Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 19

July 31, 2014

Free Zone 9 Bloggers

Once upon a time, there was a blog.

It was written in Amharic, the dominant language in Ethiopia, by a team of young journalists and thinkers who wanted to have an open, public conversation about the future of their nation.

[image error]

Pictures of some of the Zone 9 bloggers

It’s not especially easy to talk about these issues in Ethiopia. Africa’s second largest country has been ruled by a neo-marxist government (EPRDF – Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democracy Front) which overthrew a brutal military dictatorship in 1991, instilling one-party autocratic rule in its place.

Part of EPRDF’s strategy of control is the silencing of dissent. When students protested rigged elections in 2005, the government blocked all SMS traffic for two years, claiming that opposition activists were using SMS to plan their campaigns. (They were. The real issue is that Ethiopia saw opposition political activity as a threat to regime stability.) Ethiopia briefly had a thriving and energetic blogosphere, but government censorship and harassment of bloggers quickly silenced many of those voices. The country’s independent press has been crippled by Ethiopia’s strategy of imprisoning the strongest journalistic voices, including PEN prizewinner Eskinder Nega, in the country’s notorious Kaliti Prison.

Tens of thousands are held in Kaliti prison, in the outskirts of Addis Ababa. Journalists and other political prisoners are held in Zone 8 of the prison, and they jokingly refer to the rest of the nation, itself in a prison of sorts, as “Zone 9″. Thus the name of the blog: the Zone 9 bloggers are writing from the outer ring of the prison, the nation itself.

Zone 9 member Endalk explains:

In the suburbs of Addis Ababa, there is a large prison called Kality where many political prisoners are currently being held, among them journalists Eskinder Nega and Reeyot Alemu. The journalists have told us a lot about the prison and its appalling conditions. Kality is divided into eight different zones, the last of which — Zone Eight — is dedicated to journalists, human right activists and dissidents.

When we came together, we decided to create a blog for the proverbial prison in which all Ethiopians live: this is Zone Nine.

Ethiopia sees itself in danger of splitting into rival, warring parts. This fear is not unfounded – Eritrea broke away from Ethiopia in 1991 after a thirty-year war, taking Ethiopia’s seacoast with it. (Sadly, Eritrea is also a one-party state notorious for jailing journalists.) Ethnic Somalis in the Ogaden region and ethnic Oromo have been seeking independent states – their armed movements, the ODLF and the OLF are seen as terrorist organizations by the Ethiopian government.

The Ethiopian government does face a real threat from armed militants. But it has a disturbing tendency to label anyone who expresses dissent as a terrorist. Consider Eskinder Nega. Nega’s crime was to report on the Arab Spring protests and to point out that Ethiopia could face similar protests if the government did not reform and open up. He was charged with “planning, preparation, conspiracy, incitement and attempt” of terrorist acts and is now serving an 18 year prison sentence.

The Zone 9 bloggers were understandably scared by Nega’s arrest and prosecution, and the blog went silent for over a year. This spring, they decided they could not remain silent any longer. On April 25th, the government responded by arresting 6 members of the blogging team, and three journalists the government saw as “affiliated” with the bloggers.

The charges against the bloggers give a sense of what the Ethiopian government is fighting: dissent, not terror. Much of the charge sheet focuses on accusations that bloggers traveled out of the country to receive training in encrypting their communications, specifically through using Security in a Box, a package of Open Source software compiled by Tactical Tech, an organization that helps free speech and journalistic organizations protect themselves from surveillance. The Ethiopian government accuses the Zone 9 bloggers of using these tools in an attempt to “overthrow, modify or suspend the Federal or State Constitution; or by violence, threats, or conspiracy.” In fact, the bloggers were using such tools to coordinate their reporting work, hoping to avoid detection and arrest by a paranoid government.

These charges give a sense for how hard it is to work on free speech issues in repressive countries. Global Voices worked with Zone 9 in 2012 to create the Amharic edition of Global Voices. (That edition hasn’t been updated recently due to the imprisonment of our partners.) Four of the bloggers held in Kaliti are Global Voices volunteers. Other members of the team who work with Global Voices are in exile and would be arrested if they returned home. Knowing how dangerous it is to report from Ethiopia, we helped our volunteers find resources like Security in a Box. Our attempts to help create a safer environment for free speech in Ethiopia are now part of the case against our friends.

Obama and Zenawi share a laugh

Compounding the sadness and frustration we at Global Voices are feeling is the fact that Ethiopia is a massive recipient of foreign aid, hosts the headquarters of the African Union and is a key military ally to the US, seen as a stable, Christian bulwark against Somalia. Meles Zenawi enjoyed a warm relationship with the Obama administration (the President’s statement on Zenawi’s death included a cursory mention of human rights after praising Zenawi’s focus on food security), and there’s been little evidence that the State Department has any plans of getting tough with Ethiopia on issues of free speech or human rights.

At Global Voices, we are trying to call attention to the plight of the Zone 9 bloggers, hoping for action from the US State Department to seek their immediate release, and an easing of Ethiopia’s war on independent media. We are asking friends to join in using the #FreeZone9Bloggers hashtag, and to direct tweets to @StateDept.

This is a hard time to call attention to this situation, we know. Ellery Biddle, writing for Global Voices, notes that her Twitter client autofills the hashtag #Free____ with half a dozen choices, many of them our community members. It’s an appropriate time to tweet the State Department to demand Israel protect the safety of civilians in Gaza, or to demand that news media cover the ongoing catastrophe in Syria. In asking for help, I don’t want to lessen anyone’s outrage about other injustice, but to ask for help bringing visibility to the plight of our friends who are otherwise likely to be forgotten in international diplomatic circles.

July 18, 2014

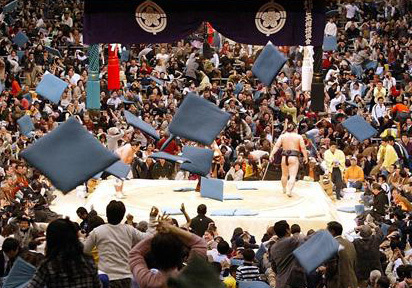

Egyptian sumo wrestler bests a grand champion. Twice. While fasting for Ramadan.

My regular readers know that I’m a fan of sumo, and am especially interested in the globalization of the sport. The top three rikishi (wrestlers) in Japanese sumo are from Mongolia, and top ranks of the sport have recently featured competitors from Bulgaria, Georgia, Russia, Estonia and Brazil. On the one hand, this is helping a distinctly Japanese tradition gain global audiences, which is a great thing for the quality of the sport. On the other hand, the globalization is in part due to waning interest in the sport by Japanese youth (few of whom are excited about living the highly-regimented life of the sumo wrestler), and globalization may be contributing to waning interest in Japan, as it has been many years since a Japanese rikishi was the top competitor in the sport. (If this topic is interesting to you, you might enjoy a ten minute talk I gave on the subject to Microsoft Research in January 2013, available as video or as my notes.

This is the first week of the Nagoya basho, one of six two-week tournaments that are the heart of the Japanese sumo season, and much of the big news is about a foreign competitor who has recently joined the sport. Abdelrahman Shalan, who competes in sumo as Osunaarashi (which translates as “the great sandstorm”), is a 138kg, 22-year old Egyptian, who is the first Arab, the first African and the first Muslim to compete at the top level of sumo. Osunaarashi came to Japan in August 2011 to compete, and has moved through the ranks very quickly, competing for less than two years at the lower levels of the sport before joining the highest level of competition (maegashira) this past November.

Osunaarashi defeats Harumafuji!

This week, he’s making headlines not for his origins, but for his performance. Yesterday and today, Osunaarashi scored back to back kinboshi, victories of a lower ranked wrestler over a yokozuna, or grand champion. In other words, yesterday and today, Osunaarashi fought the very best guys in the sport and won. It’s worth mentioning that these two matches were the first time Osunaarashi had ever faced yokozuna, which makes the achievement even more impressive.

