are roughly 5,000 Nepalis in and around Akron. They are refugees, forced to flee Bhutan when the country often celebrated by westerners for its policy of gross national happiness decided to expel it’s entire Lhotshampa population, an ethnic group with origins in Nepal, but which made up a sixth of Bhutan’s population. The Lhotshampa had been in Bhutan since the 1600s, but were termed “migrant laborers” and sent “home” to a country they’d never lived in.

Alongside Columbus, OH, Erie, PA and Rochester, NY, Akron became a major resettlement site for Nepalis expelled from Bhutan. This article offers a good overview of some of the challenges the refugees face and the institutions that slowly are making it easier to be Nepali in Akron. The community in Akron is now so successful that Nepalis who settled in other US cities are moving to the city to build Nepali culture in northern Ohio.

It was two days ago, and I am still thinking about those jhol momos.

In my experience, towns transformed by refugees generally have three things going for them: inexpensive housing, a reliable local employer and a broader welcome from the city. Despite significant growth, Akron still has a relatively inexpensive housing supply – it’s at 2.8x median income to median house price, tied with Utica, NY, which has become a mecca for Bosnian, Rohingya and Somali refugees. In Utica, there’s a lot of multi-family units – you buy a building, live in half and rent the other to fellow refugees – I would not be surprised to see something similar at work in Akron. The employer of choice seems to be Gojo, the cleaning products company, which has a factory in Akron with jobs for people without much English. And Akron seems to be a welcoming place – North Hill, where the restaurant was located, seems to be a mix of Nepali businesses and Akron residents who are looking to do something experimental or out of the ordinary.

Fine food from The Gambia in Springfield, IL

I’m always on the lookout for the statistically improbable restaurant – I hope to build a map sometime using data from Yelp or Google. But in the meantime, I simply keep my eyes peeled. In Youngstown, killing time while seeing if I could find a replacement wheel, I found a massive flea and farm market on the edge of town. In the very back of the main building was a small Haitian restaurant, closed, but I hope to visit sometime soon. Tonight’s dinner was at Traveler’s Kitchen in Springfield IL, which featured dishes from around west Africa. As I ate my jollof rice and peanut soup, I talked with the server, who is from The Gambia and proudly told me that there are 40 Gambians in Springfield, most students at University of Illinois – Springfield. The young man is getting his masters in public health, hoping to go on to the PhD, and in the meantime, sharing Gambian and West African food with anyone lucky enough to find the place.

Look for your statistically improbable restaurants. It’s statistically likely that the food is great and you’ll learn something about the people who share your city.

The trip so far:

Driving by Data Set

By the numbers: What statistics can and can’t tell you about undervalued cities

A Square Deal in Binghamton

Buried, with dignity, in Elmira

Side Quest in northern Ohio

The post Roadtrip: In search of the “statistically improbable restaurant” appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 13, 2024

Roadtrip: Side quest in Northern Ohio

Sunday morning in Youngstown Ohio, I almost put my road trip to an abrupt halt. I had just visited a surplus store near downtown which featured in its parking lot an “urban assault vehicle”, a camouflage painted car with a giant slingshot on the back. I’ve been led to the car in question by Roadside America, one of my favorite resources for exploring unexpected corners of unfamiliar towns. Going back into the downtown, either I missed a curb jutting out into a lane or a chunk of curb had crumpled and fallen into the lane. One were another, I hit a good size chunk of concrete at about 30 miles an hour, bending my front right rim and instantly deflating my tire.

The “urban assault vehicle” at Star Supply in Youngstown OH

Fair enough, I had a jack and a donut, and I decided I put on the spare and limp to the nearest tire repair shop. And then I discovered that I bought a jack too big to fit under Amy’s beloved Prius C. So, tow truck, friendly open-on-Sunday tire center and the discovery that 15 inch wheels are pretty rare and that Goodyear didn’t keep rims in stock. They helped me get my donut on, I went and bought a jack that actually fits under my car and drove slowly to Akron after exploring a bit more of Youngstown, including the magnificent Butler Institute of American Art and a wonderful back alley in Warren, Ohio that’s dedicated to celebrating local hero Dave Grohl.

Dave Grohl Alley, Warren OH. It’s a real thing – look it up.

I made it to Akron last night for a walk through the beautiful downtown and headed out at 9am to RNR Tires, who advertise lots of wheels in stock. Perry, the friendly counterman, explained that no one wants to upgrade their car with 15″ wheels, and so there are none in stock. He sent me out to a salvage yard to look for Toyota Prius wheels. And so I found myself armed with a lug wrench and my trusty breaker bar at Pull-a-Part of Akron, Ohio.

Pull-a-Part is great. I so wish we had one of these in Western MA or the Albany NY area – I would be a regular. It’s a junkyard where the wrecked vehicles are carefully lined up and cataloged. Each has been jacked up and rests on rusting wheels for your parts-stripping convenience. A search of their database revealed a 2005 and a 2008 Prius. I was halfway into removing a wheel from the 2008 when I realized that it had five lug nuts and that Amy’s car has four. So I searched instead for anything with 15 inch wheels and four lug nuts. After much exploration I found a thoroughly stripped Nissan Altima that seemed to fit the bill. I bought an aluminum wheel for about $50 and brought it back to RNR, fully expecting it would either be too wide for my tires or that the four holes would not match my studs.

That’s a bent rim, alright.

But to my great joy, they did. Perry and his crew mounted my tire on the Altima wheel and I am dictating this post, headed south towards Columbus, Indiana, a town renowned for its modernist architecture.

There’s something to be said for having your plans interrupted. Akron was going to be a brief stop on my itinerary. But in ending up there last night, I took a long walk through the downtown, which is gorgeous. There’s a minor league ballpark beautifully positioned on the canal, which is lined with a walking path, where the canal tow path used to be. University of Akron has built or refurbished a splendid building the main street and there’s a mix of municipal, university and retail spaces that means that even without classes in session, there was activity on the streets last night and the sense of a live, vibrant city. I’m planning on stopping back on my return and visiting the art museum, which was closed when I was there.

