Alexandra Sokoloff's Blog, page 28

November 14, 2012

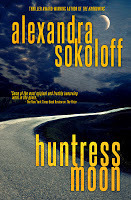

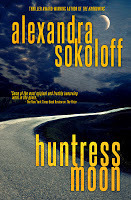

The Next Big Thing: Huntress Moon

My sister horror/thriller author Sarah Pinborough tagged me as part of the Next Big Thing blog hop, one of those community building/promotional things that authors do to get exposure and give exposure to the authors we're reading and loving.

Sarah is a UK diva, I mean writer, that I met in Toronto at the World Horror Convention. Female authors are few and far between in our genre (despite the fact that some of the brightest stars in the genre firmament are women: Mary Shelley, Shirley Jackson, Daphne duMaurier, Charlotte Perkins Gilman...), and Sarah and I bonded right away. If you want a good scare, look no further, and she's recently expanded into the darker recesses of non-supernatural evil with her crime thrillers and TV writing. She's also wicked fun, and for the proverbial good time, I highly encourage you all to follow her on Facebook.

Here's the interview on Sarah's latest book: http://sarahpinborough.com

And her follow info: http://www.facebook.com/sarah.pinborough

---------------------------------------------

So I'm up next in this blog hop, and I get to answer the exact same questions.

1) What is the title of your newest or next book?

Huntress Moon. The next is book two in the series, Blood Moon.

And I just found out this morning that Huntress Moon is one of Suspense Magazine's picks for Best Books of 2012!

2) Where did the idea come from for the book?

The idea came to me at the San Francisco Bouchercon, always the most inspiring of the mystery conferences for me. One afternoon there were two back-to-back discussions with several of my favorite authors: Val McDermid interviewing Denise Mina, then Robert Crais interviewing Lee Child. (Can you even imagine...?)

There was a lot of priceless stuff in those two hours, but two things that really struck me from the McDermid/Mina chat were Val saying that crime fiction is the best way to explore societal issues, and Denise saying that she finds powerful inspiration in writing about what makes her angry.

Write about what makes you angry? It doesn’t take me a millisecond’s thought to make my list. Child sexual abuse is the top, no contest. Violence against women and children. Human trafficking. Discrimination of any kind. Religious intolerance. War crimes. Genocide. Torture.

That anger has fueled a lot of my books and scripts over the years.

And then right after that, there was Lee Child talking about Reacher, one of my favorite fictional characters, and it got me thinking about what it would look like if a woman were doing what Reacher was doing. And that was it - instantly I had the whole story of Huntress Moon.

Because of course I’ve been brooding about all of this for decades, now. I've always thought that as writers we're only working with a handful of themes, which we explore over and over, in different variations. And I think it's really useful to be very conscious of those themes. Not only do they fuel our writing, they also brand us as writers.

With the Huntress series I finally have an umbrella to explore, dramatically, over multiple books, the roots and context of the worst crimes I know. And at least on paper, do something about it.

3) What genre does your book fall under?

It’s never just one for me! Psychological thriller, police procedural, hard-boiled mystery.

4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

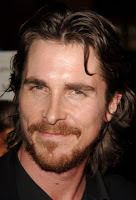

I always see Kyle Chandler as Special Agent Roarke, but practically that wouldn’t happen. Maybe for a TV series. If Russell Crowe were even remotely interested I'd die happy. And Christian Bale would work just fine!

Such a dearth of American leading men, and even fewer who can get a movie made! Ryan Gosling is too young but would be just about old enough by the time the movie actually went into production, and I think he's brilliant.

Then there's Viggo Mortenson, if I made both lead characters older. And who wouldn't do whatever it takes for Viggo!

And I’m a longtime fan of Norman Reedus, which also would probably be more likely for TV. (He looks younger than he actually is!)

If it’s a movie, Keira Knightly or Mila Kunis would be superb for the Huntress.

I would gladly rewrite the character as a little older for Milla Jovovich or Charlize Theron.

On the TV front, I've been impressed with Lauren Cohan and Summer Glau.

And I am so hoping that Lindsay Lohan gets herself together and goes on to be the brilliant star she clearly could be. People forget or just don't know how many of our most beloved actors fell just as far as she has before they got a second chance from people in the industry who understand very well about demons and the perils of a too-early stardom. I think she'd be great.

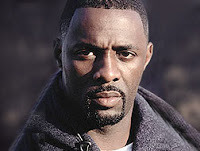

And Special Agent Epps – no contest. I wrote him with Idris Elba in mind. Constantly. Did I mention how much I love my job

5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

A driven FBI agent is on the hunt for that most rare of killers... a female serial.

6) Is your book self-published or traditionally published?

Self-published.

7) How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

It felt like forever! I started it two years ago, and maybe I actually got to a first draft back then, but then I had a whole lot of life - and death - intervene. I picked it back up at the beginning of this year and powered down and finished it.

8) What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

People who review it compare it to The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Dexter - and the TV shows Criminal Minds and CSI and Luther, but I've always thought of the Huntress as a female Reacher. Only crazier. And the structure is definitely like The Fugitive. But with a woman. Which means a hell of a lot more erotic tension.

9) Who or what inspired you to write this book?

See # 2 above!

10) What else about the book might pique the reader's interest?

I wrote it about a female serial killer – when arguably, using the FBI Behavioral Analysis Unit's definition of sexual homicide, there’s never been any such thing. I wanted to explore that very point as a social and psychological issue, and that’s one of the tensions of the book. Is she a serial killer or not? What is she doing, really?

Also, it’s very clear that the vast majority of readers end up strongly sympathizing with, and empathizing with, or even falling in love with the killer, and most of them are surprised by that.

Also, if you've ever fallen for someone who is just wrong in every way and still irresistible... well, you might relate.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

So for next week, I'm tagging five great authors who write fantastic female leads. I'm not going to say "kick ass" female leads because that's not what I'm looking for in a female protagonist, even if said female protagonist can indeed kick ass. Personally I want to see a woman who is strong and complicated in the ways that a real woman is strong and complicated, and that is rarely about being able to beat the living shit out of people. So here are some of my top choices in the category.

- Michelle Gagnon is a thriller writer who has recently brought her powerhouse female perspective and adrenaline-charged storytelling to the YA thriller genre with her latest, Don't Turn Around. Noa is a terrific teenage role model. http://michellegagnon.com

- Christa Faust knows noir backward and forward, and has virtually created a whole new direction for the genre and its characters. Angel Dare is an alt heroine who brings OUT everything that noir anti-heroines like Gloria Grahame were doing in a coded sense, and Butch Fatale takes the "two-fisted detective" archetype to a new meaning. http://christafaust.net/

- As anyone who reads this blog knows, I am VERY picky about men writing "strong women", and on the dark side, Wallace Stroby is as good as it gets, both shattering and reversing noir gender stereotypes. His Crissa Stone series presents a thief who doesn't just hold her own, but leads and controls motley collections of doomed male gangsters. And I'm even more fond of Stroby's Sara Cross, who mirrors the classic noir paradigm: she's a truly good woman whose near-fatal flaw is a tragically bad man. http://wallacestroby.com/

- Zoe Sharp actually DOES write a kick-ass female lead, Charlie Fox, who works as a bodyguard and makes the physical reality of her job perfectly plausible (I've learned a lot about self-defense from these two...) while she battles uniquely feminine psychological demons. And her new installment in the Charlie series is set in New Orleans! http://zoesharp.com/

- Rhodi Hawk combines psychological thriller, Southern Gothic, and a hint of the supernatural in her lushly written series, also set in New Orleans. Her latest, A Tangled Bridge, is just out. http://rhodihawk.com/literary.htm

Tune in next week as I blog about these wonderful authors, and I'll be linking to their interviews.

