Alexandra Sokoloff's Blog, page 26

October 16, 2013

Nanowrimo Prep: Story Elements Checklist

As any of you who are brainstorming Index Cards

right now have found, this is not an orderly process. You will be

coming up with scenes in no order whatsoever, all over the structure

grid. Some that you will have no idea where to put. And so while this week I

will be working ahead through story structure in a relative order, I

want to re-post the whole general Story Elements Checklist, so you have a

whole overview of scenes and story elements you will be needing beyond

whatever act we happen to be talking about at the time.

When

you start out brainstorming index cards, you can make cards for all of

the elements below, even if you have no idea what those scenes might

look like, because with only one or two exceptions (which I've noted

below), these are scenes and elements that are going to appear in your

story no matter what genre you're writing in.

Even

better - they're almost certainly going to appear in the Act in which

I've listed them below. There are exceptions, of course, but those are

rare. When you start looking at

stories for where these elements turn up, and noticing how prevalent

the patterns are, it will make plotting out any story so much easier you

won't even believe it. And I'm a big believer that just asking the

question will get your subconscious working on the perfect answer.

Write out the card in the most general sense today, and you may well

wake up with the perfect scene tomorrow morning.

STORY ELEMENTS CHECKLIST FOR GENERATING INDEX CARDS

ACT ONE

* Opening image

* Meet the hero or heroine in the ordinary world

* Hero/ine’s inner and outer desire.

* Hero/ine's ghost or wound

* Hero/ine’s arc -

* Inciting Incident/Call to Adventure

*

Meet the antagonist (and/or introduce a mystery, which is what you do

when you’re going to keep your antagonist hidden to reveal at the end)

* State the theme/what’s the story about?

* Allies

* Mentor (possibly. You may not have one or s/he may be revealed later in the story).

* Love interest (probably)

* Plant/Reveal (or: Set ups and Payoffs)

* Hope/Fear (and Stakes)

* Time Clock (possibly. May not have one or may be revealed later in the story)

* Sequence One climax

* Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

* Act One climax

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ACT TWO, PART ONE

* Crossing the Threshold/ Into the Special World (may occur in Act One)

* Threshold Guardian/Guardian at the Gate (possibly)

* Hero/ine’s Plan

* Antagonist’s Plan

* Training Sequence (possibly)

* Series of Tests

-

* Picking up new Allies

* Assembling the Team (possibly)

* Attacks by the Antagonist (whether or not the Hero/ine recognizes these as coming from the antagonist)

* In a detective story, Questioning Witnesses, Lining Up and Eliminating Suspects, Following Clues.

*Bonding with Allies

THE MIDPOINT

* Completely changes the game

* Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

* Can be a huge revelation

* Can be a huge defeat

* Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

* Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ACT TWO, PART TWO

*

Recalibrating – after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the

midpoint, the hero/ine must Revamp The Plan and try a New Mode of

Attack.

* Escalating Actions/ Obsessive Drive

* Hard Choices and Crossing The Line (immoral actions by the main character to get what s/he wants)

* Loss of Key Allies (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

* A Ticking Clock (can happen anywhere in the story)

* Reversals and Revelations/Twists.

* The Long Dark Night of the Soul and/or Visit to Death (also known as: All Is Lost)

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a The Lover Makes A Stand scene

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often can be a final revelation before the end game: the knowledge of who the opponent really is

* Answers the Central Question

------------------------------------------------------------------------

ACT THREE

The

third act is basically the Final Battle and Resolution. It can often

be one continuous sequence – the chase and confrontation, or

confrontation and chase. There may be a final preparation for battle,

or it might be done on the fly. Either here or in the last part of

the second act the hero will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new

information and revelations of the second act.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It is often divided into two sequences:

1. Getting there (Storming the Castle)

2. The final battle itself

* Thematic Location - often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare

* The protagonist’s character change

* The antagonist’s character change (if any)

* Possibly ally/allies’ character changes and/or gaining of desire

*

Possibly a huge final reversal or reveal (twist), or even a whole

series of payoffs that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Future and

It’s A Wonderful Life)

* RESOLUTION: A glimpse into

the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole

ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it.

* Closing Image

Now,

I'd also like to remind everyone that this is a basic, GENERAL list.

There are story elements specific to whatever kind of story you're

writing, and the best way to get familiar with what those are is to do

the story breakdowns on three (at least) movies or books that are

similar to the KIND of story you're writing.

I

strongly recommend that you watch at least one, or much better, three of

the films I break down in the workbooks, following along with my notes.

I do full breakdowns of Chinatown, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, Romancing the Stone, and The Mist, and act breakdowns of You've Got Mail, Jaws, Silence of the Lambs, Raiders of the Lost Ark in Screenwriting Tricks For Authors.

I do full breakdowns of The

Proposal, Groundhog Day, Sense and Sensibility, Romancing the Stone,

Leap Year, Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Sea of Love, While

You Were Sleeping and New in Town in Writing Love.

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Alex

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

=====================================================

HALLOWEEN GIVEAWAY

It's

October, my favorite month, and you-know-what is coming, so I'm giving

away 15 signed hardcover copies of my spooky thriller Book of Shadows . To enter, just sign up for my mailing list at http://alexandrasokoloff.com (the box on the left of the screen.)

Book of Shadows .

An

ambitious Boston homicide detective must join forces with a beautiful,

mysterious witch from Salem in a race to solve a series of satanic

killings.

Amazon Bestseller in Horror and Police Procedurals

"A wonderfully dark thriller with amazing 'Is-it-isn't-it?' suspense all the way to the end. Highly recommended."

- Lee Child

right now have found, this is not an orderly process. You will be

coming up with scenes in no order whatsoever, all over the structure

grid. Some that you will have no idea where to put. And so while this week I

will be working ahead through story structure in a relative order, I

want to re-post the whole general Story Elements Checklist, so you have a

whole overview of scenes and story elements you will be needing beyond

whatever act we happen to be talking about at the time.

When

you start out brainstorming index cards, you can make cards for all of

the elements below, even if you have no idea what those scenes might

look like, because with only one or two exceptions (which I've noted

below), these are scenes and elements that are going to appear in your

story no matter what genre you're writing in.

Even

better - they're almost certainly going to appear in the Act in which

I've listed them below. There are exceptions, of course, but those are

rare. When you start looking at

stories for where these elements turn up, and noticing how prevalent

the patterns are, it will make plotting out any story so much easier you

won't even believe it. And I'm a big believer that just asking the

question will get your subconscious working on the perfect answer.

Write out the card in the most general sense today, and you may well

wake up with the perfect scene tomorrow morning.

STORY ELEMENTS CHECKLIST FOR GENERATING INDEX CARDS

ACT ONE

* Opening image

* Meet the hero or heroine in the ordinary world

* Hero/ine’s inner and outer desire.

* Hero/ine's ghost or wound

* Hero/ine’s arc -

* Inciting Incident/Call to Adventure

*

Meet the antagonist (and/or introduce a mystery, which is what you do

when you’re going to keep your antagonist hidden to reveal at the end)

* State the theme/what’s the story about?

* Allies

* Mentor (possibly. You may not have one or s/he may be revealed later in the story).

