Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 22

November 13, 2013

An anniversary, a reflection

My wife, the remarkable Velveteen Rabbi, just announced her 10 year blogiversary, a decade since her first post about her journeys in spirituality, from a layperson who thought, read and spoke about liberal judaism and social change, to rabbinic student, to ordained congregational rabbi. Along the way she’s shared reflections, poetry, liturgy, scriptural interpretation, and a great deal of personal information about what she’s experiencing and wrestling with, including a miscarriage, a birth, parenthood, and her engagement with issues personal and political. It’s a remarkable document, one I congratulate her for building and maintaining, and urge others to read.

When Rachel tweeted that this was her 10th anniversary, I realized that it meant that I’d missed my anniversary, as I began blogging before she did. My blog started slowly. In late 2002, I met Dave Winer, who was setting up a blogging server at the Berkman Center. I started a blog and put up a test post, then forgot about it. I returned some months later when the blog post was one of the leading Google results for me, and realized that I needed to put some content on the damned thing. My blog initially whined that I had been “guilted by Google” into blogging, but I quickly got the hang of things and started blogging about African politics and what I was learning about media attention and agenda setting.

In November 2003, I moved off of Berkman’s blogging platform and onto WordPress. My first few posts are lost to history, destroyed with a Berkman server move, but I’ve got everything I published on my own site starting on November 9, 2003. Two posts from that first month are particularly interesting. On November 10th 2003, I wrote about the Lord’s Resistance Army in northern Uganda and a refugee situation described by a UN official as “worse than Iraq”. Ironically, the most visited blogpost I’ve ever written also addresses Joseph Kony and his army, when I argued that a focus on fighting the LRA in 2012 was misplaced and that Invisible Children’s KONY 2012 campaign demanded scrutiny and reflection.

If that post shows that some issues stick around for years, another post just demonstrates how slow I am. On November 26, 2003, I wrote about a lecture I gave at Harvard Law School about Sean McBride and the UNESCO movement for a New World Information and Communication Order, an idea that is pretty central to Rewire, and a helpful reminder that I was working on that damned book a full decade ago.

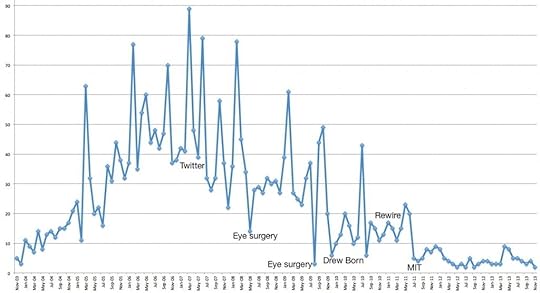

I knew I’ve been blogging less in recent years, but realizing I’d missed my blogiversary sent me to the database to see just how sharp the dropoff had been. Here’s what I found:

Blogposts per month, November 2003 – November 2013

The data is messy because my blogging has always been inconsistent. I enjoy blogging conferences and speeches, and the peaks on this graph represent conference blogging, usually the TED or Pop!Tech conference where I blog dozens of talks in the course of three or four days. But ignoring the peaks, I hit my blogging stride somewhere in 2005 and between then and 2008, averaged about a post a day. I began having serious eye problems in 2008 and had multiple surgeries, two of which show up as low points in terms of blog postings.

I assumed that I’d started blogging less when I became a Twitter user, but the data doesn’t bear that out. I joined Twitter in March 2007, when my blogging was at its peak. More likely is that my blogging fell off when I stopped posting bookmarks from Delicious as blogposts, which I did in September 2011. I thought my lessened blogging might correlate to becoming a father, but while there’s a dip when Drew was born, I rebounded quickly. Writing a book is more clearly correlated – I signed the contract for Rewire in January 2011, but I’d worked on a proposal for at least a year before that, and my blogging took a dive in 2010 and has never really recovered.

For me, the most striking correlation in this graph is the sharp fall in blogging that takes place in June 2011. Before then, I wrote at least ten mosts a month unless I was in the hospital or tending a newborn. Since June 2011, when I began working at MIT, I’ve never written more than ten posts a month.

This is not to say that MIT is responsible for making me a bad blogger. Working is responsible for making me a bad blogger. Prior to my time at MIT, I worked part-time at Berkman as a researcher, and spent the rest of my time as a board member, social entrepreneur, blogger and public speaker. Since the summer of 2011, I’ve had wonderful new uses of my time – advising students, new lines of research – and less wonderful uses of my time – performance appraisals, grant reporting.

I don’t regret the move. Running a research center has been an amazing opportunity and has taught me tons. But this graph helps me understand why I’ve felt something missing from my life. This blog has always been a place to toy with ideas, to work things out, to figure out what I’m interested in. I hope I can change my life and make more time for it in the coming year.

November 8, 2013

Remembering Aaron: activism and the effective citizen

This morning, I gave a speech to a gathering of public media executives from around the world, Public Broadcasters International. This evening, I will open a hackathon at the MIT Media Lab in memory of Aaron Swartz. The more I thought about it, the more I realized I wanted to talk about the same ideas to the two groups. Here’s the talk I gave this morning, which opened and closed with a remembrance of Aaron as an exemplar of multifaceted, effective citizenship. (It got both enthusiastic and angry reactions, including legendary documentarian Ric Burns taking the stage to proclaim himself the anti-Zuckerman. Which is great, as I’ve always wanted a nemesis.)

Today would have been Aaron Swartz’s 27th birthday. Early this year, the programmer, organizer and activist hanged himself, likely because he was overwhelmed by the aggressive prosecution he was facing. Federal prosecutor Stephen Heymann considered Aaron’s activism around opening scholarly research to be a felony and wanted to be sure Aaron faced prison time. Regrettably, my employer, MIT, did very little to block this prosecution, and there is an ongoing debate about MIT’s culpability in Aaron’s death that my students and I are deeply involved in. Representativs Zoe Lofgren and Ron Wyden have proposed reforms to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act under the title of “Aaron’s Law” and others are pushing for more comprehensive reforms.

But that’s not what people will be talking about at MIT later today. People will be mourning Aaron and discussing the circumstances of his death, but more will be looking to Aaron’s life as an inspiration. We’ll be hosting one of dozens of hackathons that will take place around the globe in Aaron’s memory. In Bangalore, Brisbane, Berlin, Buenos Aires and Boston, young people – many of them designers and computer programmers, but not all – will get together and talk about what they can do to make the world better. Some will write code that helps scholars share their work under open access licenses. Others will organize campaigns to expose corporate money in politics or challenge restrictions to free speech online. Still others will work on systems like Strongbox, designed to allow whistleblowers and leakers to share critical information while retaining their anonymity.

What the people who come to these hackathons have in common is this: they believe they can change the world, in ways both big and small. Aaron’s memory is a rallying point for them because Aaron dedicated so much of his brief life to seeking ways he could be effective, to have an impact. I knew Aaron well enough to understand some of his frustrations, and I know he was obsessed with the idea of being effective as a citizen, with making sure that the efforts he undertook to change the world had real, measurable, positive impacts.

There’s a good deal of talk about “the crisis in civics” in the United States, the idea that young people are too selfish and self-absorbed to be bothered to inform themselves about political issues or to vote. And there’s some data to support this: young people vote at a much lower rate than people a generation older, and few young people list a career in public service as one of their aspirations. But movements like Occupy, Los Indignados, the Arab Spring and Gezi protests, all of which had strong youth contingents or were youth organized, contradicts the idea that young people are disengaged. I don’t think we’re seeing civic indifference – I think we are watching the shape of civics change.

