Candice Ransom's Blog, page 8

November 9, 2014

Memberships in the World

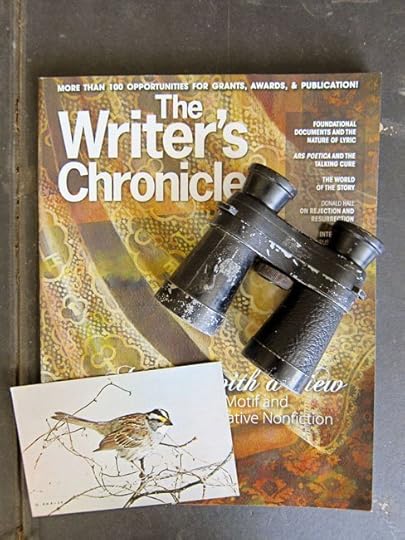

The morning of our field trip, I began reading an article in the new issue of The Writer’s Chronicle, called “The World of the Story” by Eileen Pollack. I had no business reading anything—I had to be at Donna’s house by 7:00. But the piece drew me in with Pollack’s notion of setting in a story:

A more interesting way to conceive of setting is to imagine the world—or

worlds—a story’s characters inhabit, the cultures that produced them, the communities within which they do—and do not—feel at home.

I skimmed the rest before hurtling out the door. My friend Donna and I were taking the commuter train to D.C. to visit museums. The night before I set out my clothes, like I did back in elementary school, and packed a light bag (apparently filled with uranium ingots judging by how heavy it felt as the day went on).

Like kids on a school trip, we brought cameras, snacks, and enough conversation topics to keep us talking nonstop. Our day was an open adventure! Poor Donna didn’t suspect my real mission was to see the passenger pigeon exhibit that marked the hundredth anniversary of the death of Martha, the last surviving passenger pigeon.

I’d been to the Museum of Natural History several times, but for some reason when Donna and I entered the rotunda and saw that emblematic elephant, I was once again eleven years old, awestruck.

That summer my Uncle Benny decided to take me and my cousin Eugene to the Smithsonian. Benny always drove at least 50 miles over the speed limit. We sailed across the 14th Street Bridge, the Potomac below a gray-blue blur. I was going to see birds!

As a country girl, I loved all nature, but especially birds. The museum was my first dose of real science. As we approached the heavy brass-plated doors, I realized I was entering a new world. It had a sheen, this world, of people casually museum-hopping, of buses trundling along the city streets and kids playing on the grassy Mall like it was their own private back yard.

Eugene sped off to the dinosaurs. I headed for the Hall of Birds, entering yet another world. Science nature was very different from half-wild-in-the-woods nature. Eugene and my uncle covered the entire museum while I was still entranced in the Hall of Birds. In the gift shop, I bought a ten-cent postcard of a white-throated sparrow. Then it was time to hydroplane back across the 14th Street Bridge, leave city world behind.

Donna and I snapped pictures of the elephant. My focus was on the small birds “flitting” around the elephant’s habitat. I’d never noticed them before. Were those little birds there when I was eleven?

We went downstairs. The Hall of Birds with the elaborate dioramas I remembered had been reduced to three display cases of birds in the D.C. region. Around the corner we found the passenger pigeon exhibit. I gazed at Martha, still dead after all these years, her world vanished entirely because it collided with ours.

The museum cafeteria teemed with high school students. I watched them, comfortable in their own sheen, and was reminded of my own high school days when I was, as Pollack said in her piece, “embarrassingly unlike the kids into whose houses [I] longingly peered while watching TV.” I was like those little birds orbiting the elephant in the rotunda.

Suddenly I was seventeen again. My senior English teacher, who detected a spark in me, pressed John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman into my hands. The book bored me but I didn’t want her to think I was too dumb to understand it. I kept her copy so long she had to ask for it back and that made me feel even worse.

Miss Boyd knew I had no money for college, but her sorority sponsored students for scholarships. She invited me to her apartment for tea one Sunday afternoon to meet her sorority sisters.

I can still picture Miss Boyd’s apartment, small but nicely furnished, a maple desk, bookcases. No felt cardinal magnets clung to her refrigerator, no cardboard autumn scene hung above her sofa.

I recall what I wore, a dropped-waist floral print my mother made me in tenth grade. I have hazy impressions of well-dressed women, tea being poured, appetizers that weren’t of the cream-cheese-on-Ritz-crackers variety being passed. I felt drab as a sparrow, too shy to speak, too clumsy to sip from a china cup.

But my memories aren’t real.

I never went to Miss Boyd’s for tea. I couldn’t. Her world—one of literature and tea and sorority sisters—was too different from mine. I worried about going so much I imagined I actually did go.

In “The World of the Story,” Pollack says: “Most of us grow up assuming that everyone lives the way we live. Once we realize that the culture to which we belong is considered marginal or exotic, we often grow ashamed.”

