Candice Ransom's Blog, page 7

March 30, 2015

Why I (Still) Write for Children, Part II

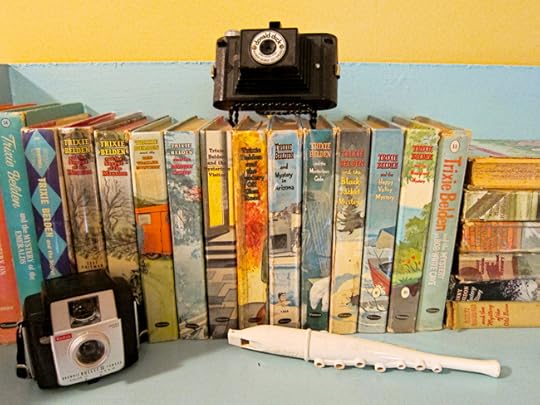

I became a writer because of one book. I was home sick from school one day in fourth grade. Mama let me build a reading cave in the living room, a bedspread draped over the card table, furnished with a quilt and my bed pillow. Bored, I investigated the bookcase behind the red glider rocker. It contained Doubleday Book Club titles, such as Unto These Hills and the intriguing-sounding (but actually dull) Panther’s Moon.

Wedged between the grown-up books was a book my older sister had left behind: Trixie Belden and the Mysterious Visitor. I carried it into my reading cave as Candice Farris, nine-year-old-with-a-cold. When I came out, I was Candice Farris, future-writer-of-books. I’d already been writing stories a few years, and reading everything I could get my hands on. This book made me a writer.

Why this particular book? For one thing, the characters are regular kids. Trixie is a thirteen-year-old girl who loves horses and hates chores and most school work. But she isn’t dumb. She figures out mysteries that stump grown-ups.

In Mysterious Visitor, I learned about dominant and recessive genes. Trixie: “If we knew that Mrs. Lynch’s parents both had blue eyes we’d know for sure that Uncle Monty was an impostor. It’s the Mendelian theory of heredity.” Brian, her brother: “Blue is recessive, so blue-eyed parents can’t have a brown-eyed child.”

This tidbit sent me flying to the bathroom mirror. My mother’s eyes were chocolate brown. My father’s were blue. Mine weren’t either but a light goldy brown. What did that mean? Was there an impostor in my family?

I loved the fact Trixie lives in the country in a modest house (though she has a rich best friend): “The Manor House . . . formed the western boundary of the Beldens’ Crabapple Farm, which nestled down in a hollow. Honey’s home was luxurious, but Trixie preferred the little white frame house where she lived with her three brothers and their parents.”

Like many girls, I identified with Trixie; I wanted to be Trixie. The closest thing was to write stories like that. Trixie had adventures, sometimes even dangerous ones, but she always went home to Crabapple Farm.

Just as I once spent my days in my tree house, in the woods, or down at the creek, I always returned home to the familiar yellow light spilling from the kitchen window, the smell of fried chicken and biscuits.

As explained in The Scientist in the Crib, young children “are torn between the safety of a grown-up embrace and the irresistible drive to explore. A toddler in the park seems attached to his mother by an invisible bungee cord: he ventures out to explore and then, in sudden panic, races back to the safe haven, only to venture forth again some few minutes later. Even as grown-ups, it seems a part of the human condition to be perpetually torn between home and away.”

Adventure—going away—is one reason I still write for children. Home is the second reason. Home, the real place we come back to after a day of adventure. And home the idea, the part that lives inside us no matter our actual address. Because I didn’t always have a home. The nine-year-old me remembered that and was figuring out a way to protect the four-year-old me.

In TalkTalk, E.L. Konigsburg states: “When a person writes he returns home—to childhood—and in that sense, home is a time as well as a place. It is often a small, dark place where we were often frightened. Childhood as home was not always comfortable, and it is often not fun to return to, but it is a place we all carry around inside of us, and it must be looked into and occasionally aired out. It is the place where we were the most raw, most unvarnished, most uncluttered with the packaging of civilization.”

Home is the single theme that ties almost all of my books together. Having a home, not having a home, leaving home . . . wanting to go back home. Lately, the kids I write about don’t live in Starbucks-studded suburbs. I’m more drawn to kids who live in gritty reality. Trailers, motels, homeless shelters, “piled-in” with relatives (as I was). Trips to Family Dollar with Meemaw, Sunday and Wednesday church, working in the garden.

Last night, I half-woke with the sense that I was someone else. No, not someone else, but my child-self. For brief seconds, I was in touch with her again. Unsettled feelings whirled about her. Emotions churned, growing Wonderland-like bigger or smaller. How did I manage those all thoughts and fears when I was nine?

The problems of grown-ups, E.L. Konigsburg believes, are definite, while children deal with “vague problems . . . fears and uncertainties.” The hardest job we have as writers for children is “to make concrete words out of those vague, pervading anxieties.”

