Candice Ransom's Blog, page 9

May 1, 2014

Robin Journal: April 24-May 1, 2014

Photo by Donna Hopkins who has a way better camera than I do, and in general takes better pictures.

It rained for three days and three nights. Epic rains. Biblical. If I wasn’t a teetotaler, I would have downed tumblers of gin. But at least I was indoors where it was dry. Zelda had to incubate those four eggs.

My husband set up a spotting scope for me to watch the nest. I’d look out the window and there was Zelda, sitting tail up, head up, body spread to cover the clutch. Rain dripped off her beak. Her feathers contain oil to reduce some wetness but nothing like what fell from the sky. It remains to be seen if her nest will be a success.

During the last week and a half, Zelda has sat, leaving her post only for a minute or two to eat. And I have sat, too, at my desk, working. Sometimes I thought about running away to someplace sunny. Instead I visited blogs.

I found a blog post called “The Crossroad of Should and Must,” a discussion of why we should ditch Should and go for Must. Should is our regular life. “How others want us to show up in the world . . . When we choose Should the journey is smooth, the risk small.”

Must, on the other hand, isn’t an option. “Must is who we are, what we believe, and what we do when we are alone with our truest, most authentic self.” Hmmm. I always thought that Must was Should—as in, “Today I must go to the grocery store or we will starve.”

Must is about calling, the thing we should be doing, but not should be doing. The author of this post worked at Mailbox. She left a great job to become an artist. She didn’t know her calling but it began with a dream about a white room. Where was this room? She looked on Craigslist. And there it was! When she moved into the white room, a voice said she should paint.

From there she took an Airbnb in Bali to be alone for six weeks. I had to look up AirbnB (also Mailbox, plus I had no idea you could find places in your dreams on Craigslist). In the Bali hut she made paintings of the moon. Back in California, she tried to figure out how to turn moon paintings into fabric designs, so she took an Airbnb in New York City. She sold her fabric and launched a new, even better, career. She talked a lot about results and Picasso.

In a nutshell: Life is short, go after your dreams. These days when I am alone with my truest, most authentic self, I want to sleep. Or eat chocolate.

From This Wild Idea website

Next I jumped to a blog about one of my favorite photographers, Theron Humphrey, and his project called This Wild Idea. I love this project. When Humphrey’s grandfather died, and he realized there would be no more stories, no more photographs of him, Humphrey quit his soul-draining product photography job. Then he set off to find one new person to meet and photograph. From August 1, 2011 to August 1, 2012, he traveled all 50 states in a truck with a coonhound named Maddie. He posted the photos and stories online for 365 days.

I drool over this idea. But it isn’t going to happen. Wanting to take to the road and photograph people, with or without a dog (Winchester would be out of the question), is not a Must calling to me. Neither was living in a hut in Bali to think for six weeks. There are too many Shoulds in my life.

It has occurred to me that the Internet, like advertising, creates dissatisfaction. Fantasy writer Terri Windling says on her blog that “reading on the Internet, with its mass choir of voices and its speedy, amped-up rhythms, spins me away from my inner Lake of Words and off into other directions.” Yes, me too.

(Yet the Internet works for a lot of people. Airbnb. Crowdfunding got Theron Humphrey his nest egg for his venture. Instagram made his dog famous and nabbed him a book deal. And This Wild Idea earned him National Geographic Travel award for the Year. The woman in the white room is also successful.)

I clicked off the web with a sigh. There comes a time when you can’t ignore the Shoulds. You own a house. You have family obligations. You have health issues or your loved ones have them. It would be lovely to go traipsing off, but you can’t.

Every evening, I’d look through the spotting scope at the nest. I could see the silhouette of Zelda’s head against the shed wall. Does she hear Must telling her to fly to Bali? Or be a cowbird and lay her eggs in other birds’ nests so she can be free?

Zelda sits steadfast. Patient. Waiting. Her Should is not a smooth journey and the risks are great. She has the highest possible need for results—hatching her eggs.

As for me, I need to turn off the “mass choir of voices” and get back to work. I’m lucky enough to realize Must called to me when I was fifteen (though it was my English teacher who told me I should be a writer of children’s books). I’ve been trying to answer that call ever since, even when more Shoulds crowd into my life each year.

April 23, 2014

Robin Journal: April 20-23, 2014

After dragging her tail feathers for about a week, Zelda finally got ahead of me. Saturday she had two eggs (one more than I guessed). Easter Sunday I watched her sit on the nest with a look of concentration. It wasn’t mid-morning like the book said, but about 8:15. (If you’ve been up since dawn hunting worms, 8:15 is mid-morning). She flew away after about twenty minutes. Later she came back and settled herself for a long stay. I figured she’d laid her last egg and was now incubating.

Sure enough when I checked that afternoon, three beautiful eggs lay in the sunny nest.

Oh, I thought, I hope she stops at three. Five in the family would be perfect.