And this week you can find other The Next Big Thing Q&As here (as described by Sarah Pinborough).

Bill Hussey is an awesome YA author whose grisly Witchfinder series is well worth reading! Kids everywhere love it – adults too. Strange that someone so chirpy can write the death of children so well. That’s probably why I like him.

http://www.williamhussey.co.uk

Suzanne McLeod is an urban fantasy writer (if we must use genres!) whose Spellcracker series from Gollancz have done tremendously well. A saucy minx. We drink together.

http://www.spellcrackers.com

Jonathan Green is a prolific fiction and non-fiction writer who has covered a range of styles and genres in his time. He’s a steampunk king and a disco diva. I heart him.

http://jonathangreenauthor.blogspot.co.uk

------------------------------------------------------------------------

(PS: To everyone who entered my Halloween giveaway drawing, I haven't forgotten you. My Jersey-based mistress of marketing was one of the many, many people who suffered severe flooding during the storm, and I don't want to press her on the contest right now; we'll draw winners and get the books out as soon as things have settled a little more back East. Thanks for understanding!)

Sarah is a UK diva, I mean writer, that I met in Toronto at the World Horror Convention. Female authors are few and far between in our genre (despite the fact that some of the brightest stars in the genre firmament are women: Mary Shelley, Shirley Jackson, Daphne duMaurier, Charlotte Perkins Gilman...), and Sarah and I bonded right away. If you want a good scare, look no further, and she's recently expanded into the darker recesses of non-supernatural evil with her crime thrillers and TV writing. She's also wicked fun, and for the proverbial good time, I highly encourage you all to follow her on Facebook.

Here's the interview on Sarah's latest book: http://sarahpinborough.com

And her follow info: http://www.facebook.com/sarah.pinborough

---------------------------------------------

So I'm up next in this blog hop, and I get to answer the exact same questions.

1) What is the title of your newest or next book?

Huntress Moon. The next is book two in the series, Blood Moon.

And I just found out this morning that Huntress Moon is one of Suspense Magazine's picks for Best Books of 2012!

2) Where did the idea come from for the book?

The idea came to me at the San Francisco Bouchercon, always the most inspiring of the mystery conferences for me. One afternoon there were two back-to-back discussions with several of my favorite authors: Val McDermid interviewing Denise Mina, then Robert Crais interviewing Lee Child. (Can you even imagine...?)

There was a lot of priceless stuff in those two hours, but two things that really struck me from the McDermid/Mina chat were Val saying that crime fiction is the best way to explore societal issues, and Denise saying that she finds powerful inspiration in writing about what makes her angry.

Write about what makes you angry? It doesn’t take me a millisecond’s thought to make my list. Child sexual abuse is the top, no contest. Violence against women and children. Human trafficking. Discrimination of any kind. Religious intolerance. War crimes. Genocide. Torture.

That anger has fueled a lot of my books and scripts over the years.

And then right after that, there was Lee Child talking about Reacher, one of my favorite fictional characters, and it got me thinking about what it would look like if a woman were doing what Reacher was doing. And that was it - instantly I had the whole story of Huntress Moon.

Because of course I’ve been brooding about all of this for decades, now. I've always thought that as writers we're only working with a handful of themes, which we explore over and over, in different variations. And I think it's really useful to be very conscious of those themes. Not only do they fuel our writing, they also brand us as writers.

With the Huntress series I finally have an umbrella to explore, dramatically, over multiple books, the roots and context of the worst crimes I know. And at least on paper, do something about it.

3) What genre does your book fall under?

It’s never just one for me! Psychological thriller, police procedural, hard-boiled mystery.

4) What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

I always see Kyle Chandler as Special Agent Roarke, but practically that wouldn’t happen. Maybe for a TV series. If Russell Crowe were even remotely interested I'd die happy. And Christian Bale would work just fine!

Such a dearth of American leading men, and even fewer who can get a movie made! Ryan Gosling is too young but would be just about old enough by the time the movie actually went into production, and I think he's brilliant.

Then there's Viggo Mortenson, if I made both lead characters older. And who wouldn't do whatever it takes for Viggo!

And I’m a longtime fan of Norman Reedus, which also would probably be more likely for TV. (He looks younger than he actually is!)

If it’s a movie, Keira Knightly or Mila Kunis would be superb for the Huntress.

I would gladly rewrite the character as a little older for Milla Jovovich or Charlize Theron.

On the TV front, I've been impressed with Lauren Cohan and Summer Glau.

And I am so hoping that Lindsay Lohan gets herself together and goes on to be the brilliant star she clearly could be. People forget or just don't know how many of our most beloved actors fell just as far as she has before they got a second chance from people in the industry who understand very well about demons and the perils of a too-early stardom. I think she'd be great.

And Special Agent Epps – no contest. I wrote him with Idris Elba in mind. Constantly. Did I mention how much I love my job

5) What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

A driven FBI agent is on the hunt for that most rare of killers... a female serial.

6) Is your book self-published or traditionally published?

Self-published.

7) How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

It felt like forever! I started it two years ago, and maybe I actually got to a first draft back then, but then I had a whole lot of life - and death - intervene. I picked it back up at the beginning of this year and powered down and finished it.

8) What other books would you compare this story to within your genre?

People who review it compare it to The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Dexter - and the TV shows Criminal Minds and CSI and Luther, but I've always thought of the Huntress as a female Reacher. Only crazier. And the structure is definitely like The Fugitive. But with a woman. Which means a hell of a lot more erotic tension.

9) Who or what inspired you to write this book?

See # 2 above!

10) What else about the book might pique the reader's interest?

I wrote it about a female serial killer – when arguably, using the FBI Behavioral Analysis Unit's definition of sexual homicide, there’s never been any such thing. I wanted to explore that very point as a social and psychological issue, and that’s one of the tensions of the book. Is she a serial killer or not? What is she doing, really?

Also, it’s very clear that the vast majority of readers end up strongly sympathizing with, and empathizing with, or even falling in love with the killer, and most of them are surprised by that.

Also, if you've ever fallen for someone who is just wrong in every way and still irresistible... well, you might relate.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

So for next week, I'm tagging five great authors who write fantastic female leads. I'm not going to say "kick ass" female leads because that's not what I'm looking for in a female protagonist, even if said female protagonist can indeed kick ass. Personally I want to see a woman who is strong and complicated in the ways that a real woman is strong and complicated, and that is rarely about being able to beat the living shit out of people. So here are some of my top choices in the category.

- Michelle Gagnon is a thriller writer who has recently brought her powerhouse female perspective and adrenaline-charged storytelling to the YA thriller genre with her latest, Don't Turn Around. Noa is a terrific teenage role model. http://michellegagnon.com

- Christa Faust knows noir backward and forward, and has virtually created a whole new direction for the genre and its characters. Angel Dare is an alt heroine who brings OUT everything that noir anti-heroines like Gloria Grahame were doing in a coded sense, and Butch Fatale takes the "two-fisted detective" archetype to a new meaning. http://christafaust.net/

- As anyone who reads this blog knows, I am VERY picky about men writing "strong women", and on the dark side, Wallace Stroby is as good as it gets, both shattering and reversing noir gender stereotypes. His Crissa Stone series presents a thief who doesn't just hold her own, but leads and controls motley collections of doomed male gangsters. And I'm even more fond of Stroby's Sara Cross, who mirrors the classic noir paradigm: she's a truly good woman whose near-fatal flaw is a tragically bad man. http://wallacestroby.com/

- Zoe Sharp actually DOES write a kick-ass female lead, Charlie Fox, who works as a bodyguard and makes the physical reality of her job perfectly plausible (I've learned a lot about self-defense from these two...) while she battles uniquely feminine psychological demons. And her new installment in the Charlie series is set in New Orleans! http://zoesharp.com/

- Rhodi Hawk combines psychological thriller, Southern Gothic, and a hint of the supernatural in her lushly written series, also set in New Orleans. Her latest, A Tangled Bridge, is just out. http://rhodihawk.com/literary.htm

Tune in next week as I blog about these wonderful authors, and I'll be linking to their interviews.

