Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 24

June 20, 2013

The Launch of Rewire

Rewire officially launched Monday, and I’ve had the chance to do a couple of radio interviews about the book, with Anthony Brooks at Radio Boston and with Brian Lehrer on his show on WNYC. I had great fun with both radio hosts, and was reminded of how grateful I am for public radio, which is often the best forum for people to talk about books and big ideas to a broad audience. The recording of my WBUR appearance is here, and my WNYC appearance is here.

Two of the web’s best loved and best read sites have been kind enough to feature excerpts from the book this week. Slate is running an excerpt from the book’s opening chapter, “Connection, Infection, Inspiration”, which looks at whether cyberutopianism is such a bad thing. (To echo a conversation I had with Ian Bogost on Twitter, cyberutopianism is certainly an unhelpful word, and not what I really want to defend. I’m arguing more for awareness of the strengths and limits of our tools, and for the belief that we can make better tools.) Quartz is running an excerpt from chapter 5, “Found in Translation”, which looks at how the web has become massively multilingual. I’m grateful to both for being kind enough to feature the book.

The Berkman Center is hosting the formal launch of Rewire this coming Tuesday night, June 25, at Wasserstein Hall on the Harvard Law School campus. I’ll talk about some of the core ideas of the book and three friend who’ve been kind enough to read what I’ve written will offer reactions: David Weinberger, Judith Donath and Ann Marie Lipinski. If you’re in Cambridge, please come… and if you are coming, please RSVP, as space is limited. If you’re not able to come, I’ll be talking about some of the same ideas I shared earlier this month at Personal Democracy Forum – video of my talk at PDF is here.

Two requests:

- I am not doing a formal book tour for Rewire. Instead, I’m doing lots of radio and podcast appearances. If you have a podcast on related topics and want to do a skype interview, let me know. Ditto if you have a radio show. But I am also open to giving talks and readings in person. I’m using a new platform called Togather. Basically, the idea is this: if you want to host a book talk and have me attend, you can propose a talk on Togather. If we can make it work – i.e., if I’m available and if you can promise a certain number of books sold or RSVPs – I am open to either appearing in person or via Skype. I’m much more likely to accept invitations in the MA/Vermont/Upstate New York area, as well as NYC, Boston, Philly or DC, that elsewhere, but I am always happy to Skype. If you’re at all interested, learn more at my Togather page.

- If you’ve read the book, please add a review on Good Reads or Amazon.

Thanks for tolerating my relentless self-promotion, and if you’ve bought the book (or just read a friend’s copy), thanks so much.

June 12, 2013

Linking news and action

Swiss author and entrepreneur Rolf Dobelli recently published a provocative essay titled “News is Bad for You” in The Guardian. The essay describes news – particularly fast-breaking, rapidly updated news – as an addictive drug, inhibiting our thinking, damaging our bodies and wasting our time. Dobelli is so concerned with the negative effects of news that he’s cut himself off from consuming news for the past four years and urges that you do the same.

His arguments attracted angry responses within The Guardian‘s newsroom. Madeleine Bunting writes, “As Dobelli described his four-year news purdah to a group of Guardian journalists last week, there was a sharp intake of collective breath, nervous laughter and complete astonishment. How could someone suggest such a thing to a journalist?”

I had a different reaction to Dobelli’s provocation. I found it pretty persuasive. I shared the article with students in a class I teach called “News and Participatory Media”, and asked the students for their reactions. Many found Dobelli’s case compelling, especially those students who were mid-career journalists. Much of what frustrated them about their profession was bluntly identified in Dobelli’s piece: too often, news is a set of disconnected snippets that promises to inform and empower, but merely entertains, distracts and ultimately misleads.

While Dobelli offers a persuasive set of problems, his proposed solution – stop reading news – strikes me as unhelpful and selfish. You personally may benefit from the time you reclaim in kicking the news habit, but there is likely a societal cost in encouraging people to opt out of consuming the news. A democratic form of government presumes an informed populace that can select appropriate representatives and identify issues that merit public debate. As Bunting notes in her response, a happy, docile and ill-informed citizenry is the precursor to a Huxleian vision of totalitarianism.

Dobelli might accept the accusations of selfishness. His essay is adapted from his new book, “The Art of Thinking Clearly”, which is an odd example of a self-help book. Deeply inspired by Naseem Taleb’s work linking cognitive science and economics, Dobelli outlines 99 cognitive shortcomings, errors and fallacies in an attempt either to steer us towards smarter decisionmaking or, more likely, to bludgeon us into a realization that human beings are pretty lousy at making rational decisions. By the end of the book, Dobelli admits that he rarely considers all these errors and fallacies in making decisions and simply goes with his gut – however, he wants us to have these tools handy for the really important decisions. Those decisions, his examples suggest, generally have to do with making investments as wisely as Warren Buffet or getting good deals on expensive cars. His is not a book about civics – it’s a book about maximizing your personal gains.

If we take Dobelli’s criticism seriously but reject his proposed solution, one next step is to look for ways to address the shortcomings of contemporary journalism. If we don’t like the sort of repetitive, click-seeking, shallow journalism that Pablo Boczkowski identifies in his book “News at Work“, we need to find ways to support “slow news” that focuses on investigation and contextualization of breaking news. If we are dismayed by how both new and old media got many details of the Boston Marathon bombing and the manhunt for the bombers wrong, we need either to slow newsrooms down, or to build better tools to help both newsrooms and readers cross-check and verify breaking news reports.

I can (and frequently do) point to people and projects focused on solving the problems Dobelli poses , but I’m left with two of his challenges that I can’t ignore or solve. They are related points: “News is irrelevant” and “News makes us passive.” These intertwined problems strike me as uncomfortably hard to address.

Dobelli asks, “Out of the approximately 10,000 news stories you have read in the last 12 months, name one that – because you consumed it – allowed you to make a better decision about a serious matter affecting your life, your career or your business.” Most stories, he argues, “are overwhelmingly about things you cannot influence. The daily repetition of news about things we can’t act upon makes us passive. It grinds us down until we adopt a worldview that is pessimistic, desensitised, sarcastic and fatalistic.”

I can quibble with these generalizations. A news story may convince us to vote to oust a politician, to donate money to a relief effort or work on a cause locally or globally. But I take his overall point seriously: if news isn’t helping us make decisions or take actions, why would we pay attention to it, or bother paying for it?

There’s another way to interpret Dobelli’s complaint, not as an indictment of news, but of the limited tools we have for civic engagement. When we read a horrifying story like the explosion of a fertilizer factory in West, Texas, what options do we have as outraged citizens? We could raise funds to help affected families rebuild their homes and bury their dead, but that hardly addresses the core issues of America’s half-assed and underfunded approach to regulating workplace safety. We can promise ourselves that we’ll vote out the politicians responsible, but we probably can’t – Texas prides itself on being one of America’s least regulated states – and there are very few pro-regulation voices like that of Elizabeth Warren on either side of the political aisle these days. Surely there’s an action we can take that falls somewhere between making a donation to victim’s families and mounting a campaign to overhaul America’s approach to business regulation?

If we believe news is important to a democracy, we need mechanisms by which news turns its readers towards engagement and action. If hearing about the shoddy safety practices in West, Texas doesn’t lead to some sort of change, then Dobelli is right: the news is irrelevant and likely to render us passive.

This February, the Knight Foundation gave a $985,000 grant to TED, organizers of a popular and highly visible series of conferences that feature “ideas worth sharing”. The purpose of the grant was to let TED take a close look at whether TED talks were inspiring people to take action, and to help link TED talks more closely to action. The grant attracted some criticism from commentators who wondered whether it made sense to fund TED to study its own effectiveness, but not much conversation about the idea of linking TED’s content with participation.