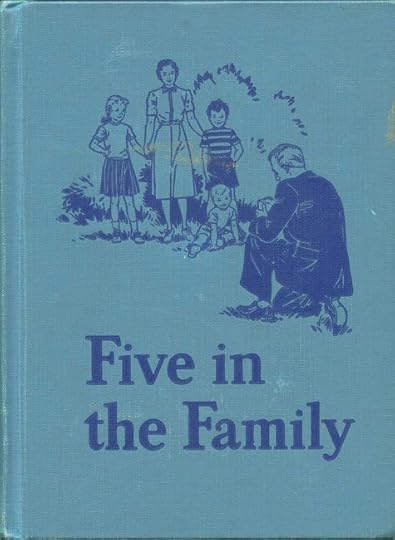

I always thought families of five was the perfect number, a notion that probably came from an old health textbook of my sister’s called Five in the Family. Back in the Dark Ages, we bought our textbooks instead of renting them. My sister left her books behind and I read them and drew witches in her old spelling book.

The family in Five in the Family consists of Mother, Father, Sue, Jack, Tommy, and Jack’s puppy Spot. The front cover shows Father taking a photo of the others (using a Brownie box camera). Each section features a different member of the family. At the beginning are “photographs,” giving the book an album look.

I suppose that was part of my fascination with this book. It certainly wasn’t the writing:

It was Jack’s birthday, and the family was looking at pictures of him. “Oh!” laughed Jack. “Here I was on my very first birthday.”

“This is how you looked at three,” Father said. “And here you are at five.”

“I like last year’s picture,” said Sue. “Tommy and I were in it, too.”

“And now you have another birthday, Jack,” said Mother. “Dear me! How fast the time goes!”

The stories are all syrupy because it is, after all, a reader on health. For Jack’s birthday party, “There were hot soup and sandwiches, milk, and apples.” If I’d been invited to that party, I would have stomped out.

Despite the book being soaked with insipid dialog like, “Oh, Daddy, why didn’t you tell me before you took my picture? Then I could have been standing straight,” I read this book over and over, memorizing the illustrations. I wanted to be in that family.

Last year a new family moved across the street from us. Mother, Father, a boy, two girls, and a dog. Five, the perfect number. I watched them out the window on school mornings. The mother walked the boy and the oldest girl to the bus stop, carrying the youngest girl. She kissed them goodbye and waved until the bus rounded the corner. In the afternoons, the boy and girl hopped off the bus and raced home, eager to return to their safe, cozy nest.

I remembered how I stood at the bottom of our driveway alone, waiting for the bus to come down a busy highway. At the end of the school day, I walked slowly up our long steep driveway.

Last weekend I glanced out the window (we have lots of windows in this house—I don’t really spy on the neighbors!). The father spread a blue blanket under their blossoming Bradford pear. The kids came out carefully carrying a glass and plate. The whole family ate their lunch in the front yard, the dog bounding from one to the other. Later the father helped the youngest roller skate and then played catch with the middle girl.

I thought how well-loved these children are, how good and kind their parents are. Such a contrast to my own childhood. It wasn’t that I wasn’t loved. I wasn’t well-loved. I know the difference. And I knew it then.

Five in the family. Scott and Zelda would have three children. Two boys and a girl. I would name them Bill, Howard, and Irene, after my brother-in-law, stepfather, and mother. I like the idea of them coming back as robins. And I decided to throw a little birthday party when they get here—with cake and ice cream, no apples or soup or milk.

Then next day when I checked the nest, Zelda had left me a surprise. A fourth egg. Six in the family is okay, too. I’ll name the new robin Esther, after my husband’s mother.

They’ll be here in less than two weeks. Two weeks in the nest. And then they’ll be gone. How fast the time will go.

April 20, 2014

Robin Journal: April 16 – 20, 2014

After last Tuesday’s day-long downpour, I didn’t see Scott and Zelda all day Wednesday. Or Thursday. After the rain it turned cold. Too cold to lay eggs. I checked the nest—it seemed fine. But where were they? They’d left. I was sure of it.

Once, song sparrows nested in our front-door wreath. The female laid four pale blue speckled eggs and then disappeared. Granted, the front door wasn’t the best place for a nursery. But I’d taped off the entrance and snarled at anyone who put a toenail on our front porch. Still, they left. Heartbroken, I removed the nest and eggs.

I decided, in my perverse way, that because I wanted a family of birds, I couldn’t have it. No, they’ll nest under our neighbor’s two-story deck like they did last year. “Robins have got a nest there,” my neighbor told me with an edge of disgust.

Friday afternoon, I went out to check the nest. Zelda was in it! Joy rose in my throat. Zelda stood in the nest, picking the edge of it. Was she eating it? Then she stuck her head under the fake yellow tulips. I’d read that robins typically lay when the nest was ready. That they lay mid-morning, not at dawn like most birds. That the female lays one egg a day. That she doesn’t start incubating until her clutch is complete.

Clearly Zelda is a first-time nester. She hasn’t read the book and doesn’t know she’s not supposed to stick her head under a bunch of fake tulips. I hoped she’d get in gear soon.