I made some lame excuse about not going to the tea, miserable because I’d disappointed the only teacher who had ever cared about me, who offered a step up out of my world. I did make it out, and eventually became a card-carrying member in several other worlds, but it wasn’t easy, doing it my way. As Pollack eloquently states at the end of her piece:

We endure exiles and migrations. We cross from room to room, from house to house, from neighborhood to neighborhood, from school to school, from job to job, from family to family . . . all the while experiencing the pull and tug of conflicting rituals and beliefs. If mapping such journeys isn’t an essential part of writing, I don’t know what is.

I have the ability to shift between different communities. I speak the language, am skilled in the rituals, and share those experiences with my readers.

Donna and I hit three museums on our trip. Aiming for the earliest train back, we were swept along by the tide of commuters. “We’re just like city girls!” Donna said. And we were. We’d successfully navigated that world and could return whenever we wanted.

We chatted all the way to the station in Fredericksburg, daylight when we left, dark when we arrived. Donna’s husband was waiting for us. We climbed into the van, still talking, city air still clinging to us, glad to be home.

October 26, 2014

Becoming Cinderella’s Pumpkin

Of all the characters in Cinderella, I identify most with the pumpkin, if a pumpkin can be called a character. Yes, the dress is a big step up from rags and the glass slippers are how-fast-can-you-run-‘cuz-I’m-taking-them worthy. But the coach!

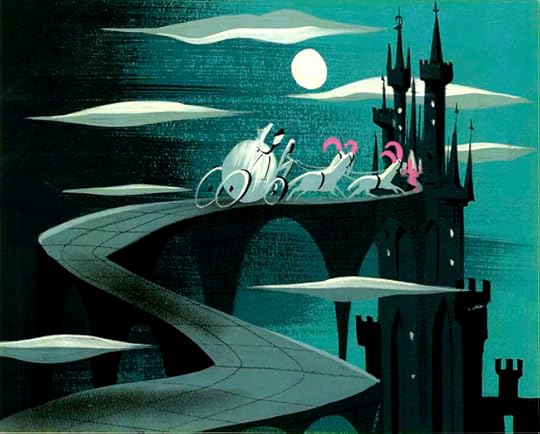

Concept art by Mary Blair for Disney’s “Cinderella”

Imagine being a pumpkin slumbering in the moonlight when suddenly you are magicked right out of the patch. You grow and grow, your pulpy insides forming golden struts and leather seats and steely springs. Your seed-coins are exchanged for a pearly coachman’s perch and silver wheels.

You are wide awake and purpose-driven.

These last few years I’ve felt like a pumpkin dozing beneath broad green leaves. I could hear crows caw overhead and feel the warmth of the sun on my skin and the tunnelings of earthworms beneath my thick shell. I was present on this planet, but I couldn’t move. It wasn’t always this way.

Once upon a time I was Cinderella’s coach. I raced through the night, writing book after book, giving talk after talk, piling up page after page. I had to hurry but the clock struck midnight anyway.

Things happened, things beyond my pumpkin-coach control. I realized I was no longer sleek and swift, silver and gold, shiny and bright. I slowed down until soon I was back in the patch, fastened to a vine, earth-bound. Just another pumpkin.

Do pumpkins get a second chance? Do they get picked to be the coach again?

Maybe. In April I sold a book that I’ve only mentioned to a few friends. It’s a Step into Reading for Random House called Pumpkin Day. Why didn’t I announce it to the world? Because I still felt soft and unsure inside my shell.

And this month, I left the patch to participate in writer’s conferences. I gave workshops on picture books, chapter books, middle grade fiction, and nonfiction. I delivered the keynote speech at one conference. As the first adviser of the Mid-Atlantic SCBWI region, I cut a 35th anniversary cake with Steve Mooser, one of the founders of that organization.

I swapped my work-rags for lacy scarves, tulle-trimmed jackets, and funky cowboy boots (no glass slipper would fit over my bunions). I swept through a ballroom to the theme of “Superman.” I talked. I listened. I hugged old friends. I met new people. I learned new ways of working. I was reminded of what’s important.

I woke up, felt that old familiar drive.

Pumpkin month is nearly over. My conference glow won’t disappear like Cinderella’s coach at midnight. The swirling energy will linger because I’m going to implement what I learned, remember what’s important, and call those faces to mind when I feel alone in the patch.

To celebrate Pumpkin Day (out fall 2015), I picked a big round pumpkin and brought it home. It’s dozing on our front porch, dreaming of the time it once raced through the dark night, all gold and silver, swift and determined, bright with purpose. Wondering about second chances.

It could happen.

October 2, 2014

How Much Do You Want It Back?

“Look at that!” my husband exclaimed one morning. Through the breakfast room window we saw a saucer-sized spider web that seemed to float in midair, a shimmery wheel backlit by the sun. Perfectly round. Perfectly woven with tight spiraling radials.

My husband ran for his camera. By the time I reached the back yard with my own camera, the jeweled light had vanished and the web trembled in a rising breeze. The tiny blue-and-green orchard weaver sitting in the center had anchored her creation precariously, four long silk threads stretched from a high tree branch down to the grass.

