Ethan Zuckerman's Blog, page 23

August 29, 2013

Citizen science versus NIMBY?

There are ten graduate students associated with the Center for Civic Media, half a dozen staff and a terrific set of MIT professors who mentor, coach, advise and lead research. But much of the work that’s most exciting at our lab comes from affiliates, who include visiting scholars from other universities, participants in the Media Lab Director’s fellows program and fellow travelers who work closely with our team.

Two of those Civic affiliates are Sean Bonner and Pieter Franken of Safecast. Safecast is a remarkable project born out of a desire to understand the health and safety implications of the release of radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in the wake of the March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Unsatisfied with limited and questionable information about radiation released by the Japanese government, Joi Ito, Peter, Sean and others worked to design, build and deploy GPS-enabled geiger counters which could be used by concerned citizens throughout Japan to monitor alpha, beta and gamma radiation and understand what parts of Japan have been most effected by the Fukushima disaster.

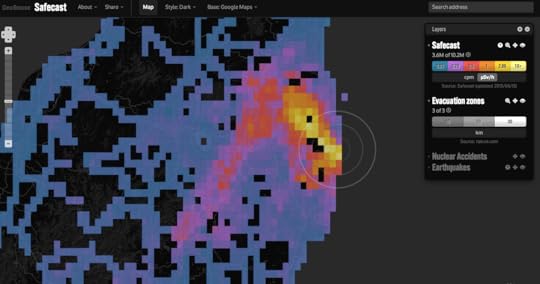

The Safecast project has produced an elegant map that shows how complicated the Fukushima disaster will be for the Japanese government to recover from. While there are predictably elevated levels of radiation immediately around the Fukushima plant and in the 18 mile exclusion zones, there is a “plume” of increased radiation south and west of the reactors. The map is produced from millions of radiation readings collected by volunteers, who generally take readings while driving – Safecast’s bGeigie meter automatically takes readings every few seconds and stores them along with associated GPS coordinates for later upload to the server.

It’s hard to know what an appropriate response to the Safecast data is – Safecast is careful to note that there’s no consensus about what’s “safe” in terms of radiation exposure… and that there’s questions to be asked both about bioaccumulation of beta radiation as well as exposure to gamma radiation. Their work provides an alternative set of information to official government statistics, a check on official measurements, which allows citizen scientists and activists to check on progress made on cleanup and remediation. This long and thoughtful blog post about the progress of government decontamination efforts, the cost-benefit of those efforts, and the government’s transparency or opacity around cleanup gives a sense for what Safecast is trying to do: provide ways for citizens to check and verify government efforts and understand the complexity of decisions about radiation exposure. This is especially important in Japan, as there’s been widespread frustration over the failures of TEPCO to make progress on cleaning up the reactor site, leading to anger and suspicion about the larger cleanup process.

For me, Safecast raises two interesting questions:

- If you’re not getting trustworthy or sufficient information from your government, can you use crowdsourcing, citizen science or other techniques to generate that data?

- How does collecting data relate to civic engagement? Is it a path towards increased participation as an engaged and effective citizen?

To have some time to reflect on these questions, I decided I wanted to try some of my own radiation monitoring. I borrowed Joi Ito’s bGeigie and set off for my local Spent Nuclear Fuel and Greater-Than-Class C Low Level Radioactive Waste dry cask storage facility.

Monroe Bridge, MA is 20 miles away from my house, as the crow flies, but it takes over an hour to drive there. Monroe and Rowe are two of the smallest towns in Massachusetts (populations of 121 and 393, respectively) and are both devoid of any state highways – two of 16 towns in Massachusetts with that distinctively rural feature. Monroe, historically, is famous for housing workers who built the Hoosac Tunnel, and for a (long-defunct) factory that manufactured glassine paper. Rowe historically housed soapstone and iron pyrite mines. And both now are case studies for the challenge of revitalizing rural New England mill towns.

Yankee Rowe, prior to decommissioning

But from 1960 to 1992, Rowe and Monroe were best known for hosting Yankee Rowe, the third commercial nuclear power plant built in the United States. A 185 megawatt boiling water reactor, Yankee Rowe was a major employer and taxpayer in an economically depressed area… and also a major source of controversy. I was in school at Williams College, 13 miles from Yankee Rowe, when the NRC ordered the plant shut down in 1991, nine years before its scheduled license renewal, over fears that the reactor vessel might have grown brittle. The plant was a source of fascination for me as a student – the idea that a potentially dangerous nuclear power plant was so nearby led to a number of excursions, usually late at night, to stare at a glowing geodesic dome (the reactor containment building) from across the Sherman Reservoir.

Since 1995, Yankee Rowe has been going through the long process of decommissioning, with the goal of returning the site to wilderness or to other public uses – the plant’s website features an animated GIF of the disassembly process. But there’s a catch – the fuel rods. Under the Nuclear Waste Policy Act, spent fuel was supposed to start moving from civilian power plants like Yankee Rowe to underground government storage facilities in 1989. That hasn’t happened. Fierce opposition from Nevada lawmakers and citizens to storing the waste at Yucca Mountain and from people who don’t want nuclear waste traveling through their communities enroute to storage facilities have meant that there’s no permanent place for the waste.

During the decades nuclear waste storage has been debated in Congress, more waste has backed up, and Yucca Mountain would no longer accomodate the 70,000 metric tons of waste that needs storage. The Department of Energy is now planning on an “interim” disposal site, ready by 2021, in the hopes of having a permanent disposal site online by 2048. The DOE needs the site, because companies like Yankee are suing the US government – successfully – to recover the costs of storing and defending the spent fuel in giant above-ground casks. (Yankee’s site has a great video of the process of moving these fuel rods from storage pools into concrete casks, a process that involves robotic cranes, robot welders and giant air bladders that help slide 110 ton concrete casks into position.)

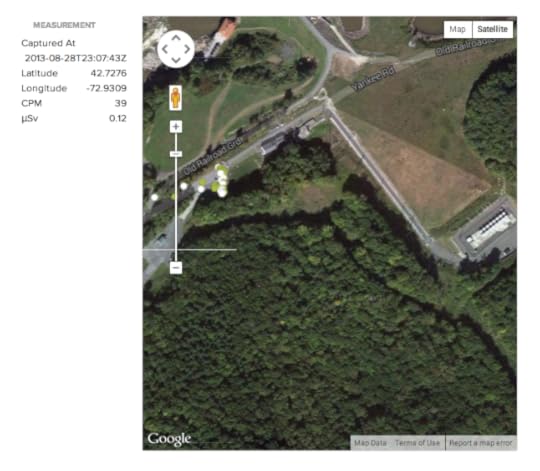

So… at the end of a twisty rural road in a tiny Massachusetts town, there’s a set of 16 casks that contain the spent fuel of 30 years of nuclear plant operation, and those casks probably aren’t going anywhere for the foreseeable future. So I took Joi’s geiger counter to visit them.

I’d been to Yankee Rowe before, and remembered being amused by the idea of a bucolic nuclear waste facility. The folks involved with Yankee Rowe have worked very hard to make the site as unobtrusive as possible – it’s marked by a discrete wooden sign, and the only building on site looks like an overgrown colonial house. Not visible from the road is the concrete pad where the 16 casks reside, but it’s 200 meters from the road and 400 meters from “downtown” Monroe Bridge.

I was curious whether I’d be able to detect any radiation using the Safecast tool. Sean and Pieter pride themselves on the fact that the bGeigie is a professional grade tool and routinely detects minor radiation emissions, like a neighbor who had a medical test that involved radioisotopes. I drove to Yankee Rowe late yesterday afternoon, took the bGeigie off my truck (it had been collecting data since I turned it on in Greenfield, the closest big town) and tried to get as close as I could to the casks.

That turned out to be not very close. Before I had time to read the NRC/Private Property sign, I was met at the gate – the sort of gate you expect to see at a public garden, not a barbed-wire, stay out of here gate – by two polite but firm gentlemen, armed with assault rifles and speaking by radio to the control center that had seen my truck over the surveillance cameras, make clear that I was not welcome beyond the parking lot.