As a kid, I escaped vague and not-so-vague anxieties through books like Trixie Belden and the Mysterious Visitor. Trixie had problems, too, but they were neatly contained within cardboard covers. When the mystery was solved, she went home to Crabapple Farm. I read for that feeling of home-away-home satisfaction.

Away and home. There and Back Again. Those are the main reasons I still write for children. It’s why I leave the clutter of civilization and return to my childhood, brave that storm of emotions, and, if I’m very lucky, stumble upon the rare joy of learning something new about the world.

Whether it’s 2015 or 1961, kids want to be Trixie Belden or Bilbo Baggins. They will always need to break away, explore, get in trouble, figure things out for themselves. And they will always need to go home again, to the single room, the trailer, the aunt’s basement, the Manor House on the hill, the little white frame house nestled in a hollow.

March 23, 2015

Why I (Still) Write for Children, Part I

A little over a month ago, I was editing chapter seven of a chapter book I’d been working on, on and off, for five years. I set my pen down. The book was dead. It had been on life support the last six months, but I could not pull it through the knothole.

This was a first for me. To quit on a book before I’d finished the second draft. I’d reluctantly let projects go after multiple drastic revisions, multiple submissions, and many restless nights. But despite all the changes to the plot, the addition and subtraction of characters, the shift from third person to first person and back to third again, despite convincing myself this was the first in a four-book series that was important, the book was deader than a nit in a blizzard.

I didn’t care about my character. The story was an uphill slog. And if it was a slog for me, I couldn’t imagine any reader taking a shine to this book, much less an editor signing me up for a four-book series. It was a difficult decision to make, but I put the project in the drawer with relief, not regret.

Then I had to figure out what to do next.

Over the years, people have asked me why I don’t write for adults. Lately, I sense they are serious and not just wondering when I’ll be able to shed my training wheels and go for a real spin. And honestly, when I stand in front of the cluttered children’s section of Barnes and Noble, I wonder the same thing myself. Why am I still writing for children?

I can spout the usual answers: because I’ve been doing this for nearly 35 years. Because I’ve wanted to do it since I was fifteen. Because I don’t know how to do anything else.

But as my 63rd birthday looms, and the field of children’s books grows harder to stay alive in, maybe I need to rethink my chosen career. Maybe there was a deeper reason why that chapter book croaked on me. It’s a question I’ve been pondering for weeks.

Yesterday morning I walked outside with my husband, out into a chilly March start to a day that promised later warmth, out into the drumming of a downy woodpecker and high-crowned budding of the sweet gum, and I said, “I should be in my tree house.” It was an automatic reaction that seeped out from under 53 years of scabbed over events, work, and the dailiness that comprises our grown-up lives.

At age ten, my tree house was where you’d find me every weekend morning until school let out, and then every morning all summer long. I got up as the day unfurled and hurled myself into it.

Last night as I was drifting off to sleep, I climbed up into my tree house again, remembering how it was built in one day by my stepfather and my oldest cousin. I was afraid of heights but I wanted a tree house more than anything. My stepfather built the platform on posts against an oak tree. A shingled roof slanted over the walls, three windows, and narrow doorway. Best of all, he built a sturdy, shallow-stepped staircase with safety rails on both sides.

My stepfather carried up that staircase and through the kid-sized doorway my sister’s old vanity. My mother cut up a pink shower curtain to hang at the windows. I brought up comic books and my bird guide and binoculars.

My tree house became my base camp, the place where I began each day, figuring how to spend the hours as I pleased. Annie Dillard experienced that freedom as well, and recounts her singular moment in An American Childhood: “I had essentially been had been handed my own life . . . My days were my own to plan and fill.”

And so were mine. I was alone much of the time, but seldom lonely. I had library books to read and stories to write, birds to watch, the encyclopedia of the wide world to study. I explored, learned, had small adventures. When my cousins came, I took them with me.

Yesterday warmed to 64 degrees. Kids in our cul-de-sac stayed outside all afternoon, bouncing balls, riding all manner of wheeled things up and down the court, yelling, claiming they were It, declaring out of bounds. I’ve been watching them for years and notice a pattern. Their play seems tethered to structure: vehicles, balls, rules. It’s good they’re outside at all, but back yards go ignored in favor of pavement.

We live in a fairly rural county, yet our neighborhood kids are locked into the routines of suburban kids everywhere: soccer, music lessons, church clubs, swim team. Mothers tell me their driving schedules and I want to lie down in a dark room. When, I wonder, do kids explore, learn things not taught in school or on the Internet, have small adventures?

Young Annie Dillard was given a rock collection, three grocery bags full. An old man had collected the rocks over his lifetime, died, and the paper boy wound up with the collection, which he gave to Annie. She cataloged and labeled the rocks until she “knew them by sight: that favorite dry red cinnabar, those Lake Erie ruby granites and flintstones, big chunks of pale oolite, dark wavy serpentine, gneiss, tourmaline, Apache tears, all of them.”