And this week you can find other The Next Big Thing Q&As here (as described by Sarah Pinborough).

Bill Hussey is an awesome YA author whose grisly Witchfinder series is well worth reading! Kids everywhere love it – adults too. Strange that someone so chirpy can write the death of children so well. That’s probably why I like him.

http://www.williamhussey.co.uk

Suzanne McLeod is an urban fantasy writer (if we must use genres!) whose Spellcracker series from Gollancz have done tremendously well. A saucy minx. We drink together.

http://www.spellcrackers.com

Jonathan Green is a prolific fiction and non-fiction writer who has covered a range of styles and genres in his time. He’s a steampunk king and a disco diva. I heart him.

http://jonathangreenauthor.blogspot.co.uk

------------------------------------------------------------------------

(PS: To everyone who entered my Halloween giveaway drawing, I haven't forgotten you. My Jersey-based mistress of marketing was one of the many, many people who suffered severe flooding during the storm, and I don't want to press her on the contest right now; we'll draw winners and get the books out as soon as things have settled a little more back East. Thanks for understanding!)

Published on November 14, 2012 04:45

•

Tags:

alexandra-sokoloff, huntress-moon, suspense-magazine, the-next-big-thing

November 12, 2012

NaNoWriMo Prompt: THE PLAN

Okay, yes, I disappeared! Research trip to San Francisco so that I can finally start writing again, on my third draft now of Blood Moon. I can't believe how much running around I packed into five days. Totally worth it. I'm also so sore I can barely walk. I always forget how PHYSICAL life is up there in the Bay Area. Better than a stair master.

So now it's nearly a third of the way into the month, and if you've been doing Nano diligently you may be closing in on 20,000 words. Amazing, but some people really do get that far.

Depending on how thorough you're being with all this writing, then, you've probably written the first act and are moving into the second. Or if you're taking this "write a book in a month" thing literally, then you're closer to the midpoint. Of a very short book.

Either way, you are currently faced with the dreaded second act. Although anyone who has the workbooks and/or reads this blog regularly shouldn't fear the second act any more, right?

But today I wanted to review what I think it the key to any second act, and really the whole key to story structure: The PLAN.

You

always hear that “Drama is conflict,” but when you think about it –what the

hell does that mean, practically?

It’s

actually much more true, and specific, to say that drama is the constant

clashing of a hero/ine’s PLAN and an antagonist’s, or several antagonists’,

PLANS.

In

the first act of a story, the hero/ine is introduced, and that hero/ine either

has or quickly develops a DESIRE. She might have a PROBLEM that needs to be

solved, or someone or something she WANTS, or a bad situation that she needs to

get out of, pronto.

Her

reaction to that problem or situation is to formulate a PLAN, even if that plan

is vague or even completely subconscious. But somewhere in there, there is a

plan, and storytelling is usually easier if you have the hero/ine or someone

else (maybe you, the author) state that plan clearly, so the audience or reader

knows exactly what the expectation is.

And

the protagonist’s plan (and the corresponding plan of the antagonist’s)

actually drives the entire action of the second act. Stating the plan tells us

what the CENTRAL ACTION of the story will be. So it’s critical to set up the

plan by the end of Act One, or at the very beginning of Act Two, at the latest.

Let’s

look at some examples of how plans work.

I’m

going to start, improbably, with the actioner 2012, even though I thought it was a pretty

terrible movie overall.

Now,

I’m sure in a theater this movie delivered on its primary objective, which was

a rollercoaster ride as only Hollywood special effects can provide. Whether we

like it or not, there is obviously a massive worldwide audience for movies that

are primarily about delivering pure sensation. Story isn’t important, nor,

apparently, is basic logic. As long as people keep buying enough tickets to

these movies to make them profitable, it’s the business of Hollywood to keep

churning them out.

But

in 2012, even in that rollercoaster ride

of special effects and sensations, there was a clear central PLAN for an

audience to hook into, a plan that drove the story. Without that plan, 2012 really would have been nothing but a chaos of

special effects.

If

you’ve seen this movie (and I know some of you have … ), there is a point in

the first act where a truly over-the-top Woody Harrelson as an Art Bell-like

conspiracy pirate radio commentator rants to protagonist John Cusack about

having a map that shows the location of “spaceships” that the government is

stocking to abandon planet when the prophesied end of the world commences.

Although

Cusack doesn’t believe it at the time, this is the PLANT (sort of camouflaged

by the fact that Woody is a nutjob), that gives the audience the idea of what

the PLAN OF ACTION will be: Cusack will have to go back for the map in the

midst of all the cataclysm, then somehow get his family to these “spaceships”

in order for all of them to survive the end of the world.

The

PLAN is reiterated, in dialogue, when Cusack gets back to his family and tells

his ex-wife basically exactly what I just said above: “We’re going to go back

to the nutjob with the map so that we can get to those spaceships and get off

the planet before it collapses.”

And

lo and behold, that’s exactly what happens; it’s not only Cusack’s PLAN, but

the central action of the story, that can be summed up as a CENTRAL QUESTION: Will

Cusack be able to get his family to the spaceships before the world ends?

Or

put another way, the CENTRAL STORY ACTION is John Cusack getting his family to

the spaceships before the world ends.

(Note

the ticking clock, there, as well. And as if the end of the world weren’t

enough, the movie also starts a literal “Twenty-nine minutes to the end of the

world!” ticking computer clock at, yes, 29 minutes before the end of the movie.

I must point out here that ticking clocks are dangerous because of the huge

cliché factor. We all need to study structure to know what not to do, as well.)

And

all this happens about the end of Act I.

Remember that I said that it’s essential to have laid out the CENTRAL

QUESTION and CENTRAL STORY ACTION by the end of Act I? But also at this point –

or possibly just after the climax of Act I, in the very beginning of Act II – we

need to know what the PLAN is. PLAN and CENTRAL QUESTION are integrally

related, and I keep looking for ways to talk about it because this is such an

important concept to master.

A

reader/audience really needs to know what the overall PLAN is, even if they

only get it in a subconscious way. Otherwise they are left floundering,

wondering where the hell all of this is going.

In

2012, even in the midst of all the

buildings crumbling and crevasses opening and fires booming and planes

crashing, we understand on some level what is going on:

-

What does the protagonist want? (OUTER DESIRE) To save his

family.

-

How is he going to do it? (PLAN) By

getting the map from the nutjob and getting his family to the secret spaceships

(that aren’t really spaceships).

-

What’s standing in his way? (FORCES OF

OPPOSITION) About a million natural disasters as the planet caves in, an evil

politician who has put a billion dollar price tag on tickets for the spaceship,

a Russian Mafioso who keeps being in the same place at the same time as Cusack,

and sometimes ends up helping, and sometimes ends up hurting. (Was I the only

one queased out by the way all the Russian characters were killed off, leaving

only the most obnoxious kids on the planet?)