That said, I got within 300 meters of the casks. And, as you can see from the readings – the white and green circles on the map – I didn’t detect any radiation beyond what I’ve detected anywhere else in Massachusetts. That’s consistent with the official reports on Yankee Rowe – dozens of wells are monitored for possible groundwater contamination, and despite a recent scare about Cesium 137, there’s been no evidence of leakage from the casks.

It would have been a far more exciting visit had I somehow snuck past the armed guards and captured readings from the casks suggesting significant radiation emissions, I guess… though what it would demonstrate is that you probably shouldn’t sneak in and stand too close to those casks. Better might have been to use Safecast’s new hexacopter-mounted drone to fly a bGeigie over the casks, though I can only imagine what sort of response that might have prompted from the guards.

While I’m reassured that there’s no measurable elevated levels of radiation at Yankee Rowe, it still seems like a weird state of affairs that Yankee’s waste is going to remain on a hillside by a reservoir for the foreseeable future, protected by armed guards. (The real estate listings for property owned by Yankee Atomic Energy Corporation are pretty wonderful – “Special Considerations: An independent spent fuel storage installation (ISFSI) associated with the previous operation of the Yankee Rowe Plant is located in the former plant area and remains under a U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission license. Future ownership of the 300 meter buffer surrounding the ISFSI will be negotiated as part of the property disposition.”)

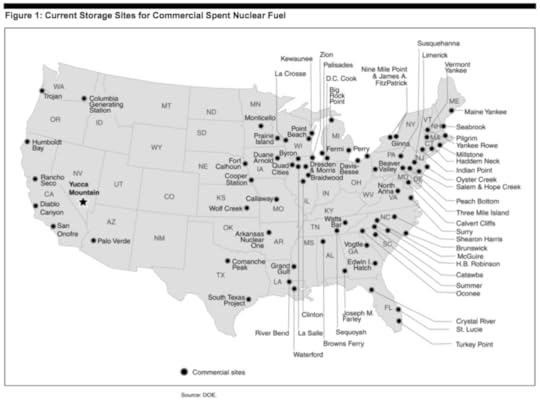

And there’s lots of sites like Yankee Rowe that already exist, and more on the way. The map above, from Jeff McMahon at Forbes, shows sites in the US where nuclear fuel is stored in pools or dry casks. And more plants are shutting down – Yankee Rowe’s sister plant, Vermont Yankee, announced closure this week to speculation that nuclear plants aren’t affordable given the low cost of natural gas. Of course, given the realization that cleaning up Yankee Rowe has cost 16 times what the plant to build and will continue until the waste is in a permanent repository might give natural gas advocates pause – will we have similar discussions of the problems of remediating fracking sites in a few years or a few decades?

Projects like Safecast – and the projects I’m exploring this coming year under the heading of citizen infrastructure monitoring – have a challenge. Most participants aren’t going to uncover Ed Snowden-calibre information by driving around with a geiger counter or mapping wells in their communities. Lots of data collected is going to reveal that governments and corporations are doing their jobs, as my data suggests. It’s easy to track a path between collecting groundbreaking data and getting involved with deeper civic and political issues – will collecting data that the local nuclear plant is apparently safe get me more involved with issues of nuclear waste disposal?

It just might. One of the great potentials of citizen science and citizen infrastructure monitoring is the possibility of reducing the exotic to the routine. I suspect my vague unease about the safety of nuclear waste on a hillside is similar to the distaste people feel for casks of spent fuel passing through their towns on the way to a storage site. I feel a lot more comfortable with Yankee Rowe having read up on the measures taken to encase the waste in casks, and with the ability to verify radiation levels near the site. (Actually, being confronted by heavily armed men also reassures me.) I’m more persuaded that regional storage facilities are a good idea than I was before my experiment and reading yesterday – my opinion previously would have been based more on a kneejerk fear of radioactivity than consideration of other options. (The compact argument: if we’ve got fuel in hundreds of sites around the US, each protected by surveillance cameras and security teams, it seems a lot more efficient to concentrate that problem into a small number of very-well secured sites.)

If the straightforward motivation for citizen science and citizen monitoring is the hope of making a great discovery, maybe we need to think about how to make these activities routine, an ongoing civic ritual that’s as much a public duty as voting. Monitoring a geiger counter that never jumps over 40 counts per minute isn’t the most exciting experiment you can conduct, but it might be one that turns a plan like Yucca Mountain into one we can discuss reasonably, not one that triggers an understandable, if unhelpful, emotional reaction of “not in my backyard.”

August 19, 2013

The “good citizen” and the effective citizen

With Rewire out in the world, I’ve had some time this August to think about some of the big questions behind our work at Center for Civic Media, specifically the questions I started to bring up at this year’s Digital Media and Learning Conference: How do we teach civics to a generation that is “born digital“? Are we experiencing a “new civics”, a crisis in civics, or just an opportunistic rebranding of old problems in new digital bottles? My reading this summer hasn’t given me answers, but has sharpened some of the questions.

Earlier this summer, I was invited by the Mobilizing Ideas blog to react to Biella Coleman’s excellent book, “Coding Freedom“. In my response, I noted that Coleman’s ethnography of hacker culture makes clear her hacker friends aren’t the stereotypical geeks, surgically attached to their computers, sequestered in their parents’ basement – they go to conventions, write poetry, and engage in political protest, as well as writing code.

The sort of hackers Biella documents engage in politics, and when they do, they’ve got multiple tools they can use. They organize political campaigns and lobby congresspeople, as Yochai Benkler and colleagues so aptly documented in this recent paper on resistance to SOPA/PIPA. They can write code that makes a new behaviors possible, like Miro, written by the Participatory Culture Foundation, which makes peer to peer filesharing and search easier and more user-friedly. They protest artistically, as with Seth Schoen’s DeCSS haiku (which prominently features in Biella’s writing.)

Hackers engage in instrumental activism, seeking change by challenging unjust laws. They engage in voice-based activism, articulating their frustration and dissent from systems they either cannot or are not willing to exit. But hackers aren’t merely competent activists in Biella’s account – they are able to engage in civics in a more broad way than most citizens. In addition to traditional channels for civic engagement, they can engage by creating code, giving them a more varied repertoire of civic techniques than non-coders have. (We might make the same argument for artists, who may be more effective in spreading their voices than those of us with less artistic talent.)

I’ve been thinking about Biella’s hackers in the context of some ideas from Michael Schudson. Schudson is a brilliant thinker about the relationship between media and civic engagement, the question that currently shapes my work at the Center for Civic Media. In his book “The Good Citizen”, and this 1999 lecture, Schudson challenges the idea that a good American citizen is one who carefully informs herself about politicians, their positions and the issues of an election. Schudson argues that this is an unrealistic expectation for citizens, pointing to the absurdity of 200 page Voter’s Guides to Elections that, he argues, nobody reads. (I know for a fact that danah boyd not only reads them, but holds parties to get people to read them with her.) But he also argues that this model of the “informed citizen” is only one model of American citizenship the republic has experienced since its foundation.

In “The Good Citizen”, Schudson explores four models of citizenship the US has passed through in the last two centuries and change. When the nation was founded, citizenship was restricted to a small group of property-owning white men, and elections didn’t focus on issues, but elected men of high status and character, who went on to deliberate in Congress with similar social elites. In the age of party politics, Schudson argues, politics was a carnival, with votes based on personal loyalties and social alliances, not on consideration of the issues.

Not until the Progressive reformers attacked corruption in the party system (an attack which included support for prohibition of alcohol, as party bosses were often tavern owners and the ability to supply voters with drink was a key political technique) did the notion of the informed voter come into play. Progressives, through adoption of the secret ballot, the introduction of referenda and the rise of muckraking investigative journalism, shifted responsibility for politics from a small group of elites and party bosses, to the general public. Schudson observes that the general public hasn’t been especially excited by this shift – participation in elections fell sharply during the progressive era and has been below 50% of eligible voters since.

