Ryan Holiday's Blog, page 24

April 21, 2017

Meet Your Worst Enemy

No matter where you are and what you’re doing, your worst enemy is always with you—your ego.

“Not me,” you think. “No one would ever call me an egomaniac.” Maybe you’ve always thought of yourself as a pretty balanced person. But for any person with ambitions, talents, drives, and potential to fulfill, ego comes with the territory. Precisely what makes us so promising as thinkers, doers, creatives, and entrepreneurs—what drives us to the top of those fields—makes us vulnerable to this darker side of our psyche.

Freud described the ego with a famous analogy—our ego was the rider on a horse, with our unconscious drives representing the animal the ego tried to direct. Modern psychologists use the word “egotist” to refer to someone who is dangerously focused on themselves, with disregard for anyone else. Each of these definitions is true enough but of little value outside a clinical setting. The ego we see most commonly goes by a more colloquial definition—an unhealthy belief in your own importance. It is, as Bill Walsh put it, “where confidence becomes arrogance.”

Most of us aren’t egomaniacs, but ego is at the root of almost every conceivable problem and obstacle we have, from why we can’t win to why we need to win all of the time—and at the expense of others.

We don’t usually see it this way. We think something else is to blame for our problems—most often, other people. We are, as the poet Lucretius put it a few thousand years ago, the proverbial “sick man ignorant of the cause of his malady.” With every ambition and goal we have—big or small—ego is there, undermining us on the very journey we’ve put everything into pursuing.

Ego is the enemy of what you want and of what you have: Of mastering a craft. Of real creative insight. Of working well with others. Of building loyalty and support. Of longevity. Of repeating and retaining your success. It repulses advantages and opportunities. It’s a magnet for enemies and errors. The second you believe in your greatness, the artist Marina Abramovic explains, that’s the death of your creative career.

Pioneering CEO Harold Geneen compared egoism to alcoholism: “The egotist does not stumble about, knocking things off his desk. He does not stammer or drool. No, instead, he becomes more and more arrogant, and some people, not knowing what is underneath such an attitude, mistake his arrogance for a sense of power and self-confidence.” You could say they start to mistake that about themselves too, not realizing the disease they’ve contracted or that they’re killing themselves with it.

If ego is the voice that tells us we’re better than we really are, we can say ego inhibits true success by preventing a direct and honest connection to the world around us. One early member of Alcoholics Anonymous defined ego as “a conscious separation from.” From what? Everything.

The ways this separation manifests itself negatively are immense: We can’t work with other people if we’ve put up walls. We can’t improve the world if we don’t understand it or ourselves. We can’t take or receive feedback if we are incapable of, or uninterested in, hearing from outside sources.

We can’t recognize opportunities—or create them— if instead of seeing what is in front of us, we live inside our own fantasy. Without an accurate accounting of our own abilities compared to those of others, what we have is not confidence but delusion. How are we supposed to reach, motivate, or lead other people if we can’t relate to their needs because we’ve lost touch with our own?

Just one thing keeps ego around—since it certainly doesn’t serve any productive purpose. It is comfort. Pursuing great work—whether in sports, art, or business— is often terrifying. Ego soothes that fear. It’s a salve to our insecurity. Replacing the rational and aware parts of our psyche with bluster and self-absorption, ego tells us what we want to hear, when we want to hear it.

But it is a short-term fix with a long-term consequence. Which is why we must fight it.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:100%;}

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Get New Posts From Ryan Holiday Sent Right To Your Inbox

February 6, 2017

Why Ego is The Greatest Opponent to Your Creativity and Success (And How to Fight Back)

We all have goals: We want to matter. We want to be important. We want to have freedom and power to pursue our creative work. We want respect from our peers and recognition for our accomplishments. Not out of vanity or selfishness, but of an earnest desire to fulfill our personal potential.

While we hold up humility as an admirable trait, the problem is that we’re not sure it can get us to the goals above. We are petrified as the Reverend Dr. Sam Wells put it, that if we are humble, we will end up “subjugated, trodden on, embarrassed, and irrelevant.”

I’ve spent the last two years working on a book about ego, and I’ve heard some version of this paradox from many people. They would nod vigorously in agreement with me that ego was bad, that it destroyed creativity and happiness, that they knew plenty of toxic egomaniacs who had wrecked themselves. And then they would say, “But a little bit of ego is still important though, right?”

Even people who despise ego and aspire to humility, who plan to be humble once they are successful, are worried that actually enacting those beliefs would sentence them to a life of obscurity or weakness or failure.

Allow me to address that fear right now: One does not need to be an egotistical asshole to be successful. In fact, this is one of the most misleading and destructive myths in all of Western culture, right next to the idea that one must be a drug addict to be a successful musician or starving to produce great art.

The idea that only the swaggering, all-knowing, and ruthlessly ambitious succeed is a lie. One that has discouraged so many people with so much potential—and worse, encouraged many more to crash and burn.

History bears shows the truth. For every Douglas MacArthur or George McClellan, brilliant but laughably convinced of their own greatness and power, there is a George Marshall, a general who accomplished far more (far more quietly) and coveted far less credit along the way. For every Paris Hilton or Kim Kardashian (who while successful are also spoiled and entitled), there is a Katharine Graham, who was born into greater wealth and did far more with it.

Ego is certainly there in many of the greatest and most dizzying tales of success—but it’s there in some of the greatest stories of failure and self-implosion as well. Howard Hughes. John DeLorean. Ty Warner. Lance Armstrong. Richard Nixon.

When creative people warn against ego, they aren’t relying on Freud’s definition or any psychiatric diagnosis. They are using the colloquial definition—referring to the dangerous inflection point where our notion of ourselves and the world grows so strong that it begins to distort the reality which surrounds us. When, as the football coach Bill Walsh explained, “self-confidence becomes arrogance, assertiveness becomes obstinacy, and self-assurance becomes reckless abandon.” It is this belief in our own greatness or specialness that can undo our creative abilities.

The reasons why ego is a career-killer instead of the killer-advantage people tell themselves it might be are two-fold:

First, the essence of creativity is a deep and continuous connection to the world around you. To product lasting and meaningful work, one must understand themselves, other people and their craft—not delusionally but intuitively. If ego is the voice that tells us we’re better than we really are, we can say ego inhibits artistic expression by preventing a direct and honest connection to the world around us. So the artist must possess a certain amount of realism because that realism is critical to great art, great writing, great design, great business, great marketing, and great leadership.

From this connection and understanding stem all the other important parts of the puzzle—for instance, we cannot reflect truth if we’re incapable of seeing any. We cannot take or receive feedback if we are too conceited to hear it or if our own reality overpowers the objective standards we need to measure ourselves against. We cannot connect with others if our attitude and approach pushes them away—or pushes us above them. We cannot recognize opportunities—or create them—if instead of seeing what is in front of us, we live inside our own fantasy. We cannot be truly confident unless we have an accurate accounting of our own abilities. And we certainly cannot relate to, reach, motivate or compel other people to follow our lead if we’re not able to grasp their deepest and often hidden human needs.

One of the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous defined ego as “a conscious separation from.” From what? Everything and everyone—especially our audience. In other words, you can get too wrapped up in your own head.

In his recent exploration of what makes for bad art, Toby Little, put it well when he said, “Bad writing is almost always a love poem addressed by the self to the self.” Ego blocks us from hearing that. Even works of fantastical fiction and surrealism require not only knowledge of human nature and truth, but in the course of their execution will require the artist to receive, evaluate and integrate feedback if they hope to successfully deliver their message. A creative can’t get better or learn if they think they’re already perfect. Which is why we find that when it comes to the art itself—despite any bluster and marketing—the artist must be humble and dedicated and open.

Second, managing a creative career requires a connection to one’s audience as well as a network of relationships with managers, clients, bookers, agents, and other industry personnel. Ego makes the management of these relationships and the cultivation of this audience difficult, if not impossible over the long term. There is an almost unbelievable scene told in Zac Bissonnette’s fascinating biography of Ty Warner, the creative and marketing genius behind the billion dollar Beanie Baby empire. At the peak of the toy’s popularity, Warner decided to abruptly discontinue selling Beanie Babies to sell Beanie “Kids” instead. Everyone around him told him these new toys were ugly, that he was making an enormous mistake. Fearing his wrath, most employees stopped challenging him (and when they did he’d say “Who’s the billionaire here?”) On the eve of the launch, one trusted advisor stood up to him, predicting failure for this new product. Ty’s response: “I could put the Ty heart on manure and they’d buy it!” he told them.