As she worked, she wondered about the old man:

Maybe he hadn’t died after all. Maybe he’d simply escaped underground. He cracked open Pittsburgh like a geode . . . He visited the underground corridors where spinel crystals twinned underfoot, and blue cubes of galena cut his hands, and carnelian nodules hung wet overhead among pale octahedrons of fluorite, among frost agates and moonstones, red jasper, blue lazulite, stubs of garnet, black chert. Of course he hadn’t come back. Who would?

My tree house is one reason I still write for children. Through my books, I want kids to have a base camp, a place to launch small adventures. I want them to be inspired to go outside, crack open their world, discover the treasures beneath their feet, and maybe—oh, how I hope—take back a few hours of their days.

There is time enough for schedules and computer monitors–years and years of it, in fact. Go, I want to beg kids today, go now. Before it’s too late.

March 16, 2015

Atticus: Status Update

When we left off a few months ago, the kindly old man and woman who adopted Atticus were wondering when their “little kitten” would settle down. The old man says the cat is calmer than he was. There are actual whole minutes when the cat just sits. However, the old woman, who stays with Atticus all the livelong day, knows better.

This is her office on a typical day.

This is the innocent perpetrator.

Atticus is a “carrier.” He carries things in his mouth, usually things that don’t belong to him. This Staples bag contained supplies when Atticus made off with it.

Once when the old woman was working in her office one evening, she heard odd noises coming up the stairs—the cat’s usual stampede (he still doesn’t walk) accompanied with a rattle, rattle, rattle. He trotted into her office dragging a full-sized bag of popcorn (already popped). He had stolen it off the kitchen counter, carried it through the downstairs rooms, up the stairs, down the hall, and into her office. She figured he wanted her to open the popcorn and put a movie on for him. His choice: “Aristocats.” Her choice: “That Darn Cat.”

Actually Atticus has no problem opening things. He hauled a bag of dried split peas off the counter, chewed a hole in the bag and ate some dried split peas. He still eats anything not studded with spikes or marked with a skull and crossbones. Oatmeal. Russell Stover chocolate caramel eggs. Scrambled eggs with hot sauce. Lettuce.

And he still gets into everything. Everything.

It wouldn’t be so bad if he wasn’t so mean. He’s so mean he can’t stand his own self.

He’s so mean he bites door hinges and faucets.

If meanness could be boxed it would look like this.

Atticus is also clever. How many cats could yank off the tablecloth and leave the Sunday Washington Post still in its exact spot?

The old woman, who gets grayer and more wrinkled and shorter every day, is thinking of hiring him out as a magician’s assistant. Or sending him out to work on a garbage truck.

She misses the old days when he’d tucker himself out and slept a few winks. The photo at the top of this post is dated December 9. That’s the ONLY time she and the kindly old man have ever seen the cat with his eyes closed.

He sleeps when they are out of the house (every chance they get–they fight over who goes to the grocery store). One day the old woman will snap a picture of dozing Atticus. She has a better chance of capturing a shot of the Loch Ness monster. In fact, she’d gladly trade the Loch Ness monster for Atticus. Nessie, at least, has settled down.

February 23, 2015

Footprints on the Porch

Wegman’s was Armageddon. I went in with one woefully inadequate reusable shopping bag and met a wall of people at the check out. Fueled by news of Boston’s blizzards and YouTube views of Yeti helping dig them out, everyone in Fredericksburg had been called to the barricades. I pushed through denuded aisles, thankful we didn’t need toilet paper, getting necessities like People magazine and Pepperidge Farm Golden Layer Cake.

Driving home, I fretted over my book project, which wasn’t going at all well. The weather report had everyone in a tear and everything in the chilly air seemed out of whack. We were all focused on ourselves, on surviving this storm which by no means would be epic even by Virginia standards.

As I unloaded groceries, I heard crows making a terrible racket down the street near the wooded area. Their harsh cawing had a tribunal quality. (Poet Louis Jenkins said crows “have a limited vocabulary, like someone who swears constantly”).

The piercing kee-kee of a red-tailed hawk punctuated the crows’ shouts. A blue jay added his two cents’ worth to the melee. I had to see what was going on. If a hawk had been injured, the crows could mob him. Instead I stumbled on an amazing scene.

On the ground two red-tailed hawks squared off in the “mantling” posture, wings fanned open. It took me a few seconds to realize they were fighting, most likely over territory. Another hawk fluttered nearby and a fourth flew in. The crows carried on higher in the trees. The fighters gripped each others’ legs with their talons, as two wrestlers might clutch arms above the wrists, panting and terrible-eyed.

The crow crowd seemed to be taking sides and laying bets. The other two hawks could have been seconds in an old-fashioned duel. And the blue jay reported the proceedings in the excitable tone of an announcer at a boxing match.

I approached as close as allowed. At last the hawks flew off, the crows scattered, and the blue jay shut up. I walked over to the fight ring. The only sign of a scuffle were two breast feathers netted in the underbrush. I hurried home, by then truly freezing, but also feeling somehow privileged and cleansed.