Now, Schudson argues, we are living in an era where change through elections is less important than change through the courts, an age that began with the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 60s. Informed citizens are important, but their power to make change comes from suing as much as it comes from voting, and activists and lawyers who understand how to challenge constitutionality through the court system are far more powerful than the average citizen.

While he’s critical of the informed citizen model as unrealistic, Schudson is not arguing for the superiority of the rights-based model, or for a return to party bosses. He’s pointing out that America has experienced different visions of what constitutes “the good citizen” and that these visions can change over time.

That’s helpful context for understanding Biella’s hackers. We may be experiencing a shift in citizenship where the idea of the informed citizen no longer applies well to the contemporary political climate. The entrenched gridlock of Congress, the power of incumbency and the geographic polarization of the US make it difficult to argue that making an informed decision about voting for one’s representative in Congress is the most effective way to have a voice in political dialogs.

Instead, we’re seeing activists, particularly young activists, taking on issues through viral video campaigns, consumer activism, civic crowdfunding, and other forms of civic engagement that operate outside traditional political channels. Lance Bennett suggests that we might see these new activists as A HREF=”http://rebooting.personaldemocracy.co... citizens, focused on methods of civic participation that allow them to see impacts quickly and clearly, rather than following older prescriptions of participation through the informed citizen model.

Biella’s hackers are exemplars of self-actualizing citizens, using code as one of their paths towards self-actualization, alongside traditional political organizing and lobbying. Larry Lessig’s Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, a book deeply popular with the hackers Biella studies, offers the possibility that these are only two of four paths towards civic engagement and change.

Lessig’s book is written as a warning about possible constraints to the open internet. While many contemporary scholars warned that the lawless internet would come under control of national and local governments, Lessig warned that it would also be regulated through code, which would make some behaviors difficult or impossible to accomplish online. Lessig outlines four ways complex systems tend to be regulated:

- By laws, created and enforced by governments, which prohibit certain behaviors

- By norms, which are created by or emerge from societies, which favor certain behaviors over others

- By markets, regulated and unregulated by laws, which make certain behaviors cheap and others expensive

- By code and other architectures, which make some behaviors difficult and others easy to accomplish

These four methods of regulation are also ways in which activists and other engaged citizens can participate in civics. Citizens frustrated and angered by NSA surveillance of domestic communications, for example, could lobby Congress to hold hearings on whether the NSA has overstepped its bounds, or whether FISA courts are providing sufficient oversight of government surveillance requests. Civic coders could build tools that make use of PGP encryption easier to protect the privacy of emails. Citizens could punish companies that have complied with surveillance requests and reward those who are moving servers outside of the US to make them more surveillance resistant. And people could begin using Tor and PGP routinely, to influence norms of behavior around encryption and make the NSA’s techniques significantly less effective.

These methods are often applied to non-technical issues as well. Social entrepreneurship uses market mechanisms to seek change, paying farmers a fair wage for their coffee, for instance, by buying from collectives rather than from exploitative wholesalers. Social media campaigns focus on harnessing attention and changing norms, bringing underreported issues to wider audiences. Using code to make government more transparent or more effective is a popular, if possibly overhyped, approach to social change. These models may represent a complement to the informed citizen and rights-based citizenship models Schudson examines, representing new civic capabilities in addition to the capability of influencing laws and governments.

Mastering these four capabilities is a tall order for any civic participant, but some activists are trying. Julian Assange has technical skills, as well as a deep understanding of media, which has allowed him to cooperate and compete for attention in working to change norms around secrecy and whistleblowing. His long run from prosecution has sharpened his understanding of legal systems, and, until the financial “blockade” against Wikileaks, he seemed to be doing reasonably well raising money for his project. (My friend Sasa Vucinic, involved with anti-Milosevic radio station B92 and founder of the Media Development Loan Fund, argues that the key to running a successful anti-government newspaper is to get the funding model right and build a sustainable media outlet.) Edward Snowden has proved extremely technically savvy, legally astute and has had an excellent relationship with the global press, essential to gain a wide audience for his revelations.

Schudson’s portrait of citizenship through the ages focuses on the behavior of large groups of citizens. Assange and Snowden are too idiosyncratic to serve as exemplars of a new class of digitally engaged citizens, promoting a new vision of citizenship. But they demonstrate what a highly competent, multifaceted civic participant might look like and I suspect that we will see more citizens leveraging the full suite of tools that Lessig’s structures of regulation point to.

A challenge for those of us who see the shape of civics changing is how we prepare people to participate in civics where the skills required are so diverse. If it’s difficult to expect citizens to be informed voters, as Schudson argues, it’s very difficult to expect them to be coders, entrepreneurs, lawyers and media influencers. We might hope, as Dewey does, that diverse interests will lead to an interlocking public – I care about surveillance and work to change norms, while you write code, and our friend tackles another challenge through social entrepreneurship. Or it may push us back to a democracy enhanced by expertise, as Walter Lippmann suggests, with citizens throwing fiscal and moral support to organizations that lobby for laws, write code, build just markets and influence public debate, leveraging the expertise and skill of those who dedicate their talents to one or more of these facets of citizenship.

I shared a draft of this post with Erhardt Graeff, who pointed out an inherent tension between ideas of the competent and effective citizen and the “good” citizen. The “good” citizens, in Schudson’s exploration, are those who participated in the system of the times, whether or not we see those systems as laudable in retrospect. A particularly cynical version of this idea would posit that today’s “good citizen” is a predictably partisan consumer, deviating as little as possible from the demographic predictions and models built by pollsters and data analysts to ensure that our candidates are correctly marketed to us. Highly participatory and effective citizens would challenge this sort of model, and it’s certainly possible that a democracy composed purely of Assanges and Snowdens would have a hard time functioning.

Erhardt points out that Lessig has been an activist throughout his career, and that his vision of regulation in Code is one consonant with the effective citizen. But can democracy work if all citizens are effective at promoting and campaigning for their own issues? Have we seen evidence of a society with high, effective engagement and with the other characteristics we expect of a democracy? Should a group like Center for Civic Media be working on thinking through models of effective citizenship or considering the larger question of what a large group of effective, engaged citizens could mean for contemporary visions of democracy?

August 8, 2013

Charlie DeTar dissertation defense: Intertwinkles and digital tools for consensus decisionmaking

Charlie DeTar defended his doctoral dissertation this afternoon at the MIT Media Lab. Charlie is a student in Chris Schmandt’s Mobility and Speech group, but has also been an active member of my group, Center for Civic Media, where he’s done very important work including Between the Bars, a platform that allows inmates in some US prisons to blog via the postal service. Charlie is an incredibly thoughtful guy, who takes the time to read deeply and develop nuanced understanding of issues before he builds new technologies.

His work on his doctoral thesis reflects this thoughtfulness – in building “Intertwinkles“, a platform to assist in consensus decisionmaking, Charlie conducted a deep dive into the nature of democracy, decisionmaking, group behavior and technology to assist group decisionmaking. His talk today outlined that work as context for his intervention.

Willow Brugh attended the talk and her visualization of Charlie’s remarks is below. My notes follow below her illustration.

Charlie’s remarks start with the question: “How much democracy do you have left?”

He shows a photo series of people holding papers with X marks on them – the marks represent the number of presidential elections the person expects to have left. The message – we don’t have very much democracy, if democracy means voting every four years. “Most of us wouldn’t volunteer to be governed by kings or dictators,” Charlie offers, but we face lots of non-democratic rule in real life: bosses, landlords, banks, other powerful institutions we have little influence over.

High profile, democratically-governed activist organizations tend to have short lifespans. Even long-lasting movements like Occupy tend to be relatively short lived. But collectives and cooperatives use highly participatory methods and many have been in existence for decades. Twinkles – the practice of waving your fingers to show approval, non-verbally, for a statement – is a practice that originated in the 1970s and thrives today within collectives and cooperatives. But the in-person nature of collective and cooperative governance can be slow, expensive and draining. Charlie’s core research question is whether we can design online tools for democratic consultation which result in more just and effective organizations.

