Bryan Pearson's Blog, page 24

September 14, 2015

Putting the Cart Before the Smart: 4 Ways to Bend Technology to Your Favor

The smart cart has been dumbed down.

More than a decade ago, retail pundits were practically breathless over the possibilities of magical smart carts that would transform the customer experience. In reality, they were putting the cart before the smart.

While the path of the American shopping cart has been a storied one, its most compelling chapters may just be arriving now, through beacon technology and on-demand home ordering. Still, with everyone holding their own little smart carts in their hands in the forms of smartphones, the key for retailers is not making the cart – or phone – smarter, but designing the technology they deploy with the shopper experience in mind.

While the path of the American shopping cart has been a storied one, its most compelling chapters may just be arriving now, through beacon technology and on-demand home ordering. Still, with everyone holding their own little smart carts in their hands in the forms of smartphones, the key for retailers is not making the cart – or phone – smarter, but designing the technology they deploy with the shopper experience in mind.

Those experiential opportunities are increasingly plentiful. Nearly 70 percent of consumers use their mobile devices to find a brand or product before they go grocery shopping, while 86 percent use their devices to plan their shopping trips, according to 2014 research by NinthDecimal, a mobile intelligence consultant. Almost 60 percent of consumers use their phones while grocery shopping, representing a 16 percent increase over 2013.

Still, while the possibilities are plentiful, they are not without limit, as a look into the fleeting opportunities of the grocery cart reveal.

A rolling history

The first grocery carts rolled into the aisles of Piggly Wiggly stores almost 80 years ago. In less than four years, entire supermarkets were being planned around them, with wider aisles and larger checkout counters to accommodate the increased amount of products people were buying. One could credit the shopping cart for 64-ounce detergent packages, and 16-roll toilet paper bundles.

Over the years, the basic design of the shopping cart has not much changed, though its technology – or technological potential – has. From tracers that showed grocers how we shopped to LCD screens that could map out the store and alert us to sales, the cart had been earmarked as a central device for improving the shopping trip. Consider this excerpt from a 2003 USA Today story:

“The smart shopping cart looks like a normal one except for an interactive screen and scanner mounted near the shopper. Once the shopper swipes his store card, his shopping history is available for all kinds of purposes, from presenting a suggested shopping list to alerting him to discounts or reminding him about perishables purchased a month ago.”

Sound familiar? It turns out that hitching the customer experience to the shopping cart is expensive. Instead we have smartphones doing much of that work for us, pretty affordably. They enable beacon technology that can identify a shopper in close range of a specific product, map out a store and deliver a host of other in-the-aisle features.

A central problem remains, however: Retailers have yet to enable the phones to deliver the kinds of relevant experiences that elevate the task of grocery shopping from featureless to fun.

New shopping list

Can a phone, regardless of its smarts, transform the task of selecting just-the-right banana bunch and bone-in chicken breasts into something one can look forward to? The resolution exists not in how much technology a shopper really needs to get the job done, but in what specific experiences the technology can deliver to make the job a pleasure.

At a time when grocers are competing with drug stores, gas stations, mass merchants, online merchants and even some department stores for the grocery dollar, technology alone will not give the supermarket an edge.

However, all the pieces are there to reshape the in-aisle encounter to an event that includes an element of happy surprise. It is up to grocery retailers to build the infrastructure and test what will bring this journey to fruition. My simple suggestions:

Learn how to connect: Let’s all assume we can bypass the smart cart and go straight for the smartphone. How will you use it to connect with the customer in a way that is personally relevant? Beacons are popular, but note that in-store promotions do not necessarily translate to a happy experience, especially if the shopper is in a hurry. Perhaps a greeting at the beginning of the trip that asks, “What brings you here today?” can be used to inform the rest of the trip communications.

Be brand true: A grocer’s personal shopper communications, whether by smartphone or cashier, should hinge on its brand promise, mission and why its shoppers choose that brand. Once this is determined, the company can build a platform so its specially appointed team can hear customers in real time and then craft appropriate experiences to reinforce the brand promise.

Pass it on: A customer message that sits with the marketing team is a message in a vacuum. By developing an in-house system for sharing what the customer says throughout the organization, it can discover unexpected potential in its marketing efforts, product placement and customer interests.

Deliver: As with any experience-enhancing endeavor, the company should ensure it has the budget to deliver on the initiative’s promise. It sounds simple, but sometimes customer reaction differs from what we might expect. A recent case in point involves British grocery chain Waitrose, which offered free coffee or tea to its myWaitrose loyalty members, and ended up getting hordes of free drinkers who bought no groceries – irritating lots of paying customers.

No cart, or phone, can outsmart that sort of oversight.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

September 9, 2015

When the Butt Stopped Here: What Banning Tobacco Has Meant for CVS

It has been a year since CVS Health banned the sale of tobacco at its stores, and retail marketers can learn much from this risky shift. But sales tell only part of the story – the bigger challenge involved aligning the brand to its values with a clear strategic direction.

CVS stopped selling nicotine products at its 7,600 stores on Sept. 3, 2014. The surprising move won the praise of health advocates and the White House but had many loyalty marketers wondering: Was the nation’s No. 2 pharmacy chain abandoning a sizable segment of its loyal customer base? A review of its public records reveals the answer, and what retail marketers can learn from the shift.

First, it is worth considering the importance of CVS’ loyalty program, ExtraCare, launched 14 years ago. It is one of the largest such initiatives in the country, with more than 70 million members at the time it cut tobacco sales.

With an estimated 44 million Americans smoking in 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it was likely CVS’ decision would affect some of its loyalty members.

Cigarettes, health care don’t mix

CVS, however, was resolute in its decision, saying the move was in sync with broader efforts to evolve from a traditional drugstore chain to a health care merchant.