Needless to say, “they” did not buy them. The same behavior that propelled Ty Warner to massive success also propelled him right through and out of it—in fact, he narrowly avoided going to jail just a few years later. John DeLorean, the brilliant engineer and car designer followed a similar trajectory. He was brilliant creatively, but no amount of brilliance could compensate for the destructiveness of his ego. It was ego and his inability to work well with others that drove him out of General Motors. His ego mired his new company in chaos and dysfunction. Ultimately, instead of being able to reflect on these failures and resolve them, he hatched a plan to save his company from insolvency with a $60 million dollar cocaine deal instead of, you know, anything but that.

When people say “But a little bit of ego is a good thing,” they’ve considered the matter only superficially. What they mean is that success requires a certain confidence, a faith in oneself—and in that they are correct. But it’s critical that we make the distinction between confidence and ego.

The mixed martial arts pioneer and UFC pioneer Frank Shamrock has observed that of the two, only confidence can bear weight. “Confidence is important,” he said, “But ego is something false. Humility is the way to build confidence, and ego is hugely dangerous in this sport, because if you’re running on ego you aren’t running on good clean emotions or cause and effect. You bypass it to support a false idea. It’s all garbage, the ego is garbage.”

Confidence is based on what is real—it is earned. Ego is based on delusion and wishful thinking—it is artifice. Confidence doesn’t alienate us from others. On the contrary, it allows us to relate to others better—because it has removed insecurity and fear from the equation. When you are confident you can be empathetic and vulnerable. Ego makes us an asshole. Confidence—as anyone who has ever stepped foot into any martial arts studio can tell you—has the opposite effect. Confidence is calm, compassionate, curious, careful. That is: it is all the things one needs to be creative.

And yet, we hold onto the vestige of the idea that ego is something worth retaining. We tell ourselves that we need a certain brashness to succeed, why? Fear. Pursuing great work—whether it is in sports or art or business—is often terrifying. Ego soothes that fear. It’s a salve to that insecurity. Replacing the rational and aware parts of our psyche with bluster and self-absorption, ego tells us what we want to hear, when we want to hear it.

It is a short term fix with a long term consequence. Because we know how those stories end.

Not happily. Not with cheering crowds but with jeering boos. And self-loathing. And disgrace. And self-implosion.

Think Lance Armstrong training for the 1999 Tour de France or Barry Bonds debating whether to walk into the BALCO clinic. We flirt with arrogance and deceit and in the process, grossly overstate the importance of winning at all costs. Everyone is juicing, the ego says to us, you should too. There’s no way to beat them without it, we think.

Which is why we must resist the impulse towards ego in our creative pursuits. We must suppress it early on so that we can learn and work and not be distracted. When we experience success, we must learn to replace the temptations of ego with humility and discipline. Finally, we must cultivate strength, fortitude and our own standards so that when fate turns, we’re not wrecked by failure.

To put that briefly:

Humble in our aspirations

Gracious in our success

Resilient in our failures

This post first appeared on 99U.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:100%;}

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Get New Posts From Ryan Holiday Sent Right To Your Inbox

January 12, 2017

4 Ways To Push Through Adversity and Failure Without Ego

“The future bears down upon each one of us with all the hazards of the unknown.” — Plutarch

There is no way around it: We will experience difficulty. We will feel the touch of failure. As Benjamin Franklin observed, those who “drink to the bottom of the cup must expect to meet with some of the dregs.” Or as the 49ers coach Bill Walsh says, “Almost always, your road to victory goes through a place called ‘failure.’”

All great men and women went through difficulties to get to where they are, all of them made mistakes. They found within those experiences some benefit—even if it was simply the realization that they were not infallible and that things would not always go their way. They found that self awareness was the way out and through—if they hadn’t, they wouldn’t have gotten better and they wouldn’t have been able to rise again.

For us to follow their example and push through failure we can be sure of one thing we’ll want to avoid. Ego. Unless we use this moment as an opportunity to understand ourselves and our own mind better, ego will seek out failure like true north. Unless we learn, right here and right now, from our mistakes.

During times of adversity, we need to keep in mind the four principles below to help us get back up on our feet and do so without ego, which when unleashed will only make things worse.

Alive time or dead time?

According to bestselling author Robert Greene, there are two types of time in our lives: dead time, when people are passive and waiting, and alive time, when people are learning and acting and utilizing every second. Every moment of failure, every moment or situation that we did not deliberately choose or control, presents this choice: Alive time. Dead time.

During times of failure the ego in all of us wants to complain about how the situation sucks. How it’s unfair. How we’d rather be doing just about anything else. And it’s this attitude that creates dead time we can never get back. In this way, ego is the mortal enemy of alive time.

It’s easy to be angry, to be aggrieved, to be depressed or heartbroken. Ego says: I don’t want this. I want ______. I want it my way. But this accomplishes nothing!

Let us say, the next time we find ourselves stuck: This is an opportunity for me. I am using it for my purposes. I will not let this be dead time for me. The dead time was when we were controlled by ego.

Alive time. Dead time. Which will it be?

Focus on what you can control.

Failure and rejection can be a miserable place. How do you carry on? How do you take pride in yourself and your work?

The famous coach John Wooden’s advice to his players gives the answer: Change the definition of success. “Success is peace of mind, which is a direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you made the effort to do your best to become the best that you are capable of becoming.”

That’s it. Your effort, doing the best, is what you can control. This is what you need to focus on.

Do your work. Do it well. Then “let go and let God.“ That’s all there needs to be. Recognition and rewards — those are just extra. Rejection, that’s on them, not on us.

In other words, the less attached we are to outcomes the better. When fulfilling our own standards is what fills us with pride and self-respect. When the effort — not the results, good or bad — is enough. With ego, this is not nearly sufficient — it wants recognition and validation.

Warren Buffett has said the same thing, making a distinction between the inner scorecard and the external one. Your potential, the absolute best you’re capable of — that’s the metric to measure yourself against. Your own standards. Winning is not enough. People can get lucky and win. People can be assholes and win. Anyone can win. But not everyone is the best possible version of themselves.

Don’t let ego hold sway and distract you with whether or not we are getting credit and validation. It’s far better when doing good work is sufficient.

Don’t make things worse.

People make mistakes all the time. This is all perfectly fine; it’s what being an entrepreneur or a creative or even a business executive is about. We take risks. We mess up. The problem is that when we get our identity tied up in our work, we worry that any kind of failure will then say something bad about us as a person. It’s a fear of taking responsibility, of admitting that we might have messed up.

Ego asks: Why is this happening to me? How do I save this and prove to everyone I’m as great as they think? It’s the animal fear of even the slightest sign of weakness.

“Act with fortitude and honor,” Alexander Hamilton once wrote to a distraught friend in serious financial and legal trouble of the man’s own making. “If you cannot reasonably hope for a favorable extrication, do not plunge deeper. Have the courage to make a full stop.”

A full stop. It’s not that you should quit everything. It’s that a fighter who can’t tap out or a boxer who can’t recognize when it’s time to retire gets hurt. Seriously so. You have to be able to see the bigger picture. Are you going to make it worse? Or are you going to emerge from this with your dignity and character intact? Are you going to live to fight another day?

Always love.

One of ego’s worst traits is the tendency to turn a minor inconvenience or insult into a massive sore. The wound festers, becomes infected, and can borderline kill us with the hatred and anger bubbling up. Hatred is ego embodied.

In failure or adversity, it’s so easy to hate. Hate defers blame. It makes someone else responsible. It’s a distraction too; we don’t do much else when we’re busy getting revenge or investigating the wrongs that have supposedly been done to us. Does this get us any closer to where we want to be? No. It just keeps us where we are — or worse, arrests our development entirely.

You know what is a better response to an attack or a slight or something you don’t like? Love. That’s right, love. For the neighbor who won’t turn down the music. For the parent that let you down. For the bureaucrat who lost your paperwork. For the group that rejects you. For the critic who attacks you. The former partner who stole your business idea. The bitch or the bastard who cheated on you. Love.

We find that what defines great leaders is that instead of hating their enemies, they feel a sort of pity and empathy for them. Think of Martin Luther King Jr., over and over again, preaching that hate was a burden and love was freedom. Love was transformational, hate was debilitating. “Hate,” he said “is a cancer that gnaws away at the very vital center of your life and your existence. It is like eroding acid that eats away the best and the objective center of your life.”

