Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 25

May 19, 2013

Crowdfunding Checkbook Journalism: Gawker’s “Crackstarter” and its implications

Toronto mayor Rob Ford is a controversial character. 2300 words in his 7600 word Wikipedia biography make up a section titled “other controversies“. These controversies include being drunk and picking a fight at a Leafs game, insulting people with AIDS, people of Asian descent, and allegedly groping a female mayoral candidate.

But all that colorful behavior pales in comparison to the accusations he’s now facing. The Toronto Star, a left-leaning newspaper that’s repeatedly reported on mayor malfeasance, reports that they’ve watched a video that shows mayor Ford smoking crack cocaine with Somali drug dealers. Star reporters Robyn Doolittle and Kevin Donovan were approached by a community organizer from Toronto’s Somali community, who was acting as a “broker” for the person who shot the video on a smartphone, a man who alleges that he has sold crack to the mayor previously.

For Americans, the Ford story calls up fond memories of Marion Barry, the Washington DC mayor who was videotaped freebasing cocaine by the FBI and the DC police. (Good news for mayor Ford – after serving a prison term, Barry returned to DC politics under the campaign slogan “He May Not Be Perfect, But He’s Perfect for D.C.”, and retook the mayorship four years after his arrest.) But, if anything, the Rob Ford story is crazier and more complex than the Barry scandal, at least from a journalistic perspective.

While Doolittle and Donovan of the Star have seen video, but when they were asked to pay a six figure sum for the recording, they refused. Their article states unambiguously: “The Star did not pay money and did not obtain a copy of the video.”

That’s not surprising. Paying sources for stories is a controversial practice. In the English-language press, it’s often called “checkbook journalism“, and it’s frowned on in elite US media (though it’s certainly happened through history), though quite common in tabloid media. In the UK, it’s significantly more common, and underpins much of the scandal around the behavior of Rupert Murdoch’s newspapers in the UK. US journalist Jack Schafer argues that there are practical, as well as ethical, reasons to avoid paying sources – you’ll cultivate sources who want to sell you bad information as well as good information.

Nick Denton and the freewheeling opportunists at Gawker Media don’t spend much time worrying about these niceties. Gawker’s tech site Gizmodo paid $5000 for a prototype of a next-generation iPhone, which made some headlines as the site may have paid money for stolen goods. But the attention didn’t damage Gawker, and they are now raising a set of new questions in offering to pay $200,000 for the Rob Ford video.

What’s interesting this time is how Gawker plans to pay for it.

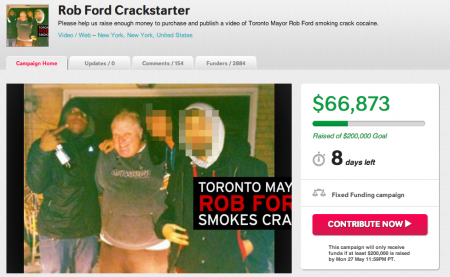

Gawker editor John Cook published an article on Friday titled “We Are Raising $200,000 to Buy and Publish the Rob Ford Crack Tape”. Cook calls the campaign a “crackstarter”, a pun on Kickstarter, but the project is raising money on Indiegogo, perhaps because Kickstarter reviews proposals and rejects many of them, while Indiegogo maintains a more open platform.

The text associated with Gawker’s ask suggests that they might have, in passing, considered that there are some ethical issues involved with paying drug dealers $200,000 for a video recording. Gawker’s sophisticated and nuanced ethical explanations include this thoughtful passage:

Christ, That’s a Lot of Money.

Yes, it is. But they’ve got the video! And it’s not all about greed, though of course most of it is. The owners of this video fear for their safety, and want enough money to pay for a chance to get out of Toronto and set up in a new town. Their fear is not entirely unwarranted. Rob Ford is a powerful if buffoonish man, and he was wrapped up in a drug scene that purportedly involved many other prominent Toronto figures.

Rather than respond to this analysis, I’ll point you to Rosalind Robinson, who notes that the $200,000 Gawker proposes to pay drug dealers, is money that could go towards healing the city of Toronto, not harming it more. In a piece titled “Fuck You, Gawker“, she observes:

Gawker wants to write these criminals a cheque for more money than most of us can imagine having access to in our lifetime. And not a cheque of their money – of *yours*.

All you who bitch about taxes, who need public health care, who are on a waitlist to see a doctor, who work day in and day out, who work hard in crap jobs that don’t pay well – you, joe citizen, who have never broken a law in your life – they’re asking YOU to give this huge amount of money to a group of people who are a violent plague on my city, who risk the lives of both addicts and innocent bystanders on a regular basis.

Thus far, Gawker’s campaign has raised roughly a third of its goal, almost $67,000 at last check. With eight days to go, it’s possible that Gawker will raise the money to purchase the video. Whether they publish the video, or get robbed at gunpoint by their business partners, they’ll surely get a good story out of the experience.

Does raising money to purchase incriminating video represent a new milestone in crowdfunding? Is it a particularly ethically cloudy example of civic crowdfunding? Or just an attention grabbing stunt by Denton and crew?

Writing in Forbes, Maureen Henderson sees this as the latest example of the rich and powerful using crowdfunding to fund projects they could fund through other means. Much as Warner Bros. could have funded a new Veronica Mars movie without $5.7m raised online, Gawker could probably negotiate a deal with their sources to purchase the video at a price they could cover from online ad revenue, as nothing sells like a political train wreck.