Kinboshi are relatively rare in sumo. The term means “gold star”, and it refers to the fact that sumo victories and losses are traditionally tallied with white stars for wins and black stars for losses. A gold star signifies a particularly important win. These victories are so rare because yokozuna don’t lose very often – Hakuho, the most senior yokozuna, finishes most tournaments 13-2, 14-1 or a perfect 15-0… and those few losses are usually to other yokozuna or other high-ranked wrestlers (ozeki, komusubi, sekiwake). For an “ordinary” rikishi (i.e., a guy who’s competing in the top league, but hasn’t yet earned a particular rank) to beat a yokozuna is a significant enough achievement that fans usually respond by grabbing the cushions they are sitting on and throwing them into the air. The rikishi is rewarded with a modest, but significant, raise in pay, and the lists of rikishi who have accomplished kinboshi are relatively short and filled with sumo superstars. (Only 9 active competitors have 2 or more kinboshi.)

If you weren’t impressed by the fact that Osunaarashi beat yokozuna the first two times he faced them, leading the Japanese press to call him a “giant killer”, consider this: the man is fasting for Ramadan. Obviously, eating is an important part of sumo – one of the reasons rikishi live and train in communal houses is so they can follow a regimen of eating, sleeping and training that allows them to gain and maintain weight. But sumo training is demanding martial arts training, and in the summer in Japan, wrestlers gulp down water as they train to stay hydrated and cool. During Ramadan, Osunaarashi neither eats nor drinks during the day – in a Japanese-language interview, the head of his sumo “stable”, Otake Oyakata, explains that he hoses Osunaarashi down during workouts to keep him cool when he cannot drink water. Last year, >commentators were concerned that Osunaarashi would not be able to compete for a full 15 days while fasting – the big man went 10-5, and I’ve yet to see a news story this year that even mentions his observance.

I have enormous respect for Osunaarashi, who not only is showing himself as a magnificent athlete, but is introducing the Japanese public to the dedication, intensity and beauty of the Muslim faith. Sumo wrestlers are not just competitors, but celebrities and cultural figures. Osunaarashi is emerging as an ambassador for the Muslim world, appearing as a guest lecturer in university classes and on TV to talk about differences and similarities between Japan and Egypt, between Islam and Shintoism.

I also have great admiration for Otake Oyakata, who has broken some of the traditions of sumo to make it possible for Osunaarashi to compete. Life in the sumo beya is highly ritualized – simply giving Osunaarashi time to pray five times a day is a break from sumo routines. Rikishi eat a rich, pork-heavy stew called chankonabe to pack on weight – the Otake stable now offers a fish-based chankonabe to Osunaarashi so he can gain weight while eating halal. These sound like minor changes, but they’re a big deal for a sport that is deeply rooted in Japanese tradition and extremely slow to change. (Rikishi appear in public wearing kimono and sandals, never in western street clothes, for example.)

My friend Hiromi Onishi, a senior executive with Asahi Shinbum, and I have been bonding over our fondness for Osunaarashi and trading links about him. Hiromi theorizes that Osunaarashi’s popularity in Japan tracks the nation’s engagement with different parts of the world. In the 1980s, Hawaiian sumo wrestlers came to dominate the sport, just as Japanese tourists were beginning to travel to those destinations. As Mongolians came into the sport in the early 2000s and eastern Europeans in the later 2000s, Japan has been increasingly globalized and engaging in trade and travel to these parts of the world. Now, as Japanese hotels learn to provide halal options for Muslim travelers and show other signs of connection to the Muslim world, Osunaarashi emerges as an ambassador.

For those of you meaning to start watching sumo, it’s great to have someone to support. If you’re an African, an Arab, a Muslim, or any other kind of human being, please join me in supporting Osunaarashi. With two kinboshi, he’s likely to win the Outstanding Performance prize in this tournament, and if he keeps his winning ways up, perhaps he can defeat Hakuho as well and take down all three yokozuna. Inshallah!

Thoughtful Quora post from Sed Chapman on the history of foreign rikishi and Japan’s reactions to Osunaarashi.

Kintamayama posts footage of bashos with English title cards – an amazing resource for the sumo fan outside Japan.

July 10, 2014

Summer Reading: Dan Drezner’s Theories of International Politics and Zombies, Colson Whitehead’s Zone One

Much of my summer reading centers on the idea of civics outside of the conventional bounds of the state. I’m interested in understanding reasons why individuals and groups grow frustrated with traditional state-bound politics, and what forms of civics they explore when they opt out of engagement with the state. I’m fond of extreme cases as a way of understanding the limits of a position, so I’ve been reading about seasteading, the “dark enlightenment” movement, and prepper culture, all of which appear to me to be responses to the perception that existing states are inexorably failing.

These three forms of exit all involve a conscious renunciation of states and their accompanying services and protections. In the case of seasteading and the DE folks, this renunciation is made on an ideological basis, the belief that freedom from state tyranny (defined various ways, but usually through taxation and regulation) requires exit from political systems rather than the use of voice to influence these systems. Preppers see a collapse of existing states, either through political or natural disaster, as inevitable, and preparation to survive the collapse as prudent.

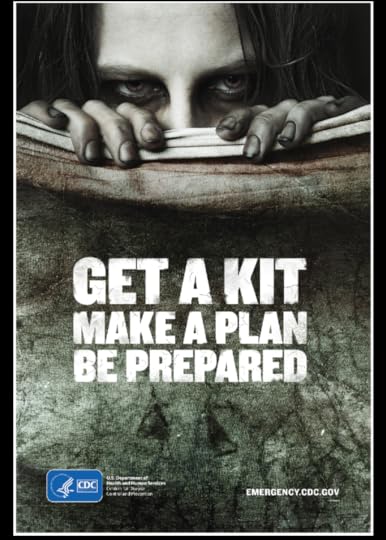

In reading about these movements, I was intrigued to see the phrase “zombie apocalypse” recur as an example of the sorts of disasters that might bring existing states to their demise. Nick Land, one of the central thinkers of the Dark Enlightenment movement, titles a section of his manifesto, “The arc of history is long, but it bends towards zombie apocalypse”, a particularly dark way of stating his reactionary historical thesis. In the prepper community, “zombie apocalypse” is a common enough shorthand for “unspecified disaster” that the US Centers for Disease Control has used Zombie Preparedness as a way to get Americans to talk about more conventional disasters they should prepare for, like tornados or floods.

But zombies are not just another natural disaster, and our anxieties about zombies are more complicated and multilayered than our fears of the implications of global warming. As John Feffer notes, our fear of zombies is a manifestation of our broader fears about globalization and pandemic, and about immigration and “the enemy within”, the post-9/11 anxiety about sleeper cells and the fears that our neighbors will turn out to be homicidally “other”. Accompanying the fears is a set of fantasies. The dream of the well-prepared survivor protecting his or her family from mindless hordes is remarkably similar whether the hordes are composed of fellow citizens less prepared for the disaster, hungry for carefully stockpiled resources, or the undead hungry for brains. The zombie apocalypse is caused when people who look like us, but are not as resourceful/prepared/strong/worthy as us, become the enemy. It’s John Galt’s nightmare, where unproductive moochers rise up to demand food, education, healthcare and eventually the very lives of the more productive and worthy citizens.

The “what’s mine is mine” stance isn’t the only possible reaction to societal collapse, including zombie apocalypse. Jeriah Bowser, who self-identifies as a prepper, has a beautiful response to this selfish view of the comping collapse. His thoughtful piece on teaching wilderness survival to preppers concludes:

I very strongly believe that, in the coming collapse, those who are able to build communities and work together – abandoning their childish, apocalyptic fantasies – will have a much better chance of survival than any Prepper I have come across. Besides, what is “survival” even worth if you are encased in a concrete bunker for years, eating MRE’s and drinking recycled piss water, living in a constant state of paranoia that someone will “take what’s yours?” Not me, I would much rather live my last days actively doing meaningful work with people I love, creating a more beautiful world than the one we left behind; a world that is based on egalitarianism for all species and types of humans, a world built on cooperation, sustainability, simplicity, and freedom. You can keep your bunkers.”)

If we want to move beyond “hide and hoard” approaches, we need to consider the role of large-scale human organization in the face of the zombie threat. While most literature on the undead focuses on individual preparedness and response, it is worth considering the ways in which the zombie apocalypse has consequences for existing states, up to and including, their collapse. Fortunately, political scientist Daniel Drezner has considered the implications of widespread zombie attack and the stresses it would create on states in his seminal “Theories of International Politics and Zombies.” Published in 2011, Drezner’s volume is not only the most comprehensive overview of likely state responses to the rise of flesh-eating formerly dead ghouls, it is also a thoughtful overview of the zombie canon (though clearly an American-centered understanding of the canon that consciously excludes the West African/Haitian view of zombies as living servants enslaved by magic or pharmacology, for example.)