Consider Carmen Rios, 22 year old member of SPARK, a group that trains students in activism. Rios was angered by the Steubenville, Ohio rape case and was looking for ways to address concerns that high school athletic culture was breeding a sense of entitlement and domination that could lead to rape. Worked with a Colby College football player to demand that the National Federation of State High School Associations, a national association of coaches, offer resources on sexual assault prevention to coaches. 70k petition signatures, and the organization got on the phone to SPARK activists to implement a plan

Or meet Khalida Brohi. When she was just a teenager, her best friend was killed – an honor killing – because she wanted to marry a man she loved instead of consenting to an arranged marriage. To help young women in her native Balochistan gain independence, she launched Sughar Centers, a set of community centers where women came to practice embroidery and produce handicrafts for sale on international markets, putting money into family budgets. With earning power, the women are gaining more power and independence within their households. And when they are at the Sughar Centers, the women take literacy classes and talk about what roles they want to have in their communities.

Other inspiring activists work with code, not with thread. In reaction to Edward Snowden’s revelations about NSA surveillance, a group of Icelandic media activists began writing Mailpile, a new email client designed to make the powerful PGP encryption protocol usable by the average Internet user. Smári McCarthy, who is in charge of the project’s security, is well-known to the Internet security community as one of the activists behind IMMI, an ambitious project to give Iceland the world’s strongest legal environment for press freedom and to export this model to other countries. With Smári’s involvement and the urgent need for an alternative to mail systems like Gmail, Mailpile raised a $163,000 development budget from online donations within 5 weeks.

Not all young activists have turned away from politics and the legal system to seek change. Some are trying to hack law as effectively as the Mailpile team are hacking code. DREAM activists are young people, born in other countries but brought to America as children and raised in the United States. Many did not know that they were undocumented immigrants until they graduated high school and applied to college, where they faced massive tuition bills because they are not legal residents of the states where they live. The DREAM nine are activists who self-deported to Mexico and then sought asylum in the United States as a way of calling attention to the hundreds of thousands of young people facing the same predicament. They are using the legal system’s asylum process to challenge the broader policy environment while making their struggle public as a way to challenge existing stereotypes of the undocumented.

Effective citizens are multifaceted and multitalented. They recognize that there are many paths towards social change and that we might have to walk multiple paths simultaneously. The most effective citizens have a more complete toolbelt than most of us have – they understand that they may need different techniques at different points in their struggle, sometimes building businesses, other times building popular social movements. When facing complex challenges, like a US surveillance state that’s spun out of control, they may need to figure out how to use all these tools at the same time, a challenge that’s akin to playing chess on four boards simultaneously. Effective citizens are quickly learning that they need to work together, to build movements, so that someone who knows how write a tool to encrypt email can work with someone to pass legislation to protect email from surveillance and a group that can help the general public understand why encryption is important.

Thus far, I’ve cited five remarkable individuals and groups – surely this level of engaged citizenship isn’t something we can expect from everyone?

Well, maybe it should be. What these examples have in common is that they’ve moved beyond a vision of civics that centers on being informed and voting. Michael Schudson’s excellent 1998 book “The Good Citizen” argues that our vision of what it means to be a good citizen changes over time – analyzing the US, he sees four different models of citizenship that we’ve passed through over the years. He suggests that the model we often think of ourselves as embedded within – the informed citizen model – is a product of the progressive era, and may have lost its potency in the 1960s when effective citizenship moved into the courts, where people fought for rights through litigation. Our current picture of citizenship might be best described as “monitorial citizenship”, where our role as citizens is to keep track of powerful institutions like governments and corporations and to hold them to account when they violate citizen or consumer rights.

I think Schudson is important not because I think his vision of contemporary citizenship is the right one – monitorial citizenship doesn’t leave much room for citizens to create new forms of change. But I think it’s important to acknowledge that citizenship can – and is – changing. In looking at citizenship, activism and protest around the world, I see three themes that cut across many of the countries and communities I’m watching:

Citizenship is participatory.

The generation that’s grown up with the internet has a strong desire to see their mark upon the world. This may be a result of growing up in an interactive media environment where socializing involves making your mark on the internet. I see a lot of young people who are frustrated by political processes that don’t leave room for individual input. “If there’s nothing I can do to help, why are you telling me about this problem?” I think the rise of attention philanthropy, where people try to help a cause by calling attention to it via social media reflects this tendency – young people know how to create and spread media, and they can do so in ways that leverage their creative individuality.

I think the rise of platforms that invite people to give money to specific projects, to support individuals with microloans or with contributions to their artistic endeavors are a piece of the same impulse to see your positive effect on the world. The emergence of civic crowdfunding, where members of a community contribute to a project that we would normally think of as a public good seems like the logical extension of this line of thought, in both its positive and negative manifestations. It’s great that people want to have a hand in social change, but we may not want a world where social services go to those best able to pay for them or best organized to make them happen.

Citizenship is passionate.

With the rise of the internet, we’ve experienced an incredible rise in choice. We have access to news from all over the world, we have more movies at our fingertips than could fit in any video store. We can learn about virtually any topic (or write our own encyclopedia entry about it, if we choose.) And we are free to pursue our passions, whether they are shared by our friends and neighbors or not, because there’s certain to be someone out there that shares our dedication to the cause.

When I think of passionate citizenship, I mean to emphasize the negative sense of the term as well as the positive. Jason Russell’s passion about children affected by war in northern Uganda led him to build Invisible Children, an organization that came to widespread attention with their Kony 2012 campaign… which, in turn, ignited the passions of millions of people who heard about the Lord’s Resistance Army for the first time. Critics – myself included – argued that capturing Joseph Kony wasn’t an appropriate priority for US policy in Central Africa. But that’s the challenge with a politics of passion. Russell followed his passions and channeled the passions of others – it’s a challenge for the rest of us to figure out how to have a dialog with passionate, well-meaning people that can examine the assumptions behind those passions and seek a way forward as a society and a government.

Citizenship is pointillist.

When civics is about people following their passions, it’s hard to have a dialog in the public sphere. The issue you are passionate about and want to debate may not be one I find remotely interesting. How do we come together and find solutions through conversation and compromise if we can’t agree on what issues are the key ones society faces? Bill Kovachs and Tom Rosensteil posit the idea of the “interlocking public”, the idea that my interest in West Africa gets communicated to my friends and family, who become informed on issues there through me, and my father’s interest in prison reform means that I’m somewhat knowledgeable about that subject. We follow our passions, become knowledgeable and inform one another, allowing us to debate complex issues as a public.

There’s another possibility, though, which is that publics come together in opposition, but not in creative cooperation. Sociologist Zeynep Tufekci observes that protests in Taksim Square over the proposed paving of Gezi Park brought together Kurdish separatists, Turkish nationalists and gay and lesbian activists, a group who would otherwise be extremely unlikely to interact with one another. Such groups were able to unite in their frustration with and opposition to Tayyip Erdogan, but had a difficult time cooperating on a broader vision of a reformed Turkey. As with the Tahrir Square protests, it was easier to come together in opposition than in cooperation, and there are open questions about how coalitions and cooperation emerges in the face of pointillistic civic engagement.

I offer this vision of civics not because I think it’s fairer, more successful or more participatory than conventional views of civics – I am deeply concerned about some aspects of this vision, including the challenge of creating a public dialog from a diverse set of passionate perspectives. I offer this more as description than prescription, a reflection of what I am seeing in working with with digital activists in the US and around the world.

But I do think civics is changing in the ways I describe, and I think media should consider what role it can and should have facing this new form of civic practice.

If we believe that civics is participatory, we need to move beyond a model where journalism informs us and makes us better voters to a model where journalism helps us get involved with issues we care about. I worry that we often report stories in a way that readers feel helpless and disempowered. The news tells us that injustice and tragedy are taking place but offers little insight on how we could help make things better. It’s easy to understand why news can lead some to a pattern of learned helplessness, a sense that they are powerless to affect circumstances locally or globally.

