Alexandra Sokoloff's Blog, page 25

December 24, 2013

Top Ten Holiday Movies

The best thing about Christmas, besides champagne, is Christmas movies (and okay, what I really mean is HOLIDAY movies, but when I say Christmas I say it as a total pagan, so just back off).

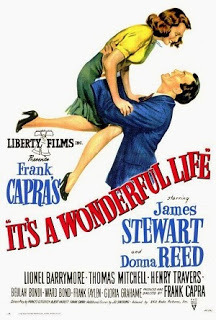

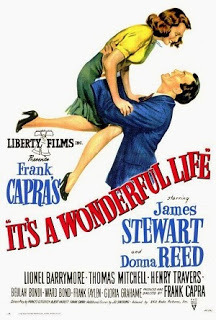

Today I'm seeing my all-time favorite, IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE, on the big screen for the first time. Can't beat that for Christmas Eve!!

But you all know how I love lists, so here it is, the Top Ten Holiday Movie List.

IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE

A non-escapist fantasy that puts you through the emotional wringer only to emerge the feel-good - that's, feel GOOD - film of all time.

Used to show it to my gang kids in prison school – it remains one of the all-time highlights of my life to see those kids start out whining that I was showing them a black and white film and then watch them fall under this movie’s spell. Oh man, did they GET it.

HOLIDAY

HOLIDAY

George Cukor directing a Donald Ogden Stewart & Sidney Buchman adaptation of a Philip Barry play starring Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn. Anything else you need to know?

PHILADELPHIA STORY

See above, plus Jimmy Stewart, and the brilliant and under-known Ruth Hussey (“Oh, I just photograph well.”) and Virginia Weidler as the weirdest little sister on the planet (“I did it. I did it ALL.”) Not a holiday movie, per se, but if you’re looking for cheer...

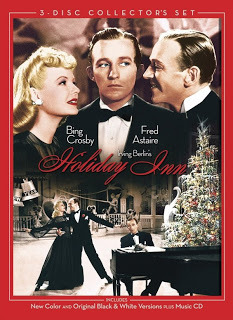

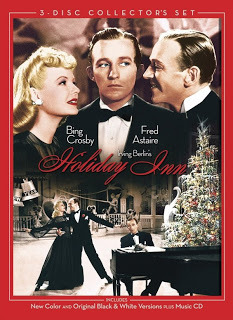

HOLIDAY INN

HOLIDAY INN

The ultimate escapist fantasy. Yes, let me make a living doing 12 live shows a year, simultaneously keeping two men at my beck and call, one who sings, one who dances. Where do I sign? Best line: “But I do love you, Jim. I love everybody.” Best song: “Be Careful, It’s My Heart”. Best dance - Fred and the firecrackers. Best cat-fight moment: Marjorie Reynolds trying to look contented with Bing Crosby while Fred is dancing up a storm with Virginia Dale. (But be sure to get the one with the appalling Lincoln's birthday sequence edited out...)

RUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER

Best Christmas musical soundtrack there is – one great song after another - only the whole thing makes me cry so hard I generally end up avoiding it.

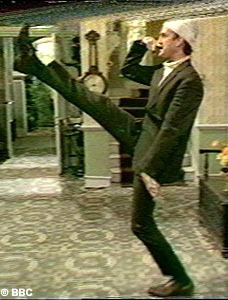

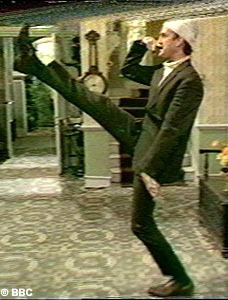

FAWLTY TOWERS

FAWLTY TOWERS

BBC series written by and starring John Cleese and Connie Booth, with Cleese as the most incompetent innkeeper in the history of innkeeping. The entire series is genius, every single episode - not exactly holiday themed, either, but guaranteed healer of depression and all other ills. Be prepared to laugh until you're sick.

ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS

My brother turned the fam onto AB FAB and now it just wouldn’t be a holiday without Patsy and Eddy and Saffy. Sin is in, sweetie.

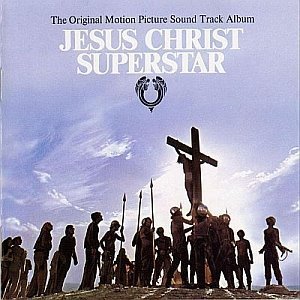

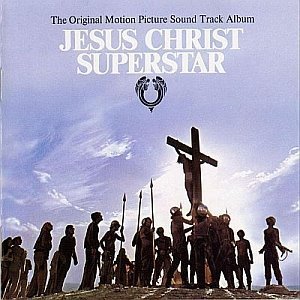

GODSPELL and JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR

GODSPELL and JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR

Okay, so I’m not technically a Christian or anything, but I can see God in those two shows.

So give. What movies mean Christmas, or the equivalent, to YOU?

Have a wonderful holiday!!!

- Alex

Today I'm seeing my all-time favorite, IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE, on the big screen for the first time. Can't beat that for Christmas Eve!!

But you all know how I love lists, so here it is, the Top Ten Holiday Movie List.

IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE

A non-escapist fantasy that puts you through the emotional wringer only to emerge the feel-good - that's, feel GOOD - film of all time.

Used to show it to my gang kids in prison school – it remains one of the all-time highlights of my life to see those kids start out whining that I was showing them a black and white film and then watch them fall under this movie’s spell. Oh man, did they GET it.

HOLIDAY

HOLIDAYGeorge Cukor directing a Donald Ogden Stewart & Sidney Buchman adaptation of a Philip Barry play starring Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn. Anything else you need to know?

PHILADELPHIA STORY

See above, plus Jimmy Stewart, and the brilliant and under-known Ruth Hussey (“Oh, I just photograph well.”) and Virginia Weidler as the weirdest little sister on the planet (“I did it. I did it ALL.”) Not a holiday movie, per se, but if you’re looking for cheer...

HOLIDAY INN

HOLIDAY INNThe ultimate escapist fantasy. Yes, let me make a living doing 12 live shows a year, simultaneously keeping two men at my beck and call, one who sings, one who dances. Where do I sign? Best line: “But I do love you, Jim. I love everybody.” Best song: “Be Careful, It’s My Heart”. Best dance - Fred and the firecrackers. Best cat-fight moment: Marjorie Reynolds trying to look contented with Bing Crosby while Fred is dancing up a storm with Virginia Dale. (But be sure to get the one with the appalling Lincoln's birthday sequence edited out...)

RUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER

Best Christmas musical soundtrack there is – one great song after another - only the whole thing makes me cry so hard I generally end up avoiding it.

FAWLTY TOWERS

FAWLTY TOWERSBBC series written by and starring John Cleese and Connie Booth, with Cleese as the most incompetent innkeeper in the history of innkeeping. The entire series is genius, every single episode - not exactly holiday themed, either, but guaranteed healer of depression and all other ills. Be prepared to laugh until you're sick.

ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS

My brother turned the fam onto AB FAB and now it just wouldn’t be a holiday without Patsy and Eddy and Saffy. Sin is in, sweetie.

GODSPELL and JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR

GODSPELL and JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAROkay, so I’m not technically a Christian or anything, but I can see God in those two shows.

So give. What movies mean Christmas, or the equivalent, to YOU?

Have a wonderful holiday!!!

- Alex

Published on December 24, 2013 03:52

December 10, 2013

Nanowrimo Now What: Rewriting

Now that we've had some time off from the frenzy of writing that was November, we need to get back to those drafts and - yike - see what we've got.

Remember, the most important thing is taking enough time off from that draft. But now that you have taken the time off… how the hell do you proceed with the second draft?

Well, first you have to read the first draft. All the way through. Not necessarily in one sitting (if that’s even possible to begin with!). I usually do this in chunks of 50 pages or 100 pages a day – anything else makes my brain sore.

(And yes, if you’ve been paying attention (The Three Act Structure and The Eight Sequence Structure), that would mean I’m either reading one sequence or two sequences a day).