To answer this question, Charlie has build a set of tools to support consensus decision-making processes, documenting the participatory design process used to develop the tools and evaluated these tools in their use by real-world groups. He’s also done deep investigative work exploring the history of non-hierarchicalism, consensus, and decisionmaking with computers.

Non-hierarchicalism looks like a simple concept at first glance – it represents forms of governance that are decentralized, flat, leaderless, or horizontal. But questions immediately arise: are facilitators imposing a covert hierarchy?

Charlie suggests we consider decentralization, using a definition from Yochai Benkler: in decentralized systems, many agents work coherently despite the fact that they do not rely on reducing the number of people participating in decisionmaking. While the number of people does not decrease, most decentralized systems require some centralization, as Charlie discusses by examining multiple models. The blogging platform WordPress is decentralized because you can download, customize and run the code, effectively becoming a chapter or franchise for WordPress. With Wikipedia, different sets of people work on different problems, editing different articles, in what can be thought of as a subsidiary model. In BitTorrent, rather than decentralizing resources, the founders have declare a protocol that determines how we interact, enabling decentralization through federation.

Each decentralization has a corresponding centralization:

- Bittorrent decentralizes servers via a centralized protocol

- WordPress decentralizes hosting via a centralized codebase

- Wikipedia decentralizes editors through a centralized database and policies

- Consensus decentralizes authority through centralizing procedures

Consensus decisionmaking is a field of governance, Charlie tells us, that works to avoid three tyrannies:

- The tyranny of the majority, when the mob beats you up

- The tyranny of the minority, where small group prevent functioning or dominate decisionmaking

- The tyranny of structurelessness, where elimination of overt structure leads to covert structure via dominant personalities, racism, sexism and other forms of dominance.

Consensus decisionmaking is the process of consulting stakeholders in a way that seeks to avoid these tyrannies. Charlie outlines seven forms of consensus, including corporate, scientific, standards, consociationalism (power-sharing), mob, assembly, focusing specifically on affinity consensus, groups of people who’ve chosen to work together on problems of common interest. He offers a matrix for how each form of consensus handles open membership, egalitarianism, formal process, and the binding nature of decisions. For instance, a corporate department that practices consensus decisionmaking still has a boss, and may not always make binding decisions. Not all groups are open – if I want to participate in the decisionmaking of Charlie’s housing cooperative, I’m going to be refused admission.

In the process of building Intertwinkles, Charlie has developed a long list of protocols that people use to enable consensus decisionmaking, including various facilitation tools, meeting phases, hand signals, roles and formats. Intertwinkles implements several of these protocols in an online environment.

To understand the history of digital tools to assist with decisionmaking, Charlie takes us back to J.C.R. Licklidder, who talked about decisionmaking with computers as early as 1962. Douglas Englebart, whose “mother of all demos” introduced many of the ideas that have dominated the next 50 years of computing, began developing methods of computer-aided decisionmaking in the late 1960s. The field was formalized as “group decision support systems”, generating a huge amount of scholarship around three systems, generally dedicated computing systems installed in “decision-support rooms” at corporations and universities. While these systems were very engineering-heavy, they often used very similar techniques to those used in consensus-oriented groups. However, it is difficult to extrapolate from the scholarship, because the vast majority of studies used artificial, composed groups, not groups with existing histories and patterns. Most were face to face and most were one-shot experiments. These methodological limitations make it hard to extrapolate to understand the utility of these tools for affinity groups, which have important existing relationships, group histories and policies.

Charlie notes that these early group decisionmaking support tools tended to provide all services – including email – to their users, because they were huge, expensive systems that often represented an organization’s first exposure to digital communication. Now systems are smaller and decentralized, including tools like Doodle (used for meeting scheduling) and Loomio, a new system designed to support discussion of proposals in forums and voting on those proposals.

While these systems are promising, Charlie hopes we can do more. He notes that Joseph McGrath put forward a helpful typology of group tasks in his 1984 book, Groups, Interaction and Performance. Ideally, we’d want a system that helps groups engage in each of these tasks – generating ideas, generating plans, executing tasks, etc.

Intertwinkles began as a participatory design project with Boston cooperative housing groups. Charlie recruited six houses from 29 collective and cooperative housing groups and hired three research assistants who were “native participants”, residents in the houses. 45 people participated, overall.

The groups he worked with were involved throughout a field trial process, from pre-interviews to help understand how groups made decision, through an extensive training session on the tools and for 8-10 weeks of usage, as Charlie and his team iterated to improve the tools with feedback from users. The process involved both the creation of new tools and a pair of games designed to inspire conversation and reflection on group dynamics, Flame War (which models decisionmaking over email) and Moontalk (a realtime game that models limited communication channels). More information on both games is available on the Intertwinkles site.

Charlie offers brief overviews of three tools. Dotstorm is based around sticky note brainstorming, and supports visual thinkers through stickies with drawings and with photos taken through laptops or other devices. The system supports real-time collaboration and sharing of ideas and runs on any contemporary web browser. Resolve supports a rolling proposal process, which allows one member of a group to propose an idea and others to expand, refine or block it, eventually voting on accepting it. The system maintains a rich history of a proposal and uses a notification system to keep participants involved in the process, but lets participants use email as their channel for free-form discussion. Points of Unity is a tool designed to help come up with a short list of values or statements that a group agrees with, which many groups find useful as a mutually agreed-upon common ground.

Many of the features of Intertwinkles are platform features shared across tools. There’s a group-centric sharing model that gives people access to documents and resources once they join the group. Membership is reciprocal (like membership in Facebook) and overlapping (you are friends with everyone in the group), a model that Charlie hasn’t seen in Facebook, Twitter or other systems. Everything is shared publicly for discrete periods of time, which lowers the barrier to entry to the system, but then reverts documents to private to avoid spam, etc. Users can take actions on behalf of other members of the group, recognizing that not everyone is active online constantly. There is rich, semantic event reporting, which allows for a “quantified group” analysis, understanding and describing a group’s behavior in quantifiable terms about participation. Intertwinkles is built on a plug-in architecture. Core services handle search, authentication, twinkles, events, notices, groups – other features plug into those core services, which makes it possible to develop radically new tools without building up the other essential components.

For the system to work, Charlie believes that participants need extensive training. What’s key is getting to the point where everyone is confident that everyone else is comfortable with the tools. To remind collectives of the tool, Charlie distributed a colorful pillow, a Twinkle Plush Star, as “an ambient reminder of the system and its uses.”

Five of the six groups used the tool, completing 66 processes and making 2155 unique edits and visits. One group didn’t use Intertwinkles beyond training, and one reported neutral to negative experiences, while the other four groups had generally positive reactions. Charlie measured the participation of each cooperative member with the system because he worried there might be uneven participation. His analysis suggests quite even participation, similar to what you might get face to face.

In examining how collectives used the system, Charlie reminds us of the idea of “technology in action”, proposed by proponents of structuration theory. This theory suggests that designers build tools for certain tasks, but the tools get used for whatever tasks a group wants to carry out, which leads to unexpected outcomes, sometimes contrary to designer’s intentions. Charlie makes his intentions clear: he wanted to make non-participation apparent, to increase awareness of conflict, to make group processes explicit, and to handle facilitation “out of band”.

He sees a correlation in satisfaction with the tool and group structure. Groups that had more confrontive approaches to decisionaking and more formal approaches to decisionmaking had better results with the tools. The group that was least satisfied tends to be avoidant of conflict and privileges action over speaking. A group that found the tools most useful makes participation in house meetings mandatory, has explicit channels for communication on conflict, and extensive house norms. This highly structured group was able to take advantage of the system in ways less structured groups did not.

Charlie sees room to improve the tools: more work on in-band facilitation, in-band training,instrumenting the platform for online learning, and building an ecosystem of developers. He plans to continue working on the tool and already sees possible alliances to build the platform in conjunction with others building tools for group decisionmaking. But he also sees value in the theoretical approach, suggesting that design research is powerful as a form of sociology and a potential quantitative and qualitative method for studying group behavior.

