Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 5

April 19, 2024

Twitter’s New Business Model: Russian Disinfo

I’m at an event today at UMass Amherst put together by colleagues to launch the new initiative, GloTech, which focuses on perspectives on technology and media from the Global Majority. I’m thrilled to be a senior fellow with GloTech and to lend a hand today with moderating a panel on elections around the world, and the role of mis/disinfo and foreign influence in global elections.

So my mind is on questions of election interference. And that’s a helpful frame with which to explore X, Elon Musk’s transformed Twitter, which has moved from being a space that carefully labeled misinformation and foreign influence operations, to one which now relies on Russian propagandists as a key advertiser.

Here’s the ad, which had received over 300,000 impressions by the time I saw it last night:

From a casual glance, you can see that the advertiser, Truth In Media, is blue-check certified, a marker that used to indicate that a user was a verified journalist or other public figure, then signified that the user was an Elon Musk fanboy, and now that Twitter has been returning blue-checks to popular accounts, now is a deeply ambiguous signal. @Truth_InMedia has over 80,000 followers, but follows 37 accounts, and those accounts suggest the possible politics for the account. They include notorious Internet troll @catturd2, QAnon-aligned felon and general Mike Flynn, far right heroes Dinesh D’Sousa and Lara Logan, and finally, Ben Swann.

Who’s Ben Swann? He became a news presenter in El Paso in the late 1990s, migrated to Cincinatti and eventually to Atlanta, where he worked for CBS’s Atlanta affiliate. Between his time in Cincinatti and Atlanta, he worked for RT America, the propaganda outlet owned by TV Novosti, an “autonomous non-profit organization” founded by the Russian state owned newsagency, RIA Novosti. While in Cincinatti, Swann began a segment called “Reality Check”, which sometimes featured alt-right conspiracy theories, and started a website called Truth in Media, which covered similar subjects. In 2017, “Reality Check” addressed the Pizzagate conspiracy, which led to station management demanding Swann take down his Truth in Media site and social media accounts. When Swann restored Truth in Media, the station fired him, and Swann returned to RT America.

Since his departure from the broadcast airwaves, Swann has strengthened his financial ties with RIA Novosti, taking $5 million in funding to produce 50 episodes of 4 shows. The shows Swann agreed to produce focus on themes popular in Russian propaganda: “the United States and NATO continuing to spread war around the world,” “the economic warfare waged by the United States and its allies,” and “transgender issues in the United States”, according to reporting by Axios. When Swann was asked by the DOJ what he knew about TV Novosti, he said “I believe that TV Novosti is an autonomous organization but it does receive funding from the Russian government through the Russian Federation.” Axios reports that TV Novosti in fact received roughly half a billion dollars from the Russian government in 2022.

So: the ad above presents a “documentary” narrated by an American conspiracy theorist who’s been thrown off broadcast media for promoting falsehoods like the Pizzagate conspiracy. The documentary is consistent with themes he’s been paid by a Russian government agency to produce, and it directly amplifies Russian-government talking points about Ukraine. This is paid Russian political propaganda aimed at right-leaning US audiences, designed to undercut US government support for Ukraine, found in the wild.

There was a time in the not-too-distant past when Twitter worked hard to label government-sponsored media outlets. Then Elon decided to troll NPR by labeling it state-affiliated media, before deciding to remove these labels altogether. Not only is state-sponsored media allowed on Twitter without labels now, government disinfo is now a revenue source for Musk’s failing social network.

There’s lots to worry about in 2024 from the troubled information environment we face. I am less worried about how AI will be used to create deepfakes than I am concerned about naked state propaganda like this documentary. While it took me only a few minutes to figure out who was behind this documentary, it’s certainly not clear on the surface. And there’s enough truth in the documentary – Zelenskyy is indeed very famous, is an unusual politician, and Ukraine does suffer from tremendous political and commercial corruption – that someone encountering this film without understanding the agenda behind it might consume it uncritically.

Influence operations like this are a BARGAIN for Putin. If more right-leaning politicians block aid to Ukraine, Russia is far more likely to win their expensive and bloody war. Swann may genuinely feel that Zelenskyy’s background deserves more investigation. But journalism demands transparency about funding sources and the agendas behind them. Twitter has made it clear that it’s no longer interested in preventing the spread of government disinformation so long as Elon shares the agenda in question, or perhaps so long as the propagandist is willing to pay enough.

The post Twitter’s New Business Model: Russian Disinfo appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

March 19, 2024

Pablo Boczkowski on the crisis in the “mental health capital of the world”

I’m in Paris this week – spring break for UMass – visiting my second-favorite university, SciencesPo. I’ve taken on a new responsibility with SciencesPo, with a new initiative – l’institut libre des transformations numériques de Sciences Po – where I am leading a board of stakeholders advising the project. To spend some time with my colleagues – and to enjoy somewhere slightly warmer than western Massachusetts – I’m spending the week at SciencesPo, enjoying both planned and chance encounters.

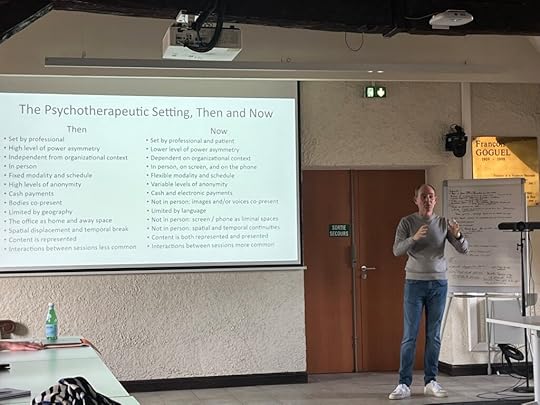

One of those encounters is with Pablo Boczkowski, a brilliant media scholar normally based at Northwestern University. Boczkowski has written extensively about how news is produced and consumed in a digital age. I had not realized that media theory is a second profession for Boczkowski – he trained and practiced as a psychologist in Buenos Aires before becoming a media scholar. That helps make this talk make more sense. Titled “Digital Freud: The Refiguration of Inequality, Society and Personhood in Clinical Practice”, it’s an overview of his new book, based on ethnography of mental health professionals in the city of his youth, Buenos Aires. Citing Gabriel Garcia-Marquez, he promises “A strictly accurate account that sometimes ventures into fantasy.”

The focus is on the adoption of digital technology by psychologists and psychiatrists, and focuses on Buenos Aires because it is – arguably – “the world capital of mental health workers”, if not of mental health. Boczkowski reports that there are eight times as many mental healthcare professionals, per capita, in Argentina than in the US. That concentration is particularly high in Buenos Aires, possibly three times of what might be found in smaller cities. Pablo argues that the rise of telehealth, the routinization of digital technologies and the widespread adoption of the mobile phone represents “the first major socio-material transformation in the profession in more than a century.”

Why focus on the mental health field? Already, one out of eight people worldwide report problems with mental health. After COVID, as many as 1.5 billion people may be experiencing mental health problems. Boczkowski’s argument is not that tech is causing these problems (he refers to that as the Jonathan Haidt’s position) but that the changes brought about within the mental health field may help us understand some broader transformations around technology, civics and society as a whole.

Two stories run through Boczkowski’s talk – one is his personal story of return, visiting the hospital where he first practiced. The second is the tragic death of Jorge Marcheggiano, a seventy-year old patient of a state mental hospital who was killed by a pack of wild dogs when walking in a courtyard at his hospital. The failures of technology to protect Marcheggiano, the overwhelmed systems that failed him help motivate Boczkowski’s exploration of these questions.

In many ways, the environment of the mental health office is unchanged – treatment rooms with bare walls and two chairs still dominate the setting. But actually the setting has changed radically, particularly during COVID. The 19th century model of psychology, where the therapeutic setting is set by the professional, where he or she has the “home court advantage”, was utterly upset by the new rules of a digital, post-pandemic world.