* Love interest (probably)

* Plant/Reveal (or: Set ups and Payoffs)

* Hope/Fear (and Stakes)

* Time Clock (possibly. May not have one or may be revealed later in the story)

* Sequence One climax

* Plan, Central Question, Central Story Action

* Act One climax

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ACT TWO, PART ONE

* Crossing the Threshold/ Into the Special World (may occur in Act One)

* Threshold Guardian/Guardian at the Gate (possibly)

* Hero/ine’s Plan

* Antagonist’s Plan

* Training Sequence (possibly)

* Series of Tests

-

* Picking up new Allies

* Assembling the Team (possibly)

* Attacks by the Antagonist (whether or not the Hero/ine recognizes these as coming from the antagonist)

* In a detective story, Questioning Witnesses, Lining Up and Eliminating Suspects, Following Clues.

*Bonding with Allies

THE MIDPOINT

* Completely changes the game

* Locks the hero/ine into a situation or action

* Can be a huge revelation

* Can be a huge defeat

* Can be a “now it’s personal” loss

* Can be sex at 60 – the lovers finally get together, only to open up a whole new world of problems

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ACT TWO, PART TWO

*

Recalibrating – after the shock or defeat of the game-changer in the

midpoint, the hero/ine must Revamp The Plan and try a New Mode of

Attack.

* Escalating Actions/ Obsessive Drive

* Hard Choices and Crossing The Line (immoral actions by the main character to get what s/he wants)

* Loss of Key Allies (possibly because of the hero/ine’s obsessive actions, possibly through death or injury by the antagonist).

* A Ticking Clock (can happen anywhere in the story)

* Reversals and Revelations/Twists.

* The Long Dark Night of the Soul and/or Visit to Death (also known as: All Is Lost)

* In a romance or romantic comedy, the All Is Lost moment is often a The Lover Makes A Stand scene

THE SECOND ACT CLIMAX

* Often can be a final revelation before the end game: the knowledge of who the opponent really is

* Answers the Central Question

------------------------------------------------------------------------

ACT THREE

The

third act is basically the Final Battle and Resolution. It can often

be one continuous sequence – the chase and confrontation, or

confrontation and chase. There may be a final preparation for battle,

or it might be done on the fly. Either here or in the last part of

the second act the hero will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new

information and revelations of the second act.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It is often divided into two sequences:

1. Getting there (Storming the Castle)

2. The final battle itself

* Thematic Location - often a visual and literal representation of the Hero/ine’s Greatest Nightmare

* The protagonist’s character change

* The antagonist’s character change (if any)

* Possibly ally/allies’ character changes and/or gaining of desire

*

Possibly a huge final reversal or reveal (twist), or even a whole

series of payoffs that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Future and

It’s A Wonderful Life)

* RESOLUTION: A glimpse into

the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole

ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it.

* Closing Image

Now,

I'd also like to remind everyone that this is a basic, GENERAL list.

There are story elements specific to whatever kind of story you're

writing, and the best way to get familiar with what those are is to do

the story breakdowns on three (at least) movies or books that are

similar to the KIND of story you're writing.

I

strongly recommend that you watch at least one, or much better, three of

the films I break down in the workbooks, following along with my notes.

I do full breakdowns of Chinatown, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, Romancing the Stone, and The Mist, and act breakdowns of You've Got Mail, Jaws, Silence of the Lambs, Raiders of the Lost Ark in Screenwriting Tricks For Authors.

I do full breakdowns of The

Proposal, Groundhog Day, Sense and Sensibility, Romancing the Stone,

Leap Year, Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Sea of Love, While

You Were Sleeping and New in Town in Writing Love.

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Alex

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

=====================================================

HALLOWEEN GIVEAWAY

It's

October, my favorite month, and you-know-what is coming, so I'm giving

away 15 signed hardcover copies of my spooky thriller Book of Shadows . To enter, just sign up for my mailing list at http://alexandrasokoloff.com (the box on the left of the screen.)

Book of Shadows .

An

ambitious Boston homicide detective must join forces with a beautiful,

mysterious witch from Salem in a race to solve a series of satanic

killings.

Amazon Bestseller in Horror and Police Procedurals

"A wonderfully dark thriller with amazing 'Is-it-isn't-it?' suspense all the way to the end. Highly recommended."

- Lee Child

Published on October 16, 2013 09:29

October 12, 2013

Nanowrimo Prep: The Index Card Method and Story Structure Grid

So hopefully you've had enough time to watch at least one movie and note the sequences. Do you start to see how that works?

By

all means, keep watching movies to get familiar with sequence breakdown, but at the same time, let's

move on. But this is the point in the brainstorming process that I feel I need to cover several different stages at once.

First, I want to link to a blog on premise. More experienced writers will probably already have done this step, but if you have no idea what I'm talking about, go here and read.

For those of you who do have premises, and are comfortable with them, let's talk about

THE INDEX CARD METHOD

This is the number one structuring tool of most screenwriters I know. I have no idea how I would write without it.

Get

yourself a pack of index cards. You can also use Post-Its, and the

truly OCD among us use colored Post-Its to identify various subplots by

color, but I find having to make those kinds of decisions just fritzes

my brain. I like cards because they’re more durable and I can spread

them out on the floor for me to crawl around and for the cats to walk

over; it somehow feels less like work that way. Everyone has their own

method - experiment and find what works best for you.

Now,

get a corkboard or a sheet of cardboard - or even butcher paper - big

enough to lay out your index cards in either four vertical columns of

10-15 cards, or eight vertical columns of 5-8 cards, depending on

whether you want to see your story laid out in four acts or eight

sequences. You can draw lines on the corkboard to make a grid of spaces

the size of index cards if you’re very neat (I’m not) – or just pin a

few marker cards up to structure your space. I find the tri-fold boards

that kids use for science projects just perfect in size and they come

pre-folded in exactly three acts of the right size! Just a few dollars

at any Office Max or Staples.

Write Act One at the top of

the first column, Act Two: 1 at the top of the second (or third if

you’re doing eight columns), Act Two: 2 at the top of the third (or

fifth), Act Three at the top of the fourth (or seventh).

Then

write a card saying Act One Climax and pin it at the bottom of column

one, Midpoint Climax at the bottom of column two, Act Two Climax at the

bottom of column three, and Climax at the very end. If you already know

what those scenes are, then write a short description of them on the

appropriate cards. These are scenes that you know you MUST have in your

story, in those places - whether or not you know what they are right

now.

And now also label the beginning and end of where

eight sequences will go. (In other words, you’re dividing your corkboard

into eight sections – either four long columns with two sections each,

or eight shorter columns).

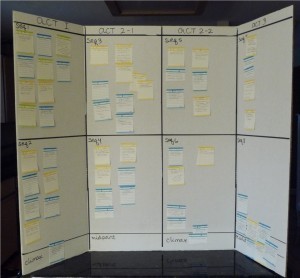

Here is a photo of the grid on a white board - with sticky Post Its as index cards:

And

an example of index cards on a tri-fold board from my friend, the

wonderful author Diane Chamberlain. (Far neater than any grid I've ever

done for myself!)

So you have your structure grid in front of you.

What you will start to do now is brainstorm scenes, and that you do with the index cards.

