Why I’ll Never Be Annie Dillard, Part II

Still clinging to my need to lead a “bigger life,” I read Robert MacFarlane’s advice on becoming a naturalist. “Become a monomaniac. Study one species, one acre of ground, one tree, until it has become a foreign country to you (fabulously strange) or one of the things you understand best in the whole world (fabulously familiar).”

My Sketchbook 1999

What one thing could I study until it became fabulously strange or fabulously familiar? By November the natural world has pretty much tucked itself away for the winter. Then I remembered the spider in the corner of my garage door. I’ve been walking under that spider web every day for months. She was the fourth generation to live there—her mother, grandmother, great-grandmother all spun webs in that same corner.

I would keep a journal, illustrated with photos. Sure, I was getting a late start, Yet I remembered a lot, like how this year’s spider started spinning in April and how her webs weren’t very good at first, sort of like the summer I tried to teach myself to tat, buying a tatting shuttle and crochet thread at Rohr’s Five and Ten, and churning out a long grayish greasy knotted string that looked nothing like lace.

How one day the spider wove the web with a big hole in the center, like a portal, and I wished I could squeeze myself through it into a new life.

How I never, ever saw her, not even early mornings as I often surprised her mother putting the finishing touches on that day’s web. How this spider left the corner, leaving me fretting our garage wasn’t good enough and she’d found a better corner. And how she came back, suddenly, as if that other corner wasn’t so hot after all.

How once I saw a fly struggling in her web and stood there, wondering if I should free the fly so he could live, or let him stay so she could eat. I decided not to interfere.

How back in September I saw her tending her egg sac and knew her time was close.

By November she’d stopped weaving. And she stayed in the doorway, in plain sight. Nights were chilly. I figured she would die soon. When she did, I would take her down and identify her (after four years of watching these spiders, I still wasn’t sure of the species). I’d lay her crumpled body on a square of cotton and study her.

Then I would write an essay about her modest, noble life, something Annie Dillard-ish, a piece akin to E.B. White’s “Death of a Pig.” “Death of a Spider” doesn’t carry the same import, but this spider and I have a relationship and it’s worth examining.

The next morning I went out through the garage for the paper and looked up, as always. She lay still and crumpled in the doorway. I reached up one finger and poked her.

She dropped down indignantly on a silk thread, most definitely not dead! But the other spiders in the garage and bushes were gone. Why was she still here? The nights grew colder. I continued to check on her. Sometimes when I poked her, she extended a foreleg, all the energy she could muster. It wouldn’t be long now . . .

One morning I noticed a new web sparkling in the sun! When I looked up at her, she looked down at me, as if to say, Don’t write me off yet, sister.

Then the temperature plunged to 18 degrees. Ice skinned the birdbath. In her corner, the spider’s legs were drawn up. This was it, mostly likely.

I touched her gently. She plummeted on her silk thread to the code box. We were now eye-to-eye. I ran inside for my camera. By the time I got back, she’d folded up a bit. I touched her again to make her straighten out but she zipped up, clearly put out.

If the spider were keeping a field journal on me, it would read:

Here comes that turkey of a human again. Why does she keep prodding me? Doesn’t she know I bite? My bite is “unpleasant” but harmless. Heh heh. I will leave this world in my own good time. Meanwhile, back off.

My photos are terrible, but I got a good look at her. She’s a European garden spider, also called a cross spider after the markings on her back.

I kept a journal for one week on the spider. My handwriting is too big—I can’t do that tiny printing I used to—and my entries are too wordy. And then I stopped. It seemed enough to notice her, greet her every day, and hoped she noticed me [Who could miss that looming hulk gawking at me?].

Thoreau walked every afternoon. He took notes in a field notebook and made very simple sketches and maps. The next morning he entered his notes into a journal. Some of those entries were revised and polished into essays or lectures. He recorded simple things so that people would love the landscape as he did.

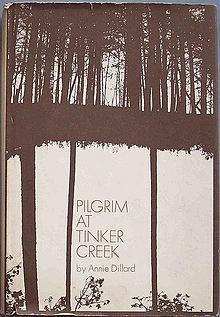

While at Hollins College, Annie Dillard wrote a thesis on Thoreau and Walden. After graduation, she spent a year or so at Tinker Creek, walking and observing. “I live by a creek, Tinker Creek,” she wrote, “in a valley in Virginia’s Blue Ridge. It’s a good place to live; there’s a lot to think about.”

I lag far behind Annie Dillard and trail so far behind Thoreau he isn’t even in sight, but I keep a close eye on simple things because I must, even if I don’t record my observations in lovely field journals.

Thoreau once said: “The forcible writer stands bodily behind his words with his experience. He does not make books out of books, but has been there in person.”

This morning, days away from the end of November, a gorgeous web stretched defiantly across my spider’s corner. A tiny insect, fatally attracted by the light we keep on all night, was snared in the silk. She will eat that insect, along with the web, tonight. [Bon appetit!]

And I will try to make books from being there in person, in that fabulously strange and familiar place where there is plenty to think about.