(Disclosure: I have long associations with both Knight and TED, and Knight is the primary fiscal sponsor of my research center.)

The day before the announcement of the grant, I attended a brainstorming session hosted by Knight and TED. June Cohen, TED’s executive producer for media, asked the attendees: When TED.com relaunches later this year, what if some talks included a set of actions a viewer could take if he or she found a talk compelling?

TED plans to invite a subset of their speakers to connect actions with their talks, likely starting with talks from this February’s conference. Speakers would be asked to suggest three actions a viewer could take. TED would work with speakers to craft the suggestions, but they would ultimately be the speaker’s suggestions, not TED’s, to ensure independence between the speaker and TED. As for which actions might make sense to promote, how to structure those actions for maximum effectiveness, and how to measure that impact? These remain open questions.

The questions TED is asking itself are related to the questions Dobelli asks about the news. Some of the ideas that TED sees as “ideas worth spreading” are ideas that could lead to transformative change if implemented at scale. By giving attention to scientists who are engineering bacteria to produce ethanol, or scholars who want to rebuild schools with a renewed focus on creativity, TED promotes ideas as solutions they believe can solve longstanding problems.

But it’s also possible that these ideas are distractions, pat solutions to complex problems, offered more as entertainment than as a meaningful path towards change. We might judge the utility of TED’s ideas by whether they empower us to take action and make change, or whether they leave us sitting on the sidelines, either through hope that smart technologists will solve our problems or despair about the scale of the problems we face. As with news, we might evaluate TED’s talks, in part, on whether they empower us, as members of the audience, to make change in the world, or whether they leave us as passive observers.

Some of these ideas might become actual solutions through the influential and powerful people who attend the TED conference and decide to support the ideas they find compelling. With an audience that routinely includes Google’s founders and some of Silicon Valley’s wealthiest venture capitalists, a scientist with a novel fuel source might give a great talk and find backing to commercialize her work. (There’s a long history of collaboration between TED presenters and attendees – see Google’s purchase of Hans Rosling’s remarkable Gapminder visualization tool.)

But another path towards solution is through reaching TED’s global audience online. Popular TED talks are seen by millions of viewers, many of whom react to talk wondering what they can do as individuals to bring about change.Through linking inspiration to action, TED has the potential to mobilize millions to take action around the causes TED features. And TED may strengthen its brand as a space for new ideas and inspiration, because viewers who can find a path to action are more likely to feel empowered and less likely to be frustrated by high-minded ideas that don’t and won’t come to life.

So I was surprised to hear June raising the issue of editorial integrity: the concern that TED might sacrifice some sort of neutrality in promoting one course of action over another. After all, TED has already made a major editorial judgment in selecting some speakers and not others. Because appearing on the TED stage is a major boost to a speaker’s visibility, far more people want to speak at TED than are able to, and TED’s curators have enormous gatekeeping power, both in deciding who gets on stage and who is kept off.

June argued that there’s a distinction between featuring compelling and innovative ideas and proposing specific paths of action to bring those ideas to fruition. TED could make an editorial judgment about whether a speaker had an idea worth spreading, she felt, but wasn’t in a good position to propose steps a viewer of a TED video could take to bring that vision to life.

TED is not a newspaper, but questions of connecting information with inspiration and activation are being raised in newsrooms around the world. Should organizations dedicated to the spread of news, ideas, and analysis limit themselves to sharing information with their audiences, or should they help the people they reach engage and take action?

This question points out a conflict between two values many journalists hold. Journalists are often taught that their job is to inform their readers, but not to promote a particular course of action. To do so would be to commit “advocacy journalism”, the promotion of an agenda masquerading as the sharing of facts. At the same time, many journalists enter the profession with a hope that their actions will lead to change in the world. Inspired by investigative journalists, muckrakers, and those who’ve championed whistleblowers, their hope is to uncover and expose malfeasance and see the corrupt ousted and punished.

These values aren’t in conflict so long as you accept a particular theory of change: give people information they need to see what’s wrong in the world, and they will take action to right wrongs. When this works, the results can be profound. When the Boston Globe, building on work done by the Boston Phoenix, exposed Cardinal Bernard Law’s attempts to protect and reassign pedophile priests, it led to Law’s resignation, charges brought against over 100 priests and a crisis in the Catholic church that may help spare future parishioners from clergy sexual abuse.

But addressing the “information deficit” doesn’t always lead to change. Much thoughtful analysis of climate change has been published, but we are still far from widespread, aggressive action to slow carbon emissions, and we’ve globally passed the 350 parts per million threshold scientists have long warned is a maximum safe level for atmospheric carbon dioxide. Hard as it has been for the Catholic Church to wrestle with sexual predators in the clergy, it’s been far harder for the US, India and China to come to a common understanding of a balance between development, growth and emissions.

Reading about Arctic ice collapse is informative, but hard to translate into a course of action. As warming accelerates, swapping your SUV for a hybrid remains a fine idea, but seems unlikely to prevent trapped methane from escaping from melting permafrost. These stories may inspire some readers to become climate researchers or activists, but it’s likely that for many they reinforce a sense of powerlessness and disengagement. If reading a story makes you more informed about a problem, but less likely to act in response to that problem, is that a net positive or negative?

There’s a trap in the other direction, of course. Fox News heavily promoted Tea Party rallies as a way viewers could get involved with campaigns to reform tax policy. They were accused of both artificially creating a political movement, and of sacrificing any claims they might make towards journalistic neutrality. It’s undeniably possible to find yourself prioritizing ideology over objective reporting, and in doing so, sacrifice informing people broadly and fairly on the road to becoming a more effective advocate.

There is a small set of journalistic organizations looking for a middle ground, a way of connecting journalism to engagement in a way that avoids sacrificing reporting for advocacy. In that sense, they may be fellow travelers to June and TED, as they look for ways to advocate for ideas, but seek specific solutions more broadly.

David Bornstein has been writing a series of columns called “Fixes” for a New York Times blog, profiling people and organizations with novel solutions to challenging problems. Bornstein calls this work “solutions journalism”, suggesting that the next step for journalists after exposing a social problem is to feature sound reporting on different approaches to problem-solving.

Other projects try to connect stories directly to actions an interested reader might take. Shoutabout, a start-up news portal, invites readers themselves to share actions a reader can take and information sources where readers can learn more. A Washington Post story about marriage equality is paired with an invitation to donate to the Human Rights Campaign as well as a link to read a set of contextual background stories.

Because readers themselves submit the links to learning and action materials, ShoutAbout offers news publishers a way to invite participation without crossing the advocacy line. The platform works for the right as well as for the left: a news story about Ted Nugent’s brother writing an Op-Ed in support of background checks offers readers a link to donate to the NRA as well as a link to contact their elected officials in support of background check legislation.

Participant Media’s Take Part site combines news stories with petitions and pledges readers can sign, and an “impact dashboard” that tracks the campaigns they’ve joined. By tracking engagement through the dashboard, Take Part encourages readers to think of themselves taking part not just in a single campaign, but as a part of their online lives.

Do these efforts cross a line between reporting and advocacy? A new report from award-winning non-profit newsroom ProPublica offers suggestions for how we might think about the question. A whitepaper commissioned by the Gates Foundation and prepared by ProPublica examined how the newsroom measures the impact of their work. Before discussing impact, the ProPublica authors examine the question of whether journalists should be seeking impact from their work. They conclude that they should, and offer a distinction between journalism and advocacy. Journalism, they argue, begins with questions and progresses to answers, while “Advocacy begins with answers, with the facts already assumed to be established.” As a result, “when a problem is identified by reporting, and when a solution is revealed as well… it is appropriate for journalists to call attention to the problem and the remedy until the remedy is put in place.”

