Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 6

July 7, 2023

Competition for Twitter is good. Threads, thus far, is not.

On July 6th, Facebook (note 1) launched Threads, their new messaging microblogging system built on top of Instagram… in other words, their Twitter killer. Within 24 hours, more than 70 million people – myself included – had signed up for the service, making it the fastest growing social network in history.

But let’s be clear: Facebook had a serious head start. More than 3 billion users around the globe use one of Facebook’s core products – Facebook, Instagram, or WhatsApp – and the company can advertise the new service to any of those users. If you had an Instagram account – as more than 1.5 billion people do – joining Threads just required down downloading an app to your mobile phone, no registration necessary.

(note 2)

(note 2)

Facebook had some giant scaling advantages that startups like Blue Sky and Mastodon lack. Facebook’s servers are built to handle hundreds of millions of simultaneous users. So, an adoption curve that would have destroyed most startups came off with a hitch. More important, perhaps, Instagram already had support for a private social graph, the ability for people to follow some users and not others, which is the tricky part of building a social network.Threads appears to be a reskinned instance of Instagram, which means that we’re not dealing so much with the launch of a new social network, but the launch of a clone: it looks like Twitter, but it’s an Instagram clone under the hood.

There’s a few things to like about Threads. First, at the moment, it has no ads, as opposed to Twitter, which seems more cluttered by promotions each day. Perhaps this is a temporary state while the network is in its early phases, or perhaps it’s a loss leader strategy like Uber ran, offering rides below costs to build up userbase and destroy local taxi industries. Facebook might be willing to lose money by running Threads ad free for quite some time if it knocked Twitter out of the market. And Elon has made it clear that he’s seeking revenue through the most desperate means possible. So let’s approach the ad-free status with a note of caution – it’s likely temporary, possibly a hardball business tactic and is being introduced by a man who’s name is synonymous with surveillance capitalism.

Second, Threads promises to support ActivityPub, the protocol behind open social networks like Mastodon. I am comfortable saying that this would be a good thing. Even if Threads became an enormous Mastodon node with a billion users, it would be a benefit for an ecosystem where adoption has been lower than we might have hoped, in part because of low usability. If Facebook’s good at one thing, it’s usability. And perhaps Threads joining ActivityPub would be a good kick in the pants for the rest of the space.

However, Threads is not yet on ActivityPub, nor have they said when they will be on ActivityPub. Making Instagram’s social graph, with all its accompanying privacy settings, work on ActivityPub is non-trivial, as the techies like to say. It’s certainly possible that the network will remain backended on Instagram for the foreseeable future so long as Zuckerberg and crew are able to claim credit for engaging with the world of open standards.

Third, and perhaps most important, Threads is not Twitter. That’s a serious plus these days, as Twitter is run by a crazy person who seems determined both to turn the site into a far-right partisan network, and to make the tool entirely unusable, perhaps at the same time. A Twitter with more predictability and fewer Nazis would be a very good thing. Many of us, myself included, miss the existence of a “big room” social space where voices could jockey for attention and social movements could take hold. By tipping Twitter in a decidedly partisan direction, Elon has made Twitter a lot less useful and a lot less welcoming.

But before we toast the new non-Twitter, let’s pause for a moment and remember Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t have a a terrific track record in running responsible social networks. In particular, Facebook has been an extremely dangerous and divisive tool, especially outside of the United States. Facebook’s own reports confirm that the network helped the government of Myanmar in a genocidal campaign against its own people.

Facebook may now recognize that it is ill-equipped to fight propaganda, mis-and-disinformation, and incitement to violence in languages that most of its staff do not speak, and where it has not invested heavily in local trust and safety teams. Threads is not yet available in the EU, where it may not comply with EU privacy rules. Perhaps it would have been wiser to open only in a few English-speaking countries, where it is best positioned to moderate content. But even if Threads were only in the US, it is likely to face serious moderation challenges We are heading towards a 2024 US election likely to be riddled with disinformation as it features both Donald Trump and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Facebook, which fears both being seen as a disseminator of disinformation and criticism from the right for “censoring” speech may have just taken on a moderation challenge it will live to regret.

Still, isn’t a non-Elon, less crazy, relatively Nazi-free social network worth celebrating?

No. No, it’s not. This is the wrong way to build the future of social media.

The lesson we should have taken from Elon’s destruction of Twitter is that online public spaces are too important to hand over to capricious billionaires. They are too important to be supported solely through targeted advertising. We need new models for how these spaces are moderated, governed, and supported. (My lab is exploring one of these models, and we acknowledge and celebrate others as well.)

Mastodon, which offers a blend of smaller, locally governed online spaces and the ability to host “big room” conversations across multiple nodes, has been exploring a model in which local control and local fiscal support replaces a single set of content standards and an advertising model.

My lab at UMass is experimenting with small, community-based social networks and highlighting other topic-specific projects from subreddits, to special purpose networks like An Archive of One’s Own.

This would be a wonderful moment to see a flowering of alternatives to Twitter. But it would be great if those alternatives used a different business model than Twitter’s model, and if they weren’t controlled by a capricious billionaire.

(h/t to Nathan Schneider for pointing me to this.)

Here are some things not to like about Threads. At the moment, it’s mobile only. That’s a little frustrating for pathetic social media geeks like me, who are cutting and pasting updates to Twitter, Mastodon, BlueSky and now Threads, flipping through our tabs to connect with different audiences on different networks. (This is a problem Gobo hopes to solve, if only Reddit and Twitter would stop screwing with their APIs.) But mobile-only is a real problem for people who use screen readers or other assistive technologies. And mobile-only means it’s very difficult for helper apps like Block Party – which gave Twitter users greatly improved blocking tools, until Elon made their API keys unaffordable – to work with Threads.

Threads without a web interface also makes it much harder for scholars to analyze and study. When we research the spread of mis/disinformation on social media platforms, we use APIs to retrieve large volumes of posts when possible, and “screen scraping” – parsing the HTML a website sends to a web browser – when we don’t have API access. Facebook is legendary for making their HTML hard to scrape, for taking legal action against people who try to scrape data, and for offering only limited information through their APIs. Offering a tool that’s mobile only makes researching even harder, and suggests that transparency isn’t going to be a top priority for the product team.

Second, at present, Threads does not offer a reverse chronological feed. What you get instead is an algorithmically driven feed that combines Instagram influencers trying out the new platform with the people you are actually following. This suggests that Threads will go the way Twitter has been trying to go, realizing that the power of putting content in front of users is one of the main privileges of running these platforms.

Personally, I think any social network should be required both to give you the option of a reverse-cron feed and to allow you to pipe that reverse-cron feed into your own client where you can search and combine social media along your own rules – that’s the point behind the Gobo project. Facebook historically has been one of the worst networks to work with on projects like this – they’re highly resistant to third-party tools interacting with their data. And they’ve got a point: because Facebook works on a private protocol – i.e. your expectation that your post might only be shared with your friends – they are able to argue that these cannot be studied by researchers in the same way that tweets can, and that third parties will have to work hard to comply with Facebook’s privacy standards in building a third party clients. I noted with some dismay that when I signed up for the service yesterday, I had a choice between posting publicly or posting just to my friends. In other words, Facebook is going to extend its privacy graph into this new space.

So we’ve got a new social network that looks a lot like Twitter run by the company that largely invented surveillant ad targeting in social media. It’s got a content algorithm that is currently inescapable. It’s mobile only, making it very hard to modify, use with a helper app or study as a researcher. And it’s run by a company that has a lousy track record of protecting vulnerable users, preventing misinformation and abuse, and listening to community needs.

So no, I’m not celebrating. I don’t want Facebook to build a better Twitter and kill off a possible wave of experimentation in this space. We should have different tools with different models for different communities. But Facebook has rarely played well with others.