A few hours later, a chickenfeed snow began to fall. Small dry flakes quickly drifted over the ground where so much had been at stake a short while ago. Through the window, I watched from the warm safety of my home as the snow disguised the familiar world. I wished I could bury my faltering book project under the whiteness.

In his book Secrets of the Universe: Essays on Family, Community, Spirit, and Place, Scott Russell Sanders advises writers “…to free themselves from human enclosures, and go outside to study the green world . . . if we are meant to survive, we must look outward from the charmed circle of our own works, to the stupendous theater where our tiny, brief play goes on.”

Later still, when it was dark and bitter cold and snow was still coming down, I looked out on the porch and saw tracks. Cat pawprints. I knew with certainty that this was no neighbor cat making casual rounds. Not in this weather.

My husband filled a plate with cat food and put it on the porch. Then we waited until a shadow separated itself from the swirling night and hunkered over the plate. My worries over a book project seemed as petty as people squabbling over a case of bottled water.

Hawks will fight for the right to hunt and stray cats will search for food and shelter in the wider story of real survival. I remind myself to step off my insignificant stage and gaze out into the stupendous theater. I might learn something from players different from me, no less important.

January 12, 2015

Nutshells and Mosquitoes’ Wings

When my life is seriously off-track, my default position is to haul freight. Maybe it’s because I live in Children’s Book Land where the temptation (and reality) to run away is attractive to every kid at one time or another and I’ve never outgrown the tendency.

In my early twenties I was in a situation I couldn’t extricate myself from easily. I drove home for the weekend whenever I could. I slept in my old bedroom. My mother cooked my favorites. I shot the breeze with my stepfather in his woodworking shop. I took my mother antiquing. At the end of the weekend, I could face that situation a little better.

After I was married, we lived three miles from my parent’s house and I visited often. But if I wanted to, I could run away to that house, sleep in my old bedroom, have fried squash and pie-dough roll-ups for supper.

Then my parents died and my old bedroom was gone. I still found myself wanting to run away. I want to go home, I sobbed to my husband once. And where is that, he asked. I squeezed my eyes shut and remembered the Homeplace in Shenandoah County, where my mother was from. I could go there. Just get in the car and drive over the mountains to the Valley. I’d get a motel room and—but the image dissipated like a mirage.

Thomas Wolfe warned us we can’t go home again. But sometimes I’d still long to climb in my truck and drive west, just drive and drive until I found a spot to stop and rest.

My latest running-away spell came in December. The year was nearly over, I told my husband, and I hadn’t written what I’d wanted to write. Where had the time gone? It seemed I sat in my office every day, yet had little to show.

Always sensitive to my needs, he suggested I go somewhere to fill the well. Expand my horizons so I wouldn’t feel boxed-in. Yes! I agreed. I could run away to a week-long workshop in some place warm! Don’t wait till spring, he urged. Find something happening in January. It was pretty late to get into a conference, but he scoured the Net.

He found a writing retreat in Florence, Italy, a workshop in Key West, and another in St. Petersburg, Florida. Italy was out of the question. The Key West workshop had me foaming at the mouth because Lee Smith was teaching fiction, but not only was it full, the wait list was full. Eckerd College Writer’s in Paradise workshop was still taking applications for two more days. Florida in January! Paradise, indeed.

You couldn’t just pony up the tuition, you had to turn in a good-sized sample of your project and be accepted. I didn’t have a project, really. I had sort of an idea and one chapter of a middle-grade novel. But the Gulf-side campus was so pretty and the faculty so good, I spent those two days working on my submission.

Meanwhile, my husband was figuring the logistics. How would I get there? Where would I stay? It was too far to drive (900 miles). I would have to take two, maybe even three planes each way. The on-site hotel was probably already booked. I could stay elsewhere but I’d have to rent a car. Surprisingly, no meals were included.

When I sent in my application, I learned I’d be notified December 24. The week-long conference began January 17. I thought about all those plane reservations I’d have to make in a very short time. I thought about the hassle of changing planes, renting a car. I thought about what I’d do with my coat.

And then I thought about being away from home. My home. At last, after living in this house nearly twenty years, and being married nearly thirty-six years, I realized that where I lived with my husband was home. Not a childhood home that has been gone for thirty years. Not some mythical Homeplace. My place, my home, was right under my feet.

I can stop running. If I feel boxed-in, it’s because I let myself be tossed off-course. If I need to enlarge my vistas, I only have to drive a few miles to quit squinting.

As Thoreau wrote in Walden, “Let us spend one day as deliberately as Nature, and not be thrown off the track by every nutshell and mosquito’s wing that falls on the rails.”

I signed up for two online courses, one on short-form memoir, the other on nature writing. They will be a nice break from children’s writing, cheaper than flying anywhere and I can sleep in my own bed. On pretty days, I’ll pack a lunch and drive to a quiet, nearly-empty library in rural King George County, where I will work, deliberately.