Dresner explores state responses to a zombie pandemic from various philosophical points of view. Political realists, he predicts, will see zombies as a manageable fact of life in a globalized world, more threatening to weak states than to strong ones (much as communicable diseases and famines are.) Liberals will seek cooperation through international institutions and may mitigate and contain the threat of the living dead through regulation, but their insistence on open societies will complicate crisis response by forcing governments to deal with civil society, which may support zombie rights. Neocons will likely incorporate zombies into an Axis of the Evil Dead and turn a disastrous war on zombies into a war on autocrats, likely creating more zombies in the process.

Some of Dresner’s most nuanced analysis comes in the chapter on the social construction of zombies. Referencing thinkers like Alex Wendt, Dresner outlines a constructivist view of zombies based around the core idea that “zombies are what humans make of them”. Under a constructivist theory, zombie and human coexistence is both possible and desirable – the key is to escape existing paradigms that see the rise of zombies as an existential threat to human existence and to seek integration of zombies into human society, much as is accomplished at the end of Edgar Wright’s “Shaun of the Dead”.

In exploring the constructivist approach to zombies, Dresner steps up to the edge of a radical idea, then steps back. Dresner’s serious consideration of human/zombie coexistence is a brave move, though one he’s clearly uncomfortable with. In his literature review, Dresner makes clear “this project is explicitly prohuman, while Marxists and feminists would likely sympathize more with the zombies.” (p.17) In his consideration of liberal, multilateralist approaches to the zombie phenomenon, he warns that the rise of activist organizations to protect zombie rights would likely complicate or prevent global zombie eradication. (p.58-9)

Perhaps due to his inherent anthropocentrism, his suspicion of rights-based theories of politics, or the simple fact that the extant zombie literature had yet to articulate this view, Dresner is not able to consider the idea that perhaps zombification is, perhaps, a desirable next state of human existence. This radical idea is articulated by celebrated novelist Colson Whitehead, whose underappreciated contribution to the zombie canon, “Zone One”, follows a “sweeper” nicknamed Mark Spitz, tasked with clearing lower Manhattan of zombies to make the nation’s most valuable real estate inhabitable once more. “Zone One”, Manhattan below Canal Street, is one of the last safe zones in a United States transformed by zombie attacks.

(SPOILER ALERT – Stop reading here if you’re planning on reading the novel.)

While annihilation is a common theme in the zombie canon, most works focus on the transformation of society by the zombie threat. Protagonists die, but humanity survives. There are simple narrative reasons for this: it’s hard to follow a narrative when all narrators have been exterminated. In Whitehead’s apocalypse, it becomes increasingly clear that humanity cannot survive. Lower Manhattan will fall. At the close of the book, we learn that the narrator’s nickname comes from his inability to swim and fear of water, which has near-perilous consequences as he is trapped by zombies with escape possible only by diving into a stream. (As with all of Whitehead’s work, this is a comment on race in America, a reference to stereotypes of African-Americans not learning to swim.) As the novel comes to a close, waves of zombies, held back by a fragile wall, threaten to swamp Zone One and Mark Spitz realizes that it is time to learn to swim, to dive over the wall and embrace his new life as a zombie. This is suicide, the annihilation of the self, but it is also rebirth, the embrace of a new way of being in the world.

Whitehead’s radical suggestion is that we entertain the idea that it might be okay to become a zombie. That Whitehead continually confronts the idea of otherness by examining what it means to be black in a white world, may invite us to consider this idea purely as metaphor. But read literally, it’s an intriguing concept, though impossible to evaluate as the zombie is constructed as so radically other than we cannot imagine our zombified existence in anything other than cartoonish terms. (Consider how few narratives are offered from the zombie’s eye view – Jonathan Coulton’s “re: Your Brains” is one fine example, but is a reminder that the zombie perspective is so uncomfortable, it must be played for laughs, not serious consideration.)

If we read the zombie as the fear of the immigrant as other, Whitehead’s possible future merits close consideration. Some of the anxiety over the zombie invasion maps to fear of a “majority minority” nation, one where the current “default” white, Anglo-Saxon identity is merely one of many origins and backgrounds that make up a heterogenous whole. Perhaps Dresner needs to offer an update, informed by Whitehead’s addition to the canon, that considers a cosmopolitan framing of the states and zombies question. If cosmopolitanism involves recognizing the validity of other ways of living life and accepting that we may have obligations to those who live differently, perhaps it offers a framework for human/zombie coexistence, and perhaps, a richer, more varied society that recognizes the contributions and perspectives of the differently animated.

More likely, this cosmopolitan framework would rapidly lead to annihilation of human life as we know it. “As we know it” is the key phrase. The radical version of the cosmopolitan stance demands we consider the possibility that a world transformed by zombies is an optimistic future, or perhaps simply a less bleak future than one in which the main form of human existence is self-centered conflict to avoid the zombie onslaught. This is a subtext in virtually all of the zombie canon: the seven occupants of the farmhouse in Romero’s foundational Night of the Living Dead cannot cooperate or compromise, while the zombie horde at their door is remarkably coherent and peaceful, united by their desire for tasty human flesh. If we cannot unite to tackle an existential threat, perhaps we deserve our extinction. Perhaps our unity with the horde is a higher state.

This is why the zombie apocalypse analogy is such a dangerous one. If we cannot imagine a future in which we survive our encounter with the other, our likely response is to hide and hoard, to hunker down, as Robert Putnam describes, in the most extreme (and heavily armed) ways possible. Drezner does us a service in positing a world where we manage a zombie invasion much as we manage any other pandemic, and life is transformed, but still recognizable. But as soon as we posit an other – zombies, terrorists, (welfare recipients and liberals for the DE folks) – whose desire for our extinction is innate, coexistence is impossible, cooperation towards extinction of the threat fraught, and our annihilation inevitable. “A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.”

July 8, 2014

Life, only moderately messed up: understanding (my own) high-functioning depression

My wife is one of the bravest people I know.

Almost six years ago, Rachel got pregnant. When we found out, she was in Colorado and I was home in western Massachusetts, and in phone calls and emails we giddily planned for the future. Five days after discovering she was pregnant, she miscarried.

Rachel mourned the end of her pregnancy by writing, processing a set of crushing emotions into a slim volume of poetry, Through. It’s not one she often turns to when she reads in public, but women who need the book seem to find the book, and she hears often from readers for whom the book was a lifeline in a very difficult time.

Not long after, Rachel got pregnant again and gave birth to Drew. In those first weeks of the sleepless, fumbling process of learning how to parent an infant, it was hard to notice Rachel falling into postpartum depression. It was months in, when Rachel was finding it hard to do anything more that nurse and sleep, that friends and family urged her to get help. She did and she got better, producing another book of poetry in the process, Waiting to Unfold.

(When Rachel reads poems from that book, some of the darkest lines get loud laughs from the audience. The level of despair associated with acute depression is hard to understand when you’re not personally plumbing those depths – it’s easier to understand those images as jokes about the dark night of the soul rather than actual dispatches from its depths. I suspect those that really need the poems read them as written.)

In a funny way, Rachel’s bouts with depression and her profound honesty in writing about her experiences have made it harder, not easier, to write and talk about my own depression. Having someone you love go through acute depression can make it easier to see the symptoms of depression in others, but may make it harder to see moderate, high-functioning depression, which is what I appear to be prone towards.

I was depressed for most of 2013, from roughly March through December. (I’m doing much better now – thanks for asking. One way you can tell is that I’m writing about the experience, something I could not have done last year.) Much of the depression coincided with the release of my book, Rewire, which was unfortunate for two reasons. One, I did a lousy job of promoting the book, and two, smart friends counseled me that publishing a book often leads to feelings of loss and mourning, which may well be true, but isn’t the best explanation for what happened to me during those nine months.

I didn’t understand that I had been depressed last year until a natural experiment came along. Every six months, MIT’s Media Lab holds “members week”, where principal investigators open our labs to the corporate, foundation and government sponsors who fund our work. Members week in the spring and fall of 2013 was an utterly miserable experience for me. It took physical effort to haul myself out of my office and talk to the folks who’d come to discuss our work, and I was exhausted for days after from the effort. I’d decided that this was normal – MIT is a high-stress place and members week is one of the higher stress experiences at the Media Lab.