A

movie has about 40 to 60 scenes (a drama more like 40, an action movie

more like 60), every scene goes on one card. Now, if

you’re structuring a novel this way, you may be doubling or tripling the

scene count, but for me, the chapter count remains exactly the same:

forty to sixty chapters to a book.

This is the fun

part,

like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. All you do at first is write down

all the scenes you know about your story, one scene per card (just one

or two lines describing each scene - it can be as simple as - "Hero and

heroine meet" or - "Meet the antagonist".) You don’t

have to put them in order yet, but if you know where they go, or

approximately where they go, you can just pin them on your board in

approximately the right place. You can always move them around. And just

like with a puzzle, once you have some scenes in place, you will

naturally start to build other scenes around them.

I

love the cards because they are such an overview. You can stick a bunch

of vaguely related scenes together in a clump, rearrange one or two, and

suddenly see a perfect progression of an entire sequence. You can throw

away cards that aren’t working, or make several cards with the same

scene and try them in different parts of your story board.

You will find it is often shockingly fast and simple to structure a whole story this way.

And

this eight-sequence structure translates easily to novels. And you might have an extra sequence

or two per act, but I think that in most cases you’ll find that the

number of sequences is not out of proportion to this formula. With a

book you can have anything from 250 pages to 1000 (well, you can go that

long only if you’re a mega-bestseller!), so the length of a sequence

and the number of sequences is more variable. But an average book these

days is between 300 and 400 pages, and since the recession, publishers

are actually asking their authors to keep their books on the short side,

to save production costs, so why not shoot for that to begin with?

I

write books of about 350-400 pages (print pages), and I find my

sequences are about 50 pages, getting shorter as I near the end. But I

might also have three sequences of around 30 pages in an act that is 100

pages long. You have more leeway in a novel, but the structure remains

pretty much the same.

In the next few posts we’ll talk

about how to plug various obligatory scenes into this formula to make

the structuring go even more quickly – key scenes that you’ll find in nearly

all stories, like opening image, closing image, introduction of hero,

inner and outer desire, stating the theme, call to adventure/inciting incident, introduction of allies,

love interest, mentor, opponent, hero’s and opponent’s plans, plants and

reveals, setpieces, training sequence, dark night of the soul, sex at

sixty, hero’s arc, moral decision, etc.

And for those

of you who are reeling in horror at the idea of a formula… it’s just a

way of analyzing dramatic structure. No matter how you create a story

yourself, chances are it will organically follow this flow. Think of the

human body: human beings (with very few exceptions) have the exact same

skeleton underneath all the complicated flesh and muscles and nerves

and coloring and neurons and emotions and essences that make up a human

being. No two alike… and yet a skeleton is a skeleton; it’s the

foundation of a human being.

And structure is the foundation of a story.

ASSIGNMENTS:

Make

two blank structure grids, one for the movie you have chosen from your

master list to analyze, and one for your WIP (Work In Progress). You

can just do a structure grid on a piece of paper for the movie you’ve

chosen to analyze, but also do a large corkboard or cardboard structure

grid for your WIP. You can fill out one structure grid while you watch

the movie you’ve chosen.

Get a pack of index cards or Post Its

and write down all the scenes you know about your story, and where

possible, pin them onto your WIP structure grid in approximately the

place they will occur.

If you are already well

into your first draft, then by all means, keep writing forward, too – I

don’t want you to stop your momentum. Use whatever is useful about what

I’m talking about here, but also keep moving.

And if

you have a completed draft and are starting a revision, a structure grid

is a perfect tool to help you identify weak spots and build on what you

have for a rewrite. Put your story on cards and watch how quickly you

start to rearrange things that aren’t working!

Now, let

me be clear. When you’re brainstorming with your index cards and you

suddenly have a full-blown idea for a scene, or your characters start

talking to you, then of course you should drop everything and write out

the scene, see where it goes. Always write when you have a hot flash. I

mean – you know what I mean. Write when you’re hot.

Ideally I will always be working on four piles of material, or tracks, at once:

1. The index cards I'm brainstorming and arranging on my structure grid.

2.

A notebook of random scenes, dialogue, character descriptions that are

coming to me as I'm outlining, and that I can start to put in

chronological order as this notebook gets bigger.

3. An expanded on-paper (or in Word) story outline that I'm compiling as I order my index cards on the structure grid.

4.

A collage book of visual images that I'm pulling from magazines that

give me the characters, the locations, the colors and moods of my story

(we will talk about Visual Storytelling soon.)

In the

beginning of a project you will probably be going back and forth between

all of those tracks as you build your story. Really this is my favorite

part of the writing process – building the world – which is probably

part of why I stay so long on it myself. But by the time I start my

first draft I have so much of the story already that it’s not anywhere

near the intimidating experience it would be if I hadn’t done all that

prep work.

At some point (and a deadline has a lot to

do with exactly when this point comes!) I feel I know the shape of the

story well enough to start that first draft. Because I come from

theater, I think of my first draft as a blocking draft. When you direct a

play, the first rehearsals are for blocking – which means simply

getting the actors up on their feet and moving them through the play on

the stage so everyone can see and feel and understand the whole shape of

it. That’s what a first draft is to me, and when I start to write a

first draft I just bash through it from beginning to end. It’s the most

grueling part of writing, and takes the longest, but writing the whole

thing out, even in the most sketchy way, from start to finish, is the

best way I know to actually guarantee that you will finish a book or a

script.

Everything after that initial draft is frosting

– it’s seven million times easier to rewrite than to get something onto

a blank page.

Then I do layer after layer after layer –

different drafts for suspense, for character, sensory drafts, emotional

drafts – each concentrating on a different aspect that I want to hone

in the story – until the clock runs out and I have to turn the whole

thing in.

But that’s my process. You have to find your

own. If outlining is cramping your style, then you’re probably a

“pantser” – not my favorite word, but common book jargon for a person

who writes best by the seat of her pants. And if you’re a pantser, the

methods I’ve been talking about have probably already made you so

uncomfortable that I can’t believe you’re still here!

Still,

I don’t think it hurts to read about these things. I maintain that

pantsers have an intuitive knowledge of story structure – we all do,

really, from having read so many books and having seen so many movies. I

feel more comfortable with this rather left-brained and concrete

process because I write intricate plots with twists and subplots I have

to work out in advance, and also because I simply wouldn’t ever work as a

screenwriter if I wasn’t able to walk into a conference room and tell

the executives and producers and director the entire story, beginning to

end. It’s part of the job.

But I can’t say this enough: WHATEVER WORKS. Literally. Whatever. If it’s getting the job done, you’re golden.

Next up - a list of essential story elements that will help you brainstorm your index cards.

- Alex

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

=====================================================

HALLOWEEN GIVEAWAY

It's

October, my favorite month, and you-know-what is coming, so I'm giving

away 15 signed hardcover copies of my spooky thriller Book of Shadows . To enter, just sign up for my mailing list at http://alexandrasokoloff.com (the box on the left of the screen.)

Book of Shadows .

An

ambitious Boston homicide detective must join forces with a beautiful,

mysterious witch from Salem in a race to solve a series of satanic

killings.

Amazon Bestseller in Horror and Police Procedurals

"A wonderfully dark thriller with amazing 'Is-it-isn't-it?' suspense all the way to the end. Highly recommended."