Here’s

another example, from a much better movie:

At

the end of the first sequence of Raiders of the Lost Ark (which

is arguably two sequences in itself, first the action sequence in the cave in

South America, then the university sequence back in the US), Indy has just finished

teaching his archeology class when his mentor, Marcus, comes to meet him with a

couple of government agents who have a job for him (CALL TO ADVENTURE). The

agents explain that Hitler has become obsessed with collecting occult artifacts

from all over the world, and is currently trying to find the legendary Lost Ark

of the Covenant, which is rumored to make any army in possession of it

invincible in battle.

So

there’s the MACGUFFIN, the object that everyone wants, and the STAKES: if

Hitler’s minions (THE ANTAGONISTS) get this Ark before Indy does, the Nazi army

will be invincible.

And

then Indy explains his PLAN to find the Ark: his old mentor, Abner Ravenwood,

was an expert on the Ark and had an ancient Egyptian medallion on which was

inscribed the instructions for using the medallion to find the hidden location

of the Ark.

So

after hearing the plan, we understand the entire OVERALL ACTION of the story:

Indy is going to find Abner (his mentor) to get the medallion, then use the

medallion to find the Ark before Hitler’s minions can get it.

And

even though there are lots of twists along the way, that’s really it: the basic

action of the story.

Generally,

PLAN and CENTRAL STORY ACTION are really the same thing – the Central Action of

the story is carrying out the specific Plan. And the CENTRAL QUESTION of the

story is – “Will the Plan succeed?”

Again,

the PLAN, CENTRAL QUESTION and CENTRAL STORY ACTION are almost always set up –

and spelled out – by the end of the first act, although the specifics of the

Plan may be spelled out right after the Act I Climax at the very beginning of

Act II.

Can

it be later? Well, anything’s possible, but the sooner a reader or audience

understands the overall thrust of the story action, the sooner they can relax

and let the story take them where it’s going to go. So much of storytelling is

about you, the author, reassuring your reader or audience that you know what

you’re doing, so they can sit back and let you drive.

If

you haven’t done this yet, take a favorite movie or book (or two or three) and

identify the PLAN, CENTRAL STORY ACTION and CENTRAL QUESTION and them in a few

sentences. Like this:

-

In Inception, the PLAN is for the

team of dream burglars to go into a corporate heir’s dreams to plant the idea

of breaking up his father’s corporation. (So the CENTRAL ACTION is going into

the corporate heir’s dream and planting the idea, and the CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will they succeed?)

-

In Sense and Sensibility, the

PLAN is for Marianne and Elinor to secure the family’s fortune and their own

happiness by marrying well. (How are they going to do that? By the period’s

equivalent of dating – which is the

CENTRAL ACTION. Yes, dating is a PLAN! The CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will the

sisters succeed in marrying well?)

-

In The Proposal, Margaret’s PLAN

is to learn enough about Andrew over the four-day weekend with his family to

pass the INS marriage test so she won’t be deported. (The CENTRAL ACTION is

going to Alaska to meet Andrew’s family and pretending to be married while they

learn enough about each other to pass the test. The CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will

they be able to successfully fake the marriage?

Now,

try it with your own story!

-

What does the protagonist WANT?

-

How does s/he PLAN to do it?

-

What and who is standing in his or her way?

For

example, in my latest thriller, Book of Shadows, here's the Act One set up: the protagonist, homicide detective Adam

Garrett, is called on to investigate the murder of a college girl, which looks

like a Satanic killing. Garrett and his partner make a quick arrest of a

classmate of the girl's, a troubled Goth musician. But Garrett is not convinced

of the boy's guilt, and when a practicing witch from nearby Salem insists the

boy is innocent and there have been other murders, he is compelled to

investigate further.

So

Garrett’s PLAN and the CENTRAL ACTION of the story is to use the witch and her

specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate the murder on his

own, all the while knowing that she is using him for her own purposes and may

well be involved in the killing.

The CENTRAL QUESTION is: will they catch the killer before s/he kills

again – and/or kills Garrett (if the witch turns out to be the killer)?

-

What does the protagonist WANT? To catch

the killer before s/he kills again.

-

How does he PLAN to do it? By using the

witch and her specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate

further.

-

What’s standing in his way? His own

department, the killer, and possibly the witch herself. And if the witch is

right … possibly even a demon.

It’s

important to note that the Plan and Central Action of the story are not always

driven by the protagonist. Usually, yes. But in The Matrix, it’s Neo’s mentor Morpheus who has the overall

PLAN, which drives the central action right up until the end of the second act.

The Plan is to recruit and train Neo, whom Morpheus believes is “The One”

prophesied to destroy the Matrix. So that’s the action we see unfolding:

Morpheus recruiting, deprogramming and training Neo, who is admittedly very

cute, but essentially just following Morpheus’s orders for two thirds of the

movie.

Does

this weaken the structure of that film? Not at all. Morpheus drives the action

until that crucial point, the Act Two Climax, when he is abducted by the agents

of the Matrix, at which point Neo steps into his greatness and becomes “The One” by taking over the action and making a new

plan: to rescue Morpheus by sacrificing himself.

It

is a terrific way to show a huge character arc: Neo stepping into his destiny.

And I would add that this is a common structural pattern for mythic journey

stories – in Lord of the Rings, it's Gandalf who has the PLAN and drives the

reluctant Frodo in the central story action until Frodo finally takes over the

action himself.

Here’s

another example. In the very funny romantic comedy It’s Complicated, Meryl Streep’s character Jane is the protagonist,

but she doesn’t drive the action or have any particular plan of her own. It’s

her ex-husband Jake (Alec Baldwin), who seduces her and at the end of the first

act, proposes (in an extremely persuasive speech) that they continue this

affair as a perfect solution to both their love troubles – it will fulfill their sexual and intimacy needs

without disrupting the rest of their lives.

Jane

decides at that point to go along with Jake’s plan (saying, “I forgot what a

good lawyer you are”). In terms of action, she is essentially passive, letting

the two men in her life court her (which results in bigger and bigger comic

entanglements), but that makes for a more pronounced and satisfying character

arc when she finally takes a stand and breaks off the affair with Jake for

good, so she can finally move on with her life.

I

would venture to guess that most of us know what it’s like to be swept up in a

ripping good love entanglement, and can sympathize with Jane’s desire just to

go with the passion of it without having to make any pesky practical decisions.

It’s a perfectly fine – and natural – structure for a romantic comedy, as long as at that

key juncture, the protagonist has the realization and balls – or ovaries –

to take control of her own life again and make a stand for what she truly wants.

I

give you these last two examples – hopefully

– to show how helpful it can be to study

the specific structure of stories that are similar to your own. As you can see

from the above, the general writing rule that the protagonist drives the action

may not apply to what you’re

writing – and you might want to make a

different choice that will better serve your own story. And that goes for any general writing rule.

QUESTIONS:

Have you identified the CENTRAL ACTION of your story? Do you know what the protagonist's and antagonist's PLANS are? At what point

in your book does the reader have a clear idea of the protagonist’s PLAN? Is it stated aloud? Can you make it clearer

than it is?

And yes, let's hear how everyone's doing!

- Alex

(PS: To everyone who entered my Halloween giveaway drawing, I haven't forgotten you. My mistress of marketing was one of the many, many people who suffered severe flooding during the storm, and I don't want to press her on the contest right now; we'll draw winners and get the books out as soon as things have settled a little more back East. Thanks for understanding!)

So now it's nearly a third of the way into the month, and if you've been doing Nano diligently you may be closing in on 20,000 words. Amazing, but some people really do get that far.

Depending on how thorough you're being with all this writing, then, you've probably written the first act and are moving into the second. Or if you're taking this "write a book in a month" thing literally, then you're closer to the midpoint. Of a very short book.