Adapting to the pandemic meant that one therapist reported doing a couple’s session with the woman in a car, the man in the house and the therapist in a third location, something that she would never have allowed to happen before this digital shifting of time and space. Patients no longer have a travel to the doctor’s office to think about what to say, or a return to process what’s been said and heard. Instead, you move from real life into a session seamlessly. And even when mental health professionals try to maintain distance from their patients, anonymity is much less possible. The Zoom window is an insight into a patient’s home, circumstances, class, situation… and vice versa.

The therapist used to be a fairly anonymous figure. Now, if you are even modestly active on social media, your life is wholly visible to your clients. They know what your kids are into, and when your birthday was… and they may expect you to keep up with them in a similar fashion.

The changes from the rise of the digital are not just incidental. The professionals Boczkowski interviews report that their patients now come to sessions with “evidence” – text messages that show the dynamics of a relationship, recordings of a family dinner that show a family member’s behavior.

The phone can be a space for bonding and connecting with young patients in particular – some of Boczkowski’s interview subjects document trading memes with their patients, or having conversations with patients about whether the “stickers” they use in text messages are lame or up to date.

The most profound changes are around time: psychiatrists, in particular, report being deluged with requests for prescriptions – and not just mental health medications – at any time if they’ve shared their mobile phone numbers with patients. (Psychologists report less concern about contact between sessions, and more about distraction during sessions with phones and social media. This may be because psychiatrists face a massive caseload – 300-400 patients contacting you for prescriptions could be overwhelming, while a psychologist might have 50-100.)

(I’m extrapolating slightly from Boczkowski’s remarks here and might be getting it wrong. He references class as another factor in the boundaries between professional and private life. Many psychologists work 30/hrs a week for state hospitals or other institutions, making very little money, and then work with individual clients in private practice. I get the sense that sharing one’s mobile number started with private clients, and may be less common sharing with patients at the public hospitals.)

While there’s a temptation to reinstitute the strict boundaries between work life and private life, there’s good reasons for some permeability. An interview subject tells Boczkowski about caring for a patient experiencing domestic violence who had to reach out 3-4 times a week. While this might be seen as a major demand on a therapist’s time, it was also what this woman needed during crisis, and her therapist was able to help her leave her home and get to a safe place. The strictness of separation between the personal and the professional has always been more for the professional than the patient. (Boczkowski points out that Freud’s couch was instituted not for therapeutic reasons, but because Freud hated being stared at by patients for hours a day.)

There’s a dark note throughout the talk, with both the story of the patient killed by wild dogs, and

the rise of depression. One interview subject observes that by 2050, the WHO has estimated that depression will be the main cause of morbidity on the planet. Why? As the interviewee puts it, “We have utterly failed to design a world in which we can all live.”

Mental health professionals deal with the failure of our world with three techniques: reification, justification, and sometimes, reparation. Reification accepts the troubled state of the world as a self-evident given. Justification attempts to explain away the status quo as the function of different schemes of work, an understanding of unfairness and inequality through effort or skill. Some therapists find themselves attempting to repair, donating services like Wifi plans or cellphone service to patients, trying to supplement the state’s deficiencies, in part so they can continue helping their clients. These interventions are pragmatic, not ideological.

In the final minutes of the talk, Boczkowski makes a number of leaps that I find fascinating, but worth interrogating closely. He suggests that the situation we’re experiencing with the transformation of mental health work in Argentina exemplifies a broader state of “demand rules”, a situation in which the individual prevails over the institutional system. These institutions fail to satisfy a demand that, in many ways, is impossible to satisfy – this demand to be heard, to be healed, not just personally, but a healing of the world. When this demand cannot be satisfied, it is no wonder depression is on the rise.

We are experiencing new ways of being in the world, which Boczkowski refers to as “deregulating personhood”. We are always available, always on, we are exhibitionists as mediated by social media. This world rewards flexibility, pragmatism and improvisation. It demands limited balance and boundaries between work and personal life.

Associated with this shift, Boczkowski – and those he interviews – see a desire for immediate gratification and low tolerance for frustration, anxiety and loneliness. When people encounter these feeling they have low tolerance for, they can react with intolerance, extreme views and polarization. We are therefore experiencing the re-regulation of the political as well as the personal, seeing a rise in extreme ideologies and the rise of individuals who embody this intolerance and extremism, like Javier Millei (or, I suspect Boczkowski might agree, Donald Trump.)

I questioned Boczkowski about causality: do we see these changes in society as caused by the sorts of digital shifts this research documents, or do we see those shift accompanying a rise in both anxiety and depression from the collapsing environment, democracy under threat and the inequities of our current economic system? Boczkowski emphasizes that he doesn’t see the cause as technological, but is looking at a deeper pattern. He notes that distrust in democracy in Argentina is at an all time high, perhaps in part due to the persistence of marginalization for many communities. He suggests we see his work as bridging between the larger story of social transformation and the transformation of what it means to have a psychological consultation. “This book is not a causal story, but it is the experience of those trying to alleviate the suffering.”

Boczkowski notes, “The perfect storm is real – people are suffering and those treating them are also overwhelmed.”

I’m looking forward to the book, and particularly to hearing more of the argument around “demand rules” and how this might explain the broader global political moment. More than anything, I’m enjoying watching a scholar I’ve long admired pivot from familiar topics to the less familiar, in a way where he’s clearly energized by the new work.

The post Pablo Boczkowski on the crisis in the “mental health capital of the world” appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

December 22, 2023

How Big is YouTube?

How big is YouTube?

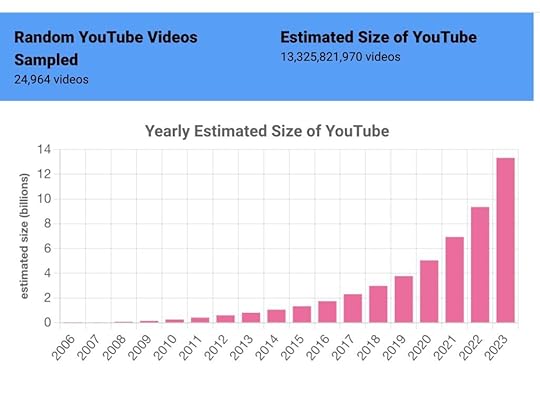

I got interested in this question a few years ago, when I started writing about the “denominator problem”. A great deal of social media research focuses on finding unwanted behavior – mis/disinformation, hate speech – on platforms. This isn’t that hard to do: search for “white genocide” or “ivermectin” and count the results. Indeed, a lot of eye-catching research does just this – consider Avaaz’s August 2020 report about COVID misinformation. It reports 3.8 billion views of COVID misinfo in a year, which is a very big number. But it’s a numerator without a denominator – Facebook generates dozens or hundreds of views a day for each of its 3 billion users – 3.8 billion views is actually a very small number, contextualized with a denominator.

A few social media platforms have made it possible to calculate denominators. Reddit, for many years, permitted Pushshift to collect all Reddit posts, which means we can calculate what a small fraction of Reddit is focused on meme stocks or crypto, versus conversations about mental health or board gaming. Our Redditmap.social platform – primarily built by Virginia Partridge and Jasmine Mangat – is based around the idea of looking at the platform as a whole and understanding how big or small each community is compared to the whole. Alas, Reddit cut off public access to Pushshift this summer, so Redditmap.social can only use data generated early this year.

Twitter was also a good platform for studying denominators, because it created a research API that took a statistical sample of all tweets and gave researchers access to every 10th or 100th one. If you found 2500 tweets about ivermectin a day, and saw 100m tweets through the decahose (which gave researchers 1/10th of tweet volume), you could calculate an accurate denominator (100m x 10) (All these numbers are completely made up.) Twitter has cut off access to these excellent academic APIs and now charges massive amounts of money for much less access, which means that it’s no longer possible for most researchers to do denominator-based work.