- Lee Child

Published on October 12, 2013 08:03

October 6, 2013

Nanowrimo Prep: The Three-Act, Eight Sequence Structure

I'm going to be traveling for the next couple of days so I wanted to leave you with an assignment that is really key to understanding story structure. Brace yourself, but you're going to need to watch a movie.

I know, it's a rough life, but art it about sacrifice....

So hopefully you took the last exercise

seriously and are now armed with a Top Ten list and a hundred pages of

all your story ideas, and woke up this morning with THE book that you

want to write for NaNoWriMo. If not, keep working! It'll come.

What

I'm going to talk about in the next few posts is the key to the story

structuring technique I write about and that everyone's always asking me

to teach. Those of you new to this blog are going to have to do a

little catch up and review the concept of the Three Act Structure (in fact, everyone should go back and review.)

But

the real secret of film writing and filmmaking, that we are going to

steal for our novel writing, is that most movies are written in a

Three-Act, Eight-Sequence structure. Yes, most movies can be broken up

into 8 discrete 12-15-minute sequences, each of which has a beginning,

middle and end.

I swear.

The

eight-sequence structure evolved from the early days of film when movies

were divided into reels (physical film reels), each holding about ten

minutes of film (movies were also shorter, proportionately). The

projectionist had to manually change each reel as it finished. Early

screenwriters (who by the way, were mostly playwrights, well-schooled in

the three-act structure) incorporated this rhythm into their writing,

developing individual sequences that lasted exactly the length of a

reel, and modern films still follow that same storytelling rhythm. (As

movies got longer, sequences got slightly longer proportionately). I'm

not sure exactly how to explain this adherence, honestly, except that,

as you will see IF you do your homework - it WORKS.

And

the eight-sequence structure actually translates beautifully to novel

structuring, although we have much more flexibility with a novel and you

might end up with a few more sequences in a book. So I want to get you

familiar with the eight-sequence structure in

film first, and we’ll go on to talk about the application to novels.

If

you’re new to story breakdowns and analysis, then you'll want to check

out my sample breakdowns (links at end of this post, and full breakdowns

are included in the workbook)

and watch several, or all, of those movies, following along with my

notes, before you try to analyze a movie on your own. But if you want

to jump right in with your own breakdowns and analyses, this is how it

works:

ASSIGNMENT:

Take a film from the master list, the Top Ten list you've made, preferably the one that is most

similar in structure to your own WIP, and screen it, watching the time

clock on your DVD player (or your watch, or phone.). At about 15 minutes into the film, there will

be some sort of climax – an action scene, a revelation, a twist, a big

SET PIECE. It won’t be as big as the climax that comes 30 minutes into

the film, which would be the Act One climax, but it will be an

identifiable climax that will spin the action into the next sequence.)

Proceed

through the movie, stopping to identify the beginning, middle, and end

of each sequence, approximately every 15 minutes. Also make note of the

bigger climaxes or turning points – Act One at 30 minutes, the Midpoint

at 60 minutes, Act Two at 90 minutes, and Act Three at whenever the

movie ends.

NOTE: You can also, and probably should,

say that a movie is really four acts, breaking the long Act Two into two

separate acts. Hollywood continues to use "Three Acts". Whichever

works best for you!

So how do you recognize a sequence?

It's

generally a series of related scenes, tied together by location and/or

time and/or action and/or the overall intent of the hero/ine.

In

many movies a sequence will take place all in the same location, then

move to another location at the climax of the sequence. The protagonist

will generally be following just one line of action in a sequence, and

then when s/he gets that vital bit of information in the climax of a

sequence, s/he’ll move on to a completely different line of action,

based on the new information. A good exercise is to title each sequence

as you watch and analyze a movie – that gives you a great overall

picture of the progression of action.

But the biggest

clue to an Act or Sequence climax is a SETPIECE SCENE: there’s a

dazzling, thematic location, an action or suspense sequence, an

intricate set, a crowd scene, even a musical number (as in The Wizard of Oz and, more surprisingly, Jaws. And Casablanca, too.).

Or,

let's not forget - it can be a sex scene. In fact for my money ANY sex

scene in a book or film should be approached as a setpiece.

The setpiece is a fabulous lesson to take from filmmaking, one of the most valuable for novelists, and possibly the most crucial for screenwriters.

There are multiple definitions of a setpiece. It can be a huge action scene like, well, anything in The Dark Knight,

that takes weeks to shoot and costs millions, requiring multiple sets,

special effects and car crashes… or a meticulously planned suspense

scene with multiple cuts that takes place all in - a shower, for

instance, in Psycho.

If

you start watching movies specifically to pick out the setpiece scenes,

you’ll notice an interesting thing. They’re almost always used as act

or sequence climaxes. They are tentpoles holding the structure of the

movie up… or jewels in the necklace of the plotline. The scenes

featured in the trailers to entice people to see the movie. The scenes

everyone talks about after the credits roll.

That elaborate, booby-trapped cave in the first scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The crop-dusting plane chasing Cary Grant through the cornfield in North By Northwest. The goofy galactic bar in Star Wars. Munchkinland, the Scarecrow’s cornfield, the dark forest, the poppy field, the Emerald City, the witch’s castle in The Wizard of Oz. The dungeon – I mean prison – in Silence of the Lambs.

In fact you can look Raiders and Silence and see that every single

sequence contains a wonderful setpiece (The Nepalese bar, the

suspension bridge, the temple in Raiders…)

Those are

actually two great movies to use to compare setpieces, because one is so

big and action-oriented (Raiders) and one is so small, confined and

psychological (Silence), yet both are stunning examples of visual

storytelling.

A really great setpiece scene is a lot

more than just dazzling. It’s thematic, too, such as the prison

(dungeon for the criminally insane) in Silence of the Lambs.

That is much more than your garden variety prison. It’s a labyrinth

of twisty staircases and creepy corridors. And it’s hell: Clarice goes

through – count ‘em – seven gates, down, down, down under the ground to

get to Lecter. Because after all, she’s going to be dealing with the

devil, isn’t she? And the labyrinth is a classic symbol of an inner

psychological journey, just exactly what Clarice is about to go through.

And Lecter is a monster, like the Minotaur, so putting him smack in

the center of a labyrinth makes us unconsciously equate him with a

mythical beast, something both more and less than human. The visuals of

that setpiece express all of those themes perfectly (and others, too)

so the scene is working on all kinds of visceral, emotional,

subconscious levels.

Now, yes, that’s brilliant

filmmaking by director Jonathan Demme, and screenwriter Ted Talley and

production designer Kristi Zea and DP Tak Fujimoto… but it was all there

on Harris’s page, first, all that and more; the filmmakers had the good

sense to translate it to the screen. In fact, both Silence of the Lambs and Thomas Harris's Red Dragon

are so crammed full of thematic visual imagery you can catch something

new every time you reread those books, which made them slam dunks as

movies.

So here's another ASSIGNMENT for you: Bring me setpieces. What are some great ones? Check your watch. Are they act or sequence climaxes?

Another note about sequences: be advised that in big, sprawling movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,

sequences may be longer or there may be a few extras. It’s a formula

and it doesn’t always precisely fit, but as you work through your master

list of films, unless you are a surrealist at heart, you will be

shocked and amazed at how many movies precisely fit this eight-sequence

format. When you’re working with as rigid a form as a two-hour movie, on

the insane schedule that is film production, this kind of mathematical

precision is kind of a lifesaver.