The real joy of the unexpected detour is that it forces you to travel in a different way. When you’re a tourist, you’re seeing the sights. Along the way, you might find some great restaurants or get a sense of the vibe of a city by walking around. But you won’t really know what it’s like to try to do something in that place. My happiest years of traveling involved my travel first for Geekcorps, and later for the Open Society Foundation where I worked for 15 years as a board member. I went everywhere from Ghana to Egypt to Haiti as a business traveler with people to visit and things to do. While I saw some sights, I also had the joy of trying to hold meetings and do business in very different places and cultures.

So my side quest was a great introduction to some of the joys of Northeastern Ohio. Youngstown struck me as a classic example of a hollowed out city. There’s stuff going on in the region, but it was certainly not in the downtown of the city. Sunday morning isn’t the best time to encounter a place, so I don’t want to be unfair, but there was not a lot open in the central city. I looked for a hardware store to buy a jack, then an auto parts store, and eventually just for a place where I could buy a cup of coffee while waiting for the tow truck – there was nothing until a few miles out into the suburbs. Later that day, on my spare, I tried to find the Metropolitan Tower, a landmark buildings and discovered most roads in the downtown closed. The reason was a gas explosion that destroyed another landmark building and shut down many of the streets. The crumbing building in the picture above reflects a tragic accident, but it felt a bit symbolic in a city that’s lost 65% of its population since it’s peak in the 1930s. Still, the town is active and busy in a ring of suburbs just around the city where nice folks tried unsuccessfully to help me get back on the road.

Akron’s beautiful renovated is surrounded by a wealth of scrap yards, salvage yards, and other practical resources appropriate for a distinctly car-oriented city. Akron has been the home of Goodyear and Firestone and has evidently moved into polymer engineering as tire production has moved overseas. But it’s still a car town. As I was stripping the donor Altima, at least a dozen other teams came by to grab the parts they needed and fixed up their rides in an impromptu open-air garage in the parking lot outside.

I’m grateful to have been sidetracked in Akron and happy to be back on the road. A special shout-out to Perry who guided me through finding an appropriate wheel, mounted and wouldn’t charge me for his time. Needless to say, I left him a nice tip. If you wheels in Akron, stop by RNR. If you want to have a good time, I recommend the Pull-A-Part. And I heartily recommend Akron, which is a new favorite spot on the map for me.

The trip so far:

Driving by Data Set

By the numbers: What statistics can and can’t tell you about undervalued cities

A Square Deal in Binghamton

Buried, with dignity, in Elmira

The post Roadtrip: Side quest in Northern Ohio appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 10, 2024

Roadtrip: Buried, with dignity, in Elmira

Every place is a palimpsest with layer upon layer of history written atop one another. Every so often you have the opportunity to scratch below the surface and see the strata of history.

One of those places where the layers become visible is across the street from Woodlawn Cemetery on the outskirts of Elmira, New York. A tidy white farmhouse with a jaunty shed edition at the back was the home of John Jones, one of the most remarkable historical figures I’d never heard of. Jones and two half brothers were born into slavery in Northern Virginia. Their owner, by all indications, a kind woman who believed she would get more work out of her enslaved people if she treated them well, decided to sell her plantation and her property, which included Jones and his siblings. So they fled 300 miles over land over the course of a month in the summer of 1844 and made their way to Elmira, New York.

The John Jones House Museum in Elmira

Jones, for a while, lived in the house of Jervis Langdon, one of the wealthiest men in town who was an ardent abolitionist. But Jones found work quickly first splitting wood, and then later working as the Sexton for the first Baptist Church. Soon, he was living on his own, and his modest house became a major stop on the Underground Railroad, sometimes housing up to twenty escaping enslaved people at a time. Elmira, in the mid-1800s, was well connected to the emerging rail network, with direct connections to Niagara Falls and on into Canada. Jones worked with a black station master in Philadelphia, corresponding in code to make arrangements, to get enslaved people who had escaped to Elmira onto the 4 a.m. baggage car, and from there, across the Canadian border to freedom. Ultimately, Jones was responsible for the escape of 860 former slaves, none of whom were returned to the South.

But that’s not the most remarkable part of Jones’s story. After being Sexton for the Baptist Church, Jones took over as Sexton for a cemetery in town, and then for Woodlawn Cemetery, the massive and beautiful graveyard on the edge of town. Woodlawn was next to a prison camp set up at the Union Army base in Elmira. The camp where Union soldiers from all over upstate New York had mustered before going to fight in the Civil War ended up housing 12,000 Confederate prisoners in the whitewashed barracks built to house 5,000. The conditions were dire, and thousands of Confederate prisoners died during their internment in Elmira.

Each of the prisoners was buried either by or under the supervision of Jones, who took exacting care to ensure that Confederate soldiers were buried with all available information, so that their families would be able to find them. Whatever information was available about a soldier was scratched into their wooden coffins, was carved into a wooden tombstone and was written on a piece of paper sealed in a bottle tucked under the dead man’s arm.

For each Confederate soldier buried, Jones received $2.50, money that he used to purchase a 16-acre farm across from Woodland Cemetery. He built this tidy farmhouse, in no small part, from boards salvage from those barracks turned prison camps. John Jones buried – with care and dignity – over 2,000 men who were fighting for the right to keep him in bondage.

Jones museum docent Cleveland shows me a civil-war quilt.