If you’re working on Threads and want to prove me wrong, here are some steps you could take.

– Open an API to threads that allows me to build a third party client – I would love for Gobo to support Threads alongside Reddit, Twitter and Mastodon.

– Clearly document how Threads expects researchers and third parties to deal with private posts – will we be allowed to build clients that operate only with public accounts, or with private ones as well?

– Fast track ActivityPub so we can see what adding a huge Facebook node within a Mastodon ecosystem is going to look like.

– Share some information about how Facebook plans to deal with predictable waves of propaganda and mis/disinformation on this new platform, particularly in countries and languages where Facebook does not have a strong presence.

In response to the inevitable comment, “it’s brand new, you can’t expect everything on day one”, I call bullshit. This is a new product from a massive company that should have a better understanding of the problems and limitations of social media than any other business in the world. If Facebook hasn’t considered moderation questions in detail, or have internal answers about prioritizing ActivityPub, that’s a very serious oversight on their part.

My worry is that Facebook has, in essence, accepted Elon Musk’s cage match invitation. (Like most of the rest of you, I would be rooting for the cage in that match.) What I fear is that Facebook has quickly developed a Twitter clone without considering just how much trouble this will get them into in the 2024 election cycle. I worry that all of us who desperately miss Twitter are embracing this new space without thinking about the social media universe we really want: one where we control what we see and read, one where we have a voice in governance. It’s not enough to have a space that is better than Elon’s, as much as we desperately need that.

(1) I’m referring to the large, publicly traded social media company founded and run by Mark Zuckerberg as Facebook and not as Meta. Facebook attempted to rebrand as Meta because growth of the Facebook product has slowed, because Facebook was associated with privacy violations, poor content moderation, mis and disinformation and numerous other scandals. Much as RJ Reynolds wanted to become Altria, becoming “Meta” was not just about embracing a crappy version of a metaverse, but running from some bad history. Given that Threads raises all the questions about content moderation, disinfo, etc., it’s important that we discuss it as a Facebook product.

(2) Yes, this is a screenshot. Why? Because Elon broke tweet embedding. Yes, I know it works today. But he’s broken it once, and I see no reason he won’t do it again.

The post Competition for Twitter is good. Threads, thus far, is not. appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

March 7, 2023

Elon Musk’s Compelling Case for Worst Human of 2023

There’s a saying that you never want to be the main character of Twitter. If you are, it usually means you’ve humiliated yourself in a particularly embarrassing way.

The exception to this rule is Elon Musk, who seems to thrive on attention, positive or negative. As has been widely reported, Musk threw an epic temper tantrum when the President of the United States was receiving more attention than he was in making a tweet about the Superbowl, and responded by ordering Twitter engineers to massively amplify the reach of his tweets.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) February 14, 2023

Most normal human beings would be embarrassed to be seen as using their wealth and power to nakedly boost their visibility. Not Musk. He posted a meme that’s both extremely creepy (and arguably a reference to white nationalism) to defend his practice of bottle-feeding Twitter users his very important reflections and perspectives.

But Musk’s ability to self-own is exceeded only by his capacity for cruelty. When an employee took to Twitter to ask Musk to confirm whether or not he’d been fired – because Twitter’s decimated HR department could not answer his questions – Musk proceeded to offer a brusque exit interview on his very public Twitter feed. The fired employee had the temerity to be a designer, a class of people Musk perceives as parasitic bottom feeders, and so perhaps the hostility of the interview was to be expected.

– Level up from what design to what? Pics or it didn’t happen.

– We haven’t hired design roles in 4 months

– What changes did you make to help with the youths?

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 7, 2023

Would you say that you’re a people person?https://t.co/kLD9NWHVIT

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 7, 2023

One of Musk’s followers found the exchange humorous and told Elon as much. Elon explained his wise management decisions: since the guy was claiming a disability, surely he couldn’t be typing tweets to him. And anyway, he didn’t do any work (remember, he’s a designer) and was independently wealthy anyway.

The reality is that this guy (who is independently wealthy) did no actual work, claimed as his excuse that he had a disability that prevented him from typing, yet was simultaneously tweeting up a storm.

Can’t say I have a lot of respect for that.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 7, 2023

In a turn of events that must have come as a surprise to absolutely no one, it turns out that the employee Elon was abusing for his amusement was an actual human being. His name is Haraldur Thorleifsson, and he has a fascinating backstory, a very real disability, and a fairly wicked sense of humor.

My legs were the first to go. When I was 25 years old I started using a wheelchair.

It’s been 20 years since that happened.

In that time the rest of my body has been failing me too. I need help to get in and out of bed and use the toilet

— Halli (@iamharaldur) March 7, 2023

The bathroom reference refers to Elon posting unfunny memes about spending an hour on the toilet reading Twitter. Halli, as he prefers to be called, goes on to explain that his muscular distrophy makes it difficult for him to manipulate a mouse and that he no longer works as a production designer, but focuses on strategy. He can type for periods of time, particularly on his phone (making it possible to tweet at an employer who is no longer providing the very basics of HR services to his employees.)

As for the “independently wealthy” thing:

We worked for more or less every big tech company.

We grew fast and made money. I think that's what you are referring to when you say independently wealthy?

That I independently made my money, as opposed to say, inherited an emerald mine.

— Halli (@iamharaldur) March 7, 2023

Twitter, under Jack Dorsey, bought Halli’s firm and he survived several rounds of layoffs, until – perhaps? – this most recent one. (I loved the emerald mine dig in there. It followed several lines about how Halli gets along with his wife and enjoys time with his kids.)

So yes. Elon Musk picked a fight with a wheelchair-using Icelandic entrepreneur with muscular distrophy on a public twitter thread, hoping to humiliate a parasitic do-nothing employee, and instead revealed the damage done as he continues to smash his $44 billion toy against the pavement because it doesn’t make him feel as good as he hoped it would.

Why is this particular bit of Muskiness worth even paying attention to?

In a 2018 essay in The Atlantic, Adam Serwer coined the phrase “the cruelty is the point”. Serwer was talking not just about Trump, but about a larger pattern of dehumanization in which people – almost exclusively white men – bond through “…intimacy through contempt. The white men in the lynching photos are smiling not merely because of what they have done, but because they have done it together.” Serwer’s phrase has become a point of conventional wisdom about the contemporary Republican party, and rising star Ron DeSantis seems to have embraced cruelty as a governance strategy, kidnapping migrants to the US and depositing them in a small Massachusetts community with few resources to help them. (Rather than freaking out as DeSantis hoped, the citizens of Martha’s Vineyard mobilized to feed and shelter the mostly Venezuelan migrants and help them find paths to settling in the region.)

Musk was once a widely admired business leader: Gallup’s Most Admired Man and Woman poll in 2020 had him ranked 6th, just behind Pope Francis. (He edged out the Pope for 5th in 2019. The poll was not held in 2021 or 2022, likely because there is no longer anyone worth admiring.) Even as he took over Twitter, there were cadres of Musk fanboys willing to defend his management genius in excising the fat from the community and giving the remaining engineers (mostly those unable to leave due to visa issues) space to shine. My guess is that some continue to feel that Musk’s cruelty reflects his ability to see the world as it “really is”, where useless people like designers and disabled people drain energy from the engineers who really build things. (Try building usable technology without designers.)

It's like VC qan*n, and it colors almost everything they see and do in culture, politics and business. We're going to see more and more irrational, extremist decision-making that can only be understood through this lens.