Either way, you are currently faced with the dreaded second act. Although anyone who has the workbooks and/or reads this blog regularly shouldn't fear the second act any more, right?

But today I wanted to review what I think it the key to any second act, and really the whole key to story structure: The PLAN.

You

always hear that “Drama is conflict,” but when you think about it –what the

hell does that mean, practically?

It’s

actually much more true, and specific, to say that drama is the constant

clashing of a hero/ine’s PLAN and an antagonist’s, or several antagonists’,

PLANS.

In

the first act of a story, the hero/ine is introduced, and that hero/ine either

has or quickly develops a DESIRE. She might have a PROBLEM that needs to be

solved, or someone or something she WANTS, or a bad situation that she needs to

get out of, pronto.

Her

reaction to that problem or situation is to formulate a PLAN, even if that plan

is vague or even completely subconscious. But somewhere in there, there is a

plan, and storytelling is usually easier if you have the hero/ine or someone

else (maybe you, the author) state that plan clearly, so the audience or reader

knows exactly what the expectation is.

And

the protagonist’s plan (and the corresponding plan of the antagonist’s)

actually drives the entire action of the second act. Stating the plan tells us

what the CENTRAL ACTION of the story will be. So it’s critical to set up the

plan by the end of Act One, or at the very beginning of Act Two, at the latest.

Let’s

look at some examples of how plans work.

I’m

going to start, improbably, with the actioner 2012, even though I thought it was a pretty

terrible movie overall.

Now,

I’m sure in a theater this movie delivered on its primary objective, which was

a rollercoaster ride as only Hollywood special effects can provide. Whether we

like it or not, there is obviously a massive worldwide audience for movies that

are primarily about delivering pure sensation. Story isn’t important, nor,

apparently, is basic logic. As long as people keep buying enough tickets to

these movies to make them profitable, it’s the business of Hollywood to keep

churning them out.

But

in 2012, even in that rollercoaster ride

of special effects and sensations, there was a clear central PLAN for an

audience to hook into, a plan that drove the story. Without that plan, 2012 really would have been nothing but a chaos of

special effects.

If

you’ve seen this movie (and I know some of you have … ), there is a point in

the first act where a truly over-the-top Woody Harrelson as an Art Bell-like

conspiracy pirate radio commentator rants to protagonist John Cusack about

having a map that shows the location of “spaceships” that the government is

stocking to abandon planet when the prophesied end of the world commences.

Although

Cusack doesn’t believe it at the time, this is the PLANT (sort of camouflaged

by the fact that Woody is a nutjob), that gives the audience the idea of what

the PLAN OF ACTION will be: Cusack will have to go back for the map in the

midst of all the cataclysm, then somehow get his family to these “spaceships”

in order for all of them to survive the end of the world.

The

PLAN is reiterated, in dialogue, when Cusack gets back to his family and tells

his ex-wife basically exactly what I just said above: “We’re going to go back

to the nutjob with the map so that we can get to those spaceships and get off

the planet before it collapses.”

And

lo and behold, that’s exactly what happens; it’s not only Cusack’s PLAN, but

the central action of the story, that can be summed up as a CENTRAL QUESTION: Will

Cusack be able to get his family to the spaceships before the world ends?

Or

put another way, the CENTRAL STORY ACTION is John Cusack getting his family to

the spaceships before the world ends.

(Note

the ticking clock, there, as well. And as if the end of the world weren’t

enough, the movie also starts a literal “Twenty-nine minutes to the end of the

world!” ticking computer clock at, yes, 29 minutes before the end of the movie.

I must point out here that ticking clocks are dangerous because of the huge

cliché factor. We all need to study structure to know what not to do, as well.)

And

all this happens about the end of Act I.

Remember that I said that it’s essential to have laid out the CENTRAL

QUESTION and CENTRAL STORY ACTION by the end of Act I? But also at this point –

or possibly just after the climax of Act I, in the very beginning of Act II – we

need to know what the PLAN is. PLAN and CENTRAL QUESTION are integrally

related, and I keep looking for ways to talk about it because this is such an

important concept to master.

A

reader/audience really needs to know what the overall PLAN is, even if they

only get it in a subconscious way. Otherwise they are left floundering,

wondering where the hell all of this is going.

In

2012, even in the midst of all the

buildings crumbling and crevasses opening and fires booming and planes

crashing, we understand on some level what is going on:

-

What does the protagonist want? (OUTER DESIRE) To save his

family.

-

How is he going to do it? (PLAN) By

getting the map from the nutjob and getting his family to the secret spaceships

(that aren’t really spaceships).

-

What’s standing in his way? (FORCES OF

OPPOSITION) About a million natural disasters as the planet caves in, an evil

politician who has put a billion dollar price tag on tickets for the spaceship,

a Russian Mafioso who keeps being in the same place at the same time as Cusack,

and sometimes ends up helping, and sometimes ends up hurting. (Was I the only

one queased out by the way all the Russian characters were killed off, leaving

only the most obnoxious kids on the planet?)

Here’s

another example, from a much better movie:

At

the end of the first sequence of Raiders of the Lost Ark (which

is arguably two sequences in itself, first the action sequence in the cave in

South America, then the university sequence back in the US), Indy has just finished

teaching his archeology class when his mentor, Marcus, comes to meet him with a

couple of government agents who have a job for him (CALL TO ADVENTURE). The

agents explain that Hitler has become obsessed with collecting occult artifacts

from all over the world, and is currently trying to find the legendary Lost Ark

of the Covenant, which is rumored to make any army in possession of it

invincible in battle.

So

there’s the MACGUFFIN, the object that everyone wants, and the STAKES: if

Hitler’s minions (THE ANTAGONISTS) get this Ark before Indy does, the Nazi army

will be invincible.

And

then Indy explains his PLAN to find the Ark: his old mentor, Abner Ravenwood,

was an expert on the Ark and had an ancient Egyptian medallion on which was

inscribed the instructions for using the medallion to find the hidden location

of the Ark.

So

after hearing the plan, we understand the entire OVERALL ACTION of the story:

Indy is going to find Abner (his mentor) to get the medallion, then use the

medallion to find the Ark before Hitler’s minions can get it.

And

even though there are lots of twists along the way, that’s really it: the basic

action of the story.

Generally,

PLAN and CENTRAL STORY ACTION are really the same thing – the Central Action of

the story is carrying out the specific Plan. And the CENTRAL QUESTION of the

story is – “Will the Plan succeed?”

Again,

the PLAN, CENTRAL QUESTION and CENTRAL STORY ACTION are almost always set up –

and spelled out – by the end of the first act, although the specifics of the

Plan may be spelled out right after the Act I Climax at the very beginning of

Act II.

Can

it be later? Well, anything’s possible, but the sooner a reader or audience

understands the overall thrust of the story action, the sooner they can relax

and let the story take them where it’s going to go. So much of storytelling is

about you, the author, reassuring your reader or audience that you know what

you’re doing, so they can sit back and let you drive.

If

you haven’t done this yet, take a favorite movie or book (or two or three) and

identify the PLAN, CENTRAL STORY ACTION and CENTRAL QUESTION and them in a few

sentences. Like this:

-

In Inception, the PLAN is for the

team of dream burglars to go into a corporate heir’s dreams to plant the idea

of breaking up his father’s corporation. (So the CENTRAL ACTION is going into

the corporate heir’s dream and planting the idea, and the CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will they succeed?)

-

In Sense and Sensibility, the

PLAN is for Marianne and Elinor to secure the family’s fortune and their own

happiness by marrying well. (How are they going to do that? By the period’s

equivalent of dating – which is the

CENTRAL ACTION. Yes, dating is a PLAN! The CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will the

sisters succeed in marrying well?)