I picked up a tip from some book or article a long time ago about reading for revisions, and I wish I could remember who said it to credit them, because it’s great advice. Grab yourself a colored pen or pencil (or all kinds of colors, glitter pens - go wild) and sit down with a stack of freshly printed pages (sorry, it’s ungreen, but I can’t do a first revision on a screen. I need a hard copy). Then read through and make brief notes where necessary, but DO NOT start rewriting, and PUT THE PEN DOWN as soon as you’ve made a note. You want to read the first time through for story, not for stupid details that will interrupt your experience of the story as a whole. You want to get the big picture – especially – you want to see if you actually have a book (or film, if that’s what you’re writing).

If your drafts are anything like mine, there will be large chunks of absolute shit. That’s pretty much my definition of what a first draft is. X them out on the spot if you have to, but resist the temptation to stop and rewrite. Well, if you REALLY are hot to write a scene, I guess, okay, but really, unless you are totally, fanatically inspired, it’s better just to make brief notes.

When you’ve finished reading there should - hopefully! - be the feeling that even though you probably still have massive amounts of work yet to do, there is a book there. (I love that feeling…)

Once I’ve read through the entire thing, I make notes about my impressions, and then usually I will do a re-card (see The Index Card Method). I will have made many scribbled notes on the draft to the effect of “This scene doesn’t work here!” In some of my first drafts, whole sections don’t work at all. This is my chance to find the right places for things. And, of course, throw stuff out.

I will go through the entire book again – going back and forth between my pages and the cards on my story grid - and see where the story elements fall. There is no script or book I’ve ever written that didn’t benefit from a careful overview once again identifying act breaks, sequence climaxes, and key story elements like: The Call to Adventure; Stating the Theme; identifying the Central Question; Central Action and Plan; Crossing the Threshold; Meeting the Mentor; the Dark Night of the Soul - once the first draft is actually finished. A lot of your outline may have changed, and you will be able to pull your story into line much more effectively if you check your structural elements again and continually be thinking of how you can make those key scenes more significant, more magical.

(For a quick refresher on Story Elements, skip down to #10 at the bottom of this post, and the links at the end for more in-depth discussion.)

Also, be very aware of what your sequences are. If a scene isn’t working, but you know you need to have it, it’s probably in the wrong sequence, and if you look at your story overall and at what each sequence is doing, you’ll probably be able to see immediately where stray scenes need to go. That’s why re-carding and re-sequencing is such a great thing to do when you start a revision.

Now, the next steps can be taken in whatever order is useful to you, but here again are the Top Ten Things I Know About Editing.

1. Cut, cut, cut.

When you first start writing, you are reluctant to cut anything. Believe me, I remember. But the truth is, beginning writers very, very, VERY often duplicate scenes, and characters, too. And dialogue, oh man, do inexperienced writers duplicate dialogue! The same things happen over and over again, are said over and over again. It will be less painful for you to cut if you learn to look for and start to recognize when you’re duplicating scenes, actions, characters and dialogue. Those are the obvious places to cut and combine.

Some very wise writer (unfortunately I have no idea who) said, “If it occurs to you to cut, do so.” This seems harsh and scary, I know. Often I’ll flag something in a manuscript as “Could cut”, and leave it in my draft for several passes until I finally bite the bullet and get rid of it. So, you know, that’s fine. Allow yourself to CONSIDER cutting something, first. No commitment! Then if you do, fine. But once you’ve considered cutting, you almost always will. It's okay if you bitch about it all the way to the trash file, too - I always do.

2. Find a great critique group.

This is easier said than done, but you NEED a group, or a series of readers, who will commit themselves to making your work the best it can be, just as you commit the same to their work. Editors don’t edit the way they used to and publishing houses expect their authors to find friends to do that kind of intensive editing. Really.

3. Do several passes.

Finish your first draft, no matter how rough it is. Then give yourself a break — a week is good, two weeks is better, three weeks is better than that — as time permits. Then read, cut, polish, put in notes. Repeat. And repeat again. Always give yourself time off between reads if you can. The closer your book is to done, the more uncomfortable the unwieldy sections will seem to you, and you will be more and more okay with getting rid of them. Read on for the specific kinds of passes I recommend doing.

4. Whatever your genre is, do a dedicated pass focusing on that crucial genre element.

For a thriller: thrills and suspense. For a mystery: clues and misdirection and suspense. For a comedy: a comedic pass. For a romance: a sex pass. Or “emotional” pass, if you must call it that. For horror… well, you get it.

I write suspense. So after I’ve written that first agonizing bash-through draft of a book or script, and probably a second or third draft just to make it readable, I will at some point do a dedicated pass just to amp up the suspense, and I highly recommend trying it, because it’s amazing how many great ideas you will come up with for suspense scenes (or comic scenes, or romantic scenes) if you are going through your story JUST focused on how to inject and layer in suspense, or horror, or comedy, or romance. It’s your JOB to deliver the genre you’re writing in. It’s worth a dedicated pass to make sure you’re giving your readers what they’re buying the book for.

5. Know your Three Act Structure.

If something in your story is sagging, it is amazing how quickly you can pull your narrative into line by looking at the scene or sequence you have around page 100 (or whatever page is ¼ way through the book), page 200, (or whatever page is ½ way through the book), page 300 (or whatever page is ¾ through the book) and your climax. Each of those scenes should be huge, pivotal, devastating, game-changing scenes or sequences (even if it’s just emotional devastation). Those four points are the tentpoles of your story.

6. Do a dedicated DESIRE LINE pass in which you ask yourself for every scene: “What does this character WANT? Who is opposing her/him in this scene? Who WINS in the scene? What will they do now?”

7. Do a dedicated EMOTIONAL pass, in which you ask yourself in every chapter, every scene, what do I want my readers to FEEL in this moment?

8. Do a dedicated SENSORY pass, in which you make sure you’re covering what you want the reader to see, hear, feel, taste, smell, and sense.

9. Read your book aloud. All of it. Cover to cover.

I wouldn’t recommend doing this with a first draft unless you feel it’s very close to the final product, but when you’re further along, the best thing I know to do to edit a book — or script — is read it aloud. The whole thing. I know, this takes several days, and you will lose your voice. Get some good cough drops. But there is no better way to find errors — spelling, grammar, continuity, and rhythmic errors. Try it, you’ll be amazed.

10. Finally, and this is a big one: steal from film structure to pull your story into dramatic line.

Some of you are already well aware that I’ve compiled a checklist of story elements that I use both when I’m brainstorming a story on index cards, and again when I’m starting to revise. I find it invaluable to go through my first draft and make sure I’m hitting all of these points, so here it is again, for those just finding this post.

STORY ELEMENTS CHECKLIST

ACT ONE

* Opening image* Meet the hero or heroine* Hero/ine’s inner and outer desire.* Hero/ine’s problem* Hero/ine’s ghost or wound* Hero/ine’s arc* Inciting Incident/Call to Adventure* Meet the antagonist (and/or introduce a mystery, which is what you do when you’re going to keep your antagonist hidden to reveal at the end)* State the theme/what’s the story about?* Allies* Mentor (possibly. May not have one or may be revealed later in the story).* Love interest* Plant/Reveal (or: Setups and Payoffs)* Hope/Fear (and Stakes)* Time Clock (possibly. May not have one or may be revealed later in the story)* Sequence One climax* Central Question* Central Story Action* Plan (Hero/ine's)* Villain's Plan* Act One climax

___________________________

ACT TWO

* Crossing the Threshold/ Into the Special World (may occur in Act One)* Threshold Guardian (maybe)* Hero/ine’s Plan* Antagonist’s Plan* Training Sequence* Series of Tests* Picking up new Allies* Assembling the Team* Attacks by the Antagonist (whether or not the Hero/ine recognizes these as being from the antagonist)* In a detective story, questioning witnesses, lining up and eliminating suspects, following clues.