— @anildash@me.dm and anildash.com (@anildash) November 22, 2022

Anil Dash, who’s much closer to these things than I am, observes that Elon’s pivot to fascism echoes behavior he’s seeing in several other tech entrepreneurs and VCs. These people genuinely believe that attempts at creating better workplaces for employees, to increase diversity (in part to increase cognitive diversity and better solve problems) are attacks on their “rights” to manage their enterprises in arbitrary and cruel ways. What’s more disturbing to me than billionaires losing their mind is the young people who aspire to similar success and embrace similar attitudes as part of idolizing Musk. (British educators are finding rising misogyny in their male students based on their admiration for MMA fighter, asshole and likely sex trafficker, Andrew Tate.)

At moments like this, it’s worth recognizing people who actually deserve to be admired. Consider this guy: when he sold his company to an American firm for millions, he chose to take the payment as salary, rather than as capital gains so he would be taxed at a higher rate, pushing money into his country’s economy. He is spending some of the money he earned building wheelchair ramps to make public spaces in his city more accessible. His country, Iceland, voted him Person of the Year in 2022.

His name is Haraldur Þorleifsson and Elon Musk just fired him over Twitter.

The post Elon Musk’s Compelling Case for Worst Human of 2023 appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

February 20, 2023

New writing!

It’s been a good winter for writing… or in some cases, a good winter for writing I did months ago to see the light of day. Here’s a few pieces I’m especially proud of and which may be of interest to you, depending on whether you follow me for insights on social media or just for the wedding photos.

A Social Network Taxonomy: Is Mastodon a replacement for Twitter or something entirely different? That’s a surprisingly complicated question. Looking for an answer, and talking with friend Tom Tyler, Tracey Meares, Eli Pariser and Deepti Doshi, I found myself playing with some new ways to characterize social networks: Do they feel like they are a single room, or many separate rooms? And are they controlled by one person, or do many people have control?

What results is a 2×2 matrix which gives a simple way to talk about some of the complexities of governing and moderating social media. And better language to talk about social media is a step away from fixing existing models of social media and towards embracing a pluriverse of social media where different communities work differently for different purposes: A Social Media Taxonomy

In a real sense, this piece is an extension of what Chand Rajendra-Nicolucci and I started doing with An Illustrated Field Guide to Social Media. We’re hoping to revise and reissue the book in the next year – we’re talking with a publisher about a new print edition and an online edition that gets revised over time. In the meantime, your best bet is the edition hosted by the Knight First Amendment Institute.

Creating PublicSpaces: My friend Geert-Jan Bogaerts is the CTO of one of the Netherland’s public broadcasters, VPRO. A few years ago, he realized that he was in a bit of a moral quandry: tools he needed to use, like Google Analytics, conflicted with the values of his organization, notably values around user autonomy and independence. Can we justify putting users under surveillance so we can measure how effective our programming is? Is it wise to push people towards corporate controlled spaces like Facebook to have conversations about Dutch public broadcasting?

GJ ended up co-founding a collective of Dutch broadcasters and cultural organizations, who took on the work of auditing their software use and identifying tools that came into conflict with their values. With José Van Dijck, we wrote up the PublicSpaces origin story, and investigate whether the model of aligning software with the principles of “values-led organizations” might create a new market for open source and socially responsible software. (Needless to say, this has important implications for social media platforms.) We believe values-led organizations in Europe might be the next leaders of a movement towards software we can feel good about and tools we have a role in governing: Creating Public Spaces

How social media could teach us to be better citizens: In 1995, social scientist Robert Putnam suggested that American civic life was weakening because people were retreating from public spaces. Putnam’s critique, expanded in his book Bowling Alone, is often cited by people arguing that online interactions are weakening American society. But there’s an intriguing possibility: local organizations from bowling leagues to men’s lodges, Putnam believed, were helping train citizens in the mechanics of civics. People learn to run meetings, to find agreement, to argue respectfully and helpfully.

Could we gain some of these same lessons from participating online? Probably not, unless we are involved in the actual governance of online spaces. If we consider communities like Reddit, where individuals are invited to moderate communities, perhaps there is a path towards rebuilding civic skills through online spaces. This paper is the beginning of a larger argument I’m hoping to make, which argues that the public sphere includes places to find news, places to discuss that news, and tools that help train us in civic participation: How social media could teach us to be better citizens

In addition to these academic (and academic-adjacent) articles, I’m continuing to write a monthly column for Prospect (UK) about whatever catches my eye in the tech world. There’s about a month’s turnaround from when I start writing to when these run online, so they can seem a bit behind the curve sometimes, particularly around crazy-fast issues like the collapse of Twitter. The articles are all linked here and my next article, on ChatGPT and propaganda is coming soon.

Thanks for reading!

The post New writing! appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

January 18, 2023

Empagliflozin (Jardiance) and Type 1 diabetes – a patient’s perspective on SGLT inhibitors

Hey, this is one of those blog posts intended for search engines more than for the casual reader… unless the casual reader happens to be a type 1 diabetic. I have had type 1 diabetes for more than 35 years, and a month into taking empagliflozin, it’s the biggest transformation I’ve had in my diabetes management experience. It’s been something of a miracle drug for me, and I wanted to share my experience for other type 1 diabetics who are in tight control, but seeking lower insulin doses and, possibly weight loss.

I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age 13, and am now fifty. Like many young diabetics, I did a shitty job of managing my disease until my early twenties, and I experienced some serious consequences, notably significant problems with diabetic retinopathy. For the past 25 years, I’ve been in tight control (A1C below 7, often between 6-6.5) and have been able to manage my diabetes through world travel, unpredictable eating and sleep schedules, etc.

About five years ago, I moved towards using Tresiba as my basal insulin, using Humalog as a short duration insulin. I also moved to continuous glucose sensors. I was able to get much tighter control than I’d experienced with Lantus and Humalog, but it was a very brittle equilibrium. That is to say, I had to eat a very strict low-carb diet, and minor deviations would mean additional insulin.

I changed doctors about half a hear ago when my long time primary care physician retired, and my new doc found me an excellent nurse practitioner who works at a local (Pittsfield MA) endocrinology practice. My new NP talked with me about my diet, exercise, glucose monitoring, etc. and said, “Hey, we don’t recommend this for most patients, but it might work for you.”

The regimen he was recommending was 10mg daily of empagliflozin, a drug commonly used to help with type 2 diabetes. It’s a sodium glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor, which is to say, taking it helps remove sugar from the bloodstream and move it to the urine. This is a phenomenon virtually all type 1 diabetics are familiar with – if your blood sugar is hight, you’ll get thirsty and need to pee. For me, that usually happens at about 240 mg/dl, a level at which I’d usually take a supplementary insulin dose. With empagliflozin, that experience happens at much lower blood sugar levels – around 150 mg/dl in my experience.

My NP suggested I’d need to adjust my insulin needs down, and he was right – WAY down. I am using 75% as much Tresiba as a basal dose, and I am taking 60% as much insulin with each meal. Despite cutting insulin significantly, I have far more flexibility than I used to have with my diet. I’ve cautiously let some carbs back into my diet, having a sandwich on two slices of bread rather than a low-carb wrap, for instance, or a small amount of brown rice with a curry.

What’s been most notable to me is a marked decrease in appetite. This may not purely be from the empagliflozin, as I’m also working on getting my thyroid levels under control. But insulin is known to be associated with weight gain, and I’ve steadily gained weight over the many years I’ve been managing my diabetes. It’s too early for me to say whether I’m experiencing significant weight loss, but my energy is great, my appetite is down, and it’s been much easier to control my sugars despite taking significantly less insulin.

In other words, the last month on empagliflozin has been like playing type 1 diabetes on easy mode. In exchange for drinking a bit more water and peeing a bit more, I have way more flexibility in what I eat, reduced appetite and increased energy. Yes, I’ll take it, thank you very much.