But then I went through members week this spring, which was… fun. A really great time, actually. I’m proud of the work I and my students were showing, excited to see what my colleagues were working on and excited to see friends I have at the companies and organizations that sponsor the Media Lab’s work. I got a second chance at a natural experiment with Center for Civic Media’s annual conference, which we run each June with the Knight Foundation. I remember virtually nothing of 2013′s conference, and I spent a week in bed afterwards. 2014′s conference was a good time intellectually and emotionally, and not only did I manage to feel better after the conference was over than I did on the first day, I also managed to get in a four-mile walk each day before sessions started.

Objectively, there’s a lot that’s harder in my life this spring and summer than there was in 2013 – illness in my extended family, uncertainty about financial support for my research. If mental state were purely a reflection of life circumstances, these meetings should have been harder in 2014 than in 2013. But that’s not how depression works. While depressed, everyday tasks are hard, and social tasks that challenge my introverted nature are extremely hard. They’re not impossible, just highly draining, which is why high-functioning depression is hard to see in others.

These natural experiments have forced me to think about my depression and why it’s been hard for me to see. In retrospect, I now think I’ve had several periods of significant depression since college, and twice have sought professional help. (That I’ve never been put on medication for depression is more a function of my obstinacy and ability to talk my way out of treatment than an objective evaluation of my psychological state.) As I’ve been “coming out” to myself about depression, my closest friends have offered sympathetic versions of “well, duh!”, noting that it’s been clear to them when I’m having a hard time and am not my normal self.

My guess is that my depression is significantly less visible to people who know me only professionally. I’ve never missed work or another professional obligation. I teach classes, give talks, advise students, attend meetings. The difference is almost entirely internal. When I’m my normal self, those activities are routine, easy, and leave a good bit of physical and emotional energy for creativity and expression. When I’m depressed, the everyday is a heavy lift, and there’s little space for anything else. The basic work of answering email and managing my calendar expands to fill any available time in the day. I’m far less productive, which triggers a voice that reminds me that I’m an unqualified impostor whose successes are mere happy accidents and that my inability to write a simple blog post is proof positive that I’m in the wrong place, doing the wrong thing, in need of walking away from my life as currently configured and starting over. It’s an exhausting dialog, one that crops up for moments at a time when I’m well, but can fill weeks and months when I am not.

I think what’s made it hard for me to identify my own depression is having close family and friends who’ve dealt with severe depression. What I’ve experienced isn’t anywhere as serious as what friends have gone through, including bouts of near-catatonia. The problem with having experience with the harrowing and dangerous extremes of mental illness is that the experience of being moderately messed up may not even register on the spectrum. (I’m going to use the term “moderately messed up” to describe only my own experiences, so please don’t give me any crap about the political incorrectness of the term – moderately messed up is how I best understand my experiences.)

There are cases where it’s harder to find help as someone who’s moderately messed up than someone dealing with a more acute illness. About three months into this bout with depression, I decided to give up drinking. I theorized that I might have an easier time navigating this tough patch if I wasn’t rewarding myself for getting through a hard day with a few drinks every night. Thankfully, alcoholism isn’t a forbidden topic anymore, and twelve step approaches like Alcoholics Anonymous have been tremendously effective for many people, including friends and family. (My friend Wiktor Osiatynski’s remarkable account, “Rehab”, helped me understand why many people describe AA as having saved their lives.)

But powerlessness in the face of addiction doesn’t accurately represent my situation. I came up as a “sensible drinker” on the AUDIT questionnaire and other screening tests for alcoholism. While the Denis Johnson fan in me is vaguely disappointed in my largely undebauched lifestyle, the main consequence of my drinking history is an ample beer belly.

I ended up taking a year off from drinking, with very little difficulty, and have gone back to moderate drinking and haven’t found it particularly hard to stop drinking after reaching the limit I’ve set for myself. I recognize that I am deeply fortunate, and I gratefully acknowledge that many people who have trouble with alcohol do have a disease for which abstinence and support is one appropriate response. (New research suggests that cognitive behavior therapy and harm reduction may have at least as positive results.) But it’s harder to find advice and support for the moderately messed up; detox and recovery wasn’t what I needed – I needed help changing my habits and drinking less. (Talking about this question with friends, one pointed me to Moderation Management, which might well have helped. My friend Ed Platt notes, in a thoughtful blog post, that this probably isn’t an appropriate option for people with serious alcohol problems.)

As with my drinking, I am deeply fortunate that my depression is something that’s not life threatening. But that’s allowed me to gloss over long stretches of my life when I’ve not been my best, where daily life is a heavy lift. Identifying the past year as a period of high-functioning depression hasn’t led to the miracle cure or support group, but it’s allowed me to have incredibly helpful conversations with friends who are taking proactive steps to cope with their own depressive tendencies. A dear friend, a brilliant and productive programmer, uses meditation to help him manage depressive spells. I’m finding that walking is critical to my psychological health, as is finding a way to put firmer walls around my work life. (Turns out that the upside of drinking is that makes it very hard to do academic work, forcing an end to your work day. A year without drinking helped me see how flimsy my work/life barriers are.)

So why write about depression? One set of reasons is practical, and selfish. I process by writing, and much of my processing right now centers on these issues. I write better in public than in private, and so this is likely a helpful step for me, independent of whether reading this is helpful for you in any way. And writing about depression here, on the record, makes it harder for me to delude myself the next time I find myself writing off a bout of depression as just “a rough patch.”

It’s possible that writing about depression is also the responsible and helpful thing to do. Rachel talks about her decision to open much of her spiritual and emotional life to her congregation and to her readers, acknowledging that it would be a sin of omission if her congregants didn’t know that her experience of offering prayers of healing was deeply informed by having loved ones in the hospital who she was praying for. There’s a balance, she notes, between sharing emotions and making herself a three-dimensional human for her congregants and leaning on them to shoulder her troubles. My hope is that there’s a way to write about these issues that’s less a call for support (not what I need right now) and more an invitation to talk.

So far, talking about my experiences this past year has led three friends to talk about their own struggles with depression and others to talk about anxiety, mania or other issues they are coping with. The only way these conversations have altered my friendships is to deepen them: I am more likely to turn to these friends the next time I am struggling and hope they will turn to me as well. It turns out that depression is remarkably common in the US, affecting as many as one in ten people in any given year. As Ian Gent observed, nearly everyone in academia is high-functioning. As a result, there is necessarily a large contingent of high-functioning depressives at MIT, likely including some of my students and colleagues. If I can be open and approachable on the topic, perhaps it makes it easier for people to seek me out for help at a university where stress is epidemic and sometimes celebrated. (In the first semester I taught at MIT, two colleagues told me stories of professors who ended up hospitalized for overwork. These stories weren’t offered as warnings – they were celebrations of an admired work ethic. That’s an environment that makes it hard to talk about depression or other mental health issues.)

I’m writing about depression because I can. As John Scalzi has memorably noted, “straight white male” is the lowest difficulty setting in the game of life. Add to that the fact that I’ve got a good job at an institution that is trying to do the right things on work/life balance, with a boss who’s written openly about his relationships with alcohol and other health issues, and it’s simply easier for me to write about these issues without fearing professional consequences than it is for many others. I believe that speech begets speech, and if more people are talking about working through depression, it becomes easier for the next person wrestling with these issues.

July 7, 2014

“New media, new civics?” and reactions in Policy & Internet

TweetThis past December, I gave a talk at the Oxford Internet Institute about possible relationships between “new media” and new approaches to participatory civics – I blogged my notes for the talk at the time.

The fine folks at OII asked whether I would be willing to publish the notes of the lecture in the journal Policy & Internet, edited by Vili Lehdonvirta, who had invited me to lecture at Oxford, and by Helen Margetts and Sandra Gonzalez Bailon. I agreed, and worked with the editors to polish my handwavings into something more permanent.

What I had not realized was that the editors had solicited a set of responses to the lecture from some of the smartest people in the new media, political theory and social activism space. The latest issue of P&I features my essay, as well as responses from Zeynep Tufekci, Jennifer Earl, Henry Farrell, Phil Howard, Deen Freelon and Chris Wells, who do a great job individually and collectively of challenging and expanding my thinking.