I start those classes today. If I write anything decent, I’ll post it here (Hallelujah, you’re thinking, something else on this blog besides her infernal whining!).

It’s a new year. Shall we crunch right over those nutshells? And blow those mosquitoes’ wings out of our way?

January 2, 2015

The Twirlies

This has been a year of Twirlies. This is my term for the impetuous thoughts and notions that ricochet in my head, often arriving in that liminal space between sleep and waking.

People with mood disorders can be struck with “flight of ideas” or “grandiose thoughts,” both of which are severe symptoms, but the Twirlies are much milder. So mild they seem possible. Reasonable. Really good ideas, even, and in my case, usually book-related. The problem is that they are not always feasible. And I have too many of them.

2014 started off-balance. I wanted desperately to get back to work after two solid years of dealing with medical issues, other people’s and mine. And so I began vigorously cranking out new ideas. I’ve always been very good at this. I’ve been known to dream book ideas and even dream stories, complete with printed text. It’s not restful sleep.

Being a writer and having the Twirlies seem to be part and parcel of a creative life. Ideas are ideas, however they are delivered. But the Twirlies are different—an enormous waste of time and sometimes hard to come down from.

So what exactly are Twirlies? I can remember a few from 2007, a year I was exhausted and stressed from too many projects, travel, and writing my master’s thesis. I thought about doing a book about Mark Twain when he visited the Jamestown 200th or 300th anniversary. I ran that idea by my thesis adviser, a Twain scholar. An entire book about Twain’s brief and mostly insignificant trip?

The worst Twirly of that period, the one that embarrasses me even today, was deciding to make a scrapbook of Margaret McElderry’s life. Margaret McElderry was the last of the original children’s book editors. By 2007, she had retired from her imprint.

I raced to tell my husband, the idea glittering in my mind. I’d do this wonderful thing for an editor I’d admired my entire career! My husband listened carefully and told me that while this was a “good idea,” it would be hard to make work. Why would this editor let a total stranger be privy to her private photographs and documents? I’d go to New York, I argued. I’d show her my scrapbooks and she’d be thrilled to have me make one for her.

Sometimes I get the Twirlies when I need to feel engaged with the world, craving a bigger life than I have.

Last month, I decided I would volunteer at an animal refuge 30 miles away, one that keeps cats, dogs, and even livestock that can’t be adopted. I offered to photograph and write a book about the place, which meant I’d require free access. I even filled out waivers. But when I was told I wouldn’t be permitted to interact with the animals—unsafe for both the animals and me—I fell out of the mood. I didn’t want to wash cat bowls.

The Twirlies are often aided and abetted by the Internet. After the refuge fiasco, I found the blog of someone doing an interesting project. I decided I would write to this person, but I had too much to say for an email. I spent an entire weekend tracking down the address. I planned to write this person a long letter, include part of my own writing, detail all my own interests, and even send along some childhood drawings I’d photocopied. Mercifully, I didn’t follow through, which is generally what happens with Twirlies.

There were more Twirlies this year, minor ones like impulse-spending and writing too-long, too-confessional letters, and not-so-minor ones like impulsively making promises I couldn’t keep.

Then last month Winchester left us and the Twirlies sank deep, like koi in an iced-over pond. I felt fragile, glass-like. I became very, very quiet. No Twirlies could save my cat. No Twirlies would save me.

The Twirlies are, I believe, the result of not being involved in meaningful work. A restless mind reaches out, searches, and latches onto shimmering ideas. Despite my longing for a meaningful project, the Twirlies drive a wedge between me and my work.

I needed to figure out what the Twirlies were, what they were doing to me, and how to control them. I sat down and put together my own self-help book. Seriously. I listed my issues and my goals. And then I researched each problem and came up with solutions. I’ve read a hundred self-help books over the years. The information in them would make sense, but I’d forget it.

This self-help book is tailored to my personal problems. It has inspirational quotes, and quoted material from books, articles, and the Internet, distilled into short chapters. It has solutions I can implement immediately, and longer-term solutions I can work toward.

There is a separate chapter called “Twirlies.” I had to analyze this particular issue on my own. I figured that when my mood goes in either direction, I’m more susceptible to the Twirlies. I spend money. I stay on the Internet. I’m too chatty. And I’m bombarded with ideas. But ideas are also part of my own creativity. How can I tell the difference?

My solution: Sit on the idea. Don’t feed it with the Internet. If the idea is valid and good, it will persist and grow. If it’s not, it’ll wither and be forgotten.

On my desk is the red binder called Daily Plan 2015. 40 pages, single-spaced. It seems almost pathetic to put together my own self-help book, but I’m glad I did. It’s one Twirly idea that is the most beneficial way to start the New Year.

December 7, 2014

Winchester’s Story

He came to us the summer of 2003, skinny as a bed slat. He slept on our porch and of course we began feeding him. In September, he showed up with a serious wound over his eye. I thought for about two seconds what to do. We already had Xenia and Mulan in the house. They hated each other so much we kept them on separate floors. What the hell. Off to the vet we went.