August 6, 2013

On MIT’s report on Aaron Swartz’s prosecution

Hal Abelson’s report on MIT’s actions around Aaron Swartz’s prosecution was released last week. I was on vacation and offline – I returned home Sunday and read the report and some of the responses to it.

I certainly see why Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman called it a whitewash. For those hoping that Abelson and his colleagues would identify faults in MIT’s behavior and take responsibility for inaction, the report is deeply disappointing. One of the strongest statements in the report makes in conclusion is, ultimately, quite weak:

“…let us all recognize that, by responding as we did, MIT missed an opportunity to demonstrate the leadership we pride ourselves on.”

That’s a bit of an understatement. The report includes an entire section (Part IV) on opportunities MIT missed, places where MIT could have intervened and might have helped prevent a tragedy. While the report correctly notes that we can’t know how things would have turned out had MIT responded to Robert Swartz’s repeated requests for the Institute to make a statement similar to the one JSTOR made, it’s clear that MIT didn’t just miss an opportunity – it consciously and repeatedly decided not to take any actions that would have helped Aaron Swartz make a successful defense while cooperating fully with requests from prosecutors.

As such, I don’t think the report is a “whitewash”. I don’t think Abelson is trying to conceal details that cast MIT in a bad light – it’s hard to read the report without being deeply disappointed with how MIT makes decisions. By my reading, the report documents a troubling culture of leadership at the university, one where adherence to the (ultimately flawed) idea of “neutrality” overrides making a nuanced decision about how to respond to aggressive prosecution under a poorly written law.

There’s lots I’m angry about with the report. It ends with questions for the MIT community to consider, rather than recommendations. This isn’t the fault of Abelson and colleagues, but the ambit given Abelson by MIT’s President, Rafael Reif. While the report makes clear that MIT cooperated more thoroughly with prosecutors than with Aaron’s defense (and carefully explains why MIT’s “neutral” stance ends up favoring the side that had more power in the equation), it doesn’t lay blame on MIT’s general counsel or any other individuals for MIT’s failure of leadership.

For me, the biggest disappointment is a refrain throughout the report that blames the MIT community for failing to draw more attention to Swartz’s prosecution. In Part V, the authors note, “Before Aaron Swartz’s suicide, the community paid scant attention to the matter, other than during the period immediately following his arrest. Few students, faculty, or alumni expressed concerns to the administration.”

It’s certainly true that there was more anger and attention in the wake of Aaron’s suicide than there was during the indictment and period leading towards trial. But it’s not true that the community was unaware of Aaron’s plight. As the report documents, Joi Ito, director of MIT’s Media Lab, asked MIT’s leadership to see if Aaron’s case could be settled as a “family matter” within the MIT community. Two other faculty members spoke to the administration and Robert Swartz, who works for the Media Lab, approached MIT multiple times, seeking a statement that MIT did not believe Swartz should be prosecuted for his actions.

There are reasons why those of us who were aware of Aaron’s case didn’t lobby MIT more loudly. As the report notes, just following the statement about “scant attention”: “Those most familiar with Aaron Swartz and the issues that greatly concerned him were divided in their views of the propriety of his action downloading JSTOR files, and fearful of harming his situation by taking public or private stands.” This fear was compounded by the fact that it was very difficult for Aaron and those closest to him to talk about the case without creating communications that could be subpoenaed by the prosecutor, which led him to discuss the case with very few people. Also, as the report reveals, an early attempt to draw action to the case online led to an angry reaction from prosecutor Steve Heymann. Given that Aaron and his team were seeking a plea deal with a prosecutor who already escalating charges against Aaron, it’s understandable that people were worried about harming Aaron’s situation by making noise.

Blaming the MIT community’s lack for response for MIT’s studied inaction is, for me, is an embarrassing evasion of responsibility, an admission that MIT was less interested in doing the right thing than in avoiding the sort of negative publicity it faced when it failed to support Star Simpson when she faced prosecution for wearing an LED-enhanced hoodie to Logan Airport.

It’s helpful to understand why MIT’s leadership did what it did. It’s understandable that, before they knew who was accessing JSTOR that they sought help from the Cambridge PD, which ended up bringing the Secret Service into the case. But for well over a year, MIT knew that its network had been accessed by a committed activist who was most likely making a political statement, not attempting to sell JSTOR to the highest bidder. They were extensively lobbied by a long-time employee who made a simple request for MIT to make a statement similar to the statement JSTOR made. They heard from MIT professors and from scholars outside the community, yet they clung to a stance of neutrality that, as Abelson’s report notes, systematically favored the prosecution over the defense.

The New York Times reports that MIT was “cleared” of wrongdoing in Aaron Swartz’s prosecution and death. I think the report presents MIT with two equally serious charges: a failure to act ethically, and a failure to show compassion. According to Abelson’s report, MIT’s president, chancellor and Office of the General Counsel did the minimum – and sometimes less than the minimum, when they failed to respond to defense subpoenas – in allowing Aaron Swartz and his team to mount a defense. In the process, they ignored the pleas of a long-time colleague who was desperately working to defend his son.

MIT has a different president than it did for most of the Swartz case, and the ball is now in President Reif’s court to change a culture that was unwilling to take moral leadership in the case of Aaron’s prosecution. For those of us who are outraged by the inaction of MIT’s leadership in this case, we face Albert Hirschman’s famous choice: exit or voice. My friend Quinn Norton, Aaron’s partner when he was arrested, recently tweeted: “I will never work with MIT, I will never attend events at MIT, I will never support MIT’s work, and I hope dearly that my MIT friends leave.”

I would hope that there’s another option: making clear that members of MIT’s community believe that MIT has responsibilities beyond “neutral” compliance, and working to change the culture that so badly failed Aaron. Evidently, it’s up to the MIT community – and the broader internet community – to make sure this report isn’t the final word on MIT’s role in Aaron’s prosecution and to ensure that Abelson’s questions in the report do not remain unanswered. I hope that President Reif’s promise to engage with Abelson’s questions leads to real change in an institution that has much to answer for, and I plan to push as hard as I can from the inside to ensure that MIT’s response to Aaron’s death does not end with this report.

July 27, 2013

See you in a couple of weeks

I’m on vacation for the next two weeks, taking a break from a long stretch of writing and talking about Rewire and related issues. I should be back online around August 10. In the unlikely event you find yourself missing me, here’s the video of a talk and discussion I had about Rewire at Harvard’s Berkman Center last month.

And if you’re in need of more reading material, check out an important new paper from Yochai Benkler, Hal Roberts and other friends at the Berkman Center. The paper uses Media Cloud to analyse the conversation online around SOPA/PIPA and understand agenda-setting, framing and relationships that influenced the debate. My students and I are finishing up a parallel paper at Center for Civic Media using some of the same techniques, and some new techniques, to examine the online debates that helped lead to George Zimmerman’s arrest, which we hope to have out in early fall.

Hope you’re having a great summer.

July 10, 2013

Surveillance, sousveillance and PRISM – an op-ed for Die Zeit

Friends at Die Zeit, who heard me speak at a panel about “Cameras Everywhere” at Personal Democracy Forum, asked me to write an op-ed for their newspaper. That piece ran today, translated into German. Here’s the English version I wrote just before the “Restore the 4th” protests in Washington DC and elsewhere.

Revelations about the extent of the US government’s surveillance of digital media has triggered a range of reactions around the world. In the world outside the US, citizens and their governments are rightly furious that the National Security Agency is systematically monitoring communications on some of the world’s most widely used communications platforms. That the US apparently spies on its closest allies in EU offices merely adds insult to injury.

The reaction within the US to these revelations has been disappointingly subdued. Civil libertarians and advocates for free speech online are struggling to productively channel their anger and are planning a major protest in Washington DC on July 4. But more widespread responses include a nodding acceptance of any invasion of privacy in exchange for prevention of terrorist violence, and a cynical, world-weary insistence that no one should be surprised that all digital networks are monitored both by corporations and by governments.