What does the Crackstarter mean for online journalism and crowdfunding? When I began working at the Berkman Center ten years ago, John Palfrey offered a helpful rule of thumb for understanding how law worked in cyberspace: “If it’s illegal offline, it’s illegal online.” I’d suggest that the same applies in the realm of ethics: paying a source for a story is ethically suspect both offline and online.

But there’s a dimension to crowdfunding payments to a source that complicates matters. Not only has Gawker’s editorial board made the decision that it’s ethically permissible to pay for the Rob Ford video – so have 2,896 donors, who’ve given their own money to see the mayor inhale. It’s a reasonable guess that few are Rob Ford supporters. This crowdfunding campaign lets Ford opponents vote with their pocketbooks to increase the chances Ford will be forced to resign.

I predict Ford will resign before Gawker purchases and runs the video. But the implications of the campaign are still worth considering. When asked about the ethics of paying drug dealers for the video, Gawker can point to thousands of supporters who didn’t have ethical qualms about paying for the footage. And much as civic crowdfunding raises questions about whether only rich neighborhoods will fund new parks and civic infrastructure, crowdfunding to pay for videos is a trend that seems likely to favor high-visibility politicians with wealthy opponents over lower-attention scandals. Had the city of Bell, California needed to crowdfund evidence to indict city manager Robert Rizzo, it’s unlikely the poor, majority-Spanish speaking community would have ousted corrupt leaders.

More than one online commenter has asked whether Gawker will share revenue from pageviews with their donors if they are able to purchase the Ford video. I’m more curious whether the donors will share the credit and the blame if crowdfunding checkbook journalism becomes the next big thing.

May 8, 2013

Big stories and little details: what Charles Mann misses

Charles Mann offers a big story in the latest issue of the Atlantic. It’s 11,000 words, and it’s based around an audacious premise: the end of energy scarcity. The peg for the story is Japan’s ongoing research on methane hydrate, an amalgam of natural gas trapped in water ice that occurs in oceans around the world. If methane hydrate can be harvested, Mann tell us, the global supply of hydrocarbon fuels are virtually unlimited. This, he argues, would have massive geopolitical and strategic implications, as the history of the twentieth century can be read in part through the lens of wealthy nations without oil seeking the black stuff in less developed lands. New forms of power might center on who can extract ice that burns like natural gas.

The bulk of the Mann piece is a debate over “peak oil”, an idea put forward by M. King Hubbert in the 1950s, when he correctly predicted that US oil production would slow. Mann’s piece pits Hubbert against Vincent E. McKelvey, his boss at the US Geological Survey for years, who argued that energy supplies are virtually inexhaustible, though the costs to extract them increase as we use up the “easy” oil ready to burst above the surface. While Hubbert’s predictions about US oil production were initially right, Mann argues, the rise of techniques like horizontal drilling and hydrofracking means McKelvey is right in the long run. If we need methane hydrate – and Japan does, as it lacks other hydrocarbon resources – we’ll find a way to pay for it. The argument only looks like a contradiction, Mann argues, because it’s an argument between geologists on one side and social scientists on the other, and from the social scientists’ point of view, so long as there’s economic demands for hydrocarbons and the means to extract it, we should expect these fuels to keep flowing.

There’s something very attractive about Mann’s argument. He writes as an insider who’s going to let you in on what the smart guys know that poor, dumb saps like me would never imagine. It’s a tone you hear a lot in Washington policy circles, a realpolitik view of the world that suggests you can entertain yourself with solar panels as long as you’d like, but the adults in the room are deciding who gets invaded for their petrochemical wealth and whose civilizations will collapse into a new Medieval period.

Fortunately, there are some smart responses to Mann’s article, some vitriolic, some patient and thoughtful. (To the Atlantic’s credit, they published both Mann’s piece and Chris Nelder’s excellent response.) The essence of the responses is this: yes, there’s a whole lot of methane trapped in ice. Yes, if we could extract it, we’d have a whole lot of fuel that burns with half the carbon emissions of coal. But it’s unclear we can ever extract this at an affordable cost. (Canada just dropped out of the methane hydrate race, perhaps because they see extracting oil from tar sands as a more plausible source of hydrocarbons.)

And even if we can, then what? Methane burns cleaner than coal, but we’d be still emitting massive amounts of CO2 in a methane-based economy.

Mann’s not wholly unaware of the environmental implications of methane hydrate for global CO2 levels, but he frames his argument simply: natural gas may be bad, but coal’s worse. He acknowledges that we’ll need to move to renewables, but worries that we won’t be able to store power during periods of low solar or wind intensity. (These are real problems, but ones where a great deal of innovation are taking place, from high tech solutions like power-storing flywheels to effective low-tech solutions like pumped storage.)

In his cursory consideration of how a near-infinite supply of methane might have negative environmental implications, Mann dedicates 2 paragraphs of his love-song to natural gas to a minor problem: methane is a potent greenhouse gas. When a gas well leaks more than 3%, it’s worse from a climate change perspective than burning coal. And it’s not just the wells – America has a long system of pipelines that carry natural gas, and no one is sure just how leaky those pipes are.

Mann assures us that repairing the holes in natural gas pipelines (3,356 in Boston’s pipelines alone!), is “a task that developed nations can accomplish”. It’s not as hard as changing the laws of economics, Mann asserts, which ensure that cheap natural gas will help America recover its geopolitical might.