Saturday we went out and I didn’t think about the robins. Hardly. When we came back that afternoon, I checked the nest right away. Two eggs! But Zelda is supposed to lay one egg a day (it’s much harder than you think). I admired the size of them—the first brood of the year has the biggest eggs. I didn’t tell Zelda she’d have to build another nest and lay more eggs again . . . and possibly a third time.

Beautiful blue eggs for Easter. How perfect. Almost as perfect as my ninth birthday.

My birthday fell on a Monday in 1961. The weekend before, I went with Mama to Grandaddy’s and Grandma’s. They were both sick and old. I hated their house with its dark woodwork and medicine smells, the creak of Grandma’s wheelchair, her wild stare, Grandaddy’s cough, the fact I had to be quiet.

That Saturday I was reading about whooping cranes in a library book. Only 21 whooping cranes were in existence! When Mama said she was going to the store for a few minutes, I was too engrossed in the plight of the whooping cranes to fret about being left alone with my grandparents. I snicked chocolate drops from Grandaddy’s secret stash in the dining room and wondered how I’d get to Texas to save the cranes.

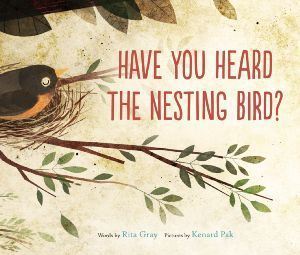

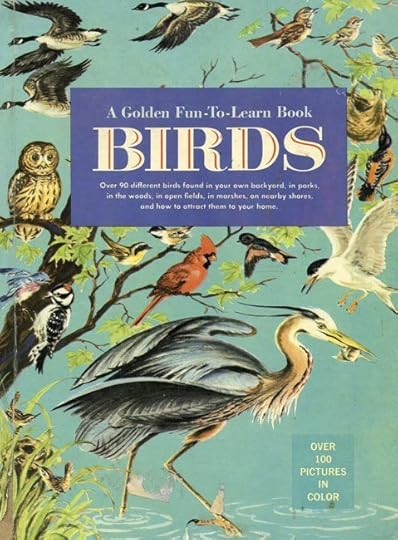

When Mama came back, she set a paper bag from Drug Fair on the chair and checked on her parents. I saw a book peeking out of the bag. The Golden Fun-to-Learn Book of Birds had a beautiful blue-green cover and cost 59 cents. I shivered with delight. Mama bought me a bird book for my birthday! I pretended I hadn’t glimpsed the book, but spent the rest of the weekend wrapped the wonderful knowledge of it.

I don’t remember my birthday. I’m sure we had homemade ice cream, probably lemon. I don’t remember my older sister being nervous and edgy, but she must have been. I was newly nine and in love with birds.

Three weeks later, my sister left home. Left the nest first. Left me.

It took a long time to realize that her leaving wasn’t personal. At fifteen, Pat eloped with her boyfriend. My sister didn’t have an instruction manual either. Nest-building and family-raising came hard. I didn’t know any of that. I only knew I was alone. I felt like one of the last whooping cranes. But birds—and books—saved me.

I don’t know what happened to my Golden Fun-to-Learn Book of Birds. Tossed out, I guess, or passed along to my niece. Later I tried to find another copy but couldn’t remember the title, only the color of the cover—blue-green. I found The Golden Play Book of Bird Stamps (previous owner had rudely licked in every stamp). I found Adventures with Birds (previous owner had played all the games). I found the Whitman Big Guide, Birds Everywhere. Those books seemed close, but not quite it.

The title page

A few years ago, my husband and I were browsing in an antique mall. Downstairs in a back corner, I saw a book on the floor. My heart stopped. There it was–The Golden Fun-to-Learn Book of Birds. When I picked up the book, it seemed to vibrate in my hand, like a divining rod. It was only $2. I would have paid $50.

The last spring my sister was home, we dyed eggs for Easter. We dunked our hard-boiled eggs in teacups with Paas tablets dissolved in water and vinegar, taking turns using the wire egg-dipper. I always took my eggs out too soon. They seemed just the right color bobbing in the teacup, but when I set them wetly in the punched-out holes in the cardboard box, my yellow seemed pallid, my purple too pale, my blue too tentative.

My sister had the knack. She’d drop the eggs in one color and then another—blue and green—and leave them a good long time. And that’s how she created the most beautiful egg of all. Robin’s egg blue. The color of my book cover. The color of the eggs in the nest in the window box. The color of our last spring at home together.

It has remained my favorite color my entire life.

April 16, 2014

Robin Journal: April 14 and 15

April 14:

As soon as it was daylight, the robins were working on the nest. Today they were cooking with gas, no add a bunch of grass and then take the rest of the day off. They took turns flying straight to the window box. Normally the female does the actual building, but sometimes the male will help.

So many quick trips were made to the site, I’m sure the male was involved. After delivering material, they flopped around inside the window box. It was funny, like watching fat people trying to get out of a bathtub.

But it’s also hard, creating a nest with nothing but a beak, feet, and breast. I tried to take pictures of this process. My little Canon wouldn’t zoom close enough, plus I was taking photos through a window screen.