As a frustrated advocate for unfettered online speech, I find myself looking for ways to help my fellow Americans understand the significance of pervasive online surveillance. Unlike in Germany, where memories of the Stasi trigger an instinctive resistance to being watched, surveillance in the US has often focused on marginal political groups, which allows many Americans to assume that surveillance doesn’t affect them personally. This search for ways to make surveillance more apparent has led me to the work of Dr. Steve Mann and his work on “sousveillance”.

Mann is a professor at the University of Toronto, and an innovator in the world of wearable computers. In 1981, as a student at MIT, he created the first generation of EyeTap, a head mounted camera that recorded what the wearer saw and presented a computer-enhanced view of the scene. More than thirty years before Google Glass, Mann began living life while wearing a camera, recording all that he encountered, an experience that’s given him some deep insights into watching and being watched.

Mann coined the term “sousveillance” – watching from below – as an alternative to “surveillance” – watching from above. In surveillance, powerful institutions control the behavior of individuals by watching them or threatening to watch them, as in Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon. In sousveillance, individuals invert the paradigm by turning their cameras on institutions, promising to document and share misbehavior and malfeasance with a potentially global audience through digital networks.

One effect of sousveillance is to provoke conversations about what it means to be watched. Even when surveillance is visible, as in the CCTV cameras that loom over many of our city streets, most of us tend to ignore the unseen watchers who monitor us. But when someone points a camera at us – particularly a camera mounted on their eyeglasses – we react, often with anger or dismay. Mann, who wears his EyeTap permanently attached to his head, was assaulted in a McDonalds in Paris by employees who were upset that he was taking pictures and who sought to force him to remove the camera.

We may need similar provocations to trigger our reactions to online surveillance. “Creepy”, a program by Ioannis Kakavas, can track an individual’s movements on a map through her postings on social media services. While Creepy was intended as an activist project, commercial programs use similar techniques. A controversial iPhone application, Girls Around Me, mines data on Foursquare to alert men looking for dates to locations in their cities where many women have checked in. Angry reactions to these programs, as well as reports of bars preemptively banning patrons from wearing Google Glass suggest that Mann’s idea of making surveillance both personal and visible may be a first step in provoking a discussion about what types of watching are appropriate and inappropriate.

There’s a second aspect of sousveillance that’s worth exploring: the idea that individuals may be able to keep the powerful in check by documenting misbehavior. While this idea can seem hopelessly naïve when confronted with systems as massive and pervasive as PRISM, it’s worth exploring cases where watching from below has helped fight abuses of power. Morgan Tsvangirai’s appointment as prime minister of Zimbabwe in 2009 was a direct result of his party’s technique of photographing voting tallies at each polling station, enabling a parallel tabulation of votes. Confronted with evidence that Tsvangirai had beaten Mugabe in the first round, Mugabe’s government was unable to rig the election and was forced into a power-sharing agreement with Tsvangirai, the opposition leader.

More recently, activists in the Occupy Movement have used livestreaming of video as a technique to document their protests and police violence against protesters. Dozens of cameras captured footage of Lt. John Pike attacking seated protesters with pepper spray at a peaceful Occupy protest at UC Davis. The widely documented incident led to the UC Davis police chief and two officers being suspended and to Lt. Pike losing his job, and created one of the most powerful images of the power asymmetries the Occupy movement sought to confront.

Pervasive cameras can document the inner workings of institutions as well as abuses of power. Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney suffered a major campaign setback when video showed him dismissing 47% of the American electorate as unlikely to vote for him because they “believe they are victims” and are dependent on government services. The video, secretly shot by Scott Prouty at a fundraising event, was posted online and widely distributed by Democratic activists, who saw the video as evidence that Romney was out of touch with the electorate.

Most recently, sousveillance has shown its power in documenting protest movements in Turkey and Brazil that were initially ignored by mainstream media. In Turkey, CNN famously showed a documentary about penguins rather than footage from Gezi Park, leading protesters to make signs that show penguins wearing gas masks, protesting both the government’s use of tear gas and the media’s silence about the protests. In the absence of broadcast media attention, the protesters used their own documentation to find audiences online, spreading protests from those in the park to those who witnessed online and began protests in their corners of the country.

The Obama administration seems unlikely to shift policy on online surveillance without widespread and sustained popular outcry. As activists seek to trigger that outcry, we may need to make surveillance far more visible so it can become far more controversial.

July 8, 2013

Facebook, Reddit and what “social media” means

I have a brief piece on The Atlantic’s website today that contrasts Facebook and Reddit in terms of how they build online communities and direct their users to new content. I argue that Reddit, with the assumption of anonymity and an organization around topics and sections has some resemblance to the Internet of the 1980 and 90s, while Facebook has changed the shape of internet communities, demanding real-name registration and building online social networks that mirror our offline networks. By paying attention to social media communities that work along the Reddit model as well as those that follow the Facebook model, I hope that people can increase their cognitive diversity and expose themselves to a wider range of ideas, opinions and perspectives.

My friend Anthea Watson Strong pointed out on Twitter that Reddit is an odd example to use when talking about cognitive diversity. It has a reputation for being white, male, young and American… and that reputation is not unjustified. (This study of US Reddit users by Pew’s Internet and American Life Project suggests that the audience is broader and larger than we might think – in particular, I was surprised to see the large reach with Latino youth.) In Rewire, I spend a decent amount of time beating myself up for my Reddit habit, pointing to my tendency to return to the site as an example of seeking out familiar, comfortable voices rather than seeking diversity.

So why the praise for Reddit? I’m not trying to argue that Reddit is superior to Facebook, or that Reddit is the solution to problems of increasing cognitive diversity. But Reddit is a good example of a site that’s reached a large audience by using a different model of community than Facebook’s model of real-name, real-world network community. Other examples include Twitter (which features asymmetric following, no assumption of real name, and support for topic-based organization through lists), and Wikipedia (which features communities based around common practice and collaboration and a citizenship model for participation).

My argument isn’t even against Facebook’s ordering of community, though I think it reinforces homophily effects that plague offline communities. It’s for people building new internet tools to consider the idea that there are multiple ways of building an online community, and that different communities have different strengths and weaknesses. The people you meet by exploring a common topic is different than the group of people you meet by migrating your offline social network online. I worry that when we talk about “social media”, we talk too much about networks that work like Facebook and not enough about networks that work like Reddit or like Wikipedia. In particular, I see a lot of tools that are using social networks to customize search and use only a narrow definition of social network to look for recommendations and inspirations.

Commenting on my piece, David Aron Levine notes, “This article by @EthanZ on Reddit highlights as much a latent demand for something more as it does Reddit”. Yep – that’s right. I like Reddit and use it (as a lurker, as my dismal karma numbers will show), but what I’d really like to see is a wave of new communities organized around different ideas of what it means to be social. Some might connect people around topics of common interest, as Reddit does. Others might bring people together around a common project, as Wikipedia does. I’d particularly like to see – or perhaps build – a community that helps people discover each other via a common interest but emphasizes connecting people who would be highly unlikely to meet in the physical world, or who come from very different backgrounds.

Would love your thoughts on who’s doing good work defining online community in terms other than “people I know in the physical world” and how these communities can help people discover information online.

July 3, 2013

Me and my metadata – thoughts on online surveillance

The NSA documents Edward Snowden leaked have sparked a debate within the US about surveillance. While Americans understood that the US government was likely intercepting telephone and social media data from terrorism suspects, it’s been an uncomfortable discovery that the US collected massive sets of email and telephone data from Americans and non-Americans who aren’t suspected of any crimes. These revelations add context to other discoveries of surveillance in post 9-11 America, including the Mail Isolation Control and Tracking program, which scans the outside of all paper mail sent in the US and stores it for later analysis. (The Smoking Gun reported on the program early last month – I hadn’t heard of it until the Times report today.)