So let’s talk for a moment about those laws of economics. If you’re a natural gas pipeline operator, losing 3% of your supplies in transit is a rounding error, so long as the gas dissipates and doesn’t present an explosion risk. My friend at the Department of Energy who made me aware of natural gas leakage noted that current requirements for pipeline inspection largely involve flying over vast lengths of cast-iron pipe and looking for browning of vegetation from leaking gas, a method that would be humorously inexact if the environmental consequences weren’t so serious.

The laws of economics Mann is so focused on won’t force pipeline operators to replace their leaky infrastructure. Markets don’t do a very good job of correcting for “externalities” like climate impact, unless governments force them to. The modest success of cap and trade in the northeastern US under the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative required nine states to spend political capital and impose new requirements on industry, requirements that were politically unpopular, especially with Republican governors, like Mitt Romney who pulled Massachusetts out of the compact. (Deval Patrick pulled us back in, thankfully.)

The ultimate point of Mann’s essay, I think, is that environmentalists have hoped that peak oil and the threat of losing our energy supplies would push developed economies to embrace zero-emissions power. That’s not going to happen, Mann argues – so long as we’re willing to pay for it, hydrocarbon energies are inexhaustible for the foreseeable future. What Mann doesn’t say is this: if we are worried about climate change, the market won’t solve things for us – we need governments to help us.

That’s a deeply unsexy position to hold these days. Authors like Mann are fascinated by ways in which new technologies can save us from ourselves, discovering energy sources where none existed before, and developing even more profound technological solutions to handle the waste, like sequestering CO2 deep into the ocean, where it becomes trapped in water ice much as methane is trapped in methane hydrate. The problem is that these technologies cost billions to develop, and there are always cheaper alternatives that have externalities not calculated in market equations. The market for CO2 sequestration exists only if meaningful, widespread controls on greenhouse gas emissions come into play and create “artificial” incentives to invest in these technologies.

My friend Ivan Krastev has a smart essay – a short TED ebook – called “In Mistrust We Trust: Can Democracy Survive When We Don’t Trust Our Leaders?” Of the several problems he identifies with contemporary democracies, one of the most challenging is this: “Economic decision-making is methodically being taken out of democratic politics as the spectrum of acceptable policy choices has been dramatically narrowed. Politics has been reduced to the art of adjusting to the imperatives of the market.”

Krastev is largely focused on the ways European economies are wrestling with austerity, trying to provide social services to their populations but facing market pressures to be globally competitive. Voters become systematically disenfranchised because their popular will is held in check by what markets “want”.

We face similar disenfranchisement in the US. A large majority of Americans see climate change as a serious problem. But carbon taxes remain largely off the table in the US, due to fears of reducing American competitiveness in a global market.

Mann and the Atlantic missed a great opportunity here to celebrate what’s actually working: a slow conversion towards solar and wind in parts of the world where cap and trade and other emissions controls have been put into place. It’s not as sexy as burning ice, but it’s a future far more livable than the one Mann posits.

April 29, 2013

Cute Cats to the Rescue? Participatory Media and Political Expression

Some years back, I gave a talk at O’Reilly’s ETech conference that urged the audience to spend less time thinking up clever ways dissidents could blog secretly from inside repressive regimes and more time thinking about the importance of ordinary participatory media tools, like blogs, Facebook and YouTube, for activism. I argued that the tools we use for sharing cute pictures of cats are often more effective for activism than those custom-designed to be used by activists.

Others have been kind enough to share the talk, referring to “the Cute Cat theory”. An Xiao Mina, in particular, has extended the idea to explain the importance of viral, humorous political content on the Chinese internet.

I’ve meant to write up a proper academic article on the ideas I expressed at ETech for years now, and finally got the chance as part of a project organized by Danielle Allen and Jennifer Light at the Institute for Advanced Studies. They invited a terrific crew of scholars to collaborate on a book titled “Youth, New Media and Political Participation”, now in review for publication by MIT Press. The volume is excellent – several of my students at MIT have used Tommie Shelby’s “Impure Dissent: Hip Hop & the Political Ethics of Marginalized Black Urban Youth“, which will appear in the volume, as a key source in their work on online dissent and protest.

I’m posting a pre-press version of my chapter both so there’s an open access version available online and because a few friends have asked me to expand on comments I made on social media and the “Arab Spring” at the University of British Columbia and in Foreign Policy. (I also thought it would be a nice tie-in to the Gawkerization of Foreign Policy, with their posting today of 14 Hairless Cats that look like Vladimir Putin.)

So – Cute Cats to the Rescue? Participatory Media and Political Expression.

Abstract: Participatory media technologies like weblogs and Facebook provide a new space for political discourse, which leads some governments to seek controls over online speech. Activists who use the Internet for dissenting speech may reach larger audiences by publishing on widely-used consumer platforms than on their own standalone webservers, because they may provoke government countermeasures that call attention to their cause. While commercial participatory media platforms are often resilient in the face of government censorship, the constraints of participatory media are shaping online political discourse, suggesting that limits to activist speech may come from corporate terms of service as much as from government censorship.

Look for the Allen and Light book on MIT Press next Spring – it’s an awesome volume and one I’m proud to be part of.