So I ran upstairs for my Nikon. I wrenched the lens but that just made the image out of focus. I ran back upstairs for my Nikon book. Where was the *&^%$ zoom button? The one I found was for reviewing photos. Frustrated, I set the Nikon down before I threw it in the trash, and ran upstairs again to take pictures from an upstairs window with the Canon. Now I was even farther away.

I took two dozen pictures, a fuzzy glimpse of a head, a blurred wing, a tail poking up. The birds would have been more entertained by the lunatic photographer if they weren’t so busy. I went out to run errands. By the time I got back, they were still at it.

I clocked six straight hours of ferrying materials to the window box. And then they were gone. Figuring it was safe, I took a bucket of water for the birdbath (my excuse for barging in uninvited) and my camera. I leaned in. Ta-da!

I felt as proud as if I’d made that nest myself! Notice the scratchy mud prints on the sill of window box. Did they use dirt? You betcha. Check the earlier photos from the post two days ago. No dirt in the first picture. A little tiny bit of dirt the next.

The nursery seemed ready.

April 15:

It rained ax handles all the livelong day. I fretted over that nest with no protective overhang and even considered taking an umbrella out and somehow attaching it to the window box.

I called my husband. He said he could build a little roof. Then I realized that birds everywhere had soggy nests. They probably weren’t happy but it was part of setting up housekeeping outdoors.

I checked the robin’s timetable: when the nest is ready, the eggs will be laid one day apart for up to five days, and she’ll lay in mid-morning. The first clutch of the season will be bigger than the second. She’ll incubate the clutch for two weeks, beginning when the last egg is laid. That way the eggs will hatch at the same time. The baby birds will stay in the next about two weeks.

I’ve named my nesting pair Scott and Zelda. Waiting . . . waiting.

If you want to build your own robin’s nest, here’s how: www.learner.org/jnorth/tm/robin/BuildNest.html

April 15, 2014

Robin Journal: April 13, 2014

I walked outside to the glorious orchestra of birdsong and budding trees (yes, they sing too). Two male robins got into a fight, a swirling dance of beating wings and yellow beaks. The female robin—my nest-builder—flew in low and began tugging at the dead grass. Her look clearly said, Take it somewhere else, boys. I’ve got work to do. She carried the grass back to the window box. So she was still working on the nest!

The bird garden wasn’t finished. This was a project I’d dreamed up in April, 2009. The area was a jungle of honeysuckle, creeper, and weeds. My husband cleaned it out, added mulch, and bought two holly bushes and a rhododendron, which promptly died. (Our Rule of Gardens: plant three, one will die, usually the prettiest.) The next spring we replaced the fence (plastic! love it!), built the shed, and started the cat cemetery.

After breakfast, we bought a truckload of shredded mulch. Buying mulch in bags means you have the luxury of spreading it when you want. Buying a half ton of it loose means you deal with it immediately. We dragged out spades and rakes began shoveling and raking. A robin watched us warily from the shed roof.

When we were done, wearing as much mulch as was on the ground, my husband cleaned out the shed, a noisy and disruptive operation if you were a robin eager to work on your nest. I had bought a chippy, rusted motel chair for a price that nearly made my husband faint. I wanted something in the bird garden that was different, that the birds could poop on, and use the seat for a feeder. I made note that the large black leaf keeper that attaches to our lawn tractor and does not work would go next.

That afternoon I weeded the daylily flower bed. This sounds as grand as the “bird garden”—someone gave my husband seven daylily bulbs which he planted around our light pole. Daylilies are a bit boring but also no trouble. Until they get going good, though, chickweed runs rampant.

The sun was bright and strong, as it is in April. A mockingbird sang on our fireweed bush. A cardinal cheer-cheered across the street. A song sparrow, destined to nest in a “dwarf” spruce we need to chop down, sang from the dormer roof. I realized the sparrows beat us to it again. The spruce will stay and for the next year I’ll hear people struggling up our walk, saying, “I wish they’d cut these bushes back.”

It’s hard to understand that even in our crummy clay-ey soil, things grow at a ridiculous rate. The dwarf spruce bushes are almost up to the gutter. Give a plant an inch and it’ll take an acre. And it is no small matter to “cut them back.”

The neighborhood was full of familiar sounds: Patches the dog barking. Kids in the cul-de-sac playing and yelling. Cars pulling up to the stop sign, their radios blaring pop, rap, country. As I grubbed out a fistful of chickweed, I realized this was home.

It was a notion so startling I sat back on my heels. We built this house almost 18 years ago. The house has been decorated and redecorated, painted and repainted, carpets yanked up and hardwood floors put down, furniture, accessories, and different colored towels have come and gone. We planted azaleas and roses, mowed the grass from April through November. The house was my home.

But not the place.

I never claimed my neighborhood as home. I lived in Fredericksburg, but it wasn’t home. Home was—well, where was home? It’s not the house we lived in before moving here. Other people live there now. The house I grew up in has been torn down.

As I clutched that hunk of chickweed, I thought, “This is my mockingbird, my cardinal, my song sparrow, my overgrown spruces. My cars playing music, my kids yelling.”