The Obama administration and supporters have responded to criticism of these programs by assuring Americans that the information collected is “metadata”, information on who is talking to whom, not the substance of conversations. As Senator Dianne Feinstein put it, “This is just metadata. There is no content involved.” By analyzing the metadata, officials claim, they can identify potential suspects then seek judicial permission to access the content directly. Nothing to worry about. You’re not being spied on by your government – they’re just monitoring the metadata.

Of course, that’s a naïve and oversimplified view of metadata, which turns out to be a surprisingly rich source of information on who people are, who they know and what they do. Congress has historically recognized that metadata is important and deserves protection – while the Supreme Court ruled in Smith vs. Maryland that phone numbers dialed should not be expected to be private information, as they are exposed to the phone company, Congress put restrictions on the use of “pen registers”, devices that can track what calls are made and received by a phone, requiring law enforcement to go to court to institute such tracking. The same logic in Smith vs. Maryland applies to the Mail Isolation Control and Tracking program – since information on envelopes is visible to the public, or at least to mail carriers, it’s monitorable and storable, even without “mail covers“, US Postal Service administrative orders used to trace mail coming to criminal suspects. And, perhaps, the policymakers who approved NSA’s surveillance projects would argue that the logic applies to email headers as well.

Put aside for the moment the question of whether monitoring metadata is reading public information or is more analogous to a pen register. There’s a scale issue that comes into play here. One major constraint on pen registers and mail covers historically has been the sheer amount of data they generate. Potential overreach by law enforcement is held in check by two factors – the need to get court or administrative approval to trace metadata, and the ability to process said metadata. As a result, USPS insiders report that it processes about 15,000 – 20,000 mail covers a year related to crime, and as security researcher Chris Soghoian discovered, internet and telecommunications companies charge law enforcement agencies for pen registers, putting some practical limits on their use.

But the NSA surveillance of email and phone networks, and the Mail Isolation Control and Tracking program have no such limits. While it’s likely quite expensive to scan all US mail, once you’ve committed to doing so, it’s comparatively cheap to store that information and analyze it at later dates, as investigators evidently did to arrest Shannon Richardson for sending ricin to President Obama and New York City mayor Bloomberg. And, since the costs of NSA surveillance are evidently borne primarily by internet and telephony companies, it’s downright cheap to keep metadata on email and phone calls. All the postal mail, email and phone calls.

It’s also much, much cheaper to analyze this data than in years past. The current frenzy for “big data” and “data science” has called attention to techniques that allow analysts to pull subtle patterns out of data – a New York Times story that suggests that retailer Target was able to identify pregnant customers based on their purchasing behavior (unscented lotion!) and target ad flyers to them gives a sense for the commercial applications of these techniques.

Sociologist Kieran Healy shows another set of applications of these techniques, using a much smaller, historical data set. He looks at a small number of 18th century colonists and the societies in Boston they were members of to identify Paul Revere as a key bridge tie between different organizations. In Healy’s brilliant piece, he writes in the voice of a junior analyst reporting his findings to superiors in the British government, and suggests that his superiors consider investigating Revere as a traitor. He closes with this winning line: “…if a mere scribe such as I — one who knows nearly nothing — can use the very simplest of these methods to pick the name of a traitor like Paul Revere from those of two hundred and fifty four other men, using nothing but a list of memberships and a portable calculating engine, then just think what weapons we might wield in the defense of liberty one or two centuries from now.”

If you are a member of a secret organization planning overthrow of the government, you’ve probably already thought hard about what your metadata might reveal. But if you’re an average citizen with “nothing to hide”, it may be less obvious why your metadata may not be something you are comfortable sharing. After all, Frank Rich recently proclaimed that “privacy jumped the shark in America long ago” and that we are all members of “the America that prefers to be out there, prizing networking, exhibitionism, and fame more than privacy, introspection, and solitude.” Lured by reality television and social networks, we all want to be watched and have therefore have given up our distaste for surveillance.

I think it’s possible to be both a heavy user of social media, and concerned about the security of your metadata. It simply requires understanding that, for many of us, social media is a performance. When I share links on Twitter, I’m aware that I’m constructing an image to my followers as someone who’s interested in certain topics and disinterested in others. I don’t share every article that I read, both because I suspect not all are interesting to my followers and also because I don’t really want my professional community to know just how much mental energy I spend worrying about who the Green Bay Packers will field at running back in the coming season.

This may not be how you use social media, but it probably should be. As danah boyd and others have pointed out, youth have had to figure out how to navigate a world in which their interpersonal and social interactions are archived, searchable and persist long enough to present a problem in adulthood – as a result, they’re continually engaged in “identity performance”, as well as in developing codes and other ways to speak on social networks to defy monitoring.

By contrast, most of us aren’t maintaining a persistent, public performance when we’re using telephones or email. (For an example of what this might feel like, consider this story from This American Life, where lawyers who work with Guantanamo detainees talk about how having the US government monitor their personal phone calls changes their behavior.) Our metadata can reveal things we may not want to share with others, or may not know ourselves.

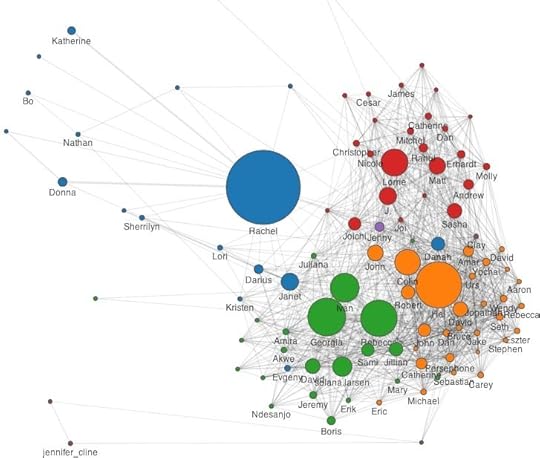

As it happens, I have a pretty good sense for what my email metadata might tell an investigator. This fall, I co-taught a class with Cesar Hidalgo, Catherine Havasi and Sep Kamvar at the Media Lab titled “Big Data”. Two of the students who took the class, Daniel Smilkov and Deepak Jagdish, worked on a project called Immersion which uses Gmail metadata to map someone’s social network. I’m one of about 500 alpha testers of the software, developed by Cesar, Daniel and Deepak, and have been one of the poster boys for the project as it’s been on display at the Media Lab, as I’ve got the largest network of Gmail contacts of anyone who’s used the system. (This isn’t because I’m especially popular, I suspect. Most of my MIT colleagues use mit.edu addresses. As someone new to MIT, who maintains a number of different affiliations, I have been a heavy Gmail user.)

Here’s what my metadata looks like:

The largest node in the graph, the person I exchange the most email with, is my wife, Rachel. I find this reassuring, but Daniel and Deepak have told me that people’s romantic partners are rarely their largest node. Because I travel a lot, Rachel and I have a heavily email-dependent relationship, but many people’s romantic relationships are conducted mostly face to face and don’t show up clearly in metadata. But the prominence of Rachel in the graph is, for me, a reminder that one of the reasons we might be concerned about metadata is that it shows strong relationships, whether those relationships are widely known or are secret.

The other large nodes on the graph are associated with specific clusters. Rebecca is my co-founder at Global Voices and Ivan and Georgia run the organization day-to-day – they dominate the green cluster, which includes key people in that organization. Hal is my chief collaborator at the Berkman Center, and Colin is my boss – they dominate the orange cluster, which includes fellow Berkman folks as well as a number of prominent internet law and policy folks who work closely with the Center. Lorrie is assistant director at Center for Civic Media and is the person I work with most closely at MIT – the red cluster represents the people I work with at the Media Lab.

Anyone who knows me reasonably well could have guessed at the existence of these ties. But there’s other information in the graph that’s more complicated and potentially more sensitive. My primary Media Lab collaborators are my students and staff – Cesar is the only Media Lab node who’s not affiliated with Civic who shows up on my network, which suggests that I’m collaborating less with my Media Lab colleagues than I might hope to be. One might read into my relationships with the students I advise based on the email volume I exchange with them – I’d suggest that the patterns have something to do with our preferred channels of communication, but it certainly shows who’s demanding and receiving attention via email. In other words, absence from a social network map is at least as revealing as presence on it.