Cleveland, the wonderful docent at the John Jones Museum, showed me his favorite room. It’s a room in which the layers of wallpaper over the whitewashed barracks boards are visible. The scholars who studied the house have found nine layers of wallpaper likely put on to help insulate the drafty house. You can see rags that have been stuffed in the crevices to seal out the Elmira winter. Cleveland points to the water stain and says, “You can tell he was trying to keep his house dry, but it was an uphill battle.”

A corner of walls and ceiling in Jones’s house, showing layers of wallpaper and rag insulation. The white boards at the bottom are from the Union barracks which became Confederate cells.

A few hundred yards from the Jones house, Samuel Clemens – Mark Twain – is buried in the Langdon family plot, not far from Jervis Langdon, who sheltered Jones when he first came to Elmira. After his childhood on the Mississippi River, Clemens followed his elder brother to Nevada to become a silver prospector. He was so bad at it that he found his true calling – making people laugh, first with stories about his own ineptitude at prospecting, and eventually about his childhood, his travels and the stories he collected along the way. Writing for the Nevada territorial paper, one of his stories – “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” – became a sensation in New York, and Clemens began astounding career of writing and public speaking.

Clemens was, in essence, a stand-up comic and toured the world to an extent that is absolutely remarkable for someone living in the 19th century. While on a steamboat tour of the Holy Land, he met Charles Langdon, son of Jervis Langdon, who showed Clemens a picture of his sister, Olivia. Clemens was smitten to the point where he came to court her at her summer place in Elmira, returning and corresponding with her until she agreed to marry him, in Elmira, in 1870.

Mark Twain’s octagonal study, now on the grounds of Elmira College.

Sam and Olivia spent every summer at her sister Susan Crane’s farm. Susan built Clement perhaps the world’s most lovely writing shed, an octagonal gazebo-like shed with wide windows on all sides where Clement could write and, critically, smoke his cigars which she forbade in the house. In Hartford, CT and in the shed in Elmira, Clemens wrote Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer and most of his other works. The shed sits now on the campus of Elmira College, the first women’s college to teach women with the same curriculum as men’s colleges, rather than preparing them for life as wives and mothers.

Elmira reformatory, now Elmira Corrections Center.

The writing shed, the handmade farmhouse and the graves of Clemens, the Langdon family, and Jones are within walking distance of one another, and of the thousands of confederate graves Jones dug. And just beyond the graveyard is the Elmira Reformatory, where superintendent Zebulon Brockway attempted to reform his charges through imposing military discipline, a model that spread from Elmira to prisons throughout the country. Between the Reformatory and the Civil War prison camp, Elmira got the name of “Zebra Town”, a town that corrections built. A 2010 book by journalist Greg Donaldson, titled “Zebratown”, examines how Elmira has become home for many black men who, during their incarceration, develop relationships with people living in small towns and chose to reenter society through a town whose glory days, to some extent, preceded the Civil War.

Downtown, near the history museum, Elmira, NY

There’s not much to downtown Elmira these days. A massive flood in 1972 destroyed much of the city, and 40% of the buildings in the downtown were torn down rather than refinished, in part, because the Southern Tier as a whole, was facing shrinkage due to the industrialization. Other towns in the area, like Binghamson, which I visited yesterday, and Corning just down the road, seem to have navigated this transition between the industrial and the post-industrial with more agility.

Pro-abolition potholders from the mid 19th century. Chemung Valley History Museum

The Chemung Valley History Museum is filled with artifacts of Clemens, of abolition, of proud memories of an amusement park not far from Woodlum Cemetery that closed in the 1980s. But the last plaque in the museum describes Elmira after the 1972 flood as a city “poised for growth”, a polite way of noting that the growth in question is yet to come.

But on the edge of town is a white farmhouse built from the boards from a Confederate prison camp by a man who escaped slavery, who bought his farm with money earned from burying, with care and dignity, the bodies of men who fought to enslave him. The nine layers of wallpaper and rags created a warm spot in the Elmira winters for a man who helped over eight hundred enslaved people find their freedom. Cleveland, the museum docent, explained that Confederate family had come in wagons after the war to take their dead home. They assumed they had been dumped in graves by the Yankees, as Union soldiers had been in the South. They found the carefully carved wood and markers and the well-tended grave sites that Jones, living across the street, had maintained and decided to let their dead rest in peace.

The post Roadtrip: Buried, with dignity, in Elmira appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 9, 2024

Roadtrip: A Square Deal in Binghamton

Binghamton, NY, seat of Broome County, NY

Population 48,000

Peak population 81,000 in 1950

Former home to Endicott Johnson (shoes), major IBM plant

Now home of Binghamton University

Housing/Income ratio: 2.4 (10 of 384)

+0.46% net international migration, -1.37% population growth 2020-2023

78% white, 11% black, 6% hispanic

Severe flood, Moderate fire, Minor wind, Minor air, Moderate heat (4,2,1,1,2)

(Major flood in 2011.)

Binghamton held a place in my mind for years as “that city I didn’t go to”. When I was in high school, SUNY Binghamton – now Binghamton University – was the best of the NY state schools, the school I hoped to be accepted at if I didn’t get into my first choices. I got into Williams, moved to western MA and didn’t think about Binghamton for years until I started passing through on my various “rustbelt rambles”.

The American Legion, west Binghamton, NY

The main thing I noticed on those brief visits are the massive mansions in the city’s downtown, at least one available for fire-sale prices, if you happened to have thousands of spare hours to fix the place up and a huge family to fill it. I learned today that Binghamton has been called “The Parlor City”, referring to the opulence of private homes built with revenues from the many manufacturing activities that took place in the city in the mid to late 1800s. Located on a navigable river connected to the Erie canal in 1837 and to rail in 1849, Binghamton manufactured a little bit of everything: cigars, sleighs, carriages, washing machines, leather tanning.