So why isn’t empagliflozin widely prescribed for type 1 diabetics. Well, it is, in Europe. Specifically, Europeans are using SGLT-1 inhibitors (which helps absorb glucose in the gastrointestinal tract) as well as SGLT-2 inhibitors (which focus on the kidneys) for type 1 diabetics who are overweight or obese (that’s me!) In 2019, a small study in Spain saw promising results, as have larger international studies.

So why has the FDA refused to sign off on empagliflozin for Type 1 diabetics in the US?

Ketoacidosis.

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) occurs when your body doesn’t have enough insulin to process glucose into energy. The body begins breaking down fat for fuel, producing ketones in the process. The ketones build up in the blood and begin to turn the blood acidic, which has severe and widespread health consequences. DKA was the cause of death for almost all type 1 diabetics before the development of insulin, and still leads to hospitalization and sometimes death for a significant number of diabetics (about 220k hospitalizations and 835 deaths in 2017).

The FDA is concerned that SGLT-2 inhibitors will increase the chances of DKA in patients who stop taking insulin, incorrectly take a dose (pump failure, pen failure), who become dehydrated or have another significant health issue, like infection. I am not able to find studies that show a significant increase in DKA episodes for patients with type 1 taking SGLT-2, but that’s not surprising – the experiments done have been quite small, and DKA is not a routine experience for most diabetics. What this suggests is that FDA is being cautious, concerned that the increased risk of DKA doesn’t justify the benefits of reduced blood sugars, weight loss, etc.

I found this piece, which is extremely cautious as regards use of SGLT-2 in type 1 patients to be especially helpful, because it summarized the stakes so neatly:

“Recent data from the T1D Exchange (T1DX) registry (1), which comprises leading U.S. diabetes treatment centers, show that despite the widespread availability of insulin analogs and increasing use of insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitoring systems, only about 20% of adult patients achieve the A1C target of <7% (53 mmol/mol) recommended by the American Diabetes Association (2). It is reasonable to assume that glycemic control of patients receiving care outside of major centers might be even worse… There is clearly an unmet need for noninsulin adjunctive therapies that improve glycemic control without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia or contributing to weight gain, and it is noteworthy that among nearly 50,000 pediatric and adult participants in the T1DX registry in the U.S. and the Prospective Diabetes Follow-up (DPV) registry in Germany and Austria, two large consortia of diabetes centers, adjuvant medications are being used off-label by 5.4% of participants in T1DX and 1.6% in DPV (5).”

In other words, type 1 diabetes sucks, and most people can’t manage it within ADA’s guidelines, even with pumps, continuous glucose monitors, etc. And so an increasing number of folks are using off-label adjuvant medicines, like SGLT-2.

I wanted to write something about my positive experiences with SGLT-2 and type 1 because I simply couldn’t find another patient account on the web. I am not a doctor, certainly not an endocrinologist, and my experiences may not be your experiences. For that matter, my experiences after a few months on this regimen may be different than my experiences one month in. But, if your diabetes is in tight control, if you rarely have blood sugars above 240 mg/dl, if you’re overweight and having trouble losing weight, you might want to talk with your diabetes doc about SGLT-2 drugs.

The post Empagliflozin (Jardiance) and Type 1 diabetes – a patient’s perspective on SGLT inhibitors appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 28, 2022

Legacy Cities: an extended remix of my talk at PopTech 2022

I often write out my talks when I am presenting new material – my “live performances” can differ substantially from what I meant to say, depending on how my brain is functioning on any given day, so I feel like it’s useful to share what I meant to say. This time, though, I have other reasons for sharing my text: I had so very much more that I wanted to say.

I wrote a blog post earlier this year about a road trip Amy and I took to a number of “legacy cities” around the eastern Great Lakes. Leetha Filderman, who organizes the PopTech conference, read the post and asked if I’d be interested in developing it into a talk, using the images I’d taken along the way. I had some anxiety about this: I am not an urban planning scholar, and I don’t want to be the guy (always a guy) who wades into someone else’s field with insights about a subject I know nothing about.

So I told Leetha that I would find a way to tie legacy cities to the communities I study online, so that I wasn’t entirely out of my lane. And I told her I planned on shouting out all the books I’ve been reading about legacy cities and pointing people to actual scholarship on the topic.

And then two weeks ago, she told me that all talks at PopTech this year are 8 minutes long.

As you probably know, it takes most academics eight minutes to say hello and introduce themselves. So I had to take a different approach. I prepared a quick, extremely visual talk that should be available on YouTube soon. And I put all the stuff with subtlety, complexity and nuance in the footnotes. Here are those footnotes.

Rochester, NY

It was the third summer of the pandemic and I wanted to rent a van and camp on beaches and generally act like a twenty year old instagram influencer, and my wife pointed out, "We don't camp." "What _do_ we do?", I asked her. "We go to art museums, photograph collapsing buildings and eat cheap ethnic food."

Which is all true, and which is why we went on vacation to Utica, New York. We went to Rochester and Syracuse, and Buffalo and Detroit and Toledo and Cleveland and Erie, too, with a romantic detour to Love Canal. We went to cities that are rarely vacation destinations, that are more likely to be punch lines of jokes. (1) These cities hit their peak population sometime between 1950 and 1970 and have been shrinking since then. (2) In many cases, they've burned, as absentee landlords hired kids with gas cans to torch their houses for the insurance money. (3)

1) To be clear, we’re not beyond humor either – we listened to Randy Newman’s “Burn On” as we drove alongside and over the Cuyahoga River. (Not to mention “Love Canal” by Flipper.) And part of the appeal of the trip was the looks we got from our friends when we told them where we were going on the trip. In truth, though, a significant chunk of this drive was a repeat for us. When Amy moved to the Berkshires from Houston, we took a week to drive up the Mississippi, and discovered to our surprise that the standouts from our trip were Cleveland, Buffalo and Corning, NY. Given our fondness for those cities based on a brief visit, why not design a whole vacation around them?

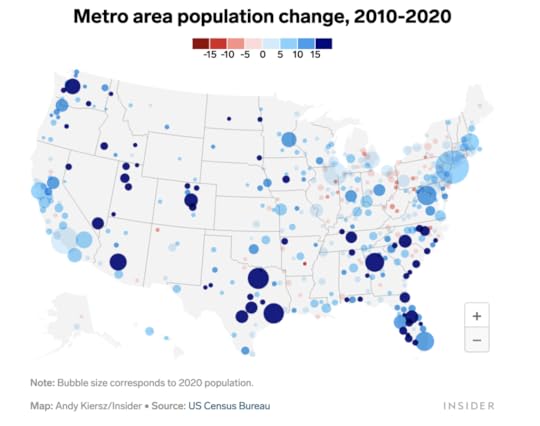

2) It’s more complicated than that, obviously. Some legacy cities continue to shrink – Detroit’s population is smaller in 2020 than in 2010, and roughly a third of its peak population in the 1950 census. Others are rebounding: Utica is larger in 2020 than 2010, and appears to have bottomed out in 2000. Amy and I tend to glance at the Wikipedia page for cities we’re visiting, and flip immediately to the demographics section. If the population peaked in the 1950s – 1970s and is significantly lower now, it’s likely a post-industrial legacy city, and a place we would enjoy visiting. (Perhaps it’s not a surprise that we live on the outskirts of Pittsfield, MA, where the population peaked in the 1960 census, is now at 75% of peak and continues to shrink.)

3) It was fascinating and horrifying to realize what a common theme the burning of cities was throughout the trip. I’ve recently read Joe Flood’s “The Fires”, both because I’m fascinated by the history of The Bronx and by the incredible example of RAND’s model for how to optimally fight fires in NYC failing dismally when faced with the political realities of closing fire stations. (Yes, RAND’s models made unsupportable assumptions about NYC traffic, but it’s likely that impacts were more severe from political pressures to keep fire stations open when they happened to be located near influential politicians.)