As I watched, the stiff wind folded the web once, twice, then into nothingness. The spider raced along one of the guidelines to safety. All her work . . . gone in an instant. I wondered why she built her web in such an unlikely place. Not even up long enough to snare a single insect.

Maybe that wasn’t the spider’s intent.

When I unplugged my Internet computer September first, I felt relief and freedom. But in my head, I heard the refrain of the Trace Adkins song, “You’re gonna miss this. You’re gonna waaant this back.”

Twice before at the end of my Online Shutdowns, I did want it back. I’d eagerly put my computer together and hurry to log in. Not long after, I’d spiral downward into the usual net of distraction and unhappiness.

This time within days of the Shutdown, the crippling agitation and lack of focus faded. I went to the library to check my email. The rest of the day I worked and read.

I read about smart phone addiction. Did you know people check their phones an average of 100 times a day? One man admitted his phone is his “truest companion.”

I read about the lack of time. Someone wrote to the Wall Street Journal: How can I enjoy life more? Every year, time seems to go by faster. The columnist responded that time seems to pass more slowly when we were kids because we experienced things that were new and unique. As we get older, our lives drop into a routine. The columnist concluded: Maybe we need some new app that will encourage us to try out new experiences, point out things we’ve never seen, and suggest places we’ve never been to make our lives more varied. Tongue in cheek? Maybe.

I read that children spend less than 40 minutes a week in their back yards. Parents use their back yards less than 15 minutes a week. Despite Memorial Day displays of new porch furniture, grills, and swing sets, people still spend most of their time indoors.

Two weeks into my Online Shutdown, I felt a seismic shift beyond the shedding of my fractured, distracted skin. Random memories came at odd moments: the lift of anticipation when handed new textbooks on the first day of school, the feeling of being in this world one summer evening when my cousins and I played tag, the sense of being on this planet as I lay watching bats, the earth pressed firmly against my shoulderblades.

I had become my old self again. Someone I had not seen in years. The stiff wind that rattled thoughts and stirred too many emotions settled down. In my head, all was quiet.

Oh, yes, I wanted this back.

But how could I keep it? I can’t live in a bubble. When I first announced going offline, people said, “I want to do this too!” and I thought, Why don’t you? Then I realized I only had to unplug my Internet computer. I don’t have an iPad or an iPhone or i-anything. To follow my example, people would have to give up their phones.

I spend a lot of time defending my decision not to get a smartphone. You can’t text me or call me on my cell because I don’t even carry it half the time. Who needs to be in touch with me that much? I’m not Hilary Clinton. Although I use email and the web for my business, I’ve reached the conclusion that my life online needs to be on my terms.

Online controls seem ridiculous and fiddly. Covering my monitor like parrot cage or shutting the processor down doesn’t work. A program that locks Internet usage for a period of time would make me feel the machine has even more power over me.

So I decided on the scorched-earth method: five days a week my husband leaves for work with the DSL router in a little lunch bag. When he comes home, he gives it back to me. I’m busy with supper then, which means I don’t go online until after six o’clock.

Truthfully? It’s kind of a pain. I’m working more in the evenings, but I’ve learned to zip through emails. Yet . . . I shop less. I sleep better. I can concentrate on the projects I have underway and not feel pressured. I don’t feel rushed or “crazy busy.”

Untethered to the Internet, I’m able to react less and act more. Move forward and not spin in circles. Make connections that are meaningful and not become ensnared.

Create a web—a fantastic weaving of midair dreams that might perish with a breath—because I can.

September 1, 2014

“Write At Least One Book”

“Did we drive sixty miles to take a picture of a cat?” my husband asked.

Not really. But it was Saturday of Labor Day weekend, and since Sunday and Monday were already spoken for, work-wise, we had to get out. This was our first day trip since Memorial Day. And where did we wind up? At a produce stand an hour south of where we live. Worse, even this pitiful trip was research-related.

I needed to take notes and photos of a working produce stand for a current project. The accidental cat was the highlight. The farm stand was a disappointment and the fields were already cleared. On the drive down, I noticed the roadside hem of summer-blue chicory has been edged out by fall-yellow tickseed. Sunflowers nodded in the early morning.

The week before, I planned to go to the produce stand alone, but couldn’t leave my office. It wasn’t work that kept me there, though it should have been. For once I had a week free of housework, yard work, appointments, and most errands. I would hunker down at my computer and pile up pages.

I didn’t.

What did I do all those hours? I surfed the web. I wasted nearly an entire week following blog posts, looking up facts, answering emails, tracking down books, checking Facebook, and, worst of all, thinking up things to buy on eBay.

I was well aware of my distracted state and tried to journal my way out of it. But even as I was writing, I stopped to click back on the Net. I couldn’t finish a sentence.