THE MIDPOINT

* Completely changes the game* Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action* Can be a huge revelation* Can be a huge defeat* Can be a “now it’s personal” loss* Can be sex at 60 — the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

______________________________ACT TWO, PART TWO

* Recalibrating — after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the Midpoint, the hero/ine must Revamp The Plan and try a New Mode of Attack.* Escalating Actions/ Obsessive Drive* Hard Choices and Crossing The Line (immoral actions by the main character to get what s/he wants)* Loss of Key Allies (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).* A Ticking Clock (can happen anywhere in the story)* Reversals and Revelations/Twists. (Hmm, that clearly should have its own post, now, shouldn't it?)* The Long Dark Night of the Soul and/or Visit to Death (aka All Is Lost)

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often can be a final revelation before the end game: the knowledge of who the opponent really is* Answers the Central Question

_______________________________

ACT THREE

The third act is basically the Final Battle and Resolution. It can often be one continuous sequence — the chase and confrontation, or confrontation and chase. There may be a final preparation for battle, or it might be done on the fly. Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelations of the second act.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It is often divided into two sequences:

1. Getting there (storming the castle)2. The final battle itself

* Thematic Location — often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare* The protagonist’s character change* The antagonist’s character change (if any)* Possibly allies’ character changes and/or gaining of desire* Could be one last huge reveal or twist, or series of reveals and twists, or series of final payoffs you've been saving (as in BACK TO THE FUTURE and IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE).

* RESOLUTION: A glimpse into the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it.

If these story elements are new to you, you’ll want to read:

Elements of Act One

Elements of Act Two, Part 1

Elements of Act Two, Part 2

Elements of Act Three

Elements of Act Three: Elevate Your Ending

Elements of Act Three: What Makes a Great Climax?

Act Climaxes and Turning Points

Part 1:

Part 2:

And I'll be posting more about how to do different kinds of passes for particular effect. But for now, I think all of the above should keep you busy for a few days...

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Remember, the most important thing is taking enough time off from that draft. But now that you have taken the time off… how the hell do you proceed with the second draft?

Well, first you have to read the first draft. All the way through. Not necessarily in one sitting (if that’s even possible to begin with!). I usually do this in chunks of 50 pages or 100 pages a day – anything else makes my brain sore.

(And yes, if you’ve been paying attention (The Three Act Structure and The Eight Sequence Structure), that would mean I’m either reading one sequence or two sequences a day).

I picked up a tip from some book or article a long time ago about reading for revisions, and I wish I could remember who said it to credit them, because it’s great advice. Grab yourself a colored pen or pencil (or all kinds of colors, glitter pens - go wild) and sit down with a stack of freshly printed pages (sorry, it’s ungreen, but I can’t do a first revision on a screen. I need a hard copy). Then read through and make brief notes where necessary, but DO NOT start rewriting, and PUT THE PEN DOWN as soon as you’ve made a note. You want to read the first time through for story, not for stupid details that will interrupt your experience of the story as a whole. You want to get the big picture – especially – you want to see if you actually have a book (or film, if that’s what you’re writing).

If your drafts are anything like mine, there will be large chunks of absolute shit. That’s pretty much my definition of what a first draft is. X them out on the spot if you have to, but resist the temptation to stop and rewrite. Well, if you REALLY are hot to write a scene, I guess, okay, but really, unless you are totally, fanatically inspired, it’s better just to make brief notes.

When you’ve finished reading there should - hopefully! - be the feeling that even though you probably still have massive amounts of work yet to do, there is a book there. (I love that feeling…)

Once I’ve read through the entire thing, I make notes about my impressions, and then usually I will do a re-card (see The Index Card Method). I will have made many scribbled notes on the draft to the effect of “This scene doesn’t work here!” In some of my first drafts, whole sections don’t work at all. This is my chance to find the right places for things. And, of course, throw stuff out.

I will go through the entire book again – going back and forth between my pages and the cards on my story grid - and see where the story elements fall. There is no script or book I’ve ever written that didn’t benefit from a careful overview once again identifying act breaks, sequence climaxes, and key story elements like: The Call to Adventure; Stating the Theme; identifying the Central Question; Central Action and Plan; Crossing the Threshold; Meeting the Mentor; the Dark Night of the Soul - once the first draft is actually finished. A lot of your outline may have changed, and you will be able to pull your story into line much more effectively if you check your structural elements again and continually be thinking of how you can make those key scenes more significant, more magical.

(For a quick refresher on Story Elements, skip down to #10 at the bottom of this post, and the links at the end for more in-depth discussion.)

Also, be very aware of what your sequences are. If a scene isn’t working, but you know you need to have it, it’s probably in the wrong sequence, and if you look at your story overall and at what each sequence is doing, you’ll probably be able to see immediately where stray scenes need to go. That’s why re-carding and re-sequencing is such a great thing to do when you start a revision.

Now, the next steps can be taken in whatever order is useful to you, but here again are the Top Ten Things I Know About Editing.

1. Cut, cut, cut.

When you first start writing, you are reluctant to cut anything. Believe me, I remember. But the truth is, beginning writers very, very, VERY often duplicate scenes, and characters, too. And dialogue, oh man, do inexperienced writers duplicate dialogue! The same things happen over and over again, are said over and over again. It will be less painful for you to cut if you learn to look for and start to recognize when you’re duplicating scenes, actions, characters and dialogue. Those are the obvious places to cut and combine.

Some very wise writer (unfortunately I have no idea who) said, “If it occurs to you to cut, do so.” This seems harsh and scary, I know. Often I’ll flag something in a manuscript as “Could cut”, and leave it in my draft for several passes until I finally bite the bullet and get rid of it. So, you know, that’s fine. Allow yourself to CONSIDER cutting something, first. No commitment! Then if you do, fine. But once you’ve considered cutting, you almost always will. It's okay if you bitch about it all the way to the trash file, too - I always do.

2. Find a great critique group.

This is easier said than done, but you NEED a group, or a series of readers, who will commit themselves to making your work the best it can be, just as you commit the same to their work. Editors don’t edit the way they used to and publishing houses expect their authors to find friends to do that kind of intensive editing. Really.

3. Do several passes.

Finish your first draft, no matter how rough it is. Then give yourself a break — a week is good, two weeks is better, three weeks is better than that — as time permits. Then read, cut, polish, put in notes. Repeat. And repeat again. Always give yourself time off between reads if you can. The closer your book is to done, the more uncomfortable the unwieldy sections will seem to you, and you will be more and more okay with getting rid of them. Read on for the specific kinds of passes I recommend doing.

4. Whatever your genre is, do a dedicated pass focusing on that crucial genre element.

For a thriller: thrills and suspense. For a mystery: clues and misdirection and suspense. For a comedy: a comedic pass. For a romance: a sex pass. Or “emotional” pass, if you must call it that. For horror… well, you get it.

I write suspense. So after I’ve written that first agonizing bash-through draft of a book or script, and probably a second or third draft just to make it readable, I will at some point do a dedicated pass just to amp up the suspense, and I highly recommend trying it, because it’s amazing how many great ideas you will come up with for suspense scenes (or comic scenes, or romantic scenes) if you are going through your story JUST focused on how to inject and layer in suspense, or horror, or comedy, or romance. It’s your JOB to deliver the genre you’re writing in. It’s worth a dedicated pass to make sure you’re giving your readers what they’re buying the book for.

5. Know your Three Act Structure.

If something in your story is sagging, it is amazing how quickly you can pull your narrative into line by looking at the scene or sequence you have around page 100 (or whatever page is ¼ way through the book), page 200, (or whatever page is ½ way through the book), page 300 (or whatever page is ¾ through the book) and your climax. Each of those scenes should be huge, pivotal, devastating, game-changing scenes or sequences (even if it’s just emotional devastation). Those four points are the tentpoles of your story.

6. Do a dedicated DESIRE LINE pass in which you ask yourself for every scene: “What does this character WANT? Who is opposing her/him in this scene? Who WINS in the scene? What will they do now?”

7. Do a dedicated EMOTIONAL pass, in which you ask yourself in every chapter, every scene, what do I want my readers to FEEL in this moment?