We read a great deal about the fires in Detroit on our trip. The Devil’s Night fire tradition – in which vandals burned abandoned buildings on the eve of Halloween – in Detroit seems to have finally ended, but it’s amazing to consider the scale of the phenomenon. In 1984, 800 buildings reportedly burned across the city in a single night. Reading about Tyree Guyton’s Heidelberg Project, I was struck by how many of the buildings he transformed were either burned by arsonists, or destroyed by the city. And while the fires on the Cuyahoga river are a bit of history I knew before the trip, I had not known about the Hough Riots, in which many Black-owned properties burned.

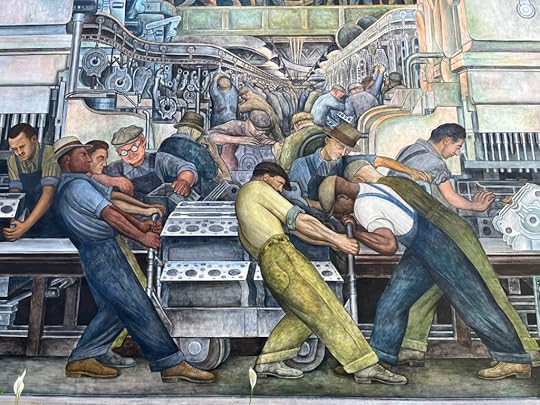

Detail from Diego Rivera’s “Detroit Industry”

Planning the trip, we called it "the rustbelt ramble", but somewhere between Utica and Rochester, we started using the term "legacy cities" instead (4). The splendid buildings, the museums, the parks, the cemeteries are a legacy bequeathed by an older America to her grandchildren. The US park service makes passports to let us collect visits to National Parks: we need a legacy city passport where you get a stamp for seeing Diego Rivera murals in Detroit, George Eastman's House in Rochester or eating beef on weck in Buffalo.

4) The term “legacy city” appears to have been coined by the American Assembly of Columbia University, as a more representative term than “shrinking cities” or “post-industrial cities”. The American Assembly’s definition included cities of 50,000 or more, with greater than 20% population loss. Pittsfield, for instance, falls outside this definition as population loss now means we’re below 50k… Researcher Alan Mallach identified 48 cities that fit these criteria, and they are clustered in the Northeast and the Midwest. A few southern cities make the list – Birmingham, Macon and New Orleans – as do some surprising coastal cities – DC and Baltimore. But post-industrial upstate NY and midwest (Ohio, PA, Michigan) have the highest concentration of these places. See 2015’s Mapping America’s Legacy Cities for more.

Mallach edited the book I’ve found most helpful on legacy cities thus far, “Rebuilding America’s Legacy Cities”.

But I'm an old software developer, and I know that "legacy systems" are old, outdated code that's incompatible with current systems (5), and that's true of these cities too. As cities shrink, there's fewer people to pay taxes to support infrastructures that were meant to serve two or three times as many people as live in Cleveland or Detroit today. And so legacy cities feel weird - they feel empty, abandoned, unsuited to this moment in history.

5) The term “legacy systems” was everywhere in the 1990s when I was a software developer and a manager of developers – I’ve gotten some blank stares when I’ve bounced the term off contemporary developers. Perhaps it was a particular concern pre-Y2K – I am old enough to remember taking the Y2K bug very seriously and trying to ensure our systems would switch millenia without significant downtime.

I study online communities, and one thing my colleagues and I have learned is that every community contains within it a vision of the good life, the way things ought to be. Facebook assumes the good life is one where the people we know online are exactly the same as the people we know offline. Twitter assumes that we all want to be on the news, as reporters or commentators. YouTube assumes we are all reality TV stars. These assumptions about what constitutes a good life online structures their affordances, the possibilities they make available to us.(6)

6) Chand Rajendra Nicolucci and I wrote a brief book – An Illustrated Field Guide to Social Media – based on the idea that different platforms have different “logics” for how they operate. As we’re revising and expanding that book, I’m wondering if those logics are better understood as visions of what social media is supposed to be… and how that maps to the idea of cities and the good life. I don’t know whether this mapping between communities and cities is one I’ll want to explore long-term, but it’s helping me think about my obsession with legacy cities and the ways they differ from rapidly growing American cities.

Section of the Heidelberg Project, Detroit, MI

Legacy cities feel weird because they represent an earlier vision of the good life, one where you aspired to a union, factory job, a small house in a neighborhood with local stores and streetcar lines, where your kids walk to school. Many of us gave up on that vision of the good life sometime in the 1970s, as jobs moved to the non-union south and eventually to Mexico, where people moved from Toledo to Florida and Texas and Arizona, where the good life means you can ignore the physical world, that you never need to be hot or cold, that you can have as much space as you could want.(7) Orlando and Houston and Phoenix, fast-growing cities that are only possible due to the automobile and air conditioning, are less densely populated than Detroit, even after Detroit lost 2/3rds of its population.(8)

7) The cities that grew the most in the 1990s – present have been in the South and the Southeast. Florida, Texas and Arizona>, in particular, have grown explosively. This seems increasingly strange to me as climate change threatens to make these locales less desirable (at least to me, but I actually like snow.)

There’s tons to read about the anti-union South. This article from Ken Green at UnionTrack offers some reasons: as the north industrialized, the south often positioned itself as agricultural and opposed to unionization. Racial dynamics came into play as well – when white workers went on strike, Black workers were brought in (and fired when the strike was broken), making it hard to achieve solidarity between Black and white workers in the same factory. This excellent piece by Meagan Day on a failed union effort in Winston-Salem in 1946 looks into the racial dynamics of union opposition in detail.

8) Densely packed northern cities like New York City, Boston and Chicago have densities of more than 10,000 people per square mile. Detroit was that dense in its heyday, but in losing 2/3rds of its population, it now has the density of a newer city like Las Vegas, close to 5,000 people per square mile. New, rapidly expanding cities like Phoenix and Houston are between 3,000 – 4000 people per square mile. Some cities that have boomed recently – Jacksonville, FL, Nashville, TN – are even sparser at 1500 people per square mile. It’s amazing to think that Detroit could lose two out of three people and still be denser than many Southern cities.

Detail from Dabl’s African Bead Gallery and Mnad Museum, Detroit, MI

What this means is that legacy cities belong to the people who stay and for the people for whom they still represent a better life. Detroit has become a Black city, roughly 80% African American, and from restaurants and art galleries downtown to abandoned houses converted into Afrofuturist wonderlands, it's clear that the Detroit version of the good life is a lot more vibrant than a Starbucks on every corner.(9)

In 2021, 77.1% of Detroiters classified themselves as “African American Alone” and 14.4% as “White alone”. That’s a pretty neat inversion of the demographic split in the US as a whole, which is roughly 76% white, 14% Black.

I am reading Herb Boyd’s excellent “Black Detroit: A People’s History of Self-Determination”. And I was struck by how many of the rebuilt landscapes I saw in Detroit read to me as Afrofuturist, particularly Olayami Dabls’s amazing Mbad African Bead Museum, which is one of my favorite places in the world. That this place is not an international pilgrimage destination for arts fans is a crime. I had the pleasure of talking with Dabls on my last visit to Detroit. He became a collector of African beads not by travelling to the continent, but by building friendships with travellers who brought drums, clothing and other cultural goods from Accra and Lagos to the Black community in Detroit, Chicago and other midwest cities. Dabls is enormously grateful to those travelling merchants for building a connection between his experience in Detroit and the cultural heritage of the African continent.