ProPublica understands that they will be accused of “crusading journalism”, but argues that it’s okay to crusade if journalists are led to propose solutions they have found in course of their investigations, rather than through preconceptions or partisanship. This seems like good advice for anyone working for social change: before taking on the task of advocating for a particular solution, do the work to determine whether this is the best solution you can find, or simply the one you’ve heard the most about. But ProPublica rejects the idea that a journalist’s responsibility is to document a problem and hope that readers find an appropriate solution.

What does this mean for TED and the idea of linking paths of engagement to TED talks? TED is already exercising editorial judgment over what constitutes “ideas worth spreading” and who benefits from the attention associated with appearing on the TED stage and website. Much as a newspaper engages in a form of advocacy by reporting a story on the front page rather than burying it deep inside a paper (or excluding it entirely), TED is already engaged in promoting some ideas at the expense of others, amplifying some, though not all, ideas presented on TED stages on the TED.com website.

(The controversy over Nick Hanauer’s talk at TED, a 3-minute talk about income inequality as part of the 2012 Long Beach conference, centered on TED’s decision not to feature the talk on the TED.com site. Hanauer went to the press, and some supporters of Hanauer argued the failure to post the talk was a form of censorship. Chris Anderson, TED’s curator, argues that it’s more analogous to sending an op-ed to the New York Times and having them decline to publish it, as TED and TEDx events generate thousands of talks a year, and only one is featured on the site per day.)

David Bornstein might suggest that TED feature speakers that offer compelling solutions to our most pressing problems. ProPublica might encourage TED’s curators to thoroughly examine complex problems and promote solutions and speakers that emerge from the research. But it is unclear whether TED should offer a platform for a speaker to propose ways audience members can help to solve problems, or whether TED should be engaged in designing or refining those solutions. While TED is comfortable auditioning speakers and selecting the best talks, endorsing plans of action feels uncomfortably like political activism to some, or simply dangerous, in that TED isn’t able to evaluate whether the actions proposed are appropriate or helpful.

The problem is this: great TED speeches are inspiring, but they don’t always include a call to action. Sir Ken Robinson’s talk on schools and creativity is perhaps the most watched talk the organization has ever published. It’s an engaging and funny exploration of different forms of intelligence and the poor job our schools do accommodating these different ways of learning. There are very few concrete, actionable takeaways from the talk – Sir Ken’s work in the talk is to persuade us the importance of creativity in education and inspire us to work on bringing creativity into education.

It’s possible Sir Ken has three concrete next steps he’d like the 15 million people who’ve viewed his talk to take. But that’s not necessarily the case. Had TED asked me for three actions I wanted viewers to take in reaction to my (much less popular) TED talk, I would have asked them to join the Global Voices mailing list, then desperately fumbled for two more ideas. Much as speakers need – and receive – coaching on their stagecraft and their slides, it’s likely many of them need help figuring out what they’d like an audience to help them do.

In a talk I gave at the 2013 Digital Media and Learning Conference, I suggested that one way to consider civic engagement was in terms of engagements that are “thin” or “thick”. Thin engagement requires little thought on your part: you can sign a petition, take a pledge, give a contribution. Campaigns that use thin engagement are often launched by organizers who have chosen a solution to a problem, and see the challenge as lining up support behind their solution. Thin activism relies on scale for impact – actions are easy to undertake in the hopes that thousands will take part and that their collective small actions will lead to significant impact. Some of my students at Center for Civic Media recently made the case that 2 million Facebook users changing their profile pictures to a variant of the Human Rights Campaign’s red and pink equality symbol was a form of engagement that was thin but effective, demonstrating how many friends and allies gay people had.

By contrast, thick engagement is designed to call on a broader range of inputs from participants, including their creativity, strategic sensibilities, and ability to make media, research, deliberate or find solutions. Campaigners know there’s a problem they want to solve, but ask what you think they should do to address it. Thick engagement can be very difficult to scale, as it involves deliberation and debate between people who may disagree on the appropriate course of action, but it’s often very satisfying and engaging for those who participate in it, as they feel valued for their ideas and connections, not just for their nominal participation or donation. Critically, they see themselves as partners in bringing an idea to life, more deeply engaged than if they’d merely written a check or signed a petition.

TED has some experience asking its community for thick forms of engagement. From 2005 through 2009, TED awarded $100,000 and a wish to “change the world” to three individuals. In 2010, they narrowed the prize to one winner, and in 2013, raised the prize to $1 million. The money aside, TED has argued that the real value of the prize is that members of the TED community – the people who attend the TED conferences and the staff of the organization – work with prize winners to bring wishes to life. Street artist JR, winner of the 2011 TED prize, worked with members of TED’s community to post people’s portraits on buildings and walls around the world. In Tunisia, after Ben Ali’s government fell, JR worked with Tunisian activists he met through TED to cover the dictator’s pictures with photos of ordinary Tunisians, just one of the projects in over 100 countries involving 120,000 posters.

It’s likely that the experience of taking photographs, picking evocative sites – like Tunisia’s ministry of information – and wheatpasting these posters into place is an engaging and thick form of participation in JR’s project. It’s likely that people in the TED community helped with the printing and distribution of the posters as well, which surely involved its own sort of complex and engaging problemsolving. But it takes real thought and care – and, in this case, JR’s artistic vision – to design projects that tens of thousands of people can take engage with in such a rich way. Many of the projects with which Shoutabout and Take Part invite readers to engage demand no more than an online signature or donation. It’s not hard to understand why some of these campaigns are dismissed as “slacktivism”.

For journalists who want to connect their readers to meaningful engagement, or TED speakers who want to use their 18 minutes in the spotlight to start building a movement, identifying and designing opportunities for engagement is likely to be a new art form. Most journalists can’t start new organizations to implement solutions they’ve helped identify – at best, they can point readers to exemplary organizations they’ve reported on, as Bornstein does. Those organizations are then faced with a pleasant conundrum: can they harness the attention they receive beyond asking for money? When Larry Lessig’s compelling new TED talk drives viewers to his Rootstrikers anti-corruption project, will they be content to sign and share petitions, or can Rootstrikers help them become active, creative and engaged parts of Lessig’s movement?

Advocacy organizations use the idea of a “ladder of engagement” to design projects new recruits can undertake. After putting a bumper sticker on a car, a voter is asked to put up a lawn sign, then staff a phone bank, then canvas door to door, and so on. Not all volunteers make it up the ladder, but those that do are experienced and dedicated and, ideally, are invited to help develop the strategy of the campaign. I’ve suggested that to encourage thick engagement that has impact, we need to help people deepen their understanding of an issue as they climb a ladder of engagement.

ShoutAbout’s model, which expands a story into opportunities to learn as well as to act, is a step in the right direction. But an organization like TED could do a great deal more. Working with a compelling speaker like Lessig and with the Rootstrikers organization, TED might help design a set of opportunities for engagement that allow people with different interest and skill levels to get involved in different ways. They might also help people drawn to the issue of corruption by Lessig’s talk find a range of information on the topic so readers can explore whether the solutions Larry proposes are the ones they want to advocate for. Ultimately, TED might find itself hosting discussions not just about supporting Lessig and Rootstrikers, but in developing other complementary – or competitive – strategies to the engagements originally suggested.

There’s another possibility, which is that by focusing on thin forms of engagement, TED may alienate its core constituency, the community members who’ve been willing to make in-depth commitments to try to bring projects to life. Advocacy organizations work to turn thinly-engaged participants into thickly-engaged movement leaders. Moving in the other direction, expanding out from a core of engaged participants to be more inclusive may alienate those people who are already involved. (TED has already wrestled with this challenge in moving from a small, exclusive conference to becoming a global media brand with talks watched by millions.) At the very least, moving from facilitating cooperation between a small group of highly empowered individuals to a larger popular movement is likely to be a challenging process (and could alter the end results in ways positive or negative).