The Phelps Mansion, now open as a history museum, was built in 1870 for Sherman Phelps, a businessman, banker, judge and mayor of the city. When constructed, the mansion was part of a whole row of opulent houses, owned by the manufacturing and financial elites of the time, but those mansions decayed as that first era of Binghamton’s manufacturing waned. The Phelps Mansion survived by becoming the clubhouse for prominent local ladies, who invited speakers like Amelia Erhardt to share with the local community. It remains an active community center, as well as a museum – there was a lively stage magic camp for elementary school children in the ballroom when I came by today.

The mansion that captured my attention, though, was the home of Harlow Bundy, the elder of two brothers who created a manufacturing company that was, arguably, the direct precursor to IBM. Harlow’s brother Williard was a brilliant jeweler and invented a clock that could keep track of when employees came to work. Harlow saw the potential of the invention and brought his brother to Binghamton, where there were skilled manufacturers who could scale up production. The two built the Bundy Manufacturing Corporation, which morphed into the Simplex Time Recorder Company, which was a major building block in International Business Machines, which was initially headquartered in Binghamton. Unfortunately, the brothers fell out in a dispute over patents and briefly had rival timekeeping companies.

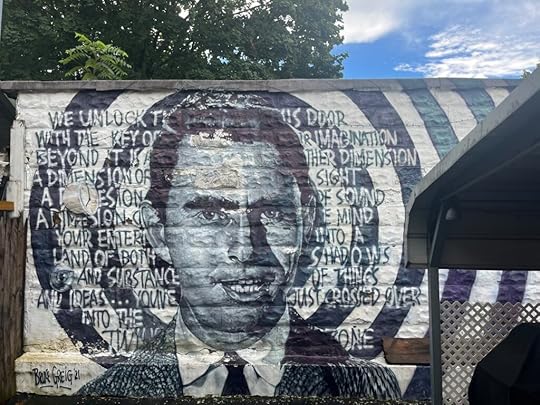

Mural of Rod Serling at the Bundy Museum

Harlow’s mansion and nearby homes have been turned into a fantastic showcase for art and objects of Binghamton’s past and present. Walk through a gallery of early timeclocks, which show a remarkable range of methods to ensure employees showed up to work on time, and you’ll discover a shrine to Rod Serling, screenwriter and producer of The Twilight Zone. (Serling lived nearby in his childhood.) The top floors of Harlow Bundy’s mansion are given over to galleries for local painters and photographers, and the complex as a whole houses a radio station, a darkroom, a coffee shop (filled with the fixtures of a local barber shop) and a small live music venue. It’s the passion project of a local antique collector and other Binghamton boosters, and it’s an elegant illustration of a truth of undervalued cities: when property is cheap, you can afford to be creative with how it gets used.

A photo in the Bundy museum captures the intersection of two giant parts of Binghamton’s industrial success in the first half of the twentieth century: a line of workers are waiting to punch in on a Bundy clock before starting their shift at Endicott Johnson, the shoe and bootmaker who produced all the boots used by the US military in both World Wars. Fourth in line is George F. Johnson, factory foreman and co-owner of the company, who invented an early version of “welfare capitalism” with the “square deal”. The deal included healthcare from the factory, financing to buy homes, and an impressive array of recreational facilities, including libraries, theaters, swimming pools and six carousels in Binghamton and surrounding towns. One of the most storied facilities is the En-Joie golf club, designed to be accessible to factory workers – one poster featured in the Harlow Bundy mansion explained that when Johnson learned that workers were worried about losing golf balls and having to buy new ones, he designed a course that’s virtually impossible to lose a ball on.

There are two arches, built in 1920, with money donated by the workers to celebrate “the square deal”. I’m skeptical. But I love the golden arches peeking out beyond this one on the Endicott border.

There was a cult of personality around Johnson that seems part charming and part… disturbing? In 1916, Johnson instituted an eight our workday, which led 25,000 employees to visit Johnson’s house personally to thank him, bringing beer, clams and a band to celebrate. There are two arches – one currently taken down for road construction – built between the cities of Binghamton, Endicott and Johnson City by workers to celebrate Johnson’s square deal.

While the profit-sharing, corporate healthcare and fair working hours are laudable, at the end of the day, Endicott Johnson paid fairly modest wages for demanding piecework, and to a large extent, the “square deal” was meant to ensure that laborers didn’t unionize. Many workers were immigrants from southern Italy and the Balkans, and while their earnings put their children through high school and sometimes college, most of the children didn’t return to the factories alongside their parents. (I explained the model of healthcare, golf and carousels to a friend who works in the Bay Area, to which she relpied, “Oh, that’s where Apple got the idea.”)

iM3ny factory, Endicott, NY

Endicott Johnson exists only as a brand of a minor shoemaker today, and most of its factories are torn down, but Bundy, absorbed into IBM, thoroughly transformed the workplace, making “Fordism” and “scientific management” possible by ensuring the presence of countless factory workers on the assembly lines. Endicott, one of the three cities hosting EJ factories, now has the iM3NY lithium battery “gigafactory”, which occupies a large part of the city, but which is having problems finding sufficient investment to scale up production.

The pinball tables at Robot City Arcade

Endicott itself seems to be where the region’s immigrant population is settling – the main street features Halal markets and Bengali restaurants, while the West Side of Binghamton itself seems like the cool place to try out a new business, like Parlor City Vegan, or the wonderful Robot City Arcade, which features historical game consoles for sale and a back room filled with pinball and arcade machines.

The city’s downtown is beautiful, blessed with architecture that’s survived the shift from sleighs and cigars to army boots, to life as a university town. There’s evidence of businesses trying and failing – a shuttered brewery, some empty storefronts – but equal evidence of success, and the overall vibe (to the extent that one can gather such things in a short visit), is a city where transformation is possible.

Oh, and there’s spiedies. Don’t forget to have a spiedie.