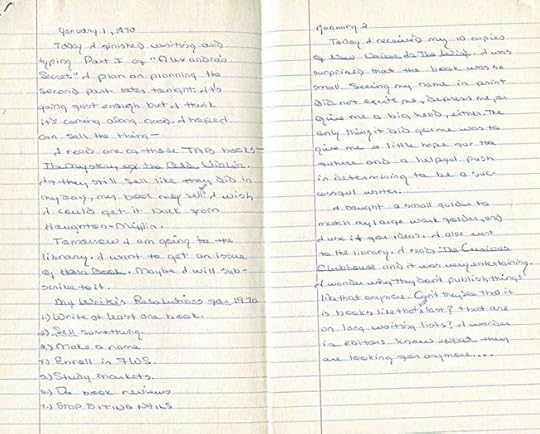

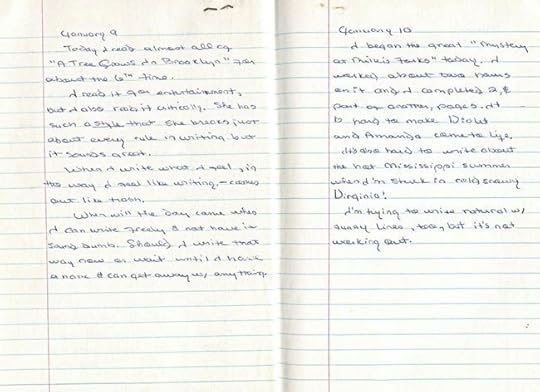

This week I dug out the small journal I kept as a high school senior, my writing record book. On New Year’s Eve in 1969, I wrote: I hope 1970 will bring me a home in the publishing world, the author of the book I want to write, and a smarter writer.

On January 1, 1970, I got down to brass tacks. I made a list of writing resolutions in addition to the goals for that month. The goals were specific and attainable: Write a story for Highlights. Decide on a definite book [to write] for summer. Finish, polish, and mail “Alexandra’s Secrets.” Some resolutions were more related to—well, growing up.

The entry for January 2 refers to receiving comp copies of an anthology my first poem was published in. I most certainly did get a big head. I turned down being named Class Poet because la-de-da me had been published.

When I read the journal, I was struck by two things. One: What I struggled with at the age of seventeen is still a struggle (“When I write what I feel, in the way I feel like writing—it comes out like trash”). Two: I had so much drive.

In high school I carried a full academic load and a full business load (so I could get a “real” job as a secretary). In my journal I noted that I was devoting another two hours to homework and an hour a night to write. My distraction back then? Television. “If I can learn to tear myself from the T.V. and just listen to it, it might work.” Yeah, right.

I am not alone in fighting distraction. Lynne Jonell wrote about her own battle. “On the one side, the writing; on the other, everything else in the world. And the world was winning with its usual one-two punch: fear and distraction.”

Jonell’s solution was to make a mark on a Post-it note whenever she felt the need to quit. After ten marks, she’d take a break, and then get back to work. She writes: “But I did a word count for the day, and divided it by the number of marks I had made, and discovered to my dismay that every thirty-three words, on average, I had fought a serious battle with myself just to stay with it.”

Over the years I’ve dealt with my distraction problems by spending money or over-exercising—yet I still got the work done, just as I did when I was seventeen and writing stories while “listening” to the television. Now we don’t even have television, I’m too poor to shop like I did and too tired to exercise like I used to. But there’s the shiny promise of the Internet just waiting to suck up all my time.

So starting today I’m taking another Internet leave of absence for one month. I’ll store the Internet computer in the garage. My husband will lock up the laptop.

I know I’ll look over at the empty space where the monitor usually stands. My fingers will twitch for the mouse that won’t be there. Every few days, I’ll go to the library, do email and research, and then I’ll walk away from the computer.

I’m hoping for a month of clarity and focus, of reclaiming myself. And if I’m lucky, I might even write at least one book.

August 22, 2014

Protective Camouflage

Ruth Sanderson, Elizabeth Dulemba, Lauren Mills, me, Dennis Nolan, Ashley Wolff, Eric Rohmann

This summer in Roanoke, I dropped money at a boutique called La De Da, so unlikely a place I’d ever shop that my husband called to see if someone was charging on our credit card. I bought unlikely clothes, too, an olive-green knit slip with tulle ruffles I wore as a dress. An ivory eyelet jacket with a net peplum I wore over a lacy half slip.

Yes, this was the summer I broke bad, clothes-wise.

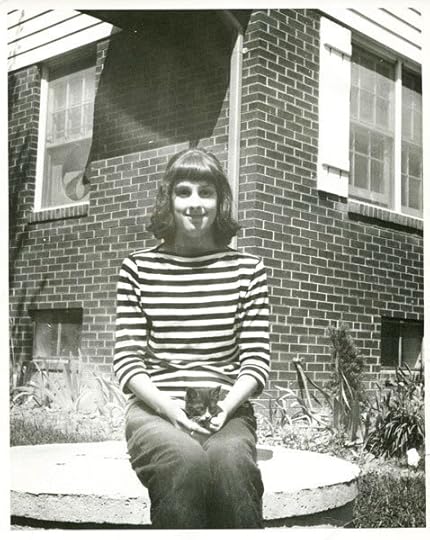

As a tomboy kid, I didn’t give a flit what I wore. Here I am at ten in plain pants and a top that “didn’t hang right in the neck,” as my mother said. I was comfortable and since nobody ever noticed me anyway, I could eavesdrop and pilfer through dresser drawers.