Is TED willing to get engaged in helping design new engagements, or providing space for viewers to debate and design new forms of involvement? Are news publications? In either case, the most challenging aspect of linking compelling content to engagement is measuring impact.

ProPublica’s white paper offers both caution and hope for measuring the impact of investigative and explanatory reporting. Measures of impact need to go beyond counting stories written or pageviews received. If millions of people read a story but can do nothing, there will be less impact that a story where few read it, but one is in position to effect a change. As a result, ProPublica tracks how many people read its stories and how many publications they appear in, but they also maintain a tracking report that follows actions influenced by a story, opportunities to influence change and changes that have resulted.

In the case of a ProPublica story like Dollars for Docs, an exposé of doctors who accept large fees from drug companies for consulting and public speaking, it’s easy to understand these actions, opportunities and changes – ProPublica can track policy changes at hospitals and medical schools that restrict doctors’ ability to accept outside consulting fees. But it’s much harder to know how to track the success or failure of a project like JR’s, where the exciting outcomes may be in the joy or empowerment of seeing the faces of contemporary and historical Lakota figures against the backdrop of the Great Plains, or the faces of ordinary Haitians on the walls of a rebuilding Port au Prince.

Focus closely on measuring the impact of engagement tied to a story or a talk, and you’re likely to prefer engagements tightly tied to straightforward theories of change: we can fight corruption by getting politicians to commit to refusing money from lobbyists, and we can track our progress by seeing who’s taken the pledge and whether they honor it. If a handful of politicians took this pledge before Lessig’s talk and an accompanying TED campaign urging viewers to call their Congresspeople, and dozens took the pledge afterwards, TED might well claim impact from an engagement they helped design.

But we want metrics that are capable of recognizing the impacts of a project like JR’s Inside Out. And if we hope readers and viewers will suggest their own forms of engagement and build their own movements, we need not to track a single tactic, like calls to Congresspeople, but a whole set of metrics that track whether corruption is changing and whether our efforts are having an impact. If we don’t find ways to consider these impacts, it’s possible that an effort like TED and Knight’s could run the risk of launching dozens of Kony 2012s a year: high profile movements that gain lots of attention, but have a difficult time demonstrating their impact.

At the meeting hosted by TED and Knight, I told a story about giving my TED talk in 2010. TED speakers receive a wonderfully over-the-top stone tabled emblazoned with the “TED Commandments”. One orders speakers to “Prepare for impact”. What it should say is “Prepare for attention”.

Being able to reach a large audience, on the TED stage or through a newspaper, offers no guarantee that words will have an impact. Linking that attention to meaningful action is difficult to accomplish. Dobelli’s warning is a simple one: protect your attention, as it is a scarce commodity. But unless we invest our attention into ideas and events that matter, we miss the opportunity to make change at a scale larger than that of our own lives.

My colleague Sasha Costanza Chock offered five productive ways people outraged by revelations about the NSA’s PRISM program might respond, an excellent example of linking news to action.

June 6, 2013

Sumo practice at Oguruma Beya

I like sumo. A lot. I follow the tournaments online, watching matches on YouTube a few hours after they’ve aired, then reading commentary on fan sites in English and Spanish. I have, one or twice, participated in virtual sumo leagues, performing dismally as there’s not always much overlap between the style of sumo I love (focused on agility and throwing techniques) and the style of sumo that wins. I show sumo matches to friends, hoping to turn them into fans, and I’ve been known to give talks at academic conferences on the globalization of this very Japanese sport.

But I’ve seen very little sumo in person. This past week was only my second trip to Japan, and while I was privileged to attend a day’s bouts in Ryuguko Kokugikan, Tokyo’s temple of sumo, I sat in the nosebleed seats, peering through the telephoto lens on my camera to follow the action.

I have a very different perspective on the sport after an incredible experience yesterday morning. On Monday, I gave a talk at Tokyo Midtown Hall, organized by Japan’s most prestigious newspaper, Asahi Shimbun, and by Dentsu, Japan’s leading marketing and communications firm. My friend Mr. Mori and his colleagues at Dentsu organized a morning visit to the Oguruma Beya, the dormitory and training academy where a dozen sumo rikishi live and practice.

We arrived in an unremarkable residential neighborhood before 9am. Without the help of Mr. Kitoh, who used to work with the Japan Sumo Association in his role with Dentsu sports marketing, I would have walked past the building unaware of what was taking place inside. We entered, removed our shoes, and walked a few steps before we entered the room that houses the dohyo, the dirt-covered arena where rikishi compete. The dohyo occupied most of the room – a narrow wooden shelf on two sides of the room held half a dozen cushions, where we sat to watch the practice.

The oyakata, the former Ozeki Kotokaze, sat in a leather recliner in the far corner of the room, watching his trainees intently, but largely without comment. As we entered, the rikishi were sparring, fighting bout after bout, with the winner remaining to fight a new challenger. The athletes practicing compete in sumo’s lower ranks; I caught a glimpse of Takekaze and Yoshikaze, the stable’s two top division fighters, in kimonos, heading out into the street.

That the fighters we saw train were not the top guys didn’t diminish the intensity of the practice. Bouts took place every minute or so, lasting ten to thirty seconds, and the winning fighter rarely took a break beyond wiping his face with a towel before facing his next challenge. Other rikishi stretched and practiced charging forward and background on the edges of the dohyo as matches took place in the center.

A sumo tournament features a few dozen bouts, spread out over a long afternoon. Because sumo is as much religious ritual as athletic contest, there are several minutes of preparation before each bout, which often takes as little as five seconds. We likely saw as many matches in an hour of practice as we’d see in two days of tournament sumo. The dominant sound in the room was men panting for breath, as they recovered from one match and prepared for the next. Matches began with no fanfare, no long stare-downs – both rikishi dropped their fists, exploded into one another with a fleshy smack and quickly fought to conclusion. The few matches where one fighter had clearly underperformed were quickly reset and repeated. After an especially good match, a more senior rikishi would huddle with the loser offering advice on what had gone wrong.

Many of Oguruma’s rikishi are massive, with one weighing in above 200kg, which is heavy even by sumo’s standards. I was fascinated by two of the men working out. One was a teenager, built like a rugby player, strong but lanky and lean, without the massive belly and thighs typical of most rikishi. When I praised his performance after the practice, the oyakata told us that he was only 103kg, and had trained for only one year. Given his ability to beat three or four much larger men in a row, it’s easy to imagine him becoming a serious competitor if he’s able to add 30kg to his frame. Another impressive competitor defeated virtually everyone he faced, rarely being forced into shoving matches by larger men by making good use of turning and pivoting, gripping the other man’s muwashi (belt) and spinning him outside of the ring. I was gratified that my friend Mr. Mori, a sumo fan, agreed that these were the two to watch, more impressive than the more mammoth men they moved around the ring.

With a command from the oyakata, the rikishi began a drill I remember from American football practice – moving a blocking sled. In this case, the sled is another wrestler, who slides across the dohyo on a firmly planted foot thrust behind the body. After four passes, the “sled” gently taps his partner on the back, “knocking” him to the ground into a smoothly executed breakfall.

My friend, Ms. Ohnishi, gasped the first time she saw one of these huge men fall so elegantly. My gasp came when all the wrestlers executed full splits, then lowered themselves into push-up position. From years in the martial arts, I know how few people are able to execute a full split, and I’m used to seeing only the most slender and lithe execute the feat. I’ve insisted for years that rikishi are remarkable athletes, but until I saw a 400 pound man execute a flawless split did I understand quite what a blend of strength, flexibility and power the sport requires.