“Now more than ever, pharmacies are on the front line of health care, becoming more involved in chronic disease management to help patients with high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes,” Mike DeAngelis, CVS spokesman, told loyalty publication COLLOQUY at the time. “All of these conditions are made worse by smoking, and cigarettes have no place in a setting where health care is delivered.”

More than $6 billion

A year later, CVS has reinforced its health focus in many ways, from changing the company name from CVS Caremark to CVS Health to agreeing to acquire Omnicare, a move that will expand its presence in the senior health care market. Its sales performance, meanwhile, has not suffered at all, based on a review of public records and reports.

At the time of its decision, CVS projected the elimination of tobacco products would cost the company about $2 billion in 2014 sales (the estimated total of its tobacco sales). Instead, sales rose, to $139.4 billion from almost $126.8 billion in 2013. In 2015 sales continue to climb: Net revenue for the first six months of this year advanced by more than $6 billion, to $73.5 billion from $67.3 billion.

This is not to imply that the removal of tobacco had a direct correlation with increased sales. Store expansions, promotions and other efforts very well could be credited for the gain. In fact, I am sure CVS realized the risk involved in making such a big decision – one that could affect sales volume and customers. However, that risk can be more than offset if it is part of a holistic practice of aligning a brand to its values with a clear strategic direction, which we will explore next.

Pressure’s on

The decision by CVS put pressure on other retailers to follow suit and eliminate tobacco sales, but so far none of the major merchants has done so. Target had quit selling cigarettes in 2006, but Walmart, Walgreens and others have not followed suit. They may, in fact, have benefited from CVS’ cessation.

CVS and Target, meanwhile, have since become retail partners, as Target has agreed to sell its pharmacy business to CVS. As I wrote in June, the two merchants have much to gain from their alignment, expected to be complete in 2016. Shifting the pharmacy brand from Target to CVS improves the opportunity to attract more customers and foot traffic through Target stores, while unloading what was for Target a well-regulated distraction.

It also enables the two retailers to benefit from sharing the data derived from each one’s loyalty programs that have not been abandoned by smokers.

What can retail marketers learn from CVS’ shift away from tobacco? I note three important features of the decision:

• It was a partnership: Among CVS business partners and clients are health plan providers and physicians. Many of these physicians have been trying to get their patients off of tobacco, while health care providers are interested in ensuring their members take their medications and improve their health, Chief Financial Officer Dave Denton told analysts in June 2014. By removing tobacco products from its aisles, CVS is supporting its clients, a commitment that will likely pay off in dividends.

• It was part of something bigger: Once CVS decided to stop selling tobacco products, it aligned the entire company behind its commitment to the mission of healthy living. I suspect that many of its high-value, target customers are similarly focused on healthy lifestyles, and if so, CVS is in essence tailoring its offerings to the preferences of its customers.

• It relied on data: CVS knew it stood to lose $2 billion a year in tobacco sales, but it clearly also knew what its best customers value and aspire to. The company’s ExtraCare and MyWeeklyAd customized coupon programs are designed to help CVS connect directly with customers, CVS wrote in its annual report. This means it has a clear line of sight to what influences their purchase decisions – for example, the basket size and frequency among smoking and non-smoking customers.

With tobacco off of its shelves, CVS is reporting higher sales and profits and signing substantial partnerships with major retail partners. Few people complain they are worse off after quitting smoking, and the same may very well apply to CVS.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

August 31, 2015

To Fee or Not to Fee? What Charging for Loyalty Can Get You

Let’s make one point clear: Fee-based rewards are not pet rocks.

Sure, some major merchants have recently launched fee-based loyalty initiatives, but that does not make the concept a fad. Rather, a retailer’s decision on whether to apply a fee to its rewards membership – or not – is very strategic in design.

Consider the recently launched shopping club Jet.com. Or Walmart’s new delivery program, called Shipping Pass. Each charges about $50 a year and is considered a shot across the bow at Amazon Prime, a successful program that charges $99 a year for free two-day shipping as well as video streaming.

Consider the recently launched shopping club Jet.com. Or Walmart’s new delivery program, called Shipping Pass. Each charges about $50 a year and is considered a shot across the bow at Amazon Prime, a successful program that charges $99 a year for free two-day shipping as well as video streaming.

With an estimated 44 million members, Prime is not a fad. Nor is iRewards, the fee-based rewards program operated for years by Canadian chain Indigo Books & Music. Rather, they are functions of each brand’s proposition.

In fact, both also offer free programs alongside their fee programs. Amazon recently launched the Amazon Prime Store Card, which instead of points gives its members 5 percent back on purchases. Indigo, meanwhile, in September will change its long-serving rewards program, called plum, a points-based loyalty initiative – more on that soon.

The takeaway is that fee and non-fee programs not only co-exist successfully, but that they also can co-exist under the same brand. The task is ensuring each model services the retailer’s mission, as well as the predetermined needs of loyal customers.

Indigo’s approach, by the book

To appreciate the strategy that goes into the fee/no-fee decision, it helps to review the evolution of Indigo and its programs.

With iRewards, Indigo gave its customers the option to self-select memberships, the net benefit being discounts on books. It also helped segment is customer base: By setting a fee (now $35 a year), Indigo effectively made the program interesting only to its best customers – people who spent upward of $750 per year on books.

The retailer’s strategic planners were clearly applying the Pareto principle, or 80-20 rule. They were addressing the interests of those 20 percent of customers who represented a disproportionate amount of sales and profits.

Then in 2011, Indigo introduced plum rewards – a program that charged no fee and rewarded its members points on purchases that they could use toward future discounts. Why? Because Indigo understood the broader value of data and knew the fee required for iRewards limited its ability to understand all of its customers, and therefore marginalized its sales potential.