But girls grow up and become interested in clothes. The thick August issue of Seventeen was my bible (“nothing but advertisements,” my mother scoffed). I pored over those ads, longing for the just-right loafer with the just-right dress. When I fretted over my looks, my mother said, “You can’t make a peach out of a pear.”

Despite my Seventeen dreams, most of my clothes were handmade or hand-me-downs and I stood out in the wrong way. Mean girls poked fun at my outfits (I got back at them in my books). When I began publishing, I had to face the public. I didn’t want people to know I was uneducated and provincial so I created a persona with clothes.

In the 80s and 90s I ripped through a Gunne Sax phase and a Laura Ashley phase and a prissy Miss Talbots phase. Those clothes allowed me to walk into luncheons and conferences and convention halls and talk to people. But inside those expensive costumes, I was still a pear, shy, nervous, inadequate.

And then a wonderful thing happened. I went from middle-aged to—well, something just past middle-age. I became invisible. I could stop trying to be a peach.

I quit worrying about how I looked. That didn’t mean I attended conferences in a bathrobe with one sleeve ripped off and a pair of hip-waders. But I didn’t care if I wasn’t on the best-dressed list any more, either. I let my real self loose—irreverent, a little on the redneck side, and mighty comfy.

Most important, I discovered that being invisible gained me entrance into places where I didn’t want to call attention to myself. I heard things, saw things that I wouldn’t have if I was trussed up like a Christmas turkey. It’s the same reason I carry an ordinary notebook to those places. We see people tapping away on laptops everywhere. But not where I go.

When Julie Otsuka was working on her book, The Buddha in the Attic, she stayed “invisible and unwatched” in her day to day life. “I feel invisible and unwatched anyway. It’s my preferred stance in the world: I can see you, but you can’t see me.”

So when I came home from Hollins, I hung up the tulled-edged spaghetti-strap slip dress, folded the silky eyelet lace half-slip skirt. (I’ll wear them again next summer.)

I put on my protective camouflage, a brown jersey skirt or denim shorts with a tee-shirt, pick up my notebook and pen, and slip into my regular pear self where I blend in perfectly with my surroundings.

August 12, 2014

Muskrat Love

Me (in blue), Claudia with Tula, Elizabeth. Photo by Ashley Wolff, Tula’s mother.

We were up at 6:00 nearly every morning and walking by 6:30. The Hollins Summer Walking Team–Claudia Mills, Elizabeth Dulemba, and me. We talked, logged in countless miles, and never failed to appreciate the scenery spread before us.

I’d come to Hollins this summer not only to teach and talk but to find the words again. Words had left me two and a half years ago, though I’d become adept at faking it.

Hollins is the perfect environment. For six weeks I’m free from the hunting and gathering of food and waste management (my definition of running a house). I’d get up, make my little bed, walk, wash my one bowl and glass and spoon and would have the rest of the day to teach and talk and read . . . and write.

Last summer I sat in my Hollins apartment and stared at my laptop screen. One afternoon I became completely frozen, literally unable to get up for hours. I called my husband in a panic. He told me to shut down my computer and keep it off except for business emails. That’s what I did the rest of the term. And came home with nothing.

This summer it seemed like more of the same. A journal entry from early in the term:

I work all day but don’t really write. My journals sit on tables and chests, pen on top, but I hardly ever open them. I need to write an essay for the photo website and I can’t think of how to write about home. My last blog post was someone else’s words.

Last night as I tried to sleep, I saw those kids in my head again. Small, dark, and distant. They run around playing on a bowl-shaped surface. Maybe a hill. I can’t hear them and they won’t come to me.

Mornings The Team would walk and talk. We saw yellow-crowned night herons standing like upended croquet mallets in Carvin Creek. Swallows capered across the sky, showing off, and muskrats foraged in the grass along the creek bank.

I also walked the campus loop alone to break loose blocked thoughts. Soon I stopped thinking and simply looked around me.

Deer were plentiful this year. Herds grazed in the middle of the day, watchful but unafraid. I followed the roller-coaster flights of bluebirds until I memorized their songs.

Then there were the skunks. Passels of them roamed the grounds at dusk. I was standing on the porch of the old parsonage early one evening when this posse stampeded straight for me. I jumped off the porch and snapped a quick, blurry photo. Did you know a group of skunks is called a surfeit? Even one skunk seems too many when you’re wearing flip-flops and running down a very long hill.

This was the summer I fell in love with muskrats. I saw them swimming in Carvin Creek. I saw them feeding by the drainage ditches. I stepped in their bolt holes dug a few feet from the creek’s edge.

Muskrats are hinky creatures, skittering off the instant they spy humans, diving down the bolt hole and emerging beneath the bank. Their vertically flattened tails act as rudders, enabling quick getaways. The muskrats were a constant, reassuring presence. They went about their business without any fuss.