We spoke briefly with the oyakata afterwards, who gave us some insight into the physical strains of sumo. He was the tallest Japanese man I encountered on my trip, standing about six feet tall, still powerfully built in his 60s. He explained that he had recently had back surgery, and had been ordered by his doctor to lose 30kg, the vestiges of his fighting weight. His recliner wasn’t a mark of luxury or power, just a concession to the injuries sumo had done to his body.

I’m a large man, just under the mass of some of the lightest sumo wrestlers. (There’s one remarkably brave Czech, Takanoyama, who fights at 100kg, way lighter than I am.) I guess I’d assumed that sumo wrestlers were similar to football’s offensive linemen, who are massive and broad men, sometimes with a layer of fat covering powerful frames. But the sumo body is different – these guys are small, muscular guys who’ve added 100kg to their frames through a strict dietary regimen. Most return to a normal weight that’s half of their fighting weight. Until watching a young man who hadn’t yet gained his fighting mass work out, I hadn’t understood that sumo is, in effect, a form of extreme body modification.

After exchanging gifts with the oyakata, I left the dohyo with Ms. Ohnishi, who was having a hard time getting her head around the handsome young man who was training to become a rikishi. “He could have a girlfriend, he’s a good looking guy. Why does he want to get so fat?” She noted that sumo was a popular choice for large boys in post-war Japan, as there wasn’t a lot of food to go around, and at least at a Beya, you were guaranteed to get enough to eat.

My younger Japanese friends are always baffled that I’m fascinated by sumo – it’s something their grandfathers watched, not something they pay attention to. My older Japanese friends tend to assume that it’s part of a respectful attitude towards Japanese culture, and then are surprised that I’m knowledgeable about sumo and ignorant of much of what’s rich and engaging about that endlessly fascinating nation. For me, the beauty of sumo is that it’s so simple – two big men pushing each other around – and so complicated, in terms of techniques, of bodies and of global economics.

I am incredibly grateful to my friends at Dentsu, particularly Mr. Mori, for making this visit possible and for the generous hospitality of oyakata Nakayama Koichi.

A full set of photos and videos of my visit is here.

June 2, 2013

WeChat: Learning from the Chinese Internet

Four year ago, Hal Roberts and I were researching internet censorship by studying the use of proxy servers around the world. Proxy servers are often used to circumvent internet filtering, letting users access content that’s otherwise blocked by a national government, an internet service provider, or a school or business. We found that the usage of these tools, including both free, ad-supported tools and subscription-based VPN services, was surprisingly small: less than 3% of all internet users in countries that aggressively censored the internet.

This surprised us, as there’s been a great deal of dialog in the US about “internet freedom”, a US government policy that supports providing uncensored internet access to people in China, Iran and other nations whose governments filter the internet. Our research suggested that the efforts already underway by projects like Tor and Freegate weren’t being used nearly as much as their authors hoped. This might be due to weaknesses in the tools, but we suspected another motivation: lack of user interest. Hal designed a study of bloggers in countries that censored the internet, asking whether they used circumvention tools. Almost all were aware of the existence of proxy servers, but few used them regularly. When we asked why they weren’t using these tools, most told us that they weren’t very interested in accessing blocked content.

A new paper from Harsh Taneja and Angela Xiao Wu at Northwestern University offers some insights into why this is the case. Taneja and Wu use internet usage data from Comscore to analyze the thousand most globally popular websites, examining their overlapping audiences. Audiences for websites tend to cluster together – people who visit CNN.com are more likely to also visit ESPN.com than people who visit Chinese search engine Baidu. The authors identify a set of 37 “culturally defined markets”, collections of popular websites that seem to be visited predominantly by people who share languages or cultures. Language, while a powerful factor in explaining this clustering, isn’t the sole factor: a cluster of French and Arabic-language sites represents a bilingual North African culture, for example, and an Indian cluster containing mostly English-language sites is distinct from an English-language North American/UK/Australian cluster. And there’s a cluster of football sites that appears to have a truly transnational audience.

One of Taneja and Wu’s most surprising findings is that the Chinese cluster is not significantly more isolated than other cultural clusters: the Turkish, Korean, Vietnamese, Italian and Polish clusters were all less central to the audience map that Taneja and Wu produced. While the authors acknowledge that Chinese internet users are encountering a different subset of internet sites than English-speaking users are accessing, they argue that this is less a result of the Great Firewall, China’s national internet filter, and more a reflection of a tendency to pay attention to content we find culturally interesting and accessible.

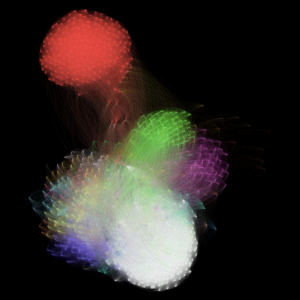

The US/UK/Australian internet is represented in white, the Chinese in red, Spanish in purple, Japanese in bright green. Image from the Taneja and Wu paper.

This paper is likely to generate significant debate about the role of China’s internet censorship. The authors acknowledge that China’s pervasive internet blocking has served as a trade barrier, protecting the local internet industry, which has flourished. But it’s impossible to know whether Taneja and Wu would find different results had Chinese internet users been able to share content on YouTube and Twitter rather than using Youku and Weibo. Still, the popularity of sites like V Kontakt and LiveJournal in Russia and Ukraine, countries that have not engaged in widespread internet filtering, suggest that China might have developed its own set of social media tools without the trade barrier of censorship.

Taneja and Wu argue that culture is a more powerful force leading to internet balkanization than government regulation and I’m inclined to agree. In Rewire, I argue that early hopes that the internet would connect people from different countries and cultures have been challenged by the discovery that people tend to gravitate to content that’s culturally familiar and accessible. Matthew Yglesias is right to term this a golden age for readers of journalism, in that there’s an enormous variety of perspectives accessible online. But studies like that of Taneja and Wu’s suggest that we tend to encounter a small subset of all that’s available online.

This tendency towards cultural locality has implications for our knowledge of global events and perspectives: while in theory, Americans have direct access to Indian news, in practice, our knowledge of events in India is heavily dependent on whether American news outlets cover Indian news and whether our individual social networks amplify that news. But cultural balkanization has another implication as well: it influences what internet tools we encounter and use.

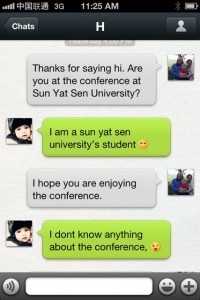

My friend and colleague Jing Wang invited four MIT faculty to join her at Sun Yat Sen University in Guangzhou, China for a symposium on civic media. Before we came to China, Jing insisted we install WeChat on our phones. WeChat is a social networking application made by Tencent, one of China’s internet pioneers. Tencent are the makers of QQ, a massively popular instant messaging service and digital currency, which was waned in popularity with the advent of Weibo, China’s massively popular microblogging service. Sina Weibo has a far greater audience than Tencent’s Weibo service, so WeChat represents Tencent’s strategy for reclaiming market share.

So far, the product has been wildly successful, with 300 million users joining the service in the past two years. My Chinese friends tell me that WeChat meets different social needs for them than Weibo. On Weibo, a social norm of accepting all friend requests means that the service serves as a digital public sphere, not a private conversation. On WeChat, they are more choosy about who they interact with, and use the service to stay in touch with close friends.

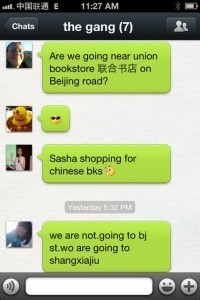

Jing’s logic in asking us to join WeChat was that it’s a convenient way to plan activities with a group of friends. She set up a group for all of us attending the conference and we were able to coordinate our dinner plans and movements around the city by sending text and voice messages to the group, a task that’s surprisingly difficult to accomplish with tools like SMS, Twitter and Facebook. It’s really easy to form these groups – you can share a QR code with friends who are nearby, or you can ask everyone who will participate to shake their phones – the system shows you everyone who shook their phone (anywhere in the world) at the same instant, allowing you to quickly add the discussants in a conference call or a conversation into a group.