Now, I could talk

about this for just about ever, but me talking is not going to get you

anywhere. You need to DO this. Watch the movies yourself. Do the

breakdowns yourself. Identify setpieces yourself. Ask as many

questions as you want here, but DO it - it's the only way you're really

going to learn this.

My advice is that you watch and

analyze all ten of your master list movies (and books). But not all at

once - screening one will get you far, three will lock it in, the rest

will open new worlds in your writing.

And every time

you see a movie now, for the rest of your life, look for the sequence

breaks and act climaxes, and setpieces. At first you will embarrass

yourself in theaters, shouting out things like "Hot damn!" Or "Holy

!@#$!!!"as you experience a climax. An Act Climax. But

eventually, it will be as natural to you as breathing, and you will find

yourself incorporating this rhythm into your storytelling without even

having to think about it. You may even be doing it already.

So go, go, watch some movies. It's WORK. And please, report your findings back here.

- Alex

===================================================

And

if you'd like to to see more of these story elements in action, I

strongly recommend that you watch at least one and much better, three of

the films I break down in the workbooks, following along with my notes.

I do full breakdowns of Chinatown, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, Romancing the Stone, and The Mist, and act breakdowns of You've Got Mail, Jaws, Silence of the Lambs, Raiders of the Lost Ark in Screenwriting Tricks For Authors.

I do full breakdowns of The

Proposal, Groundhog Day, Sense and Sensibility, Romancing the Stone,

Leap Year, Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Sea of Love, While

You Were Sleeping and New in Town in Writing Love.

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

I know, it's a rough life, but art it about sacrifice....

So hopefully you took the last exercise

seriously and are now armed with a Top Ten list and a hundred pages of

all your story ideas, and woke up this morning with THE book that you

want to write for NaNoWriMo. If not, keep working! It'll come.

What

I'm going to talk about in the next few posts is the key to the story

structuring technique I write about and that everyone's always asking me

to teach. Those of you new to this blog are going to have to do a

little catch up and review the concept of the Three Act Structure (in fact, everyone should go back and review.)

But

the real secret of film writing and filmmaking, that we are going to

steal for our novel writing, is that most movies are written in a

Three-Act, Eight-Sequence structure. Yes, most movies can be broken up

into 8 discrete 12-15-minute sequences, each of which has a beginning,

middle and end.

I swear.

The

eight-sequence structure evolved from the early days of film when movies

were divided into reels (physical film reels), each holding about ten

minutes of film (movies were also shorter, proportionately). The

projectionist had to manually change each reel as it finished. Early

screenwriters (who by the way, were mostly playwrights, well-schooled in

the three-act structure) incorporated this rhythm into their writing,

developing individual sequences that lasted exactly the length of a

reel, and modern films still follow that same storytelling rhythm. (As

movies got longer, sequences got slightly longer proportionately). I'm

not sure exactly how to explain this adherence, honestly, except that,

as you will see IF you do your homework - it WORKS.

And

the eight-sequence structure actually translates beautifully to novel

structuring, although we have much more flexibility with a novel and you

might end up with a few more sequences in a book. So I want to get you

familiar with the eight-sequence structure in

film first, and we’ll go on to talk about the application to novels.

If

you’re new to story breakdowns and analysis, then you'll want to check

out my sample breakdowns (links at end of this post, and full breakdowns

are included in the workbook)

and watch several, or all, of those movies, following along with my

notes, before you try to analyze a movie on your own. But if you want

to jump right in with your own breakdowns and analyses, this is how it

works:

ASSIGNMENT:

Take a film from the master list, the Top Ten list you've made, preferably the one that is most

similar in structure to your own WIP, and screen it, watching the time

clock on your DVD player (or your watch, or phone.). At about 15 minutes into the film, there will

be some sort of climax – an action scene, a revelation, a twist, a big

SET PIECE. It won’t be as big as the climax that comes 30 minutes into

the film, which would be the Act One climax, but it will be an

identifiable climax that will spin the action into the next sequence.)

Proceed

through the movie, stopping to identify the beginning, middle, and end

of each sequence, approximately every 15 minutes. Also make note of the

bigger climaxes or turning points – Act One at 30 minutes, the Midpoint

at 60 minutes, Act Two at 90 minutes, and Act Three at whenever the

movie ends.

NOTE: You can also, and probably should,

say that a movie is really four acts, breaking the long Act Two into two

separate acts. Hollywood continues to use "Three Acts". Whichever

works best for you!

So how do you recognize a sequence?

It's

generally a series of related scenes, tied together by location and/or

time and/or action and/or the overall intent of the hero/ine.

In

many movies a sequence will take place all in the same location, then

move to another location at the climax of the sequence. The protagonist

will generally be following just one line of action in a sequence, and

then when s/he gets that vital bit of information in the climax of a

sequence, s/he’ll move on to a completely different line of action,

based on the new information. A good exercise is to title each sequence

as you watch and analyze a movie – that gives you a great overall

picture of the progression of action.

But the biggest

clue to an Act or Sequence climax is a SETPIECE SCENE: there’s a

dazzling, thematic location, an action or suspense sequence, an

intricate set, a crowd scene, even a musical number (as in The Wizard of Oz and, more surprisingly, Jaws. And Casablanca, too.).

Or,

let's not forget - it can be a sex scene. In fact for my money ANY sex

scene in a book or film should be approached as a setpiece.

The setpiece is a fabulous lesson to take from filmmaking, one of the most valuable for novelists, and possibly the most crucial for screenwriters.

There are multiple definitions of a setpiece. It can be a huge action scene like, well, anything in The Dark Knight,

that takes weeks to shoot and costs millions, requiring multiple sets,

special effects and car crashes… or a meticulously planned suspense

scene with multiple cuts that takes place all in - a shower, for

instance, in Psycho.

If

you start watching movies specifically to pick out the setpiece scenes,

you’ll notice an interesting thing. They’re almost always used as act

or sequence climaxes. They are tentpoles holding the structure of the

movie up… or jewels in the necklace of the plotline. The scenes

featured in the trailers to entice people to see the movie. The scenes

everyone talks about after the credits roll.

That elaborate, booby-trapped cave in the first scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The crop-dusting plane chasing Cary Grant through the cornfield in North By Northwest. The goofy galactic bar in Star Wars. Munchkinland, the Scarecrow’s cornfield, the dark forest, the poppy field, the Emerald City, the witch’s castle in The Wizard of Oz. The dungeon – I mean prison – in Silence of the Lambs.

In fact you can look Raiders and Silence and see that every single

sequence contains a wonderful setpiece (The Nepalese bar, the

suspension bridge, the temple in Raiders…)

Those are

actually two great movies to use to compare setpieces, because one is so

big and action-oriented (Raiders) and one is so small, confined and

psychological (Silence), yet both are stunning examples of visual

storytelling.

A really great setpiece scene is a lot

more than just dazzling. It’s thematic, too, such as the prison

(dungeon for the criminally insane) in Silence of the Lambs.