Thanks, Binghamton, I’ll be back. And thanks to the ladies who preserved a mansion in 1905, the first time the city’s economic fortunes changed, to the folks building in the wake of EJ, Bundy and IBM, and to the people making Binghamton their home today.

The post Roadtrip: A Square Deal in Binghamton appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 6, 2024

By the numbers: what statistics can and can’t tell you about “undervalued” cities

What can you tell about a city from the numbers?

I’m about to spend two weeks engaging in one of my favorite passtimes – driving to unfamiliar cities and attempting to “figure them out”. Why is this city where it is? Is it growing or shrinking? Where do people work? What do they do for fun? And most importantly, where should I eat?

I’ve gotten into the habit of pulling up certain statistics when I visit a new city – the first thing I do is scroll a city’s Wikipedia entry to its “demographics” tab. I want to know whether a city is growing or shrinking, and I particularly want to know when its peak population was. A city that peaked in the 1900s (North Adams, MA) feels really different from one whose best days were in the 1960s (Pittsfield, MA, my hometown.) And both are distinctly different from cities that are still growing, and particularly from those whose greatest period of growth is recent.

As I head off on my road trip, I’m compiling mini-dossiers on the cities I’m heading towards. I’m bringing together a few different data sets – Wikipedia gives me peak and current population, and some key facts about where people work now and where they used to work. I’m organizing the trip around the median house price/income ratio, so that comes in including ranking in terms of all 384 metropolitan statistical areas. This wonderful US Census site gives me the racial breakdown and the percentage of population that’s foreign born, which helps me figure out whether a city is attracting immigrants. And First Street Foundation’s Risk Factor offers climate risks in five categories: flooding, wildfires, wind (hurricanes, tornados, derechos), air quality and heat. (Each of those risks runs from 0-5, so I think of the aggregate risk as being out of 25.)

As for the critical questions of where to eat and what to see, that one’s harder. I look at Yelp, Trip Advisor and Google Maps, but trust all of them less than local restaurant guides, or specialized sites like Eater. (Their Berkshire county guide isn’t perfect, but it’s damned good.) I’m particularly interested in what I call “statistically improbable restaurants”, i.e., restaurants that feature a cuisine not normally seen in a small city. A Burmese joint in NYC doesn’t mean anything, but a Burmese restaurant in a city of 40,000 likely means a well-established Burmese immigrant community.

I tend to hit up Atlas Obscura and Roadside America for possible destinations, as well as Trip Advisor.

But it’s obvious that numbers don’t tell the whole story, which is why it’s worth taking road trips. I’m trying to be conscious that these data points are designed to help me know what to look for, and trying to make sure they don’t blind me to what’s worth seeing.

So, here’s a test, using a city I know very well.

Pittsfield, MA, seat of Berkshire County, MA.

Population 44,000. Peak population 58,000 in 1960 (Currently at 76% of peak population)

Formerly home to GE’s High Energy laboratories, GE Plastics

Now a regional center of culture and tourism, healthcare as major employer

Housing/Income ratio: 3.9 (155 of 384) – very low for New England

+0.45% net international migration, – 1.75% population growth 2020-2023

88% white, 5% black, 6% hispanic. 6.8% foreign born

Climate risk: Moderate flood, Moderate wildfire, Moderate wind, Minor air, Minor heat (2,2,2,1,1 – 8/25). Ongoing cleanup from PCBs from GE transformer manufacturing

Attractions: Hancock Shaker Village, Arrowhead (home of Herman Melville), theaters, museums

Food: La Fogata (Columbian), Dottie’s, Brazzuca’s market (Brazilian)

(Several reviews mention mini-hot dogs as a local cuisine.)

These dogs are from Teo’s, though I am partial to the Hot Dog Ranch. In any case, they are ordered “with everything”, which means meat sauce, mustard and chopped onion. Why? Dunno, don’t care.

And here’s a more personal take, from a blogpost I started writing, attempting to introduce this series/road trip. I was wrestling with the idea of “unfashionable cities”, a term I’m experimenting with to refer to cities that, for whatever reason, are not places people are excited to live in. (I’ve thought about “value cities” as well, but “value” like “fashion” is a complex and multifaceted term. “Bargain cities” or “undervalued cities” can feel demeaning, even if there’s some truth to the idea that these cities are very good value for the money. I’m still working through it.)

Pittsfield, MA describes itself as “the heart of the Berkshires”, a scenic stretch of western Massachusetts blessed with beautiful scenery across all four seasons, a wealth of music, theater and dance festivals, world-class art museums and educational institutions. I have lived here since 1989 and – despite many opportunities to move away – I plan to be buried here. But I appear to be the exception, not the rule.

General Electric based its transformer division in Pittsfield from 1907 to 1987, a major center of research and development, a “crown jewel” for the massive and powerful company. At the peak of GE’s presence in Pittsfield in the 1940s, 13,000 of the town’s 50,000 residents worked for the company. GE’s presence attracted defense contractors and other manufacturers and the city’s population peaked in the 1960s at just shy of 58,000.

It’s been downhill since, population-wise. Pittsfield’s population has shrunk in every subsequent decade and now stands at roughly 43,000. When GE closed the transformer division in 1987, it not only knocked out a major pillar of the local economy, it left much of its former footprint – and the Housatonic River – contaminated with carcinogenic PCBs. GE’s presence in the area while I’ve lived here has mostly centered on environmental cleanup.

It’s easy to understand how a city that lost its biggest employer and gained a brownfield might have a bad reputation. In the 1990s and 2000s, Pittsfield was a national leader in teen pregnancy, documented in Joanna Lipper’s Growing Up Fast. Fentanyl is a serious problem now, with one of the highest overdose rates in the state. (The rates are higher in the unfashionable cities of Fall River and Springfield, two cities that have similar histories of deindustrialization and shrinkage.) For a few years in the early 2000s, anyone driving into the city from the north was greeted by a giant sign in front of a shuttered liquor store that read “Fuck You Pittsfield”, presumably a parting shot from a failed businessman.