Rohingya Masjid in Utica, NY

Utica is a refugee city - it welcomed Amerasian refugees from Vietnam in the 70s and 80s, Bosnians fleeing civil war in the 1990s. It has welcomed a wave of Karen refugees from Burma and Somali Bantu people from Somalia and Kenya. The city is no longer shrinking and the population is more than one quarter refugees. Which means that the former Methodist church is now a Bosnian mosque, and that the restaurants are Somali and Cambodian and Dominican. (9) Hamtramck, a suburb of Detroit, is now America's primarily Muslim-governed city, thanks in part to Iraqi and Syrian refugees displaced by ISIS. (10)

9) Utica rocks. It’s one of the smallest cities I’m discussing in this talk, and the one closest to where I live – it’s a little more than a two hour drive for me. The NPR radio station I listen to serves Utica as well, so I get occasional glimpses of what’s going on culturally, and it’s wonderful to be able to visit as a day trip.

Susan Hartman has an excellent new book, “City of Refugees”, which tells the story of three refugee families and their lives in the city. Earlier this summer, the New York Times ran an excellent essay and photo series based on her reporting. (We were in Detroit when it came out.) A quick TL:DR; on why Utica has been such a great town for refugees – affordable housing (lots of multifamily houses on the market for $60k – live upstairs, rent the ground floor to your countrymen); local employers willing to hire refugees (Chobani yogurt, local casinos); supportive religious community (Bosnians building a religious infrastructure that’s made it easier for Iraqis, Rohingya, Somali Bantu populations.)

10) Hamtramck is historically a Polish immigrant community, and until 2021, every mayor had been Polish-American. But there’s been massive growth of the Bengali and Yemeni populations, as well as refugee populations in both Hamtramck and Dearborn, and Hamtramck now has a Yemeni Muslim mayor and a Muslim majority city council.

My lab at UMass studies refugee spaces online, too. When your interests or your politics are too outside the mainstream for Facebook, you end up building your own, new spaces online. When sex workers got kicked off of Craigslist and Backpage shut down, a few of them built switter.at - sex worker Twitter - a space designed by sex workers where they could share information about problematic clients and create a safer space for their work online.(11) My colleagues and I tend to think refugee communities online are the most dynamic and informative spaces we study. Rather than following the logic of the marketplace - one size fits all communities for a billion people - spaces for refugees online develop their own cultures and technologies based on what people want and need. These spaces are not all the same - they're a petri dish evolving different ways to live online.

11) I have written about Switter in my essay, The Good Web, and interviewed two of the project’s founders on Reimagining the Internet.

American Riad, an indoor/outdoor space in Detroit, MI.

That's something we could use in physical space, too, whether it's Moroccan riads transforming Detroit streetcorners or a global food mall in Buffalo.(12)

12) I’m grateful to my friend Hasan Elahi for directing me to the American Riad, a gorgeous effort to reimagine a stretch of houses in Detroit as an indoor-outdoor space inspired by Moroccan architecture. The project was incubated by the marvelous Ghana Think Tank, which sets up laboratories in developing nations to solve first-world problems.

The Global Food Mall in question is The West Side Bazaar, where I had my favorite meal of 2022 at a South Sudanese restaurant. Unfortunately, the Bazaar had a fire in late September and is now closed for rebuilding.

And we should take refugee cities seriously, because in the next few decades, a lot of us are going to become refugees. As the South gets hotter, the West gets drier, as coastal cities flood, my guess is that a lot of people will be leaving their home towns.(13) It's not hard for me to imagine what Phoenix might look like in a few decades, when the water runs out. I'm guessing it looks a lot like the Salton Sea, that magical resort in the desert an easy drive from LA, which is now abandoned and plagued with toxic dust storms. (14)

13) I have a document filled with footnotes about the increasing uninhabitability of the southern US, but this package of reporting from Pro Publica is an amazing overview.

14) A good start on the amazing saga that is the Salton Sea is this brief photo essay. If you’re hooked, try the documentary Plagues and Pleasures on the Salton Sea, narrated by John Waters.

Sandusky, OH

You what's gonna be a great place to live in about thirty years? The Great Lakes. They've got 21% of the world's fresh water.(15) The farmland that surrounds these legacy cities is projected to get more lush and productive. The extreme heat that will make America's fastest growing cities uninhabitable will be a whole lot more tolerable a thousand miles north.

15) Yep. 21% of the _world’s_ fresh water, and something like 90% of the fresh water in the US. It already provides drinking water for about 30 million US citizens and about 30% of all Canadians. And before you get the clever idea of piping Lake Superior to Phoenix, let me point out a) the Rocky Mountains and b) the Great Lakes Compact anticipates this and prohibits it.

But you should probably buy now. Because Pakistan is already under water(16) and there's Ukranians and Russians on the move. The cities Americans lived in from the 1860s to the 1960s turn out to be well suited to a world where we bike instead of drive, where we get on trains instead of planes, and where we look for cultural treasures and inspirations from our neighbors and from the institutions built by our grandparents rather than from overseas.

16) Even with photos and maps, it’s tough to understand the scale of flooding Pakistan experienced in 2022. The UN estimates that at least 33 million people – one in seven people in the country – have been displaced or otherwise affected.

Cleveland Arcade, Cleveland, OH

When you visit America's legacy cities, you feel eras in history beginning and ending. You move from canals to railroads to highways as you walk across town, from cotton mills to electronics factories to software startups. Like New York City, which burned and shrank in the 70s and 80s before once again becoming the capitol of the world, America's legacy cities will come back. I just hope you can find a nice Rohingya landlord willing to rent to you.

The post Legacy Cities: an extended remix of my talk at PopTech 2022 appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 22, 2022

Our wedding, October 7-9, 2022

Amy Price and I were married the weekend of October 7, 2022. We were legally married at the Pittsfield MA city hall so that our friend, Dr. Colin McCormick, could officiate our wedding on October 9. While Massachusetts has one-day solemnization certificates, Colin needed to participate via Zoom, and MA law doesn’t recognize virtual solemnization. And so, we got legally married on a beautiful fall day by the Pittsfield City Clerk as our friends were coming into town from around the world.

Our wedding included visits from our Texas friends to our home in Lanesboro, a tour of MassMoCA with sixty friends, a dinner and board game session at The Log on Spring Street in Williamstown, before a brunch wedding on Sunday the 9th at Greylock Works. Our wedding venue was an old “weaving shed”, which had been part of Berkshire Mills. Amy found a wonderful video of the mill in 1917, which we projected on one of the walls of the space.

[image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error]We invited friends to photograph the events for us and they did a brilliant job, though friends might been having too much fun during the MoCA visit and pizza dinner to fully document events. We are especially grateful to Andrew McLaughlin, who took video of the full event. We made it difficult for him at the end, when we rickrolled our own wedding and danced down the aisle for our recessional – McLaughlin was laughing too hard to always hold the camera steady.

“The Book of Love”, as performed by Cidnie Carroll, Amy and me

Rick Astley strikes again.

Two moments that I will particularly treasure were captured by Margaret Stewart – our friend Cidnie Carroll performing Magnetic Fields, “The Book of Love” with Amy and me, as well as the wonderful recessional Amy choreographed.

I’m grateful to all the friends who were able to make the trip to be with us and their efforts to document the event. I’m grateful to my parents for their help in paying for throwing a giant party And I am impossibly grateful to Amy for being my best friend, my partner, my favorite co-conspirator and now my wife. 16/10, A+++++++, would marry again.

The post Our wedding, October 7-9, 2022 appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

October 21, 2022

Five years sober.

Five years ago today, I quit drinking.

It wasn’t the first time. I took a year off from alcohol about ten years ago, mostly as a way to prove to myself that I didn’t have a problem with alcohol. After all, if I could spend a year sober, obviously I couldn’t have a drinking problem, could I? :-)

Turns out, my very real problems with alcohol center on drinking in moderation. Apparently I have two modes: either I don’t drink, or I drink significantly, every day. Faced with that choice, I stopped drinking entirely.