8. Do a dedicated SENSORY pass, in which you make sure you’re covering what you want the reader to see, hear, feel, taste, smell, and sense.

9. Read your book aloud. All of it. Cover to cover.

I wouldn’t recommend doing this with a first draft unless you feel it’s very close to the final product, but when you’re further along, the best thing I know to do to edit a book — or script — is read it aloud. The whole thing. I know, this takes several days, and you will lose your voice. Get some good cough drops. But there is no better way to find errors — spelling, grammar, continuity, and rhythmic errors. Try it, you’ll be amazed.

10. Finally, and this is a big one: steal from film structure to pull your story into dramatic line.

Some of you are already well aware that I’ve compiled a checklist of story elements that I use both when I’m brainstorming a story on index cards, and again when I’m starting to revise. I find it invaluable to go through my first draft and make sure I’m hitting all of these points, so here it is again, for those just finding this post.

STORY ELEMENTS CHECKLIST

ACT ONE

* Opening image* Meet the hero or heroine* Hero/ine’s inner and outer desire.* Hero/ine’s problem* Hero/ine’s ghost or wound* Hero/ine’s arc* Inciting Incident/Call to Adventure* Meet the antagonist (and/or introduce a mystery, which is what you do when you’re going to keep your antagonist hidden to reveal at the end)* State the theme/what’s the story about?* Allies* Mentor (possibly. May not have one or may be revealed later in the story).* Love interest* Plant/Reveal (or: Setups and Payoffs)* Hope/Fear (and Stakes)* Time Clock (possibly. May not have one or may be revealed later in the story)* Sequence One climax* Central Question* Central Story Action* Plan (Hero/ine's)* Villain's Plan* Act One climax

___________________________

ACT TWO

* Crossing the Threshold/ Into the Special World (may occur in Act One)* Threshold Guardian (maybe)* Hero/ine’s Plan* Antagonist’s Plan* Training Sequence* Series of Tests* Picking up new Allies* Assembling the Team* Attacks by the Antagonist (whether or not the Hero/ine recognizes these as being from the antagonist)* In a detective story, questioning witnesses, lining up and eliminating suspects, following clues.

THE MIDPOINT

* Completely changes the game* Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action* Can be a huge revelation* Can be a huge defeat* Can be a “now it’s personal” loss* Can be sex at 60 — the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

______________________________ACT TWO, PART TWO

* Recalibrating — after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the Midpoint, the hero/ine must Revamp The Plan and try a New Mode of Attack.* Escalating Actions/ Obsessive Drive* Hard Choices and Crossing The Line (immoral actions by the main character to get what s/he wants)* Loss of Key Allies (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).* A Ticking Clock (can happen anywhere in the story)* Reversals and Revelations/Twists. (Hmm, that clearly should have its own post, now, shouldn't it?)* The Long Dark Night of the Soul and/or Visit to Death (aka All Is Lost)

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often can be a final revelation before the end game: the knowledge of who the opponent really is* Answers the Central Question

_______________________________

ACT THREE

The third act is basically the Final Battle and Resolution. It can often be one continuous sequence — the chase and confrontation, or confrontation and chase. There may be a final preparation for battle, or it might be done on the fly. Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelations of the second act.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It is often divided into two sequences:

1. Getting there (storming the castle)2. The final battle itself

* Thematic Location — often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare* The protagonist’s character change* The antagonist’s character change (if any)* Possibly allies’ character changes and/or gaining of desire* Could be one last huge reveal or twist, or series of reveals and twists, or series of final payoffs you've been saving (as in BACK TO THE FUTURE and IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE).

* RESOLUTION: A glimpse into the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it.

If these story elements are new to you, you’ll want to read:

Elements of Act One

Elements of Act Two, Part 1

Elements of Act Two, Part 2

Elements of Act Three

Elements of Act Three: Elevate Your Ending

Elements of Act Three: What Makes a Great Climax?

Act Climaxes and Turning Points

Part 1:

Part 2:

And I'll be posting more about how to do different kinds of passes for particular effect. But for now, I think all of the above should keep you busy for a few days...

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Published on December 10, 2013 01:40

December 3, 2013

Nanowrimo Now What?

YAY!!! You survived! Or maybe I shouldn’t make any assumptions, there.

But for the sake of argument, let’s say you survived and now have a rough draft (maybe very, very, very rough draft) of about 50,000 words.

What next?

Well, first of all, did you write to “The End”? Because if not, then you may have survived, but you’re not done. You must get through to The End, no matter how rough it is (rough meaning the process AND the pages…). If you did not get to The End, I would strongly urge that you NOT take a break, no matter how tired you are (well, maybe a day). You can slow down your schedule, set a lower per-day word or page count, but do not stop. Write every day, or every other day if that’s your schedule, but get the sucker done.

You may end up throwing away most of what you write, but it is a really, really, really bad idea not to get all the way through a story. That is how most books, scripts and probably most all other things in life worth doing are abandoned.

Conversely, if you DID get all the way to “The End”, then definitely, take a break. As long a break as possible. You should keep to a writing schedule, start brainstorming the next project, maybe do some random collaging to see what images come up that might lead to something fantastic - but if you have a completed draft, then what you need right now is SPACE from it. You are going to need fresh eyes to do the read-through that is going to take you to the next level, and the only way for you to get those fresh eyes is to leave the story alone for a while.

I am tempted to jump write in and post the blog I am thinking about on a process for reading and revising, but I will resist, at least for today, so that you really absorb what I’m saying.

1. Keep going if you’re not done –

OR -

2. Take a good long break if you have a whole first draft, and if you MUST think about writing, maybe start thinking about another project.

And in the meantime, I’d love to hear how you all who were Nanoing did.

Me? I bashed my way through to the end of Cold Moon, the third in my Huntress Moon series (with LOTS of research trips in Northern California along the way....) Of course it's not as done as I want it to be, but I managed to get through that "I will NEVER finish this bloody thing" stage into the "Wow, I may not be done yet but this is way too good to abandon now" stage, which is not exactly the home stretch yet but it is a major corner to turn. A good month!

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Published on December 03, 2013 08:00

November 23, 2013

Nanowrimo: The Third Quarter Drop-Dead

Home stretch!

Well, theoretically, anyway. But I find that right about now is when people tend to start dropping during Nano. First of all there's, well, Thanksgiving. Which even though it's a holiday, involves family, and family is never conducive to marathon writing. (They don't like to lose us to a book, it's just the truth. It brings up all kinds of feelings of abandonment and inadequacy. So - pretend you're going shopping and go to a cafe to write, that's what they're for.)

But also, let's face it, it's EASY to write a first act. It's new, it's fresh, it's exciting, it's like the first flush of being in love. You're so high you don't stop to think, and that means you don't get in your own way.

It can even be not so hard to get through Act II, part 1 to the Midpoint. But it's that third quarter where things get murky. You feel like you're not getting anywhere. In fact, you have no freaking clue where you are, or why in the hell you're wherever the hell you are to begin with, and you just want to give up and sleep for a week, or eat turkey and chocolate for a week, or all of the above.

I had a friend in movie development who called it "the third-quarter drop dead."

Well, here's an interesting thing. Structurally, this is EXACTLY the point in your story that your hero/ine is feeling those exact same things. In other words, it's the BLACK MOMENT, or ALL IS LOST MOMENT, or the VISIT TO DEATH, which almost always ends up as the climax or just before the climax of Act II.

It's as if we as authors have to work ourselves into the exact same hopeless despair as our characters, as if nothing good will ever come out of this situation and we might as well give up right now - in order to convey that emotion on the page and feel that exhilaration when the character SOLVES the problem and gets that final revelation and makes that final plan.

So if you find yourself in this situation, you might want to review the elements of Act II: Part 2, and take a look at some of these questions to see if they might help you find your way.

ACT II:2

In a 2-hour movie this section starts at about 60 minutes, and ends at about 90 minutes.

In a 400-page book, this section starts at about p. 300 and ends toward the end of the book.

Now, remember, at the end of Act II, part 1, there is a MIDPOINT CLIMAX, which I'll review briefly because it's so important.