Brazzuca’s. Rapidly becoming one of my favorite lunch places on North Street.

But Pittsfield is turning around. A wave of immigrants have opened new businesses on North Street, once filled with vacant storefronts. Within a mile downtown, you can find Brazilian, Salvadorean and west African markets, as well as Colombian, Dominican and Caribbean restaurants. (The liquor store that once sported the unfortunate sign is a Hispanic market, run by a Venezuelan immigrant.) The once-shuttered Colonial Theater reopened in 2006 and hosts performers from around the world. A boutique hotel sited in two 1880s brick buildings anchors the opposite end of the street from the Colonial. A new economy is slowly emerging around the arts, medicine, and precision manufacturing.

One thing Pittsfield has done well is to shrink responsibly. The city had several distinct shopping areas in the 1960s and 1970s, but it can’t support multiple “downtowns” at this point. For the past couple of decades, the city has been encouraging businesses to occupy real estate on North Street, the main downtown street, in part through a once a month festival that lines the street with food carts and performers. There are empty storefronts in the city, but far more so in the outer commercial areas, and few on the main drag.

One of the many murals that’s blessed North Street in the last couple of years, this one tucked away by the freight tracks.

In addition to an increasingly lively downtown, Pittsfield is incredibly well cited. It’s surrounded by beautiful rural areas in all directions, with hiking trails, lakes and ski areas all nearby. There’s a long tradition of summer arts festivals in the region, including the Jacob’s Pillow dance festival, the Tanglewood music festival and two top theater festivals. The Clark Art Institute, MassMoCA and the Norman Rockwell anchor a set of world-class museums. It can feel at times like Pittsfield is an afterthought to some of these regional destinations, with people passing through to see the cultural treasures of the area. But Barrington Stage is selling out shows in downtown Pittsfield and the beautifully restored Colonial Theater is attracting national touring acts.

Yet Pittsfield remains a comparatively unpopular place to live. It’s one of only five metropolitan statistical areas (a census designation for a city or town and the set of suburbs and economically connected communities around it) to have become a better deal over the past thirty years. While it makes sense that a city which lost its largest employer and has shrunk significantly would become a cheaper place to live, it’s also a bit of a surprise. Some similar communities closer to New York City gained lots of urban refugees during the pandemic, raising real estate prices and goosing local economies. Pittsfield is a bit too far north, too far from train lines to make a trip into Manhattan easy to accomplish. And while the Boston suburbs continue to increase in density and expense, there’s no sane way to commute from the Berkshires to the Boston area, something I say with confidence after doing it for seventeen years.

Like a lot of the cities I’ll be visiting on this trip, Pittsfield needs to be understood in terms of its past: it was one of the centers of gravity for GE, and every inch a company town, and now it’s not. There’s a hope for a patchwork of smaller employers to fill the gap, but it’s harder to answer the question of “Why is there a city here?” than it was half a century ago.

That leads me to an animating question for this trip: what happens to a city when the reasons for it change? Lots of cities pivot – the loss of gold prospecting isn’t a major obstacle to San Francisco’s success, and it’s been a long time since the coastlines of New York City were lined with shipping docks and garment factories, yet those cities have settled comfortably into their new identities. Cleveland, blessed with coal and iron ore, a navigable river and Lake Erie, still remains a manufacturing town in many people’s minds, even though the auto parts manufacturers moved out long ago, and an economy around healthcare and banking has taken hold. The generation for whom Pittsfield was about GE is dying out, and it’s being replaced by people for whom the city is an inexpensive (by New England standards) place to build a family and find a foothold. How will they – we – think of Pittsfield some decades from now?

The post By the numbers: what statistics can and can’t tell you about “undervalued” cities appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

July 31, 2024

Road trip! Driving by data set

The road trip is a cultural rite of passage in the US, and there’s countless ways to organize your path across the country. You can follow a famous road, Route 66 through the west, the Pacific Coast Highway, or Route 20 across the north. You can chase a theme, following the Blues highway, or just blue highways, the minor roads that criss-cross the rural parts of the nation. You can seek out the best BBQ, or follow the tamale trail.

Me? I like to start a trip with a data set.

I’m interested in why people live where they live, and a major component of that question is “where can I afford to buy or rent a house?” There’s a simple statistic that summarizes whether a housing market is relatively affordable: the average years of median income required to by a median home. Because both aspects of the ratio are calculated locally, it helps balance questions of how lucrative employment is with differences in local costs of living. Throughout the 1990s, this ratio averaged 3.2 across the US. In 2022, it peaked at 5.1 – in other words, it would require more than five years of median salary to buy a median home. The ratio is down slightly now to 4.9, but it’s a massively different market for homebuyers now than when I bought my house in 1998.

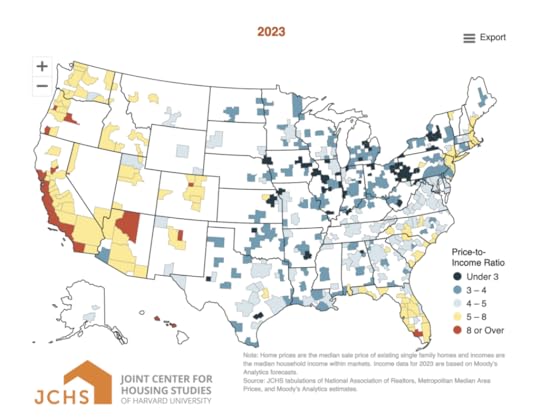

While home prices are up almost all across the nation, there’s enormous variation from one city to the next. And so the data set I’m planning my road trip around is from the 2024 State of the Nation’s Housing from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard.