(This shake feature can also trigger your phone to listen for music playing, at which point it will identify the song, offer you a link to download the song and the lyrics. Unsurprisingly, the version of the software I downloaded in the US doesn’t have this feature available.)

There are tons of other features to WeChat that make it appealing. Users share “moments”, similar to Facebook status updates, which create an elegantly laid out timeline that serves as a user’s profile. My friend Coco’s profile is featured above – because the timeline is largely picture-driven, it’s not hard to get a sense for what’s going on in a friend’s life at a glance.

Most interesting to me is a set of features designed to let you meet new people through WeChat. Drift Bottle lets you send a voice or text message to a random user somewhere else in the world. If someone receives your message in a bottle, they can respond to you and you can connect with them if the message is an interesting one. (And if it’s an offensive one, you can block or report the user.) One of our Chinese friends explained that it’s fairly common for Chinese social media users to maintain an anonymous account that they use to share deeply personal thoughts with unknown users as a way of venting emotions that are too sensitive to share with friends. Drift Bottle builds on this social practice and turns it into a service.

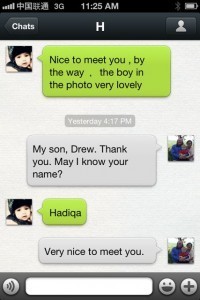

Look Around is similar, but introduces you to other users who are located nearby. Predictably, this feature is often used to search for romantic partners. Most of my Chinese friends were shocked that I had kept the feature turned on, but I quickly befriended a few of the students attending the conference and traded greetings.

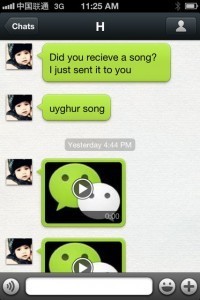

The most charming of the students I met wasn’t actually attending the conference – she was a Uighur student from Xinjiang named Hadiqa, who happened to be nearby and accepted my friend request. We traded some messages, and I mentioned my fondness for Uighur music (Zulpikar Zaidov!), and Hadiqa started sending me Uighur songs. (I can’t play them, probably because I have a crippled, American version of WeChat that can’t share media. If anyone has tech support advice for me on this issue, I’d be grateful, as more Uighur music in my life would be a good thing.)

Facebook and Twitter both have systems to introduce you to other users, but both focus on introducing you to people you’ve got something in common with. Facebook introduces you to people with whom you have mutual friends. Twitter introduces you to people followed by people you already follow. WeChat introduces you to people who are physically nearby, or to total strangers in other parts of the world. This isn’t unprecedented in the US-centric internet – tools like Grindr have been popular for helping people find possible romantic partners, and ChatRoulette introduced people to each other at random in ways that were surprising, fun and often disturbing. But it’s interesting to see the design decisions made for different platforms, if only as a reminder that these decisions are choices: it’s not inevitable that Facebook works to reconnect us to our elementary school classmates rather than introducing us to unfamiliar people around us.

At the end of Rewire, I argue that we’d benefit from building software tools that encourage serendipity, helping us stumble onto information that’s unexpected and helpful. These systems are challenging to engineer, but the main barrier to building them may be our bias towards recommending the familiar and unthreatening. It’s inspiring for me to see a major software company building a system with hundreds of million users that has unexpected encounter as a core feature of the platform. (As friend and colleague Sasha Costanza Chock, fellow voyager on our Guangzhou/WeChat trip noted, I’d probably enjoy a “meet a Uighir” feature included in all my social media tools.)

I follow new media pretty closely, and I’m now embarrassed that it’s taken me two years to try WeChat. I like the platform enough that I am likely to keep using it, especially if I can persuade friends to use it for coordinating social plans. (Before anyone raises the question of whether the platform is monitored and censored, let me say that I assume it is, which would keep me from using it for any sensitive purposes.)

Beyond that, I’m reminded of Taneja and Wu’s core point: it’s not just that the Chinese internet is isolated – the American/UK/Aussie internet is isolated as well. I suspect most mobile app developers in the US haven’t taken a close look at WeChat, or I expect we’d see competitive features coming into our mobile tools. The cultural blind spots we all exhibit have consequences for what we know about the world. We miss interesting and inspiring innovation when we assume our corner of the internet – or of the world – is the place where everything of interest originates.

May 31, 2013

Li Yanhong at Sun Yat Sen University

Yanhong Li, Vice Dean and Associate Professor of Communications at Sun Yat Sen University, offers an example of ancient organizing history in China: a case from four years ago. She tells us about a set of protests against a garbage incinerator in Panyu district in Guangzhou, where middle class, well educated citizens challenged the incinerator and managed to get the incinerator moved to another district.

Professor Li’s work focuses on the narrative these activists created. The government advanced the idea that there were zero risks associated with this garbage incinerator. The debate focused on questions of risk and balancing this risk with rewards. She references the “risk society” theory, proposed by sociologist Ulrich Beck. In this theory, we accept the idea that living in a society has some risks. Humans develop tools to survive in a risky society, including the ability to rationally assess risks involved with our behaviors. For instance, we rely on expert opinion to evaluate the level of risk we are taking in consuming a product or taking an action. Experts and scientists, however, always have controversies and disagreements. We may rely on experts, but we will still have risks based on the disagreements between these experts.

In risk society, we are always involved with self-reflection. Beck notes that people in a risky society are always interested in these risks and in the debates between experts. The Chinese government has started listening to professionals and experts, and introduced into political debate the idea of risk management. However, this idea of risk management is still very new to Chinese government thinking, and decisionmaking is very heavily influenced by stakeholders, like the businesses or projects regulated.

Professor Li’s work looks at whether mass media in China takes seriously its role as helping audiences understand and navigate risk. She studied Southern Metropolis and News Express, two papers she saw as very representative of Chinese mass media. She considered a three month period where local residents and policymakers were most active in discussing this issue. The texts considered include about 100 reports in each paper, which suggests intense coverage.

The main conflict is the conflict over a right to have a voice in the policy-making process. The government claimed that the incinerator is zero-risk, relying on expert reviews and assertions that the technology is highly advanced and offered no risk of exposure to dioxin. Both sides drew on experts, but the government shifted to a reliance on social policy experts, using a policy rationale of “reasonable” balance.

The government tried to constrain who could participate in the debate, limiting participation to those who lived within 3km of the proposed plant… though citizens argued that people more than 3km away from the plant would be able to smell the odor of the garbage. People who lived near another plant talked about problems with odor, with water pollution and increased cancer list, relying on their personal experience to challenge expert narratives. This argument became known as “experienced rationality”, arguments rooted in local knowledge of conditions on the ground.

Media tended to focus on frame of “procedural justice”, a question of whether the government had followed proper procedures in acquiring land, getting perspectives of local residents, etc. Eventually, the media came to a conspiracy frame, considering the interests of the companies in building the plant as a way of structuring the narrative about the incinerator. An internet story revealed a close relationship between the owner of the proposed plant and the local environmental regulators, suggesting collusion to make this plant possible. This framework of interest, the idea of “what’s the real reason” behind the plant, became a compelling narrative.

A discussion that was originally about risk and expert opinion turned into a discourse about conspiracy, a narrative that moved from low-risk into a deeply risky space, where wealthy and powerful people are able to ignore societal considerations of risk. The analysis is significant because it’s a place where media has been able to challenge ideas of risk and government narratives about expertise.

I asked Professor Li what ultimately happened to the incinerator – it ended up in another community, which also protested, but less successfully. I asked whether the community where it ended up was a poorer community. It was, but Professor Li urged me not to conclude that the outcome was purely about the government selecting a poorer neigborhood – it was in part about moving to a more viable dialog about risk, not just a dialog about “zero risk”.