In movies the midpoint is usually a big SETPIECE scene, where the filmmakers really show off their expertise with a special effects sequence (as in HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON and HARRY POTTER, 1), or a big action scene (JAWS), or in breathtaking psychological cat-and-mouse dialogue (in SILENCE OF THE LAMBS). It might be a sex scene or a comedy scene, or both in a romantic comedy. Whatever the Midpoint is, it is most likely going to be specific to the promise of the genre.

And I strongly encourage you as authors to pay as much attention to your midpoint as filmmakers do with theirs.

THE MIDPOINT –

- Completely changes the game

- Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

- Is a point of no return

- Can be a huge revelation

- Can be a huge defeat

- Can be a huge win

- Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

- Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

(More on MIDPOINT).

Act II, part 2 will almost always have these elements:

* RECALIBRATING– after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the midpoint, the hero/ine must REVAMP THE PLAN and try a NEW MODE OF ATTACK.

What’s the new plan?

* STAKES

A good story will always be clear about the stakes. Characters often speak the stakes aloud. How have the stakes changed? Do we have new hopes or fears about what the protagonist will do and what will happen to him or her?

* ESCALATING ACTIONS/OBSESSIVE DRIVE

Little actions by the hero/ine to get what s/he wants have not cut it, so the actions become bigger and usually more desperate.

Do we see a new level of commitment in the hero/ine?

How are the hero/ine’s actions becoming more desperate?

* It’s also worth noting that while the hero/ine is generally (but not always!) winning in Act II:1, s/he generally begins to lose in Act II:2. Often this is where everything starts to unravel and spiral out of control.

* INCREASED ATTACKS BY ANTAGONIST

Just as the hero/ine is becoming more desperate to get what s/he wants, the antagonist also has failed to get what s/he wants and becomes more desperate and takes riskier actions.

* HARD CHOICES AND CROSSING THE LINE (IMMORAL ACTIONS by the main character to get what s/he wants)

Do we see the hero/ine crossing the line and doing immoral things to get what s/he wants?

* LOSS OF KEY ALLIES (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

Do any allies walk out on the hero/ine or get killed or injured?

* A TICKING CLOCK (can happen anywhere in the story, or there may not be one.)

* REVERSALS AND REVELATIONS/TWISTS

* THE LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL and/or VISIT TO DEATH (also known as: ALL IS LOST).

There is always a moment in a story where the hero/ine seems to have lost everything, and it is almost always right before the Second Act Climax, or it IS the Second Act Climax.

What is the All Is Lost scene?

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a THE LOVER MAKES A STAND scene, where s/he tells the loved one – “Enough of this bullshit waffling, either commit to me or don’t, but if you don’t, I’m out of here.” This can be the hero/ine or the love interest making this stand.

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often will be a final revelation before the end game: often the knowledge of who the opponent really is, that will propel the hero/ine into the FINAL BATTLE.

* Often will be another devastating loss, the ALL IS LOST scene. In a mythic structure or Chosen One story or mentor story this is almost ALWAYS where the mentor dies or is otherwise taken out of the action, so the hero/ine must go into the final battle alone.

* Answers the Central Question – and often the answer is “no” – so that the hero/ine again must come up with a whole new plan.

* Often is a SETPIECE.

More discussion on Elements Of Act II:2

And here are the elements and questions for Act Three:

ACT THREE

The third act is basically the Final Battle and Resolution. It can often be one continuous sequence – the chase and confrontation, or confrontation and chase. There may be a final preparation for battle, or it might be done on the fly. Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelations of the second act.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It is often divided into two sequences:

1. Getting there (Storming the Castle) (Sequence 7).

2. The final battle itself (Sequence 8)

* In addition to the FINAL PLAN, there may be another GATHERING OF THE TEAM, and a brief TRANING SEQUENCE.

• There may well be DEFEATS OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS (each one of which should be given a satisfying end or comeuppance. (This may also happen earlier, in Act II:2).

* Thematic Location - often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare

-

* The protagonist’s character change

-

* The antagonist’s character change (if any)

* Possibly ally/allies’ character change (s) and/or gaining of desire (s)

* Possibly a huge final reversal or reveal (twist), or even a whole series of payoffs that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Future and It’s A Wonderful Life)

* RESOLUTION: A glimpse into the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it.

• Possibly a sense of coming FULL CIRCLE – returning to the opening image or scene and showing how much things have changed, or how the hero/ine has changed inside, causing her or him to deal with the same place and situation in a whole different way.

* Closing Image

More on Act Three:

Elements of Act Three

What Makes a Great Climax?

Elevate Your Ending

Now, I'd also like to remind everyone that this is a basic, GENERAL list. There are story elements specific to whatever kind of story you're writing, and the best way to get familiar with what those are is to do (or take a look at story breakdowns on three (at least) movies or books that are similar to the KIND of story you're writing.

What KIND Of Story Is It?

I hope that there's something there to get you through that third quarter, but I'll post a few more brainstorming tricks this week.

In the meantime, good luck with the family! I mean, Happy Thanksgiving!

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Published on November 23, 2013 07:31

November 18, 2013

Nanowrimo: The MIDPOINT

Okay, it's a little past the midpoint of the month, so some, not all, of you will be coming up on the midpoint of your books. I am as ever skeptical that you can really get to the midpoint of a book in two weeks... but it's still a good reason to talk about one of the most important elements of any book, film, TV show, or play.

THE MIDPOINT

All of the first half of the second act – that’s p. 30-60 in a script, p. 100 to p. 200 in a 400-page book, is leading up to the MIDPOINT. So the Midpoint occurs at about one hour into a movie, and at about page 200 in a book.

The Midpoint is also often called the MOMENT OF COMMITMENT or the POINT OF NO RETURN or NO TURNING BACK: the hero/ine commits irrevocably to the action.

The Midpoint is one of the most important scenes or sequences in any book or film: a major shift in the dynamics of the story. Something huge will be revealed; something goes disastrously wrong; someone close to the hero/ine dies, intensifying her or his commitment (What I call the “Now it’s personal” scene… imagine Clint Eastwood or Bruce Willis growling the line). Often the whole emotional dynamic between characters changes with what Hollywood calls, “Sex at Sixty” (that’s 60 minutes, not sixty years!).

Often a TICKING CLOCK is introduced at the Midpoint, as we will discuss further in the chapter on Creating Suspense (Chapter 31). A clock is a great way to speed up the action and increase the urgency of your story.

The Midpoint can also be a huge defeat, which requires a recalculation and NEW PLAN of attack. It’s a game-changer, and it locks the hero/ine even more inevitably into the story.

Let's look at some examples.

As I've said before, a favorite PLAN and CENTRAL STORY ACTION of mine is in Brian DePalma’s The Untouchables.

Young FBI agent Eliot Ness is assigned to bring down mobster Al Capone. So far no one in law enforcement or government has been able to pin Capone to any of his heinous crimes; he keeps too much distance between himself and the actual killings, hijackings, extortions, etc. One of Ness’ Untouchable team, a FBI accountant, proposes that the team gather evidence and nail Capone on federal tax evasion. It’s not sexy, but the penalty is up to 25 years in prison. (As you might know, this PLAN is historically accurate: Al Capone was actually finally charged and imprisoned on the charge of tax evasion.)

So the PLAN and CENTRAL ACTION of the story becomes to locate one of Capone’s bookkeepers, take him into custody and force him to testify against Capone. Which they do. (With plenty of action sequences, of course.)

So as we approach the MIDPOINT, Ness’s team has the bookkeeper in custody, the trial is set, and Ness’s men are escorting the bookkeeper to court.

But the movie is only half over. So of course, as very often happens at the midpoint, the plan fails. In a suspenseful and emotional wrenching MIDPOINT CLIMAX, Ness’s accountant teammate, whom we have come to love, escorts the bookkeeper into the courthouse elevator to take him up to the courtroom. As the doors close, we see the police guard is actually one of Capone’s men.