Bad reviews, better reviews

Cultural critic David Rieff uses my new book, Rewire: Digital Cosmpolitans in the Age of Connection, as a jumping off point for a screed against “techno-utopians” – and, near as I can tell, the very idea of progress – in the latest issue of Foreign Policy. I’m a little surprised that Rieff has grouped me with thinkers like Ray Kurzweil, as I’m far more skeptical of technological potential than he. Then again, it would be very hard to recognize my positions from Rieff’s portrayal of my book.

It’s a bit frustrating that Foreign Policy is releasing this essay (they’ve made it clear that it’s not a book review) six weeks before my book is in print. Unfortunately, you can’t yet read my book and see the wide gap between what I actually say and Rieff’s portrayal of my positions. FP gave me a very brief window to respond to Rieff, and that response runs in their current issue.

If you’d like a better introduction to my work than Rieff offers, Publishers Weekly was kind enough to review my book here. I’m looking forward to other reviews and reactions in the coming weeks.

April 26, 2013

What comes after election monitoring? Citizen monitoring of infrastructure.

I spent last week in Senegal at a board meeting for Open Society Foundation, meeting organizations the foundation supports around the continent. Two projects in particular stuck in my mind. One is Y’en a Marre (“Fed Up”), a Senegalese activist organization led by hiphop artists and journalists, who worked to register voters and oust long-time president Abdoulaye Wade. (I wrote about them last week here, and on Wikipedia.)

Documentary on OSIWA’s Situation Room project in Senegal, featuring Y’en a Marre

The other is a project run by Open Society Foundation West Africa – OSIWA – with support from partners in Senegal, Liberia, Nigeria and the UK. It’s an election “situation room”, a civil society election monitoring effort that focuses less on declaring elections “free and fair” than on reacting quickly to possible violence, mobilizing community leaders as peacemakers. OSIWA’s method has been used in Nigeria and Liberia, as well as in the Senegalese election where Y’en A Marre was such a powerful actor, as portrayed in the documentary above.

Elections are a moment where civil society often shines. Holding elections has become a major priority for governments, bilateral aid organizations and civil society organizations, and there’s been a good deal of creativity around monitoring elections using parallel vote tabulation and social media monitoring.

But elections don’t always equal development, or even a democratic process. Economist Paul Collier notes that elections in very poor nations often spark violence, and sees evidence that 41% of elections are marred by significant fraud. Elections work, Collier tells us, when governments are evaluated on their performance, not on their propensity for patronage. Citizens need to watch whether governments keep their promises, and oust those that don’t measure up. (See MorsiMeter, developed to monitor the first 100 days of Morsi’s presidency of Egypt.)

One question colleagues and I had for the remarkable activists at Y’en A Marre was what they were planning to do now that Wade had been ousted and Macky Sall elected. The bloggers and journalists I spoke to had a number of answers that centered on ensuring the Sall government benefits the rural poor and helping Senegal reduce dependence on international food suppliers. While it’s great to see activists thinking about macroeconomics, it was also clear that the intense focus of the movement – ousting a president who’d overstayed his constitutional mandate – had significantly dissipated, and that new foci hadn’t generated the same energy amongst the hundreds of community leaders who make up the Y’en A Marre movement.

I was thinking about this question – what do election-focused movement do once an election is over? – when I stumbled on this paper from colleagues and friends at Columbia’s Earth Institute. The Columbia team document a system they’ve built for government-hired enumerators in Nigeria, who are using mobile phones equipped with cameras and GPS to conduct a census of the nation’s essential infrastructure: boreholes (wells), schools, health clinics, etc. The teams rapidly mapped over a quarter million points of data, one of the larger extant sets of information on the Nigerian government’s efforts at service delivery.

As the Columbia authors explain, mapping using mobile phones is less a clever gimmick than a technical necessity – make a map with paper surveys and you’re transferring long GPS coordinates by hand. A simple application that stores a GPS reading, a picture and a human report allows for a large set of “human sensors” to rapidly build a data set.

People involved with the Columbia project have worked on version of this idea that are more expressive – Matt Berg (who took over some of the Geekcorps work I’d helped start in Mali) worked with a nonprofit in Kolkata to help children map trash and public health issues in their neighborhoods, overlaying data on maps they’d drawn by hand of their home communities. And other projects have focused on helping communities map their infrastructures and needs through a combination of digital and analog means, notably Map Kibera, which has worked to create accurate maps of one of Nairobi’s largest slums.

It strikes me that a major opportunity for groups like Y’en A Marre to remain active between elections is to take on a role as citizen monitors. If the key to a successful democracy is a government that delivers services and is elected based on its performance, then documenting whether campaign promises get met is a critical step towards responsive government. In most African nations where I’ve worked, campaign promises center primarily on building infrastructures: “Name me to Parliament and I will ensure we’ll have 20 new primary schools and clean water in every village.” Citizens need to be able to verify those claims. Even in developed nations, those are hard claims to verify – ProPublica memorably turned to crowdsourcing to determine whether US federal stimulus money was being put to work, or sitting in local government coffers. (Most of it was put to work quite quickly.) If it’s hard to understand the local impacts of federal spending in the US, it’s really hard in nations that have a weak press, a culture of government secrecy or little ability to collect on the ground data.