***

These are the behaviors and standards we need to embrace and commit to to be able to handle adversity. We will choose alive time and not let any moment go to waste. We will focus only on what we can control: exerting maximum effort at being our best selves. We will act with dignity and decorum and emerge with our character intact.

The difficulty that we are experiencing now? It is not a position we chose for ourselves, but we can push through with strength and purpose, not ego. In other words, we will not let ego turn a temporary failure into a permanent one. That’s a choice we can make.

This post appeared originally on Entrepreneur

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:100%;}

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Get New Posts From Ryan Holiday Sent Right To Your Inbox

The post 4 Ways To Push Through Adversity and Failure Without Ego appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

January 2, 2017

5 Deadly Kinds of Ego That Prey Upon Your Success

“The worst disease which can afflict business executives in their work is not, as popularly supposed, alcoholism; it’s egotism.” — Harold Geneen

You worked hard, you made some smart bets and here you are, successful. Maybe someone acquired your startup for an unbelievable sum. Maybe you’re an athlete and your team just won a championship. Maybe you’re a filmmaker and received a grant to have your film made. Maybe you just won a coveted award in your field.

After we give ourselves proper credit, our ego wants us to think, I’m special. I’m better. The rules don’t apply to me. We become entitled, controlling, paranoid, selfish, even delusional.

As Aristotle observed, “it is hard to bear the results of good fortune suitably.”

When success arrives, ego begins to toy with our minds and weaken what made us win in the first place. This is the worst thing that can happen, because things get harder as we become more successful. In sports, the schedule gets harder after a winning season, the bad teams get better draft picks, and the salary cap makes it tough to keep a team together. Taxes go up the more you make.

If you want to survive those new challenges, you must learn to fight these five manifestations of ego.

Disease of me.

Pat Riley, the famous coach and manager who led the Los Angeles Lakers and Miami Heat to multiple championships, says that great teams tend to follow a trajectory. When they start—before they have won—a team is innocent. If the conditions are right, they come together, they watch out for each other and work together toward their collective goal. This stage, he calls the “innocent climb.”

After a team starts to win and media attention begins, the simple bonds that joined the individuals together begin to fray. Players calculate their own importance. Chests swell. Frustrations emerge. Egos appear. The innocent climb, Pat Riley says, is almost always followed by the “disease of me.” It can “strike any winning team in any year and at any moment,” and does so with alarming regularity.

Once we’ve “made it,” our tendency is to switch to a mindset of “getting what’s mine.” Now, all of a sudden awards and recognition matter—even though they weren’t what got us here. We need that money, that title, that media attention—not for the team or the cause, but for ourselves. Because we’ve earned it.

Let’s make one thing clear: we never earn the right to be greedy or to pursue our interests at the expense of everyone else.

To think otherwise is not only egotistical and selfish, it’s counter-productive.

Entitlement.

With success, particularly power, comes entitlement, one of the greatest and most dangerous delusions. It doesn’t matter if you’re a billionaire, a millionaire, or just a kid who snagged a good job early. The complete and utter sense of certainty that got you here can become a liability if you’re not careful. The demands and dream you had for a better life? The ambition that fueled your effort? These begin as earnest drives but left unchecked become hubris and entitlement.

Entitlement assumes: This is mine. I’ve earned it. At the same time, entitlement nickels and dimes other people because it can’t conceive of valuing another person’s time as highly as its own. It delivers tirades and pronouncements that exhaust the people who work for and with us, who have no choice other than to go along.

Right before he destroyed his own billion-dollar company, Ty Warner, creator of Beanie Babies, overrode the cautious objections of one of his employees and bragged, “I could put the Ty heart on manure and they’d buy it!” He was wrong. And the company not only catastrophically failed, he later narrowly missed going to jail.

With success and power, more often than not, we begin to overestimate our own power. Then we lose perspective. And there begins our downfall.

Control.

Entitlement comes hand in hand with the poisonous need to micromanage and control. Your ego says: it all must be done my way—even little things, even inconsequential things.

It can become paralyzing perfectionism, or a million pointless battles fought merely for the sake of exerting its say. It too exhausts people whose help we need, particularly quiet people who don’t object until we’ve pushed them to their breaking point. We fight with the clerk at the airport, the customer service representative on the telephone, the agent who examines our claim.

To what end? In reality, we don’t control the weather, we don’t control the market, we don’t control other people, and our efforts and energies in spite of this are pure waste. Efforts and energies that would have been better spent strengthening our position, are now making it worse. A smart man or woman must regularly remind themselves of the limits of their power and reach.

Paranoia.

The Oval Office tapes of Richard Nixon offer a harrowing insight into a man who has lost his grip not just on what he is legally allowed to do, on what his job was (to serve the people), but on reality itself. He vacillates wildly from supreme confidence to dread and fear. He talks over his subordinates and rejects information and feedback that challenges what he wants to believe. He lives in a bubble in which no one can say no—not even his conscience. It made for a sad and pitiful demise from one of the world’s most prestigious and powerful positions.

Paranoia, another deadly manifestation of ego when we’ve achieved success, says: I can’t trust anyone. I’m in this totally by myself and for myself. It says, I’m surrounded by fools. It says, focusing on my work, my obligations, myself is not enough. I also have to be orchestrating various machinations behind the scenes—to get them before they get me; to get them back for the slights I perceive.

In its frenzy to protect itself, paranoia creates the persecution it seeks to avoid, making the owner a prisoner of its own delusions. “He who indulges empty fears earns himself real fears,” wrote Seneca, who as a Roman statesman witnessed destructive paranoia at the highest levels.

Believing your own story.

In 1979, football coach and general manager Bill Walsh took the 49ers from being the worst team in football, and perhaps professional sports, to a Super Bowl victory, in just three years. Looking back, he refused to indulge in telling himself a story that it was his plan all along. It would have been delusional to think that at the time, taking over a team that bad. Instead, he created of culture of excellence and instilled what he called his “standard of performance” — the behaviors and standards necessary to win.

Narrative is when you look back at an improbable or unlikely path to your success and say: I knew it all along. Instead of: I hoped. I worked. Or even: I thought this could happen. To accept the narratives we build looking back wouldn’t be a harmless personal gratification. They don’t change the past, they do have the power to negatively impact our future.

From that point, your ego makes you think that success in the future is just the natural next part of the story — when really it’s rooted in work, creativity, persistence, and luck.

Resist indulging your ego in building narratives — instead, stay focused on the task at hand, securing your base and creating success.

***

These are all instances of ego working against us—right when we’ve made it, undermining us, knocking us off balance. With recognition, achievement and success we need to find stabilizers to balance our ego and pride.

We can’t let victory make us selfish and self-centered. We need to guard ourselves from some of the greatest and most dangerous delusions: entitlement, control, and paranoia. And instead of pretending that we are living some great story, we must remain focused on the execution and on executing with excellence.

If not, ego will take it all from us.

This piece appeared originally on Entrepreneur.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:100%;}

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Get New Posts From Ryan Holiday Sent Right To Your Inbox

The post 5 Deadly Kinds of Ego That Prey Upon Your Success appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

December 28, 2016

Here’s Everything I Wrote in 2016

2016 was a busy year of writing for me (and reading—but that’s in a different post). Not only did I publish two books, and launch the new daily newsletter for DailyStoic.com, but I wrote something like 100 articles. Back of the envelop math, that comes to roughly 2 articles per week, and ~150,000 words (all in that’s probably 275,000 words not including ghostwriting). There were times where I felt a little bit like I was stretching myself too slim, but I’m actually hoping to do more, and do even better writing in the year to come.

Anyway, in case you missed any of them or are looking for something to read, I thought I would put them here—all in one place. I also recently put up a page on this site that highlights some of my favorite posts I’ve written from the last ten or so years. You can also sign up to get the posts via email when they happen by clicking here.

More to come in 2017. Enjoy!