Ultimately, as Indigo pivoted from book seller to a lifestyle store with a selection of not only books but also toys, jewelry, electronics, fashion accessories and household items, both its free and fee-based programs assumed greater roles. Each now helps the retailer make better-informed decisions that apply not only to novels, but also to assortment, pricing and store optimization.

The changes to plum rewards, to take effect Sept. 3, will usher in features based on such customer feedback. Among them: quarterly bonus events that reward members 10 times the points on their purchases, as well as other bonus point offers. Members also will be able to redeem their points online, in store and via the mobile app.

The rate at which members earn points, however, was reduced, to five points per dollar from 10 points. Indigo said it made the change because members wanted more flexibility in earning and redeeming plum points.

“Members want to be rewarded for their online purchases and they want to see more ways to accelerate their points earnings,” Indigo stated on its FAQ page.

The shift may also be a method of encouraging its dedicated plum members to join its fee-based iRewards program.

Fee or not, emotional loyalty requires relevance

Regardless of Indigo’s strategy, history proves that retail loyalty takes more than providing the customer with an incremental sweetener.

Rather, it requires a commitment to sifting through that customer information – whether it be transactional, from a survey or through social feedback – for the kinds of insights that shape messaging and experiences in ways that are golden, and relevant. Only when the brand experience resonates with the customer on a personal level can the retailer expect to foster an emotional bond.

To achieve that emotional loyalty, a company must engage its customers throughout the experience. This means basing every decision it makes – including those affecting its loyalty program – on what is meaningful to that consumer. Responsible data use is an important part of this task. It will help the retailer understand its best customers’ core interests, assign value to them and then connect with its customers in ways that say, “I know who you are, and I understand your needs.”

Retail loyalty is a combination pack of unit value for the customer and data value for the retailer. Using loyalty as a method for competing on price alone is a limiter. A retailer could fully realize a customer loyalty initiative only when its value extends beyond the program itself and to the ways its data can shape the customer experience – and that includes the decisions implicit in creating that experience.

Fee or no fee – who cares? Unlike Sea-Monkeys and mood rings, retail loyalty programs can evolve with their market. What matters is that the model supports the brand’s purpose, values and ultimately the way it enhances the customer experience.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

August 24, 2015

Death of Points Programs? What the Amazon Prime, Redcard Earn-Back Models Mean

Amazon’s Prime Store Card has some thinking about cash back. It’s got me thinking of marshmallows.

More specifically, it has me asking: What would be a better reward for buying $100 worth of Jet-Puffeds – 100 points, or $5?

Children of the famed Stanford University delayed-gratification tests (which used marshmallows as rewards) may opt for the points, but today’s consumers have major retailers second-guessing. This trend is evidenced in the recent launch of the Amazon Prime Store Card, which instead of awarding points to use tomorrow gives its members 5 percent back on purchases today. Prime Store follows the model of Target’s successful Redcard, which also rewards customers 5 percent back on all purchases.

Combine the two big names, and it could cause ripples across the retail loyalty pool. That Amazon, one of the most competitive merchants in the world, is adopting this format is cause for all retailers to consider whether the percent-back model of loyalty is a feasible alternative to traditional points-based rewards.

Combine the two big names, and it could cause ripples across the retail loyalty pool. That Amazon, one of the most competitive merchants in the world, is adopting this format is cause for all retailers to consider whether the percent-back model of loyalty is a feasible alternative to traditional points-based rewards.

More likely, though, it is just time to reconsider how long we make customers wait. As a culture, we’ve broken the 12-second attention-span barrier – we can give only eight seconds these days, thank you. Having to wait months to earn a loyalty reward is just as good as handing it off to the next of kin. Or, if you are a child waiting for a marshmallow, forever. Not worth it.

The task for retailers with points-based reward programs is to make the process of earning those points more fulfilling. They must make the case why aspirational rewards are more relevant than immediate, incremental ones.

And they need to act fast, because overall loyalty program engagement is low. While the average U.S. household is enrolled in 29 rewards programs, the number of programs in which these consumers remain active is well below half – 12 programs, according to the 2015 . Somewhere after signing up, members are tuning out.

Yet at the same time, nearly half of all retailers – 46 percent – have identified loyalty programs as a top priority, according to a new report by Boston Retail Partners.

Up-front marshmallows work, but…

For those unfamiliar with the Stanford experiments, they were a series of studies through which psychologists tested whether children would choose to receive one marshmallow immediately or be willing to wait a short time and receive two. The overwhelming majority attempted to wait.

In Stanford terms, Amazon and Redcard are offering up-front marshmallows, and based on Redcard’s penetration number, consumers are opting for them.

According to Target’s 2014 annual report, its loyalty credit card penetration rose to 21 percent in 2014 from 13.6 percent in 2012 and 5.9 percent in 2010. Discounts associated with the programs amounted to $943 million, $583 million and $162 million in 2014, 2012 and 2010, respectively.

Similarly, the Amazon Prime Store Card rewards its users 5 percent discounts on their purchases. It’s like a never-expiring, 5 percent-off coupon. For the consumer who charges $2,000 a year, that nets out to $100. In terms of marshmallows, Target’s overall discounts could buy roughly 30 billion, enough to stack to the moon (providing a new meaning to Moon Pie).

This does not, however, mean the traditional, points-based rewards model is failing. Rather, the model may just require some reconsideration of the aspirational rewards, and how long customers should have to wait to receive them.

Aspiring for relevance

As any member of the Kroger Plus Card program could attest, several retailers do deliver timely rewards and often without requiring unusual purchases. A few regular shopping trips to Kroger, for example, could translate to 10 cents or more off a gallon at the pump. Other programs, however, could require members to wait years before earning a $100 reward.

A key distinguisher, it appears, is frequency. Retailers that are typically visited often can feasibly operate a model that rewards often – think Starbucks, Walgreens and PetSmart. They collect more regular data and can better understand their customers.