There are creative projects proposed to help us move from information to engagement. Shoutabout pairs news stories with ways to get engaged with an issue, often showing petitions to sign or organizations to support on multiple sides of an issue. PBS is working with Shoutabout, as is Christian Science Monitor. In most cases, they are pushing readers and viewers to fairly thin modes of engagement, but it’s a start, and a recognition that news organizations can do more than identify problems.

I see David Bornstein’s Solutions Journalism Network as a fellow traveller, featuring people and organizations in their coverage who’ve found novel solutions to complex social problems. We need journalists to do this work, identifying solutions and evaluating their effectiveness.

At a recent conference in Berlin, I was introduced to the work of Ulrik Haagerup, who is leading the Danish Broadcasting Corporation towards something he calls “constructive journalism“. Reporters on the network aren’t able to report on an issue, like the overuse of antibiotics in the dairy industry, without finding alternatives, a farm that produces milk commercially without using antibiotics. It’s not possible to report every story this way, but it’s a fantastic challenge to think about reporting in a way that helps people move beyond problems to solutions.

More than linking individual stories to specific campaigns for change, I hope that journalists can think about the different paths through which people are seeking change. There’s a tendency to overfocus on where we think news will be made: in Congress and parliaments, in announcements from big companies. It’s easier to report on an election or a government shutdown than on slow, gradual changes like the growing acceptance of gays and lesbians, or a move in scholarly publishing towards open access models. For people to take the steps to be effective citizens, they need help seeing the effects they are having on the world.

I opened this talk by remembering Aaron and will close the same way. I miss Aaron, but I see him in the students I teach and in the activists I worth with. I think he would be happy to be remembered with hackathons, with people embracing the idea that they can make the world a better place and that they, as individuals, can help bring about change. I want to build a world where people like Aaron can be effective, can help change the world, and I want your help. Thanks for listening.

November 5, 2013

Members, fans and complementary revenue models for the New York Times

The other day, I had coffee with a friend who works for the New York Times. Early in the conversation, I admitted to him that I’ve developed a love/hate relationship with the Times. I love much of the paper’s content (though I share Greenwald’s wish that the Times would call torture “torture”) and find that many of the most interesting stories I read in a week come from the Times. But I am getting really sick of the Times’s efforts to nickle and dime me as a digital subscriber. Despite paying for access to the paper’s excellent content, they somehow make me feel like a piker if I’m not a subscriber to the print edition at nearly a thousand dollars a year.

I can access the Times through MIT, but decided that I read the paper often enough on other devices and outside of MIT’s network that I should become a digital subscriber. For a couple of weeks, I was a satisfied customer, reading far more than my allotment of ten free stories in my browser, and flipping through the paper on my phone when in transit or waiting on lines. But then the Times implemented its new “three articles a day” plan for mobile readers of the paper. My digital subscription – which costs $240 a year – includes a tablet and web version of the newspaper, but getting unlimited access via my phone costs an additional $180 a year.

Because the Times evidently takes its business cues from the widely despised cable TV industry, they like to bundle their content. As a result, the best way to get digital access is to purchase it bundled with the paper edition of the newspaper… which the Times won’t deliver to my rural address. I could also downgrade my bundle from web and iPad to web and phone, but it seems bizarre to me that digital data paid for in one place can’t be used in another.

And so I’ve found myself in the space of Times hacking, looking for ways to get content I want to read for a less exorbitant price than the Times wants to charge. (My current strategies: I am using my web subscription to dump articles to Instapaper, which I then read on my phone. Take that, Big Media!) Here, I join a large cadre of people who proudly post their tips for defrauding the Times so they can continue reading for free.

Let’s compare this situation to another media organization many New York Times readers rely on: public radio. No one writes articles bragging about how they avoided donating to NPR or how they get podcasts for free. In part, that’s because we don’t have to – public radio, for technical and historical reasons associated with the challenge of monetizing broadcast radio, is free by default, supported by voluntary donations. But there’s another reason: people love public radio, want to support it and feel guilty when they don’t.

I don’t intend to argue that the New York Times should become member supported. But I do want to make the case that they would benefit from thinking about the relationship public radio stations and shows have built with their members.

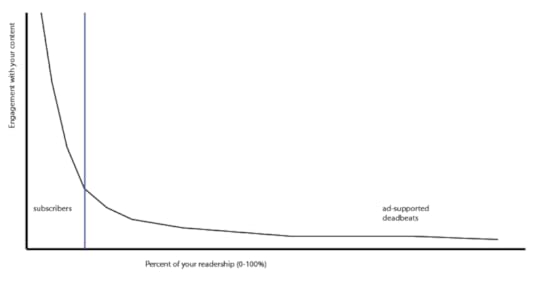

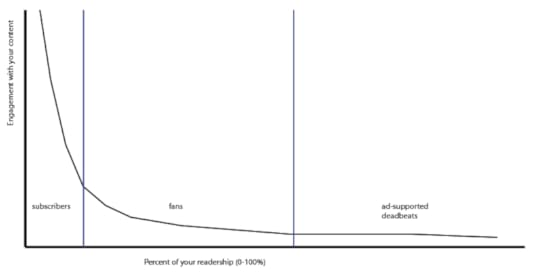

There’s a diagram that often gets drawn on napkins or whiteboards when media people get together: a Pareto, or long-tail curve, where the Y axis represents how engaged with content your readers are, and the X axis represents your reader population. Near the origin of the graph, the curve is very high – those are the small set of users who are deeply engaged with your content. Farther from the origin, as the curve flattens out, we have the majority of readers, who engage with your content occasionally. For the New York Times, it’s key to turn the folks on the left of the graph into subscribers and to make money from the right of the graph through ads. And as we head towards Peak Ad, it’s increasingly important to move readers across the paywall that separates the left and right side of the graph.

Public radio stations, producers and podcasters face a similar graph. In their case, it’s critical to get the left side of the graph to become members or make donations. But instead of dropping a paywall, they use a combination of gratitude and guilt to persuade their most engaged listeners to support their programming. When they do it well, their listeners feel terrific: Ira Glass urges listeners to defray WBEZ’s bandwidth costs for delivering This American Life online, telling us that if we could give more than $5, we’d pay not only our costs but those of listeners who don’t donate. And if we don’t donate? We feel guilty, but not criminal. The New York Times, which reminds me how many of my three free stories I’ve read on my phone, makes me feel like there’s a security guard trailing me to make sure I don’t stuff an extra New York Times article down my pants.

I suspect the business folks at the Times are operating under the assumption that there are only two places to be on their subscriber/revenue curve – you can be a subscriber and pay $300-800 a year, or you can be an outsider and cover a tiny fraction of your free riding with ad views. But there’s another option: the Times could start thinking of its readers in terms of subscribers, fans and passers-by. The Times won’t monetize passers-by, except through ads – these are folks who stumble onto the site occasionally and may not even realize they are reading Times content. That’s frustrating, but that’s how the web works. And the Times should certainly cultivate subscribers and encourage more fans to become subscribers. But they might do a better job of that by courting their fans, instead of locking them out.

Fans could be encouraged to support content on the Times not through a threat of locking them out, but by encouraging them to support the paper, and especially, the parts of the paper they value the most. When I donate to WNYC, I always take the opportunity to tell WNYC that I’m not a customer of the station as a whole, but of On The Media, my favorite outlet for smart media criticism. I have to think that some Times readers would love the opportunity to give to the paper and say, “Please don’t give this to Maureen Dowd. I’m giving in the hope of more Ta-Nehisi Coates op-eds.”