THOUGHT CATALOG

If You Only Read A Few Books In 2017, Read These

23 Things I Learned About Writing, Strategy And Life From Tim Ferriss

The Relationship Between ‘Talk’ And ‘Work’ Is That One Kills The Other

Here’s Why I Won’t Be Exploiting My Kids On Social Media

Please, Please, For The Love Of God: Do Not Start a Podcast

37 Wise & Life-Changing Lessons From The Ancient Stoics

Sorry, Offering To Work For Free Is A Really Bad Strategy (But Not For The Reasons You Think)

16 Rules That Every Kind, Smart and Compassionate Traveler Follows When They Fly

29 Lessons From The Greatest Strategic Minds Who Ever Lived, Fought, Or Led

Hey Dad, Here Are 49 More Reasons Why You Shouldn’t Vote For Donald Trump

21 Life Lessons Learned From Some Of The World’s Greatest Sports Coaches

12 Books of Aphorisms, Sayings & Moral Reminders That Belong In Every Library

25 Ways To Kill The Toxic Ego That Will Ruin Your Life

The Moments No One Wants to Experience But Everyone Needs To Succeed

29 Pieces Of Life Changing Advice I Collected By My 29th Birthday

Don’t Follow Your Passion, It’s What’s Holding You Back

There’s Only One Way To Kill The Jealousy That’s Ruining Your Life

44 Writing Hacks From Some of the Greatest Writers Who Ever Lived

The Most Important Part of The Creative Process That Everyone Misses: A Draw-Down Period

The Best Way To Learn Is To Ask — Even The Dumb Questions

If You Do This, You Should Be Banned From Email

Don’t Say ‘Maybe’ If You Want To Say ‘No’

19 Marvelous, Unbelievable Books About The Strange History of Man and Animals

The Obstacle Really Is The Way

If You Don’t Take The Money, They Can’t Tell You What To Do

15 Short, Powerful and Provocative Books Everyone Should Read

31 Ways To Get More ‘Deep Work’ Accomplished

What Books To Base Your Life On (From Someone Who Reads A Lot)

Read This If You Just Need Someone To Give You A Chance At Your Dream Job

Did You Actually Read That? The Joy of Reading Really Really Long Books

NEW YORK OBSERVER

We Are Living in a Post-Shame World—And That’s Not a Good Thing

We Don’t Have a Fake News Problem—We Are the Fake News Problem

Want to Really Make America Great Again? Stop Reading the News.

Mike Cernovich Exclusive Interview: How This Right-Wing ‘Troll’ Reaches 100M People a Month

100 Things I Learned in 10 Years and 100 Reads of Marcus Aurelius’ ‘Meditations’

Interview: Inside the World of Influencer Marketing With a Don Draper of Social Video

The Timeless Link Between Writing and Running and Why It Makes for Better Work

When Will YouTube Deal With Its Audiobook and Podcast Piracy Problem?

The Biggest Threat to Your Success Is the Story You Tell Yourself About Success

The Difference Between NBA Stars and Flame-Outs Is the Secret to Success in Any Field

The 3 Ways Ego Will Derail Your Career Before It Really Begins

Doing the Work Is Enough: Stop Letting Others Dictate Your Worth

Hypocrites, Much? How Gawker Reported on Other Crippling Bankruptcies and Lawsuits

The Toxic Force That Poisoned the Uber and Lyft Battle in Austin

Peter Thiel’s Reminder to the Gawker Generation: Actions Have Consequences

Behind the Stunt: How a Fake Book Cover Got 5 Million Views

How Tim Ferriss Became the ‘Oprah of Audio’—Behind the Podcast With 70M-Plus Downloads

Meet the Man Who Sold Hundreds of Thousands of Books With Blank Pages in Them

Meet the Man Who Rejected Advertising and Still Runs a Profitable Media Site

Goodbye and Good Riddance: Sociopathy of Gawker and Gawker-Like Media Finally Exposed

Interview: After 11,000 Posts, This Blogger Reveals All the Problems With the Media

EXCLUSIVE: How This Marketer Created a Fake Best Seller—And Got a Real Book Deal

The Cause of This Nightmare Election? Media Greed and Shameless Traffic Worship

How Rumblr’s Marketing Agency Gamed the Media for $100k in Business

EXCLUSIVE: Meet the Social Media Genius Behind Dan Bilzerian and Verne Troyer

This Is the Hollowed-Out World That Outrage Culture Has Created

DAILY STOIC

3 Stoic Exercises That Will Help Create Your Best Month Yet

Stoicism Can Help Put Criticism In Perspective

How Does A Stoic Respond To Failure

Translating The Stoics: An Interview With “The Daily Stoic” Co-Author Stephen Hanselman

On Stoicism and Not Giving a F*ck: An Interview with Mark Manson

An Interview with the Master: Robert Greene on Stoicism

Stoicism In Professional Sports: An Interview with NFL Exec Michael Lombardi

Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking: An Interview with Oliver Burkeman

A Guide To The Good Life: An Interview With William B. Irvine

Philosophy for Life: An Interview With Jules Evans

Doing the Right Thing Can Cost You Everything

Who Is Marcus Aurelius? Getting To Know The Roman Emperor

Who Is Seneca? Inside The Mind of The World’s Most Interesting Stoic

Who Is Epictetus? From Slave To World’s Most Sought After Philosopher

BOING BOING

Here’s an ancient philosophy so simple even a 5-year-old could understand it

The fascinating and ego-killing existence of human wormholes

THE GUARDIAN

How would the Stoics cope today?

THE DAILY BEAST

Gay Talese Isn’t Alone: Why Aren’t More Books Factchecked?

99U

Do You Have to Be a Jerk to Be Successful?

CRACKED

5 “Geniuses” Who Drove Their Legacies Into the Ground

FAST COMPANY

The Crucial Thing Commencement Speakers Get Wrong About Success

How To Advance Your Career While You’re Stuck Doing Grunt Work

PSYCHOLOGY TODAY

How to Beat Perfectionism, Make Progress, and Find Happiness

ENTREPRENEUR

5 Truths of Ancient Wisdom That Will Make You a Better Entrepreneur

The 3 Ways Ego Will Derail Your Career Before It Really Begins

4 Ways To Push Through Adversity and Failure Without Ego

5 Deadly Kinds of Ego That Prey Upon Your Success

MEDIUM

7 Stoic Meditations To Get The Most Out of Today (and Life)

Here’s Why Smart People Believe The Nonsense That Trump Might Win

Here’s Why You’re The Only One Who Gets To Define What Success Is

The Maxim For Every Successful Person: ‘Always Stay A Student’

HUFFINGTON POST

Dear Dad, Please Don’t Vote For Donald Trump

Why Ego Is the Enemy in Business and in Life

MINDBODYGREEN

How To Shut Down Your Ego + Tap Into The Immensity Of Your Potential

NEWSWEEK

What’s Wrong With Today’s Media?

INC.

58 Books That Will Make You Better, No Matter Who You Are

BUSINESS INSIDER

An ancient guide to solving all work problems once and for all

The Canvas Strategy: The Quickest Way to Career Success

You’re Not Stuck, You’re Just Using Your Time Wrong

Here’s the Strategy Elite Athletes Follow to Perform at the Highest Level

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:100%;}

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Get New Posts From Ryan Holiday Sent Right To Your Inbox

The post Here’s Everything I Wrote in 2016 appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

December 15, 2016

The (Very) Best Books I Read In 2016

Every year, I try to narrow down the hundred plus books I have recommended or read down to just the three or four best. I know that people are busy, and most of you don’t have time to read as much as you’d like. There’s absolutely no shame in that–what matters is that you make the time you can and that you pick the right books when you do.

They are books that I and the 70,000 readers on my reading list email have enjoyed and learned from. If they had been all that I had read over the last twelve months, I’d have considered 2016 a successful year of reading.

Anyway, let’s get to it. Read these books!

The Years of Lyndon Johnson (4 Volumes) by Robert A. Caro and The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill (3 Volumes) by William Manchester

In January, I picked up my first book in this Caro’s series on Lyndon Johnson. It wasn’t until June that I finished my fourth, but I consider finishing all of them to be one of my proudest reading achievements. (FYI, I started with The Passage of Power, then read The Path to Power, then Means of Ascent and Master of the Senate. The order didn’t seem to matter.) It’s unquestionable to me that Caro is one of the greatest biographers to ever live. His intricate, complicated, sprawling investigation into Lyndon Johnson will change how you see power, ambition, politics, personality and justice. If there is one line that sums up the whole series it’s this: It’s that power doesn’t only corrupt. That’s too simple. What power does is reveal. It’s also easy to be disillusioned by politics right now but for me, getting lost in these Lyndon Johnson books has been a helpful and educational process. Because you learn two things 1) that things have always been complicated and confusing but they tend to turn out alright 2) that our system, whatever its flaws, can still produce good results from bad men.