Interesting as Reddit and Twitter are, they are much less widely used than YouTube, which is used by virtually all internet users. Pew reports that 93% of teens use YouTube – the closest service in terms of usage is Tiktok with 63% and Snapchat with 60%. While YouTube has a good, well-documented API, there’s no good way to get a random, representative sample of YouTube. Instead, most research on YouTube either studies a collection of videos (all videos on the channels of a selected set of users) or videos discovered via recommendation (start with Never Going to Give You Up, objectively the center of the internet, and collect recommended videos.) You can do excellent research with either method, but you won’t get a sample of all YouTube videos and you won’t be able to calculate the size of YouTube.

I brought this problem to Jason Baumgartner, creator of PushShift, and prince of the dark arts of data collection. One of Jason’s skills is a deep knowledge of undocumented APIs, ways of collecting data outside of official means. Most platforms have one or more undocumented APIs, widely used by programmers for that platform to build internal tools. In the case of YouTube, that API is called “Inner Tube” and its existence is an open secret in programmer communities. Using InnerTube, Jason suggested we do something that’s both really smart and really stupid: guess at random URLs and see if there are videos there.

Here’s how this works: YouTube URLs look like this: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=vXPJVwwEmiM

That bit after “watch?v=” is an 11 digit string. The first ten digits can be a-z,A-Z,0-9 and _-. The last digit is special, and can only be one of 16 values. Turns out there are 2^64 possible YouTube addresses, an enormous number: 18.4 quintillion. There are lots of YouTube videos, but not that many. Let’s guess for a moment that there are 1 billion YouTube videos – if you picked URLs at random, you’d only get a valid address roughly once every 18.4 billion tries.

We refer to this method as “drunk dialing”, as it’s basically as sophisticated as taking swigs from a bottle of bourbon and mashing digits on a telephone, hoping to find a human being to speak to. Jason found a couple of cheats that makes the method roughly 32,000 times as efficient, meaning our “phone call” connects lots more often. Kevin Zheng wrote a whole bunch of scripts to do the dialing, and over the course of several months, we collected more than 10,000 truly random YouTube videos.

There’s lots you can do once you’ve got those videos. Ryan McCarthy is lead author on our paper in the Journal of Quantitative Description, and he led the process of watching a thousand of these videos and hand-coding them, a massive and fascinating task. Kevin wired together his retrieval scripts with a variety of language detection systems, and we now have a defensible – if far from perfect – estimate of what languages are represented on YouTube. We’re starting some experiments to understand how the videos YouTube recommends differ from the “average” YouTube video – YouTube likes recommending videos with at least ten thousand views, while the median YouTube video has 39 views.

I’ll write at some length in the future about what we can learn from a true random sample of YouTube videos. I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about the idea of “the quotidian web”, learning from the bottom half of the long tail of user-generated media so we can understand what most creators are doing with these tools, not just from the most successful influencers. But I’m going to limit myself to the question that started this blog post: how big is YouTube?

[image error]

Consider drunk dialing again. Let’s assume you only dial numbers in the 413 area code: 413-000-0000 through 413-999-9999. That’s 10,000,000 possible numbers. If one in 100 phone calls connect, you can estimate that 100,000 people have numbers in the 413 area code. In our case, our drunk dials tried roughly 32k numbers at the same time, and we got a “hit” every 50,000 times or so. Our current estimate for the size of YouTube is 13.325 billion videos – we are now updating this number every few weeks at tubestats.org.

Once you’re collecting these random videos, other statistics are easy to calculate. We can look at how old our random videos are and calculate how fast YouTube is growing: we estimate that over 4 billion videos were posted to YouTube just in 2023. We can calculate the mean and median views per video, and show just how long the “long tail” is – videos with 10,000 or more videos are roughly 4% of our data set, though they represent the lion’s share of views of the YouTube platform.

Perhaps the most important thing we did with our set of random videos is to demonstrate a vastly better way of studying YouTube than drunk dialing. We know our method is random because it iterates through the entire possible address space. By comparing our results to other ways of generating lists of YouTube videos, we can declare them “plausibly random” if they generate similar results. Fortunately, one method does – it was discovered by Jia Zhou et. al. in 2011, and it’s far more efficient than our naïve method. (You generate a five character string where one character is a dash – YouTube will autocomplete those URLs and spit out a matching video if one exists.) Kevin now polls YouTube using the “dash method” and uses the results to maintain our dashboard at Tubestats.

We have lots more research coming out from this data set, both about what we’re discovering and about some complex ethical questions about how to handle this data. (Most of the videos we’re discovering were only seen by a few dozen people. If we publish those URLs, we run the risk of exposing to public scrutiny videos that are “public” but whose authors could reasonably expect obscurity. Thus our paper does not include the list of videos discovered.) Ryan has a great introduction to main takeaways from our hand-coding. He and I are both working on longer writing about the weird world of random videos – what can we learn from spending time deep in the long tail?

Perhaps most importantly, we plan to maintain Tubestats so long as we can. It’s possible that YouTube will object to the existence of this resource or the methods we used to create it. Counterpoint: I believe that high level data like this should be published regularly for all large user-generated media platforms. These platforms are some of the most important parts of our digital public sphere, and we need far more information about what’s on them, who creates this content and who it reaches.

Many thanks to the Journal for Quantitative Description of publishing such a large and unwieldy paper – it’s 85 pages! Thanks and congratulations to all authors: Ryan McGrady, Kevin Zheng, Rebecca Curran, Jason Baumgartner and myself. And thank you to everyone who’s funded our work: the Knight Foundation has been supporting a wide range of our work on studying extreme speech on social media, and other work in our lab is supported by the Ford Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation.

Finally – I’ve got COVID, so if this post is less coherent than normal, that’s to be expected. Feel free to use the comments to tell me what didn’t make sense and I will try to clear it up when my brain is less foggy.

The post How Big is YouTube? appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

December 2, 2023

Disinfo and Elections in the Global Majority

I’m just back from a very quick trip to Rio de Janiero to take part in a conference put together by dear friend and colleague Jonathan Ong, called Disinformation and Elections in the Global Majority. Hosted at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio (wonderfully enough, shortened to PUC, pronounced “Pookie”) and co-organized by Jonathan and JM Lanuza at UMass Amherst and Marcelo Alvez at PUC, the event began as a conversation between Filipino and Brazilian scholars about the 2022 elections. It expanded to a much broader dialog about what the world could learn from the experiences of democracies in the Global South with disinformation during elections. The gathering brought together activists, journalists and scholars from India, Moldova, South Africa, Indonesia, Myanmar and other countries.

Opening panel for Disinfo and Elections in the Global Majority

At the heart of the gathering is a question: why did the elections in Brazil and the Philippines turn out so differently? Both countries have a long history of colonial domination, independence, and advances and retreats of democracy. In the 21st century, both nations were promising anchors of democracy in their regions, until populist autocrats took power in the late 2010s. The Philippines elected Rodrigo Duterte and Brazil elected Jair Bolsonaro, both authoritarians in the Viktor Orban/Donald Trump model, both using social media to activate supporters and harness divisive cultural issues and fear into popular support.

Both countries held elections in 2022 which served as referenda on authoritarian leadership. In Brazil, Bolsonaro was narrowly defeated by Lula, the former leftist president who came with his own baggage of corruption scandals. My Brazilian friends took pains to explain that Brazil came much closer to a coup than most outside observers understand. Military police blocked buses from bringing voters into polling places known to be Lula strongholds. Motivated by social media and a pro-Bolsonaro radio station, citizens stormed government buildings on January 8, 2023, seeking an overturn of election results. Ultimately, Lula prevailed, winning election by roughly 2 million votes, a slim margin.

The situation in the Philippines was utterly different. Duterte’s chosen successor was Bong Bong Marcos, son of dictator Ferdinand Marcos. His running mate was Duterte’s daughter, making the idea of familiar succession completely clear. Opposition in the Philippines didn’t get behind a single candidate as they did in Brazil, and the leading opposition candidate lost in a landslide to Marcos.