Another sensitive piece of information comes from how Immersion draws and codes clusters. Immersion’s algorithm is sensitive to who you include on the same email. Global Voices emails include Ivan, Georgia, Rebecca and others – people who I email when I email those three get placed in the same cluster. People who exist as bridges between clusters are particularly interesting, as they are people who appear in multiple roles in your social network. Joi Ito appears on my graph twice (as “Joi” and “Joichi”) because he uses multiple email addresses, but in either role, he’s a bridge between my MIT existence, my Global Voices existence and my Berkman life, which reflects my long and multi-faceted relationship with him. But he’s colored red, as a Media Lab person, whereas other bridge figures like danah boyd show up as blue, as they have close relationships with Rachel as well. In other words, I have important, long-standing, multifaceted relationships with both danah and Joi, but danah is part of my family life as well, while Joi is not.

My point here isn’t to elucidate all the peculiarities of my social network (indeed, analyzing these diagrams is a bit like analyzing your dreams – fascinating to you, but off-putting to everyone else). It’s to make the case that this metadata paints a very revealing portrait of oneself. And while there’s currently a waiting list to use Immersion, this is data that’s accessible to NSA analysts and to the marketing teams at Google. That makes me uncomfortable, and it makes me want to have a public conversation about what’s okay and what’s not okay to track.

While popular outcry over revelations about the NSA has been somewhat muted so far, it’s possible that widespread protests planned for July 4th will spark more dialog about what represents unconstitutional surveillance. Here’s hoping that conversation will take a close look at metadata and ask hard questions about whether or not this is information we are willing to share with governments and corporations, or whether we need to regulate and limit this power to monitor as we’ve historically done in the United States. Restore the Fourth.

For another example of what metadata may reveal, see Malte Spitz’s phone records. As I discuss in “Rewire”, Spitz sued his mobile phone provider to obtain his records, then worked with Zeit Online to build a visualization of his movements based purely on that set of data.

July 2, 2013

Tracing Brazil’s Guy Fawkes Masks

Early this morning, Reddit user “SlartiBartRelative” posted a photo, with the headline “The icon of anti-capitalism, mass-produced”. The post received thousands of upvotes and generated a long comment thread, though the most highly-rated comment argued “Those masks have nothing to do with anti-capitalism… like at all”. Other commentators note that Anonymous, which has famously adopted the Guy Fawkes mask, is anti-corruption or anti-tyranny, which may sometimes manifest itself as anti-corporatism, which can look a lot like anti-capitalism. (There’s also a helpful discourse on the historical Guy Fawkes. Yay, Reddit comment threads!)

I saw the image as it started appearing on Twitter, usually with a comment about irony or despair that a protest symbol was mass-produced under less-than-salubrious conditions:

There’s been a good bit written about the Guy Fawkes mask. Friend and colleague Molly Sauter has the definitive article, tracing the mask from Alan Moore’s comic book, back to Catholic revolutionaries, then forward through Epic Fail Guy, 4chan, Anon and to Occupy. But she doesn’t dwell at length on anti-capitalism, focusing more on masks, anonymity and collective identity. Leo Benedictus, writing in The Guardian, explores the irony that the mask, created for the movie version of “V for Vendetta”, provides licensing revenue to Warner Bros.

Later this morning, Business Insider published an article that borrows heavily from an article by Fabricio Provenzano for Extra Online, a Brazilian newspaper published by the massive Organizações Globo media group. Provenzano’s article, published ten days ago, suggests that the manufacturers are selling directly to protesters, with individuals coming to the factory to pick up hundreds of masks at a time, orders that are significantly larger than those made by wholesalers or distributors. The article doesn’t address the issue of licensing, but suggests that the factory is used to producing mass runs of masks for Carnival, and has also received designs for masks that parody Brazilian politicians, likely also for use in protests as well as in Carnival processions.

The impression I took from Provenzano’s article wasn’t that the factory, run by a mask company called Condal, was particularly badly run or exploitative – Provenzano was interested in the sudden surge of interest in the design. And I would be stunned if Condal were an official licensee of Warner Bros – I think it’s unlikely that money paid for thee masks is going into the pocket of a Hollywood studio as Condal seems to borrow heavily from the global entertainment industry in its mask design.

The photo of workers making Guy Fawkes masks is something of a Rorschach test. If you’re primed to see the exploitative nature of global capitalism when you see people making a plastic mask, it’s there in the image. if you’re looking for the global spread of a protest movement, it’s there too, with a Brazilian factory making a local knock-off of a global icon to cash in on a national protest.

Because the internet is a copying machine, it’s very bad at context. It’s easier to encounter the image of masks being manufactured devoid of accompanying details than it is to find the story behind the images. And given our tendency to ignore information in languages we don’t read, it’s easy to see how the masks come detached from their accompanying story. For me, the image is more powerful with context behind it. It’s possible to reflect on the irony of a Hollywood prop becoming an activist trope, the tensions between mass-production and anonymity and the individuality of one’s identity and grievance, the tensions between local and global, Warner Bros and Condal, intellectual property and piracy, all in the same image.

If you’d like a Condal-made Guy Fawkes mask, it’s available here – scroll down and look for item 101. It’s near the troll-face mask, which could also come in handy.

June 21, 2013

The price of life on Florida’s Death Row

The world is slowly moving to abolish the death penalty. Around the world, 140 countries have either abolished the punishment in law or in practice, not executing a prisoner in the past ten years. The majority of US states still permit the death penalty, but the total people sentenced to death in 2012 dropped below 100 for the first time since the late 1970s, and executions are slowing as well.

But not in Florida. The State of Florida has an unusual approach to the death penalty. They are the only state where a simple majority on a jury can vote to sentence a person to death. (In most states, unanimous agreement is required.) And they lead the nation in exonerations, where lawyers and activists uncover evidence that someone sentenced to death is innocent, according to an editorial in the Tampa Bay Times. (The figures in the editorial come from the Death Penalty Information Center, which lists 142 exonerations, with 24 from Florida.) In other words, Florida sentences a lot of people to death, and they seem to get it wrong quite often.

This situation is about to get worse. Emily Bazelon wrote a powerful article for Slate examining Florida’s new law, the “Timely Justice Act”, which requires the governor to sign death warrants within 30 days of an inmate’s final appeal, and requires the state to execute the condemned within 180 days of that warrant. That’s a lot quicker than executions are generally carried out. Inmates remain on death row in Florida for 13.2 years on average, less that the nationwide average of 14.8 years.

What’s the rush? The purpose of the bill, sponsors say, is to ensure that executions are carried out in a timely fashion, to increase public confidence in the judicial system. One of the sponsors of the bill, Florida Republican Matt Gaetz quipped, “Only God can judge. But we sure can set up the meeting.” But, as Bazelon points out, Florida’s death penalty system is so flawed that it often requires years to uncover evidence that would exonerate a death row inmate.

There’s a brutal logic behind Florida’s bill. The Death Penalty Information Center calculates that it costs Florida $51 million a year more than holding them for life, given the extra costs of extra security and maintenance costs for death row facilities. Shorter stays on death row equal lower costs – the only downside is the likelihood of killing people who might well be found innocent with years to explore their cases.

Consider the case of Clement Aguirre, on death row in Florida since 2006 for the 2004 murders of a mother and daughter found dead in their trailer home. DNA evidence obtained by the Innocence Project in 2011 strongly suggests that Aguirre is innocent of the murders, and he is still fighting to overturn his conviction.

Fixing Florida’s criminal justice system requires more than building opposition to the death penalty or funding reviews of death penalty cases through the Innocence Project. It requires providing high quality public defenders to those accused of crimes. Bazelon reports that Florida’s death penalty defenders are some of the worst in the nation, and have allowed clients to go to death row without ever meeting them or responding to their letters.