-

In The Proposal, Margaret’s PLAN

is to learn enough about Andrew over the four-day weekend with his family to

pass the INS marriage test so she won’t be deported. (The CENTRAL ACTION is

going to Alaska to meet Andrew’s family and pretending to be married while they

learn enough about each other to pass the test. The CENTRAL QUESTION is: Will

they be able to successfully fake the marriage?

Now,

try it with your own story!

-

What does the protagonist WANT?

-

How does s/he PLAN to do it?

-

What and who is standing in his or her way?

For

example, in my latest thriller, Book of Shadows, here's the Act One set up: the protagonist, homicide detective Adam

Garrett, is called on to investigate the murder of a college girl, which looks

like a Satanic killing. Garrett and his partner make a quick arrest of a

classmate of the girl's, a troubled Goth musician. But Garrett is not convinced

of the boy's guilt, and when a practicing witch from nearby Salem insists the

boy is innocent and there have been other murders, he is compelled to

investigate further.

So

Garrett’s PLAN and the CENTRAL ACTION of the story is to use the witch and her

specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate the murder on his

own, all the while knowing that she is using him for her own purposes and may

well be involved in the killing.

The CENTRAL QUESTION is: will they catch the killer before s/he kills

again – and/or kills Garrett (if the witch turns out to be the killer)?

-

What does the protagonist WANT? To catch

the killer before s/he kills again.

-

How does he PLAN to do it? By using the

witch and her specialized knowledge of magical practices to investigate

further.

-

What’s standing in his way? His own

department, the killer, and possibly the witch herself. And if the witch is

right … possibly even a demon.

It’s

important to note that the Plan and Central Action of the story are not always

driven by the protagonist. Usually, yes. But in The Matrix, it’s Neo’s mentor Morpheus who has the overall

PLAN, which drives the central action right up until the end of the second act.

The Plan is to recruit and train Neo, whom Morpheus believes is “The One”

prophesied to destroy the Matrix. So that’s the action we see unfolding:

Morpheus recruiting, deprogramming and training Neo, who is admittedly very

cute, but essentially just following Morpheus’s orders for two thirds of the

movie.

Does

this weaken the structure of that film? Not at all. Morpheus drives the action

until that crucial point, the Act Two Climax, when he is abducted by the agents

of the Matrix, at which point Neo steps into his greatness and becomes “The One” by taking over the action and making a new

plan: to rescue Morpheus by sacrificing himself.

It

is a terrific way to show a huge character arc: Neo stepping into his destiny.

And I would add that this is a common structural pattern for mythic journey

stories – in Lord of the Rings, it's Gandalf who has the PLAN and drives the

reluctant Frodo in the central story action until Frodo finally takes over the

action himself.

Here’s

another example. In the very funny romantic comedy It’s Complicated, Meryl Streep’s character Jane is the protagonist,

but she doesn’t drive the action or have any particular plan of her own. It’s

her ex-husband Jake (Alec Baldwin), who seduces her and at the end of the first

act, proposes (in an extremely persuasive speech) that they continue this

affair as a perfect solution to both their love troubles – it will fulfill their sexual and intimacy needs

without disrupting the rest of their lives.

Jane

decides at that point to go along with Jake’s plan (saying, “I forgot what a

good lawyer you are”). In terms of action, she is essentially passive, letting

the two men in her life court her (which results in bigger and bigger comic

entanglements), but that makes for a more pronounced and satisfying character

arc when she finally takes a stand and breaks off the affair with Jake for

good, so she can finally move on with her life.

I

would venture to guess that most of us know what it’s like to be swept up in a

ripping good love entanglement, and can sympathize with Jane’s desire just to

go with the passion of it without having to make any pesky practical decisions.

It’s a perfectly fine – and natural – structure for a romantic comedy, as long as at that

key juncture, the protagonist has the realization and balls – or ovaries –

to take control of her own life again and make a stand for what she truly wants.

I

give you these last two examples – hopefully

– to show how helpful it can be to study

the specific structure of stories that are similar to your own. As you can see

from the above, the general writing rule that the protagonist drives the action

may not apply to what you’re

writing – and you might want to make a

different choice that will better serve your own story. And that goes for any general writing rule.

QUESTIONS:

Have you identified the CENTRAL ACTION of your story? Do you know what the protagonist's and antagonist's PLANS are? At what point

in your book does the reader have a clear idea of the protagonist’s PLAN? Is it stated aloud? Can you make it clearer

than it is?

And yes, let's hear how everyone's doing!

- Alex

(PS: To everyone who entered my Halloween giveaway drawing, I haven't forgotten you. My mistress of marketing was one of the many, many people who suffered severe flooding during the storm, and I don't want to press her on the contest right now; we'll draw winners and get the books out as soon as things have settled a little more back East. Thanks for understanding!)

Published on November 12, 2012 08:12

November 1, 2012

Ready, Set, NaNo!!!

It's here - the big day. Big month. Big everything.

The queen of suspense, Mary Higgins Clark, said about first drafts:

Writing a first draft is like clawing my way through a mountain of concrete with my bare hands.

Isn't that the truth?

Well, the point of NaNo is to write so fast that you - sometimes - forget that your hands are dripping blood. It's a stellar way of turning off your censor (we all have one of those little suckers) and just get those pages out.

So am I doing NaNo? Well, sort of. In spirit.

It seems I am NEVER at the start of a new book when November rolls around. Today I'm finishing putting in notes on my first draft of Blood Moon, the sequel to Huntress Moon. And as much as I hate to do it, I know that what I really must do is NOT look at the manuscript for a while before I reread the thing and launch into the next draft. So instead of writing, what I'm doing is a research trip up to San Francisco (I know, I have such a tough life). I need to be in my locations and figure out how certain scenes and sequences work physically. Which is definitely writing, but it's not NaNo writing.

But I'm using the Nano energy to set goals: by the end of the month I will have a book that I can get out to beta readers.

And of course, I'll be posting Nano prompts throughout the month. In fact, here's a list of helpful hints if you find yourself stuck.

1. Keep moving forward – DO NOT go back and endlessly revise your first chapters. You may end up throwing them out anyway. Just move forward. If you’re stuck on a scene, just write down vaguely what might happen in it or where it might happen as a place marker and move on to a scene you know better. The first draft can be just a sketch – the important thing is to get it all down, from beginning to end. Then you can start to layer in all the other stuff.

2. Keep the story elements checklist close at hand for easy reference.

- Story Elements Checklist for Generating Index Cards

Or if you prefer the elements in a narrative:

Narrative Structure Cheat Sheet

3. Before you start an Act, review the elements of the act you're launching into. Or if you're stuck, review the story elements of the Act you're stuck on.

- Elements of Act One

- Elements of Act Two, Part 1

- Elements of Act Two, Part 2

- Elements of Act Three

- What Makes A Great Climax?

- Elevate Your Ending

- Creating Character

4. As you're writing, you will find out more about your story. Write the premise again, and make sure you have identified and understand the Plan and Central Story Action.

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

- What's the Plan?

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action, part 2

5. When you’re stuck - make a list.

- Stuck? Make A List.

6. Do word lists of visual and thematic elements for your story to build your image systems. Start a collage book or online clip file of images if that appeals to you. Great thing to do when you're too tired to write anymore but still have a little time to spend on your book.

- Thematic Image Systems

7. Remember that the first draft is always going to suck.

- Your First Draft Is Always Going To Suck

8. You can always watch movies and do breakdowns to inspire you and break you through a block.

Good luck, everyone - and feel free to stop in and gripe! That's part of the process, too.