A New York Times that courted its fans would help fans track how much content they access from the Times, and perhaps, from other sources as well. It would take a suggestion from Doc Searls’s ideas about tracking usage of public radio and allowing users to donate to stations or programs that they listen to often. It might recognize that fans of the Times are fans of other publications, like The Guardian, the Christian Science Monitor or Planet Money, and band together with some of those other outlets to build a common tracking, membership and recommendations platform. (It would be very interesting for New York Times fans to discover they’re deeply dependent on the site’s content… or that they actually read other sources more than the times.) It could start treating fans who choose to subscribe as members, thanking them for making media accessible to others rather than making it clear that their content is only for those who pay.

Making news accessible for non-readers as well as readers is critical. News organizations have two bottom lines: they need to make enough money to keep the presses running, and they need to have a civic impact, holding the powerful responsible and giving citizens the information they need to participate in a democracy. As ad revenues decline, there’s a tendency for paywalled news sites to provide information only to the small group of people who subscribe to the paper. In the process, it’s possible that newspapers will lose their broader civic impact. If sites could find a way to get support from non-subscribers as fans, they could open their content to a broader audience and have more civic influence.

This would require some serious rethinking for the Times, and it’s quite possible they can support their reporting without making this change in the short term. But if we’re moving to a world where people are less dependent on a single media source, like the Times, and more inclined to pick and choose news from multiple sites, the Times will need to realize that fans can’t pay $300 to each content provider they want to support. Perhaps it’s time for the Times to start embracing and celebrating those fans, instead of alienating them.

October 29, 2013

Ta-Nehesi Coates and Hendrik Hertzberg at MIT on opinion journalism

Tom Levenson introduces Ta-Nehesi Coates and Hendrik Hertzberg , who are in conversation tonight at MIT’s Stata Center on the topic of opinion journalism. The event is hosted by CMS/W, MIT’s Comparative Media Studies and Writing department, where Coates is a scholar in residence. Both Coates and Hertzberg are giant figures in contemporary journalism, from different professional generations.

Coates begins by admitting that he was burned out at the end of his last semester at MIT, but ended up missing his students a week after he left Cambridge. Teaching writing, he tells us, is deeply different from writing. Once you write well, you write on autopilot. But you can’t teach writing without thinking about the art form. Coates was reminded of this when Hertzberg came to MIT to talk with his students – not only is Hertzberg a master of opinion journalism, but he’s deeply insightful about the process of writing and of constructing complex and subtle arguments.

Coates asks Hertzberg about his process: does he craft individual sentences or whole arguments? Hertzberg confesses to being a difficult writer – he struggles over sentences, particularly the first sentences in a piece. “It’s important to be fresh, to avoid cliches”. And while Hertzberg has roadmaps for his arguments, he explains that he spends a great deal of time crafting each sentence, ensuring the tone and imagery is right to construct the tone and ideas he needs to convey.

Prompted by Coates, Hertzberg identifies Orwell and the Harvard Crimson as his most important writing teachers. He explains that, in writing for the Crimson, your copy was posted into giant comment books where editors ripped the work to pieces. Good pieces were marked “OOTAG” – one of the all time greats – and poor ones marked “PTS” – Pour to sea. All comments were signed – you knew exactly who was savaging you. So Hertzberg’s experience at Harvard came through the practice of newspaper writing, not the classroom. (He tells us that, if there hadn’t been a draft for Vietnam, he’d have dropped out and worked for a local paper, and likely burned out.)

Hertzberg loves the appearance of newspapers – he tells us about a cross-country trip where he bought and saved local papers, documenting the journey one front page at a time. In his work at the Crimson, he loved laying out pages and wonders if he would have become a graphic designer had he chosen a career more deliberately. “That sense of proportion, balance and beauty” informed his work with the New Republic, his concern about how the magazine’s cover appeared and informs his work today.

Coates confesses that his New York literati friends wonder whether people can actually write at MIT, and explains that this is a form of defensiveness from people who can write, but don’t understand math and science. Impressed by the quality of his writing students here, Coates asks Hertzberg whether it’s possible to teach writing. Hertzberg explains that editors – at least the really good ones – are writing teachers. “They show you what’s wrong and you can’t help but learn from that.”

Hertzberg explains that his working method isn’t the only possible way – it’s possible to be a columnist without caring about sentences. He cites Paul Krugman as someone who is less obsessed with craft than with creating lucid, readable arguments. “If you have a great opinion and can express it clearly,” you ma be able to be a great opinion writer without being a great writer. Krugman, Hertzberg argues, has a narrow set of well-developed beliefs and explores them again and again without boring the reader.

There are many ways to report, Hertzberg says: talking with friends, reading online, getting out of the house and experiencing events. He cites Murray Kempton as a columnist who got experienced the world on a bicycle and used that experience to inform his writing. But it’s possible to use any number of methods to build great opinion columns.

Coates notes that Hertzberg writes about once every other week and wonders how he would write if he produced three columns a week. Hertzberg allows as his writing would come to a screetching halt with his suicide. Writing beautiful multiple times a week parallels Michael Jordan’s efforts in basketball. Coates notes that writers feel guilty about being slow writers; Hertzberg notes that Coates has the gift of Sitzfleish, the ability to sit in the chair and produce words.

Blogging is easier than opinion column writing, Coates and Hertzberg argue, because blog posts don’t need to have a shape, while columns need to. As a result, Hertzberg explains, blogging is a recreation. This isn’t to say it’s not worth reading, but that it’s a different pursuit. Hertzberg notes that Coates’s blog serves as a diary on his other writing, giving insight on what he’s developing.

Coates talks about the lowered barriers to writing in public these days. He began writing in public when the New Republic printed an excerpt from The Bell Curve, a notorious exploration of race and achievement in the US. Coates was furious about the piece and notes how hard it was to share his frustation, as a student at Howard University surrounded by brilliant black people, and have that opinion heard. Hertzberg notes that while everyone can have a press now, we don’t all get the fleet of trucks that delivers the papers. “It remains to be seen whether competition, whether this immense supply, will increase the quality of writing.” The proportion of well-informed opinions is clearly smaller than in years past – whether or not the cream will rise to the top is less obvious. And it’s quite obvious that it’s much harder to make a living as a writer.

“Writing is becoming a group activity. It’s something that a large number of people do part time.” Hertzberg explains that writing used to be a living, even if not a great living. Coates wonders whether a Harvard Crimson byline still guarantees future employment in journalism as it used to. Hertzberg explains that the paper is, by choice, far less selective about writers than it used to be, and that this is likely a good thing for the institution.

Hertzberg notes that he spends as much time reading blogs as he does reading newspapers and magazines. He’s bothered that he misses some important stories. (He religiously reads the New York Review of Books, the New Republic and less religiously, the Nation.) “Blogs are addictive. Every hour, you take a little snort of it,” he says.

Coates asks about the importance of writing with conviction: if you don’t believe it, I’m never going to believe it as the reader. And given that there’s so many things you can do other than writing an essay, you’d better grab the reader by the collar and demand attention. Why would someone do something this hard?, he asks Hertzberg. The simple answer: being a newspaperman was the only thing Hertzberger wanted to do.

Hertzberg explains the romance of newspaper journalism, the emotion that led people like Carl Bernstein to work their way up from copy boy to reporter. It’s probably healthier and more professional, he notes, but some of the romance may be gone.

Coates thought Hertzberg must be an effortless writer. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth – he keeps an air mattress in his office and usually ends up sleeping in the office at least once, sometimes twice, during a column. But he doesn’t see a correlation between suffering and the quality of his writing, and if he could find a way to work without suffering as badly, he’d gladly claim it.

Tom Levenson offers a first question: Is the degredation of our political culture linked to the status of our opinion writing? Hertzberg notes that it is possible to live in an echo chamber and those echo chambers are likely damaging our politics. But he wonders if things were better in the age of strong gatekeepers. We all live in our own universes, he tells us – the Republicans may live in one of more epistemic closure.