Despite the different outcomes, there were distinct similarities in the elections. In both countries, a narrative emerged – first online, then flowing into mainstream media – that electoral institutions were not to be trusted, that the populist candidates were fighting against the corruption of elites. In Brazil, a narrative emerged around nostalgia for military leadership, just the thing to save the nation from a slide into Communism under Lula. In the Philippines, Marcos managed to rebrand his famously corrupt parents into victims of elite persecution. And in both countries, elections were set up to be distrusted. This position has no downsides for candidates who position themselves as outsiders: if they win, it’s because they overcame the corrupt system, while if they lose, it’s because the election was stolen.

These narratives emerge online, from hired guns and from individual partisans. The language for the narratives online differs between countries. Brazil has firm policies, set by the electoral court, allowing them to order removal of disinformation, and so that’s the term of choice in the Brazilian context. Jonathan and team see the problem as broader than disinformation, including different forms of propaganda, and refer to this online speech as “influence operations”. I like this term, as it includes a particularly tricky type of speech: participatory propaganda, where partisans spread and shape narratives on their own, not necessarily because they are receiving commands as part of a “cyber army”.

The Brazilians are rightly proud of having defended their democracy, and point to the judiciary as the key institution. The electoral court made rulings on disinformation and ordered platforms to take down content… and they did. In the Philippines, civil society organizations pressured platforms behind the scenes to control these influence operations, and got fewer results. So one hypothesis is that controlling platform behavior is a key step in defending free elections.

This feels a bit strange as an American, as we tend to be pretty sensitive to any restrictions on political speech – I asked variants of the same question to several Brazilian friends: Is it okay to restrict online speech if you’re not restricting the press? The answers surprised me: we should be restricting the press. Certain restrictions on media are necessary to ensure that you can have an environment conducive to holding fair elections.

It’s understandable that people around the world – particularly in the Global South – would want to see more control over the large online platforms. These companies make money in countries like Brazil and the Philippines, but have – at best – a limited knowledge of politics and culture on the ground, and apparently limited interest in complying with local laws. But there’s a problem with pushing for strong local government regulation of the internet: India. The Modi administration has aggressively controlling online speech environments, flooding platforms with demands to take down content the government finds offensive. The justification for these takedowns? THe information they challenge is “disinformation”, banned under local laws. India is a massive market and particularly spineless “free speech” advocates – i.e., Elon Musk – have been extremely receptive to demands from the government of a country that is a massive market for Twitter and his other companies.

At the same time that the Modi government is silencing critical speech, India has developed profound disinformation problems, in support of government narratives. A set of Indian activists, journalists and scholars (who’ve asked for remarks to be Chatham House to protect themselves and their families) presented research on the phenomenon of the “vox pop”, viral videos in which “ordinary Indians” share points of view consonant with government narratives. Vox pops allow the BJP to promote divisive and false narratives like “love jihad”, the idea that Indian Muslims are seeking to trap Hindu women in marriage to turn the nation into an Islamic state: one speaker describes this as the “Indian Great Replacement Theory”. The same actors appear again and again in these videos, but that’s a hard pattern to see unless you’re collecting hundreds of these. For many Indians, they encounter these influence campaigns through WhatsApp groups – a family member will post a video as a daily status update and encourage others to share it as well.

Even if platforms were inclined to combat this sort of viral disinformation, the researchers argue that they might not be able to do so because of the challenge of cultural context. One researcher shows a popular Hindutva meme: people changing their job status to “cauliflower farmer”. This is a reference to the Logain Massacre in Bihar, India 1989, where 119 Muslims were killed and buried, and their corpses hidden by planting cauliflower over their graves, disguising the mass grave. To recognize this change in job status as a form of hate speech and celebration of mass murder, a content moderator would need to understand Indian history quite well. Needless to say, the cauliflower farmer posts aren’t being identified and sent to platforms by the Modi government, while many innocuous posts supporting Kashmiri or Sikh rights are.

The India situation – a powerful government whose institutions are being used to silence online speech, rather than combatting all hateful influence operations – is one that should serve as a caution to anyone who sees regulating social media platforms as a silver bullet for mis/disinformation. India is one of the world’s leaders in requesting takedowns of content, and many of these takedowns are weaponized against political or social opposition. But that’s not the only situation in which government regulation of US-based social media is an unrealistic approach to a complex problem.

A speaker representing a fact checking organization from Moldova presented the audience with a ferocious problem. Moldova was part of the former Soviet Union, and its breakaway eastern region of Transnistria includes Russian-speaking citizens who want closer ties with Russia. Most Moldovans speak Romanian and the nation is split politically between those who seek a future in the European Union and those who look to Russia. But it’s not a level playing field for a debate between the EU and Russia: according to our speaker, Russia invests 0.5% of Moldova’s GDP annually in advertising and disinformation campaigns in Moldova.

Additionally, if you’re a Russian speaker in Moldova, you almost certainly use Russian-hosted platforms like VK as major sources of information – controlling the spread of influence operations on Facebook is less important than on platforms like Telegram, where Russia may have a significant influence on platform operations. This problem is even more profound in a country like Taiwan, which is both a target for influence operations from China and where language consonance means virtually everyone uses tools like Weibo. Taiwan is extremely unlikely to have success getting government-influenced platforms to take down disinformation.

Our Moldovan friend has some good news: pre-bunking appears to work. This is the practice of explaining the narratives an attacker is likely to use before those narratives emerge. For instance, if the Biden administration has any hope of preventing a repeat of January 6, 2021, it will be by explaining loudly that Trump and allies are falsely claiming election interference because they can’t win a free and fair election. Successful prebunking in Moldova – as seen by the pro-West party winning a large share of 2023 local elections despite massive election spending from Russia – required making electoral information funny and viral. Unfortunately there’s no easy formula to guarantee that civic information can be funny and viral, and also no guarantee that pro-West forces will remain allies of pro-democracy movements once they’ve secured power.

I felt most hopeful after a presentation by Tai Nalon of Aos Fatos, who has steered her fact checking organization into a major producer of innovative disinfo fighting tools. Disinfo in Brazil often spreads via WhatsApp, which is an especially challenging platform on which to combat influence operations – WhatsApp groups are private, which makes studying them an ethical challenge (you can ask to subscribe to a group, but you are likely to be turned down, or you can try to join under false premises, which many IRBs will forbid) as well as a technical one (WhatsApp is encrypted by default, meaning you can’t monitor conversations as a researcher without being invited to take part).

Aos Fatos has deployed various fact-checking robots in WhatsApp and Telegram channels. Their most recent version, called Fatima, uses GPT-4 to parse requests for information, which are matched against Aos Fatos’s database of claims and debunking information. After retrieving human-vetted and constructed information, Fatima uses GPT-4 to provide a conversational response to the user. Because Fatima is essentially a search engine of Aos Fatos’s carefully produced debunking material, it should be much more resistant to hallucination than simply unleashing ChatGPT on a Telegram channel to perform debunks.

Fatima is one of several impressive tools Aos Fatos has produced – they have a lovely “disinfo tracker” called Radar that runs a list of nationalist and extremist keywords against various social media APIs to track how influence narratives are trending over time. (Unfortunately, like everyone else, they are suffering from the closure of social media APIs necessary to do this work.) And Golpeflix collects video and images of the attempted coup in January 2023. Even for folks like me who firmly believe that tools alone won’t conquer well-financed disinfo campaigns, the capabilities and appearance of Aos Fatos’s tools set a very high bar for what’s possible.

I am, as a rule, somewhat skeptical that mis/disinfo is a central problem for the defense of democracy in a digital world. I think Jonathan Ong’s “influence operations” formulation is much stronger, as it includes a recognition that propaganda, rather than disinfo per se is the key problem. But even broader is the problem of conflicting, irreconcilable narratives – the danger in the US is that Trump and Biden supporters are so separated in their understanding of the world that there’s no longer a set of common facts they can agree on. The tactic of splitting reality into two or more pieces – which several speakers linked to Steve Bannon, but which likely has roots in Putin’s Russia – is becoming pervasive around the world. Finding ways to fight for an understandable reality and way people around the world can engage in democratic decisionmaking is a worthy cause and good reason to get on an airplane, if even for a very brief visit.