After the Caro series, I started William Manchester’s equally epic three volume set on Winston Churchill (Visions of Glory, Alone, Defender of the Realm) which Robert Greene gave me as a wedding present last year. Like all truly great long reads, you learn not just about the subject but every intersecting one: the history of British peerage, the Victorian era, the British Empire, Colonialism, modern warfare, international relations, evil, the nature of genius, the effects of absent parents. The book is masterfully written about a masterful man—Churchill was a soldier, a writer, a politician, a statesman, a strategist and a true great man of history. Each book in the series is equally distinct and interesting. The first is Churchill as a young, ambitious man. The second is his time in the political wilderness, when his ego has driven him from power and into writing and thinking. The third is his time back on the world’s stage, in what was perhaps the finest hour of any empire in any era. The last book is probably the best. It features the famous bulldog version of Churchill: rescuing the troops at Dunkirk, persevering through the Blitz, vowing to fight on the landing grounds and the beaches and in the streets, whatever the cost may be. The sheer determination of this man, to take an entire country on your back and defy a horde which had overrun the European continent in a matter of months…it’s almost breathtaking to think about.

As I said, if you were to only read one thing in the next year, you could do a lot worse than either of these series. They contain dozens of books within them and will teach you about so much more than just the man they are ostensibly about. Please, please read them.

(Two bonus related recommendations: I also read Lincoln’s Virtues by William Lee Miller which was heart wrenching and amazing. I truly loved both books he wrote on Lincoln. I also wrote a paean on the joy of reading really really long books which you may enjoy)

Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike by Phil Knight

As a general rule, most new memoirs are mediocre and most business memoirs are even worse. Shoe Dog by Phil Knight is an exception to that rule in every way and as a result, was one of my favorite books of the year and favorite business books ever. I started reading it while on the runway of a flight and figured I’d read a few pages before opening my laptop and working. Instead, my laptop stayed in my bag during the flight and I read almost the entire book in one extended sitting. Ostensibly the memoir of the founder of Nike, it’s really the story of a lost kid trying to find meaning in his life and it ends with him creating a multi-billion dollar company that changes sports forever. I’m not sure if Knight used a ghostwriter (the acknowledgements are unclear) but his personal touches are all over the book—and the book itself is deeply personal and authentic. The afterward is an incredibly moving reflection of a man looking back on his life. I loved this book. It ends just as Nike is starting to turn into the behemoth it would become, so I hold out hope that there may be more books to follow. In terms of other surprising memoirs, I found JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy to be another well-written gem and despite its popularity, When Breath Becomes Air is actually underrated. It’s make-you-cry good.

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

I thought I’d read this book before but clearly they gave me some sort of children’s version. Because the one I’d read as a kid wasn’t a 1,200 page epic of some of the most brilliant, beautiful and complicated storytelling ever put to paper. What a book! When I typed out my notes (and quotes) after finishing this book, it ran some 3,000 words. I was riveted from cover to cover. I enjoyed all the stuff I missed as a kid: the Counts struggle with his faith in light of what was done to him, the Hundred Days of Napoleon’s return, his rants against technology, the criticism of newspapers, the influence of ancient philosophy, ultimately, a warning against being consumed by revenge. Please—if you’re going on a long trip or looking to check out of modern events for a while—get this book. I recommend the Penguin Classics edition.

Revenge books seemed to be a trend for me this year. I loved Michael Punke’s The Revenant, about a man who bravely challenged his fate in the wilderness just as Edmond Dantes did in prison. This year I also re-read Walker Percy’s Lancelot, a dark story of revenge and an attempt to go to the heart of evil. Less dark, but equally epic, I also loved (and raved about repeatedly) Aaron Thier’s new novel Mr. Eternity. If you read a lot of non-fiction, do yourself a favor this year and set aside some time for some serious fiction reading. You can learn just as much and be changed just as much by a truly great story as you can by any business or self-help book.

Misc.

I loved Mark Manson’s The Subtle Art of Not Giving A Fuck. There’s a reason this book is blowing up. It’s that good. Same goes for Cal Newport’s Deep Work—this book has changed my priorities and confirmed a lot of my life and work decisions. If you haven’t built up the ability to sit quietly and work with great focus to develop deep, creative insights—the next few decades are going to be very difficult for you. I really liked John Seabrook’s study of the future of music industry (and really, all creative businesses) in his book The Song Machine; Cass Sunstein’s book The World According to Star Wars is another interesting look at the economics of creative work. If you want to be scared about the next four years, pick up Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here (because, well, it may have just happened here). To balance out that depressing book, I highly recommend David Brooks’ The Road To Character, Sebastian Junger’s Tribe and Chuck Klosterman’s What If We’re Wrong.

And of course, I’ve also got lists of my favorite books from 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012 and 2011.

Enjoy and looking forward to reading with you in 2017!

The post The (Very) Best Books I Read In 2016 appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

November 16, 2016

24 Books To Hone Your Strategic Mind

Strategy isn’t something that’s taught well in school. Hell, most people probably couldn’t tell you the difference between “strategy” and “tactics” (or even know there is a difference.)

This is unfortunate, because strategy is something that is critically relevant to all of us – not just those with careers in the military. We all have goals, we all have obstacles to those goals and we all live in a world we do not control. Those things combine to create the necessity of strategy.

The better we are at it – the better we are at doing what we want and need to do.

How do I accomplish what I need to accomplish? How do I find my way, deliberately, instead of stumbling around, in a reactionary fashion? Too many of us live our lives in a sort of haze, acting without a plan or guidance. Too many of us make unnecessary mistakes (costly ones at that), because we lack the ability to craft a strategic vision and a plan.

Like I said, this isn’t exactly our fault. No one taught us explicitly how to do things differently. But the good news is that such instruction is out there. Wise thinkers have been writing and teaching strategic expertise for thousands of years. The problem is knowing where to start.

In this list I want to give you some of the best (and most accessible) books, essays and documents about strategy. Used properly they will help you craft your strategic mind. You were born to be a strategist, it’s up to you to become that destiny.

1. History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides

This book – of a long forgotten war – really functions as a biography and strategic analysis of some of the greatest minds in the history of war. We have Pericles, Brasidas, Alcibiades and many others.

The anecdotes and the stories in this book are timeless. If you make your way all the way through it, I promise you will not forget it. Because the war was so long, involved so many different countries and was so varied (sea, land, siege, politics), it basically covers every type of situation you can think of.

Think of this book as a textbook. Read it. (But it is dense so if you need some help, try this.)

2 & 3. Rules for Radicals, Reveille for Radicals by Saul Alinsky

Both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama studied Alinsky extensively as they mapped their individual paths to power. He is the real originator of the concept of community organization.

Alinsky was also a die hard pragmatist, a man who had ideals but also a sense for working with and through the system to get what he needed. In fact, his best examples in these books is actually how to use the system against itself to get what he needed. These two books are classics and woefully underrated. Read them now.

4. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert Caro

This is probably the most definitive and comprehensive narrative of power ever written.

It maps the entire career of the city planner Robert Moses. I know that doesn’t seem like a particularly illustrative case study for power and strategy but Robert Moses lived power. He controlled the expansion and the building of civilization’s most advanced and important city–and he did it because he was a strategic genius (and of course, a power addict).

This book will take weeks to read but it will stick with you forever. After you are done, I promise you will not forget or ever underestimate the importance of hidden influence, power and levers again.

4 & 5. The 33 Strategies of War, The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene

Of course, I am biased because I trained under Robert. But if I had not, these books still would have given me a priceless education (as they have for millions of other people).

Robert is a crack researcher and storyteller – he has a profound ability to explain timeless truths through story and example. You can read the classics and not always understand the lessons. But if you read Robert’s books, I promise you will leave not just with actionable lessons but an indelible sense of what to do in many trying and confusion situations. Also the extra benefit of reading Robert is that you get mini-bios of strategic geniuses like Napoleon, Edison, Machiavelli, Caesar, Cortez, and others.

6. How To Profit By One’s Enemies by Plutarch

This short essay from Plutarch is about an important strategic (and life) lesson. Our enemies and our obstacles are always teaching us. There is always some lesson or advantage we can derive from them. But we must make ourselves open to this. We must cultivate an attitude that welcomes these lessons rather than fights against them.

7. The Works of BH Liddell Hart

I recommend ALL of Hart’s books, from Strategy to Why Don’t We Learn From History to his excellent biographies of strategic geniuses like William T. Sherman.

Like Greene, Hart has the ability to communicate and explain timeless truths about strategy and power. Reading one of his books is the equivalent of reading many other primary texts because he so expertly synthesizes and communicates what lies within them. He is also eminently quotable–which makes the lessons that much easier to recall. For instance, he reduced Sherman down to a simple line: Attack along the line of least expectation, and tactically along the line of least resistance.

8. Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War by Robert Coram

Boyd was a world class fighter pilot who changed warfare and strategy not just in the air, but on the ground and by sea. His concepts pioneered the modern concept of maneuver warfare (and were used for the First Gulf War). His method of problem solving and problem analysis – known as the OODA Loop – is now used in boardrooms and everywhere else. He also perfected the art of “Getting Things Done” whether that was in war or in the bureaucracy of the Pentagon. You need to know and understand John Boyd.

9. The Book of Five Rings by Musashi

Musashi was a different kind of strategist, which is why his book is so important. Most of us won’t find ourselves leading armies anytime soon. As a swordsman, Musashi fought mostly by himself, for himself. His strategic wisdom, therefore, is mostly internal. It’s about the mindset, the discipline, and the perception necessary to win in life or death situations. He tells you how to outthink and outmaneuver your enemies. He tells you how to fend for yourself. And isn’t that precisely what so many of us need help with everyday?

10. The Prince by Machiavelli

Of course, this is a must read. Machiavelli is one of those figures and writers who is tragically overrated and underrated at the same time. Unfortunately that means that many people who read him miss the point and other people avoid him and miss out altogether. Take Machiavelli slow, and really read him. Also understand the man behind the book–not just as a masterful writer but a man who withstood heinous torture and exile with barely a whimper.

Machiavelli is a glimpse into a time when power was literal and out for public viewing–when he talks about making an example of someone, he doesn’t mean calling them out, he means putting their head on a pike. Don’t let that scare you because we’re not as far from that world as we’d like to think. Deny that at your own peril.

11. The Strategy Paradox: Why Committing to Success Leads to Failure (And What to do About It) by Michael Raynor

I don’t have a lot of modern books on this list, but this is an excellent one.

We tend to wrongly think that strategy is about coming up with a genius plan and then committing to it. In fact, this is often a recipe for disaster, particularly in business.

Though success often requires a total investment in a particular strategy, this is also the recipe for extreme failure. It’s a paradox.

Michael Raynor’s book has important thoughts on this inherent paradox as well as approaches for mitigating and avoiding it.

12. Eleven Rings: The Soul of Success by Phil Jackson

Phil Jackson is a master strategist and leader. You don’t win 13 championships in multiple cities if you’re not.

What’s interesting about Jackson’s approach is how eastern it is–he guides by giving up control, he leads by encouraging other leaders, he favors movement over resistance. He has articulated these concepts in an incredibly accessible way in his most recent book and I strongly suggest everyone read it.

13 & 14. Don’t Think of an Elephant!: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate — The Essential Guide for Progressives by George Lakoff and Words That Work: It’s Not What You Say, It’s What People Hear by Frank Luntz

These two books are the two best books of political thinking and theater from both the left and the right.

Regardless of ideologies, both are experts in influencing and leading public perception through image and words. It actually matters whether we’re talking about illegal immigrants or undocumented workers, or whether we describe the problem as climate change or global warming.

Strategists need to understand the power of language and framing–it doesn’t matter how right you are, if you lose this battle it can be impossible to rally people to your cause. Read both these books.

15. Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow

I just finished this book and, goddamn, Washington’s status as an icon shamefully understates his genius as a strategist.

The man had an impeccable intuition for timing, for gestures, for politics, for the moment to strike, not just on the battlefield but in relationships, in office and in his private life.

We must study Washington not only for his nearly unbelievable military victory over a superior British Army, but also for his strategic vision which quite literally was responsible for many of the most enduring American institutions and practices.

I admit this book is long, but it is so good. It is packed with illustrative examples, analysis and stories. Read it.

16 & 17. The Art of War by Sun-Tzu and On War by Carl Von Clausewitz

I know this will offend many strategy purists, but for most audiences I recommend these two books only with a pretty strong disclaimer.

While both are clearly full of strategic wisdom, they are hard to separate from their respective eras and brands of warfare. As budding strategists in business and in life, most of us are really looking for advice that can help us with our own problems. The reality is that Napoleonic warfare does not exactly have its equivalents in today’s society.

On the other hand, Sun-Tzu is so aphoristic that it’s hard to say what is concrete advice and what is just common sense. But the books are so convincing that you might still end up leaving thinking that they can be easily applied. So, again, check these books out if you’re really interested, but I think some of the other books are much better places to start.

18. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Richard B. Thaler & Cass R. Sunstein

This might feel like a weird book to include, but I think it presents another side of strategy that is too often forgotten.

It’s not always about bold actors and strategic thrusts. Sometimes strategy is about subtle influence. Sometimes it is framing and small tweaks that change behavior.

We can have big aims, but get there with little moves. This book has excellent examples of that kind of thinking and how it is changing politics, government and business. My favorite example is about the bumblebee that they started putting on urinals–which drastically reduced the amount of spray and spillage because it changed where men aimed when they peed. It’s not exactly the coolest strategy but it solved a problem. So we can learn from it.

19. Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Past 25 Years by Paul B. Carroll & Chunka Mui

I am putting this book on here as a cautionary tale for all the supposed business strategists out there. Because it turns out that most (if not all) genius business strategies are totally misguided and lead to catastrophic failure.

Your planned merger, roll up, pivot–it’s probably got glaring strategic flaws in it. Why? Because you’re too caught up in your own vision to see what can go wrong, to see where you’ve been overly optimistic, to accept how little you control.

Pairing this book with some of the books on war is a good idea. It will humble you and keep you conservative–which all good strategists are. “Boldness” should be used sparingly because it’s often actually just stupidity in disguise.

20, 21 & 22. The Big Con: The Story of Confidence Men, Whiz Mob: A Correlation of the Technical Argot of Pickpockets with Their Behavior Pattern by David W. Maurer and The Game: Penetrating the Secret Society of Pickup Artists by Neil Strauss

It probably seems weird to recommend books on pickup artists, pick pockets and con men (nor am I necessarily equating the three groups) but it fits.

Though I would accept that most of what these guys do is tactical rather than strategic—they are still quite excellent at identifying opportunities and weaving such flawless, enveloping plans that the marks often have no idea that anything is actually occurring.

A favorite con example is the one where the con man sets up a fake boxing match that he agrees to “fix” with his mark. Taking the marks money, he then fakes the fake boxing match so that it appears that one boxers kills the other in the ring. He and the mark then flee the scene in opposite direction to avoid the police–the mark thinking he got away with murder, when really he was robbed.

The Game is about seduction, literally, but the other two books are about seduction in their own way as well. These books are all classics and will help you, no matter what you do.

23 & 24. The Memoirs of Ulysses S Grant and Williams T. Sherman(Library of America)

These two men won the Civil War despite numerous obstacles.

In many ways, the war was the South’s to lose–they possessed all the territory they wanted at the beginning of the war, they faced a divided enemy, and all they had to do was wait the North out.

The America we live in today is what it is because of the strategic genius and partnership of the Grant and Sherman. Sherman understood the grand strategy of the war–that it depended on crushing the morale of the Southern cause. Grant understand and held the determination required to muddle through battle after battle (along with the destructive politics).

Sherman’s march through the South was a masterwork of planning and vision. Grant’s slow maneuvering of Lee, meant that Lee (who I think is massively overrated) could do nothing to stop it. These two books, written by the men themselves, are about totally unique and priceless historical documents.

***

Strategy is a rabbit hole that never ends. I am not saying that my list is conclusion–I know it doesn’t even come close. I am just trying to get you started.

I hope these books help. I hope they begin to bring out the strategist inside you. Because there is one there–and whatever you’re working on it will benefit from cultivating that side of yourself.

Now get reading and then get working. Because every word you read in these books become more valuable the more experience you combine it with. Don’t just read about strategy, live it.

This post appeared originally on Thought Catalog.

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:100%;}

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Get New Posts From Ryan Holiday Sent Right To Your Inbox

The post 24 Books To Hone Your Strategic Mind appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

November 9, 2016

An ancient guide to solving all work problems once and for all

The image of the Zen philosopher is the monk up in the green, quiet hills, or in a beautiful temple on some rocky cliff. The Stoic, on the other hand, is the antithesis of this idea. The Stoic is the man in the marketplace, the merchant on a voyage, the senator in the Forum, the soldier at the front. In other words, they are like you.