In her book A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit says: What is the message that wild animals bring, the message that seems to say everything and nothing? What is this message that is wordless, that is nothing more or less than the animals themselves–that the world is wild, that life is unpredictable in its goodness and its danger, that the world is larger than your imagination?

I turned off my laptop and carried a notebook. I didn’t open the notebook much, but carrying it made me feel better. I listened to the speakers our program sponsors every summer—writers, illustrators, scholars—and learned they went about their business without any fuss, too.

The best writing, Solnit says, appears like those animals, sudden, self-possessed, telling everything and nothing, words approaching wordlessness.

Two days before the end of the term, one of those dark, distant kids I kept seeing in my head turned to face me. She spoke. And I reached for my notebook.

May 12, 2014

Home: Not Always Where We Think It Is

The stars we are given. The constellations we make.

That is to say, the stars exist in the cosmos, but constellations are the imaginary lines we draw between them, the readings we give the sky, the stories we tell.

The desire to go home, to be whole, to know where you are, to be the point of the intersection of all the lines drawn through all the stars,

to be the constellation-maker and the center of the world, that center called love.

To awaken from sleep, to rest from awakening, to tame the animal, to let the soul go wild,

to shelter in darkness and blaze with light,

to cease to speak and be perfectly understood.

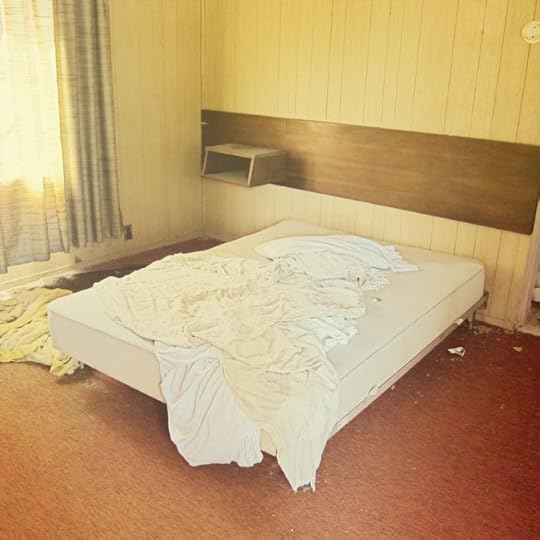

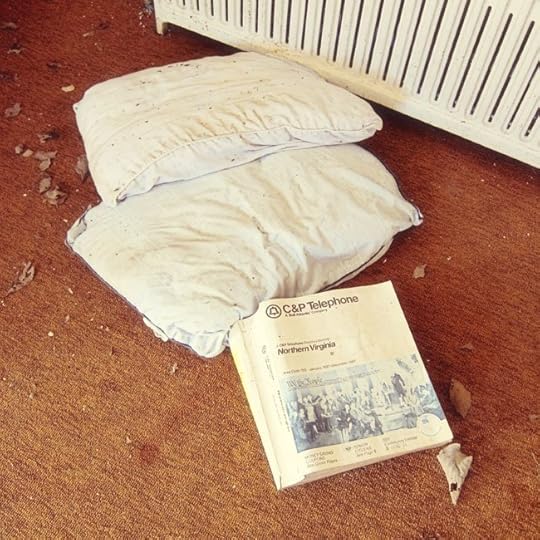

Nights alone in motels,

nights with strange paintings and floral bedspreads . . .

I have lost myself though I know where I am . . .

I have never been to this place before.

Times when some architectural detail or vista that has escaped me these many years say to me that I never did know where I was, even when I was home.

You get lost out of a desire to be lost.

But in the place called lost, strange things are found.

Text from Rebecca Solnit’s Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics, and A Field Guide to Getting Lost.

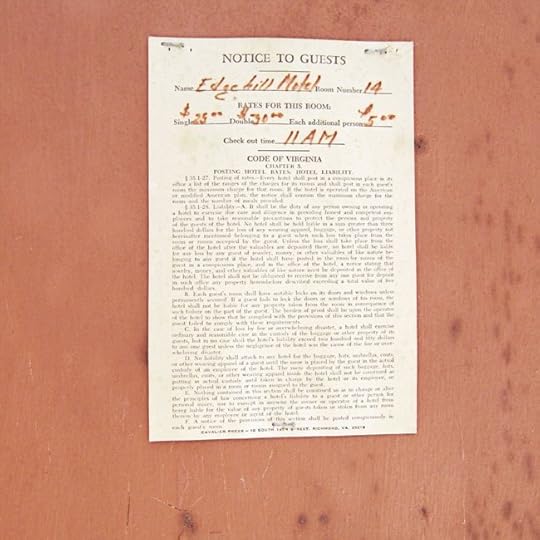

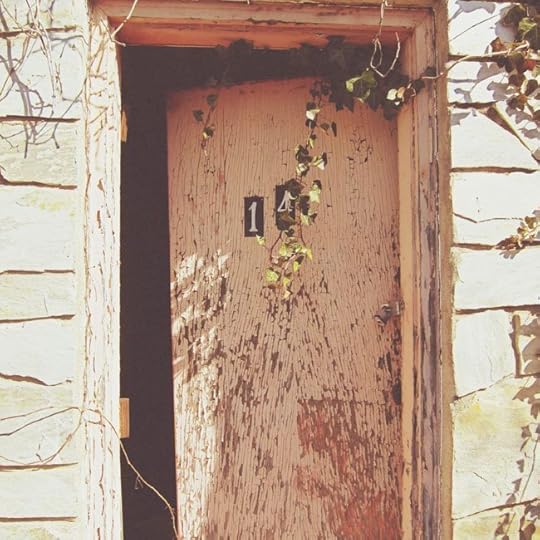

Photos taken in an abandoned motel on Route 301 in Virginia.