But there are ways retailers can make aspirational rewards just as relevant as incremental ones.

Focus your analytics: Retailers have access to more data than they know how to use – that is the challenge. By first determining what the brand stands for to its best customers, the company can narrow down the purchase and behavioral data to illuminate what its shoppers expect in return for their loyalty, the kinds of rewards or recognition they value and how often they want to receive them.

Be a regular: That said, retailers should assume their customers want recognition regularly. A well-timed video of the staff saying thank you, or a free sample (or coupon for one) are likely to get the customer back into the store or online. Offers also are an important element of recognition – if they are positioned correctly and reflect what the customer is buying or his or her life stage.

Add a fee: It may sound counter-intuitive, but when the fee supports special, ongoing perks – such as free expedited shipping (as is the case with Amazon Prime) – consumers see immediate value. Nearly half (47%) of Americans believe rewards in fee-based programs are better than rewards in free programs, according to a survey of 1,000 consumers by LoyaltyOne.

Lastly, know how to enjoy the marshmallows. Customer engagement should be the top priority for every merchant – immediately, in the near term and next year.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

August 21, 2015

Personalizing Digital Shopping a Bag at a Time: How Tumi is Enriching Engagement

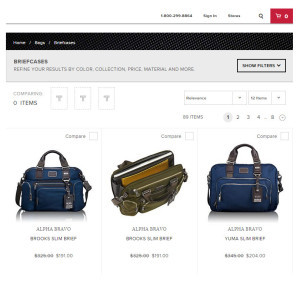

Perhaps the most surprising thing Tumi learned is that men window-shop.

Not on the street, mind you, but online. “The analytics show men are spending time, going through the navigation rather than the search,” said Naveen Gunti, senior director of global e-commerce technology and operations at Tumi Holdings Inc., the worldwide maker of premium luggage. “That is rather surprising to me. I thought, ‘Men don’t do window shopping,’ but I see that happening online. I see them engaging.”

Photo credit: Adobe/Tumi

As the owner of several Tumi luggage pieces, purchased both online and in-store, I myself am a little surprised by this revelation. Do I window-shop online? Whether I do or not, the behavior is one of several discoveries almost a year after the company adopted new in-house tools to optimize its online experience.

The services, through Adobe, provide a combination of interactive visuals and analytics that are helping Tumi get its products online faster while also revealing surprising ways in which its customers shop online.

The result is significantly longer engagement times and expedited entries into new channels, notably mobile. The initiative has also taught Tumi an important lesson about understanding its market, and one that would benefit any retailer: Like that long-ago postcard in the zipper pocket, some of the most valued findings can emerge from unexpected places.

Such behavioral findings could also contribute to higher sales in other channels, notably the store. Almost 90 percent of global consumers (88 percent) have said they use the Internet to research online and purchase offline, according to 2014 research by DigitasLBi. More specific to Tumi – 45 percent of luxury purchases are influenced by what the customer has read or found digitally, according to a 2015 report by WBR Digital.

Sizing up the challenge

Tumi is not a newcomer to online retailing, but the rapid-evolving pace of digital commerce requires pretty much any merchant to view the industry with regularly refreshed eyes.

This was especially the case as Tumi tried to keep up with its own product innovation. The company, which normally offers about 3,000 products, introduces 1,500 new items a year. Every one of those items needs to be photographed, edited and resized, described in detail and loaded to the website.

The trick: Tumi has just three months to do that before the product is in the warehouse.

Rushing the process through its third-party supplier, however, was not so easy a solution. The Tumi brand is synonymous with quality – its bags are known for rugged fabrics, patented closure system, ID locks and aircraft-grade aluminum tubing. Its customers pay a premium because they expect the best, and that experience should begin on the website.

A couple of chintzy images won’t cut it. Waiting to load better visuals, however, meant lost sales opportunities.

Making a case in-house

Tumi decided to take the work in-house. It turned to Adobe for a suite of technologies, which include a web content management system and user analytics.

Among the immediate results, Tumi realized it could load all videos, images (including detailed shots of products both inside and out) and zoom features 30 percent to 40 percent faster. The added capabilities and time freed it to add new features, including an interactive service through which online customers could overlay monograms onto images of luggage and experiment with different colors and font styles.

Other benefits since the launch, in October 2014, include:

Extended engagement: On average, session times increased by 40 percent, indicating customers are spending more time exploring and learning about products. This in turn has led to higher purchase rates, though Gunti cautioned that conversions from shopping to buying are influenced by several factors.

Unexpected taxonomies: Tumi shifted its focus to navigation and narrowed the number of products it lists per category to make it easier for users. “We basically track the journey of the customer,” Gunti said. “How they move back and forth on the site and what they are looking at.” Among the unexpected results was the window-shopping lesson.

Rapid mobile: Another unforeseen finding is that Tumi’s customer base is shifting from desktop to mobile much faster than expected. “We will be focusing more on mobile based on that,” Gunti said. “That’s a huge one for us, at least for the rest of the year.”

Better social sharing: Through Adobe’s social platform service, which is tightly integrated with its analytics, Tumi is able to better manage its social media channels globally. It can, for example, localize various campaigns based on successes – a campaign that excels in North America can be adapted for its UK market.

Packing for the future

With its first full year on the updated platform almost zipped up, Tumi is casting its digital eye on new horizons.

The luggage maker is, for example, working on a portal for its retail partners and distributors. Through it they will have faster access to the latest versions of Tumi’s online visuals and other assets, so they can enrich the brand experience on their own sites. Presently Tumi supplies the images to these parties through burned CDs or file transfers.

Tumi also plans to further personalize the customer experience, based on its analytics, to include individualized recommendations. Once complete, Shopper A, upon visiting the home page, may see an image of the Vapor Lite extended-trip packing case, to complement her Vapor Lite continental carry-on. Shopper B, meanwhile, could see an Alpha Bravo backpack because he had previously shopped the Mission sling.