I’d like to find ways to help groups like Y’en A Marre, Enough is Enoughhttp://eienigeria.org/ and others collect and share data, creating open data sets useful to activists, journalists, governments and the development community. The same data could help governments document their successes, journalists monitor government spending and activists demand equitable resource distribution in their communities. I can imagine projects that incorporate low-cost CO sensors that talk to phone to monitor vehicular and cooking stove pollution; projects that invite people to document their favorite and least favorite parts of their cities and villages; projects that enlist broad cooperation by compensating participants for their time with mobile phone minutes, as Esoko does to collect agricultural market information. Other monitoring projects could focus on rapid response. My friend Tunde Ladner of Wangonet began a project in Lagos that encouraged people to report dangerous construction underway, a critical dataset that would demand quick response to protect against building collapse.

I’m thinking about putting some of Center for Civic Media’s resources towards exploring this idea, probably first in Nairobi with friends at Ushahidi and the iHub. If you have ideas about partners, about questions to explore, pushback on the concept of citizen monitoring, I’d love to hear from you in the comments.

Mourning those you never met: Scott Miller

Last week was a stressful, dreadful one, not just for people in Boston who lost friends in the marathon bombing and a colleague when Officer Sean Collier was shot and killed. It was a dreadful week in Iraq, a week that featured a massacre in Syria and an industrial explosion in West, Texas that killed at least 15 and raises difficult questions about the poor state of industrial regulation in the US.

During that miserable week, I got a piece of sad news: the untimely death of a man I’ve long admired, Scott Miller. As more than one music critic has pointed out in their elegies for him, Scott Miller is the best songwriter you’ve never heard of. He led a band in the 1980s called Game Theory which produced four hooky, catchy and deeply strange power-pop/new wave albums, then formed Loud Family, which released seven albums between 1992 and 2006. The Loud Family albums cover an amazing stylistic range, from cheery pop songs to unpredictable sonic experiments, sometimes within the same track.

“Don’t Respond, She Can Tell”, by Loud Family

Miller often answered questions about his obscurity, noting that he’d never set out to make music that would be appreciated by critics and a small army of obsessed fans, and ignored by the wider world. I was deeply struck by a comment he made some years back, answering a fan’s inquiry: “I’m utterly serious about music, I just respect the buying public’s judgment that it’s not what I should do for a living.” One of the many hopes of an age of digital distribution was that artists who produce work adored by a small artist, instead of appreciated by a large one, will be able to make a living. Miller walked this narrow path well before the tools and support systems smoothed the way.

The first Game Theory albums got some college radio play, but by the end of that band, Miller had given up on the prospect of following arty-yet-accessible artists like REM into the mainstream, and stopped editing himself. The result was Lolita Nationhttp://www.allmusic.com/album/lolita-..., an unbelievably strange and wonderful albumhttp://www.lostturntable.com/?p=1343 that also became legendarily unobtainable. (Amazon will sell you one of the few CD copies extant for about $100, but Scott’s friends are posting links to digital copies of the albums on the Loud Family site. You really should download these, particularly Real Nighttime – perhaps the most accessible – and Lolita Nation – the masterpiece.)

Loud Family took off where Lolita Nation left off, juxtaposing pop songwriting with sonic collage, remixing his back catalog into new songs, snippet by snippet. The six Loud Family albums, especially Days for Days and Interbabe Concern, are near the top of my most played list over the last decade, and often find myself caught between wondering why everyone isn’t as in love with this music as I am, and wondering how Miller persuaded a record label to ever bother releasing it, as it was clear his music was very much an acquired taste.

Not everyone who deserves an audience finds one. Miller turned to music criticism (appreciation, really) in recent years, and his book “Music: What Happened?” introduced me to other bands who’ve become favorites, like Thin White Rope, whose remarkable lead singer, Guy Kyser, now studies invasive plants at UC Davis. Kyser and Miller are two in a very special class of artists – visible enough that you might discover them and have their work change your life without knowing them personally, but invisible enough that they need day jobs. Finding an artist like this is a special gift, a treasure you share with friends you trust enough to believe they might “get it”, a secret handshake, not a badge.

Miller, like most professional musicians, didn’t make much money, and his friends have set up a scholarship fund for his two daughters, open to contributions from his fans. The Onion’s A/V Club has a particularly good remembrance of Scott Miller, including three music videos. Rest in peace, Scott, and thanks for the music.

April 16, 2013

Bloggers in Bangladesh facing arrest, assault, murder

This is a hard day to write about issues other than sudden, unexpected disasters – the bombing in Boston, the earthquake in Iran – and horrific ongoing disasters of continuing violence in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. But I’ve been trying to get my head around a complicated situation in Bangladesh that’s become very dangerous for bloggers and activists in that country: the aftermath of the Shahbagh protests and the arrest of Bangladeshi bloggers for alleged atheism.

Some background: When Bangladesh broke away from Pakistan in 1971, the Pakistani Army violently attempted to prevent “East Pakistan”‘s breakaway, killing anywhere between 300,000 and 3 million Bangladeshis, raping hundreds of thousands of women and targeting intellectual and potential political leaders. In 2009, under a secular government in Bangladesh, the country began an international crimes tribunal, prosecuting local collaborators with the Pakistani Army, who include leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami, the largest Islamist party in the nation.

The court convicted Abdul Quader Molla, assistant secretary general of Jamaat, of war crimes in February 2013 and sentenced him to life in prison. Many Bangladeshis were dissatisfied with this sentence and demanded capital punishment. On February 6, demonstrators began occupying Shahbagh intersection in Dhaka to demand Molla’s execution.