Levenson persists: as a science writer, he’s seen the polling shift on climate change and wonders to what extent that shift (away from a belief in human-influenced climate change) is the responsibility of opinion journalism. Hertzberg notes that the blame is more properly placed on the political system. If we’d not faced filibuster, we’d have had a cap and trade system for carbon emissions. How can we take climate change seriously if our government doesn’t do anything about it? “Our politican institutions can’t give us what we want, and eventually we stop wanting it. We blame the failure on the media,” rather than on the actual machinery of government that is supposed to solve our problems. Hertzberg explains that the filibuster is his “unified field theory” – he writes about it as much as his editors will allow him to.

“The constitution, an incredibly advanced machine for 1789, isn’t working so well. But observing that isn’t as easy as figuring how to fix it.”

Patsy Baudoin asks where the joy is in writing, given how much Hertzberg suffers for his art. He notes that there’s a big pleasure in getting these pieces done, a great deal of pleasure in having the work praised, and little pleasures associated with a well-placed phrase. But those pleasures are counterbalanced by the dread of not finishing the piece.

A questioner notes that while government may be broken, figures like the Koch Brothers have had enormous influence on debates like climate change. He then asks what bloggers and aggregators Hertzberg finds most useful, and what he and Coates think about Greenwald’s writing about Snowden and his new journalistic project. Hertzberg identifies Andrew Sullivan’s blog as his favorite, followed by Coates and Fallows at the Atlantic. Talking Points Memo merits a daily visit, as does the Guardian. In addressing Koch, Hertzberg suggests organizations accept as many gifts as possible, as a theatre paid for by the Koch brothers represents lost opportunity for the right.

In addressing Snowden and Greenwald, Hertzberg thinks of them as inevitable historical figures, genies that cannot be put back into the bottle. We need a polity that does what it’s supposed to do and can live with what these revelations have exposed. He admits this isn’t an answer with great moral clarity, but that he’s still wrestling with these implications.

Coates wonders how journalists who call for Greenwald’s arrest can consider themselves to be journalists. He cites the conversation between Bill Keller and Glenn Greenwald in the New York Times yesterday and suggests that Greenwald has a tendency to piss people off. In the piece, Greenwald demands Keller to explain why the New York Times’s inconsistency on use of the word “torture” is considered “objective”. That’s a deeply important distinction, and one he is glad Greenwald is demanding be addressed.

In addition to the blogs Hertzberg reads, Coates namechecks Grantland, The Atavist, New York Magazine, and The Toast, a small blog he finds consistently hilarious.

A questioner, a science writing grad student, notes that there’s a lot of trash journalism that’s hiding the quality journalism being produced. How do we feature and highlight the best journalism being produced? Hertzberg warns that we shouldn’t glorify the past too much: “Most journalism has always been pretty dreadful. More people have been interested in the contemporary Kim Kardashian than the contemporary Glenn Greenwald or Bill Keller.” He suggests that we’re at a “Gutenberg moment”, wondering when and how journalism will eventually settle. In sheer numbers, he argues, there is more good journalism done than ever, but finding and collating it is a problem.

Another question asks about journalism as a profession. Hertzberg notes that journalism is now both more professional and more compatible with poverty. He suggests that no one go into journalism in a half-hearted way. For Hertzberg, journalism was the path of least resistance – it’s not today.

Tom Friedman at the New York Times, George Will at the Washington Post seem to hold their jobs forever, one questioner observes. Would journalism be healthier with journalistic term limits? Should columnists have the job security that Supreme Court justices have? Coates wonders how much influence columnists actually have on the culture, and suggests that they more often reflect the culture. For Coates, it’s important to write in different ways – the short form of the blog, the long form for The Atlantic, his occasional columns in the New York Times. Each exercises a different set of literary muscles and he suggests it would be better for the writers than for the audiences.

A former student at MIT notes how valuable she found Coates’s writing about the roots of libertarianism as she reacted to the Occupy movement. She wonders whether Coates will piece together his writings in the news into a long form? Coates suggests that this is what he actually does. He uses the blog as a place to develop ideas he builds in longer formats. “It’s a record of me thinking things out. I have no idea what effect I’m going to have on people thinking about Ron Paul… I don’t really write to convince people.” Coates writes by arguing with himself and believes that his strongest work comes from that process of argument, testing out arguments and seeing what works.

A questioner asks Coates: “Who do you read that’s black?” Coates offers Wesley Morris as a regular read, then notes that most of the black writers he focuses on are historians, writing books, not writing magazine articles. (He later namechecks Jamel Bowie and Anna Holmes as black writers doing terrific work in short form.) “The only person I read who does what I do is William Jelani Cobb.” This suggests that we have a real problem with an absence of black authors in magazine writing. “But most of my influences come from books”, Coates explains, noting that James Baldwin is his most powerful influence.

Chris Peterson notes that Coates argued that you need to grab readers by the shirt collar and shake them. How do you do this when you’re working through your ideas and agenda in writing a piece, he asks Hertzberg. Hertzberg notes that he’s lucky – as a New Yorker writer, he doesn’t need to grab people by the lapels. Readers come to you with faith and trust, that your piece will be worth reading. It’s a giant advantage and privilege. Hertzberg is glad that the New Republic is under new management, but wonders whether the magazine is now working too hard to grab the reader’s lapels. These magazines have an intimate relationship with their readers and the journalism Hertzberg admires does less lapel grabbing. On the web, however, you need to do more of that grabbing because there are no blogs that have the reputation for quality that the New Yorker or New Republic has.

A questioner explains that he comes to Coates’s blog again and again not because of the great writing, but the ethical core. Coates notes that there are people who think George Will is a good writer. Coates says bluntly, “He lies,” in his pieces about football and violence and his pieces about climate change. Hertzberg talks about deep and shallow beauty – he enjoys reading some writers because they write beautifully, but argues that they don’t think beautifully.

A questioner asks both whether they read the Huffington Post and what they think of the quality. Hertzberg allows that the question is like referring to the universe and asking what you think of the quality of the stars. It’s vanity publishing writ large, he suggests, and wonders if there’s any way of reading the Huffington Post other than looking at who links to pieces of it. Coates simply doesn’t read it, and notes that HuffPo’s misleading headlines are another form of lying.

A final questioner wonders about the centrality of politics in opinion journalism. Do writers approach more gradual, slow issues more gradually than writing about fast-breaking political stories? Hertzberg argues that culture, ultimately, is more important than politics. But the stakes are higher in writing about politics, as the real-world consequences are great. Art is superior to journalism, and music is the most superior to all, Hertzberg asserts.

Coates agrees – music is superior because it crosses language. But he doesn’t think his process is different in writing politics versus culture, as he’s always trying to figure something out. Sometimes the most popular pieces Coates writes are the ones where he’s dismissing something as ridiculous, but writing those pieces isn’t very satisfying because it doesn’t involve working something out.

October 17, 2013

Zeynep Tufekci on protest movements and capacity problems

MIT’s Comparative Media Studies hosts a weekly colloquium, and this week’s featured speaker is sociologist and movement theorist, Zeynep Tufekci. Zeynep describes herself as a scholar of social movements and of surveillance, which means this has been an interesting and challenging year. The revelations about the NSA hit the same week as the Gezi protests in Turkey. She explains that it’s hard to do conceptual work in this space because events are changing every few months, making it very hard to extrapolate from years of experience.

Not until protests reached Gezi, Zeynep tells us, did she feel comfortable putting a name on the phenomenon she’s been seeing in her research in the Arab Spring, through Occupy and in the Indignados movement. To explain her theory, she opens her talk with a picture of the Hillary Step on Mount Everest. The picture of Everest, taken a day that four people died on the mountain, shows the profound crowding on the mountain, which made Everest so dangerous as climbers had to wait for others to finish.