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

-------------------------------------------------------------------

The queen of suspense, Mary Higgins Clark, said about first drafts:

Writing a first draft is like clawing my way through a mountain of concrete with my bare hands.

Isn't that the truth?

Well, the point of NaNo is to write so fast that you - sometimes - forget that your hands are dripping blood. It's a stellar way of turning off your censor (we all have one of those little suckers) and just get those pages out.

So am I doing NaNo? Well, sort of. In spirit.

It seems I am NEVER at the start of a new book when November rolls around. Today I'm finishing putting in notes on my first draft of Blood Moon, the sequel to Huntress Moon. And as much as I hate to do it, I know that what I really must do is NOT look at the manuscript for a while before I reread the thing and launch into the next draft. So instead of writing, what I'm doing is a research trip up to San Francisco (I know, I have such a tough life). I need to be in my locations and figure out how certain scenes and sequences work physically. Which is definitely writing, but it's not NaNo writing.

But I'm using the Nano energy to set goals: by the end of the month I will have a book that I can get out to beta readers.

And of course, I'll be posting Nano prompts throughout the month. In fact, here's a list of helpful hints if you find yourself stuck.

1. Keep moving forward – DO NOT go back and endlessly revise your first chapters. You may end up throwing them out anyway. Just move forward. If you’re stuck on a scene, just write down vaguely what might happen in it or where it might happen as a place marker and move on to a scene you know better. The first draft can be just a sketch – the important thing is to get it all down, from beginning to end. Then you can start to layer in all the other stuff.

2. Keep the story elements checklist close at hand for easy reference.

- Story Elements Checklist for Generating Index Cards

Or if you prefer the elements in a narrative:

Narrative Structure Cheat Sheet

3. Before you start an Act, review the elements of the act you're launching into. Or if you're stuck, review the story elements of the Act you're stuck on.

- Elements of Act One

- Elements of Act Two, Part 1

- Elements of Act Two, Part 2

- Elements of Act Three

- What Makes A Great Climax?

- Elevate Your Ending

- Creating Character

4. As you're writing, you will find out more about your story. Write the premise again, and make sure you have identified and understand the Plan and Central Story Action.

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

- What's the Plan?

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action, part 2

5. When you’re stuck - make a list.

- Stuck? Make A List.

6. Do word lists of visual and thematic elements for your story to build your image systems. Start a collage book or online clip file of images if that appeals to you. Great thing to do when you're too tired to write anymore but still have a little time to spend on your book.

- Thematic Image Systems

7. Remember that the first draft is always going to suck.

- Your First Draft Is Always Going To Suck

8. You can always watch movies and do breakdowns to inspire you and break you through a block.

Good luck, everyone - and feel free to stop in and gripe! That's part of the process, too.

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Published on November 01, 2012 08:54

•

Tags:

alexandra-sokoloff, getting-unstuck, nanowrimo, screenwriting-tricks-for-authors, writing-process

October 31, 2012

NaNoWriMo Prep: A Process For Writing

These are such anxious days, waiting to hear from friends who were in the line of the storm. I'm hoping everyone is fine and undamaged.

But I know some of you will be launching into NaNo tomorrow and I wanted to get this post up for reference.

Obviously, NaNo is just for getting it all out of you any way you can! I'm not trying to suggest how you do that (although I do find coffee, Cheetos and chocolate help...). But if you find yourself lost somewhere in the middle of the month, there, some of these links might help.

Good luck to all, and keep us posted on everything!

- - Alex

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

A PROCESS FOR WRITING

1. First, before you start a project, even if you already have a great idea that you’re committed to, it really helps to allow yourself to do free-form brainstorming, to see what themes and characters are rolling around in your head that might just help you with the new project. And if you don’t have that great idea yet, this is the way to uncover it.

- First, You Need An Idea

2. Take a stab at writing the premise. You may not know what it is exactly, yet – that’s fine!

- What’s Your Premise?

3. See if you can identify what KIND of story it is. Again, you may not know this at early stages – don’t worry about it! Just ask the question of yourself, and keep alert for the answer.

- What KIND of Story Is It?

4. Make a Master List of movies and books in the genre of your new project, and that are structurally similar to your project (the same KIND or type of story).

- Analyzing Your Master List

5. Pick at least three of them that are MOST SIMILAR to your own story and watch them, doing a detailed story breakdown, identifying the key Story Elements, Acts, Sequences, Climaxes, etc. I really urge you to put some thought into which movies will be of the most use to your own story and not just do breakdowns for the sake of doing them – that’s fun, but it’s not the point.

- Three Act Structure Review

- The Three-Act, Eight Sequence Structure

6. At the same time, start generating index cards for your own story. Write every scene that you know or imagine in the story on index cards and stick them on a structure grid if you have a vague idea where that scene goes. Write cards for the climaxes and story elements even if you don’t know specifically what they are, yet. Allow yourself to be inspired by the movies you’re watching – let the movies show you what scenes are missing in your own story.

- The Index Card Method and Structure Grid

- Story Elements Checklist for Generating Index Cards

7. Also do word lists of visual and thematic elements for your story to start building your image systems. Start a collage book or online clip file of images if that appeals to you.

- Thematic Image Systems

8. Work back and forth between the index cards and your growing on paper or in file outline of the story. Write whole scenes out when you are inspired. Flesh out the acts by reviewing the elements of each act:

- Elements of Act One

- Elements of Act Two, Part 1

- Elements of Act Two, Part 2

- Elements of Act Three

- What Makes A Great Climax?

- Elevate Your Ending

- Creating Character

9. As you continue to work the index cards, your sequences and act climaxes will become clearer to you. These will also probably change during the writing process – that’s fine! The goal of the cards and the initial outline is a road map to help your subconscious out when you’re doing that endless slog of a first draft.

10. As you find out more about your story, write the premise again, and make sure you have identified and understand the Plan and Central Story Action.

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

- What's the Plan?

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action, part 2

11. When you’re ready to start writing from the beginning then write. Set a writing schedule and stick to it – you can sacrifice one hour of TV or playing on Facebook a night. Professional authors are people who understand that TV and social networking are the biggest waste of writing time on the planet. Do you want to veg, or do you want to create? The choice is yours.

12. Keep moving forward – DO NOT go back and endlessly revise your first chapters. You may end up throwing them out anyway. Just move forward. If you’re stuck on a scene, write down vaguely what might happen in it or where it might happen as a place marker and move on to a scene you know better. The first draft can be just a sketch – the important thing is to get it all down, from beginning to end. Then you can start to layer in all the other stuff.

13. When you’re stuck - make a list.

- Stuck? Make A List.

14. Remember that the first draft is always going to suck.

- Your First Draft Is Always Going To Suck

15. You can always watch movies and do breakdowns to inspire you and break you through a block.

16. When you reach THE END – celebrate! Most people never get anywhere near that far in their whole lives. Take several weeks off for perspective, no matter how much you want to jump back into it.

17. Then when your brain is clear, do a read through as suggested here to see what the story is that you wrote (as opposed to what you THOUGHT you were writing. Then start the rewriting process. Definitely do a re-carding of the whole story – it will have changed!

- Top Ten Things I Know About Rewriting

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

=====================================================

HALLOWEEN GIVEAWAY

Last day to sign up to win one of 31 signed hardcover copies of my spooky thrillers Book of Shadows and The Unseen .

Enter here to win!

Book of Shadows .

An ambitious Boston homicide detective must join forces with a beautiful, mysterious witch from Salem in a race to solve a series of satanic killings.