Winchester was underweight and the worst tom cat ever. He was a lover, not a fighter. He’d lose every single fight, and nearly lost his eye. I had him fixed up, and fixed. But then the vet called and said he tested positive for feline leukemia, a highly contagious, deadly disease in cats. Put him down or keep him, and keep him completely separated from the other cats. That was the choice.

He was only a year old, a gangly teenager of a cat and I couldn’t end his life so soon. He moved into my office with me. He was allowed out after Xenia and Mulan were put in separate rooms. I’m not sure how I stayed sane. Xenia knew he was in my office and dug and scratched at the door (ruined our carpet). Winchester knew when she was locked in a room and would deliberately taunt her. They fought through the doors.

With regular food, Winchester put on weight and grew into his large frame. And grew. And grew. We bought a carpeted platform cat tree with rope scratching areas. Winchester shredded it so viciously that someone once came into my office and started looking nervously around for the ocelot they were sure we had. After ten months in my office, which I ran out of some days because he was driving me nuts, we had him retested for feline leukemia. He tested negative.

The happiest day of my life was the day I let Winchester have free run of the house. It didn’t last long. He had Mulan to deal with. Mulan brooked no foolishness from an eager young male who only wanted to play. After months, she finally let him stay in the same room with her. Winchester adored her.

At suppertime, Mulan would sit by my husband’s chair (he rescued her and she worshipped him). Winchester stood behind Mulan at a respectful distance. If she happened to miss a crumb, he might be lucky enough to snag it. He often leaned forward gingerly and smelled her fluffy tail, or sniffed her ear. Yes, he was in love. Soon Mulan tolerated him enough to let him sleep on the ottoman while she slept in the big chair.

It was evident pretty quick that Winchester was smart. He fetched. He learned to open doors by turning the doorknobs. He learned the meanings of “Get down,” “Quit it,” “Stop,” “Off,” and “Behave,” but chose to ignore them. He was funny. The female cats were too dignified to carry on the way Winchester did. That cat could cut a shine.

For the first time ever, I wrote one of my own cats into a book. Ten books, to be exact. Winchester was a bit player in my series Time Spies. (He also appeared in Scrapbooking Just for You.) I started a blog to help promote Time Spies called Ellsworth’s Journal. I had the stuffed elephant (also in the books), but Ellsworth needed someone to interact with. In stepped Winchester with a sign, “Will Work for Food.” He was hired.

Unlike the other cats, Winchester didn’t mind being dressed up and photographed. Well, mostly he didn’t. He was incredibly patient while I set up the shot, moved props, tried hats and shirts and sweaters on him. Treats was his main motivator. He was fool for Party Mix.

Winchester’s finest role, Scrooge.

In 2009 Winchester developed an upper respiratory ailment. He was put on allergy medication. Because of his chronically stuffed-up nose, he didn’t feel like dressing up. So I retired Ellsworth’s Journal and started this blog. Our household began to change.

Ellsworth as Marley’s ghost,

Winchester as Ebeneezer

Mulan went first. Xenia followed her a few years later (bitter to the very end—she never stopped trying to kill Winchester). Persnickety, who showed up on our porch in 2004 and also despised Winchester (they fought through the window screens), left us last spring. Finally Winchester became Top Cat.

No longer did he have to gaze longingly at Persnickety’s heaping bowls of food when I took them out to her. No longer did he have to hear, “Not yours,” surely the saddest words in the world to a cat that lived to eat and had to watch his weight.

We never needed a clock. Winchester was in our face at six in the morning for breakfast. He started lobbying for lunch at 10:30, but I made him wait until 11:30. Supper was at 5:00. The minute Daddy came home, Winchester was begging for treats. At 7:00, he wanted more kibble. At 8:30, he got a few more crumbs before bed.

If anyone put a toenail in the kitchen, Winchester magically appeared. He even knew what I fixing. If I was using the cutting board for vegetables, he wouldn’t bother getting up from his nap, though he was probably thinking, “Chicken soup.” Before I even took the chicken out of refrigerator, there he was.

He was no hunter, unlike the three females. A mouse could run across the room and Winchester would have just looked at it. Sometimes I opened the door to see if he’d go outside. Sometimes I wanted him to go outside and give me some peace. What? he seemed to say. And leave all this?

Of all our cats, Winchester was the funniest, brightest, most exasperating, handsomest (he was quite proud of those long white whiskers), best sport, and my best friend. He was only with us twelve years, though it seems longer because he had such a big personality. I still remember the summer day he showed up on our porch and climbed into my lap. He chose me.

Acute pancreatitis struck him two days after Thanksgiving. Five days later, he was gone. There has never been an emptier, quieter house.

Nighty-night, sweet baby boy. There will never be another cat like you.

November 27, 2014

Happy Thanksgiving!

Not our yard! I rake leaves, gumballs, and hickory nuts starting in September without the least inclination to make word patterns. This person does this every year.

