Why I (Still) Write for Children, Part II

I became a writer because of one book. I was home sick from school one day in fourth grade. Mama let me build a reading cave in the living room, a bedspread draped over the card table, furnished with a quilt and my bed pillow. Bored, I investigated the bookcase behind the red glider rocker. It contained Doubleday Book Club titles, such as Unto These Hills and the intriguing-sounding (but actually dull) Panther’s Moon.

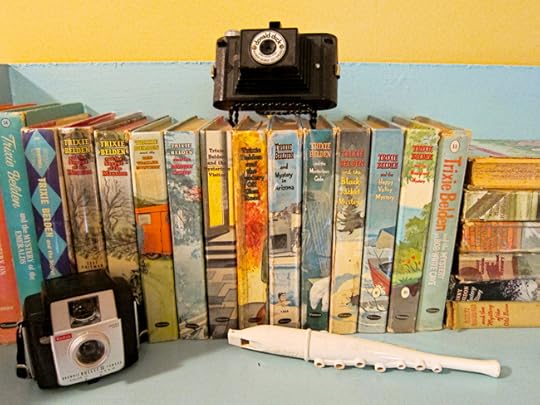

Wedged between the grown-up books was a book my older sister had left behind: Trixie Belden and the Mysterious Visitor. I carried it into my reading cave as Candice Farris, nine-year-old-with-a-cold. When I came out, I was Candice Farris, future-writer-of-books. I’d already been writing stories a few years, and reading everything I could get my hands on. This book made me a writer.

Why this particular book? For one thing, the characters are regular kids. Trixie is a thirteen-year-old girl who loves horses and hates chores and most school work. But she isn’t dumb. She figures out mysteries that stump grown-ups.

In Mysterious Visitor, I learned about dominant and recessive genes. Trixie: “If we knew that Mrs. Lynch’s parents both had blue eyes we’d know for sure that Uncle Monty was an impostor. It’s the Mendelian theory of heredity.” Brian, her brother: “Blue is recessive, so blue-eyed parents can’t have a brown-eyed child.”

This tidbit sent me flying to the bathroom mirror. My mother’s eyes were chocolate brown. My father’s were blue. Mine weren’t either but a light goldy brown. What did that mean? Was there an impostor in my family?

I loved the fact Trixie lives in the country in a modest house (though she has a rich best friend): “The Manor House . . . formed the western boundary of the Beldens’ Crabapple Farm, which nestled down in a hollow. Honey’s home was luxurious, but Trixie preferred the little white frame house where she lived with her three brothers and their parents.”

Like many girls, I identified with Trixie; I wanted to be Trixie. The closest thing was to write stories like that. Trixie had adventures, sometimes even dangerous ones, but she always went home to Crabapple Farm.

Just as I once spent my days in my tree house, in the woods, or down at the creek, I always returned home to the familiar yellow light spilling from the kitchen window, the smell of fried chicken and biscuits.

As explained in The Scientist in the Crib, young children “are torn between the safety of a grown-up embrace and the irresistible drive to explore. A toddler in the park seems attached to his mother by an invisible bungee cord: he ventures out to explore and then, in sudden panic, races back to the safe haven, only to venture forth again some few minutes later. Even as grown-ups, it seems a part of the human condition to be perpetually torn between home and away.”

Adventure—going away—is one reason I still write for children. Home is the second reason. Home, the real place we come back to after a day of adventure. And home the idea, the part that lives inside us no matter our actual address. Because I didn’t always have a home. The nine-year-old me remembered that and was figuring out a way to protect the four-year-old me.

In TalkTalk, E.L. Konigsburg states: “When a person writes he returns home—to childhood—and in that sense, home is a time as well as a place. It is often a small, dark place where we were often frightened. Childhood as home was not always comfortable, and it is often not fun to return to, but it is a place we all carry around inside of us, and it must be looked into and occasionally aired out. It is the place where we were the most raw, most unvarnished, most uncluttered with the packaging of civilization.”

Home is the single theme that ties almost all of my books together. Having a home, not having a home, leaving home . . . wanting to go back home. Lately, the kids I write about don’t live in Starbucks-studded suburbs. I’m more drawn to kids who live in gritty reality. Trailers, motels, homeless shelters, “piled-in” with relatives (as I was). Trips to Family Dollar with Meemaw, Sunday and Wednesday church, working in the garden.

Last night, I half-woke with the sense that I was someone else. No, not someone else, but my child-self. For brief seconds, I was in touch with her again. Unsettled feelings whirled about her. Emotions churned, growing Wonderland-like bigger or smaller. How did I manage those all thoughts and fears when I was nine?

The problems of grown-ups, E.L. Konigsburg believes, are definite, while children deal with “vague problems . . . fears and uncertainties.” The hardest job we have as writers for children is “to make concrete words out of those vague, pervading anxieties.”

As a kid, I escaped vague and not-so-vague anxieties through books like Trixie Belden and the Mysterious Visitor. Trixie had problems, too, but they were neatly contained within cardboard covers. When the mystery was solved, she went home to Crabapple Farm. I read for that feeling of home-away-home satisfaction.

Away and home. There and Back Again. Those are the main reasons I still write for children. It’s why I leave the clutter of civilization and return to my childhood, brave that storm of emotions, and, if I’m very lucky, stumble upon the rare joy of learning something new about the world.

Whether it’s 2015 or 1961, kids want to be Trixie Belden or Bilbo Baggins. They will always need to break away, explore, get in trouble, figure things out for themselves. And they will always need to go home again, to the single room, the trailer, the aunt’s basement, the Manor House on the hill, the little white frame house nestled in a hollow.