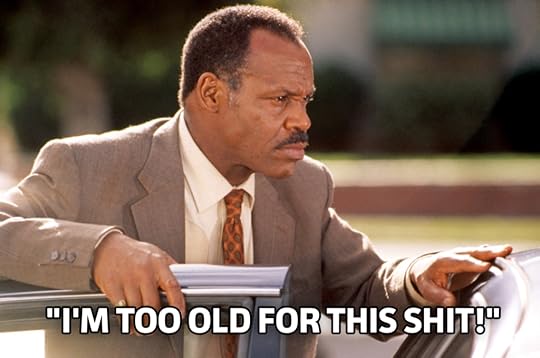

Needless to say, I am beyond glad that I participated in the conference. At the same time, I increasingly relate to Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon – I am getting too old for this shit, specifically the “three days on another continent” travel that teaching requires. Glover was 41 when that film was made, playing 50. I sometimes feel like I am 50, playing 30. At the same time, I hope I never get too old for this shit – it’s wonderful to put everything aside for a few days and learn something new from people I otherwise would be unlikely to meet. Thank god I’m not too old for this shit.

The post Disinfo and Elections in the Global Majority appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

November 8, 2023

Kai-Cheng Yang: The Social Bots are Coming…

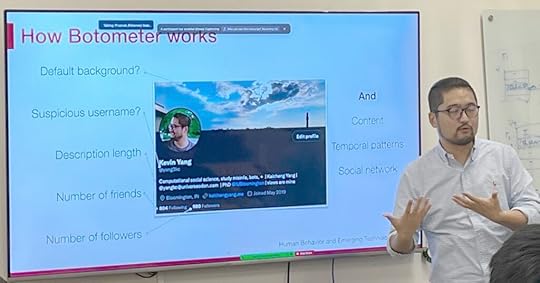

Kai-Cheng Yang is the creator of Botometer, which was – until 2023 – the state of the art for bot detection on Twitter. He’s a recent graduate of Indiana University where he worked with Fil Menczer and is now a postdoc with David Lazer at Northeastern University. His talk at UMass’s EQUATE series today focuses on bot detection – the talk is titled “Fantastic Bots and How to Find Them”.

The world of bot detection is changing rapidly: Yang suggests we think of bot detection as having three phases: pre-2023, 2023 and the forthcoming world of AI-driven social bots. In other words, bot detection is likely to get lots, lots harder in the very near future.

Kai-Cheng Yang speaking at UMass Amherst

What’s a bot? Yang’s definition is simple: it’s a social media account controlled, at least in part, by software. In early days, this might be a Python script that generated content and posted on social media via the Twitter API. These days, bad actors might run a botnet controlling hundreds of cellphones, logged into a single computer, posting disinfo in a way that’s very difficult for platforms to detect. The newest botnets operate using virtual cellphones hosted in the cloud. Yang invites us to imagine these hard-to-detect botnets powered by large language models, to make detection via content extremely difficult.

Yang is (rightly) celebrated for his work on Botometer, which was – until recent changes to the Twitter/X API – freely available for researchers to use. Detecting bots is a socially important function – they are often used to manipulate online discussion. Using his own tools, Yang discovered botnets promoting antivax information during COVID lockdowns – he found very few bots trying to share credible information from sites like CDC.gov. One signature of these bots – they kick in and amplify COVID misinfo within a minute of initial posting.

At its heart, Botometer is a supervised machine learning model. It looks at a set of signals –

accounts with default backgrounds, suspicious username, brief description length, a small number of friends or followers – to identify likely bots. Other factors are important as well – Botometer looks at the content shared, the temporal patterns of posting and the social graph of the bot accounts. The project was started in Menczer’s lab in 2014 – Yang took the project over in 2017 and oversaw changes to the model to react to changes in human and bot behavior, as well as a user-friendly interface.

One big fan of Botometer, at least initially? Elon Musk. He tried to make a case, using Botometer, that Twitter had inflated its user numbers with bots and therefore he should be able to back out of his acquisition of the platform. Yang ended up testifying in the Twitter/Musk case and argued that Musk was misinterpreting the tool results.

In 2023, Twitter changed the pricing structure for its APIs, making it extremely expensive for academic users to build tools like Botometer. Botometer no longer works, and Yang warns that future versions will need to be much less powerful. There are some legitimate reasons why Musk and other CEOs want to restrict API access: social media data is powerful training material for large language models. But the loss of tools like Botometer mean that we’re facing an even more challenging information environment during the 2024 elections.

Yang introduces us to a new generation of AI-powered social bots. He’s found them through a very simple method: he searches for the phrase “I’m sorry – as a large language model, I’m not allowed to…”, a phrase that ChatGPT uses to signal when you’ve hit one of its “guardrails”, a behavior it is not allowed to engage in so as to maintain “alignment” with the goals of the system. Seeing this phrase is a clear sign that these accounts are powered by a large language model.

And that’s a good thing, because otherwise, these accounts are very hard to spot. They are well-developed accounts with human names, background images, descriptions, friends and followers. They post things, interact with each other and post pictures. Once you know where they are, it’s possible to find some meaningful signals from analyzing their social graph. These bots are tightly linked to each other in networks where everyone follows one another. That’s not how people connect with one another in reality. Usually some people become “stars” or “influencers” and are followed by many people, while the rest of us fall into the long tail. We can tell this distribution is artificially generated because there is no long tail.

Additionally, these bots are a little too good. On Twitter, you can post original content, reply to someone else’s content, or retweet other content. The AI bots are very well balanced – they engage in each behavior roughly 1/3rd of the time. Real humans are all over the map – some people just retweet, some just post. The sheer regularity of the behavior reveals likely bot behavior.

Why did someone spin up this network? Probably to manipulate cryptocurrency markets – they largely promoted a set of crypto news sites. Is there a better way to find these things than “self-revealing tweets”, essentially, error messages. Yang tried running the content of these posts through an OpenAI tool designed to detect AI-generated text. Unfortunately, the OpenAI tool doesn’t work especially well – and OpenAI has taken the tool down. Yang saw high error rates and found people whose writing registered more bot-like than texts actually written by known bots.

The future of bot detection comes from “clear defects” and “inconsistencies”. Generative Adversarial Networks can create convincing-looking faces, but some will have serious errors, and humans can see these obvious problems. Sometimes the signals are inconsistencies – a female face with a stereotypically male name. Like the “self-revealing tweets”, these are signals that we can use to detect AI accounts.

Using signals like this, we can see where AI bots are going in the future. Yang sees evidence of reviews on Amazon, Yelp and other platforms that are using GPT to generate text and GANs to create faces. We might imagine that platforms would be working to block these manipulative behaviors and while they are, they’re also trying to embrace generative AI as a way to revive their communities. Meta is trying to create AI-powered chatbots to keep people engaged with Instagram and Messenger. And someone clever has introduced a social network entirely for AIs, no humans allowed.

The future of the AI industry, Yang tells us, is generative agents. These are systems that can receive and comprehend info, reason and make decisions and act and use tools. As these tools get more powerful, we must be conscious of the fact that not all these agents will be used for good. Identifying these rogue agents and their goals is something we will need to keep getting better at as we go forward… and right now, the bot builders are in the lead.

The post Kai-Cheng Yang: The Social Bots are Coming… appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 10, 2023

Heather Ford: Is the Web Eating Itself? LLMs versus verifiability

One of my favorite things in academia is that you can go a decade without seeing a friend and remain at least somewhat in touch with what they’re doing and thinking by reading their work. Dr. Heather Ford, Associate Professor of Communication at the University of Technology Sydney, where she leads the cluster on Data and AI Ethics, is in the US for two weeks, and we were lucky enough to bring her to UMass Amherst for a talk today. I haven’t seen Heather in person for over a decade, but I’ve had the chance to follow her writing, particularly her new book, Writing the Revolution: Wikipedia and the Survival of Facts in a Digital Age.

I knew Heather as one of the leading lights of the open knowledge world, co-founder of Creative Commons South Africa, leader of iCommons (which worked to create open educational resources from the Global South), scholar and critic of Wikimedia. In the last decade, she’s also become one of the most interesting and provocative thinkers about how knowledge gets created and disseminated in a digital age.