Ness and his other teammate (a criminally hot Andy Garcia), realize that something’s wrong and race up (down?) the stairs to catch the elevator, but arrive to find a bloodbath – both accountants brutally murdered, and the word TOUCHABLE painted on the elevator in blood.

So the plan is totally foiled – they have no witness and no more case. It’s a great midpoint reversal, because we – and Ness himself – have no idea what the team is going to be able to do next (and also Ness is so emotionally devastated by the loss of his teammate that he begins to do reckless things.).

Not only does the murder of the two accountants (Capone's and Ness's) completely annihilate Ness's PLAN), but the murder of Ness's teammate makes the stakes deeply personal.

But a Midpoint doesn’t have to be a huge action scene. Another interesting and tonally very different Midpoint happens in Raiders of the Lost Ark. I’m sure some people would dispute me on this one (and people argue about the exact midpoint of movies all the time), but I would say the Midpoint is the scene that occurs exactly 60 minutes into the film, in which, having determined that the Nazis are digging in the wrong place in the archeological site, Indy goes down into that chamber with the pendant and a staff of the proper height, and uses the crystal in the pendant to pinpoint the exact location of the Ark.

This scene is quiet, and involves only one person, but it’s mystically powerful – note the use of light and the religious quality of the music… and Indy is decked out in robes almost like, well, Moses. Staff and all. Indy stands like God over the miniature of the temple city, and the beam of light comes through the crystal like light from heaven. It’s all a foreshadowing of the final climax, in which God intervenes in much the same way. Very effective, with lots of subliminal manipulation going on. And of course, at the end of the scene, Indy has the information he needs to retrieve the Ark. I would also point out that the Midpoint is often some kind of mirror image of the final climax; it’s an interesting device to use, and you may find yourself using it without even being aware of it.

(I will concede that in Raiders, you could call the Midpoint a two-parter: Indy’s discovery that Marion is still alive is a big twist. But personally I think that scene is part of the next sequence).

Another very different kind of midpoint occurs in Silence of the Lambs: the “Quid Pro Quo” scene between Clarice and Lecter, in which she bargains personal information to get Lecter’s insights into the case. Clarice is on a time clock, here, because Catherine Martin has been kidnapped and Clarice knows they have only three days before Buffalo Bill kills her. Clarice goes in at first to offer Lecter what she knows he desires most (because he has STATED his desire, clearly and early on) – a transfer to a Federal prison, away from Dr. Chilton and with a view. Clarice has a file with that offer from Senator Martin – she says – but in reality the offer is a total fake. We don’t know this at the time, but it has been cleverly PLANTED that it’s impossible to fool Lecter (Crawford sends Clarice in to the first interview without telling her what the real purpose is so that Lecter won’t be able to read her). But Clarice has learned and grown enough to fool Lecter – and there’s a great payoff when Lecter later acknowledges that fact.

The deal is not enough for Lecter, though – he demands that Clarice do exactly what her boss, Crawford, has warned her never to do: he wants her to swap personal information for clues – a classic deal with the devil game.

After Clarice confesses painful secrets, Lecter gives her the clue she’s been digging for – to search for Buffalo Bill through the sex reassignment clinics. And as is so often the case, there is a second climax within the midpoint – the film cuts to the killer in his basement, standing over the pit making a terrified Catherine put lotion on her skin – it’s a horrifying curtain and drives home the stakes. (Each climax in SOTL is a one-two punch - screen the movie again and see what I mean!).

I recently reread Harlan Coben's The Woods, which employs a great technique to craft an explosive Midpoint: the book has an A story and a B story (well, really, with Coben it's always about sixteen different threads of each plot intricately interwoven, but two main plots). In the B story, the protagonist is prosecuting two frat boys who raped a stripper at a frat party, and at the Midpoint is the main courtroom confrontation of that plot. The storyline continues, but now it becomes subordinate (and of course interconnected to) to the building A plot. This very emotional climaxing of the B plot at the midpoint is a terrifically effective structure technique that is great to have in your story structure toolbox.

In Sense and Sensibility, the Midpoint is the emotionally wrenching scene in which Lucy Steele reveals to Elinor that she has been secretly engaged to Edward Ferrars for five years. We are so committed to Edward and Elinor’s love that we are as devastated as Elinor is, and just as shocked that Edward would have lied to her. The Midpoint is even more wrenching because Elinor’s sister Marianne has also just been abandoned by her love interest. It’s a double-punch to the gut.

In Notting Hill, Julia Roberts has asked Hugh Grant up to her hotel suite for the first time, and Hugh walks in to find that Julia’s movie star boyfriend, Alec Baldwin, whom Hugh knew nothing about, is already there with her. We know that Hugh’s GHOST is that his ex-wife left him for a man who looked just like Harrison Ford (Alec is pretty close!), and to add to this blow, Alec mistakes Hugh for a room-service waiter and tips him, asking him to clean up while he takes Julia into the bedroom. Total emotional annihilation.

In a romance, the Midpoint is very often sexual or emotional. But the Midpoint can often be one of the most memorable visual SETPIECES of the story, just to further drive its importance home.

Note that the Midpoint is not necessarily just one scene; it can be a double punch as I just pointed out about Sense And Sensibility, and it can also be a progression of scenes and revelations that include a climactic scene, a complete change of location, a major revelation, a major reversal, a cliffhanger – all or any combination of the above.

One of the great Midpoints in theater and film is in My Fair Lady. Talk about a double punch! There is not one iconic song at the Midpoint curtain, but two: first “The Rain In Spain”, in which Eliza finally starts to speak with perfect diction, and Professor Higgins, the Colonel, and Eliza celebrate with wild and joyous dancing: a moment of triumph. Then when the housekeeper takes Eliza upstairs to bed, Higgins privately tells the Colonel that she’s ready: they can test her out in public. He intends to take her to an Embassy ball and pass her off as a lady to win his bet with the Colonel, which Eliza knows nothing about. Meanwhile upstairs, giddy with happiness, Eliza sings “I Could Have Danced All Night”, and we realize she has fallen in love with the Professor.

Not just two of the greatest songs of the musical theater in a row, but all of this SETUP, big HOPE, FEAR, and STAKES. Eliza is in love with Higgins and he’s just using her for a bet. There’s a huge TEST coming up at this ball, and we saw excitable Eliza fail miserably in her first public test at the Ascot races. There’s a penalty of prison for impersonating a lady, so there are not just the emotional stakes of a possible broken heart, but possible prison time.

Do you think anyone was not going to come back into the theater to see what happens at that ball?

Asking a big question like that is a great technique to use at the Midpoint.

A totally different, but equally famous example: in Jaws, the Midpoint climax is actually a whole sequence long: a highly suspenseful setpiece in which the city officials have refused to shut down the beaches, so Sheriff Brody is out there on the beach keeping watch (as if that’s going to prevent a shark attack!), the Coast Guard is patrolling the ocean – and, almost as if it’s aware of the whole plan, the shark swims into an unguarded harbor, where it attacks and swallows a man and for a horrifying moment we think that it has also killed Brody’s son (really it’s only frightened him into near-paralysis). It’s a huge climax and adrenaline rush, but it’s not over yet. Because now the Mayor writes the check to hire Quint to hunt down the shark, and since Brody’s family has been threatened (“Now it’s PERSONAL”), Brody decides to go out with Quint and Hooper on the boat – and there’s also a huge change in location as we see that little boat headed out to the open sea.

It really pays to start taking note of the Midpoints of films and books. If you find that your story is sagging in the middle, the first thing you should look at is your Midpoint scene.

I know this and I still sometimes forget it. When I turned in my poltergeist novel The Unseen, I knew that I was missing something in the middle, even though there was a very clear change in location and focus at the Midpoint: it’s the point at which my characters actually move into the supposedly haunted house and begin their experiment.

But there was still something missing in the scene right before, the close of the first half, and my editor had the same feeling, without really knowing what was needed, although it had something to do with the motivation of the heroine – the reason she would put herself in that kind of danger. So I looked at the scene before the characters moved in to the house, and lo and behold: what I was missing was “Sex at Sixty.” It’s my heroine’s desire for one of the other characters that makes her commit to the investigation, and I wasn’t making that desire line clear enough.