Sasha Costanza Chock at Sun Yat Sen University

Friend and colleague Sasha Costanza-Chock leads off the morning at Sun Yat Sen University’s conference on Civic Media with a talk titled, “Transmedia Organizing: Social Media Practices in Occupy Wall Street and the Immigrant Rights Movement”. Sasha begins with his personal journey towards a scholar of activism. He started his story with his work as an electronic musician in Boston as a student at Harvard, working to create multiracial and multicultural spaces around electronic music as a way of addressing some of the long-term cultural divides in Boston. That work led him to work on film audio for the Independent Media Center and work with Indymedia, documenting

This work on filmmaking turned into an investigation of distribution methods, which led him to work with the Transmission Network, a group focused on bringing independent media from around the world, especially to Southeast Asia to global audiences. He moved on to UPenn Annenberg, where he focused on media policy and went on to work with Free Press, an international NGO focused on participatory interventions into media policy.

Pursuing his PhD at USC Annenberg, Sasha found himself working with the immigrant rights community, a key community in LA, which has a massive immigrant population. His work with immigrant groups led to the Mobile Voices project, which has gone on to become vojo.co. This platform, which allows people to share their stories via mobile phones, is an example of a tool for transmedia activism, activism that uses a variety of media tools to seek change.

Sasha suggests that a broad view of media ecology suggests we take the new affordances of digital media seriously. Social movements have always used new media to express their identity and articulate their issues. But we need to look beyond tools and platforms, and consider the political economy of media systems. What companies are involved with these new spaces, how are they regulated, who benefits from these new systems? What are the new affordances of these tools? Who has access to tools and skills in these new spaces?

We are seeing the emergence of read/write/execute media literacies – the ability to consume media, to produce it and to lead from media to action. Those skills are distributed unequally – existing axes of inequality around race, gender, sexuality and geography influence those literacies. Norms matter as well: a conversation yesterday about WeChat and Weibo suggested that WeChat may be more private because the norm is that you follow everyone on Weibo, but you can be highly selective about who you follow on Weibo.

Transmedia organizing is build on the proliferation of participatory media practices. Social media movement practices make the most of the new media ecology, but they also understand the importance of visibility in new media spaces. Smart social movement activists are very intentional about making media through participatory tools, but reaching audiences through mass media. Transmedia organizing is participatory, cross-platform and looks for paths to action from the media produced.

Sasha asks who in the audience has heard of the Occupy movement – most of the audience has. He explains that Occupy is rooted in rising inequality, and the breakdown of a social bargain where advanced economies agreed that they would take money from wealthy firms and give that money to the general public through social services. Political developments in the 1990s, and austerity have challenged that bargain. And Sasha places Occupy within a global set of uprisings, led by the Arab Spring.

Working with the Occupy Research network, Sasha studied the media practices of the Occupy movement. He shows us the Media Tent at Occupy Boston, where tools and skills were shared by members of the Occupy media working group. This method precedes Occupy – he shows us an Indymedia center from 2002, which looks a lot like the Occupy Boston center, only with much larger computers.

Movements like Occupy often feature new media practices. Video streaming was a key way of documenting Occupy. The Global Revolution livestream had up to 80,000 viewers watching during key moments of the protests, including the clearance of the Wall Street encampment. Again, this practice isn’t unique to Occupy, but the movement made it especially visible as a way of acting as a check to power. As far back as the 1980s, networks like Deep Dish TV would produce live satellite feeds from a movement perspective, documenting major social actions.

The Occupy movement also got involved with producing new tools. Sasha points us to Occupy.Net, a collection of free software tools useful for activists. Activists produced mobile aps, films, as well as a wide variety of news coverage. Tools like PageOneX help us see how this media may have impacted mainstream media and helped change agendas on the front page of newspapers.

A survey of Occupiers reached over 5000 respondents. One of the questions asked was what media Occupiers turned to for information about the movement. The most important form of communication for the movement was word of mouth – this shouldn’t surprise anyone who’s done work on social movements. We can win small, short-term victories through digital media, Sasha tells us, but deep, long-term victories require face to face communication.

As a second case study, Sasha turns to the immigrant population in the US, particularly low-wage, working class immigrants. In the US, these immigrants primarily come from Mexico and Central America. In the US, roughly 10-12 million people are in the country without papers. There’s a virulent anti-immigrant backlash from the right that characterizes Latinos as non-American, whether or not they have documentation. Sasha notes that, while the Obama administration is seen as being left-leaning, the Obama administration has been worse for immigrants than previous administrations, arresting approximately 300,000 people per year.

Sasha considers “Secure Communities”, a national program that’s trying to compel local police forces to focus on arresting illegal immigrants. Local police forces don’t like this, as it pulls them away from law enforcement duties, and from building relationships with their local immigrant communities.

The good news: there’s a movement that’s starting to gain real traction in the US. We’re seeing meaningful legislation that would move us towards a more fair immigration system, starting with the DREAM act, which creates a path to citizenship for immigrants brought to the US as young children. While the administration continues arresting many immigrants, there’s a policy that has asked law enforcement not to deport young people who might be affected by the DREAM Act.

Anglo mass media is hostile or indifferent to these immigrant communities, and they are largely invisible to the Anglo blogosphere. But they have a great deal of power in Spanish-language media outlets, and they are having more visibility in social media. Some media has been actively hostile towards immigrants, like Fox News, which suggests mass arrests at pro-immigrant rallies. But there’s a change in the space – TIME magazine put Jose Antonio Vargas, a Pulitzer-winning journalist who is also undocumented, on the cover of their magazine as an act of “coming out” as undocumented.

Social media is important to immigrant activists in part because it’s a path to speak with mainstream media – activists report that they get much better responses by tweeting to journalists than in sending press releases. DREAM activists have a wide range of media practices. They borrow strategies from the GLBT movement, like “coming out”, showing that many people share an identity. This strategy has won major victories in the US, including rights to marriage and to military service. Undocumented youth are also using strategies from the civil rights movement, documenting their actions via video and live streaming. They use tactics like sit-ins, both in Senator’s offices and in Obama campaign offices, as a way of pressuring the Obama campaign to create an administrative order to prevent deportation of child arrivals.

DREAM activists also created new tools, although it’s less of a hacker-enabled movement than Occupy. A tool called “Own the Dream” helped undocumented people build a tool to register for protection against deportation. They conduct research and trainings to work with the press to tell their stories. Their strategies are explicitly cross-platform: rallies and events are designed to gain television coverage, and the coverage is then shared via social media. “Story-based organizing” begins from the idea of creating a winnable narrative for their activism. Activists reacted to stories about being personally blameless (we were brought to the US by our parents, so it wasn’t our fault) by recognizing that this narrative shifted blame to their parents. They shifted to a narrative about their parents taking brave action to bring their children to a land where they had more opportunity, looking for a path to citizenship for their parents as well.

Sasha leaves us with key points and questions:

- Successful movements organize across media platforms. They consider community media, traditional print and broadcast as well as new media.

- Movements are participatory and self-documenting. They don’t rely on a single storyteller. Movement advocates need to move from “speaking for the voiceless” to amplifying voices

- Social movements need to think about explicit paths of engagement. Occupy generated a lot of attention, but may have failed to provide paths towards policy shifts, connecting to levers of political power

He closes with these questions:

How do we transform attention to meaningful action?

How do we balance participatory media with narrative power? – professionally produced media might have more narrative power than individual voices working at low production values

How do remain accountable to the base of these social movements?