Heather Ford speaking at UMass Amherst

Her talk at UMass today, “Is the Web Eating Itself?” asks whether Wikimedia other projects can survive the rise of generative AI. Heather characterizes our current moment as occurring after the “rise of extractivism”, a moment where technology companies have tried to extract and synthesize almost the entire Web as a proxy for all human knowledge. These systems, exemplified by Chat GPT, suggest a very different way in which we will search for knowledge, using virtual assistants, chatbots and smart speakers as intermediaries. While there’s some good writing about the security and privacy implications of smart speakers, what does the experience of asking a confident, knowledgeable “oracle” and receiving an unambiguous answer do to our understanding of the Web? What happens when we shift from a set of webpages likely to answer our question to this singular answer?

This shift began, Heather argues, with synthesis technologies like the Google Knowledge graph. The Knowledge graph aggregates data about entities – people, places and things – from “reliable” sources like Wikipedia, the CIA World Factbook and Google products like Books and Maps. The knowledge graph allowed Google to try and understand the context of a search, but it also allowed it to direct users towards a singular answer, presented in Google’s “voice” rather than presenting a list of possible sources. For Heather, this was a critical moment when both Google and our relationship to it changed.

The rise of ChatGPT, embodied in Bing chat and many AI text generators, is another profound shift. These technologies, at root, have been “fed almost the entire internet to predict the next chunk of text – the game is to finish your sentence.” She quotes Harry Guiness as explaining that Chat GPT is extremely different from knowledge graphs: “It doesn’t actually know anyting about it. It’s not even copy/pasting from the internet and trusting the source of information. Instead, it’s simply predicting a string of words that will come next based on the billions of data points it has…”

AI tools require “datafied facts”, text from Quora, Reddit, Stack Exchange and Wikipedia – sites where people answer questions, like Quora and Stack Exchange, are especially helpful. AI systems remove the particularities of these sources, eliminating local nuance and context, in ways which can be very dangerous. Brian Hood, mayor of a small city near Melbourne, is exploring suing OpenAI for defamation, because it routinely produces texts identifying him as committing financial fraud. Actually, Hood was the whistleblower who revealed financial fraud, but that pertinent detail is not one ChatGPT has grasped onto. If Hood sues, the question of how the algorithm comes up with these false answers will be one litigated either in US or Australian court.

Heather explains that the “authoritative synthesis that comes from ChatGPT coincides with a moment of increasing distrust in institutions – and a rise of trust in automated processes that seem not to participate in truth battles because they are seemingly unpolitical.” (Indeed, readers of her most recent book understand that there’s little more political than the processes through which events in the world find their way into Wikipedia, Wikidata and from there into the Google Knowledge Graph. These politics don’t map neatly onto our understandings of liberal/conservative, but merit study and critique on their own merits.)

What happens if Wikipedia starts ingesting itself through generative AI? Wikipedia is one of the most important sources for training generative AIs. Will we experience model collapse, where models trained on their own data degrade in performance? Will projects like Wikipedia collapse under the weight of unverifiable information?

These concerns lead to real questions: should Wikimedia ban or embrace generative AI tools. Stack Exchange has banned ChatGPT for answers due to a tendency to create convincing, hard to debug, wrong answers. Should Wikimedia sue new intermediaries like OpenAI? Or merge with them? Call for regulation or reforms?

Core to the Wikipedia project is verifiability, an idea that Heather extends far beyond the idea of authorship and copyright. Across the Wikimedia universe, a “nation of states” that Heather reminds us includes everything from Wikimedia Commons, Wikidata and Wikipedia to Wikifunctions (an open library of computer code), verifiability is a central principle:

“(WP:VER) Readers must be able to check that any of the information within Wikipedia articles is not just made up. This means all material must be attributable to reliable, published sources.”

Verifiability, Heather explains, isn’t just an attribute of the content – it contains the idea of provenance, the notion that an piece of information can be traced back to its source. Heather suggests we think of verifiability as a set of rights and responsibilities – a right for users to have information that is meaningfully sourced and the responsibility for editors to attribute their sources. These rights enable important practices: accountability, accuracy, critical digital literacy and most important, agency. If you don’t know where a piece of information came from, you cannot challenge or change it. Verifiability enables ordinary users to change and correct inaccurate information.

(I’ve been thinking about this all day, because it’s such an important point. In an academic setting, citation is about provenance – it’s about demonstrating that you’re acknowledging the contribution of other thinkers and claiming only your contributions. But this is a version of citation and provenance that is linked to challenging inaccuracy and rewriting what came before, if necessary. It lets go of the academic default that everything that came before is true, and sees the verifiability of facts as a source of power. It’s a very cool and powerful idea.)

So what happens to Wikipedia in an age of large language models, which threaten both the sustainability of peer knowledge projects and their verifiability? Heather sees several disaster scenarios we need to consider.

– Editors might poison the well, filling Wikipedia with inaccurate articles, leading to higher maintenance costs and lower reliability

– Users may turn away from Wikipedia and to new interfaces like ChatGPT. A problem that began with the Google Knowledge Graph – where people attributed facts to Google, not Wikipedia, may erode Wikipedia’s brand and participation further

– LLMs may improve Wikipedia in English, but are less likely to help it improve in smaller languages. That, in turn, may make large languages like English even more central and increase problems of information inequality.

– Improved translations – one of the places AI has developed the most quickly, may be a force for cultural imperialism. Heather remembers Jimmy Wales visiting South Africa and asking South Africans to write Wikipedia articles in the 11 official languages of the nation. But automatic translation has meant that some small language Wikipedias are essentially machine translations of the English language Wikipedia – the Cebuano Wikipedia is the second-largest Wikipedia in terms of articles, but is almost entirely produced by automated scripts. As a result, it reflects the priorities of the English-language authors who wrote the English wikipedia, not the priorities of Cebuano speakers.

Despite these concerns, Heather reports from the most recent Wikimania conference that Wikimedians are generally optimistic. To the extent that Wikipedia is a project that seeks a compilation of all human knowledge, perhaps the more knowledge the better! And the ability to create coherent English may be very useful for non-native English speakers. There’s also the thought that perhaps Wikipedia can create a better LLM, one with verifiable information. And Heather reports that the Wikimedia foundation tends to feel that they’ve been using machine learning since 2017 – perhaps LLMs aren’t that threatening? And since Google paid Wikimedia a license fee for Wikidata, perhaps OpenAI and others are customers for Wikipedia – why sue your potential customers?

On the other side of the fence are those who worry that Wikipedia labor will become “mere fodder” to feed AI systems, invisible and unappreciated. Wikipedia, they fear, will never win the interface war – as an open source project, it will always be uglier and rawer than the slick interfaces developed by Silicon Valley. (And, some grumble, perhaps Wikimedia Foundation is too close to Silicon Valley ideology and capital to see the possible harms.)

Heather tells us that she sees two concerns as overriding:

– LLMs aren’t like grammar checks or other systems that have been used to improve human writing. Instead, they represent knowledge in an entirely different way than the knowledge graph.

– The trajectory of LLMs threatens verifiability in a way that threatens projects that depend on verifiability – accountability, accuracy and critical digital literacy.

The answer, Heather believes, is a campaign for verifiability. This means we need new methods for meaningful attribution in ways that fulfill the rights and obligations of factual data. These methods need to make sense on new interfaces – we need to understand how an oracular voice like ChatGPT “knows” what it knows and how we could trace that information back to challengable sources. And we need in-depth research on how verifiability relates to sustainability of projects like Wikipedia.

But verifiability is in decay, even in Wikimedia, she warns. Much of the data in Wikidata lacks meaningful citation. And because Wikidata is licensed under CC0, a very permissive license that puts the work in the public domain, there’s no obligation for those who use it to trace provenance back to Wikidata.