That is much more than your garden variety prison. It’s a labyrinth

of twisty staircases and creepy corridors. And it’s hell: Clarice goes

through – count ‘em – seven gates, down, down, down under the ground to

get to Lecter. Because after all, she’s going to be dealing with the

devil, isn’t she? And the labyrinth is a classic symbol of an inner

psychological journey, just exactly what Clarice is about to go through.

And Lecter is a monster, like the Minotaur, so putting him smack in

the center of a labyrinth makes us unconsciously equate him with a

mythical beast, something both more and less than human. The visuals of

that setpiece express all of those themes perfectly (and others, too)

so the scene is working on all kinds of visceral, emotional,

subconscious levels.

Now, yes, that’s brilliant

filmmaking by director Jonathan Demme, and screenwriter Ted Talley and

production designer Kristi Zea and DP Tak Fujimoto… but it was all there

on Harris’s page, first, all that and more; the filmmakers had the good

sense to translate it to the screen. In fact, both Silence of the Lambs and Thomas Harris's Red Dragon

are so crammed full of thematic visual imagery you can catch something

new every time you reread those books, which made them slam dunks as

movies.

So here's another ASSIGNMENT for you: Bring me setpieces. What are some great ones? Check your watch. Are they act or sequence climaxes?

Another note about sequences: be advised that in big, sprawling movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,

sequences may be longer or there may be a few extras. It’s a formula

and it doesn’t always precisely fit, but as you work through your master

list of films, unless you are a surrealist at heart, you will be

shocked and amazed at how many movies precisely fit this eight-sequence

format. When you’re working with as rigid a form as a two-hour movie, on

the insane schedule that is film production, this kind of mathematical

precision is kind of a lifesaver.

Now, I could talk

about this for just about ever, but me talking is not going to get you

anywhere. You need to DO this. Watch the movies yourself. Do the

breakdowns yourself. Identify setpieces yourself. Ask as many

questions as you want here, but DO it - it's the only way you're really

going to learn this.

My advice is that you watch and

analyze all ten of your master list movies (and books). But not all at

once - screening one will get you far, three will lock it in, the rest

will open new worlds in your writing.

And every time

you see a movie now, for the rest of your life, look for the sequence

breaks and act climaxes, and setpieces. At first you will embarrass

yourself in theaters, shouting out things like "Hot damn!" Or "Holy

!@#$!!!"as you experience a climax. An Act Climax. But

eventually, it will be as natural to you as breathing, and you will find

yourself incorporating this rhythm into your storytelling without even

having to think about it. You may even be doing it already.

So go, go, watch some movies. It's WORK. And please, report your findings back here.

- Alex

===================================================

And

if you'd like to to see more of these story elements in action, I

strongly recommend that you watch at least one and much better, three of

the films I break down in the workbooks, following along with my notes.

I do full breakdowns of Chinatown, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, Romancing the Stone, and The Mist, and act breakdowns of You've Got Mail, Jaws, Silence of the Lambs, Raiders of the Lost Ark in Screenwriting Tricks For Authors.

I do full breakdowns of The

Proposal, Groundhog Day, Sense and Sensibility, Romancing the Stone,

Leap Year, Notting Hill, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Sea of Love, While

You Were Sleeping and New in Town in Writing Love.

=====================================================

Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are now available in all e formats and as pdf files. Either book, any format, just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Published on October 06, 2013 12:05

October 3, 2013

Nanowrimo Prep: First, You Need an Idea

When people ask, “Where do you get your ideas?”,

authors tend to clam up or worse, get sarcastic - because the only real

answer to that is, “Where DON’T I get ideas?” or even more to the point,

“How do I turn these ideas OFF?”

The thing is, “Where do you get your ideas?” is not the real question

these people are asking. The real question is “How do you go from an

idea to a coherent story line that holds up – and holds a reader’s

interest - for 400 pages of a book?”

Or more concisely: “How do you come up with your PREMISES?”

Look, we all have story ideas all the time. Even non-writers, and

non-aspiring writers – I truly mean, EVERYONE, has story ideas all the

time. Those story ideas are called daydreams, or fantasies, or often

“Porn starring me and Edward Cullen, or me and Stringer Bell,” (or maybe

both. Wrap your mind around that one for a second…)

But you see what I mean.

We all create stories in our own heads all the time, minimal as some of our plot lines may be.

So I bet you have dozens of ideas, hundreds. A better question is “What’s a good story idea?”

I see two essential ingredients:

A) What idea gets you excited enough to spend a year (or most likely more) of your life completely immersed in it –

and

B) Gets other people excited enough about it to buy it and read it

and even maybe possibly make it into a movie or TV series with an

amusement park ride spinoff and a Guess clothing line based on the

story?

A) is good if you just want to write for yourself.

But B) is essential if you want to be a professional writer.

As many of you know, I’m all about learning by making lists. Because let’s face it – we have to trick ourselves into writing, every

single day, and what could be simpler and more non-threatening than

making a list? Anything to avoid the actual rest of it!

So here are two lists to do to get those ideas flowing, and then we can start to narrow it all down to the best one.

List # 1: Make a list of all your story ideas.

Yes, you read that right. ALL of them.

This is a great exercise because it gets your subconscious churning

and invites it to choose what it truly wants to be working on. Your

subconscious knows WAY more than you do about writing. None of us can

do the kind of deep work that writing is all on our own. And with a

little help from the Universe you could find yourself writing the next

Harry Potter or Twilight.

Also this exercise gives you an overall idea of what your THEMES are

as a writer (and very likely the themes you have as a person). I

absolutely believe that writers only have about six or seven themes that

they’re dealing with over and over and over again. It’s my experience

that your writing improves exponentially when you become more aware of

the themes that you’re working with.

You may be amazed, looking over this list that you’ve generated, how

much overlap there is in theme (and in central characters, hero/ines and

villains, and dynamics between characters, and tone of endings).

You may even find that two of your story ideas, or a premise line

plus a character from a totally different premise line, might combine to

form a bigger, more exciting idea. That certainly happened to me with my Huntress series. Characters I'd always meant to write about suddenly fit perfectly into the new series. It was magic.

But in any case, you should have a much better idea at the end of the

exercise of what turns you on as a writer, and what would sustain you

emotionally over the long process of writing a novel.

Then just let that percolate for a while. Give yourself a little

time for the right idea to take hold of you. You’ll know what that

feels like – it’s a little like falling in love. (We’ll go more into

this in the next few days.)

List # 2: The Master List

The other list I always encourage my students to do is a list of your

ten favorite movies and books in the genre that you’re writing, or if

you don’t have a premise yet, ten movies and books that you WISH you had

written.

It’s good to compare and contrast your idea list with this IDEAL list.

This list of ten (or more, if you want – ten is just a minimum!) – is

going to be enormously helpful to you in structuring and outlining your

own novel.

Now, the novelists who have just found this blog recently may be

wondering why I’m asking you to list movies as well as books. Good

question.

The thing is, for the purposes of structural analysis, film is such a

compressed and concise medium that it’s like seeing an X-ray of a

story. In film you have two hours, really a little less, to tell the

story. It’s a very stripped-down form that even so, often has enormous

emotional power. Plus we’ve usually seen more of these movies than we’ve

read specific books, so they’re a more universal form of reference for

discussion.