It was an unsettling moment. I’ve spent so much of my life looking backward to a place I can’t ever go back to, or looking forward to a future that I believed was somewhere else, that I never let myself think, “I am home.”

I carried that thought around with me all day, tight in my grasp the way the robin had carried grass in her beak, afraid I might drop it.

April 14, 2014

Robin Journal – April 12, 2012

I would never have noticed if I hadn’t been sitting in my husband’s chair at breakfast. Early April sun poured over the table on my side and I couldn’t read. (Reading and eating is one of my greatest pleasures.) I happened to look up from my book, The Signature of All Things by Elizabeth Gilbert, my mouth full of cereal.

I saw a female robin light on our deck rail. She had a bunch of grass in her beak, much like my flaxseed cereal. She flew to the window box on our shed then stuffed the grass in one corner of the box with a lot of awkward flapping.

She’s building a nest! I thought, delighted. And in full view of where we take all our meals! I practically had to lash myself to the chair to keep from running outside.

A few days before, I’d spent the entire weekend raking five years of leaves out of an area we call the bird garden.

That rather grand name describes a stand of random saplings—a struggling dogwood, a bully of a cedar tree that’s so ugly I threaten to cut it down, a scraggly native holly and two holly bushes we planted—all ringed by mature sweetgum and hickory trees that drop millions of gumballs and hickory nuts. The unlikely group of saplings was “planted” by birds so it’s fitting the area is theirs. The garden contains a birdbath, feeders, and the cat angel statues and plaques that mark the graves of Xenia, Mulan, and Persnickety.

That weekend I raked and bagged and pruned and swore—getting pricked in the butt by holly bushes and slapped in the face by that ugly cedar was hardly my idea of a fun time. I picked up an entire truckload of sticks. The next truckload was filled with leaves. We needed mulch but everybody else had the same idea and by the time we got to Home Depot, there were only six bags left, three of them torn. We spread the six bags in the garden, but it was like a teaspoon of water in sand. The robin may have been sitting on the shed roof, watching us, scoping out the window box as a nesting site.

After breakfast, I went outside with my camera. I had painted the window box bright red and keep fake flowers in it, depending on the season. The yellow tulips had been shifted by the wind, leaving a gap at one end. Just enough room for a nest.

I snapped a quick photo. The nest was pretty skimpy, just a hollow of dried grass. I thought the robin had made a poor choice. The window box is low, with no overhanging roof or protective foliage. The nest would be open to rain. It’s also open to a very nosy writer-birdwatcher.

There was little activity the rest of the day at the window box. Had my presence scared off the female? The next day I tiptoed out and took another photo. I didn’t linger, just leaned over with my camera and snapped. Inside the house, I compared the photos. Was there any change? Was that piece of grass on the left in that spot the day before? Was she going to add mud? Did she need to since the nest didn’t have to be anchored to a tree branch? Was she coming back?

Please, stay, I silently begged the robin. Despite my lifelong interest (obsession) with birds, I’ve never watched a nest being built. I’ve never seen eggs laid one at a time and then hatch and the hatchlings grow into fledglings.

I need this nest.

March 31, 2014

When Our Stories Won’t Speak

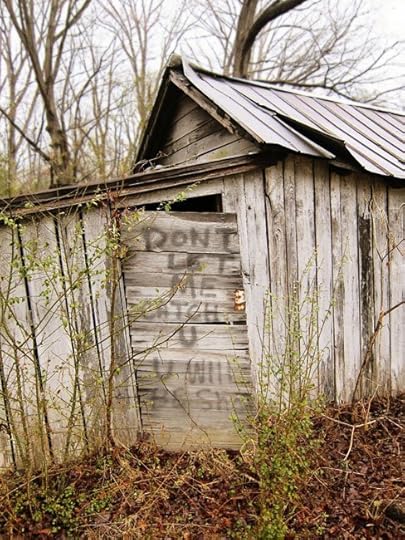

Two years in a row, I’ve wandered through the same abandoned house in Luray, asking it to give up its story. The front door was open, but inside the walls were tight-lipped. Both trips, my photos came out smoke-grey and silent.

This weekend I found another abandoned house. I welcomed the opportunity to let my restless mind run loose off its chain. I also hoped roaming someplace new would give me the answer to a problem I’d been wrestling with.

The past three months, I’ve been trying to settle on a book to write. I’ve drawn from the well over and over and the bucket has always come up brimming with ideas.

Some of those ideas greeted me eagerly, following me from room to room and I’d think, Yes, this is the one. But then the idea would drift off and I’d forget about it. A few days later I’d wonder, What was that idea again?

Another idea was so good, I felt that old electricity sizzle in my fingertips. I know this story! I thought. Because it was mine.

I began researching the time period (sadly, my childhood is now a “time period”), made discoveries that dragged me right out of the story. My adult self couldn’t ignore what I’d learned. My childhood self turned away in disgust for ruining a perfectly good idea.

Some empty houses let me uncover the ragged, unvarnished truth and dare me to blink. How much do you want to know? they seem to say. How bad do you want this?