Wikipedia’s OpeAI plugin does not provide citations, and Wikimedia enterprise – the tool through which Wikidata is licensed to the Google Knowledge Graph and others, has a lack of citation guidance. Beyond citing Wikimedia on Google’s knowlege panels, most virtual assistants have little or no attribution.

Open licenses like Creative Commons don’t currently signal anything to extractive AI companies. They should – they should signal that the information in question is public knowledge and that it should have certain patterns of verifiability associated with it. Right now, Wikipedia is simply another pile of fodder for openAI – according to the Washington Post, it’s the #2 source of training data for many large LLMs (Google’s Patent DB is #1) and the number #3 source is Scribd, a large pile of copyrighted materials being used in (likely) violation of copyright. b-ok.org, a legendary book pirating site, is #190 on the WaPo list – ChatGPT and other LLMs are a complex pile of open knowledge and various forms of copyright violation.

We need a new definition and new terms for openness in the age of AI. Right now, the focus is on developers rather than content producers, on data for computers rather than for people. Data producers like Wikipedians need to be at the center of this debate. Unverifiable information should be flagged and steered away from rather than being the default for these new systems. What’s at stake is not just attribution, payment and copyright: it’s reclaiming agency in the face of AI through maintaining the production of verifiable information.

Heather is continuing to work through these ideas – I predict lots more in this direction, and look forward to seeing how she and others develop this key idea of verifiability as a response to the rise of the LLM. It was such a pleasure to have her at UMass.

The post Heather Ford: Is the Web Eating Itself? LLMs versus verifiability appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

September 21, 2023

What I Did On My Summer Vacation: 2023

It’s chilly here in western MA and there’s a hint of red starting to show in the leaves. This was the second full week of classes and I’m remembering the joy of teaching at UMass, a place where our classes bring together a remarkable cross-section of smart people from across our state and the world. Summer is well and truly over, even though there are likely at least a few hot days still to come.

I had an odd summer. I often work on a new course, a book or another major project in those months “off”. (Because I run a research lab, there is no “off” – our work continues through the summer, but the rhythms are different.) Instead, I did a great deal of reading (often listening, as I walked or slowly jogged in a feeble attempt to get my 50 year old body into better shape) about climate change, urban resiliency and migration patterns in the US and across international borders. (I wrote briefly about what I learned here, and hope to be writing more about cities, migration and climate soon.)

But, it turns out, I made some stuff too.

With Mike Sugarman at the helm, Reimagining the Internet, our biweekly podcast, has become one of my favorite things we produce at Initiative for Digital Public Infrastructure. We released some amazing episodes this summer. My interview with Timnit Gebru, founder of DAIR and co-founder of Black in AI, has been our most dowloaded ever. Timnit, who’s been doing original research in AI for many years, is skeptical of many of the claims made by large AI vendors and offers explanations that will help you become a more critical consumer of claims made about these systems. My dear friend danah boyd joined the show for the following episode and helps us understand the wave of legislation that tries to “protect” children from internet harms, real and imagined, and ends up harming queer youth.

As the summer came to an end, Mike and I started talking with scholars who’ve been researching social media’s effect on democracy, including scholars who worked with Meta on a series of experiments around the 2020 US presidential election. Laura Edelson, a brilliant computer science researcher whose work studying ads on Facebook was blocked by the platform, talks about the challenges of researching what’s really happening on major social media platforms, which is difficult even when you’re representing the US government. We just released an episode with Talia Stroud, one of the leaders of the collaboration between academics and Meta to study the US elections, and in a forthcoming episode, I talk with Brendan Nyhan, lead author on one of the papers. You can think of this package of episodes as an asynchronous debate about the values of “permissionless” and “permissioned” research.

I write a monthly column for Prospect, a terrific British magazine edited by Alan Rusbridger, who helped lead the transformation of The Guardian into a digital powerhouse. My first column of the summer was poorly timed – it was a celebration of the wonderful weirdness one can find on Reddit, introducing the redditmap.social tool we developed in my lab, but after it was submitted, Reddit severely limited access to its API, harming its community leaders and crippling the tool we’d built. I still love Reddit, even if I don’t love these changes it has been making.

My most recent column for Prospect is one of my favorites. It was inspired by a trip I took early in the summer to Lowell, MA, to visit Lowell National Historic Park, a museum about the rise and fall of the textile industry in a small city north of Boston. It took armies of poorly paid people to keep those massive textile looms running, even though the awesome and powerful looms captured the public imagination. My most recent column draws an analogy to generative AI which, though awesome and powerful, relies ultimately on generations of humans generating text and images and on armies of humans annotating those pictures and text. Please give it a read – I think it’s a helpful perspective on how generative AI really works and what its limits are.

My team and I worked on several academic papers which may come out in the next year, focusing on our Reddit and YouTube research. There’s two recent academic publications that I’m excited about. One was inspired by a talk I gave to Stanford’s Trust and Safety Research Conference, a personal talk about my early history with content moderation on user-generated content platforms. Chand Rajendra-Nicolucci, my indispensable writing partner, pulls us back from nostalgia and into recommendations for how we might learn from earlier models of community management that resembled governance more than customer service. From Community Governance to Customer Service and Back Again: Re-Examining Pre-Web Models of Online Governance to Address Platforms’ Crisis of Legitimacy” in Social Media and Society.

(Some of the reading I did in late Spring/early Summer is of marvelous work by Nathan Schneider at CU Boulder, who’s done great work on some similar topics – we wrote the paper before I had the chance to dig into his writing, but I’m highlighting it here for those excited about these topics. )

Chand was lead author on the second piece we released this summer, an essay about third party tools you can use to manage social media better. We are big supporters of tools like Tracy Chou’s Block Party, but wanted to address some very smart concerns raised by Daphne Keller about privacy implications of this type of software. Chand (with a modest assist from me) suggests considering these tools through the framework of contextual privacy and offers a way to think of handing off your email or social media to be scanned by a third party as within the bounds of how we expect to be treated within a social media interaction. You can see the piece here: “A Better Approach to Privacy for Third-Party Social Media Tools” in Tech Policy Press.

I’m posting this all here for at least three reasons. One, I’m proud of this work and want to make sure people see it, hear it and read it. Two, I’m finding that I’m using less social media – Twitter makes me sad these days, and I haven’t found the momentum I’ve wanted on any of the alternative social platforms. I am no longer sure how people are finding my work, and I want to spend more time on this blog, as it’s a space I own and control, as opposed to a “public” space controlled by a capricious billionaire. And finally, like everyone else, I have terrible imposter’s syndrome and need to remind myself that I really do make things that I like… :-)

The post What I Did On My Summer Vacation: 2023 appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

August 8, 2023

Lightning Talks at CU Boulder Local Tech Economies

Much of the Local Tech Ecology conference is a series of lightning talks at the Local Tech Ecologies conference at CU Boulder. Some short notes on each talk:

Josh Ritzer from Nigh: “Talking about local is one of the most important things we’re not doing in society.” Josh grew up in Minnesota in a small town, and remembers watching big box stores displacing local businesses. He notes that rising inequality is destroying America’s middle class. We need to transform local commerce, building systems that pushes economic value to the local level.

Coupons and “deals” are signs of an inefficient market, he argues. We need businesses to be able to adjust prices in real time to help local businesses be more profitable. 70% of consumer spending is still local, which means transforming local could be a massive transformation.

Nigh is a small, Boulder-based tech company. It’s local TikTok, with videos from local businesses. A Boulder pilot has brought dozens of customers to local businesses, sometimes in less than an hour, often during some of their shortest times. These drops (short videos) work, but aren’t scaleable – they’re now pivoting to daily local broadcasts. These are short videos and include local news organizations as well as messages from local businesses.

Caroline Savery from Bloom Network: “Bloom’s mission is a billion acts of regeneration.” The goal is people taking action at local scales. She points out that 2/3rds of people agree we’re in a climate crisis, but cannot find local ways to participate. She describes Bloom as a “cyber-physical” social network, which allows you to give money, time or energy to local initiatives. It’s structured as a global DAO, capable of distributing resources to local projects.