Bloggers and online activists were prominent in urging people to take to the streets, where the protests expanded beyond demands for punishment and into a call to oppose political Islam. Supporters of Molla’s party reacted with counter-demonstrations. CLashes between demonstrators and counter-demonstrators killed at least four and injured over a thousand.

A Bangladeshi blogger, Ahmed Rajib Haider, who wrote under the pen name “Thaba Baba (Captain Claw)” had written about war crimes for years and was active in calling for the Shahbagh protests. The 26 year-old was brutally murdered near his home on February 15th. Bloggers speculate that he was killed by Islamists, as his laptop was left at the scene of the crime, implying he wasn’t a mugging victim.

Arrested bloggers and the tools of their trade. Image by Demotix

As protests continued, Islamists groups argued that the bloggers helping instigate the protests were anti-Islamic, anti-social and atheistic and demanded their arrest and prosecution. The Bangladeshi government responded by founding a committee to track anti-Islamic activity on Facebook and other online media. On April 1st, the police arrested three bloggers for their alleged “derogatory content”.

Global Voices, Reporters Without Borders and others have condemned these arrests, but arrests continue, most recently targeting Asif Mohiuddin, whose blog has been banned, and who was stabbed by Islamists in January, before protests began – his arraignment was scheduled for yesterday. We understand that Bangladeshi bloggers are terrified of arrest or assault, and some have gone into hiding.

The invisibility of this story in international media is making the prosecution of bloggers and activists possible – with international attention, it is possible the Bangladeshi government would be less likely to cooperate with demands to prosecute activists for alleged atheism, which isn’t a crime under Bangladesh’s constitution. If you can help by calling attention to the story, particularly by pitching it to reporters who cover international news, Global Voices would appreciate your help.

April 15, 2013

Y’en a Marre – music and mobilization in Senegal

I’m in Dakar, Senegal this week for a meeting of Open Society Foundation’s Global Board, along with the boards of our four African foundations (East Africa, West Africa, Southern Africa, South Africa). The formal meetings begin today, but for the past two days, we’ve been visiting grantees and projects in Senegal, including an ambitious election-monitoring project called “The Situation Room” and a set of projects underway across the country.

Yesterday, I visited a group called Y’en a Marre, a truly impressive collective of rappers and journalists who have turned their frustration with Senegal’s development and politics into mobilization of the nation’s youth. They claim responsibility for mobilizing 300,000 young voters, a massive number in a country of fewer than 13 million citizens. We heard from three of the group’s founders both about their work to register and turn out young voters, and their efforts to hold the new Senegalese government accountable to their campaign promises.

Kilifeu – Mbess Seck – offers a history of Y’en a Marre in rhyme

After their formal presentation, I got the chance to talk with Thiat, one of the most influential rappers on Senegal’s music scene. (I’d been told by fans of Senegalese hiphop to look for tracks by “Junior”. I asked Thiat and his friends about whether they recorded with this guy, Junior, and one of Thiat’s crew just pointed a finger towards him. “Thiat” means “Junior” in Wolof, and he explained – bluntly, if immodestly – that he would draw at least twice as many youth to a concert as Senegalese stars known in the west like Darra J.) I’d been impressed by Thiat’s passion about social issues, and I learned that his musical impact may be as impressive – Y’en a Marre is planning collaborations with M1 of Dead Prez, Talib Kweli and, possibly, Mos Def. Thiat hopes that Kweli and M1 will be willing to offer verses in Wolof, while Thiat and his crew will offer English verses.

There’s some information on Y’en a Marre’s musical and social impact online in English – a good story in the New York Times, and an excellent, in-depth piece in Africa is a Country. I was happy to see an article on the French-language Wikipedia, but sad that there wasn’t one in English. So I banged one out, and the text I posted last night follows below. Please feel free to fix it up if you have a chance.

“Y’en a Marre” (“Fed Up”) is a group of Senegalese rappers and journalists, created in January 2011, to protest ineffective government and register youth to vote. They are credited with helping to mobilize Senegal’s youth vote and oust incumbent President Abdoulaye Wade, though the group claims no affiliation with Macky Sall, Senegal’s current president, or with any political party.

The group was founded by rappers Fou Malade (“Crazy Sick Guy”, real name: Malal Talla), Thiat (“Junior”, real name: Cheikh Oumar Cyrille Touré), Kilifeu (real name: Mbess Seck. Both Thiat and Kilifeu are from celebrated rap crew “Keur Gui of Kaolack”) and journalists Sheikh Fadel Barro, Aliou Sane and Denise Sow. The movement was originally started in reaction to Dakar’s frequent power cuts, but the group quickly concluded that they were “fed up” with an array of problems in Senegalese society.

Through recordings, rallies and a network of hundreds of regional affiliates, called “the spirit of Y’en a Marre”, the group advocates for youth to embrace a new type of thinking and living termed “The New Type of Senegalese” or NTS. In late 2011, the collective released a compilation titled “Y’en A Marre”, from which the single “Faux! Pas Forcé” emerged as a rallying cry for youth frustrated with President Wade and his son and presumed successor. They followed with a single, “Doggali” (“Let’s finish”), which advocated for cleansing the coutry of Wade and son.

The group and their members campaigned door to door to register young Senegalese to vote and claim that more than 300,000 voters were registered with Y’en a Marre’s assistance and urging. On February 16, 2012, three of the group’s founders were arrested for helping to organize a sit-in at Dakar’s Obelisk Square. Despite arrests, the group continued to organize protests up until the election that unseated Wade.