P&I, unfortunately, is protected by paywall, but I and others involved are archiving pre-press versions of our papers. Mine will be up on MIT’s DSpace repository in the near future and is here in the meantime. Other participants have been making their pieces available online as well. If you’ve got access through your university or a library, please check out the whole issue!

June 11, 2014

Town Meeting and a lesson on civic efficacy

Last night, I attended Town Meeting in Lanesborough, MA.

Town meeting government is peculiar to New England and especially strong in Massachusetts, where almost 300 of the state’s municipalities are governed by an annual meeting of town residents. My town is under the population threshold of 6000 at which towns can choose to elect representatives to town meeting. In small towns like ours, we are required to hold an open town meeting, at which any residents may speak and ask questions and where registered voters vote on any major discretionary spending and on changes to the town’s bylaws.

These aren’t the question and answer sessions with national-level elected officials that became infamous for revealing how angry and partisan many American are. They are dead practical discussions of individual line items in the annual budget of a small, mostly volunteer-run organization. (Lanesborough has three elected selectmen, who appoint a paid town manager. The selectmen are nominally compensated for their work, and most committee members are volunteers. The town’s budget of $10 million, goes almost exclusively towards salaries for teachers, school administrators, police and highway workers.) The conversations that take place aren’t the sort that play well on cable TV news – instead, they’re familiar to anyone who’s served on the board of a budget-constrained nonprofit organization.

Town meetings are frequently lauded as one of the purest forms of direct democracy. Everyone has a voice, which is a good and a bad thing – only fifteen minutes into last night’s meeting, it became clear why every meeting has a moderator and why that moderator has extremely broad discretion over closing discussion on a topic. About an hour into the meeting, I asked a question about a $10,000 expenditure on road repairs, and quickly regretted doing so. I was curious because it was the sole article on the warrant where the selectmen and finance committee were at odds, and I was interested to know what the dispute was about. Half an hour later, I knew a great deal more about the problem of runoff from unpaved roads into Pontoosuc Lake, snowplowing and the nuances of accepted, non-accepted and private roads than I’d really wanted to know.

Mark Schiek, Mount Greylock Building Committee Chairman, speaks at Lanesborough Town Meeting. Photo from iBerkshires

I was acutely aware of the time my question was taking up because, like most of the people who attended the meeting, I was there because of a single article, Article 21, slated for discussion near the end of the meeting. Lanesborough has quite high tax rates (38th statewide), even for Massachusetts, in part because we maintain our own elementary school and share a high school with larger, wealthier Williamstown. That high school has serious structural deficiencies, and there’s a plan on the table to retrofit the building or build a new facility. First step in that plan is gaining approval for a $850,000 feasibility study at the town meetings in Williamstown and Lanesborough.

Many of the people in the elementary school gym last night are parents of young children (like me) who wanted to ensure that their children’s high school remains strong. And, like me, many were paying babysitters to watch their kids so they could vote in favor of a feasibility study.

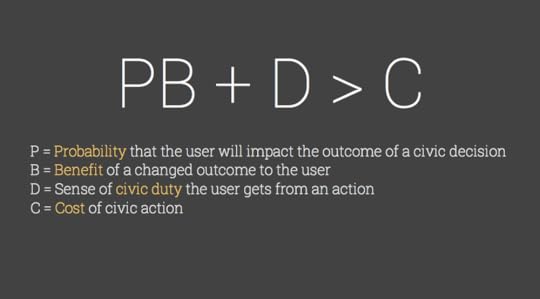

My presence at Town Meeting was a straightforward illustration of an idea Anthea Watson Strong introduced at the recent Personal Democracy Forum in New York. To explain why it’s often difficult to get people involved in civics, she offered an equation:

The benefit of renovations to our local high school is quite high for me: my son enters kindergarden in 15 months, which means he’s likely to enjoy the full benefits of a new or renovated middle and high school. Those campaigning in favor of the feasibility study persuaded me that P was pretty high, as they were expecting showdown between pro-education and anti-tax forces, and they needed every vote they could get, as this allocation requires a supermajority. Even without considering duty, P * B was high enough to overcome the substantial cost of action: three hours of a babysitter, a rushed dinner instead of a night of bad TV on the couch.

As it happens, Article 21 didn’t need my vote. Several townspeople spoke passionately about the need for strong schools, one suggesting that as Berkshire County shrinks in population, we should expect our high school to become a magnet for high performing students in nearby communities. Members of the regional school committee had good answers to probing questions about school choice, tuition for out of town students and the steps in funding a renovation process. Two townspeople spoke against the article – as it turned out, they were the only ones I saw vote against the article – well over a hundred voted for it. I misperceived P – spending time at Town Meeting seemed like an effective civic action because I anticipated showdown that didn’t actually occur. (I suspect that “perceived P” is more important than actual P – if you think your vote counts, you’re more likely to vote.)

When the Article passed, dozens of people left the meeting. I left, too – I wanted to pay my babysitter and get to bed. In the process, I illustrated precisely the problem Massachusetts communities are having with town meeting. Several communities have abandoned the meeting system of government because it’s very hard to get people to attend when there’s not a controversial issue on the table. In other words, D is very low. In my case, it’s low enough that it hasn’t moved me to attend Town Meeting in the 15 years I’ve lived in town, until an issue arose where PB > C.

That may change for me. I learned a great deal about my town by attending town meeting, details about how the water, sewers and roads work that I’ve honestly never thought about. The main thing I learned was that to participate in these meetings effectively, I’d need to do a great deal of reading ahead of time, much as I prepare for budget committee meetings for NGO boards I sit on. At that point, P would be higher (though, most of the time, I’m not sure B or D is high enough for me to stay engaged.)

These calculations about the civic utility of attending town meeting suggest some problems for those who are seeking change through government transparency. It’s hard to think of a ritual more conducive to transparency than the Town Meeting. The town publishes an annual report with a detailed, proposed budget ahead of time, and every line of the budget can be questioned by any resident. While this transparency is laudable, it’s also extremely confusing to those who don’t know the issues already. Transparency without explanation opens the process to those who have time and motivation to learn what’s at stake. The rest of us could use a good guide, something we rely on the increasingly stretched local press for. The Berkshire Eagle ran a brief story about what issues were on the table at the meeting, though no follow up about what decisions were made. (A local news site had an excellent article on the Article 21 vote.)

There’s another way of considering engagement in Town Meeting, beyond Anthea’s PB + D > C

equation. Zeynep Tufekci, reacting to a tweet I posted about Anthea’s framework, wondered whether a game theoretic equation was the best explanation for civic behavior. She suggested that most people participate in social movements because their friends are participating, or because it seemed like “the right moment”, not because of some careful calculus. That’s true for me, too. My favorite waitress at Bob’s Country Kitchen, who’s slated to be my son’s kindergarten teacher, urged me to pay attention to the school funding issue, and friends at a BBQ talked about the importance of passing Article 21. Without those nudges from my neighbors, it’s a lot less likely that I’d have left my house last night.

Much of my research on civics focuses on questions of why people don’t find it effective to engage with their governments. It was a refreshing challenge to my thinking to spend time with my local government and find it surprisingly open and responsive. At the same time, it was a reminder that many of the issues I care about – prison reform, gun control – aren’t ever going to be settled in a room as transparent and congenial as the Lanesborough Elementary School gym.

June 10, 2014

Lessons learned from walking at work

MIT’s commencement was Friday, and (despite the fact that most of my Masters students are continuing to work on their theses over the summer) my official summer began yesterday. Yes, I’m looking forward to catching up on reading, not driving into Boston and the general wonder of the Berkshires in the sunshine… but I’m most looking forward to working from my walking desk.

I have been restructuring my life around walking over the past couple of years. I’ve found that it’s the only exercise I can consistently get myself to do when I’m at home, in Cambridge or on the road. In Cambridge, I now stay in a bed and breakfast three miles away from my office, in part so I can get almost half of my daily walking goal during a 50 minute walk to work. When I travel, I try to wake up early and take hour-long walks around the city I’m staying in, which is good for combatting jetlag and for getting the lay of the land.