November 24, 2014

Why I’ll Never Be Annie Dillard, Part II

Still clinging to my need to lead a “bigger life,” I read Robert MacFarlane’s advice on becoming a naturalist. “Become a monomaniac. Study one species, one acre of ground, one tree, until it has become a foreign country to you (fabulously strange) or one of the things you understand best in the whole world (fabulously familiar).”

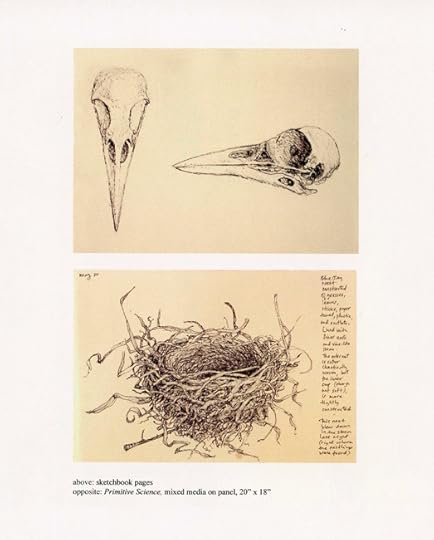

My Sketchbook 1999

What one thing could I study until it became fabulously strange or fabulously familiar? By November the natural world has pretty much tucked itself away for the winter. Then I remembered the spider in the corner of my garage door. I’ve been walking under that spider web every day for months. She was the fourth generation to live there—her mother, grandmother, great-grandmother all spun webs in that same corner.

I would keep a journal, illustrated with photos. Sure, I was getting a late start, Yet I remembered a lot, like how this year’s spider started spinning in April and how her webs weren’t very good at first, sort of like the summer I tried to teach myself to tat, buying a tatting shuttle and crochet thread at Rohr’s Five and Ten, and churning out a long grayish greasy knotted string that looked nothing like lace.

How one day the spider wove the web with a big hole in the center, like a portal, and I wished I could squeeze myself through it into a new life.

How I never, ever saw her, not even early mornings as I often surprised her mother putting the finishing touches on that day’s web. How this spider left the corner, leaving me fretting our garage wasn’t good enough and she’d found a better corner. And how she came back, suddenly, as if that other corner wasn’t so hot after all.

How once I saw a fly struggling in her web and stood there, wondering if I should free the fly so he could live, or let him stay so she could eat. I decided not to interfere.

How back in September I saw her tending her egg sac and knew her time was close.

By November she’d stopped weaving. And she stayed in the doorway, in plain sight. Nights were chilly. I figured she would die soon. When she did, I would take her down and identify her (after four years of watching these spiders, I still wasn’t sure of the species). I’d lay her crumpled body on a square of cotton and study her.

Then I would write an essay about her modest, noble life, something Annie Dillard-ish, a piece akin to E.B. White’s “Death of a Pig.” “Death of a Spider” doesn’t carry the same import, but this spider and I have a relationship and it’s worth examining.

The next morning I went out through the garage for the paper and looked up, as always. She lay still and crumpled in the doorway. I reached up one finger and poked her.

She dropped down indignantly on a silk thread, most definitely not dead! But the other spiders in the garage and bushes were gone. Why was she still here? The nights grew colder. I continued to check on her. Sometimes when I poked her, she extended a foreleg, all the energy she could muster. It wouldn’t be long now . . .

One morning I noticed a new web sparkling in the sun! When I looked up at her, she looked down at me, as if to say, Don’t write me off yet, sister.

Then the temperature plunged to 18 degrees. Ice skinned the birdbath. In her corner, the spider’s legs were drawn up. This was it, mostly likely.

I touched her gently. She plummeted on her silk thread to the code box. We were now eye-to-eye. I ran inside for my camera. By the time I got back, she’d folded up a bit. I touched her again to make her straighten out but she zipped up, clearly put out.

If the spider were keeping a field journal on me, it would read:

Here comes that turkey of a human again. Why does she keep prodding me? Doesn’t she know I bite? My bite is “unpleasant” but harmless. Heh heh. I will leave this world in my own good time. Meanwhile, back off.

My photos are terrible, but I got a good look at her. She’s a European garden spider, also called a cross spider after the markings on her back.

I kept a journal for one week on the spider. My handwriting is too big—I can’t do that tiny printing I used to—and my entries are too wordy. And then I stopped. It seemed enough to notice her, greet her every day, and hoped she noticed me [Who could miss that looming hulk gawking at me?].

Thoreau walked every afternoon. He took notes in a field notebook and made very simple sketches and maps. The next morning he entered his notes into a journal. Some of those entries were revised and polished into essays or lectures. He recorded simple things so that people would love the landscape as he did.

While at Hollins College, Annie Dillard wrote a thesis on Thoreau and Walden. After graduation, she spent a year or so at Tinker Creek, walking and observing. “I live by a creek, Tinker Creek,” she wrote, “in a valley in Virginia’s Blue Ridge. It’s a good place to live; there’s a lot to think about.”