Despite reaching the goal of ousting Wade, Y’en a Marre remains active, hosting meetings and shows, urging the new government to implement promised reforms, including reforms of land ownership, a key issue for Senegal’s rural poor.

Y’en a Marre is particularly significant in Senegalese politics, because in his 2000 campaign, Abdoulaye Wade prominently featured the support of Senegalese rappers as a way of connecting with young voters. 12 years later, Y’en a Marre demonstrated that Senegal’s youth were not unquestioningly loyal to Wade and were searching for a leader who could credibly promise reform.

April 4, 2013

Schneier and Zittrain on digital security and the power of metaphors

Bruce Schneier is one of the world’s leading cryptographers and theorists of security. Jonathan Zittrain is a celebrated law professor, theorist of digital technology and wonderfully performative lecturer. The two share a stage at Harvard Law School’s Langdell Hall. JZ introduces Bruce as the inventor of the phrase “security theatre”, author of a leading textbook on cryptography and subject of a wonderful internet meme.

The last time the two met on stage, they were arguing different sides of an issue – threats of cyberwar are grossly exaggerated – in an Oxford-style debate. Schneier was baffled that, after the debate, his side lost. He found it hard to believe that more people thought that cyberwar was a real threat than an exaggeration, and realized that there is a definitional problem that makes discussing cyberwar challenging.

Schneier continues, “It used to be, in the real world, you judged the weaponry. If you saw a tank driving at you, you know it was a real war because only a government could buy a tank.” In cyberwar, everyone uses the same tools and tactics – DDoS, exploits. It’s hard to tell if attackers are governments, criminals or individuals. You could call almost anyone to defend you – the police, the government, the lawyers. You never know who you’re fighting against, which makes it extremely hard to know what to defend. “And that’s why I lost”, Schneier explains – if you use a very narrow definition of cyberwar, as Schneier did, cyberwar threats are almost always exaggerated.

Zittrain explains that we’re not debating tonight, but notes that Schneier appears already to be conceding some ground in using the word “weapon” to explore digital security issues. Schneier’s new book is not yet named, but Zittrain suggests it might be called “Be afraid, be very afraid,” as it focuses on asymmetric threats, where reasonably technically savvy people may not be able to defend themselves.

Schneier explains that we, as humans, accept a certain amount of bad action in society. We accept some bad behavior, like crime, in exchange for some flexibility in terms of law enforcement. If we worked for a zero murder rate, we’d have too many false arrests, too much intrusive security – we accept some harm in exchange for some freedom. But Bruce explains that in the digital world, it’s possible for bad actors to do asymmetric amounts of harm – one person can cause a whole lot of damage. As the amount of damage a bad actor can create, our tolerance for bad actors decreases. This, Bruce explains, is the weapon of mass destruction debate – if a terrorist can access a truly deadly bioweapon, perhaps we change our laws to radically ratchet up enforcement.

JZ offers a summary: we can face doom from terrorism or doom from a police state. Bruce riffs on this: if we reach a point where a single bad actor can destroy society – and Bruce believes this may be possible – what are the chances society can get past that moment. “We tend to run a pretty wide-tail bell curve around our species.”

Schneier considers the idea that attackers often have a first-mover advantage. While the police do a study of the potentials of the motorcar, the bank robbers are using them as getaway vehicles. There may be a temporal gap when the bad actors can outpace the cops, and we might imagine that gap being profoundly destructive at some point in the near future.

JZ wonders whether we’re attributing too much power to bad actors, implicitly believing they are as powerful as governments. But governments have the ability to bring massive multiplier effects into play. Bruce concedes that his is true in policing – radios have been the most powerful tool for policing, bringing more police into situations where the bad guys have the upper hand.

Bruce explains that he’s usually an optimist, so it’s odd to have this deeply pessimistic essay out in the world. JZ notes that there are other topics to consider: digital feudalism, the topic of Bruce’s last book, in which corporate actors have profound power over our digital lives, a subject JZ is also deeply interested in.

Expanding on the idea of digital feudalism, Bruce explains that if you pledge you allegiance to an internet giant like Apple, your life is easy, and they pledge to protect you. Many of us pledge allegiance to Facebook, Amazon, Google. These platforms control our data and our devices – Amazon controls what can be in your Kindle, and if they don’t like your copy of 1984, they can remove it. When these feudal lords fight, we all suffer – Google Maps disappear from the iPad. Feudalism ended as nation-states rose and the former peasants began to demand rights.

JZ suggests some of the objections libertarians usually offer to this set of concerns. Isn’t there a Chicken Little quality to this? Not being able to get Google Maps on your iPad seems like a “glass half empty” view given how much technological process we’ve recently experienced. Bruce offers his fear that sites like Google will likely be able to identify gun owners soon, based on search term history. Are we entering an age where the government doesn’t need to watch you because corporations are already watching so closely? What happens if the IRS can decide who to audit based on checking what they think you should make in a year and what credit agencies know you’ve made? We need to think this through before this becomes a reality.

JZ leads the audience through a set of hand-raising exercises: who’s on Facebook, who’s queasy about Facebook’s data policies, and who would pay $5 a month for a Facebook that doesn’t store your behavioral data? Bruce explains that the question is the wrong one; it should be “Who would pay $5 a month for a secure Facebook where all your friends are over on the insecure one – if you’re not on Facebook, you don’t hear about parties, you don’t see your friends, you don’t get laid.”