The Midpoint often LOCKS THE HERO/INE INTO A COURSE OF ACTION, or sometimes, physically locks the hero/ine into a location.

A great recent example is Inception: at the Midpoint, there’s a big action sequence, ending in a gun battle in which one of the allies, Saito (who hired the team to break into this dream) is badly wounded, and the team discovers that they can’t get out of the dream while Saito is unconscious. They’re stuck, perhaps forever, which forces them to devise a new PLAN.

There’s a not-so recent movie called Ghost Ship, about a salvage crew investigating a derelict ocean liner which has mysteriously appeared out in the middle of the Bering Straight, after being lost without a trace for forty years. At the Midpoint, the salvage crew’s own boat mysteriously catches on fire and sinks (taking one of the crew with it), forcing the entire crew to board the haunted ocean liner. They are physically locked into the situation, now, and their original PLAN – to tow the ocean liner back to shore – must change; they now have to repair the ocean liner and sail her out of the Strait. This development also solves the perennial problem of haunted house – or haunted ship – stories: “Why don’t the characters just leave?”

It’s a great Midpoint scene for all of the above reasons, plus it’s a great visual and action setpiece: the explosion of the salvage boat, the rescue (and loss) of crew members, and the suspense of who will get out of the water and on to the ocean liner alive.

So as you're writing your fingers off, try taking a minute to contemplate what your Midpoint is, and how it changes the action of your book. If you can devise a great setpiece for your midpoint and also somehow destroy your hero'ine's initial plan, you won't have to worry about a sagging middle section, because you and your hero/ine will suddenly be scrambling to figure out a brand new and exiting plan of action to get their desire.

It really is the KEY to Act II.

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

THE MIDPOINT

All of the first half of the second act – that’s p. 30-60 in a script, p. 100 to p. 200 in a 400-page book, is leading up to the MIDPOINT. So the Midpoint occurs at about one hour into a movie, and at about page 200 in a book.

The Midpoint is also often called the MOMENT OF COMMITMENT or the POINT OF NO RETURN or NO TURNING BACK: the hero/ine commits irrevocably to the action.

The Midpoint is one of the most important scenes or sequences in any book or film: a major shift in the dynamics of the story. Something huge will be revealed; something goes disastrously wrong; someone close to the hero/ine dies, intensifying her or his commitment (What I call the “Now it’s personal” scene… imagine Clint Eastwood or Bruce Willis growling the line). Often the whole emotional dynamic between characters changes with what Hollywood calls, “Sex at Sixty” (that’s 60 minutes, not sixty years!).

Often a TICKING CLOCK is introduced at the Midpoint, as we will discuss further in the chapter on Creating Suspense (Chapter 31). A clock is a great way to speed up the action and increase the urgency of your story.

The Midpoint can also be a huge defeat, which requires a recalculation and NEW PLAN of attack. It’s a game-changer, and it locks the hero/ine even more inevitably into the story.

Let's look at some examples.

As I've said before, a favorite PLAN and CENTRAL STORY ACTION of mine is in Brian DePalma’s The Untouchables.

Young FBI agent Eliot Ness is assigned to bring down mobster Al Capone. So far no one in law enforcement or government has been able to pin Capone to any of his heinous crimes; he keeps too much distance between himself and the actual killings, hijackings, extortions, etc. One of Ness’ Untouchable team, a FBI accountant, proposes that the team gather evidence and nail Capone on federal tax evasion. It’s not sexy, but the penalty is up to 25 years in prison. (As you might know, this PLAN is historically accurate: Al Capone was actually finally charged and imprisoned on the charge of tax evasion.)

So the PLAN and CENTRAL ACTION of the story becomes to locate one of Capone’s bookkeepers, take him into custody and force him to testify against Capone. Which they do. (With plenty of action sequences, of course.)

So as we approach the MIDPOINT, Ness’s team has the bookkeeper in custody, the trial is set, and Ness’s men are escorting the bookkeeper to court.

But the movie is only half over. So of course, as very often happens at the midpoint, the plan fails. In a suspenseful and emotional wrenching MIDPOINT CLIMAX, Ness’s accountant teammate, whom we have come to love, escorts the bookkeeper into the courthouse elevator to take him up to the courtroom. As the doors close, we see the police guard is actually one of Capone’s men.

Ness and his other teammate (a criminally hot Andy Garcia), realize that something’s wrong and race up (down?) the stairs to catch the elevator, but arrive to find a bloodbath – both accountants brutally murdered, and the word TOUCHABLE painted on the elevator in blood.

So the plan is totally foiled – they have no witness and no more case. It’s a great midpoint reversal, because we – and Ness himself – have no idea what the team is going to be able to do next (and also Ness is so emotionally devastated by the loss of his teammate that he begins to do reckless things.).

Not only does the murder of the two accountants (Capone's and Ness's) completely annihilate Ness's PLAN), but the murder of Ness's teammate makes the stakes deeply personal.

But a Midpoint doesn’t have to be a huge action scene. Another interesting and tonally very different Midpoint happens in Raiders of the Lost Ark. I’m sure some people would dispute me on this one (and people argue about the exact midpoint of movies all the time), but I would say the Midpoint is the scene that occurs exactly 60 minutes into the film, in which, having determined that the Nazis are digging in the wrong place in the archeological site, Indy goes down into that chamber with the pendant and a staff of the proper height, and uses the crystal in the pendant to pinpoint the exact location of the Ark.

This scene is quiet, and involves only one person, but it’s mystically powerful – note the use of light and the religious quality of the music… and Indy is decked out in robes almost like, well, Moses. Staff and all. Indy stands like God over the miniature of the temple city, and the beam of light comes through the crystal like light from heaven. It’s all a foreshadowing of the final climax, in which God intervenes in much the same way. Very effective, with lots of subliminal manipulation going on. And of course, at the end of the scene, Indy has the information he needs to retrieve the Ark. I would also point out that the Midpoint is often some kind of mirror image of the final climax; it’s an interesting device to use, and you may find yourself using it without even being aware of it.

(I will concede that in Raiders, you could call the Midpoint a two-parter: Indy’s discovery that Marion is still alive is a big twist. But personally I think that scene is part of the next sequence).

Another very different kind of midpoint occurs in Silence of the Lambs: the “Quid Pro Quo” scene between Clarice and Lecter, in which she bargains personal information to get Lecter’s insights into the case. Clarice is on a time clock, here, because Catherine Martin has been kidnapped and Clarice knows they have only three days before Buffalo Bill kills her. Clarice goes in at first to offer Lecter what she knows he desires most (because he has STATED his desire, clearly and early on) – a transfer to a Federal prison, away from Dr. Chilton and with a view. Clarice has a file with that offer from Senator Martin – she says – but in reality the offer is a total fake. We don’t know this at the time, but it has been cleverly PLANTED that it’s impossible to fool Lecter (Crawford sends Clarice in to the first interview without telling her what the real purpose is so that Lecter won’t be able to read her). But Clarice has learned and grown enough to fool Lecter – and there’s a great payoff when Lecter later acknowledges that fact.

The deal is not enough for Lecter, though – he demands that Clarice do exactly what her boss, Crawford, has warned her never to do: he wants her to swap personal information for clues – a classic deal with the devil game.

After Clarice confesses painful secrets, Lecter gives her the clue she’s been digging for – to search for Buffalo Bill through the sex reassignment clinics. And as is so often the case, there is a second climax within the midpoint – the film cuts to the killer in his basement, standing over the pit making a terrified Catherine put lotion on her skin – it’s a horrifying curtain and drives home the stakes. (Each climax in SOTL is a one-two punch - screen the movie again and see what I mean!).