At home, though, I have become a reluctant treadmill user. It’s shockingly lovely where we live, and hiking is one of the very best ways to encounter the Berkshires. But home time is wife and kid time, and so I try to be efficient enough in my workdays at home that I have time to throw a ball with Drew or watch bad TV with Rachel. For the past two years, I’ve tried to schedule 1-2 hours a day of conference calls in the afternoon so I can drive to a nearby rail trail to walk and talk. (And yes, I certainly do see the irony of driving to walk. We live on a twisty mountain road where it’s just not especially safe to walk, and where it’s damned hard to carry on a conversation while trudging uphill.) When it’s too cold or rainy to walk outside, I’d tried a new trick – walking on the treadmill after Rachel went to bed, watching old episodes of LOST.

Rachel started using that treadmill – a noisy hand-me-down from friends – to walk while “syncing” in the morning (checking email, social media, etc.) and found that taking half an hour in the morning to do so made her happier for the rest of the day. I tried it and decided that, while I could sync and walk, I needed a desk for real work and a treadmill that was dramatically quieter if I was going to use it to walk and talk.

Last month, we took the plunge, and bought Lifespan’s TR-1200, which seems to be the entry-level walking desk treadmill of choice. (Lifespan makes cheaper treadmills, but this one is rated for several hours of use per day, and with the two of us sharing, it seemed a better option than the cheapest model.) Because Rachel and I are close in height, I was able to build in a desk that’s comfortable for both of us. I bought a new 27″ LCD monitor and a swing arm, repurposed an old desktop speaker set, and bought a remote control fan to mount on a ceiling beam behind the treadmill.

For the past month, we’ve each been using the desk about an hour a day when we’re in town. This week, working from home, I’m putting in closer to 3 hours each day and starting to get a sense for how the new setup does and doesn’t work for me. Some lessons learned:

- The right treadmill matters. I love the guys at Instructables, and I think their advice to “just do it” and build a walking desk around an existing treadmill is conceptually sound, but not practically possible for me. If you can comfortably hold a conference call on your existing treadmill, perhaps then this is a good idea. My hand-me-down treadmill squealed like a stuck pig, and the first step in moving to a standing desk was taking the plunge and making the purchase of the Lifespan treadmill.

- You don’t have to go all in. I’m not an absolutist. Some of the folks who write about switching to treadmill desks encourage you to go all in, moving your full office setup to the treadmill desk. As a road warrior, I don’t have a particularly robust desktop set up at home – I work outside under an umbrella if it’s nice, in front of the fire if it’s cold. The treadmill desk has become another locus for work, but I doubt it will ever become my only workplace.

- Match the task to the workplace. The desk is magical when I’m on conference calls. I can walk at 2.5 – 3mph and no one seems to notice. I get the occasional comment when on Skype or Google Hangout, as my head does bounce up and down, but no one has groused yet. (One Kenyan caller was surprised that he was reaching me at the gym, but that may have had as much to do with how I was dressed as my walking motion.) And, like Rachel, I find that checking email and social media is perfectly reasonable at 2 mph, though I sometimes slow to 1.5 mph to reply. Thus far, I wouldn’t move major writing, programming or reading onto the treadmill… and, for better or worse, I usually have enough conference calls and email to give me 2-3 hours on the treadmill, which is enough to get my 15,000 steps a day.

- Walking is great for combatting distraction. The tasks that work best on the treadmill for me are ones where I don’t need my full focus. When I sit at my desk during conference calls, I don’t pay close enough attention because I end up reading news in another tab. Walking seems to lessen the need to multitask. It may be that I know I’m doing something good for myself physically, or it might be that the little bit of effort it takes to keep the legs moving forward and keep the hands on the keyboard means I have less cognitive surplus to deal with. Amy Harmon, writing in the New York Times, speculates about this as well, pointing to a study by the Max Planck institute in which children and young adults performed better cognitively when walking at their preferred pace.

The moments where I notice this the most are when I’m answering email I don’t want to answer. At a desk, I flit from tab to tab, reading this, tweeting that. At the walking desk, I seem to be able to focus better, perhaps because I know I’m going to use the walking time as email time, then sit down to concentrate on something more engaging.

- Don’t be an idiot. There have been several posts questioning whether it’s possible to work efficiently while walking. This one, by Alyson Shontell, titled “The Truth About ‘Working’ On A Treadmill Desk, makes the experience sound like training for a marathon. At the end, she reveals that she wasn’t so much testing the walking desk as a work choice, but competing with a fellow Business Insider reporter who’d walked 17 miles the day before. I’m finishing this post on the treadmill, having walked 6 miles over 3 hours today, and that’s more than enough for me. Getting in an hour’s walk a day would be a good change for most people, while spending 8 hours walking probably isn’t good for anyone’s productivity.

I realize that hearing other people talk about their work and exercise regimes is roughly as interesting as hearing them talk about their dreams, but the walking desk really is one of the more exciting things in my life right now, and I’m not able to resist evangelizing.

May 30, 2014

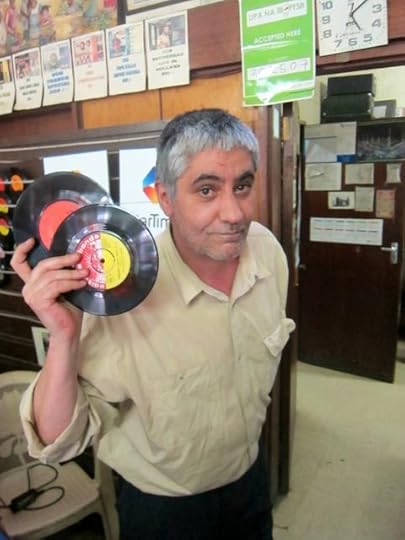

Melodica Music: stepping back in time in downtown Nairobi

I would be sad to return to the pre-internet days of music fandom. I think back to the days of paper fanzines with hazy nostalgia, but in truth, it was pretty wretched to hear about a band you might or might not like, order a 7″, wait weeks and discover that just because some dude with an exacto knife, glue stick and access to a xerox machine loved a band, it didn’t mean they were any good. I try to remember to be thankful every time I look up an unfamiliar band on AllMusic.com, when I surf a band’s back catalog on YouTube and buy CDs I would never have found without online retailers who stock the long tail of musical tastes.

That said, one casualty of the digital age is the demise of the local record store. I am blessed with an excellent local record store, Toonerville Trolley Records in Williamstown, MA, and I was thrilled to see a line of patrons waiting to get in to celebrate Record Store Day a few months back. (I took Drew to buy his first LP. Four and a half seems like the right age to start building a record collection.) But despite how fortunate I am in terms of local record shopping (both in Williamstown and in Cambridge, which has great stores like Weirdo and Armageddon), I feel the loss of the institution of the record store when I travel to different cities.

This past week, I was in Nairobi, Kenya, with Media Lab students, staff and faculty, working to build a partnership between the Lab and iHub, the remarkable tech incubator and coworking space built by the founders of Ushahidi. I wanted to make sure my Media Lab friends saw Nairobi for the wonderful, exciting city that it is, and I especially wanted to show Joseph Paradiso, the other lab faculty member on the trip, some different sides of the city. Joe is a celebrated builder of analog synthesizers and a massive prog rock fan, and while I knew finding music to suit his tastes in Nairobi might be a challenge, I figured a visit to a record store was in order.

Johnstone Mukabi and Peter Rugenye perform at the Melodica Music Store in Nairobi.

Visiting Melodica Records in Nairobi is as much pilgrimage as shopping excursion. The proprietor, Abdul Karim, has been managing the store since 1971. Located in Nairobi’s Central Business District, Melodica is part musical instrument shop, part performance space and part archive. It was quiet on the Saturday afternoon we came by, staffed by Karim, his mother and an assistant, and we were the only customers exploring the stacks.

Like many African music stores, Melodica burns CDs for customers rather than selling packaged CDs. (Teju Cole writes movingly in Every Day is For the Thief of finding John Coltrane CDs in a record store in Lagos, then discovering they are astronomically expensive to buy, as they are designed to be kept as the reference copy, parent of the copies for sale.) Joe immediately begins grilling the sales clerk, asking for the weirdest, most experimental music the shop stocks. The first track the clerk plays is Kanda Bongo Man’s “Zing Zong” – not exactly what Joe was looking for, but I recognize it immediately and shout out the title based on the opening notes. That earns me admission to the back room, packed with piles of dusty vinyl, and an invitation from Karim to use his turntable to listen and discover.