Why would Schneier believe governments would regulate this space in a helpful way, JZ asks? Schneier quotes Martin Luther King, Jr. – the arc of history is long but bends towards justice. It will take a long time for governments to figure out how to act justly in this space, perhaps a generation or two, Schneier argues that we need some form of regulation to protect against these feudal barons. As JZ translates, you believe there needs to be a regulatory function that corrects market failures, like the failure to create a non-intrusive social network… but you don’t think our current screwed-up government can write these laws. So what do we do now?

Schneier has no easy answer, noting that it’s hard to trust a government that breaks its own laws, surveilling its own population without warrant or even clear reason. But he quotes a recent Glenn Greenwald piece on marriage equality, which notes that the struggle for marriage equality seemed impossible until about three months ago, and now seems almost inevitable. In other words, don’t lose hope.

JZ notes that Greenwald is one of the people who’s been identified as an ally/conspirator to Wikileaks, and one of the targets of a possible “dirty tricks” campaign by H.B. Gary, a “be afraid, be very afraid” security firm that got p0wned by Anonymous. Schneier is on record as being excited about leaking – JZ wonders how he feels about Anonymous.

Schneier notes how remarkable it is that a group of individuals started making threats against NATO. JZ finds it hard to believe that Schneier would take those threats seriously, noting that Anon has had civil wars where one group will apologize that their servers have been compromised and should be ignored as they’re being hacked by another faction – how can we take threats from a group like that seriously? Schneier notes that a non-state, decentralized actor is something we need to take very seriously.

The conversation shifts to civil disobedience in the internet age. JZ wonders whether Schneier believes that DDoS can be a form of protest, like a sit in or a picket line. Schneier explains that you used to be able to tell by the weaponry – if you were sitting in, it was a protest. But there’s DDoS extortion, there’s DDoS for damage, for protest, and because school’s out and we’re bored. Anonymous, he argues, was engaged in civil disobedience and intentions matter.

JZ notes that Anonymous, in their very name, wants civil disobedience without the threat of jail. But, to be fair, he notes that you don’t get sentenced to 40 years in jail for sitting at a lunch counter. Schneier notes that we tend to misclassify cyber protest cases so badly, he’d want to protest anonymously too. But he suggests that intentions are at the heart of understanding these actions. It makes little sense, he argues, that we prosecute murder and attempted murder with different penalties – if the intention was to kill, does it matter that you are a poor shot?

A questioner in the audience asks about user education: is the answer to security problems for users to learn a security skillset in full? Zittrain notes that some are starting to suggest internet driver’s licenses before letting users online. Schneier argues that user education is a cop-out. Security is interconnected – in a very real way, “my security is a function of my mother remembering to turn the firewall back on”. These security holes open because we design crap security. We can’t pop up incomprehensible warnings that people will click through. We need systems that are robust enough to deal with uneducated users.

Another questioner asks what metaphors we should use to understand internet security – War? Public health? Schneier argues against the war metaphor, because in wars we sacrifice anything in exchange to win. Police might be a better metaphor, as we put checks on their power and seek a balance between freedom and control of crime. Biological metaphors might be even stronger – we are starting to see thinking about computer viruses influencing what we know about biological viruses. Zittrain suggests that an appropriate metaphor is mutual aid: we need to look for ways we can help each other out under attack, which might mean building mobile phones that are two way radios which can route traffic independent of phone towers. Schneier notes that internet as infrastructure is another helpful metaphor – a vital service like power or water we try to keep accessible and always flowing.

A questioner wonders whether Schneier’s dissatisfaction with the “cyberwar” metaphor comes from the idea that groups like anonymous are roughly organized groups, not states. Schneier notes that individuals are capable of great damage – the assassination of a Texas prosecutor, possibly by the Aryan Brotherhood – but we treat these acts as crime. Wars, on the other hand, are nation versus nation. We responded to 9/11 by invading a country – it’s not what the FBI would have done if they were responding to it. Metaphors matter.

I had the pleasure of sitting with Willow Brugh, who did a lovely Prezi visualization of the talk – take a look!

April 3, 2013

#GetRewired

Wow! 35 of you contributed more than 70 possible hashtags for me to use while discussing my new book. I don’t have a final choice, but here are my 12 favorites, and the folks who’ll be receiving advance reading copies of the book. I’ll try to reach you via Twitter, but if you’re on this list, feel free to send me an email at ethanz AT mit DOT edu.

My favorites:

@elpollofarsante: #RewireUS

@gwbstr: #WorldRewired

@joeahand: #globalBridges

@neha: #RewireNow

@cmperatsakis: #rewireIT

@caparsons: #whywedontconnect

@jon_penney: #PlanetRewired

@jhaas: #bitswithoutborders

@barrioflores: #EZRewire

@m_older: #globalwires

@mikewassenaar: #reallyconnect

@luisdaniel12: #GetRewire or #GetRewired

and an honorable mention:

@jhaas: #buythisbookorthepuppygetsit

#GetRewired is currently my favorite, but I reserve the right to change. If you’re a winner, look for an @message on Twitter from me, or send me an email with your mailing address.

Ethan Zuckerman's Blog

- Ethan Zuckerman's profile

- 21 followers