In the map above, yellow and red represent expensive housing markets, with price/income ratios of 5x or higher. Many of the major cities of the east and west coast are predictably high, with all of coastal California at 8x or over. But so are some of the growing cities of the mountain west, including Denver/Boulder, Salt Lake City and almost all of Arizona.

Now let’s look at the dark blue. With price/income ratios of under 3, these are the bargain cities. A very few of them are in states experiencing growth: Odessa, Texas has had boom and bust cycles around the oil industry, but it’s grown enormously in the past decade and yet is still cheap. But most of the dark blue is in the Midwest and upstate New York, the “rustbelt”, a part of American I’ve long been fascinated with.

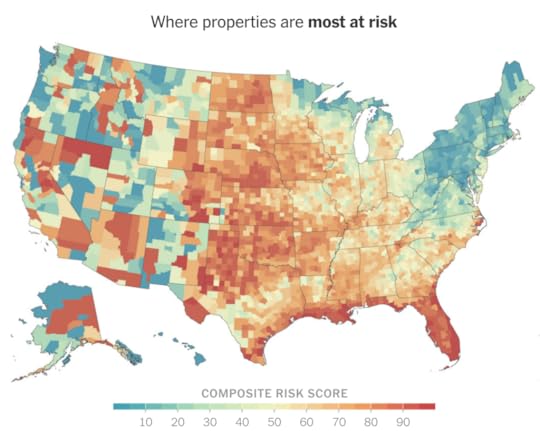

Here’s what most interests me: many of the cities where houses are expensive are cities facing serious climate challenges. Consider Naples, Florida. It’s one of the most expensive MSAs (Metropolitan statistical areas – Census-speak for “a city and its environs”) with a price to income ratio of 9.4. But even if you can afford that house, perhaps you shouldn’t buy it. Naples has “extreme” risk for flooding, wind and heat, the highest level of risk in models developed by First Street Foundation, a company that models environmental risk for US properties.

Composite risk map from NYTimes, generated using data from First Street Foundation. See https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2...

By contrast, many of the most affordable cities are pretty climate resilient. Utica, NY – one of my favorite rustbelt cities – is a bargain at 2.8 price to income, and there’s a pretty good chance your house will survive the next few decades. Utica is at moderate risk of flooding, heat and fire (the third of six levels on First Street’s scale), minor risk for wind damage and air quality. And unlike in Florida, there’s a decent chance you can afford to insure your home.

Many of these climate resilient, high affordability cities are shrinking while more expensive and climate fragile cities are growing. There’s a long, complex story behind that which includes not only deindustrialization but also a campaign around the idea of “growth cities”, cities with low taxes, low services and right to work laws, designed to limit the power of unions. (Barry Goldwater comes into it, too.) But that’s a book chapter, not a blog post.

Why are these cities so inexpensive? Why are some of them shrinking? There’s a simple, straightforward hypothesis – maybe these just aren’t very good places to live. But I’ve been to several of the cities that rank high on this list and I like them a lot. Indeed, I live in a city that’s well below the median in terms of price to income ration – the Pittsfield, MA area is 3.9, the second least expensive in New England. (We come in just behind Bangor, ME, which is also a really lovely little city.) It’s a great place to live.

Gateway cities map, from Brookings Institution report, 2007

In 2007, Massachusetts was trying to figure out what to do about cities like mine, who were falling well behind Boston in the state’s “Massachusetts Miracle”, a comparatively rapid transition from manufacturing to “knowledge-based” industries like tech and pharma. Cities like Pittsfield, Worcester and Lowell lost jobs as Boston gained them, and while these mid-sized cities had 15% of the state’s population, they had 30% of the state’s people living below the poverty line.

A study conducted by the Brookings Institution suggested thinking of these cities as gateways into America for new citizens. Maybe someone who’s just come to the US won’t stay in Pittsfield forever, but it’s a great place to find an inexpensive place to live, to learn English, to build up some work experience. Lawrence, MA has been entirely transformed by immigration – the former mill town is now 82% Hispanic, 43% foreign born, New England’s first “majority minority” city. It has not always been an easy road – there was racial violence in the city in 1984 between Spanish and English-speaking residents. But Lawrence is growing, the mayor and the majority of City Council are hispanic and the city exemplifies its long history as an immigrant city. Could these affordable, climactically-sustainable cities become gateway cities, welcoming migrants who’ve been forced to leave their countries due to climate change?

I’ll write more about gateway cities as I travel. The concept is both compelling and problematic – it’s not clear that the cities identified have been more appealing to immigrants than large, job-rich cities like Boston. And early data suggests that gateway cities in MA haven’t been as successful in helping families escape poverty as Boston… though MA in general is much better than most American cities in helping people escape poverty.

So one of the other questions I’ll be asking on this trip is whether the cities I’m visiting are good ones for immigrants. Sometimes it’s pretty easy to make guesses from numbers. Utica, NY has developed a reputation for a population rebound based on immigration, particularly Muslim immigrants from the Balkans, the Middle East and now Myanmar. While 13.7% of the people living in the US were born in another country, those immigrant populations tend to cluster in large cities where there are neighborhoods with familiar foods and people who speak the same language – Miami’s population is 57.9% foreign-born, New York City is 36.3%, LA is 36%, Houston is 28.9%. So when you see a small city (Utica’s population is about 64,000) with 22.2% foreign born population, something interesting is going on. I’ll be looking for cities that have already attracted immigrant populations and looking for signs of their impact on the cities, particularly via restaurants and grocery stores, my favorite paths into exploring a city.