Because of technology and sherpas, more people who aren’t great climbers come to Everest. Full service trips (at a $65,000 price point) can get you to base camp and get you much of the way up the mountain, but they cannot prepare people to climb the peak. There’s an uptick in deaths in the 1980s once the basecamps become developed and more people can get to the mountain.

People have proposed putting a ladder at Hillary’s Step, hoping to make things more difficult. But the issue is not the ladders – it’s the fact that it’s very, very hard to climb at altitude. The mountineering community has suggested something else: require people to climb seven other high peaks before they reach Everest.

This is an analogy for internet-enabled activism. In talking about internet and collective action, we tend to talk about ease of coordination and community. Zeynep worries that we’re getting to base camp without developing altitude awareness – in other words, some of the internet’s benefits have significant handicaps as side effects. The result: we see more movements, but they may not have impact or staying power because they come to public attention much earlier in their lives.

She suggests we stop looking so much at outputs of social media fueled protests and start looking instead at their role in capacity building. She recommends that we stop looking at offline/online distinctions and look more at signaling approaches to protests. This requires a game-theoretic framework, and consideration of movement capacities and strategic tensions.

With that as backdrop, she takes us to Gezi Park and Taksim Square, which she suggests we see as analogous to Chelsea or Soho, a neighborhood where people go to party. It’s one of the very rare greenspaces in that part of the city. It was to be replaced with the replica of an Ottoman barracks, which was going to be used as a high-end shopping mall, something that there are many of in Istanbul.

Neighbors of the park held a small protest, probably 30-40 people. But that small protest was met with pepper gas, which is a clear overreaction to a small, peaceful protest. People got upset about the protest and saw it as a personal decision by Erdogan, who seemed to be pushing the development over local wishes and over the wishes of the people of Istanbul.

People took to the streets and to Twitter. Why Twitter? While CNN International was showing protests in Taksim, CNN Turkey was showing a documentary about penguins. Zeynep found this deeply surprising – “We’re not China!” But there are different kinds of censorship, and this was censorship by media conglomerates, which are controlled by people who want government contracts. To curry favor with the government, media tends to self-censor… and if they don’t, they often get phone calls from the government. So Turkey isn’t China, but it’s a bit more like Russia, though with open elections and a more open public sphere. The backdrop for Gezi includes a 11-year single party reign, a polarized nation, an ineffective opposition and an electoral system that makes it hard to start new parties.

These protests in the middle of the city showed the depth of media corruption in Turkey, because social media documented the clashes with the police. Outrage over the police action and media interaction turned into a long-term occupation of Gezi Park. So, Zeynep tells us, she packed up her gear: a helmet, a gas mask, sunscreen, a recorder and a digital camera, all air-gapped from the internet.

Zeynep describes the encampment as Smurf village, a happy and friendly version of “Woodstock meets the Paris commune”, but threatened by Gargamel, the police showing up periodically. Roma ladies who normally sell flowers to tourists were selling Anonymous masks, ski goggles and spray paint. (Who says the developing world needs help with entrepreneurship?, she tell us.)

She walks us through the iconography – #diren (“resist”, or “occupy”), penguins (a reference to CNN showing penguin documentaries rather than clashes.) While the icons imply a common movement, there wasn’t one. She shows us a picture of a Kurdish activist, a far-right activist and an opposition party activist in the same frame, and another picture of macho soccer fans meeting with a local feminist group. Soccer fans traditionally call referees “faggots” in their chants, and the soccer fans protesting wanted to call the police faggots… but got confronted by local gay and lesbian activists who said, “No, we’re the faggots – we’re the guys protesting!” The two groups had a meeting, and the soccer fans ended up chanting “Sexist Erdogan”, newly aware of the members in their community. Zeynep takes pains to explain the heterogeneity of the crowd: a Kurdish activist and a gay rights activist talking about why they hadn’t interacted before.

Despite how much positivity came from these protests, there were real risks – people went to sleep after writing their blood types on their arms. Serious injuries happened every day, from tear gas cannisters and police confrontations.

What did the internet do? It broke media censorship, created a counternarrative, and allowed coordination. To tease CNN, people photoshopped penguins into protest footage, urging CNN Turkey to come to the protests. Humor was a major weapon, drawing attention to the persistent censorship. Zeynep makes the point of how difficult it is to censor in a social media age, pointing to the differences between Gafsa and Sidi Bouzid protests in Tunisia.

Twitter was critical for the Gezi protests, not just for generating a counternarrative, but for protest coordination. For the most part, the internet worked, and local businesses turned on wifi to make it accessible to protesters. Activists called friends who tweeted on their behalf. Erdogan wasn’t going to turn off the internet, Zeynep tells us, because of fear he’d be seen as an autocrat.

Despite all this adhoc coordination, there was no real centralized leadership, and very little delegation of authority. It was extremely unclear what demands were beyond “Don’t raze Gezi Park.” Because there was no need to deal with these thorny questions of representation and delegation to coordinate the protests, the movement did not build a strong leadership culture.

The Gezi protests were brutally dispersed, at which point, protest conversations moved to neighborhood forums, which were also dispersed. While popular, these protests haven’t been able to create structures that engage the government in the long term.

Despite the successes of the protests, Zeynep reminds us that Gezi and the open internet never overwhelmed the state’s capacity to surpress the protests. It simply overwhelmed state capacity to suppress without unwanted side effects of embarrassment, loss of tourism revenues, loss of prestige, loss of being seen as a modern civic space.

To understand these protests, Zeynep turns to Amartya Sen and capacity building, looking at those capacities, not traditional outputs, as the benefits of development. The internet gives us some new capacities, but that may undermine other capacities: we end up at base camp very easily, but we don’t know how to negotiate Hillary’s step. We can carry out the spectacular street protest, but we can’t build a larger movement to topple or challenge a government.

Protests are very good at grabbing attention and putting forth counternarratives. They create bonding between diverse groups. They also signal capacity, but it’s a different capacity than it might have been fifteen years ago. Zeynep tells us that this is not a “cheap talk” argument – protesting isn’t too easy – it’s just that a protest isn’t going to topple the government. This isn’t a slactivism argument either – it’s an argument about capacities. The internet seems to be very good at building a spectacular local optima – a street protest – without forcing deeper capacity development.

In the past, gaining attention meant gaining elite dissent and buy-in. Now, gaining attention may also have a cost – you may or may not have achieved elite buy-in, which means you may gain polarization. Gaining attention on your terms means not gaining the dominant narrative.

Digitally enabled protest allows for much more ability for social interaction amongst the machines. That said, the internet is a homophily machine, and joining a movement can be a step towards a homophilous group. Movements like the Tea Party are thriving in these environments.

Zeynep shows a slide of a gazelle stotting to make her last point. Jumping in the air isn’t a great way to avoid predators – it’s a way to show that you’re really fast and would be hard to catch. But animals that can’t evade predators can also jump. Zeynep warns us that ignoring the March on Washington would have been a mistake, which might have ousted a President, but Gezi was not that sort of protest.

She urges us to consider “network internalities”, development of ties within networks that would allow social networks to become effective actors. Movements get stuck at no, she argues, because they’ve never needed to develop a capacity for representation, and can only coalesce around saying no, not building an affirmative agenda.

October 15, 2013

Google cars versus public transit: the US’s problem with public goods

I have an excellent job at a great university. I have a home that I love in a community I’ve lived in for two decades where I have deep ties of family and friendship. Unfortunately, that university and that hometown are about 250 kilometers from one another. And so, I’ve become an extreme commuter, traveling three or four hours each way once or twice a week so I can spend time with my students 3-4 days a week and with my wife and young son the rest of the time.