Joe asks what Congolese Rhumba bands sound the most like Can’s “Future Days”

Melodica dates from the days when African record stores weren’t just selling a product – they were recording studios, producers, distributors and retailers. Many of the records Karim hands me are ones on the Melodica label, which he produced in the 1970s. As I’m picking through a stack of dusty Luo ballads, looking for Lingala dance music, Karim explains that musicians would travel with reel to reel masters from Kinshasa or Brazzaville to Nairobi to press their work and bring it to audiences throughout central Africa.

The production on the records varies widely. Some were originally recorded badly, and the saturated tape leads to gnarly, distorted records despite Karim’s engineering efforts. Others have the wide-open, echoey sound that’s characteristic of my favorite Congolese music, a sound that somehow evokes both all-night, outdoor dance clubs and distant vistas. Karim and I talk about what types of records I like and he does his best to find records that feature organ and synth crossing into traditional song structure, the local parallels to styles like Afrojuju in Nigeria (my genre of choice.)

I note a promising album propped up on the studio window, the scratched plexiglass producers once sat behind to offer hand signals to the band recording in what’s now the store’s main space. It’s “Mandingo” by Black Blood and Karim explains that he can’t sell me the album as it is his sole remaining copy, but urges me to download tracks from it from the store’s website. Karim’s role is at least as much preservationist as proprietor these days. A search for “Black Blood” on Afro7, a site dedicated to East African vinyl, offers the clue that Black Blood was a group of expatriate Kenyans playing in Brussels, but there’s little else about them online. Karim’s copy is surely not the sole one extant, but it’s one likely to ensure that a funky, ferocious band survives another generation.

Crate-digging, the art and science of searching for rare grooves in record stories, antique shops and yard sales, is a celebrated, if controversial, practice. Classic hiphop was built on the art of the sample, and the more obscure the sample you could find, the better. (Afrika Bambaata had notoriously deep crates, and was legendary for soaking the labels off his hottest breaks and replacing them with other labels to throw rival DJs off.) After a successful lawsuit by George Clinton’s publisher, Bridgeport Music, established a precedent that any sample, identifiable or not, would merit royalty payments, mainstream hiphop moved away from the world of crate-digging… but the best DJs didn’t.

Recently, DJs like Diplo have built their reputation on finding inspiration in global dance sounds from musical cultures unfamiliar to North America and Europe. (I discuss Diplo’s work at some length in Rewire.) German DJ Frank Gossner has established himself as an “archaeologist” of African vinyl, making multiple trips throughout the region to find rare grooves he can throw into his dance sets. This practice has its critics – DJ Boima Tucker draws parallels between the search for undiscovered African vinyl to the quest by colonial powers for natural resources in Africa, while allowing that these records may simply disappear if someone doesn’t rescue them from obscurity. (A comment by Gossner on Tucker’s post gives you a sense of just how nasty these conversations can get when one DJ accuses another of colonialism…)

Visiting Melodica gives a certain perspective to the crate-digging versus preservation conversation. I didn’t exactly have to fight off an army of European and American DJs desperate to throw some vintage Congolese rumba into their sets. And Karim is hardly a naïf, unaware of the treasures in his store. Instead, he’s acutely aware that the work he’s doing to preserve the music he grew up with requires this music to find new and broader audiences.

Joe and I each buy half a dozen compilation CDs featuring 7″ singles of taraab, rhumba, and afrorock that Karim has digitized. His assistant burns the CDs for us and prints fresh covers for the CDs – it’s hard to believe the roughly $1.20 we pay for each CD pays for more than the disc and the printout. I choose four of the records I most enjoyed and Karim apologizes before charging me $6 for each, explaining that his stocks are slowly dwindling for the old vinyl.

Abdul Karim shows off the reason to come to Melodica – a wealth of historical 7-inches in the place where some were recorded and mastered.

That evening, I had dinner with some of the members of Just a Band, one of Kenya’s most exciting artistic collectives – the group includes filmmakers as well as musicians, and they are at the center of a scene that includes designers and installation artists as well. One of the filmmakers listens to my story about Melodica and says, “I’ve been meaning to do a film about that place.” I hope he will: Kenya’s music scene has a rich past and a promising future. It would be great to see the next generation honoring such a historic treasure.

Kentanzavinyl has a great database of the sorts of artists I found at Melodica, as well as a good blogroll of African record collectors, many of whom post digitized audio from their finds.

Melodica is in the Elimu Co-op House, across the street from KTDA on Tom Mboya Street. Abdul Karim is always happy when fans of east African music visit.

Special bonus tracks:

“A.I.E. A Mwana” by Black Blood

“Africans Must Unite”, by Geraldo Pino, one of the 7″ I bought at Melodica

May 21, 2014

When Being Happy is Political

The Atlantic was kind enough to run a lightly edited version of this post. I’m posting here after their publication so that this remains in my archives.

Pharrell Williams is a happy man, but he’s crying. He’s one of the most in-demand record producers in the world, and had a hand in the two hottest songs of 2013, “Get Lucky” by Daft Punk and “Blurred Lines” by Robin Thicke. While those songs were inescapable on radio and television last summer, Pharrell’s most recent hit, “Happy”, has taken a different path to prominence.

French director Yoann Lemoine and production team We Are From LA worked with Pharrell to create a unique video for “Happy”. The video is 24 hours long, and was shot all across Los Angeles, featuring dozens of celebrity cameos interspersed amongst shot after shot of people dancing happily. It took 11 days to shoot the video, though many of the shots were single takes. The video follows the course of the day in LA, with footage from dawn to dusk and through the night, with Pharrell appearing each hour.

The original “Happy” video

The video quickly spawned thousands of fan remakes, featuring workplaces, business schools, college dorms who are all happy. Faced with a viral hit, Pharrell’s label, Columbia Records/Sony Music, has turned a blind eye to possible copyright violations, and one can easily spend hours on YouTube flipping from one fanvid to the next.

There’s a special subcategory of these videos that I think of as “georemixes”. The georemix builds on the idea that the original “Happy” video is a love letter to Los Angeles, a portrait of the city’s architecture, landscapes, people and spirit, and moves the party to a new location. More than a thousand georemixes of “Happy” exist, and they portray happy people on all six continents.

Pharrell, on Oprah, crying over “Happy”

Pharrell is on Oprah, watching a compilation of these remixes that bring his song around the world, from Detroit to Dakar. In the 30 seconds of the video Oprah shows, we catch glimpses of happy Taiwanese women on a spa day, Icelanders dancing on a glacier and Londoners strutting with Big Ben in the background. Pharrell’s reaction is the one many of us have had to the remixes of his video: he cries for a long time, overwhelmed not only by his success but by the experience of watching a simple idea – film yourself being happy – as it spreads around the world.

“Happy” is not the first video that’s been georemixed. Last summer, I gave a talk at the MIT8 conference focused on remixes of PSY’s Gangnam Style and Baauer’s Harlem Shake. In researching these localized remixes, my students pointed me to Jay-Z and Alicia Keys’s “Empire State of Mind”, remixed in remarkable fashion into “Newport State of Mind”, by comics M-J Delaney, Alex Warren and Terema Wainwright. (The parody was further parodied by Welsh rappers Goldie Looking Chain, who complained that the Newport parodiers lacked local knowledge and cred.)

The original “Empire State of Mind”

“Newport (Ymerodraeth State of Mind)”

The georemix dates back at least as early as 2005, when Lazy Sunday, produced by The Lonely Island (Saturday Night Live’s Chris Parnell and Andy Samberg) was remixed into parodies like Lazy Muncie, showing midwest pride, and Lazy Ramadi, which replaces a search for cupcakes with a confrontation with Iraqi insurgents.

Lazy Munzie

Lazy Ramadi

The Lazy Sunday georemix was born out of a mock East Coast/West Coast rap beef, which quickly set the tone for georemix videos. Each response is a retelling of the core story, transposed to a new location, bragging about local landmarks and habits. While the braggadocio in these remixes is pure parody, there’s a sense in which each of these videos makes a claim to share the stage with the original. YouTube’s related videos feature means that there’s a chance that some of the 2 billion viewers of PSY’s Gangnam Style video will encounter Zigi’s “Ghana Style”, a georemix that relocates Seoul to Accra and replaces PSY’s horse dance with Ghanaian Azonto. (And if not through YouTube, viewers may encounter Zigi through the hundreds of listicles that advertise “10 Best Gangnam Style Parodies”)

Zigi’s Azonto version of Gangnam Style

I think of the georemix as a claim to attention, a way of demanding part of the spotlight that shines on a popular video. It’s a very basic demand: accept that we’re part of this phenomenon, too. In remixing Gangnam Style, Zigi sends the message that Ghana has YouTube, is clued into global cultural trends, has its own distinct sound and dance style to share with the world, and can produce videos as technically proficient as anything coming from other corners of the world. To me, “Ghana Style” reads both as lighthearted celebration of a catchy tune that truly went global, and a political statement about a world where culture can spread from South Korea to Ghana to the US, not just from the US and Europe to the rest of the world.