May 9, 2014

Robin Journal: May 9, 2014, Gone

They were fine yesterday, being fed, stirring in the nest. But I noticed squirrel activity in our yard. I went out and drove them off a few times.

This morning I sensed the silence. Then I watched the nest, good long minutes. No parent feed-relay.

I walked out just now to the shed. Peeped over the ledge of the window box. And down into the nest.

Empty.

I won’t show a photo of the empty nest because it’s too sad. I’ll bring the nest in and save it. Scott and Zelda are around. She’ll rebuild in another site and they’ll try again. These photos are from yesterday.

It could have been an owl, though I suspect squirrels. They were in the trees around the shed when I checked the nest. I look at them hard. They just folded their paws and looked back at me.

May 8, 2014

Robin Journal: May 5-7

Monday, May 5

It is no picnic taking these pictures. Scott, who has been on paternity leave the last two weeks, has suddenly taken over a major role. Scaring off intruders!

The babies are growing fast. Right now they sleep a lot, like most newborns, but are ready to eat whenever Scott or Zelda lands at their nest. Watching the parents through the scope, I see them sort of break the food up before distributing it. Maybe those little gullets can’t have a whole worm stuffed down them? Also, everybody poops. The parents take away waste on every trip, which seems to be in little sacks.

So here they are: Irene, Howard, Bill, and Esther.

At the top, Monday, May 5. Note the long skinny neck pitched forward into the nest. It takes a lot of energy for them to pick their heads up.

Tuesday, May 6

Tuesday, May 6. I love their little yawping mouths. When I approached the window box, I could see the tips of beaks waving around. They are so cute! If you look closely at the one with his beak turned up, and the one with his mouth open, you can see the slits in their eyes. Soon they’ll be gazing at the world.

Wednesday, May 7

Wednesday, May 7. Scott swooped down at me when I was trying to get a closer look. I snapped one picture but it showed a bad case of camera shake. My husband filled the birdbath and I let him run interference while I took another picture a little later.

Both times the nestlings were sleeping, even though they’d just been fed. You can see the backbone of the one in the bottom left. Their wings look a bit more defined. It’s not going to be easy to fix chicken any more.

May 5, 2014

Robin Journal: May 1-5, 2014

Once again, Zelda has not been reading What to Expect When You Are Expecting. The last egg was laid Easter Monday. I figured the first two birds would hatch May 3 (she laid two eggs in one day), the third May 4, and the last on May 5.

This past weekend we went away for our delayed Valentine’s anniversary to Colonial Beach. I watched ospreys busy in their nests and hoped Zelda was okay. When we got back Sunday morning, I peeked in the nest. I didn’t check it on Friday, the day we left, but clearly everybody had been busy while we were gone.

Irene, Howard, Bill, and Esther are here! They aren’t much to brag about now, but Scott and Zelda think they are beautiful, bulgy black eyes, visible livers, gall bladders, and all.

Looking at the naked helpless little sack-birds reminds me of the burdens I shouldered as a kid. Too skinny. Near-sighted. Crooked teeth. Chronic allergies. Picked last in every single game. Unable to tell time or tie my shoes or ride a bike.

To have one or two of those liabilities is bad enough. To have them all paints a dreary picture of a scrawny, buck-toothed, adenoidal, uncoordinated kid who tripped over her own shoelaces and never knew if the clock said eleven-thirty or five till six.

Making matters worse, I watched birds, adding another taunt to my lengthy list: Bony Maroni. Snaggle-tooth. Snot-nose. Spaz. Birdbrain. I couldn’t do anything about the other faults but birdbrain I brought on myself.

Why birds? Because I lived in the sticks and spent most of my time alone. Birds were always around. They kept me company. They fascinated me (“fastinated,” even). Who doesn’t want to fly? When I was five, I jumped off our tall front porch with a paper lunch sack in each hand. Instead of soaring, I landed hard, spraining both knees.

Okay, if I couldn’t be a bird, I would watch them and learn their secrets. Maybe they’d help me navigate life a little easier.