People inquire about my process, how I begin a new book. I open a notebook and get a dialog going. The notebook goes with me everywhere to record any stray thoughts (last summer Hollins writer-in-residence David Almond generously shared his notebook with my class–we pored over his dense notes scribbled all over the pages). But lately, after a day or so, I lay the notebook down and won’t pick it up again.

How bad do you want this?

As I wandered around the place, snapping photos, bits of its story came through.

It occurred to me that maybe this story, like that last hard-edged idea, isn’t mine to tell.

So what do we do when our stories won’t speak to us, shrug us off?

Should we keep going to the idea cupboard or grab the idea we already have by the scruff of the neck and insist it stays and behaves? Jot notes and create character sketches until we make the idea viable?

It’ s not enough to construct a narrative into being.

Do we love those characters, that place, that story? Do we think about them all the time? If I truly loved all the ideas I pulled up in the bucket, I wouldn’t start notebooks and then abandon them.

I suspect the book I really and truly want to write is an old one. I’m worried the idea is too old (first came to me in 2009), but then ideas don’t have expiration dates. It’s the one I keep coming back to. I love the place. Love the characters. Love the story that’s waiting for me.

All I have to do is open the door and walk inside.

March 24, 2014

The Idea of Birds and Other Small Dreams

Last weekend at my revision retreat in Luray, I remembered a dream I once had. My mind was relaxed by being in a different environment. A window-crack of space opened and a sleeping memory slipped in.

When my husband and I were first married, I was filled with dreams of our future. Some were silly, like flying to Paris on the Concorde for a café lunch of chilled white asparagus with shaved prosciutto, and flying back home on the Concorde before supper.

Then there was my dream house, a Victorian farmhouse. I built a two-story kit dollhouse with gingerbread trim and curved shutters I glued on backward. I painted the exterior sky blue and drew hearts on the backward shutters, papered the rooms in a cabbage rose print and furnished them with a miniature Hoosier cabinet and “iron” bedstead. My mother stitched tiny gingham curtains. I glued a chip of wood over the front porch that said Bramblewood Cottage, and was ready to move in.

My husband and I never shrunk to three inches and we aren’t living in a sky-blue Victorian farmhouse, but we do have a big front porch and shutters that are hung properly.

At the Mimslyn Inn in Luray, somewhere between the exercise on setting and the cookie break, an older dream fluttered through my mind. The library I was going to create, a dollhouse of a library just for children.

Noyes Children’s Library

In the early 70s, I stumbled on the Noyes Children’s Library in Kensington, Maryland. Founded in 1893, it is the oldest public library in the Washington Metro area. Noyes became a children’s-only library in 1969. When I discovered the mansard-roofed cottage, I was enchanted. I stepped into a single room with low bookshelves filled with picture books, a rocking chair, and soft rugs on the floor. I was ready to move in.

Original Noyes Library

The idea of a library just for children stayed with me for years. I dreamed of starting my own children’s library, a cozy cottage nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge. The big front room would be the domain of little children, but I’d add a second room for the deep reading age of eight to eleven year olds, with carpeted levels, like a tree house, and wide windows to encourage daydreaming.

My husband and I discussed the little library in earnest. We studied floor plans and I drew sketches. When we drove into the mountains on day trips, we scouted locations. Standardsville? Crozet?

Last weekend, I glanced out the sunroom windows where our retreat was held, took in the slopes of the Blue Ridge rising behind us and the Massanutten range tumbling across the valley, and wondered where that dream had gone. It had gotten lost in thirty-five years of moves and work and losses and health issues and money troubles. I felt sad. Such a sweet dream, so unselfish, it should have materialized from goodness alone.

And then I recalled the martin birdhouse my stepfather built for me when I was ten. In Manassas, where we did our weekly shopping, I’d noticed apartment-style birdhouses for purple martins in people’s backyards. We could attract those lovely martins, too!

My stepfather constructed a huge two-story martin apartment house, painted it white, and mounted it on a sturdy pole just inside our woods. I haunted the spot, waiting for birds to move in. But they never did. Not one single bird.

Year after year the martin house remained vacant. The paint flaked. The roof peeled. It was the saddest sight, that unlived-in house, built with anticipation and hope and the best of intentions. Later I realized purple martins are aerialists, catching gnats on the wing, and prefer their homes away from tall trees.

When we moved into this house, I hung a birdhouse from a hickory tree branch, never dreaming any self-respecting bird would move into a gaudy ornament from Lowe’s. Imagine my surprise last fall when I was raking leaves and glimpsed sticks poking out of the hole. Some bird family had actually nested in it!

Recently the Universe sent me something I didn’t know I needed until it was in front of me: a photo essay by Rob McDonald called “Birdhouses.” McDonald photographs spaces, like the homes of famous Southern writers and the more humble abodes of backyard birds. I was drawn to his images of miniature houses set at the edges of fields, made by hand, put up with the best of intentions.

Photo by Rob McDonald

When asked why he kept building birdhouses that were never used, one man told McDonald, “I guess I just like the idea of birds.”

I will never make the cottage children’s library happen. Yet now I can let the idea fly away knowing it’s okay to dream small dreams while tending the bigger ones.