Those jobs might not seem like ones well-suited for “philosophy,” but they are. And so are you. For in even the most modern seeming professions, a Stoic is able to achieve peace and clarity. For thousands of years, Stoicism has been a tool for the ordinary and the elite alive—from slaves to emperors—as they sought wisdom, strength and the ‘good life.’ It was a philosophy designed for action—for doers—not for the classroom.

Which is why it has been popular with everyone from Marcus Aurelius and Seneca (one of the richest men in Rome), to Theodore Roosevelt, Frederick the Great and Michel de Montaigne. More recently, Stoicism has been cited by investors like Tim Ferriss and executives like Jonathan Newhouse, the CEO of Condé Nast International. Even football coaches like Pete Carroll of the Seattle Seahawks and baseball managers like Jeff Banister of the Texas Rangers have recommended Stoicism to their players.

How can we follow in their timeless footsteps? How can we reap the benefits of this operating system in our own workplace? It’s simple. Go straight to the sources. Below are 7 Stoic exercises and strategies, pulled from the new book The Daily Stoic (and daily email at DailyStoic.com), that will help you navigate your workplace with better clarity, effectiveness, and peace of mind.

DON’T MAKE THINGS HARDER THAN THEY NEED TO BE

“If someone asks you how to write your name, would you bark out each letter? And if they get angry, would you then return the anger? Wouldn’t you rather gently spell out each letter for them? So then, remember in life that your duties are the sum of individual acts. Pay attention to each of these as you do your duty . . . just methodically complete your task.”—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 6.26

Here’s a common scenario. You’re working with a frustrating coworker or a difficult boss. They ask you to do something and, because you dislike the messenger, you immediately object. There’s this problem or that one, or their request is obnoxious and rude. So you tell them, “No, I’m not going to do it.” Then they retaliate by not doing something that you had previously asked of them. And so the conflict escalates.

Meanwhile, if you could step back and see it objectively, you’d probably see that not everything they’re asking for is unreasonable. In fact, some of it is pretty easy to do or is, at least, agreeable. And if you did it, it might make the rest of the tasks a bit more tolerable too. Pretty soon, you’ve done the entire thing.

Life (and our job) is difficult enough. Let’s not make it harder by getting emotional about insignificant matters or digging in for battles we don’t actually care about. Let’s not let emotion get in the way of kathêkon, the simple, appropriate actions on the path to virtue.

IMPOSSIBLE WITHOUT YOUR CONSENT

“Today I escaped from the crush of circumstances, or better put, I threw them out, for the crush wasn’t from outside me but in my own assumptions.”—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 9.13

On tough days we might say, “My work is overwhelming,” or “My boss is really frustrating.” If only we could understand that this is impossible. Someone can’t frustrate you, work can’t overwhelm you-these are external objects, and they have no access to your mind. Those emotions you feel, as real as they are, come from the inside, not the outside.

The Stoics use the word hypolêpsis, which means “taking up”—of perceptions, thoughts, and judgments by our mind. What we assume, what we willingly generate in our mind, that’s on us. We can’t blame other people for making us feel stressed or frustrated any more than we can blame them for our jealousy. The cause is within us. They’re just the target.

A PROPER FRAME OF MIND

“Frame your thoughts like this—you are an old person, you won’t let yourself be enslaved by this any longer, no longer pulled like a puppet by every impulse, and you’ll stop complaining about your present fortune or dreading the future.”—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 2.2

We resent the person who comes in and tries to boss us around. Don’t tell me how to dress, how to think, how to do my job, how to live. This is because we are independent, self-sufficient people.

Or at least that’s what we tell ourselves.

Yet if someone says something we disagree with, something inside us tells us we have to argue with them. If there’s a plate of cookies in front of us, we have to eat them. If someone does something we dislike, we have to get mad about it. When something bad happens, we have to be sad, depressed, or worried. But if something good happens a few minutes later, all of a sudden we’re happy, excited, and want more.

We would never let another person jerk us around the way we let our impulses do. It’s time we start seeing it that way—that we’re not puppets that can be made to dance this way or that way just because we feel like it. We should be the ones in control, not our emotions, because we are independent, self-sufficient people.

KEEP IT SIMPLE

“At every moment keep a sturdy mind on the task at hand, as a Roman and human being, doing it with strict and simple dignity, affection, freedom, and justice—giving yourself a break from all other considerations. You can do this if you approach each task as if it is your last, giving up every distraction, emotional subversion of reason, and all drama, vanity, and complaint over your fair share. You can see how mastery over a few things makes it possible to live an abundant and devout life—for, if you keep watch over these things, the gods won’t ask for more.” — Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 2.5

Each day presents the chance to overthink things. What should I wear? Do they like me? Am I eating well enough? What’s next for me in life? Is my boss happy with my work?

Today, let’s focus just on what’s in front of us. We’ll follow the dictum that New England Patriots coach Bill Belichick gives his players: “Do your job.” Like a Roman, like a good soldier, like a master of our craft. We don’t need to get lost in a thousand other distractions or in other people’s business.

Marcus says to approach each task as if it were your last, because it very well could be. And even if it isn’t, botching what’s right in front of you doesn’t help anything. Find clarity in the simplicity of doing.

NEVER DO ANYTHING OUT OF HABIT

“So in the majority of other things, we address circumstances not in accordance with the right assumptions, but mostly by following wretched habit. Since all that I’ve said is the case, the person in training must seek to rise above, so as to stop seeking out pleasure and steering away from pain; to stop clinging to living and abhorring death; and in the case of property and money, to stop valuing receiving over giving.”—Musonius Rufus, Lectures, 6.25.5–11

A worker is asked: “Why did you do it this way?” The answer, “Because that’s the way we’ve always done things.” The answer frustrates every good boss and sets the mouth of every entrepreneur watering. The worker has stopped thinking and is mindlessly operating out of habit. The business is ripe for disruption by a competitor, and the worker will probably get fired by any thinking boss.

We should apply the same ruthlessness to our own habits. In fact, we are studying philosophy precisely to break ourselves of rote behavior. Find what you do out of rote memory or routine. Ask yourself: Is this really the best way to do it? Know why you do what you do—do it for the right reasons.

YOUR CAREER IS NOT A LIFE SENTENCE

“How disgraceful is the lawyer whose dying breath passes while at court, at an advanced age, pleading for unknown litigants and still seeking the approval of ignorant spectators.”—Seneca, On the Brevity of Life, 20.2

Every few years, a sad spectacle is played out in the news. An old millionaire, still lord of his business empire, is taken to court. Shareholders and family members go to court to argue that he is no longer mentally competent to make decisions—that the patriarch is not fit to run his own company and legal affairs. Because this powerful person refused to ever relinquish control or develop a succession plan, he is subjected to one of life’s worst humiliations: the public exposure of his most private vulnerabilities.

We must not get so wrapped up in our work that we think we’re immune from the reality of aging and life. Who wants to be the person who can never let go? Is there so little meaning in your life that your only pursuit is work until you’re eventually carted off in a coffin?

Take pride in your work. But it is not all.

PROTECT YOUR PEACE OF MIND

“Keep constant guard over your perceptions, for it is no small thing you are protecting, but your respect, trustworthiness and steadi- ness, peace of mind, freedom from pain and fear, in a word your freedom. For what would you sell these things?”—Epictetus, Discourses, 4.3.6b–8

The dysfunctional job that stresses you out, a contentious relationship, life in the spotlight. Stoicism, because it helps us manage and think through our emotional reactions, can make these kinds of situations easier to bear. It can help you manage and mitigate the triggers that seem to be so constantly tripped.

But here’s a question: Why are you subjecting yourself to this? Is this really the environment you were made for? To be provoked by nasty emails and an endless parade of workplace problems? Our adrenal glands can handle only so much before they become exhausted. Shouldn’t you preserve them for life-and-death situations?

So yes, use Stoicism to manage these difficulties. But don’t forget to ask: Is this really the life I want? Every time you get upset, a little bit of life leaves the body. Are these really the things on which you want to spend that priceless resource? Don’t be afraid to make a change—a big one.

For a bit of Stoic wisdom every single day right in your inbox, sign up for the Daily Stoic email. Over the first 7 days you will also receive a number of bonuses including an introduction to Stoicism, the best books and resources to read, Stoic exercises and much more!

#mc_embed_signup{background:#fff; clear:left; font:14px Helvetica,Arial,sans-serif; width:100%;}

/* Add your own MailChimp form style overrides in your site stylesheet or in this style block.

We recommend moving this block and the preceding CSS link to the HEAD of your HTML file. */

Get New Posts From Ryan Holiday Sent Right To Your Inbox

The post An ancient guide to solving all work problems once and for all appeared first on RyanHoliday.net.