It’s often easier to see the mechanics of structure in a film than in

a novel, which makes looking at films that are similar to your own

novel story a great way to jump start your novel outline.

And just practically, film has had an enormous influence on

contemporary novels, and on publishing. Editors love books with the high

concept premises, pacing, and visual and emotional impact of movies, so

being aware of classic and blockbuster films and the film techniques

that got them that status can help you write novels that will actually

sell in today’s market.

And even beyond that – studying movies is fun, and fun is something

writers just don’t let themselves have enough of. If you train yourself

to view movies looking for for some of these structural

elements I’m

going to be talking about, then every time you go to the movies or watch

something on television, you’re actually honing your craft (even on a

date or while spending quality time with your loved ones!), and after a

while you won’t even notice you’re doing it.

When the work is play, you’ve got the best of all possible worlds..

So of course I'd love to hear what personal themes you discover as you do this brainstorming!

- Alex

=====================================================

If you'd like some in-depth help with your prep, the writing workbooks based on this blog, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are available for just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Published on October 03, 2013 01:25

October 1, 2013

October is Nanowrimo PREP month

Oh my God, October. How did that happen?

Yes, I've been very missing this summer. All kinds of life changes, all wonderful, but life is so time-consuming, isn't it?

And of course, I've been working on Book 3 of the Huntress series. Which WILL be out in December. Even if it kills me. Which it might.

But I'm not so distracted that I don't remember what October is. Yes, right, Halloween. But it's also

the month before Nanowrimo, which means it's Nanowrimo PREP Month.

Because

it’s sort of ingrained in us (whether we like it or not), that fall is

the beginning of a new school year, I think fall is a good time for

making resolutions. Like, if you're an author, about that new book you’re going to be

writing for the next year or so.

I’m

sure practically everyone here is aware that November is Nanowrimo –

National Novel Writing Month. As explained at the official site here, and here and here, the goal of Nanowrimo is to bash through 50,000 words of a novel in a single month.

I

could not be more supportive of this idea – it gives focus and a nice

juicy competitive edge to an endeavor that can seem completely

overwhelming when you’re facing it all on your own. Through peer

pressure and the truly national focus on the event, Nanowrimo forces

people to commit. It’s easy to get caught up in and carried along by

the writing frenzy of tens of thousands – or maybe by now hundreds of

thousands - of “Wrimos”. And I’ve met and heard of lots of novelists,

like Carrie Ryan (The Forest of Hands and Teeth) Sara Gruen (Water For

Elephants), and Lisa Daily (The Dreamgirl Academy) who started novels

during Nanowrimo that went on to sell, sometimes sell big.

Nanowrimo works.

But

as everyone who reads this blog knows, I’m not a big fan of sitting

down and typing Chapter One at the top of a blank screen and seeing what

comes out from there. It may be fine – but it may be a disaster, or

something even worse than a disaster – an unfinished book. And it

doesn’t have to be.

I’m always asked to do Nanowrimo “pep talks”. These are always in the month of November.

That makes no sense to me.

I

mean, I’m happy to do it, but mid-November is way too late for that

kind of thing. What people should be asking me, and other authors that

they ask to do Nano support, is Nano PREP talks.

If

you’re going to put a month aside to write 50,000 words, doesn’t it make

a little more sense to have worked out the outline, or at least an

overall roadmap, before November 1? I am pretty positive that in most

cases far more writing, and far more professional writing, would get

done in November if Wrimos took the month of October – at LEAST - to

really think out some things about their story and characters, and where

the whole book is going. It wouldn’t have to be the

full-tilt-every-day frenzy that November will be, but even a half hour

per day in October, even fifteen minutes a day, thinking about what you

really want to be writing would do your potential novel worlds of good.

Because even if you never look at that prep work again, your

brilliant subconscious mind will have been working on it for you for a

whole month. Let’s face it – we don’t do this mystical thing

called writing all by ourselves, now, do we?

So once

again, I'm going to do a Nano prep series and hopefully get some people not just to commit to

Nano this year, but to give them a chance to really make something of

the month.

Here's the first thing to consider:

How do you choose the next book you write? (Or the first, if it's your first?)

I

know, I know, it chooses you. That’s a good answer, and sometimes it

IS the answer, but it’s not the only answer. And let’s face it – just

like with, well, men, sometimes the one who chooses you is NOT the one

YOU should be choosing. What makes anyone think it’s any different with

books?

It’s a huge commitment, to decide on a book to

write. That’s a minimum of six months of your life just getting it

written, not even factoring in revisions and promotion. You live in that

world for a long, long time. Not only that, but if you're a

professional writer, you're pretty much always going to be having to

work on more than one book at a time. You're writing a minimum of one

book while you're editing another and always doing promotion for a

third.

So the book you choose to write is not just

going to have to hold your attention for six to twelve months or longer with its

world and characters, but it's going to have to hold your attention

while you're working just as hard on another or two or three other

completely different projects at the same time. You're going to have

to want to come back to that book after being on the road touring a

completely different book and doing something that is both exhausting

and almost antithetical to writing (promotion).

That's a lot to ask of a story.

So how does that decision process happen?

When

on panels or at events, I have been asked, “How do you decide what book

you should write?” I have not so facetiously answered: “I write the

book that someone writes me a check for.”

That’s maybe a screenwriter thing to say, and I don’t mean that in a good way, but it’s true, isn’t it?

Anything

that you aren’t getting a check for, you’re going to have to scramble to

write, steal time for – it’s just harder. That doesn’t mean it’s not

worth doing, or that it doesn’t produce great work, but it’s harder.

As

a professional writer, you’re also constricted to a certain degree by

your genre, and even more so by your brand. I’m not allowed to turn in a

chick lit story, or a flat-out gruesome horrorfest, or probably a spy

story, either. Once you’ve published you are a certain commodity. Even

now that I'm e publishing, too, and am not so constrained by my

publishers' expectations, I have to take my readers into account.

If

you are writing a series, you're even more restricted. You have a

certain amount of freedom about your situation and plot but – you’re

going to have to write the same characters, and if your characters live

in a certain place, you’re also constricted by place. Now that I’m

doing my Huntress series, I am learning that every decision I make about the books

is easier in a way, because so many elements are already defined, but

it’s also way more limiting than my standalones and I could see how it

would get frustrating.

If you have an agent, then input from her or him is key, of

course - you are a team and you are shaping your career together. Your

agent will steer you away from projects that are in a genre that is

glutted, saving you years of work over the years, and s/he will help you

make all kinds of big-pitcure decisions.

But what I’m

really interested in right now is not the restrictions but the limitless

possibilities. I'll get more specific next post.

For now let's just think about it, and discuss if you feel like it:

- How DO you decide what to write? Do commercial concerns factor into it?

- And, do you know what you're working on for Nano?

Happy Fall, everyone...

- Alex

=====================================================

And if you'd like some in-depth help with your prep, the writing workbooks based on this blog, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are available for just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Yes, I've been very missing this summer. All kinds of life changes, all wonderful, but life is so time-consuming, isn't it?

And of course, I've been working on Book 3 of the Huntress series. Which WILL be out in December. Even if it kills me. Which it might.

But I'm not so distracted that I don't remember what October is. Yes, right, Halloween. But it's also

the month before Nanowrimo, which means it's Nanowrimo PREP Month.