Civic Media at Sun Yat Sen U: Jing Wang and NGO 2.0

Professor Jing Wang is the organizer of our international symposium at Sun Yat Sen University. She’s the founder of a project called NGO2.0, which teaches participatory and social media tools to grassroots NGOs in China, helping them advertise themselves to the outside world.

Jing opens her talk by examining her personal motives for focusing on strengthening NGOs in the “hinterlands” of China, the western and central provinces. She shows a photo of herself in the mid-1950s, as a kindergartner in Taipei. Her family retreated to Taiwan with Chang Kai-Shek’s government in exile. Hoping to give her and her brother as many advantages as possible, Jing’s parents sent their children to a newly built private school. She and her brother stayed for seven years, which sound like they were pretty hellish. She was in the same class with sons and daughters of nationalist generals, mainstream media moguls and, in general, the children of the cultural and political elite of the nationalists.

“As a little girl, I understood the meaning of social class.” The other students – and the school administrators – bullied and ostracized the less wealthy children. One girl came in for particular humiliation – she was the granddaughter of an activist and critic of the Chang Kai-Shek government, and when her grandfather was arrested for treason, she was ordered to be ostracized from her peers at school.

“That emotion remained with me for years after I left the school. It wasn’t until I was in graduate school at the University of Massachusetts that I was able to name that feeling: ‘Opression’.” Jing tells us, “To this day, my favorite films are martial arts films.” As those of us who interact with her know, her online avatar is a sword-carrying warrior.

In 2006, Jing was deeply involved with launching Creative Commons in China. At the launch of the CC license for China, Larry Lessig attended, and celebrated the idea that 1.3 billion new users could now license their content freely. Jing realized that Creative Commons, as a project, has a blind spot about digital literacy – CC needed to think beyond digitally sophisticated users, and how to help the digitally challenged have their voices hear.

NGO2.0 was born in response to this second question. There was a boom in the forming of NGOs in China in 2008 in reaction to the Sichan earthquake. These nonprofits face a lot of serious problems. The government is not very interested in investing in non-government led civic participation. Most of these organizations don’t actually have legal status – their existence is in a legal grey area. And it’s very difficult for NGOs to compete with “GONGOs”, government-founded NGOs.

While NGO2.0 focuses on the least wealthy provinces in China, those in the Center and West, there’s less of an access divide than you might expect. A village to village universal service program brought internet connectivity to 98% of small townships by 2010. What’s missing was the knowledge of how to navigate online. NGOs in these areas needed extensive training in social media if they were to use new media to reach audiences.

NGO2.0 is run by a twelve person virtual team which meets for three hours each Sunday night. This distributed team has produced a huge range of outputs. Their partner organizations have recorded three minute promotional videos to share their work with public audiences. There’s an online and offline set of social media trainings, including a series of training workshops, a field guide to software and an online survey of NGO internet usage and behavioral patterns.

The field guide takes the form of a technology field map. NGOs have a wide variety of technical needs, including the ability to send out mass emails. NGO2.0 has evaluated 160 tools useful to NGOs. The database includes information on who’s developing the tool, whether they are domestic or overseas, which can be a key issue for product support. That database both informs existing NGOs on what tools they might use, and helps provide a backdrop for future tech and NGO collaborations and hackathons, helping hackers who are anxious to create tech but who don’t always know what NGOs need.

NGO2.0 is now building around the idea of city-based NGO2.0 networks. NGOs in the same city are able to reach out to each other for help and for information. And these city-based networks allow NGOs to reach out to the local commercial sector, finding businesses who might be interested in supporting these grassroots organizations. The importance of reaching out to corporate sponsors stems from the fact that the culture of personal philanthropy slow to grow in China.

Traditionally, corporations only give to large and established NGOs. But there was a scandal recently where a woman who identified herself as the general manager of Red Cross China flaunted her expensive lifestyle online, creating a crisis in confidence in these large NGOs. As a result, there’s a new opportunity for these small NGOs to approach large donors.

NGO2.0 initially tried to match NGOs and donors through a map, allowing donors to see what NGOs were located in their communities. But they’ve discovered they need to run a set of fora involving local government, local media, local corporations, and local NGOs. Jing explains that you need to invite the government because media follow government, and corporations follow media.

She closes her talk with a portrait of six NGO workers including Ma Junhe, who fights desertification through tree-planting in Minching; Qi Yongjin, who works as a barefoot doctor for the poor; and Gao Qiang, a former drug addict and advocate for welfare of AIDS patients.

Professors Zhou Runan and Wang Qing are also working with China’s NGO community. They jointly ran a course of codesign, matching design and computer science students with local NGOs to work in tandem to create new technology that meets their organizational needs. We close the day hearing from five teams of students. They show a new website produced for PFLAG China, a mobile phone application designed to document bicycling routes in Guangzhou, and a video-based training program that helps migrant workers understand their rights.

The co-design course is based on Sasha Costanza-Chock’s class on codesign, offered annually at MIT as part of the Center for Civic Media. It’s awesome to see Sasha’s hard work turn into inspiration for an important course taught at Sun Yat Sen, which is inspiring some very impressive students.

Civic Media at Sun Yat Sen U: Chinese social media innovation

Dean Ran Yang of Sun Yat Sen University’s new school of Mobile Information Engineering starts her talk by showing pictures of Zuckerberg, Jack Dorsey, Seve Chen, Sergey Brin – she argues that these guys are software engineers as well as CEOs, and that for Chinese students to succeed, they need to know how to create innovative mobile tech.

They’ve got a good record so far. Sina Weibo is the world’s leading microblogging service, founded in August 2009, and reporting 503 million users in December 2012 – on the average day, 100 million messages are posted online. We Chat was released in January 2011 and now has 300 million users. We Chat includes a number of features that are unique to the platform – “shake”, “look around” and “drift bottle” are all designed to introduce people to other mobile users.

She tells us about Cloud Newspapers, a new technology released in May 2012, which combines paper media and video media through image search. A traditional paper posts a picture of an event, and Cloud Newspapers encourage people to search for other images and videos online, building on that initial post to create a richer multimedia experience. (Conveniently, it’s also a new platform for advertising.)

The new school accepts the conventional wisdom that mobile internet is growing much more quickly than fixed internet, and that the future is in the mobile. The school will focus on four areas: mobile application development, the internet of things, mobile health and vehiculear intelligence.

The curiculum of the school will combine software engineering, computer engineering, harware engineering and communications engineering. Students will get a strong background in those four fields, and focus heavily on learning by doing, with one TA supervising a dozen students through engineering and design projects. In addition to classroom training, there’s a wide set of clubs (Android development, game development) and peer learning structures designed to support academic development and learning.

I asked Dean Yang about the challenge of innovating for markets beyond China. I’ve been using WeChat while here in China, and it’s a pretty damned cool platform – text chat, asynchronous voice messaging, photo sharing, as well as some features I’ve not seen before, like the ability to connect with a random user (shake) or a nearby user (look around). Dean Yang was surprised to learn that Weibo is more full-featured than Twitter, and I get the sense that the community here is still thinking of itself as catching up with the US, even in cases where local software development is opening some new directions.

Civic Media at Sun Yat Sen U: Mobiles, ads and games

Eric Klopfer is a professor at MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, and teaches in MIT’s Comparative Media Studies department. His presentation at Sun Yat Sen University focuses on his key reserach focus: mobile learning games. he’s aiming for a type of educational game that moves beyond rewarding players for answering a quiz question with gameplay. This means moving beyond casual games, which largely serve as a distraction from daily life, towards games that aim at enhancing your experience of the outside world and environment.

Some of Klopfer’s games are casual games that are designed to enhance a classroom experience. Students might play a gae with a biology theme, then discuss the content of the game later in the class. But much of Eric’s work focuses on augmented reality games, adding a game layer to a city or a campus. These games are designed to let people to look at the real world as well as looking at the phone, to encourage people to interact with each other.