America is a commuter culture. Averaged out over a week, my commute is near the median American experience. Spend forty minutes driving each way to your job and you’ve got a longer commute than I in the weeks I make one trip to Cambridge. But, of course, I don’t get to go home every night. I stay two to three nights a week at a bed and breakfast in Cambridge, where my “ludicrously frequent guest” status gets me a break on a room. I spend less this way than I did my first year at MIT, when I rented an apartment that I never used on weekends or during school vacations.

This is not how I would choose to live if I could bend space and time, and I spend a decent amount of time trying to optimise my travel through audiobooks, podcasts, and phone calls made while driving. I also gripe about the commute probably far too often to my friends, who are considerate if not entirely sympathetic. (It’s hard to be sympathetic to a guy who has the job he wants, lives in a beautiful place, and simply has a long drive a few times a week.)

Hearing my predicament, one friend prescribed a solution: “You need a Google self-driving car!” The friend in question is a top programmer for a world-leading game company, and her enthusiasm for a technical solution parallels advice I’ve gotten from my technically oriented friends, who offer cutting edge technology that is either highly unlikely to materially affect my circumstances, or would improve some aspect of my commute rather than change its core nature. (Lots of friends forwarded me Elon Musk’s hyperloop proposal. And lots more have suggested tools I can use on my iPhone so that a synthetic voice will read my students’ assignments aloud while I drive.)

“I don’t want a Google car,” I tell her. “I want a train.”

In much of the world, a train wouldn’t be an unreasonable thing to ask for. New England has a population density comparable to parts of Europe where commuting by train is commonplace. I live ten kilometers north of downtown Pittsfield, MA, which lies on a rail line that connects Albany, NY with Boston. There is, in fact, one train per day from Pittsfield to Boston. It takes almost six hours to make a journey that can take me as little as 2.5 hours (if there’s no traffic) to drive, and operates at a time that makes it impossible for me to use it for business travel. I want a European train, a Japanese train, not necessarily a bullet train, but something that could get me from the county seat of Berkshire county to the state capitol in under two hours.

Such a train exists on some of the proposed maps for high speed rail service in New England. But given the current government shutdown, and more broadly, a sense that government services are contracting rather than expanding, it’s very hard to imagine such a line ever being built. In fact, it’s much easier for me to imagine my semi-autonomous car speeding down the Mass Pike as part of a computer-controlled platoon than boarding a train in my little city and disembarking in a bigger one.

There’s something very odd about a world in which it’s easier to imagine a futuristic technology that doesn’t exist outside of lab tests than to envision expansion of a technology that’s in wide use around the world. How did we reach a state in America where highly speculative technologies, backed by private companies, are seen as a plausible future while routine, ordinary technologies backed by governments are seen as unrealistic and impossible?

The irony of the Google car for my circumstances is that it would be inferior in every way to a train. A semi-autonomous car might let me read or relax behind the wheel, but it would be little faster than my existing commute and as sensitive to traffic, which is the main factor that makes some trips 2.5 hours and some 4 hours. Even if my Google car is a gas-sipping Prius or a plug-in hybrid, it will be less energy efficient than a train, which achieves giant economies of scale in fuel usage even at higher speeds than individual vehicles. It keeps me sealed in my private compartment, rather than giving me an opportunity to see friends who make the same trip or meet new people.

There’s a logical response to my whiny demands for an easier commute: if there were a market for such a service, surely such a thing would exist. And if train service can’t be profitably provided between Pittsfield and Boston, why should Massachusetts taxpayers foot the bill for making my life marginally easier?

This line of reasoning became popular in the US during the Reagan/Thatcher revolution and has remained influential ever since. What government services can be privatized should be, and government dollars should go only towards services, like defense, that we can’t pay for in private markets. As the US postal service has reminded us recently, they remain open during the government shutdown because they are mandated by Congress to be revenue neutral. Ditto for Amtrak, which subsidizes money-losing long distance routes with profitable New England services and covers . Our obsession with privatization is so thorough in the US that we had no meaningful debate in the US about single payer healthcare, a system that would likely be far cheaper and more efficient than the commercial health insurance mandated under the Affordable Care Act – even when governments provide services more efficiently than private markets, the current orthodoxy dictates that private market solutions are the way to go.

The problem with private market solutions is that they often achieve a lower level of efficiency than public solutions. Medicare has tremendous power to negotiate with drug manufacturers, which brings down healthcare costs. Private insurers have less leverage, and we all pay higher prices for drugs as a result, especially those whose healthcare isn’t paid for my a government or private organization and who have no negotiating power. The current system works very well for drug companies, but poorly for anyone who needs and uses healthcare (which is to say, for virtually everyone.)

It’s possible that the same argument applies to transportation, though the argument is less direct. It’s not that a federal or state government can provide train service to western MA at a cost that’s substantially lower than a private company (though they might – Medicare’s aggressive audit process helps keep costs down by minimizing waste.) It’s more that transportation has ancillary financial benefits that are hard for anyone other than a state to claim.

Real estate in Boston is insanely expensive, either to buy or to rent. That’s because lots of people want to live and work in Boston and the supply of real estate is relatively scarce compared to demand. In much of the rest of Massachusetts (let’s say, anywhere west of I-495), jobs are relatively scare and real estate is plentiful. Cities like Worcester, Holyoke, Springfield, Greenfield and Pittsfield experienced peak population decades ago and have been on the decline ever since. These cities and their surrounding communities are nice places to live, though they suffer from a shrinking population and tax base.

If there were a high-speed rail corridor from Boston to Albany, through Worcester, Springfield and Pittsfield, we would expect real estate in those cities to become more valuable as people fed up with Boston rents moved to smaller cities and the countryside, using high speed rail to commute to schools and jobs. This would have the salubrious effect of increasing the tax base for the most vulnerable communities in MA, though it might decrease the tax base in the most densely settled parts of Massachusetts. Then again, lowered density might be a good thing – few people stuck on I-90 or I-93 on their way into Boston on a Monday morning think the city and its suburbs works especially well at current density.

This model of rail turning undesirable land into desirable land is basically the model that enabled westward expansion during the 19th century – the US government and rail companies struck a deal that shared ownership of land along the new rail lines. Railroad companies sold land to new immigrants and to those willing to trade urban density for rural opportunity to finance their construction, and the government used revenues from land sales to fill public coffers.

But western MA is not unclaimed land. High speed rail will make some landowners wealthy while leaving others relatively untouched. The only entity that can capture the value generated by an infrastructural improvement like high speed rail is a government – local, state or federal – which can claim a share of those increased property values through taxation. If high speed rail makes it possible to live in Springfield and work in Boston, it might – over time – generate enough traffic to make running the service profitable. In the short term, however, we’d see Springfield better able to pay for schools and public services, a not insignificant development for a community that’s facing severe economic problems.

Who loses? Residents of Boston and surrounding suburbs. We’d expect rents and property values to decrease somewhat as demand lessens. And we’d be generating public debt through a bond issue, much as when citizens throughout Massachusetts subsidized the Big Dig, despite the fact that the massive infrastructure project did little to benefit residents of Pittsfield, on the other side of the state. We would be engaged in a transfer or wealth from the wealthiest part of our state to some of the poorest, hoping that, in the long run, our poorer communities would become more self-sufficient and sustainable, and would do a better job of supporting the state as a whole.

Is such an investment worthwhile? I don’t know – it’s the sort of issue one would expect to debate, trying to determine whether future spending is likely to generate significant enough economic gains that a long term investment is worthwhile. But we seem to be losing the ability to have these long-term debates. Experts warn of crumbling infrastructure throughout the US, as exemplified by broken bridges and collapsing freeways. A quick trip to any city in the Middle East or Asia is a stark reminder of how antiquated most of our public transit systems are, in those places where they exist.