And who knows? The further personalized recommendations could lead to additional unexpected findings. The more information Tumi collects, the more it learns, and the greater its opportunities for controlling its destiny.

As Gunti put it: “The data collection and the kind of slicing and dicing of information is what I feel is very powerful.”

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

August 17, 2015

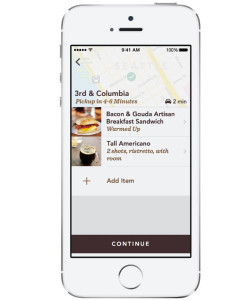

Mobile Order & Pay – the Ultimate Brand Experience (Just Ask Starbucks)

It’s long been said that life is fleeting, and increasingly that includes the interactions that make us loyal.

The best experiences today come not in minutes, not in seconds, but in milliseconds. Consumers demand it, and retailers are scrambling to find newer, more beguiling ways to oblige. In short, saved time is as relevant as personalization.

Photo credit: Starbucks

This is evidenced in a recent story about Starbuck’s digital order-ahead service, called Mobile Order & Pay. With it, a customer can place an Iced Caramel Macchiato order by phone in advance and find the beverage waiting for her when she arrives at the café. The clear message: Make the coffee wait, not the customer.

Increasingly, it seems as if every major brand is investing in similar new forms of digital technology to heighten customer experiences. But let’s face it, these efforts are really just about saving time. In fact, many of today’s shopping apps wrap themselves in the cloak of experience or loyalty when in reality they are simply winding themselves around the demands of the clock. Time is always at the root of these investments. It’s evidenced in Nordstrom’s curbside pickup tests, as well as Amazon and Macy’s same-day delivery trials.

When a brand makes it easy for the customer to get offers, transact, redeem rewards and the like, it is essentially saving the customer time.

In short, relevance is a time saver.

Make time short, see sales grow

This is not to reduce the importance of experience and loyalty. But ultimately if a brand interaction lacks the (reduced) time dimension, then it may be missing the fundamental ingredient that would make technology work for the brand.

Howard Schultz, the CEO of Starbucks, told analysts that his company’s investment in digital technology, including Mobile Order & Pay, has contributed to 4 percent traffic growth in the third quarter. And the program has yet to see full potential: Mobile Order & Pay’s rollout, to 4,000 locations, took place in just the last few weeks of the third quarter.

“Mobile Order & Pay is enabling us to serve more customers more quickly and efficiently and to significantly reduce attrition off the line,” Schultz said. “We are already seeing positive impact on operating results.”

He added that the initiative is contributing to revenue and profit growth in every market it is available, not only because it reduces incidents of consumers walking away from busy stores, but also by increasing purchase options.

Not surprising, then, that mobile payments now represent 20 percent of all Starbuck’s in-store transactions in the United States, more than twice the figure of two years ago. That’s nearly 9 million mobile transactions a week.

Be loyal, earn time

Tying this all together is Starbuck’s reward program, called My Starbucks Rewards, which emerged from an earlier payment-card system. My Starbucks Rewards is now a 10 million-member example of technology working for the brand by saving time.

This is because Starbucks customers need to be reward members to use Mobile Order & Pay and mobile payment – and millions of people are signing up every year. (Note, non-rewards members can still sign up for the Starbucks app, but do not have access to mobile payment features.) Starbucks’ 10.4 million membership number represents a 28 percent increase from one year ago. More than half of those members (6.2 million) are gold tier, making at least 30 purchases in a calendar year.

Save these valuable members an extra five to 10 minutes in a day, and those 30 purchases can become 50. Do the math and that shakes out to an additional 124 million purchases a year. Now consider if those purchases averaged $3 apiece.

That’s almost $375 million, all in return for a simple, time-saving app. But to the consumer, the experience of carrying away that awaiting Skinny Peppermint Mocha, with her name scrawled on the side of the cup, transcends dollars. It carries over to loyal.

August 10, 2015

Committing to Charity with Purpose: The Good, Bad and Ugly of Creating Cause with Effect

Benevolence can be consumer catnip when it comes to brand likeability, but it does not work when its rewards are fleeting, or veiled.

Men’s Wearhouse National Suit Drive (PRNewsFoto/Men’s Wearhouse)

Several retailers have learned this firsthand. Like the child pointing out the emperor’s wardrobe deceit, consumers see through marketing campaigns that are dressed up like charitable events, and history shows they are not so charitable in response. As we head into another busy holiday and back-to-school season, we can expect to see more of such efforts.

Yet several companies have and do pursue cause marketing smartly, as is evidenced by a few recent campaigns detailed in Marketing Daily and elsewhere:

• Men’s Wearhouse recruited Philadelphia Eagles running back DeMarco Murray and National Basketball Association coaches to support its eighth annual National Suit Drive, a campaign that encouraged consumers to donate suits for job hunters in need.

• Macy’s has introduced the Fashion Pass, a $5 “ticket” that earns users storewide discounts and then donates all ticket proceeds to several charities including the Ronald McDonald House and the Children’s Cancer Research Fund

• Penzeys Spices offers its customers coupons for free ground pepper with every $10 purchase, and then for every jar purchased or redeemed it donates one jar of ground pepper to feed people in need. Through Aug. 11 Penzeys is donating two jars and also is asking customers to share places that feed those in need while also supporting good cooking.

• Staples on Aug. 2 launched Teacher Appreciation Week, which increases the percentage that members of Staples Teacher Rewards earn back when they buy school supplies. Through Aug. 8, Staples is offering teachers coupons that earn them 40 percent back on their school purchase, up from the usual 5 percent.

The message of each campaign resonates; the challenge for many is finding a message that aligns with the brand – and strengthens it. Because while cause efforts can polish a company’s image and may make for temporary sales bumps, the proof of their effectiveness is the extent to which they can turn shoppers into advocates.