Some people choose sobriety after an incident in which they hit bottom. That wasn’t my pathway, though I do clearly remember the events that helped me decide to make a change. My girlfriend – now wife – Amy Price moved in with me five years ago. She’s had alcoholics in her life for many years, and I knew that my drinking was a concern for her, though she never pressured me to change my behavior. Knowing that she would be watching, I cut my drinking sharply. After a few months of living together, Amy went back to Houston to see friends over a long weekend, and I immediately took the opportunity to get drunk.

I woke up the next morning, hung over, and wondered why the hell I’d gotten drunk the night before. Clearly, I missed the experience of getting smashed. Clearly I’d been waiting for the opportunity to get drunk as soon as I possibly could. What the fuck was THAT about?

I took some aspirin, drank an iced coffee, and dumped out all the cheap booze in the house. (I gave the good stuff to friends. I had some NICE whisky at that point in my life.) Since then, I’ve had the occasional sip of Amy’s drink, but haven’t ordered a drink, got drunk or otherwise violated the drinking rules I’ve set for myself. (Turns out, people get sober different ways. I drink NA beer and spirits, which have less than 0.5% alcohol – there are folks in the AA community, for example, for whom that would violate rules. I know a number of friends who are “California sober”, which means they use cannabis but not alcohol. That’s not something I do for fear that I’d replace one habit with another.)

I’m writing about my experience because one of the major barriers I had in taking on my problems with alcohol was realizing that I had a problem with alcohol. I convinced myself that all alcoholics looked like Nick Cage’s character in Leaving Las Vegas, drinking vodka out of the bottle in the shower. I mostly drank at home, so DWI hadn’t been an issue for me. I never lost a job due to drinking, though in retrospect, my drinking had a lot to do with the end of my first marriage. I didn’t drink in the daytime, I was reasonably happy and successful, so clearly I couldn’t have a problem.

I have written before about the idea that high-functioning depression can be harder to diagnose than major depression, and I suspect the same is true for alcoholism. I had the odd experience of trying to convince (only a very few) friends that my problems with alcohol were serious enough that it was wise for me to stop drinking. My sense is that we, as a society, would benefit from a more nuanced understanding of alcoholism. For everyone for whom alcohol has become unmanageable, leading to assaults, arrests, and endangerment of others, there are tens or hundreds of people for whom alcohol is becoming a problem, or making it harder for people to address the other problems they’re facing in life.

Some people report that they’ve lost tons of weight, felt a wave of new energy or experienced other physical or spiritual transformations when they’ve become sober. That didn’t happen for me. Perhaps if you’re the sort of person who can replace a few cocktails with running a few miles, but for me that would require a full brain transplant, not just eliminating alcohol intake. But my five years of sobriety have been some of the happiest of my life. It’s hard to credit that solely to sobriety, because other aspects of life have changed simultaneously: I’m treating my depression, I moved to a university that’s a much healthier environment for me than my previous employer, I’m in a terrific relationship. My guess is that sobriety makes these other changes easier, and is made easier by these changes.

Hoplark Tea. My current beverage of choice.

The main change I’ve experienced from getting sober: I am starting to do a better job of taking responsibility for my own bad behavior. There’s a strong correlation between moments in my life that I’m embarrassed about and alcohol. It’s not hard to build a causal link: I drink and I do things I shouldn’t do. But that’s a dodge. Alcohol exacerbated my worst tendencies: it didn’t create them. Now when I fail to live up to my values and treat people around me badly, I don’t have an easy explanation for my bad behavior, which brings me one step closer to dealing with the ways in which I fall short.

The hardest thing about not drinking wasn’t the actual process of stopping. I am very lucky that I’ve always been able to cease drinking – my problem has always been with drinking in moderation, and I no longer try to do that. My problems now are mostly problems of replacement behaviors. I’ve had to figure out how to turn off at the end of the day. I used to have a drink or two over dinner – the alcohol was the cue that I was no longer expecting my brain to do productive work. That’s useful, because my brain isn’t well suited to working hard fourteen or sixteen hours a day. I’ve been working on other rituals and passtimes that help me turn off, but it’s a work in progress.

I’ve also had to search for alternative ways to reward myself – a drink was the preferred reward for finishing a project, for doing the task I’d put off doing, for getting through the day. It turns out that I still need rewards for accomplishing the mundanities of life. During the pandemic, I started driving an hour to Albany to get interesting and exciting takeout food most Friday nights, a way of breaking the monotony of COVID sameness. It’s become one in an arsenal of rewards that I keep handy.

That arsenal also includes lots of tasty things to drink that aren’t alcoholic. It’s a terrific time to get sober: breweries are cracking the riddle of making non-alcoholic beer that doesn’t make you sad. Most notable for me has been non-alcoholic Guinness, which I am betting would do well in a taste-test with the fully leaded stuff. I get a monthly subscription from Hoplark, which makes hop-inflused teas and waters, and a bottle of Kentucky 75, which mixed with diet Pepsi is a surprisingly good facsimile of my tipple of choice.

One of the most useful resources for me has been a Facebook group for non-alcohol beer fans, a community that’s been an equal mix of tasting recommendations and low-key encouragement. Seeing people celebrate their sobriety milestones is encouraging, as is watching people forgive and encourage each other. Someone will post about ordering a NA beer and being served the hard stuff, and “ruining” their streak of sobriety – the community will immediately explain that sobriety is, at least in part, about intentionality. The drinker who meant to order a NA beer, who stopped when she figured out the beer was leaded is still sober… and anyone who would quibble over that reading of the situation probably wouldn’t be especially comfortable in this community.

Why write about five years of sobriety? In truth, being sober doesn’t require much concentration or effort most days. I make a point of checking for NA options whenever I am in a bar or restaurant, if only to let restaurant owners know that non-drinkers exist. There’s alcohol in my house for Amy, who might have a glass of wine once a week, or for guests. I have very occasional moments where I BADLY want a drink – the most recent was on an airplane, sitting next to a man who put away four shots of bourbon in rapid succession. I drained my club soda, put on my mask and tried hard not to smell the alcohol as it seeped out of his pores. (Since getting sober, I smell alcohol on people’s skin with an acuity that can be uncomfortable.)

My path to sobriety didn’t run through AA or other conventional support groups, though I have friends for whom those communities, meetings and support are essential to their own path. But I saw an AA five year coin posted to my Facebook NA beer club recently, and I wanted one. Not an AA coin necessarily, but some tangible, physical acknowledgement of five years of being in the world in a different way. I am deeply proud that I’ve found a different way of being, a way that gives me a better chance of being the person I want to be.

This post is my five year coin. It’s my celebration of something that gets easier every day, but is still not easy, and may never be. It’s a strange thing to be proud of, an accomplishment made up of 1800 days of not doing something. But it’s something I am damned proud of, that I’m turning over in my fingers like a heavy coin in my pocket, that I fidget with contentedly, like my wedding ring.

I wish you the best with whatever changes you are trying to make in your life, and I wish you pride in your successes, whatever they may be. And I am looking forward to updating this post five, ten and fifteen years from now.

The post Five years sober. appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

September 30, 2022

Governance, not Moderation: remarks at the Trust and Safety Research Conference

I spoke this afternoon at the Trust and Safety Research conference at Stanford University. This is a new talk for me, and as is my habit, I wrote it out to make sure it held together. So this is what I meant to say, which may or may not resemble what I actually said on stage.

I want to share with you a story of the very early days of the trust and safety profession. In 1994, I dropped out of graduate school to work with one of the web’s first user generated content companies.