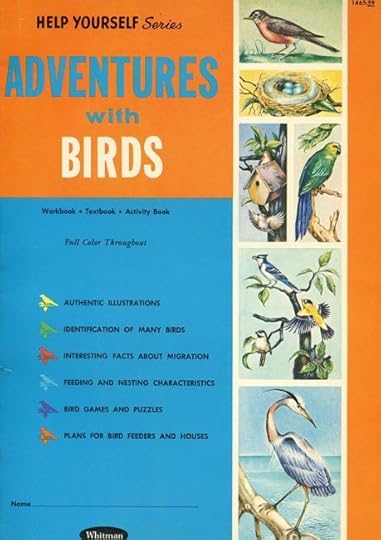

First, my love for birds made me turn to crime.

In Drug Fair once when no one was looking, I snatched a tiny brown bottle with a parakeet on the label. I waited with my mother as she checked out, the Hartz Mite Drops burning like a live cinder in my pocket. Outside it was dark. My pale face reflected in the plate glass window didn’t reveal a wrinkle of guilt. Yet at home I hid the bottle under my mattress and tossed every night like the Princess and the Pea until I threw it away.

Next, my love for birds turned me into a liar.

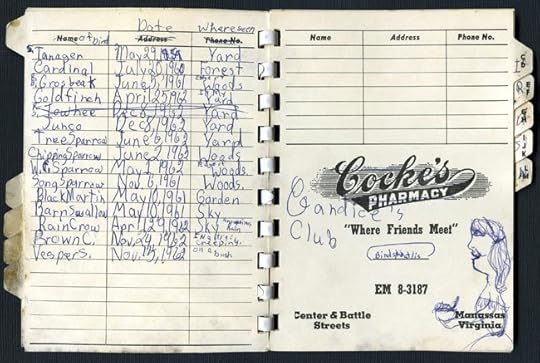

I bought the Golden Guide Birds and studied it like I was passing the bar. The book recommended keeping a list of birds sighted. I converted my mother’s address book into my Life List, which is larded with lies and doctored more than the ledgers of an Atlantic City mobster. Vesper? I don’t think so. The “R.B. Grosbeak” (rose-breasted grosbeak) I claimed to see at the “edge of Woods” was most likely a house finch.

I collected nests and feathers and egg shells and lined them on my bookcase, to my mother’s horror. “Lice infested!” she screeched, even after I cooly informed her lice vacated nests as soon as the bird hosts did.

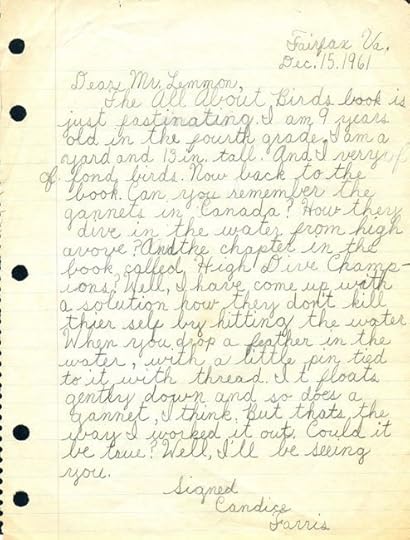

In fourth grade I wrote a letter to the author of All About Birds, a book I’d checked out of the library so many times, the librarian should have given it to me. Clearly I was into facts: “I am a yard and 13 in. tall” (I didn’t mention I only weighed about 40 pounds). I remember conducting that earth-shaking experiment. I stood in our pink-and-black tiled bathroom, tied thread around a straight pin and a down feather plucked from my stepfather’s pillow, then dropped it in the sink. Madame Curie, stand back.

As an extra flourish, I made Mr. Lemmon a Christmas card (a trace of green glitter remains). But I was stymied where to send it. The world would never know a brilliant nine-year-old figured out how gannets in Canada don’t “kill thier self by hitting the water.”

My mother saved the letter and the card.

When I was ten, I saved enough Top Value stamps to buy my first pair of binoculars. My too-close-together eyes paired with a bulging astigmatism made viewing through regular binoculars nearly impossible. But I carried them with me anyway.

Sometimes people were impressed by my encyclopedic knowledge of birds. “What kind of a bird is that?” one of my cousins would idly ask. “A grackle,” I’d reply crisply. “Notice that it’s bigger than a starling and doesn’t have those yellow speckles on its feathers. The grackle has a wider tail and a yellow eye—” “Yeah, okay.”

I stayed in Birdland until seventh grade. By then I’d decided I would become an ornithologist (and a mystery writer) only I didn’t know how to pronounce it. In our unit on occupations, I told my teacher I wanted to be an “or-nee-thee-o-lo-gist.” She didn’t know what the heck I was saying and put down “forest ranger.”

By eighth grade I realized my love for birds, along with my homemade clothes, would never net me any friends. I started haranguing my mother for store-bought outfits or reasonable facsimiles of Villager blouses and skirts. I put away my binoculars, passed my bird books to my niece, and tossed my nest and feather collection. Time to give up birds.

Well, I’ll be seeing you.

Eventually I gained weight, learned how to tell time (digital clocks!), smiled with my lips closed, got allergy pills, rode a bike, and decided team sports were overrated (give both sides a ball and send them home).

But birds didn’t give up on me. They were always there. Waiting to keep me company. Willing to reveal their secrets. Our adventures continue.