Charity not a game of chicken

When it comes to cause marketing, the brand experience, from entering the store or website to using the final product, should remind customers of the purposes they want to support. When the brand experience and cause do not line up, or when the company’s product, service or actions simply do not support the cause, we get what is often a charity fail.

One infamous case involved a Walmart food drive that the retailer sponsored before Thanksgiving. The drive was promoted to help the community’s needier residents, but those turned out to include Walmart employees. Regardless of Walmart’s intention, the images of its own workers collecting food donated by other workers made the major corporation look miserly. Its effort ended up emphasizing its low-wage reputation.

For fast-food chicken chain KFC, the fail resulted from using its own products. A Utah franchisee partnered with the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) to prevent childhood diabetes, which is a good cause, except the fundraising required the purchases of soda – specifically, half-gallons of Pepsi. Soda is a major contributor to type 2 diabetes. “Complete your meal with a mega-jug,” the in-store promotions read.

Not specified was that this campaign, and the JDRF, actually supported research into preventing type 1 diabetes, which is not caused by sugary drinks or obesity. It is an important distinction that should not have been overlooked. Regardless, the health risks soda presents to children (especially children drinking a half-gallon of the stuff) is well documented. This effort was plain tone-deaf.

Causes with perfect pitch

Brands have the opportunity to strike the perfect charitable pitch when they choose causes that reinforce the organization’s own mission, services or products. Procter & Gamble, for instance, chooses causes that support its stated purpose to improve the lives of consumers for generations. Customers who participate in its charitable endeavors are reminded of these purposes when they buy P&G products because the messaging and mission are consistent throughout.

Below are a few other lessons unveiled from these effective charitable endeavors:

Build through partners: The Men’s Wearhouse suit-donation campaign, like many good efforts, does not exist in a vacuum. The retailer establishes goals to drum up enthusiasm and identifies the kind of influential partners who could inspire would-be donors. This year, organizers hoped to raise the number of donated suits in the program’s eight years to 1 million from 850,000. Several NBA coaches including Brad Stevens of the Boston Celtics and Frank Vogel of the Indiana Pacers have pledged to donate their own suits. Penzeys, likewise, is essentially partnering with its customers by inviting them to identify recipients of its charity.

Recruit: Macy’s Fashion Pass runs only through mid-August, but the mission of its campaign, like that of Staples, supports a variety of other year-round programs dedicated to core causes. It also makes business sense, which is essential even for charity. By timing fundraising to July and August, Macy’s could attract back-to-school shoppers a little early (September is often a bigger back-to-school sales month). At the same time, the chain is exposing a critically important consumer group – youths – to the needs of these charities.

Make ambassadors: Staples hosts teachers campaigns in recognition of a market segment that struggles annually to meet its needs. (In 2014, Staples partnered with singer Katy Perry and donated $1 million to the classroom-funding group DonorsChoose.org.) By placing itself firmly in the teachers’ corner, Staples is building a community of reciprocal supporters. Similarly, the department store chain Kohl’s, through its “Associates in Action” program, strengthen ties between workers and their communities, as well as their customers. Launched in 2001, the program has attracted more than 1 million worker volunteers at roughly 176,000 local events.

These strategies support brand missions while also improving the companies that stand behind them. In part, they do this by mixing ongoing charitable causes with time-sensitive campaigns that benefit target groups when they most need it – without pretense.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

August 3, 2015

Curating for Transgender Customers: How 5 Retailers Size Up

If I were to rank the need for retailers to address the demands of the transgender community, I would give it an 11.

That’s the hot figure that arose during a recent shoe-shopping trip with my daughter, who wears a size 11. There among the limited stacks of shoes in her size, and her exasperated claims of what a chore shoe shopping had become, we overheard a conversation between two transgender women. They were trying on several of the same pairs of shoes, and were quite happy by the choices. My daughter’s limited selection represented, to them, expanding opportunities in the human experience.

These opportunities should continue. The Institute for Transgender Economic Advancement estimates 1% of the population, or 3.2 million people, is transgender. That’s slightly smaller than the population of Connecticut, and larger than that of Puerto Rico. However, while it is a small percentage of the total U.S. population, the figure will likely increase as more people accept transgender men and women as part of our community.

These opportunities should continue. The Institute for Transgender Economic Advancement estimates 1% of the population, or 3.2 million people, is transgender. That’s slightly smaller than the population of Connecticut, and larger than that of Puerto Rico. However, while it is a small percentage of the total U.S. population, the figure will likely increase as more people accept transgender men and women as part of our community.

Included in that acceptance will be retailers, and the sooner they recognize the importance of their role serving this market group, the greater will be their long-term benefits.

A niche is more than a pet project

I’ve written in this space before about the potential for merchants to increase sales and foster loyalty through data use that goes beyond typical demographics. By mixing behavioral analytics that indicate activities and interests as well as purchasing preferences, retailers can understand the why behind customer actions and parlay that into fodder for creative segmenting. They can identify select groups of shoppers, even within the transgender community, who should be catered to in different ways.

Put another way, while the customer may prefer wearing heels sometimes, she also could be an avid basketball player and hunter.

If there ever was an event that underscored retail’s need to meet the demands of niched market segments, the transgender community represents it. And we should not let size fool us, because even the smallest of markets can be lucrative. Case in point: The U.S. sale of organic foods rose 3,400 percent from 1990 to 2014, to $35 billion, representing the fastest-growing lifestyle trend, according to Food Safety News.