We were called Tripod, we were based in Williamstown MA, and for a little while in the late 1990s, we were the #8 website in the world in terms of traffic. Our main competitor was a better known site called Geocities – they ranked #3 – and both of our companies allowed users to do something very simple: using a web form, you could build a personal homepage without having to learn how to code and upload HTML.

Tripod got into this business literally by accident. We thought we were building a lifestyle magazine for recent college graduates, subsidized by the mutual fund companies who wanted to recruit young customers. Late one night, one of my programmers modified a tool we’d created to let you write and post a resume online and turned it into a simple homepage builder. We added it to the collection of web tools we hosted online and forgot about it, until I got a call from my internet service provider, telling me that our monthly bandwidth charges had increased tenfold. No one was interested in our thoughtfully snarky articles about life as a GenX 20-something – what they were interested in was what they had to say. We became a user-generated content business before the term actually existed, and that meant we had to build a trust and safety department.

Those terms didn’t exist either. When we started hosting webpages, it was before any significant legislation or legal decisions about platform moderation, which meant that when one of our users decided to upload copies of Photoshop and the Software Publishers Association came after us, it wasn’t at all clear whether we were criminally responsible for copyright infringement. We began hiring customer service representatives, building tools to let them rapidly review user pages and delete users who violated our terms of service with a keystroke. I wrote the terms of service, by the way – it probably would have made sense to hire a lawyer but hey, it was 1996. I was 23. Lawyers were expensive, and a little intimidating.

Over time, we ended up with a subset of customer service reps – the abuse team – who specialized in making hard calls about whether content should stay or go… or whether it should be escalated, including to law enforcement. You will be unsurprised to learn that child sexual abuse imagery was a problem for us as early as 1995.

The first time we reported CSAM (child sexual abuse material) to our local FBI office in Boston, it sparked an investigation into whether we’d violated federal law by sending imagery to the FBI over the internet. As a workaround we ended up copying evidence of CSAM to stacks of floppy disks and driving them three hours to the FBI field office every few weeks.

I tell you these stories not to make the point that I am old: my students at UMass make that point to me regularly. It’s more to give you an insight into how some of these questions we wrestle with today came to be. If what’s happening in online spaces is harming individuals, or society as a whole, how should we deal with it? What I want to impress upon you is simply how adhoc, how built on the fly many of the infrastructures of the participatory web were… and are.

Not just at Tripod, but across the early internet, we took the path of least resistance, building systems that worked well enough, which became embedded into norms, code and policy over time until they simply became the way things were done. We chose to handle content that violated our terms of service using a customer service model because it seemed like the easiest model to emulate.

What’s strange, in retrospect, is that lots of the people who built Tripod grew up on the academic internet, where things worked very differently. I and many of my colleagues were veterans of MOOs and MUDs, basically text-based, online, multiplayer virtual worlds, where violations of the community’s rules and norms could turn into complex community discussions and debates. One of those debates was immortalized by author Julian Dibbel in a piece called “A Rape in Cyberspace” about sexual harassment on a platform called LambdaMOO. The administrator who ultimately banned the abusive user, after robust community debate, had the terminal next to mine at the Williams College computer lab. We came from a tradition on which users of computer systems were treated as responsible adults (even if we weren’t), who should be responsible for governance of our own online spaces. But when it came to building the consumer web, it’s like we forgot our own past, our own best instincts for how online spaces should work.

I have many regrets about my work building a company that helped pave the way for Friendster, MySpace and ultimately Facebook and Twitter. I’ve spoken before about my regrets about creating the pop-up ad, and if you find me after this talk, I will tell you the story of how our tools to keep pornography off Tripod cost our investors at least a billion dollars.

But my biggest regret is that we unquestioningly adopted a model in which we provided a free service to users, monetized their attention with ads and moderated content as efficiently and cheaply as possible. We didn’t treat our users as customers: had they paid for their services, we probably wouldn’t have been as quick with the delete key. And we certainly didn’t treat our users as citizens.

Here’s why this matters: since the mid-1990s, the internet has become the world’s digital public sphere. It is the space in which we learn what’s going on in the world, where we discuss and debate how we think the world should work, and, increasingly, where we take actions to try and change the world. There is no democracy without a public sphere – without a way to form public opinion, there’s no ways to hold elected officials responsible, and no way to make meaningful choices about who should lead us. This is why Thomas Jefferson in 1787 told a friend that he would prefer a republic with newspapers and no government over a government without newspapers.

There is a litany of woes about our contemporary public sphere. The market-based system that produced high quality journalism for the twentieth century may be fatally crippled by a shift of advertising revenue from print to the internet. We have legitimate worries that social media spaces may be harming individuals, undermining people’s body image and self esteem, pushing vulnerable people towards extremist ideologies. We worry that the internet is increasing political polarization, locking us into ideological echo chambers, misleading us with mis- and disinformation.

How valid are these concerns? It’s complicated, and not just because social science is complicated, but because it’s incredibly difficult for independent researchers to study what’s happening on social media platforms. We know significantly more about some platforms than others – Twitter became the Drosophila of social media scholarship by making communications public by default and giving academics access to APIs useful for scholarship – but a study colleagues and I conducted in 2020 and 2021 of social media scholars found that none of us believed we had access to the data we would need to answer key questions about social media’s effects on individuals and society. This included researchers who were designing academic/industry collaborations like Social Science One.

This is why I’ve joined scholars like Renee Di Resta, Brendan Nyhan and Laura Edelson in calling on platforms to release vastly more data about moderation decisions, about how they redirect traffic across the internet, about the effectiveness of techniques used to reduce information disorder. It’s why I’ve worked with activists like Brandon Silverman – the founder of Crowdtangle – on legislation like the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, designed to ensure that information about what information and misinformation is spreading on platforms like Facebook can be reviewed in real-time by scholars and policymakers alike. But I am increasingly convinced that we cannot just work to make existing social networks better – we need to reconsider the roles of social networks in our public sphere, and build networks that actively help us become better neighbors and better citizens.

My dear friend Rebecca MacKinnon published a wonderful analysis of tech platforms about a decade ago, titled Consent of the Networked. She argued that platforms like Facebook behaved as if they were monarchs and their users were subjects. At best, we might hope for a more benevolent monarch, one that would recognize that their subjects had basic rights, as England had done with the Magna Carta.

An interesting thing happens when you treat people like subjects: they don’t gain experience in being citizens. Two decades ago, Robert Putnam published Bowling Alone, his influential argument that Americans were losing connective social capital as we abandoned real world interactions in spaces like bowling leagues. Worried about the implications of Putnam’s work, Scott Heifferman started Meetup to try and build real-world social ties between people who met up online.

It turns out that social media may have counterbalanced some of the worries Putnam had about losing weak ties. Tools like Twitter and Facebook are actually amazing at helping us maintain lightweight connections to people we might otherwise have lost. But there’s another prediction that Putnam offered that’s got important implications. Participation in public life, even in serving as treasurer of your bowling league, trains us in the practical skills of making a democracy function. Whether at the PTA or the Elks Lodge, civic participation trains us how to run a meeting, how to take turns and make sure the voices in a room are heard, and critically, how to have a constructive disagreement.

What happens when we move from the physical spaces that we – as citizens – are collectively responsible for moderating into digital spaces moderated by people half a world away? What happens when decisions about what is allowable speech are made by people half a world away, guided by the judgments of opaque algorithms, following rules written in three ring binders? Our public sphere is no longer helping us become citizens – it’s training us to be subjects, and specifically the subjects of large internet companies.

There is a different way to moderate online spaces. The first step is to get rid of the word “moderation” and take seriously what we’re actually doing, and that is “governance”. In most online spaces, governance comes from a powerful and distant authority, whose decisions we have no power to challenge. It’s a form of serfdom, inasmuch as the lords provide the digital land and take a share of our crops – attention – in exchange for our continued right to exist.