I recently reread Harlan Coben's The Woods, which employs a great technique to craft an explosive Midpoint: the book has an A story and a B story (well, really, with Coben it's always about sixteen different threads of each plot intricately interwoven, but two main plots). In the B story, the protagonist is prosecuting two frat boys who raped a stripper at a frat party, and at the Midpoint is the main courtroom confrontation of that plot. The storyline continues, but now it becomes subordinate (and of course interconnected to) to the building A plot. This very emotional climaxing of the B plot at the midpoint is a terrifically effective structure technique that is great to have in your story structure toolbox.

In Sense and Sensibility, the Midpoint is the emotionally wrenching scene in which Lucy Steele reveals to Elinor that she has been secretly engaged to Edward Ferrars for five years. We are so committed to Edward and Elinor’s love that we are as devastated as Elinor is, and just as shocked that Edward would have lied to her. The Midpoint is even more wrenching because Elinor’s sister Marianne has also just been abandoned by her love interest. It’s a double-punch to the gut.

In Notting Hill, Julia Roberts has asked Hugh Grant up to her hotel suite for the first time, and Hugh walks in to find that Julia’s movie star boyfriend, Alec Baldwin, whom Hugh knew nothing about, is already there with her. We know that Hugh’s GHOST is that his ex-wife left him for a man who looked just like Harrison Ford (Alec is pretty close!), and to add to this blow, Alec mistakes Hugh for a room-service waiter and tips him, asking him to clean up while he takes Julia into the bedroom. Total emotional annihilation.

In a romance, the Midpoint is very often sexual or emotional. But the Midpoint can often be one of the most memorable visual SETPIECES of the story, just to further drive its importance home.

Note that the Midpoint is not necessarily just one scene; it can be a double punch as I just pointed out about Sense And Sensibility, and it can also be a progression of scenes and revelations that include a climactic scene, a complete change of location, a major revelation, a major reversal, a cliffhanger – all or any combination of the above.

One of the great Midpoints in theater and film is in My Fair Lady. Talk about a double punch! There is not one iconic song at the Midpoint curtain, but two: first “The Rain In Spain”, in which Eliza finally starts to speak with perfect diction, and Professor Higgins, the Colonel, and Eliza celebrate with wild and joyous dancing: a moment of triumph. Then when the housekeeper takes Eliza upstairs to bed, Higgins privately tells the Colonel that she’s ready: they can test her out in public. He intends to take her to an Embassy ball and pass her off as a lady to win his bet with the Colonel, which Eliza knows nothing about. Meanwhile upstairs, giddy with happiness, Eliza sings “I Could Have Danced All Night”, and we realize she has fallen in love with the Professor.

Not just two of the greatest songs of the musical theater in a row, but all of this SETUP, big HOPE, FEAR, and STAKES. Eliza is in love with Higgins and he’s just using her for a bet. There’s a huge TEST coming up at this ball, and we saw excitable Eliza fail miserably in her first public test at the Ascot races. There’s a penalty of prison for impersonating a lady, so there are not just the emotional stakes of a possible broken heart, but possible prison time.

Do you think anyone was not going to come back into the theater to see what happens at that ball?

Asking a big question like that is a great technique to use at the Midpoint.

A totally different, but equally famous example: in Jaws, the Midpoint climax is actually a whole sequence long: a highly suspenseful setpiece in which the city officials have refused to shut down the beaches, so Sheriff Brody is out there on the beach keeping watch (as if that’s going to prevent a shark attack!), the Coast Guard is patrolling the ocean – and, almost as if it’s aware of the whole plan, the shark swims into an unguarded harbor, where it attacks and swallows a man and for a horrifying moment we think that it has also killed Brody’s son (really it’s only frightened him into near-paralysis). It’s a huge climax and adrenaline rush, but it’s not over yet. Because now the Mayor writes the check to hire Quint to hunt down the shark, and since Brody’s family has been threatened (“Now it’s PERSONAL”), Brody decides to go out with Quint and Hooper on the boat – and there’s also a huge change in location as we see that little boat headed out to the open sea.

It really pays to start taking note of the Midpoints of films and books. If you find that your story is sagging in the middle, the first thing you should look at is your Midpoint scene.

I know this and I still sometimes forget it. When I turned in my poltergeist novel The Unseen, I knew that I was missing something in the middle, even though there was a very clear change in location and focus at the Midpoint: it’s the point at which my characters actually move into the supposedly haunted house and begin their experiment.

But there was still something missing in the scene right before, the close of the first half, and my editor had the same feeling, without really knowing what was needed, although it had something to do with the motivation of the heroine – the reason she would put herself in that kind of danger. So I looked at the scene before the characters moved in to the house, and lo and behold: what I was missing was “Sex at Sixty.” It’s my heroine’s desire for one of the other characters that makes her commit to the investigation, and I wasn’t making that desire line clear enough.

The Midpoint often LOCKS THE HERO/INE INTO A COURSE OF ACTION, or sometimes, physically locks the hero/ine into a location.

A great recent example is Inception: at the Midpoint, there’s a big action sequence, ending in a gun battle in which one of the allies, Saito (who hired the team to break into this dream) is badly wounded, and the team discovers that they can’t get out of the dream while Saito is unconscious. They’re stuck, perhaps forever, which forces them to devise a new PLAN.

There’s a not-so recent movie called Ghost Ship, about a salvage crew investigating a derelict ocean liner which has mysteriously appeared out in the middle of the Bering Straight, after being lost without a trace for forty years. At the Midpoint, the salvage crew’s own boat mysteriously catches on fire and sinks (taking one of the crew with it), forcing the entire crew to board the haunted ocean liner. They are physically locked into the situation, now, and their original PLAN – to tow the ocean liner back to shore – must change; they now have to repair the ocean liner and sail her out of the Strait. This development also solves the perennial problem of haunted house – or haunted ship – stories: “Why don’t the characters just leave?”

It’s a great Midpoint scene for all of the above reasons, plus it’s a great visual and action setpiece: the explosion of the salvage boat, the rescue (and loss) of crew members, and the suspense of who will get out of the water and on to the ocean liner alive.

So as you're writing your fingers off, try taking a minute to contemplate what your Midpoint is, and how it changes the action of your book. If you can devise a great setpiece for your midpoint and also somehow destroy your hero'ine's initial plan, you won't have to worry about a sagging middle section, because you and your hero/ine will suddenly be scrambling to figure out a brand new and exiting plan of action to get their desire.

It really is the KEY to Act II.

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Published on November 18, 2013 19:32

November 12, 2013

Nanowrimo: The PLAN (Act II)

So now we're over a third of the way into the month, and if you've been doing Nano diligently you may be up to 20,000 words. Amazing, but some people really do get that far this month.

Depending on how thorough you're being with all this writing, then, you've probably written the first act and are moving into the second. Or if you're taking this "write a book in a month" thing literally, then you're closer to the midpoint. Of a very short book.

Either way, you are currently faced with or already struggling with the dreaded second act. Although anyone who has the workbooks and/or reads this blog regularly shouldn't fear the second act any more, right?

But today I wanted to review what I think it the key to any second act, and really the whole key to story structure: The PLAN.

You always hear that “Drama is conflict,” but when you think about it –what the hell does that mean, practically?

It’s actually much more true, and specific, to say that drama is the constant clashing of a hero/ine’s PLAN and an antagonist’s, or several antagonists’, PLANS.

In the first act of a story, the hero/ine is introduced, and that hero/ine either has or quickly develops a DESIRE. She might have a PROBLEM that needs to be solved, or someone or something she WANTS, or a bad situation that she needs to get out of, pronto.

Her reaction to that problem or situation is to formulate a PLAN, even if that plan is vague or even completely subconscious. But somewhere in there, there is a plan, and storytelling is usually easier if you have the hero/ine or someone else (maybe you, the author) state that plan clearly, so the audience or reader knows exactly what the expectation is.

And the protagonist’s plan (and the corresponding plan of the antagonist’s) actually drives the entire action of the second act. Stating the plan tells us what the CENTRAL ACTION of the story will be. So it’s critical to set up the plan by the end of Act One, or at the very beginning of Act Two, at the latest.

Let’s look at some examples of how plans work.

I always like to start, improbably, with the actioner 2012, even though I thought it was a pretty terrible movie overall.