So where am I going? Some – though probably not all – of the following cities:

#10 Binghamton, NY

#22 Elmira/Corning, NY

#19 Youngstown, OH

#30 Akron, OH

#27 Canton OH

#33 Lima, OH

#9 Terre Haute, IN

#1 Decatur, IL

#4 Springfield, IL

#3 Peoria, IL

#12 Davenport, IA

#11 Rockford, IL

#44 Michigan City, IN

#24 Battle Creek, MI

#31 Toledo, OH

#40 Erie, PA

#41 Syracuse, NY

#29 Rome/Utica, NY

Those rankings are by median home price/income ratios – Decatur, IL is the only American MSA under 2x, with a 1.9x. The census puts median monthly home ownership costs, which include mortgage payment, real estate taxes and utilities at $1,112 ($1,828 is the median across the country.) Central Illinois leads the nation in cheap housing, with Peoria and Springfield also in the top 5. (Danville, IL is #2, but slightly outside the loop I currently have planned.)

I’m making detours to see friends in St. Louis, Bloomington and Cleveland, and to see art and architecture… but some of the art I most enjoy is in cities within the dataset criteria. I’ve already made detours on other roadtrips to see the absurdly wonderful collection of mid-century American paintings at the Swope Art Museum in Terre Haute, the ambitious and forward-looking shows at the Figge in Davenport, IA and the world-leading glass museum in Corning, NY.

So I know for a fact that some of the towns on this list are cool places where I’d enjoy spending more time, and possibly relocating to. I’m hoping the trip – which will necessarily be impressionistic, too brief in any city to get more than an initial feel for a place – will help give me some insights into what’s holding these places back, what problems they might have in common.

I’m a planner, as you might have gathered from an itinerary governed by spreadsheets. But I’m trying to approach this trip with more flexibility than I usually give myself, in part because if I try to reach all these cities in the time I have (about ten days), I’ll make myself miserable. So – I’m going to Decatur, and several of the other cities above on the way. If you’ve got suggestions of things I should see or do in the cities listed above, or places nearby, please offer them up. And while suggestions are great, warnings are not – it’s my sense that a lot of the cities I’ve come to love (I’m looking at you, Cleveland!) are still shaking off the stereotypes of decades past. I’m less interested in whether it will play in Peoria than in what that city looks and feels like now.

I’m setting off on August 9 and will be posting regular updates here and on social media, mostly photos and reflections from the road, but some longer essays as well. Wave if you see a Toyota Prius with MA plates and the front bumper falling off.

The post Road trip! Driving by data set appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

May 9, 2024

A brief update on Zuckerman vs. Meta

I’m getting good practice this week talking about something complicated: the lawsuit the Knight First Amendment Institute and I filed against Meta a week ago today. On Sunday, the New York Times published a guest essay I wrote about the suit, and I dedicated my regular monthly column at Prospect to explaining loyal clients, the idea that we deserve internet tools that represent our interests as users, even when they conflict with what a powerful platform wants. (Cory Doctorow wrote a great piece yesterday on loyal clients that intersects with the Meta case and other ideas he and I have been following, including adversarial interoperability.)

In the past few days I’ve had conversations with very smart reporters who’ve worked to put the suit in context. Will Oremus, writing for the Washington Post, uses the case to talk about the broader idea of middleware, citing my single favorite middleware example, Tracy Chou’s Block Party (now suspended, due to Elon Musk being, well, Elon Musk.) Ashley Belanger, writing for Ars Technica, talks to a variety of knowledgeable lawyers about the novel arguments we’re making about section 230. It’s fascinating for me to see how these arguments are landing with knowledgeable audiences.

Meta should be responding to our complaint in the next couple off weeks, and I promise an update then. In the meantime, if you’ve not read Louis Barclay’s very sweet seven thoughts on our suit, please check it out – I am now pronouncing Louis’s name correctly as a result!

The post A brief update on Zuckerman vs. Meta appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

May 2, 2024

Zuckerman vs. Meta Platforms

On Wednesday morning, the amazing and brilliant lawyers at the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University (K1A) – primarily Ramya Krishnan and Alex Abdo – filed a lawsuit on my behalf: Zuckerman vs. Meta Platforms. This is a federal lawsuit, filed in the northern district of California, and it seeks “declaratory judgement” – basically, a ruling from the court that a research study I propose to conduct won’t break laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

The research is pretty simple: In 2021, UK-based programmer Louis Barclay built a browser extension called “Unfollow Everything” (UE). If you chose to use it, UE would step through the friends you have on Facebook and the Pages you follow, and, well, unfollow all of them. This would render your Facebook feed either empty, or uselessly filled with spammy recommendations. One way or another, Barclay reasoned, you’d probably use Facebook less, and use it the way you might have before 2005 – going to a friend’s page and seeing their updates.

Meta wasn’t a fan of Louis’s work. They banned him for life from their platforms and demanded he cease and desist distributing his tool. I asked the court whether I could build a new, up-to-date version of UE (Unfollow Everything 2.0), with more privacy preserving features, and do an opt-in study where participants could see whether using UE2 reduced their use of Facebook, increased their sense of control over Facebook, and increased or reduced the diversity of the people they interacted with.

Because Meta prevented Louis from distributing UE, we think it’s reasonable to ask a court to rule on whether we can release a very similar tool. We believe we can, based on our reading on section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, specifically section (c)(2)(B), which states that it is the policy of the United States “to encourage the development of technologies which maximize user control over what information is received by individuals, families, and schools who use the Internet and other interactive computer services”. If a court agrees, we think this may open up a channel for developing a category of software that Francis Fukuyama and friends call “middleware”, software users can install to have greater control over their social media experience.

(Alex Abdo just posted a Twitter thread that offers a more detailed overview of the case and our legal strategies.)

I’ll be sharing more writing about my motivations behind this suit in the next couple of days. In the meantime, I’m really enjoying watching smart people talk about whether they think this suit could work.

Writing for Wired, Vittoria Elliott talks to a wide variety of legal experts, who have a range of views on whether this could work. Barbara Ortutay, writing for AP, focuses on the idea that we might want more control over our social media than we currently have.