Trailblazers in transgender retail

The transgender community can represent equal opportunity for retailers, and a number of merchants and major designers are recognizing this. It may be a little while before transgender merchandising is displayed prominently in small-town department stores, but let’s hope not. Meantime, mainline merchants can take some lessons from these transgender trailblazers:

Chrysalis Lingerie: This lingerie brand was created specifically to address the tastes and needs of transgender women through a combination of luxury and functionality. Here Chrysalis has made the important decision to not sacrifice practicality at the cost of pretty. The garments are both, because their wearers require and want both. Being a niche market does not mean one should compromise on style or performance.

Make Up For Ever: The professional cosmetics retailer does not market specifically to transgender men and women, but it has hired transgender model Andreja Pejic to be its face, making it among the first major beauty campaigns fronted by a transgender model. By doing this, Make Up For Ever makes clear it understands the many differences in who its customers are and who they aspire to be, and it serves them.

Girls Will Be: This custom-design online shop dubs itself “Your headquarters for girl clothes without the girly.” The fit runs between tight and boxy and the imagery breaks stereotypes, providing young girls a choice between flowery outfits that do not appeal and boys’ outfits that may not fit right. Though not specifically designed for transgender children, the site is clear in its goal to empower young girls to just be who they are.

Nik Kacy: This online footwear merchant, named for founder and designer Nik Kacy, offers beautifully made and classically styled shoes that come in sizes that fit those who want masculine shoes but do not fall within the industry standards in size. Nik Kacy is expanding into women’s shoes as well. Its slogan, “Walk your way,” challenges the norm of the shoe industry, and will likely launch new forms of sole searching.

Macy’s: The grand lady of department stores has achieved the status of trans-friendly because it puts buyers in the aisles to hear firsthand what its shoppers want. This was illustrated years ago when CEO Terry Lundgren explained how Macy’s buyers in Chicago learned the stores there did not carry enough size 11 women’s shoes to meet demand. Buyers on the ground responded with complete displays of size 11 shoes, in 20 styles, which sold six and seven pair at a time. Macy’s might not have questioned who the buyers were, but it clearly found a niche.

Had my daughter and I been shopping in Chicago instead of New York, she may have had better luck shoe shopping. But we did both luck out in a valuable lesson: Expanding opportunities to enrich human experiences often exist right before our eyes. We just need to see them through the eyes of others.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

July 29, 2015

Making the Grade: 4 Ways Retailers Can Cash In On Back-to-School

Recent projections of 2015 back-to-school spending may require retailers learn some new math – the kind wherein one plus one equals numerous marketing outcomes and teens themselves factor into the equation.

Research by the National Retail Federation indicates that average family spending on back-to-school clothing, electronics and other needs will decline to $630.36 this year, from $669.28 in 2014. These lackluster predictions do not necessarily mean retailers should lose out on sales, however. They may just need to reconsider the needs of the back-to-school shopper and who is influencing his and her preferences.

In part, this requires niching. Rather than dialing out to capture a broad segment of consumers, retailers should consider sharpening their market focus to identify and then meet the demands of smaller school-going segments. Some students play sports, others are artists and many are involved in charities and sustainable activities. Some have after-school jobs. And some do all of the above.

Doing this means recognizing that the event of back-to-school shopping has changed. It’s no longer a mother-child outing shaped by retailers. Now the students themselves have become fashion influencers through a crop of well-watched blogs including Evita Nuh’s The Créme de la Crop, Freddy Rodriguez’s Blue Perk and Callie Reiff’s site.

One review of these influencers and it is clear that captivating these select groups of students requires the creativity to rethink the assortment and merchandising in ways that are relevant. It also takes looking well beyond the obvious – putting lunchboxes and acrylic paints alongside dresses may look incongruous, for example, but to a young fashionista, it makes sense.

Playground for profits

While the strategy of focusing on behavioral niches and youthful influencers may sound elementary, for larger merchants such finessed execution can be arduous, particularly when customer segments vary from store to store. There are, thankfully, ways to cover all the bases.

Target, for example, is testing a program for parents called School List Assist, which features a select assortment of common school products but presents them to meet lifestyle preferences, not so much school needs.

Among the student market segments it identifies are “philanthropic-minded students,” “DIY enthusiasts” (or creative types), and “eco-minded students.” Alongside each of the seven niche groups identified, Target suggests specific products, such as Yoobi school supplies (which donates a portion of sales to charity) and backpacks made of recycled materials.

Photo credit: Target

Target essentially just rejiggered how it markets, first identifying specific student proclivities and then promoting products that suit each. Here are four other ways to build the basket through insights and inspirations:

Extracurricular activities: Fashion retailers with rewards programs can use them to invite members to affordable but attractive RSVP events in their stores. These can range from mother-daughter lunches to fashion shows to photo opportunities that allow students to model their new wardrobes against chosen backdrops. These events turn school shopping into occasions that translate to long-held memories and encourage unplanned purchases that serve as mementos.

Make the grade: Curbside pickup, personal teen shoppers who prepare wardrobes in advance and laptops already preloaded with the latest software deliver needed convenience for relatively small fees. But these small fees add up. Retailers can use their data to identify higher-spending shoppers who are more likely to pay a little extra for such conveniences, and then market these features specifically to them.

Cross faculties: School activities filter into all aspects of a student’s lifestyle, and likewise merchandise can be factored into all school functions. Retailers can promote certain snacks alongside athletic clothing, market special pieces of jewelry to commemorate an important year and give new purpose to everyday items through merchandising and the help of youthful influencers. Enlisting key fashion bloggers or stylish associates (perhaps personal teen shoppers) can materialize new experiences with existing merchandise. Retailers can further rely on these young influencers to understand what is hot or bubbling up. If locker accessories represent a category ripe for expansion, retailers can find ways to play it up.

Don’t miss the bell: Retailers should task store managers with being aware of major school events, from big football games to food drives to themed dances. Prepared in advance, they can build displays centered on these themes that tell local students the retailer is part of their world. In addition, retailers could avail themselves of student-related events hosted by other major, and beloved, brands. In honor of Van’s Custom Culture contest, for instance, mass merchants can add acrylics, sequins and other decorative items alongside the canvas sneakers.