It’s enough to face each day with anticipation, waiting for the flash of a bluebird as I take up my current project. I’m building a new place there, a new world to move into, in the hopes my readers will want to come, too.

March 3, 2014

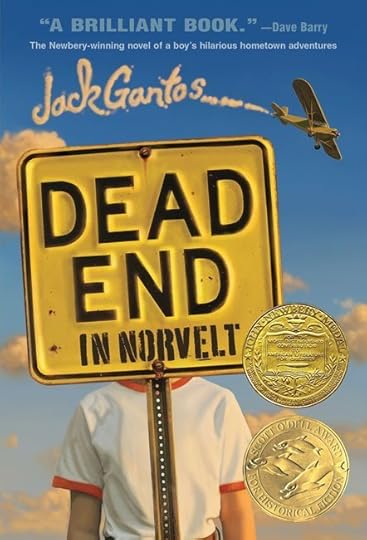

Why I’ll Never Be Jack Gantos

Kuretake Zig Letter Pen

I am waiting for a pen to come from Japan. Not a fancy pen. Not a rare, expensive pen. I’m waiting for a Kuretake Zig Letter Pen, body in Strawberry Pink. You buy the body of the pen separate from the refill. My friend Donna put me on this pen, which she read about in Uppercase magazine. I tried hers and agreed it was the best writing pen ever.

Ordering the $5.00 pen and its $5.00 refill (shipped on a slow boat from Japan) went along with discovering a new type of notebook in New York last weekend. I was attending the SCBWI Mid-winter conference. The conference coincided with a fabulous exhibit at the New York Public Library, “ABC of It: Why Children’s Books Matter.”

The exhibit made me glad I was a children’s book writer. Button-busting proud to be in the field. The original manuscripts and art reminded me why I loved books like Harriet the Spy (celebrating its 50th anniversary—I read it new) and The Cricket in Times Square.

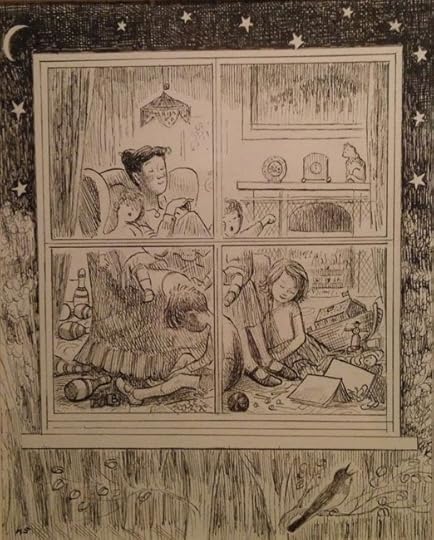

I stopped, entranced, by a Mary Shepard illustration for Mary Poppins A to Z. I leaned forward, pressing myself into the glass case, trying to enter that cozy scene. I used to do that with all the black and white drawings in my beloved middle grade novels as a way to extend my reading experience. I didn’t just read books back then, I lived them.

On my way out, I browsed the gift shop, almost the best part. I picked up Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost, a delightful map-making kit called Make Map Art: Creatively Illustrate Your World, and an odd little notebook by Apica, captioned a little weirdly as, “Most advanced quality gives best writing features.”

Back in my hotel room, I started writing in that little red unassuming notebook and nearly swooned. My extra fine Pilot pen swanned across the smooth paper. No ghosting, no bleed-through. The paper made me slow down and write neatly, which in turn made me slow down my thinking.

Apica CD15 notebook

The combination of the Kuretake pen and the Apica notebook sent me in a tizzy. I would be a much better writer with these tools! I’ll pitch my composition notebooks with chintzy paper that always bleeds through. I’ll order new colors of ink refills and different nibs for my new pen! Get the big Apica notebook with 96 pages instead of 28!

But none of this will make me like Jack Gantos.

Jack Gantos was the first keynote speaker at the conference. Nearly 1200 people were in the audience, eager, expectant. Jack is great speaker, funny, irreverent, smart, self-deprecating. I’d already chatted with the attendees in front of and next to me—they were new to the field. I envied them their fresh start on their journey.

I opened my notebook (composition with bleed-through paper, sigh) and took notes. Jack Gantos offered a great deal of his process in his slide presentation, along with excellent take-away tips. Everyone around me roared with laughter (I laughed, too), but they didn’t take notes.

What did I learn from Jack Gantos? Lots of things, but what struck me most was his work day. He gets up and packs his lunch. He stows his lunch and supplies in an L.L. Bean boat tote (complete with monogram) and off he goes to the library. Not just any library, the Athenaeum in Boston. He climbs what looked like five flights of spiral stairs to “his” table.

He unpacks his bag: a laptop that looked similar to my 2005 laptop, an older clamshell cell phone, a big plastic file with his notes, another plastic file with his project in progress. That’s it. On a good day, he works eight hours.

So why can’t I be like Jack Gantos? I even have a monogrammed boat tote to carry my lunch and supplies in. But I don’t know of a library near me that doesn’t have patrons tracking back and forth like turkeys and people yakking on phones.