Amazon Bestseller in Horror and Police Procedurals

The Unseen

A team of research psychologists and two psychically gifted students move into an abandoned Southern mansion to duplicate a controversial poltergeist experiment, unaware that the entire original research team ended up insane... or dead.

Inspired by the real-life paranormal studies conducted by the world-famous Rhine parapsychology lab at Duke University.

But I know some of you will be launching into NaNo tomorrow and I wanted to get this post up for reference.

Obviously, NaNo is just for getting it all out of you any way you can! I'm not trying to suggest how you do that (although I do find coffee, Cheetos and chocolate help...). But if you find yourself lost somewhere in the middle of the month, there, some of these links might help.

Good luck to all, and keep us posted on everything!

- - Alex

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

A PROCESS FOR WRITING

1. First, before you start a project, even if you already have a great idea that you’re committed to, it really helps to allow yourself to do free-form brainstorming, to see what themes and characters are rolling around in your head that might just help you with the new project. And if you don’t have that great idea yet, this is the way to uncover it.

- First, You Need An Idea

2. Take a stab at writing the premise. You may not know what it is exactly, yet – that’s fine!

- What’s Your Premise?

3. See if you can identify what KIND of story it is. Again, you may not know this at early stages – don’t worry about it! Just ask the question of yourself, and keep alert for the answer.

- What KIND of Story Is It?

4. Make a Master List of movies and books in the genre of your new project, and that are structurally similar to your project (the same KIND or type of story).

- Analyzing Your Master List

5. Pick at least three of them that are MOST SIMILAR to your own story and watch them, doing a detailed story breakdown, identifying the key Story Elements, Acts, Sequences, Climaxes, etc. I really urge you to put some thought into which movies will be of the most use to your own story and not just do breakdowns for the sake of doing them – that’s fun, but it’s not the point.

- Three Act Structure Review

- The Three-Act, Eight Sequence Structure

6. At the same time, start generating index cards for your own story. Write every scene that you know or imagine in the story on index cards and stick them on a structure grid if you have a vague idea where that scene goes. Write cards for the climaxes and story elements even if you don’t know specifically what they are, yet. Allow yourself to be inspired by the movies you’re watching – let the movies show you what scenes are missing in your own story.

- The Index Card Method and Structure Grid

- Story Elements Checklist for Generating Index Cards

7. Also do word lists of visual and thematic elements for your story to start building your image systems. Start a collage book or online clip file of images if that appeals to you.

- Thematic Image Systems

8. Work back and forth between the index cards and your growing on paper or in file outline of the story. Write whole scenes out when you are inspired. Flesh out the acts by reviewing the elements of each act:

- Elements of Act One

- Elements of Act Two, Part 1

- Elements of Act Two, Part 2

- Elements of Act Three

- What Makes A Great Climax?

- Elevate Your Ending

- Creating Character

9. As you continue to work the index cards, your sequences and act climaxes will become clearer to you. These will also probably change during the writing process – that’s fine! The goal of the cards and the initial outline is a road map to help your subconscious out when you’re doing that endless slog of a first draft.

10. As you find out more about your story, write the premise again, and make sure you have identified and understand the Plan and Central Story Action.

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

- What's the Plan?

- Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action, part 2

11. When you’re ready to start writing from the beginning then write. Set a writing schedule and stick to it – you can sacrifice one hour of TV or playing on Facebook a night. Professional authors are people who understand that TV and social networking are the biggest waste of writing time on the planet. Do you want to veg, or do you want to create? The choice is yours.

12. Keep moving forward – DO NOT go back and endlessly revise your first chapters. You may end up throwing them out anyway. Just move forward. If you’re stuck on a scene, write down vaguely what might happen in it or where it might happen as a place marker and move on to a scene you know better. The first draft can be just a sketch – the important thing is to get it all down, from beginning to end. Then you can start to layer in all the other stuff.

13. When you’re stuck - make a list.

- Stuck? Make A List.

14. Remember that the first draft is always going to suck.

- Your First Draft Is Always Going To Suck

15. You can always watch movies and do breakdowns to inspire you and break you through a block.

16. When you reach THE END – celebrate! Most people never get anywhere near that far in their whole lives. Take several weeks off for perspective, no matter how much you want to jump back into it.

17. Then when your brain is clear, do a read through as suggested here to see what the story is that you wrote (as opposed to what you THOUGHT you were writing. Then start the rewriting process. Definitely do a re-carding of the whole story – it will have changed!

- Top Ten Things I Know About Rewriting

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

=====================================================

HALLOWEEN GIVEAWAY

Last day to sign up to win one of 31 signed hardcover copies of my spooky thrillers Book of Shadows and The Unseen .

Enter here to win!

Book of Shadows .

An ambitious Boston homicide detective must join forces with a beautiful, mysterious witch from Salem in a race to solve a series of satanic killings.

Amazon Bestseller in Horror and Police Procedurals

The Unseen

A team of research psychologists and two psychically gifted students move into an abandoned Southern mansion to duplicate a controversial poltergeist experiment, unaware that the entire original research team ended up insane... or dead.

Inspired by the real-life paranormal studies conducted by the world-famous Rhine parapsychology lab at Duke University.

Published on October 31, 2012 13:54

October 28, 2012

NaNoWriMo Prep: Thematic Image Systems

I couldn't send you all off to do NaNo without taking you through one of my all-time favorite writing exercises, the one I get the most raves about when I do my workshops.

But first, we need to talk about theme. I’m not here to define theme, today...

Oh, is that cheating?

Well, okay, if you insist. Theme is what the story is about. On a deeper level than the plot details. The big meaning. Usually a moral meaning.

Hmm. See why I don’t want to define it?

Well, how about defining by example?

I’ve heard, often, “Huck Finn is about the inhumanity of racism.”

Uh...

I don't know about you, but for me, that's too soft and vague. You

could write about five billion different stories on that.

Also

have heard a lot that the theme of Romeo and Juliet is “Great love

defies even death.” Except that – in the end, they’re dead, right? So

how exactly is the love defying death? Risking death and losing,

maybe. Inspiring people after death, maybe.

Okay, how

about this? “A man is never truly alone who has friends” is a great

statement of the theme of It’s A Wonderful Life. (And stated overtly

in the end of that movie.)

The trouble is, I personally

think it’s closer to the soul of that movie to say that it’s the

little, ordinary actions we do every day that add up to true heroism.

So

defining theme has always seemed like a slippery process to me.

Different people can pull vastly different interpretations of the theme

of a story from the same story. And even if you can cleverly distill

the meaning of a story into one sentence… admit it, you’re not REALLY

covering everything that the story is about, are you?

I

think it’s more useful to think of theme as layers of meaning. To

think of theme not as a sentence, but as a whole image system.

And

that’s where it gets really fun to start working with theme – when it’s

not just some pedantic sentence, but a whole world of interrelated

meanings, that resonate on levels that you’re not even aware of,

sometimes, but that stay with you and bring you back to certain stories

over and over and over again.

(Think of some of the

dreams you have - maybe – where there will be double and triple puns,

visual and verbal. I had a dream last night, in fact, that had just

about every possible act, object, setting and word variation on

"counter").

There are all kinds of ways to work theme

into a story. The most obvious is the PLOT. Every plot is also a

statement of theme.

It’s A Wonderful Life is a great,

great example of plot reflecting theme. George Bailey’s desire in the

beginning of the film is to be a hero, to do big, important things.

Throughout the story, that desire seems to be thwarted at every turn by

the ordinariness of his life. And yet, every single encounter George

Bailey has is an example of a small, ordinary goodness, a right choice

that George makes, that in the end, when we and he see the town as it

would have been if he had never existed, lets us understand that it IS

those little things that make for true heroism.

Presumed