The above ideas require not just some new math, but also a combination of art and science. This is customary in mastering the meaning of customer data as well as new media and the increasingly influential role the target market – students – plays now that they can create their own media platforms.

Executed well, this approach can be applied across a range of retail events, from back-to-school to whatever the numbers add up to.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

July 27, 2015

Shopping Mall of Tomorrow: How Westfield, Walmart are Stripping Convention (Part 4)

Just as hemlines go up and down, retail history is patterned after the influences of its past and present. To envision the mall of tomorrow, we would benefit to first reflect on what was fashionable a decade ago.

Consumer behavior expert Paco Underhill tried to capture it in the last chapter of his 2004 book “Call of the Mall.” In it, he explores how traditional enclosed malls had been repurposed into recreational complexes, government centers and newly conceived high-end, open-air malls.

“We’re bored,” he writes of the Baby Boomers’ attitude toward shopping centers. “Teenagers and children are still excited by the mall, but it’s all still new to them, isn’t it?”

And that was before the word “Millennial” entered the lexicon of retail angst.

Today, consumerism has evolved from mega-malls to power centers to online shopping. However, while the figurative hemlines of shopping centers have changed, the fabric across which this history stretches contains one common thread: The desire for a connection. This basic consumer need exists regardless of age group or ethnicity.

Today, as retailers balance the physical and technological needs of Baby Boomers and Millennials, from online shopping to power centers, the future of shopping formats appears to hinge on its destination, both real and virtual.

This is my fourth and final in a series of stories that examines how digital technology and its rapid adaptation, across all age groups, is challenging retailers to identify and serve an increasingly fluid customer. Last week we looked at how Ikea is testing a variety of digital concepts to bridge the online and in-store experiences. This week I will explore the future of the shopping mall format and how two major players are exploring ways to preserve the shared, relationship-based shopping experiences people still crave.

Westfield’s future mall

Retailers watching their financials need only know a single figure: One.

That is the number of super-regional shopping malls built from 2011 to 2014, according to the International Council of Shopping Centers. Yet the overall number of centers built in that time has advanced by almost 850, to 114,957 from 114,096. This is thanks to the expansion of more conveniently located strip centers and other open-air type malls with tenants that range from high-end shoe stores and supermarkets to day spas and dentist offices.

Not all developers are convinced the enclosed mall is out of fashion, however. Westfield Group, one of the world’s largest owners of shopping malls, has been investing in new digital strategies to overhaul the mall. Among its tested concepts are “click-and-collect” services through which shoppers order online and pick up in the store; digital food ordering and large in-mall screens featuring hundreds of products mall-goers can finger-swipe through and purchase via digital device.

The developer’s Westfield World Trade Center in New York, to open later in 2015, will combine some of these innovations with the ultimate in destination. The center is actually a transportation hub through which 200,000 commuters are expected to pass daily. Before arriving, visitors can use a dedicated mall app to search for and choose the items they’d like to purchase, and then upon arriving they receive personalized digital greetings and can use the app to map their shopping journeys.

“I think the mall of the future is really a personalized experience,” Kevin McKenzie, global chief digital officer at Westfield Group, told the Business of Fashion in January. “And the way that we are going to get to that is through technology. No question.”

The Walmart Downsizing Effect

On the other side of the mall and technology spectrum, seemingly, would be Walmart. However the world’s largest retailer, like shopping centers, is also seeking new destinations and has been opening in traditional malls for some time. In 2011, for example, it opened two small-format Walmart.com stores in Southern California malls to showcase its online efforts while also stocking some essential items.

Walmart at the same time has been taking a page from the open-air-mall playbook and maneuvering into densely populated areas through its Neighborhood Market store, a model that averages 42,000 square feet.

Walmart at the same time has been taking a page from the open-air-mall playbook and maneuvering into densely populated areas through its Neighborhood Market store, a model that averages 42,000 square feet.

As of Jan 31, Walmart operated roughly 640 Neighborhood Market and other smaller-format stores, according to its annual report. It opened 235 of them in 2014 and in the fiscal first quarter of 2015, it opened 25.

Yet despite their smaller size, these stores generate significant sales volumes. Sales at Marketplace stores opened at least a year rose 7.9 percent in the first quarter, far outpacing the 1.1 percent growth rate of all Walmart stores. According to Market Realist, Walmart has targeted $17 billion in revenue through the smaller-format locations by fiscal 2017.

“Customers continue to see the benefit of Neighborhood Markets to meet their everyday needs, including convenient access to services such as drive-through pharmacies and fuel stations,” Greg Foran, president and CEO of Walmart U.S., told analysts in a quarterly earnings call.

Hard-wired shopping trends

The takeaway by these experiments is that despite our many changes, the axis upon which all retail spins is unchanging, as long as humans are hard-wired to congregate. Sure, Amazon.com and Google may put detergent, socks and cereal into our hands through a single click, but that hardly passes as a shared experience. There is room, in our variable lives, for both types of shopping.

Consumer behavior expert Paco Underhill, who in 2004 declared the mall boring, wrote in a recent Wall Street Journal column that as the consumption baton passes from Baby Boomers to Millennials, the shopping relationship will be reformulated. The result, he wrote, is that malls are becoming “alls.”

“We will go to the mall to be entertained and live our lives; to recreate, not just to shop.”

But hasn’t it always been that way? The future of the mall – as a lumbering dinosaur or a runway success – will depend on how it manifests the destination. But make no mistake, the nondescript, cavernous architecture upon which the industry was built is no longer cutting it.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com, where Bryan serves as a retail contributor. You can view the original story here.

Bryan Pearson's Blog

- Bryan Pearson's profile

- 4 followers