The project has started 700 farms and gardens, based around 32 hubs and 30,000 real life participants. The structure allows solutions to be locally developed, which is necessary for sustainability and appropriateness to local situations. Savery is involved specifically with the Denver Bloom, hosted at a “cooperative congregation” called Shared Ground. It’s an effort for both local communities and climate responses – bringing people together to cultivate local solutions is the mission of the “church”.

Nikhil Mankekar is the vice chair of the Colorado Venture Capital Authority, a project of the State of Colorado to invest in businesses within the state. The organization provides seed stage capital ($500k-$1m), and runs funds of funds, with a focus on diversity and supporting underrepresented startup founders.

There are massive inequities in who receives startup funding in the state. But CVCA believes they are uniquely positioned to solve these disparities, by virtue of being local and capable of directly centering multiple diversities. He notes that “friends and family” rounds, like Jeff Bezos used to initially finance Amazon, is a gap that needs to be bridged to bring underrepresented founders into the mix.

Becks Boone presents Rootable, a volunteer logistics software package that’s incorporating as a cooperative software company. The work comes out of Boulder Food Rescue, a non-profit moving produce from grocery stores to local communities. One of the founders created open source software to manage these logistics and has been maintaining it for a decade. This software is likely helpful for 32 other food rescue organizations that are members of the Food Rescue Alliance, but these organizations don’t have lots of time to build their own logistics software.

Becks invited participation from these 32 organizations and built an MVP (minimum viable product) based on this input and feedback. The work began with the six Colorado rescue organizations – it was very hard to align input from all 32 organizations. Jamie Anderson leads Denver Food Rescue, a project that’s not yet on the platform. Denver Food Rescue manages 45 vendors and 120 volunteers, 363 days a year. She feels strongly that apps are not the solution – it’s the community working on food justice that’s the solution.

Not only does a logistics platform need to support all the moving pieces, it needs to track donations so that food donors can get the tax writeoffs they deserve. There are major barriers to tech adoption – older volunteers, volunteers who don’t speak much English. There’s also a tremendous need for flexibility: what happens when a recipient’s warehouse is flooded? (Super exciting project in a space that needs all the help it can get.)

Pat Kelly of Colorado ReWild is the sponsor for our conference as a whole. He’s the founder of Routinify, tech for aging adults to help people age in place.

Colorado ReWild seeks open social networks for networking local nonprofits. The goal is to embed the tech into local organization’s websites, rather than pushing users to Mastodon or something else.

ReWild is based on ActivityPub, and uses Mastodon and PeerTube under the hood, but the goal is to keep people embedded within the websites they’re already using. He’s aware that there’s a strong need to stoke the conversation. The goal is to use lots of CU Boulder interns to create content, helping people understand the values behind volunteerism. Structurally, the goal is for people using the software to be owners of the relationships and content.

Kelly shares thoughts on why it’s critical to keep users on your site: stay connected, don’t lose these users to Twitter, Facebook or somewhere else. You’ll own the content and eventually own the conversation. He’s trying to lower risk to nonprofit participants by offering five years for free and ensuring content can be cloned between YouTube and Instagram to reduce replication of effort.

Libi Striegl is managing director of the Media Archeology Lab at CU Boulder, one of the largest collections of functional archaic technology in the world. The center was founded by Dr. Lori Emerson in 2009, and gives students hands on interactions with obsolete technologies that still have artistic and historical value.

The Media Archeology Lab seems like a museum, but is not one – it’s more interested in experiential and hands-on learning. With that in mind, Striegl has brought several OLPC devices, which they were gifted in 2017. The machines had been in use in Ethiopia, but there’s a real gap between what these machines were promised to be, and what they actually were useful for. They ended up being an object lesson in the importance of educators and the difficulty of building technology that can be used without oversight or supervision.

The OLPC machines are here today, using their mesh networking to create a local network which can be used for chat, without using hashtags on Xitter or other global networks – what can we do with the detritus of failed tech experiments and repurpose for new purposes.

LeeLee James, “the twirling tech goddess” presents Slay the Runway as a platform for empowering queer youth through fashion. LeeLee is a YouTuber who focuses on accessibility for people historically underrepresented in STEM through fashion and wearable tech. She was a drag queen and a figure skater with Disney on Ice, and is now a student at CU Boulder majoring in Computer Science, and a mother to queer “gabies and babies”.

Slay the Runway is a two week long camp where young queer and trans youth from Boulder and Longmont come to maker spaces and teach people how to sew. It ends with a runway show, displaying the work created by young queer creators. LeeLee explains how mentors have empowered her with skills in the past, including sewing and ice skating, and how this motivates her work.

Erika Lanco and Trish Uvenferth of the Rocky Mountain Employee Ownership Center present The Drivers Cooperative-CO, a brand new ride share cooperative in Colorado. Uvenferth introduces herself as a former computer programmer who had some life changes, and explored a variety of gig work. Lyft and Uber worked well for her at first, but the fares started decreasing, and the customers started complaining about prices. She felt like something could be done to challenge the platform duopoly.

She connected with the Rocky Mountain Employee Ownership Center, which was building a new platform owned by workers. Could a new platform address issues like discrimination against drivers due to ethnicity, language or race? Could these systems be fairer fiscally to drivers without overpaid CEOs? Drivers for Uber and Lyft get about 30-40% of fares, which doesn’t seem fair. The goal is to give drivers 80% of the fare using a local app, giving only 20% to the cooperative.

Lanco is a researcher at RMEOC, which incubates new worker-owned projects and helps convert existing businesses to worker ownership. She cites the Drivers Cooperative in New York, which began in 2019 and was able to make $5 million by 2022. There’s now a federation of Driver’s coops in Colorado, NY, SF and LA. There are now 200 drivers signed up to work on this in Colorado. The goal isn’t just better fares, but driver control and ownership.

Mike Perhats of Nosh presents on Open Commerce Networks. Nosh is a food delivery cooperative in Fort Collins, Colorado. He cites a history of GrubHub “gobbling up” local food delivery companies, which had good relationships with local restaurants, raising prices and decreasing quality. Nosh is a restaurant-owned alternative to Doordash and others, saving restaurants an average of $4.90 an order by challenging monopoly ownership. Nosh now has 50% penetration in Ft. Collins.

Nosh is now working with a lab at Princeton to build Open Commerce Networks, helping disintermediate these powerful middlemen from local economies. He describes most Silicon Valley companies as one of two things: aggregators and arms-dealers. Aggregators hide data from their suppliers and control the relationships; arms dealers empower companies, but sacrifice network effects. Could there be an alternative to these two paradigms?

When platforms achieve power via network effects, they can effectively raise prices to whatever level they want. Drivers and riders on Lyft don’t communicate – the platform becomes indispensible. But restaurants are different – the relationship is between the specific restaurant and consumer. Is there a way to use open standards and systems to enable less captured ecommerce relationships?

The post Lightning Talks at CU Boulder Local Tech Economies appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Local Tech Ecologies: Fernanda Rosa on decolonizing technology

I’m at UC Boulder this morning at a conference organized by friend and colleague Nathan Schneider. He’s a professor of media studies who has done tremendous work thinking about communities and the systems that support them. Today’s conversation is focused on local tech ecologies, specific to Boulder, CO and more broadly. Nathan’s inspiration for the conference is, at least in part, disaster response. The Marshall Fire of December 2021 destroyed more than a thousand homes and left Boulder residents turning to social media to protect themselves and understand what was happening.

The platforms Boulder citizens turned to weren’t ones they owned, and they didn’t always work the way they should. Nathan notes that this is a theme we’re finding as communities react to disaster. During the pandemic, many of us became dependent on delivery services, which again were not designed with local needs in mind, and which often served local businesses very poorly. Thinking about how we build and maintain tech infrastructures is one of the main rationales for the conference.

Our opening keynote is from Fernanda Rosa, a Brazilian science and technology studies scholar who teaches at Virginia Tech. Rosa’s interests are in the intersections between tech structures with a global reach (the routing systems of the internet, powerful internet platforms) and local communities.