I lag far behind Annie Dillard and trail so far behind Thoreau he isn’t even in sight, but I keep a close eye on simple things because I must, even if I don’t record my observations in lovely field journals.

Thoreau once said: “The forcible writer stands bodily behind his words with his experience. He does not make books out of books, but has been there in person.”

This morning, days away from the end of November, a gorgeous web stretched defiantly across my spider’s corner. A tiny insect, fatally attracted by the light we keep on all night, was snared in the silk. She will eat that insect, along with the web, tonight. [Bon appetit!]

And I will try to make books from being there in person, in that fabulously strange and familiar place where there is plenty to think about.

November 23, 2014

Why I’ll Never Be Annie Dillard, Part I

Every so often I’m overtaken by what I call Thoreau Notions. I want to go live someplace by myself, hoe my row of beans, let mice scamper over my shoes, take long walks in the winter and think about the stars.

The truth? My idea of roughing it is no room service. Mice are fine outside but definitely not running over my feet. I can’t stand to be cold for even a second and in the winter I’m in pj’s with a book and a cat by eight o’clock, the heck with the stars.

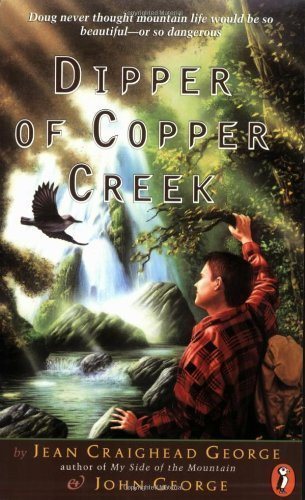

Yet I’ve been drawn to nature writing since, at age nine, I read Dipper of Copper Creek by John and Jean George (Jean Craighead George actually wrote those early books; her ornithologist husband hogged the credit but she got the Newbery in the end). I read all the books by the Georges, and anything about rocks and birds and animals.

When I was 22, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek hit the bookstores. I read it, amazed someone so young could write so deeply about nature. Annie Dillard (a Hollins graduate) was 28—only six years older than me—when her book was published. The next year the book took the Pulitzer for nonfiction.

Dillard began keeping a journal in 1970 while she was living in the Virginia mountains. Pilgrim is based on those journals. Walden is based on Thoreau’s journals. Clearly the path to becoming a nature writer is to keep a journal. Better, an illustrated field journal.

Who hasn’t longed to keep a detailed illustrated journal like Hannah Hinchman? I bought this set back in 1990—a handbook and a blank book to start your own journal. The pages of mine are still pristine. Yet the urge to create an illustrated journal crops up alongside those Thoreau Notions. In 1999, I started a nature sketchbook. It’s all of four pages with such pithy observations as these:

From Blue Ridge Mountains

A few summers ago I saw an exhibition by artist/naturalist Suzanne Stryk. Her mixed media art combines field journal entries, paintings, and natural elements like mole skulls. In the exhibition catalog I learned Stryk visits the wildest spots in Virginia. She paddled through Dragon Run Swamp, a place only accessible by canoe, at night to see the red eyes of spiders.

Nature writers and artists put themselves out there. Maybe it was time I did, too. Which is why last weekend I announced at breakfast that I need to do “something bigger” in my life besides write one book after another. I rattled on about us visiting wild places so I could photograph them and keep a field journal and write important essays that would be published in Orion, alongside the latest treatise by Elizabeth Kolbert.

Nature writers and artists put themselves out there. Maybe it was time I did, too. Which is why last weekend I announced at breakfast that I need to do “something bigger” in my life besides write one book after another. I rattled on about us visiting wild places so I could photograph them and keep a field journal and write important essays that would be published in Orion, alongside the latest treatise by Elizabeth Kolbert.

My husband set his coffee cup down when I told him about canoeing through Dragon Run Swamp to see the red eyes of spiders. He knew who would be paddling the canoe and said we would not be visiting any swamp at night.

I sighed. But I still want to be like Annie Dillard and Thoreau and Suzanne Stryk and Hannah Hinchman. How? Apparently it’s not easy for anyone, even those committed to a natural life.

Hannah Hinchman says:

Sometimes I think the fierce girl I was is lost forever. Is it because I no longer have the Peter Pan-like power simply to believe? Breaking through to the wellspring requires a certain kind of cultivation now. It is an intentional act of recovering innocence. A great weight of sadness accumulates over the years, building up like travertine hot-spring deposits on the original bedrock of wonder. Enchantment is burdened by disappointment, unfulfilled promises, exhaustion, cruelty, the shackles of habit.

If anybody is bound by the shackles of habit and weighted by unfulfilled promises, it’s me. I should be glad I can go home to my little house and feed the cat and fix supper, even if I cook while reading (not a cookbook). I should be glad I’m able to write books about kids who aren’t burdened by disappointment or exhaustion.

May be it is time to let go of my Thoreau Notions once and for all.

Continued in Why I’ll Never Be Annie Dillard, Part II