The US has a problem with public goods. After thirty years of hearing that government can do nothing right and that the private sector is inevitably more efficient, my generation and those younger tend not to look towards the government to solve problems. Instead, we look to the private sector, sometimes towards social ventures that promise to turn a profit while doing good, more often towards fast-growth private companies, where we hope their services will make the world a better place. Google can feel like a public good – like a library, it’s free for everyone to use, and it may have social benefits by increasing access to information. But it’s not a public good – we don’t have influence over what services Google does and doesn’t provide, and our investment is an investment of attention as recipients of ads, not taxation.

It’s unthinkable for most Americans to posit a government-built Google, as the French government proposed some years ago. But it’s likely that long established parts of our civic landscape, like libraries and universities, would be similarly unthinkable as public ventures if we were to start them today. (You want to lend intellectual property at zero cost to consumers who might copy and redistribute it, and you’d like local government to pay for it? What sort of socialist are you?!)

This unwillingness to consider the creation of new public goods restricts the solution space we consider. We look for solutions to the crisis in journalism but aren’t willing to consider national license models like the one that supports the BBC, or strong, funded national broadcasters like NHK or Deutsche Welle. We build markets to match consumers with health insurance but won’t consider expanding Medicare into a single-payer health system. We look towards MOOCs and underpaid lecturers rather than considering fundamental reforms to the structure of state universities. We consider a narrow range of options and complain when we find only lousy solutions.

My student Rodrigo Davies has been writing about civic crowdfunding, looking at cases where people join together online and raise money for projects we’d expect a government to otherwise provide. On the one hand, this is an exciting development, allowing neighbors to raise money and turn a vacant lot into a community garden quickly and efficiently. But we’re also starting to see cases where civic crowdfunding challenges services we expect governments to provide, like security. Three comparatively wealthy neighborhoods in Oakland have used crowdfunding to raise money for private security patrols to respond to concerns about crime in their communities. Oakland undoubtably has problems with crime, in part due to significant budget cuts in the past decade that have shrunk the police force.

It’s reasonable that communities that feel threatened would take steps to increase their safety. But if those steps focus only on communities wealthy enough to pay for their own security and don’t consider broader issues of security in the community, they are likely to have corrosive effects in the long term. Oakland as a whole may become more dangerous as select communities become safer. And people paying for private security are likely to feel less obligation to paying for high-quality policing for the city as a whole if they feel that private security is keeping them safe – look at the resentment people without kids and people whose kids are homeschooled or in private school express towards funding public schools.

On the one hand, I appreciate the innovation of crowdfunding, and think it’s done remarkable things for some artists and designers. On the other hand, looking towards crowdfunding to solve civic problems seems like a woefully unimaginative solution to an interesting set of problems. It’s the sort of solution we’d expect at a moment where we’ve given up on the ability to influence our government and demand creative, large-scale solutions to pressing problems, where we look to new technologies for solutions or pool our funds to hire someone to do the work we once expected our governments to do.

Jen Pahlka and Clay Shirky at Code for America Summit

I’m at Code for America’s 2013 summit in San Francisco today, an impressive gathering put together by an extremely impressive civic innovation organization. I’m one of the advisors to Code for All, a sister project to Code for America led by Catherine Bracy, old friend from the Berkman Center, and was able to meet the first Code for All partners from Jamaica, Germany and Mexico at CfA’s amazing headquarters yesterday.

Code for America has done something pretty astounding. They’ve found a way to bring geeks into local governments to build innovative new projects in a way that’s fiscally sustainable. They’ve got support from the governments who host these geeks and from the central players in the US tech economy, and they’ve emerged as a central organizing node for the government innovation community.

Jen Pahlka, the founder of Code for America, opens her remarks with the classic Margaret Mead “Never doubt that a small group of people can change the world” quote, and admits that she never got her degree in anthropology because the classes were too early in the morning. She notes that many people working on civic change feel like they are a small group, though we’re able to come together into a movement today. She hopes that this isn’t a movement of sameness, but of diversity, which sometimes creates conflict and chaos. When we come together, we get new applications and APIs, but more importantly, we get a community and a common mission.

The common beliefs of this group include the idea that government can work of the people, by the people and for the people, even in the 21st century. We have in common the idea that we can do things better together. Code for America welcomes anyone who has these values, and – and here she emphasizes her words very carefully – are doing something. Code for America is a reaction to Tim O’Reilly’s injunction to the tech industry to “work on stuff that matters”. CfA, she tells us, works on the stuff that matters the most.

Jen is supposed to be working as deputy CTO under Todd Park in the White House on a yearlong break from the organization… though she’s on furlough at the moment. She explains her decision to move into government for a year by explaining how inspired she is by people working in government. “In order to honor all of you – all the public servants in government and the fellows to work with them – I felt like I could not pass up this experience.”

Answering the inevitable question: “How’s it going in DC?”, she answers that it’s both deeply rewarding and the hardest thing she’s ever done, including starting Code for America. She offers warm thanks to Bob Sofman and Abhi Nemani who’ve been leading the organization during her year off.

Clay Shirky start his talk at the Code for America summit with some internet history:

Larry Sanger is an epistemologist, hired into one of the few epistemology jobs, working on Nupedia, a new encyclopedia working with experts to build a carefully fact-checked new encyclopedia. Nine months into Nupedia, they’ve created about a dozen articles. Sanger realizes this isn’t working and goes to Jimmy Wales, the guy who hired him, and suggests using Ward Cunningham’s wiki software. Wikipedia is born and the rest is history – in weeks, it outpaces Nupedia and Nupedia rapidly shuts down.

Patrick McConlogue, a New York city entrepreneur who works at Kickass Capital, caught sight of a homeless guy on the streets of New York and proposes teaching him to program as a way of addressing the problem of “the unjustly homeless”. McConlogue never bothered to learn the homeless guy’s name, and the details of the story led to ferocious online criticism of McConlogue’s plans to teach a homeless man to program. In the criticism of McConlogue, Shirky was struck by the idea that tech startups encourage thinking that doesn’t consider limitations and constraints, which might be appropriate for the tech industry, but doesn’t work well in the social change space.

This sounded wrong to Shirky, who started re-reading the comments through this lens, looking both at the criticisms of McConlogue’s idea and the voluminous criticism of Leo, the homeless guy, for being homeless. Matt Yglesias was similarly skeptical, but looked at possible solutions: how do we address homelessness, which begins with looking for ways to create affordable housing. Clay draws a distinction between this sort of helpful criticism – which was very harsh to McConlogue’s approach, but ultimately helpful – and corrosive criticism, which doesn’t make you smarter but just tries to get you to stop looking at the problem.

Clay notes that he’s lived through two sorting out times: the question of whether the web would be important, and questions of whether social media would spread. In these periods of sorting out, technology looks like a solution in search of a problem, because at that point it is. Over time, we find answers to the question – will it work? will it scale – and it ultimately does. Clay suggests that we’re now at that point with civic media. We need to listen to the helpful critics, and we need to stop listening to the corrosive ones so we can keep moving forward.

“If you want to feel like a genius, go to a place where people are doing something new and predict that they’ll fail. You’ll almost always get it right. It’s a cheap high.” There’s a great deal of space between “nothing will work” and “almost nothing will work”. The easiest problems to take on, Clay tells us, are pure technical problems where you just need information. It’s not an accident that applications to report potholes are the great success story in this space – there’s no pothole lobby. Potholes are projects and they have solutions.

One step up from technical problems are managerial problems. In starting a bike sharing program in New York, the organizers posted a map and asked people to request bike stations. The resulting map, where everyone requested a station outside their homes, was a rhetorical document that helped build support for the program. Managerial problems don’t just solve technical problems – they have to do with building support and constituencies for solutions. And then there are political problems.