October 24, 2016

100 Things I Learned in 10 Years and 100 Reads of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations

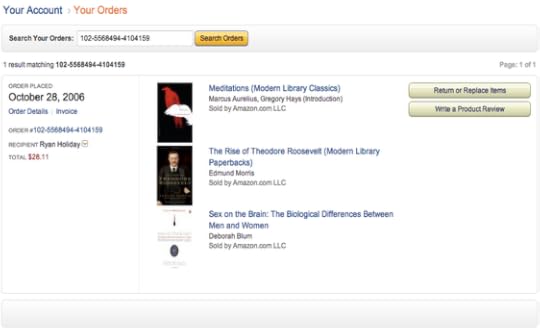

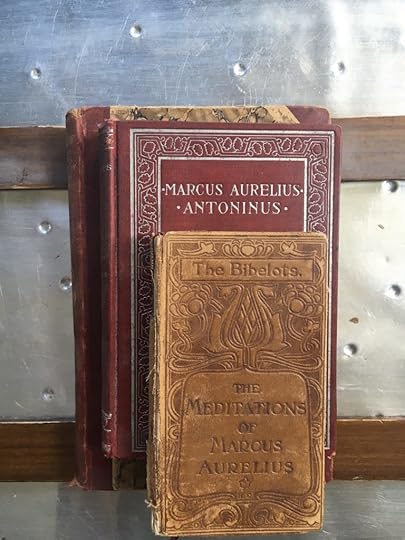

Almost exactly ten years ago, I bought the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius on Amazon. Amazon Prime didn’t exist then and to qualify for free shipping, I had to purchase a few other books at the same time. Two or three days later they all arrived.

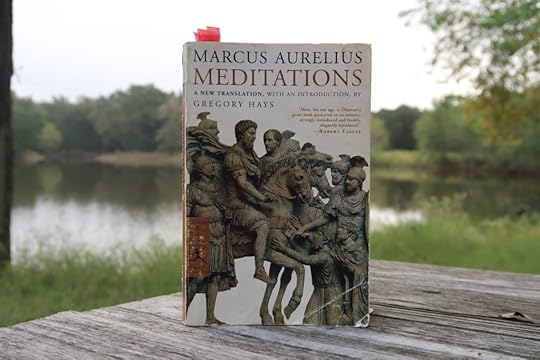

It’s a medium sized paperback, mostly white with a golden spine. On the cover Marcus is shown in relief, pardoning the barbarians. “Here, for our age, is Marcus’s great work,” says Robert Fagles in his blurb. I was 19 years old. I didn’t know who Marcus Aurelius was (besides the old guy in Gladiator) and I certainly didn’t know who Robert Fagles or Gregory Hays, the translator, was. But something drew me to this book almost immediately. I suppose it was luck that brought me to the specific translation I’d chosen (Modern Library Edition)—though the Stoics would call it fated—but what arrived would change my life.

It would be for me, what Tyler Cowen would call a “a quake book,” shaking everything I thought I knew about the world (however little that actually was). I would also become what Stephen Marche has referred to as a “centireader,” reading Marcus Aurelius well over 100 times across multiple editions and copies.

In the course of those readings and my study of stoicism, a lot has changed. Marcus Aurelius has guided me through breakups and getting married, through being relatively young and poor and relatively older and well-off. His wisdom has helped me with getting fired and with quitting, with success and with struggles. I’ve carried him to close to a dozen countries and moved him to multiple houses. I’ve turned to him for articles and books and casual dinner conversation. The one pristine white cover is now its own shade of tan, but with every read, every time I’ve touched the book, I’ve gotten something new or been reminded of something timeless and important.

Now with the release of my own translation and compendium, The Daily Stoic (and a daily email newsletter at DailyStoic.com), I wanted to take the time to reflect on what I’ve learned in ten years with one of the greatest and most unique pieces of literature ever created.

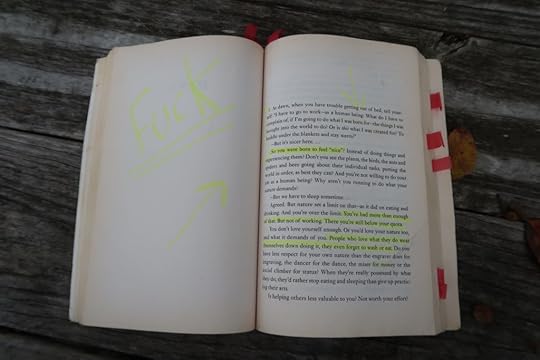

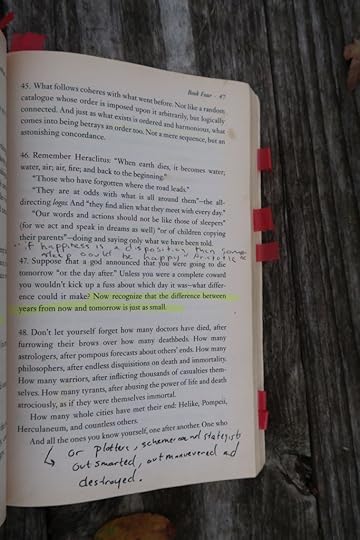

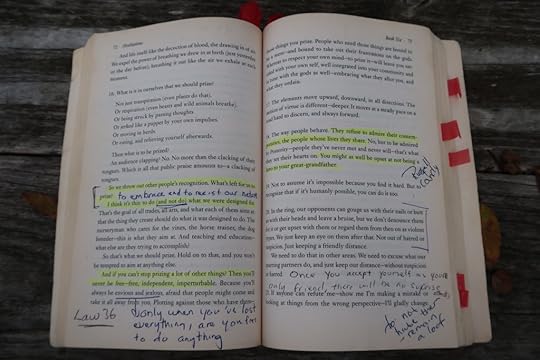

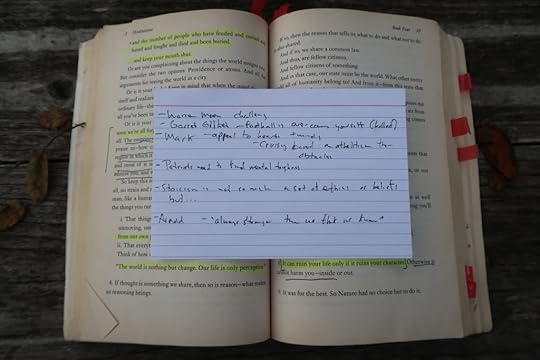

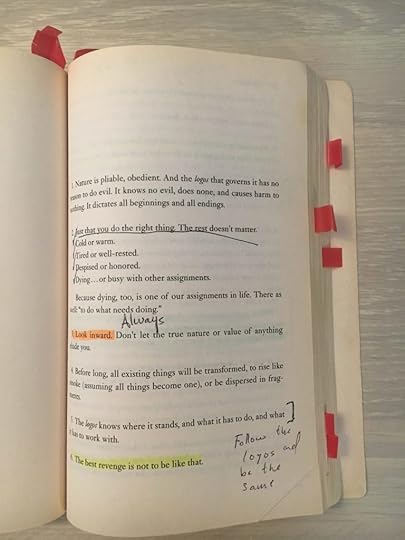

-It was the opening passage of Book 5—about our reluctance to get out of bed and get moving in the morning—that struck me most on my first read. As you can see, I wrote “FUCK” with a highlighter and you can see how important that passage was to me at the time in a 2007 blog post. Later, I would print out this passage and put it next to my desk and bed. I think it was that as a college student I needed that extra motivation. I was a little lazy and entitled. I needed to seize life and take advantage of it—and Marcus served me well in that regard for a long time.

-Though I will say that today, I think less about the passage that motivates me to do more and be more active. If I was to put a different one on my desk, I’d choose from Book Ten, “If you seek tranquility, do less.”

-In my first read of Meditations, I highlighted the line “It can ruin your life only if it ruins your character.” In a later read I added brackets around that line, just for more emphasis. And I underlined in pen what came after, “Otherwise, it cannot harm you—inside or out.”

-Pages XXVI and XXV of Hays’s introduction is where I was first introduced to the distillation of Stoicism into three distinct disciplines (perception, action, will). It was this order that eventually shaped both The Obstacle is the Way and The Daily Stoic. When I get asked to explain the three disciplines, this is usually my short answer: See things for what they are. Do what we can. Endure and bear what we must.