However, I do have a nice office in my house so I don’t really need to go anywhere. More than location, it was Jack Gantos’s example of setting daily goals and ignoring distractions that hit home. He uses old-fashioned methods—writing drafts in longhand, for instance—and equipment that is hardly state of the art. He gets the work done without the frills.

That evening, I copied my scrawled notes from my composition notebook into my new Apica notebook. I wrote neatly and felt virtuous. I can’t wait for my new Kuretake pen to show up in my mailbox—my words will glide onto the silky paper. But will a new pen and notebook make any difference in my work? Will they make me write like Jack Gantos?

“Most advanced quality may give best writing features,” but stories come from the heart, not a special pen nib. New York was good for me. I met interesting people, heard wonderful speakers, saw gorgeous art. Best of all, what I heard and saw gave me back my ten-year-old self, the person I have to please first in my work.

Back home, I started putting into place some of the tips Jack Gantos generously gave us. I’ll never be Jack Gantos, but maybe I’ll be a better version of Candice Ransom.

February 16, 2014

Staying True to Your Story

1917 Corona 3 “personal” typewriter.

In the idea stage of a book, you and the idea are One. You never stop thinking about the idea. You send it glittery pink Valentines and promise to be faithful forever. All you ask in return is that the idea will never leave you and grow into something wonderful.

Having an idea for a book makes you feel good, complete. Even a little smug. No one has an idea like yours. Heather Sellers writes in Chapter after Chapter: Book ideas are reassuring and interesting, like imaginary friends.

Sellers also warns writers not to save ideas, lock them in a vault, a concept I understand, but also find a little troublesome. Sometimes you can’t get to an idea right away. You jot it down, make notes, and maybe that’s the best you can do. Is it possible to keep an idea alive until you’re ready to begin work on it? Is there a time limit when the idea goes stale or, as Sellers believes, turns to ashes?

[image error]

Carriage folds over keyboard to fit in case.

In the past two years, I’ve had a lot of book ideas, or ideas I thought were book-worthy. Some came too quickly, the result of wanting a new idea and hastily cobbling together a few elements, some I dreamed. And some were good, but I couldn’t hang on to them—they kept springing out of reach like greased crickets.

But I kept returning to one particular idea. I have saved this idea nearly five years. It’s not an ephemeral thing, this idea. It has substance and comes complete with reference books, notes, files, partial chapters, photographs, icons, even a fossil whale vertebrae.

I pull it out about twice a year, let stretch out across my desk for a while, then put it back because something else has come up (lately, non-writing related), or the idea seems to have too much stuff and feels like an elderly aunt come to stay with seventeen suitcases and her adenoidal Pekinese.

In my effort to settle down with a project that will make me race to the computer every morning, I find myself reading about children’s books. If I can’t go in through the front door, maybe I’ll find a window in the back somebody left open a crack.

On sunny Valentine’s afternoon, I lay across the bed with Welcome to Lizard Motel: Children, Stories, and the Mystery of Making Things Up by Barbara Feinberg. This book came out ten years ago to very mixed reviews. Feinberg takes on “problem novels” in children’s literature in the guise of a memoir. I remember standing in the education section of Borders and gaping at this book. I bought it and read it in one sitting. I didn’t care what people said, I loved it.

With Yellow Quilt draped over my legs and Winchester lodged against my feet, I re-read Lizard Motel in one sitting (or lying-down). At times the book dropped on my chest as I dozed or floated in reverie, the sun orange behind my eyelids. Is there any pleasure greater than re-reading a favorite book on a bright winter afternoon? It seemed so decadent—the dozing, the daydreaming, the warm sun, ignoring the urgent To Be Read stack. Yet it felt exactly right. As Wendell Berry says, When going back makes sense, you are going ahead.

I lingered over a passage where Feinberg is lying on the floor in the public library: I wanted to be a writer when I was fifteen, and as I look out through the slats [of the window] to the open, gray sky, I remember the feeling of wanting to write but having no idea what to say. What I wanted to express was inexpressible. It involved the universe.

I too wanted to be a writer when I was fifteen and knew I wanted to write for children. The universe was mine to grab. I’d claim it by setting down words.

Then I realized that while I have remained loyal to my teenage dream, I have not been loyal to my ideas. Loyalty is a two-way street. If I throw over an idea because I believe another, prettier one will saunter along, why should the old ones stick around? What about that four-year-old idea? Each time I brought it out, I expected it to start its own ignition and clack down the track without an engineer.

I didn’t do that when I was fifteen. I just wrote. Feinberg recalls when she was seven and learning to write was “just me, just the paper, the pencil, the mystery of words, all of which seemed to have secret compartments.”

The sun had gone down. The room was chilly. I sat up and cast off Yellow Quilt. I went into my office and dug out the files and reference books and photographs and notes associated with that old idea. I placed the fossil whale vertebrae in the green utility tray my grandfather had made.

The idea has not turned to ashes. It’s alive, still. I must invite it back, not use it as a default until something more dazzling rolls along. If I give it a fair chance, I’ll find the key to unlock those secret compartments. And with any luck, inside I’ll find the universe.