Of course, the georemix can also be purely political. Ai Wei Wei’s Gangnam style, titled Grass Mud Horse Style, moves the dance into his studio in Beijing and is filmed almost entirely within the walls of that compound, alluding perhaps to the artist’s frequent arrests and detentions. (If the location doesn’t set the theme, his appearance a minute into the video, spinning handcuffs certainly does.) Other georemixes take on specific issues explicitly. Consider Dig Grave Style, a protest video made by students from China’s Henan province, in which dancers rise from the earth to protest the moving of graves from villages to open land for real estate development.

Dig Grave Style

Remixing a video is a shortcut to creating original content. The script is partially written – the creativity comes from changing the lyrics and the setting. The popularity of the Harlem Shake meme (which was georemixed around the world, and saw political georemixes in Tunis and Cairo) came in part from the extremely low levels of effort required to participate in the phenomenon – simply film people behaving in an ordinary way, then dancing like madmen in strange costumes and you’ve got your localized Harlem Shake.

“Happy” benefits from this low barrier to entry. There are Happy remixes that function as shot-by-shot remakes of the short, official Pharrell video, and there are vastly more that adopt the spirit of the video and transpose it to a local context.

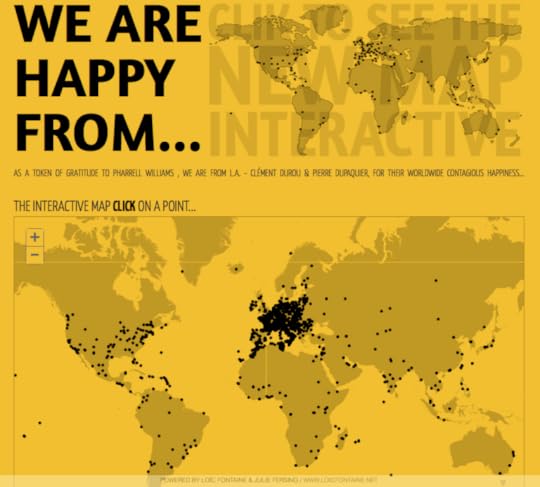

Loïc Fontaine and Julie Fersing deserve much of the credit for the georemixes that made Pharrell cry, though neither has made a video. Fersing, an interior designer in Nantes, began collecting georemixes of “Happy”, searching YouTube to find new material. When she’d located 21 of the videos, she turned to her husband, Fontaine, who’d begun a career in website development nine months earlier. Together, they launched We Are Happy From, a portal that now hosts 1682 videos from 143 countries.

We Are Happy From front page

Once the site had attracted about 50 remixes, Fontaine contacted the We Are From LA production team, who gave the project their blessing. While Fontaine had not spoken to Pharrell when I interviewed him a month ago, he felt quite confident that the project was consistent with the artist’s wishes and would survive, pointing out that Sony had not taken action to remove the vast majority of remix and parody videos posted online. Indeed, the success of the song has likely had a great deal to do with the widespread participation online, giving “Happy” an online life and prominence that no amount of radio payola could provide. (Pharrell has embraced the notion of the georemix, urging people around the world to produce their versions of the video as part of a UN-sponsored International Day of Happiness.)

We Are Happy From is simply an index, pointing to videos hosted on YouTube, Daily Motion and other platforms. While the videos have a consistent look, usually opening with a black on yellow title screen (as Pharrell’s video does), Fontaine doesn’t provide any production help or guidelines. Still, the videomakers are clearly conscious of We Are Happy From’s role in promoting “Happy” videos as a global form, as many videos feature a screencap of the We Are Happy From map.

While anyone can submit a video to We Are Happy From, not all videos appear on the map. Fersing is the curator, and she watches all videos before adding them to the map. (As of April, the couple were receiving 20-40 videos a day.) Videos that are overly commercial or connected to political or social causes don’t make the cut. Fontaine explained that some French political parties produced Happy videos as campaign materials – We Are Happy From chose not to feature those videos. An Italian version of Happy with an environmental message was also not included, nor was Porto (un)Happy, which features activists dancing through unfinished construction sites in Porto Allegre, Brazil, along with subtitles that critique government spending on public works projects. (Manaus is unhappy as well.)

I asked Fontaine why he and his wife had chosen to become active curators of the project. It was a practical decision, Fontaine explained: “They say it’s black, someone else says it’s white. How am I to judge?” Rather than evaluating the validity of political claims, he would rather focus on what he sees as the core message of these remixes: “We Are Happy From is purely about the happiness. We just want to show a simple message about being happy about where we live.”

For me, as a student of civic media, the dissident videos excluded from the We Are Happy Map are the most interesting ones. Fontaine has kindly shared the list of rejected videos with me, and I hope to spend some time this summer watching those 500 remixes in the hopes of developing an understanding of how “Happy” can work as a script for advocacy (or how videomakers think it might act as that script.) But for Fontaine and his wife, the mark of success wasn’t raising awareness for a cause or an issue – it was documenting the spread of happiness globally. When I interviewed Fontaine, he was celebrating the spread of “Happy” to Antarctica, with a video from French research station Dumont d’Urville.

The 1600 videos on We Are Happy From may not advocate for a political party or a cause, but they are “political”. When the residents of Toliara, Madagascar make their version of “Happy”, they’re making a statement that they’re part of the same media environment, part of the same culture, part of the same world as Pharrell’s LA. This assertion isn’t quite as anodyne as Disney’s “Small World After All” or the “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” campaign. Even with Fontaine and Fersing’s curation, we get distinct glimpses of how different it can be to be happy in different corners of the world: Happy in Damman, Saudi Arabia features wonderfully goofy men, but not a single woman. Beijing is happy, but profoundly crowded and hazy – intentionally or not, the video is a statement about air pollution as well as about a modern, cosmopolitan city.

A few weeks ago, We Are Happy From added a video from Tehran, Iran to the map. If you don’t know where the video is from, it’s unremarkable. A dozen twenty-somethings, men and women, dance on a rooftop, wear silly outfits, and wave their legs while lying on a bed. It’s remarkable only if you know that women in Iran are forbidden to appear in public without their hair covered and that men and women are prohibited from dancing together in public.

Happy in Tehran

Given context, the video is an incredibly brave statement. The young women in the video covered their own hair with wigs, keeping themselves technically in line with local Islamic law, and kept clothing around so they could cover up if seen from neighboring buildings. One of the videos stars, identified only as Neda, said, “We were really afraid. Whenever somebody looked out of a window or someone passed by, we ducked behind a door to make sure we were not seen.”

The makers of the video, forced to apologize on state television

Neda and her compatriots were right to be afraid. Six people involved with making the video were arrested and forced to appear on state television, testifying that they were tricked and duped into making the video. It is unclear what consequences the filmmakers will suffer beyond public humiliation, and a hashtag, #FreeHappyIranians is emerging to protest their detention. Pharrell, to his credit, has tried to call attention to the situation:

It's beyond sad these kids were arrested for trying to spread happiness http://t.co/XV1VAAJeYI

— Pharrell Williams (@Pharrell) May 21, 2014

It’s clear from Neda’s interview with Iran Wire that the intention behind the video is precisely Fontaine and Fersing’s intention. ““We wanted to tell the world that the Iranian capital is full of lively young people and change the harsh and rough image that the world sees on the news.” They chose a middle-class Tehran home to make the point that ordinary Iranians, not just the elite, were happy, creative, modern and globally engaged. And the video, with subtitles and credits in English, was clearly created for a global audience, designed to be part of the International Day of Happiness, though it was turned in too late for inclusion: “We want to tell the world that Iran is a better place than what they think it is. Despite all the pressures and limitations, young people are joyful and want to make the situation better. They know how to have fun, like the rest of the world.”