Because

it’s sort of ingrained in us (whether we like it or not), that fall is

the beginning of a new school year, I think fall is a good time for

making resolutions. Like, if you're an author, about that new book you’re going to be

writing for the next year or so.

I’m

sure practically everyone here is aware that November is Nanowrimo –

National Novel Writing Month. As explained at the official site here, and here and here, the goal of Nanowrimo is to bash through 50,000 words of a novel in a single month.

I

could not be more supportive of this idea – it gives focus and a nice

juicy competitive edge to an endeavor that can seem completely

overwhelming when you’re facing it all on your own. Through peer

pressure and the truly national focus on the event, Nanowrimo forces

people to commit. It’s easy to get caught up in and carried along by

the writing frenzy of tens of thousands – or maybe by now hundreds of

thousands - of “Wrimos”. And I’ve met and heard of lots of novelists,

like Carrie Ryan (The Forest of Hands and Teeth) Sara Gruen (Water For

Elephants), and Lisa Daily (The Dreamgirl Academy) who started novels

during Nanowrimo that went on to sell, sometimes sell big.

Nanowrimo works.

But

as everyone who reads this blog knows, I’m not a big fan of sitting

down and typing Chapter One at the top of a blank screen and seeing what

comes out from there. It may be fine – but it may be a disaster, or

something even worse than a disaster – an unfinished book. And it

doesn’t have to be.

I’m always asked to do Nanowrimo “pep talks”. These are always in the month of November.

That makes no sense to me.

I

mean, I’m happy to do it, but mid-November is way too late for that

kind of thing. What people should be asking me, and other authors that

they ask to do Nano support, is Nano PREP talks.

If

you’re going to put a month aside to write 50,000 words, doesn’t it make

a little more sense to have worked out the outline, or at least an

overall roadmap, before November 1? I am pretty positive that in most

cases far more writing, and far more professional writing, would get

done in November if Wrimos took the month of October – at LEAST - to

really think out some things about their story and characters, and where

the whole book is going. It wouldn’t have to be the

full-tilt-every-day frenzy that November will be, but even a half hour

per day in October, even fifteen minutes a day, thinking about what you

really want to be writing would do your potential novel worlds of good.

Because even if you never look at that prep work again, your

brilliant subconscious mind will have been working on it for you for a

whole month. Let’s face it – we don’t do this mystical thing

called writing all by ourselves, now, do we?

So once

again, I'm going to do a Nano prep series and hopefully get some people not just to commit to

Nano this year, but to give them a chance to really make something of

the month.

Here's the first thing to consider:

How do you choose the next book you write? (Or the first, if it's your first?)

I

know, I know, it chooses you. That’s a good answer, and sometimes it

IS the answer, but it’s not the only answer. And let’s face it – just

like with, well, men, sometimes the one who chooses you is NOT the one

YOU should be choosing. What makes anyone think it’s any different with

books?

It’s a huge commitment, to decide on a book to

write. That’s a minimum of six months of your life just getting it

written, not even factoring in revisions and promotion. You live in that

world for a long, long time. Not only that, but if you're a

professional writer, you're pretty much always going to be having to

work on more than one book at a time. You're writing a minimum of one

book while you're editing another and always doing promotion for a

third.

So the book you choose to write is not just

going to have to hold your attention for six to twelve months or longer with its

world and characters, but it's going to have to hold your attention

while you're working just as hard on another or two or three other

completely different projects at the same time. You're going to have

to want to come back to that book after being on the road touring a

completely different book and doing something that is both exhausting

and almost antithetical to writing (promotion).

That's a lot to ask of a story.

So how does that decision process happen?

When

on panels or at events, I have been asked, “How do you decide what book

you should write?” I have not so facetiously answered: “I write the

book that someone writes me a check for.”

That’s maybe a screenwriter thing to say, and I don’t mean that in a good way, but it’s true, isn’t it?

Anything

that you aren’t getting a check for, you’re going to have to scramble to

write, steal time for – it’s just harder. That doesn’t mean it’s not

worth doing, or that it doesn’t produce great work, but it’s harder.

As

a professional writer, you’re also constricted to a certain degree by

your genre, and even more so by your brand. I’m not allowed to turn in a

chick lit story, or a flat-out gruesome horrorfest, or probably a spy

story, either. Once you’ve published you are a certain commodity. Even

now that I'm e publishing, too, and am not so constrained by my

publishers' expectations, I have to take my readers into account.

If

you are writing a series, you're even more restricted. You have a

certain amount of freedom about your situation and plot but – you’re

going to have to write the same characters, and if your characters live

in a certain place, you’re also constricted by place. Now that I’m

doing my Huntress series, I am learning that every decision I make about the books

is easier in a way, because so many elements are already defined, but

it’s also way more limiting than my standalones and I could see how it

would get frustrating.

If you have an agent, then input from her or him is key, of

course - you are a team and you are shaping your career together. Your

agent will steer you away from projects that are in a genre that is

glutted, saving you years of work over the years, and s/he will help you

make all kinds of big-pitcure decisions.

But what I’m

really interested in right now is not the restrictions but the limitless

possibilities. I'll get more specific next post.

For now let's just think about it, and discuss if you feel like it:

- How DO you decide what to write? Do commercial concerns factor into it?

- And, do you know what you're working on for Nano?

Happy Fall, everyone...

- Alex

=====================================================

And if you'd like some in-depth help with your prep, the writing workbooks based on this blog, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors and Writing Love, Screenwriting Tricks for Authors, II, are available for just $2.99.

- Kindle

- Amazon UK

- Amaxon DE (Eur. 2.40)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)

- Smashwords (includes online viewing and pdf file)- Amazon/Kindle

- Barnes & Noble/Nook

- Amazon UK

- Amazon DE

Published on October 01, 2013 06:36

June 21, 2013

Indie Publishing: Are You Willing to Do What It Takes?

I’ve promised to do more posts on indie publishing, so here’s

another! Let’s call this one a reality check.

These days I can’t go a day without someone e mailing me or

stopping me at whatever event I’m at, wanting me to tell them everything I know

about indie publishing. This is on the surface good news for me, because it

means I’ve made enough of a success at it that people want to know what I know.

But it’s also starting to piss me off.

Because what most of these people are asking for is a magic

formula. They want a silver bullet, an easy answer to a vastly complicated

question.

The fact is, I studied indie publishing methods for over a YEAR

before I put out my indie bestseller, Thriller Award-nominated Huntress Moon.

Last week I did an indie publishing seminar at the West Texas Writers Academy. I spoke for an hour and a half. I think I communicated some of the pros and cons, made some new authors aware of some different choices writers have these days, and pointed people to some good resources to start with.

But did I sum up everything I learned in my year plus of research?

Not even close. Not even a scratch.

You don’t get that kind of knowledge by listening to a speaker for an hour and a half, or reading a couple of blog posts on the subject. You have to get your hands dirty.

Have most of the people who ask me how to indie publish even

read Huntress Moon ? Even to the extent of downloading a free sample of it? (although

if you can’t pay $3.99 for a book by an author whose methods you’re studying,

do you really expect anyone to pay for YOUR books when the time comes? Think about

it. )